Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 1:38 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

- Privacy Policy

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

An Overview of Qualitative Research Methods

Direct Observation, Interviews, Participation, Immersion, Focus Groups

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Qualitative research is a type of social science research that collects and works with non-numerical data and that seeks to interpret meaning from these data that help understand social life through the study of targeted populations or places.

People often frame it in opposition to quantitative research , which uses numerical data to identify large-scale trends and employs statistical operations to determine causal and correlative relationships between variables.

Within sociology, qualitative research is typically focused on the micro-level of social interaction that composes everyday life, whereas quantitative research typically focuses on macro-level trends and phenomena.

Key Takeaways

Methods of qualitative research include:

- observation and immersion

- open-ended surveys

- focus groups

- content analysis of visual and textual materials

- oral history

Qualitative research has a long history in sociology and has been used within it for as long as the field has existed.

This type of research has long appealed to social scientists because it allows the researchers to investigate the meanings people attribute to their behavior, actions, and interactions with others.

While quantitative research is useful for identifying relationships between variables, like, for example, the connection between poverty and racial hate, it is qualitative research that can illuminate why this connection exists by going directly to the source—the people themselves.

Qualitative research is designed to reveal the meaning that informs the action or outcomes that are typically measured by quantitative research. So qualitative researchers investigate meanings, interpretations, symbols, and the processes and relations of social life.

What this type of research produces is descriptive data that the researcher must then interpret using rigorous and systematic methods of transcribing, coding, and analysis of trends and themes.

Because its focus is everyday life and people's experiences, qualitative research lends itself well to creating new theories using the inductive method , which can then be tested with further research.

Qualitative researchers use their own eyes, ears, and intelligence to collect in-depth perceptions and descriptions of targeted populations, places, and events.

Their findings are collected through a variety of methods, and often a researcher will use at least two or several of the following while conducting a qualitative study:

- Direct observation : With direct observation, a researcher studies people as they go about their daily lives without participating or interfering. This type of research is often unknown to those under study, and as such, must be conducted in public settings where people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy. For example, a researcher might observe the ways in which strangers interact in public as they gather to watch a street performer.

- Open-ended surveys : While many surveys are designed to generate quantitative data, many are also designed with open-ended questions that allow for the generation and analysis of qualitative data. For example, a survey might be used to investigate not just which political candidates voters chose, but why they chose them, in their own words.

- Focus group : In a focus group, a researcher engages a small group of participants in a conversation designed to generate data relevant to the research question. Focus groups can contain anywhere from 5 to 15 participants. Social scientists often use them in studies that examine an event or trend that occurs within a specific community. They are common in market research, too.

- In-depth interviews : Researchers conduct in-depth interviews by speaking with participants in a one-on-one setting. Sometimes a researcher approaches the interview with a predetermined list of questions or topics for discussion but allows the conversation to evolve based on how the participant responds. Other times, the researcher has identified certain topics of interest but does not have a formal guide for the conversation, but allows the participant to guide it.

- Oral history : The oral history method is used to create a historical account of an event, group, or community, and typically involves a series of in-depth interviews conducted with one or multiple participants over an extended period.

- Participant observation : This method is similar to observation, however with this one, the researcher also participates in the action or events to not only observe others but to gain the first-hand experience in the setting.

- Ethnographic observation : Ethnographic observation is the most intensive and in-depth observational method. Originating in anthropology, with this method, a researcher fully immerses themselves into the research setting and lives among the participants as one of them for anywhere from months to years. By doing this, the researcher attempts to experience day-to-day existence from the viewpoints of those studied to develop in-depth and long-term accounts of the community, events, or trends under observation.

- Content analysis : This method is used by sociologists to analyze social life by interpreting words and images from documents, film, art, music, and other cultural products and media. The researchers look at how the words and images are used, and the context in which they are used to draw inferences about the underlying culture. Content analysis of digital material, especially that generated by social media users, has become a popular technique within the social sciences.

While much of the data generated by qualitative research is coded and analyzed using just the researcher's eyes and brain, the use of computer software to do these processes is increasingly popular within the social sciences.

Such software analysis works well when the data is too large for humans to handle, though the lack of a human interpreter is a common criticism of the use of computer software.

Pros and Cons

Qualitative research has both benefits and drawbacks.

On the plus side, it creates an in-depth understanding of the attitudes, behaviors, interactions, events, and social processes that comprise everyday life. In doing so, it helps social scientists understand how everyday life is influenced by society-wide things like social structure , social order , and all kinds of social forces.

This set of methods also has the benefit of being flexible and easily adaptable to changes in the research environment and can be conducted with minimal cost in many cases.

Among the downsides of qualitative research is that its scope is fairly limited so its findings are not always widely able to be generalized.

Researchers also have to use caution with these methods to ensure that they do not influence the data in ways that significantly change it and that they do not bring undue personal bias to their interpretation of the findings.

Fortunately, qualitative researchers receive rigorous training designed to eliminate or reduce these types of research bias.

- How to Conduct a Sociology Research Interview

- Definition of Idiographic and Nomothetic

- What Is Participant Observation Research?

- Pilot Study in Research

- Conducting Case Study Research in Sociology

- How to Understand Interpretive Sociology

- What Is Ethnography?

- Understanding Secondary Data and How to Use It in Research

- Social Surveys: Questionnaires, Interviews, and Telephone Polls

- Research in Essays and Reports

- What Is Naturalistic Observation? Definition and Examples

- Definition and Overview of Grounded Theory

- A Review of Software Tools for Quantitative Data Analysis

- Content Analysis: Method to Analyze Social Life Through Words, Images

- The Sociology of the Internet and Digital Sociology

- Immersion Definition: Cultural, Language, and Virtual

Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is Research? – Purpose of Research

- By DiscoverPhDs

- September 10, 2020

The purpose of research is to enhance society by advancing knowledge through the development of scientific theories, concepts and ideas. A research purpose is met through forming hypotheses, collecting data, analysing results, forming conclusions, implementing findings into real-life applications and forming new research questions.

What is Research

Simply put, research is the process of discovering new knowledge. This knowledge can be either the development of new concepts or the advancement of existing knowledge and theories, leading to a new understanding that was not previously known.

As a more formal definition of research, the following has been extracted from the Code of Federal Regulations :

While research can be carried out by anyone and in any field, most research is usually done to broaden knowledge in the physical, biological, and social worlds. This can range from learning why certain materials behave the way they do, to asking why certain people are more resilient than others when faced with the same challenges.

The use of ‘systematic investigation’ in the formal definition represents how research is normally conducted – a hypothesis is formed, appropriate research methods are designed, data is collected and analysed, and research results are summarised into one or more ‘research conclusions’. These research conclusions are then shared with the rest of the scientific community to add to the existing knowledge and serve as evidence to form additional questions that can be investigated. It is this cyclical process that enables scientific research to make continuous progress over the years; the true purpose of research.

What is the Purpose of Research

From weather forecasts to the discovery of antibiotics, researchers are constantly trying to find new ways to understand the world and how things work – with the ultimate goal of improving our lives.

The purpose of research is therefore to find out what is known, what is not and what we can develop further. In this way, scientists can develop new theories, ideas and products that shape our society and our everyday lives.

Although research can take many forms, there are three main purposes of research:

- Exploratory: Exploratory research is the first research to be conducted around a problem that has not yet been clearly defined. Exploration research therefore aims to gain a better understanding of the exact nature of the problem and not to provide a conclusive answer to the problem itself. This enables us to conduct more in-depth research later on.

- Descriptive: Descriptive research expands knowledge of a research problem or phenomenon by describing it according to its characteristics and population. Descriptive research focuses on the ‘how’ and ‘what’, but not on the ‘why’.

- Explanatory: Explanatory research, also referred to as casual research, is conducted to determine how variables interact, i.e. to identify cause-and-effect relationships. Explanatory research deals with the ‘why’ of research questions and is therefore often based on experiments.

Characteristics of Research

There are 8 core characteristics that all research projects should have. These are:

- Empirical – based on proven scientific methods derived from real-life observations and experiments.

- Logical – follows sequential procedures based on valid principles.

- Cyclic – research begins with a question and ends with a question, i.e. research should lead to a new line of questioning.

- Controlled – vigorous measures put into place to keep all variables constant, except those under investigation.

- Hypothesis-based – the research design generates data that sufficiently meets the research objectives and can prove or disprove the hypothesis. It makes the research study repeatable and gives credibility to the results.

- Analytical – data is generated, recorded and analysed using proven techniques to ensure high accuracy and repeatability while minimising potential errors and anomalies.

- Objective – sound judgement is used by the researcher to ensure that the research findings are valid.

- Statistical treatment – statistical treatment is used to transform the available data into something more meaningful from which knowledge can be gained.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Types of Research

Research can be divided into two main types: basic research (also known as pure research) and applied research.

Basic Research

Basic research, also known as pure research, is an original investigation into the reasons behind a process, phenomenon or particular event. It focuses on generating knowledge around existing basic principles.

Basic research is generally considered ‘non-commercial research’ because it does not focus on solving practical problems, and has no immediate benefit or ways it can be applied.

While basic research may not have direct applications, it usually provides new insights that can later be used in applied research.

Applied Research

Applied research investigates well-known theories and principles in order to enhance knowledge around a practical aim. Because of this, applied research focuses on solving real-life problems by deriving knowledge which has an immediate application.

Methods of Research

Research methods for data collection fall into one of two categories: inductive methods or deductive methods.

Inductive research methods focus on the analysis of an observation and are usually associated with qualitative research. Deductive research methods focus on the verification of an observation and are typically associated with quantitative research.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a method that enables non-numerical data collection through open-ended methods such as interviews, case studies and focus groups .

It enables researchers to collect data on personal experiences, feelings or behaviours, as well as the reasons behind them. Because of this, qualitative research is often used in fields such as social science, psychology and philosophy and other areas where it is useful to know the connection between what has occurred and why it has occurred.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is a method that collects and analyses numerical data through statistical analysis.

It allows us to quantify variables, uncover relationships, and make generalisations across a larger population. As a result, quantitative research is often used in the natural and physical sciences such as engineering, biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, finance, and medical research, etc.

What does Research Involve?

Research often follows a systematic approach known as a Scientific Method, which is carried out using an hourglass model.

A research project first starts with a problem statement, or rather, the research purpose for engaging in the study. This can take the form of the ‘ scope of the study ’ or ‘ aims and objectives ’ of your research topic.

Subsequently, a literature review is carried out and a hypothesis is formed. The researcher then creates a research methodology and collects the data.

The data is then analysed using various statistical methods and the null hypothesis is either accepted or rejected.

In both cases, the study and its conclusion are officially written up as a report or research paper, and the researcher may also recommend lines of further questioning. The report or research paper is then shared with the wider research community, and the cycle begins all over again.

Although these steps outline the overall research process, keep in mind that research projects are highly dynamic and are therefore considered an iterative process with continued refinements and not a series of fixed stages.

In this post you’ll learn what the significance of the study means, why it’s important, where and how to write one in your paper or thesis with an example.

Find out how you can use Scrivener for PhD Thesis & Dissertation writing to streamline your workflow and make academic writing fun again!

Learn 10 ways to impress a PhD supervisor for increasing your chances of securing a project, developing a great working relationship and more.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

The term monotonic relationship is a statistical definition that is used to describe the link between two variables.

You’ve impressed the supervisor with your PhD application, now it’s time to ace your interview with these powerful body language tips.

Eleni is nearing the end of her PhD at the University of Sheffield on understanding Peroxidase immobilisation on Bioinspired Silicas and application of the biocatalyst for dye removal.

Henry is in the first year of his PhD in the Cronin Group at the University of Glasgow. His research is based on the automation, optimisation, discovery and design of ontologies for robotic chemistry.

Join Thousands of Students

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Back to results

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Use of qualitative methods in evaluation studies.

- Namita Ranganathan Namita Ranganathan University of Delhi

- and Toolika Wadhwa Toolika Wadhwa Shyama Prasad Mukherji College for Women

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.378

- Published online: 26 April 2019

Evaluation studies typically comprise research endeavors that are undertaken to investigate and gauge the effectiveness of a program, an institution, or individuals working in educational contexts, such as teachers, students, administrators, and other stakeholders in education. Usually, research studies in this genre use empirical methods to evaluate educational practices and systems. Alternatively, they may take up theoretical reflections on new policies, programs, and systems. An evaluation study requires a rigorous design and method of assessment to focus on the specific context and set of issues that it targets. In general, research studies that attempt to evaluate a program, an individual, or an institution place emphasis on checking their efficacy. They do not seek to find explanations that have led to the level of efficacy that the variables under study may have achieved. Thus, quite often, they are contested as not being full-fledged research.

Evaluation studies use a variety of methods. The choice of method depends on the area of study as well as the research questions. An evaluation study may thus fall within the qualitative or quantitative paradigms. Often, a mixed method approach is used. The purpose of the study plays a significant role in deciding the method of inquiry and analysis. Establishing the probability, plausibility, and adequacy of the program can be some of the main aims of evaluation studies. This implies as well that the programs, institutions, or individuals under study would have an impact on the course and direction of future programs and practices. An evaluation study is thus of vital importance to ensure that appropriate decisions can be made about efficacy, transferability to different contexts, and difficulties and challenges to be faced in subsequent applications.

Evaluation studies in India have been done in a vast range of areas that include program evaluation, impact studies, evaluations of specific interventions, performance outcome assessments, and the like. Some examples of studies undertaken by the government and the development sector in this regard are the following: assessment of interventions for adolescence education; impact studies of interventions, programs, and policies launched for education of minorities, including girls; and evaluation of performance outcomes stemming from programs for education of the marginalized.

The key challenges in evaluation studies are to gather accurate data in order to establish reliable outcomes, to establish clear relationships between the outcomes and the interventions being studied, and to safeguard against researcher bias.

- evaluation studies

- program evaluation

- qualitative evaluation

- outcome-based evaluation

- project evaluation

- inferring qualitative trends

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 22 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

Character limit 500 /500

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

Tanzanian adolescents’ attitudes toward abortion: innovating video vignettes in survey research on health topics

- Anna Bolgrien ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1954-2403 1 &

- Deborah Levison ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3718-3432 2

Reproductive Health volume 21 , Article number: 66 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The purpose of this study was to pilot an innovative cartoon video vignette survey methodology to learn about young people’s perspectives on abortion and sexual relationships in Tanzania. The Animating Children’s Views methodology used videos shown on tablets to engage young people in conversations. Such conversations are complicated because abortion is highly stigmatized, inaccessible, and illegal in Tanzania.

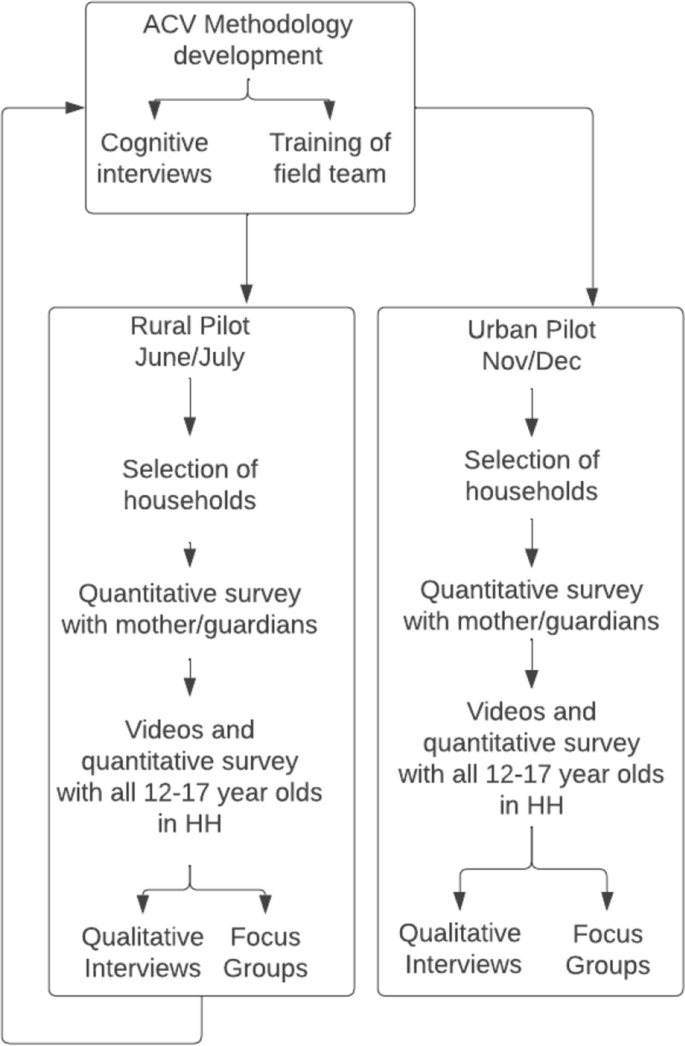

The cartoon video vignette methodology was conducted as a part of a quantitative survey using tablet computers. Hypothetical situations and euphemistic expressions were tested in order to engage adolescents on sensitive topics in low-risk ways. Qualitative interviews and focus groups validated and further explored the perspectives of the young respondents.

Results indicate that 12–17 year-olds usually understand euphemistic expressions for abortion and are aware of social stigma and contradictory norms surrounding abortion from as young as age twelve. Despite the risks involved with abortion, this study finds adolescents sometimes view abortion as a reasonable solution to allow a girl to remain in school. Additional findings show that as adolescents wrestle with how to respond to a schoolgirl’s pregnancy, they are considering both the (un)affordability of healthcare services and also expectations for gender roles.

Conclusions

Digital data collection, such as the Animating Children’s Views cartoon video vignettes used in this study, allows researchers to better understand girls’ and boys’ own perspectives on their experiences and reproductive health.

Plain English Summary

The Animating Children’s Views project used cartoon video vignettes to collect quantitative and qualitative data on girls’ and boys’ (infrequently included) perspectives about this sensitive topic as these young people aged into and figured out how to navigate sexual maturity in rural and urban Tanzania. This novel survey technique leveraged digital technology to better engage young people’s perspectives about sensitive health topics. Despite the risks involved with abortion, this study finds adolescents sometimes view abortion as a reasonable solution to allow a girl to remain in school. Additional findings show that as adolescents wrestle with how to respond to a schoolgirl’s pregnancy, they are considering both the (un)affordability of healthcare services and also expectations for gender roles. We argue that digital data collection allows survey research to include girls and boys, to better understand how reproductive health outcomes are inextricably linked to their future lives.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

“Sometimes bad luck happens, and a girl gets pregnant when she is still studying. And if the teacher knows about it, she might not attend school. And she can either abort the pregnancy or deliver and care for the baby. Some of the students are curious. They might know she is pregnant. It will be a shame on her. They can report her to the teacher, and she might be dismissed from school. The teachers will not understand her situation; they will not know it’s something that you did not plan for. They will feel you did it deliberately.” [girl, age 15, focus group, urban]

Approximately one-quarter of Tanzanian adolescents girls become pregnant between the ages of 15 to 19 years [ 43 ]. Many young people in Tanzania are sexually active from as young as 10–14 years of age or plan to become sexually active before marriage [ 27 , 15 ]. Some girls have sex because boys are not expected to be abstinent, and they expect their girlfriends to have sex with them. In addition to seeking sexual relationships out of desire, girls may enter into consensual transactional sexual relationships with older boys or men as a way to secure financial stability [ 25 , 46 ]. Peer pressure, lack of familial financial support, lack of information about health services, and poverty all strongly correlate with high rates of teenage pregnancy [ 29 ]. Cultural barriers make it difficult for schools, non-governmental organizations, and parents to communicate appropriate and accurate reproductive health information to youth [ 34 , 45 ]. Girls may face difficulties obtaining and paying for contraceptives [ 23 ] or for an abortion after an unplanned pregnancy.

Girls experience stigma at multiple levels of society when navigating teenage sexual relationships and their education [ 18 , 33 ]. To surmount these and other challenges, Tanzanian girls and boys are convinced that “education is the key to life” ( Elimu ni ufunguo wa maisha. See Vavrus [ 44 ]). Becoming pregnant while in school puts a girl at risk of social isolation and being labeled a “bad girl” [ 11 ]. Additionally, at the time of this study the legal reality was that pregnant girls were expelled from school [ 8 ]. In 2021, the World Bank’s influence and change in Tanzanian leadership have led to changes in the government’s approach to schoolgirl pregnancy and motherhood (Reuters [ 35 ]). However, implementation of the revised policy requires separate schools for young mothers, which are unlikely to be accessible for much of the population any time soon.

What results is a culture of secrecy where young people hide their relationships from parents and peers alike. Abortion – illegal in Tanzania – may seem like a way of escaping a life-long penalty for premarital sexual activity. Yet, unsafe abortions account for a substantial fraction of maternal deaths in Tanzania [ 17 ]. Anti-abortion sentiment arises from religious objections; pro-choice discourse from public health aims to reduce maternal mortality rates due to unsafe illegal abortions; and human rights organizations call for women to have a choice in their reproductive health [ 36 ]. In the event of a pregnancy, secrecy can be maintained only through unsafe and potentially deadly abortion services, as the great majority of girls cannot raise the necessary funds for safer illegal abortions in private clinics [ 39 ].

Given the consequences of the lack of social support, accurate health information, and significant impacts to their lives, it is important to learn more about how young people are navigating the competing pressures of engaging in sexual relationships and staying in school if policy makers and researchers are to help improve outcomes for adolescents. While the overall study was methodologically driven and featured various topics and themes relating to the lives of adolescents in Tanzania, this paper focuses on how a cartoon video vignette methodology engaged young people in order to learn about how they weighed the risks and benefits of abortion in a context where teen pregnancy may be the end of education for girls.

In this paper, we present mixed-methods results using quantitative and qualitative data collected in response to a story about teen pregnancy. We find children and adolescents understood concerns about social stigma and were aware of contradictory norms surrounding abortion. They also shared their perceptions of inadequate health care services and views on gendered decision-making. Our results show that adolescents were considering complex social, medical, ethical, and pragmatic factors surrounding teenage pregnancy and abortion. In addition to the substantive findings, this paper also argues that a vignette methodology can be a useful way to collect survey data on children’s perspectives, made possible through advances in the usability and affordability of digital technology in field work. We describe two techniques – the use of euphemistic expressions and asking questions about hypotheticals – to learn children’s opinions about sensitive topics like abortion.

Methodology: using video vignettes in survey research

The relationship between high rates of teenage pregnancy and unknown rates of abortion – both sensitive topics – is examined primarily in qualitative research because researchers can take more time to establish rapport and build trust, thereby reducing risks to and vulnerability felt by participants [ 9 ]. Qualitative research is ideal for understanding nuances of how youth are interpreting cultural norms towards abortion and how they are thinking about access, effectiveness, and safety of abortion services in the event that they may at some point face an unplanned pregnancy. However, qualitative studies of youth’s experience and attitudes towards abortion across sub-Saharan Africa typically engage with older girls, most often between 15 and 24 years old, such as Bajoga et al. [ 3 ] and Otoide et al. [ 31 ] in Nigeria, Silburschmidt and Rasch [ 39 ] in Tanzania, Hall et al. [ 11 ] in Ghana, and Marlow et al. [ 22 ] in Kenya. Data on boys of all ages and younger girls are limited; one exception is Sommer et al. [ 40 ].

It can be difficult to gather quantitative data on experiences of abortion. Survey research on abortion in Tanzania and elsewhere generally focuses on adult women and occasionally men. While married or older women may feel less stigma associated with sexual behaviors, survey respondents may still feel uncomfortable responding to abortion-related topics that may be inappropriate to discuss in public, topics that would lead to admitting an illegal action, or topics where a truthful answer would be a violation of a social norm [ 42 ]. In the case of abortion, qualitative interviews with adult women in Tanzania and elsewhere who have experienced abortion frequently report that internalized stigma results in abortions being underreported or omitted from survey data (e.g., Astbury-Ward et al. [ 1 ] for the UK; Haws et al. [ 13 ] for Tanzania). Quantitative surveys typically avoid sensitive topics, particularly in contexts where privacy may be impossible. This is of high importance when engaging with vulnerable people. Adolescents may be particularly alert to sensitive topics and not feel comfortable disclosing their experiences in direct conversation [ 4 ]. If the children or adolescents are overheard saying anything that an adult deems inappropriate, they could be physically punished, have food withheld or be otherwise penalized. Quantitative studies of adolescents in Tanzania include a few examples of young people’s sexual experiences but these do not specifically discuss abortion [ 32 , 28 , 38 ].

Vignettes are one way that survey researchers can learn respondents’ views, by asking them about characters in a story instead of about personal experiences [ 10 , 30 , 14 ]. Vignettes can be written text, cartoons, read-aloud, or videos; respondents answer questions based on details in the story. Videos shown on tablets are similar to methods of communication that many young people in Tanzania are familiar with: 100% of our respondents had seen a video before. Instead of solely using a traditional question-answer format – which may feel to adolescents like an examination – videos creatively allowed participants to engage with stories.

Vignettes about abortion have been used in previous studies with adults (Sastre et al. [ 37 ] in France, Hans and Kimberly [ 12 ] in USA, Kavanaugh et al. [ 16 ] in Nigeria and Zambia). In a study in neighboring Kenya, Mitchell et al. [ 24 ] used vignettes to compare adolescents’ recommendations to a fictional couple, their own hypothetical future, and real examples of peers’ unplanned pregnancies and abortions. Their results suggest that respondents held different expectations for the vignette couple than for themselves or their peers.

The research presented in this paper fills a gap in the literature: young people’s perspectives – especially those of younger girls and of boys – are often excluded from research on abortion and sexual relationships. We show results from a novel methodology designed to illuminate the perspectives of children in low-income countries while reducing participation risks for young respondents.

Methodology: Animating Children’s Views (ACV)

The Animating Children’s Views (ACV) methodology developed by Levison and Bolgrien [ 21 ] used cartoon vignettes to present short stories to 12-to-17-year-olds in rural and urban northern Tanzania. While the use of tablet computers to collect survey data in the field is not a new technology, the ability to incorporate short videos during the survey allowed the field team to better engage young respondents during the interview. Respondents watched the cartoons and then responded to survey questions posed by interviewers about the situation and possible outcomes for characters in the stories. The innovation in using tablets to show videos establishes a way to create an experience where the respondent is expressing perspectives or opinions on a qualitative topic, but responses are coded as quantitative data collected during a survey.

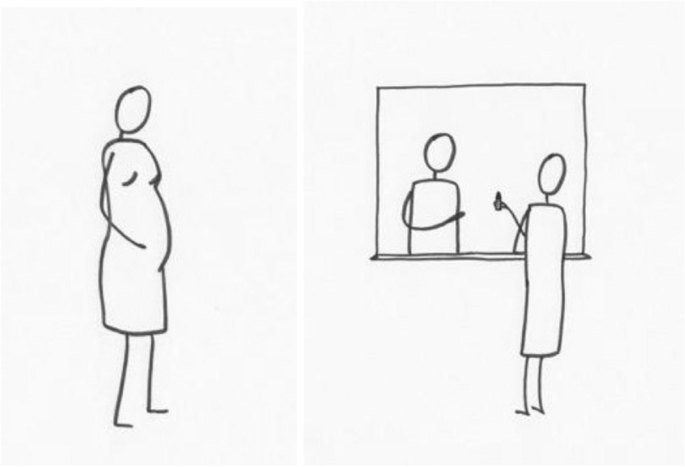

In pilots of the ACV methodology, we developed several vignettes representing situations that are commonly understood by Tanzanian adolescents. As discussed above, the primary method of reducing risk was to present stories to young respondents on tablet computers, using audio heard privately through headphones. The stories were followed by questions about the stories conducted using a typical interviewer-led survey, but with reference to the videos that would be unlikely for nearby adults to understand (since they didn’t hear the videos). This, in turn, reduced the risk of participants being punished for responses viewed as inappropriate. Using free software and simple drawings, we created short cartoon videos with young protagonists along with recorded voice-overs in Swahili. The cartoon characters lack physical or contextual characteristics that would associate them with any particular ethnicity or socio-economic status. Figure 1 shows two of the images from the story about teen pregnancy.

Images of pregnant girl and “getting herbs or medicine” from ACV teen pregnancy vignette. Artist credit: Hillary Carter-Liggett

As described above, respondents watched a video and then answered survey questions about the dilemma it described. Some response options used a 5-point “Smiley Scale”: respondents could point at a face emoji (very sad/angry to very happy). Other questions required responses of a word or phrase. To better understand the quantitative results, some young respondents participated in brief qualitative interviews after the conclusion of the quantitative survey data collection, and some joined sex- and age-specific focus groups. All stories were validated in collaboration with the Tanzanian field team and through cognitive interviews with Tanzanian adolescents.

In the vignette analyzed in this paper, a schoolgirl with a boyfriend finds herself pregnant. The story explains that the girl would like children at some point, but now is not the right time. The girl recognizes that it is difficult for pregnant girls and mothers to remain in school. The cartoon girl thinks about several possible outcomes for the pregnancy, including getting an abortion, marrying the boy, or asking grandparents to care for the baby. Girls heard a female voice telling the story from the point of view of the cartoon girl. Boys were shown exactly the same video images but heard a male voice narrating from the point of view of the father of the fetus. No information about the cartoon couples’ exact ages, education levels, or family backgrounds was given, though our pretesting of the story suggests most respondents interpreted the characters as young people of similar ages to themselves.

Interviewer effects on survey data are a persistent concern for researchers especially when interviewing children and adolescents [ 19 ]. In an attempt to please interviewers, respondents may answer questions in ways that are consistent with a dominant social narrative; Morris [ 26 ] calls such responses “scripts” based on her research with adolescents in Zanzibar, Tanzania. For example, Mitchell et al. [ 24 ] found that children in Kenya often referenced textbook sentiments about abortions. In our study, survey questions following the vignette asked what the cartoon characters should do. The question wording allowed the respondent to keep the conversation firmly in the hypothetical third person (about the cartoon character) instead of asking respondents to share information about their personal opinions or experiences. Although Mitchell et al. [ 24 ] found that their respondents were more understanding of peers and of themselves than of vignette characters, in our focus groups young people often used local examples or even slipped into the first person when describing what the cartoon character should do in a difficult situation. This is a local example:

“I was studying with this girl. She got pregnant. The father of this girl came to school, and the teachers said, ‘we can’t accept this girl back because she is pregnant.’ The girl dropped out of school. But as her friends, we were not happy about the situation.” [boy, 17, focus group, rural].

Even though we explicitly did not request information about young people’s own experiences, these came up naturally in qualitative discussions. Similar to Mitchell et al.’s [ 24 ] conclusions, we demonstrate below that Tanzanian youth express opinions that sometimes conform to but also sometimes contradict social narratives or scripts, even when discussing hypothetical vignettes.

Some of the quotes presented in this paper may make it seem as if a child were asked directly about abortion or were asked to describe personal experiences. This was not the case. During interactions between field researchers and young respondents, we aimed to minimize any discussion using the word “abortion” in order to protect the adolescent from repercussions from conversing with a stranger about a sensitive topic. As corporal punishment is common in Tanzania, ethical protection of children as a vulnerable population necessitated extra caution on behalf of the research team to mitigate the potential of a child being punished by an adult who overheard the interview [ 41 ]. Instead of speaking directly about abortions, the euphemism “take herbs and medicine to get her period back” was used in Swahili. The results section will show that most young respondents understood this euphemism. If a child voluntarily used the word “abortion” or mentioned other sensitive topics, field researchers were trained to continue the conversation only if the location of the interview was private enough that there was no risk of being overheard by adults or other children. We conducted a small follow-up study with respondents in the pilot and none reported any risk or discomfort following the interview ([ 21 ], pg S152). We attribute our success to these precautions.

Data Collection

The vignette methodology was piloted in two locations in northern Tanzania in 2018 using a mixed-methods approach as shown in Fig. 2 . This project was approved on May 18, 2018, by the IRB of the University of Minnesota (STUDY00003131) and by the Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH) on May 10, 2018, in Tanzania. Adult and child participants were given a small gift of sugar, school supplies or a small monetary payment based on recommendations by local collaborators. The first pilot location was a village in the Arusha District that was purposefully selected based on the diversity of ethnicities (predominantly Chagga and Iraqw), religions (Christian and Muslim) and occupations (farming, herding, and small businesses). Following the rural pilot, a second pilot was conducted in urban areas in Arusha District. We used a household-based instead of a school-based sample and did not require literacy to identify our study population. The pilots used a two-stage systematic random sampling of households in wards and neighborhoods drawn for the purpose of this study by the field team with support from local village and community leaders, as discussed in Bolgrien and Levison [ 6 ]. In each household, an adult answered a questionnaire about household demographics, and all available children ages 12–17 in the household were asked to participate in a face-to-face administered survey that included vignettes. Adults gave consent for household and child participation and children gave assent to the interviewer prior to the start of the survey. Survey teams were trained to conduct the survey in a public (visible) area but out of earshot of adults, to create privacy for the child respondents during in-person surveys and one-on-one interviews; training also included other methods to reduce perceived power disparities between adult interviewers and young interviewees [ 7 ]. Each pilot included teams of 4–6 experienced young Tanzanian interviewers; the authors and local staff conducted additional training in survey data collection and qualitative methods with adolescents.

Study development and pilot studies in Tanzania 2018

Table 1 shows sample characteristics for young survey respondents. In total, 327 children in 248 households were surveyed. Most came from relatively large households of about six people (including themselves). In each household, each available (and assenting) 12–17 year-old was included in the survey. In both samples, especially the rural village, the sample was skewed toward younger ages. Older children were often away in boarding school or had left home to work. The urban field research was conducted during the beginning of a school holiday so more older adolescents were available. Although all survey participants had attended school at some point, more than one-quarter of the rural children were no longer enrolled in school. The vignette about teen pregnancy was only one of several possible vignette topics the children watched. Children were asked between each video if they would like to continue participating. In the rural village, children were shown up to four videos in a random order. During the rural pilot, one-third of respondents did not watch all four vignette videos, but data on the reason for discontinuing – a child’s decision, a field team member determining the child was fatigued or distracted, or an adult interrupting the interview – was not collected. Based on feedback from the field team after the rural pilot, we modified the survey design for the urban pilot to present 3 videos in a set order to reduce respondent burden. In the urban pilot, only 4% of respondents did not complete the 3 videos. A subset of 291 out of the 327 surveyed adolescents watched the story about teen pregnancy and answered its follow-up questions.

To better interpret the results from the quantitative survey data collected from households and children, we also collected concurrent qualitative data from the child respondents. After participating in the survey, a subset of 152 children assented to participate in semi-structured interviews which took place directly following the child’s survey. Children were asked about their answers to some of the survey questions about one or more of the videos. Finally, children who participated in the survey were asked if they would like to participate in focus groups. Interested and available children were organized into focus group discussions of three to 10 participants, grouped by sex and similar ages, to have conversations about the vignettes. The aim of these short interviews and focus groups was to assess the understandability of the vignettes, the degree of personal connection the children felt in regard to each story, and to explore ideas children had about possible outcomes for the story. The focus group discussions and interviews were conducted, recorded, transcribed verbatim, translated from Swahili to English by the field team, and coded using ATLAS.ti 8 (Version 8.4.24.0) [ 2 ] in a collaborative and iterative effort by both authors and a project assistant. The story about teen pregnancy was discussed in 90 of the interviews and focus groups, and the topic of abortion was discussed 87 times. Language used in this paper will attempt to be true to the respondents’ language, e.g. referring to the cartoon boy as the “father” and saying “baby” instead of “fetus.”

Results and discussion about using a euphemism for abortion

As discussed above, we avoided using the term “abortion,” instead using the euphemism “the girl could take herbs or medicine to get her period back,” similar to other researchers’ use of euphemistic phrases like “sleep with someone” and “to make love” instead of “sexual intercourse” [ 33 , 5 ]. During the preparation and training for the field work, this phrase was generally understood by respondents. We continued to validate that this phrase was understood during the qualitative interviews that followed the survey.

Based on the follow-up interviews, older respondents of both sexes understood the language around “herbs and medicine” to be referring to abortion. When abortion was discussed, 26 respondents used language that indicated their understanding that the situation implied abortion or terminating the pregnancy. For example:

Interviewer: And then she uses herbs or medicines to get her periods back, what do you think is going to happen?

Respondent: abortion

Interviewer: what are the effects of it?

Respondent: The unborn baby will die. [boy, 14, urban]

In another 13 interviews, the young respondent’s language indicated clearly that she or he understood the purpose of using herbs and medicine but did not refer to abortion directly. Instead, language such as “bringing back normal periods,” “losing the baby,” “grief,” and “negative effects” are examples of how respondents referenced the termination of a pregnancy. A 14-year-old girl indicated in the survey that the cartoon girl was somewhat happy to take herbs and medicine, and during the interview the respondent described happiness resulting from using the herbs. The interviewer asked, “what are other effects after she gets her period back?” and the girl replied, “abortion.” After this, the respondent became less talkative and responsive and changed the subject.

Seven interviewees (both genders, age 12–15) likely did not understand the nuanced language of “herbs and medicine” to imply abortion. One (boy, 13, rural) misunderstood that herbs or medicine referred to birth control or pre-natal care given at hospitals. Additionally, some younger boys and girls did not make the connection between menstruation and pregnancy. Education (formal or informal) about reproduction and reproductive health is very limited for younger children in Tanzania [ 27 ]. Whereas girls may be warned about the possibility of pregnancy when they begin menstruating, this may not happen for boys entering puberty. Several of the older boys incorrectly described female reproductive anatomy and how or when to use birth control.

Results and discussion on young people’s perspectives on abortion

A survey question about the teen pregnancy vignette asked respondents to identify what was most likely to happen to the cartoon kids. As shown in Table 2 , among the options presented, 18% of respondents reported that the girl would abort the baby; it was the third highest-ranking option out of the five options, behind getting married and taking the baby to the girl’s family. In an open-ended question (not shown) that asked the respondent to imagine the most likely outcome to the story if it happened “around here,” 11% chose abortion.

The relative popularity of the options about getting married or having parents of the girl or boy help to care for the baby is consistent with the qualitative findings from the interviews and focus groups. Respondents often described the cartoon girl and boy as considering possible outcomes in order of desirability: If it was unlikely the cartoon couple could marry or care for the baby themselves, they would next approach one or both sets of parents; if that was unsuccessful or undesirable, then an abortion was considered. For example,

She will feel happy because it’s something she did not really like and did not expect it. So, if he [presumably the cartoon boyfriend] goes to his parent, first if he goes to the parents of the girl. I mean they can reject [the pregnancy or baby] and they can hate him. So she was, I mean … that’s why I said she would feel happy. Because, I mean, she probably can’t afford it and she might need to reduce her responsibilities. Because if she used those herbs to abort the pregnancy, you will find that she can continue with her normal things. [boy, 14, urban, 5 on Smiley Scale]