- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

CorporateStrategy →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

Related Expertise: Organizational Culture , Business Strategy , Change Management

Five Case Studies of Transformation Excellence

November 03, 2014 By Lars Fæste , Jim Hemerling , Perry Keenan , and Martin Reeves

In a business environment characterized by greater volatility and more frequent disruptions, companies face a clear imperative: they must transform or fall behind. Yet most transformation efforts are highly complex initiatives that take years to implement. As a result, most fall short of their intended targets—in value, timing, or both. Based on client experience, The Boston Consulting Group has developed an approach to transformation that flips the odds in a company’s favor. What does that look like in the real world? Here are five company examples that show successful transformations, across a range of industries and locations.

VF’s Growth Transformation Creates Strong Value for Investors

Value creation is a powerful lens for identifying the initiatives that will have the greatest impact on a company’s transformation agenda and for understanding the potential value of the overall program for shareholders.

VF offers a compelling example of a company using a sharp focus on value creation to chart its transformation course. In the early 2000s, VF was a good company with strong management but limited organic growth. Its “jeanswear” and intimate-apparel businesses, although responsible for 80 percent of the company’s revenues, were mature, low-gross-margin segments. And the company’s cost-cutting initiatives were delivering diminishing returns. VF’s top line was essentially flat, at about $5 billion in annual revenues, with an unclear path to future growth. VF’s value creation had been driven by cost discipline and manufacturing efficiency, yet, to the frustration of management, VF had a lower valuation multiple than most of its peers.

With BCG’s help, VF assessed its options and identified key levers to drive stronger and more-sustainable value creation. The result was a multiyear transformation comprising four components:

- A Strong Commitment to Value Creation as the Company’s Focus. Initially, VF cut back its growth guidance to signal to investors that it would not pursue growth opportunities at the expense of profitability. And as a sign of management’s commitment to balanced value creation, the company increased its dividend by 90 percent.

- Relentless Cost Management. VF built on its long-known operational excellence to develop an operating model focused on leveraging scale and synergies across its businesses through initiatives in sourcing, supply chain processes, and offshoring.

- A Major Transformation of the Portfolio. To help fund its journey, VF divested product lines worth about $1 billion in revenues, including its namesake intimate-apparel business. It used those resources to acquire nearly $2 billion worth of higher-growth, higher-margin brands, such as Vans, Nautica, and Reef. Overall, this shifted the balance of its portfolio from 70 percent low-growth heritage brands to 65 percent higher-growth lifestyle brands.

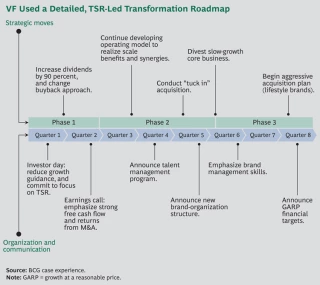

- The Creation of a High-Performance Culture. VF has created an ownership mind-set in its management ranks. More than 200 managers across all key businesses and regions received training in the underlying principles of value creation, and the performance of every brand and business is assessed in terms of its value contribution. In addition, VF strengthened its management bench through a dedicated talent-management program and selective high-profile hires. (For an illustration of VF’s transformation roadmap, see the exhibit.)

The results of VF’s TSR-led transformation are apparent. 1 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. Notes: 1 For a detailed description of the VF journey, see the 2013 Value Creators Report, Unlocking New Sources of Value Creation , BCG report, September 2013. The company’s revenues have grown from $7 billion in 2008 to more than $11 billion in 2013 (and revenues are projected to top $17 billion by 2017). At the same time, profitability has improved substantially, highlighted by a gross margin of 48 percent as of mid-2014. The company’s stock price quadrupled from $15 per share in 2005 to more than $65 per share in September 2014, while paying about 2 percent a year in dividends. As a result, the company has ranked in the top quintile of the S&P 500 in terms of TSR over the past ten years.

A Consumer-Packaged-Goods Company Uses Several Levers to Fund Its Transformation Journey

A leading consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) player was struggling to respond to challenging market dynamics, particularly in the value-based segments and at the price points where it was strongest. The near- and medium-term forecasts looked even worse, with likely contractions in sales volume and potentially even in revenues. A comprehensive transformation effort was needed.

To fund the journey, the company looked at several cost-reduction initiatives, including logistics. Previously, the company had worked with a large number of logistics providers, causing it to miss out on scale efficiencies.

To improve, it bundled all transportation spending, across the entire network (both inbound to production facilities and out-bound to its various distribution channels), and opened it to bidding through a request-for-proposal process. As a result, the company was able to save 10 percent on logistics in the first 12 months—a very fast gain for what is essentially a commodity service.

Similarly, the company addressed its marketing-agency spending. A benchmark analysis revealed that the company had been paying rates well above the market average and getting fewer hours per full-time equivalent each year than the market standard. By getting both rates and hours in line, the company managed to save more than 10 percent on its agency spending—and those savings were immediately reinvested to enable the launch of what became a highly successful brand.

Next, the company pivoted to growth mode in order to win in the medium term. The measure with the biggest impact was pricing. The company operates in a category that is highly segmented across product lines and highly localized. Products that sell well in one region often do poorly in a neighboring state. Accordingly, it sought to de-average its pricing approach across locations, brands, and pack sizes, driving a 2 percent increase in EBIT.

Similarly, it analyzed trade promotion effectiveness by gathering and compiling data on the roughly 150,000 promotions that the company had run across channels, locations, brands, and pack sizes. The result was a 2 terabyte database tracking the historical performance of all promotions.

Using that information, the company could make smarter decisions about which promotions should be scrapped, which should be tweaked, and which should merit a greater push. The result was another 2 percent increase in EBIT. Critically, this was a clear capability that the company built up internally, with the objective of continually strengthening its trade-promotion performance over time, and that has continued to pay annual dividends.

Finally, the company launched a significant initiative in targeted distribution. Before the transformation, the company’s distributors made decisions regarding product stocking in independent retail locations that were largely intuitive. To improve its distribution, the company leveraged big data to analyze historical sales performance for segments, brands, and individual SKUs within a roughly ten-mile radius of that retail location. On the basis of that analysis, the company was able to identify the five SKUs likely to sell best that were currently not in a particular store. The company put this tool on a mobile platform and is in the process of rolling it out to the distributor base. (Currently, approximately 60 percent of distributors, representing about 80 percent of sales volume, are rolling it out.) Without any changes to the product lineup, that measure has driven a 4 percent jump in gross sales.

Throughout the process, management had a strong change-management effort in place. For example, senior leaders communicated the goals of the transformation to employees through town hall meetings. Cognizant of how stressful transformations can be for employees—particularly during the early efforts to fund the journey, which often emphasize cost reductions—the company aggressively talked about how those savings were being reinvested into the business to drive growth (for example, investments into the most effective trade promotions and the brands that showed the greatest sales-growth potential).

In the aggregate, the transformation led to a much stronger EBIT performance, with increases of nearly $100 million in fiscal 2013 and far more anticipated in 2014 and 2015. The company’s premium products now make up a much bigger part of the portfolio. And the company is better positioned to compete in its market.

A Leading Bank Uses a Lean Approach to Transform Its Target Operating Model

A leading bank in Europe is in the process of a multiyear transformation of its operating model. Prior to this effort, a benchmarking analysis found that the bank was lagging behind its peers in several aspects. Branch employees handled fewer customers and sold fewer new products, and back-office processing times for new products were slow. Customer feedback was poor, and rework rates were high, especially at the interface between the front and back offices. Activities that could have been managed centrally were handled at local levels, increasing complexity and cost. Harmonization across borders—albeit a challenge given that the bank operates in many countries—was limited. However, the benchmark also highlighted many strengths that provided a basis for further improvement, such as common platforms and efficient product-administration processes.

To address the gaps, the company set the design principles for a target operating model for its operations and launched a lean program to get there. Using an end-to-end process approach, all the bank’s activities were broken down into roughly 250 processes, covering everything that a customer could potentially experience. Each process was then optimized from end to end using lean tools. This approach breaks down silos and increases collaboration and transparency across both functions and organization layers.

Employees from different functions took an active role in the process improvements, participating in employee workshops in which they analyzed processes from the perspective of the customer. For a mortgage, the process was broken down into discrete steps, from the moment the customer walks into a branch or goes to the company website, until the house has changed owners. In the front office, the system was improved to strengthen management, including clear performance targets, preparation of branch managers for coaching roles, and training in root-cause problem solving. This new way of working and approaching problems has directly boosted both productivity and morale.

The bank is making sizable gains in performance as the program rolls through the organization. For example, front-office processing time for a mortgage has decreased by 33 percent and the bank can get a final answer to customers 36 percent faster. The call centers had a significant increase in first-call resolution. Even more important, customer satisfaction scores are increasing, and rework rates have been halved. For each process the bank revamps, it achieves a consistent 15 to 25 percent increase in productivity.

And the bank isn’t done yet. It is focusing on permanently embedding a change mind-set into the organization so that continuous improvement becomes the norm. This change capability will be essential as the bank continues on its transformation journey.

A German Health Insurer Transforms Itself to Better Serve Customers

Barmer GEK, Germany’s largest public health insurer, has a successful history spanning 130 years and has been named one of the top 100 brands in Germany. When its new CEO, Dr. Christoph Straub, took office in 2011, he quickly realized the need for action despite the company’s relatively good financial health. The company was still dealing with the postmerger integration of Barmer and GEK in 2010 and needed to adapt to a fast-changing and increasingly competitive market. It was losing ground to competitors in both market share and key financial benchmarks. Barmer GEK was suffering from overhead structures that kept it from delivering market-leading customer service and being cost efficient, even as competitors were improving their service offerings in a market where prices are fixed. Facing this fundamental challenge, Barmer GEK decided to launch a major transformation effort.

The goal of the transformation was to fundamentally improve the customer experience, with customer satisfaction as a benchmark of success. At the same time, Barmer GEK needed to improve its cost position and make tough choices to align its operations to better meet customer needs. As part of the first step in the transformation, the company launched a delayering program that streamlined management layers, leading to significant savings and notable side benefits including enhanced accountability, better decision making, and an increased customer focus. Delayering laid the path to win in the medium term through fundamental changes to the company’s business and operating model in order to set up the company for long-term success.

The company launched ambitious efforts to change the way things were traditionally done:

- A Better Client-Service Model. Barmer GEK is reducing the number of its branches by 50 percent, while transitioning to larger and more attractive service centers throughout Germany. More than 90 percent of customers will still be able to reach a service center within 20 minutes. To reach rural areas, mobile branches that can visit homes were created.

- Improved Customer Access. Because Barmer GEK wanted to make it easier for customers to access the company, it invested significantly in online services and full-service call centers. This led to a direct reduction in the number of customers who need to visit branches while maintaining high levels of customer satisfaction.

- Organization Simplification. A pillar of Barmer GEK’s transformation is the centralization and specialization of claim processing. By moving from 80 regional hubs to 40 specialized processing centers, the company is now using specialized administrators—who are more effective and efficient than under the old staffing model—and increased sharing of best practices.

Although Barmer GEK has strategically reduced its workforce in some areas—through proven concepts such as specialization and centralization of core processes—it has invested heavily in areas that are aligned with delivering value to the customer, increasing the number of customer-facing employees across the board. These changes have made Barmer GEK competitive on cost, with expected annual savings exceeding €300 million, as the company continues on its journey to deliver exceptional value to customers. Beyond being described in the German press as a “bold move,” the transformation has laid the groundwork for the successful future of the company.

Nokia’s Leader-Driven Transformation Reinvents the Company (Again)

We all remember Nokia as the company that once dominated the mobile-phone industry but subsequently had to exit that business. What is easily forgotten is that Nokia has radically and successfully reinvented itself several times in its 150-year history. This makes Nokia a prime example of a “serial transformer.”

In 2014, Nokia embarked on perhaps the most radical transformation in its history. During that year, Nokia had to make a radical choice: continue massively investing in its mobile-device business (its largest) or reinvent itself. The device business had been moving toward a difficult stalemate, generating dissatisfactory results and requiring increasing amounts of capital, which Nokia no longer had. At the same time, the company was in a 50-50 joint venture with Siemens—called Nokia Siemens Networks (NSN)—that sold networking equipment. NSN had been undergoing a massive turnaround and cost-reduction program, steadily improving its results.

When Microsoft expressed interest in taking over Nokia’s device business, Nokia chairman Risto Siilasmaa took the initiative. Over the course of six months, he and the executive team evaluated several alternatives and shaped a deal that would radically change Nokia’s trajectory: selling the mobile business to Microsoft. In parallel, Nokia CFO Timo Ihamuotila orchestrated another deal to buy out Siemens from the NSN joint venture, giving Nokia 100 percent control over the unit and forming the cash-generating core of the new Nokia. These deals have proved essential for Nokia to fund the journey. They were well-timed, well-executed moves at the right terms.

Right after these radical announcements, Nokia embarked on a strategy-led design period to win in the medium term with new people and a new organization, with Risto Siilasmaa as chairman and interim CEO. Nokia set up a new portfolio strategy, corporate structure, capital structure, robust business plans, and management team with president and CEO Rajeev Suri in charge. Nokia focused on delivering excellent operational results across its portfolio of three businesses while planning its next move: a leading position in technologies for a world in which everyone and everything will be connected.

Nokia’s share price has steadily climbed. Its enterprise value has grown 12-fold since bottoming out in July 2012. The company has returned billions of dollars of cash to its shareholders and is once again the most valuable company in Finland. The next few years will demonstrate how this chapter in Nokia’s 150-year history of serial transformation will again reinvent the company.

Managing Director & Senior Partner

San Francisco - Bay Area

Managing Director & Senior Partner, Chairman of the BCG Henderson Institute

ABOUT BOSTON CONSULTING GROUP

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empowering organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

© Boston Consulting Group 2024. All rights reserved.

For information or permission to reprint, please contact BCG at [email protected] . To find the latest BCG content and register to receive e-alerts on this topic or others, please visit bcg.com . Follow Boston Consulting Group on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) .

Subscribe to our Business Transformation E-Alert.

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Teaching Resources Library

Strategy Case Studies

7 Favorite Business Case Studies to Teach—and Why

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Course Materials

FEATURED CASE STUDIES

The Army Crew Team . Emily Michelle David of CEIBS

ATH Technologies . Devin Shanthikumar of Paul Merage School of Business

Fabritek 1992 . Rob Austin of Ivey Business School

Lincoln Electric Co . Karin Schnarr of Wilfrid Laurier University

Pal’s Sudden Service—Scaling an Organizational Model to Drive Growth . Gary Pisano of Harvard Business School

The United States Air Force: ‘Chaos’ in the 99th Reconnaissance Squadron . Francesca Gino of Harvard Business School

Warren E. Buffett, 2015 . Robert F. Bruner of Darden School of Business

To dig into what makes a compelling case study, we asked seven experienced educators who teach with—and many who write—business case studies: “What is your favorite case to teach and why?”

The resulting list of case study favorites ranges in topics from operations management and organizational structure to rebel leaders and whodunnit dramas.

1. The Army Crew Team

Emily Michelle David, Assistant Professor of Management, China Europe International Business School (CEIBS)

“I love teaching The Army Crew Team case because it beautifully demonstrates how a team can be so much less than the sum of its parts.

I deliver the case to executives in a nearby state-of-the-art rowing facility that features rowing machines, professional coaches, and shiny red eight-person shells.

After going through the case, they hear testimonies from former members of Chinese national crew teams before carrying their own boat to the river for a test race.

The rich learning environment helps to vividly underscore one of the case’s core messages: competition can be a double-edged sword if not properly managed.

Executives in Emily Michelle David’s organizational behavior class participate in rowing activities at a nearby facility as part of her case delivery.

Despite working for an elite headhunting firm, the executives in my most recent class were surprised to realize how much they’ve allowed their own team-building responsibilities to lapse. In the MBA pre-course, this case often leads to a rich discussion about common traps that newcomers fall into (for example, trying to do too much, too soon), which helps to poise them to both stand out in the MBA as well as prepare them for the lateral team building they will soon engage in.

Finally, I love that the post-script always gets a good laugh and serves as an early lesson that organizational behavior courses will seldom give you foolproof solutions for specific problems but will, instead, arm you with the ability to think through issues more critically.”

2. ATH Technologies

Devin Shanthikumar, Associate Professor of Accounting, Paul Merage School of Business

“As a professor at UC Irvine’s Paul Merage School of Business, and before that at Harvard Business School, I have probably taught over 100 cases. I would like to say that my favorite case is my own, Compass Box Whisky Company . But as fun as that case is, one case beats it: ATH Technologies by Robert Simons and Jennifer Packard.

ATH presents a young entrepreneurial company that is bought by a much larger company. As part of the merger, ATH gets an ‘earn-out’ deal—common among high-tech industries. The company, and the class, must decide what to do to achieve the stretch earn-out goals.

ATH captures a scenario we all want to be in at some point in our careers—being part of a young, exciting, growing organization. And a scenario we all will likely face—having stretch goals that seem almost unreachable.

It forces us, as a class, to really struggle with what to do at each stage.

After we read and discuss the A case, we find out what happens next, and discuss the B case, then the C, then D, and even E. At every stage, we can:

see how our decisions play out,

figure out how to build on our successes, and

address our failures.

The case is exciting, the class discussion is dynamic and energetic, and in the end, we all go home with a memorable ‘ah-ha!’ moment.

I have taught many great cases over my career, but none are quite as fun, memorable, and effective as ATH .”

3. Fabritek 1992

Rob Austin, Professor of Information Systems, Ivey Business School

“This might seem like an odd choice, but my favorite case to teach is an old operations case called Fabritek 1992 .

The latest version of Fabritek 1992 is dated 2009, but it is my understanding that this is a rewrite of a case that is older (probably much older). There is a Fabritek 1969 in the HBP catalog—same basic case, older dates, and numbers. That 1969 version lists no authors, so I suspect the case goes even further back; the 1969 version is, I’m guessing, a rewrite of an even older version.

There are many things I appreciate about the case. Here are a few:

It operates as a learning opportunity at many levels. At first it looks like a not-very-glamorous production job scheduling case. By the end of the case discussion, though, we’re into (operations) strategy and more. It starts out technical, then explodes into much broader relevance. As I tell participants when I’m teaching HBP's Teaching with Cases seminars —where I often use Fabritek as an example—when people first encounter this case, they almost always underestimate it.

It has great characters—especially Arthur Moreno, who looks like a troublemaker, but who, discussion reveals, might just be the smartest guy in the factory. Alums of the Harvard MBA program have told me that they remember Arthur Moreno many years later.

Almost every word in the case is important. It’s only four and a half pages of text and three pages of exhibits. This economy of words and sparsity of style have always seemed like poetry to me. I should note that this super concise, every-word-matters approach is not the ideal we usually aspire to when we write cases. Often, we include extra or superfluous information because part of our teaching objective is to provide practice in separating what matters from what doesn’t in a case. Fabritek takes a different approach, though, which fits it well.

It has a dramatic structure. It unfolds like a detective story, a sort of whodunnit. Something is wrong. There is a quality problem, and we’re not sure who or what is responsible. One person, Arthur Moreno, looks very guilty (probably too obviously guilty), but as we dig into the situation, there are many more possibilities. We spend in-class time analyzing the data (there’s a bit of math, so it covers that base, too) to determine which hypotheses are best supported by the data. And, realistically, the data doesn’t support any of the hypotheses perfectly, just some of them more than others. Also, there’s a plot twist at the end (I won’t reveal it, but here’s a hint: Arthur Moreno isn’t nearly the biggest problem in the final analysis). I have had students tell me the surprising realization at the end of the discussion gives them ‘goosebumps.’

Finally, through the unexpected plot twist, it imparts what I call a ‘wisdom lesson’ to young managers: not to be too sure of themselves and to regard the experiences of others, especially experts out on the factory floor, with great seriousness.”

4. Lincoln Electric Co.

Karin Schnarr, Assistant Professor of Policy, Wilfrid Laurier University

“As a strategy professor, my favorite case to teach is the classic 1975 Harvard case Lincoln Electric Co. by Norman Berg.

I use it to demonstrate to students the theory linkage between strategy and organizational structure, management processes, and leadership behavior.

This case may be an odd choice for a favorite. It occurs decades before my students were born. It is pages longer than we are told students are now willing to read. It is about manufacturing arc welding equipment in Cleveland, Ohio—a hard sell for a Canadian business classroom.

Yet, I have never come across a case that so perfectly illustrates what I want students to learn about how a company can be designed from an organizational perspective to successfully implement its strategy.

And in a time where so much focus continues to be on how to maximize shareholder value, it is refreshing to be able to discuss a publicly-traded company that is successfully pursuing a strategy that provides a fair value to shareholders while distributing value to employees through a large bonus pool, as well as value to customers by continually lowering prices.

However, to make the case resonate with today’s students, I work to make it relevant to the contemporary business environment. I link the case to multimedia clips about Lincoln Electric’s current manufacturing practices, processes, and leadership practices. My students can then see that a model that has been in place for generations is still viable and highly successful, even in our very different competitive situation.”

5. Pal’s Sudden Service—Scaling an Organizational Model to Drive Growth

Gary Pisano, Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

“My favorite case to teach these days is Pal’s Sudden Service—Scaling an Organizational Model to Drive Growth .

I love teaching this case for three reasons:

1. It demonstrates how a company in a super-tough, highly competitive business can do very well by focusing on creating unique operating capabilities. In theory, Pal’s should have no chance against behemoths like McDonalds or Wendy’s—but it thrives because it has built a unique operating system. It’s a great example of a strategic approach to operations in action.

2. The case shows how a strategic approach to human resource and talent development at all levels really matters. This company competes in an industry not known for engaging its front-line workers. The case shows how engaging these workers can really pay off.

3. Finally, Pal’s is really unusual in its approach to growth. Most companies set growth goals (usually arbitrary ones) and then try to figure out how to ‘backfill’ the human resource and talent management gaps. They trust you can always find someone to do the job. Pal’s tackles the growth problem completely the other way around. They rigorously select and train their future managers. Only when they have a manager ready to take on their own store do they open a new one. They pace their growth off their capacity to develop talent. I find this really fascinating and so do the students I teach this case to.”

6. The United States Air Force: ‘Chaos’ in the 99th Reconnaissance Squadron

Francesca Gino, Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

“My favorite case to teach is The United States Air Force: ‘Chaos’ in the 99th Reconnaissance Squadron .

The case surprises students because it is about a leader, known in the unit by the nickname Chaos , who inspired his squadron to be innovative and to change in a culture that is all about not rocking the boat, and where there is a deep sense that rules should simply be followed.

For years, I studied ‘rebels,’ people who do not accept the status quo; rather, they approach work with curiosity and produce positive change in their organizations. Chaos is a rebel leader who got the level of cultural change right. Many of the leaders I’ve met over the years complain about the ‘corporate culture,’ or at least point to clear weaknesses of it; but then they throw their hands up in the air and forget about changing what they can.

Chaos is different—he didn’t go after the ‘Air Force’ culture. That would be like boiling the ocean.

Instead, he focused on his unit of control and command: The 99th squadron. He focused on enabling that group to do what it needed to do within the confines of the bigger Air Force culture. In the process, he inspired everyone on his team to be the best they can be at work.

The case leaves the classroom buzzing and inspired to take action.”

7. Warren E. Buffett, 2015

Robert F. Bruner, Professor of Business Administration, Darden School of Business

“I love teaching Warren E. Buffett, 2015 because it energizes, exercises, and surprises students.

Buffett looms large in the business firmament and therefore attracts anyone who is eager to learn his secrets for successful investing. This generates the kind of energy that helps to break the ice among students and instructors early in a course and to lay the groundwork for good case discussion practices.

Studying Buffett’s approach to investing helps to introduce and exercise important themes that will resonate throughout a course. The case challenges students to define for themselves what it means to create value. The case discussion can easily be tailored for novices or for more advanced students.

Either way, this is not hero worship: The case affords a critical examination of the financial performance of Buffett’s firm, Berkshire Hathaway, and reveals both triumphs and stumbles. Most importantly, students can critique the purported benefits of Buffett’s conglomeration strategy and the sustainability of his investment record as the size of the firm grows very large.

By the end of the class session, students seem surprised with what they have discovered. They buzz over the paradoxes in Buffett’s philosophy and performance record. And they come away with sober respect for Buffett’s acumen and for the challenges of creating value for investors.

Surely, such sobriety is a meta-message for any mastery of finance.”

More Educator Favorites

Emily Michelle David is an assistant professor of management at China Europe International Business School (CEIBS). Her current research focuses on discovering how to make workplaces more welcoming for people of all backgrounds and personality profiles to maximize performance and avoid employee burnout. David’s work has been published in a number of scholarly journals, and she has worked as an in-house researcher at both NASA and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Devin Shanthikumar is an associate professor and the accounting area coordinator at UCI Paul Merage School of Business. She teaches undergraduate, MBA, and executive-level courses in managerial accounting. Shanthikumar previously served on the faculty at Harvard Business School, where she taught both financial accounting and managerial accounting for MBAs, and wrote cases that are used in accounting courses across the country.

Robert D. Austin is a professor of information systems at Ivey Business School and an affiliated faculty member at Harvard Medical School. He has published widely, authoring nine books, more than 50 cases and notes, three Harvard online products, and two popular massive open online courses (MOOCs) running on the Coursera platform.

Karin Schnarr is an assistant professor of policy and the director of the Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) program at the Lazaridis School of Business & Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, Canada where she teaches strategic management at the undergraduate, graduate, and executive levels. Schnarr has published several award-winning and best-selling cases and regularly presents at international conferences on case writing and scholarship.

Gary P. Pisano is the Harry E. Figgie, Jr. Professor of Business Administration and senior associate dean of faculty development at Harvard Business School, where he has been on the faculty since 1988. Pisano is an expert in the fields of technology and operations strategy, the management of innovation, and competitive strategy. His research and consulting experience span a range of industries including aerospace, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, specialty chemicals, health care, nutrition, computers, software, telecommunications, and semiconductors.

Francesca Gino studies how people can have more productive, creative, and fulfilling lives. She is a professor at Harvard Business School and the author, most recently, of Rebel Talent: Why It Pays to Break the Rules at Work and in Life . Gino regularly gives keynote speeches, delivers corporate training programs, and serves in advisory roles for firms and not-for-profit organizations across the globe.

Robert F. Bruner is a university professor at the University of Virginia, distinguished professor of business administration, and dean emeritus of the Darden School of Business. He has also held visiting appointments at Harvard and Columbia universities in the United States, at INSEAD in France, and at IESE in Spain. He is the author, co-author, or editor of more than 20 books on finance, management, and teaching. Currently, he teaches and writes in finance and management.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- Boston University Libraries

Business Case Studies

Open access cases.

- Getting Started

- Harvard Business School Cases

- Diverse Business Cases

- Databases with Cases

- Journals with Cases

- Books with Cases

- Case Analysis

- Case Interviews

- Case Method (Teaching)

- Writing Case Studies

- Citing Business Sources

A number of universities and organizations provide access to free business case studies. Below are some of the best known sources.

- << Previous: Books with Cases

- Next: Case Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Nov 17, 2023 12:09 PM

- URL: https://library.bu.edu/business-case-studies

Case Studies in Business Management, Strategy, Corporate Strategy, Marketing, Leadership, CSR, MBA Case Studies

Ibs ® case development centre, asia-pacific's largest repository of management case studies.

Forgot Password | Change Password

MBA Course Case Maps

- Business Models

- Blue Ocean Strategy

- Competition & Strategy ⁄ Competitive Strategies

- Core Competency & Competitive Advantage

- Corporate Strategy

- Corporate Transformation

- Diversification Strategies

- Going Global & Managing Global Businesses

- Growth Strategies

- Industry Analysis

- Managing In Troubled Times ⁄ Managing a Crisis ⁄ Product Recalls

- Market Entry Strategies

- Mergers, Acquisitions & Takeovers

- Product Recalls

- Restructuring / Turnaround Strategies

- Strategic Alliances, Collaboration & Joint Ventures

- Supply Chain Management

- Value Chain Analysis

- Vision, Mission & Goals

- Global Retailers

- Indian Retailing

- Brands & Branding and Private Labels

- Brand ⁄ Marketing Communication Strategies and Advertising & Promotional Strategies

- Consumer Behaviour

- Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

- Marketing Research

- Marketing Strategies ⁄ Strategic Marketing

- Positioning, Repositioning, Reverse Positioning Strategies

- Sales & Distribution

- Services Marketing

- Economic Crisis

- Fiscal Policy

- Government & Business Environment

- Macroeconomics

- Micro ⁄ Business ⁄ Managerial Economics

- Monetary Policy

- Public-Private Partnership

- Financial Management & Corporate Finance

- Investment & Banking

- Leadership,Organizational Change & CEOs

- Succession Planning

- Corporate Governance & Business Ethics

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- International Trade & Finance

- Entrepreneurship

- Family Businesses

- Social Entrepreneurship

- HRM ⁄ Organizational Behaviour

- Innovation & New Product Development

- Business Research Methods

- Operations & Project Management

- Operations Management

- Quantitative Methods

- Social Networking

- China-related Cases

- India-related Cases

- Women Executives ⁄ CEO's

- Course Case Maps

- Effective Executive Interviews

- Video Interviews

Executive Brief

- Movie Based Case Studies

- Case Catalogues

- Case studies in Other Languages

- Multimedia Case Studies

- Textbook Adoptions

- Customized Categories

- Free Case Studies

- Faculty Zone

- Student Zone

- By CaseCode

- By CaseTitle

- By Industry

- By Keywords

Case Categories

- Corporate Governance & Business Ethics

- Government & Business Environment

- Micro \ Business \ Managerial Economics

- Finance, Accounting & Control

- Financial Management & Corporate Finance

- Investment and Banking

- Human Resource Management (HRM) \ Organizational Behaviour

- Innovation & New Product Development

- International Trade & Finance

- Leadership, Organizational Change and CEOs

- Brands & Branding and Private Labels

- Brand \ Marketing Communication Strategies and Advertising & Promotional Strategies

- Marketing Strategies \ Strategic Marketing

- Sales & Distribution

- Competition & Strategy \ Competitive Strategies

- Core Competency & Competitive Advantage

- Going Global & Managing Global Businesses

- Managing In Troubled Times \ Managing a Crisis

- Mergers, Acquisitions & Takeovers

- Strategic Alliances, Collaboration & Joint Ventures

- Vision, Mission & Goals

- Operations & Project Management

- China-related cases

- India-related cases

- Women Executives/CEO's

- Aircraft & Ship Building

- Automobiles

- Home Appliances & Personal Care Products

- Minerals, Metals & Mining

- Engineering, Electrical & Electronics

- Building Materials & Construction Equipment

- Food, Diary & Agriculture Products

- Oil & Natural Gas

- Office Equipment

- Banking, Insurance & Financial Services

- Telecommunications

- e-commerce & Internet

- Freight &l Courier

- Movies,Music, Theatre & Circus

- Video Games

- Broadcasting

- Accessories & Luxury Goods

- Accounting & Audit

- IT Consulting

- Corporate Consulting

- Advertising

- IT and ITES

- Hotels & Resorts

- Theme Parks

- Health Care

- Sports & Sports Related

- General Business

- Business Law, Corporate Governence & Ethics

- Conglomerates

Companies & Organizations

- Aditya Birla Group

Useful Links

- How to buy case studies?

- Pricing Information

Advertisement

Popular searches.

- For reprint requests in a text book or a case book, please write to [email protected]. The reprint permission given will be for one time use and non-exclusive rights will be provided to publish the case. The copyright will remain with IBS Case Development Centre (IBSCDC).

- Customer can also buy reprint permissions to use the selected case(s) in classroom for one year period from the time of purchase and a maximum of 200 copies.

* Teaching Note Teaching Notes will be provided only to Faculty Members and Course/ Training Instructors. Please e-mail us your request, with complete information about your Designation, institution, website address, contacts details including telephone number. And personal web pages and official e-mail id for verification. Please note that a complimentary copy of the teaching note will be provided to a Faculty Members and Course/Training Instructors who purchases minimum of 10 copies of a case study.

Recently Bought Cases

- SSSs Experiment: Choosing an Appropriate Research Design

- Differentiating Services: Yatra.coms Click and MortarModel

- Wedding Services Business in India: Led by Entrepreneurs

- Shinsei Bank - A Turnaround

- Accentures Grand Vision: Corporate Americas Superstar Maker

- Tata Groups Strategy: Ratan Tatas Vision

- MindTree Consulting: Designing and Delivering its Mission and Vision

- Coca-Cola in India: Innovative Distribution Strategies with 'RED' Approach

- IndiGos Low-Cost Carrier Operating Model: Flying High in Turbulent Skies

- Evaluation of GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited (GHIAL)

- Ambuja Cements: Weighted Average Cost of Capital

- Walmart-Bharti Retail Alliance in India: The Best Way Forward?

- Exploring Primary and Secondary Data: Lessons to Learn

- Global Inflationary Trends: Raising Pressure on Central Banks

- Performance Management System@TCS

- Violet Home Theater System: A Sound Innovation

- Consumers Perception on Inverters in India: A Factor Analysis Case

- Demand Forecasting of Magic Foods using Multiple Regression Analysis Technique

- Saturn Clothing Company: Measuring Customer Satisfaction using Likert Scaling

Best Selling Cases

- Xerox�s Turnaround: Anne Mulcahy�s �Organizational Change�

- IKEA in Japan: The Market Re-entry Strategies

- Leadership Conundrum: Nike After Knight

- Nintendo�s Innovation Strategies: A Sustainable Competitive Advantage?

- Perfect Competition under eBay: A Fact or a Factoid?

- Googles HR Practices: A Strategic Edge?

- H&M vs Zara: Competitive Growth Strategies

Keep up with IBSCDC

- Email Newsletters

- IBSCDC on Twitter

- IBSCDC on Facebook

- IBSCDC on YouTube

Video Inerviews

Executive inerviews, case studies on.

- View all Casebooks »

Course Case Mapping For

- View All Course Casemaps »

- View all Video Interviews »

- View all Executive Briefs »

- View All Executive Interviews »

Advetisement

Contact us: IBS Case Development Centre (IBSCDC), IFHE Campus, Donthanapally, Sankarapally Road, Hyderabad-501203, Telangana, INDIA. Mob: +91- 9640901313 E-mail: [email protected]

Business Process Management (BPM) is a systematic approach to managing and streamlining business processes . BPM is intended to help improve the efficiency of existing processes, with the goal of increasing productivity and overall business performance.

BPM is often confused with other seemingly similar initiatives. For example, BPM is smaller in scale than business process reengineering (BPR), which radically overhauls or replaces processes. Conversely, it has a larger scope than task management, which deals with individual tasks, and project management, which handles one-time initiatives. And while enterprise resource planning (ERP) integrates and manages all aspects of a business, BPM focuses on its individual functions—optimizing the organization’s existing, repeatable processes end-to-end.

An effective BPM project employs structured processes, uses appropriate technologies and fosters collaboration among team members. It enables organizations to streamline project workflows, enhance productivity and consistently deliver value to stakeholders. Ultimately, the successful implementation of BPM tools can lead to increased customer satisfaction, competitive advantage and improved business outcomes.

3 main types of business process management

Integration-centric BPM focuses on processes that don’t require much human involvement. These include connecting different systems and software to streamline processes and improve data flow across the organization, for example human resource management (HRM) or customer relationship management (CRM)

Human-centric BPM centers around human involvement, often where an approval process is required. Human-centric BPM prioritizes the designing of intuitive processes with drag and drop features that are easy for people to use and understand, aiming to enhance productivity and collaboration among employees.

Document-centric BPM is for efficiently managing documents and content—such as contracts—within processes. A purchasing agreement between a client and vendor, for example, needs to evolve and go through different rounds of approval and be organized, accessible and compliant with regulations.

Business process management examples

BPM can help improve overall business operations by optimizing various business processes. Here are some BPM examples that outline the use cases and benefits of BPM methodology:

Business strategy

BPM serves as a strategic tool for aligning business processes with organizational goals and objectives. By connecting workflow management, centralizing data management , and fostering collaboration and communication, BPM enables organizations to remain competitive by providing access to accurate and timely data. This ensures that strategic decisions are based on reliable insights.

Through BPM, disparate data sources—including spend data, internal performance metrics and external market research—can be connected. This can uncover internal process improvements, strategic partnership opportunities and potential cost-saving initiatives. BPM also provides the foundation for making refinements and enhancements that lead to continuous improvement.

- Enhanced decision-making

- Efficient optimization

- Continuous improvement

Claims management

BPM can be used to standardize and optimize the claims process from start to finish. BPM software can automate repetitive tasks such as claim intake, validation, assessment, and payment processing—using technology such as Robotic Process Automation (RPA ). By establishing standardized workflows and decision rules, BPM streamlines the claims process by reducing processing times and minimizing errors. BPM can also provide real-time visibility into claim status and performance metrics. This enables proactive decision-making, ensures consistency and improves operational efficiency.

- Automated claim processing

- Reduced processing times

- Enhanced visibility

Compliance and risk management

By automating routine tasks and implementing predefined rules, BPM enables timely compliance with regulatory requirements and internal policies. Processes such as compliance checks, risk evaluations and audit trails can be automated by using business process management software, and organizations can establish standardized workflows for identifying, assessing, and mitigating compliance risks. Also, BPM provides real-time insights into compliance metrics and risk exposure, enabling proactive risk management and regulatory reporting.

- Automated compliance checks

- Real-time insights into risk exposure

- Enhanced regulatory compliance

Contract management

Contract turnaround times can be accelerated, and administrative work can be reduced by automating tasks such as document routing, approval workflows and compliance checks. Processes such as contract drafting, negotiation, approval, and execution can also be digitized and automated. Standardized workflows can be created that guide contracts through each stage of the lifecycle. This ensures consistency and reduces inefficiency. Real-time visibility into contract status improves overall contract management.

- Accelerated contract turnaround times

- Real-time visibility into contract status

- Strengthened business relationships

Customer service

BPM transforms customer service operations by automating service request handling, tracking customer interactions, and facilitating resolution workflows. Through BPM, organizations can streamline customer support processes across multiple channels, including phone, email, chat, and social media. With BPM, routine tasks such as ticket routing and escalation are automated. Notifications can be generated to update customers about the status of their requests. This reduces response times and improves customer experience by making service more consistent. BPM also provides agents with access to a centralized knowledge base and customer history, enabling them to resolve inquiries more efficiently and effectively.

- Streamlined service request handling

- Centralized knowledge base access

- Enhanced customer satisfaction and loyalty

Financial management

BPM is used to streamline financial processes such as budgeting, forecasting, expense management, and financial reporting. It ensures consistency and accuracy in financial processes by establishing standardized workflows and decision rules, reducing the risk of human errors and improving regulatory compliance. BPM uses workflow automation to automate repetitive tasks such as data entry, reconciliation and report generation. Real-time visibility into financial data enables organizations to respond quickly to changing market conditions.

- Increased operational efficiency

- Instant insights for informed decision-making

- Enhanced compliance with regulations and policies

Human resources

Using BPM, organizations can implement standardized HR workflows that guide employees through each stage of their employment experience, from recruitment to retirement . The new employee onboarding process and performance evaluations can be digitized, which reduces administrative work and allows team members to focus on strategic initiatives such as talent development and workforce planning. Real-time tracking of HR metrics provides insights into employee engagement, retention rates, and the use and effectiveness of training.

- Reduced administrative work

- Real-time tracking of HR metrics

- Enhanced employee experience

Logistics management

BPM optimizes logistics management by automating processes such as inventory management, order fulfillment, and shipment tracking, including those within the supply chain. Workflows can be established that govern the movement of goods from supplier to customer. Automating specific tasks such as order processing, picking, packing and shipping reduces cycle times and improves order accuracy. BPM can also provide real-time data for inventory levels and shipment status, which enables proactive decision-making and exception management.

- Streamlined order processing and fulfillment

- Real-time visibility into inventory and shipments

- Enhanced customer satisfaction and cost savings

Order management

BPM streamlines processes such as order processing, tracking, and fulfillment. BPM facilitates business process automation —the automation of routine tasks such as order entry, inventory management, and shipping, reducing processing times and improving order accuracy. By establishing standardized workflows and rules, BPM ensures consistency and efficiency throughout the order lifecycle. Increased visibility of order status and inventory levels enables proactive decision-making and exception management.

- Automated order processing

- Real-time visibility into order status

- Improved customer satisfaction

Procurement management

BPM revolutionizes procurement management through the digital transformation and automation of processes such as vendor selection, purchase requisition, contract management, and pricing negotiations. Workflows can be established that govern each stage of the procurement lifecycle, from sourcing to payment. By automating tasks such as supplier qualification, RFx management, and purchase order processing, BPM reduces cycle times and improves efficiency. Also, with real-time metrics such as spend analysis, supplier performance, and contract compliance, BPM enables business process improvement by providing insights into areas suitable for optimization.

- Standardized procurement workflows

- Real-time insights into procurement metrics

- Cost savings and improved supplier relationships

Product lifecycle management

BPM revolutionizes product lifecycle management by digitizing and automating processes such as product design, development, launch, and maintenance. Workflows that govern each stage of the product lifecycle, from ideation to retirement can be standardized. Requirements gathering, design reviews, and change management , can be automated. This accelerates time-to-market and reduces development costs. BPM can also encourage cross-functional collaboration among product development teams, which ensures alignment and transparency throughout the process.

- Accelerated time-to-market

- Reduced development costs

- Enhanced cross-functional collaboration

Project management

In the beginning of this page, we noted that BPM is larger in scale than project management. In fact, BPM can be used to improve the project management process. Business process management tools can assign tasks, track progress, identify bottlenecks and allocate resources. Business process modeling helps in visualizing and designing new workflows to guide projects through each stage of the BPM lifecycle. This ensures consistency and alignment with project objectives. Tasks assignments, scheduling, and progress monitoring can be automated, which reduces administrative burden and improves efficiency. Also, resource utilization and project performance can be monitored in real time to make sure resources are being used efficiently and effectively.

- Streamlined project workflows

- Real-time insights into project performance

- Enhanced stakeholder satisfaction

Quality assurance management

BPM facilitates the automation of processes such as quality control, testing, and defect tracking, while also providing insights into KPIs such as defect rates and customer satisfaction scores. Quality assurance (QA) process steps are guided by using standardized workflows to ensure consistency and compliance with quality standards. Metrics and process performance can be tracked in real time to enable proactive quality management. Process-mapping tools can also help identify inefficiencies, thereby fostering continuous improvement and QA process optimization.

- Automated quality control processes

- Real-time visibility into quality metrics

Business process management examples: Case studies

Improving procure-to-pay in state government.

In 2020, one of America’s largest state governments found itself in search of a new process analysis solution . The state had integrated a second management system into its procurement process, which required the two systems, SAP SRM and SAP ECC, to exchange data in real time. With no way to analyze the collected data, the state couldn’t monitor the impact of its newly integrated SAP SRM system, nor detect deviations during the procurement process. This created an expensive problem.

The state used IBM Process Mining to map out its current workflow and track the progress of the SAP SRM system integration. Using the software’s discovery tool, data from both management systems was optimized to create a single, comprehensive process model. With the end-to-end process mapped out, the state was able to monitor all its process activities and review the performance of specific agencies.

Streamlining HR at Anheuser-Busch

AB InBev wanted to streamline its complicated HR landscape by implementing a singular global solution to support employees and improve their experience, and it selected workday as its human capital management (HCM) software. Working with a team from IBM® Workday consulting services , part of IBM Consulting™, AB InBev worked with IBM to remediate the integration between the legacy HR apps and the HCM software.

What was once a multi-system tool with unorganized data has become a single source of truth, enabling AB InBev to run analytics for initiatives like examining employee turnover at a local scale. Workday provides AB InBev with a streamlined path for managing and analyzing data, ultimately helping the company improve HR processes and reach business goals.

Business process management and IBM

Effective business process management (BPM) is crucial for organizations to achieve more streamlined operations and enhance efficiency. By optimizing processes, businesses can drive growth, stay competitive and realize sustainable success.

IBM Consulting offers a range of solutions to make your process transformation journey predictable and rewarding.

- Traditional AI and generative AI-enabled Process Excellence practice uses the leading process mining tools across the IBM ecosystem and partners.

- Our patented IBM PEX Value Triangle includes industry standards, benchmarks, and KPIs and is used to quickly identify process performance issues and assess where and how our clients can optimize and automate everywhere possible.

- IBM Automation Quotient Framework and Digital Center of Excellence (COE) platform prioritized and speeds up automation opportunities, ultimately establishing a Process Excellence COE for continuous value orchestration and governance across your organization.

Key improvements might include 60-70% faster procurement, faster loan booking, and reduced finance rework rate, along with risk avoidance, and increased customer and employee satisfaction.

With principles grounded in open innovation, collaboration and trust, IBM Consulting doesn’t just advise clients. We work side by side to design, build, and operate high-performing businesses—together with our clients and partners.

More from Business transformation

Using generative ai to accelerate product innovation.

3 min read - Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) can be a powerful tool for driving product innovation, if used in the right ways. We’ll discuss select high-impact product use cases that demonstrate the potential of AI to revolutionize the way we develop, market and deliver products to customers. Stacking strong data management, predictive analytics and GenAI is foundational to taking your product organization to the next level. 1. Addressing customer inquiries with an AI-driven chatbot ChatGPT distinguished itself as the first publicly accessible GenAI-powered…

Integrating AI into Asset Performance Management: It’s all about the data

3 min read - Imagine a future where artificial intelligence (AI) seamlessly collaborates with existing supply chain solutions, redefining how organizations manage their assets. If you’re currently using traditional AI, advanced analytics, and intelligent automation, aren’t you already getting deep insights into asset performance? Undoubtedly. But what if you could optimize even further? That’s the transformative promise of generative AI, which is beginning to revolutionize business operations in game-changing ways. It may be the solution that finally breaks through dysfunctional silos of business units,…

Create a lasting customer retention strategy

6 min read - Customer retention must be a top priority for leaders of any company wanting to remain competitive. An effective customer retention strategy should support the company to maintain a healthy stable of loyal customers and bring in new customers. Generating repeat business is critical: McKinsey’s report on customer acquisition states (link resides outside of ibm.com) that companies need to acquire three new customers to make up the business value of losing one existing customer. Customer retention has become more difficult in…

IBM Newsletters

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Corporate Governance Can Be a Growth Strategy

In order to attract new customers across South America, private asset management firm Capital SAFI strengthened its governance.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

Jorge Quintanilla Nielsen started the private asset management firm Capital SAFI in 2007 — and planned to expand from Bolivia across South America. As a private firm, Capital SAFI isn’t required to have a board, but he knew that governance would be one of the main aspects potential partners would evaluate.

In this episode, Harvard Business School professor V. G. Narayanan discusses his case, “Building the Governance to Take Capital SAFI to the Next Level.” He explains how Nielsen selects board members and holds them accountable in their roles. He also discusses how Capital SAFI’s board guides the firm’s growth, risks, and overall strategy.

Key episode topics include: strategy, corporate strategy, corporate governance, sustainable business practices, boards, investment management, growth strategy, global growth, assessing risk.

HBR On Strategy curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock new ways of doing business. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the original HBR Cold Call episode: Corporate Governance and Growth Strategy at Capital SAFI (2022)

- Find more episodes of Cold Call

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR On Strategy , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock new ways of doing business. Jorge Quintanilla Nielsen started the private asset management firm Capital SAFI in Bolivia in 2007 – and planned to expand across South America. But there was a problem. As a private firm, Capital SAFI isn’t required to have a board. To expand, Quintanilla Nielsen knew he needed to strengthen the firm’s governance. To do that, he recruited 6 board members and established a governance committee, an assessment process for the board, and succession plans for all board members and company executives. Today, we bring you a conversation about the role of corporate governance in growth strategy – with Harvard Business School professor V. G. Narayanan. Narayanan studied the evolution of Capital SAFI’s growth and governance and wrote a case about how the firm has used good corporate governance to attract new investors. In this episode, you’ll learn how Quintanilla Nielsen seeks board members with a variety of perspectives. You’ll also learn how the board guides the firm’s growth, risks, and overall strategy. This episode originally aired on Cold Call in October 2022. Here it is.

BRIAN KENNY: Hey, Cold Call listeners. If you’re anything like me, you may have daydreamed about what it would be like to step back from your daily grind and ease into semi-retirement by sitting on a few corporate boards. I mean, how hard could it be? You go to a few meetings, ask a couple of questions to show that you read the prep materials, and collect a sizable check for your efforts. Well, I hate to burst your bubble, but corporate governance ain’t what it used to be. According to Fortune magazine, in 2021, board meetings increased by 19% – and tensions are high with 47% of board leaders saying they wish that a fellow director would quit. And they’re expected to know a lot about technology, strategy, finance, operations, and people. As if that weren’t enough board members face growing pressure to act on environmental, social, and governance issues. Gone are the days of shareholder primacy. The fact is that these days, corporate boards are expected to earn their keep. And that can be a good thing for the rest of us. Today on Cold Call we’ve invited Professor V.G. Narayanan to discuss the case entitled, “Building the Governance to Take Capital SAFI to the Next Level.” I’m your host, Brian Kenny, and you’re listening to Cold Call on the HBR Presents Network. V.G. Narayanan studies management accounting with a particular focus on performance evaluation and incentives. He’s a first timer on Cold Call. V.G., thanks for joining me today.

V.G. NARAYANAN: My pleasure, Brian.

BRIAN KENNY: This is a really interesting case and we were hoping to have the protagonist here with us today, Jorge Quintanilla Nielsen. Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to join us at the last minute, but I know you can tell the story. You wrote the case. You had two co-authors joining you on the case. One is Asis Martínez-Jerez, the other is Mariana Cal. So this is a case that takes place in Bolivia. And we’re going to talk about corporate governance as it applies there, but I think the lessons that come out of the case are broader and can apply to corporate governance anywhere. Let me ask you to start just by telling us what the central theme of the case is. And what’s your cold call when you start the case in class?

V.G. NARAYANAN: So, let me start with the second question – what’s my cold call? I cold call a student and I’d want them to say, “What changes would you make to corporate governance at Capital SAFI?” I like to start with an action-oriented cold call, and so this puts them on the spot. And it’s a little bit of a red herring because I think this is very, very good. So, I’m filled with extreme curiosity to know what my students are going to say on how to improve this, because if I knew what would improve corporate governance here, I would’ve already told Capital SAFI because Jorge was my student in GMP and the AMP. So I wrote this case because I thought they’re doing something terrific and amazing in terms of corporate governance.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. And how does this relate to the kind of things that you think about as a scholar?

V.G. NARAYANAN: So, for me, this is a very good lab. Because it’s a private company, it’s not required to do most of the things that it does in the realm of corporate governance. Yet, we see mostly corporate governance and public companies, and we never ask the question, Are those institutions there, are those practices there because they required to have those? You know? Maybe regulatory overreach? Or is this something inherently valuable that even in the absence of regulation, some of these things would be there? So, that’s why this is very interesting for me to see a private company that has sort of gone beyond what they’re required to do because they see inherent value in good corporate governance.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. And I think that corporate governance is one of those topics that people don’t necessarily spend a lot of time thinking about. They know there’s a board there. They don’t really know necessarily what the board does. And I was being a little sarcastic in my opening, but I do think people see it as kind of a cushy job. Well, if they read this case, they won’t think that anymore. Right?

V.G. NARAYANAN: Well, particularly if you’re not required to do it, you’re going to be very careful that you get what you pay for. So, you are going to be very demanding of your board. And be careful what you ask for. When the board shows up, they’re going to be demanding of you. It’s like holding each other accountable and to a high standard. And that’s precisely what they’ve done.

BRIAN KENNY: So, let’s talk a little bit about Capital SAFI. What business are they in? Just so our listeners kind of can ground themselves there. And they’re an investment firm, but what do they invest in?

V.G. NARAYANAN: So, they’re an asset management company and they invest a little bit more than half in private debt. They also have some sovereign debt and public debt, but I would primarily say they are in private debt in Bolivia, and they’re the largest such company in their segment. And they have like four funds within Capital SAFI that focus on four different sectors.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. And I mentioned Jorge. He is the protagonist in the case. He’s the founder of the firm. Can you tell us a little bit about his background and why he decided to start the firm?

V.G. NARAYANAN: I believe Jorge came to the US from Bolivia when he maybe was 14 years old or something. Completed school right here, and definitely entered his undergrad in Georgia. Then he went to Kellogg where he got his MBA. And he worked, I think, in the US for a while. And then he went back to South America, worked at Citibank. And I think the startup bug caught up with him and he wanted do something on his own. And he saw there were certain practices that he was familiar with, certain institutions that were happening that were not happening in his home country in Bolivia. So, he wanted to be the change that he wanted to see. So, he went back to Bolivia and set up Capital SAFI. There are a lot of things that he was pioneering like even the first commercial paper that was issued, things like that, and certainly setting up this asset management company is another one where he certainly one of the pioneers in Bolivia.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. I think the case mentions that his parents thought he was crazy not to stay. He was on a great path, he was with Goldman Sachs. Yeah.

V.G. NARAYANAN: He had excellent jobs. You know? He had a great educational qualification. I think his dad was a physician and mom was an artist. And so, a well-paying salary job was something that they thought, “Why would he walk away from that?” And he wanted to do something different.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. So, how is Capital SAFI different than other institutions like it in Bolivia? Are there things that make it sort of distinctive?

V.G. NARAYANAN: So, I would contrast them with other institutions in other developing countries more broadly than just Bolivia. I would say very often asset management companies or most companies tend to be part of a conglomerate, and it’s like so and so business house has this new asset management company. And that’s good for the investors because they know that name, that family name is behind this company. So they can invest more confidently. The regulators sort of know who they’re dealing with. And even the companies where they’re investing in, they know where the money is coming from. Right? So, all around, if you’re coming from a conglomerate, a business house, it’s sort of the known devil. Here’s a situation where Jorge doesn’t come from established family. And he’s sort of a professional manager trying to start something from ground up in a space where reputation is extremely important. You know? When it comes to dealing with other people’s money, everyone worries. The first thing is like, How is my money safe? The investors, the regulators, and even the companies where you’re investing your money, worry about who is this person behind the money. And so, reputation becomes important. So how do you crack this? Where do you start if you don’t have a reputation to build on that for the last several generations, your family’s like a well-known name? I think that’s where he was very clever to sort of use corporate governance, and board members, and professional management, and professional education to sort of make up for that. And in fact, sort of lead with your weakness is to convert that into strength. It’s to say, “We may not have been around for a hundred years, but, boy, everything we do is squeaky clean. And we are going to set the bar for professional management and corporate governance. And that’s what you’re going to trust.”

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. And squeaky clean matters a lot in this part of the world. We’ll talk about that in a little bit because corruption is a problem, not just there, but in many parts of the world.

V.G. NARAYANAN: Squeaky clean is important all over the world.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah, yeah, exactly. Well, how would Jorge’s team describe him? What kind of a leader is he?

V.G. NARAYANAN: So, I think they would describe him as very objective and data driven and very democratic. And if we are looking for a third adjective, I would say a big believer in empowerment, decentralization, and educating people that work for him. He is a strong believer in business education.

BRIAN KENNY: So, let’s talk about the board. Let’s talk a little bit about the composition of the board. But I’m wondering how he was able to convince people to join him in this effort and what his expectations are for them when they come onto the board.