010101.jpg)

Mastering Igbo: Your Guide to Learning Igbo Language for Beginners

Discover the rich cultural heritage of the igbo people through this beginner's guide to learning their language. from basic phrases to advanced vocabulary, we've got you covered. making it easy for anyone to start speaking this fascinating west african tongue..

Introduction

Welcome to the vibrant world of Igbo language! The rhythmic cadence of Igbo words dances on the tongue, an intricate tapestry woven from the vibrant cultures of southeastern Nigeria. Like unlocking an ancient linguistic treasure chest, each lesson unveils the secrets of this melodious language, transporting you to the very heart of Igbo identity.

Embark on a journey that awakens the senses, where the roll of the vowels mirrors the cadences of village storytellers, and the interplay of consonants echoes the rhythms of ceremonial drums. With patience and an open mind, the seeming complexities of Igbo unfold, revealing a world where communication transcends mere words to become a celebration of life itself.

In this guide, we'll walk you through the fundamentals of learning Igbo language for beginners, providing you with the tools and resources needed to embark on this exciting journey.

Getting Started with Igbo

Whether you're drawn to igbo for its musicality, cultural significance, or practical applications, diving into this language opens doors to new experiences and perspectives. taking those first few steps into the vibrant world of igbo feels like embarking on an linguistic adventure. the very alphabet seems to beckon you forth, its unique symbols and diacritics whispering of the richness to come., as you begin to wrap your tongue around basic greetings and pleasantries, you can't help but get swept up in the musicality of it all - the rise and fall of tones, the staccato bursts of consonants. with each new word unlocked, you find yourself picking up the rhythmic lilt that dances through everyday igbo conversations., before long, this wonderful language will start seeping into your soul, connecting you to the proud igbo culture that has endured and flourished for centuries in the lush, fertile landscapes of southeastern nigeria. getting started is just the beginning of an incredible journey., understanding the basics.

Before diving into complex grammar rules and vocabulary, it's essential to grasp the basics of Igbo language for beginners. Start by familiarizing yourself with common greetings, such as "Ndewo" (hello) and "Kedu" (how are you?). These simple phrases lay the foundation for meaningful interactions and pave the way for deeper language acquisition.

Unlocking the fundamentals of Igbo is akin to deciphering an intricate code etched into the very fabric of Nigerian life. At first glance, the tonal patterns and grammatical structures may seem bewildering - an enigmatic puzzle waiting to be unraveled. But fear not, for within this linguistic labyrinth lies an elegant simplicity, a framework that begins to reveal itself with each patient, mindful step.

The key consonants and vowels become familiar friends, their unique diacritics and combinations unveiling shades of meaning like finely-woven linguistic tapestries. From mastering the flow of subject-verb-object sequences to grasping the nuanced use of nasal vowels, the basics coalesce into a beautiful, coherent system.

One that ultimately connects you to the very heart and soul of Igbo expression - a bridge to a fascinating culture steeped in tradition yet dynamic in its living, breathing evolution.

Building Your Vocabulary

Expanding your vocabulary is key to mastering any language, and Igbo is no exception. Begin by learning everyday words and phrases related to topics you encounter regularly, such as family, food, and activities. Here's some examples:

Mastering Lyrical Pronunciation

The dance of Igbo speech begins with mastering its lyrical pronunciation - a delicate interplay of tones, nasality, and vowel harmony that caresses the ear. Like learning an intricate melody, you'll become attuned to the ebbs and flows of high, low, and down stepped pitches that imbue words with distinct shades of meaning.

Igbo pronunciation starts with the tones - the high (á), low (à), and down stepped (ā) pitches that distinguish words like ákwá (cry) from àkwà (bed) and ākwā (cloth). Nasal vowels like ọ́nụ (mouth) add richness. As you progress, challenge yourself to explore more specialized vocabulary areas, including professions, emotions, and abstract concepts.

Exploring Grammar Essentials

While mastering Igbo grammar may seem daunting at first, breaking it down into manageable components can ease the learning process. Start by familiarizing yourself with basic sentence structures, verb conjugations, and noun classes. As you gain confidence, gradually incorporate more complex grammatical concepts, such as tense, aspect, and mood.

The grammar then emerges as the rhythm section, with robust noun class and agreement systems underlying every well-constructed phrase. Grammar relies heavily on noun class prefixes marking number and agreement, like ùnó (house) and ínó (houses).

Discover the Fascinating Vocabulary

As you build your vocabulary repertoire, you'll discover rich descriptive words that paint vivid imagery, alongside terse pragmatic terms that succinctly convey deeper cultural concepts.

The vocabulary brims with vivid words like òkùkú (first light of dawn) and cultural concepts like ùgwúùgwù (respect).

The Tapestry of Conversational Phrases

Weaving it all together are conversational phrases - linguistic stitches binding the fluent discourse, enabling you to partake in the lively Igbo banter and storytelling traditions. From polite greetings to pithy proverbs and idiomatic expressions brimming with wisdom, you'll be equipped with the lexical tools to engage thoroughly in this multilayered tongue.

Start by familiarizing yourself with common greetings, such as "Ndewo" (hello) and "Kedu" (how are you?). Also, basic conversational phrases include káchāārịā (good morning), kédúūnó (welcome), ndēēzīgānū (please), and ēkènè (thank you). Igbo's lyrical tonality shines in greetings like Ọ̀kākāgōīrīēkèlé? (How was your night?) and proverbs like Agwọ̀kātịāàlānyāērīgēdīnwàỳàārā(Nocturnal wanderings expose the handsome to danger).

These simple phrases lay the foundation for meaningful interactions and pave the way for deeper language acquisition. With dedicated study of these elements, the linguistic mosaic reveals itself.

Immersing Yourself in the Language

To truly unlock the heart and soul of Igbo , one must immerse themselves fully in its rich rhythms and cultural currents. Go beyond the textbooks and lesson plans - let this melodic tongue wash over you in waves of sound and meaning.

Tune your ear to igbo music, movies, and radio programs, allowing the cadences and idioms to permeate your consciousness. engage with native speakers wherever you can, be it virtually or in person, and don't be afraid to fumble; mistakes are inevitable tributaries in the journey towards fluency..

Explore the culinary traditions, folktales, and oral histories held within Igbo's memoir-like expressions. Attend cultural celebrations and let the brilliant masquerades, dancing, and age-old ceremonial rites immerse you in the very essence of Igbo life.

Through full immersion in both its linguistic and cultural spheres, what once felt like a foreign tongue begins to resonate in perfect harmony - the symphony of a vibrant, soulful world you can soon call your own.

Overcoming Challenges

The path to Igbo fluency winds through a verdant linguistic landscape, replete with challenges that demand patience, persistence and an open mind. At times, the tonal melodies may seem discordant to the untrained ear, with rising and falling pitches conspiring to trip up even the most diligent student.

The robust noun class system, with its intricate web of prefixes and agreements, can feel like navigating a thick forest without a map. Even seemingly simple vocabulary can conceal deeper cultural concepts invisible to the outsider. Yet such tests of resilience are precisely what fortify the language learner's resolve.

By embracing the hurdles as opportunities for growth rather than obstacles, you begin to reorient your perspective. Those baffling tones become gateways to emotional nuance. The complex grammar, a code to unlock deeper cognitive pathways. The idiomatic phrases, keys to the compelling Igbo worldview.

Overcoming requires embracing a beginner's mindset - remaining humble, culturing curiosity, and deriving joy from the journey itself. For those who persist, an immensely rewarding world awaits on the other side. Remember to be patient with yourself, stay persistent in your studies, and celebrate your progress, no matter how small.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Q1: why should someone learn the igbo language.

A1 : Learning Igbo opens a door to the rich cultural heritage of southeastern Nigeria. It allows you to connect more deeply with Igbo art, music, literature, and traditions. As one of the major languages of Africa, Igbo also provides linguistic insights into the continent's diversity.

Q2: What are some of the biggest challenges in learning Igbo for beginners?

A2: The tonal nature of Igbo, with high, low, and down stepped pitches, can be difficult for those unfamiliar with tonal languages. The robust noun class system of prefixes also takes time to master. Additionally, many Igbo concepts don't directly translate to English.

Q3: How is Igbo pronunciation different from English?

A3: Igbo has nasal vowels and places more emphasis on tones that convey different meanings. The language also has distinct consonant sounds like the impressively rolled "r" that takes practice for English speakers.

Q4: How long does it typically take to become conversationally fluent in Igbo?

A4: There's no set timetable, as it depends on one's dedication, immersion, and regular practice. However, with focused daily study, solid conversational skills usually develop within 1-2 years for motivated beginners.

Q5: Can you provide an example of an Igbo proverb or idiomatic expression?

A5: One classic Igbo proverb is "Ǹkè àbùrú ési, àbùrú ò ̣whū" which translates to "What will be will be." An example idiom is "Ịrà òkukù kwā ọtọ" or "A bathing lizard avoids the depths" meaning to avoid unfamiliar territory.

Q6: What are some tips for maintaining motivation while learning Igbo?

A6: Set achievable goals, track your progress, and immerse yourself in the language through cultural activities, media consumption, and regular practice sessions.

Conclusion: Learning Igbo Language for Beginners

Congratulations on taking the first steps towards mastering Igbo language for beginners! As you progress along the winding path of Igbo language acquisition, revel in the realization that you are joining a deep, powerful tradition.

With each new word, grammar concept, and idiomatic phrase committed to memory, you are weaving yourself into the very fabric of a vibrant culture steeped in centuries of oral tradition. The musical ebbs and flows of Igbo's tonal patterns, once baffling, become a source of linguistic delight.

The sturdy noun class system provides an appreciable structure for precisely expressing relations and nuances. Even seemingly basic vocabulary blooms into beautiful metaphorical concepts celebrating Igbo values like respect, humility and community. What began as a journey into the unknown gradually reveals itself as a homecoming - a reunion with the poetic source coding of human expression itself.

By opening yourself fully to Igbo's winding tributaries of sound and meaning, you'll find they ultimately merge into a mighty river, sweeping you forward in its strong cultural currents towards the endless sea of understanding. By staying committed to your learning journey, you'll unlock a world of opportunities for personal growth and intercultural connection.

By: Rhythm Languages

Related posts.

Unlocking Afrikaans Awesomeness: Is Afrikaans Easy to Learn?

Unlocking the Rich Tapestry: I Want to Learn Twi Language

Unlock the Secrets: How to Learn Hausa Easily in Simple Steps

‘We spoke English to set ourselves apart’: how I rediscovered my mother tongue

While I was growing up in Nigeria, my parents deliberately never spoke their native Igbo language to us. But later it became an essential part of me. By Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani

W hen I was a child, my great-grandmother, whom we called Daa, came to live with my family in Umuahia in south-eastern Nigeria . My father had spent most of his infancy in her care, mostly during a period when his mother was preoccupied with her role as one of the founders of a local Assemblies of God church. As Daa grew older and weaker, he felt it was his turn to take care of her. After much persuasion, he finally convinced her to leave her humble dwellings in a village far from where we lived and come spend her last days in the comfort of our modern home.

Each time I watched her shuffle one foot in front of the other, her back bent almost double until her head nearly touched the top of her walking stick, it was hard to imagine my father’s descriptions of a Daa who was once one of the tallest and most stunning women around. The story went that the colonial-era arbitrator who presided over the dissolution of her first marriage found her so beautiful that he decided on the spot to take her as one of his wives. “How can you maltreat such a beautiful woman?” he was said to have asked the errant husband.

Daa’s favourite pastime turned out to be watching American wrestling matches on TV. She had lived almost an entire lifetime with no television; and yet no other entertainment that the channels had to offer caught her fancy. With her ashen legs stretched stiff in suspense, she stared agape, chuckled loudly and gasped audibly as Mighty Igor and his ilk beat each other up on the small screen. Daa also enjoyed telling stories. But, apart from popular words like “TV” and “rice”, she knew no English. Her one and only language was Igbo. This meant that her storytelling sessions often involved vivid gesticulations and multiple repetitions so that my siblings and I could understand what she was trying to say, or so we could say anything that she understood.

None of us children spoke Igbo, our local language. Unlike the majority of their contemporaries in our hometown, my parents had chosen to speak only English to their children. Guests in our home adjusted to the fact that we were an English-speaking household, with varying degrees of success. Our helps were also encouraged to speak English. Many arrived from their remote villages unable to utter a single word of the foreign tongue, but as the weeks rolled by, they soon began to string complete sentences together with less contortion of their faces. My parents also spoke to each other in English – never mind that they had grown up speaking Igbo with their families. On the rare occasion my father and mother spoke Igbo to each other, it was a clear sign that they were conducting a conversation in which the children were not supposed to participate.

Over the years, I endured people teasing my parents – usually behind their backs – for this decision, accusing them of desiring to turn their children into white people. I read how the notorious former Ugandan president Idi Amin, in the 70s, brazenly addressed the United Nations in his mother tongue. The Congolese despot Mobutu Sese Seko also showed allegiance to his local language by dumping his European names. More recently, the internationally acclaimed Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o , after a successful career writing in English, decided to switch almost entirely to writing in his native Gikuyu. Upholding one’s mother tongue over English appeared to be the ultimate demonstration of one’s love of people and country – a middle finger raised in the face of British colonialism.

L ee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister of Singapore, thought differently. When he replaced Chinese with English as the official medium of instruction in his country’s schools, activists accused him of trying to suppress culture. The media portrayed him as “the oppressor in a government of ‘pseudo foreigners who forget their ancestors’,” as he explained in his autobiography, From Third World to First. But he believed the future of his country’s children depended on their command of the language of the latest textbooks, which would undoubtedly be English.

“With English, no race would have an advantage,” he wrote. “English as our working language has … given us a competitive advantage because it is the international language of business and diplomacy, of science and technology. Without it, we would not have many of the world’s multinationals and over 200 of the world’s top banks in Singapore. Nor would our people have taken so readily to computers and the internet.” Within a few decades of independence from Britain in 1965, Singapore had risen from poverty and disorder to become an economic powerhouse. The country’s transformation under Lee’s guidance is often described as dramatic.

My parents shared Lee’s convictions. They hoped English would give their children an advantage. But, as potent as that reason might be, my father admitted to me that it was secondary. He had an even stronger motivation for preferring English: “We spoke it to set ourselves apart,” he said. “Those of us who were educated wanted to distinguish ourselves from those who had money but didn’t go to school.”

A perennial issue among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria is the battle between the mind and the purse; between certificate and cash. All over Nigeria, the Igbo are recognised for their entrepreneurial spirit and business acumen. From pre-colonial times to today, a majority of the country’s successful traders and transporters have been Igbo. Many of them began as apprentices and worked their way up, never bothering with school. The Igbo are also known for ostentatiousness and flamboyance – those with great wealth usually find it difficult to be silent about it. While the moguls flaunted their cash, the educated members of my parents’ generation flaunted their degrees, many from British and American schools. They might not have had the excess cash to fling at the masses during public functions or to acquire fleets of cars, but they could speak fluent English – an asset that was not available for purchase in stores.

I still remember strangers staring and smiling at us in wonder whenever my family talked among ourselves in public. Speaking English was just one way of showing off, especially when one lived, like my parents, in what was then a small, little-known town. Some of my parents’ contemporaries distinguished themselves by appending their academic qualifications to their names. Apart from academics and medical doctors, it was common to hear people describe themselves as Architect Peter or Engineer Paul or Pharmacist Okoro.

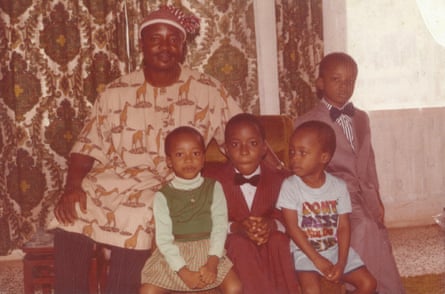

My father’s first degree was in economics, while my mother’s was in sociology. They met during the civil war between the government of Nigeria and the secessionist Igbo state of Biafra, and they spoke to each other in English throughout their three years of courtship, long before any of their children were born. “That was one of the things that attracted your daddy to me,” my mother said. “The way I spoke English fluently.” Back then, villagers made fun of my father for his choice of wife. They sneered that his determination to marry a university graduate had blinded him to the choice of a woman who was so skinny that she could surely never carry children successfully in her womb. Even if female university graduates were scarce, couldn’t he marry an uneducated woman and then send her to school?

T he simmering resentment between those with certificates and those with cash exploded to the surface in the 1990s, when the Nigerian economy plunged. Suddenly, it was not so difficult to find an educated wife willing to marry a man who could also take on the responsibility of her parents’ and siblings’ welfare. Whether or not he could speak English or read and write was immaterial. Around that same time, a significant number of uneducated but daring Igbo men found infamy and fortune by swindling westerners of millions through advance fee fraud, known locally as 419 scams. There were stories of learned men – professors and engineers and accountants – being openly scorned during community meetings. “Thank you for your speech, but how much money are you going to contribute?” they would be asked. “We are not here to eat English. Please, sit down and keep quiet.” There were also stories of 419 scammers sneering back at those who mocked their incorrect English and inability to pronounce the names of their luxury cars. “You knows the name, I owns the car,” they would say.

This longstanding battle between the mind and the wallet is probably why Igbo has suffered the most among Nigeria’s three main languages. The other two, Yoruba and Hausa, despite facing threats from English as well, seem not to be doing as badly. Yoruba is one of the languages on a list of suggestions for London police officers to learn, while the BBC World Service’s Hausa-language operation has a larger audience than any other. Meanwhile, Igbo is among the world’s endangered languages, and there is a rising cry, especially among Igbo intellectuals, for drastic action to preserve and promote our mother tongue.

Many of the children who admired people like my family grew up determined that their own children would also speak English. My parents spoke excellent English – my father certified as an accountant in Britain, while my mother acquired a PGCE in education and then taught in London primary schools. They quoted Shakespeare and used words like “effluvium” in everyday speech. Not many of the new generation of parents speaking English to their children have a command of the language themselves. Unfortunately, the public school system in Nigeria has continued to deteriorate, and few parents can afford the private education that could provide their children with good English lessons. There is now an alarming number of young Igbo people who are not fluent in their mother tongue or in English.

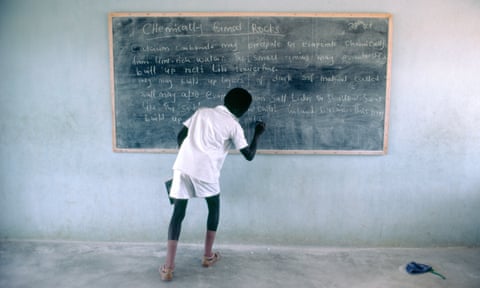

M y difficulty in communicating with Daa was not the only disadvantage of not being able to speak Igbo as a child. Each time it was my turn to stand and read to my primary school class from our recommended Igbo textbook, the pupils burst into grand giggles at my use of the wrong tones on the wrong syllables. Again and again, the teachers made me repeat. Each time, the class’s laughter was louder. My off-key pronunciations tickled them no end.

But while the other pupils were busy giggling, I went on to get the highest scores in Igbo tests. Always. Because the tests were written, they did not require the ability to pronounce words accurately. The rest of the class were relaxed in their understanding of the language, and so treated it casually. I considered Igbo foreign to me, and approached the subject studiously. I read Igbo literature and watched Igbo programmes on TV. My favourite was a series of comedy sketches called Mmadu O Bu Ewu, which featured a live goat dressed in human clothing. After studying Igbo from primary school through to the conclusion of secondary school, I was confident enough in my knowledge to register the language as one of my university entrance exam subjects.

Everyone thought me insane. Taking a major local language exam as a prerequisite for university admission was not child’s play. I was treading where expert speakers themselves feared to tread. Only two students in my entire school had chosen to take Igbo in these exams. But my Igbo score turned out to be good enough, when combined with my scores in the other two subjects I chose, to land me a place to study psychology at Nigeria’s prestigious University of Ibadan.

Eager to show off my hard-earned skill, whenever I come across publishers of African publications – especially those who make a big deal about propagating “African culture” – I ask if I can write something for them in Igbo. They always say no. Despite all the “promoting our culture” fanfare, they understand that local language submissions could limit the reach of their publications.

Indigenous works form an essential part of a people’s literary heritage, and there is definitely a place for them – but not, it seems, when it comes to world domination, or pushing beyond the boundaries of our nations and taking a place of influence on the world stage. Every single African writer who has gained some prominence on the global scene accomplished this on a platform provided by the west, to whom our local languages are of absolutely no significance.

Africans are no longer helplessly watching outsiders tell our own stories, as we did in past decades, but foreigners still retain the veto over the stories we tell. Publishers in Britain and America decide which of our narratives to present to the world. Then their judges decide which of us to award accolades – and subsequent fame. The literary audiences in our various countries usually watch and wait until the west crowns a new writer, then begin applauding that person. Local writers without some western seal of approval are automatically regarded by their compatriots as inferior.

The west is also where our books scoop the easiest sales. The west has better marketing and distribution structures, while those which exist in the majority of African countries are simply abysmal. Nigerians in Punxsutawney can have access to my novels if they so desire, and so can those in Pontypridd. But in my country, where online shopping is still an esoteric venture, my books are accessible to the public in only a handful of cities.

Over the past decade alone, a number of major literary prizes have been awarded to writers of African origin. Ngũgĩ has been rumoured as having been considered for the Nobel prize in literature. That would hardly have happened had he begun his career writing in Gikuyu. He would probably not even have been known beyond the peripheries of Kenya, where the prevalence of that local language begins and ends. As the Nigerian author Chinua Achebe noted in a 1964 essay: “Those of us who have inherited the English language may not be in a position to appreciate the value of the inheritance. Or we may go on resenting it because it came as part of a package deal which included many other items of doubtful value and the positive atrocity of racial arrogance and prejudice … But let us not in rejecting the evil throw out the good with it.”

Perhaps Ngũgĩ and some other African writers care little about westerners being able to read their works. It could be that Nobel prizes and sales figures mean absolutely nothing to them. Maybe they are quite content with a local audience – but the local audiences themselves may not be able to read the authors’ books written in Gikuyu or Igbo or Chi.

Africa currently has the world’s lowest literacy rates. Unesco reports that more than 1 in 3 adults in sub-Saharan Africa are unable to read and write, as are 47 million young people (ages 15-24). The region accounts for almost half of the 64 million primary school-aged children in the world who are not in school. Not even the English are born with the ability to read their language. They are taught – usually in schools.

I wonder how many literate Gikuyu speakers can read their language. I wonder how many have read Ngũgĩ’s work. My parents, who have spoken Igbo their entire lives, can hardly read and write their mother tongue fluently. They were never taught. At the time they went to school, the colonials, whom we detest so much, were probably still busy transcribing our own mother tongues for us – from ideograms to the more universal Roman letters – to enable us begin to read and write our own local languages.

D aa eventually got weary of modern life and sulked until my father allowed her to return to her village, where she eventually died peacefully in her sleep. But it was not until the 2000s that I finally understood her fascination with US wrestling, after a former colleague told me of how her aged grandmother, while visiting from her village and watching Jerry Springer for the first time, suddenly exclaimed in shock: “Ah! So white people fight?!”

All those years ago, Daa was probably equally intrigued to see white people punching each other on TV. Living in Umuahia, where the sight of a white person is still today so rare that it draws a crowd in the street, meant that the few Caucasians Daa had glimpsed in her lifetime were probably missionaries and colonial officers – most of whom were models of civilisation, poster boys of higher breeding. When she came to stay with my family, she must have been shocked by the uncharacteristic sight of white people acting so savagely on TV.

That said, having one language to dominate others must have reduced conflict. If, for example, we decided to dump English and use a mother tongue as the language of instruction in local schools, which of the at least 300 tongues in Nigeria or the 70 in Kenya or the 120 in Tanzania (and so on) would those countries use to teach their children? This would be more difficult than ever today, when many African societies are becoming urbanised, with different ethnic groups converging in the same locality. Which language should schools select and which should they abandon? How many fresh accusations of marginalisation would arise from this process?

Lee Kuan Yew pointed out in his book how a multitude of mother tongues could have been a major hindrance to Singapore’s national security. Without a unifying language, the country’s armed forces faced a huge risk: “We were saddled with a hideous collection of dialects and languages,” he wrote, “and faced the prospect of going into battle without understanding each other.”

In Africa’s case, it would not just have been going to battle without understanding each other, but going to battle because we do not understand each other. The many wars around Africa are usually fought along ethnic lines. The lack of a common language would have further accentuated our differences, giving opportunity for yet more conflict. Languages like English have made Africa a more peaceful and unified region than it might have been. The contemptible colonials at least gave us an easy means of communicating with one another, preventing a Tower of Babel situation on the continent.

I attended a school in Nigeria where speaking your mother tongue was banned for that very reason. Shortly after the Nigerian civil war, which was instigated by venomous tribal sentiments, my country’s government hatched the idea of special schools in every state. A quota system would ensure that as many ethnic groups as possible were represented in each of the “unity schools”. For the first time in Nigeria’s history, children from every region would have the opportunity to mix and to get to know one another beyond the fog of tribalism. We were taught to see ourselves as Nigerian, not Igbo or Hausa or Yoruba or whatever. Local languages were part of the curriculum, but speaking them beyond the classroom was a punishable offence.

It was not until university that I at last began to speak the language. In Ibadan, away from Igbo land and from the laughing voices, away from those who either did not allow me to speak Igbo or who did not believe I could speak it, I was finally free to open my mouth and express the words that had been bottled up inside my head for so many years – the words I had heard people in the market speak, the words I had read in books and heard on TV, the words my father had not permitted around the house.

Speaking Igbo in university was particularly essential if I was to socialise comfortably with the Igbo community there, as most of the “foreigners” in the Yoruba-dominated school considered it super-important to be seen talking our language in this strange land. “ Suo n’asusu anyi! Speak in our language!” they often admonished when I launched a conversation with them in English. “Don’t you hear the Yorubas speaking their own language?”

Thus, in a strange land far away from home, I finally became fluent in a language I had hardly uttered all my life. Today, few people can tell from my pronunciations that I grew up not speaking Igbo. “Your wit is even sharper in Igbo than in English,” my mother insists. Strangely, whenever I am in the presence of anyone who knew me as a child, when I was not permitted to speak Igbo, my eloquence in the local tongue often regresses. I stammer, falter, repeat myself. Perhaps my tongue is tied by the recollection of their mockery.

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread , or sign up to the long read weekly email here .

- The long read

Most viewed

University of Notre Dame

Fresh Writing

A publication of the University Writing Program

- Home ›

- Essays ›

Language and Excellence

By Joy Agwu

Published: July 31, 2021

3rd place McPartlin Award

I first met my paternal grandparents the week before my eighth-grade graduation. They live in Nigeria, and my family and I live in America. Over the first fourteen years of my life, time conflicts and visa troubles on both sides repeatedly deterred the opportunity for us to meet; then everything came together for them to attend this celebration of academic excellence. I was so ecstatic to finally get to know them in person.

From my first encounter with them, I quickly noticed that their English was very slow and deliberate when they spoke. As a freshly graduated middle schooler with a world of wisdom, I astutely assumed that it was because they were old. Later in their visit, when I overheard them speaking in quick discussion with each other, I realized that my assumption was wrong. Observing them, laughing and discussing in quick rapport, I soon learned that my grandparents were fast-paced, humorous, and witty people…or, at least, they seemed to be. I could not know for sure, because the platform for this beautiful, almost miraculous shift in expression was a language I did not understand: Igbo, the language of their home.

The Igbo tribe of Nigeria is one of the country’s three major tribes, boasting almost twenty-million people and accounting for 20% of the nation’s population (McKenna). The tribe bears a rich, wonderful culture and is full of unique traditions, customs, attire, and art. Through my father’s side of the family, I am Igbo. As such, I enjoy listening to Naija music, know how to prepare Jollof rice, and feel a sense of pride when I see an Igbo victory in the news. I have a general awareness of the culture, and for years, this was enough to convince myself, and other Americans, of my heritage. However, after meeting my grandparents and listening to them speak in Igbo, my confidence in that fact shifted. Despite technically being Igbo, I could not fully connect with grandparents because I did not know the language. Was this my relationship with the tribe — technically a member, but restricted in my ability to truly connect?

In one of the more candid, one-on-one discussions I had with my grandparents, my grandmother asked me why I did not know Igbo. I froze. She did not ask it confrontationally, or even with a hint of disappointment. Her question was instead solely rooted in curiosity—why did I not know the language of my family, the language in which I could freely speak to them?

I was struck speechless for a moment. Eventually, I opened my mouth and gave her the best answer I could muster:

I don’t know.

In the years since, however, I have come to realize a better answer. As an Igbo child of the diaspora, [1] it is not entirely unexpected for me to not know the language. In the years since my grandparents’ visit, I have gone through dozens of group chats, YouTube videos, and blog posts where others have shared similar experiences. Through these platforms, I have become increasingly aware that my situation is not unique. It almost seems as if not learning Igbo has become a tradition of its own for many children of the diaspora. As more and more Igbos move out of Nigeria, it is an unfortunately common occurrence that Igbo immigrants do not foster their language in their households. Many times, if the children do learn the language, it is not until adulthood and through their own determined pursuit. When asked why they do not know the mother tongue, many diaspora-born Igbos are quick to point the finger at their Igbo parent or parents, and this behavior is not discouraged within Igbo society and conversation on the topic.

When referring to the tribe’s attitude towards their language, most characterize the act as resentment. Many subscribe to the idea that, as Igbos have immigrated and built roots in other Western cultures, we also built resentment towards our own background. One research paper even claims that such negativity “has been established” and as a result, Igbos living in the diaspora “prefer their children speaking English to speaking Igbo” (Asonye). Authors typically produce the claim without evidence, and most accept it as an explanation of Igbo behavior within the diaspora. However, while this claim is not entirely unfounded, it is not wholly accurate. While there may be individuals fostering negativity towards the Igbo language, I believe it is the tribe’s nature that lies at the heart of this trend—particularly regarding our drive towards excellence. In order to achieve, Igbos must set priorities in line with their new homes in the diaspora. Unfortunately, the mother tongue does not always make the cut. With this understanding, our objective should not be to change the nature that prompts this trend, but to utilize it in a concerted effort to revive the Igbo language.

While I do not know the language, I realize that I am well-acquainted with the tribe’s nature of excellence. Growing up, I was not the strongest at school. If anything, I was an average student and struggled at times. However, the moments when I did well on an assignment are ingrained in my memory for two reasons: first, the feeling of achievement, and second, my father’s reaction. I have distinct memories of showing my father various tests, assignments, and report cards, and the interaction typically followed similar, if not the same lines:

Daddy, Daddy, look! I got an A!

Of course you did, princess. A is for Agwu, after all.

My dad would repeat some rendition of this axiom whenever I shared my best grades with him. Four little words— A is for Agwu —but the message there was clear: We are the best. We excel in all that we do.

As I look back, I can tell that this mindset accurately reflects his Igbo upbringing and the general culture fostered within the tribe. The message could also present some fuzziness, though. Does one excel because they are Igbo? Or is one Igbo because they excel ?

The general consensus is: if you are doing it right, you should not have to ask.

The Igbo standard of excellence is primarily represented in business and academic achievement. In the United States, Nigerians make up the most educated ethnic group, with 61.4% of their population bearing a bachelor’s degree or higher (Ogunwole, Battle and Cohen). Based on my own experience, with most of my paternal relatives boasting multiple degrees, I am sure that Igbos make up a considerable percentage of this number. The tribe values excellence, and such is their reputation. Within Nigeria, a well-known Igbo stereotype is that we are all businesspeople, industrious, and constantly on the lookout for advancement and success (Agwu; Ogunfowoke). While the image does have its negative connotations, I believe there is some truth to this statement. As a people, we are not in the habit of doing things halfway, and it shows. While we may not all venture into business—I, for one, have very little interest in the field—we are brought up with industrious, resilient spirits and are encouraged to achieve. Igbo immigrants branch out into the world, bearing a desire to create roots and excel in their new environment. This excellence not only requires adapting to the language of the land but mastering all of its avenues for success.

A common explanation Igbo immigrants provide for not teaching their children the Igbo language is because, as they transition from Nigeria to another country, they do not see it as a priority. Regardless of origin, in a new country, it is not uncommon for immigrant parents to prioritize creating firm roots over passing on a language not spoken in their new location (Kheirkhah). The Igbo diaspora community is no different in this regard. In fact, they direct even more time and emphasis to this step. In their efforts to build a solid foundation in the diaspora, parents may set aside teaching their children Igbo in favor of establishing roots in their new environment. However, as time goes by, the perfect circumstances to educate their children pass as well; then the children reach adulthood, and it feels too late. The pull of building a successful foreign life repeatedly triumphs over the desire to pass on the Igbo language, but this decision is not made in resentment towards the language. Rather, it is them adhering to another aspect of their Igbo identity.

The Igbo culture of excellence further explains why the “settling in” process can be so detrimental to passing on the Igbo tongue to their diaspora-born children. In their desire to excel in this new country, they want to set up their child for the same goal. A common concern amongst Igbo parents is how learning Igbo at home will affect their children’s ability to learn English at school. “[My parents] wanted me to speak good English and they didn’t want me to go through the same struggles that they went through,” one young man shared in a YouTube video, explaining why his parents did not teach him Igbo (Okwu ID). While being bilingual may offer benefits in the long run, there are difficulties associated with learning both English and a tribal language in childhood. In Maryland, my home state, if a child is identified as an English Learner, they are supposed to receive accommodations so they may still be able to follow in a classroom (“English Learners”). However, this is far more difficult with a tribal tongue, because translators are not as accessible. As this is not an ideal, or even guaranteed, circumstance, most Igbo parents find themselves deferring from it entirely. This is what happened in my own experience.

In an interview, my father described his decision to not teach me Igbo as providing the “best option” for me; he wanted me to thrive here, first, “and here, the language is English” (Agwu). By electing to not teach their youth their mother tongue, Igbo immigrants are not displaying resentment towards the language. Rather, they are recognizing the trends of the land, and equipping children with what they believe to be the best tools for success. While the intention here is noble, and evidently provides stellar results, it also has detrimental effects.

If you posed the question of what makes a person Igbo, language or excellence, Nigeria-born Igbos might boastingly answer with excellence , whereas their diaspora-born youth might be more inclined to answer with language . For the diaspora-born Igbos who do not know the mother tongue, there is often an inner struggle of identity. This is displayed by how often these youths express an intense desire to learn the mother tongue later on in their lives. Objectively, one could understand why familial aspirations eclipsed this area of education, but there is still a sense of identity missed. One young man shares that, as much as he appreciates his parent’s intention in not teaching him Igbo, “in hindsight, [he feels] like it’s a barrier” (Okwu ID). In this trend of choosing excellence over language, diaspora-born Igbos receive what has been deemed the more valuable aspect of our culture—but it is still only a portion of a whole. We may be excellent scholars, businesspeople, and working members of society, but we are still missing a piece of our identity. Without the language, diaspora Igbos are prevented from fully connecting with their heritage and other natives of the tribe. It feels as if there is a whole part of the culture that we cannot access, and the key to unlocking it was taken from us years ago. A culture is not solely defined by its means of expression, but the two are undoubtedly connected.

As more and more Igbos leave Nigeria for other countries, I implore them to cease leaving the Igbo language behind as well—if not for the cultural identity of their children, then for the sake of their tribe. In 2006, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization shared that the Igbo language was in danger of going extinct by the year 2050, if preventative action is not taken (Asonye). Decades of not passing down the Igbo language has finally shown its wear on the mother tongue, and now we must correct it. I urge the tribe to utilize its thirst for excellence and redirect some of that energy towards the revival of the Igbo language. We are a tribe that strives for success, and I strongly believe that this mindset can be applied to any challenge.

Migrational circumstances may never change, and the language of a new location may always pose as a more convenient tool for success. However, that does not mean we must continue to compromise one factor of our identity for another. It is time that Igbo immigrants stopped treating excellence and language as two competing cultural aspects, but rather as two equal parts of Igbo identity. As a child of the diaspora, I am grateful to my father for his intentions, but I now urge future Igbo immigrants to do better. Teach us the language of Igboland. While it may create a few challenges in our international upbringing, it will be invaluable for our Igbo identity. We do not excel because circumstances are always easy; we excel because we are an industrious, striving people.

We excel because we are Igbo. Because we are Igbo, we will save our language.

[1] In this case, anywhere outside of Nigeria or Igboland.

Works Cited

Agwu, James. Personal interview. 28 Oct. 2020.

Asonye, Emmanuel. “UNESCO Prediction of the Igbo Language Death: Facts and Fables.” Journal of the Linguistic Association of Nigeria , vol. 16, no. 1 & 2, 2013, pp. 91-98, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330854897_UNESCO_Prediction_of_the_Igbo_Language_Death_Facts_and_Fables .

“English Learners: English Language Proficiency Assessment.” Maryland State Department of Education , www.marylandpublicschools.org/programs/pages/english-learners/english-language-proficiency-assessment.aspx .

Kheirkhah, Mina. From Family Language Practices to Family Language Policies: Children as Socializing Agents . March 2016. Linköping University, PhD dissertation. ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317606264_From_family_language_practices_to_family_language_policies_Children_as_socializing_agents .

McKenna, Amy. “Igbo.” Encyclopædia Britannica , Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/Igbo .

Ogunfowoke, Adeniyi. “5 Igbo Stereotypes Every Nigerian Must Drop.” Medium , 10 Mar. 2016, medium.com/@Sleeksavvy/5-igbo-stereotypes-every-nigerian-must-drop-a1d78c59d3b4 .

Ogunwole, Stella U., Karen R. Battle, and Darryl T. Cohen. “Characteristics of Selected Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean Ancestry Groups.” The United States Census Bureau , 28 June 2017, www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2017/comm/cb17-108-graphic-subsaharan.html .

Okwu ID. “Episode 1—Is the Igbo Language Dying?” YouTube , 17 July 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=u92lFfDgVdo .

How do the Aristotelian appeals (logos, pathos, and ethos) interact in this essay? Look especially for places where two or three of the appeals appear in the same place—how do those overlaps impact the overall effect of the argument?

First-person narration is a crucial piece of this essay’s argument. What sort of ethos does the author craft for herself, and what specific authorial moves most successfully establish her credibility on her topic? How does the author’s positionality, especially in relationship to the Igbo community, qualify her to make her argument?

There is essentially no research that speaks directly to issues of Igbo language learning in the diaspora, and yet this essay is still firmly grounded in research. What strategies does the author use to incorporate other voices into her argument? At which points is the essay most successful in integrating research and narrative?

Joy Agwu is a student from Bowie, Maryland and resides in Pasquerilla West Hall. She is currently majoring in both English and Philosophy in the class of 2024. After graduation, she aspires to enroll in law school and practice in Washington D.C. In her essay, “Language and Excellence,” Joy focuses on the diaspora population of the Igbo tribe of Nigeria and their relationship with the Igbo language. Motivated by her own experiences as a diaspora-born Igbo, Joy explores this topic through the lens of cultural identity, weighing the merits of language versus excellence in considering oneself as Igbo. Joy would like to thank her Writing and Rhetoric professor, Laura MacGowan, for her support and instruction throughout the writing process. She would also like to thank her family for their constant love and encouragement, specifically her father for being an amazing and informative resource as she explored this topic.

Igbo Language Learning Online Community for Adult Beginners

- Writing in Igbo

Ihe M Chọrọ Ime Na Afọ a (What I Want To Do This Year)

This is part of an ongoing Practice Writing Igbo series where I am writing more in the Igbo language to improve my Igbo skills! I will be sharing some of my writing practice here in the blog to inspire you to write more Igbo. I include my mistakes because I want to show you that it’s okay to make mistakes and that you can actually learn from them overtime.

This month’s topic is talking about my goals for the new year:

(more…)

Na-Eme Ụlọ M Mma (Keeping My Home Beautiful)

This month’s topic is talking about my thoughts on having a nice home:

Ụwa a (This World)

This month’s topic is talking about my thoughts on this world/nature:

Nne Ọma (Good Mother)

This month’s topic is talking about my thoughts on being a mommy:

Ihe Nzuzo nri m (My food secrets)

This month’s topic is talking about my thoughts on certain kinds of food:

As Israel Ramps Up Rafah Attacks, Is Any Safe Place Left in Gaza?

- International Affairs

- is_single_v1 Syed Ali When news of a new disaster seems to roll in every day… it can feel like there’s little hope. But what if we had… another option? Not just to reverse course on climate change, but to set the course for a better future. Carol Cohn and Claire Duncanson think we do. GUESTS: Carol Cohn, University[...]

The End of the World as We Know It

The Little Book of Pentagon Words in the Pacific

What Lies Ahead for Rohingya in Myanmar?

Deep Dive: History’s Interpreters

In Beirut, a Homegrown Student Movement for Palestine

The Next Generation of Arms Controllers Needs Our Help

- Nuclear Weapons

The Solomon Islands’ Quest for Truth and Reconciliation

Cyprus Pushbacks Fail to Deter Refugee Boats from Lebanon

How the Climate Crisis Deepens Hardships for Rohingya Refugees

Cheap Fakes: The Global Trade in Counterfeit Drugs

- Social Justice

Student Gaza Solidarity Movement Draws on Long History of Divestment

Losing Our Language, Losing Ourselves

A young Nigerian reflects on estrangement from his mother tongue.

As I journeyed through my formative years in Nigeria, I found myself gradually drifting away from my mother tongue, Igbo, as English became my preferred language. This shift wasn’t entirely my fault; at home, my parents predominantly spoke English, leaving me disconnected from my cultural heritage.

There was a prevailing misguided belief that embracing the Igbo language could somehow diminish my intellect. Fluency in English had erroneously been equated with higher intelligence, rather than as a mere tool for communication. Even when my elderly uncles from my father’s side visited us after church on Sundays, marveling at my mother’s pot of rice simmering on the stove, they consciously refrained from speaking Igbo to me and my siblings. I often wondered why they didn’t communicate with us in the language they conversed in amongst themselves. They always responded, “You’ll learn it when you grow up. But for now, focus on your studies.” It felt as though speaking Igbo as a child was directly linked to poor academic performance.

Today, I find myself yearning to fully embrace the cultural identity that resonates within me, yet feels foreign on my tongue. Although I proudly identify as Igbo, I struggle to express myself fluently in the language. I can manage basic greetings like “kedu?” (how are you?) and ask simple questions about someone’s name. However, my knowledge of the Igbo calendar, market days, customs, and beliefs that define my people remains limited.

Language serves as the crucial bond that unites us, and without it, I feel disconnected from my tribe. There are moments when I feel like a person without a distinct identity, adrift without roots or purpose.

I am not alone in this struggle of identifying as Igbo while grappling with the language barrier. Growing up, encountering peers who could fluently speak our language felt akin to witnessing a miracle. In my secondary school, language classes were organized according to different tribes: Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo. The teachers would instruct in their respective native languages. However, it was disheartening to witness our Igbo teacher resort to delivering lectures in English due to the language barriers many of us faced.

We would gaze in awe as our teacher translated Igbo into sentences we could understand. However, it pained her deeply that during Igbo literature classes, she had no choice but to translate entire Igbo novels into English. This disparity was not observed in the Hausa or Yoruba language classes. While Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba are recognized as the three major languages in Nigeria, it appears that one of them is gradually losing its significance.

The Igbo language is currently facing a critical crisis, despite recognition as one of Nigeria’s major languages. In 2012, UNESCO issued a warning, stating that the Igbo language is at risk of fading away and may even face extinction by 2025 if the trend continues.

Historical Context

Different regions in Nigeria are dominated by specific ethnic groups. The northern half is influenced by the Hausas and Fulanis, while the southern half is predominantly Yoruba. The Igbo community, situated in the southeastern part of the country, has a rich cultural heritage but holds a secondary position in Nigeria’s power dynamic, despite having a population of approximately 40 million individuals , a significant portion of the country’s total population, which exceeds 200 million.

A clear example of this marginalization is seen in Nigerian politics. The presidency rotates between candidates from the northern and southern regions, and in the history of the Republic, only one Igbo individual has held the position, and for just six months. This highlights a systemic inequality that affects the Igbo community’s representation and influence.

To understand Nigeria’s social fabric, we must consider its colonial past. During the 1884 Berlin Conference, colonial powers drew borders across Africa, including Nigeria. As a former British colony, Nigeria not only inherited economic influences but also witnessed the decline of local languages due to the imposition of English.

Under colonial rule, English became the dominant language in education, governance, and commerce. It was associated with prestige and opportunity, creating a hierarchy that disadvantaged Indigenous languages. Local languages were seen as inferior by the colonial invaders, leading to reduced fluency and a loss of linguistic diversity as communities began to settle in urban areas.

The impact of English on local languages in Nigeria has been significant, even in the postcolonial era. The language has had far-reaching effects on cultural heritage, knowledge transmission, and community identity. English continues to hold the status of Nigeria’s official language, and proficiency in English is sometimes seen as an indicator of intelligence. It is widely used in both public and private settings and remains the sole official language of the country.

Over time, the Igbos have increasingly embraced Western values and religion. They eagerly pursued education in Europe and replaced their traditional deities with the concept of an all-powerful God introduced by white missionaries. While some individuals genuinely adopted these changes based on personal conviction, there may have also been an element of self-deprecation involved. It is common to see Igbos adopting English names as their first names, often considering them more fashionable or appealing. For instance, personally, I have introduced myself as Promise instead of my tribal name, Chisom, because the English name appears more glamorous.

Additionally, as people began to settle in culturally diverse cities, English, along with Nigerian Pidgin, naturally emerged as the dominant language of communication. English encountered various Indigenous languages and competed with them for prevalence. However, unlike the Hausa and Yoruba communities, which actively made intentional efforts to preserve their languages through arts and speaking them at home, the Igbo community embraced English and allowed it to replace their own language. In fact, within Igbo households, a high level of proficiency in English is often revered, and individuals who exhibit exceptional command of the language are considered to be of high status.

Even now, Igbos are widely recognized as an entrepreneurial group, who often travel extensively and integrate into mixed urbanized cities. The entrepreneurial spirit of the Igbos drives them to explore distant lands in pursuit of better livelihoods. In fact, there is a popular saying in Nigeria that if you visit any village in the country and do not find an Igbo person, it may not be a desirable area. Even outside Nigeria, the Igbo diaspora wields significant influence. However, in the process of migration and assimilation, many Igbos have gradually replaced their native tongue with the accepted language of their host communities, often remaining disconnected from their hometowns for extended periods of time.

Biafran War and Igbo-Phobia

According to Amarachi Attamah, the Executive Director of Nwadioramma Concept and founder of OJA Cultural Development Initiative , the suppression of Igbo identity began as a survival mechanism following the Nigerian civil war, commonly known as the Biafran war.

The civil war was sparked by a series of pogroms and violence targeting the Igbo people in various parts of Nigeria. In 1967, the Republic of Biafra, a region predominantly inhabited by Igbos in southeastern Nigeria, declared its secession from Nigeria, leading to a prolonged conflict. After three years, the Nigerian military ultimately emerged victorious, resulting in the reunification of Biafra with Nigeria.

Attamah highlighted the limited options available to the Igbos in the aftermath of the war, as the extensive bombing had devastated the southeast region. To seek better opportunities, many Igbos were forced to migrate to other parts of Nigeria. Attamah specifically recalled how, after the war, the Nigerian government seized bank accounts belonging to Biafrans and implemented a resolution by a Nigerian panel that granted 20 pounds to any Igbo individual.

“Concealing their identities became necessary for the Igbos to avoid discrimination while striving to secure their daily sustenance. It is crucial to acknowledge that this discrimination was state-sponsored, as every Igbo person, regardless of their pre-war bank account balance, was only entitled to a mere 20 pounds,” Attamah said.

Internal Hostility

Sometimes, when my generation attempts to speak, and we make mistakes, fluent Igbo speakers don’t correct us but instead criticize us before we can finish. I remember a shop owner once said to me, “So you can’t speak Igbo? A big boy like you! What a shame!” when he spoke Igbo to me and I couldn’t reply. His words felt insulting, and I wished I could take away the Igbo he claimed to possess by pulling out his tongue. He could have approached the situation with more kindness.

My friend Uchenna Emelife had a similar experience when a man became furious because he couldn’t speak Igbo. “He came to visit my dad. When he saw me, he asked me some questions in Igbo. I tried to speak, but the words just wouldn’t come out. Before I could even finish attempting, he became furious, wondering why, at my age, I couldn’t speak my language. I was extremely angry. This is not the right way to encourage people to take an interest in speaking Igbo,” Emelife said.

The experience of Adaobi Nnadozie, a nurse I know, also lingers in my memory. Last year, she tragically lost her father, compelling her to return to the southeast from the northern part of the country for his burial rites. As the eldest daughter, she was expected to perform certain traditional customs, including singing and dancing in Igbo to mourn her father. However, her limited proficiency in the language prevented her from doing so, leading to frustration among the village elders.

“I faced insults for my inability to sing in Igbo. It was a dehumanizing experience, but I refused to let it affect me,” she shared.

This kind of hostility toward young people is giving rise to a generation of Igbos who fail to appreciate their language. I once had a heated debate on Facebook with a lady who stated that, despite being Igbo, she saw no need to learn the language since she resided in Lagos where English and Yoruba were widely spoken. She boldly wrote, “As long as Igbo doesn’t provide for my basic needs, I don’t care about learning it.” Those words struck me deeply, and I couldn’t help but feel a sense of shame on her behalf. I began to wonder why a people known for their large population are slowly relinquishing a language that once united them.

But Emmanuel Areke, a civil servant, believes that those who are hostile are only so to preserve the language. “They may be ignorant of the fact that they needed to only encourage those who can’t speak the language, but I believe that they’re just pained about the fact that people are now unable to speak the language of their ancestors,” he said.

The reluctance to prioritize the Igbo language may stem from the perception of its inferiority compared to English. Regrettably, some parents who hold this misguided belief intentionally withhold Igbo education from their children. However, Njideka Okafor, an Igbo radio presenter and an international Igbo interpreter based in Lagos, strongly disagrees, asserting that speaking Igbo does not hinder a child’s global outlook.

“They [parents] seem to overlook a crucial point: a child is capable of learning multiple languages simultaneously. While they teach their child English, they can also impart Igbo language skills. It is true that the child’s English pronunciation may be influenced by their mother tongue. Nevertheless, it becomes increasingly challenging for a child to acquire their mother tongue as they grow older,” she elaborated.

“I have witnessed instances where Igbo parents deliberately discourage their children from speaking Igbo. They hold the belief that Westernizing everything is beneficial, but in reality, it is not. Some Igbos, due to a lack of proper training in speaking Igbo, now perceive the language as outdated and lacking uniqueness. Those who claim to speak it often resort to speaking nothing but pidgin,” expressed Oby Ezeilo, an Igbo editor and staff member at Wikipedia.

How To Revive the Igbo Language

What actions can be taken to prevent the extinction of the Igbo language? It is crucial to recognize that the Igbo language encompasses more than mere words, many of which have been diluted and transformed into pidgin. Language serves as a gateway to a people’s culture, traditions, and beliefs. When one’s language is taken away, they become detached from the essence of their tribe.

A significant portion of efforts to revive the Igbo language comes from Igbos residing in foreign countries. These communities have organized festivals , offered Igbo language lessons on platforms like YouTube , and even assumed teaching positions in universities . Even prestigious institutions like Oxford University have recently appointed their first-ever Igbo lecturer to teach the language. However, such initiatives appear to be lacking within our own homeland.

These initiatives are part of efforts aimed at preserving endangered languages that are at risk of disappearing worldwide. UNESCO keeps a World Atlas of Languages that documents the health and endangerment of languages worldwide, and recently countries like Germany and Britain have made significant efforts to prevent the extinction of endangered regional languages. However, it is unfortunate to observe that the Igbo language, unlike other Nigerian languages that are still actively spoken, is on the verge of extinction.

The realization that I may never be able to express my thoughts in the language of my ancestors fills me with profound sadness . The prospect of reciting beautifully crafted Igbo poems, dancing to captivating moonlight Igbo songs, or reading bedtime stories in Igbo to my future children seems unattainable. Although I have contemplated hiring a teacher who understands Igbo to tutor them in the language, it troubles me to think about how Igbos have forsaken such a magnificent language in the pursuit of assimilation. Why can’t we simply embrace our roots and appreciate what we have?

I envy my friend Faith Arinze, whose parents, before their passing, ensured the transmission of the Igbo language and heritage to her and her siblings. She is one of the few young Igbos I know who can speak the language fairly well, despite being born in the northern city of Kaduna, far from the southeastern region where the Igbos originated. Faith shared that growing up, it was challenging for her to find peers with whom she could converse in Igbo, but that did not discourage her from preserving her language. That is how to keep a dying language alive.

The most effective way to preserve the language is to speak it. Embrace it and let it be the seasoning that flavors our homes. I would have said “screw UNESCO and their damning predictions” if they weren’t right. But screw me. If I knew how to express myself in Igbo, I would have written this piece in my language.

Promise Eze

Promise Eze is a young Nigerian journalist passionate about using journalism to improve public discourse and catalyze development.

You made it to the bottom of the page! That means you must like what we do. In that case, can we ask for your help? Inkstick is changing the face of foreign policy, but we can’t do it without you. If our content is something that you’ve come to rely on, please make a tax-deductible donation today. Even $5 or $10 a month makes a huge difference. Together, we can tell the stories that need to be told.

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

- {{ index + 1 }} {{ track.track_title }} {{ track.track_artist }} {{ track.album_title }} {{ track.length }}

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- 3rd Party Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- World Languages

- Learning Languages

How to Learn Igbo Language

Last Updated: March 29, 2023 Fact Checked

Tone Distinctions and Patterns

Grammatical structure.

This article was co-authored by Tian Zhou and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Tian Zhou is a Language Specialist and the Founder of Sishu Mandarin, a Chinese Language School in the New York metropolitan area. Tian holds a Bachelor's Degree in Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL) from Sun Yat-sen University and a Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) from New York University. Tian also holds a certification in Foreign Language (&ESL) - Mandarin (7-12) from New York State and certifications in Test for English Majors and Putonghua Proficiency Test from The Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. He is the host of MandarinPod, an advanced Chinese language learning podcast. There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 104,071 times.

Around 18 million people living in Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea speak Igbo. There are many dialects of the language, some so distinct that two people speaking different dialects of Igbo wouldn't be able to understand each other. Igbo tones are very different from those used in English and other European languages. If you want to learn Igbo, start by practicing tones, then learn basic grammar and sentence structure. Once this foundation is in place, you can start expanding your vocabulary with common Igbo words and phrases. [1] X Research source

- In French, for example, an accent mark would indicate that you pronounce the letter differently. In Spanish, an accent mark indicates which syllable has emphasis. However, in Igbo, the tone is separate from the pronunciation of the letter itself.

- Many letters in the Igbo alphabet sound the same in Igbo as they do in English. You can download a free alphabet chart at https://www.omniglot.com/writing/igbo.htm .

- The tone is high or low relative to the other tones around it. For example, "kedu" is a word that means "what" or "how," and is also used to say "hello." Pronounce it keh-duh . For the first syllable, use a high tone with your tongue to the roof of your mouth. The second syllable is a low tone, with your tongue flat. Practice it with the first syllable low and the second high just to see how the vowel sound changes with the different tone.

- For example, ákwá (high-high) means "weeping," ákwà (high-low) means "cloth," àkwá (low-high) means "egg," and àkwà (low-low) means "bridge."

- The U.S. State Department's Foreign Language Institute uses a basic Igbo course that includes tone drills. You can download them for free from the Live Lingua Project at https://www.livelingua.com/course/fsi/Igbo_-_Basic_Course .

- If possible, check the dialects being used. Make sure you're staying consistent within the same dialect. For example, Onitsha and Owerri are the two main Igbo dialect zones. While these dialects have many words in common, even they have some differences. [6] X Research source

- Igbo written language is phonetic, so for the most part you will be okay if you learn the pronunciation of letters and write a word as it sounds.

- If vowels have either a dot under the letter or an umlaut above, this indicates a different pronunciation of that letter. New Standard Orthography uses an umlaut, but you may see previous versions in writing. [8] X Research source

- For example, bi means "live." If you want to say "I live," it would be ebi m. For first person singular, the letter "m" follows the verb stem.

- Separable pronouns can be used as a subject, direct or indirect object, or to show possession. For example, the Igbo word anyï can be used to mean "we," "us," or "our." The word itself does not change regardless of how it's used.

- For example: ebi m (I live).

- You don't have to harmonize the vowels if you're using separable pronouns. Simply use the verb stem. For example: anyï bi (we live).

- The suffix -tara or -tere is added to a verb stem to indicate an action occurred in the past. For example: ö zütara anü (he bought meat).

- Choose the suffix form to harmonize vowels, not for gender or any other reason.

- For example: ülö ise means "five houses." The word ülö means "house" while ise means "five."

- If you find someone who is trying to learn English, you might be able to work out an exchange in which both of you help each other practice.

- Helping a native speaker learn English will also help you understand the grammatical structure of Igbo. They may make mistakes because some aspect of English grammar is absent from Igbo grammar. For example, they might say "five house" instead of "five houses," because in Igbo the noun form doesn't change when pluralized.

- For example, "congratulations" in Igbo is kongratuleshön .

- Start with the basic greeting, "hello": kedü . Other common phrases said in greeting are built from this word. For example, "How are you?" is "Kedü ka ö dï?" To ask a person's name, you would say "Kedu aha gï?"

- Columbia University has a collection of Igbo language materials available at http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00fwp/igbo_index.html .

- The rhythm of music and the repetitiveness of lyrics makes music an easy way to learn any language. Additionally, you can have music on in the background while you're doing other things.

- Identify artists you enjoy, then search for songs and videos on sites such as YouTube.

Community Q&A

- The Live Lingua Project has the entire basic Igbo course used in the Foreign Services Institute of the U.S. State Department available for free. Go to https://www.livelingua.com/course/fsi/Igbo_-_Basic_Course to download the PDF and listen to the audio. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 2

- Spend 30-45 minutes learning the language every day. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 0

- Make flashcards of 20-50 of the most important or common words and work on memorizing those first. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.omniglot.com/writing/igbo.htm

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m35l59tMwk8

- ↑ https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/myl/IRCS_Prosody1992/LibermanEtAl_IRCS_Prosody1992.pdf

- ↑ https://www.livelingua.com/course/fsi/Igbo_-_Basic_Course

- ↑ https://library.bu.edu/igbo

- ↑ https://www.igbovillagesquare.com/2019/11/igbo-spelling-rules.html

- ↑ https://www.igboguide.org/HT-igbogrammar.htm

- ↑ http://learn101.org/igbo_phrases.php

- ↑ https://www.omniglot.com/language/phrases/igbo.php

- ↑ http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00fwp/igbo_index.html

- ↑ https://www.musicinafrica.net/magazine/best-2017-ogene-how-igbo-genre-broke-mainstream-nigerian-music

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Victoria Effiong

Feb 14, 2021

Did this article help you?

Sunday Samuel

Oct 21, 2022

Jonathan Braxz

Jun 19, 2021

Helen Adedoyin

May 30, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

The Igbo Culture

This essay about the Igbo tribe in southeastern Nigeria explores their significant cultural, social, and historical aspects. The Igbo are known for their democratic governance system, which operates without kings but through councils of elders and other recognized groups. Spirituality is deeply ingrained in their life, with a belief system centered around the supreme deity Chukwu, other lesser gods, and ancestor worship. Artistic expression is also crucial, particularly in their use of masks and the construction of Mbari houses for religious purposes. The essay further discusses the profound impacts of colonialism, which introduced Christianity, altered traditional practices, and reshaped the socio-economic and political landscapes of the Igbo. Despite these changes, the Igbo have retained a strong cultural identity and continue to influence broader Nigerian society.

How it works