- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Social Work

- About the British Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Social Worker Interventions in Situations of Domestic Violence: What We Can Learn from Survivors' Personal Narratives?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

June Keeling, Katherine van Wormer, Social Worker Interventions in Situations of Domestic Violence: What We Can Learn from Survivors' Personal Narratives?, The British Journal of Social Work , Volume 42, Issue 7, October 2012, Pages 1354–1370, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr137

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Social workers are an integral provider in the statutory support offered to women experiencing domestic violence. This paper uses information obtained from women's personal narratives to examine this social worker–client relationship in situations of domestic violence. Embracing a feminist standpoint epistemology and focusing on the women's experiences, it is evident that many of the women expressed dissatisfaction with the way they were treated by social workers. Threats to remove the children from the home and victim blaming were among the tactics described. The parallel between such reported forms of coercion employed by social workers and those used by the abuser are striking. The findings suggest a lack of a favourable climate to ensure the safety of the woman and her family through the provision of family-centred care and a need to build more effective and supportive relationships with women experiencing domestic violence. Implications for social work practice are also discussed.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-263X

- Print ISSN 0045-3102

- Copyright © 2024 British Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women

- Mina Shayestefar 1 ,

- Mohadese Saffari 1 ,

- Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh 2 ,

- Monir Nobahar 3 , 4 ,

- Majid Mirmohammadkhani 4 ,

- Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh 5 &

- Zahra Khosravi 6

BMC Women's Health volume 23 , Article number: 322 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

8429 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication. Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan.

This study was conducted as mixed research (cross-sectional descriptive and phenomenological qualitative methods) to investigate domestic violence against women, and some related factors (quantitative) and experiences of such violence (qualitative) simultaneously in Semnan. In quantitative study, cluster sampling was conducted based on the areas covered by health centers from married women living in Semnan since March 2021 to March 2022 using Domestic Violence Questionnaire. Then, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics. In qualitative study by phenomenological approach and purposive sampling until data saturation, 9 women were selected who had referred to the counseling units of Semnan health centers due to domestic violence, since March 2021 to March 2022 and in-depth and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The conducted interviews were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7-step method.

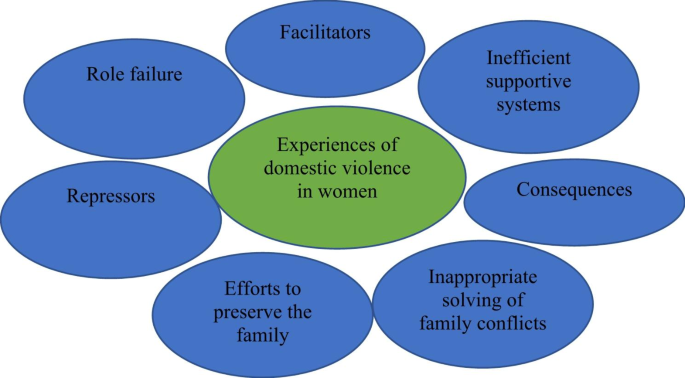

In qualitative study, seven themes were found including “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems”. In quantitative study, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage had a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of the number of children had a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). Also, increasing the level of female education and income both independently showed a significant relationship with increasing the score of violence.

Conclusions

Some of the variables of violence against women are known and the need for prevention and plans to take action before their occurrence is well felt. Also, supportive mechanisms with objective and taboo-breaking results should be implemented to minimize harm to women, and their children and families seriously.

Peer Review reports

Violence against women by husbands (physical, sexual and psychological violence) is one of the basic problems of public health and violation of women’s human rights. It is estimated that 35% of women and almost one out of every three women aged 15–49 experience physical or sexual violence by their spouse or non-spouse sexual violence in their lifetime [ 1 ]. This is a nationwide public health issue, and nearly every healthcare worker will encounter a patient who has suffered from some type of domestic or family violence. Unfortunately, different forms of family violence are often interconnected. The “cycle of abuse” frequently persists from children who witness it to their adult relationships, and ultimately to the care of the elderly [ 2 ]. This violence includes a range of physical, sexual and psychological actions, control, threats, aggression, abuse, and rape [ 3 ].

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent, and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication [ 3 ]. In the United States of America, more than one in three women (35.6%) experience rape, physical violence, and intimate partner violence (IPV) during their lifetime. Compared to men, women are nearly twice as likely (13.8% vs. 24.3%) to experience severe physical violence such as choking, burns, and threats with knives or guns [ 4 ]. The higher prevalence of violence against women can be due to the situational deprivation of women in patriarchal societies [ 5 ]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran reported 22.9%. The maximum of prevalence estimated in Tehran and Zahedan, respectively [ 6 ]. Currently, Iran has high levels of violence against women, and the provinces with the highest rates of unemployment and poverty also have the highest levels of violence against women [ 7 ].

Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society [ 8 ]. Violence against women leads to physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, including threats, coercion and arbitrary deprivation of their freedom in public and private life. Also, such violence is associated with harmful effects on women’s sexual reproductive health, including sexually transmitted infection such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), abortion, unsafe childbirth, and risky sexual behaviors [ 9 ]. There are high levels of psychological, sexual and physical domestic abuse among pregnant women [ 10 ]. Also, women with postpartum depression are significantly more likely to experience domestic violence during pregnancy [ 11 ].

Prompt attention to women’s health and rights at all levels is necessary, which reduces this problem and its risk factors [ 12 ]. Because women prefer to remain silent about domestic violence and there is a need to introduce immediate prevention programs to end domestic violence [ 13 ]. violence against women, which is an important public health problem, and concerns about human rights require careful study and the application of appropriate policies [ 14 ]. Also, the efforts to change the circumstances in which women face domestic violence remain significantly insufficient [ 15 ]. Given that few clear studies on violence against women and at the same time interviews with these people regarding their life experiences are available, the authors attempted to planning this research aims to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan with the research question of “What is the prevalence of domestic violence against women in Semnan, and what are their experiences of such violence?”, so that their results can be used in part of the future planning in the health system of the society.

This study is a combination of cross-sectional and phenomenology studies in order to investigate the amount of domestic violence against women and some related factors (quantitative) and their experience of this violence (qualitative) simultaneously in the Semnan city. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethic code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182. The researcher introduced herself to the research participants, explained the purpose of the study, and then obtained informed written consent. It was assured to the research units that the collected information will be anonymous and kept confidential. The participants were informed that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, so they can withdraw from the study at any time with confidence. The participants were notified that more than one interview session may be necessary. To increase the trustworthiness of the study, Guba and Lincoln’s criteria for rigor, including credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [ 16 ], were applied throughout the research process. The COREQ checklist was used to assess the present study quality. The researchers used observational notes for reflexivity and it preserved in all phases of this qualitative research process.

Qualitative method

Based on the phenomenological approach and with the purposeful sampling method, nine women who had referred to the counseling units of healthcare centers in Semnan city due to domestic violence in February 2021 to March 2022 were participated in the present study. The inclusion criteria for the study included marriage, a history of visiting a health center consultant due to domestic violence, and consent to participate in the study and unwillingness to participate in the study was the exclusion criteria. Each participant invited to the study by a telephone conversation about study aims and researcher information. The interviews place selected through agreement of the participant and the researcher and a place with the least environmental disturbance. Before starting each interview, the informed consent and all of the ethical considerations, including the purpose of the research, voluntary participation, confidentiality of the information were completely explained and they were asked to sign the written consent form. The participants were interviewed by depth, semi-structured and face-to-face interviews based on the main research question. Interviews were conducted by a female health services researcher with a background in nursing (M.Sh.). Data collection was continued until the data saturation and no new data appeared. Only the participants and the researcher were present during the interviews. All interviews were recorded by a MP3 Player by permission of the participants before starting. Interviews were not repeated. No additional field notes were taken during or after the interview.

The age range of the participants was from 38 to 55 years and their average age was 40 years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in table below (Table 1 ).

Five interviews in the courtyards of healthcare centers, 2 interviews in the park, and 2 interviews at the participants’ homes were conducted. The duration of the interviews varied from 45 min to one hour. The main research question was “What is your experience about domestic violence?“. According to the research progress some other questions were asked in line with the main question of the research.

The conducted interviews were analyzed by using the 7 steps Colizzi’s method [ 17 ]. In order to empathize with the participants, each interview was read several times and transcribed. Then two researchers (M.Sh. and M.N.) extracted the phrases that were directly related to the phenomenon of domestic violence against women independently and distinguished from other sentences by underlining them. Then these codes were organized into thematic clusters and the formulated concepts were sorted into specific thematic categories.

In the final stage, in order to make the data reliable, the researcher again referred to 2 participants and checked their agreement with their perceptions of the content. Also, possible important contents were discussed and clarified, and in this way, agreement and approval of the samples was obtained.

Quantitative method

The cross-sectional study was implemented from February 2021 to March 2022 with cluster sampling of married women in areas of 3 healthcare centers in Semnan city. Those participants who were married and agreed with the written and verbal informed consent about the ethical considerations were included to the study. The questionnaire was completed by the participants in paper and online form.

The instrument was the standard questionnaire of domestic violence against women by Mohseni Tabrizi et al. [ 18 ]. In the questionnaire, questions 1–10, 11–36, 37–65 and 66–71 related to sociodemographic information, types of spousal abuse (psychological, economical, physical and sexual violence), patriarchal beliefs and traditions and family upbringing and learning violence, respectively. In total, this questionnaire has 71 items.

The scoring of the questionnaire has two parts and the answers to them are based on the Likert scale. Questions 11–36 and 66–71 are answered with always [ 4 ] to never (0) and questions 37–65 with completely agree [ 4 ] to completely disagree (0). The minimum and maximum score is 0 and 300, respectively. The total score of 0–60, 61–120 and higher than 121 demonstrates low, moderate and severe domestic violence against women, respectively [ 18 ].

In the study by Tabrizi et al., to evaluate the validity and reliability of this questionnaire, researchers tried to measure the face validity of the scale by the previous research. Those items and questions which their accuracies were confirmed by social science professors and experts used in the research, finally. The total Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.183, which confirmed that the reliability of the questions and items of the questionnaire is sufficient [ 18 ].

Descriptive data were reported using mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentage. Then, to measure the relationship between the variables, χ2 and Pearson tests also variance and regression analysis were performed. All analysis were performed by using SPSS version 26 and the significance level was considered as p < 0.05.

Qualitative results

According to the third step of Colaizzi’s 7-step method, the researcher attempted to conceptualize and formulate the extracted meanings. In this step, the primary codes were extracted from the important sentences related to the phenomenon of violence against women, which were marked by underlining, which are shown below as examples of this stage and coding.

The primary code of indifference to the father’s role was extracted from the following sentences. This is indifference in the role of the father in front of the children.

“Some time ago, I told him that our daughter is single-sided deaf. She has a doctor’s appointment; I have to take her to the doctor. He said that I don’t have money to give you. He doesn’t force himself to make money anyway” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“He didn’t value his own children. He didn’t think about his older children” (p 4, 54 yrs).

The primary code extracted here included lack of commitment in the role of head of the household. This is irresponsibility towards the family and meeting their needs.

“My husband was fired from work after 10 years due to disorder and laziness. Since then, he has not found a suitable job. Every time he went to work, he was fired after a month because of laziness” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“In the evening, he used to get dressed and go out, and he didn’t come back until late. Some nights, I was so afraid of being alone that I put a knife under my pillow when I slept” (p 2, 33 yrs).

A total of 246 primary codes were extracted from the interviews in the third step. In the fourth step, the researchers put the formulated concepts (primary codes) into 85 specific sub-categories.

Twenty-three categories were extracted from 85 sub-categories. In the sixth step, the concepts of the fifth step were integrated and formed seven themes (Table 2 ).

These themes included “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems” (Fig. 1 ).

Themes of domestic violence against women

Some of the statements of the participants on the theme of “ Facilitators” are listed below:

Husband’s criminal record

“He got his death sentence for drugs. But, at last it was ended for 10 years” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Inappropriate age for marriage

“At the age of thirteen, I married a boy who was 25 years old” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My first husband obeyed her parents. I was 12–13 years old” (p 3, 32 yrs).

“I couldn’t do anything. I was humiliated” (p 1, 38 yrs).

“A bridegroom came. The mother was against. She said, I am young. My older sister is not married yet, but I was eager to get married. I don’t know, maybe my father’s house was boring for me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“My parents used to argue badly. They blamed each other and I always wanted to run away from these arguments. I didn’t have the patience to talk to mom or dad and calm them down” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Overdependence

“My husband’s parents don’t stop interfering, but my husband doesn’t say anything because he is a student of his father. My husband is self-employed and works with his father on a truck” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“Every time I argue with my husband because of lack of money, my mother-in-law supported her son and brought him up very spoiled and lazy” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Bitter memories

“After three years, my mother married her friend with my uncle’s insistence and went to Shiraz. But, his condition was that she did not have the right to bring his daughter with her. In fact, my mother also got married out of necessity” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Some of their other statements related to “ Role failure” are mentioned below:

Lack of commitment to different roles

“I got angry several times and went to my father’s house because of my husband’s bad financial status and the fact that he doesn’t feel responsible to work and always says that he cannot find a job” (p 6, 48 yrs).

“I saw that he does not want to change in any way” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“No matter how kind I am, it does not work” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Repressors” are listed below:

Fear and silence

“My mother always forced me to continue living with my husband. Finally, my father had been poor. She all said that you didn’t listen to me when you wanted to get married, so you don’t have the right to get angry and come to me, I’m miserable enough” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“Because I suffered a lot in my first marital life. I was very humiliated. I said I would be fine with that. To be kind” (p1, 38 yrs).

“Well, I tell myself that he gets angry sometimes” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Shame from society

“I don’t want my daughter-in-law to know. She is not a relative” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Some of the statements of the participants regarding the theme of “ Efforts to preserve the family” are listed below:

Hope and trust

“I always hope in God and I am patient” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Efforts for children

“My divorce took a month. We got a divorce. I forgave my dowry and took my children instead” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Inappropriate solving of family conflicts” are listed below:

Child-bearing thoughts

“My husband wanted to take me to a doctor to treat me. But my father-in-law refused and said that instead of doing this and spending money, marry again. Marriage in the clans was much easier than any other work” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Lack of effective communication

“I was nervous about him, but I didn’t say anything” (p 5, 39 yrs).

“Now I am satisfied with my life and thank God it is better to listen to people’s words. Now there is someone above me so that people don’t talk behind me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Consequences” are listed below:

Harm to children

“My eldest daughter, who was about 7–8 years old, behaved differently. Oh, I was angry. My children are mentally depressed and argue” (p 5, 39 yrs).

After divorce

“Even though I got a divorce, my mother and I came to a remote area due to the fear of what my family would say” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Social harm

“I work at a retirement center for living expenses” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“I had to go to clean the houses” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Non-acceptance in the family

“The children’s relationship with their father became bad. Because every time they saw their father sitting at home smoking, they got angry” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Emotional harm

“When I look back, I regret why I was not careful in my choice” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“I felt very bad. For being married to a man who is not bound by the family and is capricious” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Inefficient supportive systems” are listed below:

Inappropriate family support

“We didn’t have children. I was at my father’s house for about a month. After a month, when I came home, I saw that my husband had married again. I cried a lot that day. He said, God, I had to. I love you. My heart is broken, I have no one to share my words” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My brother-in-law was like himself. His parents had also died. His sister did not listen at all” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“I didn’t have anyone and I was alone” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Inefficiency of social systems

“That day he argued with me, picked me up and threw me down some stairs in the middle of the yard. He came closer, sat on my stomach, grabbed my neck with both of his hands and wanted to strangle me. Until a long time later, I had kidney problems and my neck was bruised by her hand. Given that my aunt and her family were with us in a building, but she had no desire to testify and was afraid” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Undesired training and advice

“I told my mother, you just said no, how old I was? You never insisted on me and you didn’t listen to me that this man is not good for you” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Quantitative results

In the present study, 376 married women living in Semnan city participated in this study. The mean age of participants was 38.52 ± 10.38 years. The youngest participant was 18 and the oldest was 73 years old. The maximum age difference was 16 years. The years of marriage varied from one year to 40 years. Also, the number of children varied from no children to 7. The majority of them had 2 children (109, 29%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in the table below (Table 3 ).

The frequency distribution (number and percentage) of the participants in terms of the level of violence was as follows. 89 participants (23.7%) had experienced low violence, 59 participants (15.7%) had experienced moderate violence, and 228 participants (60.6%) had experienced severe violence.

Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.988. The mean and standard deviation of the total score of the questionnaire was 143.60 ± 74.70 with a range of 3-244. The relationship between the total score of the questionnaire and its fields, and some demographic variables is summarized in the table below (Table 4 ).

As shown in the table above, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage have a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of number of children has a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). However, the variable of education level difference showed no significant relationship with the total score and any of the fields. Also, the highest average score is related to patriarchal beliefs compared to other fields.

The comparison of the average total scores separately according to each variable showed the significant average difference in the variables of the previous marriage history of the woman, the result of the previous marriage of the woman, the education of the woman, the education of the man, the income of the woman, the income of the man, and the physical disease of the man (p < 0.05).

In the regression model, two variables remained in the final model, indicating the relationship between the variables and violence score and the importance of these two variables. An increase in women’s education and income level both independently show a significant relationship with an increase in violence score (Table 5 ).

The results of analysis of variance to compare the scores of each field of violence in the subgroups of the participants also showed that the experience and result of the woman’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with physical violence and tradition and family upbringing, the experience of the man’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with patriarchal belief, the education level of the woman has a significant relationship with all fields and the level of education of the man has a significant relationship with all fields except tradition and family upbringing (p < 0.05).

According to the results of both quantitative and qualitative studies, variables such as the young age of the woman and a large age difference are very important factors leading to an increase in violence. At a younger age, girls are afraid of the stigma of society and family, and being forced to remain silent can lead to an increase in domestic violence. As Gandhi et al. (2021) stated in their study in the same field, a lower marriage age leads to many vulnerabilities in women. Early marriage is a global problem associated with a wide range of health and social consequences, including violence for adolescent girls and women [ 12 ]. Also, Ahmadi et al. (2017) found similar findings, reporting a significant association among IPV and women age ≤ 40 years [ 19 ].

Two others categories of “Facilitators” in the present study were “Husband’s criminal record” and “Overdependence” which had a sub-category of “Forced cohabitation”. Ahmadi et al. (2017) reported in their population-based study in Iran that husband’s addiction and rented-householders have a significant association with IPV [ 19 ].

The patriarchal beliefs, which are rooted in the tradition and culture of society and family upbringing, scored the highest in relation to domestic violence in this study. On the other hand, in qualitative study, “Normalcy” of men’s anger and harassment of women in society is one of the “Repressors” of women to express violence. In the quantitative study, the increase in the women’s education and income level were predictors of the increase in violence. Although domestic violence is more common in some sections of society, women with a wide range of ages, different levels of education, and at different levels of society face this problem, most of which are not reported. Bukuluki et al. (2021) showed that women who agreed that it is good for a man to control his partner were more likely to experience physical violence [ 20 ].

Domestic violence leads to “Consequences” such as “Harm to children”, “Emotional harm”, “Social harm” to women and even “Non-acceptance in their own family”. Because divorce is a taboo in Iranian culture and the fear of humiliating women forces them to remain silent against domestic violence. Balsarkar (2021) stated that the fear of violence can prevent women from continuing their studies, working or exercising their political rights [ 8 ]. Also, Walker-Descarte et al. (2021) recognized domestic violence as a type of child maltreatment, and these abusive behaviors are associated with mental and physical health consequences [ 21 ].

On the other hand and based on the “Lack of effective communication” category, ignoring the role of the counselor in solving family conflicts and challenges in the life of couples in the present study was expressed by women with reasons such as lack of knowledge and family resistance to counseling. Several pathologies are needed to investigate increased domestic violence in situations such as during women’s pregnancy or infertility. Because the use of counseling for couples as a suitable solution should be considered along with their life challenges. Lin et al. (2022) stated that pregnant women were exposed to domestic violence for low birth weight in full term delivery. Spouse violence screening in the perinatal health care system should be considered important, especially for women who have had full-term low birth weight infants [ 22 ].

Also, lack of knowledge and low level of education have been found as other factors of violence in this study, which is very prominent in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Because the social systems and information about the existing laws should be followed properly in society to act as a deterrent. Psychological training and especially anger control and resilience skills during education at a younger age for girls and boys should be included in educational materials to determine the positive results in society in the long term. Manouchehri et al. (2022) stated that it seems necessary to train men about the negative impact of domestic violence on the current and future status of the family [ 23 ]. Balsarkar (2021) also stated that men and women who have not had the opportunity to question gender roles, attitudes and beliefs cannot change such things. Women who are unaware of their rights cannot claim. Governments and organizations cannot adequately address these issues without access to standards, guidelines and tools [ 8 ]. Machado et al. (2021) also stated that gender socialization reinforces gender inequalities and affects the behavior of men and women. So, highlighting this problem in different fields, especially in primary health care services, is a way to prevent IPV against women [ 24 ].

There was a sub-category of “Inefficiency of social systems” in the participants experiences. Perhaps the reason for this is due to insufficient education and knowledge, or fear of seeking help. Holmes et al. (2022) suggested the importance of ascertaining strategies to improve victims’ experiences with the court, especially when victims’ requests are not met, to increase future engagement with the system [ 25 ]. Sigurdsson (2019) revealed that despite high prevalence numbers, IPV is still a hidden and underdiagnosed problem and neither general practitioner nor our communities are as well prepared as they should be [ 26 ]. Moreira and Pinto da Costa (2021) found that while victims of domestic violence often agree with mandatory reporting, various concerns are still expressed by both victims and healthcare professionals that require further attention and resolution [ 27 ]. It appears that legal and ethical issues in this regard require comprehensive evaluation from the perspectives of victims, their families, healthcare workers, and legal experts. By doing so, better practical solutions can be found to address domestic violence, leading to a downward trend in its occurrence.

Some of the variables of violence against women have been identified and emphasized in many studies, highlighting the necessity of policymaking and social pathology in society to prevent and use operational plans to take action before their occurrence. Breaking the taboo of domestic violence and promoting divorce as a viable solution after counseling to receive objective results should be implemented seriously to minimize harm to women, children, and their families.

Limitations

Domestic violence against women is an important issue in Iranian society that women resist showing and expressing, making researchers take a long-term process of sampling in both qualitative and quantitative studies. The location of the interview and the women’s fear of their husbands finding out about their participation in this study have been other challenges of the researchers, which, of course, they attempted to minimize by fully respecting ethical considerations. Despite the researchers’ efforts, their personal and professional experiences, as well as the studies reviewed in the literature review section, may have influenced the study results.

Data Availability

Data and materials will be available upon email to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Intimate Partner Violence

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Organization WH. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization; 2021.

Huecker MR, Malik A, King KC, Smock W. Kentucky Domestic Violence. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Ahmad Malik declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Kevin King declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: William Smock declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023.

Gandhi A, Bhojani P, Balkawade N, Goswami S, Kotecha Munde B, Chugh A. Analysis of survey on violence against women and early marriage: Gyneaecologists’ perspective. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71(Suppl 2):76–83.

Article Google Scholar

Sugg N. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, health consequences, and intervention. Med Clin. 2015;99(3):629–49.

Google Scholar

Abebe Abate B, Admassu Wossen B, Tilahun Degfie T. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):1–8.

Adineh H, Almasi Z, Rad M, Zareban I, Moghaddam A. Prevalence of domestic violence against women in Iran: a systematic review. Epidemiol (Sunnyvale). 2016;6(276):2161–11651000276.

Pirnia B, Pirnia F, Pirnia K. Honour killings and violence against women in Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):e60.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Balsarkar G. Summary of four recent studies on violence against women which obstetrician and gynaecologists should know. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2021;71:64–7.

Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. The lancet. 2008;371(9619):1165–72.

Chasweka R, Chimwaza A, Maluwa A. Isn’t pregnancy supposed to be a joyful time? A cross-sectional study on the types of domestic violence women experience during pregnancy in Malawi. Malawi Med journal: J Med Association Malawi. 2018;30(3):191–6.

Afshari P, Tadayon M, Abedi P, Yazdizadeh S. Prevalence and related factors of postpartum depression among reproductive aged women in Ahvaz. Iran Health care women Int. 2020;41(3):255–65.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gebrezgi BH, Badi MB, Cherkose EA, Weldehaweria NB. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study, July 2015. Reproductive health. 2017;14:1–10.

Duran S, Eraslan ST. Violence against women: affecting factors and coping methods for women. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019;69(1):53–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mahapatro M, Kumar A. Domestic violence, women’s health, and the sustainable development goals: integrating global targets, India’s national policies, and local responses. J Public Health Policy. 2021;42(2):298–309.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry: sage; 1985.

Colaizzi PF. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. 1978.

Mohseni Tabrizi A, Kaldi A, Javadianzadeh M. The study of domestic violence in Marrid Women Addmitted to Yazd Legal Medicine Organization and Welfare Organization. Tolooebehdasht. 2013;11(3):11–24.

Ahmadi R, Soleimani R, Jalali MM, Yousefnezhad A, Roshandel Rad M, Eskandari A. Association of intimate partner violence with sociodemographic factors in married women: a population-based study in Iran. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(7):834–44.

Bukuluki P, Kisaakye P, Wandiembe SP, Musuya T, Letiyo E, Bazira D. An examination of physical violence against women and its justification in development settings in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0255281.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walker-Descartes I, Mineo M, Condado LV, Agrawal N. Domestic violence and its Effects on Women, Children, and families. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2021;68(2):455–64.

Lin C-H, Lin W-S, Chang H-Y, Wu S-I. Domestic violence against pregnant women is a potential risk factor for low birthweight in full-term neonates: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12):e0279469.

Manouchehri E, Ghavami V, Larki M, Saeidi M, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Domestic violence experienced by women with multiple sclerosis: a study from the North-East of Iran. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):1–14.

Machado DF, Castanheira ERL, Almeida MASd. Intersections between gender socialization and violence against women by the intimate partner. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2021;26:5003–12.

Holmes SC, Maxwell CD, Cattaneo LB, Bellucci BA, Sullivan TP. Criminal Protection orders among women victims of intimate Partner violence: Women’s Experiences of Court decisions, processes, and their willingness to Engage with the system in the future. J interpers Violence. 2022;37(17–18):Np16253–np76.

Sigurdsson EL. Domestic violence-are we up to the task? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(2):143–4.

Moreira DN, Pinto da Costa M. Should domestic violence be or not a public crime? J Public Health. 2021;43(4):833–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study appreciate the Deputy for Research and Technology of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Social Determinants of Health Research Center of Semnan University of Medical Sciences and all the participants in this study.

Research deputy of Semnan University of Medical Sciences financially supported this project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Mina Shayestefar & Mohadese Saffari

Amir Al Momenin Hospital, Social Security Organization, Ahvaz, Iran

Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Monir Nobahar & Majid Mirmohammadkhani

Clinical Research Development Unit, Kowsar Educational, Research and Therapeutic Hospital, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh

Student Research Committee, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Zahra Khosravi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.Sh. contributed to the first conception and design of this research; M.Sh., Z.Kh., M.S., R.Gh. and S.H.Sh. contributed to collect data; M.N. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the qualitative data; M.M. and M.Sh. contributed to the analysis of the quantitative data; M.SH., M.N. and M.M. contributed to the interpretation of the data; M.Sh., M.S. and S.H.Sh. wrote the manuscript. M.Sh. prepared the final version of manuscript for submission. All authors reviewed the manuscript meticulously and approved it. All names of the authors were listed in the title page.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mina Shayestefar .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This article is resulted from a research approved by the Vice Chancellor for Research of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethics code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182 in the Social Determinants of Health Research Center. The authors confirmed that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants accepted the participation in the present study. The researchers introduced themselves to the research units, explained the purpose of the research to them and then all participants signed the written informed consent. The research units were assured that the collected information was anonymous. The participant was informed that participating in the study was completely voluntary so that they can safely withdraw from the study at any time and also the availability of results upon their request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shayestefar, M., Saffari, M., Gholamhosseinzadeh, R. et al. A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women. BMC Women's Health 23 , 322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Download citation

Received : 28 April 2023

Accepted : 14 June 2023

Published : 20 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02483-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Domestic violence

- Cross-sectional studies

- Qualitative research

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychiatry

- PMC10513418

Exploring factors influencing domestic violence: a comprehensive study on intrafamily dynamics

Cintya lanchimba.

1 Departamento de Economía Cuantitativa, Facultad de Ciencias Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador

2 Institut de Recherche en Gestion et Economie, Université de Savoie Mont Blanc (IREGE/IAE Savoie Mont Blanc), Annecy, France

Juan Pablo Díaz-Sánchez

Franklin velasco.

3 Department of Marketing, Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Quito, Ecuador

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Introduction

This econometric analysis investigates the nexus between household factors and domestic violence. By considering diverse variables encompassing mood, depression, health consciousness, social media engagement, household chores, density, and religious affiliation, the study aims to comprehend the underlying dynamics influencing domestic violence.

Employing econometric techniques, this study examined a range of household-related variables for their potential associations with levels of violence within households. Data on mood, depression, health consciousness, social media usage, household chores, density, and religious affiliation were collected and subjected to rigorous statistical analysis.

The findings of this study unveil notable relationships between the aforementioned variables and levels of violence within households. Positive mood emerges as a mitigating factor, displaying a negative correlation with violence. Conversely, depression positively correlates with violence, indicating an elevated propensity for conflict. Increased health consciousness is linked with diminished violence, while engagement with social media demonstrates a moderating influence. Reduction in the time allocated to household chores corresponds with lower violence levels. Household density, however, exhibits a positive association with violence. The effects of religious affiliation on violence manifest diversely, contingent upon household position and gender.

The outcomes of this research offer critical insights for policymakers and practitioners working on formulating strategies for preventing and intervening in instances of domestic violence. The findings emphasize the importance of considering various household factors when designing effective interventions. Strategies to bolster positive mood, alleviate depression, encourage health consciousness, and regulate social media use could potentially contribute to reducing domestic violence. Additionally, the nuanced role of religious affiliation underscores the need for tailored approaches based on household dynamics, positioning, and gender.

1. Introduction

Intimate partner violence is a pervasive global issue, particularly affecting women. According to the World Health Organization ( 1 ), approximately 30% of women worldwide have experienced violence from their intimate partners. Disturbingly, recent studies indicate that circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupt daily lives on a global scale, have exacerbated patterns of violence against women ( 2 – 4 ). Data from the WHO ( 1 ) regarding gender-based violence during the pandemic reveals that one in three women felt insecure within their homes due to family conflicts with their partners.

This pressing issue of intimate partner violence demands a thorough analysis from a social perspective. It is often insidious and challenging to identify, as cultural practices and the normalization of abusive behaviors, such as physical aggression and verbal abuse, persist across diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. However, all forms of violence can inflict physical and psychological harm on victims, affecting their overall well-being and interpersonal relationships WHO ( 5 ). Furthermore, households with a prevalence of domestic violence are more likely to experience child maltreatment ( 6 ).

In this context, the COVID-19 pandemic has had profound effects on individuals, families, and communities worldwide, creating a complex landscape of challenges and disruptions. Among the numerous repercussions, the pandemic has exposed and exacerbated issues of domestic violence within households. The confinement measures, economic strain, and heightened stress levels resulting from the pandemic have contributed to a volatile environment where violence can escalate. Understanding the factors that influence domestic violence during this unprecedented crisis is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies.

This article aims to explore the relationship between household factors and domestic violence within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. By employing econometric analysis, we investigate how various factors such as mood, depression, health consciousness, social media usage, household chores, density, and religious affiliation relate to violence levels within households. These factors were selected based on their relevance to the unique circumstances and challenges presented by the pandemic.

The study builds upon existing research that has demonstrated the influence of individual and household characteristics on domestic violence. However, the specific context of the pandemic necessitates a deeper examination of these factors and their implications for violence within households. By focusing on variables that are particularly relevant in the crisis, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics that contribute to intrafamily violence during the pandemic.

The findings of this study have important implications for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers involved in addressing domestic violence. By identifying the factors that either increase or mitigate violence within households, we can develop targeted interventions and support systems to effectively respond to the unique challenges posed by the pandemic. Furthermore, this research contributes to the broader literature on domestic violence by highlighting the distinct influence of household factors within the context of a global health crisis.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature on household violence. Section 3 presents the case study that forms the basis of this research. Section 4 outlines the methodology employed in the study. Section 5 presents the results obtained from the empirical analysis. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper, summarizing the key findings and their implications for addressing domestic violence.

2. Literature review

2.1. violence at home.

Throughout human history, the family unit has been recognized as the fundamental building block of society. Families are comprised of individuals bound by blood or marriage, and they are ideally regarded as havens of love, care, affection, and personal growth, where individuals should feel secure and protected. Unfortunately, it is distressingly common to find alarming levels of violence, abuse, and aggression within the confines of the home ( 7 ).

Domestic violence, as defined by Tan and Haining ( 8 ), encompasses any form of violent behavior directed toward family members, regardless of their gender, resulting in physical, sexual, or psychological harm. It includes acts of threats, coercion, and the deprivation of liberty. This pervasive issue is recognized as a public health problem that affects all nations. It is important to distinguish between domestic violence (DV) and intimate partner violence (IPV), as they are related yet distinct phenomena. DV occurs within the family unit, affecting both parents and children. On the other hand, IPV refers to violent and controlling acts perpetrated by one partner against another, encompassing physical aggression (such as hitting, kicking, and beating), sexual, economic, verbal, or emotional harm ( 9 , 10 ). IPV can occur between partners who cohabit or not, and typically involves male partners exerting power and control over their female counterparts. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that there are cases where men are also victims of violence ( 11 ).

Both forms of violence, DV and IPV, take place within the home. However, when acts of violence occur in the presence of children, regardless of whether they directly experience physical harm or simply witness the violence, the consequences can be profoundly detrimental ( 12 , 13 ).

Understanding the intricacies and dynamics of domestic violence and its impact on individuals and families is of paramount importance. The consequences of such violence extend beyond the immediate victims, affecting the overall well-being and social fabric of society. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the various factors that contribute to domestic violence, including those specific to the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to inform effective prevention and intervention strategies. In the following sections, we will examine the empirical findings regarding household factors and their association with domestic violence, shedding light on the complexities and nuances of this pervasive issue.

2.2. Drivers of domestic violence

As previously discussed, the occurrence of violence within the home carries significant consequences for individuals’ lives. Consequently, gaining an understanding of the underlying factors that contribute to this violence is crucial. To this end, Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of the most commonly identified determinants of domestic violence within the existing literature.

Determinants of domestic violence.

Adapted and improved from the classification proposed by Visaria ( 16 ).

Identifying these determinants is a vital step toward comprehending the complex nature of domestic violence. By synthesizing the findings from numerous studies, Table 1 presents a consolidated overview of the factors that have been consistently associated with domestic violence. This compilation serves as a valuable resource for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers seeking to address and mitigate the prevalence of domestic violence.

The determinants presented in Table 1 encompass various variables, including socio-economic factors, mental health indicators, interpersonal dynamics, and other relevant aspects. By examining and analyzing these determinants, researchers have made significant progress in uncovering the underlying causes and risk factors associated with domestic violence.

It is important to note that the determinants listed in Table 1 represent recurring themes in the literature and are not an exhaustive representation of all potential factors influencing domestic violence. The complex nature of this issue necessitates ongoing research and exploration to deepen our understanding of the multifaceted dynamics at play. Thus, we categorize these factors into two groups to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issue.

Group A focuses on variables that characterize both the victim and the aggressor, which may act as potential deterrents against femicide. Previous research by Alonso-Borrego and Carrasco ( 17 ), Anderberg et al. ( 18 ), Sen ( 19 ), and Visaria ( 16 ) has highlighted the significance of factors such as age, level of education, employment status, occupation, and religious affiliation. These individual characteristics play a role in shaping the dynamics of domestic violence and can influence the likelihood of its occurrence.

Group B aims to capture risk factors that contribute to the presence of violence within the home. One prominent risk factor is overcrowding, which can lead to psychological, social, and economic problems within the family, ultimately affecting the health of its members. Research by Van de Velde et al. ( 21 ), Walker-Descartes et al. ( 23 ), Malik and Naeem ( 2 ) supports the notion that individuals experiencing such distress may resort to exerting force or violence on other family members as a means of releasing their frustration. Additionally, Goodman ( 32 ) have highlighted the increased risk of violence in households with multiple occupants, particularly in cases where individuals are confined to a single bedroom. These concepts can be further explored through variables related to health, depression, anxiety, and stress, providing valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying domestic violence.

By investigating these factors, our study enhances the existing understanding of the complex dynamics of domestic violence within the unique context of the pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis has exacerbated various stressors and challenges within households, potentially intensifying the risk of violence. Understanding the interplay between these factors and domestic violence is essential for the development of targeted interventions and support systems to mitigate violence and its consequences.

2.3. Demographic characteristics (A)

2.3.1. education level (a1).

According to Sen ( 19 ), the education level of the victim, typically women, or the head of household is a significant antecedent of domestic violence. Women’s access to and completion of secondary education play a crucial role in enhancing their capacity and control over their lives. Higher levels of education not only foster confidence and self-esteem but also empower women to seek help and resources, ultimately reducing their tolerance for domestic violence. Babu and Kar ( 33 ), Semahegn and Mengistie ( 34 ) support this perspective by demonstrating that women with lower levels of education and limited work opportunities are more vulnerable to experiencing violence.

When women assume the role of the head of the household, the likelihood of violence within the household, whether domestic or intimate partner violence, increases significantly. This has severe physical and mental health implications for both the woman and other family members, and in the worst-case scenario, it can result in the tragic loss of life ( 22 , 23 , 35 ).

Conversely, men’s economic frustration or their inability to fulfill the societal expectation of being the “head of household” is also a prominent factor contributing to the perpetration of physical and sexual violence within the home ( 36 ).The frustration arising from economic difficulties, combined with the frequent use of drugs and alcohol, exacerbates the likelihood of violent behavior.

These findings underscore the importance of addressing socio-economic disparities and promoting gender equality in preventing and combating domestic violence. By enhancing women’s access to education, improving economic opportunities, and challenging traditional gender roles, we can create a more equitable and violence-free society. Additionally, interventions targeting men’s economic empowerment and addressing substance abuse issues can play a pivotal role in reducing violence within the home.

2.3.2. Employment and occupation (A2)

Macroeconomic conditions, specifically differences in unemployment rates between men and women, have been found to impact domestic violence. Research suggests that an increase of 1% in the male unemployment rate is associated with an increase in physical violence within the home, while an increase in the female unemployment rate is linked to a reduction in violence ( 37 ).

Moreover, various studies ( 34 , 35 , 38 , 39 ) have highlighted the relationship between domestic violence and the husband’s working conditions, such as workload and job quality, as well as the income he earns. The exercise of authority within the household and the use of substances that alter behavior are also associated with domestic violence.

Within this context, economic gender-based violence is a prevalent but lesser-known form of violence compared to physical or sexual violence. It involves exerting unacceptable economic control over a partner, such as allocating limited funds for expenses or preventing them from working to maintain economic dependence. This form of violence can also manifest through excessive and unsustainable spending without consulting the partner. Economic gender-based violence is often a “silent” form of violence, making it more challenging to detect and prove ( 40 ).

Empowerment becomes a gender challenge that can lead to increased violence, as men may experience psychological stress when faced with the idea of women earning more than them ( 14 , 18 ). Lastly, Alonso-Borrego and Carrasco ( 17 ) and Tur-Prats ( 41 ) conclude that intrafamily violence decreases only when the woman’s partner is also employed, highlighting the significance of economic factors in influencing domestic violence dynamics.

Understanding the interplay between macroeconomic conditions, employment, and economic control within intimate relationships is crucial for developing effective interventions and policies aimed at reducing domestic violence. By addressing the underlying economic inequalities and promoting gender equality in both the labor market and household dynamics, we can work toward creating safer and more equitable environments that contribute to the prevention of domestic violence.

2.3.3. Religion (A3)

Religion and spiritual beliefs have been found to play a significant role in domestic violence dynamics. Certain religious interpretations and teachings can contribute to the acceptance of violence, particularly against women, as a form of submission or obedience. This phenomenon is prevalent in Middle Eastern countries, where religious texts such as the Bible and the Qur’an are often quoted to justify and perpetuate gender-based violence ( 20 ).

For example, in the book of Ephesians 5:22–24, the Bible states that wives should submit themselves to their husbands, equating the husband’s authority to that of the Lord. Similarly, the Qur’an emphasizes the importance of wives being sexually available to their husbands in all aspects of their relationship. These religious teachings can create a belief system where women are expected to endure mistreatment and forgive their abusive partners ( 15 ).

The influence of religious beliefs and practices can complicate a woman’s decision to leave an abusive relationship, particularly when marriage is considered a sacred institution. Feelings of guilt and difficulties in seeking support or ending the relationship can arise due to the belief that marriage is ordained by God ( 15 ).

It is important to note that the response of religious congregations and communities to domestic violence can vary. In some cases, if abuse is ignored or not condemned, it may perpetuate the cycle of violence and hinder efforts to support victims and hold perpetrators accountable. However, in other instances, religious organizations may provide emotional support and assistance through dedicated sessions aimed at helping all affected family members heal and address the violence ( 20 ).

Recognizing the influence of religious beliefs on domestic violence is crucial for developing comprehensive interventions and support systems that address the specific challenges faced by individuals within religious contexts. This includes promoting awareness, education, and dialog within religious communities to foster an understanding that violence is never acceptable and to facilitate a safe environment for victims to seek help and healing.

2.4. Presence of risk factor (B)

2.4.1. depression, anxiety, and stress (b1).

Within households, the occurrence of violence is unfortunately prevalent, often stemming from economic constraints, social and psychological problems, depression, and stress. These factors instill such fear in the victims that they are often hesitant to report the abuse to the authorities ( 42 ).

Notably, when women assume the role of heads of households, they experience significantly higher levels of depression compared to men ( 21 ). This study highlights that the presence of poverty, financial struggles, and the ensuing violence associated with these circumstances significantly elevate the risk of women experiencing severe health disorders, necessitating urgent prioritization of their well-being. Regrettably, in low-income countries where cases of depression are on the rise within public hospitals, the provision of adequate care becomes an insurmountable challenge ( 21 ).

These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive support systems and targeted interventions that address the multifaceted impact of domestic violence on individuals’ mental and physical health. Furthermore, effective policies should be implemented to alleviate economic hardships and provide accessible mental health services, particularly in low-income settings. By addressing the underlying factors contributing to violence within households and ensuring adequate care for those affected, society can take significant strides toward breaking the cycle of violence and promoting a safer and more supportive environment for individuals and families.

2.4.2. Retention tendency (B2)

Many societies, particularly in Africa, are characterized by a deeply ingrained patriarchal social structure, where men hold the belief that they have the right to exert power and control over their partners ( 31 ). This ideology of patriarchy is often reinforced by women themselves, who may adhere to traditional gender roles and view marital abuse as a norm rather than recognizing it as an act of violence. This acceptance of abuse is influenced by societal expectations and cultural norms that prioritize the preservation of marriage and the submission of women.

Within these contexts, there is often a preference for male children over female children, as males are seen as essential for carrying on the family name and lineage ( 43 ). This preference is also reflected in the distribution of property and decision-making power within households, where males are given greater rights and authority. Such gender-based inequalities perpetuate the cycle of power imbalances and contribute to the normalization of violence against women.

It is important to note that men can also be victims of domestic violence. However, societal and cultural norms have long portrayed men as strong and superior figures, making it challenging for male victims to come forward and report their abusers due to the fear of being stigmatized and rejected by society ( 16 ). The cultural expectations surrounding masculinity create barriers for men seeking help and support, further perpetuating the silence around male victimization.

These cultural dynamics underscore the complexity of domestic violence within patriarchal societies. Challenging and dismantling deeply rooted gender norms and power structures is essential for addressing domestic violence effectively. This includes promoting gender equality, empowering women, and engaging men and boys in efforts to combat violence. It also requires creating safe spaces and support systems that encourage both women and men to break the silence, seek help, and challenge the harmful societal narratives that perpetuate violence and victim-blaming.

2.4.3. Density (B3)

Moreover, the issue of overcrowding within households has emerged as another important factor influencing domestic violence. Overcrowding refers to the stress caused by the presence of a large number of individuals in a confined space, leading to a lack of control over one’s environment ( 44 ). This overcrowding can have a detrimental impact on the psychological well-being of household members, thereby negatively affecting their internal relationships.

The freedom to use spaces within the home and the ability to control interactions with others have been identified as crucial factors that contribute to satisfaction with the home environment and the way individuals relate to each other. In this regard, studies have shown that when households are crowded, and individuals lack personal space and control over their living conditions, the risk of violence may increase ( 45 ).

Furthermore, investigations conducted during periods of extensive confinement, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have shed light on the significance of other environmental factors within homes ( 46 ). For instance, aspects like proper ventilation and adequate living space have been found to influence the overall quality of life and the health of household inhabitants.

These findings emphasize the importance of considering the physical living conditions and environmental factors within households when examining the dynamics of domestic violence. Addressing issues of overcrowding, promoting healthy and safe living environments, and ensuring access to basic amenities and resources are crucial steps in reducing the risk of violence and improving the well-being of individuals and families within their homes.

2.4.4. Reason for confrontation (B4)

Another form of violence that exists within households is abandonment and neglect, which manifests through a lack of protection, insufficient physical care, neglecting emotional needs, and disregarding proper nutrition and medical care ( 47 ). This definition highlights that any member of the family can be subjected to this form of violence, underscoring the significance of recognizing its various manifestations.

In this complex context, negative thoughts and emotions can arise, leading to detrimental consequences. For instance, suspicions of infidelity and feelings of jealousy can contribute to a decrease in the partner’s self-esteem, ultimately triggering intimate partner violence that inflicts physical, social, and health damages ( 32 , 48 ).

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the intimate connection between domestic violence and civil issues. Marital conflicts, particularly when accompanied by violence, whether physical or psychological, can lead to a profound crisis within the relationship, often resulting in divorce. Unfortunately, the process of obtaining a divorce or establishing parental arrangements can be protracted, creating additional friction and potentially exacerbating gender-based violence ( 49 ).

These dynamics underscore the complex interplay between domestic violence and broader social, emotional, and legal contexts. Understanding these interconnected factors is crucial for developing effective interventions and support systems that address the multifaceted nature of domestic violence, promote healthy relationships, and safeguard the well-being of individuals and families within the home.

Finally, despite the multitude of factors identified in the existing literature that may have an impact on gender-based violence, we have selected a subset of variables for our study based on data availability. Specifically, our analysis will concentrate on the following factors reviewed: (A3) religion, (B1) depression, health consciousness, and mood, (B2) retention tendency as reflected by household chores, and (B3) density.

The rationale behind our choice of these variables stems from their perceived significance and potential relevance to the study of domestic violence. Religion has been widely acknowledged as a social and cultural determinant that shapes beliefs, values, and gender roles within a society, which may have implications for power dynamics and relationship dynamics within households. Depression, as a psychological construct, has been frequently associated with increased vulnerability and impaired coping mechanisms, potentially contributing to the occurrence or perpetuation of domestic violence. Health consciousness and mood are additional constructs that have garnered attention in the context of interpersonal relationships. Health consciousness relates to individuals’ awareness and concern for their own well-being and that of others, which may influence their attitudes and behaviors within the household. Mood, on the other hand, reflects emotional states that can influence communication, conflict resolution, and overall dynamics within intimate relationships.

Furthermore, we have included the variable of retention tendency, as manifested through household chores. This variable is indicative of individuals’ willingness or inclination to maintain their involvement and responsibilities within the household. It is hypothesized that individuals with higher retention tendencies may exhibit a greater commitment to the relationship, which could influence the occurrence and dynamics of domestic violence. Lastly, we consider the variable of density, which captures the population density within the living environment. This variable may serve as a proxy for socio-environmental conditions, such as overcrowding or limited personal space, which can potentially contribute to stress, conflict, and interpersonal tensions within households.

By examining these selected factors, we aim to gain insights into their relationships with domestic violence and contribute to a better understanding of the complex dynamics underlying such occurrences. It is important to note that these variables represent only a subset of the broader range of factors that influence gender-based violence, and further research is warranted to explore additional dimensions and interactions within this multifaceted issue.

3. Data collection and variables

The reference population for this study is Ecuadorian habitants. Participants were invited to fill up a survey concerning COVID-19 impact on their mental health. Data collection took place between April and May 2020, exactly at the time of the mandatory lockdowns taking place. In this context governmental authorities ordered mobility restrictions as well as social distancing measures. We conduct three waves of social media invitations to participate in the study. Invitations were sent using the institutional accounts of the universities the authors of this study are affiliated. At the end, we received 2,403 answers, 50.5% females and 49.5% males. 49% of them have college degrees.

3.1. Ecuador stylized facts

Ecuador, a small developing country in South America, has a population of approximately 17 million inhabitants, with a population density of 61.85 people per square kilometer.

During the months under investigation, the Central Bank of Ecuador reported that the country’s GDP in the fourth quarter of 2020 amounted to $16,500 million. This represented a decrease of 7.2% compared to the same period in 2019, and a 5.6% decline in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the same quarter of the previous year. However, despite these declines, there was a slight growth of 0.6% in the GDP during the fourth quarter of 2020 and 0.7% in the first quarter of 2021 when compared to the previous quarter.

In mid-March, the Ecuadorian government implemented a mandatory lockdown that lasted for several weeks. By July 30, 2020, Ecuador had reported over 80,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19. The statistics on the impact of the pandemic revealed a death rate of 23.9 per 100,000 inhabitants, ranking Ecuador fourth globally behind the UK, Italy, and the USA, with rates of 63.7, 57.1, and 36.2, respectively. Additionally, Ecuador’s observed case-fatality ratio stood at 8.3%, placing it fourth globally after Italy, the UK, and Mexico, with rates of 14.5, 14, and 11.9%, respectively ( 50 ). As the lockdown measures continued, mental health issues began to emerge among the population ( 51 ).

The challenging socioeconomic conditions and the impact of the pandemic on public health have had significant repercussions in Ecuador, highlighting the need for comprehensive strategies to address both the immediate and long-term consequences on the well-being of its population.

3.2. Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study is Domestic Violence, which is measured using a composite score derived from five items. These items were rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (very frequent), to assess the frequency of intrafamily conflict and violence occurring within the respondents’ homes. The five items included the following statements: “In my house, subjects are discussed with relative calm”; “In my house, heated discussions are common but without shouting at each other”; “Anger is common in my house, and I refuse to talk to others”; “In my house, there is the threat that someone will hit or throw something”; and “In my house, family members get easily irritated.”