You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Simon Pan is a Product Designer based in San Francisco.

Perfecting the Pickup

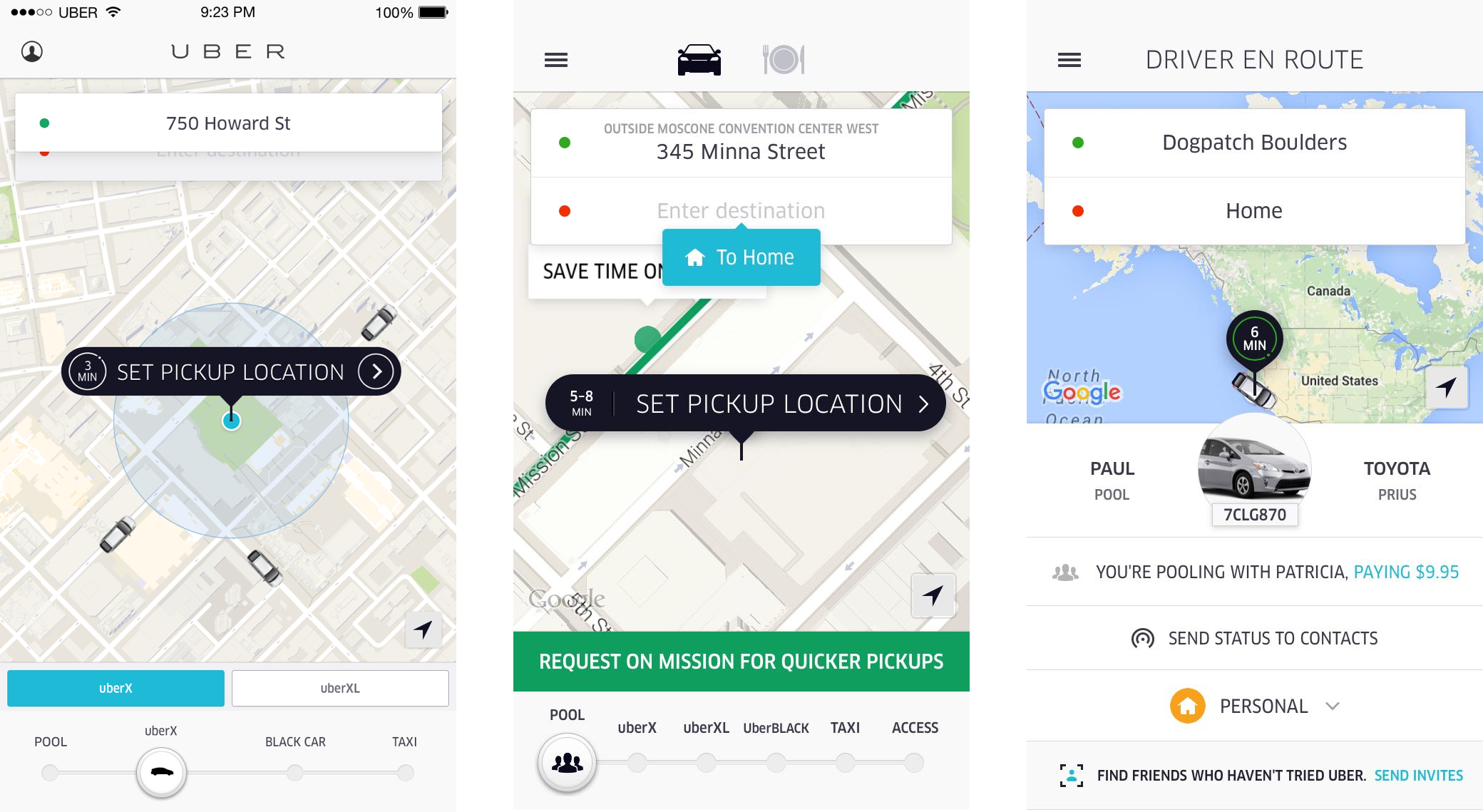

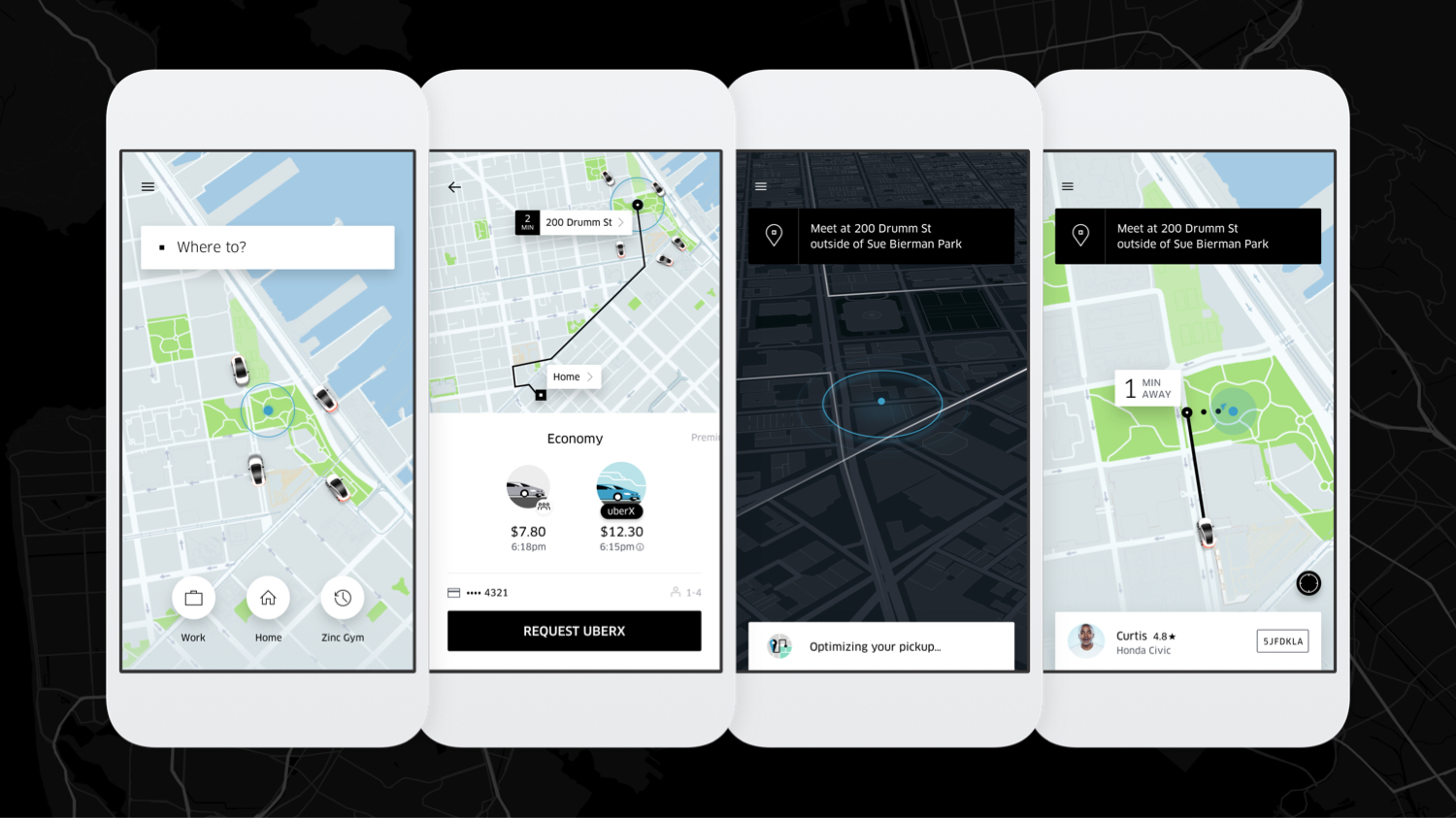

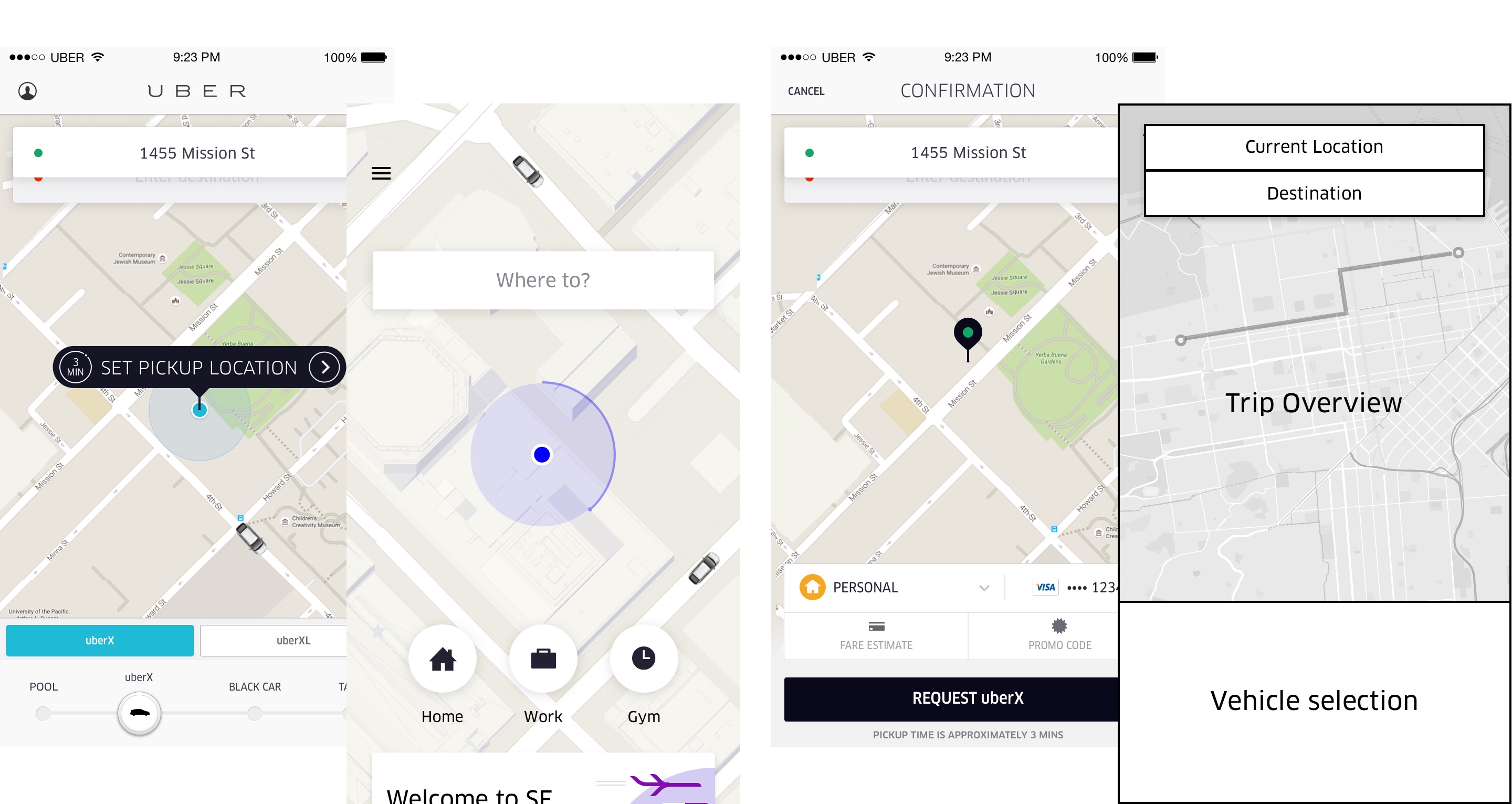

In 2012, tapping a button to Uber across the city felt magical. By the start of 2016, this magic receded to a slew of disparate features that made the experience slow and complex to use.

I was part of an ambitious project to redesign the Uber pickup experience for the fastest growing startup in history.

To comply with my non-disclosure agreement, I have omitted and obfuscated confidential information in this case study. All information in this case study is my own and does not necessarily reflect the views of Uber.

Design by accretion

In just five years since 2011, Uber transformed from a black car service for 100 friends in San Francisco to a global transportation network. By 2016, Uber delivered over 3 million rides a day in over 400 cities across 70 countries.

The Rider app — designed in 2012, struggled to scale alongside the hyper-growth of the company. Fundamental usability was challenged. Disparate features and experiments competed for focus. App reliability and performance issues increased exponentially.

The Rider app had become the org chart.

The Challenge

Recapture the magic in 10 months.

Our goal for the project was to recapture the magic of the early days of Uber. The original premise was simple: tap a button, get a ride. However, we weren't trying to revert to a simple past. Our ambitions were to create a strong foundation that embraced a rapidly evolving business and more diverse user base.

Our high level goals were to:

- Make it fast and easy to use for everyone, everywhere.

- Give riders more control over their time and money.

- Create a platform for innovation and deeper engagement.

I led the design of the pickup experience between October 2015 and June 2016 and collaborated with two other designers on the Home screen, Search and On Trip features.

In addition, I worked alongside a Researcher, Prototyper, Content Strategist and 2 Product Managers.

I stopped working on the project during the detailed visual design phase as the app started to be built.

The app launched globally on November 2nd, 2016.

Picking up the pieces

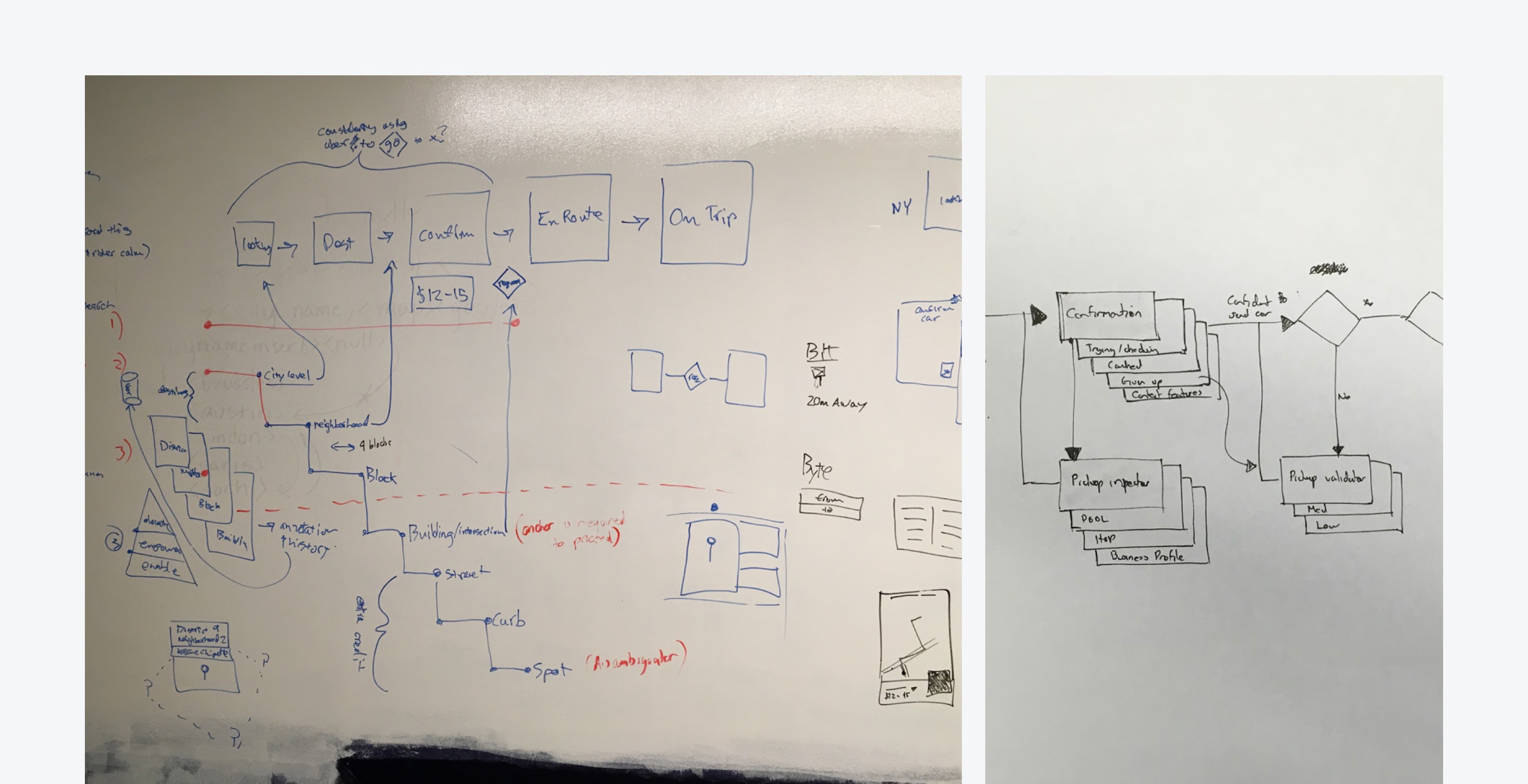

At the outset of the project we didn’t have a clear mission or specific goals for the pickup experience. Without pre-existing insights, I partnered with our researcher Shruti to explore how Riders were getting around.

Early Insights from the Field

We tested the existing Uber app with 8 participants in the most problematic pickup areas in San Francisco. Our goals were to understand the challenges Riders and Drivers faced and the workarounds they employed.

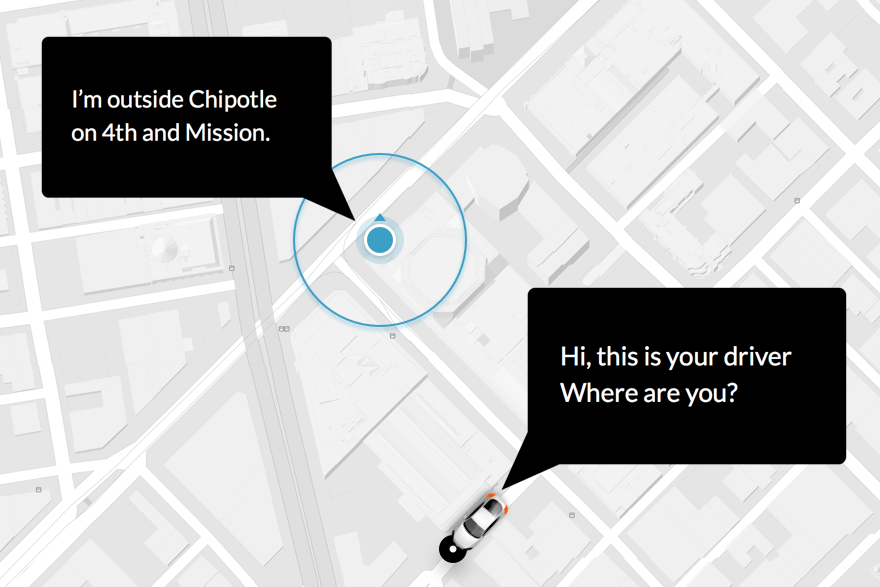

Frequent contact to confirm or coordinate location

Riders were annoyed when they were contacted by their Driver to confirm the location. Riders expected Uber to do the work and didn't feel the need to reiterate.

Suboptimal routes given to Driver

Riders were frustrated with the specific routes that the Driver used in getting to their pickup location. Riders expected Uber routing to be smarter.

Unexpected arrival location

Often, Drivers did not arrive where the Rider expected. Riders would need to cross the road, backtrack on the block or negotiate an alternative pickup location.

Pin setters and button mashers

Riders behave in two distinct ways. Those who explicitly set a pickup location (via search or pin) and those that expected the Driver to arrive at their current location.

The Discovery

Rider expectations changed over time.

I was surprised by the issues we found. They felt like privileged San Francisco annoyances, rather than major problems faced by our global audience. But after some thinking, it became clearer that Riders expected the experience to just work with minimal effort. As Uber became more integral to their lives, their expectations evolved.

“Curiosity revealed an opportunity to perfect the pickup experience for everyone, everywhere.”

If power users with great reception, powerful phones and tech literacy were having trouble in our most mature marketplace, how bad was the pickup experience in our immature marketplaces with more challenging technological and environmental contexts? Curiosity revealed an opportunity to perfect the pickup experience for everyone, everywhere. This was the beginnings of a working north star.

Deeper Insights

Working backwards from perfect.

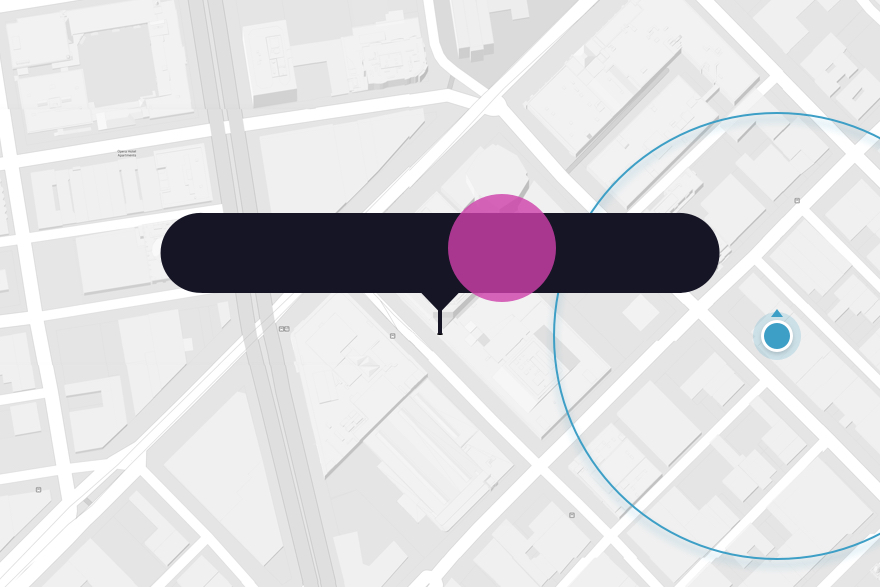

Before I could jump into designing, it was important to define success and understand the health of the pickup experience at scale.

Prior to the redesign, contact rate i.e the rate at which a phone call occurs during the pickup was the only proxy we had used to measure pickup quality.

I unpacked the concept of the perfect pickup and modeled for the dimensions of time, space and anxiety.

I partnered with our data scientist and used this framework to investigate the pickup health around the world.

Most pickups require additional physical or coordination effort

Digging into the data revealed some big insights into the pickup experience. Almost all trips involved some extra coordination effort such as a phone call to clarify the location and additional physical effort such as walking somewhere else to meet the driver, or the driver re-circling the block. This data showed that the experience was hardly the door-to-door magic Uber had been optimized for.

“In a city as busy as San Francisco, over $1 million was wasted per week because of problematic pickups.”

The time and energy spent recovering during problematic pickup situations was having a material impact on the business bottom line. Waiting time translates directly into network under-utilization and every phone call costs to anonymize.

In a city like San Francisco, over $1 million was wasted per week because of problematic pickups. Cities like Guangzhou and New Delhi were much worse.

I have intentionally omitted confidential data here.

No pickup specified

A large majority of Riders don’t explicitly set their pickup location. They rely on the default device location of the app. Half of all sessions are at least 100m inaccurate.

Requested location is often not the pickup

Only a small percentage of trips start within 20m of requested location. Where the Driver is sent and where the Rider is actually picked up is mismatched.

GPS updates ignored

A large number of sessions have an improved GPS accuracy by the time of request. Many of these sessions improve over 1000m in accuracy.

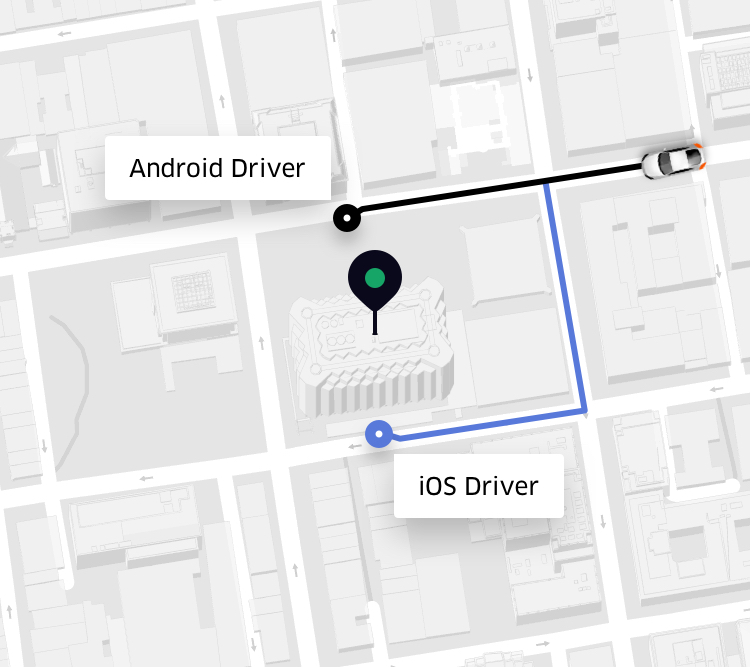

Some pickups just don’t make sense

Many trips are requested from within buildings. This can result in different pickup locations, depending on the operating system of the Driver.

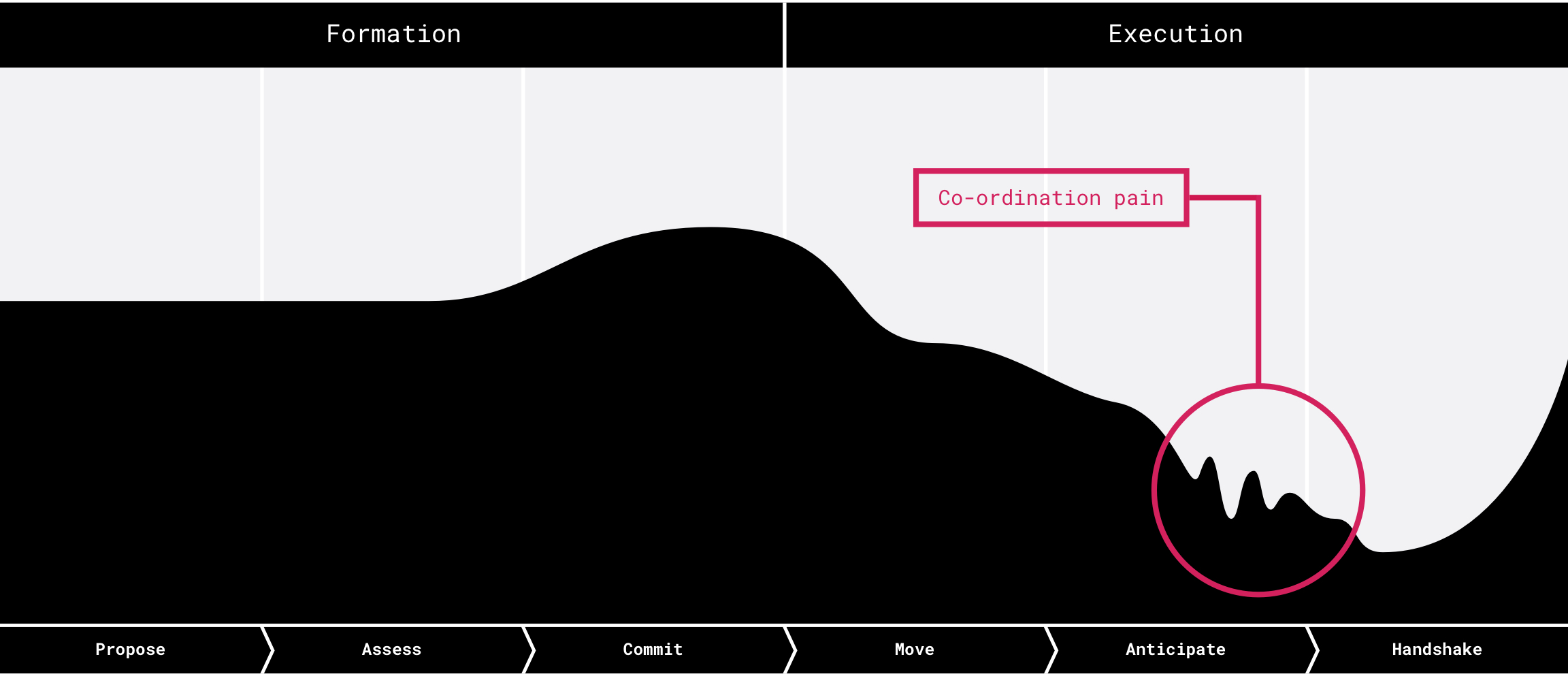

Reframing the Problem

Poorly formed rendezvous plans cause downstream pickup problems.

The Rider app exacerbates the formation of problematic pickup plans between Riders and Drivers. Problematic pickup plans consist of inaccurate locations, ambiguous information and inefficient routes which causes confusion. Ancillary communication and additional physical effort is required from Riders and Drivers to recover, which leads to frustration and wasted time.

“...how might we help Riders and Drivers form a better pickup plan?”

This begged the question, how might we help Riders and Drivers form a better pickup plan? Our proposal was Rendezvous , a pickup plan created on behalf of Riders and Drivers.

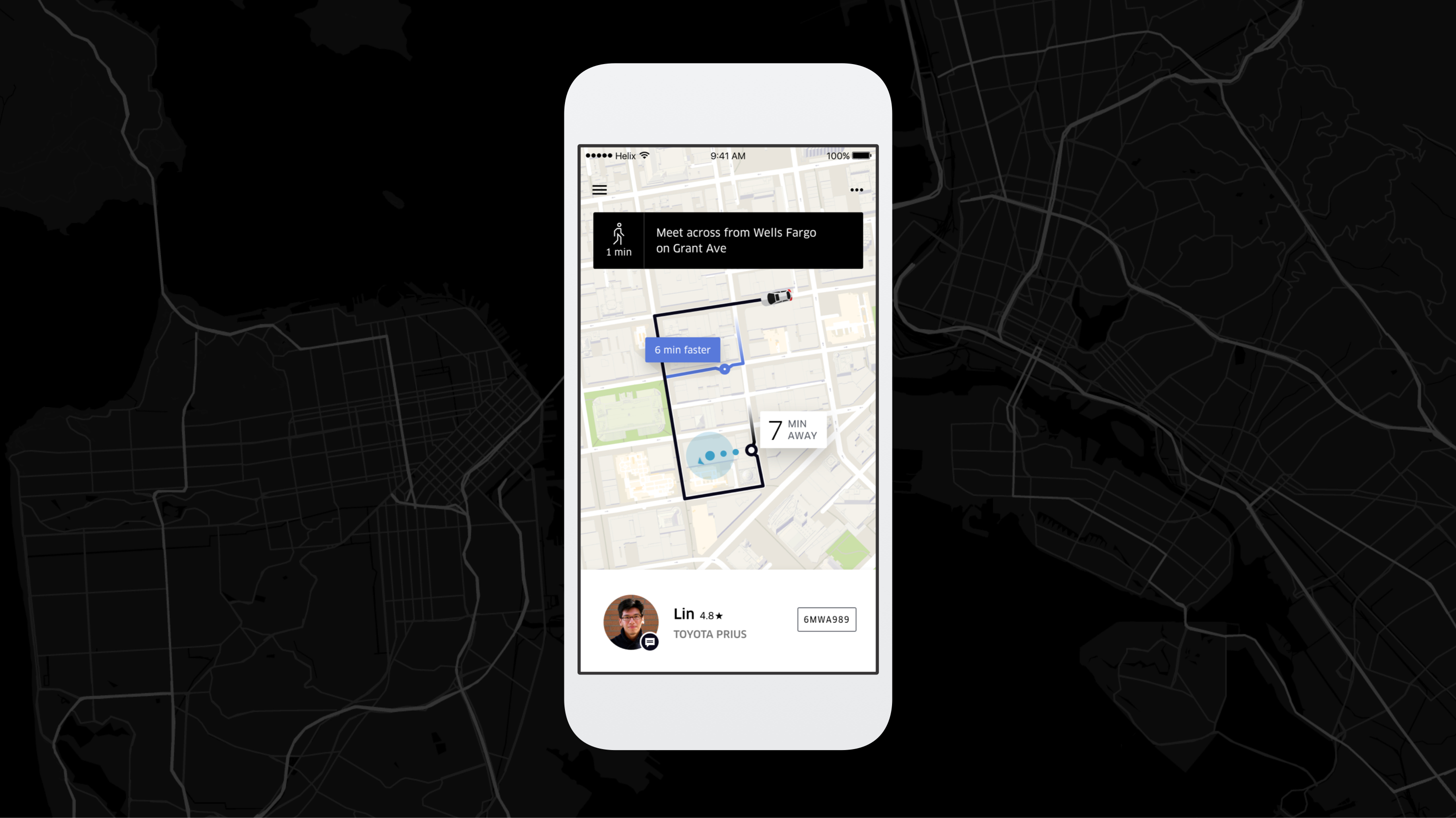

The Pickup Redesign

Introducing rendezvous.

In an age where everything is demanding your time, Uber gives your time back by making pickups fast, effortless and calm. Uber makes sensible decisions for you erring on the side of protection— informing you in ways that are understandable and actionable.

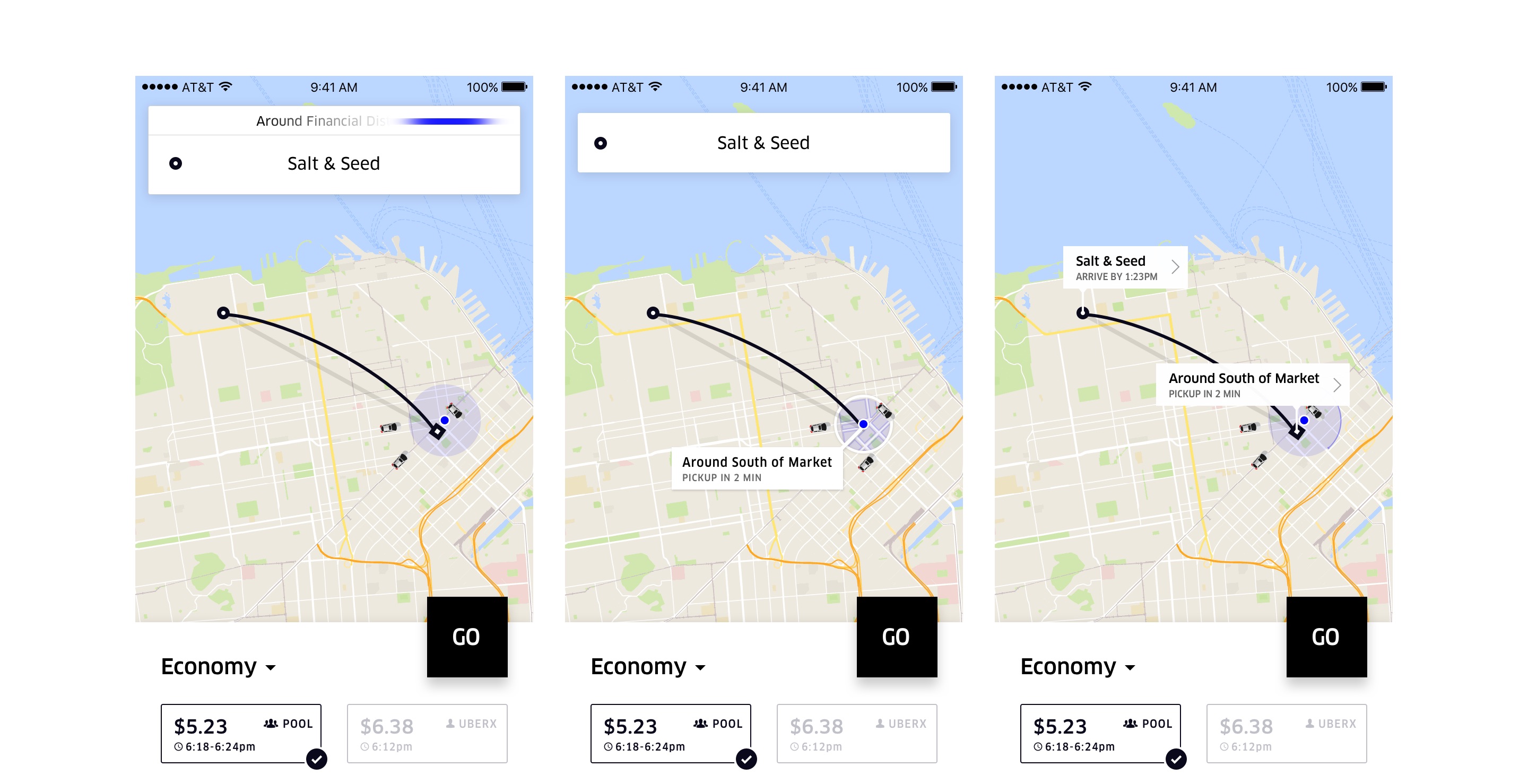

Just request and we do the rest

Uber finds you the optimal meeting place based on who you are, where you are and where you’re going. Uber saves you time without you needing to select a pickup.

People-friendly walking instructions help you better understand and identify your meeting spot. No more nonsensical addresses.

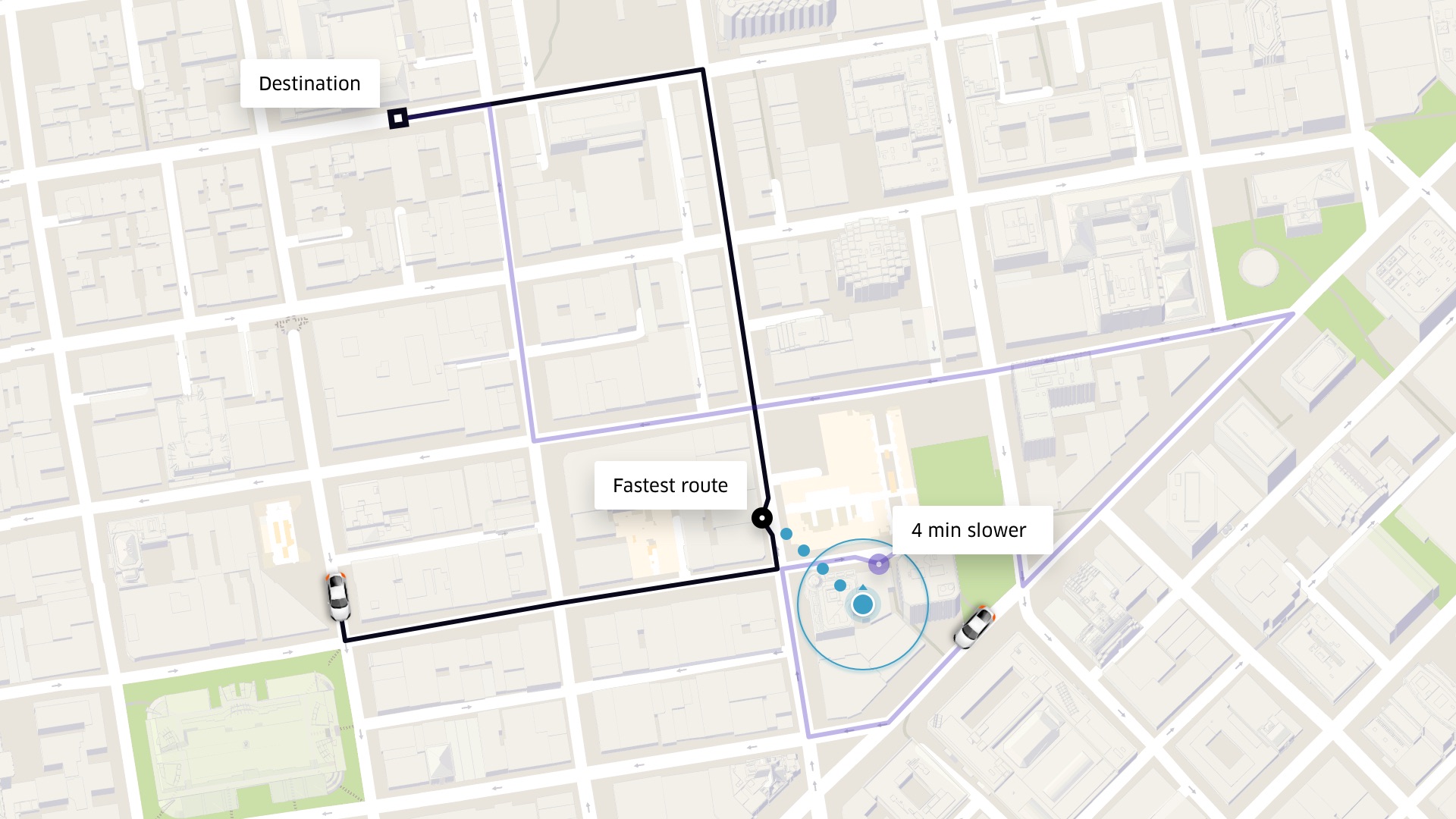

Always Moving forward and faster

Sometimes there’s a faster way, that requires walking. Uber understands these situations and gives you an option to save time.

We've got your back

When Uber isn’t sure about your current location, you’ll be prompted to help. Over time Uber will learn more about you and your city, so your Ride will always start in the right place.

Flexibility and the final say

Sometimes your situation requires precise control over where to get picked up. Uber gives you complete control when you need it.

How we got there

Perfect the pickup for everyone, everywhere.

Three primary questions informed my design strategy:

- How do you design for everyone, everywhere?

- What contexts need to be considered?

- What’s the perfect pickup?

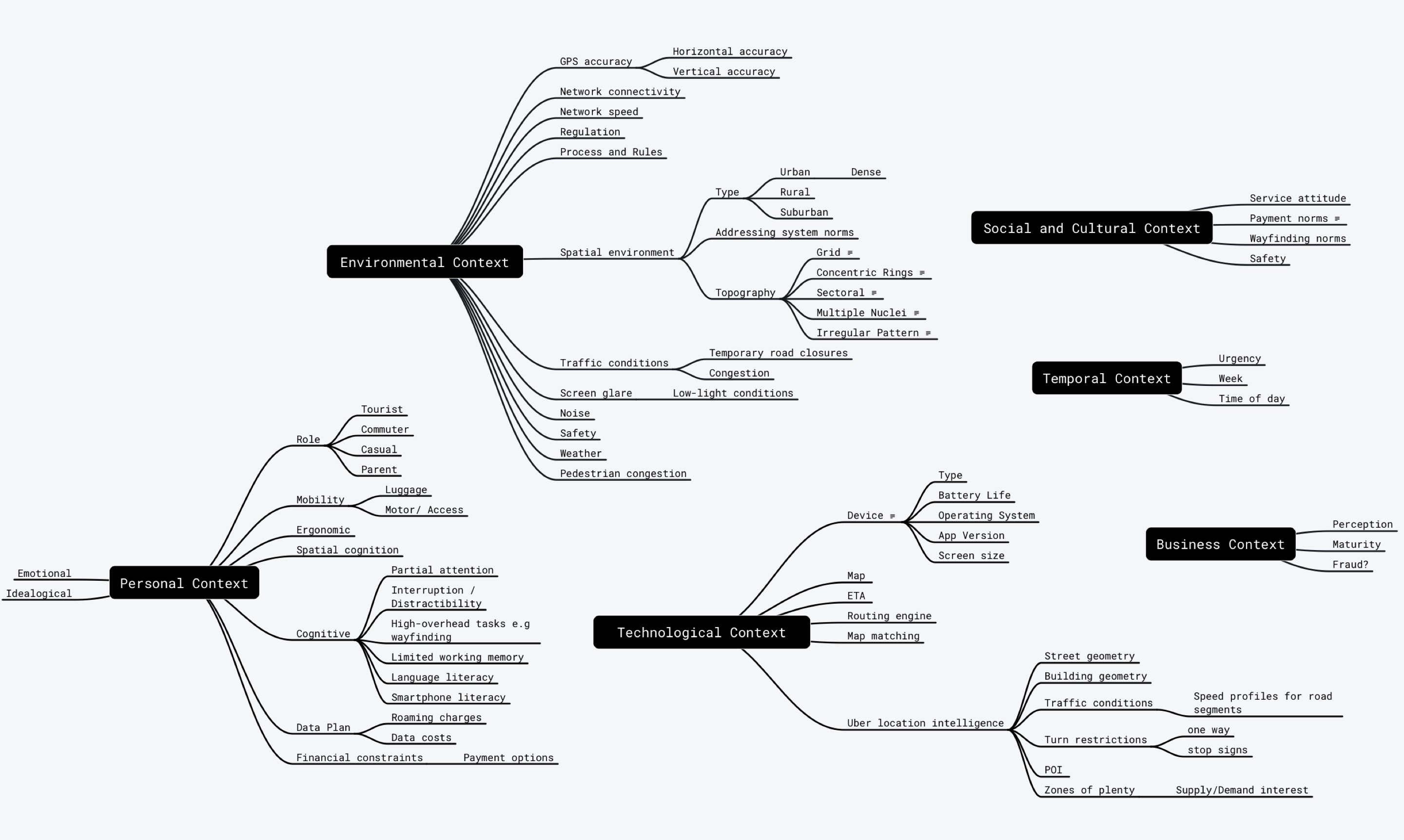

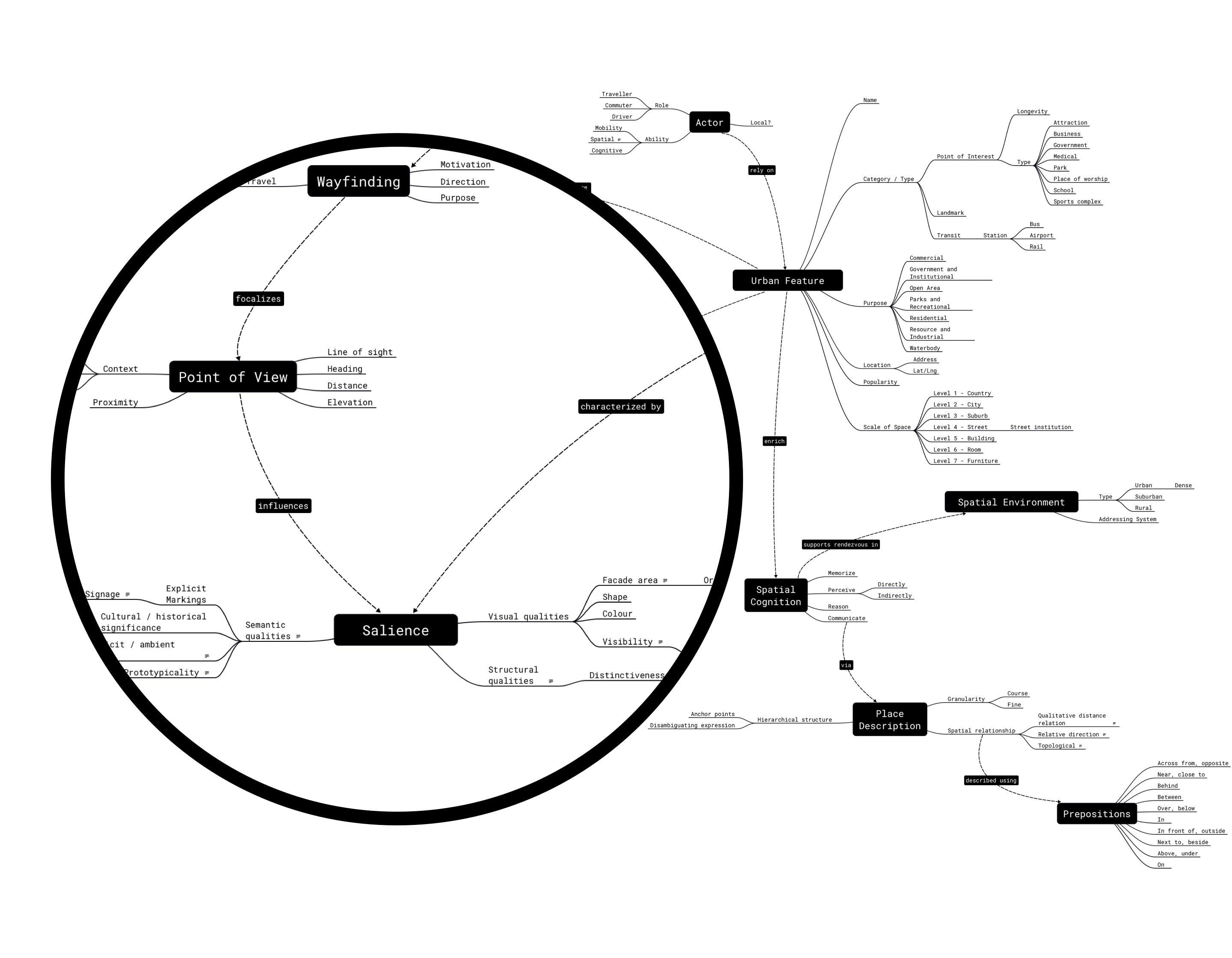

Early on, it was important to understand the different factors that may influence the Rider and Driver experience. I mapped all the possible concepts and translated this into the spectrums and situations framework.

A more inclusive design

The existing Uber app was poorly designed for users who weren’t reflections of people that work in the San Francisco Uber office. To move beyond the existing biases, I tried to educate the team with an approach to designing for everyone, everywhere.

The spectrums attempt to highlight the range of temporary or permanent challenges to consider when a person is interacting with Uber.

The situations attempt to highlight situational challenges that everyone experiences. A situation is a temporary context that affects the way any person interacts with Uber for a short time.

“Historically, Uber poorly empathised for users who weren’t reflections of people that work in the SF office.”

This framing was used to destroy any stereotypes that the team had about people and marketplaces. The goal was to create design solutions that scale and extend to any combination of these contexts from the outset.

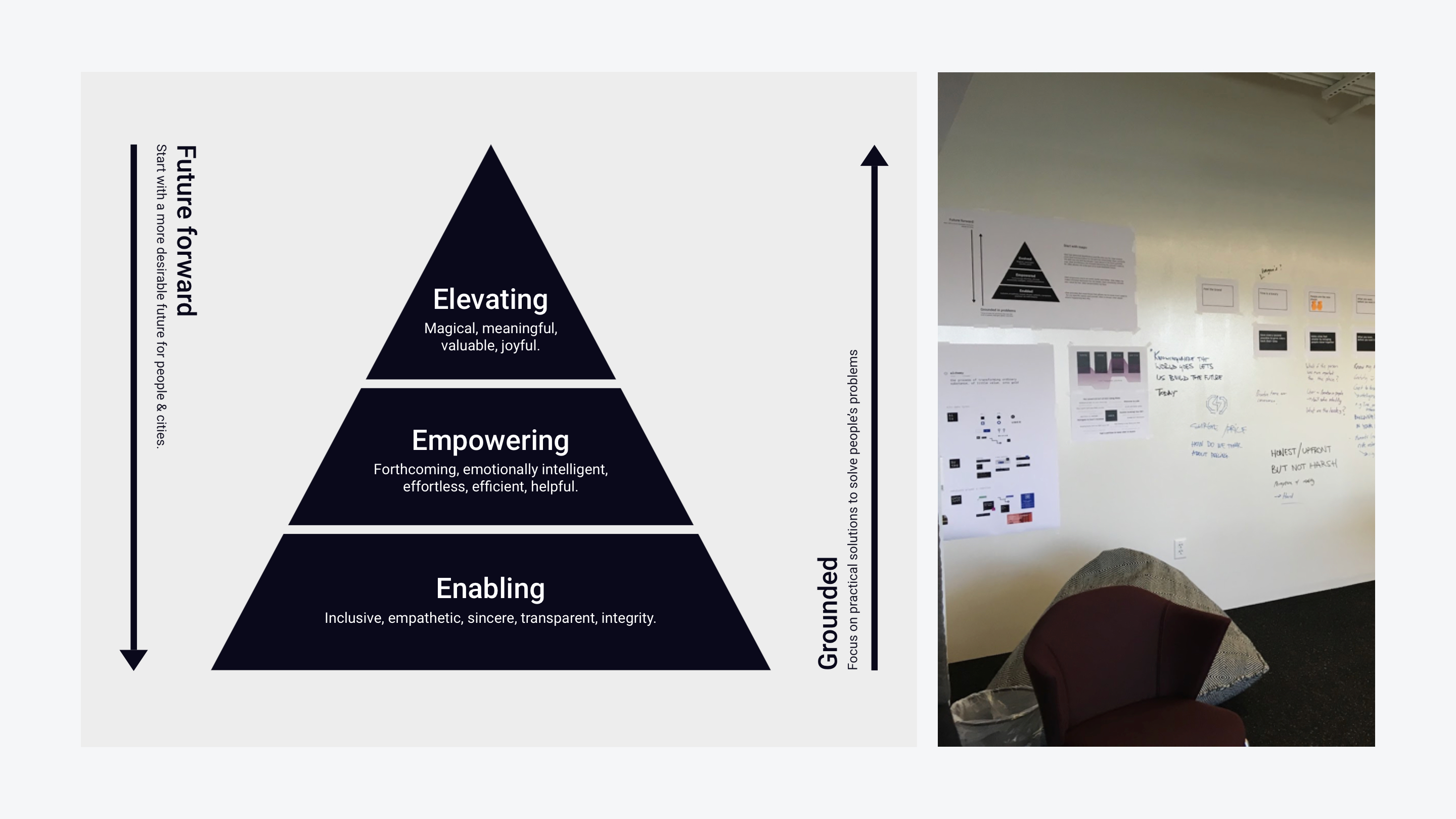

Degradation to adaptation

I created this additional hierarchy of needs framework to reframe our conversations about quality and features.

Instead of starting with a San Francisco-centric design and degrading for what the team deemed as the other challenging marketplaces we needed to start with a minimum bar of quality to enable rides for people in all contexts.

The framework helped shift from unproductive questions like “How is this going to degrade for Nairobi?” to “How might we enable a destination first design for cities without a traditional addressing system?”

Working Backwards from Perfect

I reversed the polarity of the imperfect pickup to jumpstart creativity. Four key design challenges emerged:

- How might we better understand where the Rider is?

- How might we form a pickup plan that minimizes effort and saves time?

- How might we remove the need for a map entirely?

- How might we better adapt to the dynamic nature of cities and human mistakes?

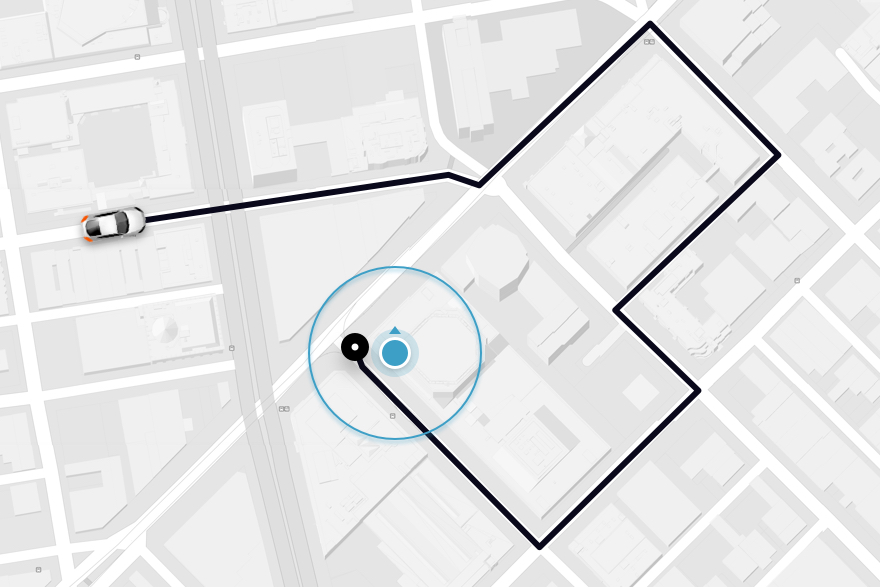

From Inaccurate to Precise

Better understanding where the rider is.

A major reason problematic pickups occurred were because getting an Uber relied heavily on the Rider explicitly setting a precise pickup location to meet. Not doing so, causes the Driver to be sent to the default device location, which half the time is wildly inaccurate.

Our data revealed that:

- 50% of Riders globally don't explicitly set a pickup location.

- Half of all sessions are at least 100m inaccurate.

- 45% of sessions have an improved GPS accuracy by the time of request. We do nothing with this information.

Based on these insights, I proposed two key feature ideas Destination First and Live Locations to help better understand where the Rider is. Central to the features, were these key ideas:

- Stop relying on the Rider setting their pickup location. Do the heavy lifting on behalf of the Rider.

- Carve out more time for the GPS to warm up.

- Capitalize on GPS updates for as long as possible.

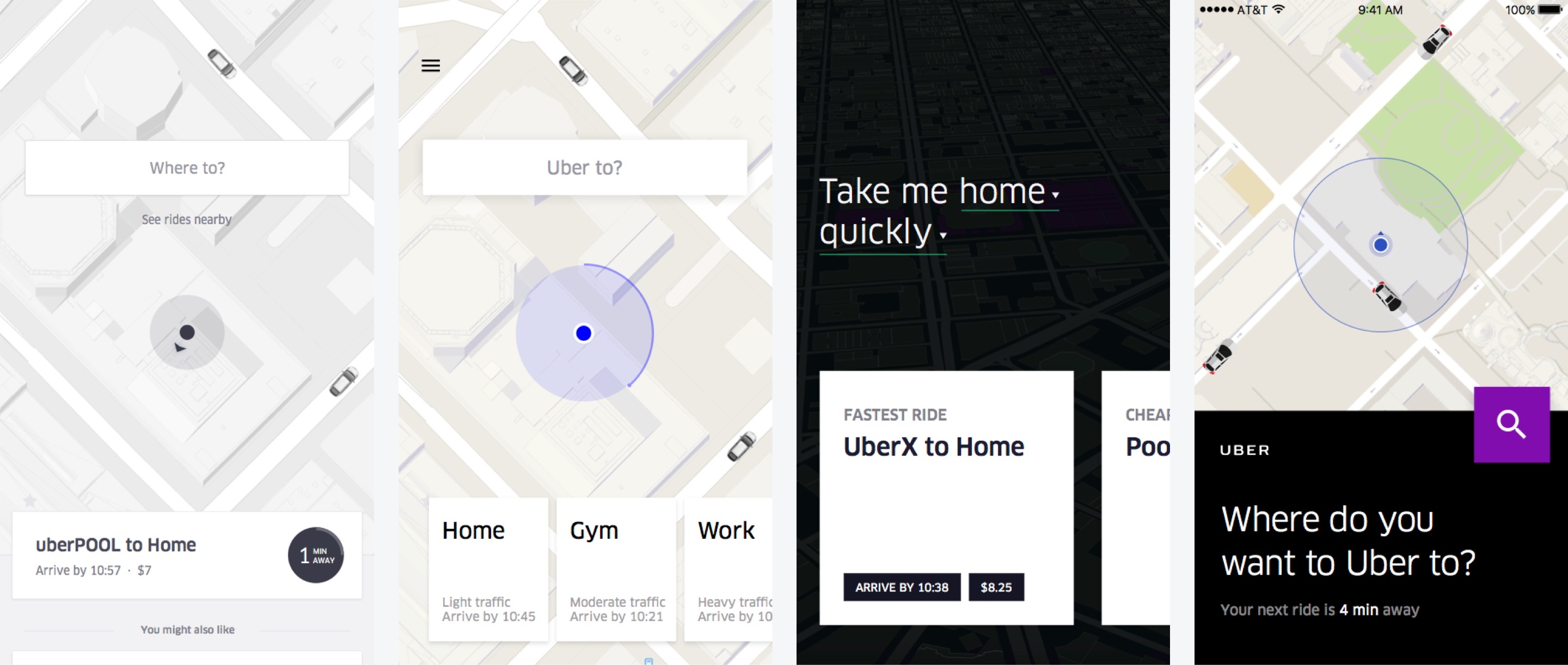

Starting at the end

In order to optimize the pickup experience, there was only one thing we needed to know—the Rider's destination.

Without much debate, the team agreed that asking “Where to?” upon app launch matched the mental model of the Rider. It was also useful in unlocking more advantages, such as providing the user with upfront fares, estimated arrival times and allowing more time for the device GPS to warm up to aid the pickup experience.

To compensate for the new speed bump, I designed the accelerators feature—a predictive set of shortcuts that gives the Rider 1-tap access to their most likely destinations at any given time.

De-risking the new flow

We feared that the new destination first experience would cause issues because it was more friction and a fundamentally different flow.

In order to de-risk some of our assumptions, we travelled to Bangalore, Delhi, Ahmedabad, Guangzhou and Shanghai to test an early prototype of the designs.

To our surprise, not a single participant noticed the different sequencing of the flow or had trouble with it. The destination accelerators resonated well with participants, confirming our intuition around designing for speed.

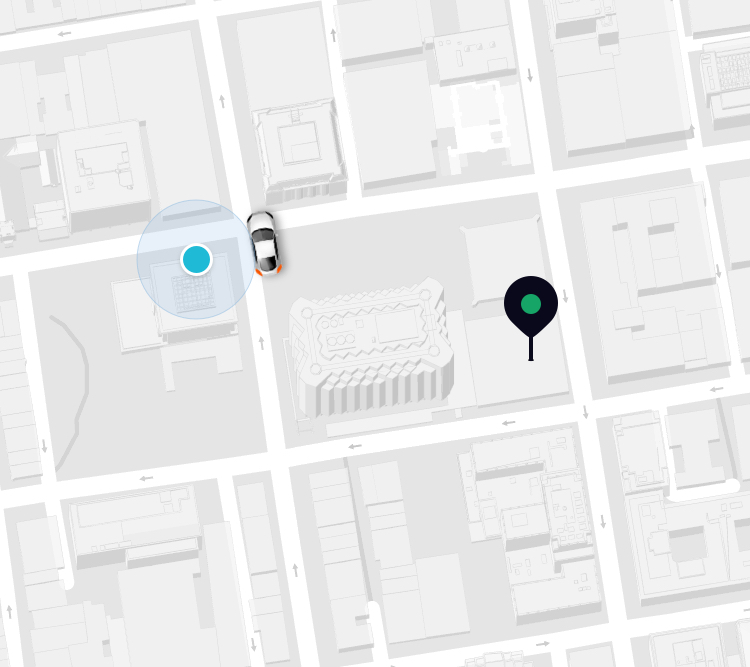

Live Locations

Live locations feature was born by questioning whether we needed to default to any pickup location at all.

Rather than lock on the Rider's location upon app launch (which roughly 12-15 seconds for an accurate fix), the app continues sensing, asynchronously updating as the GPS updates. The most accurate GPS location is obtained at the last possible moment—at the time of request.

This required a big design shift for the posture of the experience. The challenge was shifting from set your pickup to where and how do you want to go?

Inspiring confidence on the confirmation screen

If the new experience was to do the heavy lifting on behalf of the Rider, the confirmation screen needed to inspire confidence and show how the pickup experience was being taken care of.

A key design challenge was to consider how much emphasis should be given to this always sensing state.

The riskier design decisions I made was to obfuscate the pickup location entirely during the core app flow. The idea was to present the overview of the trip to persuade Riders to focus on selecting how they wanted to get there, rather on where to get picked up— since Uber would take care of that.

This meant the UI needed to inspire confidence for the majority, and those who wanted to assert control needed to know how to discover the feature. It also meant that when we couldn’t optimize on the users behalf, we needed to occasionally ask the user for help.

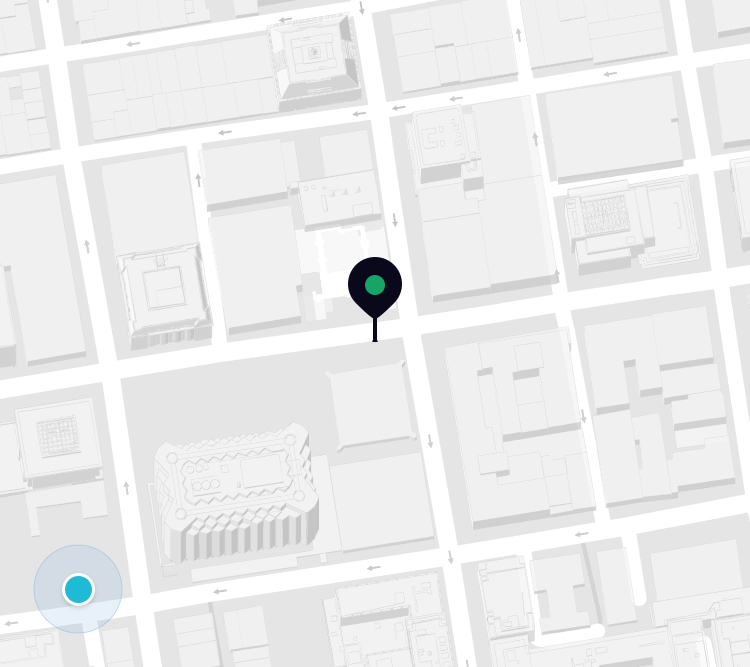

Over-designing for anxiety

The goal of these designs were to reveal the accuracy of the GPS location as it resolved. I assumed that transparency was the key to building Rider trust. After testing many iterations of this experience, we repeatedly observed that:

- Ambiguity and resolution concepts were mostly missed.

- Riders assumed that the app knew their current location and didn’t actively look to confirm.

Riders were not anxious or thinking about the GPS accuracy at all. My anxiety, further compounded by stakeholder feedback was being reflected in my designs. The GPS dot and location tooltips were loaded with this anxiety and I felt like I had exhausted all possibilities.

After the third round of poor testing, I killed the idea in favor of a more simplified and balanced interface that reflected what Riders were focussed on.

From Inefficient to Optimized / Immutable to Fluid

Giving riders and drivers back their time.

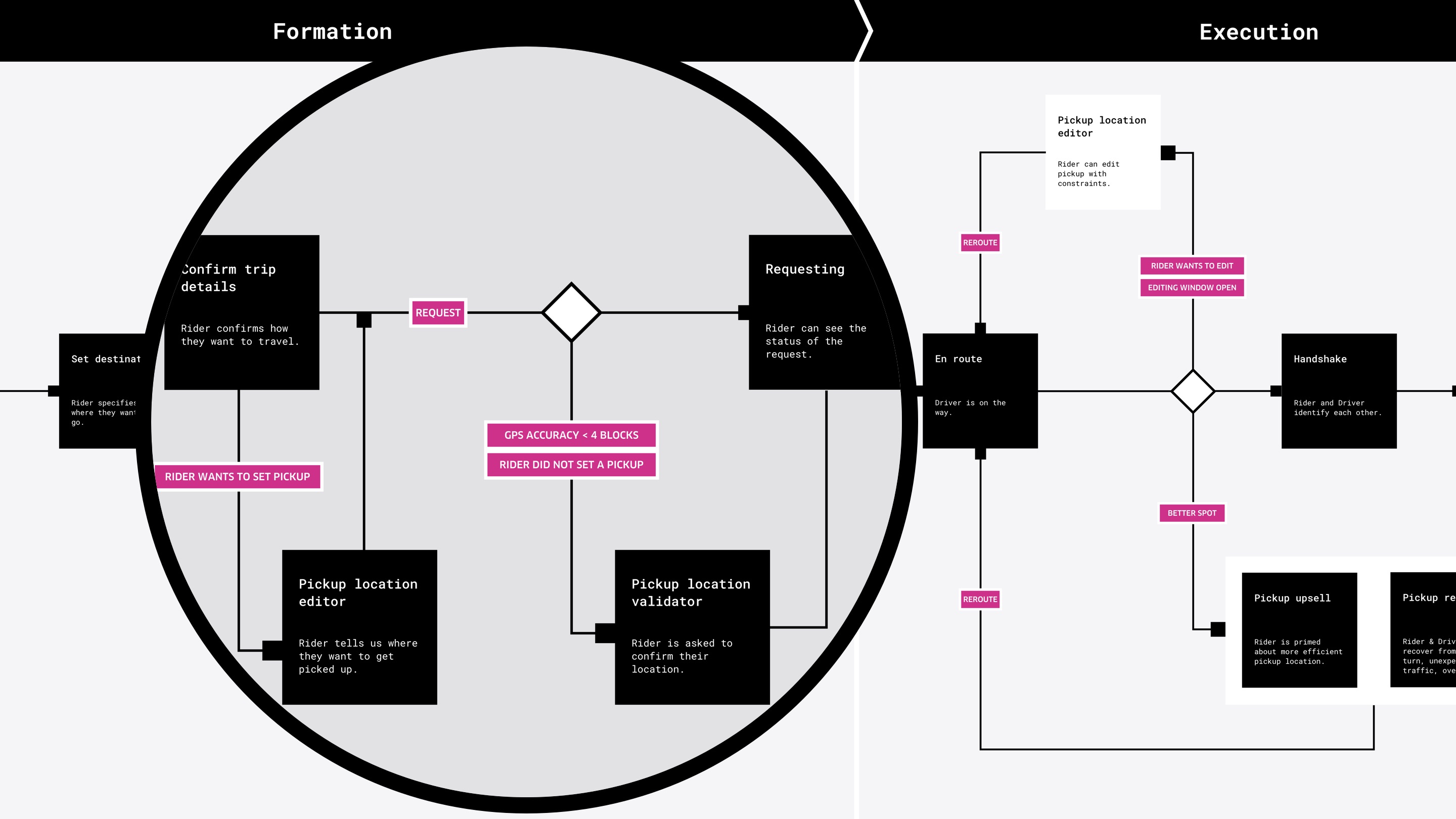

Knowing the Rider’s destination and the most accurate understanding of their location allowed us to do the heavy lifting and select the most optimal pickup location. The system needed to be smart enough to just work when it could, and humble enough to intervene when it couldn't. This system called adaptation was by far the most complex problem of this project.

Foundational to the adaptation framework were these concepts:

- A confidence score would determine whether to choose a spot on behalf of the user, or to disambiguate their location. How we calculated this confidence score would be an ongoing project to improve.

- We needed to respect Rider control and agency. Design patterns needed to allow for opting in, opting out or taking complete control.

- The system needed to be flexible enough to learn about Rider willingness. Don't design based on the assumption we will know the right answer.

Intelligent pickups

Making trips efficient required that we move beyond dispatching the closest car, to dispatching the most optimal* car. This presented several design challenges:

- Getting the Rider to walk to a nearby pickup location.

- Creating heuristics to decide the optimal spot.

- Adapting when we don’t know where the Rider is.

- Balancing smart defaults with choice and control.

*Optimal refers to the car with the fastest route to destination based on a set of nearby candidate pickup locations

Adaptation - a flexible architecture

I designed the flow based on the idea of a location confidence score. If Uber is confident of the Rider's location, it does all the heavy lifting. Otherwise, the app prompts the Rider to validate their location.

Instead of designing for the right answer, I designed a flexible system optimized for learning and optionality.

From Ambiguous to Obvious

Communicating location in a more intuitive way.

A critical part of the rendezvous experience is that Riders and Drivers have a clear understanding of where to meet and how to get there. The existing Uber app didn’t do a good job of supporting wayfinding, relying mostly on street addresses and the map.

During our research trip in India, we observed many wayfinding challenges. Limited street signage, intense traffic on the roads and sidewalks and poor GPS accuracy meant that the Riders and Drivers used POIs to coordinate their pickup location (in spite of what was formed in the app).

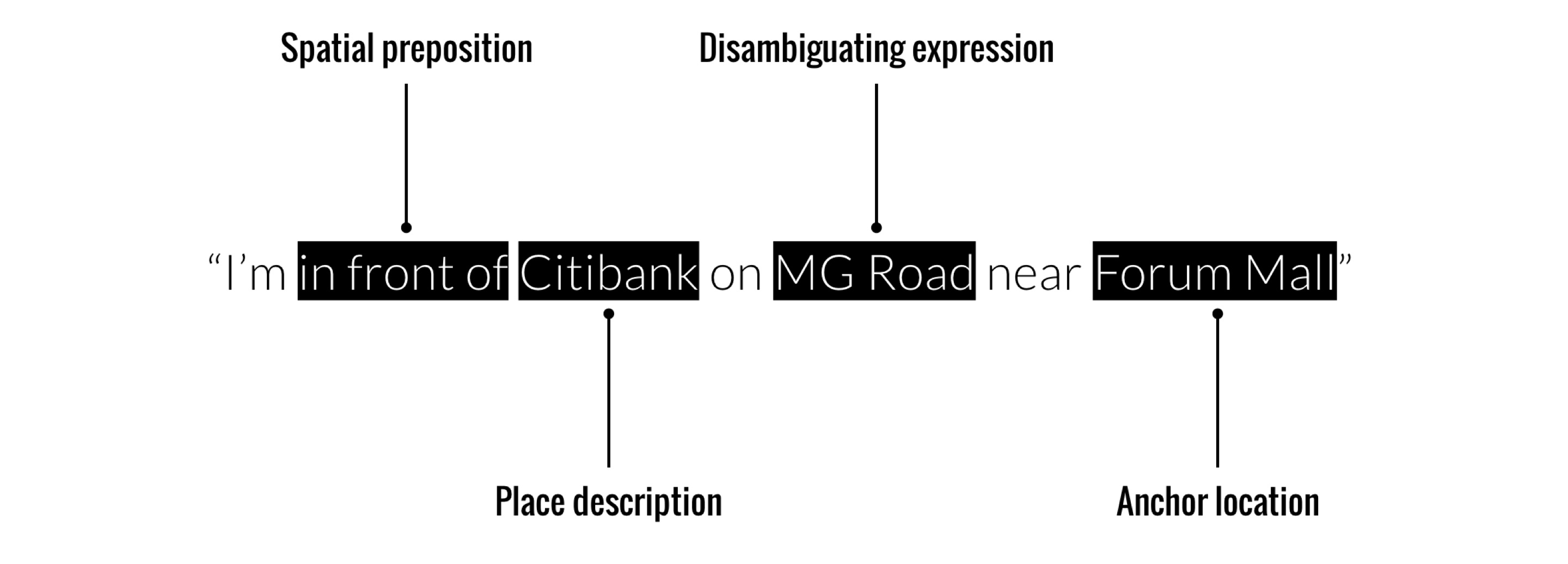

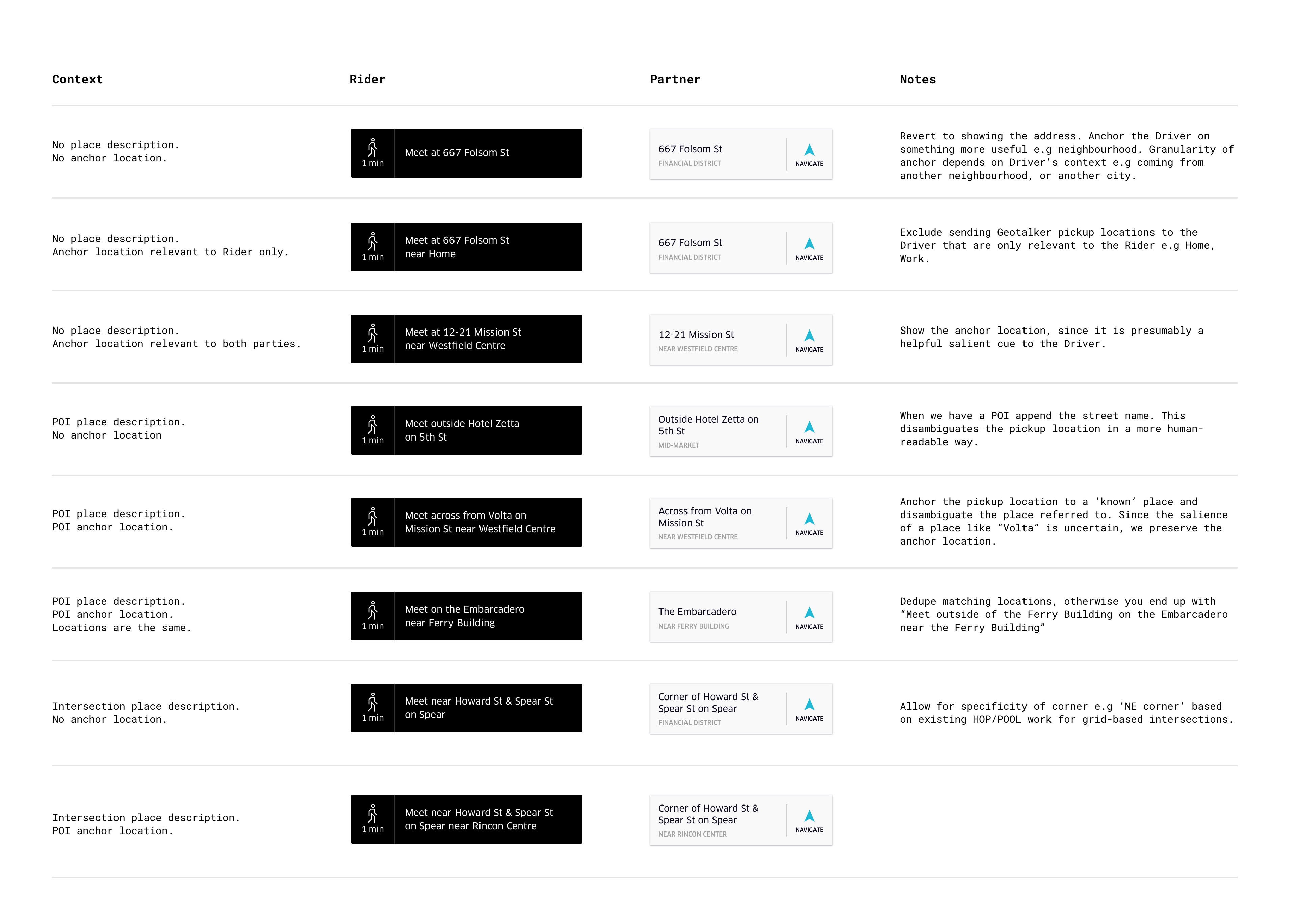

We found that there were structural patterns inherent in their communication, which inspired the Geotalker feature.

Geotalker is a place description framework that mirrors how the human mind organizes spatial knowledge. It works by using a set of heuristics to translate a reverse geocoded street address into a place description phrase to support wayfinding, spatial awareness and communication.

I started out by creating a concept model for wayfinding and spatial cognition. The exercise helped me come up with the idea that features of the urban environment could have different levels of salience, depending on the point of view of the Rider or Driver.

The larger vision was to create a system where place description leveraged the POI with the highest level of salience, based primarily on heading direction and other factors. The system would test different labels and self-optimize based on the quality of the pickup experience.

However, given the speculative nature of the idea and reliance on a quality location data set, we decided to experiment with a less intelligent version in the existing app.

Geotalker reduced ambiguity in the pickup experience

Early experiments resulted in significant decreases in the distance between pickup request location and actual pickup location and contact rate. We concluded that Geotalker helped to reduce ambiguity of the pickup location.

This was enough signal necessary to launch the idea in the redesign.

The Most Radical Update Since 2012

In the 5 months after my involvement on the project, the team continued to evolve and polish the visual design, as well as finesse the finer functional details as the app was being built. Although I was not part of this process, it was great to see most of my work brought to life.

On November 2nd, 2016 the new Rider app launched globally—an impressive achievement by the team, considering that it was a complete redesign and rebuild from scratch.

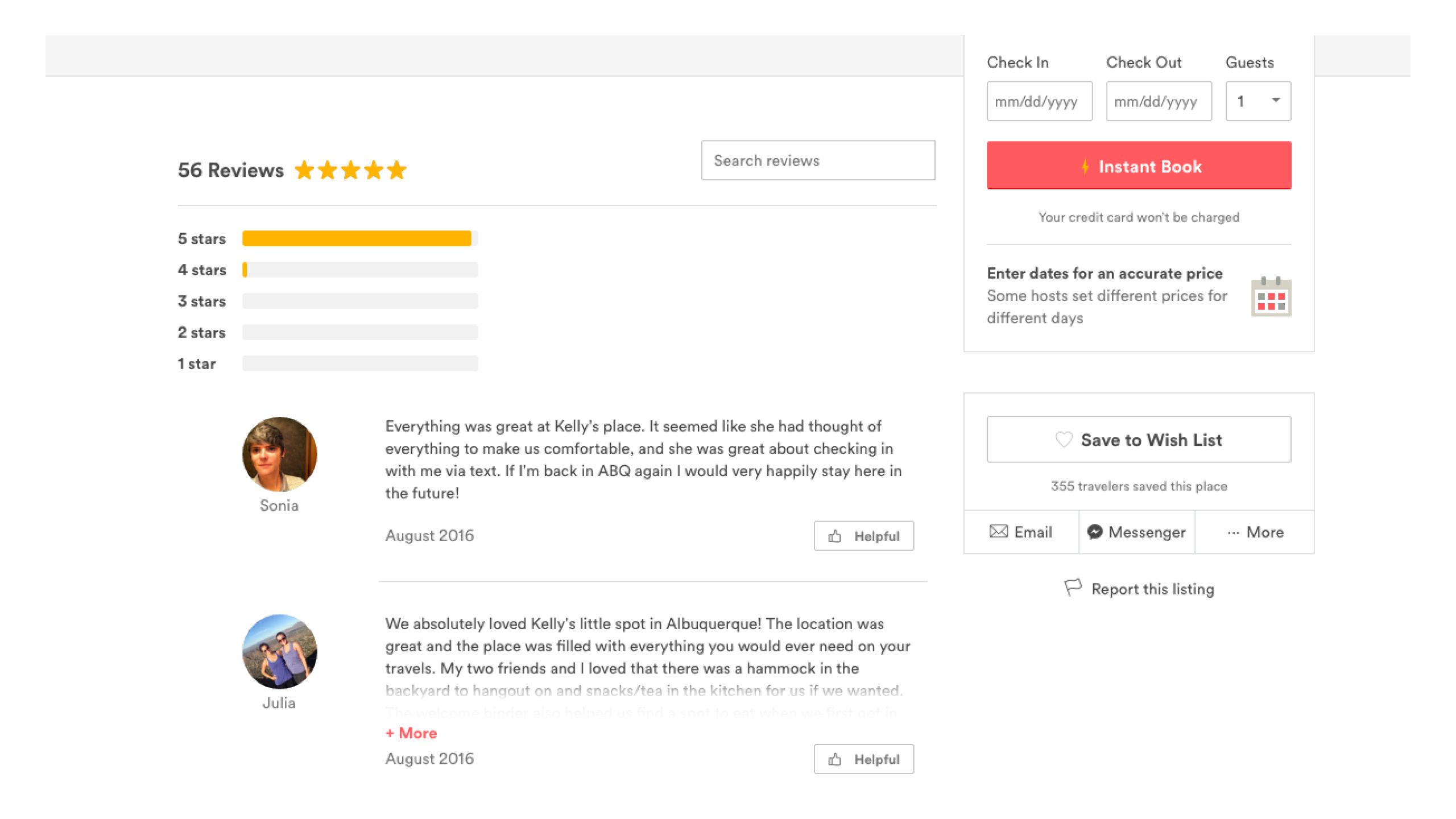

Positive results and much more to do

The redesign of the Uber Rider app on iOS and Android has had a positive impact on the pickup experience, at the time of writing (3 months since launch). However, contact rate has not been significantly decreased which means Riders and Drivers continue to contact each other to confirm or coordinate pickup details. I believe this to be a behavior change that will reveal over a longer period of time.

The error distance between requested pickup location and actual pickup location decreased by 34%

Driver wait-time decreased by 20%, high-precision pickup rates increased by 17%, multi-contact rate decreased by 3%.

For confidentiality reasons I have omitted the actual values for these metrics.

Was this case study helpful?

Feel free to show your support by buying me a coffee.

Uber Brand Case Study

A tech startup turned global mobility platform in eight short years deserves a holistic brand system that’s instantly recognizable, works around the world, and is efficient to execute. Here’s a case study looking at the 2018 Uber rebrand.

About Uber Brand Case Study

- Category : Web Design

- Colors : Color Code #eeeeee Color Code #444422 Color Code #888844 Color Code #222222 Color Code #66cccc Color Code #cccccc Color Code #aaaaaa Color Code #000000

- ← Pesce

- Fully Studios →

How Uber Disrupted An Industry With An Explosive Approach

Table of contents.

In this strategy study, we’re going to delve into a company that impacted everything from people’s everyday lives and entrepreneurial dreams to the startup world and city legislature.

Its story and strategy are fascinating, often problematic, and definitely worth exploring. So let’s embark on a different kind of Uber ride.

Despite disrupting transport around the globe, Uber defines itself as a technology company , not a transport company - hence their legal name Uber Technologies Inc. It was one of the first companies to embrace and define “the sharing economy” concept and created a two-sided digital marketplace for drivers and riders.

Uber’s mission was to make transportation as easy to access as running water and they wanted to do it in a different way - without owning its own vehicle fleet like your regular taxi company.

That asset-light strategy is what makes Uber so incredibly scalable and it proved to be a huge draw for investors. Since Uber’s launch in 2010, the company has attracted over $25 billion in VC funding.

Their business model and immense financial backing helped Uber achieve:

- Present in 10,500+ cities across 70 countries

- 131 million monthly active platform customers

- Nearly 23 million rides per day worldwide

- Over 5 million drivers worldwide

- 118 million users in 2021

- Annual revenue of $17.4 billion in 2021

- A 68% share of the US rideshare market .

Uber’s numbers are astronomical and the company is a perfect example of a disruptive and transformative brand. However, as we dive deeper into Uber’s strategy, you’ll see that Uber faced and is still facing many challenges - the biggest one among them being its (un)profitability.

But let us start at the very beginning...

{{cta('eed3a6a3-0c12-4c96-9964-ac5329a94a27')}}

It all began on a cold night in Paris...

It was a snowy winter night in Paris in 2008. Two friends and successful startup founders, Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp, were attending the annual tech conference LeWeb. More importantly, they were trying to get a cab but couldn’t find one.

What if you could just request a ride from your phone?

This idea, based on a very real need at that moment, is what sparked the creation of Uber.

After the conference, the entrepreneurs went their separate ways, but when Camp returned to San Francisco, he continued to be fixated on the idea and bought the domain name UberCab.com.

In 2009, Camp was still CEO of StumbleUpon, but he began working on a prototype of UberCab as a side project. At the time, UberCab was still an idea for a shared luxury cab service that could be ordered via an app.

Camp had managed to persuade Kalanick to join UberCab in an advisory role and on July 5, 2010, the first Uber rider requested a trip across San Francisco. Kalanick became Uber’s CEO in December 2010, while Ryan Graves, Uber’s first CEO, assumed the role of the COO and board member.

Uber’s app, enabled its users to order a ride with a tap of a button . A GPS identified the rider’s location, and the cost was automatically charged to the card on the user account. Uber’s simplicity fueled its early popularity among users as well as investors and the startup quickly became one of the hottest companies in San Francisco.

By October 2010, the company received its first major funding of $1.25 million and in 2011 its growth skyrocketed. Early in the year, the company raised $11 million and went on to expand to New York, Seattle, Boston, Chicago, Washington D.C. as well as abroad in Paris.

Yes, just a year after the first Uber ride was requested, Uber had already launched internationally in Paris, where the idea for Uber first took root.

In December at the 2011 LeWeb Conference, the very conference “responsible for Uber’s inception”, Kalanick announced that Uber raised another $32 million in Series B and that investors like Jeff Bezos and Goldman Sachs got on board.

In 2012, Uber launched its arguably most popular service UberX. UberX provided an option of ordering a more affordable car as an alternative to its original black car service. That’s when Uber became really appealing to the mass market.

Behind Uber’s explosive growth are an innovative business model and growth strategy that we must explore before diving into Uber’s global expansion.

Key takeaway #1: build solutions for real-world problems

Successful products and services identify real problems and figure out how technology can be leveraged to solve them. Uber’s founders made sure they’re going to be able to get a ride during a cold winter night by using mobile technology to transform on-demand transportation.

All about Uber’s scalable business model

When talking about Uber’s business model, we need to mention that since its launch, Uber has expanded and diversified its services. It’s no longer just a ride-hailing service - it also offers food delivery (Uber Eats) and trucking (Uber Freight).

However, for the sake of simplicity, we’ll mostly focus on Uber's core business of ridesharing and the business model revolving around it.

The basic idea behind Uber is to connect riders that need to get somewhere with drivers that are willing to take them there. Riders create the demand while drivers provide the “supply” and Uber acts as the marketplace where both parties can seamlessly connect.

As you can see, Uber has two key users and it has to provide strong value propositions for both drivers and passengers in order to attract enough users for the platform to function as intended.

Let’s see why passengers and drivers use Uber.

Uber’s value propositions

- Convenient on-demand ride bookings

- Real-time tracking

- Cheaper rates compared to taxis

- Accurate estimated time of arrival

- Automatic credit card rides

- Lower wait time for a ride

- Upfront pricing

- Multiple ride options

For drivers

- Highly flexible source of income for people who own (or are willing to loan) a car

- Completely flexible working hours

- Good trip allocation

- Assistance in getting vehicle loans

- Weekly or even daily payments

Uber’s target market

While the appeal of Uber is quite obvious, who exactly do they target?

As evident from the value propositions, Uber has two main target segments - passengers who want a fuss-free experience ride from A to B and drivers that want flexibility and some extra income, usually on the side.

When it comes to passengers, Uber’s website’s headline for a long time was: Everyone’s private driver . That instantly lets us know that Uber’s target market is very, very wide. It’s everyone who needs a ride .

While targeting several customer segments with different cost-conscious and more luxurious service options, what’s perhaps more important is how Uber reached its audience at the very beginning as you can’t just target everyone from the get-go.

It’s all about passionate early adopters

Uber did a masterful job attracting its first users - passengers as well as drivers. When it comes to launching a marketplace the first few weeks are absolutely crucial as there needs to be enough supply and demand for service to feel worthwhile.

Uber developed a highly targeted and localized early adopter strategy in the Silicon Valley area. They knew that launching there meant that the company will be interacting regularly with the tech community who are continually looking for new tools and services that improve their quality of life. People there were ideal early adopters and Uber reached them by sponsoring tech events, providing free rides, and in general driving awareness among this audience.

San Francisco also has notoriously spotty cab service which was perfect for Uber. As early adopters, completely fed up with the taxi situation in the city, tried Uber, they took to blogs, social media and every other way possible to tell their friends about this new way to ride.

The Uber experience became a vector for growth as early adopters impressed their friends with the ability to call a black car from their phone with a couple of taps. These new riders were immediately wowed by the experience and became new users and advocates within the span of a single car ride.

Uber also knew that attendees of their sponsored events were well connected and highly likely to share their experiences with friends, tech press, and social media audiences after trying Uber.

By seeding this audience, they were able to create a growth engine that hinged not just on word of mouth, but by showcasing the service to one's friends which quickly led to a growing network of passionate customers.

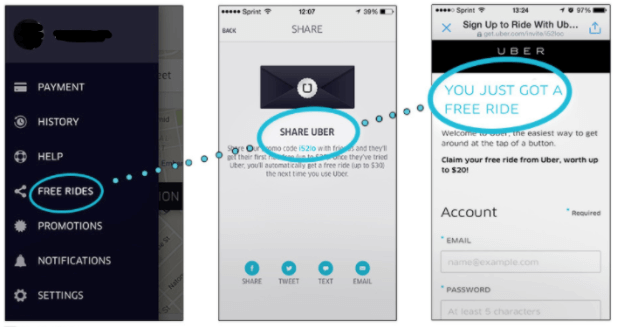

Uber combined that initial campaign with its referral marketing strategy where users can give friends free rides while earning credits themselves. This “give money-get money” program gave first-timers a more concrete reason to try the service. It’s been massively successful both for Uber and for certain “superfans”, one of whom earned over $50,000 in referral credits . Drivers also get referral incentives, thereby making acquisition on both driver and rider sides faster and easier.

That’s how Uber quickly got a lot of passionate users who were actually Uber’s first target market. Of course, every company wants passionate users, but as you’ll see, Uber needed them to win against the myriad taxi regulations in major cities.

Uber’s early adopters were people that weren’t happy with the existing state of the transportation industry in their cities. They quickly became advocates for the company in various forums as Uber fought against old regulations. It was a very clever move to identify and cultivate these customers early on. By making customer convenience and service a priority, Uber took the role of “disruptor” and turned it into a part of the company’s image and brand. They joined a broader socioeconomic movement towards changing old industries in ways that benefited consumers.

It’s safe to say that if Uber wasn’t backed by its passionate users, it wouldn’t be able to expand nearly as fast as it did. In fact, the disruptive socioeconomic movement became a key part of Uber’s early business model.

Adapting to local markets

Despite targeting everyone, Uber still takes into account local experience. As Uber expanded it segmented its audiences and precisely targeted them by region and immediate needs.

For example, in countries like India and Thailand, the average customer must deal with higher traffic congestion and reduced purchasing power than a North American city. In these regions, Uber expanded its offerings with a rickshaw and motorbike service, which are more affordable and often faster transport options.

What enables Uber to adapt its services to the local condition? It’s arguably the most important part of Uber’s business model and quick expansion...

An asset-light strategy

As we said Uber is not a transport company and therefore does not need the assets a traditional taxi company requires.

By being “just” an online platform connecting drivers with passengers via their smartphones eliminates Uber’s need to establish a brick and mortar presence in each new city to which it expands operations. This model eliminates many barriers to Uber’s growth and drastically increases its scalability. It also unlocks the potential for Uber to expand into contiguous service segments such as food delivery (Uber Eats) without drastic changes to the company’s operating model.

The majority of Uber drivers use their own cars which means that Uber doesn’t need to invest in a fleet of company-owned vehicles or the insurance and repair costs that come with it. It also doesn’t need dispatchers or call centers as the whole process of hailing a ride takes place on their app.

So, compared to a traditional cab company, Uber doesn’t have to deal with:

- servicing and maintaining a fleet of taxis,

- call center agents,

- administration,

- parking fees,

- recruiting and training drivers and issuing permits.

This means massive savings in fixed and variable costs as well as the agility to respond more quickly and effectively to market changes relative to its competitors.

That’s why Uber was able to expand extremely quickly and in a span of 10 years appeared all over the globe. No taxi or transport company is able to achieve that.

Their lack of assets shows how they save money and expand at relatively low costs - but how does Uber actually make money?

How does Uber make money?

You can probably guess that Uber’s ridesharing service makes money by taking a cut of each ride that happens through their platform. While this is correct, Uber’s revenue model consists of more than just trip commissions - even without taking into account its other services like Uber Eats and Uber Freight. Let’s take a look at other revenue streams their business model enables.

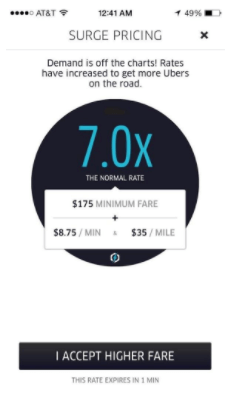

Trip commissions and surge pricing

Uber provides the drivers on its platform with a robust supply of ride requests to accept, fulfill, and make income. When passengers pay for the ride through the app, Uber takes their commission and transfers the rest to the driver. Uber claims that they charge their drivers a 25% fee on all fares, yet reports vary.

However, Uber’s trip rates are not always the same. Uber utilizes a surge pricing model , which is also a cornerstone of Uber’s business model.

It takes advantage of the dynamic relationship between supply and demand and willingness to pay. When there are more passengers than available drivers in a given area, the algorithm increases rates in order to equilibrate this discrepancy. The first benefit of this model is that it attracts drivers to areas offering higher rates, thus increasing their numbers in regions of high demand. Second, it narrows the initial pool of potential passengers based on how much they value a ride, allowing Uber to more accurately segment their customer base and satisfy those users who need their service the most.

Thus the surge pricing model serves the purpose of capturing the highest possible margins for the company and its drivers while establishing a targeted base of users that value Uber rides the most. These users might also be enticed to upgrade their chosen option to a premium one the next time they use Uber, which is considerably more profitable for the company.

Leasing to drivers

Uber runs a vehicle leasing program in many of its target countries to help new drivers get onboard faster. Drivers have to pay an upfront security deposit for the vehicle and payments are automatically deducted on a weekly basis from the driver’s earnings.

Advertising

There are millions of people around the world that interact with Uber cars every day. Not just the ones who use it for rides but also the ones who see them. That’s a huge opportunity for local as well as global brands that can take advantage of Uber’s on-car advertising .

Brands can advertise on cartop video screens, car wrappings, or car stickers. All three ways display ads on the car and are a fairly traditional form of advertisement, yet Uber with their huge number of drivers can get some money out of it. Of course, drivers that are willing to use their cars as moving ads also earn some additional income.

Understanding Uber’s business model is important if we want to understand the company’s extremely fast and aggressive global expansion, which is something Uber is quite famous for.

Key takeaway #2: plan for scalability

Building a scalable business model is critical, especially if the company’s revenue depends on the quantity of its service. Uber has built its platform in such a way that it is easy for it to expand to new markets and serve millions of users at the same time without a significant increase in its operational costs.

Uber expansion strategy

Uber’s initial global expansion it’s an amazing showcase of the company’s “ask for forgiveness instead of permission” approach . As we’ll see later, Uber’s culture has completely changed since then, but its early expansion is what brought the company mercurial success as well as plenty of backlash and issues of all kinds.

Uber employed an almost warlike mentality when going into a new market and the company’s sole focus was winning. This was first visible in San Francisco even before it went global.

Uber received a cease and desist order in San Francisco soon after its launch in 2010. It ignored it and issued the following response , that might be seen a bit on the arrogant side:

“UberCab is a first to market, cutting edge transportation technology and it must be recognized that the regulations from both city and state regulatory bodies have not been written with these innovations in mind. As such, we are happy to help educate the regulatory bodies on this new generation of technology and work closely with both agencies to ensure compliance and keep our service available for our truly Uber users and their drivers.

Our commitment is to facilitate an improved transportation option that provides safe, reliable, and convenient travel. That will not change. We will continue full speed ahead with the mission of making San Francisco city a great place to live and travel.”

They were relying on their passionate supporters and on their lobbying efforts to put things in order. Not just that, while this is playing out, they're continuing to push forward and expand into other parts of the world. That’s how aggressive they were from the get-go.

Going to Paris - because they can

Uber recognized early that international expansion should be a priority if the company wanted to achieve exponential growth and made Paris its 3rd launch city and 1st city outside the US.

In fact, when they launched in Paris, they launched as sort of a prototype, just to show that they can do it without too much difficulty.

As Mina Radhakrishnan, Uber’s first Head of Product said in a blog post :

“At Uber, we launched our first international city, Paris, in 30 days. There was a lot of manual work to continue launching in other countries and languages while we didn’t have a core set of international systems – we had to charge everyone in US dollars for several months. In parallel, we built out the foundations and kept moving pieces onto the new infrastructure, which allowed Uber to keep momentum and still scale.”

While Paris served as an enticing showcase for new investors it also made Uber realize they need an expansion playbook.

Uber’s unusual expansion playbook

At first Uber treated each city as an individual project. They would investigate what needed to be done on a case-by-case basis, and it involved a whole lot of work manpower.

However, there was a market that needed to be monopolized and they needed to act quickly.

Uber soon realized that looking at each city as a project was too slow. Instead, they developed a process based on the lessons learned from their initial projects and created their aggressive expansion playbook.

Here’s Uber’s plan when expanding to a new city:

- Secretly enter a new market. Recruit drivers and customers through company ambassadors who gain commission and Uber credit. Offer first-time customers free rides to create a strong customer and to exploit a legal loophole for promotion.

- Ignore threats of legal action. Make a case that customers want Uber to be there.

- Ignore government sting operations. When the government threatens Uber’s drivers with fines, reassure them that Uber will cover any penalties, legal costs or other repercussions using the massive sums of money invested in the company.

- Start lobbying the state government. Start pushing for regulations that legalize its operations. Create a positive public image and gain the support of influential local charities and other key community stakeholders. Involve customers in petitions.

- Monopolize the market. Hire more drivers, pour more money into promotion, and manufacture PR stunts like delivering puppies or ice cream.

- Undermine the competition. Recruit drivers from competitors by offering them high sign-up fees and often employ other tactics to disrupt their services.

This was the overarching process, and there is obviously a multitude of smaller processes within each of the six steps. The playbook was implemented by a new, local team with a separate entrepreneurial manager who was overseen by Kalanick, the CEO at the time.

While the process was extremely aggressive it’s also how Uber increased its valuation from $3.7 to $41.2 billion in just 15 months.

The main thing Uber did with this playbook was to launch its service seemingly out of the blue which gave the authorities no time to react before it was firmly established in the city.

While this playbook is responsible for Uber’s early success the approach was often challenged and frowned upon.

War on all fronts

Unsurprisingly Uber has been heavily criticized for aggressively lobbying, following unfair labor practices, jeopardizing the security of passengers and drivers, and playing with local laws by requiring no permits. There were too many scandals and issues to cover them all.

Uber’s warlike approach worked better in countries with legal systems based on common law. In common law countries like the US, Canada, and the UK, laws and regulations are more flexible and subject to judicial interpretation. Uber was therefore afforded greater latitude when arguing the legality of its case in the courts of law.

In the U.S., Uber used consumer enthusiasm for its service to bring pressure on local politicians to develop rules that allow it to operate. However, such an approach is difficult in civil law countries like China, France, Germany, Spain, and much of continental Europe.

This resulted in plenty of bans, penalties, and losses on various markets .

Uber has been banned from operating in parts of France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and Belgium. It has been accused of willfully ignoring and breaking the law, placing both drivers and riders in peril. In the Netherlands, the company had to pay around 2.3 million euros to settle a case, after being accused of operating an illegal taxi service from 2014 to 2015.

Uber also faced issues in countries where the relationship between Uber and its drivers meets the definition of the employer-employee relationship. This is one of the reasons why the app was temporarily banned from operating in Colombia and faced similar legal issues in Chile and Argentina.

Its presence in various countries has generated an incredible backlash – protests, riots, and clashes with angry labor unions - especially cab drivers.

Uber also completely mismanaged their launch in China and lost billions trying to establish themselves on the Chinese market. Here’s where their process completely failed them.

When Uber came to China, it didn't fully anticipate all the changes it would have to make. In China, besides having an established competitor in Didi, Google Maps didn't work, so Uber had to completely redo their location services.

Uber also relied on credit cards for payments, and in China, consumers increasingly used apps to do their payments. However, the main apps consumers used ( WeChat and Alipay), were owned by parent companies of the rival ridesharing company, so Uber had to essentially negotiate with its rivals in order to have consumers pay for their ridesharing services.

The Chinese policy regarding competition is also very different from the policy in the United States and much of Europe. The Chinese government wants to promote domestic firms and aggressive tactics are not really an option, because when push comes to shove, the government is likely to come down on the side of the domestic company.

Despite many problems and failures, Uber made impressive headway in foreign markets. But their success also made them a target. Well-funded local challengers soon replicated and improved upon Uber’s model and quickly limited Uber’s market share or pushed them out of their markets.

Tactical retreat from some markets

After Uber hired a new CEO in 2017 and started cleaning house at the end of 2017 (more on this later), it switched to a much less aggressive expansion strategy. In 2018 they decided to retreat from some markets instead of trying to “win at all costs”.

While some may see retreat as a failure, Uber’s early and aggressively sought international position actually provided an opportunity. Instead of completely giving up on markets, Uber used its leverage as an established player to acquire stakes in local competitors . Uber acquired 15.4% of Chinese Didi, 38% of Russia’s Yandex Taxi, and 23.2% of Southeast Asia’s Grab.

Uber also vowed to do a “reset” in Germany, where it operated a very limited service in Berlin.

Uber is still left fighting in India against rival Ola where the two have been locked in a costly battle for years over dominance in India’s ride-hailing market. The rivalry is more awkward now that both companies share a mutual large investor: SoftBank.

Uber’s early super aggressive expansion policies reflected its combative corporate culture which soon tarnished the brand’s image.

Key takeaway #3: being ultra-aggressive is a double-edged sword

There’s no denying that without its extremely fast expansion Uber wouldn’t be the brand that we know today. But as scandals mounted and as Uber lost millions and billions of dollars in certain markets, we should ask ourselves if things could have been done differently. Ignoring local regulations, while it did work in some cases and was extremely costly in others, was never ethical. And we can probably all agree that even if a company adopts an aggressive playbook, it should do all it can to act ethically as well.

Uber’s toxic culture comes to light

Uber needed three key elements in place if it wanted to thrive as a global business.

- A set of country managers who are responsible for their individual markets.

- An understanding of how those markets differ.

- A unified executive team, which creates a centralized command center.

Under Kalanick, Uber actually had the first two. There were strong regional managers and a decentralized command structure that allowed them to enthusiastically implement Uber’s playbook.

However, Uber was lacking a unified executive team to coordinate global operations, including the activity of the individual country managers.

Not just that, back-biting, undermining, and infighting were the rule, not the exception, and executive meetings were often canceled at the last minute.

When we look at Uber’s playbook, that’s not really surprising. Uber always played to win and they did a really good job at recruiting teams of people who really wanted to win as well.

One of the downsides of this course of action is that if you exclusively focus on winning and getting around the existing regulations it quickly blurs the line of what's ethical and what's not ethical - not just when expanding, but inside the company as well.

It also brings into the company a certain kind of people - people that enjoy treating every encounter as a confrontation . Constantly fighting skirmishes outside and inside the company is not just exhausting but affects the morale at the company and the corporate culture.

Uber’s cultural guidelines weren’t helping. They ranged from the sober “Be Yourself” to full-on bro-tastic maxims like “Superpumped” and “Always be hustling”.

As the company scaled rapidly, so did its toxic culture and questionable business tactics. These led to a constant stream of nasty and very public challenges. They included political infighting, allegations of corporate espionage, and criminal investigations.

Then there were the many run-ins with regulators, taxi firms, and even Uber’s own drivers. Uber saw a backlash in some of its key markets which came to a head with the #DeleteUber campaign.

The old Uber logo didn’t help either. It emphasized the public’s perception of Uber’s hostility, imposing itself on customers with all-caps on black background, reflecting Uber’s hyper-masculine attitude.

While Kalanick did build a hugely successful business, an increasingly toxic culture had become a poison and tarnished the brand.

“The radical scale success of Uber that was unprecedented at the time, I think, led to a culture that was highly confident, a culture that was confrontational, a culture that to some extent celebrated breaking the rules . All of which made possible what Uber built, but which created a blind spot as to individual's respect, respect for diversity of different viewpoints, et cetera, that led to Susan Fowler's blog – which by the way wasn't the only difficult occurrence happening at the company,” says Dara Khosrowshahi, the current CEO of Uber.

Exposed by a blog post

The blog post Khosrowshahi mentions was published by a former Uber engineer Susan Fowler in February 2017. She described a toxic culture at the company where sexual harassment was rampant and managers cannibalized each other.

Her post received so much attention that Uber decided to respond by having the law firm Perkins Coie do an investigation into her allegations.

The CEO and co-founder of Uber, Travis Kalanick, began facing heavy scrutiny over Uber’s company culture. Earlier in 2017 Bloomberg also posted a video of him arguing with an uber driver over falling fare rates, which certainly didn’t help his case and further tarnished Uber’s brand.

The company finally recognized a crucial if simple truth: to maintain a sustainable brand long-term, Uber had to be honest about what it stood for. It postured itself as a cutting-edge, progressive company, yet its corporate culture was the opposite of progressive. The brand teetered on the brink of outright hypocrisy.

Kalanick resigned as CEO on June 20, 2017, and there were numerous other personnel casualties of Uber’s very public self-reflection.

The need to rebrand was clear: without a complete brand overhaul, Uber risked totaling its business and Uber decided to undergo a massive effort to restore its image and set itself up for the future.

Key takeaway #4: recognize when it’s time for a cultural shift

While the “always be hustling” mantra and “win at all costs” people might be required to succeed at a startup, there’s a time when such thinking should be left behind. As Uber grew and expanded it never really took a hard look at the corporate culture it created. It wasn’t a small startup anymore, it became a huge company and should’ve therefore acted more responsibly sooner. In the end, it was forced into an overhaul, but not before its toxic culture tarnished the brand.

Uber rebrands and goes public

When Uber decided to turn things around there were two major areas they focused on - one was their corporate culture and values and the other was their brand .

Khosrowshahi, the new CEO of Uber, said that they asked their employees what should represent the culture of Uber going forward.

He recaps the conversations and answers:

“We celebrate differences. We want to be a different company but we also celebrate differences and backgrounds and where you come from and religion and sexuality, et cetera, and we believe that no matter what you bring to the table, you should be able to contribute to what we call Uber.

The simplest answer that I hear repeated over and over is: We do the right thing, period. We didn't want to define to the employee what the right thing is. You know what the right thing is. Let's do that and, period, that's what we do.”

Listening, observing, and learning became the foundations of Uber’s cultural overhaul.

Since the change, some Uber executives even go the extra mile to participate as normal Uber drivers and experience what Uber’s drivers experience. The importance of getting one’s hands dirty is a part of the refreshed culture.

They started calling their drivers “driver-partners”.

“Now we have a fundamental connection there that is reflected in the

organization, we have a driver product team, and we now fundamentally build our

product with the driver. We talk to them, we have a dialogue with them, and we build with

them. That kind of connectivity with our driver-partners, I think, creates a win-win and it

creates mutual respect,” says Khosrowshahi.

The current CEO also recognized that executives can get out of touch with reality and said that whenever he goes from city to city he meets with drivers and asks them what they like and what they don’t like.

Uber also changed its approach to communication with governments and regulators. Before all the conversations and the dialogue was happening through lawyers, now Uber is trying to talk about their requests and find a compromise wherever they can’t agree with authorities.

While Uber is still facing challenges and there are still many dissatisfied parties, the company has changed its warlike and aggressive approach and is trying to make things work in a different, more humane way.

A new, more emphatic brand

Uber also embarked on a major rebranding intended to capture an accessible, progressive style that reflected the best of the company.

The company understood it faced a critical mission: it had to persuade customers that its lousy reputation left the building when its former CEO was replaced.

Uber opted for a complete redesign to overhaul the brand from the ground up.

Their new logo is the foundation of a substantial rebranding effort – one that incorporates a sense of mobility, accessibility, and friendliness not found in previous iterations. The company’s goal was to create a cohesive brand system described as “instantly recognizable, works around the world, and is efficient to execute” .

The agency Wolff-Olins summed up the project goals on their case study site :

“The brand needed to work around the world. Its highest growth areas are in regions outside of the US, such as Latin America and India, where Wolff Olins has a considerable depth of experience. Instead of pursuing a complex identity system, localized through color and pattern, we moved towards a universal ‘beyond simple global brand. Teams in diverse markets can make it relevant to their audiences with culturally specific content.”

What began as everyone’s personal driver is now all about moving forward and moving together .

The fresh logo was supplemented by creatives that included photos of people from around the world — serving two purposes. Firstly, it represents Uber’s global market, and secondly, adding this human element made the brand a whole lot more relatable. It’s no longer just a tech startup in Silicon Valley — it’s also the drivers you meet every morning, the co-riders you pool with every evening.

Arguably the best example of Uber’s new branding direction is their marketing campaign What moves you, moves us . It’s a campaign that focuses on the drivers and is built on empathy. It acknowledges and shows appreciation for their drivers' hard work and shows the customers who and what they’re supporting when they choose to ride with Uber.

More recently, Uber acknowledged the hard work of frontline healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic with a #GratefulUK campaign. The company offered them free rides and free meals during the Christmas period and encouraged people to share letters, drawings, poems, or doodles thanking the workers.

Overhauling the brand’s image and corporate culture were not the only major changes that happened after Uber’s scandalous years and Kalanick’s resignation. Another major step towards the maturity of the company happened in 2019 when Uber decided to go Public.

Going public - to boost reputation, get more money, or both?

In less than two years after the rebrand began, Uber decided to go public. Filing for IPO was likely a part of Uber’s rebranding plan.

Why? People tend to look at public companies as more mature. Going public also provides a sense of accountability because public companies have to report on a quarterly basis and are subject to the regulatory process. It opens the company up to an entire set of investors who drive transparency. That’s exactly what Uber needed after all the previous scandals.

Of course, the public market also provides greater liquidity and more readily available money, which Uber needed as well as it was losing billions of dollars on a yearly basis.

However, Uber's IPO didn’t go as well as expected. Uber’s valuation predictions hovered around $120 billion , which would’ve made it the most valuable company to ever go public. In the end, Uber priced its stock at $45 apiece for a valuation of $82.4 billion , which was lower than many expected yet it is still one of the most valuable exits in history. Uber’s stock began falling right away, but we won’t go further into that.

What’s more important - the company has become public which means new pressure from big investors and shareholders every quarter to stem their losses. And as we’ll see later on, Uber’s eventual profitability is not nearly guaranteed.

Before we dive into the questions of profitability, we should examine how Uber defined itself as an innovative company and how it evolved in the last 10 years.

Key takeaway #5: when you need to change, show dedication

Although the jury is still out on how successful Uber’s rebranding actually is, it’s clear that they’ve undergone major steps to repair their reputation. And there’s really no other way to do it. If you want to rescue a tarnished brand, you have to show that you’re truly dedicated to making it work and aren’t just trying to save face for your own sake.

Uber innovation & diversification strategy

Although Uber is known as the main disruptor in the transport industry, the company is actually not the ridesharing pioneer, but a fast follower in the sector.

Uber’s competitor Lyft and former competitor Sidecar (which shuttered back in 2015) are the ones that pioneered ridesharing as it is known today, which entails using non-professional, non-commercially insured vehicles and drivers.

Uber initially worked exclusively with commercially licensed, insured, and regulated entities (known as Black Cars in many areas) before transitioning to the current ridesharing model.

While Uber was a fast follower, it expanded quicker and more aggressively and offered a better user experience which led to market dominance in many regions.

In fact, Uber followed a market entry pattern that has proven successful for business entities in the past – Myspace preceded Facebook, Yahoo preceded Google, and Blackberry preceded Apple’s iPhone. Historical patterns of transformation suggest that being first does have its advantages, but entering the market early and iterating quickly is even more vital when it comes to dominating a market.

Uber’s expansion playbook is a prime example of how quickly they adapted their model and grabbed the opportunity of extremely fast expansion which was possible because of the significant funding the company received.

Their activation of early adopters and passionate customers to support Uber via petitions and pressure on local authorities can also be seen as an innovative approach to one of the ridesharing market’s main challenges.

A flexible pricing model

Uber’s surge pricing model is another example of a simple yet ingenious solution to a very real problem of the taxi industry - how to get a ride when you simply can’t get a cab . That can happen during peak traffic times or during bad weather.

When Uber’s demand for rides is higher than the supply the prices surge. That means users can almost always get a ride if they’re prepared to pay enough.

Researcher Oliver Senn analyzed satellite data on weather conditions over a two-month period, and he obtained 830 million GPS records of 80 million taxi trips. The data shows that it was not the high demand for taxis that resulted in a perceived shortage on rainy days; instead, it appeared that many cabbies simply did not pick up passengers, fearing accidents on the wet roads. However, Uber entices their drivers with higher prices and therefore higher earnings when there’s a shortage of rides.

While plenty of users don’t like the surge pricing, it proved to be a way to get more drivers in the area to take advantage of higher earnings when there’s a shortage of available rides.

Reviews ensure a better service

Another massive differentiator between Uber and traditional taxis is that Uber has rating systems for both drivers and passengers. A review system by itself is nothing new, but it hasn’t been used in the transport industry before - especially not on an individual basis.

The system is a simple solution to the question: “How will drivers and passengers behave?”

It promotes trust in Uber and better behavior on the parts of both driver and passenger as it weeds out the bad users.

More than just a ridesharing service

Over the years Uber has become more than just a ridesharing company. It’s leveraging its underlying technology to test new services that have the potential to generate additional revenue and fuel Uber’s ambitions.

By introducing new services that add incremental value for users, Uber creates opportunities to capture a larger share of their consumer’s wallets, while also retaining and generating additional income for drivers as well.

There are two main services that stuck around: Uber Freight and Uber Eats.

Uber Freight

Uber Freight is basically Uber for trucks. Uber launched its own on-demand trucking app in 2017 with the core idea of seamlessly matching shippers with carriers.

In August 2018, it was spun off into a separate business unit, a move that simultaneously allowed it to gain momentum and burn more cash. After spinning off of Uber, the freight company underwent an expansion.

In 2020 an investment firm Greenbriar Equity Group has committed to invest $500 million in a Series A preferred stock financing for Uber Freight. When announcing the investment Uber said it will maintain majority ownership in Uber Freight and will use the funds to continue to scale its logistics platform, which helps truck drivers connect with shipping companies.

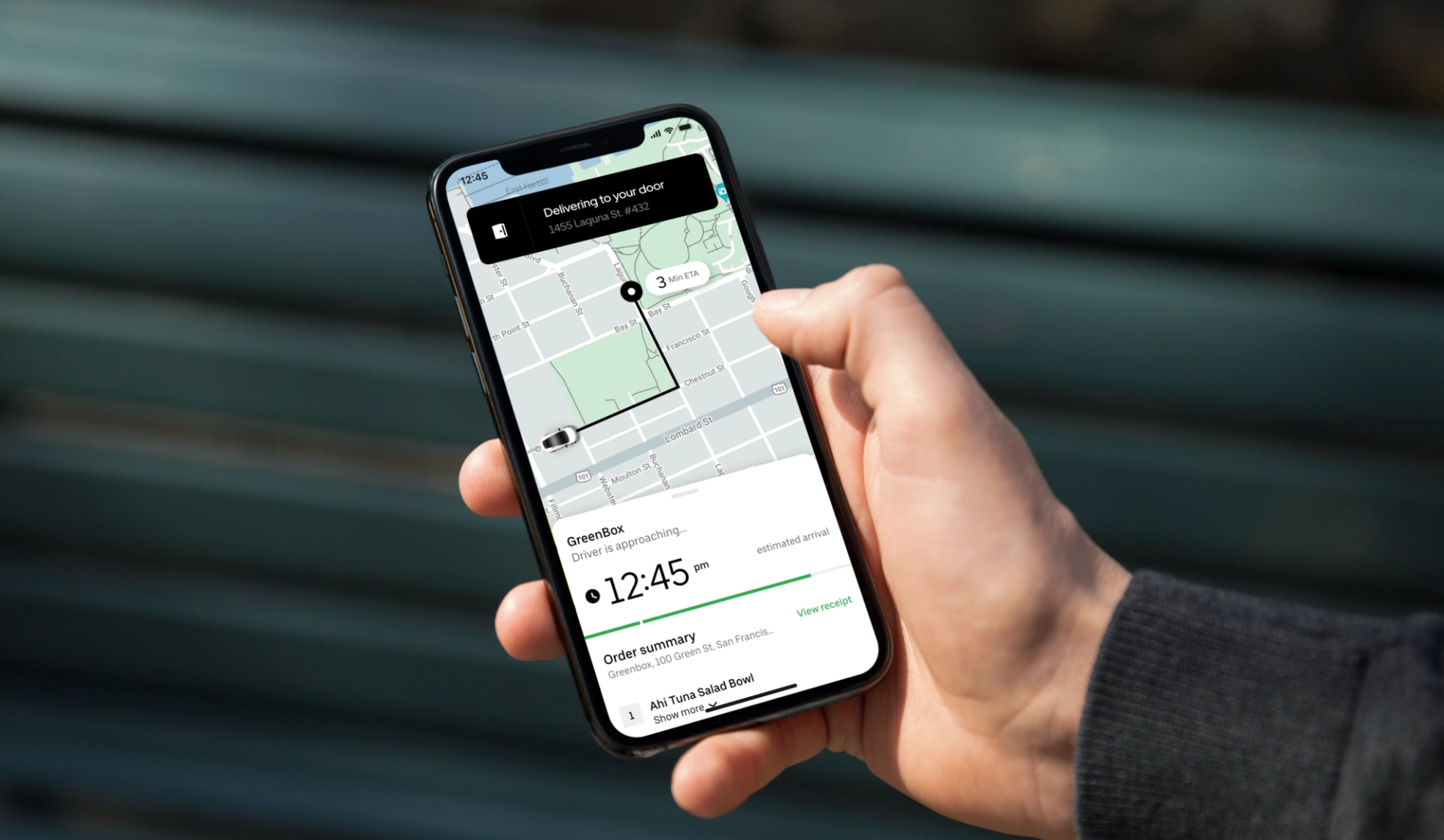

Uber Eats food delivery service launched in 2016 and it was a logical next step for Uber as it aligns with its ridesharing business and helps it utilize its large fleet of drivers. It launched as a separate app and grew in popularity at a rapid pace.

.jpg)

Uber Eats ensured that Uber’s customers used the company’s services more often than ever before. Users who used both Uber and Uber Eats booked an average of 11.5 trips per month, versus only 4.9 trips for those using only a single Uber service.

Consumers benefited from an additional convenient service, and drivers gained a new source of trips which generated a more steady stream of bookings throughout the day, which in turn increased the overall supply of drivers.

With drivers now busier and making more consistent income, they have less reason to dual-app and drive for a competing service like Lyft.

Uber Eats was also huge for Uber during the Covid-19 pandemic. While Uber’s ride-hailing segment contracted by 24%, Uber Eats increased revenues by over 200% in 2020 and prevented a much higher loss of revenue that would have occurred if Uber hadn’t diversified its services.

Uber Revenue by Segment

YearMobilityDeliveryFreightOther2018$8.9 Billion$0.7 Billion$0.3 Billion$0.1 Billion2019$10.4 Billion$1.3 Billion$0.7 Billion$1.3 Billion2020$7.9 Billion$4.8 Billion$0.9 Billion$1.3 Billion

Dreaming of self-driving cars

You may have heard of Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group(ATG) which was established in 2016 with the purpose of developing self-driving cars. Kalanick, the CEO at the time, saw it as an essential investment and there’s no doubt that fully self-driving cars would immensely benefit Uber.

However, ATG brought high costs and safety challenges . Throughout the course of a pandemic-stricken year, Uber has made efforts to stem losses in its ride-hailing business and control business costs. That’s why at the end of 2020 ATG was acquired by its start-up competitor Aurora Innovation. In fact, Uber handed its equity in ATG to Aurora and then invested $400 million into Aurora, which will give Uber a 26% stake in the company. Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi will also join Aurora’s board.

“With the addition of ATG, Aurora will have an incredibly strong team and technology, a clear path to several markets, and the resources to deliver,” Chris Urmson, co-founder and CEO of Aurora, said in a statement. “Simply put, Aurora will be the company best positioned to deliver the self-driving products necessary to make transportation and logistics safer, more accessible, and less expensive.”

Uber positioned itself to be right there once Aurora develops their self-driving car, which just might be the key to Uber’s profitability in the future.

Looking towards the future

While Uber’s plans for the future after the pandemic are not set in stone, Khosrowshahi says that people should think about Uber not as a service but as a transportation platform or as an Amazon of transportation. He said that people will be able to take a bus, to take a car, to take a train or to take a taxi using Uber. It would be a win for the consumer because the more choices they've got, the more pricing they've got, the better the product is.

Uber is aiming to pivot their strategy so that it is more inclusive. How they are planning to do that is yet to be seen, but we can be certain they’re going to try and offer new services and further diversify their product as that might be their only option if the company wants to become profitable.

Key takeaway #6: keep innovating and evolving

Uber doesn’t rest on its laurels of being the first prominent rideshare app. Its founders understood really well that the competition will grow over time and they can only stay ahead if they evolve and diversify. They keep adding new features and new services while constantly looking to invest in new technologies.

Will Uber ever be profitable?

Although Uber claims that it will soon become profitable, there are many sceptics that think it won’t happen - and with a good reason.

Uber has been losing billions of dollars during the last few years. Although Uber losses improved in 2020 due to Uber Eats, the company still lost $6.77 billion . Uber plans to minimize losses in 2021, yet due to the ongoing pandemic, Uber had to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in incentives to get drivers back on the streets once the Covid situation improved and the demand increased.

Hubert Horan , a transportation industry expert who has published in-depth analyses of the company's financial outlook, has this to say about Uber’s profitability:

"Not only can I not imagine any remotely plausible explanation as to how Uber could suddenly become profitable after eleven years of massive losses, but absolutely no one has attempted to lay out a financial analysis making such a case. Not the company, not Wall Street analysts, not academics — no one."

In its S-1, a document that every company must file with the SEC if it wants to go public, Uber itself acknowledged and warned that it was possible it would never become profitable .

How come such a successful company that is a magnet for investors still struggles with such heavy losses?

The thing is Uber doesn't really have an edge over its competitors. A smartphone app that matches passengers with drivers can be — and has been — replicated by countless other companies. And once there are competitors, Uber doesn’t offer a service that would be that much more efficient.

As it often does, it all comes down to costs-leadership . The need for human drivers that have to earn a living wage seems to be a vexing problem for the ride-hailing industry. It just costs too much.

That's why Uber once staked so much of its future on self-driving cars, which could potentially reduce the company’s per-mile cost by 80% . But as you know, Uber has already sold its self-driving research center.

The typical explanation of the Uber model is that its focus has been on growth, not profit. Huge investments allowed Uber to keep scaling up until it was everywhere and ensured that the populace relied on its service. According to Horan, its plan was to "eliminate all meaningful competition and then profit from this quasi-monopoly power" in the exact same way that Amazon has managed to do for e-commerce. Except that it hasn't worked as competition is still here and Uber’s core service is not that different from it.

Uber’s push for profitability might be the reason that as of April 2021, the cost of a ride had increased by 40% as the New York Times reported . Why? The increase might be due to the shortage of drivers at the time. Uber is notorious for not paying drivers enough (according to the drivers), but that only works until the point that a critical number of them decide that it isn't worth any of their time.

To counter that Uber has to raise fares, but then it runs the risk of losing a big part of their market and their revenue, even with higher per-passenger fares.

What’s the solution? That’s probably the most important question in Uber’s history and one that will define its future. It’s also the reason Uber is trying to position itself as a transportation platform and not just a ridesharing service as profitability continues to be an industry-wide problem.

Key takeaway #7: have a clear plan on how to become profitable

Although Uber is one of the fastest-growing and arguably one of the most successful companies in the last decades, it’s still not profitable and it’s a fair question if it ever will be. This shows that growth is not everything and if you want to run a sustainable business you have to know how it will eventually become profitable.

Uber’s SWOT analysis

Let’s recap everything we’ve covered during this strategy study in a concise SWOT analysis.

Global brand recognition

Uber’s brand is unmistakable and has become a synonym for “ridesharing.” Uber is present in over 60 countries worldwide and is the first ridesharing brand that comes to mind when new users are looking for ridesharing apps.

A strong market position

Uber is the largest ridesharing platform in the U.S. and worldwide. Currently, Uber’s market share in the US is 68% and 32,4% worldwide. In an industry that’s all about the quantity that’s extremely important.

Knows how to diversify

One of Uber’s key success factors is its ability to adapt and innovate to encompass changing needs. This can be seen in its diversification into logistics with Uber Freight and broadening its services to offer groceries and food delivery with UberEats. Diversification plays a huge part in Uber’s total revenue.

Dynamic pricing model

Uber’s surge pricing strategy has been good for its drivers. Drivers can earn more at night, in bad weather conditions, and during the holidays. This encourages more drivers to take ride requests to meet demand surges.

Low operational costs

Uber is based on low fixed investments and minimal physical assets. It has a fleet of cars they don’t actually own and no full-time drivers which helps to keep operational costs down.

Convenient to use

That’s the whole point of Uber. Anyone can order a ride with a few taps on their screen, learn the price of the ride and pay it through the app.

More affordable than cabs

Uber was and still is more affordable than most cabs and its competition. However, that might change with the recent price surges.

Generally good service due to the review system

Uber riders have the ability to rate their trip and the driver. As drivers are always trying to improve their ratings, riders will most likely experience good service.

Bad publicity due to scandals

Despite Uber’s rebranding, stories of former sexual harassment scandals, driver fraud, and reports of very low driver’s wages reflect poorly on the company’s image and might alienate drivers as well as riders.

Substantial losses

Uber has lost billions of dollars year after year, which is starting to affect its image and spending. Nobody really knows if the company can become profitable and when or how it might happen.

Low-profit margins

Uber has to keep its fares low and can’t increase its commission per trip leading to low-profit margins. As we’ve seen, Uber's unprofitability has already prompted it to withdraw from China, Russia, and Southeast Asia.

Dependency on their workforce

Uber is heavily dependent on its drivers. They are essentially Uber’s brand ambassadors 24/7. However, their behavior is unpredictable and the company’s image is hurt every time a scandalous story reaches the news. Many drivers have been accused of harassment and abuse.

The main service can be easily replicated

The ridesharing industry has a relatively low barrier of entry and Uber’s main functionality can be easily replicated by potential competitors which happened in Southeast Asia.

Opportunities

Further diversification

Uber Eats exploded during the recent Covid-19 Pandemic and significantly increased Uber’s revenue in 2020. Uber Freight also grew by 64% in Q2 of 2021 and earned $348 million. Further diversification might be one of the more viable paths towards Uber’s profitability.

Self-driving cars

While not there yet, driverless technology would significantly lower Uber’s operational costs while eliminating scandalous stories caused by their drivers’ bad behavior.

New markets

There are still many untapped growth opportunities in many countries. In fact, t he acquisition of Careem by Uber with $3.1 billion has opened the door to an incredible business opportunity for the company in the Middle East.

Local laws and regulations Uber has previously ignored

Increasing pressures from local authorities require Uber to comply with certain laws, which the company skirted when setting up in different countries. Non-compliance with local laws incurs fines and results in bad publicity. At the same time, the communities of traditional taxis are pushing heavily on the enforcement of some type of regulation.

Low driver’s wages

Uber drivers reportedly earn less than minimum wage in many locations. Drivers have become more active in various locations in advocating for their “fair share” and are pressuring Uber to increase their wages, which would make it even harder to become profitable.

Employee retention

Unsatisfied drivers may switch to rival platforms due to better incentives from competitors from the ride-hailing market or from other parts of the sharing economy.

More and more competition

As the ridesharing market becomes more saturated, it will become more difficult for Uber to retain customers as shifting to other services if they offer lower prices is very easy. This goes for services like food delivery as well.

Final thoughts and key lessons

Uber is a fascinating company with a fascinating story. It’s one of the most famous disruptors in the last decade, yet its technology is not really disruptive. But the way it uses it and combines it with its business model certainly is!

If there’s one thing that defines Uber it’s determination .

Determination to stick to their brand strategy of a technological company and an industry disruptor. Determination to quickly expand across the globe even if it means taking on regulators and local authorities. Determination to right the ship and overhaul the culture once they recognized their mistakes.

What allowed Uber to do all of the above while adapting to different challenges and markets is its lack of assets . That’s where the company really shines - they solved a big real-world problem with the fewest possible assets.

Uber is not a shining example of a company that did everything right.

But no one can argue that it looked for an opening, grabbed the chance, and achieved amazing things.

It’s a walking lesson that sometimes you have to grab the opportunity before it’s too late, learn on the flight, and do your best to correct your mistakes as you go .

In the end, Uber disrupted an entire industry and achieved a multi-billion-dollar IPO. Who knows what would’ve happened if they waited to have everything figured out?

Recap: Growth by the numbers