Health (Nursing, Medicine, Allied Health)

- Find Articles/Databases

- Reference Resources

- Evidence Summaries & Clinical Guidelines

- Drug Information

- Health Data & Statistics

- Patient/Consumer Facing Materials

- Images and Streaming Video

- Grey Literature

- Mobile Apps & "Point of Care" Tools

- Tests & Measures This link opens in a new window

- Citing Sources

- Selecting Databases

- Framing Research Questions

- Crafting a Search

- Narrowing / Filtering a Search

- Expanding a Search

- Cited Reference Searching

- Saving Searches

- Term Glossary

- Critical Appraisal Resources

- What are Literature Reviews?

- Conducting & Reporting Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Tutorials & Tools for Literature Reviews

- Finding Full Text

What are Systematic Reviews? (3 minutes, 24 second YouTube Video)

Systematic Literature Reviews: Steps & Resources

These steps for conducting a systematic literature review are listed below .

Also see subpages for more information about:

- The different types of literature reviews, including systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis methods

- Tools & Tutorials

Literature Review & Systematic Review Steps

- Develop a Focused Question

- Scope the Literature (Initial Search)

- Refine & Expand the Search

- Limit the Results

- Download Citations

- Abstract & Analyze

- Create Flow Diagram

- Synthesize & Report Results

1. Develop a Focused Question

Consider the PICO Format: Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Focus on defining the Population or Problem and Intervention (don't narrow by Comparison or Outcome just yet!)

"What are the effects of the Pilates method for patients with low back pain?"

Tools & Additional Resources:

- PICO Question Help

- Stillwell, Susan B., DNP, RN, CNE; Fineout-Overholt, Ellen, PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN; Melnyk, Bernadette Mazurek, PhD, RN, CPNP/PMHNP, FNAP, FAAN; Williamson, Kathleen M., PhD, RN Evidence-Based Practice, Step by Step: Asking the Clinical Question, AJN The American Journal of Nursing : March 2010 - Volume 110 - Issue 3 - p 58-61 doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368959.11129.79

2. Scope the Literature

A "scoping search" investigates the breadth and/or depth of the initial question or may identify a gap in the literature.

Eligible studies may be located by searching in:

- Background sources (books, point-of-care tools)

- Article databases

- Trial registries

- Grey literature

- Cited references

- Reference lists

When searching, if possible, translate terms to controlled vocabulary of the database. Use text word searching when necessary.

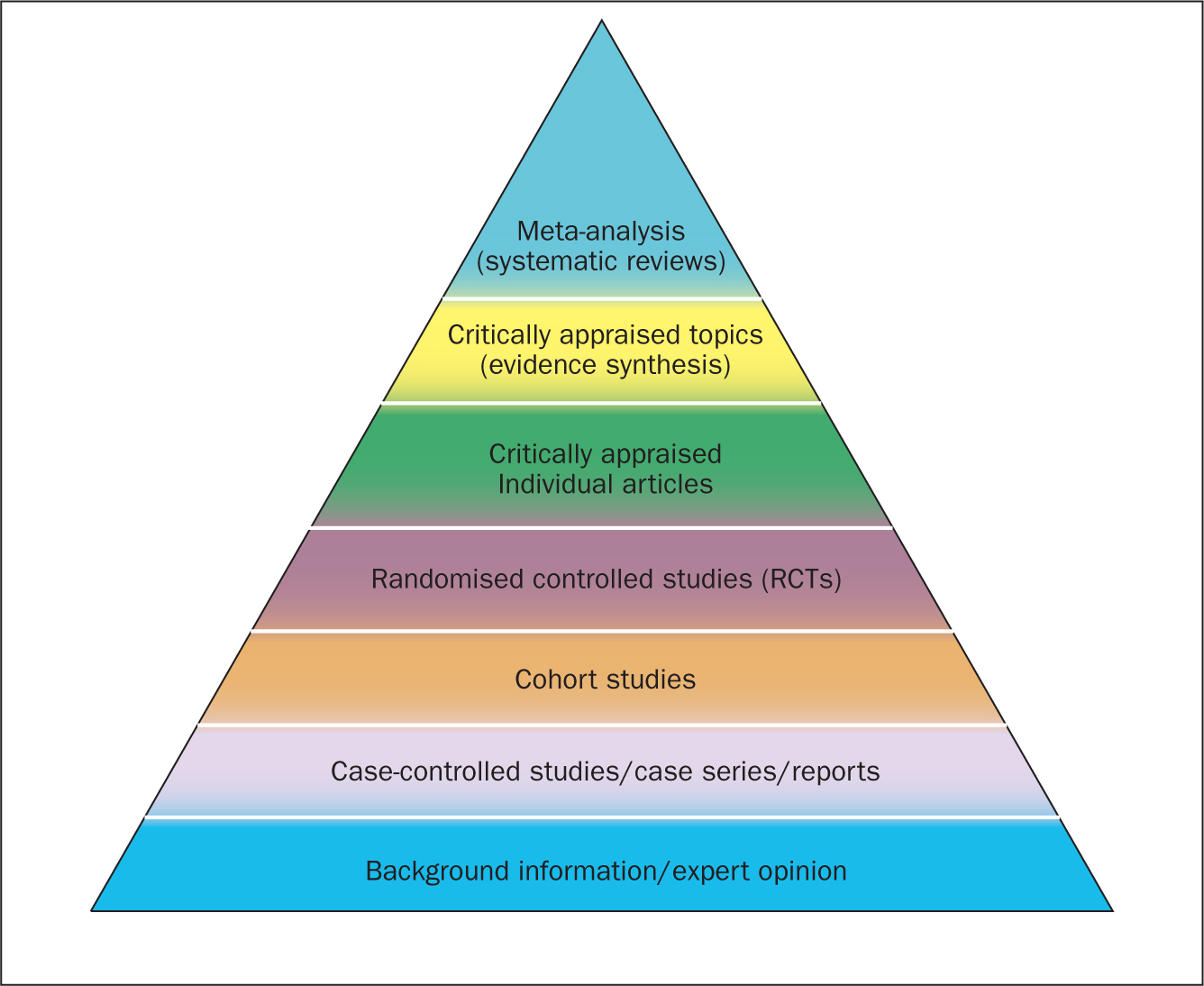

Use Boolean operators to connect search terms:

- Combine separate concepts with AND (resulting in a narrower search)

- Connecting synonyms with OR (resulting in an expanded search)

Search: pilates AND ("low back pain" OR backache )

Video Tutorials - Translating PICO Questions into Search Queries

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in PubMed (YouTube, Carrie Price, 5:11)

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in CINAHL (YouTube, Carrie Price, 4:56)

3. Refine & Expand Your Search

Expand your search strategy with synonymous search terms harvested from:

- database thesauri

- reference lists

- relevant studies

Example:

(pilates OR exercise movement techniques) AND ("low back pain" OR backache* OR sciatica OR lumbago OR spondylosis)

As you develop a final, reproducible strategy for each database, save your strategies in a:

- a personal database account (e.g., MyNCBI for PubMed)

- Log in with your NYU credentials

- Open and "Make a Copy" to create your own tracker for your literature search strategies

4. Limit Your Results

Use database filters to limit your results based on your defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition to relying on the databases' categorical filters, you may also need to manually screen results.

- Limit to Article type, e.g.,: "randomized controlled trial" OR multicenter study

- Limit by publication years, age groups, language, etc.

NOTE: Many databases allow you to filter to "Full Text Only". This filter is not recommended . It excludes articles if their full text is not available in that particular database (CINAHL, PubMed, etc), but if the article is relevant, it is important that you are able to read its title and abstract, regardless of 'full text' status. The full text is likely to be accessible through another source (a different database, or Interlibrary Loan).

- Filters in PubMed

- CINAHL Advanced Searching Tutorial

5. Download Citations

Selected citations and/or entire sets of search results can be downloaded from the database into a citation management tool. If you are conducting a systematic review that will require reporting according to PRISMA standards, a citation manager can help you keep track of the number of articles that came from each database, as well as the number of duplicate records.

In Zotero, you can create a Collection for the combined results set, and sub-collections for the results from each database you search. You can then use Zotero's 'Duplicate Items" function to find and merge duplicate records.

- Citation Managers - General Guide

6. Abstract and Analyze

- Migrate citations to data collection/extraction tool

- Screen Title/Abstracts for inclusion/exclusion

- Screen and appraise full text for relevance, methods,

- Resolve disagreements by consensus

Covidence is a web-based tool that enables you to work with a team to screen titles/abstracts and full text for inclusion in your review, as well as extract data from the included studies.

- Covidence Support

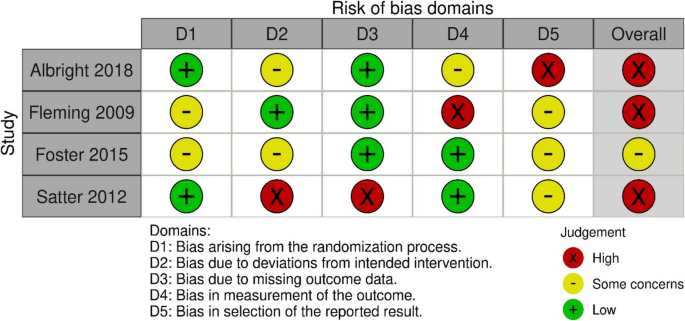

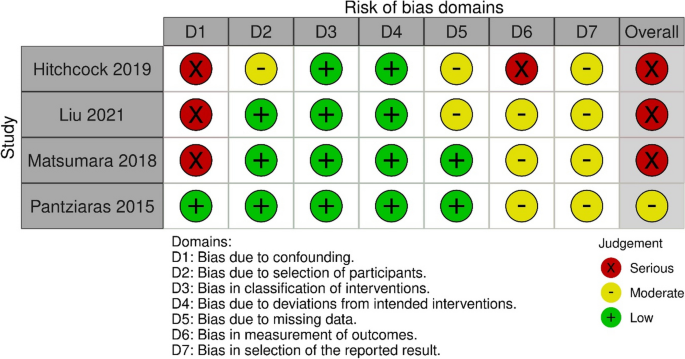

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Data Extraction Tools

7. Create Flow Diagram

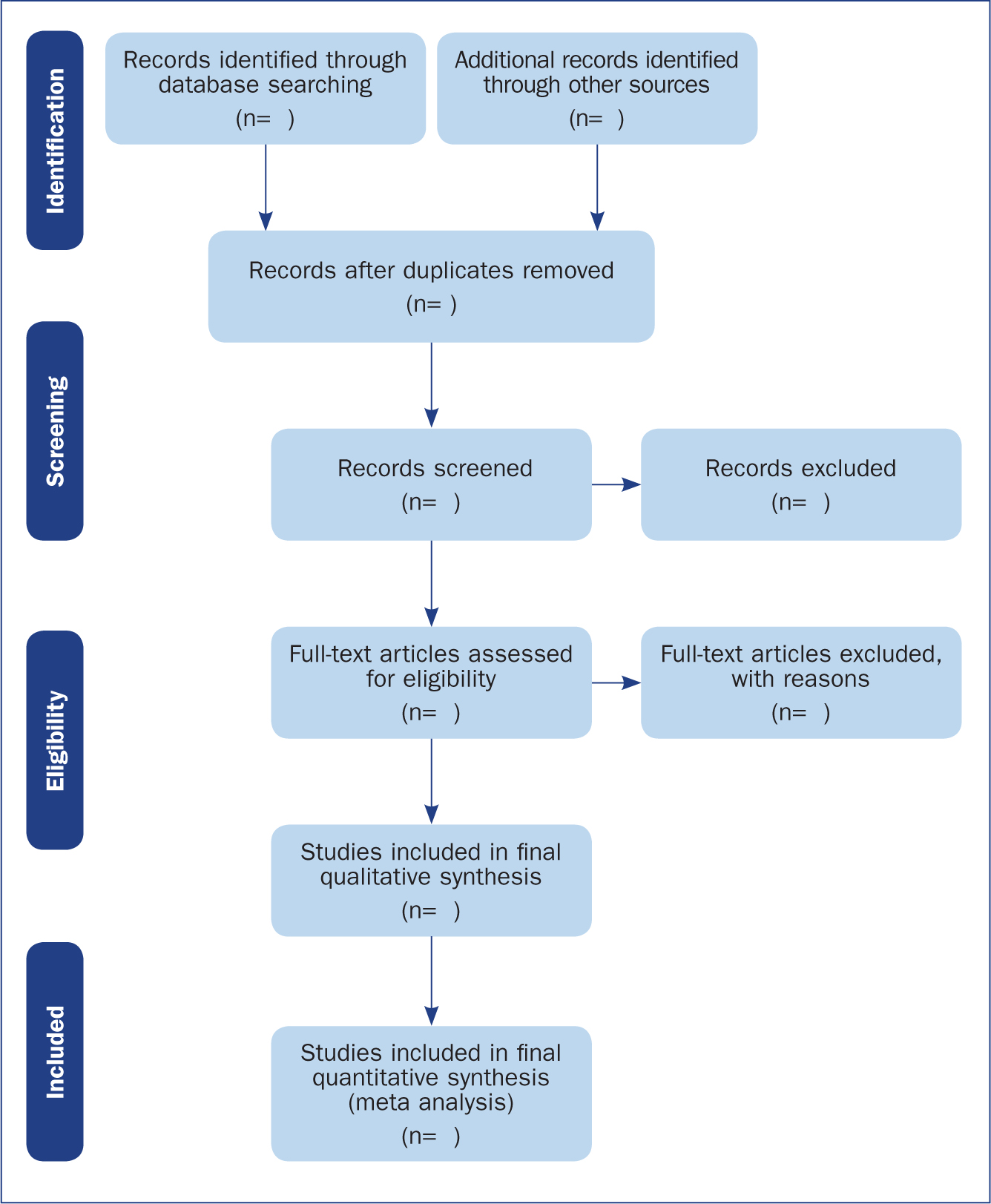

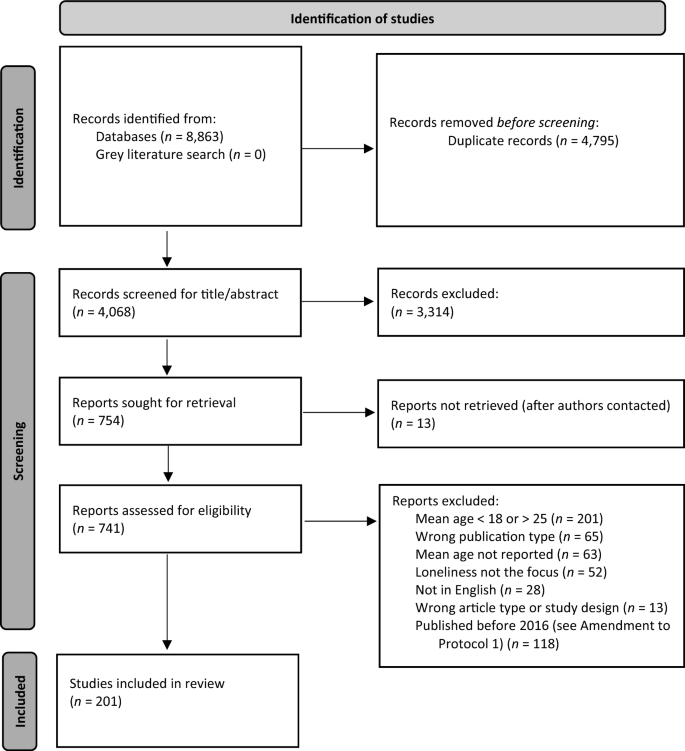

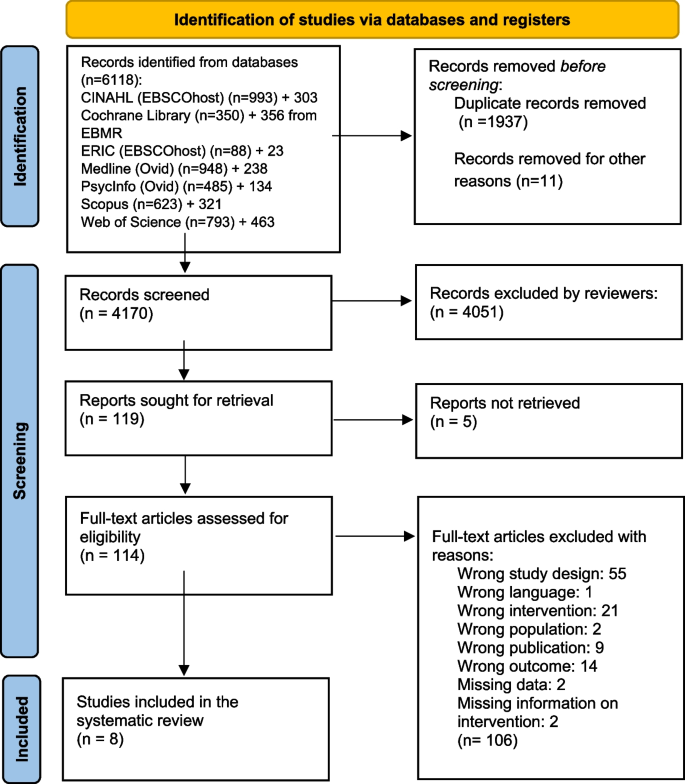

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram is a visual representation of the flow of records through different phases of a systematic review. It depicts the number of records identified, included and excluded. It is best used in conjunction with the PRISMA checklist .

Example from: Stotz, S. A., McNealy, K., Begay, R. L., DeSanto, K., Manson, S. M., & Moore, K. R. (2021). Multi-level diabetes prevention and treatment interventions for Native people in the USA and Canada: A scoping review. Current Diabetes Reports, 2 (11), 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-021-01414-3

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator (ShinyApp.io, Haddaway et al. )

- PRISMA Diagram Templates (Word and PDF)

- Make a copy of the file to fill out the template

- Image can be downloaded as PDF, PNG, JPG, or SVG

- Covidence generates a PRISMA diagram that is automatically updated as records move through the review phases

8. Synthesize & Report Results

There are a number of reporting guideline available to guide the synthesis and reporting of results in systematic literature reviews.

It is common to organize findings in a matrix, also known as a Table of Evidence (ToE).

- Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Download a sample template of a health sciences review matrix (GoogleSheets)

Steps modified from:

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2012). Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Medical Education , 46 (10), 943–952.

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal Resources

- Next: What are Literature Reviews? >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/health

Further reading & examples

Journal articles.

- Examples of literature reviews

- Articles on literature reviews

- Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: a literature review Al-Mutair, A. S., Plummer, V., O'Brien, A., & Clerehan, R. (2013). Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: a literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(13/14), 1805-1817. doi:10.1111/jocn.12065

- A literature review exploring how healthcare professionals contribute to the assessment and control of postoperative pain in older people Brown, D. (2004). A literature review exploring how healthcare professionals contribute to the assessment and control of postoperative pain in older people. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(6b), 74-90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01047.x

- Effects of team coordination during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review of the literature Castelao, E. F., Russo, S. G., Riethmüller, M., & Boos, M. (2013). Effects of team coordination during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Critical Care, 28(4), 504-521. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.01.005

- Literature review: Eating and drinking in labour Hunt, L. (2013). Literature review: Eating and drinking in labour. British Journal of Midwifery, 21(7), 499-502.

- Collaboration between hospital physicians and nurses: An integrated literature review Tang, C. J., Chan, S. W., Zhou, W. T., & Liaw, S. Y. (2013). Collaboration between hospital physicians and nurses: An integrated literature review. International Nursing Review, 60(3), 291-302. doi:10.1111/inr.12034

- A systematic literature review of Releasing Time to Care: The Productive Ward Wright, S., & McSherry, W. (2013). A systematic literature review of Releasing Time to Care: The Productive Ward. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(9/10), 1361-1371. doi:10.1111/jocn.12074

- Learning how to undertake a systematic review: part 1. Bettany-Saltikov, J. (2010). Learning how to undertake a systematic review: part 1. Nursing Standard, 24(50), 47-56.

- Users' guide to the surgical literature: how to use a systematic literature review and meta-analysis Bhandari, M., Devereaux, P. J., Montori, V., Cinà, C., Tandan, V., & Guyatt, G. H. (2004). Users' guide to the surgical literature: how to use a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Surgery, 47(1), 60-67.

- Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature Carnwell, R., & Daly, W. (2001). Strategies for the construction of a critical review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice, 1(2), 57-63.

- Thoughts about conceptual models, theories, and literature reviews Fawcett, J. (2013). Thoughts about conceptual models, theories, and literature reviews. Nursing Science Quarterly, 26(3), 285-288. doi:10.1177/0894318413489156

- Turn a stack of papers into a literature review: useful tools for beginners Talbot, L., & Verrinder, G. (2008). Turn a Stack of Papers into a Literature Review: Useful Tools for Beginners. Focus on health professional education: a multi-disciplinary journal, 10(1), 51-58.

- << Previous: Evaluation templates

- Next: Referencing and further help >>

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

How to Conduct a Literature Review (Health Sciences and Beyond)

What is a literature review, traditional (narrative) literature review, integrative literature review, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, scoping review.

- Developing a Research Question

- Selection Criteria

- Database Search

- Documenting Your Search

- Organize Key Findings

- Reference Management

Ask Us! Health Sciences Library

The health sciences library.

Call toll-free: (844) 352-7399 E-mail: Ask Us More contact information

Related Guides

- Systematic Reviews by Roy Brown Last Updated Oct 17, 2023 513 views this year

- Write a Literature Review by John Glover Last Updated Oct 16, 2023 2721 views this year

A literature review provides an overview of what's been written about a specific topic. There are many different types of literature reviews. They vary in terms of comprehensiveness, types of study included, and purpose.

The other pages in this guide will cover some basic steps to consider when conducting a traditional health sciences literature review. See below for a quick look at some of the more popular types of literature reviews.

For additional information on a variety of review methods, the following article provides an excellent overview.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. Review. PubMed PMID: 19490148.

- Next: Developing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/health-sciences-lit-review

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Searching the public health & medical literature more effectively: literature review help.

- Getting Started

- Articles: Searching PubMed This link opens in a new window

- More Sources: Databases, Systematic Reviews, Grey Literature

- Organize Citations & Search Strategies

- Literature Review Help

- Need More Help?

Writing Guides, Manuals, etc.

Literature Review Tips Handouts

Write about something you are passionate about!

- About Literature Reviews (pdf)

- Literature Review Workflow (pdf)

- Search Tips/Search Operators

- Quick Article Evaluation Worksheet (docx)

- Tips for the Literature Review Workflow

- Sample Outline for a Literature Review (docx)

Ten simple rules for writing a literature review . Pautasso M. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(7):e1003149. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

Conducting the Literature Search . Chapter 4 of Chasan-Taber L. Writing Dissertation and Grant Proposals: Epidemiology, Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2014.

A step-by-step guide to writing a research paper, from idea to full manuscript . Excellent and easy to follow blog post by Dr. Raul Pacheco-Vega.

Data Extraction

Data extraction answers the question “what do the studies tell us?”

At a minimum, consider the following when extracting data from the studies you are reviewing ( source ):

- Only use the data elements relevant to your question;

- Use a table, form, or tool (such as Covidence ) for data extraction;

- Test your methods and tool for missing data elements, redundancy, consistency, clarity.

Here is a table of data elements to consider for your data extraction. (From University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination).

Critical Reading

As you read articles, write notes. You may wish to create a table, answering these questions:

- What is the hypothesis?

- What is the method? Rigorous? Appropriate sample size? Results support conclusions?

- What are the key findings?

- How does this paper support/contradict other work?

- How does it support/contradict your own approach?

- How significant is this research? What is its special contribution?

- Is this research repeating existing approaches or making a new contribution?

- What are its strengths?

- What are its weaknesses/limitations?

From: Kearns, H. & Finn, J. (2017) Supervising PhD Students: A Practical Guide and Toolkit . AU: Thinkwell, p. 103.

Submitting to a Journal? First Identify Journals That Publish on Your Topic

Through Scopus

- Visit the Scopus database.

- Search for recent articles on your research topic.

- Above the results, click “Analyze search results."

- Click in the "Documents per year by source" box.

- On the left you will see the results listed by the number of articles published on your research topic per journal.

Through Web of Science

- Visit the Web of Science database.

- In the results, click "Analyze Results" on the right hand side.

- From the drop-down menu near the top left, choose "Publication Titles."

- Change the "Minimum record count (threshold)," if desired.

- Scroll down for a table of results by journal title.

- JANE (Journal/Author Name Estimator) Use JANE to help you discover and decide where to publish an article you have authored. Jane matches the abstract of your article to the articles in Medline to find the best matching journals (or authors, or articles).

- Jot (Journal Targeter) Jot uses Jane and other data to determine journals likely to publish your article (based on title, abstract, references) against the impact metric of those journals. From Yale University.

- EndNote Manuscript Matcher Using algorithms and data from the Web of Science and Journal Citation Reports, Manuscript Matcher identifies the most relevant and impactful journals to which one may wish to submit a manuscript. Access Manuscript Matcher via EndNote X9 or EndNote 20.

- DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) Journal Lookup Look up a journal title on DOAJ and find information on publication fees, aims and scope, instructions for authors, submission to publication time, copyright, and more.

Writing Help @UCB

Here is a short list of sources of writing help available to UC Berkeley students, staff, and faculty:

- Purdue OWL Excellent collection of guides on writing, including citing/attribution, citation styles, grammar and punctuation, academic writing, and much more.

- Berkeley Writing: College Writing Programs "Our philosophy includes small class size, careful attention to building your critical reading and thinking skills along with your writing, personalized attention, and a great deal of practice writing and revising." Website has a Writing Resources Database .

- Graduate Writing Center, Berkeley Graduate Division Assists graduate students in the development of academic skills necessary to successfully complete their programs and prepare for future positions. Workshops and online consultations are offered on topics such as academic writing, grant writing, dissertation writing , thesis writing , editing, and preparing articles for publication, in addition to writing groups and individual consultations.

- Nature Masterclass on Scientific Writing and Publishing For Postdocs, Visiting Scholars, and Visiting Student Researchers with active, approved appointments, and current UC Berkeley graduate students who are new to publishing or wish to refresh their skills. Part 1: Writing a Research Paper; Part 2: Publishing a Research Paper; Part 3: Writing and Publishing a Review Paper. Offered by Visiting Researcher Scholar and Postdoc Affairs (VSPA) program; complete this form to gain access.

Alternative Publishing Formats

Here is some information and tips on getting your research to a broader, or to a specialized, audience

- Creating One-Page Reports One-page reports are a great way to provide a snapshot of a project’s activities and impact to stakeholders. Summarizing key facts in a format that is easily and quickly digestible engages the busy reader and can make your project stand out. From EvaluATE .

- How to write an Op-ed (Webinar) Strategies on how to write sharp op-eds for broader consumption, one of the most important ways to ensure your analysis and research is shared in the public sphere. From the Institute for Research on Public Policy .

- 10 tips for commentary writers From UC Berkeley Media Relations’ 2017 Op-Ed writing workshop.

- Journal of Science Policy and Governance JSPG publishes policy memos, op-eds, position papers, and similar items created by students.

- Writing Persuasive Policy Briefs Presentation slides from a UCB Science Policy Group session.

- 3 Essential Steps to Share Research With Popular Audiences (Inside Higher Ed) How to broaden the reach and increase the impact of your academic writing. Popular writing isn’t a distraction from core research!

The Politics of Citation

"One of the feminist practices key to my teaching and research is a feminist practice of citation."

From The Digital Feminist Collective , this blog post emphasizes the power of citing.

"Acknowledging and establishing feminist genealogies is part of the work of producing more just forms of knowledge and intellectual practice."

Here's an exercise (docx) to help you in determining how inclusive you are when citing.

Additional Resources for Inclusive Citation Practices :

- BIPOC Scientists Citation guide (Rockefeller Univ.).

- Conducting Research through an Anti-Racism Lens (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries).

- cleanBib (Code to probabilistically assign gender and race proportions of first/last authors pairs in bibliography entries).

- Balanced Citer (Python script guesses the race and gender of the first and last authors for papers in your citation list and compares your list to expected distributions based on a model that accounts for paper characteristics).

- Read Black women's work;

- Integrate Black women into the CORE of your syllabus (in life & in the classroom);

- Acknowledge Black women's intellectual production;

- Make space for Black women to speak;

- Give Black women the space and time to breathe.

- CiteASista .

- << Previous: Organize Citations & Search Strategies

- Next: Need More Help? >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:43 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/publichealth/litsearch

The Sheridan Libraries

- Public Health

- Sheridan Libraries

- Literature Reviews + Annotating

- How to Access Full Text

- Background Information

- Books, E-books, Dissertations

- Articles, News, Who Cited This, More

- Google Scholar and Google Books

- PUBMED and EMBASE

- Statistics -- United States

- Statistics -- Worldwide

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- Copyright This link opens in a new window

- Evaluating Information This link opens in a new window

- RefWorks Guide and Help This link opens in a new window

- Epidemic Proportions

- Environment and Your Health, AS 280.335, Spring 2024

- Honors in Public Health, AS280.495, Fall 23-Spr 2024

- Intro to Public Health, AS280.101, Spring 2024

- Research Methods in Public Health, AS280.240, Spring 2024

- Social+Behavioral Determinants of Health, AS280.355, Spring 2024

- Feedback (for class use only)

Literature Reviews

- Organizing/Synthesizing

- Peer Review

- Ulrich's -- One More Way To Find Peer-reviewed Papers

"Literature review," "systematic literature review," "integrative literature review" -- these are terms used in different disciplines for basically the same thing -- a rigorous examination of the scholarly literature about a topic (at different levels of rigor, and with some different emphases).

1. Our library's guide to Writing a Literature Review

2. Other helpful sites

- Writing Center at UNC (Chapel Hill) -- A very good guide about lit reviews and how to write them

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources (LSU, June 2011 but good; PDF) -- Planning, writing, and tips for revising your paper

3. Welch Library's list of the types of expert reviews

Doing a good job of organizing your information makes writing about it a lot easier.

You can organize your sources using a citation manager, such as refworks , or use a matrix (if you only have a few references):.

- Use Google Sheets, Word, Excel, or whatever you prefer to create a table

- The column headings should include the citation information, and the main points that you want to track, as shown

Synthesizing your information is not just summarizing it. Here are processes and examples about how to combine your sources into a good piece of writing:

- Purdue OWL's Synthesizing Sources

- Synthesizing Sources (California State University, Northridge)

Annotated Bibliography

An "annotation" is a note or comment. An "annotated bibliography" is a "list of citations to books, articles, and [other items]. Each citation is followed by a brief...descriptive and evaluative paragraph, [whose purpose is] to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited."*

- Sage Research Methods (database) --> Empirical Research and Writing (ebook) -- Chapter 3: Doing Pre-research

- Purdue's OWL (Online Writing Lab) includes definitions and samples of annotations

- Cornell's guide * to writing annotated bibliographies

* Thank you to Olin Library Reference, Research & Learning Services, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY, USA https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

What does "peer-reviewed" mean?

- If an article has been peer-reviewed before being published, it means that the article has been read by other people in the same field of study ("peers").

- The author's reviewers have commented on the article, not only noting typos and possible errors, but also giving a judgment about whether or not the article should be published by the journal to which it was submitted.

How do I find "peer-reviewed" materials?

- Most of the the research articles in scholarly journals are peer-reviewed.

- Many databases allow you to check a box that says "peer-reviewed," or to see which results in your list of results are from peer-reviewed sources. Some of the databases that provide this are Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts.

What kinds of materials are *not* peer-reviewed?

- open web pages

- most newspapers, newsletters, and news items in journals

- letters to the editor

- press releases

- columns and blogs

- book reviews

- anything in a popular magazine (e.g., Time, Newsweek, Glamour, Men's Health)

If a piece of information wasn't peer-reviewed, does that mean that I can't trust it at all?

No; sometimes you can. For example, the preprints submitted to well-known sites such as arXiv (mainly covering physics) and CiteSeerX (mainly covering computer science) are probably trustworthy, as are the databases and web pages produced by entities such as the National Library of Medicine, the Smithsonian Institution, and the American Cancer Society.

Is this paper peer-reviewed? Ulrichsweb will tell you.

1) On the library home page , choose "Articles and Databases" --> "Databases" --> Ulrichsweb

2) Put in the title of the JOURNAL (not the article), in quotation marks so all the words are next to each other

3) Mouse over the black icon, and you'll see that it means "refereed" (which means peer-reviewed, because it's been looked at by referees or reviewers). This journal is not peer-reviewed, because none of the formats have a black icon next to it:

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: RefWorks Guide and Help >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 6:02 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/public-health

University of Houston Libraries

- Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- Review Comparison Chart

- Decision Tools

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Scoping Review

- Mapping Review

- Integrative Review

- Rapid Review

- Realist Review

- Umbrella Review

- Review of Complex Interventions

- Diagnostic Test Accuracy Review

- Narrative Literature Reviews

- Standards and Guidelines

Navigate the links below to jump to a specific section of the page:

When is a Scoping Review methodology appropriate?

Outline of stages, methods and guidance, examples of scoping reviews, supplementary resources.

According to Colquhoun et al. (2014) , a scoping review can be defined as: "a form of knowledge synthesis, which incorporate a range of study designs to comprehensively summarize and synthesize evidence with the aim of informing practice, programs, and policy and providing direction to future research priorities" (p.1291).

Characteristics

- Answers a broad question

- Scoping reviews serve the purpose of identifying the scope and extent of existing research on a topic

- Similar to systematic reviews, scoping reviews follow a step-by-step process and aim to be transparent and replicable in its methods

When to Use It: A scoping review might be right for you if you are interested in:

- Examining the extent, range, and nature of research activity

- Determining the value of undertaking a full systematic review (e.g. Do any studies exist? Have systematic reviews already been conducted?)

- Summarizing the disseminating research findings

- Identifying gaps in an existing body of literature

The following stages of conducting a review of complex interventions are derived from Peters et al. (2015) and Levac et al. (2010) .

Timeframe: 12+ months, (same amount of time as a systematic review or longer)

*Varies beyond the type of review. Depends on many factors such as but not limited to: resources available, the quantity and quality of the literature, and the expertise or experience of reviewers" ( Grant & Booth, 2009 ).

Question: Answers broader and topic focused questions beyond those relating to the effectiveness of treatments or interventions. A priori review protocol is recommended.

Is your review question a complex intervention? Learn more about Reviews of Complex Interventions .

Sources and searches: Comprehensive search-may be limited by time/scope restraints, still aims to be thorough and repeatable of all literature. May involve multiple structured searches rather than a single structured search. This will produce more results than a systematic review. Must include a modified PRISMA flow diagram.

Selection: Based on inclusion/exclusion criteria, due to the iterative nature of a scoping review some changes may be necessary. May require more time spent screening articles due to the larger volume of results from broader questions.

Appraisal: Critical appraisal (optional), Risk of Bias assessment (optional) is not applicable for scoping reviews.

Synthesis: (Tabular with some narrative) The extraction of data for a scoping review may include a charting table or form but a formal synthesis of findings from individual studies and the generation of a 'summary of findings' (SOF) table is not required. Results may include a logical diagram or table or any descriptive form that aligns with the scope and objectives of the review. May incorporate a numerical summary and qualitative thematic analysis.

Consultation: (optional)

The following resources provide methods and guidance in the field of scoping reviews.

Methods & Guidance

- Cochrane Training: Scoping reviews: what they are and how you can do them A series of videos presented by Dr Andrea C. Tricco and Kafayat Oboirien. Learn the about what a scoping review is, see examples, learn the steps involved, and common methods from Dr. Tricco. Oboirien presents her experiences of conducting a scoping review on strengthening clinical governance in low and middle income countries.

- Current Best Practices for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews by Heather Colquhoun An overview on best practices when executing a scoping review.

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews An extensive and detailed outline within the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis on how to properly conduct a scoping review.

Reporting Guideline

- PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Contains a 20-item checklist for proper reporting of a scoping review plus 2 optional items.

- Håkonsen, S. J., Pedersen, P. U., Bjerrum, M., Bygholm, A., & Peters, M. (2018). Nursing minimum data sets for documenting nutritional care for adults in primary healthcare: a scoping review . JBI database of systematic reviews and implementation reports , 16 (1), 117–139. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003386

- Kao, S. S., Peters, M., Dharmawardana, N., Stew, B., & Ooi, E. H. (2017). Scoping review of pediatric tonsillectomy quality of life assessment instruments . The Laryngoscope , 127 (10), 2399–2406. doi: 10.1002/lary.26522

- Tricco, A. C., Zarin, W., Rios, P., Nincic, V., Khan, P. A., Ghassemi, M., Diaz, S., Pham, B., Straus, S. E., & Langlois, E. V. (2018). Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: a scoping review . Implementation science: IS , 13 (1), 31. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0717-x

Anderson, S., Allen, P., Peckham, S., & Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services . Health research policy and systems , 6 , 7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework . International journal of social research methodology, 8 (1), 19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Armstrong, R., Hall, B. J., Doyle, J., & Waters, E. (2011). Cochrane Update. 'Scoping the scope' of a cochrane review . Journal of public health (Oxford, England) , 33 (1), 147–150. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr015

Colquhoun, H. (2016). Current best practices for the conducting of scoping reviews . Symposium Presentation - Impactful Biomedical Research: Achieving Quality and Transparency . https://www.equator-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Gerstein-Library-scoping-reviews_May-12.pdf

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting . Journal of clinical epidemiology , 67 (12), 1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature . International journal of nursing studies , 46 (10), 1386–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010

Khalil, H., Peters, M., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Soares, C. B., & Parker, D. (2016). An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews . Worldviews on evidence-based nursing , 13 (2), 118–123. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12144

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology . Implementation science: IS , 5 , 69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lockwood, C., Dos Santos, K. B., & Pap, R. (2019). Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: scoping review methods . Asian nursing research , 13 (5), 287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2019.11.002

Morris, M., Boruff, J. T., & Gore, G. C. (2016). Scoping reviews: establishing the role of the librarian . Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA , 104 (4), 346–354. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.4.020

Munn, Z., Peters, M., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach . BMC medical research methodology , 18 (1), 143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Baxter, L., Tricco, A. C., Straus, S., Wickerson, L., Nayar, A., Moher, D., & O'Malley, L. (2016). Advancing scoping study methodology: a web-based survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and methodological steps . BMC health services research , 16 , 305. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1579-z

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews . International journal of evidence-based healthcare , 13 (3), 141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews . In Aromataris, E. & Munn, Z. (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis . Joanna Briggs Institute. doi: 10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Peters, M., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews . JBI evidence implementation , 19 (1), 3–10. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277

Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency . Research synthesis methods , 5 (4), 371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation . Annals of internal medicine , 169 (7), 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Tricco, A., Oboirien, K., Lotfi, T., & Sambunjak, D. (2017, August). Scoping reviews: what they are and how you can do them . Cochrane Training. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/scoping-reviews-what-they-are-and-how-you-can-do-them

- << Previous: Meta-Analysis

- Next: Mapping Review >>

Other Names for a Scoping Review

- Scoping Study

- Systematic Scoping Review

- Scoping Report

- Scope of the Evidence

- Rapid Scoping Review

- Structured Literature Review

- Scoping Project

- Scoping Meta Review

Limitations of a Scoping Review

The following challenges of conducting a scoping review are derived from Grant & Booth (2009) , Peters et al. (2015) , and O'Brien (2016) .

- Is not easier than a systematic review.

- Is not faster than a systematic review; may take longer .

- More citations to screen.

- Different screening criteria/process than a systematic review.

- Often leads to a broader, less defined search.

- Requires multiple structured searches instead of one.

- Increased emphasis for hand searching the literature.

- May require larger teams because of larger volume of literature.

- Inconsistency in the conduct of scoping reviews.

Medical Librarian

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2023 11:14 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uh.edu/reviews

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Subject Research

- Public Health

- Literature reviews

Public Health: Literature reviews

Created by health science librarians.

- Sciwheel & Citation managers

- Data & software

- Grey literature

- Popular search strategies

Section Objective

What is a literature review, clearly stated research question, search terms, searching worksheets, boolean and / or.

- Systematic reviews

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Sciences and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Behavior

- Health Policy and Management

- Maternal and Child Health

- Public Health Leadership

The content in the Literature Review section defines the literature review purpose and process, explains using the PICO format to ask a clear research question, and demonstrates how to evaluate and modify search results to improve the accuracy of the retrieval.

A literature review seeks to identify, analyze and summarize the published research literature about a specific topic. Literature reviews are assigned as course projects; included as the introductory part of master's and PhD theses; and are conducted before undertaking any new scientific research project.

The purpose of a literature review is to establish what is currently known about a specific topic and to evaluate the strength of the evidence upon which that knowledge is based. A review of a clinical topic may identify implications for clinical practice. Literature reviews also identify areas of a topic that need further research.

A systematic review is a literature review that follows a rigorous process to find all of the research conducted on a topic and then critically appraises the research methods of the highest quality reports. These reviews track and report their search and appraisal methods in addition to providing a summary of the knowledge established by the appraised research.

The UNC Writing Center provides a nice summary of what to consider when writing a literature review for a class assignment. The online book, Doing a literature review in health and social care : a practical guide (2010), is a good resource for more information on this topic.

Obviously, the quality of the search process will determine the quality of all literature reviews. Anyone undertaking a literature review on a new topic would benefit from meeting with a librarian to discuss search strategies. A consultaiton with a librarian is strongly recommended for anyone undertaking a systematic review.

Use the email form on our Ask a Librarian page to arrange a meeting with a librarian.

The first step to a successful literature review search is to state your research question as clearly as possible.

It is important to:

- be as specific as possible

- include all aspects of your question

Clinical and social science questions often have these aspects (PICO):

- People/population/problem (What are the characteristics of the population? What is the condition or disease?)

- Intervention (What do you want to do with this patient? i.e. treat, diagnose)

- Comparisons [not always included] (What is the alternative to this intervention? i.e. placebo, different drug, surgery)

- Outcomes (What are the relevant outcomes? i.e. morbidity, death, complications)

If the PICO model does not fit your question, try to use other ways to help be sure to articulate all parts of your question. Perhaps asking yourself Who, What, Why, How will help.

Example Question: Is acupuncture as effective of a therapy as triptans in the treament of adult migraine?

Note that this question fits the PICO model.

- Population: Adults with migraines

- Intervention: Acupuncture

- Comparison: Triptans/tryptamines

- Outcome: Fewer Headache days, Fewer migraines

A literature review search is an iterative process. Your goal is to find all of the articles that are pertinent to your subject. Successful searching requires you to think about the complexity of language. You need to match the words you use in your search to the words used by article authors and database indexers. A thorough PubMed search must identify the author words likely to be in the title and abstract or the indexer's selected MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) Terms.

Start by doing a preliminary search using the words from the key parts of your research question.

Step #1: Initial Search

Enter the key concepts from your research question combined with the Boolean operator AND. PubMed does automatically combine your terms with AND. However, it can be easier to modify your search if you start by including the Boolean operators.

migraine AND acupuncture AND tryptamines

The search retrieves a number of relevant article records, but probably not everything on the topic.

Step #2: Evaluate Results

Use the Display Settings drop down in the upper left hand corner of the results page to change to Abstract display.

Review the results and move articles that are directly related to your topic to the Clipboard .

Go to the Clipboard to examine the language in the articles that are directly related to your topic.

- look for words in the titles and abstracts of these pertinent articles that differ from the words you used

- look for relevant MeSH terms in the list linked at the bottom of each article

The following two articles were selected from the search results and placed on the Clipboard.

Here are word differences to consider:

- Initial search used acupuncture. MeSH Terms use Acupuncture therapy.

- Initial search used migraine. Related word from MeSH Terms is Migraine without Aura and Migraine Disorders.

- Initial search used tryptamines. Article title uses sumatriptan. Related word from MeSH is Sumatriptan or Tryptamines.

With this knowledge you can reformulate your search to expand your retrieval, adding synonyms for all concepts except for manual and plaque.

#3 Revise Search

Use the Boolean OR operator to group synonyms together and use parentheses around the OR groups so they will be searched properly. See the image below to review the difference between Boolean OR / Boolean AND.

Here is what the new search looks like:

(migraine OR migraine disorders) AND (acupuncture OR acupuncture therapy) AND (tryptamines OR sumatriptan)

- Search Worksheet Example: Acupuncture vs. Triptans for Migraine

- Search Worksheet

- << Previous: Popular search strategies

- Next: Systematic reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 5:39 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/publichealth

Search & Find

- E-Research by Discipline

- More Search & Find

Places & Spaces

- Places to Study

- Book a Study Room

- Printers, Scanners, & Computers

- More Places & Spaces

- Borrowing & Circulation

- Request a Title for Purchase

- Schedule Instruction Session

- More Services

Support & Guides

- Course Reserves

- Research Guides

- Citing & Writing

- More Support & Guides

- Mission Statement

- Diversity Statement

- Staff Directory

- Job Opportunities

- Give to the Libraries

- News & Exhibits

- Reckoning Initiative

- More About Us

- Search This Site

- Privacy Policy

- Accessibility

- Give Us Your Feedback

- 208 Raleigh Street CB #3916

- Chapel Hill, NC 27515-8890

- 919-962-1053

Starting Monday 5/13/24, CCNY Libraries will return to regular hours. Access is limited to CCNY ID holders only. Library services are available online, including research help and InterLibrary Loan .

Public health: literature reviews.

- Databases and Journals

- Search Tips

- Citation Management

- Data, Statistics, and Grey Literature

- Inter-Library Loan (ILL) & CLICS

- Literature Reviews

- Dissertation Deposit

- Finding and Publishing Research at SPH

- Nutrition Care Manual

- AI Resources

What is a Systematic Literature Review?

If you are doing a literature review as part of your capstone project, please see this document for guidance on format and structure.

What is a literature review?

There are different types of literature reviews, for an overview on the differences between them please see this page . This page's main focus is systematic literature reviews -- please scroll down to find resources for doing scoping reviews .

At its most basic, a systematic review is a secondary study that summarizes research on a specific topic by means of explicit and rigorous methods. These are based on previously published works in the field and do not include new data or experiments.

Systematic reviews use a formal process to identify , select , appraise , analyze , and summarize the findings.

Try starting out by formulating and defining a clear, specific research question. The PICO Framework (standing for Population/problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) is a guideline for focusing and answering health-related questions, and a well-formed clinical question covers these areas:

Developing a Protocol

What is a literature review protocol? Essentially, it is a document prepared before a review is started that serves as a guide to carrying it out. It describes the rationale, hypothesis, and planned methods of the review. The protocol should contain specific guidelines to identify and screen relevant articles for the review as well as outline the review methods for the entire process.

Why make a protocol for your literature review?

The key elements of a protocol are:

1 . Background/purpose

2 . Objectives/review question

3 . Methods

a . Selection criteria (such as: type of intervention, type of outcome, population of studies, types of studies, types of publications, publication dates, language, and location)

b . Search Strategy

c . Data Collection

d . Displaying data

e . Analysis and synthesis

A good way to develop a protocol is to use PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). PRISMA is a set of reporting standards for sharing your findings with the research community.

Use the PRISMA checklist and the PRISMA flow chart to help make sure your review is as thorough as possible.

See the full PRISMA statement here .

Below are some examples and templates for review protocols.

Protocol template from the World Health Organization

Protocol template from Cochrane

Protocol guidelines from the Campbell Collaboration

Search Strategy & Screening Tools

Free search strategy tools.

- citationchaser Takes a starting set of articles and finds all of the articles that these records cite (their references), and all of the articles that cite them.

- MeSH on Demand Identifies MeSH terms in submitted text & lists related Pubmed articles.

- Pubmed PubReMiner Provides detailed analysis of PubMed Search results.

- Yale MeSH Analyzer Extracts indexing information from MEDLINE articles to allow users to visually scan and compare key metadata.

Free screening tools.

- Abstrackr Citation screening software created by Brown's Center for Evidence Synthesis in Health.

- Abstrackr Tutorial

- ASReview ASReview LAB is a free open-source machine learning tool for screening and systematically labeling a large collection of textual data.

- ASReview Tutorials

- Colandr Free, web-based, open-access tool for conducting evidence synthesis projects.

- Colandr Tutorial

- Rayyan Rayyan is a web-tool designed to help researchers working on systematic reviews, scoping reviews and other knowledge synthesis projects, by dramatically speeding up the process of screening and selecting studies.

- Rayyan Tutorial

- Systematic Review Data Repository SRDR+ is a free tool for data extraction, management, and archiving during systematic reviews.

- SRDR+ Tutorials

- PRISMA Statement

- PRISMA-Equity Extension

- STROBE statement

- Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews

- Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review

- Guide for Developing a Protocol for Conducting Literature Reviews

- Summarizing and Synthesizing with a Literature Matrix

- What is a Systematic Literature Review and how do I do one?

Scoping Reviews

A scoping review is a type of knowledge synthesis that uses a systematic and iterative approach to identify and synthesize an existing or emerging body of literature on a given topic. While there are several reasons for conducting a scoping review, the main reasons are to map the extent, range, and nature of the literature, as well as to determine possible gaps in the literature on a topic. Scoping reviews are not limited to peer-reviewed literature.

Mak S, Thomas A. Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. J Grad Med Educ . 2022;14(5):565-567. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews JBI, formerly known as the Joanna Briggs Institute, is an international research organization which develops and delivers evidence-based information, software, education and training.

- PCC Question Outline The PCC Question outline helps frame the scoping review question and highlights important concepts for the literature search. From the Bernard Beck Medical Library at Washington U. St. Louis.

- PRISMA-ScR This checklist contains 20 essential reporting items and 2 optional items to include when completing a scoping review.

- Scoping Reviews: what they are & how you can do them Five videos featuring Dr Andrea C. Tricco presenting the definition of a scoping review, examples of scoping reviews, steps of the scoping review process, and methods used.

- Scoping Review Guide SUNY Stony Brook University's Scoping Review Guide covers information you need to know to prepare for and conduct a scoping review.

Peters, M.D.J., Marnie, C., Colquhoun, H. et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev 10 , 263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine . 2018;169(7):467-473. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

- << Previous: Inter-Library Loan (ILL) & CLICS

- Next: Dissertation Deposit >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 2:07 PM

- URL: https://library.ccny.cuny.edu/PublicHealth

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Bashir Y, Conlon KC. Step by step guide to do a systematic review and meta-analysis for medical professionals. Ir J Med Sci. 2018; 187:(2)447-452 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-017-1663-3

Bettany-Saltikov J. How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: a step-by-step guide.Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2012

Bowers D, House A, Owens D. Getting started in health research.Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011

Hierarchies of evidence. 2016. http://cjblunt.com/hierarchies-evidence (accessed 23 July 2019)

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2008; 3:(2)37-41 https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Developing a framework for critiquing health research. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/y3nulqms (accessed 22 July 2019)

Cognetti G, Grossi L, Lucon A, Solimini R. Information retrieval for the Cochrane systematic reviews: the case of breast cancer surgery. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015; 51:(1)34-39 https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_15_01_07

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006; 6:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-6-35

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC Users' guides to the medical literature IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. JAMA. 1995; 274:(22)1800-1804 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530220066035

Hanley T, Cutts LA. What is a systematic review? Counselling Psychology Review. 2013; 28:(4)3-6

Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org (accessed 23 July 2019)

Jahan N, Naveed S, Zeshan M, Tahir MA. How to conduct a systematic review: a narrative literature review. Cureus. 2016; 8:(11) https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.864

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1997; 33:(1)159-174

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009; 6:(7) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mueller J, Jay C, Harper S, Davies A, Vega J, Todd C. Web use for symptom appraisal of physical health conditions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19:(6) https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6755

Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016; 21:(4)125-127 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance. 2012. http://nice.org.uk/process/pmg4 (accessed 22 July 2019)

Sambunjak D, Franic M. Steps in the undertaking of a systematic review in orthopaedic surgery. Int Orthop. 2012; 36:(3)477-484 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1460-y

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019; 70:747-770 https://doi.org/0.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008; 8:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Wallace J, Nwosu B, Clarke M. Barriers to the uptake of evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a systematic review of decision makers' perceptions. BMJ Open. 2012; 2:(5) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001220

Carrying out systematic literature reviews: an introduction

Alan Davies

Lecturer in Health Data Science, School of Health Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester

View articles · Email Alan

Systematic reviews provide a synthesis of evidence for a specific topic of interest, summarising the results of multiple studies to aid in clinical decisions and resource allocation. They remain among the best forms of evidence, and reduce the bias inherent in other methods. A solid understanding of the systematic review process can be of benefit to nurses that carry out such reviews, and for those who make decisions based on them. An overview of the main steps involved in carrying out a systematic review is presented, including some of the common tools and frameworks utilised in this area. This should provide a good starting point for those that are considering embarking on such work, and to aid readers of such reviews in their understanding of the main review components, in order to appraise the quality of a review that may be used to inform subsequent clinical decision making.

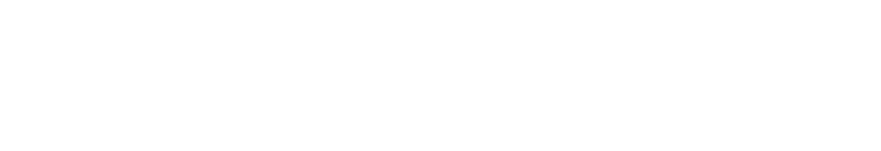

Since their inception in the late 1970s, systematic reviews have gained influence in the health professions ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered to be the most credible and authoritative sources of evidence available ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ) and are regarded as the pinnacle of evidence in the various ‘hierarchies of evidence’. Reviews published in the Cochrane Library ( https://www.cochranelibrary.com) are widely considered to be the ‘gold’ standard. Since Guyatt et al (1995) presented a users' guide to medical literature for the Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group, various hierarchies of evidence have been proposed. Figure 1 illustrates an example.

Systematic reviews can be qualitative or quantitative. One of the criticisms levelled at hierarchies such as these is that qualitative research is often positioned towards or even is at the bottom of the pyramid, thus implying that it is of little evidential value. This may be because of traditional issues concerning the quality of some qualitative work, although it is now widely recognised that both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies have a valuable part to play in answering research questions, which is reflected by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) information concerning methods for developing public health guidance. The NICE (2012) guidance highlights how both qualitative and quantitative study designs can be used to answer different research questions. In a revised version of the hierarchy-of-evidence pyramid, the systematic review is considered as the lens through which the evidence is viewed, rather than being at the top of the pyramid ( Murad et al, 2016 ).

Both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies are sometimes combined in a single review. According to the Cochrane review handbook ( Higgins and Green, 2011 ), regardless of type, reviews should contain certain features, including:

- Clearly stated objectives

- Predefined eligibility criteria for inclusion or exclusion of studies in the review

- A reproducible and clearly stated methodology

- Validity assessment of included studies (eg quality, risk, bias etc).

The main stages of carrying out a systematic review are summarised in Box 1 .

Formulating the research question

Before undertaking a systemic review, a research question should first be formulated ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). There are a number of tools/frameworks ( Table 1 ) to support this process, including the PICO/PICOS, PEO and SPIDER criteria ( Bowers et al, 2011 ). These frameworks are designed to help break down the question into relevant subcomponents and map them to concepts, in order to derive a formalised search criterion ( Methley et al, 2014 ). This stage is essential for finding literature relevant to the question ( Jahan et al, 2016 ).

It is advisable to first check that the review you plan to carry out has not already been undertaken. You can optionally register your review with an international register of prospective reviews called PROSPERO, although this is not essential for publication. This is done to help you and others to locate work and see what reviews have already been carried out in the same area. It also prevents needless duplication and instead encourages building on existing work ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ).

A study ( Methley et al, 2014 ) that compared PICO, PICOS and SPIDER in relation to sensitivity and specificity recommended that the PICO tool be used for a comprehensive search and the PICOS tool when time/resources are limited.

The use of the SPIDER tool was not recommended due to the risk of missing relevant papers. It was, however, found to increase specificity.

These tools/frameworks can help those carrying out reviews to structure research questions and define key concepts in order to efficiently identify relevant literature and summarise the main objective of the review ( Jahan et al, 2016 ). A possible research question could be: Is paracetamol of benefit to people who have just had an operation? The following examples highlight how using a framework may help to refine the question:

- What form of paracetamol? (eg, oral/intravenous/suppository)

- Is the dosage important?

- What is the patient population? (eg, children, adults, Europeans)

- What type of operation? (eg, tonsillectomy, appendectomy)

- What does benefit mean? (eg, reduce post-operative pyrexia, analgesia).

An example of a more refined research question could be: Is oral paracetamol effective in reducing pain following cardiac surgery for adult patients? A number of concepts for each element will need to be specified. There will also be a number of synonyms for these concepts ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 shows an example of concepts used to define a search strategy using the PICO statement. It is easy to see even with this dummy example that there are many concepts that require mapping and much thought required to capture ‘good’ search criteria. Consideration should be given to the various terms to describe the heart, such as cardiac, cardiothoracic, myocardial, myocardium, etc, and the different names used for drugs, such as the equivalent name used for paracetamol in other countries and regions, as well as the various brand names. Defining good search criteria is an important skill that requires a lot of practice. A high-quality review gives details of the search criteria that enables the reader to understand how the authors came up with the criteria. A specific, well-defined search criterion also aids in the reproducibility of a review.

Search criteria

Before the search for papers and other documents can begin it is important to explicitly define the eligibility criteria to determine whether a source is relevant to the review ( Hanley and Cutts, 2013 ). There are a number of database sources that are searched for medical/health literature including those shown in Table 3 .

The various databases can be searched using common Boolean operators to combine or exclude search terms (ie AND, OR, NOT) ( Figure 2 ).

Although most literature databases use similar operators, it is necessary to view the individual database guides, because there are key differences between some of them. Table 4 details some of the common operators and wildcards used in the databases for searching. When developing a search criteria, it is a good idea to check concepts against synonyms, as well as abbreviations, acronyms and plural and singular variations ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Reading some key papers in the area and paying attention to the key words they use and other terms used in the abstract, and looking through the reference lists/bibliographies of papers, can also help to ensure that you incorporate relevant terms. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) that are used by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) ( https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html) to provide hierarchical biomedical index terms for NLM databases (Medline and PubMed) should also be explored and included in relevant search strategies.

Searching the ‘grey literature’ is also an important factor in reducing publication bias. It is often the case that only studies with positive results and statistical significance are published. This creates a certain bias inherent in the published literature. This bias can, to some degree, be mitigated by the inclusion of results from the so-called grey literature, including unpublished work, abstracts, conference proceedings and PhD theses ( Higgins and Green, 2011 ; Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Biases in a systematic review can lead to overestimating or underestimating the results ( Jahan et al, 2016 ).

An example search strategy from a published review looking at web use for the appraisal of physical health conditions can be seen in Box 2 . High-quality reviews usually detail which databases were searched and the number of items retrieved from each.

A balance between high recall and high precision is often required in order to produce the best results. An oversensitive search, or one prone to including too much noise, can mean missing important studies or producing too many search results ( Cognetti et al, 2015 ). Following a search, the exported citations can be added to citation management software (such as Mendeley or Endnote) and duplicates removed.

Title and abstract screening

Initial screening begins with the title and abstracts of articles being read and included or excluded from the review based on their relevance. This is usually carried out by at least two researchers to reduce bias ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). After screening any discrepancies in agreement should be resolved by discussion, or by an additional researcher casting the deciding vote ( Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ). Statistics for inter-rater reliability exist and can be reported, such as percentage of agreement or Cohen's kappa ( Box 3 ) for two reviewers and Fleiss' kappa for more than two reviewers. Agreement can depend on the background and knowledge of the researchers and the clarity of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This highlights the importance of providing clear, well-defined criteria for inclusion that are easy for other researchers to follow.

Full-text review

Following title and abstract screening, the remaining articles/sources are screened in the same way, but this time the full texts are read in their entirety and included or excluded based on their relevance. Reasons for exclusion are usually recorded and reported. Extraction of the specific details of the studies can begin once the final set of papers is determined.

Data extraction

At this stage, the full-text papers are read and compared against the inclusion criteria of the review. Data extraction sheets are forms that are created to extract specific data about a study (12 Jahan et al, 2016 ) and ensure that data are extracted in a uniform and structured manner. Extraction sheets can differ between quantitative and qualitative reviews. For quantitative reviews they normally include details of the study's population, design, sample size, intervention, comparisons and outcomes ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Mueller et al, 2017 ).

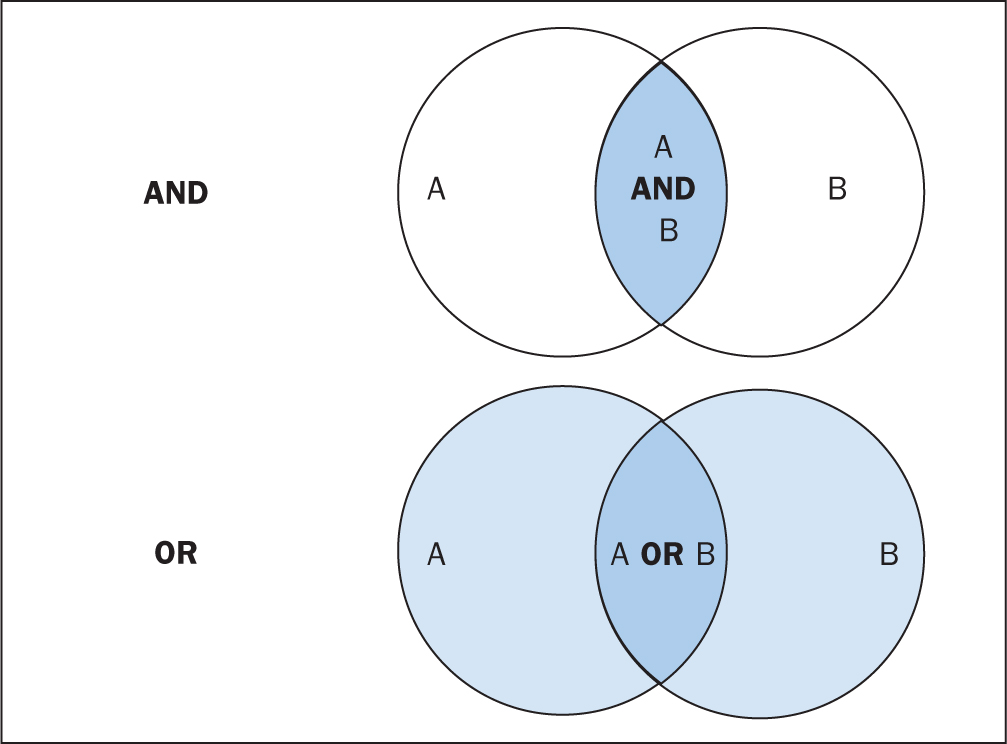

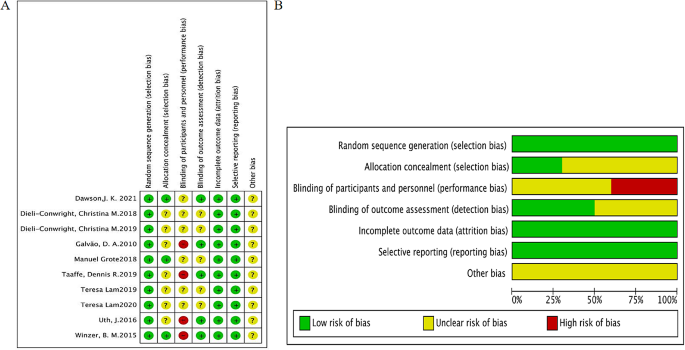

Quality appraisal

The quality of the studies used in the review should also be appraised. Caldwell et al (2005) discussed the need for a health research evaluation framework that could be used to evaluate both qualitative and quantitative work. The framework produced uses features common to both research methodologies, as well as those that differ ( Caldwell et al, 2005 ; Dixon-Woods et al, 2006 ). Figure 3 details the research critique framework. Other quality appraisal methods do exist, such as those presented in Box 4 . Quality appraisal can also be used to weight the evidence from studies. For example, more emphasis can be placed on the results of large randomised controlled trials (RCT) than one with a small sample size. The quality of a review can also be used as a factor for exclusion and can be specified in inclusion/exclusion criteria. Quality appraisal is an important step that needs to be undertaken before conclusions about the body of evidence can be made ( Sambunjak and Franic, 2012 ). It is also important to note that there is a difference between the quality of the research carried out in the studies and the quality of how those studies were reported ( Sambunjak and Franic, 2012 ).

The quality appraisal is different for qualitative and quantitative studies. With quantitative studies this usually focuses on their internal and external validity, such as how well the study has been designed and analysed, and the generalisability of its findings. Qualitative work, on the other hand, is often evaluated in terms of trustworthiness and authenticity, as well as how transferable the findings may be ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ; Bashir and Conlon, 2018 ; Siddaway et al, 2019 ).

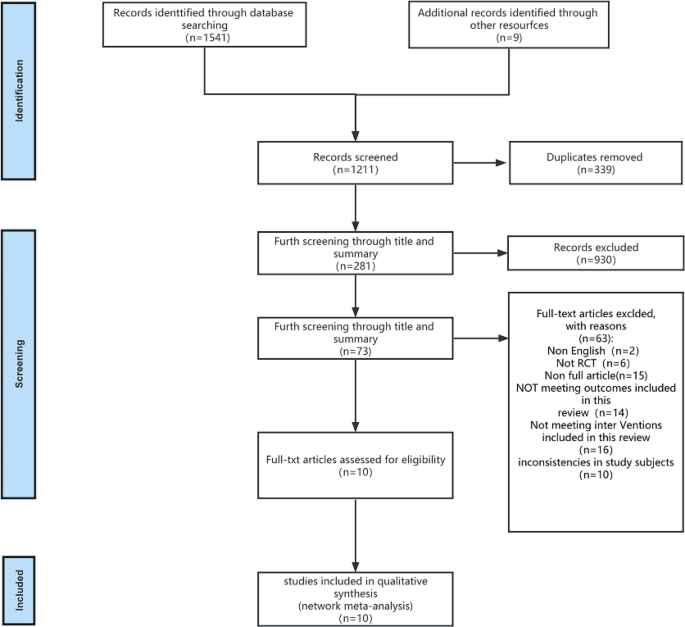

Reporting a review (the PRISMA statement)

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) provides a reporting structure for systematic reviews/meta-analysis, and consists of a checklist and diagram ( Figure 4 ). The stages of identifying potential papers/sources, screening by title and abstract, determining eligibility and final inclusion are detailed with the number of articles included/excluded at each stage. PRISMA diagrams are often included in systematic reviews to detail the number of papers included at each of the four main stages (identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion) of the review.

Data synthesis

The combined results of the screened studies can be analysed qualitatively by grouping them together under themes and subthemes, often referred to as meta-synthesis or meta-ethnography ( Siddaway et al, 2019 ). Sometimes this is not done and a summary of the literature found is presented instead. When the findings are synthesised, they are usually grouped into themes that were derived by noting commonality among the studies included. Inductive (bottom-up) thematic analysis is frequently used for such purposes and works by identifying themes (essentially repeating patterns) in the data, and can include a set of higher-level and related subthemes (Braun and Clarke, 2012). Thomas and Harden (2008) provide examples of the use of thematic synthesis in systematic reviews, and there is an excellent introduction to thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2012).

The results of the review should contain details on the search strategy used (including search terms), the databases searched (and the number of items retrieved), summaries of the studies included and an overall synthesis of the results ( Bettany-Saltikov, 2012 ). Finally, conclusions should be made about the results and the limitations of the studies included ( Jahan et al, 2016 ). Another method for synthesising data in a systematic review is a meta-analysis.

Limitations of systematic reviews

Apart from the many advantages and benefits to carrying out systematic reviews highlighted throughout this article, there remain a number of disadvantages. These include the fact that not all stages of the review process are followed rigorously or even at all in some cases. This can lead to poor quality reviews that are difficult or impossible to replicate. There also exist some barriers to the use of evidence produced by reviews, including ( Wallace et al, 2012 ):

- Lack of awareness and familiarity with reviews

- Lack of access

- Lack of direct usefulness/applicability.

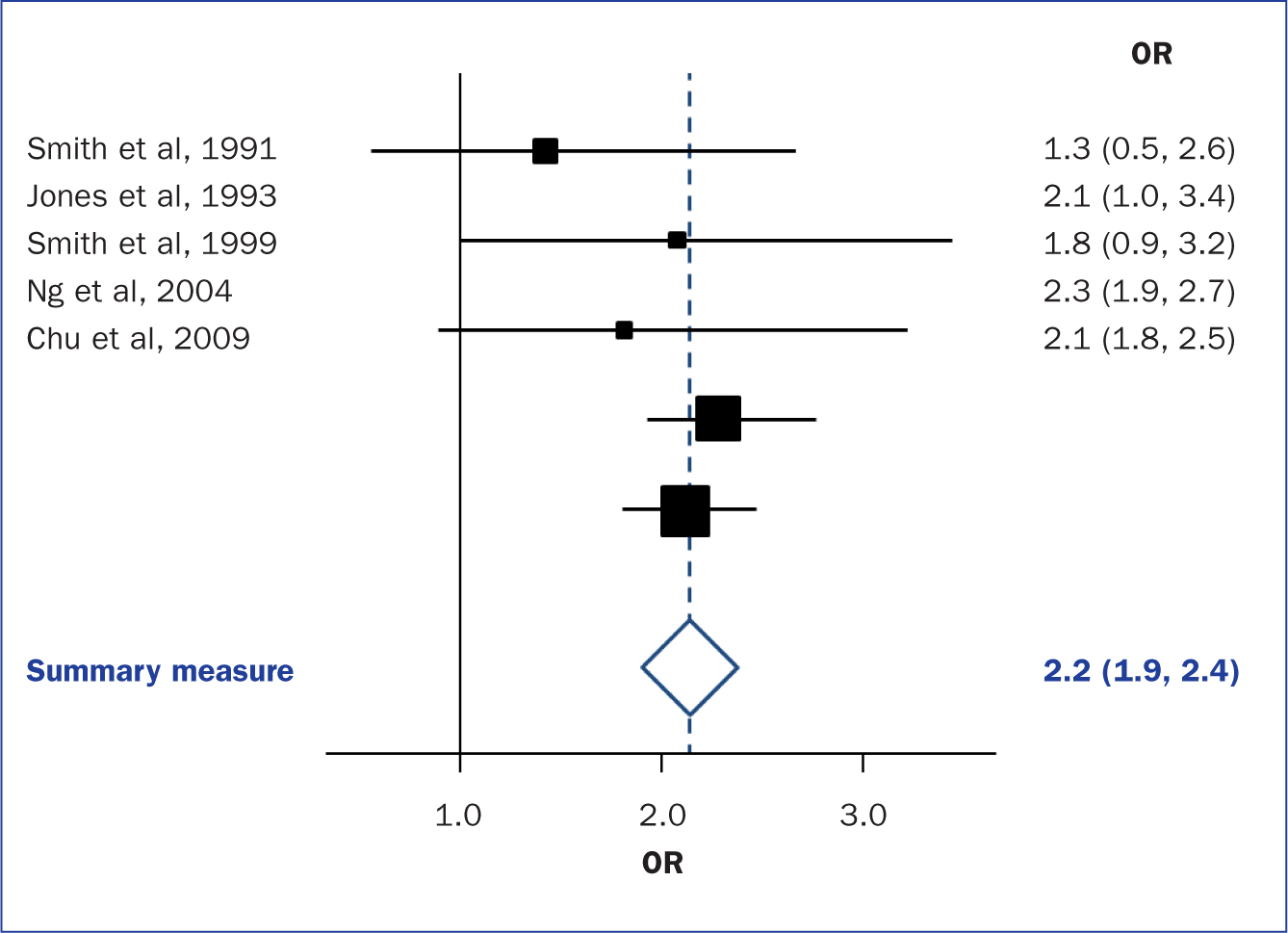

Meta-analysis

When the methods used and the analysis are similar or the same, such as in some RCTs, the results can be synthesised using a statistical approach called meta-analysis and presented using summary visualisations such as forest plots (or blobbograms) ( Figure 5 ). This can be done only if the results can be combined in a meaningful way.

Meta-analysis can be carried out using common statistical and data science software, such as the cross-platform ‘R’ ( https://www.r-project.org), or by using standalone software, such as Review Manager (RevMan) produced by the Cochrane community ( https://tinyurl.com/revman-5), which is currently developing a cross-platform version RevMan Web.

Carrying out a systematic review is a time-consuming process, that on average takes between 6 and 18 months and requires skill from those involved. Ideally, several reviewers will work on a review to reduce bias. Experts such as librarians should be consulted and included where possible in review teams to leverage their expertise.

Systematic reviews should present the state of the art (most recent/up-to-date developments) concerning a specific topic and aim to be systematic and reproducible. Reproducibility is aided by transparent reporting of the various stages of a review using reporting frameworks such as PRISMA for standardisation. A high-quality review should present a summary of a specific topic to a high standard upon which other professionals can base subsequent care decisions that increase the quality of evidence-based clinical practice.

- Systematic reviews remain one of the most trusted sources of high-quality information from which to make clinical decisions

- Understanding the components of a review will help practitioners to better assess their quality

- Many formal frameworks exist to help structure and report reviews, the use of which is recommended for reproducibility

- Experts such as librarians can be included in the review team to help with the review process and improve its quality

CPD reflective questions

- Where should high-quality qualitative research sit regarding the hierarchies of evidence?

- What background and expertise should those conducting a systematic review have, and who should ideally be included in the team?

- Consider to what extent inter-rater agreement is important in the screening process

Usman Iqbal 2024 Convocation Alumni Speaker

A Letter to Our Graduates, the Class of 2024

Literature reviews ..

A literature review is systematic examination of existing research on a proposed topic (1). Public health professionals often consult literature reviews to stay up-to-date on research in their field (1–3). Researchers also frequently use literature reviews as a way to identify gaps in the research and provide a background for continuing research on a topic (1,2). This section will provide an overview of the essential elements needed to write a successful literature review.

Collecting Articles

A literature review is systematic examination of existing research on a proposed topic (1). Public health professionals often consult literature reviews to stay up-to-date on research in their field (1–3). Researchers also frequently use literature reviews as a way to identify gaps in the research and provide a background for continuing research on a topic (1,2). This section will provide an overview of the essential elements needed to write a successful literature review.

Do not hesitate to reach out to a reference librarian at the BUMC Alumni Medical Library for assistance in collecting your research.

Reviewing the Research

After selecting the articles for your review, read each article and takes notes to keep track of each paper (3). One way to effectively take notes is to create a table listing each article’s research question, methods, results, limitations, etc. Once you have finished reading the articles, critically think about why each one is important to your discussion (1,2,4). Try to group articles based on similar content, such as similar study populations, methods, or results (4). Most literature reviews do not require you to organize your articles in a certain manner; however, you should think about how you would logically tie your articles together so that you are analyzing them, not simply summarizing each article (4).

Organizing your Review

While there is no standard organization for a literature review, literature reviews generally follow this structure (1,3):

- Introduction. The introduction should identify a research question and relate it to a public health topic. The significance of the public health problem and topic should be described.

- Body. The body of a literature review should be organized so that the review flows logical from one subtopic to another subtopic. Consider breaking this section into the following sections:

- Methods. Describe how you obtained your articles. Be sure to include the names of search engines and key words used to generate searches. Detail your inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e. did not fit your definition of your outcome). Consider creating a flow chart to illustrate your search process.

- Results/Discussion. Explain what the literature says about your question. What did the studies find? Is their conflicting evidence? What are the limitations of the current studies? What gaps exist in the literature? What are the outstanding research questions? A table of your studies can be a great tool to summarize of the essential information.

- Conclusion. Review your findings and how they relate to your research questions. Use this space to propose needs in the research, if appropriate.