Behavioral Learning Theory: Shaping Students’ Behavior and Learning

The Behavioral Learning Theory gives us insight into how to create a positive learning environment, influence our students’ behavior in class, and motivate them to develop good study habits.

- By Paul Holt

- Sep 20, 2023

E-student.org is supported by our community of learners. When you visit links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

- The Behavioral Learning Theory is based on the premise that all human behavior is learned.

- According to this theory, our behaviors are simply reactions to external stimuli, and we can learn new behaviors through a process called conditioning.

- When applied correctly, Behaviorism can be an effective tool for helping students perform better in class and allow them to develop self-regulating skills.

We all know not to touch something hot because it can burn. This is a lesson that we’ve learned based on experience. It’s nothing new, right? Experience does teach us a lot of things. According to the Behavioral Learning Theory, this is, in fact, how all humans and animals learn.

The Behavioral Learning Theory , also known as Behaviorism, is based on the idea that we learn through our interaction with the environment. In fact, one of its assumptions is that all behavior can be learned. Moreover, behaviors can be replaced by new behaviors through a process called conditioning.

As teachers, understanding the Behavioral Learning Theory can teach you how to encourage your students to learn and create an environment that’s more stimulating and conducive to learning. In this article, we’ll discuss the Behavioral Learning Theory, its benefits, and how educators can use it in the classroom to help students achieve academic success.

Table of Contents

What is behavioral learning theory.

Behaviorism was first introduced in the 19th century as a reaction against mentalism . At the time, the study of the mind mostly relied on first-person accounts of people’s thoughts and feelings. Some psychologists didn’t think that unconscious thoughts and urges were objective or measurable. It was too subjective, which could lead to findings that were contradicting. Worse, they might not even be able to reproduce the same results.

Behavior, on the other hand, could be observed objectively, systematically studied, and empirically measured. Moreover, behaviorists believe that people can be trained to perform any task regardless of their genetic background or personality as long as you apply the right conditioning. In layman’s terms, we’re all blank slates when we’re born. And all our behavior is learned from our interaction with our environment.

Types of Behavioral Learning

Classical conditioning.

According to Classical Conditioning, a human or animal can learn new behavior by associating a neutral stimulus with another stimulus that causes a natural response. Once associated, the neutral stimulus can now trigger the learned response.

To explain this more clearly, let’s look at an experiment conducted by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov . You’ve heard of Pavlov’s dogs, right? In his experiments, he was able to teach dogs to associate the ringing of a bell (a neutral stimulus) with the arrival of food (the second stimulus). The smell of the food automatically triggers the dogs’ hunger, which includes physical signs such as salivation. Through conditioning, just hearing the ringing of the bell could cause the dogs to salivate, even if they no longer smelled the food.

Operant Conditioning

Most of us are very familiar with Operant Conditioning because this learning technique is based on the idea of reward and punishment. According to Operant Conditioning, consequences can control the behavior of an individual. A behavior is more likely to occur if the person knows that they’ll get something good out of it. It is less likely to occur if the person knows they’ll get punished.

Operant conditioning can be done using positive and negative reinforcement and positive and negative punishment:

Positive reinforcement: The presence of an added stimulus after you get the desired behavior can increase the likelihood of the individual repeating the behavior or, to put it more simply, giving a person something good to reinforce the behavior. For example, the teacher gives preschool kids a stamp if they are on good behavior in class at the end of the day. This makes them more likely to behave during class on the following days.

Negative reinforcement: Taking away something unpleasant after the desired behavior takes place. Over time, the desired behavior occurs more often with the expectation that the negative stimuli will be removed. For example, the beeping sound you hear when you don’t put on your seatbelt. We are motivated to put on our seatbelt quickly to stop the annoying beeps.

Positive punishment: Adding an undesirable stimulus after a behavior to discourage it from occurring in the future. For example, a student will get detention for misbehaving in class.

Negative punishment: Removing a positive stimulus after a behavior to discourage the person from doing it again. For example, removing a child’s internet privileges if he doesn’t do his homework.

Benefits of Behavioral Learning Theory in teaching

Understanding and harnessing the Behavioral Learning Theory can be an effective tool for influencing students to learn positive behaviors and discourage negative behaviors. Students can learn to work for rewards, including approval.

Benefits to using behaviorism in the classroom include:

- Behaviorism helps create a structured learning environment. Students are taught how to obey the rules inside the classroom, whether online or in person, through rewards and punishments. This helps create a more organized and disciplined environment that is conducive to learning.

- It can help give teachers a clear and objective structure for measuring a student’s performance.

- It provides students with immediate feedback, which can improve learning. For example, positive reinforcement has been shown to help students retain information better.

- Behaviorism can be used to shape a student’s study strategies.

- It can help teachers adapt their teaching techniques according to the abilities and needs of each student.

- It can teach students how to self-regulate. They gain an understanding of their behavior and motivations, allowing them to have more control over how they act. More importantly, it teaches them to become accountable for what they do.

How to apply the Behavioral Learning Theory in the online classroom

We’ve all experienced positive and negative reinforcement as well as positive and negative punishment in the classroom. These include:

- Getting praised by the teacher for a correct response to a question.

- Receiving a bonus to your grade if you have a perfect attendance record.

- Getting a grade of “0” for not submitting assignments.

- Getting your phone confiscated if you use it in class.

- Getting a free homework pass if you get a perfect grade on the exam.

In addition to the ideas mentioned above, below are several strategies that can be applied to the online and physical classrooms:

Set clear expectations . Students need to have a clear understanding of the goals they need to achieve and the rules they need to follow in the classroom. This is especially important for online classrooms. Many students might not take online classes as seriously as classes held face-to-face in school. Make sure that your students understand your expectations during the online class and enforce the rules consistently.

Provide regular reviews. Going over the same material while providing your students with positive reinforcement can enable them to retain information better.

Give quick feedback. It’s important that students are provided feedback in a timely manner so they will associate it with the work they did. This helps shape your student’s study habits more effectively.

Reward good study habits. You need to help prevent students from cramming. Create a reward system that motivates them to regularly study the class materials. With the proper incentive, they’ll begin to associate regular study sessions with good feelings.

Provide guided practice. You can demonstrate the behavior that you want them to follow. For example, be directly involved in helping them solve a problem step-by-step and providing them reinforcement along the way.

Use negative reinforcement sparingly. Avoid too much negative reinforcement to prevent creating a negative atmosphere in the class.

Use game-based learning. Game-based learning can increase engagement and motivate students to learn. There are many online games that utilize the principles of Operant Conditioning to promote learning, such as FunBrain , Moose Math , and RoomRecess . Alternatively, you can create a token economy system. Students can earn tokens or points for certain behaviors or for accomplishing specific tasks. These tokens can be exchanged for rewards, which can incentivize them to follow the rules and stay on task.

The Behavioral Learning Theory teaches us how external stimuli can influence behavior and learning. As educators, we need to try to find different ways to elicit positive behaviors from our students and discourage negative responses. We need to be more aware of their needs and motivations so that we are able to create more positive learning environments and increase their motivation to learn.

Jigsaw Method: Learning from Shared Expertise

The Jigsaw Learning Method promotes inclusivity by valuing diverse perspectives and individual strengths. It deconstructs traditional classroom hierarchies to promote equality and respect and ensure that each learner plays an active role in everyone’s learning experiences.

Tanner Christensen’s Productivity for Creatives on Skillshare: Turning Ideas into Action

Struggling to get your creative juice flowing, turn ideas into actions, and maintain the productivity required reaching the finish line of your goals? Let this course serve as your guide.

7 Best Data Engineering Courses for Data Wranglers

Becoming a data engineer is easy with the best data engineering courses on this list.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty

Shayna a. rusticus.

Department of Psychology, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, 12666 72 Ave, Surrey, BC V3W 2M8 Canada

Tina Pashootan

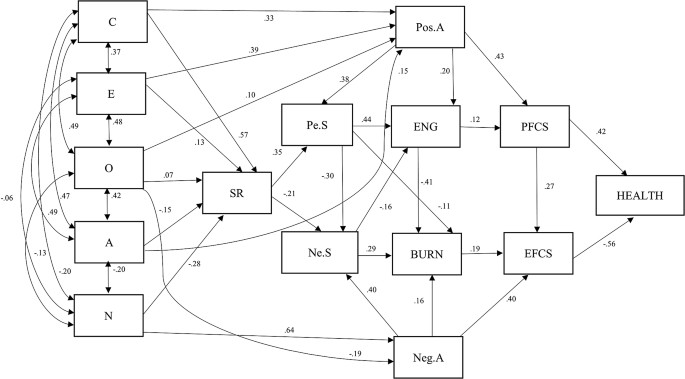

The learning environment comprises the psychological, social, cultural and physical setting in which learning occurs and has an influence on student motivation and success. The purpose of the present study was to explore qualitatively, from the perspectives of both students and faculty, the key elements of the learning environment that supported and hindered student learning. We recruited a total of 22 students and 9 faculty to participate in either a focus group or an individual interview session about their perceptions of the learning environment at their university. We analyzed the data using a directed content analysis and organized the themes around the three key dimensions of personal development, relationships, and institutional culture. Within each of these dimensions, we identified subthemes that facilitated or impeded student learning and faculty work. We also identified and discussed similarities in subthemes identified by students and faculty.

Introduction

The learning environment (LE) comprises the psychological, social, cultural, and physical setting in which learning occurs and in which experiences and expectations are co-created among its participants (Rusticus et al., 2020 ; Shochet et al., 2013 ). These individuals, who are primarily students, faculty and staff, engage in this environment and the learning process as they navigate through their personal motivations and emotions and various interpersonal interactions. This all takes place within a physical setting that consists of various cultural and administrative norms (e.g. school policies).

While many studies of the LE have focused on student perspectives (e.g. Cayubit, 2021 ; Schussler et al., 2021 ; Tharani et al., 2017 ), few studies have jointly incorporated the perspectives of students and faculty. Both groups are key players within the educational learning environment. Some exceptions include researchers who have used both instructor and student informants to examine features of the LE in elementary schools (Fraser & O’Brien, 1985 ; Monsen et al., 2014 ) and in virtual learning and technology engaged environments in college (Annansingh, 2019 ; Downie et al., 2021 ) Other researchers have examined perceptions of both groups, but in ways that are not focused on understanding the LE (e.g. Bolliger & Martin, 2018 ; Gorham & Millette, 1997 ; Midgly et al., 1989 ).

In past work, LEs have been evaluated on the basis of a variety of factors, such as students’ perceptions of the LE have been operationalized as their course experiences and evaluations of teaching (Guo et al., 2021 ); level of academic engagement, skill development, and satisfaction with learning experience (Lu et al., 2014 ); teacher–student and student–peer interactions and curriculum (Bolliger & Martin, 2018 ; Vermeulen & Schmidt, 2008 ); perceptions of classroom personalization, involvement, opportunities for and quality of interactions with classmates, organization of the course, and how much instructors make use of more unique methods of teaching and working (Cayubit, 2021 ). In general, high-quality learning environments are associated with positive outcomes for students at all levels. For example, ratings of high-quality LEs have been correlated with outcomes such as increased satisfaction and motivation (Lin et al., 2018 ; Rusticus et al., 2014 ; Vermeulen & Schmidt, 2008 ), higher academic performance (Lizzio et al., 2002 ; Rusticus et al., 2014 ), emotional well-being (Tharani et al., 2017 ), better career outcomes such as satisfaction, job competencies, and retention (Vermeulen & Schmidt, 2008 ) and less stress and burnout (Dyrbye et al., 2009 ). From teacher perspectives, high-quality LEs have been defined in terms of the same concepts and features as those used to evaluate student perspective and outcomes. For example, in one quantitative study, LEs were rated as better by students and teachers when they were seen as more inclusive (Monsen et al., 2014 ).

However, LEs are diverse and can vary depending on context and, although many elements of the LE that have been identified, there has been neither a consistent nor clear use of theory in assessing those key elements (Schönrock-Adema et al., 2012 ). One theory that has been recommended by Schönrock-Adema et al. ( 2012 ) to understand the LE is Moos’ framework of human environments (Insel & Moos, 1974 ; Moos, 1973 , 1991 ). Through his study of a variety of human environments (e.g. classrooms, psychiatric wards, correctional institutions, military organizations, families), Moos proposed that all environments have three key dimensions: (1) personal development/goal direction, (2) relationships, and (3) system maintenance/change. The personal development dimension encompasses the potential in the environment for personal growth, as well as reflecting the emotional climate of the environment and contributing to the development of self-esteem. The relationship dimension encompasses the types and quality of social interactions that occur within the environment, and it reflects the extent to which individuals are involved in the environment and the degree to which they interact with, and support, each other. The system maintenance/change dimension encompasses the degree of structure, clarity and openness to change that characterizes the environment, as well as reflecting physical aspects of the environment.

We used this framework to guide our research question: What do post-secondary students and faculty identify as the positive and negative aspects of the learning environment? Through the use of a qualitative methodology to explore the LE, over the more-typical survey-based approaches, we were able to explore this topic in greater depth, to understand not only the what, but also the how and the why of what impacts the LE. Furthermore, in exploring the LE from both the student and faculty perspectives, we highlight similarities and differences across these two groups and garner an understanding of how both student and faculty experience the LE.

Participants

All participants were recruited from a single Canadian university with three main campuses where students can attend classes to obtain credentials, ranging from a one-year certificate to a four-year undergraduate degree. Approximately 20,000 students attend each year. The student sample was recruited through the university’s subject pool within the psychology department. The faculty sample was recruited through emails sent out through the arts faculty list-serve and through direct recruitment from the first author.

The student sample was comprised of 22 participants, with the majority being psychology majors ( n = 10), followed by science majors ( n = 4) and criminology majors ( n = 3). Students spanned all years of study with seven in their first year, three in second year, five in third year, six in fourth year, and one unclassified. The faculty sample consisted of nine participants (6 male, 3 female). Seven of these participants were from the psychology department, one was from the criminology department and one was from educational studies. The teaching experience of faculty ranged from 6 to 20 years.

Interview schedule and procedure

We collected student data through five focus groups and two individual interviews. The focus groups ranged in size from two to six participants. All sessions occurred in a private meeting room on campus and participants were provided with food and beverages, as well as bonus credit. Each focus group/interview ranged from 30 to 60 min. We collected all faculty data through individual interviews ranging from 30 to 75 min. Faculty did not receive any incentives for their participation. All sessions were conducted by the first author, with the second author assisting with each of the student focus groups.

With the consent of each participant, we audio-recorded each session and transcribed them verbatim. For both samples, we used a semi-structured interview format involving a set of eight open-ended questions about participants’ overall perceptions of the LE at their institution (see Appendix for interview guide). These questions were adapted from a previous study conducted by the first author (Rusticus et al., 2020 ) and focused on how participants defined the LE, what they considered to be important elements of the LE, and their positive and negative experiences within their environment. Example questions were: “Can you describe a [negative/positive] learning [students]/teaching [faculty] experience that you have had?”.

We analyzed the data using a directed content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005 ) that used existing theory to develop the initial coding scheme. We used Moos’s (Insel & Moos, 1974 ; Moos, 1973 , 1991 ) framework and its three dimensions of personal development, relationships, and system maintenance/change to guide our analysis. During the analysis phase, we renamed the system maintenance/change dimension to ‘institutional setting’ as we felt it was more descriptive of, and better represented, the content of this theme.

We analyzed student and faculty data separately, starting with the student data, but used the same process for both. First, we randomly selected two transcripts. We each independently coded the first transcript using the broad themes of personal development, relationships and institutional setting, and developed subcodes within each of these themes, as needed. We then reviewed and discussed our codes, reaching consensus on any differences in coding. We then repeated this process for the second transcript and, through group discussions, created a codebook. The first author then coded the remaining transcripts.

When coding the faculty data, we aimed to maintain subcodes similar to the student data while allowing for flexibility when needed. For instance, within the personal development theme, a subcode for the student data was ‘engagement with learning’, whereas a parallel subcode for the faculty data was ‘engagement with teaching’.

We present the results of the student and faculty data separately. For both, we have organized our analysis around the three overarching themes of personal development, relationships and institutional setting.

Student perspectives of the learning environment

Personal development.

Personal development was defined as any motivation either within or outside the LE that provide students with encouragement, drive, and direction for their personal growth and achievement. Within this theme, there were two subthemes: engaging with learning and work-life balance.

Engagement with learning reflected a student’s desire and ability to participate in their learning, as opposed to a passive-learning approach. Students felt more engaged when they were active learners, as well as when they perceived the material to be relevant to their career goals or real-world applications. Students also said that having opportunities to apply their learning helped them to better understand their own career paths:

I had two different instructors and both of them were just so open and engaging and they shared so many personal stories and they just seemed so interested in what they were doing and what I was like. Wow, I want to be that. I want to be interested in what I’m learning. (G6P1)

A common complaint that negatively impacted student motivation was that instructors would lecture for the entire class without supporting materials or opportunities for students to participate.

I’ve had a couple professors who just don’t have any visuals at all. All he does is talk. So, for the whole three hours, we would just be scrambling to write down the notes. It’s brutal...(G7P2)

Trying to establish a healthy work-life balance and managing the demands of their courses, often in parallel with managing work and family demands, were key challenges for students and were often sources of stress and anxiety. For instance, one student spoke about her struggles in meeting expectations:

It was a tough semester. For the expectations that I had placed on myself, I wasn’t meeting them and it took a toll on me. But now I know that I can exceed my expectations, but you really have to try and work hard for it. (G6P1)

Achieving a good work-life balance and adjusting to university life takes time. Many students commented that, as they reached their third year of study, they felt more comfortable in the school environment. Unfortunately, students also noted that the mental and emotional toll of university life can lead to doubt about the future and a desire to leave. One student suggested more support for students to help with this adjustment:

I think school should give students more service to help them to overcome the pressure and make integration into the first year and second year quicker and faster. Maybe it’s very helpful for the new students. (G7P4)

Relationships

Relationships was the second dimension of the LE. Subthemes within this dimension included: faculty support, peer interaction, and group work. Most students commented on the impact that faculty had on their learning. Faculty support included creating a safe or unsafe space in the classroom (i.e. ability to ask questions without judgement, fostering a respectful atmosphere), providing additional learning material, accommodating requests, or simply listening to students. Students generally indicated that faculty at this university were very willing to offer extra support and genuinely cared for them and their education. Faculty were described as friendly and approachable, and their relationships with students were perceived as “egalitarian”.

I think feeling that you’re safe in that environment, that anything you pose or any questions that you may have, you’re free to ask. And without being judged. And you’ll get an answer that actually helps you. (G1P4)

While most students felt welcome and comfortable in their classes, a few students spoke about negative experiences that they had because of lack of faculty support. Students cited examples of professors “shutting down” questions, saying that a question was “stupid”, refusing requests for additional help, or interrupting them while speaking. Another student felt that the inaction of faculty sometimes contributed to a negative atmosphere:

I’ve had bad professors that just don't listen to any comment or, if you suggest something to improve it which may seem empirically better, they still shut you down! That’s insane. (G2P2)

The peer interactions subtheme referred to any instances when students could interact with other students; this occurred both in and out of the classroom. Most often, students interacted with their peers during a class or because of an assignment:

I think the way the class is structured really helps you build relationships with your peers. For example, I met S, we had several classes with each other. Those classes were more proactive and so it allowed us to build a relationship… I think that’s very important because we’re going to be in the same facility for a long time and to have somebody to back you up, or to have someone to study with…”. (G1P4)

However, other students felt that they lacked opportunities to interact with peers in class. Although a few participants stated that they felt the purpose of going to school was to get a degree, rather than to socialize with others, students wanted more opportunities to interact with peers.

The final subtheme, group work, was a very common activity at this school. The types of group work in which students engaged included classroom discussions, assignments/projects, and presentations. Many students had enjoyable experiences working in groups, noting that working together helped them to solve problems and create something that was better than one individual’s work. Even though sometimes doing the work itself was a negative experience, people still saw value in group work:

Some of the best memories I’ve ever had was group work and the struggles we've had. (G2P2) I don’t like group work but it taught me a lot, I’ve been able to stay friends and be able to connect with people that I’ve had a class with in 2nd year psych all the way up till now. I think that’s very valuable. (G6P1)

Almost all students who spoke about group work also talked about negative aspects or experiences they had. When the work of a group made up a large proportion of the final grade, students sometimes would have preferred to be evaluated individually. Students disliked when they worked in groups when members were irresponsible or work was not shared equally, and they were forced to undertake work that other students were not completing.

A lot of people don’t really care, or they don’t take as much responsibility as you. I think people have different goals and different ways of working, so sometimes I find that challenging. (G7P2)

Institutional setting

The third overarching theme was the institutional setting. Broadly, this theme refers to the physical structure, expectations, and the overall culture of the environment and was composed of two key subthemes: importance of small class sizes; and the lack of a sense of community.

Small class sizes, with a maximum of 35 students, were a key reason why many students chose to come to this institution. The small classes created an environment in which students and faculty were able to get to know one another more personally; students felt that they were known as individuals, not just as numbers. They also noted that this promoted greater feelings of connectedness to the class environment, more personalized attention, and opportunities to request reference letters in the future:

My professors know my name. Not all of them that I’m having for the first time ever, but they try… That means a lot to me. (G6P4)

Several students also said that having smaller class sizes helped them to do well in their courses. The extra attention encouraged them to perform better academically, increased their engagement with their material, and made them feel more comfortable in asking for help.

Having a sense of belonging was a key feature of the environment and discussions around a sense of community (or lack thereof) was a prominent theme among the students. Students generally agreed that the overall climate of the school is warm and friendly. However, many students referred to the institution as a “commuter school”, because there are no residencies on campus and students must commute to the school. This often resulted in students attending their classes and then leaving immediately after, contributing to a lack of community life on campus.

What [other schools] have is that people live on campus. I think that plays a huge role. We can’t ignore that we are a commuter school… They have these events and people go because they’re already there and you look at that and it seems to be fun and engaging. (G4P1)

Furthermore, students commented on a lack of campus areas that supported socialization and encouraged students to remain on campus. While there were events and activities that were regularly hosted at the school, students had mixed opinions about them. Some students attended the events and found them personally beneficial. Other students stated that, although many events and activities were available, turnout was often low:

There isn’t any hanging out after campus and you can even see in-events and in-event turnout for different events… It is like pulling teeth to get people to come out to an event… There are free food and fun music and really cool stuff. But, no one’s going to go. It’s sad. (G5P1)

Faculty perspectives on the learning environment

Similar to the student findings, faculty data were coded within the three overarching themes of personal development, relationships, and institutional setting.

Personal development reflected any motivation either within or outside the LE that provided faculty with the encouragement, drive, and direction for their personal growth and engagement with teaching. Within this dimension, there were two main subthemes: motivation to teach and emotional well-being.

As with any career, there are many positive and negative motivating factors that contribute to one’s involvement in their work. Faculty generally reported feeling passionate about their work, and recounted positive experiences they have had while teaching, both personally and professionally. While recollecting positive drives throughout their career, one instructor shared:

It’s [teaching in a speciality program] allowed me to teach in a very different way than the traditional classroom… I’ve been able to translate those experiences into conferences, into papers, into connections, conversations with others that have opened up really interesting dialogues…. (8M)

Faculty also reported that receiving positive feedback from students or getting to see their students grow over time was highly motivating:

I take my teaching evaluations very seriously and I keep hearing that feedback time and time again they feel safe. They feel connected, they feel listened too, they feel like I'm there for them. I think, you know, those are the things that let me know what I'm doing is achieving the goals that I have as an educator. (1F) Being able to watch [students] grow over time is very important to me… I always try to have a few people I work with and see over the course of their degree. So, when they graduate, you know I have a reason to be all misty-eyed. (2M)

Emotional well-being related to how different interactions, primarily with students, affected instructors’ mental states. Sometimes the emotional well-being of faculty was negatively affected by the behaviour of students. One instructor spoke about being concerned when students drop out of a class:

A student just this last semester was doing so well, but then dropped off the face of the earth… I felt such a disappointing loss… So, when that happens, I'm always left with those questions about what I could have done differently. Maybe, at the end of the day, there is nothing I could've done, nothing. It's a tragedy or something's happened in their life or I don't know. But those unanswered questions do concern-- they cause me some stress or concern. (1F)

Another instructor said that, while initially they had let the students’ behaviour negatively affect their well-being, over time, they had eventually become more apathetic.

There are some who come, leave after the break. Or they do not come, right, or come off and on. Previously I was motivated to ask them ‘what is your problem?’ Now I do not care. That is the difference which has happened. I do not care. (4M)

This dimension included comments related to interactions with other faculty and with students and consisted of three subthemes: faculty supporting faculty; faculty supporting students; and creating meaningful experiences for students.

Most faculty felt that it was important to be supported by, and supportive to, their colleagues. For instance, one instructor reported that their colleagues’ helpfulness inspired them to be supportive of others:

If I was teaching a new course, without me having to go and beg for resources or just plead and hope that someone might be willing to share, my experience was that the person who last taught the course messaged me and said let me know if anything I have will be useful to you… When people are willing to do that for you, then you’re willing to do that for someone else….(7M)

Many faculty members also spoke about the importance of having supportive relationships with students, and that this would lead to better learning outcomes:

If you don't connect with your students, you're not going to get them learning much. They're not; they're just going to tune out. So, I think, I think connection is critical to having a student not only trust in the learning environment, but also want to learn from the learning environment. (3M)

Facilitating an open, inviting space in the classroom and during their office hours, where students were comfortable asking questions, was one way that faculty tried to help students succeed. Faculty also spoke about the value of having close mentorship relationships with students:

I work with them a lot and intensively…and their growth into publishing, presenting, and seeing them get recognized and get jobs on their way out and so forth are extraordinary. So, being able to watch them grow over time is very important to me. (2M)

Faculty also noted that occasionally there were instances when students wanted exceptions to be made for them which can create tensions in the environment. One instructor spoke about the unfairness of those requests arguing that students need to be accountable to themselves:

The failure rate, …it was 43%. I do not know if there is any other course in which there is a 43% failure rate. So, I do not want to fail these students, why? Instructors want these students to pass, these are my efforts […], and there are also the efforts of these students and their money, right? But, if a student doesn’t want to pass himself or herself, I cannot pass this student, that’s it. (4M)

Faculty were generally motivated to provide memorable and engaging experiences for students. These included providing practical knowledge and opportunities to apply knowledge in real-world settings, field schools, laboratory activities, group discussions, guest speakers, field trips, videos and group activities. They were often willing to put in extra effort if it meant that students would have a better educational experience.

Creating meaningful experiences for students was also meaningful for faculty. One faculty member said that faculty felt amazing when the methods that they used in their courses were appreciated by students. Another faculty member noted:

This student who was in my social psychology class, who was really bright and kind of quirky, would come to my office, twice a week, and just want to talk about psychology … That was like a really satisfying experience for me to see someone get so sparked by the content. (9F)

This third theme refers to the physical structure, expectation, and overall culture of the environment and it consisted of two subthemes: the importance of small class sizes, and the lack of a sense of community.

The majority of the faculty indicated that the small class sizes are an integral feature of the LE. The key advantage of the small classes was that they allowed greater connection with students.

Your professor knows your name. That’s a huge difference from other schools. It’s a small classroom benefit. (6F)

Similar to the students, nearly all the faculty indicated that a sense of community at the institution was an important part of the environment, and something that was desired, but it currently was lacking. They spoke about various barriers which prevent a sense of community, such as the lack of residences, a dearth of events and activities at the university, the busy schedules of faculty and students, the commuter nature of the school, and characteristics of the student population:

When I complain about the commuter campus feeling that occurs with students, we suffer from that too at a faculty level… People are just not in their offices because we work from home… And that really also affects the culture… We come in. We do our thing. We meet with students. And then we leave… I encounter so many students in the hallway who are looking for instructors and they can’t find them. (9F)

These findings have provided insight into the perspectives of both students and faculty on the LE of a Canadian undergraduate university. We found that framing our analysis and results within Moos’ framework of human environments (Insel & Moos, 1974 ; Moos, 1973 , 1991 ) was an appropriate lens for the data and that the data fit well within these three themes. This provides support for the use of this theory to characterize the educational LE. Within each of these dimensions, we discuss subthemes that both facilitated and hindered student learning and commonalities among student and faculty perspectives.

Within the personal development dimension, both students and faculty discussed the importance of engagement and/or motivation as a facilitator of a positive LE. When students were engaged with their learning, most often by being an active participant or seeing the relevance of what they were learning, they saw it as a key strength. Other studies have also identified engagement as a feature of positive LEs for populations such as high-school students (Seidel, 2006 ), nursing students (D’Souza et al., 2013 ) and college students taking online courses (e.g. Holley & Dobson, 2008 ; O’Shea et al., 2015 ). Faculty who reported being motivated to teach, often felt that this motivation was fueled by the reactions of their students; when students were engaged, they felt more motivated. This creates a positive cyclic pattern in which one group feeds into the motivation and engagement levels of the other. However, this can also hinder the LE when a lack of engagement in one group can bring down the motivation of the other group (such as students paying more attention to their phones than to a lecture or faculty lecturing for the entire class period).

Emotional climate was another subtheme within the personal development dimension that was shared by both students and faculty although, for students, this was focused more on the stress and anxiety that they felt trying to manage their school workloads with their work and family commitments. The overall emotional climate of the school was generally considered to be positive, which was largely driven by the supportive and welcoming environment provided by the faculty. However, it was the negative emotions of stress and anxiety that often surfaced as a challenging aspect in the environment for students. Past research suggests that some types of stress, such as from a challenge, can improve learning and motivation, but negative stress, such as that reported by our participants, is associated with worsened performance and greater fatigue (LePine et al., 2004 ).

For faculty, their emotional state was often influenced by their students. When things were going well for their students, faculty often shared in the joy; however, when students would disappear without notice from a class, it was a source of disappointment and self-doubt. For other faculty, the accumulation of negative experiences resulted in them being more distant and less affected emotionally than they had been earlier in their career. This diminishing concern could have implications for how engaged faculty are in their teaching, which could in turn influence student engagement and harm the LE.

The relationships dimension was the most influential aspect of the environment for both students and faculty. While both groups felt that the relationships that they formed were generally positive, they also reported a desire for more peer connections (i.e. students with other students and faculty with other faculty). Students commented that it was a typical experience for them to come to campus to attend their classes and then leave afterwards, often to work or study at home. Many of the students at this school attend on a part-time basis while they work part- or full-time and/or attend to family commitments. While this is a benefit to these students to have the flexibility to work and further their education, it comes at loss of the social aspect of post-secondary education.

The one way in which student–peer relationships were fostered was through group work. However, students held both positive and negative views on this: the positive aspect was the opportunity to get to know other students and being able to share the burden of the workload, and the negative aspect was being unfair workloads among team members. When group dynamics are poor, such as unfair work distribution, having different goals and motivations, or not communicating effectively with their groups, it has been shown to lead to negative experiences (Rusticus & Justus, 2019 ).

Faculty also commented that it was typical for them and other faculty to come up to campus only to teach their classes and then leave afterwards. They noted that their office block was often empty and noted instances when students have come looking for faculty only to find a locked office. Overall, faculty did report feeling congenial with, and supported by, their peers. They also desired a greater connection with their peers, but noted that it would require effort to build, which many were not willing to make.

Finally, student–faculty relationships were the most-rewarding experience for both groups. Students saw these experiences as highly encouraging and felt that they created a safe and welcoming environment where they could approach faculty to ask questions and get extra support. However, in some cases, students had negative experiences with faculty and these had an impact on their self-esteem, motivation and willingness to participate in class. Students’ negative experiences and feedback have been shown to result in declined levels of intrinsic motivation, even if their performance ability is not low (Weidinger et al., 2016 ).

Within the third dimension, institutional setting, a key strength was the small class sizes. With a maximum class size of 35 students, this created a more personal and welcoming environment for students. Students felt that their instructors got to know their names and this promoted more opportunities for interactions. Faculty concurred with this, indicating that the small classes provided greater opportunities for interactions with their students. This enabled more class discussions and grouped-based activities which contributed to a more engaging and interactive educational experience for students and faculty. For students, not being able to hide in the crowd of a large lecture hall, as is common in other university settings, encouraged them to work harder on their studies and to seek help from their instructor if needed.

Finally, both students and faculty commented that the lack of a sense of community was a negative aspect of the LE. This institution is known as a commuter school and both groups reported that they would often attend campus only for school/work and would leave as soon as their commitments were done. This limits opportunities to interact with others and could also potentially impact one’s identity as a member of this community. While both groups expressed a desire for more of a community life, neither group was willing to put in much effort to make this happen. Others have also found that sense of community, including opportunities to engage and interact with others, is important in LEs (e.g. Sadera et al., 2009 ). Schools with more activities and opportunities for student involvement have reports of higher satisfaction for both academic and social experiences (Charles et al., 2016 ).

Limitations

Because this study is based on a relatively small sample at a single university, there is a question of whether the findings can be applied to other departments, universities or contexts. However, it is a strength of this study that both student and faculty perceptions were included, because few past studies have jointly looked at these two groups together using qualitative methods. The use of focus groups among the student groups might have limited the openness of some participants. We also acknowledge that the analysis of qualitative data is inevitably influenced by our roles, life experiences and backgrounds. (The first author is a faculty member and the second and third authors were fourth year students at the time of the study.) This might have impacted our approach to the interpretation of the data compared with how others might approach the data and analysis (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008 ). However, the analysis involved consultation among the research team to identify and refine the themes, and the findings are presented with quotes to support the interpretation. Finally, because experiences were self-reported in this study, they have the associated limitations of self-report data. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings add to what is known about LEs by capturing multiple perspectives within the same environment.

Future directions

Because our sample was comprised of students across multiple years of their program, some of our findings suggest that upper-level students might have different perceptions of the LE from lower-level students (e.g. work/life balance, access to resources, and overall familiarity with the environment and resources available). However, because the small sample sizes within these subgroups prevent any strong conclusions being made, future researchers might want to explore year-of-study differences in the LE. Additionally, the data collected for this study occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the mandatory switch to online teaching and learning. Future researchers might want to consider how this has impacted student and faculty perceptions of the LE regarding their personal motivation, the nature and quality of the relationships that have formed with peers and faculty, and the culture and norms of their institution.

This study increases our understanding of LEs by incorporating data collected from both students and faculty working in the same context. Across both groups, we identified important aspects of the LE as being high levels of engagement and motivation, a positive emotional climate, support among peers, strong faculty–student relationships, meaningful experiences, and small class sizes. Students identified negative aspects of the LE, such as certain characteristics of group work and struggles with work–life balance. Both faculty and students identified a lack of a sense of community as something that could detract from the LE. These findings identify important elements that educators and researchers might want to consider as they strive to promote more-positive LEs and learning experiences for students.

Appendix: Interview guide

[Faculty] Tell me a little bit about yourself. For instance, what department you are in, how long you have been teaching at KPU, what courses you teach, why you were interested in this study

- When I say the word learning environment, what does that mean to you?

- Probe for specific examples

- Relate to goal development, relationships, KPU culture

- Probe for factors that made it a positive environment

- Probe for factors that made it a negative environment

- How would you describe an ideal environment?

- Probe for reasons why

- Probe for how KPU could be made more ideal

- What recommendations would you give to the Dean of Arts regarding the learning environment? This could be changes you would recommend or things you recommend should stay the same.

- Do you have any final comments? Or feel there is anything about the learning environment that we have not addressed?

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Annansingh F. Mind the gap: Cognitive active learning in virtual learning environment perception of instructors and students. Education and Information Technologies. 2019; 24 (6):3669–3688. doi: 10.1007/s10639-019-09949-5. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bolliger DU, Martin F. Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Education. 2018; 39 (4):568–583. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2018.1520041. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cayubit RFO. Why learning environment matters? An analysis on how the learning environment influences the academic motivation, learning strategies and engagement of college students. Learning Environments Research. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10984-021-09382-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Charles CZ, Fischer MJ, Mooney MA, Massey DS. Taming the river: Negotiating the academic, financial, and social currents in selective colleges and universities. Princeton University Press; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Souza MA, Venkatesaperumal R, Radhakrishnan J, Balachandran S. Engagement in clinical learning environment among nursing students: Role of nurse educators. Open Journal of Nursing. 2013; 31 (1):25–32. doi: 10.4236/ojn.2013.31004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Sage; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Downie S, Gao X, Bedford S, Bell K, Kuit T. Technology enhanced learning environments in higher education: A cross-discipline study on teacher and student perceptions. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice. 2021; 18 (4):12–21. doi: 10.53761/1.18.4.12. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Harper W, Massie FS, Jr, Power DV, Eacker A, Szydlo DW, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. The learning environment and medical student burnout: A multicentre study. Medical Education. 2009; 43 (3):274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03282.x. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraser BJ, O'Brien P. Student and teacher perceptions of the environment of elementary school classrooms. The Elementary School Journal. 1985; 85 (5):567–580. doi: 10.1086/461422. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gorham J, Millette DM. A comparative analysis of teacher and student perceptions of sources of motivation and demotivation in college classes. Communication Education. 1997; 46 (4):245–261. doi: 10.1080/03634529709379099. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo JP, Yang LY, Zhang J, Gan YJ. Academic self-concept, perceptions of the learning environment, engagement, and learning outcomes of university students: Relationships and causal ordering. Higher Education. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00705-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holley D, Dobson C. Encouraging student engagement in a blended learning environment: The use of contemporary learning spaces. Learning, Media and Technology. 2008; 33 (2):139–150. doi: 10.1080/17439880802097683. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15 :1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Insel PM, Moos RH. Psychological environments: Expanding the scope of human ecology. American Psychologist. 1974; 29 :179–188. doi: 10.1037/h0035994. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LePine JA, LePine MA, Jackson CL. Challenge and hindrance stress: Relationships with exhaustion, motivation to learn, and learning performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004; 89 (5):883–891. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.883. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin S, Salazar TR, Wu S. Impact of academic experience and school climate of diversity on student satisfaction. Learning Environments Research. 2018; 22 :25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10984-018-9265-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lizzio A, Wilson K, Simons R. University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: Implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher Education. 2002; 27 :27–52. doi: 10.1080/03075070120099359. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lu G, Hu W, Peng Z, Kang H. The influence of undergraduate students’ academic involvement and learning environment on learning outcomes. International Journal of Chinese Education. 2014; 2 (2):265–288. doi: 10.1163/22125868-12340024. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Eccles JS. Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development. 1989; 60 (4):981–992. doi: 10.2307/1131038. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Monsen JJ, Ewing DL, Kwoka M. Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, perceived adequacy of support and classroom learning environment. Learning Environments Research. 2014; 17 :113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10984-013-9144-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moos RH. Conceptualizations of human environments. American Psychologist. 1973; 28 :652–665. doi: 10.1037/h0035722. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moos RH. Connections between school, work and family settings. In: Fraser BJ, Walberg HJ, editors. Educational environments: Evaluation, antecedents and consequences. Pergamon Press; 1991. pp. 29–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Shea S, Stone C, Delahunty J. “I ‘feel’ like I am at university even though I am online.” Exploring how students narrate their engagement with higher education institutions in an online learning environment. Distance Education. 2015; 36 (1):41–58. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2015.1019970. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rusticus SA, Justus B. Comparing student- and teacher-formed teams on group dynamics, satisfaction and performance. Small Group Research. 2019; 50 (4):443–457. doi: 10.1177/1046496419854520. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rusticus, S. A., Wilson, D., Casiro, O., & Lovato, C. (2020). Evaluating the quality of health professions learning environments: development and validation of the health education learning environment survey (HELES). Evaluation & the health professions, 43 (3), 162–168. 10.1177/0163278719834339 [ PubMed ]

- Rusticus SA, Worthington A, Wilson DC, Joughin K. The Medical School Learning Environment Survey: An examination of its factor structure and relationship to student performance and satisfaction. Learning Environments Research. 2014; 17 :423–435. doi: 10.1007/s10984-014-9167-9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sadera WA, Robertson J, Song L, Midon MN. The role of community in online learning success. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 2009; 5 (2):277–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schönrock-Adema J, Bouwkamp-Timmer T, van Hell EA, Cohen-Schotanus J. Key elements in assessing the educational environment: Where is the theory? Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2012; 17 :727–742. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9346-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schussler, E. E., Weatherton, M., Chen Musgrove, M. M., Brigati, J. R., & England, B. J. (2021). Student perceptions of instructor supportiveness: What characteristics make a difference? CBE—Life Sciences Education , 20 (2), Article 29. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Seidel T. The role of student characteristics in studying micro teaching–learning environments. Learning Environments Research. 2006; 9 (3):253–271. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.08.004. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shochet RB, Colbert-Getz JM, Levine RB, Wright SM. Gauging events that influence students’ perceptions of the medical school learning environment: Findings from one institution. Academic Medicine. 2013; 88 :246–252. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827bfa14. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tharani A, Husain Y, Warwick I. Learning environment and emotional well-being: A qualitative study of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2017; 59 :82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.008. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vermeulen L, Schmidt HG. Learning environment, learning process, academic outcomes and career success of university graduates. Studies in Higher Education. 2008; 33 (4):431–451. doi: 10.1080/03075070802211810. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weidinger AF, Spinath B, Steinmayr R. Why does intrinsic motivation decline following negative feedback? The mediating role of ability self-concept and its moderation by goal orientations. Learning and Individual Differences. 2016; 47 :117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.01.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Learning can be defined as the process leading to relatively permanent behavioral change or potential behavioral change. In other words, as we learn, we alter the way we perceive our environment, the way we interpret the incoming stimuli, and therefore the way we interact, or behave. John B. Watson (1878-1958) was the first to study how the process of learning affects our behavior, and he formed the school of thought known as Behaviorism. The central idea behind behaviorism is that only observable behaviors are worthy of research since other abstraction such as a person’s mood or thoughts are too subjective. This belief was dominant in psychological research in the United Stated for a good 50 years.

Perhaps the most well known Behaviorist is B. F. Skinner (1904-1990). Skinner followed much of Watson’s research and findings, but believed that internal states could influence behavior just as external stimuli. He is considered to be a Radical Behaviorist because of this belief, although nowadays it is believed that both internal and external stimuli influence our behavior.

Behavioral Psychology is basically interested in how our behavior results from the stimuli both in the environment and within ourselves. They study, often in minute detail, the behaviors we exhibit while controlling for as many other variables as possible. Often a grueling process, but results have helped us learn a great deal about our behaviors, the effect our environment has on us, how we learn new behaviors, and what motivates us to change or remain the same.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is the Psychology of Learning?

Learning in psychology is based on a person's experiences

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

James Lacy, MLS, is a fact-checker and researcher.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/James-Lacy-1000-73de2239670146618c03f8b77f02f84e.jpg)

The psychology of learning focuses on a range of topics related to how people learn and interact with their environments.

Are you preparing for a big test in your psychology of learning class? Or are you just interested in a review of learning and behavioral psychology topics? This learning study guide offers a brief overview of some of the major learning issues including behaviorism, classical, and operant conditioning .

Let's learn a bit more about the psychology of learning.

Definition of Learning in Psychology

Learning can be defined in many ways, but most psychologists would agree that it is a relatively permanent change in behavior that results from experience. During the first half of the 20th century, the school of thought known as behaviorism rose to dominate psychology and sought to explain the learning process. Behaviorism sought to measure only observable behaviors.

3 Types of Learning in Psychology

Behavioral learning falls into three general categories.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is a learning process in which an association is made between a previously neutral stimulus and a stimulus that naturally evokes a response.

For example, in Pavlov's classic experiment , the smell of food was the naturally occurring stimulus that was paired with the previously neutral ringing of the bell. Once an association had been made between the two, the sound of the bell alone could lead to a response.

For example, if you don't know how to swim and were to fall into a pool, you'd take actions to avoid the pool.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning is a learning process in which the probability of a response occurring is increased or decreased due to reinforcement or punishment. First studied by Edward Thorndike and later by B.F. Skinner , the underlying idea behind operant conditioning is that the consequences of our actions shape voluntary behavior.

Skinner described how reinforcement could lead to increases in behaviors where punishment would result in decreases. He also found that the timing of when reinforcements were delivered influenced how quickly a behavior was learned and how strong the response would be. The timing and rate of reinforcement are known as schedules of reinforcement .

For example, your child might learn to complete their homework because you reward them with treats and/or praise.

Observational Learning

Observational learning is a process in which learning occurs through observing and imitating others. Albert Bandura's social learning theory suggests that in addition to learning through conditioning, people also learn through observing and imitating the actions of others.

Basic Principles of Social Learning Theory

As demonstrated in his classic Bobo Doll experiments, people will imitate the actions of others without direct reinforcement. Four important elements are essential for effective observational learning: attention, motor skills, motivation, and memory.

For example, a teen's older sibling gets a speeding ticket, with the unpleasant results of fines and restrictions. The teen then learns not to speed when they take up driving.

The three types of learning in psychology are classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning.

History of the Psychology of Learning

One of the first thinkers to study how learning influences behavior was psychologist John B. Watson , who suggested in his seminal 1913 paper Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It that all behaviors are a result of the learning process. Psychology, the behaviorists believed, should be the scientific study of observable, measurable behavior. Watson's work included the famous Little Albert experiment in which he conditioned a small child to fear a white rat.

Behaviorism dominated psychology for much of the early 20th century. Although behavioral approaches remain important today, the latter part of the century was marked by the emergence of humanistic psychology, biological psychology, and cognitive psychology .

Other important figures in the psychology of learning include:

- Edward Thorndike

- Ivan Pavlov

- B.F. Skinner

- Albert Bandura

A Word From Verywell

The psychology of learning encompasses a vast body of research that generally focuses on classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning. As the field evolves, it continues to have important implications for explaining and motivating human behavior.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Learning Is a Learned Behavior. Here’s How to Get Better at It.

- Ulrich Boser

It’s effectively a type of project management.

Many people mistakenly believe that people are born learners, or they’re not. However, a growing body of research shows that learning is a learned behavior. Through the deliberate use of dedicated strategies, we can all develop expertise faster and more effectively. There are three practical strategies for this, starting with organization. Effective learning often boils down to a type of project management. In order to develop an area of expertise, we first have to set achievable goals about what we want to learn and then develop strategies to reach those goals. Another practical method is thinking about thinking. Also known as metacognition, this is akin to asking yourself questions like “Do I really get this idea? Could I explain it to a friend?” Finally, reflection is a third practical way to improve your ability to learn. In short, we can all learn to become a better study.

Many people mistakenly believe that the ability to learn is a matter of intelligence. For them, learning is an immutable trait like eye color, simply luck of the genetic draw. People are born learners, or they’re not, the thinking goes. So why bother getting better at it?

- UB Ulrich Boser is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress, where he also founded and runs the science of learning initiative. He’s the author of Learn Better: Mastering the Skills for Success in Life, Business, and School, or, How to Become an Expert in Just About Anything .

Partner Center

Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning Essay

Introduction, learning and cognition, reference list.

According to Kimble (1961), learning is taken as the process that brings in a relatively permanent alteration in behavior or potentiality in behavior as a result of reinforcement. For leaning to take place there must be a permanent change in the behavior. Therefore learning omits those behavior changes that are not permanent such as sleeping, eating and so on. In addition the term learning also do not consider the permanent changes that result due to maturation as learning process.

Whenever learning occurs, it is manifested as a change in behavior. The change though does not result immediately after learning, but occurs after some time span. Since learning cannot be studied directly, learning of behavior change is an important aspect because gives an inference to the process that preside behavior change and hence making the study of learning possible.

Except for B.F. Skinner who considers reinforcement and punishment as the most important aspects of learning behavior, majority of the learning theorist consider that learning compose of a superseding variable between experience and behavior (Olson & Hergenhahn, 2009). This helps to differentiate performance and learning where performance exhibit the real learning as a behavior, although learning is regarded to take place before the exhibition of the learned behavior through performance.

Thus it should be taken to represent potential for future behavior. Thus in summary, learning can be taken to represent behavior in potential that signify a superseding variable between experience and behavior; that ultimately gets expressed through the tool of performance.

Conditioning is one process through which learning takes place. This type of learning was initially formulated by Pavlov and later augmented by Skinner. Conditioning can further be split into two groups.

These are classical conditioning and Instrumental conditioning. In the former conditioning, learning occurs when animals master how to associate neutral stimulus with natural stimulus they are familiar with. For instance classical conditioning results when a dog salivates when a man with a lab coat passes. This can happen only if the man that feeds the dog wears a lab coat every time he does it. Therefore the dog learns to associate the lab coat with food. Thus every time it sees a lab coat it associates it with food.

On the other hand, the latter conditioning is also known as operant conditioning and it occurs when a behavior that already exists is reinforced in order to increases its chances of reoccurrences (Olson & Hergenhahn 2009). Similarly it occurs when an animal masters to act in a certain manner in order to receive an intrinsically rewarding stimulus. This can be inferred by jumping of a trained dolphin from a pool of water so that to get a fish.

This results if the dolphin is given a fish every time it reaps. These forms of learning are very important in the day to day lives since Classical conditioning is used to differentiate between those objects that are essential for survival and those that are not, while on the other hand, operant conditioning is used for avoidance of unwanted objects.

Almost every theory of learning includes cognitive association into the general stimulus-response relationship advocated by operant and classical conditioning. The said cognitive association can occur between an occurrence of two stimuli (S-O), depiction of a stimulus and response (S-R) or finally a representation of a response and an outcome (R-O).

The most important factor in all these associations is that anticipation of the results acts as the mediator between learning and performance. Therefore the S-R association can result from preconditioning events (Kimble, 1961).

For instance introducing of a pairing related stimuli and do away with any reinforcement which will result into the expectation that future representation of one of the stimulus will lead to the occurrence of the other one. On the other hand, reducing the frequency of representation of a set of stimuli will reduce the future expectancy of the representation of the desired stimuli or response.

For example when a dog is conditioned that every time it sees a man with a lab coat it gets its food will salivate every moment it sees any man wearing a lab coat. Therefore there is a general expectancy that when the dog sees a man with a lab coat it will definitely salivate since it associates the lab coat with the stimulus it is familiar with food. If this procedure is altered and the dog does not get its food every time it sees a man with a lab coat, its expectation that it will salivate every time it sees a man with a lab coat decreases.

Behavior change can be regarded as the ultimate result of learning that is represented through the instrument of performance. Classical conditioning and instrumental conditioning are considered as the two forms of learning through which other form of learning can be linked to. It is from this learning paradigm that forms the basis of cognitive association which tries to explain the expectancy of future happenings as a mediating variable that helps to build a framework to enable comprehend cognitive processes so that to assist in.

Kimble, G. (1961). Hilgard, Ernest R. and Marquis, Donald G. Hilgard and Marquis’ Conditioning and learning. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Olson, Mathew., & Hergenhahn, B. (2009). An Introduction to Theories of Learning. (Eighth Edition). New York: Prentice Hall.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 27). Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning. https://ivypanda.com/essays/learning-and-cognition/

"Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning." IvyPanda , 27 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/learning-and-cognition/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning'. 27 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/learning-and-cognition/.

1. IvyPanda . "Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/learning-and-cognition/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Behavior Change: Cognitive Processes in Learning." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/learning-and-cognition/.

- Impacts of Oil Spill on Dolphins and Fishing in Gulf of Mexico

- Operant Conditioning Theory by Burrhus Frederic Skinner

- Conditioning Theory by B.F. Skinner

- Language in Cognitive Psychology

- Improvement of Visual Intelligence in Psychology

- Relying on Senses: Concerning the Physicalism. Information vs. Experience

- Current Directions in Life-Span Development

- Evaluating Daniel Tammet’s Intelligence

Behavior for Learning Strategies in Education

Introduction

Teachers, to ensure that students are behaving well in class to learn, use behaviour for Learning (B4L) strategies (Adams, 2009). The relationships are the crucial influences upon children’s learning behaviours (Adams, 2009). Such relationships are with themselves, others and the curriculum (East Sussex Primary GTP, 2009). If these relationships are approached positively by a teacher, the students can “increase opportunities for learning” (ESP GTP, 2009, p.1). Focusing on the lessons from year 6 class, this essay will show the two key strategies, which are supporting pupil’s emotional well being, which caters the relationship with themselves and others, and utilizing simple, clear and well paced lessons with stimulating activities, which caters the relationship with the curriculum (ESP GTP, 2009; Elton Report, 1989). These strategies can be used to create an effective and purposeful classroom environment.

To support student’s emotional wellbeing, the teacher needs to attempt to make a positive relationship with the students. According to Haydn (2007), students preferred friendly teachers who praised and encourage them through learning process. Positive reinforcement can support students to feel valued and emotionally secure, which impacts positively and neurologically on their learning behavior (NHSS, 2004). On the other hand, if the students don’t feel valued and feel insecure, they will more likely have low self-esteem (NHS, 2004). Low-self esteem is the major barrier to effective learning and motivation (Cohen et al, 2010). Hence, motivation is a crucial element of learning and success in school and helps students achieve and maintain good behavior (Wentzel, 2012; Wentzel & Wigfield, 2009; Wigfield et al., 2006). Unlike the punishment, positive reinforcement lasts for long term and lasts effectiveness over time (Kohn, 2006). This was clearly seen in the observation of most of the lessons as the teacher precisely praised (Lemov, 2010) most students during the discussion although they were not exactly correct but related. Students who have given wrong answers were also praised for participating in the discussion and this encouraged the normalizing of errors when trying (Lemov, 2010). The students looked more confident and frequently had their hands up more ever since, showing the effect of praise and encouragement.