Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

10 Pillars of a Strong Relationship

Your performance evaluation at work comes in, and it’s glowing. However, there’s one area that “needs improvement.” Days later, which part do you think about?

The negative, of course. Part of you knows it’s ridiculous to let that one thing bother you. After all, there’s a lot more good in there than bad, but you can’t seem to help it.

Unfortunately, we do the same thing in our romantic relationships. We all have a negativity bias , or tendency to focus on the bad aspects of experiences. This makes us more critical of our relationship than we should be. Along the way, we take the good times for granted and they become an under-appreciated part of our partnership. But the problems? They stand out. Our partner’s insensitive comments, moods, and messiness regularly capture our full attention.

Mix this into a relationship that has lost a bit of its spark, and it can be hard to notice anything other than the problems. As Daniel Kahneman describes in Thinking, Fast and Slow , we tend to only see what’s right in front of us and overlook what’s not there at the moment. When problems are all that you see, it feels like that’s all your relationship is.

In fact, we have such a strong tendency to pick up on the bad stuff that we may even manufacture problems that don’t exist. A study published in Science suggests that if our relationship doesn’t have any major issues, we’re more likely to take what once would have been considered a small issue and feel it’s more problematic.

When we spend our time worrying about the wrong things, we don’t have time to appreciate what’s going right. Not only does this mean our view of the relationship is skewed, but it also means we’re missing out on a meaningful opportunity. While working on problems is one way to improve a long-term relationship, it’s just as important to reflect on your partner’s good qualities and the positive aspects of your connection.

The pillars of healthy relationships

To shift your perspective, start by paying more attention to the facets of your relationship that are stable, consistent, and comfortable. Those peaceful, drama-free, status-quo elements are easy to forget, but they’re sources of strength.

Below are 10 key pillars of healthy relationships that research suggests are key to a satisfying, lasting bond. Many of these are likely present in your own relationship; you just need to pause and take notice.

1. You can be yourself. You and your partner accept each other for who you are; you don’t try to change each other. You can simply be yourself and show your true identity without worrying if your partner will judge you. That’s helpful because research shows that partners who accept each other tend to be more satisfied with their relationships.

2. You are BFFs. In many ways, your romantic partner is your best friend, and you’re theirs. That’s good news because research suggests that romantic partners who emphasize friendship tend to be more committed and experience more sexual gratification. Romantic relationships that value friendship emphasize emotional support, intimacy, affection, and maintaining a strong bond. They also focus on meeting needs related to caregiving, security, and companionship.

3. You feel comfortable and close. Getting close to someone isn’t always easy. But in your relationship, you’ve worked through that and are quite comfortable sharing feelings, relying on each other, and being emotionally intimate. Even if vulnerability can be challenging at times, you’ve learned to trust your partner and find it brings you closer. You no longer put up emotional walls and don’t constantly worry about your partner leaving, which provides a sense of stability .

4. You’re more alike than different. You and your partner have a lot in common, and key areas of similarity may help make your relationship more satisfying , new research suggests. Sure, the differences stand out, but beyond those few contrasts, you’re similar in a lot of ways. For example, your partner may enjoy superhero movies while you enjoy rom-coms. Though that feels like a major contrast, you’re both homebodies who enjoy making a meal together then crashing on the couch to watch TV shows where you can debate others’ life choices, make fun of awkward dialogue, and try to guess the next plot twist. Ultimately, you have a lot more in common than you have differences.

Greater Good in Spanish

Read this article in Spanish on La Red Hispana, the public-facing media outlet and distribution house of HCN , focused on educating, inspiring, and informing 40 million U.S. Hispanics.

5. You feel like a team. Words matter. When you talk, do you often use words like “we,” “us,” and “our?” If someone asks, “What’s your favorite show to binge-watch?,” do you reply with, “We have started watching Schitt’s Creek ”? That use of “we” shows a strong sense of cognitive closeness, or shared identity, in your relationship. Research suggests that couples who are interconnected like this tend to be more satisfied and committed .

6. They make you a better person. Your partner helps you refine and improve who you are. Here, your partner doesn’t take charge and tell you how to change, but rather supports your choices for self-growth . Together, you seek out new and interesting experiences that contribute to a feeling of self-development. According to relationship researchers, when you expand and grow as a person, your relationship does, too .

7. You share the power. While partners may have their areas of expertise (for example, one handles lawn care, while the other does interior decorating), partners often share decision making, power, and influence in the relationship. When both partners have a say, relationships are stronger, more satisfied, and more likely to last . And, unsurprisingly, couples are happier when they feel the division of labor in their relationship is fair.

8. They’re fundamentally good. What do people want in a spouse? It’s surprisingly simple: someone who is reliable, warm, kind, fair, trustworthy, and intelligent . Though these traits aren’t flashy and may not immediately come to mind when creating your partner wish list, they provide the foundation for a resilient relationship. Research suggests that when partners have agreeable and emotionally stable personalities, they tend to be more satisfied in their relationship.

9. You trust each other. We need to be able to rely on our partner, which comes from a sense of trust. Not only do we trust our partner with the password to our phone, or with access to our bank account, we know that our partner always has our best interests in mind and will be there for us when we need them. Research suggests this is a positive cycle : Trust encourages greater commitment, which encourages greater trust.

10. You don’t have serious issues. There are problems, and then there are PROBLEMS. Sometimes it’s easy to forget about all of the problems and major red flags we don’t have to deal with. “Dark side” issues like disrespect, cheating, jealousy, and emotional or physical abuse are relationship killers. Sometimes, the light can come from the absence of dark.

Spend a few moments reflecting on how each of these apply to your own relationship. At this point, you may want to give yourself some kind of score to affirm your relationship is in good shape. How many of those 10 pillars do you have? How many do you lack? But that’s not really the point. Chances are, your relationship has elements of all 10. The key is to do a better job of noticing and, where needed, cultivating these foundational areas. Often, strengthening these pillars is as simple as savoring everything in your relationship that works. There’s a lot there when you know what to look for.

Hopefully, you’ve also noticed areas of strength that aren’t on this list. That’s great, because this list is by no means comprehensive. More importantly, it shows you’re starting to notice more of what works, and not obsessing about what’s broken.

Of course, you shouldn’t use a few positives to justify staying in a bad relationship. Focusing on strengths is only helpful for those in good relationships looking to make them better. Good relationships are built on mutual respect, love, and friendship between equals.

The lesson here also isn’t to pretend like your relationship doesn’t have issues. Rather, it’s a lot easier to fix those problems when you appreciate how much of your relationship is already going well. Relationships are difficult enough without making them any harder. When you’re only shedding light on what’s wrong, it’s easy to buy into the mistaken belief that your relationship is in trouble. But when you stop taking the good for granted, and give your partner and relationship more credit, you may realize that your relationship is stronger than you think.

About the Author

Gary W. Lewandowski Jr.

Gary W. Lewandowski Jr., Ph.D. , is the author of Stronger Than You Think: The 10 Blind Spots That Undermine Your Relationship…and How to See Past Them . He is also an award-winning teacher, researcher, relationship expert, and professor at Monmouth University.

You May Also Enjoy

Five ways to renew an old love.

How Love Grows in Your Body

What We Can Learn from the Best Marriages

Three Ways to Improve Your Sex Life in Lockdown

Gratitude is for Lovers

Three Risky Ways to Fall Deeply in Love

- Love & Relationships

The Science Behind Happy Relationships

W hen it comes to relationships , most of us are winging it. We’re exhilarated by the early stages of love , but as we move onto the general grind of everyday life, personal baggage starts to creep in and we can find ourselves floundering in the face of hurt feelings, emotional withdrawal, escalating conflict, insufficient coping techniques and just plain boredom. There’s no denying it: making and keeping happy and healthy relationships is hard.

But a growing field of research into relationships is increasingly providing science-based guidance into the habits of the healthiest, happiest couples — and how to make any struggling relationship better. As we’ve learned, the science of love and relationships boils down to fundamental lessons that are simultaneously simple, obvious and difficult to master: empathy, positivity and a strong emotional connection drive the happiest and healthiest relationships.

Maintaining a strong emotional connection

“The most important thing we’ve learned, the thing that totally stands out in all of the developmental psychology, social psychology and our lab’s work in the last 35 years is that the secret to loving relationships and to keeping them strong and vibrant over the years, to falling in love again and again, is emotional responsiveness,” says Sue Johnson, a clinical psychologist in Ottawa and the author of several books, including Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love .

That responsiveness, in a nutshell, is all about sending a cue and having the other person respond to it. “The $99 million question in love is, ‘Are you there for me?’” says Johnson. “It’s not just, ‘Are you my friend and will you help me with the chores?’ It’s about emotional synchronicity and being tuned in.”

“Every couple has differences,” continues Johnson. “What makes couples unhappy is when they have an emotional disconnection and they can’t get a feeling of secure base or safe haven with this person.” She notes that criticism and rejection — often met with defensiveness and withdrawal — are exceedingly distressing, and something that our brain interprets as a danger cue.

To foster emotional responsiveness between partners, Johnson pioneered Emotionally Focused Therapy , in which couples learn to bond through having conversations that express needs and avoid criticism. “Couples have to learn how to talk about feelings in ways that brings the other person closer,” says Johnson.

Keeping things positive

According to Carrie Cole, director of research for the Gottman Institute , an organization dedicated to the research of marriage, emotional disengagement can easily happen in any relationship when couples are not doing things that create positivity. “When that happens, people feel like they’re just moving further and further apart until they don’t even know each other anymore,” says Cole. That focus on positivity is why the Gottman Institute has embraced the motto “small things often.” The Gottman Lab has been studying relationship satisfaction since the 1970s, and that research drives the Institute’s psychologists to encourage couples to engage in small, routine points of contact that demonstrate appreciation.

One easy place to start is to find ways to compliment your partner every day, says Cole — whether it’s expressing your appreciation for something they’ve done or telling them, specifically, what you love about them. This exercise can accomplish two beneficial things: First, it validates your partner and helps them feel good about themselves. And second, it helps to remind you why you chose that person in the first place.

Listen to the brain, not just your heart

When it comes to the brain and love, biological anthropologist and Kinsey Institute senior fellow Helen Fisher has found — after putting people into a brain scanner — that there are three essential neuro-chemical components found in people who report high relationship satisfaction: practicing empathy, controlling one’s feelings and stress and maintaining positive views about your partner.

In happy relationships, partners try to empathize with each other and understand each other’s perspectives instead of constantly trying to be right. Controlling your stress and emotions boils down to a simple concept: “Keep your mouth shut and don’t act out,” says Fisher. If you can’t help yourself from getting mad, take a break by heading out to the gym, reading a book, playing with the dog or calling a friend — anything to get off a destructive path. Keeping positive views of your partner, which Fisher calls “positive illusions,” are all about reducing the amount of time you spend dwelling on negative aspects of your relationship. “No partner is perfect, and the brain is well built to remember the nasty things that were said,” says Fisher. “But if you can overlook those things and just focus on what’s important, it’s good for the body, good for the mind and good for the relationship.”

Happier relationships, happier life

Ultimately, the quality of a person’s relationships dictates the quality of their life. “Good relationships aren’t just happier and nicer,” says Johnson. “When we know how to heal [relationships] and keep them strong, they make us resilient. All these clichés about how love makes us stronger aren’t just clichés; it’s physiology. Connection with people who love and value us is our only safety net in life.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Putin’s Enemies Are Struggling to Unite

- Women Say They Were Pressured Into Long-Term Birth Control

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- Boredom Makes Us Human

- John Mulaney Has What Late Night Needs

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

127 Relationship Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Relationships are an essential part of human life, shaping our experiences, emotions, and overall well-being. Whether it's with a romantic partner, family member, friend, or colleague, relationships play a crucial role in our daily interactions and personal development. With such a diverse range of relationships in our lives, there are countless topics to explore and discuss when it comes to relationships. In this article, we will provide 127 relationship essay topic ideas and examples to inspire your next writing project.

Romantic Relationships:

- The impact of social media on modern relationships

- The importance of communication in a healthy relationship

- How to maintain a long-distance relationship

- The role of trust in a romantic relationship

- The effects of jealousy in a relationship

- How to navigate conflicts in a relationship

- The benefits of couples therapy

- The impact of love languages on relationship dynamics

- How to keep the spark alive in a long-term relationship

- The role of gender roles in romantic relationships

Family Relationships: 11. The dynamics of sibling relationships 12. The effects of parental divorce on children's relationships 13. The importance of family rituals in strengthening relationships 14. How to improve communication within a family 15. The impact of cultural differences on family relationships 16. The role of family history in shaping relationships 17. How to navigate conflicts with family members 18. The benefits of family therapy 19. The impact of technology on family relationships 20. The challenges of caring for aging parents

Friendships: 21. The qualities of a true friend 22. The benefits of having a diverse group of friends 23. The impact of social media on friendships 24. How to maintain friendships as an adult 25. The role of empathy in friendships 26. The effects of jealousy in friendships 27. The benefits of having a close-knit friend group 28. The impact of moving on friendships 29. How to navigate conflicts with friends 30. The importance of setting boundaries in friendships

Workplace Relationships: 31. The benefits of having strong relationships with colleagues 32. The impact of office politics on workplace relationships 33. The role of communication in workplace relationships 34. How to build trust with coworkers 35. The effects of competition on workplace relationships 36. The benefits of mentorship in the workplace 37. The challenges of managing relationships with superiors 38. The impact of remote work on workplace relationships 39. How to navigate conflicts with coworkers 40. The importance of work-life balance in maintaining healthy relationships

Relationships and Mental Health: 41. The link between healthy relationships and mental well-being 42. The impact of toxic relationships on mental health 43. The benefits of therapy for relationship issues 44. How to set boundaries in relationships for better mental health 45. The effects of loneliness on mental health 46. The role of self-care in maintaining healthy relationships 47. The benefits of support groups for relationship struggles 48. The impact of trauma on interpersonal relationships 49. How to heal from past relationship wounds 50. The importance of self-reflection in improving relationships

Parent-Child Relationships: 51. The effects of different parenting styles on parent-child relationships 52. The benefits of quality time in parent-child relationships 53. The impact of technology on parent-child relationships 54. How to build trust with your child 55. The role of discipline in parent-child relationships 56. The challenges of balancing work and parenting 57. The benefits of family traditions in strengthening parent-child relationships 58. The impact of divorce on parent-child relationships 59. How to navigate conflicts with your child 60. The importance of open communication in parent-child relationships

Interracial Relationships: 61. The challenges of navigating cultural differences in interracial relationships 62. The benefits of interracial relationships 63. The impact of societal perceptions on interracial relationships 64. How to address racism within an interracial relationship 65. The role of family acceptance in interracial relationships 66. The effects of stereotypes on interracial relationships 67. The benefits of diversity in relationships 68. The challenges of raising biracial children 69. How to support your partner in an interracial relationship 70. The importance of celebrating cultural differences in interracial relationships

LGBTQ+ Relationships: 71. The challenges of coming out in a relationship 72. The benefits of LGBTQ+ representation in media on relationships 73. The impact of discrimination on LGBTQ+ relationships 74. How to navigate societal stigma in LGBTQ+ relationships 75. The role of chosen family in LGBTQ+ relationships 76. The effects of internalized homophobia on LGBTQ+ relationships 77. The benefits of LGBTQ+ support groups 78. The challenges of legal recognition for LGBTQ+ relationships 79. How to build a strong support system in an LGBTQ+ relationship 80. The importance of self-acceptance in LGBTQ+ relationships

Relationships and Technology: 81. The impact of dating apps on modern relationships 82. The benefits of virtual relationships 83. The effects of social media on relationship satisfaction 84. How to set boundaries around technology use in relationships 85. The role of video calls in long-distance relationships 86. The challenges of maintaining intimacy in a digital world 87. The benefits of online support groups for relationship issues 88. The impact of sexting on relationships 89. How to navigate conflicts over technology use in relationships 90. The importance of unplugging for better relationship health

Relationships and Self-Discovery: 91. The role of relationships in personal growth 92. The benefits of self-reflection in improving relationships 93. The impact of childhood experiences on adult relationships 94. How to heal from past relationship trauma 95. The challenges of breaking toxic relationship patterns 96. The benefits of therapy for relationship issues 97. The role of mindfulness in improving relationships 98. The effects of self-awareness on relationship dynamics 99. How to cultivate self-love for healthier relationships 100. The importance of setting boundaries for self-preservation

Miscellaneous Relationship Topics: 101. The impact of the pandemic on relationships 102. The benefits of pet relationships on mental health 103. The effects of age gap relationships 104. How to navigate relationships as a single parent 105. The role of forgiveness in repairing broken relationships 106. The benefits of volunteer relationships 107. The impact of codependency on relationships 108. How to build trust after a betrayal 109. The challenges of ending a toxic relationship 110. The benefits of relationship role-playing for communication skills 111. The impact of generational differences on relationships 112. The benefits of mentor-mentee relationships 113. The role of humor in strengthening relationships 114. How to maintain relationships as an introvert 115. The effects of attachment styles on relationship dynamics 116. The benefits of group therapy for relationship issues 117. The impact of substance abuse on relationships 118. How to support a partner with mental health challenges 119. The challenges of blended family relationships 120. The benefits of volunteering together in a relationship 121. The impact of financial stress on relationships 122. How to navigate relationships with different love languages 123. The role of forgiveness in repairing broken relationships 124. The benefits of mutual hobbies in relationships 125. The impact of trauma on relationships 126. How to rebuild trust after infidelity 127. The importance of gratitude in maintaining healthy relationships

In conclusion, relationships are a complex and multifaceted aspect of human life, with endless possibilities for exploration and discussion. Whether you're interested in romantic relationships, family dynamics, friendships, work relationships, or any other type of relationship, there is a wealth of topics to explore and write about. We hope that these 127 relationship essay topic ideas and examples have inspired you to delve deeper into the world of relationships and uncover new insights and perspectives. Happy writing!

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Long-Term Intimate Relationships Research Paper

Thesis statement.

The term long term relationship is commonly used to refer to intimate interaction between persons, which may last for a long period of time or even their lifetime. Such interaction may be or may not necessarily be based on marriage. In an intimate relationship, interaction between persons takes place at a level in which each gets to know the other very well and as a result each is able to adapt to the other’s behavioral patterns. A certain level of trust and opening up towards one another is also evident in this type of relationship. An intimate relationship is also characterized by close physical and emotional interaction (Newman D. M., O’Brien J. (2006).

Intimate relationships have highly been attributed to character formation in individuals. This is because the life of a human being is one continuous process though going through different stages of development. To be able to adapt to these different stages, a human being develops some level of intimacy that contributes greatly to character formation in the person. But although intimacy and character development in humans have been said to be inseparable, the kind of environment in which a human being is living also highly determines the course their development will take. This is through a human beings effort to adapt to their environment (Newman D. M., O’Brien J. (2006).

There are different types of intimate long-term relationships that are notable among humans but the main one remains the marriage relationship. It is upon this relationship that a family is founded and it is from the family set up that human beings learn to develop and adapt into other relationships that may occur in the course of their lives. We also have other relationships within the family that are long term such as father/mother relationship, brother/sister and also all those that one is genetically related to. Other types of relationships are such as romantic relationships, friendships, business as well as professional interactions, which are bound to happen in the course of an individual’s lifetime (Prager K. J.(1995).

Long-term intimate relationships are basically founded upon the kind of interactions that n individual is exposed to in the early stages of their life. In the course of these interactions character formation takes place. Intimacy can be noted in every stage of human development and also throughout an individual’s life. Beginning from birth, human beings develop different aspects that determine character formation and different levels of intimacy in different persons. These aspects are notably emotionality, sociability, impulsivity and activity. Emotionality refers to the human tendency to express negative feeling in an uncontrolled manner. Sociability is the ability to interact with others in a friendly and outgoing manner while activity refers to the level of movement in the course of these interactions. Impulsivity refers to unintentional actions in a person that may result from inability to exercise self-control (Aronson.E. (1999).

The ability in a human being to develop and maintain a long-term intimate relationship is formed in the early stages of life. These early stages are grouped into four different categories beginning with infancy, through childhood to adolescence and then into young adulthood. Each of these stages demands a different style of approach and living and as new needs arise with every new stage, every human being is bound to develop some form of intimate relationships. The first intimate relationship in a human being’s life is the mother–child relationship that develops during infancy. This takes place during the breastfeeding process and as a child sucks of the mother’s breast to get rid of hunger, the satisfaction leads to a long term relationships between the two. This relationship grows stronger in the course of the care giving that a mother gives to her child. The kind of interaction plays a very important role in the formation of other types of relationships that a human being will experience in the course of their life. From this mother/child attachment, young children have the tendency to develop a feeling of security and this brings about confidence and ease when the person gets into other relationships. At this stage, a child learns to love and to be attracted to another human being (Cardillo.M.(1998).

From infanthood, a child grows into the pre-school stage. This is a stage that demands some level of independence from the caregiver or mother, as the child is no longer under their constant care. At this stage a child will develop a need to be recognized as an individual and to exercise some type of freedom. Such kind of needs greatly influences the level of intimacy while relating to the peers. The urge to want to live peaceably with others and the affection the child received during infancy-combined help the child in developing intimate relationships at this stage. There is a tendency at this stage to have attraction to those of the opposite sex. Whatever character traits a child has acquired from the parent are strongly reflected at this stage. Research findings indicate that children who are strongly bonded with their parents during infancy are better fitted socially and tend to develop strong intimate relationships. The type of relationships developed at this stage is mostly based on strong feelings of liking towards another and they form a basis for the kind of relationships in the next stage of life (Cardillo.M.(1998).

The next development stage that provides a good field for the formation of long-term intimate relationships is the adolescence stage. This stage has been referred to as a transitional stage from childhood into adulthood. It is a very difficult stage for children as they try to leave the childish way of life, adapt to adult behavior and at the same time learn to accept themselves as persons. This is also referred to as the discovery stage and new emotional as well as sexual needs are realized at this stage. At this stage, adolescents begin to realize the limitations placed upon them by parents and the urge to take full responsibility of oneself develops. This urge for responsibility and independence requires that the adolescent now distances themselves from the parents and this has been an issue that brings a lot of conflict between parents and the young adults. The adolescent feels the urge to be left to sort out issues their own way and the parent at the same time wants to continue monitoring the child’s way of life. At this stage, the duration spent under the care of the parent decreases and the role of the parent in the adolescent s life changes from dotting mother or father to guardian. Also affected is the role-played by friends in the adolescent’s life. There is a tendency at this stage to relate to those going through the same stage in life. Because the adolescent is exposed to some emotional & physical changes, it is permissible that the type of relationships they are involved in also change so as to conform to new needs and pressures exerted upon their lives. Feelings for love, hate, like or dislike get very strong at this stage and relationships developed at this stage are likely to continue for a long period in the course of a persons life. There is a strong feeling to want to connect to another and this forms a basis for long-term intimate relationships (Cardillo.M.(1998).

At the adolescent stage, there is notable increase in the number of intimate relationships as adolescents form interactions through which they can explore the world and those through which they can identify themselves. Personality traits developed in the earlier stages of pre-school and infancy highly reflect in the type of intimate relationships that are developed at this stage. This is also a very sensitive stage because it is during late adolescence that a human being discovers the kind of changes that affect their personality. An adolescent will tend to look for sameness aid continuity in a relationship. It is at this stage that intimate relationships that occur in early adulthood begin to take shape. Different persons will form different forms of intimate relationships at this stage depending on the depth and level of commitment that they practiced in the earlier stages of life. At this stage, the young adult is highly influenced by curiosity in a bid to find out the meaningfulness and usefulness of things, relationships not excluded. The adolescent has mixed feelings and they are unable to make the difference between loving and liking. Strong liking towards another has often been confused for love at this stage (Mitchell J. J.(1998).

The formation of long-term intimate relationships does not however stop at early adulthood. This process continues on into adulthood, a stage that can be described as not totally secure in the area of intimate relationships. Adulthood is a stage that is characterized by many ups and downs and adaptive measures for coping with so many changes and challenges that affect relationships become very necessary. During adulthood, new people and new situations are an inevitably in one’s life and with the fact that old ones must not be lost altogether the challenges of coping up get even greater. Adulthood is therefore, a stage in which intimacy in long-term relationships is affected by very many factors; most of them external and a high level of maturity are therefore required at this stage. It is at this stage that most of the crucial long-term relationships develop and caution must be taken because it is a stage in which long lasting effects can be realized in an intimate relationship. A lot of care must be taken during interaction so as to balance the different kinds of interactions with different kinds of people. A person for example is not expected to relate to a fellow worker in their place of work in the same way that he/she relates to their wife or husband at home. This is irrespective of the fact that the fellow worker may be of the opposite sex. It is at the adult state that such other long-term relationships as business partnerships also take place. Such type of a relationship is very involving as it affects their economic life as well. High monetary risks are involved in such undertakings that may affect and determine how a person relates with those in the partnerships and also in their family. It is an adventure that requires very high level of trust between individuals. Successful business ventures have often led to long-term intimate relationships between those involved as well as their families. Religious interactions also contribute highly to the formation of long-term intimate relationships at this stage. Love is also very strong at this stage of life and the adult is able to differentiate between like and love. It is at this stage that life partnerships take shape for example the marriage union. Other emotional feelings such as dislike or hate that may have developed in the course of a person’s life are either established or done away with a this stage. This is facilitated by a human being’s ability and capacity to differentiate between good or bad and right or wrong and any relationship developed at this stage will be based on the strong fact of whether it is beneficial to the person or not. At this time of life, an adult has a clear guideline for the type of social groups that they can identify with (Cahn D. D. (1992).

A lot remains to be done in research involving long-term intimate relationships. This is because a lot of research already carried out mainly looks at intimacy in relation to human development. Other strong factors that play a very important role in determining the development long-term intimate relationships such as environmental surroundings have not been given much attention. In the formation of long-term intimate relationships the environment or surroundings that a human being is exposed to greatly determines the type of relationship and the level of intimacy. In the marriage union for example love tends to blossom between people in the same environmental surroundings, that is people who have come to know each other because they live in the same area or because certain situations in life have brought them together under the same environment. Social-cultural factors have also played a very great role in determining the type of long-term intimate relationships that take place in any society. Culture and differences in social interests for example still remain a great hindrance in the establishment of long-term intimate relationships and have also resulted in dissolving of such relationships. In the course of a marriage union for example, a couple may find themselves at loggerheads in the bid to have common friendships, to share what they own and the simple fact that they have to face the future together. The issue of priorities has also been another strong factor affecting the stability of long term intimate relationships. Because at the adult stage most people have already establishes what they value or give priority, it gets hard for many people to make adjustments that will help them cope up with the new situations brought about by a relationship. Where love abides though, there are no cultural, social, economic or racial boundaries. These are just boundaries that humans have tried to establish in the bid to conserve their own different values (Vaughan.D. (1986).

Intimate relationships have been on the decline and those already existing have been characterized by widespread separation and divorce. Although a lot of research has been carried out on separation and divorce, research findings on the factors that lead people to opt out of an intimate relationship are minimal. This is a field that needs extensive research because preserving intimate relationships is preserving society as well (Vaughan.D. (1986).

It is important to note that long-term intimate relationships come in different forms but the most important probably remains that one based on the marriage union. This is because it is the learning ground for every human being and also affects some form of economic security. The marriage union is however a long term intimate relationship that is most threatened by degradation that has mainly resulted from moral decay in society. Stability of the marriage union has been shaken by high rates of separation and divorce as well as the increase in same sex marriages that have been pressing for recognition as long-term intimate relationships. I intimacy is to remain a strong value in society today, a lot must be done to preserve the family as the basic unit through which society is assured of continuity.

Aronson.E. (1999). The Social Animal. W.H. Freeman.

Cahn D. D. (1992). Conflict in Intimate Relationships.Published Guilford Press.

Cardillo.M.(1998). Intimate Relationships: Personality Development Through Interaction During Early Life. 2008. Web.

Mitchell J. J.(1998). The Natural Limitations of Youth: The Predispositions that Shape the… Greenwood Publishing Group.

Newman D. M., O’Brien J. (2006). Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life Pine Forge Press.

Newman D. M., Grauerholz L., Grauerholz.E. (2002). Sociology of Families Published, Pine Forge Press.

Oatley K. , Keltner D., Jenkins J. M. (2006). Understanding Emotions Blackwell Publishing.

Prager K. J.(1995). The Psychology of Intimacy Guilford Press.

Vaughan.D. (1986). Uncoupling: Turning Points in Intimate Relationships. Oxford University Press, US.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, May 12). Long-Term Intimate Relationships. https://ivypanda.com/essays/long-term-intimate-relationships/

"Long-Term Intimate Relationships." IvyPanda , 12 May 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/long-term-intimate-relationships/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Long-Term Intimate Relationships'. 12 May.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Long-Term Intimate Relationships." May 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/long-term-intimate-relationships/.

1. IvyPanda . "Long-Term Intimate Relationships." May 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/long-term-intimate-relationships/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Long-Term Intimate Relationships." May 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/long-term-intimate-relationships/.

- Intimacy and Media Technologies

- Woman Intimacy and Friendship with the Appearance of Social Media

- Culture Influence on Intimacy and Human Relationships

- First Date: Sociological Analysis

- “Sex and the City”: The Question of Monogamy and Polygamy

- Why People Idealize Love but Do Not Practice It

- Love. Characteristics of a True Feeling

- Why Do People Search for Love?

Essays About Love and Relationships: Top 5 Examples

Love, romance, and relationships are just as complicated and messy as they are fascinating. Read our guide on essays about love and relationships.

We, as humans, are social beings. Humanity is inclined towards living with others of our kind and forming relationships with them. Love, whether in a romantic context or otherwise, is essential to a strong relationship with someone. It can be used to describe familial, friendly, or romantic relationships; however, it most commonly refers to romantic partners.

Love and relationships are difficult to understand, but with effort, devotion, and good intentions, they can blossom into something beautiful that will stay with you for life. This is why it is important to be able to discern wisely when choosing a potential partner.

5 Essay Examples

1. love and marriage by kannamma shanmugasundaram, 2. what my short-term relationships taught me about love and life by aaron zhu, 3. true love waits by christine barrett, 4. choosing the right relationship by robert solley, 5. masters of love by emily esfahani smith, 1. what is a healthy romantic relationship, 2. a favorite love story, 3. relationship experiences, 4. lessons relationships can teach you, 5. love and relationships in the 21st century, 6. is marriage necessary for true love.

“In successful love marriages, couples have to learn to look past these imperfections and remember the reasons why they married each other in the first place. They must be able to accept the fact that neither one of them is perfect. Successful love marriages need to set aside these superior, seemingly impossible expectations and be willing to compromise, settling for some good and some bad.”

Shanmugasundaram’s essay looks at marriage in Eastern Cultures, such as her Indian traditions, in which women have less freedom and are often forced into arranged marriages. Shanmugasundaram discusses her differing views with her parents over marriage; they prefer to stick to tradition while she, influenced by Western values, wants to choose for herself. Ultimately, she has compromised with her parents: they will have a say in who she marries, but it will be up to her to make the final decision. She will only marry who she loves.

“There is no forever, I’ve been promised forever by so many exes that it’s as meaningless to me as a homeless person promising me a pot of gold. From here on out, I’m no longer looking for promises of forever, what I want is the promise that you’ll try your best and you’ll be worth it. Don’t promise me forever, promise me that there will be no regrets.”

In Zhu’s essay, he reflects on his lessons regarding love and relationships. His experiences with past partners have taught him many things, including self-worth and the inability to change others. Most interestingly, however, he believes that “forever” does not exist and that going into a relationship, they should commit to as long as possible, not “forever.” Furthermore, they should commit to making the relationship worthwhile without regret.

“For life is a constant change, love is the greatest surprise, friendship is your best defense, maturity comes with responsibility and death is just around the corner, so, expect little, assume nothing, learn from your mistakes, never fail to have faith that true love waits, take care of your friends, treasure your family, moderate your pride and throw up all hatred for God opens millions of flowers without forcing the buds, reminding us not to force our way but to wait for true love to happen perfectly in His time.”

Barrett writes about how teenagers often feel the need to be in a relationship or feel “love” as soon as possible. But unfortunately, our brains are not fully matured in our teenage years, so we are more likely to make mistakes. Barrett discourages teenagers from dating so early; she believes that they should let life take its course and enjoy life at the moment. Her message is that they shouldn’t be in a rush to grow up, for true love will come to those who are patient. You might also be interested in these essays about commitment and essays about girlfriends .

“A paucity of common interests gets blamed when relationships go south, but they are rarely the central problem. Nonetheless, it is good to have some — mostly in terms of having enough in common that there are things that you enjoy spending time doing together. The more important domains to consider are personality and values, and when it comes to personality, the key question is how does your potential partner handle stress.”

Solley, from a more psychological perspective, gives tips on how one can choose the ideal person to be in a relationship with. Love is a lifetime commitment, so much thought should be put into it. One should look at culture, values regarding spending money, and common interests. Solley believes that you should not always look for someone with the same interests, for what makes a relationship interesting is the partners’ differences and how they look past them.

“There are two ways to think about kindness. You can think about it as a fixed trait: Either you have it or you don’t. Or you could think of kindness as a muscle. In some people, that muscle is naturally stronger than in others, but it can grow stronger in everyone with exercise. Masters tend to think about kindness as a muscle. They know that they have to exercise it to keep it in shape. They know, in other words, that a good relationship requires sustained hard work.”

Smith discusses research conducted over many years that explains the different aspects of a relationship, including intimacy, emotional strength, and kindness. She discusses kindness in-depth, saying that a relationship can test your kindness, but you must be willing to work to be kind if you love your partner. You might also be interested in these essays about divorce .

6 Writing Prompts On Essays About Love and Relationships

Everyone has a different idea of what makes a great relationship. For example, some prioritize assertiveness in their partner, while others prefer a calmer demeanor. You can write about different qualities and habits that a healthy, respectful relationship needs, such as quality time and patience. If you have personal experience, reflect on this as well; however, if you don’t, write about what you would hope from your future partner.

Love and relationships have been an essential element in almost every literary work, movie, and television show; an example of each would be Romeo and Juliet , The Fault in Our Stars , and Grey’s Anatomy . Even seemingly unrelated movies, such as the Star Wars and Lord of the Rings franchises, have a romantic component. Describe a love story of your choice; explain its plot, characters, and, most importantly, how the theme of love and relationships is present.

If you have been in a romantic relationship before, or if you are in one currently, reflect on your experience. Why did you pursue this relationship? Explore your relationship’s positive and negative sides and, if applicable, how it ended. If not, write about how you will try and prevent the relationship from ending.

All our experiences in life form us, relationships included. In your essay, reflect on ways romantic relationships can teach you new things and make you better; consider values such as self-worth, patience, and positivity. Then, as with the other prompts, use your personal experiences for a more interesting essay. Hou might find our guide on how to write a vow helpful.

How love, romance, and relationships are perceived has changed dramatically in recent years; from the nuclear family, we have seen greater acceptance of same-sex relationships, blended families, and relationships with more than two partners—research on how the notion of romantic relationships has changed and discuss this in your essay.

More and more people in relationships are deciding not to get married. For a strong argumentative essay, discuss whether you agree with the idea that true love does not require marriage, so it is fine not to get married in the first place. Research the arguments of both sides, then make your claim.

Check out our guide packed full of transition words for essays . If you’re still stuck, check out our general resource of essay writing topics .

Martin is an avid writer specializing in editing and proofreading. He also enjoys literary analysis and writing about food and travel.

View all posts

Long-Term Relationships Essays

“opposites attract” synthesizes the maintenance of long-term relationships through relational dialectic theory, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

12 Elements of Healthy Relationships

In every relationship , it’s important to consider how we treat one an other. Whether it’s romantic , platonic , familial, intimate , or sexual , your relationship with another should be respectful, honest, and fun.

When relationships are healthy, they promote emotional and social well ness . When relationships are unhealthy, you may feel drained, overwhelmed, and invisible .

In a pandemic, it’s even more important to consid er how you engage with others. B oundaries, communication, and time apart are vital to having relationships everyone involved feels good about. Reflect on your current relationships and consider how you can incorporate the elements listed below:

- Communication . The way you talk with friends or partners is an important part of a relationship. Everyone involved should be able to communicate feelings, opinions, and beliefs. When communicating, consider tone and phrasing. Miscommunication often occurs when individuals choose to text versus talking in person or a phone call. Figuring out the best ways to express your feelings together will help eliminate miscommunication.

- Boundaries . Boundaries are physical, emotional, and mental limits or guidelines a person sets for themselves which others need to respect. You and your partners or friends should feel comfortable in the activities you are doing together. All individuals involved should be respectful of boundaries. Whether it’s romantic, sexual, or platonic, consider what you want the relationship to look like and discuss it with the other(s).

- Consent . Consent is important in all relationships. Consent is uncoerced permission to interact with the body or the life of another person. Coercion can look like pressure to do something, physical force, bargaining, or someone holding power over another to get what they want. Consent can look like asking about boundaries in relationships, actively listening to responses, and always respecting those boundaries.

- Trust . Each person in the relationship should have confidence in one another. If you are questioning whether to trust someone, it may be important to communicate your feelings to them. Consider what makes you not trust someone. Is it something they did, or is it something you’ve experienced in other relationships?

- Honesty . Honesty is important for communication. Each person within the relationship or friendship should have the opportunity to express their feelings and concerns. If you don’t feel comfortable being honest with someone, consider why and seek support if needed.

- Independence . It’s important to have time to yourself in any relationship. Having opportunities to hang with others or time for self-care is important to maintain a healthy relationship. If you live with your partner(s) or friend(s), set up designated areas within your place where you can spend time alone.

- Equality . Each person in the relationship should have an equal say in what’s going on. Listen to each other and respect boundaries.

- Support . Each person in the relationship should feel supported. It’s important to have compassion and empathy for one another. In addition to supporting one another, it’s important to recognize your own needs and communicate boundaries around support.

- Responsibility . Some days you may find you said something hurtful or made a mistake. Make sure to take responsibility for your actions and do not place the blame on your partner(s) or friend(s). Taking responsibility for your actions will further trust and honesty.

- Healthy conflict . You may think conflict is a sign of an unhealthy relationship, but talking about issues or disagreements is normal. You won’t find a person that has the exact same interests, opinions, and beliefs as you; thus, at times disagreements may occur. Communicating your feelings and opinions while being respectful and kind is part of a healthy relationship.

- Safety . Safety is the foundation of connection in a relationship. In order to set boundaries, communicate, and have fun, everyone must feel safe. If you do not feel safe to express your feelings, have independence, or anything else on this list, seek support using the resources below.

- Fun . In addition to all these components, you should be enjoying the time you spend with others. Again, it’s important that your relationships promote your well-being and do not diminish it.

Want to learn more about healthy relationships? Check out this quiz by Love is Respect , a project of the National Domestic Violence Hotline .

If you or someone you know is in an unhealthy or abusive relationship, the university has confidential, non-confidential, and peer-led resources you can contact for help and support.

Confidential resources provide assistance and support and information shared is protected and cannot be reported unless given explicit permission from the individual that disclosed; there is imminent threat of harm to the individual or others; the conduct involves suspected abuse of a minor under the age of 18; or otherwise permitted by law or court order.

Non-confidential resources are available to provide support or assistance to individuals but are not confidential and may have broader obligations to report information. Non-confidential resources will report information only to the necessary departments, such as Office of Institutional Equity (OIE).

Peer-led resources are available to provide support and assistance. Services are provided by Johns Hopkins students, and are non-confidential.

Hopkins Confidential Resources

- Counseling Center : 410-516-8278 (press 1 for the on-call counselor). Serves all full-time undergraduate & graduate students from KSAS, WSE, and Peabody.

- Counseling Center Sexual Assault HelpLine: 410-516-7333. Serves all Johns Hopkins students.

- Student Health and Wellness Center : 410-516-4784. Serves all full-time, part-time, and visiting undergraduate and graduate students from KSAS, WSE, and Peabody. Serves post-doctoral fellows enrolled in KSAS, WSE, School of Education, and Sheridan Libraries.

- Religious and Spiritual Life : 410-516-1880.

- Gender Violence Prevention and Education: Alyse Campbell, [email protected] , book a time to chat at: tinyurl.com/MeetwAlyse . Serves all Johns Hopkins students.

- University Health Services (UHS): 410-955-3250

- Mental Health Services : 410-955-1892

- Johns Hopkins Student Assistance Program (JHSAP): 443-287-7000. Serves graduate, medical, and professional students, and immediate family members.

Hopkins Non-confidential Resources

- Hopkins Sexual Assault Response and Prevention website

- Campus Safety and Security : 410-516-7777

- Office of LGBTQ Life : [email protected]

- Office of Institutional Equity : 410-516-8075

- Office of the Dean of Student Life : 410-516-8208

Peer-Led Resources

- Sexual Assault Resource Unit (SARU): Private hotline: 410-516-7887. Serves all Johns Hopkins students.

- A Place to Talk (available on Zoom). Serves Homewood undergrads.

Community Resources

- TurnAround Inc. Hotline : 443-279-0379

- Rape, Abuse, and Incest, National Network : National Sexual Assault Hotline 1-800-656-4673

- Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault (MCASA)

- Love Is Respect

- Environmental (46)

- Financial (49)

- Mental (187)

- Physical (265)

- Professional (160)

- Sexual (68)

- Social (161)

- Spiritual (23)

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

Get Free Access To Our Publishing Tools And Create New Ideas

Sign up to see more

Already a member?

By continuing, you agree to Sociomix's Terms of Service , Privacy Policy

It's Time To express Yourself

Long-term relationships: 13 challenges & how-to overcome them.

Being in love and having someone to share your life with is great. It gives you the opportunity to build a lasting bond on a solid foundation. You share experiences, have fun, and overcome obstacles. But, no matter how unpredictable life can be, eventually, all relationships get stale. It doesn’t matter if you’re in a couple, thruple, or polyamorous relationship, you may need to find ways to keep the excitement alive.

At some point relationship fatigue sets in or it feels like something is missing and you start to wonder if there might be something better out there. Arguments may even come more easily. It’s easy to get stuck in the abyss of imaging a perfect relationship or perfect life when day-to-day responsibilities wear you down. We see characters on TV or read about them in books, and even if we know that it’s fiction, we can’t help but get lost in the fantasy.

According to Dr. Lisa Firestone, Ph.D., there are some things we can do to keep the spark alive as the years tick on in a relationship. We need to be able to laugh, have new experiences, be generous with our love, and communicate openly. It’s also important to make sure either partner doesn’t lose themselves as individuals.

Common long-term relationship challenges and tips to work through them.

1. Questioning your relationship is normal.

Maybe life isn’t going exactly as planned or you’ve noticed a habit of your partners that drives you completely insane. Whatever it may be, at some point, we all question if this is really the person we are going to spend the rest of our life with. The pressure of a lifetime together is a lot. If find yourself questioning if your significant other is really "the one", try imaging a future without them. If that future looks bleak, you’ll know the doubt is worth pushing through.

2. Settling into a routine that feels boring.

At the beginning of a relationship the unknown keeps the excitement alive, and as time goes on that uncertainty fades and you settle into a routine. While this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it can get a bit dull. Combat relationship routine fatigue by trying new things together. This could be as simple as agreeing to try a new restaurant once or week or as extreme as going sky diving. Taking a trip can break the monotony too. Figure out the level of excitement that suits everybody and plan something to shake up the routine.

3. Allowing sex to become an afterthought.

Lack of sex and loss of intimacy are very real issues for a lot of people in relationships. Especially when day-to-day responsibilities take priority over everything else. Research suggests that the frequency of sexual activity decreases with declining health, biological aging, and habituation to sex. This relates significantly to the duration of the relationship.

Even for younger couples, sexual activity and satisfaction drop over time. Just like you carve out time in your day to shower and eat, you might have to plan time to get laid regularly.

If sex has become methodic or non-existent, try role-playing. It might be a little rough to get started, see the clip of Phil and Claire from Modern Family on their first role-playing date below, but the experience will breathe life into a mundane sex life if you let it.

4. Petty arguments can cause long-term harm.

Is it really worth repeating that the toilet seat is up for the 100th time? Probably not. Each person comes into a relationship with their own strengths and in a best-case scenario those strengths balance each other out. Everyone has personal habits and they don’t always make sense to other people so try to avoid ridiculing your partner for something they may be doing without even realizing it.

Habits are hard to build and even harder to break. Petty arguments can lead to heated words which could cause lasting harm. It’s a lot easier to let the little things go than to risk hurting the person you love.

“Maybe I’m an idiot, but you’re definitely an idiot so I guess we’re both married to idiots. At least we have that in common.” – Me, having a petty marital argument with my husband.

5. Criticism is easy to come by so make compliments a priority.

It's easy to be critical of someone else when you’re living with them and while you may have the best of intentions or think you are helping them to see their flaws, real damage can be done to your significant other's morale and confidence. Criticism is going to happen because we just can’t help ourselves when we get comfortable with someone to remove our filter and point out the things we notice. Be aware of it, apologize if necessary, and make it a point to drop compliments regularly so your love knows just how great they are.

6. Major conflicts will lead to trouble if they go unresolved.

It’s important to talk about the big issues as there are things that will put stress on any relationship. Common issues that can lead to major conflicts are clashing over how to handle finances, lack of trust, snooping, being on different levels, and differing opinions on hot button issues. Any disagreement that seems to come up repeatedly will lead to unresolved tension that can affect other areas of your relationship.

For example, you might not want to have a date night if you think your partner is spending too recklessly and in turn, they may see this as you not wanting to spend time with them.

Communication is key with any major dispute. Yell at each other if you have, bottling up anger will only lead to even bigger blowouts later and if you let it fester too long you may never want to let it go. Talk the issue to death, set aside time for it if you have to, just don’t let it sit unresolved. Be honest and open, and speak with “I” statements to convey how the situation makes you feel.

7. The silent treatment feels like winning, but really everybody loses.

The good old silent treatment. I don’t know who came up with this doosey or if it naturally occurred with evolution as people got tired of yelling about the same old nonsense, but it’s a recipe for disaster. When the yelling stops and an issue still hasn’t been resolved, the only course of action seems to be not speaking at all. Stonewalling never works. How long it lasts in any given situation depends on how stubborn the parties involved are. The silent treatment does damage to your relationship and can put other live-in family members in the awkward position of being in the middle.

My husband and I have gone down this road a few times, usually, the tension gets broken by us speaking to the dog with off-hand comments about one another (see #4 about petty arguments, lol). A better way to break the tension is with a smile, hug, or gentle touch. Eventually, you are going to speak to each other again so might as well get to it sooner rather than later.

8. Unwillingness to let go of things that happened in the past.

Everybody has a past, that past includes time before they were in a relationship and time spent in the relationship. We have all done things and some of those things we may just want to forget. If this sounds like the person you love, then stop bringing up those past issues. If the issue is something you previously dealt with in your relationship and has since resolved, then there is no point in dwelling on it.

You're hurting yourself by reliving the past pain and your partner by not allowing them to move on from the wrong. If something happened before your relationship, bringing it up could break the trust built as your partner will feel like opening up to you is only giving you ammo to put them down.

9. You should be growing together, not growing apart.

As a relationship progresses it will be natural for the people in the relationship to change and evolve. Growing together is part of the glue that holds a relationship together. Even if the changes are somewhat different, as long as all parties are on the same path forward, these slight changes won’t rock the boat.

Problems arise with changes when they start to divide that path forward with one partner feeling like they are being left behind. Watch out for potential forks in the road by communicating regularly about how things are going and where you see yourselves and the relationship headed.

10. It’s easy to take your love for granted when it seems so constant.

You feel safe, secure, and stable. If you have a busy life, making it to bed together each night may seem like enough, but not spending enough time together can weaken your bond over time. It’s important to carve out that one on one time to make sure your connection remains steadfast as the years tick on.

11. Spending too much time together will cause you to lose yourself.

Common interests keep love alive, however, this shouldn’t come at the price of a person’s individuality. One of the major red flags is not having friendships outside of your relationship. Make sure that you spend some time apart and doing things with other friends. This also gives you something new to talk about when you’re back together as you can regale your beau with tales of all the fun you had.

12. Temptation exists, and it’s what you do with that temptation that matters.

You may be in an open relationship so the ability to act on temptation is allowed. If you’re not, know that it is completely normal to be attracted to people outside of your relationship and what matters is that you don’t give in to those urges. You don’t have to tell your partner either which can lead to hurt feelings or feeling like they don’t stack up. Let the temptation pass and remind yourself that you have something much better than whatever a quick fling might give you.

13. Comparing your relationship to other people will only lead to disaster.

No two people are alike and by that same token, no two relationships are alike. It’s easy to look at someone else’s union from an outsider's perspective and view it as perfect, but that is rarely the case. There is plenty that you can’t see behind closed doors and social media is only giving you part of the story. It’s okay to ask other people in relationships for advice if you need it, but make sure to keep one-to-one comparisons out of it. If you want to compare anything, compare your relationship against itself over time.

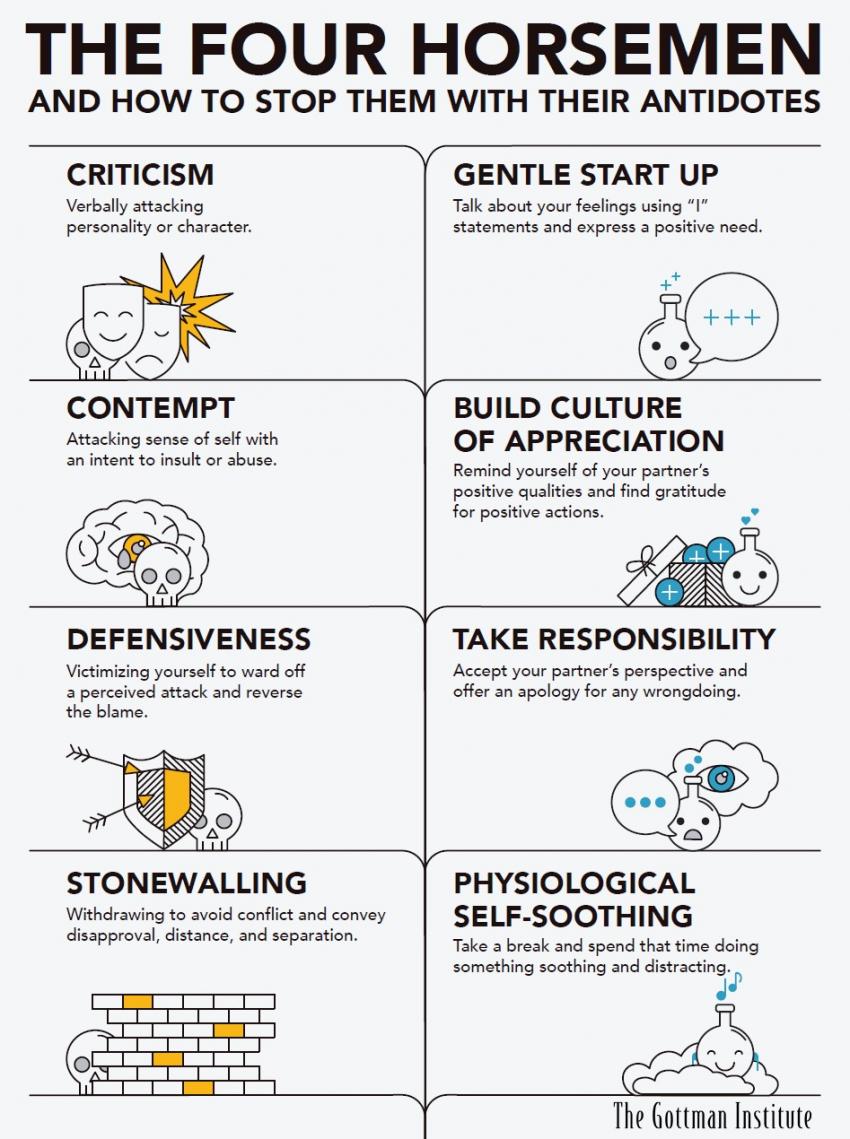

Here’s a guide from The Gottam Institute that touches on some of the issues mentioned above. The Four Horsemen refers to the most destructive behaviors that can destroy a long-term relationship.

Ways to make your long-term relationship a priority and keep your partner(s) from feeling neglected:

- Make an effort to make your partner feel special even if it’s just a small gesture. Not everything has to be over the top, sometimes something as simple as refilling the toilet paper holder when your spouse usually does it can show them that you care.

- Schedule a regular date night. It doesn’t have to be every week, but regularly enough to get out and spend some time “dating”. Rekindle that early relationship excitement by planning a fun day or evening out once in a while.

- Talk about your goals and work toward them together.

- Be open to change as your love evolves and you learn new things. Grow together.

- Communicate regularly, discuss things that are bugging you before they turn into bigger issues, and talk about things that are going well. Make sure to listen when it’s your partner’s turn to speak.

- Respect each other.

- Be willing to forgive. Some things take time to get over, but in order to move forward in a healthy way, you have to be willing to forgive your significant other for mistakes. Let's be clear, mistakes are something like bleaching your black clothes or breaking your favorite vase, and not things like cheating or abuse.

- Not every moment is going to be happy so look for joy even when things get rough. Even if life isn’t going exactly as planned or if you’ve hit a rough patch in your relationship, try to find the happy moments and remember this too shall pass.

- Have a lot of fun together!

Whatever your current relationship status may be, take the time to nurture that bond. Spend time checking in with each other and get excited about sharing new experiences together. Don’t forget to spend some time getting naked too! Sometimes that’s the best way to break the tension during a petty fight.

No Saves yet. Share it with your friends.

Get Free Access To Our Publishing Resources

Independent creators, thought-leaders, experts and individuals with unique perspectives use our free publishing tools to express themselves and create new ideas.

Trending Tags

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. by using sociomix, you agree to our terms & privacy policy.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Performance

Essay On Long-Term Relationship

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Performance , Politics , Government , Company , Contract , Money , Organization , Award

Words: 1800

Published: 03/05/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

With the aid and use of robotics in the mechanical department, the company was in a position to implement and take ideas from conceptual phases to full production in a short period. That meant that the company was ready to not only expand, but also compete for government contracts for exceptional products they would implement. However, for the companies make that a reality, it had to implement and adopt various contracting financing techniques (Newell, 2008). To start with, contract financing, well-defined as the funds transfer from a company that was awarded a contract to the contractor who is the owner of the project. The funds transfer would take the form of advance payments, interim payments, performance based payments, and progress payments. In other words, it was a scheme that was designed specifically to costume the needs of companies that were pursuing financing for a specific contract awarded from the government at a competitive rate (Mukri, 2004). It is from that rationale that this paper will endeavor at elucidating and giving further details on the effects the different approaches used to contract financing would have on a company as well as determining the best approach that would suit an organization. In addition, the paper will be expounding the approaches an organization would require to exist before a government quality would be met.

How the different approaches to contract financing can impact the company

The advance payment is one of the methods or approach used to contract financing having some influence on the company. They include the advance money by the government to the main company that was awarded the contract for the purpose of attaining the performance required. They ought to be liquidated from payments since they are not measured by performance making them different from partial, progress, or other forms of payments of a contract. Progress payments as well bear an influence on the company in that they are made on the grounds that they are incurred by the contracting companies as they continue working on the projects assigned to them (Burman, 2008). However, they do not include other payments that are based on the percentage or payments for partial deliveries that are accepted by government that awarded the contracts. Loan guarantees that are made by the Federal Reserve banks have an influence on the company. That happens since the payments made by the Federal banks enable the companies that have the contract to have access finances from private sources that would be used for the acquisition of services and supplies for the work progress (O’Brien, & Revell, 2005). Partial payments are as well accepted by the companies that were awarded the contracts. In the process, they influence on the supplies and services that stated within the contract during the signing process. Worth noting also about the partial payment is the fact that apart from being a method of payment, but it becomes a method that makes it possible for the contractors to take part in other Government contracts with or without minimal contract financing in the future (Burman, 2008). That becomes possible when the contracts are designed to permit acceptable standards of payment for discrete portions of their tasks once they are awarded the tender by the government. Worth mentioning also is the progress payment since it does influence on how the company awarded the tender conducts its work (Chapin & Fetter, 2002). They influence the company by ensuring that payments are commensurate with the work that they ought to accomplish in the long run.

The best contract financing approach that will best suit the organizational needs

There are various payments that were used in contracting financing as expounded within the paper, and they all are favorable to different companies for different reasons as well. Based on the company’s needs and requirements, the performance-based payment approach would be preferable. That was based on various reasons starting from the scope of the method, to the policy, as well as the standards that were used for the same. Starting for the scope of the payment approach, it was deduced that the method provides policy and procedures that the payment will adhere to under noncommercial purchases as indicated at Subpart 32.1. The other reasons why the method was advantageous to the company leading to its selection was the fact that they are recovered fully in case a default event takes place (Burman, 2008). Similarly, the approach does not include contracts that were awarded through sealed bid procedures, contracts for engineering services or construction, and payments under cost-reimbursement items. The other reason why the contract financing approach best suits the organizational needs and requirements would be traced to the methods criteria of use and application. Under the payment approach, it the contracting managers are allowed to use the method as long as; the contracting manager and the government representative agree on the preference-based payment terms. That implies that the payment will be tailored made for them only rather than following the premeditated payment procedures that would not cover their special needs. In addition to that, the contract as well as the individual order is all fixed-price type acting as an added advantage that the method offers to the contractors (Chapin & Fetter, 2002). The procedures that are to be followed are also advantageous to the company based on the fact that the method may be made either on a whole contract or on a deliverable item basis. Other advantages attributed to the performance based contracting approach, and also explaining why it was preferred. For instance, they utilize alternative and innovative service delivery approach as well as enabling the contracting them achieve higher levels of performance of the contractors (Burman, 2008). Likewise, they allow the governments to decrease the time and efforts spend on contract monitoring; the contractors allow additional compensation and contract extensions for the achievement of superior performance; the approach also allows the governments to minimize service delivery costs. That was because they were only meant to pay for the performance that was achieved or attained.

Policies the organization will need due to presence of The Defense Contract Audit Agency