How to Write a Systematic Review of the Literature

Affiliations.

- 1 1 Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA.

- 2 2 University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

- PMID: 29283007

- DOI: 10.1177/1937586717747384

This article provides a step-by-step approach to conducting and reporting systematic literature reviews (SLRs) in the domain of healthcare design and discusses some of the key quality issues associated with SLRs. SLR, as the name implies, is a systematic way of collecting, critically evaluating, integrating, and presenting findings from across multiple research studies on a research question or topic of interest. SLR provides a way to assess the quality level and magnitude of existing evidence on a question or topic of interest. It offers a broader and more accurate level of understanding than a traditional literature review. A systematic review adheres to standardized methodologies/guidelines in systematic searching, filtering, reviewing, critiquing, interpreting, synthesizing, and reporting of findings from multiple publications on a topic/domain of interest. The Cochrane Collaboration is the most well-known and widely respected global organization producing SLRs within the healthcare field and a standard to follow for any researcher seeking to write a transparent and methodologically sound SLR. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA), like the Cochrane Collaboration, was created by an international network of health-based collaborators and provides the framework for SLR to ensure methodological rigor and quality. The PRISMA statement is an evidence-based guide consisting of a checklist and flowchart intended to be used as tools for authors seeking to write SLR and meta-analyses.

Keywords: evidence based design; healthcare design; systematic literature review.

- Evidence-Based Medicine* / organization & administration

- Research Design*

- Systematic Reviews as Topic*

What is a Systematic Literature Review?

A systematic literature review (SLR) is an independent academic method that aims to identify and evaluate all relevant literature on a topic in order to derive conclusions about the question under consideration. "Systematic reviews are undertaken to clarify the state of existing research and the implications that should be drawn from this." (Feak & Swales, 2009, p. 3) An SLR can demonstrate the current state of research on a topic, while identifying gaps and areas requiring further research with regard to a given research question. A formal methodological approach is pursued in order to reduce distortions caused by an overly restrictive selection of the available literature and to increase the reliability of the literature selected (Tranfield, Denyer & Smart, 2003). A special aspect in this regard is the fact that a research objective is defined for the search itself and the criteria for determining what is to be included and excluded are defined prior to conducting the search. The search is mainly performed in electronic literature databases (such as Business Source Complete or Web of Science), but also includes manual searches (reviews of reference lists in relevant sources) and the identification of literature not yet published in order to obtain a comprehensive overview of a research topic.

An SLR protocol documents all the information gathered and the steps taken as part of an SLR in order to make the selection process transparent and reproducible. The PRISMA flow-diagram support you in making the selection process visible.

In an ideal scenario, experts from the respective research discipline, as well as experts working in the relevant field and in libraries, should be involved in setting the search terms . As a rule, the literature is selected by two or more reviewers working independently of one another. Both measures serve the purpose of increasing the objectivity of the literature selection. An SLR must, then, be more than merely a summary of a topic (Briner & Denyer, 2012). As such, it also distinguishes itself from “ordinary” surveys of the available literature. The following table shows the differences between an SLR and an “ordinary” literature review.

- Charts of BSWL workshop (pdf, 2.88 MB)

- Listen to the interview (mp4, 12.35 MB)

Differences to "common" literature reviews

What are the objectives of slrs.

- Avoidance of research redundancies despite a growing amount of publications

- Identification of research areas, gaps and methods

- Input for evidence-based management, which allows to base management decisions on scientific methods and findings

- Identification of links between different areas of researc

Process steps of an SLR

A SLR has several process steps which are defined differently in the literature (Fink 2014, p. 4; Guba 2008, Transfield et al. 2003). We distinguish the following steps which are adapted to the economics and management research area:

1. Defining research questions

Briner & Denyer (2009, p. 347ff.) have developed the CIMO scheme to establish clearly formulated and answerable research questions in the field of economic sciences:

C – CONTEXT: Which individuals, relationships, institutional frameworks and systems are being investigated?

I – Intervention: The effects of which event, action or activity are being investigated?

M – Mechanisms: Which mechanisms can explain the relationship between interventions and results? Under what conditions do these mechanisms take effect?

O – Outcomes: What are the effects of the intervention? How are the results measured? What are intended and unintended effects?

The objective of the systematic literature review is used to formulate research questions such as “How can a project team be led effectively?”. Since there are numerous interpretations and constructs for “effective”, “leadership” and “project team”, these terms must be particularized.

With the aid of the scheme, the following concrete research questions can be derived with regard to this example:

Under what conditions (C) does leadership style (I) influence the performance of project teams (O)?

Which constructs have an effect upon the influence of leadership style (I) on a project team’s performance (O)?

Research questions do not necessarily need to follow the CIMO scheme, but they should:

- ... be formulated in a clear, focused and comprehensible manner and be answerable;

- ... have been determined prior to carrying out the SLR;

- ... consist of general and specific questions.

As early as this stage, the criteria for inclusion and exclusion are also defined. The selection of the criteria must be well-grounded. This may include conceptual factors such as a geographical or temporal restrictions, congruent definitions of constructs, as well as quality criteria (journal impact factor > x).

2. Selecting databases and other research sources

The selection of sources must be described and explained in detail. The aim is to find a balance between the relevance of the sources (content-related fit) and the scope of the sources.

In the field of economic sciences, there are a number of literature databases that can be searched as part of an SLR. Some examples in this regard are:

- Business Source Complete

- ProQuest One Business

- Web of Science

- EconBiz

Our video " Selecting the right databases " explains how to find relevant databases for your topic.

Literature databases are an important source of research for SLRs, as they can minimize distortions caused by an individual literature selection (selection bias), while offering advantages for a systematic search due to their data structure. The aim is to find all database entries on a topic and thus keep the retrieval bias low (tutorial on retrieval bias ). Besides articles from scientific journals, it is important to inlcude working papers, conference proceedings, etc to reduce the publication bias ( tutorial on publication bias ).

Our online self-study course " Searching economic databases " explains step 2 und 3.

3. Defining search terms

Once the literature databases and other research sources have been selected, search terms are defined. For this purpose, the research topic/questions is/are divided into blocks of terms of equal ranking. This approach is called the block-building method (Guba 2008, p. 63). The so-called document-term matrix, which lists topic blocks and search terms according to a scheme, is helpful in this regard. The aim is to identify as many different synonyms as possible for the partial terms. A precisely formulated research question facilitates the identification of relevant search terms. In addition, keywords from particularly relevant articles support the formulation of search terms.

A document-term matrix for the topic “The influence of management style on the performance of project teams” is shown in this example .

Identification of headwords and keywords

When setting search terms, a distinction must be made between subject headings and keywords, both of which are described below:

- appear in the title, abstract and/or text

- sometimes specified by the author, but in most cases automatically generated

- non-standardized

- different spellings and forms (singular/plural) must be searched separately

Subject headings

- describe the content

- are generated by an editorial team

- are listed in a standardized list (thesaurus)

- may comprise various keywords

- include different spellings

- database-specific

Subject headings are a standardized list of words that are generated by the specialists in charge of some databases. This so-called index of subject headings (thesaurus) helps searchers find relevant articles, since the headwords indicate the content of a publication. By contrast, an ordinary keyword search does not necessarily result in a content-related fit, since the database also displays articles in which, for example, a word appears once in the abstract, even though the article’s content does not cover the topic.

Nevertheless, searches using both headwords and keywords should be conducted, since some articles may not yet have been assigned headwords, or errors may have occurred during the assignment of headwords.

To add headwords to your search in the Business Source Complete database, please select the Thesaurus tab at the top. Here you can find headwords in a new search field and integrate them into your search query. In the search history, headwords are marked with the addition DE (descriptor).

The EconBiz database of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics), which also contains German-language literature, has created its own index of subject headings with the STW Thesaurus for Economics . Headwords are integrated into the search by being used in the search query.

Since the indexes of subject headings divide terms into synonyms, generic terms and sub-aspects, they facilitate the creation of a document-term matrix. For this purpose it is advisable to specify in the document-term matrix the origin of the search terms (STW Thesaurus for Economics, Business Source Complete, etc.).

Searching in literature databases

Once the document-term matrix has been defined, the search in literature databases begins. It is recommended to enter each word of the document-term matrix individually into the database in order to obtain a good overview of the number of hits per word. Finally, all the words contained in a block of terms are linked with the Boolean operator OR and thereby a union of all the words is formed. The latter are then linked with each other using the Boolean operator AND. In doing so, each block should be added individually in order to see to what degree the number of hits decreases.

Since the search query must be set up separately for each database, tools such as LitSonar have been developed to enable a systematic search across different databases. LitSonar was created by Professor Dr. Ali Sunyaev (Institute of Applied Informatics and Formal Description Methods – AIFB) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Advanced search

Certain database-specific commands can be used to refine a search, for example, by taking variable word endings into account (*) or specifying the distance between two words, etc. Our overview shows the most important search commands for our top databases.

Additional searches in sources other than literature databases

In addition to literature databases, other sources should also be searched. Fink (2014, p. 27) lists the following reasons for this:

- the topic is new and not yet included in indexes of subject headings;

- search terms are not used congruently in articles because uniform definitions do not exist;

- some studies are still in the process of being published, or have been completed, but not published.

Therefore, further search strategies are manual search, bibliographic analysis, personal contacts and academic networks (Briner & Denyer, p. 349). Manual search means that you go through the source information of relevant articles and supplement your hit list accordingly. In addition, you should conduct a targeted search for so-called gray literature, that is, literature not distributed via the book trade, such as working papers from specialist areas and conference reports. By including different types of publications, the so-called publication bias (DBWM video “Understanding publication bias” ) – that is, distortions due to exclusive use of articles from peer-reviewed journals – should be kept to a minimum.

The PRESS-Checklist can support you to check the correctness of your search terms.

4. Merging hits from different databases

In principle, large amounts of data can be easily collected, structured and sorted with data processing programs such as Excel. Another option is to use literature management programs such as EndNote, Citavi or Zotero. The Saxon State and University Library Dresden (SLUB Dresden) provides an overview of current literature management programs . Software for qualitative data analysis such as NVivo is equally suited for data processing. A comprehensive overview of the features of different tools that support the SLR process can be found in Bandara et al. (2015).

Our online-self study course "Managing literature with Citavi" shows you how to use the reference management software Citavi.

When conducting an SLR, you should specify for each hit the database from which it originates and the date on which the query was made. In addition, you should always indicate how many hits you have identified in the various databases or, for example, by manual search.

Exporting data from literature databases

Exporting from literature databases is very easy. In Business Source Complete , you must first click on the “Share” button in the hit list, then “Email a link to download exported results” at the very bottom and then select the appropriate format for the respective literature program.

In the Web of Science database, you must select “Export” and select the relevant format. Tip: You can adjust the extracted data fields. Since for example the abstract is not automatically exported, decide which data fields are of interest for you.

Exporting data from the literature database EconBiz is somewhat more complex. Here you must first create a marked list and then select each hit individually and add it to the marked list. Afterwards, articles on the list can be exported.

After merging all hits from the various databases, duplicate entries (duplicates) are deleted.

5. Applying inclusion and exclusion criteria

All publications are evaluated in the literature management program applying the previously defined criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Only those sources that survive this selection process will subsequently be analyzed. The review process and inclusion criteria should be tested with a small sample and adjustments made if necessary before applying it to all articles. In the ideal case, even this selection would be carried out by more than one person, with each working independently of one another. It needs to be made clear how discrepancies between reviewers are dealt with.

The review of the criteria for inclusion and exclusion is primarily based on the title, abstract and subject headings in the databases, as well as on the keywords provided by the authors of a publication in the first step. In a second step the whole article / source will be read.

Within the Citavi literature-management program, you can supplement title data by adding your own fields. In this regard, the criteria for inclusion can be listed individually and marked with 0 in the free text field for being “not fulfilled” and with 1 for being “fulfilled”. In the table view of all titles, you can use the column function to select which columns should be displayed. Here you can include the criteria for inclusion. By exporting the title list to Excel, it is easy to calculate how many titles remain when applying the criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

In addition to the common literature management tools, you can also use software tools that have been developed to support SLRs. The central library of the university in Zurich has published an overview and evaluation of different tools based on a survey among researchers. --> View SLR tools

The selection process needs to be made transparent. The PRISMA flow diagram supports the visualization of the number of included / excluded studies.

Forward and backward search

Should it become apparent that the number of sources found is relatively small, or if you wish to proceed with particular thoroughness, a forward-and-backward search based on the sources found is recommendable (Webster & Watson 2002, p. xvi). A backward search means going through the bibliographies of the sources found. A forward search, by contrast, identifies articles that have cited the relevant publications. The Web of Science and Scopus databases can be used to perform citation analyses.

6. Perform the review

As the next step, the remaining titles are analyzed as to their content by reading them several times in full. Information is extracted according to defined criteria and the quality of the publications is evaluated. If the data extraction is carried out by more than one person, a training ensures that there will be no differences between the reviewers.

Depending on the research questions there exist diffent methods for data abstraction (content analysis, concept matrix etc.). A so-called concept matrix can be used to structure the content of information (Webster & Watson 2002, p. xvii). The image to the right gives an example of a concept matrix according to Becker (2014).

Particularly in the field of economic sciences, the evaluation of a study’s quality cannot be performed according to a generally valid scheme, such as those existing in the field of medicine, for instance. Quality assessment therefore depends largely on the research questions.

Based on the findings of individual studies, a meta-level is then applied to try to understand what similarities and differences exist between the publications, what research gaps exist, etc. This may also result in the development of a theoretical model or reference framework.

Example concept matrix (Becker 2013) on the topic Business Process Management

7. synthesizing results.

Once the review has been conducted, the results must be compiled and, on the basis of these, conclusions derived with regard to the research question (Fink 2014, p. 199ff.). This includes, for example, the following aspects:

- historical development of topics (histogram, time series: when, and how frequently, did publications on the research topic appear?);

- overview of journals, authors or specialist disciplines dealing with the topic;

- comparison of applied statistical methods;

- topics covered by research;

- identifying research gaps;

- developing a reference framework;

- developing constructs;

- performing a meta-analysis: comparison of the correlations of the results of different empirical studies (see for example Fink 2014, p. 203 on conducting meta-analyses)

Publications about the method

Bandara, W., Furtmueller, E., Miskon, S., Gorbacheva, E., & Beekhuyzen, J. (2015). Achieving Rigor in Literature Reviews: Insights from Qualitative Data Analysis and Tool-Support. Communications of the Association for Information Systems . 34(8), 154-204.

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., and Sutton, A. (2012) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: Sage.

Briner, R. B., & Denyer, D. (2012). Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis as a Practice and Scholarship Tool. In Rousseau, D. M. (Hrsg.), The Oxford Handbook of Evidenence Based Management . (S. 112-129). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Durach, C. F., Wieland, A., & Machuca, Jose A. D. (2015). Antecedents and dimensions of supply chain robustness: a systematic literature review . International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistic Management , 46 (1/2), 118-137. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0133

Feak, C. B., & Swales, J. M. (2009). Telling a Research Story: Writing a Literature Review. English in Today's Research World 2. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.309338

Fink, A. (2014). Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper (4. Aufl.). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage Publication.

Fisch, C., & Block, J. (2018). Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Management Review Quarterly, 68, 103–106 (2018). doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0142-x

Guba, B. (2008). Systematische Literaturrecherche. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift , 158 (1-2), S. 62-69. doi: doi.org/10.1007/s10354-007-0500-0 Hart, C. Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination. London: Sage.

Jesson, J. K., Metheson, L. & Lacey, F. (2011). Doing your Literature Review - traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage Publication.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

Petticrew, M. and Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Oxford:Blackwell. Ridley, D. (2012). The literature review: A step-by-step guide . 2nd edn. London: Sage.

Chang, W. and Taylor, S.A. (2016), The Effectiveness of Customer Participation in New Product Development: A Meta-Analysis, Journal of Marketing , American Marketing Association, Los Angeles, CA, Vol. 80 No. 1, pp. 47–64.

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D. & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management , 14 (3), S. 207-222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. Management Information Systems Quarterly , 26(2), xiii-xxiii. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4132319

Durach, C. F., Wieland, A. & Machuca, Jose. A. D. (2015). Antecedents and dimensions of supply chain robustness: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(1/2), 118 – 137.

What is particularly good about this example is that search terms were defined by a number of experts and the review was conducted by three researchers working independently of one another. Furthermore, the search terms used have been very well extracted and the procedure of the literature selection very well described.

On the downside, the restriction to English-language literature brings the language bias into play, even though the authors consider it to be insignificant for the subject area.

Bos-Nehles, A., Renkema, M. & Janssen, M. (2017). HRM and innovative work behaviour: a systematic literature review. Personnel Review, 46(7), pp. 1228-1253

- Only very specific keywords used

- No precise information on how the review process was carried out (who reviewed articles?)

- Only journals with impact factor (publication bias)

Jia, F., Orzes, G., Sartor, M. & Nassimbeni, G. (2017). Global sourcing strategy and structure: towards a conceptual framework. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 37(7), 840-864

- Research questions are explicitly presented

- Search string very detailed

- Exact description of the review process

- 2 persons conducted the review independently of each other

Franziska Klatt

+49 30 314-29778

Privacy notice: The TU Berlin offers a chat information service. If you enable it, your IP address and chat messages will be transmitted to external EU servers. more information

The chat is currently unavailable.

Please use our alternative contact options.

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2024

Systematic literature review of real-world evidence for treatments in HR+/HER2- second-line LABC/mBC after first-line treatment with CDK4/6i

- Veronique Lambert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6984-0038 1 ,

- Sarah Kane ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0006-9341-4836 2 na1 ,

- Belal Howidi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1166-7631 2 na1 ,

- Bao-Ngoc Nguyen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6026-2270 2 na1 ,

- David Chandiwana ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0002-3499-2565 3 ,

- Yan Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0008-3348-9232 1 ,

- Michelle Edwards ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-4292-3140 3 &

- Imtiaz A. Samjoo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1415-8055 2 na1

BMC Cancer volume 24 , Article number: 631 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

366 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors (CDK4/6i) combined with endocrine therapy (ET) are currently recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines as the first-line (1 L) treatment for patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally advanced/metastatic breast cancer (HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC). Although there are many treatment options, there is no clear standard of care for patients following 1 L CDK4/6i. Understanding the real-world effectiveness of subsequent therapies may help to identify an unmet need in this patient population. This systematic literature review qualitatively synthesized effectiveness and safety outcomes for treatments received in the real-world setting after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy in patients with HR+/ HER2- LABC/mBC.

MEDLINE®, Embase, and Cochrane were searched using the Ovid® platform for real-world evidence studies published between 2015 and 2022. Grey literature was searched to identify relevant conference abstracts published from 2019 to 2022. The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (PROSPERO registration: CRD42023383914). Data were qualitatively synthesized and weighted average median real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) was calculated for NCCN/ESMO-recommended post-1 L CDK4/6i treatment regimens.

Twenty records (9 full-text articles and 11 conference abstracts) encompassing 18 unique studies met the eligibility criteria and reported outcomes for second-line (2 L) treatments after 1 L CDK4/6i; no studies reported disaggregated outcomes in the third-line setting or beyond. Sixteen studies included NCCN/ESMO guideline-recommended treatments with the majority evaluating endocrine-based therapy; five studies on single-agent ET, six studies on mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi) ± ET, and three studies with a mix of ET and/or mTORi. Chemotherapy outcomes were reported in 11 studies. The most assessed outcome was median rwPFS; the weighted average median rwPFS was calculated as 3.9 months (3.3-6.0 months) for single-agent ET, 3.6 months (2.5–4.9 months) for mTORi ± ET, 3.7 months for a mix of ET and/or mTORi (3.0–4.0 months), and 6.1 months (3.7–9.7 months) for chemotherapy. Very few studies reported other effectiveness outcomes and only two studies reported safety outcomes. Most studies had heterogeneity in patient- and disease-related characteristics.

Conclusions

The real-world effectiveness of current 2 L treatments post-1 L CDK4/6i are suboptimal, highlighting an unmet need for this patient population.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most diagnosed form of cancer in women with an estimated 2.3 million new cases diagnosed worldwide each year [ 1 ]. BC is the second leading cause of cancer death, accounting for 685,000 deaths worldwide per year [ 2 ]. By 2040, the global burden associated with BC is expected to surpass three million new cases and one million deaths annually (due to population growth and aging) [ 3 ]. Numerous factors contribute to global disparities in BC-related mortality rates, including delayed diagnosis, resulting in a high number of BC cases that have progressed to locally advanced BC (LABC) or metastatic BC (mBC) [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. In the United States (US), the five-year survival rate for patients who progress to mBC is three times lower (31%) than the overall five-year survival rate for all stages (91%) [ 6 , 7 ].

Hormone receptor (HR) positive (i.e., estrogen receptor and/or progesterone receptor positive) coupled with negative human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) expression is the most common subtype of BC, accounting for ∼ 60–70% of all BC cases [ 8 , 9 ]. Historically, endocrine therapy (ET) through estrogen receptor modulation and/or estrogen deprivation has been the standard of care for first-line (1 L) treatment of HR-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2-) mBC [ 10 ]. However, with the approval of the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) palbociclib in combination with the aromatase inhibitor (AI) letrozole in 2015 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 1 L treatment practice patterns have evolved such that CDK4/6i (either in combination with AIs or with fulvestrant) are currently considered the standard of care [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Other CDK4/6i (ribociclib and abemaciclib) in combination with ET are approved for the treatment of HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC; 1 L use of ribociclib in combination with an AI was granted FDA approval in March 2017 for postmenopausal women (with expanded approval in July 2018 for pre/perimenopausal women and for use in 1 L with fulvestrant for patients with disease progression on ET as well as for postmenopausal women), and abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant was granted FDA approval in September 2017 for patients with disease progression following ET and as monotherapy in cases where disease progression occurs following ET and prior chemotherapy in mBC (with expanded approval in February 2018 for use in 1 L in combination with an AI for postmenopausal women) [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ].

Clinical trials investigating the addition of CDK4/6i to ET have demonstrated significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and significant (ribociclib) or numerical (palbociclib and abemaciclib) improvement in overall survival (OS) compared to ET alone in patients with HR+/HER2- advanced or mBC, making this combination treatment the recommended option in the 1 L setting [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. However, disease progression occurs in a significant portion of patients after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment [ 28 ] and the optimal treatment sequence after progression on CDK4/6i remains unclear [ 29 ]. At the time of this review (literature search conducted December 14, 2022), guidelines by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend various options for the treatment of HR+/HER2- advanced BC in the second-line (2 L) setting, including fulvestrant monotherapy, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi; e.g., everolimus) ± ET, alpelisib + fulvestrant (if phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha mutation positive [PIK3CA-m+]), poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) including olaparib or talazoparib (if breast cancer gene/partner and localizer of BRCA2 positive [BRCA/PALB2m+]), and chemotherapy (in cases when a visceral crisis is present) [ 15 , 16 ]. CDK4/6i can also be used in 2 L [ 16 , 30 ]; however, limited data are available to support CDK4/6i rechallenge after its use in the 1 L setting [ 15 ]. Depending on treatments used in the 1 L and 2 L settings, treatment in the third-line setting is individualized based on the patient’s response to prior treatments, tumor load, duration of response, and patient preference [ 9 , 15 ]. Understanding subsequent treatments after 1 L CDK4/6i, and their associated effectiveness, is an important focus in BC research.

Treatment options for HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC continue to evolve, with ongoing research in both clinical trials and in the real-world setting. Real-world evidence (RWE) offers important insights into novel therapeutic regimens and the effectiveness of treatments for HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. The effectiveness of the current treatment options following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy in the real-world setting highlights the unmet need in this patient population and may help to drive further research and drug development. In this study, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to qualitatively summarize the effectiveness and safety of treatment regimens in the real-world setting after 1 L treatment with CDK4/6i in patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC.

Literature search

An SLR was performed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [ 31 ] and reported in alignment with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 32 ] to identify all RWE studies assessing the effectiveness and safety of treatments used for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy and received subsequent treatment in 2 L and beyond (2 L+). The Ovid® platform was used to search MEDLINE® (including Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations), Ovid MEDLINE® Daily, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews by an experienced medical information specialist. The MEDLINE® search strategy was peer-reviewed independently by a senior medical information specialist before execution using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist [ 33 ]. Searches were conducted on December 14, 2022. The review protocol was developed a priori and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO; CRD42023383914) which outlined the population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and study design (PICOS) criteria and methodology used to conduct the review (Table 1 ).

Search strategies utilized a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “HER2 Breast Cancer” or “HR Breast Cancer”) and keywords (e.g., “Retrospective studies”). Vocabulary and syntax were adjusted across databases. Published and validated filters were used to select for study design and were supplemented using additional medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and keywords to select for RWE and nonrandomized studies [ 34 ]. No language restrictions were included in the search strategy. Animal-only and opinion pieces were removed from the results. The search was limited to studies published between January 2015 and December 2022 to reflect the time at which FDA approval was granted for the first CDK4/6i agent (palbociclib) in combination with AI for the treatment of LABC/mBC [ 35 ]. Further search details are presented in Supplementary Material 1 .

Grey literature sources were also searched to identify relevant abstracts and posters published from January 2019 to December 2022 for prespecified relevant conferences including ESMO, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR US), and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR). A search of ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted to validate the findings from the database and grey literature searches.

Study selection, data extraction & weighted average calculation

Studies were screened for inclusion using DistillerSR Version 2.35 and 2.41 (DistillerSR Inc. 2021, Ottawa, Canada) by two independent reviewers based on the prespecified PICOS criteria (Table 1 ). A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any discrepancies during the screening process. Studies were included if they reported RWE on patients aged ≥ 18 years with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC who received 1 L CDK4/6i treatment and received subsequent treatment in 2 L+. Studies were excluded if they reported the results of clinical trials (i.e., non-RWE), were published in any language other than English, and/or were published prior to 2015 (or prior to 2019 for conference abstracts and posters). For studies that met the eligibility criteria, data relating to study design and methodology, details of interventions, patient eligibility criteria and baseline characteristics, and outcome measures such as efficacy, safety, tolerability, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs), were extracted (as available) using a Microsoft Excel®-based data extraction form (Microsoft Corporation, WA, USA). Data extraction was performed by a single reviewer and was confirmed by a second reviewer. Multiple publications identified for the same RWE study, patient population, and setting that reported data for the same intervention were linked and extracted as a single publication. Weighted average median real-world progression-free survival (rwPFS) values were calculated by considering the contribution to the median rwPFS of each study proportional to its respective sample size. These weighted values were then used to compute the overall median rwPFS estimate.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for nonrandomized (cohort) studies was used to assess the risk of bias for published, full-text studies [ 36 ]. The NOS allocates a maximum of nine points for the least risk of bias across three domains: (1) Formation of study groups (four points), (2) Comparability between study groups (two points), (3) Outcome ascertainment (three points). NOS scores can be categorized in three groups: very high risk of bias (0 to 3 points), high risk of bias (4 to 6), and low risk of bias (7 to 9) [ 37 ]. Risk of bias assessment was performed by one reviewer and validated by a second independent reviewer to verify accuracy. Due to limited methodological data by which to assess study quality, risk of bias assessment was not performed on conference abstracts or posters. An amendment to the PROSPERO record (CRD42023383914) for this study was submitted in relation to the quality assessment method (specifying usage of the NOS).

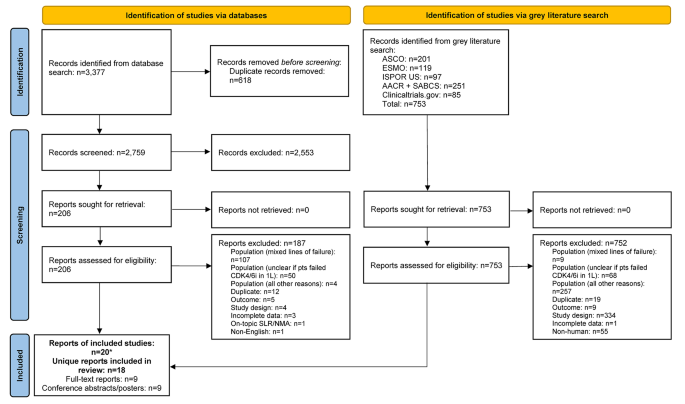

The database search identified 3,377 records; after removal of duplicates, 2,759 were screened at the title and abstract stage of which 2,553 were excluded. Out of the 206 reports retrieved and assessed for eligibility, an additional 187 records were excluded after full-text review; most of these studies were excluded for having patients with mixed lines of CDK4/6i treatment (i.e., did not receive CDK4/6i exclusively in 1 L) (Fig. 1 and Table S1 ). The grey literature search identified 753 records which were assessed for eligibility; of which 752 were excluded mainly due to the population not meeting the eligibility criteria (Fig. 1 ). In total, the literature searches identified 20 records (9 published full-text articles and 11 conference abstracts/posters) representing 18 unique RWE studies that met the inclusion criteria. The NOS quality scores for the included full-text articles are provided in Table S2 . The scores ranged from four to six points (out of a total score of nine) and the median score was five, indicating that all the studies suffered from a high risk of bias [ 37 ].

Most studies were retrospective analyses of chart reviews or medical registries, and all studies were published between 2017 and 2022 (Table S3 ). Nearly half of the RWE studies (8 out of 18 studies) were conducted in the US [ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ], while the remaining studies included sites in Canada, China, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom [ 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 ]. Sample sizes ranged from as few as 4 to as many as 839 patients across included studies, with patient age ranging from 26 to 86 years old.

Although treatment characteristics in the 1 L setting were not the focus of the present review, these details are captured in Table S3 . Briefly, several RWE studies reported 1 L CDK4/6i use in combination with ET (8 out of 18 studies) or as monotherapy (2 out of 18 studies) (Table S3 ). Treatments used in combination with 1 L CDK4/6i included letrozole, fulvestrant, exemestane, and anastrozole. Where reported (4 out of 18 studies), palbociclib was the most common 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. Many studies (8 out of 18 studies) did not report which specific CDK4/6i treatment(s) were used in 1 L or if its administration was in combination or monotherapy.

Characteristics of treatments after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy

Across all studies included in this review, effectiveness and safety data were only available for treatments administered in the 2 L setting after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. No studies were identified that reported outcomes for patients treated in the third-line setting or beyond after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. All 18 studies reported effectiveness outcomes in 2 L, with only two of these studies also describing 2 L safety outcomes. The distribution of outcomes reported in these studies is provided in Table S4 . Studies varied in their reporting of outcomes for 2 L treatments; some studies reported outcomes for a group of 2 L treatments while others described independent outcomes for specific 2 L treatments (i.e., everolimus, fulvestrant, or chemotherapy agents such as eribulin mesylate) [ 42 , 45 , 50 , 54 , 55 ]. Due to the heterogeneity in treatment classes reported in these studies, this data was categorized (as described below) to align with the guidelines provided by NCCN and ESMO [ 15 , 16 ]. The treatment class categorizations for the purpose of this review are: single-agent ET (patients who exclusively received a single-agent ET after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment), mTORi ± ET (patients who exclusively received an mTORi with or without ET after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment), mix of ET and/or mTORi (patients who may have received only ET, only mTORi, and/or both treatments but the studies in this group lacked sufficient information to categorize these patients in the “single-agent ET” or “mTOR ± ET” categories), and chemotherapy (patients who exclusively received chemotherapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment). Despite ESMO and NCCN guidelines indicating that limited evidence exists to support rechallenge with CDK4/6i after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment [ 15 , 16 ], two studies reported outcomes for this treatment approach. Data for such patients were categorized as “ CDK4/6i ± ET ” as it was unclear how many patients receiving CDK4/6i rechallenge received concurrent ET. All other patient groups that lacked sufficient information or did not report outcome/safety data independently (i.e., grouped patients with mixed treatments) to categorize as one of the treatment classes described above were grouped as “ other ”.

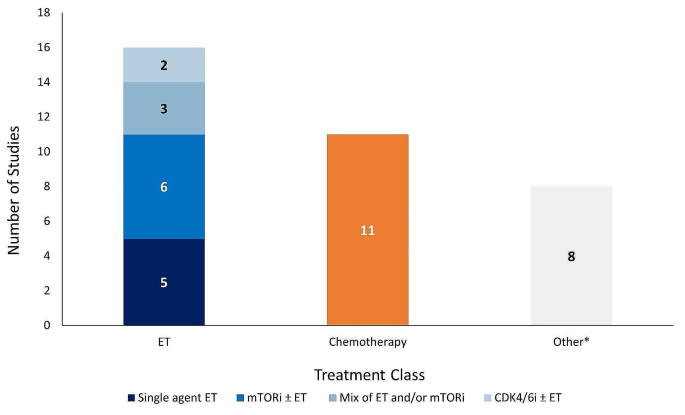

The majority of studies reported effectiveness outcomes for endocrine-based therapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment; five studies for single-agent ET, six studies for mTORi ± ET, and three studies for a mix of ET and/or mTORi (Fig. 2 ). Eleven studies reported effectiveness outcomes for chemotherapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment, and only two studies reported effectiveness outcomes for CDK4/6i rechallenge ± ET. Eight studies that described effectiveness outcomes were grouped into the “other” category. Safety data was only reported in two studies: one study evaluating the chemotherapy agent eribulin mesylate and one evaluating the mTORi everolimus.

Effectiveness outcomes

Real-world progression-free survival

Median rwPFS was described in 13 studies (Tables 2 and Table S5 ). Across the 13 studies, the median rwPFS ranged from 2.5 months [ 49 ] to 17.3 months [ 39 ]. Out of the 13 studies reporting median rwPFS, 10 studies reported median rwPFS for a 2 L treatment recommended by ESMO and NCCN guidelines, which ranged from 2.5 months [ 49 ] to 9.7 months [ 45 ].

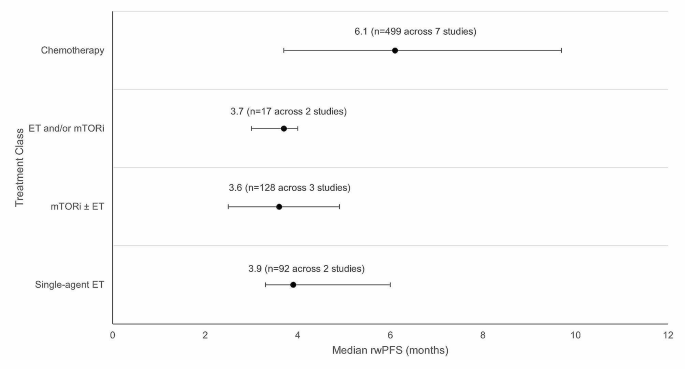

Weighted average median rwPFS was calculated for 2 L treatments recommended by both ESMO and NCCN guidelines (Fig. 3 ). The weighted average median rwPFS for single-agent ET was 3.9 months ( n = 92 total patients) and was derived using data from two studies reporting median rwPFS values of 3.3 months ( n = 70) [ 38 ] and 6.0 months ( n = 22) [ 40 ]. For one study ( n = 7) that reported outcomes for single agent ET, median rwPFS was not reached during the follow-up period; as such, this study was excluded from the weighted average median rwPFS calculation [ 49 ].

The weighted average median rwPFS for mTORi ± ET was 3.6 months ( n = 128 total patients) and was derived based on data from 3 studies with median rwPFS ranging from 2.5 months ( n = 4) [ 49 ] to 4.9 months ( n = 25) [ 54 ] (Fig. 3 ). For patients who received a mix of ET and/or mTORi but could not be classified into the single-agent ET or mTORi ± ET treatment classes, the weighted average median rwPFS was calculated to be 3.7 months ( n = 17 total patients). This was calculated based on data from two studies reporting median rwPFS values of 3.0 months ( n = 5) [ 46 ] and 4.0 months ( n = 12) [ 49 ]. Notably, one study of patients receiving ET and/or everolimus reported a median rwPFS duration of 3.0 months; however, this study was excluded from the weighted average median rwPFS calculation for the ET and/or mTORi class as the sample size was not reported [ 53 ].

The weighted average median rwPFS for chemotherapy was 6.1 months ( n = 499 total patients), calculated using data from 7 studies reporting median rwPFS values ranging from 3.7 months ( n = 249) [ 38 ] to 9.7 months ( n = 121) [ 45 ] (Fig. 3 ). One study with a median rwPFS duration of 5.6 months was not included in the weighted average median rwPFS calculation as the study did not report the sample size [ 53 ]. A second study was excluded from the calculation since the reported median rwPFS was not reached during the study period ( n = 7) [ 41 ].

Although 2 L CDK4/6i ± ET rechallenge lacks sufficient information to support recommendation by ESMO and NCCN guidelines, the limited data currently available for this treatment have shown promising results. Briefly, two studies reported median rwPFS for CDK4/6i ± ET with values of 8.3 months ( n = 302) [ 38 ] and 17.3 months ( n = 165) (Table 2 ) [ 39 ]. The remaining median rwPFS studies reported data for patients classified as “Other” (Table S5 ). The “Other” category included median rwPFS outcomes from seven studies, and included a myriad of treatments (e.g., ET, mTOR + ET, chemotherapy, CDK4/6i + ET, alpelisib + fulvestrant, chidamide + ET) for which disaggregated median rwPFS values were not reported.

Overall survival

Median OS for 2 L treatment was reported in only three studies (Table 2 ) [ 38 , 42 , 43 ]. Across the three studies, the 2 L median OS ranged from 5.2 months ( n = 3) [ 43 ] to 35.7 months ( n = 302) [ 38 ]. Due to the lack of OS data in most of the studies, weighted averages could not be calculated. No median OS data was reported for the single-agent ET treatment class whereas two studies reported median OS for the mTORi ± ET treatment class, ranging from 5.2 months ( n = 3) [ 43 ] to 21.8 months ( n = 54) [ 42 ]. One study reported 2 L median OS of 24.8 months for a single patient treated with chemotherapy [ 43 ]. The median OS data in the CDK4/6i ± ET rechallenge group was 35.7 months ( n = 302) [ 38 ].

Patient mortality was reported in three studies [ 43 , 44 , 45 ]. No studies reported mortality for the single-agent ET treatment class and only one study reported this outcome for the mTORi ± ET treatment class, where 100% of patients died ( n = 3) as a result of rapid disease progression [ 43 ]. For the chemotherapy class, one study reported mortality for one patient receiving 2 L capecitabine [ 43 ]. An additional study reported eight deaths (21.7%) following 1 L CDK4/6i treatment; however, this study did not disclose the 2 L treatments administered to these patients [ 44 ].

Other clinical endpoints

The studies included limited information on additional clinical endpoints; two studies reported on time-to-discontinuation (TTD), two reported on duration of response (DOR), and one each on time-to-next-treatment (TTNT), time-to-progression (TTP), objective response rate (ORR), clinical benefit rate (CBR), and stable disease (Tables 2 and Table S5 ).

Safety, tolerability, and patient-reported outcomes

Safety and tolerability data were reported in two studies [ 40 , 45 ]. One study investigating 2 L administration of the chemotherapy agent eribulin mesylate reported 27 patients (22.3%) with neutropenia, 3 patients (2.5%) with febrile neutropenia, 10 patients (8.3%) with peripheral neuropathy, and 14 patients (11.6%) with diarrhea [ 45 ]. Of these, neutropenia of grade 3–4 severity occurred in 9 patients (33.3%) [ 45 ]. A total of 55 patients (45.5%) discontinued eribulin mesylate treatment; 1 patient (0.83%) discontinued treatment due to adverse events [ 45 ]. Another study reported that 5 out of the 22 patients receiving the mTORi everolimus combined with ET in 2 L (22.7%) discontinued treatment due to toxicity [ 40 ]. PROs were not reported in any of the studies included in the SLR.

The objective of this study was to summarize the existing RWE on the effectiveness and safety of therapies for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. We identified 18 unique studies reporting specifically on 2 L treatment regimens after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. The weighted average median rwPFS for NCCN- and ESMO- guideline recommended 2 L treatments ranged from 3.6 to 3.9 months for ET-based treatments and was 6.1 months when including chemotherapy-based regimens. Treatment selection following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy remains challenging primarily due to the suboptimal effectiveness or significant toxicities (e.g., chemotherapy) associated with currently available options [ 56 ]. These results highlight that currently available 2 L treatments for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC who have received 1 L CDK4/6i are suboptimal, as evidenced by the brief median rwPFS duration associated with ET-based treatments, or notable side effects and toxicity linked to chemotherapy. This conclusion is aligned with a recent review highlighting the limited effectiveness of treatment options for HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC patients post-CDK4/6i treatment [ 56 , 57 ]. Registrational trials which have also shed light on the short median PFS of 2–3 months achieved by ET (i.e., fulvestrant) after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy emphasize the need to develop improved treatment strategies aimed at prolonging the duration of effective ET-based treatment [ 56 ].

The results of this review reveal a paucity of additional real-world effectiveness and safety evidence after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment in HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. OS and DOR were only reported in two studies while other clinical endpoints (i.e., TTD, TTNT, TTP, ORR, CBR, and stable disease) were only reported in one study each. Similarly, safety and tolerability data were only reported in two studies each, and PROs were not reported in any study. This hindered our ability to provide a comprehensive assessment of real-world treatment effectiveness and safety following 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. The limited evidence may be due to the relatively short period of time that has elapsed since CDK4/6i first received US FDA approval for 1 L treatment of HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC (2015) [ 35 ]. As such, almost half of our evidence was informed by conference abstracts. Similarly, no real-world studies were identified in our review that reported outcomes for treatments in the third- or later-lines of therapy after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. The lack of data in this patient population highlights a significant gap which limits our understanding of the effectiveness and safety for patients receiving later lines of therapy. As more patients receive CDK4/6i therapy in the 1 L setting, the number of patients requiring subsequent lines of therapy will continue to grow. Addressing this data gap over time will be critical to improve outcomes for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy.

There are several strengths of this study, including adherence to the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook to ensure a standardized and reliable approach to the SLR [ 58 ] and reporting of the SLR following PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility [ 59 ]. Furthermore, the inclusion of only RWE studies allowed us to assess the effectiveness of current standard of care treatments outside of a controlled environment and enabled us to identify an unmet need in this patient population.

This study had some notable limitations, including the lack of safety and additional effectiveness outcomes reported. In addition, the dearth of studies reporting PROs is a limitation, as PROs provide valuable insight into the patient experience and are an important aspect of assessing the impact of 2 L treatments on patients’ quality of life. The studies included in this review also lacked consistent reporting of clinical characteristics (e.g., menopausal status, sites of metastasis, prior surgery) making it challenging to draw comprehensive conclusions or comparisons based on these factors across the studies. Taken together, there exists an important gap in our understanding of the long-term management of patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. Additionally, the effectiveness results reported in our evidence base were informed by small sample sizes; many of the included studies reported median rwPFS based on less than 30 patients [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 46 , 49 , 51 , 60 ], with two studies not reporting the sample size at all [ 47 , 53 ]. This may impact the generalizability and robustness of the results. Relatedly, the SLR database search was conducted in December 2022; as such, novel agents (e.g., elacestrant and capivasertib + fulvestrant) that have since received FDA approval for the treatment of HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC may impact current 2 L rwPFS outcomes [ 61 , 62 ]. Finally, relative to the number of peer-reviewed full-text articles, this SLR identified eight abstracts and one poster presentation, comprising half (50%) of the included unique studies. As conference abstracts are inherently limited by how much content that can be described due to word limit constraints, this likely had implications on the present synthesis whereby we identified a dearth of real-world effectiveness outcomes in patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC treated with 1 L CDK4/6i therapy.

Future research in this area should aim to address the limitations of the current literature and provide a more comprehensive understanding of optimal sequencing of effective and safe treatment for patients following 1 L CDK4/6i therapy. Specifically, future studies should strive to report robust data related to effectiveness, safety, and PROs for patients receiving 2 L treatment after 1 L CDK4/6i therapy. Future studies should also aim to understand the mechanism underlying CDK4/6i resistance. Addressing these gaps in knowledge may improve the long-term real-world management of patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. A future update of this synthesis may serve to capture a wider breadth of full-text, peer-reviewed articles to gain a more robust understanding of the safety, effectiveness, and real-world treatment patterns for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC. This SLR underscores the necessity for ongoing investigation and the development of innovative therapeutic approaches to address these gaps and improve patient outcomes.

This SLR qualitatively summarized the existing real-world effectiveness data for patients with HR+/HER2- LABC/mBC after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. Results of this study highlight the limited available data and the suboptimal effectiveness of treatments employed in the 2 L setting and underscore the unmet need in this patient population. Additional studies reporting effectiveness and safety outcomes, in addition to PROs, for this patient population are necessary and should be the focus of future research.

PRISMA flow diagram. *Two included conference abstracts reported the same information as already included full-text reports, hence both conference abstracts were not identified as unique. Abbreviations: 1 L = first-line; AACR = American Association of Cancer Research; ASCO = American Society of Clinical Oncology; CDK4/6i = cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ESMO = European Society for Medical Oncology; ISPOR = Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research; n = number of studies; NMA = network meta-analysis; pts = participants; SABCS = San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; SLR = systematic literature review.

Number of studies reporting effectiveness outcomes exclusively for each treatment class. *Studies that lack sufficient information on effectiveness outcomes to classify based on the treatment classes outlined in the legend above. Abbreviations: CDK4/6i = cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ET = endocrine therapy; mTORi = mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor.

Weighted average median rwPFS for 2 L treatments (recommended in ESMO/NCCN guidelines) after 1 L CDK4/6i treatment. Circular dot represents weighted average median across studies. Horizontal bars represent the range of values reported in these studies. Abbreviations: CDK4/6i = cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor; ESMO = European Society for Medical Oncology; ET = endocrine therapy, mTORi = mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor; n = number of patients; NCCN = National Comprehensive Cancer Network; rwPFS = real-world progression-free survival.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023383914).

Abbreviations

Second-line

Second-line treatment setting and beyond

American Association of Cancer Research

Aromatase inhibitor

American Society of Clinical Oncology

- Breast cancer

breast cancer gene/partner and localizer of BRCA2 positive

Clinical benefit rate

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor

Complete response

Duration of response

European Society for Medical Oncology

Food and Drug Administration

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative

Hormone receptor

Hormone receptor positive

Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research

Locally advanced breast cancer

Metastatic breast cancer

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

Medical subject headings

Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

Objective response rate

Poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor

Progression-free survival

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design

Partial response

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Literature Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Patient-reported outcomes

- Real-world evidence

San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium

- Systematic literature review

Time-to-discontinuation

Time-to-next-treatment

Time-to-progression

United States

Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A, Breast, Cancer—Epidemiology. Risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment Strategies—An. Updated Rev Cancers. 2021;13(17):4287.

Google Scholar

World Health Organization (WHO). Breast Cancer Facts Sheet [updated July 12 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer .

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 2022;66:15–23.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1130):20211033.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, Kramer JL, Newman LA, Minihan A et al. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2022;72(6):524– 41.

National Cancer Institute (NIH). Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer [updated 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html .

American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Breast Cancer [ https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html .

Zagami P, Carey LA. Triple negative breast cancer: pitfalls and progress. npj Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):95.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Matutino A, Joy AA, Brezden-Masley C, Chia S, Verma S. Hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: redrawing the lines. Curr Oncol. 2018;25(Suppl 1):S131–41.

Lloyd MR, Wander SA, Hamilton E, Razavi P, Bardia A. Next-generation selective estrogen receptor degraders and other novel endocrine therapies for management of metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: current and emerging role. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221113694.

Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, Papadopoulos E, Aapro M, André F, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO International Consensus guidelines for advanced breast Cancer (ABC 4)†. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1634–57.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

US Food Drug Administration. Palbociclib (Ibrance) 2017 [updated March 31, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/palbociclib-ibrance .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA expands ribociclib indication in HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer 2018 [updated July 18. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-expands-ribociclib-indication-hr-positive-her2-negative-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves abemaciclib for HR positive, HER2-negative breast cancer 2017 [updated Sept 28. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abemaciclib-hr-positive-her2-negative-breast-cancer .

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Breast Cancer 2022 [ https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf .

Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1475–95.

Beaver JA, Amiri-Kordestani L, Charlab R, Chen W, Palmby T, Tilley A, et al. FDA approval: Palbociclib for the Treatment of Postmenopausal Patients with estrogen Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative metastatic breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(21):4760–6.

US Food Drug Administration. Ribociclib (Kisqali) [ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/ribociclib-kisqali#:~:text=On%20March%2013%2C%202017%2C%20the,hormone%20receptor%20(HR)%2Dpositive%2C .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves new treatment for certain advanced or metastatic breast cancers [ https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-certain-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancers .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA expands ribociclib indication in HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer. 2018 [ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-expands-ribociclib-indication-hr-positive-her2-negative-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves abemaciclib as initial therapy for HR-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer [ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-abemaciclib-initial-therapy-hr-positive-her2-negative-metastatic-breast-cancer .

Turner NC, Slamon DJ, Ro J, Bondarenko I, Im S-A, Masuda N, et al. Overall survival with Palbociclib and fulvestrant in advanced breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(20):1926–36.

Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, Fasching PA, De Laurentiis M, Im SA, et al. Phase III randomized study of Ribociclib and Fulvestrant in hormone Receptor-Positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-Negative advanced breast Cancer: MONALEESA-3. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(24):2465–72.

Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, Sohn J, Paluch-Shimon S, Huober J, et al. MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(32):3638–46.

Gopalan PK, Villegas AG, Cao C, Pinder-Schenck M, Chiappori A, Hou W, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition stabilizes disease in patients with p16-null non-small cell lung cancer and is synergistic with mTOR inhibition. Oncotarget. 2018;9(100):37352–66.

Watt AC, Goel S. Cellular mechanisms underlying response and resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2022;24(1):17.

Goetz M. MONARCH 3: final overall survival results of abemaciclib plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor as first-line therapy for HR+, HER2- advanced breast cancer. SABCS; 2023.

Munzone E, Pagan E, Bagnardi V, Montagna E, Cancello G, Dellapasqua S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of post-progression outcomes in ER+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer after CDK4/6 inhibitors within randomized clinical trials. ESMO Open. 2021;6(6):100332.

Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, Cortés J, de Azambuja E, DeMichele A, et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2021;32(12):1475-95.

European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO). ESMO Metastatic Breast Cancer Living Guideline: ER-positive HER2-negative Breast Cancer [updated May 2023. https://www.esmo.org/living-guidelines/esmo-metastatic-breast-cancer-living-guideline/er-positive-her2-negative-breast-cancer .

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Welch PM VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook : Cochrane; 2021.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Fraser C, Murray A, Burr J. Identifying observational studies of surgical interventions in MEDLINE and EMBASE. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):41.

US Food Drug Administration. Palbociclib (Ibrance). Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

GA Wells BS, D O’Connell J, Peterson V, Welch M, Losos PT. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [ https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

Lo CK-L, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):45.

Martin JM, Handorf EA, Montero AJ, Goldstein LJ. Systemic therapies following progression on first-line CDK4/6-inhibitor treatment: analysis of real-world data. Oncologist. 2022;27(6):441–6.

Kalinsky KM, Kruse M, Smyth EN, Guimaraes CM, Gautam S, Nisbett AR et al. Abstract P1-18-37: Treatment patterns and outcomes associated with sequential and non-sequential use of CDK4 and 6i for HR+, HER2- MBC in the real world. Cancer Research. 2022;82(4_Supplement):P1-18-37-P1-18-37.

Choong GM, Liddell S, Ferre RAL, O’Sullivan CC, Ruddy KJ, Haddad TC, et al. Clinical management of metastatic hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer (MBC) after CDK 4/6 inhibitors: a retrospective single-institution study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;196(1):229–37.

Xi J, Oza A, Thomas S, Ademuyiwa F, Weilbaecher K, Suresh R, et al. Retrospective Analysis of Treatment Patterns and effectiveness of Palbociclib and subsequent regimens in metastatic breast Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(2):141–7.

Rozenblit M, Mun S, Soulos P, Adelson K, Pusztai L, Mougalian S. Patterns of treatment with everolimus exemestane in hormone receptor-positive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):14.

Bashour SI, Doostan I, Keyomarsi K, Valero V, Ueno NT, Brown PH, et al. Rapid breast Cancer Disease Progression following cyclin dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitor discontinuation. J Cancer. 2017;8(11):2004–9.

Giridhar KV, Choong GM, Leon-Ferre R, O’Sullivan CC, Ruddy K, Haddad T, et al. Abstract P6-18-09: clinical management of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) after CDK 4/6 inhibitors: a retrospective single-institution study. Cancer Res. 2019;79:P6–18.

Article Google Scholar

Mougalian SS, Feinberg BA, Wang E, Alexis K, Chatterjee D, Knoth RL, et al. Observational study of clinical outcomes of eribulin mesylate in metastatic breast cancer after cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor therapy. Future Oncol. 2019;15(34):3935–44.

Moscetti LML, Riggi L, Sperduti I, Piacentini FOC, Toss A, Barbieri E, Cortesi L, Canino FMA, Zoppoli G, Frassoldati A, Schirone A, Dominici MECF. SEQUENCE OF TREATMENTS AFTER CDK4/6 THERAPY IN ADVANCED BREAST CANCER (ABC), A GOIRC MULTICENTER RETRO/ PROSPECTIVE STUDY. PRELIMINARY RESULTS IN THE RETROSPECTIVE SERIES OF 116 PATIENTS. Tumori. 2022;108(4S):80.

Menichetti AZE, Giorgi CA, Bottosso M, Leporati R, Giarratano T, Barbieri C, Ligorio F, Mioranza E, Miglietta F, Lobefaro R, Faggioni G, Falci C, Vernaci G, Di Liso E, Girardi F, Griguolo G, Vernieri C, Guarneri V, Dieci MV. CDK 4/6 INHIBITORS FOR METASTATIC BREAST CANCER: A MULTICENTER REALWORLD STUDY. Tumori. 2022;108(4S):70.

Marschner NW, Harbeck N, Thill M, Stickeler E, Zaiss M, Nusch A, et al. 232P Second-line therapies of patients with early progression under CDK4/6-inhibitor in first-line– data from the registry platform OPAL. Annals of Oncology. 2022;33:S643-S4

Gousis C, Lowe KMH, Kapiris M. V. Angelis. Beyond First Line CDK4/6 Inhibitors (CDK4/6i) and Aromatase Inhibitors (AI) in Patients with Oestrogen Receptor Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer (ERD MBC): The Guy’s Cancer Centre Experience. Clinical Oncology2022. p. e178.

Endo Y, Yoshimura A, Sawaki M, Hattori M, Kotani H, Kataoka A, et al. Time to chemotherapy for patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast Cancer and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitor use. J Breast Cancer. 2022;25(4):296–306.

Li Y, Li W, Gong C, Zheng Y, Ouyang Q, Xie N, et al. A multicenter analysis of treatment patterns and clinical outcomes of subsequent therapies after progression on palbociclib in HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211022890.

Amaro CP, Batra A, Lupichuk S. First-line treatment with a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor plus an aromatase inhibitor for metastatic breast Cancer in Alberta. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(3):2270–80.

Crocetti SPM, Tassone L, Marcantognini G, Bastianelli L, Della Mora A, Merloni F, Cantini L, Scortichini L, Agostinelli V, Ballatore Z, Savini A, Maccaroni E. Berardi R. What is the best therapeutic sequence for ER-Positive/HER2- Negative metastatic breast cancer in the era of CDK4/6 inhibitors? A single center experience. Tumori. 2020;106(2S).

Nichetti F, Marra A, Giorgi CA, Randon G, Scagnoli S, De Angelis C, et al. 337P Efficacy of everolimus plus exemestane in CDK 4/6 inhibitors-pretreated or naïve HR-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer patients: A secondary analysis of the EVERMET study. Annals of Oncology. 2020;31:S382

Luhn P, O’Hear C, Ton T, Sanglier T, Hsieh A, Oliveri D, et al. Abstract P4-13-08: time to treatment discontinuation of second-line fulvestrant monotherapy for HR+/HER2– metastatic breast cancer in the real-world setting. Cancer Res. 2019;79(4Supplement):P4–13.

Mittal A, Molto Valiente C, Tamimi F, Schlam I, Sammons S, Tolaney SM et al. Filling the gap after CDK4/6 inhibitors: Novel Endocrine and Biologic Treatment options for metastatic hormone receptor positive breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(7).

Ashai N, Swain SM. Post-CDK 4/6 inhibitor therapy: current agents and novel targets. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(6).

Higgins JPTTJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). www.training.cochrane.org/handbook : Cochrane; 2022.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2021;31(1):010502.

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves elacestrant for ER-positive, HER2-negative, ESR1-mutated advanced or metastatic breast cancer [updated January 27 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-elacestrant-er-positive-her2-negative-esr1-mutated-advanced-or-metastatic-breast-cancer .

US Food Drug Administration. FDA approves capivasertib with fulvestrant for breast cancer [updated November 16 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-capivasertib-fulvestrant-breast-cancer .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Joanna Bielecki who developed, conducted, and documented the database searches.

This study was funded by Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA) and Arvinas (New Haven, CT, USA).

Author information

Sarah Kane, Belal Howidi, Bao-Ngoc Nguyen and Imtiaz A. Samjoo contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Pfizer, 10017, New York, NY, USA

Veronique Lambert & Yan Wu

EVERSANA, Burlington, ON, Canada

Sarah Kane, Belal Howidi, Bao-Ngoc Nguyen & Imtiaz A. Samjoo

Arvinas, 06511, New Haven, CT, USA

David Chandiwana & Michelle Edwards

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME participated in the conception and design of the study. IAS, SK, BH and BN contributed to the literature review, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME contributed to the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed for the importance of intellectual content for the work. VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME were responsible for drafting or reviewing the manuscript and for providing final approval. VL, IAS, SK, BH, BN, DC, YW, and ME meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Imtiaz A. Samjoo .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors of this manuscript declare that the research presented was funded by Pfizer Inc. and Arvinas. While the support from Pfizer Inc. and Arvinas was instrumental in facilitating this research, the authors affirm that their interpretation of the data and the content of this manuscript were conducted independently and without bias to maintain the transparency and integrity of the research. IAS, SK, BH, and BN are employees of EVERSANA, Canada, which was a paid consultant to Pfizer in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lambert, V., Kane, S., Howidi, B. et al. Systematic literature review of real-world evidence for treatments in HR+/HER2- second-line LABC/mBC after first-line treatment with CDK4/6i. BMC Cancer 24 , 631 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12269-8

Download citation

Received : 26 January 2024

Accepted : 16 April 2024

Published : 23 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-12269-8

Share this article