Ethical Considerations In Psychology Research

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Ethics refers to the correct rules of conduct necessary when carrying out research. We have a moral responsibility to protect research participants from harm.

However important the issue under investigation, psychologists must remember that they have a duty to respect the rights and dignity of research participants. This means that they must abide by certain moral principles and rules of conduct.

What are Ethical Guidelines?

In Britain, ethical guidelines for research are published by the British Psychological Society, and in America, by the American Psychological Association. The purpose of these codes of conduct is to protect research participants, the reputation of psychology, and psychologists themselves.

Moral issues rarely yield a simple, unambiguous, right or wrong answer. It is, therefore, often a matter of judgment whether the research is justified or not.

For example, it might be that a study causes psychological or physical discomfort to participants; maybe they suffer pain or perhaps even come to serious harm.

On the other hand, the investigation could lead to discoveries that benefit the participants themselves or even have the potential to increase the sum of human happiness.

Rosenthal and Rosnow (1984) also discuss the potential costs of failing to carry out certain research. Who is to weigh up these costs and benefits? Who is to judge whether the ends justify the means?

Finally, if you are ever in doubt as to whether research is ethical or not, it is worthwhile remembering that if there is a conflict of interest between the participants and the researcher, it is the interests of the subjects that should take priority.

Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented. All UK research requires ethical approval by one or more of the following:

- Department Ethics Committee (DEC) : for most routine research.

- Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) : for non-routine research.

- External Ethics Committee (EEC) : for research that s externally regulated (e.g., NHS research).

Committees review proposals to assess if the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in light of the possible risk of physical or psychological harm.

These committees may request researchers make changes to the study’s design or procedure or, in extreme cases, deny approval of the study altogether.

The British Psychological Society (BPS) and American Psychological Association (APA) have issued a code of ethics in psychology that provides guidelines for conducting research. Some of the more important ethical issues are as follows:

Informed Consent

Before the study begins, the researcher must outline to the participants what the research is about and then ask for their consent (i.e., permission) to participate.

An adult (18 years +) capable of being permitted to participate in a study can provide consent. Parents/legal guardians of minors can also provide consent to allow their children to participate in a study.

Whenever possible, investigators should obtain the consent of participants. In practice, this means it is not sufficient to get potential participants to say “Yes.”

They also need to know what it is that they agree to. In other words, the psychologist should, so far as is practicable, explain what is involved in advance and obtain the informed consent of participants.

Informed consent must be informed, voluntary, and rational. Participants must be given relevant details to make an informed decision, including the purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits. Consent must be given voluntarily without undue coercion. And participants must have the capacity to rationally weigh the decision.

Components of informed consent include clearly explaining the risks and expected benefits, addressing potential therapeutic misconceptions about experimental treatments, allowing participants to ask questions, and describing methods to minimize risks like emotional distress.

Investigators should tailor the consent language and process appropriately for the study population. Obtaining meaningful informed consent is an ethical imperative for human subjects research.

The voluntary nature of participation should not be compromised through coercion or undue influence. Inducements should be fair and not excessive/inappropriate.

However, it is not always possible to gain informed consent. Where the researcher can’t ask the actual participants, a similar group of people can be asked how they would feel about participating.

If they think it would be OK, then it can be assumed that the real participants will also find it acceptable. This is known as presumptive consent.

However, a problem with this method is that there might be a mismatch between how people think they would feel/behave and how they actually feel and behave during a study.

In order for consent to be ‘informed,’ consent forms may need to be accompanied by an information sheet for participants’ setting out information about the proposed study (in lay terms), along with details about the investigators and how they can be contacted.

Special considerations exist when obtaining consent from vulnerable populations with decisional impairments, such as psychiatric patients, intellectually disabled persons, and children/adolescents. Capacity can vary widely so should be assessed individually, but interventions to improve comprehension may help. Legally authorized representatives usually must provide consent for children.

Participants must be given information relating to the following:

- A statement that participation is voluntary and that refusal to participate will not result in any consequences or any loss of benefits that the person is otherwise entitled to receive.

- Purpose of the research.

- All foreseeable risks and discomforts to the participant (if there are any). These include not only physical injury but also possible psychological.

- Procedures involved in the research.

- Benefits of the research to society and possibly to the individual human subject.

- Length of time the subject is expected to participate.

- Person to contact for answers to questions or in the event of injury or emergency.

- Subjects” right to confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences.

Debriefing after a study involves informing participants about the purpose, providing an opportunity to ask questions, and addressing any harm from participation. Debriefing serves an educational function and allows researchers to correct misconceptions. It is an ethical imperative.

After the research is over, the participant should be able to discuss the procedure and the findings with the psychologist. They must be given a general idea of what the researcher was investigating and why, and their part in the research should be explained.

Participants must be told if they have been deceived and given reasons why. They must be asked if they have any questions, which should be answered honestly and as fully as possible.

Debriefing should occur as soon as possible and be as full as possible; experimenters should take reasonable steps to ensure that participants understand debriefing.

“The purpose of debriefing is to remove any misconceptions and anxieties that the participants have about the research and to leave them with a sense of dignity, knowledge, and a perception of time not wasted” (Harris, 1998).

The debriefing aims to provide information and help the participant leave the experimental situation in a similar frame of mind as when he/she entered it (Aronson, 1988).

Exceptions may exist if debriefing seriously compromises study validity or causes harm itself, like negative emotions in children. Consultation with an institutional review board guides exceptions.

Debriefing indicates investigators’ commitment to participant welfare. Harms may not be raised in the debriefing itself, so responsibility continues after data collection. Following up demonstrates respect and protects persons in human subjects research.

Protection of Participants

Researchers must ensure that those participating in research will not be caused distress. They must be protected from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend or harm participants.

Normally, the risk of harm must be no greater than in ordinary life, i.e., participants should not be exposed to risks greater than or additional to those encountered in their normal lifestyles.

The researcher must also ensure that if vulnerable groups are to be used (elderly, disabled, children, etc.), they must receive special care. For example, if studying children, ensure their participation is brief as they get tired easily and have a limited attention span.

Researchers are not always accurately able to predict the risks of taking part in a study, and in some cases, a therapeutic debriefing may be necessary if participants have become disturbed during the research (as happened to some participants in Zimbardo’s prisoners/guards study ).

Deception research involves purposely misleading participants or withholding information that could influence their participation decision. This method is controversial because it limits informed consent and autonomy, but can provide otherwise unobtainable valuable knowledge.

Types of deception include (i) deliberate misleading, e.g. using confederates, staged manipulations in field settings, deceptive instructions; (ii) deception by omission, e.g., failure to disclose full information about the study, or creating ambiguity.

The researcher should avoid deceiving participants about the nature of the research unless there is no alternative – and even then, this would need to be judged acceptable by an independent expert. However, some types of research cannot be carried out without at least some element of deception.

For example, in Milgram’s study of obedience , the participants thought they were giving electric shocks to a learner when they answered a question wrongly. In reality, no shocks were given, and the learners were confederates of Milgram.

This is sometimes necessary to avoid demand characteristics (i.e., the clues in an experiment that lead participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for).

Another common example is when a stooge or confederate of the experimenter is used (this was the case in both the experiments carried out by Asch ).

According to ethics codes, deception must have strong scientific justification, and non-deceptive alternatives should not be feasible. Deception that causes significant harm is prohibited. Investigators should carefully weigh whether deception is necessary and ethical for their research.

However, participants must be deceived as little as possible, and any deception must not cause distress. Researchers can determine whether participants are likely distressed when deception is disclosed by consulting culturally relevant groups.

Participants should immediately be informed of the deception without compromising the study’s integrity. Reactions to learning of deception can range from understanding to anger. Debriefing should explain the scientific rationale and social benefits to minimize negative reactions.

If the participant is likely to object or be distressed once they discover the true nature of the research at debriefing, then the study is unacceptable.

If you have gained participants’ informed consent by deception, then they will have agreed to take part without actually knowing what they were consenting to. The true nature of the research should be revealed at the earliest possible opportunity or at least during debriefing.

Some researchers argue that deception can never be justified and object to this practice as it (i) violates an individual’s right to choose to participate; (ii) is a questionable basis on which to build a discipline; and (iii) leads to distrust of psychology in the community.

Confidentiality

Protecting participant confidentiality is an ethical imperative that demonstrates respect, ensures honest participation, and prevents harms like embarrassment or legal issues. Methods like data encryption, coding systems, and secure storage should match the research methodology.

Participants and the data gained from them must be kept anonymous unless they give their full consent. No names must be used in a lab report .

Researchers must clearly describe to participants the limits of confidentiality and methods to protect privacy. With internet research, threats exist like third-party data access; security measures like encryption should be explained. For non-internet research, other protections should be noted too, like coding systems and restricted data access.

High-profile data breaches have eroded public trust. Methods that minimize identifiable information can further guard confidentiality. For example, researchers can consider whether birthdates are necessary or just ages.

Generally, reducing personal details collected and limiting accessibility safeguards participants. Following strong confidentiality protections demonstrates respect for persons in human subjects research.

What do we do if we discover something that should be disclosed (e.g., a criminal act)? Researchers have no legal obligation to disclose criminal acts and must determine the most important consideration: their duty to the participant vs. their duty to the wider community.

Ultimately, decisions to disclose information must be set in the context of the research aims.

Withdrawal from an Investigation

Participants should be able to leave a study anytime if they feel uncomfortable. They should also be allowed to withdraw their data. They should be told at the start of the study that they have the right to withdraw.

They should not have pressure placed upon them to continue if they do not want to (a guideline flouted in Milgram’s research).

Participants may feel they shouldn’t withdraw as this may ‘spoil’ the study. Many participants are paid or receive course credits; they may worry they won’t get this if they withdraw.

Even at the end of the study, the participant has a final opportunity to withdraw the data they have provided for the research.

Ethical Issues in Psychology & Socially Sensitive Research

There has been an assumption over the years by many psychologists that provided they follow the BPS or APA guidelines when using human participants and that all leave in a similar state of mind to how they turned up, not having been deceived or humiliated, given a debrief, and not having had their confidentiality breached, that there are no ethical concerns with their research.

But consider the following examples:

a) Caughy et al. 1994 found that middle-class children in daycare at an early age generally score less on cognitive tests than children from similar families reared in the home.

Assuming all guidelines were followed, neither the parents nor the children participating would have been unduly affected by this research. Nobody would have been deceived, consent would have been obtained, and no harm would have been caused.

However, consider the wider implications of this study when the results are published, particularly for parents of middle-class infants who are considering placing their young children in daycare or those who recently have!

b) IQ tests administered to black Americans show that they typically score 15 points below the average white score.

When black Americans are given these tests, they presumably complete them willingly and are not harmed as individuals. However, when published, findings of this sort seek to reinforce racial stereotypes and are used to discriminate against the black population in the job market, etc.

Sieber & Stanley (1988) (the main names for Socially Sensitive Research (SSR) outline 4 groups that may be affected by psychological research: It is the first group of people that we are most concerned with!

- Members of the social group being studied, such as racial or ethnic group. For example, early research on IQ was used to discriminate against US Blacks.

- Friends and relatives of those participating in the study, particularly in case studies, where individuals may become famous or infamous. Cases that spring to mind would include Genie’s mother.

- The research team. There are examples of researchers being intimidated because of the line of research they are in.

- The institution in which the research is conducted.

salso suggest there are 4 main ethical concerns when conducting SSR:

- The research question or hypothesis.

- The treatment of individual participants.

- The institutional context.

- How the findings of the research are interpreted and applied.

Ethical Guidelines For Carrying Out SSR

Sieber and Stanley suggest the following ethical guidelines for carrying out SSR. There is some overlap between these and research on human participants in general.

Privacy : This refers to people rather than data. Asking people questions of a personal nature (e.g., about sexuality) could offend.

Confidentiality: This refers to data. Information (e.g., about H.I.V. status) leaked to others may affect the participant’s life.

Sound & valid methodology : This is even more vital when the research topic is socially sensitive. Academics can detect flaws in methods, but the lay public and the media often don’t.

When research findings are publicized, people are likely to consider them fact, and policies may be based on them. Examples are Bowlby’s maternal deprivation studies and intelligence testing.

Deception : Causing the wider public to believe something, which isn’t true by the findings, you report (e.g., that parents are responsible for how their children turn out).

Informed consent : Participants should be made aware of how participating in the research may affect them.

Justice & equitable treatment : Examples of unjust treatment are (i) publicizing an idea, which creates a prejudice against a group, & (ii) withholding a treatment, which you believe is beneficial, from some participants so that you can use them as controls.

Scientific freedom : Science should not be censored, but there should be some monitoring of sensitive research. The researcher should weigh their responsibilities against their rights to do the research.

Ownership of data : When research findings could be used to make social policies, which affect people’s lives, should they be publicly accessible? Sometimes, a party commissions research with their interests in mind (e.g., an industry, an advertising agency, a political party, or the military).

Some people argue that scientists should be compelled to disclose their results so that other scientists can re-analyze them. If this had happened in Burt’s day, there might not have been such widespread belief in the genetic transmission of intelligence. George Miller (Miller’s Magic 7) famously argued that we should give psychology away.

The values of social scientists : Psychologists can be divided into two main groups: those who advocate a humanistic approach (individuals are important and worthy of study, quality of life is important, intuition is useful) and those advocating a scientific approach (rigorous methodology, objective data).

The researcher’s values may conflict with those of the participant/institution. For example, if someone with a scientific approach was evaluating a counseling technique based on a humanistic approach, they would judge it on criteria that those giving & receiving the therapy may not consider important.

Cost/benefit analysis : It is unethical if the costs outweigh the potential/actual benefits. However, it isn’t easy to assess costs & benefits accurately & the participants themselves rarely benefit from research.

Sieber & Stanley advise that researchers should not avoid researching socially sensitive issues. Scientists have a responsibility to society to find useful knowledge.

- They need to take more care over consent, debriefing, etc. when the issue is sensitive.

- They should be aware of how their findings may be interpreted & used by others.

- They should make explicit the assumptions underlying their research so that the public can consider whether they agree with these.

- They should make the limitations of their research explicit (e.g., ‘the study was only carried out on white middle-class American male students,’ ‘the study is based on questionnaire data, which may be inaccurate,’ etc.

- They should be careful how they communicate with the media and policymakers.

- They should be aware of the balance between their obligations to participants and those to society (e.g. if the participant tells them something which they feel they should tell the police/social services).

- They should be aware of their own values and biases and those of the participants.

Arguments for SSR

- Psychologists have devised methods to resolve the issues raised.

- SSR is the most scrutinized research in psychology. Ethical committees reject more SSR than any other form of research.

- By gaining a better understanding of issues such as gender, race, and sexuality, we are able to gain greater acceptance and reduce prejudice.

- SSR has been of benefit to society, for example, EWT. This has made us aware that EWT can be flawed and should not be used without corroboration. It has also made us aware that the EWT of children is every bit as reliable as that of adults.

- Most research is still on white middle-class Americans (about 90% of research is quoted in texts!). SSR is helping to redress the balance and make us more aware of other cultures and outlooks.

Arguments against SSR

- Flawed research has been used to dictate social policy and put certain groups at a disadvantage.

- Research has been used to discriminate against groups in society, such as the sterilization of people in the USA between 1910 and 1920 because they were of low intelligence, criminal, or suffered from psychological illness.

- The guidelines used by psychologists to control SSR lack power and, as a result, are unable to prevent indefensible research from being carried out.

American Psychological Association. (2002). American Psychological Association ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. www.apa.org/ethics/code2002.html

Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram’s” Behavioral study of obedience.”. American Psychologist , 19 (6), 421.

Caughy, M. O. B., DiPietro, J. A., & Strobino, D. M. (1994). Day‐care participation as a protective factor in the cognitive development of low‐income children. Child development , 65 (2), 457-471.

Harris, B. (1988). Key words: A history of debriefing in social psychology. In J. Morawski (Ed.), The rise of experimentation in American psychology (pp. 188-212). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1984). Applying Hamlet’s question to the ethical conduct of research: A conceptual addendum. American Psychologist, 39(5) , 561.

Sieber, J. E., & Stanley, B. (1988). Ethical and professional dimensions of socially sensitive research. American psychologist , 43 (1), 49.

The British Psychological Society. (2010). Code of Human Research Ethics. www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/code_of_human_research_ethics.pdf

Further Information

- MIT Psychology Ethics Lecture Slides

BPS Documents

- Code of Ethics and Conduct (2018)

- Good Practice Guidelines for the Conduct of Psychological Research within the NHS

- Guidelines for Psychologists Working with Animals

- Guidelines for ethical practice in psychological research online

APA Documents

APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Process of Conducting Ethical Research in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Tom Merton / Getty Images

Earlier in psychology history, many experiments were performed with highly questionable and even outrageous violations of ethical considerations. Milgram's infamous obedience experiment , for example, involved deceiving human subjects into believing that they were delivering painful, possibly even life-threatening, electrical shocks to another person.

These controversial psychology experiments played a major role in the development of the ethical guidelines and regulations that psychologists must abide by today. When performing studies or experiments that involve human participants, psychologists must submit their proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) for approval. These committees help ensure that experiments conform to ethical and legal guidelines.

Ethical codes, such as those established by the American Psychological Association, are designed to protect the safety and best interests of those who participate in psychological research. Such guidelines also protect the reputations of psychologists, the field of psychology itself and the institutions that sponsor psychology research.

Ethical Guidelines for Research With Human Subjects

When determining ethical guidelines for research , most experts agree that the cost of conducting the experiment must be weighed against the potential benefit to society the research may provide. While there is still a great deal of debate about ethical guidelines, there are some key components that should be followed when conducting any type of research with human subjects.

Participation Must Be Voluntary

All ethical research must be conducted using willing participants. Study volunteers should not feel coerced, threatened or bribed into participation. This becomes especially important for researchers working at universities or prisons, where students and inmates are often encouraged to participate in experiments.

Researchers Must Obtain Informed Consent

Informed consent is a procedure in which all study participants are told about procedures and informed of any potential risks. Consent should be documented in written form. Informed consent ensures that participants know enough about the experiment to make an informed decision about whether or not they want to participate.

Obviously, this can present problems in cases where telling the participants the necessary details about the experiment might unduly influence their responses or behaviors in the study. The use of deception in psychology research is allowed in certain instances, but only if the study would be impossible to conduct without the use of deception, if the research will provide some sort of valuable insight and if the subjects will be debriefed and informed about the study's true purpose after the data has been collected.

Researchers Must Maintain Participant Confidentiality

Confidentiality is an essential part of any ethical psychology research. Participants need to be guaranteed that identifying information and individual responses will not be shared with anyone who is not involved in the study.

While these guidelines provide some ethical standards for research, each study is different and may present unique challenges. Because of this, most colleges and universities have a Human Subjects Committee or Institutional Review Board that oversees and grants approval for any research conducted by faculty members or students. These committees provide an important safeguard to ensure academic research is ethical and does not pose a risk to study participants.

American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 13 July 2021

Assisting you to advance with ethics in research: an introduction to ethical governance and application procedures

- Shivadas Sivasubramaniam 1 ,

- Dita Henek Dlabolová 2 ,

- Veronika Kralikova 3 &

- Zeenath Reza Khan 3

International Journal for Educational Integrity volume 17 , Article number: 14 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

12 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Ethics and ethical behaviour are the fundamental pillars of a civilised society. The focus on ethical behaviour is indispensable in certain fields such as medicine, finance, or law. In fact, ethics gets precedence with anything that would include, affect, transform, or influence upon individuals, communities or any living creatures. Many institutions within Europe have set up their own committees to focus on or approve activities that have ethical impact. In contrast, lesser-developed countries (worldwide) are trying to set up these committees to govern their academia and research. As the first European consortium established to assist academic integrity, European Network for Academic Integrity (ENAI), we felt the importance of guiding those institutions and communities that are trying to conduct research with ethical principles. We have established an ethical advisory working group within ENAI with the aim to promote ethics within curriculum, research and institutional policies. We are constantly researching available data on this subject and committed to help the academia to convey and conduct ethical behaviour. Upon preliminary review and discussion, the group found a disparity in understanding, practice and teaching approaches to ethical applications of research projects among peers. Therefore, this short paper preliminarily aims to critically review the available information on ethics, the history behind establishing ethical principles and its international guidelines to govern research.

The paper is based on the workshop conducted in the 5th International conference Plagiarism across Europe and Beyond, in Mykolas Romeris University, Lithuania in 2019. During the workshop, we have detailed a) basic needs of an ethical committee within an institution; b) a typical ethical approval process (with examples from three different universities); and c) the ways to obtain informed consent with some examples. These are summarised in this paper with some example comparisons of ethical approval processes from different universities. We believe this paper will provide guidelines on preparing and training both researchers and research students in appropriately upholding ethical practices through ethical approval processes.

Introduction

Ethics and ethical behaviour (often linked to “responsible practice”) are the fundamental pillars of a civilised society. Ethical behaviour with integrity is important to maintain academic and research activities. It affects everything we do, and gets precedence with anything that would include/affect, transform, or impact upon individuals, communities or any living creatures. In other words, ethics would help us improve our living standards (LaFollette, 2007 ). The focus on ethical behaviour is indispensable in certain fields such as medicine, finance, or law, but is also gaining recognition in all disciplines engaged in research. Therefore, institutions are expected to develop ethical guidelines in research to maintain quality, initiate/own integrity and above all be transparent to be successful by limiting any allegation of misconduct (Flite and Harman, 2013 ). This is especially true for higher education organisations that promote research and scholarly activities. Many European institutions have developed their own regulations for ethics by incorporating international codes (Getz, 1990 ). The lesser developed countries are trying to set up these committees to govern their academia and research. World Health Organization has stated that adhering to “ ethical principles … [is central and important]... in order to protect the dignity, rights and welfare of research participants ” (WHO, 2021 ). Ethical guidelines taught to students can help develop ethical researchers and members of society who uphold values of ethical principles in practice.

As the first European-wide consortium established to assist academic integrity (European Network for Academic Integrity – ENAI), we felt the importance of guiding those institutions and communities that are trying to teach, research, and include ethical principles by providing overarching understanding of ethical guidelines that may influence policy. Therefore, we set up an advisory working group within ENAI in 2018 to support matters related to ethics, ethical committees and assisting on ethics related teaching activities.

Upon preliminary review and discussion, the group found a disparity in understanding, practice and teaching approaches to ethical applications among peers. This became the premise for this research paper. We first carried out a literature survey to review and summarise existing ethical governance (with historical perspectives) and procedures that are already in place to guide researchers in different discipline areas. By doing so, we attempted to consolidate, document and provide important steps in a typical ethical application process with example procedures from different universities. Finally, we attempted to provide insights and findings from practical workshops carried out at the 5th International Conference Plagiarism across Europe and Beyond, in Mykolas Romeris University, Lithuania in 2019, focussing on:

• highlighting the basic needs of an ethical committee within an institution,

• discussing and sharing examples of a typical ethical approval process,

• providing guidelines on the ways to teach research ethics with some examples.

We believe this paper provides guidelines on preparing and training both researchers and research students in appropriately upholding ethical practices through ethical approval processes.

Background literature survey

Responsible research practice (RRP) is scrutinised by the aspects of ethical principles and professional standards (WHO’s Code of Conduct for responsible Research, 2017). The Singapore statement on research integrity (The Singapore Statement on Research integrity, 2010) has provided an internationally acceptable guidance for RRP. The statement is based on maintaining honesty, accountability, professional courtesy in all aspects of research and maintaining fairness during collaborations. In other words, it does not simply focus on the procedural part of the research, instead covers wider aspects of “integrity” beyond the operational aspects (Israel and Drenth, 2016 ).

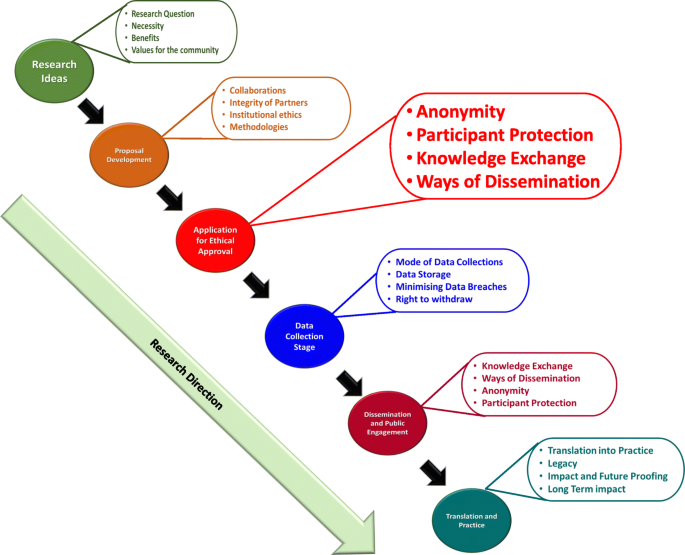

Institutions should focus on providing ethical guidance based on principles and values reflecting upon all aspects/stages of research (from the funding application/project development stage upto or beyond project closing stage). Figure 1 summarizes the different aspects/stages of a typical research and highlights the needs of RRP in compliance with ethical governance at each stage with examples (the figure is based on Resnik, 2020 ; Žukauskas et al., 2018 ; Anderson, 2011 ; Fouka and Mantzorou, 2011 ).

Summary of the enabling ethical governance at different stages of research. Note that it is imperative for researchers to proactively consider the ethical implications before, during and after the actual research process. The summary shows that RRP should be in line with ethical considerations even long before the ethical approval stage

Individual responsibilities to enhance RRP

As explained in Fig. 1 , a successfully governed research should consider ethics at the planning stages prior to research. Many international guidance are compatible in enforcing/recommending 14 different “responsibilities” that were first highlighted in the Singapore Statement (2010) for researchers to follow and achieve competency in RRP. In order to understand the purpose and the expectation of these ethical guidelines, we have carried out an initial literature survey on expected individual responsibilities. These are summarised in Table 1 .

By following these directives, researchers can carry out accountable research by maximising ethical self-governance whilst minimising misconducts. In our own experiences of working with many researchers, their focus usually revolves around ethical “clearance” rather than behaviour. In other words, they perceive this as a paper exercise rather than trying to “own” ethical behaviour in everything they do. Although the ethical principles and responsibilities are explicitly highlighted in the majority of international guidelines [such as UK’s Research Governance Policy (NICE, 2018 ), Australian Government’s National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (Difn website a - National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (NSECHR), 2018 ), the Singapore Statement (2010) etc.]; and the importance of holistic approach has been argued in ethical decision making, many researchers and/or institutions only focus on ethics linked to the procedural aspects.

Studies in the past have also highlighted inconsistencies in institutional guidelines pointing to the fact that these inconsistencies may hinder the predicted research progress (Desmond & Dierickx 2021 ; Alba et al., 2020 ; Dellaportas et al., 2014 ; Speight 2016 ). It may also be possible that these were and still are linked to the institutional perceptions/expectations or the pre-empting contextual conditions that are imposed by individual countries. In fact, it is interesting to note many research organisations and HE institutions establish their own policies based on these directives.

Research governance - origins, expectations and practices

Ethical governance in clinical medicine helps us by providing a structure for analysis and decision-making. By providing workable definitions of benefits and risks as well as the guidance for evaluating/balancing benefits over risks, it supports the researchers to protect the participants and the general population.

According to the definition given by National Institute of Clinical care Excellence, UK (NICE 2018 ), “ research governance can be defined as the broad range of regulations, principles and standards of good practice that ensure high quality research ”. As stated above, our literature-based research survey showed that most of the ethical definitions are basically evolved from the medical field and other disciplines have utilised these principles to develop their own ethical guidance. Interestingly, historical data show that the medical research has been “self-governed” or in other words implicated by the moral behaviour of individual researchers (Fox 2017 ; Shaw et al., 2005 ; Getz, 1990 ). For example, early human vaccination trials conducted in 1700s used the immediate family members as test subjects (Fox, 2017 ). Here the moral justification might have been the fact that the subjects who would have been at risk were either the scientists themselves or their immediate families but those who would reap the benefits from the vaccination were the general public/wider communities. However, according to the current ethical principles, this assumption is entirely not acceptable.

Historically, ambiguous decision-making and resultant incidences of research misconduct have led to the need for ethical research governance in as early as the 1940’s. For instance, the importance of an international governance was realised only after the World War II, when people were astonished to note the unethical research practices carried out by Nazi scientists. As a result of this, in 1947 the Nuremberg code was published. The code mainly focussed on the following:

Informed consent and further insisted the research involving humans should be based on prior animal work,

The anticipated benefits should outweigh the risk,

Research should be carried out only by qualified scientists must conduct research,

Avoiding physical and mental suffering and.

Avoiding human research that would result in which death or disability.

(Weindling, 2001 ).

Unfortunately, it was reported that many researchers in the USA and elsewhere considered the Nuremberg code as a document condemning the Nazi atrocities, rather than a code for ethical governance and therefore ignored these directives (Ghooi, 2011 ). It was only in 1964 that the World Medical Association published the Helsinki Declaration, which set the stage for ethical governance and the implementation of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) process (Shamoo and Irving, 1993 ). This declaration was based on Nuremberg code. In addition, the declaration also paved the way for enforcing research being conducted in accordance with these guidelines.

Incidentally, the focus on research/ethical governance gained its momentum in 1974. As a result of this, a report on ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research was published in 1979 (The Belmont Report, 1979 ). This report paved the way to the current forms of ethical governance in biomedical and behavioural research by providing guidance.

Since 1994, the WHO itself has been providing several guidance to health care policy-makers, researchers and other stakeholders detailing the key concepts in medical ethics. These are specific to applying ethical principles in global public health.

Likewise, World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), and International Convention for the Protection of Animals (ICPA) provide guidance on animal welfare in research. Due to this continuous guidance, together with accepted practices, there are internationally established ethical guidelines to carry out medical research. Our literature survey further identified freely available guidance from independent organisations such as COPE (Committee of Publication Ethics) and ALLEA (All European Academics) which provide support for maintaining research ethics in other fields such as education, sociology, psychology etc. In reality, ethical governance is practiced differently in different countries. In the UK, there is a clinical excellence research governance, which oversees all NHS related medical research (Mulholland and Bell, 2005 ). Although, the governance in other disciplines is not entirely centralised, many research funding councils and organisations [such as UKRI (UK-Research and Innovation; BBSC (Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council; MRC (Medical Research Council); EPSRC (Economic and Social Research Council)] provide ethical governance and expect institutional adherence and monitoring. They expect local institutional (i.e. university/institutional) research governance for day-to-day monitoring of the research conducted within the organisation and report back to these funding bodies, monthly or annually (Department of Health, 2005). Likewise, there are nationally coordinated/regulated ethics governing bodies such as the US Office for Human Research Protections (US-OHRP), National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) in the USA and Canada respectively (Mulholland and Bell, 2005 ). The OHRP in the USA formally reviews all research activities involving human subjects. On the other hand, in Canada, CIHR works with the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). They together have produced a Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS) (Stephenson et al., 2020 ) as ethical governance. All Canadian institutions are expected to adhere to this policy for conducting research. As for Australia, the research is governed by the Australian code for the responsible conduct of research (2008). It identifies the responsibilities of institutions and researchers in all areas of research. The code has been jointly developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Australian Research Council (ARC) and Universities Australia (UA). This information is summarized in Table 2 .

Basic structure of an institutional ethical advisory committee (EAC)

The WHO published an article defining the basic concepts of an ethical advisory committee in 2009 (WHO, 2009 - see above). According to this, many countries have established research governance and monitor the ethical practice in research via national and/or regional review committees. The main aims of research ethics committees include reviewing the study proposals, trying to understand the justifications for human/animal use, weighing the merits and demerits of the usage (linking to risks vs. potential benefits) and ensuring the local, ethical guidelines are followed Difn website b - Enago academy Importance of Ethics Committees in Scholarly Research, 2020 ; Guide for Research Ethics - Council of Europe, 2014 ). Once the research has started, the committee needs to carry out periodic surveillance to ensure the institutional ethical norms are followed during and beyond the study. They may also be involved in setting up and/or reviewing the institutional policies.

For these aspects, IRB (or institutional ethical advisory committee - IEAC) is essential for local governance to enhance best practices. The advantage of an IRB/EEAC is that they understand the institutional conditions and can closely monitor the ongoing research, including any changes in research directions. On the other hand, the IRB may be overly supportive to accept applications, influenced by the local agenda for achieving research excellence, disregarding ethical issues (Kotecha et al., 2011 ; Kayser-Jones, 2003 ) or, they may be influenced by the financial interests in attracting external funding. In this respect, regional and national ethics committees are advantageous to ensure ethical practice. Due to their impartiality, they would provide greater consistency and legitimacy to the research (WHO, 2009 ). However, the ethical approval process of regional and national ethics committees would be time consuming, as they do not have the local knowledge.

As for membership in the IRBs, most of the guidelines [WHO, NICE, Council of Europe, (2012), European Commission - Facilitating Research Excellence in FP7 ( 2013 ) and OHRP] insist on having a variety of representations including experts in different fields of research, and non-experts with the understanding of local, national/international conflicts of interest. The former would be able to understand/clarify the procedural elements of the research in different fields; whilst the latter would help to make neutral and impartial decisions. These non-experts are usually not affiliated to the institution and consist of individuals representing the broader community (particularly those related to social, legal or cultural considerations). IRBs consisting of these varieties of representation would not only be in a position to understand the study procedures and their potential direct or indirect consequences for participants, but also be able to identify any community, cultural or religious implications of the study.

Understanding the subtle differences between ethics and morals

Interestingly, many ethical guidelines are based on society’s moral “beliefs” in such a way that the words “ethics”‘and “morals” are reciprocally used to define each other. However, there are several subtle differences between them and we have attempted to compare and contrast them herein. In the past, many authors have interchangeably used the words “morals”‘and “ethics”‘(Warwick, 2003 ; Kant, 2018 ; Hazard, GC (Jr)., 1994 , Larry, 1982 ). However, ethics is linked to rules governed by an external source such as codes of conduct in workplaces (Kuyare et al., 2014 ). In contrast, morals refer to an individual’s own principles regarding right and wrong. Quinn ( 2011 ) defines morality as “ rules of conduct describing what people ought and ought not to do in various situations … ” while ethics is “... the philosophical study of morality, a rational examination into people’s moral beliefs and behaviours ”. For instance, in a case of parents demanding that schools overturn a ban on use of corporal punishment of children by schools and teachers (Children’s Rights Alliance for England, 2005 ), the parents believed that teachers should assume the role of parent in schools and use corporal or physical punishment for children who misbehaved. This stemmed from their beliefs and what they felt were motivated by “beliefs of individuals or groups”. For example, recent media highlights about some parents opposing LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender) education to their children (BBC News, 2019 ). One parent argued, “Teaching young children about LGBT at a very early stage is ‘morally’ wrong”. She argued “let them learn by themselves as they grow”. This behaviour is linked to and governed by the morals of an ethnic community. Thus, morals are linked to the “beliefs of individuals or group”. However, when it comes to the LGBT rights these are based on ethical principles of that society and governed by law of the land. However, the rights of children to be protected from “inhuman and degrading” treatment is based on the ethical principles of the society and governed by law of the land. Individuals, especially those who are working in medical or judicial professions have to follow an ethical code laid down by their profession, regardless of their own feelings, time or preferences. For instance, a lawyer is expected to follow the professional ethics and represent a defendant, despite the fact that his morals indicate the defendant is guilty.

In fact, we as a group could not find many scholarly articles clearly comparing or contrasting ethics with morals. However, a table presented by Surbhi ( 2015 ) (Difn website c ) tries to differentiate these two terms (see Table 3 ).

Although Table 3 gives some insight on the differences between these two terms, in practice many use these terms as loosely as possible mainly because of their ambiguity. As a group focussed on the application of these principles, we would recommend to use the term “ethics” and avoid “morals” in research and academia.

Based on the literature survey carried out, we were able to identify the following gaps:

there is some disparity in existing literature on the importance of ethical guidelines in research

there is a lack of consensus on what code of conduct should be followed, where it should be derived from and how it should be implemented

The mission of ENAI’s ethical advisory working group

The Ethical Advisory Working Group of ENAI was established in 2018 to promote ethical code of conduct/practice amongst higher educational organisations within Europe and beyond (European Network for Academic Integrity, 2018 ). We aim to provide unbiased advice and consultancy on embedding ethical principles within all types of academic, research and public engagement activities. Our main objective is to promote ethical principles and share good practice in this field. This advisory group aims to standardise ethical norms and to offer strategic support to activities including (but not exclusive to):

● rendering advice and assistance to develop institutional ethical committees and their regulations in member institutions,

● sharing good practice in research and academic ethics,

● acting as a critical guide to institutional review processes, assisting them to maintain/achieve ethical standards,

● collaborating with similar bodies in establishing collegiate partnerships to enhance awareness and practice in this field,

● providing support within and outside ENAI to develop materials to enhance teaching activities in this field,

● organising training for students and early-career researchers about ethical behaviours in form of lectures, seminars, debates and webinars,

● enhancing research and dissemination of the findings in matters and topics related to ethics.

The following sections focus on our suggestions based on collective experiences, review of literature provided in earlier sections and workshop feedback collected:

a) basic needs of an ethical committee within an institution;

b) a typical ethical approval process (with examples from three different universities); and

c) the ways to obtain informed consent with some examples. This would give advice on preparing and training both researchers and research students in appropriately upholding ethical practices through ethical approval processes.

Setting up an institutional ethical committee (ECs)

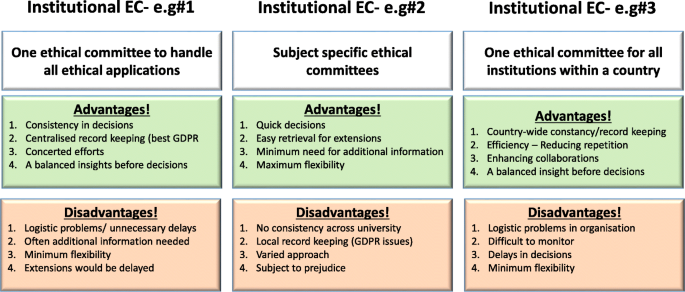

Institutional Ethical Committees (ECs) are essential to govern every aspect of the activities undertaken by that institute. With regards to higher educational organisations, this is vital to establish ethical behaviour for students and staff to impart research, education and scholarly activities (or everything) they do. These committees should be knowledgeable about international laws relating to different fields of studies (such as science, medicine, business, finance, law, and social sciences). The advantages and disadvantages of institutional, subject specific or common (statutory) ECs are summarised in Fig. 2 . Some institutions have developed individual ECs linked to specific fields (or subject areas) whilst others have one institutional committee that overlooks the entire ethical behaviour and approval process. There is no clear preference between the two as both have their own advantages and disadvantages (see Fig. 2 ). Subject specific ECs are attractive to medical, law and business provisions, as it is perceived the members within respective committees would be able to understand the subject and therefore comprehend the need of the proposed research/activity (Kadam, 2012 ; Schnyder et al., 2018 ). However, others argue, due to this “ specificity ”, the committee would fail to forecast the wider implications of that application. On the other hand, university-wide ECs would look into the wider implications. Yet they find it difficult to understand the purpose and the specific applications of that research. Not everyone understands dynamics of all types of research methodologies, data collection, etc., and therefore there might be a chance of a proposal being rejected merely because the EC could not understand the research applications (Getz, 1990 ).

Summary of advantages and disadvantages of three different forms of ethical committees

[N/B for Fig. 2 : Examples of different types of ethical application procedures and forms used were discussed with the workshop attendees to enhance their understanding of the differences. GDPR = General Data Protection Regulation].

Although we recommend a designated EC with relevant professional, academic and ethical expertise to deal with particular types of applications, the membership (of any EC) should include some non-experts who would represent the wider community (see above). Having some non-experts in EC would not only help the researchers to consider explaining their research in layperson’s terms (by thinking outside the box) but also would ensure efficiency without compromising participants/animal safety. They may even help to address the common ethical issues outside research culture. Some UK universities usually offer this membership to a clergy, councillor or a parliamentarian who does not have any links to the institutions. Most importantly, it is vital for any EC members to undertake further training in addition to previous experience in the relevant field of research ethics.

Another issue that raises concerns is multi-centre research, involving several institutions, where institutionalised ethical approvals are needed from each partner. In some cases, such as clinical research within the UK, a common statutory EC called National Health Services (NHS) Research Ethics Committee (NREC) is in place to cover research ethics involving all partner institutions (NHS, 2018 ). The process of obtaining approval from this type of EC takes time, therefore advanced planning is needed.

Ethics approval forms and process

During the workshop, we discussed some anonymised application forms obtained from open-access sources for qualitative and quantitative research as examples. Considering research ethics, for the purpose of understanding, we arbitrarily divided this in two categories; research based on (a) quantitative and (b) qualitative methodologies. As their name suggests their research approach is extremely different from each other. The discussion elicited how ECs devise different types of ethical application form/questions. As for qualitative research, these are often conducted as “face-to-face” interviews, which would have implications on volunteer anonymity.

Furthermore, discussions posited when the interviews are replaced by on-line surveys, they have to be administered through registered university staff to maintain confidentiality. This becomes difficult when the research is a multi-centre study. These types of issues are also common in medical research regarding participants’ anonymity, confidentially, and above all their right to withdraw consent to be involved in research.

Storing and protecting data collected in the process of the study is also a point of consideration when applying for approval.

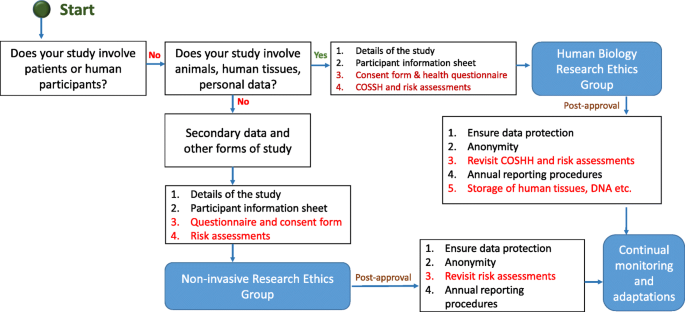

Finally, the ethical processes of invasive (involving human/animals) and non-invasive research (questionnaire based) may slightly differ from one another. Following research areas are considered as investigations that need ethical approval:

research that involves human participants (see below)

use of the ‘products’ of human participants (see below)

work that potentially impacts on humans (see below)

research that involves animals

In addition, it is important to provide a disclaimer even if an ethical approval is deemed unnecessary. Following word cloud (Fig. 3 ) shows the important variables that need to be considered at the brainstorming stage before an ethical application. It is worth noting the importance of proactive planning predicting the “unexpected” during different phases of a research project (such as planning, execution, publication, and future directions). Some applications (such as working with vulnerable individuals or children) will require safety protection clearance (such as DBS - Disclosure and Barring Service, commonly obtained from the local police). Please see section on Research involving Humans - Informed consents for further discussions.

Examples of important variables that need to be considered for an ethical approval

It is also imperative to report or re-apply for ethical approval for any minor or major post-approval changes to original proposals made. In case of methodological changes, evidence of risk assessments for changes and/or COSHH (Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations) should also be given. Likewise, any new collaborative partners or removal of researchers should also be notified to the IEAC.

Other findings include:

in case of complete changes in the project, the research must be stopped and new approval should be seeked,

in case of noticing any adverse effects to project participants (human or non-human), these should also be notified to the committee for appropriate clearance to continue the work, and

the completion of the project must also be notified with the indication whether the researchers may restart the project at a later stage.

Research involving humans - informed consents

While discussing research involving humans and based on literature review, findings highlight the human subjects/volunteers must willingly participate in research after being adequately informed about the project. Therefore, research involving humans and animals takes precedence in obtaining ethical clearance and its strict adherence, one of which is providing a participant information sheet/leaflet. This sheet should contain a full explanation about the research that is being carried out and be given out in lay-person’s terms in writing (Manti and Licari 2018 ; Hardicre 2014 ). Measures should also be in place to explain and clarify any doubts from the participants. In addition, there should be a clear statement on how the participants’ anonymity is protected. We provide below some example questions below to help the researchers to write this participant information sheet:

What is the purpose of the study?

Why have they been chosen?

What will happen if they take part?

What do they have to do?

What happens when the research stops?

What if something goes wrong?

What will happen to the results of the research study?

Will taking part be kept confidential?

How to handle “vulnerable” participants?

How to mitigate risks to participants?

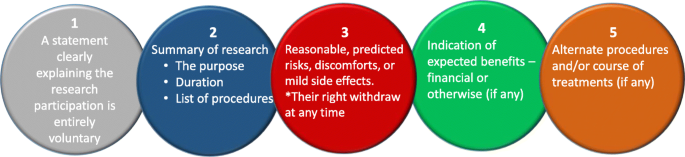

Many institutional ethics committees expect the researchers to produce a FAQ (frequently asked questions) in addition to the information about research. Most importantly, the researchers also need to provide an informed consent form, which should be signed by each human participant. The five elements identified that are needed to be considered for an informed consent statement are summarized in Fig. 4 below (slightly modified from the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects ( 2018 ) - Diffn website c ).

Five basic elements to consider for an informed consent [figure adapted from Diffn website c ]

The informed consent form should always contain a clause for the participant to withdraw their consent at any time. Should this happen all the data from that participant should be eliminated from the study without affecting their anonymity.

Typical research ethics approval process

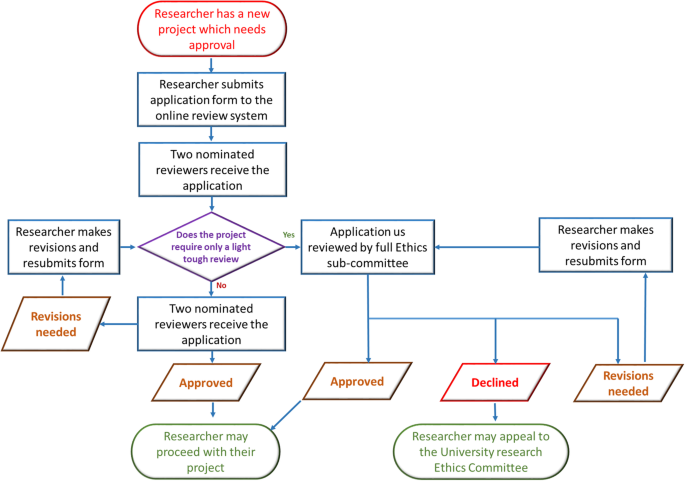

In this section, we provide an example flow chart explaining how researchers may choose the appropriate application and process, as highlighted in Fig. 5 . However, it is imperative to note here that these are examples only and some institutions may have one unified application with separate sections to demarcate qualitative and quantitative research criteria.

Typical ethical approval processes for quantitative and qualitative research. [N/B for Fig. 5 - This simplified flow chart shows that fundamental process for invasive and non-invasive EC application is same, the routes and the requirements for additional information are slightly different]

Once the ethical application is submitted, the EC should ensure a clear approval procedure with distinctly defined timeline. An example flow chart showing the procedure for an ethical approval was obtained from University of Leicester as open-access. This is presented in Fig. 6 . Further examples of the ethical approval process and governance were discussed in the workshop.

An example ethical approval procedures conducted within University of Leicester (Figure obtained from the University of Leicester research pages - Difn website d - open access)

Strategies for ethics educations for students

Student education on the importance of ethics and ethical behaviour in research and scholarly activities is extremely essential. Literature posits in the area of medical research that many universities are incorporating ethics in post-graduate degrees but when it comes to undergraduate degrees, there is less appetite to deliver modules or even lectures focussing on research ethics (Seymour et al., 2004 ; Willison and O’Regan, 2007 ). This may be due to the fact that undergraduate degree structure does not really focus on research (DePasse et al., 2016 ). However, as Orr ( 2018 ) suggested, institutions should focus more on educating all students about ethics/ethical behaviour and their importance in research, than enforcing punitive measures for unethical behaviour. Therefore, as an advisory committee, and based on our preliminary literature survey and workshop results, we strongly recommend incorporating ethical education within undergraduate curriculum. Looking at those institutions which focus on ethical education for both under-and postgraduate courses, their approaches are either (a) a lecture-based delivery, (b) case study based approach or (c) a combined delivery starting with a lecture on basic principles of ethics followed by generating a debate based discussion using interesting case studies. The combined method seems much more effective than the other two as per our findings as explained next.

As many academics who have been involved in teaching ethics and/or research ethics agree, the underlying principles of ethics is often perceived as a boring subject. Therefore, lecture-based delivery may not be suitable. On the other hand, a debate based approach, though attractive and instantly generates student interest, cannot be effective without students understanding the underlying basic principles. In addition, when selecting case studies, it would be advisable to choose cases addressing all different types of ethical dilemmas. As an advisory group within ENAI, we are in the process of collating supporting materials to help to develop institutional policies, creating advisory documents to help in obtaining ethical approvals, and teaching materials to enhance debate-based lesson plans that can be used by the member and other institutions.

Concluding remarks

In summary, our literature survey and workshop findings highlight that researchers should accept that ethics underpins everything we do, especially in research. Although ethical approval is tedious, it is an imperative process in which proactive thinking is essential to identify ethical issues that might affect the project. Our findings further lead us to state that the ethical approval process differs from institution to institution and we strongly recommend the researchers to follow the institutional guidelines and their underlying ethical principles. The ENAI workshop in Vilnius highlighted the importance of ethical governance by establishing ECs, discussed different types of ECs and procedures with some examples and highlighted the importance of student education to impart ethical culture within research communities, an area that needs further study as future scope.

Declarations

The manuscript was entirely written by the corresponding author with contributions from co-authors who have also taken part in the delivery of the workshop. Authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. We can also confirm that there are no potential competing interests with other organisations.

Availability of data and materials

Authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

ALL European academics

Australian research council

Biotechnology and biological sciences research council

Canadian institutes for health research

Committee of publication ethics

Ethical committee

European network of academic integrity

Economic and social research council

International convention for the protection of animals

institutional ethical advisory committee

Institutional review board

Immaculata university of Pennsylvania

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

Medical research council)

National health services

National health services nih national institute of health (NIH)

National institute of clinical care excellence

National health and medical research council

Natural sciences and engineering research council

National research ethics committee

National statement on ethical conduct in human research

Responsible research practice

Social sciences and humanities research council

Tri-council policy statement

World Organization for animal health

Universities Australia

UK-research and innovation

US office for human research protections

Alba S, Lenglet A, Verdonck K, Roth J, Patil R, Mendoza W, Juvekar S, Rumisha SF (2020) Bridging research integrity and global health epidemiology (BRIDGE) guidelines: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Glob Health 5(10):e003237. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003237

Article Google Scholar

Anderson MS (2011) Research misconduct and misbehaviour. In: Bertram Gallant T (ed) Creating the ethical academy: a systems approach to understanding misconduct and empowering change in higher education. Routledge, pp 83–96

BBC News. (2019). Birmingham school LGBT LESSONS PROTEST investigated. March 8, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2021, available online. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-47498446

Children’s Rights Alliance for England. (2005). R (Williamson and others) v Secretary of State for Education and Employment. Session 2004–05. [2005] UKHL 15. Available Online. URL: http://www.crae.org.uk/media/33624/R-Williamson-and-others-v-Secretary-of-State-for-Education-and-Employment.pdf

Council of Europe. (2014). Texts of the Council of Europe on bioethical matters. Available Online. https://www.coe.int/t/dg3/healthbioethic/Texts_and_documents/INF_2014_5_vol_II_textes_%20CoE_%20bio%C3%A9thique_E%20(2).pdf

Dellaportas S, Kanapathippillai S, Khan, A and Leung, P. (2014). Ethics education in the Australian accounting curriculum: a longitudinal study examining barriers and enablers. 362–382. Available Online. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2014.930694 , 23, 4, 362, 382

DePasse JM, Palumbo MA, Eberson CP, Daniels AH (2016) Academic characteristics of orthopaedic surgery residency applicants from 2007 to 2014. JBJS 98(9):788–795. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.15.00222

Desmond H, Dierickx K (2021) Research integrity codes of conduct in Europe: understanding the divergences. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12851

Difn website a - National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (NSECHR). (2018). Available Online. URL: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-code-responsible-conduct-research-2018

Difn website b - Enago academy Importance of Ethics Committees in Scholarly Research (2020, October 26). Available online. URL: https://www.enago.com/academy/importance-of-ethics-committees-in-scholarly-research/

Difn website c - Ethics vs Morals - Difference and Comparison. Retrieved July 14, 2020. Available online. URL: https://www.diffen.com/difference/Ethics_vs_Morals

Difn website d - University of Leicester. (2015). Staff ethics approval flowchart. May 1, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2020. Available Online. URL: https://www2.le.ac.uk/institution/ethics/images/ethics-approval-flowchart/view

European Commission - Facilitating Research Excellence in FP7 (2013) https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/fp7/89888/ethics-for-researchers_en.pdf

European Network for Academic Integrity. (2018). Ethical advisory group. Retrieved February 14, 2021. Available online. URL: http://www.academicintegrity.eu/wp/wg-ethical/

Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. (2018). Retrieved February 14, 2021. Available Online. URL: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/19/2017-01058/federal-policy-for-the-protection-of-human-subjects#p-855

Flite, CA and Harman, LB. (2013). Code of ethics: principles for ethical leadership Perspect Health Inf Mana; 10(winter): 1d. PMID: 23346028

Fouka G, Mantzorou M (2011) What are the major ethical issues in conducting research? Is there a conflict between the research ethics and the nature of nursing. Health Sci J 5(1) Available Online. URL: https://www.hsj.gr/medicine/what-are-the-major-ethical-issues-in-conducting-research-is-there-a-conflict-between-the-research-ethics-and-the-nature-of-nursing.php?aid=3485

Fox G (2017) History and ethical principles. The University of Miami and the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) Program URL https://silo.tips/download/chapter-1-history-and-ethical-principles # (Available Online)

Getz KA (1990) International codes of conduct: An analysis of ethical reasoning. J Bus Ethics 9(7):567–577

Ghooi RB (2011) The nuremberg code–a critique. Perspect Clin Res 2(2):72–76. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.80371

Hardicre, J. (2014) Valid informed consent in research: an introduction Br J Nurs 23(11). https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.11.564 , 567

Hazard, GC (Jr). (1994). Law, morals, and ethics. Yale law school legal scholarship repository. Faculty Scholarship Series. Yale University. Available Online. URL: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=3322&context=fss_papers

Israel, M., & Drenth, P. (2016). Research integrity: perspectives from Australia and Netherlands. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (pp. 789–808). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_64

Kadam R (2012) Proactive role for ethics committees. Indian J Med Ethics 9(3):216. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2012.072

Kant I (2018) The metaphysics of morals. Cambridge University Press, UK https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316091388

Kayser-Jones J (2003) Continuing to conduct research in nursing homes despite controversial findings: reflections by a research scientist. Qual Health Res 13(1):114–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302239414

Kotecha JA, Manca D, Lambert-Lanning A, Keshavjee K, Drummond N, Godwin M, Greiver M, Putnam W, Lussier M-T, Birtwhistle R (2011) Ethics and privacy issues of a practice-based surveillance system: need for a national-level institutional research ethics board and consent standards. Can Fam physician 57(10):1165–1173. https://europepmc.org/article/pmc/pmc3192088

Kuyare, MS., Taur, SR., Thatte, U. (2014). Establishing institutional ethics committees: challenges and solutions–a review of the literature. Indian J Med Ethics. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2014.047

LaFollette, H. (2007). Ethics in practice (3rd edition). Blackwell

Larry RC (1982) The teaching of ethics and moral values in teaching. J High Educ 53(3):296–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1982.11780455

Manti S, Licari A (2018) How to obtain informed consent for research. Breathe (Sheff) 14(2):145–152. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.001918

Mulholland MW, Bell J (2005) Research Governance and Research Funding in the USA: What the academic surgeon needs to know. J R Soc Med 98(11):496–502. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.98.11.496

National Institute of Health (NIH) Ethics in Clinical Research. n.d. Available Online. URL: https://clinicalcenter.nih.gov/recruit/ethics.html

NHS (2018) Flagged Research Ethics Committees. Retrieved February 14, 2021. Available online. URL: https://www.hra.nhs.uk/about-us/committees-and-services/res-and-recs/flagged-research-ethics-committees/

NICE (2018) Research governance policy. Retrieved February 14, 2021. Available online. URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/science-policy-and-research/research-governance-policy.pdf

Orr, J. (2018). Developing a campus academic integrity education seminar. J Acad Ethics 16(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-018-9304-7

Quinn, M. (2011). Introduction to Ethics. Ethics for an Information Age. 4th Ed. Ch 2. 53–108. Pearson. UK

Resnik. (2020). What is ethics in Research & why is it Important? Available Online. URL: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/bioethics/whatis/index.cfm

Schnyder S, Starring H, Fury M, Mora A, Leonardi C, Dasa V (2018) The formation of a medical student research committee and its impact on involvement in departmental research. Med Educ Online 23(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2018.1424449

Seymour E, Hunter AB, Laursen SL, DeAntoni T (2004) Establishing the benefits of research experiences for undergraduates in the sciences: first findings from a three-year study. Sci Educ 88(4):493–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10131

Shamoo AE, Irving DN (1993) Accountability in research using persons with mental illness. Account Res 3(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989629308573826

Shaw, S., Boynton, PM., and Greenhalgh, T. (2005). Research governance: where did it come from, what does it mean? Research governance framework for health and social care, 2nd ed. London: Department of Health. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.98.11.496 , 98, 11, 496, 502

Book Google Scholar

Speight, JG. (2016) Ethics in the university |DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119346449 scrivener publishing LLC

Stephenson GK, Jones GA, Fick E, Begin-Caouette O, Taiyeb A, Metcalfe A (2020) What’s the protocol? Canadian university research ethics boards and variations in implementing tri-Council policy. Can J Higher Educ 50(1)1): 68–81

Surbhi, S. (2015). Difference between morals and ethics [weblog]. March 25, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2021. Available Online. URL: http://keydifferences.com/difference-between-morals-and-ethics.html