Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

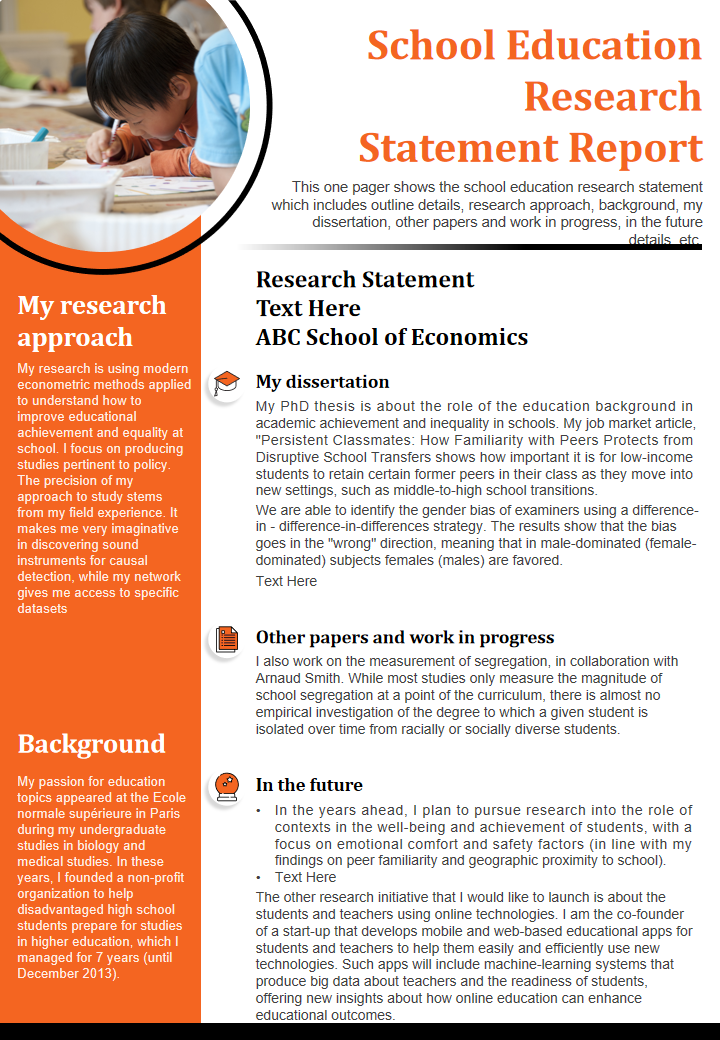

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

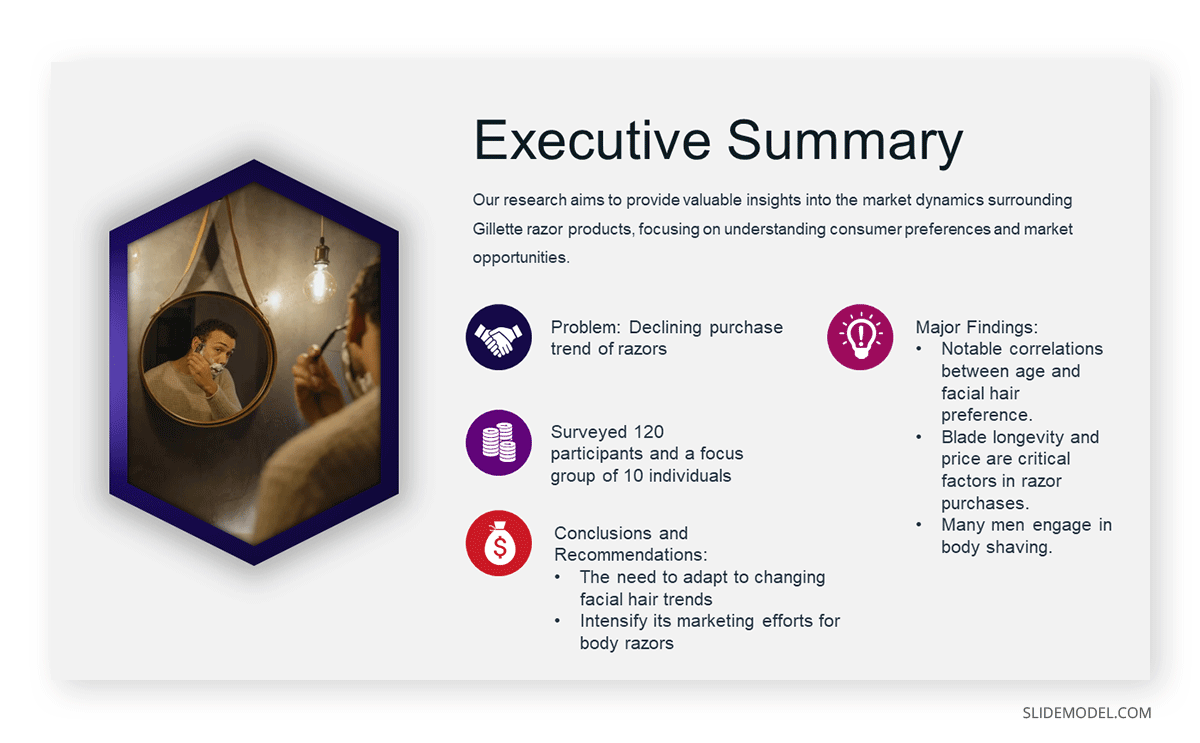

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

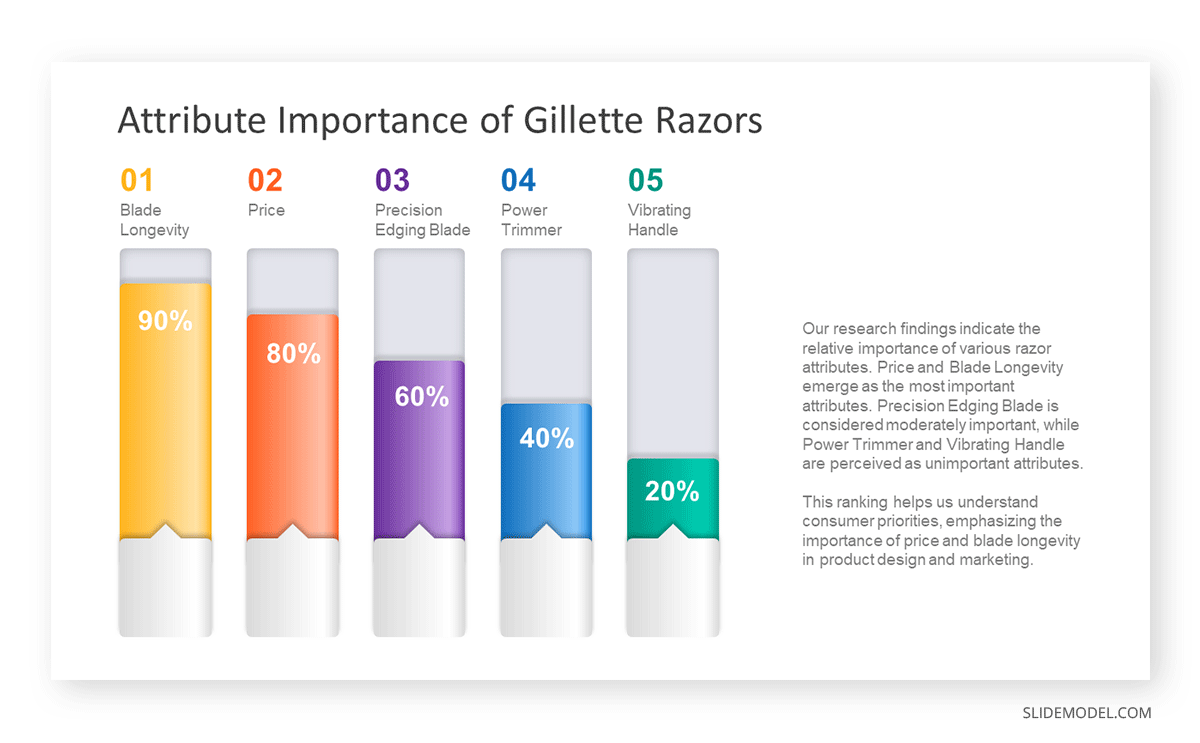

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

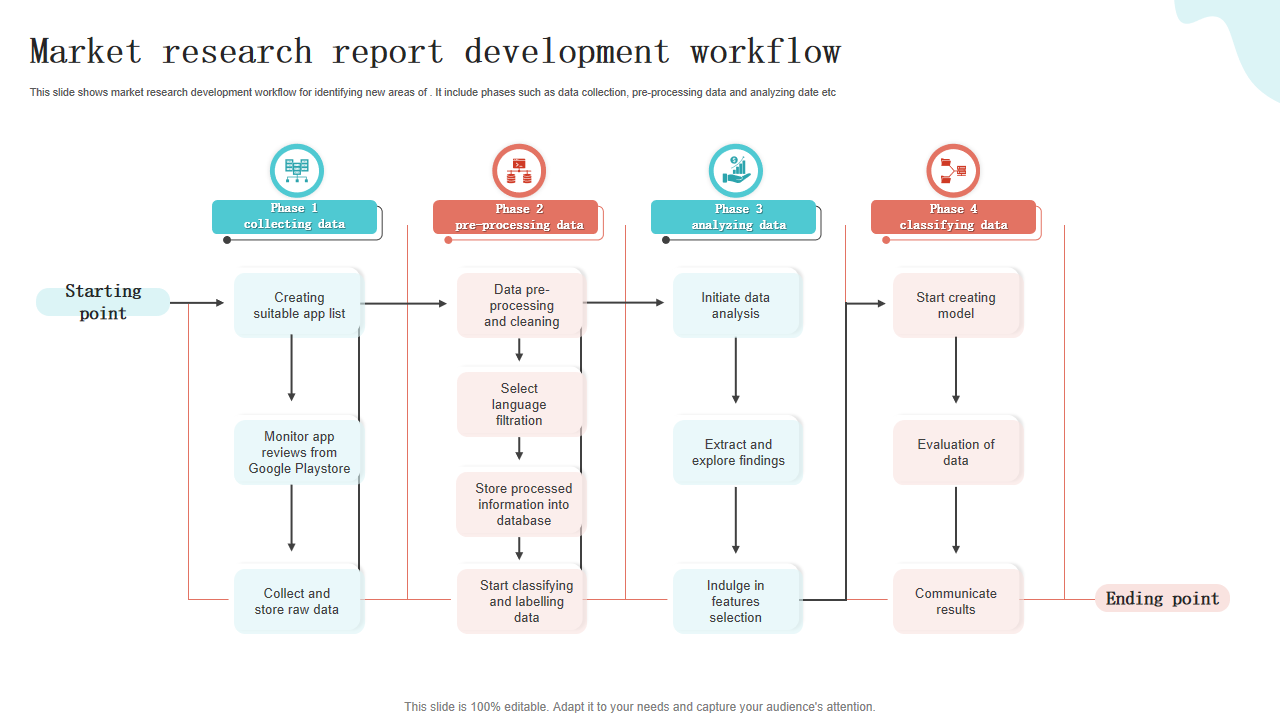

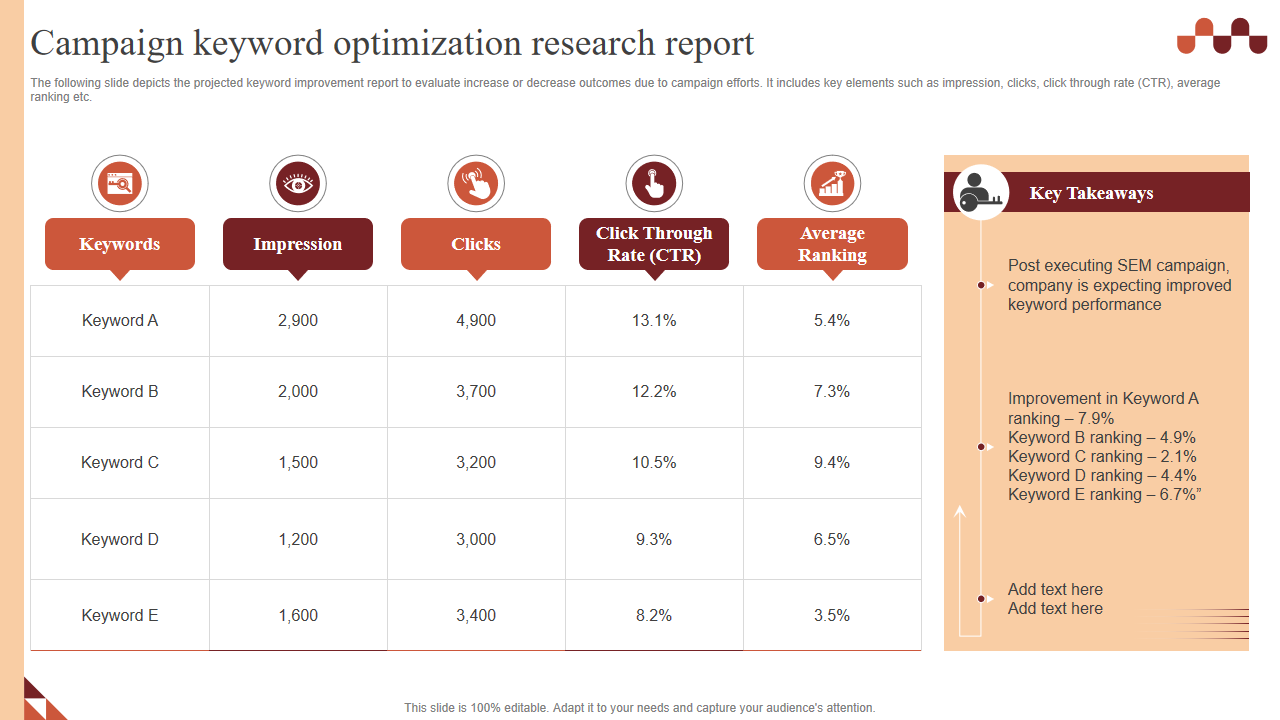

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation.

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

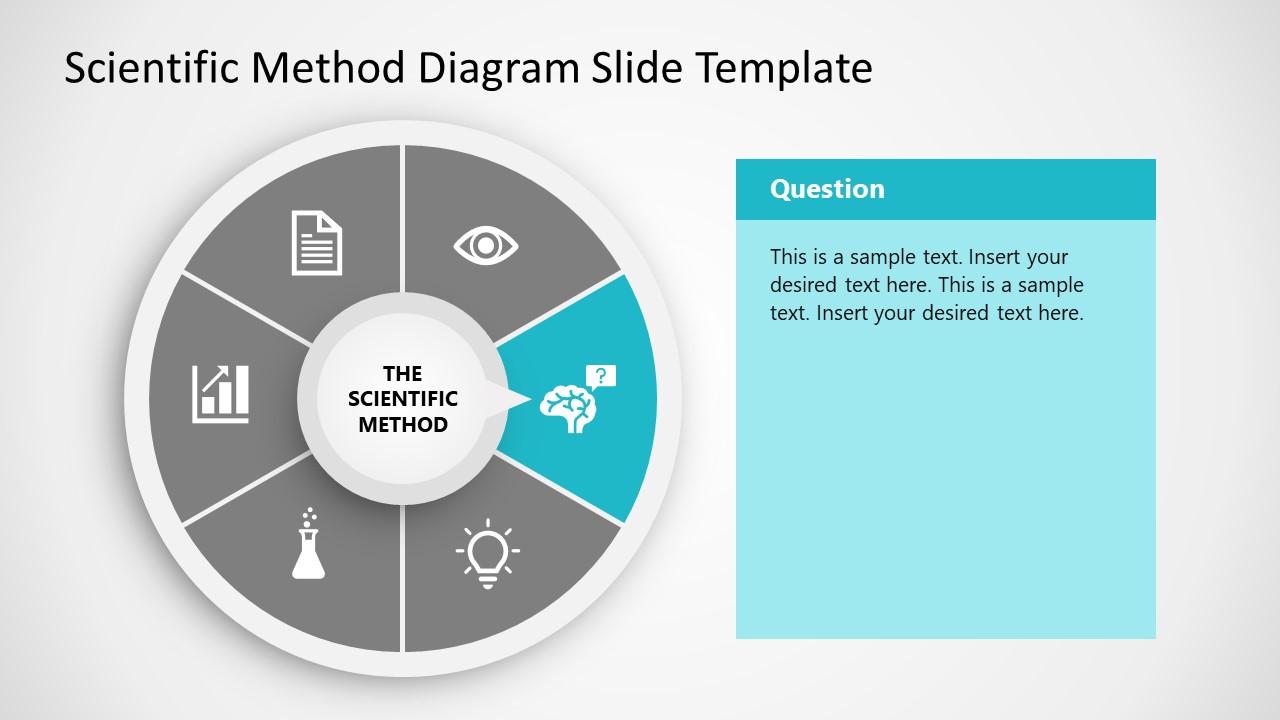

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

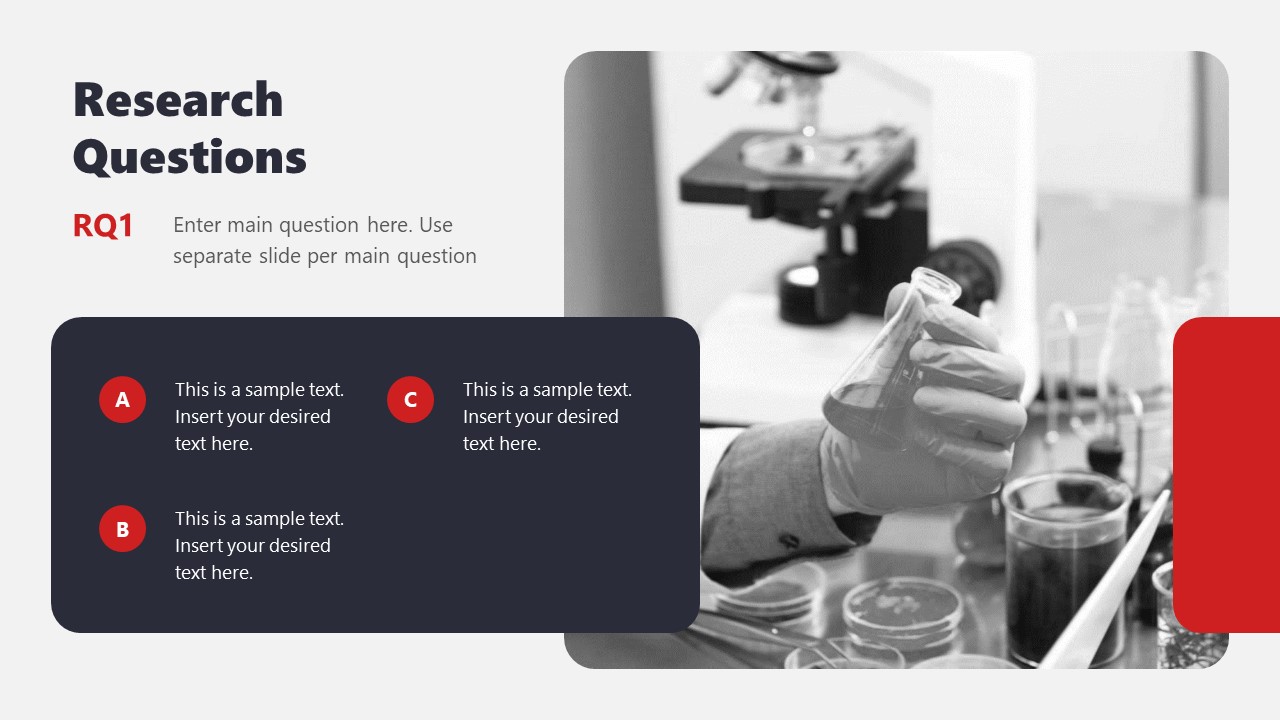

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Design • May 22nd, 2024

Exploring the 12 Different Types of Slides in PowerPoint

Become a better presenter by harnessing the power of the 12 different types of slides in presentation design.

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Filed under Presentation Ideas • February 29th, 2024

How to Make a Fundraising Presentation (with Thermometer Templates & Slides)

Meet a new framework to design fundraising presentations by harnessing the power of fundraising thermometer templates. Detailed guide with examples.

Leave a Reply

- Google Slides Presentation Design

- Pitch Deck Design

- Powerpoint Redesign

- Other Design Services

- Guide & How to's

How to present a research paper in PPT: best practices

A research paper presentation is frequently used at conferences and other events where you have a chance to share the results of your research and receive feedback from colleagues. Although it may appear as simple as summarizing the findings, successful examples of research paper presentations show that there is a little bit more to it.

In this article, we’ll walk you through the basic outline and steps to create a good research paper presentation. We’ll also explain what to include and what not to include in your presentation of research paper and share some of the most effective tips you can use to take your slides to the next level.

Research paper PowerPoint presentation outline

Creating a PowerPoint presentation for a research paper involves organizing and summarizing your key findings, methodology, and conclusions in a way that encourages your audience to interact with your work and share their interest in it with others. Here’s a basic research paper outline PowerPoint you can follow:

1. Title (1 slide)

Typically, your title slide should contain the following information:

- Title of the research paper

- Affiliation or institution

- Date of presentation

2. Introduction (1-3 slides)

On this slide of your presentation, briefly introduce the research topic and its significance and state the research question or objective.

3. Research questions or hypothesis (1 slide)

This slide should emphasize the objectives of your research or present the hypothesis.

4. Literature review (1 slide)

Your literature review has to provide context for your research by summarizing relevant literature. Additionally, it should highlight gaps or areas where your research contributes.

5. Methodology and data collection (1-2 slides)

This slide of your research paper PowerPoint has to explain the research design, methods, and procedures. It must also Include details about participants, materials, and data collection and emphasize special equipment you have used in your work.

6. Results (3-5 slides)

On this slide, you must present the results of your data analysis and discuss any trends, patterns, or significant findings. Moreover, you should use charts, graphs, and tables to illustrate data and highlight something novel in your results (if applicable).

7. Conclusion (1 slide)

Your conclusion slide has to summarize the main findings and their implications, as well as discuss the broader impact of your research. Usually, a single statement is enough.

8. Recommendations (1 slide)

If applicable, provide recommendations for future research or actions on this slide.

9. References (1-2 slides)

The references slide is where you list all the sources cited in your research paper.

10. Acknowledgments (1 slide)

On this presentation slide, acknowledge any individuals, organizations, or funding sources that contributed to your research.

11. Appendix (1 slide)

If applicable, include any supplementary materials, such as additional data or detailed charts, in your appendix slide.

The above outline is just a general guideline, so make sure to adjust it based on your specific research paper and the time allotted for the presentation.

Steps to creating a memorable research paper presentation

Creating a PowerPoint presentation for a research paper involves several critical steps needed to convey your findings and engage your audience effectively, and these steps are as follows:

Step 1. Understand your audience:

- Identify the audience for your presentation.

- Tailor your content and level of detail to match the audience’s background and knowledge.

Step 2. Define your key messages:

- Clearly articulate the main messages or findings of your research.

- Identify the key points you want your audience to remember.

Step 3. Design your research paper PPT presentation:

- Use a clean and professional design that complements your research topic.

- Choose readable fonts, consistent formatting, and a limited color palette.

- Opt for PowerPoint presentation services if slide design is not your strong side.

Step 4. Put content on slides:

- Follow the outline above to structure your presentation effectively; include key sections and topics.

- Organize your content logically, following the flow of your research paper.

Step 5. Final check:

- Proofread your slides for typos, errors, and inconsistencies.

- Ensure all visuals are clear, high-quality, and properly labeled.

Step 6. Save and share:

- Save your presentation and ensure compatibility with the equipment you’ll be using.

- If necessary, share a copy of your presentation with the audience.

By following these steps, you can create a well-organized and visually appealing research paper presentation PowerPoint that effectively conveys your research findings to the audience.

What to include and what not to include in your presentation

In addition to the must-know PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, consider the following do’s and don’ts when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Focus on the topic.

- Be brief and to the point.

- Attract the audience’s attention and highlight interesting details.

- Use only relevant visuals (maps, charts, pictures, graphs, etc.).

- Use numbers and bullet points to structure the content.

- Make clear statements regarding the essence and results of your research.

Don’ts:

- Don’t write down the whole outline of your paper and nothing else.

- Don’t put long, full sentences on your slides; split them into smaller ones.

- Don’t use distracting patterns, colors, pictures, and other visuals on your slides; the simpler, the better.

- Don’t use too complicated graphs or charts; only the ones that are easy to understand.

- Now that we’ve discussed the basics, let’s move on to the top tips for making a powerful presentation of your research paper.

8 tips on how to make research paper presentation that achieves its goals

You’ve probably been to a presentation where the presenter reads word for word from their PowerPoint outline. Or where the presentation is cluttered, chaotic, or contains too much data. The simple tips below will help you summarize a 10 to 15-page paper for a 15 to 20-minute talk and succeed, so read on!

Tip #1: Less is more

You want to provide enough information to make your audience want to know more. Including details but not too many and avoiding technical jargon, formulas, and long sentences are always good ways to achieve this.

Tip #2: Be professional

Avoid using too many colors, font changes, distracting backgrounds, animations, etc. Bullet points with a few words to highlight the important information are preferable to lengthy paragraphs. Additionally, include slide numbers on all PowerPoint slides except for the title slide, and make sure it is followed by a table of contents, offering a brief overview of the entire research paper.

Tip #3: Strive for balance

PowerPoint slides have limited space, so use it carefully. Typically, one to two points per slide or 5 lines for 5 words in a sentence are enough to present your ideas.

Tip #4: Use proper fonts and text size

The font you use should be easy to read and consistent throughout the slides. You can go with Arial, Times New Roman, Calibri, or a combination of these three. An ideal text size is 32 points, while a heading size is 44.

Tip #5: Concentrate on the visual side

A PowerPoint presentation is one of the best tools for presenting information visually. Use graphs instead of tables and topic-relevant illustrations instead of walls of text. Keep your visuals as clean and professional as the content of your presentation.

Tip #6: Practice your delivery

Always go through your presentation when you’re done to ensure a smooth and confident delivery and time yourself to stay within the allotted limit.

Tip #7: Get ready for questions

Anticipate potential questions from your audience and prepare thoughtful responses. Also, be ready to engage in discussions about your research.

Tip #8: Don’t be afraid to utilize professional help

If the mere thought of designing a presentation overwhelms you or you’re pressed for time, consider leveraging professional PowerPoint redesign services . A dedicated design team can transform your content or old presentation into effective slides, ensuring your message is communicated clearly and captivates your audience. This way, you can focus on refining your delivery and preparing for the presentation.

Lastly, remember that even experienced presenters get nervous before delivering research paper PowerPoint presentations in front of the audience. You cannot know everything; some things can be beyond your control, which is completely fine. You are at the event not only to share what you know but also to learn from others. So, no matter what, dress appropriately, look straight into the audience’s eyes, try to speak and move naturally, present your information enthusiastically, and have fun!

If you need help with slide design, get in touch with our dedicated design team and let qualified professionals turn your research findings into a visually appealing, polished presentation that leaves a lasting impression on your audience. Our experienced designers specialize in creating engaging layouts, incorporating compelling graphics, and ensuring a cohesive visual narrative that complements content on any subject.

- Presenting techniques

- 50 tips on how to improve PowerPoint presentations in 2022-2023 [Updated]

- Keynote VS PowerPoint

- Types of presentations

- Present financial information visually in PowerPoint to drive results

- Publication Recognition

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

- 4 minute read

- 128.2K views

Table of Contents

A research paper presentation is often used at conferences and in other settings where you have an opportunity to share your research, and get feedback from your colleagues. Although it may seem as simple as summarizing your research and sharing your knowledge, successful research paper PowerPoint presentation examples show us that there’s a little bit more than that involved.

In this article, we’ll highlight how to make a PowerPoint presentation from a research paper, and what to include (as well as what NOT to include). We’ll also touch on how to present a research paper at a conference.

Purpose of a Research Paper Presentation

The purpose of presenting your paper at a conference or forum is different from the purpose of conducting your research and writing up your paper. In this setting, you want to highlight your work instead of including every detail of your research. Likewise, a presentation is an excellent opportunity to get direct feedback from your colleagues in the field. But, perhaps the main reason for presenting your research is to spark interest in your work, and entice the audience to read your research paper.

So, yes, your presentation should summarize your work, but it needs to do so in a way that encourages your audience to seek out your work, and share their interest in your work with others. It’s not enough just to present your research dryly, to get information out there. More important is to encourage engagement with you, your research, and your work.

Tips for Creating Your Research Paper Presentation

In addition to basic PowerPoint presentation recommendations, which we’ll cover later in this article, think about the following when you’re putting together your research paper presentation:

- Know your audience : First and foremost, who are you presenting to? Students? Experts in your field? Potential funders? Non-experts? The truth is that your audience will probably have a bit of a mix of all of the above. So, make sure you keep that in mind as you prepare your presentation.

Know more about: Discover the Target Audience .

- Your audience is human : In other words, they may be tired, they might be wondering why they’re there, and they will, at some point, be tuning out. So, take steps to help them stay interested in your presentation. You can do that by utilizing effective visuals, summarize your conclusions early, and keep your research easy to understand.

- Running outline : It’s not IF your audience will drift off, or get lost…it’s WHEN. Keep a running outline, either within the presentation or via a handout. Use visual and verbal clues to highlight where you are in the presentation.

- Where does your research fit in? You should know of work related to your research, but you don’t have to cite every example. In addition, keep references in your presentation to the end, or in the handout. Your audience is there to hear about your work.

- Plan B : Anticipate possible questions for your presentation, and prepare slides that answer those specific questions in more detail, but have them at the END of your presentation. You can then jump to them, IF needed.

What Makes a PowerPoint Presentation Effective?

You’ve probably attended a presentation where the presenter reads off of their PowerPoint outline, word for word. Or where the presentation is busy, disorganized, or includes too much information. Here are some simple tips for creating an effective PowerPoint Presentation.

- Less is more: You want to give enough information to make your audience want to read your paper. So include details, but not too many, and avoid too many formulas and technical jargon.

- Clean and professional : Avoid excessive colors, distracting backgrounds, font changes, animations, and too many words. Instead of whole paragraphs, bullet points with just a few words to summarize and highlight are best.

- Know your real-estate : Each slide has a limited amount of space. Use it wisely. Typically one, no more than two points per slide. Balance each slide visually. Utilize illustrations when needed; not extraneously.

- Keep things visual : Remember, a PowerPoint presentation is a powerful tool to present things visually. Use visual graphs over tables and scientific illustrations over long text. Keep your visuals clean and professional, just like any text you include in your presentation.

Know more about our Scientific Illustrations Services .

Another key to an effective presentation is to practice, practice, and then practice some more. When you’re done with your PowerPoint, go through it with friends and colleagues to see if you need to add (or delete excessive) information. Double and triple check for typos and errors. Know the presentation inside and out, so when you’re in front of your audience, you’ll feel confident and comfortable.

How to Present a Research Paper

If your PowerPoint presentation is solid, and you’ve practiced your presentation, that’s half the battle. Follow the basic advice to keep your audience engaged and interested by making eye contact, encouraging questions, and presenting your information with enthusiasm.

We encourage you to read our articles on how to present a scientific journal article and tips on giving good scientific presentations .

Language Editing Plus

Improve the flow and writing of your research paper with Language Editing Plus. This service includes unlimited editing, manuscript formatting for the journal of your choice, reference check and even a customized cover letter. Learn more here , and get started today!

- Manuscript Preparation

Know How to Structure Your PhD Thesis

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

You may also like.

What is a Good H-index?

What is a Corresponding Author?

How to Submit a Paper for Publication in a Journal

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Writing a Research Report

Aug 06, 2014

770 likes | 1.65k Views

Writing a Research Report. If research was not “written up,” did it really occur?. Writing a Research Report. Academic sociologists conduct research to discover facts, truths, and explanations about the social world. They write research reports to convey theirs and others’ research findings.

Share Presentation

- newer persons

- specific topic

- qualitative research reports

- establish expectations

- complete information

Presentation Transcript

Writing a Research Report If research was not “written up,” did it really occur?

Writing a Research Report • Academic sociologists conduct research to discover facts, truths, and explanations about the social world. • They write research reports to convey theirs and others’ research findings. • Types of Research: Library research refers to gathering information that others have generated. Primary research refers to generating information through data collection, analysis, and reporting findings.

Writing a Research Report • Sociologists’ articles, papers, or research reports come in different forms: • Literature Review: Library research that organizes facts and/or theories others in the sociological community generated (Rarely published) • Research Article or Book: One’s own findings generated by a primary research project that builds on previous research by the sociological community. (Findings from basic research, most common.) • Applied Research Report: One’s findings from a primary research project that evaluates a program without drawing much from previous sociological research. (Findings from applied research, rarely published.) • This class focuses on writing Research Articles.

Writing a Research Report • A sociological article, paper, or report generally covers only one important topic of interest and conveys evidence and interpretations of evidence. • Research reports are NOT creative writing, opinion pieces, poems, novels, letters, musings, memoirs, or interesting to read.

Writing a Research Report • A sociological article, paper, or report about primary research generally takes a structure or form that seems difficult but is intended to help make reading it or using it for research quick and efficient. • A research report has seven components: • Abstract or Summary • Introduction • Review of Literature • Methods • Results • Conclusions and Discussion • References • Note: • Qualitative research reports will vary from what is presented here. • Applied research reports may vary from what is presented here.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Abstract or Summary The abstract or summary tells the reader very briefly what the main points and findings of the paper are. • This allows the reader to decide whether the paper is useful to them. • Get into the habit of reading only abstracts while searching for papers that are relevant to your research. • Read the body of a paper only when you think it will be useful to you.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • 1. Abstract or Summary—an example

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Introduction • The introduction tells the reader: • what the topic of the paper is in general terms, • why the topic is important • what to expect in the paper. • Introductions should: • funnel from general ideas to the specific topic of the paper • justify the research that will be presented later • Introductions are sometimes folded into literature reviews

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • 2. Introduction—an example

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature The literature review tells the reader what other researchers have discovered about the paper’s topic or tells the reader about other research that is relevant to the topic. Often what students call a “research paper” is merely a literature review. • A literature review should shape the way readers think about a topic—it educates readers about what the community of scholars says about a topic and its surrounding issues. • Along the way it states facts and ideas about the social world and supports those facts and ideas with evidence for from where they came (empiricism).

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • Literature reviews have parenthetical citations running throughout. These are part of a systematic way to document where facts and ideas came from, allowing the skeptical reader to look up anything that is questionable. • Parenthetical citation is our way of substantiating the claims in our paper, without breaking our flow. • Each citation directs the reader to the references where complete details on sources can be found. Therefore, information such as authors’ first names or titles of works do not need to be written into the text.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • Citations consist of authors’ last names and the year of publication. One finds complete information on sources by looking up last names and dates in alphabetized references—so there’s no need to put all that information in the text. • We have conventions that allow the reader to figure out from where information is coming . Here are some examples of the conventions for citing in text of the literature review: Just pointing out where info came from: • Form: blah blah (Author Year) • Example: … the gays are different (Lee 2004). • More than one article in the same year: • Form: blah blah (Author Yeara) and also blah blah (Author yearb) • Example: …are different (Lee 2004a), but are more pickled (Lee 2004b)

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • We have conventions that allow the reader to figure out from where information is coming . Here are some examples of the conventions for citing in text of the literature review: Where a researcher is quoted: • Form: blah, “Quote quote” (Author Year: Pages) • Example: reveals that “the gays are different.” (Lee 2004: 340). More than one source: • Form: blah blah (Author Year; Author Year) • Example: …bi’s are more adept (Lee 2004; Seymour & Hewitt 1997).

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • We have conventions that allow the reader to figure out from where information is coming . Here are some examples of the conventions for citing in text of the literature review: Using the author’s name in a sentence: • Form: Author (Year) says that… • Example: Lee (2004) claims that girls will rule the world… Quoting a person and using their name: • Form: Author (Year: Pages) says, “Quote quote…” • Example: Lee (2004: 341) says, “Girls are more likely to rule the world…”

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • 3. Review of Literature—examples of citing

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • If an idea is used, but cannot be substantiated by the community of sociologists, the literature review clearly shows that the author is speculating and details the logic of the speculation. • Do NOT discuss irrelevant information. • For example, a paper on attitudes about marijuana attitudes should not detail the multiple uses of hemp such as in clothing, rope, hemp oil and so forth. • The literature review has is written in the author’s voice. The sources of information are not extensively quoted or “copied and pasted.” Instead, the author puts facts and ideas into his or her own words while pointing out from where the information came. • Analogously, if you were discussing the exciting things you learned in a sociology course at a cocktail party, you would use your own words. You would NOT pull out a book or lecture notes and quote these word for word.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • Note: Explaining why social events occur as they do requires use (and testing) of explanations that have worked before. THESE EXPLANATIONS ARE CALLED THEORIES. • Most academic literature reviews have a guiding theory that is used to: • Frame (or help us understand) facts in the literature. • Establish expectations (or hypotheses) for the research. • Justify speculation when no evidence to justify an idea specific to a topic exists in the literature. • Sometimes the whole point of a research project is to: • Determine whether a theory works • Pit two or more theories against each other to see which works better • You will most likely not refer to theories in your papers

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Review of Literature • Quantitative literature reviews typically end with: • Focused declarations of the particular issues the research activity is addressing—ideas about a topic that will be tested with quantitative methods • Research hypotheses Hypotheses are statements of the expected relationship(s) between two (or more) variables For example: “Men will have higher investment income than women.” “Older Americans are more likely to oppose abortion for a woman who doesn’t want her baby because she is poor.”

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • 3. Review of Literature—examples of hypotheses Hypothesis 1. In a new social context, girls will be more sociable than boys—getting more involved with others (interactional commitments) and forming more emotionally close relationships (affective commitments)—across activity domains. Hypothesis 2. Given that commitments to new relationships positively determine identity prominence, and identity prominence positively determines behaviors, if girls are more sociable with newer persons, their identities and behaviors will change more across activity domains. Hypothesis 3. However, girls and boys will experience the same identity processes, meaning that girls and boys with the same sociability in new relationships will have equal identity and behavior changes.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Methods A METHODS SECTION MUST CONTAIN: • Descriptions of Data (Think in terms of: “Who, What, When, Where, Why and How?”) Report: • The Target Population • The Ways Data were Collected: • Sampling • Delivery Methods • Response Rates • Sample sizes resulting from various decisions Such as: • eliminating non-Christians from the sample • using only white respondents

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Methods A METHODS SECTION MUST CONTAIN: • Descriptions of Variables First for dependent, then for independent variables, report: • Names for the variables—make them intuitive! (Do not use GSS variable names.) • Word for word description of the questions. (sociology differs from psychology and medicine) • Final coding scheme—the numbers you assigned to responses.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Methods A METHODS SECTION MUST CONTAIN: • Manipulations of the variables or data For example: • recoding income from 23 uneven intervals to five equivalent categories • removing non-citizens if studying voting patterns • Reflection on ability of data to generalize to the target population • Limitations of Data (omitted cases, biases, etc.) • Analyses that bolster claims that the data are appropriate • Statistical techniques that will be used to test your hypotheses and the statistics program used.

Writing a Research Report 4. Methods

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Results The results section chronicles the outcome of the statistical analyses, assessing whether your hypotheses were correct and why or why not.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Results The results section includes: • Narrative describing most relevant findings • Professional tables showing descriptive and inferential statistics • Tables must be numbered and have a descriptive title • There are conventions for formatting For example: • Asterisks are used to highlight results that are statistically important • All numbers in a column are aligned on decimals

Writing a Research Report 5. Results

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Results The narrative and tables are complementary. • The narrative discusses ONLY VERY IMPORTANT Results and leaves details for tables. • As different outcomes are described in the narrative, reference is made to where the detailed information can be found in the tables. • The tables contain almost all statistical information so that the author does not have to write a narrative for every detail in the analysis.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Results The narrative highlights: • Evaluations of the hypotheses. Were the research hypotheses supported? • Statements about new discoveries or surprises encountered in the analyses

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Conclusions and Discussion This section assesses how one’s research findings relate to what the community of sociologists have accepted as facts. Things that should be done: • Summarize the most salient points of your research (tell the reader what you found out about your topic). • Discuss the general significance of your topic and findings.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • Conclusions and Discussion • Discuss the shortcomings of your study and how these might affect your findings. • Discuss things future researchers should investigate about your topic to advance knowledge about it. • Help the reader gain the knowledge that you think he or she ought to have about the topic. You spent a lot of time exploring the, you should share your expertise.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • References The references are just as important as any other part of your paper. References are the empirical support for claims in a paper that are not directly observed in the research. They are needed for researchers to remain empirical in their descriptions of topics.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • References: Link the paper to the community of scholars, permitting readers to assess the worthiness claims in a paper. Make the research process much more efficient because they make it very easy to look up sources of facts and ideas.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • References Style: Hanging indented Alphabetical on author’s last name (by increasing year within same author) Invert only first author’s name Information within source in an order determined by type of source Article: Last Name, first name, first name last name, and first name last name. Year. “Article title.” Journal Name Volume(number): 1st Page- Last Page. Lee, James Daniel. 2005. “Do Girls Change More than Boys? Gender Differences and Similarities in the Impact of New Relationships on Identities and Behaviors.” Self and Identity 4:131-47. Multiple authors… Kroska, Amy and Sarah K. Harkness. 2008. “Exploring the Role of Diagnosis in the Modified Labeling Theory of Mental Illness.” Social Psychology Quarterly 71:193-208

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • References Book Chapter: Last Name, first name. Year. “Chapter Name.” Pages in the book in Book Name, edited by first name last name. City of Publisher: Publisher. Bianciardi, Roberto. 1997. "Growing Up Italian in New York City." Pp.179-213 in Adult Narratives of Immigrant Childhoods, edited byAna Relles. Rose Hill, PA: Narrative Press. Book: Last name, first name. Year. Book Name. City of Publisher: Publisher. Stryker, Sheldon. 1980. Symbolic Interactionism: A Social Structural Version. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • References General Social Survey: Davis, James Allan and Smith, Tom W.: General Social Surveys, 1972-2008. [machine-readable data file]. Principal Investigator, James A. Davis; Director and Co-Principal Investigator, Tom W. Smith; Co-Principal Investigator, Peter V. Marsden, NORC ed. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center, producer, 2005; Storrs, CT: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut, distributor. 1 data file (53,043 logical records) and 1 codebook (2,656 pp). Website: Last Name (if available), first name. Year (if available). “Article or web page title.” Journal or Report Name Volume (if available). Retrieved date (http://address). Markowitz, Robin. 1991. “Canonizing the Popular.” Cultural Studies Central. Retrieved October 31, 2001 (http://culturalstudies.net/canon.htm). Note: Do your best to replicate this style in the case of missing information. If there is no author, use the title in that position. Always have a retrieved date and website address.

Writing a Research Report • A research report has seven components: • 7. References—an example

Writing a Research Report Some General Points • Make accurate sociological claims in your paper. Stake out positions—a kind of, “I think I have the answer to this issue,” position. • Cite facts to support your sociological claims. • If you can, use theories to support your sociological claims. • Every declaration or “fact claim” must be cited or overtly posed as speculation.

Writing a Research Report Some General Points • Anticipate your reader’s questions as you write: • help the reader understand why your topic is important • demonstrate to the reader that you adequately investigated your topic • help them anticipate what you’ll say next—everything you say should seem reasonable to say • While writing, keep thinking “The point is to: (1) establish hypotheses (2) describe how to test the hypotheses (3) give results of tests, and (4) discuss what the reader should believe about the world.”

Writing a Research Report Some General Points • There is no right answer in a research paper—Just approximate representations of the truth that are closer or further away from that truth. • The truth is: • From “Community of Scholars”: What they said about your topic in the journals, books, and other publications • From you: What your methods and analyses revealed about the topic.

Writing a Research Report Finally…Avoiding Plagiarism • What is it? • All knowledge in your head has either been copied from some place or originally discovered by you. • Most knowledge was copied. • This is true in most settings. General knowledge is copied. Most teachers’ lectures are copied knowledge. • Human culture would not exist without our keen ability to copy! • Humans are natural copiers, but that is not what is meant by the term “plagiarism.”

Writing a Research Report • The Elements of Style endorses imitation as a way for a writer to achieve his own style: • The use of language begins with imitation . . . The imitative life continues long after the writer is on his own in the language, for it is almost impossible to avoid imitating what one admires. Never imitate consciously, but do not worry about being an imitator; take pains instead to admire what is good. Then when you write in a way that comes naturally, you will echo the halloos that bear repeating. Copied from: http://www.answers.com/topic/writing-style-1

Writing a Research Report Finally…Avoiding Plagiarism • What is it? • Among other things, plagiarism refers to taking others’ work and representing it as if it were your own. • In academics this is bad because with plagiarism: • One cannot assess students’ development accurately • The person who makes his or her livelihood by scholarly pursuit is being robbed of credit • It masks the lineage of ideas and facts. “Plagiarism is to academics as Enron-accounting is to corporate America.”

Writing a Research Report Finally…Avoiding Plagiarism Lineage of Ideas: • Original sources of research are all the proof we have for some facts. Without the “paper trail” of academic thought: • People could pass incorrect ideas off as facts • We would have to keep “re-proving” things. • The contexts that generated facts and ideas get lost. • Research becomes highly inefficient as it becomes incredibly difficult to find “full information” on a topic.

Writing a Research Report Finally…Avoiding Plagiarism • To avoid plagiarism: • Document every source for information that is not “general knowledge”—this includes facts and ideas. • Cite every time a fact or idea is used unless it is clear that one citation is referring to a group of facts or ideas. • If you quote material, put quotation marks around the quoted stuff and include a page number within the citation. • It is alright to paraphrase material, but you still have to cite from where the paraphrased material came. • When in doubt, cite the source. Improper citing is grounds for failure on the course paper.

- More by User

Writing a research report in APA-style

Writing a research report in APA-style. Vesalius College SOC-203. Scientific research. Descriptive. Experimental. Secundary sources Natural observation Case studies Correlational studies Ex Post Facto research Survey Participant observation. Cause and effect relations through

706 views • 17 slides

Writing the Research Report

Contents of the Proposal. Introduction (Chapter 1)IntroductionBrief review of literatureStatement of problemHypothesisReview of Literature (Chapter 2). 2. Contents of the Proposal, cont'd. Methods (Chapter 3)ParticipantsInstruments and measurementsProceduresDesign and analysisFigures and t

421 views • 27 slides

A Reference Note on Research Report writing

Research Report Writing . for LANKAPHEINDr. Nalika GunawardenaMBBS, MD (Community Medicine) (Colombo), MPH (BioSecurity) (New Zealand)Senior Lecturer in Community Medicine,University of Colombo. 2. short and concisereflect the essence of the study (main aspects studied)/ should not b

907 views • 65 slides

Writing a Research Report. If research was not “ written up, ” did it really occur?. Writing a Research Report. Social Scientists conduct research to discover facts, truths, and explanations about the social world. They write research reports to document and store research findings.

1.48k views • 44 slides

Writing an action research report

Writing an action research report. Chapter 9. Craig A. Mertler SAGE Publications, 2014. Action Research: Improving Schools and Empowering Educators (4/e). Conventions of Academic Writing. When writing an action research report, follow style guide

555 views • 9 slides

BBI 3417 Writing Research Report

BBI 3417 Writing Research Report. LECTURE 2 ASSOC.PROF.DR.SHAMALA PARAMASIVAM. Selecting a Research Topic. How do you select a research topic? - Instructor assigns a topic for you - Instructor provides some guidelines for choosing a topic

365 views • 19 slides

Writing a research report

Writing a research report. ESL/ALP 108 Integrated Studies. The Process. Choose a topic Gather materials Narrow the topic Formulate a research question Research in-depth Write the introduction and thesis Write the body Write the conclusion Write the bibliography. Choose a topic.

956 views • 14 slides

Writing a Report

Writing a Report. English 7 Mia Jönsson. Why Write a Report ?. Some of the reasons to write a report are to : Inform Make proposals or recommendations for change Analyse and solve problems Present the findings of an investigation or project Record progress.

593 views • 15 slides

Writing a News Report

Writing a News Report. Writing a News Report. The Inverted Pyramid Most news stories are written in the inverted pyramid style. This means all the important information — most of the 5 W’s (WHO WHAT WHEN WHERE WHY HOW)— can be found in the lead .

463 views • 7 slides

Writing a Report. ENC 3246. General Considerations. make sure that the goal and scope are well defined before writing be as short as possible while still retaining all the relevant matter value of the report depends not on its length but on its accuracy and utility for its readers. Ethos.

240 views • 6 slides

BBI 3417 Writing Research Report. LECTURE 1 ASSOC.PROF.DR.SHAMALA PARAMASIVAM. What is Research?. Research simply means trying to find answers to questions to learn more about the world around us Research is the organized, systematic search for answers to the questions we ask

286 views • 8 slides

Communicating Research Results: Report Writing

Communicating Research Results: Report Writing. Report parts. Prefatory parts. Main body of the report. Appended parts. Prefatory parts. Title page. Summary. Objectives. Letter of transmittal. Results. Letter of authorization. Conclusions. Table of contents. Recommendations.

238 views • 8 slides

Writing Research Report

Writing Research Report. Indra Budi ([email protected]) Fakultas Ilmu Komputer UI. Research Report. In fact, this final stage-writing up your research-may be one of the most difficult.

619 views • 35 slides

Writing a Comprehensive Report

Writing a Comprehensive Report. EXED 530. Practical Guidelines. Write the report in the third person using phrases such as: According to the examiner… It was felt that… There seems to be… It is the professional opinion of this evaluator that…

279 views • 13 slides

Writing a Lab Report

Writing a Lab Report. Karin Paquin Inquiry Project Plan Edu 743. Objectives. Learn how to create an exceptional lab report Learn how to work in groups and create your own voice when writing their lab report

450 views • 30 slides

Writing a research report and literature review

Writing a research report and literature review. Presented by Pamela Champion Learning Skills Unit Equity and Learning Programs University of Melbourne. Language and Learning Skills Unit. Workshops Generic and department specific Resources

685 views • 48 slides

Writing a News Report. Types of News & Audiences. School News – parents, students, and teachers Local News – people who live in the community Sports News – people who are interested in sports Entertainment News – people who are interested in music, movies, & TV

470 views • 26 slides

Writing a Lab Report. Your gon’na need to know it eventually. Sourced from http://teacherweb.com/ct/rham/blueteam/h6.stm. 1). TITLE: Create a title that is short and descriptive. Often starts with, “The effects of…” and centered on page. 2). PROBLEM:

644 views • 11 slides

Writing a Lab Report. When performing a lab experiment we follow the scientific method. What is the scientific method? Purpose, Hypothesis, Procedure, Results, Conclusion. Scientific Method. What is the purpose? The purpose is why you are performing the experiment.

202 views • 12 slides

Writing a Report. Questions to ask. Why am I here?. Who is the reader and what do they need to know? Imagine an outside examiner with no knowledge of your approach. Is it clear? Get someone else to read it. Make sure it is in a logical order. Edit out any unnecessary material. Contents.

216 views • 9 slides

RESEARCH REPORT WRITING

RESEARCH REPORT WRITING. Assoc. Prof Dr. Nik Maheran Nik Muhammad UiTM Kelantan. PRELIMINARY SECTION. Title page Abstract Candidate Declaration Acknowledgement Table of Content List of Tables List of figures List of Abbreviation. CHAPTER 1-INTRODUCTION. 1.0 Introduction

334 views • 9 slides

Writing a FORMAL REPORT

Writing a FORMAL REPORT . CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 4903. AMY BINGHAM CLEAR Writing Specialist. Office Hours: Wednesdays 10AM – 12 PM Thursdays 2 PM – 4 PM *Or By Appointment Call Office: 801-581-8715 Call or Text Cell: 801-834-2868 E-mail: [email protected].

444 views • 22 slides

30+ Best Research Presentation Templates for PowerPoint (PPT)

Finding the right PowerPoint template plays an important part in getting your message across to the audience during a presentation. And it’s especially true for research presentations.

Using the right colors, graphs, infographics, and illustrations in your slides is the key to delivering information more effectively and making your presentation a success.

Today, we handpicked a great collection of research presentation PowerPoint templates for you to make the perfect slideshows for various types of research papers and studies.

Whether you’re preparing for a presentation at a school, event, or conference, there are templates in this list for all purposes. Let’s dive in.

2 Million+ PowerPoint Templates, Themes, Graphics + More

Download thousands of PowerPoint templates, and many other design elements, with a monthly Envato Elements membership. It starts at $16 per month, and gives you unlimited access to a growing library of over 2,000,000 presentation templates, fonts, photos, graphics, and more.

Pitch Deck Templates

Startup pitch deck.

Ciri Template

Maximus Template

BeMind Minimal Template

Modern PPT Templates

New & innovative.

Explore PowerPoint Templates

Science & Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

This PowerPoint template is a perfect choice for preparing a research presentation to share your scientific findings and reports.

The template has 30 unique slides with unlimited color options. There are a few infographics included in the slideshow as well.

Why This Is A Top Pick

The presentation has a very modern and creative design where you can showcase your data and information in an attractive way. You won’t be making boring research presentations ever again.

Labvire – Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

Labvire is another modern PowerPoint template you can use for various types of research presentations. It’s also ideal for laboratory-related research presentations. The template has fully customizable slide layouts with editable charts, graphs, and more. You can choose from more than 40 unique slide designs as well.

Novalabs – Science Research PowerPoint Template

Novalabs PowerPoint template features a highly visual and attractive design. The template includes 36 different slides that feature large image placeholders for adding a more visual look to your presentations. There are lots of editable graphics, shapes, and tables included in the template too. Feel free to customize them however you like.

Research & Development PowerPoint Template

The minimal and clean design of this PowerPoint template makes it a great choice for delivering more effective research presentations. With fewer distractions in each slide, you’ll be able to convey your message more easily. The template comes with 30 unique slides. You can change the colors, fonts, and shapes to your preference as well.

Marketing Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

When talking about research presentations, we can’t forget about marketing research. Most sales and marketing meetings usually include a sophisticated marketing research presentation. This PowerPoint template will help you design those research presentations without effort. It includes a total of 150 slides, featuring 30 unique slides in 5 different color schemes.

Free Business Market Research Presentation Template

This is a free PowerPoint template designed for making business market research presentations. It gives you 27 different and fully customizable slides to create professional slideshows for your business meetings.

Free Business Data Analysis & Research Presentation

With this PowerPoint template, you can create colorful and creative business research and data analysis presentation without any design skills. It includes 35 unique slides with lots of infographics and editable shapes. The template is free to use as well.

Lernen – Research Thesis PowerPoint Presentation

Larnen is the ideal PowerPoint template for making research slideshows for your thesis presentations. It includes 30 unique slides that are available in light and dark color themes. It also has editable charts and graphs.

Aristo – Research Academic PowerPoint Presentation

This PowerPoint template is also made with academic research presentations in mind. The template has a professional design with clean layouts and light colors. It comes with more than 30 different slides.

Biosearch – Science Research PowerPoint Template

You can use this PowerPoint template to make professional presentations to present research data and results. It lets you choose from 40 different slides and 90 color themes. The slides are available in both light and dark color themes as well.

Neolabs – Laboratory & Science Research PPT

Neolabs is another science research presentation made with laboratory research teams in mind. You can use it to make effective slideshows to present your research findings. There are 30 unique slides in this template.

Free Business Cost Analysis PowerPoint Template

This is a free PowerPoint and Google Slides template that comes with 35 unique slides. It’s ideal for making research presentations related to business financials.

Research & Case Study PowerPoint Template

Create the perfect case study presentation using your research data with this PowerPoint template. It includes a modern slide design with infographics and charts for effectively presenting your data.

Liron Labs – Laboratory Research PowerPoint Template

Another PowerPoint template for laboratory research presentations. This template includes 15 useful slide layouts with editable graphics, free fonts, and image placeholders. You can edit and customize the colors and text as well.

Research Thesis PowerPoint Template

Make an attractive and creative research thesis presentation using this PowerPoint template. There are over 30 unique slides in this template. You can either use dark or light color themes to create your presentations.

Colorful Thesis Research PowerPoint Template

If you want to make your research presentations look more colorful and creative, this PowerPoint template is for you. It has 15 different slides with fully customizable layouts. It has editable shapes, free fonts, and image placeholders too.

Free Data Analysis Research PowerPoint Template

This PowerPoint template is also free to download. You can also customize it using PowerPoint or Google Slides. This template is ideal for marketing agencies and teams for presenting research and data analysis.

Laboratory & Science Research PowerPoint Template

You can make more convincing and unique lab research presentations using this PowerPoint template. It features a creative design that will easily attract the attention of your audience. You can use it to make various other science and research presentations too. The template includes 30 unique slides.

The Biologist – Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

Just as the name suggests, this PowerPoint template is designed with biology and science-related presentations in mind. It includes many useful slide layouts that can be used to make various types of research presentations. There are 30 different slide designs included in this template with editable shapes and colors.

Modern Science & Research PowerPoint Template

If you’re looking for a PowerPoint template to create a modern-looking research presentation, this template is perfect for you. It features a collection of modern and attractive slides with lots of space for including images, icons, and graphs. There are 30 unique slides in the template with light and dark color themes to choose from.

Marketing Report & Research PowerPoint Template

This PowerPoint template doubles as both a research and report slideshow. You can use it to create various marketing reports as well as marketing research presentations. It comes with 30 slides that feature minimal and clean designs. It includes lots of editable charts, infographics, and tables as well.

Market Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

Another modern PowerPoint template for making market research presentations. This template includes 25 unique slides with master slides, image placeholders, and editable colors. The template is ideal for marketing agencies and corporate businesses.

Free Academic Research Thesis PowerPoint Template

This free PowerPoint template is designed for defending your academic research thesis dissertation. Needless to say, it’s a useful template for academics as well as teachers. The template features 23 unique slide layouts with customizable designs.

Free Economics Research Thesis Presentation Template

You can use this free template to create thesis and research presentations related to economics. It’s useful for academic students and gives you the freedom to choose from 21 slide layouts to make your own presentations.

Labia – Research Presentation Powerpoint Template

Labia is a research presentation template made for professionals. It comes with a set of modern slides with multipurpose designs. That means you can customize them to make many different types of research presentations. There are 30 unique slides included in this template that come in 5 different color themes.

Medical Research Infographics & Powerpoint Slides

You’ll be using lots of charts, graphs, and infographics in your presentations to showcase data in visual form. Not to mention that visuals always work well for attracting the audience’s attention. You can use the infographic slides in this template to create better research presentations. Each slide features a unique infographic with animated designs.

Foreka – Biology Education & Research Presentation PPT

Foreka is a PowerPoint template made for educational presentations, especially for covering topics related to biology. But it can also be customized to present your research presentations. The slides have very useful layouts that are most suitable for making research slide designs. There are 30 slides included with light and dark color themes.

Maua – Aesthetic Business Research PowerPoint Template

This PowerPoint template is suitable for making elegant and stylish business reports and business research presentations. It’s especially great for making background research and competitor research slideshows. The template comes with 30 slides featuring master slides, image placeholders, and more.

World Data Scientist Powerpoint Presentation Template

You can use this PowerPoint template to create research presentations for many different types of topics, industries, and projects. The template includes lots of data-centric slides where you can easily showcase your data in visual form. There are 30 unique slides included with the template as well.

Free SWOT Analysis Infographics PowerPoint Template

SWOT analysis is a commonly used methodology in business research presentations. With this free PowerPoint template, you can create stylish SWOT analysis infographics for your presentations. It includes SWOT infographics in 30 different styles.

Free Market Research Presentation Infographics PPT

This is a collection of free PowerPoint slides that feature various styles of infographics you can use in your business and market research presentations. There are 30 different infographic slides included in this template. You can edit, change colors, and customize them however you like.

Sinara – Science & Research Powerpoint Template

Sinara is a brilliant PowerPoint template you can use to craft a professional presentation for science-related research and reports. It’s available in 3 different color schemes as well as the option to customize the colors to your preference. The template comes in light and dark themes too.

Political Science and Research PowerPoint Template

This PowerPoint template will be quite useful to political science and international relations students. It features a total of 150 slides you can use to create attractive presentations for your research and methodologies. There are slides in 5 different color schemes.

How to Make a Research Poster in PowerPoint

We bet you didn’t know that you could actually design posters in PowerPoint. Well, you can and it’s very easy to do so.

The easiest way to make a poster in PowerPoint is to use a pre-made template like the one above.

You can easily copy one of the slides from a template, and resize the slide dimensions to create a vertical poster. Then add a title with a few lines of text and you’ll have yourself a poster.

Or, if you want to craft a poster from scratch, you can read our complete guide on how to create posters in PowerPoint with step-by-step instructions.

For more useful presentation templates, be sure to check out our best educational PowerPoint templates collection.

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 10 Research Report Templates with Samples and Examples

Mayuri Gangwal

Without persistent search and double-checking of facts, knowledge faces the danger of stagnation. The process of research, a systematic way of learning new things and arranging knowledge is central to human existence. Be it medicine, transport, health, logistics or even education and many other fields, research is the unsung hero of progress.

Research provides critical insights that guide decision-making and strategy formulation. It is what helps organizations understand customer preferences and competitive landscapes, allowing innovation to flower.

Market research, however, is challenging as businesses are overwhelmed with data. Sorting and extracting information from vast data can be overwhelming. Another significant challenge that hinders in-depth research efforts is limited resources.

SlideTeam Templates help businesses streamline their research process and resolve the above-listed pain points. These provide updated information on the latest market trends and customer behavior. Also, our templates encompass details, making them an indispensable tool across industries.

Download our 100% editable and customizable templates to harness the power of well-structured research presentations.

Do you want to learn more about qualitative research report templates and market research report templates? We offer bet-in-class templates to ease your workload and increase efficiency, if you click on the links above.

Let’s explore these templates now!

Template 1: Market Research Report for Food Industry

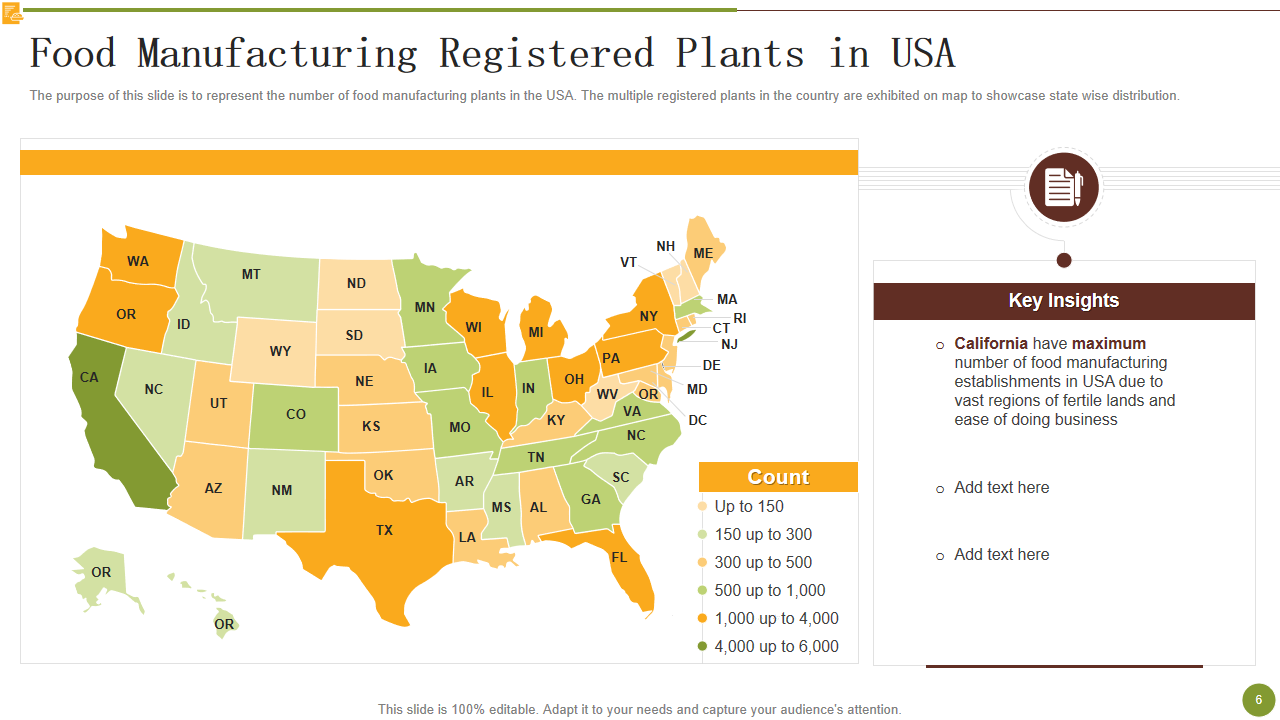

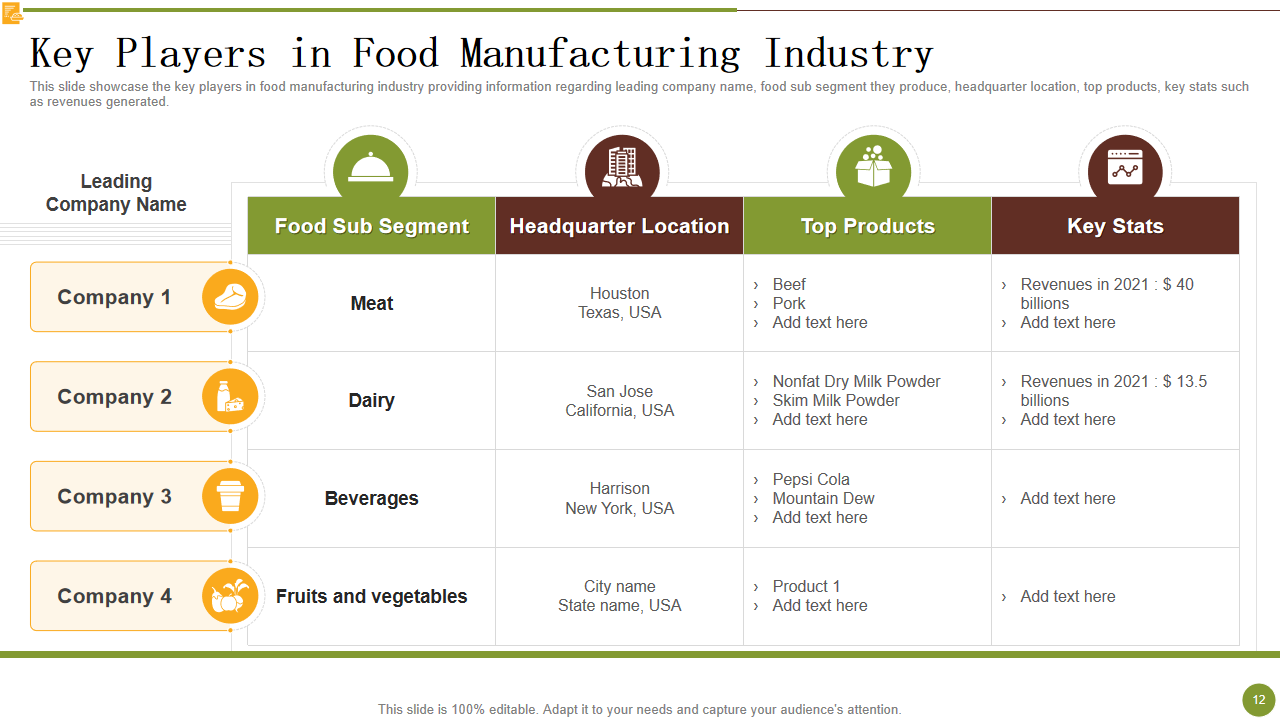

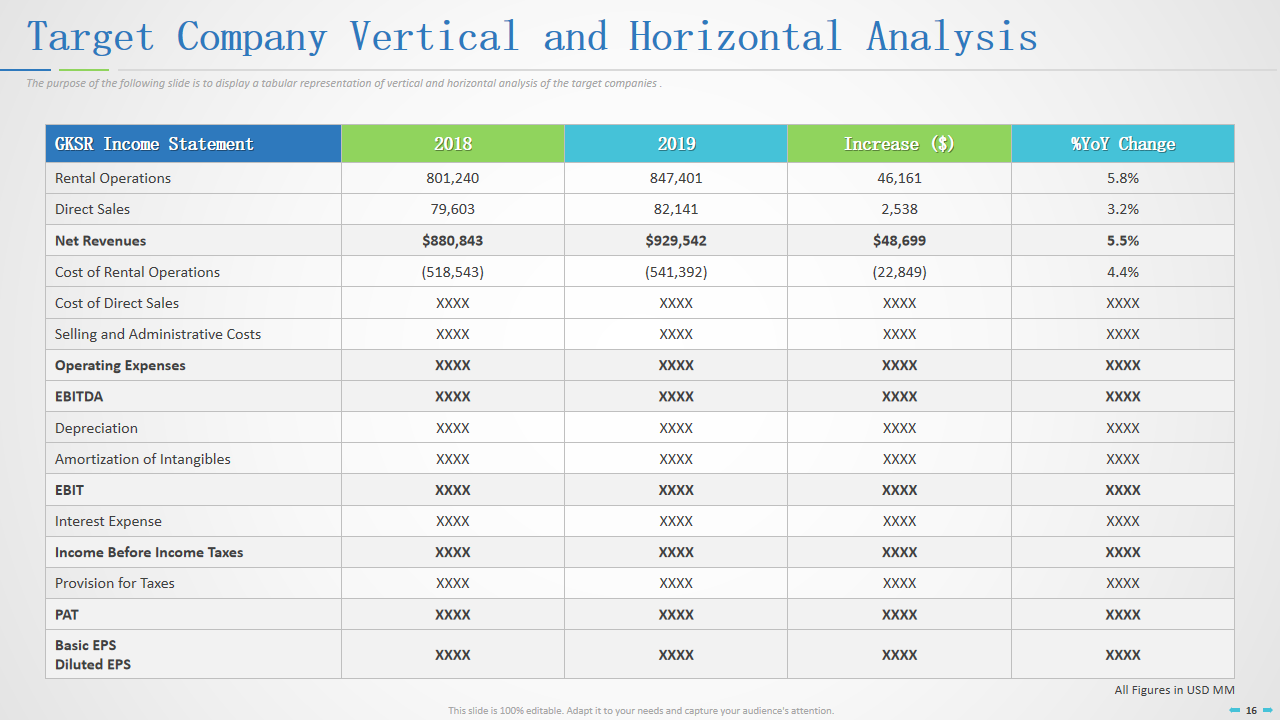

This template offers a comprehensive view of the US food market. It identifies vital market trends, competitive landscapes, and economic indicators. It also helps businesses estimate their GDP and revenue by employing SWOT and PESTEL analysis. Moreover, it presents an Industry 4.0 action plan to overcome manufacturing challenges.

Download Now!

Template 2: Company Stock Analysis and Equity Research Template

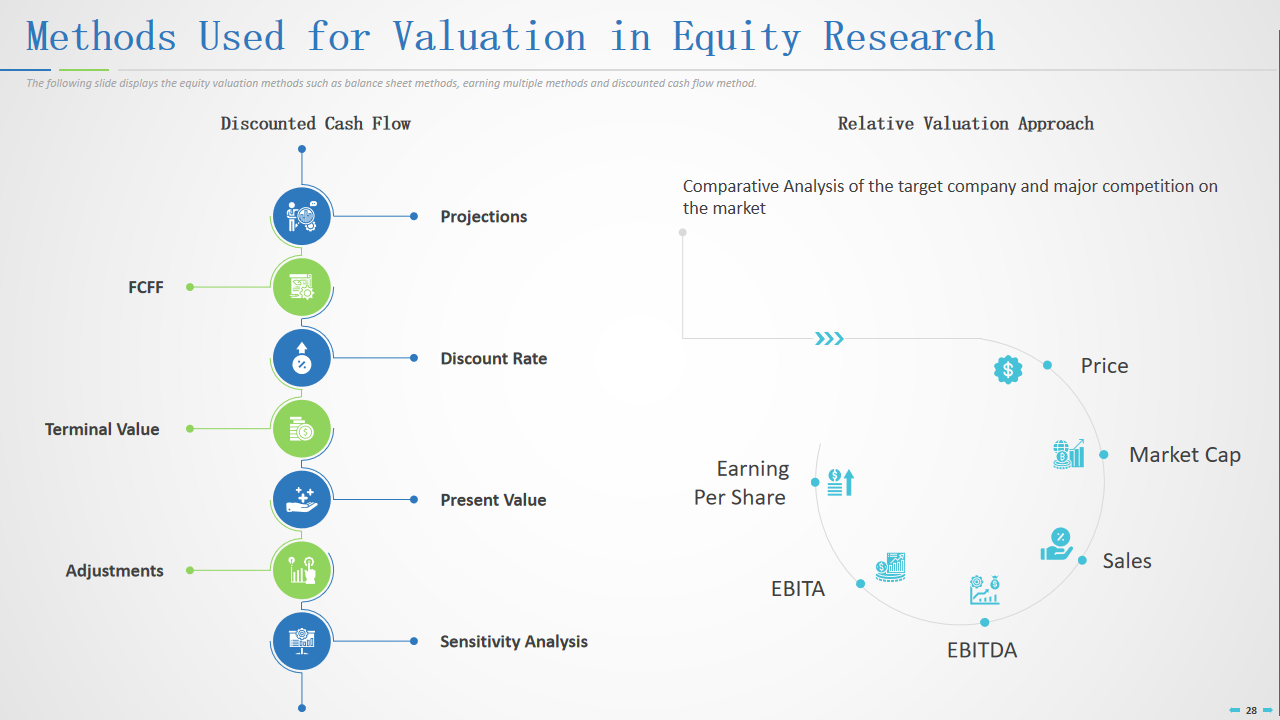

Company Stock Analysis and equity research demands precision. A few common challenges include how to decipher vast financial data, market dynamics, and industry trends. These reports help new investors understand the complexities. Our template addresses these hurdles, as this vital tool transforms complex data into actionable insights that empower investors to make informed decisions.

Template 3: Table of Contents for Market Research Report for Food Industry