- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo

Three prompts to get started.

Why does a writing intervention work? While it may seem counterintuitive that writing about negative experiences has a positive effect, some have posited that narrating the story of a past negative event or an ongoing anxiety “frees up” cognitive resources. Research suggests that trauma damages brain tissue, but that when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain. This matters, both personally and professionally. In a moment still permeated with epic stress and loss, we need to call in all possible supports. So, what does this look like in practice, and how can you put this powerful tool into effect? The author offers three practices, with prompts, to get you started.

Even as we inoculate our bodies and seemingly move out of the pandemic, psychologically we are still moving through it. We owe it to ourselves — and our coworkers — to make space for processing this individual and collective trauma. A recent op-ed in the New York Times Sunday Review affirms what I, as a writer and professor of writing, have witnessed repeatedly, up close: expressive writing can heal us.

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo is an author , TEDx speaker, and founder of Bold Voice Collaborative , an organization fostering growth, resilience, and community through storytelling for individuals and organizations. An adjunct faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Communication, her writing has appeared in venues including The Washington Post, The Guardian, and CNN.com.

Partner Center

Narrative Therapy: Definition, Techniques & Interventions

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Narrative therapy, is a powerful psychotherapeutic approach that empowers clients to explore and reshape their life stories, particularly those overwhelmed by challenges and emotional distress.

During sessions, clients engage in open dialogues with their therapists, delving into their narratives and actively challenging the ones that contribute to their struggles.

By separating problems from personal identity, narrative therapy emphasizes the belief that individuals are the ultimate authorities in their own lives.

Through this collaborative process, clients gain a deep understanding of their values and skills, enabling them to effectively confront present and future issues and pave the way for transformative change.

When was narrative therapy developed?

Narrative therapy was developed in the 1980s by therapists Michael White and David Epston. It is still a relatively novel approach to therapy that seeks to have an empowering effect and offer therapy that is non-blaming and non-pathological in nature.

What is a narrative?

A narrative is a story. As humans, we have many stories about ourselves, others, our abilities, our self-esteem , and our work, among many others.

How we have developed these stories is determined by how we have linked certain events together in a sequence and by the meaning attributed to them.

We like to interpret daily experiences in life, seeking to make them meaningful. The stories we have about our lives are created through linking certain events together in a particular sequence across a period of time and finding ways of making sense of them – this meaning forms the plot of the story.

As more and more events are selected and gathered into the dominant plot, the story gains richness and thickness.

The idea is that identity is formed by an individual’s life narrative, and several narratives are at work at once. The interpretation of a narrative can influence thinking, feelings, and behavior.

Many narratives are useful and healthy, whereas others can result in mental distress. Mental health symptoms can come about when there is an unhealthy or negative narrative or if there is a misunderstanding or misinterpretation of a narrative.

What is the aim of narrative therapy?

Narrative therapy seeks to change a problematic narrative into a more productive or healthier one. This is often done by assigning the person the role of narrator in their own story.

Narrative therapy helps to separate the person from the problem and empowers the person to rely on their own skills to minimize problems that exist in their lives.

This therapy aims to teach the person to view alternative stories and address their issues in a more productive way.

Narrative therapy can be used with individuals but can also prove useful for couples or families.

Narrative therapists are also not interested in diagnosing individuals – there is no use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) during any point of the therapy.

What is the role of the therapist?

The role of the narrative therapist is to search for an alternative way of understanding a client’s narrative or an alternative way to describe it.

The belief is that telling a story is a form of action toward change. Therefore, the therapist will help clients to objectify their problems, frame these problems within a larger sociocultural context, and teach the person how to make room for other stories.

During therapy, the therapist acts as a non-directive collaborator. They treat the client as the expert on their own problems and do not impose judgments.

Instead, the therapist is purely curious and investigative. They are not particularly interested in the cause of a problem but are open to a client’s perception of the cause.

Narrative Therapy Techniques

Putting together the narrative

The therapists help their clients to put together their narratives. This will usually involve listening to the client explain their stories and any issues that they want to bring up.

This allows the person to express their thoughts and explore events in their lives and the meanings they have placed on these experiences.

The therapist may find what is known as a ‘problem-saturated narrative’ comes up, which will be what is causing the client the most distress.

As the story comes together, the client becomes an observer of their story and can then review this with the therapist.

When the therapist communicates to the client during this stage, they will make sure to utilize the client’s use of language since the client is treated as the expert in their narrative.

Externalizing the problem

Once the story is put together, the idea is that it allows the client to observe themselves. The therapist encourages the client to create distance between the individual and their problems, called externalization.

The externalization techniques lead clients towards viewing their problems or behaviors as external instead of an unchangeable part of themselves.

The therapist may ask the client to give a name to the problem so it is seen as a separate entity, such as ‘anger’ or ‘worry.’ The client will then be encouraged to use the given name of the problem when talking about it. Likewise, the therapist will ask questions referring to the problem by the given name.

The distance given to the problem allows people to focus on changing unwanted behaviors.

As people practice externalization, they will see that they can change. The general idea is that it is easier to change a behavior that they do than to change a core personality characteristic.

They will realize that they themselves are not the problem; instead, the problem is the problem.

Deconstruction

Often, when a client has a problematic story, especially when it has been prevalent for a long time, the problem can feel overwhelming, confusing, or unsolvable.

Because of these feelings, people can use overgeneralized statements which can make the problematic stories worse.

The narrative therapist would work with the individual to break down or deconstruct their stories into smaller, more manageable parts to clarify the problem.

Deconstructing makes the problems more specific and reduces overgeneralizing; it also clarifies what the core issue or issues may be. Through deconstructing, the whole picture becomes easier to understand.

The therapist and client may also seek to deconstruct identity and have an awareness of larger societal issues, e.g., sociocultural and political effects which may be acting on the client.

They may find that the context of gender, class, race, culture, and sexual identity also play a part in the interpretations and meanings given to events.

Unique outcomes

When someone’s problematic stories are well established, people can become stuck in them, unable to view alternative versions of the story. A narrative therapist will help people challenge their stories and encourage them to consider alternative stories.

Unique outcomes refer to the exceptions to the dominant story. It may also be known as ‘re-authoring’ or ‘re-storying,’ as clients go through their experiences to find alterations to their story or make a whole new one.

There are hundreds of different stories since everyone interprets experiences differently and finds their own meaning from them. The therapist will help the client to build upon an alternative or preferred story.

These unique outcomes contrast a problem, reflect a person’s true nature, and allow someone to rewrite their story.

Building upon stories from another perspective can help to overcome problems and build the confidence the person needs to heal from them.

Benefits of narrative therapy

Empowers the individual.

As this therapy stresses that people do not label themselves negatively (e.g., as the problem), this can help them feel less powerless in distressing situations.

They find that they have more control over the stories they have in their lives and how they approach difficult events.

Narrative therapy treats individuals with respect and supports the bravery it has taken for them to choose to work through their personal challenges.

Non-confrontational

This is a non-judgmental approach to therapy, meaning that the clients are not blamed for anything described in their stories.

Likewise, the clients are encouraged not to blame others or themselves. The focus is instead placed on noticing and changing unhelpful stories about themselves and others.

The client is treated as an expert

Narrative therapy does not aim to change a person; rather, it allows them to become an expert in their own lives.

The therapist holds that the clients know themselves well and work as collaborative partners with the client.

This therapy allows people to not only find their voice but to use this voice for good, enabling them to become experts and live in a way that reflects their goals and values.

Context is considered

This therapy may also help the client view their problems differently. These can be social, political, and cultural, among others.

The clients recognize that these contexts matter and can influence how they view themselves and their stories.

What can narrative therapy help with?

Narrative therapy may help treat the symptoms of a variety of conditions, including:

Anxiety disorders

Depressive disorders

Eating disorders

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( ADHD )

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

As well as mental health conditions, narrative therapy may also be useful for the following:

Those who feel like they are overwhelmed by negative experiences, thoughts, or emotions.

Those with attachment issues .

Those who are suffering from grief.

Those who have issues with low self-esteem.

Those who often feel powerless in many situations.

How is narrative therapy used?

For individuals, narrative therapy challenges the dominant problematic stories that prevent people from living their best lives.

Through the externalizing technique, people can learn to separate themselves from the problem.

They learn to identify alternative stories, widen their views of themselves, challenge old and unhealthy beliefs, and be open to new ways of living that reflect a more accurate and healthier story.

For couples or families, externalizing problems can facilitate positive interaction.

It can also make negative communication more accepting and meaningful. Seeing problems objectively can help couples and families reconnect and strengthen their relationships.

Once problems have been identified, this can be used to address how the problem has challenged the core strength of their bond.

How effective is narrative therapy?

Below are some of the studies which have investigated the effectiveness of narrative therapy:

A research study looked at evaluating the effectiveness of narrative therapy in increasing couples’ intimacy and its dimensions.

The results showed that this therapy significantly increased intimacy and on three dimensions of emotional, communication, and general intimacy, concluding that narrative therapy can provide valuable implications for the mental health of couples (Khodabakhsh et al., 2015).

Research has found that married women experienced increased levels of marital satisfaction after being treated with narrative therapy (Ghavibazou et al., 2020).

A study of adults with depression and anxiety looked at the effects of narrative therapy and found improvements in their self-reports of quality of life, and they had decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression (Shakeri et al., 2020).

A small sample pilot study aimed to determine whether narrative therapy was effective in helping young people with Autism who present with emotional and behavioral difficulties.

It was found that there were significant improvements in psychological distress and emotional symptoms (Cashin et al., 2013).

A study looked at the effectiveness of narrative therapy in boosting 8-10-year old’s social and emotional skills. The results showed that the children showed significant improvements in self-awareness, self-management, empathy, and responsible decision-making (Beaudoin et al., 2016).

A study explored group narrative therapy for improving the school behavior of a small sample of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Posttreatment ratings by teachers showed that there was a significant effect on reducing ADHD symptoms one week after completing the therapy sessions, and this was sustained after 30 days (Looyeh et al., 2012).

Limitations

One of the major limitations of narrative therapy is that research into its effectiveness is still lacking.

Further research is also needed to determine what mental health conditions narrative therapy might treat most effectively.

A reason for the lack of research is that it is still a relatively new approach to therapy. Another reason could be due to it being difficult to quantify.

The view that narrative therapists have is that knowledge is subjective and constructed by each person.

They accept there is no universal truth, so some narrative therapists make the argument that this therapy should be studied qualitatively rather than quantitatively.

How to get started

Narrative therapy is a specialized approach to counseling with training opportunities for therapists to learn how to use this approach with clients.

Finding the right therapist can involve looking online through therapist directories. Alternatively, you may consider asking your doctor to refer you to a professional in your area with the right training and experience.

It is important to choose the right therapist for you. Consider whether you feel comfortable discussing personal information with them. Don’t be afraid to seek a different therapist if the one you have does not quite suit your needs.

When choosing a therapist, consider thinking about what your deal breakers are, important qualities, and any other characteristics you value.

What questions can you ask yourself when considering therapy?

When you are ready to select a therapist, think about the following:

1. What type of therapy do you want? – Do you want individual, couples, family therapy, or another type?

2. What are your main goals for therapy?

3. Whether you can commit the time each week – what days and times are most convenient for you?

What can be expected during the first therapy session?

During the first narrative therapy session, the therapist may ask you to begin sharing your story, and they may ask questions about why you are seeking treatment.

The therapist may also want to know about how your problems are affecting your life and what your goals for the future are.

Furthermore, they are likely to discuss aspects of treatment, such as how often you will meet and how your treatment may change from one session to the next.

What are some considerations for narrative therapy?

This therapy can be very in-depth, exploring a wide range of factors that can influence the development of your stories.

It also involves talking about problems as well as strengths which may be difficult for some people.

The therapist will help you to explore your dominant story in-depth and discover how it may be contributing to emotional distress, as well as uncover strengths that can help you to approach your problems differently.

You should expect to re-evaluate your judgments about yourself since narrative therapy encourages you to challenge and reassess these thoughts and replace them with more realistic or positive ones.

It also challenges you to separate yourself from your problems which can be difficult, but this process helps you learn to give yourself credit for making the right decisions for you.

Do you need mental health help?

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email [email protected] .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

Further Information

Wallis, J., Burns, J., & Capdevila, R. (2011). What is narrative therapy and what is it not? The usefulness of Q methodology to explore accounts of White and Epston’s (1990) approach to narrative therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(6), 486-497.

Hutto, D. D., & Gallagher, S. (2017). Re-Authoring narrative therapy: Improving our selfmanagement tools. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 24(2), 157-167.

Morgan, A. (2000). What is narrative therapy? (p. 116). Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications.

Beaudoin, M. N., Moersch, M., & Evare, B. S. (2016). The effectiveness of narrative therapy with children’s social and emotional skill development: an empirical study of 813 problem-solving stories. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 35(3), 42-59.

Cashin, A., Browne, G., Bradbury, J., & Mulder, A. (2013). The effectiveness of narrative therapy with young people with autism. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(1), 32-41.

Ghavibazou, E., Hosseinian, S., & Abdollahi, A. (2020). Effectiveness of narrative therapy on communication patterns for women experiencing low marital satisfaction. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 195-207.

Khodabakhsh, M. R., Kiani, F., Noori Tirtashi, E., & Khastwo Hashjin, H. (2015). The effectiveness of narrative therapy on increasing couples intimacy and its dimensions: Implication for treatment. Family Counseling and Psychotherapy, 4(4), 607-632.

Looyeh, M. Y., Kamali, K., & Shafieian, R. (2012). An exploratory study of the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the school behavior of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(5), 404-410.

Shakeri, J., Ahmadi, S. M., Maleki, F., Hesami, M. R., Moghadam, A. P., Ahmadzade, A., Shirzadi, M. & Elahi, A. (2020). Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on depression, quality of life, and anxiety in people with amphetamine addiction: a randomized clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 45(2), 91.

Related Articles

Understanding Therapy

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Emotion Focused Therapy

Adlerian Therapy: Key Concepts & Techniques

What Is Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) Therapy?

Freudian Psychology , Understanding Therapy

What Is Transference In Psychology?

Understanding Therapy , Anxiety

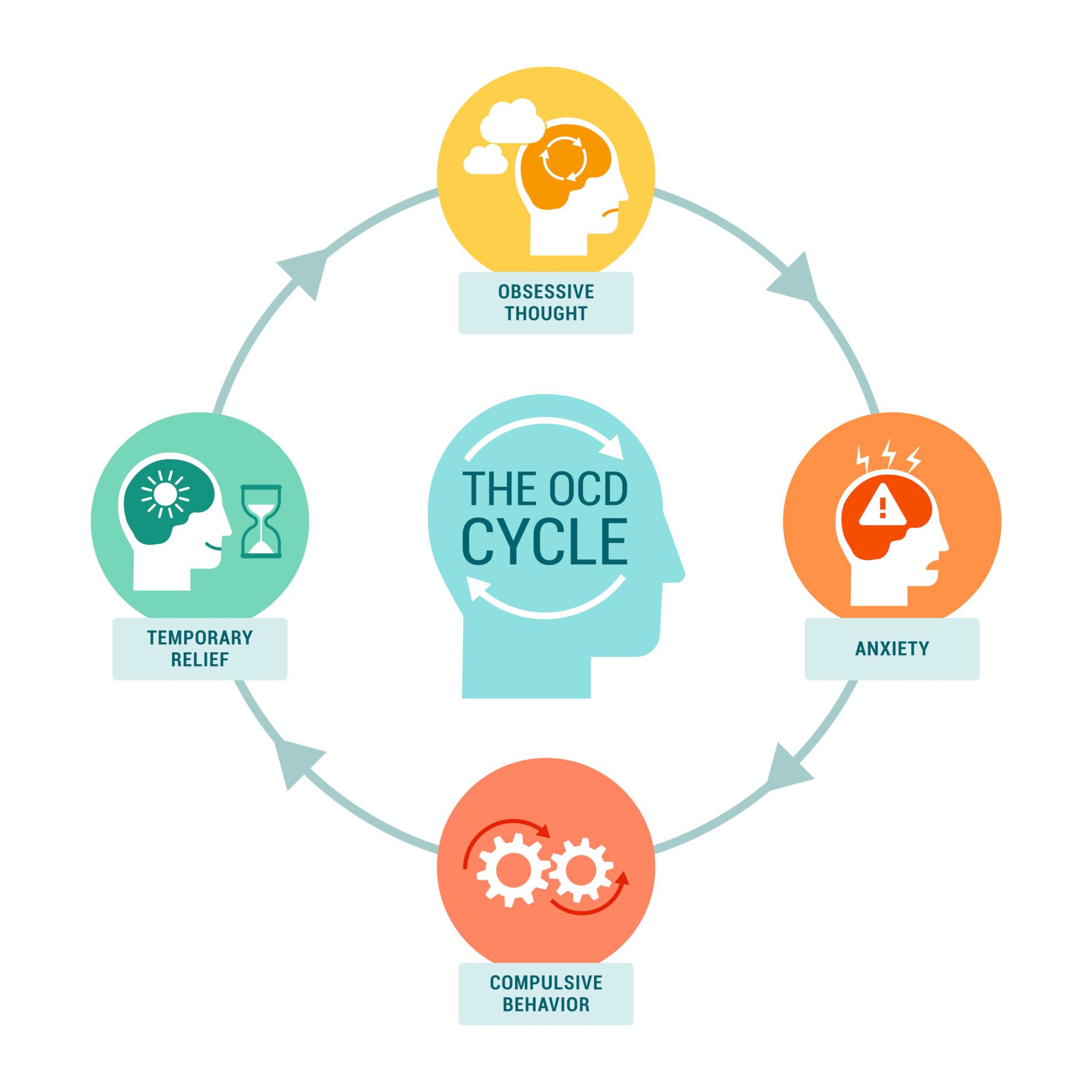

How to Treat OCD On Your Own

The state of AI in early 2024: Gen AI adoption spikes and starts to generate value

If 2023 was the year the world discovered generative AI (gen AI) , 2024 is the year organizations truly began using—and deriving business value from—this new technology. In the latest McKinsey Global Survey on AI, 65 percent of respondents report that their organizations are regularly using gen AI, nearly double the percentage from our previous survey just ten months ago. Respondents’ expectations for gen AI’s impact remain as high as they were last year , with three-quarters predicting that gen AI will lead to significant or disruptive change in their industries in the years ahead.

About the authors

This article is a collaborative effort by Alex Singla , Alexander Sukharevsky , Lareina Yee , and Michael Chui , with Bryce Hall , representing views from QuantumBlack, AI by McKinsey, and McKinsey Digital.

Organizations are already seeing material benefits from gen AI use, reporting both cost decreases and revenue jumps in the business units deploying the technology. The survey also provides insights into the kinds of risks presented by gen AI—most notably, inaccuracy—as well as the emerging practices of top performers to mitigate those challenges and capture value.

AI adoption surges

Interest in generative AI has also brightened the spotlight on a broader set of AI capabilities. For the past six years, AI adoption by respondents’ organizations has hovered at about 50 percent. This year, the survey finds that adoption has jumped to 72 percent (Exhibit 1). And the interest is truly global in scope. Our 2023 survey found that AI adoption did not reach 66 percent in any region; however, this year more than two-thirds of respondents in nearly every region say their organizations are using AI. 1 Organizations based in Central and South America are the exception, with 58 percent of respondents working for organizations based in Central and South America reporting AI adoption. Looking by industry, the biggest increase in adoption can be found in professional services. 2 Includes respondents working for organizations focused on human resources, legal services, management consulting, market research, R&D, tax preparation, and training.

Also, responses suggest that companies are now using AI in more parts of the business. Half of respondents say their organizations have adopted AI in two or more business functions, up from less than a third of respondents in 2023 (Exhibit 2).

Gen AI adoption is most common in the functions where it can create the most value

Most respondents now report that their organizations—and they as individuals—are using gen AI. Sixty-five percent of respondents say their organizations are regularly using gen AI in at least one business function, up from one-third last year. The average organization using gen AI is doing so in two functions, most often in marketing and sales and in product and service development—two functions in which previous research determined that gen AI adoption could generate the most value 3 “ The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier ,” McKinsey, June 14, 2023. —as well as in IT (Exhibit 3). The biggest increase from 2023 is found in marketing and sales, where reported adoption has more than doubled. Yet across functions, only two use cases, both within marketing and sales, are reported by 15 percent or more of respondents.

Gen AI also is weaving its way into respondents’ personal lives. Compared with 2023, respondents are much more likely to be using gen AI at work and even more likely to be using gen AI both at work and in their personal lives (Exhibit 4). The survey finds upticks in gen AI use across all regions, with the largest increases in Asia–Pacific and Greater China. Respondents at the highest seniority levels, meanwhile, show larger jumps in the use of gen Al tools for work and outside of work compared with their midlevel-management peers. Looking at specific industries, respondents working in energy and materials and in professional services report the largest increase in gen AI use.

Investments in gen AI and analytical AI are beginning to create value

The latest survey also shows how different industries are budgeting for gen AI. Responses suggest that, in many industries, organizations are about equally as likely to be investing more than 5 percent of their digital budgets in gen AI as they are in nongenerative, analytical-AI solutions (Exhibit 5). Yet in most industries, larger shares of respondents report that their organizations spend more than 20 percent on analytical AI than on gen AI. Looking ahead, most respondents—67 percent—expect their organizations to invest more in AI over the next three years.

Where are those investments paying off? For the first time, our latest survey explored the value created by gen AI use by business function. The function in which the largest share of respondents report seeing cost decreases is human resources. Respondents most commonly report meaningful revenue increases (of more than 5 percent) in supply chain and inventory management (Exhibit 6). For analytical AI, respondents most often report seeing cost benefits in service operations—in line with what we found last year —as well as meaningful revenue increases from AI use in marketing and sales.

Inaccuracy: The most recognized and experienced risk of gen AI use

As businesses begin to see the benefits of gen AI, they’re also recognizing the diverse risks associated with the technology. These can range from data management risks such as data privacy, bias, or intellectual property (IP) infringement to model management risks, which tend to focus on inaccurate output or lack of explainability. A third big risk category is security and incorrect use.

Respondents to the latest survey are more likely than they were last year to say their organizations consider inaccuracy and IP infringement to be relevant to their use of gen AI, and about half continue to view cybersecurity as a risk (Exhibit 7).

Conversely, respondents are less likely than they were last year to say their organizations consider workforce and labor displacement to be relevant risks and are not increasing efforts to mitigate them.

In fact, inaccuracy— which can affect use cases across the gen AI value chain , ranging from customer journeys and summarization to coding and creative content—is the only risk that respondents are significantly more likely than last year to say their organizations are actively working to mitigate.

Some organizations have already experienced negative consequences from the use of gen AI, with 44 percent of respondents saying their organizations have experienced at least one consequence (Exhibit 8). Respondents most often report inaccuracy as a risk that has affected their organizations, followed by cybersecurity and explainability.

Our previous research has found that there are several elements of governance that can help in scaling gen AI use responsibly, yet few respondents report having these risk-related practices in place. 4 “ Implementing generative AI with speed and safety ,” McKinsey Quarterly , March 13, 2024. For example, just 18 percent say their organizations have an enterprise-wide council or board with the authority to make decisions involving responsible AI governance, and only one-third say gen AI risk awareness and risk mitigation controls are required skill sets for technical talent.

Bringing gen AI capabilities to bear

The latest survey also sought to understand how, and how quickly, organizations are deploying these new gen AI tools. We have found three archetypes for implementing gen AI solutions : takers use off-the-shelf, publicly available solutions; shapers customize those tools with proprietary data and systems; and makers develop their own foundation models from scratch. 5 “ Technology’s generational moment with generative AI: A CIO and CTO guide ,” McKinsey, July 11, 2023. Across most industries, the survey results suggest that organizations are finding off-the-shelf offerings applicable to their business needs—though many are pursuing opportunities to customize models or even develop their own (Exhibit 9). About half of reported gen AI uses within respondents’ business functions are utilizing off-the-shelf, publicly available models or tools, with little or no customization. Respondents in energy and materials, technology, and media and telecommunications are more likely to report significant customization or tuning of publicly available models or developing their own proprietary models to address specific business needs.

Respondents most often report that their organizations required one to four months from the start of a project to put gen AI into production, though the time it takes varies by business function (Exhibit 10). It also depends upon the approach for acquiring those capabilities. Not surprisingly, reported uses of highly customized or proprietary models are 1.5 times more likely than off-the-shelf, publicly available models to take five months or more to implement.

Gen AI high performers are excelling despite facing challenges

Gen AI is a new technology, and organizations are still early in the journey of pursuing its opportunities and scaling it across functions. So it’s little surprise that only a small subset of respondents (46 out of 876) report that a meaningful share of their organizations’ EBIT can be attributed to their deployment of gen AI. Still, these gen AI leaders are worth examining closely. These, after all, are the early movers, who already attribute more than 10 percent of their organizations’ EBIT to their use of gen AI. Forty-two percent of these high performers say more than 20 percent of their EBIT is attributable to their use of nongenerative, analytical AI, and they span industries and regions—though most are at organizations with less than $1 billion in annual revenue. The AI-related practices at these organizations can offer guidance to those looking to create value from gen AI adoption at their own organizations.

To start, gen AI high performers are using gen AI in more business functions—an average of three functions, while others average two. They, like other organizations, are most likely to use gen AI in marketing and sales and product or service development, but they’re much more likely than others to use gen AI solutions in risk, legal, and compliance; in strategy and corporate finance; and in supply chain and inventory management. They’re more than three times as likely as others to be using gen AI in activities ranging from processing of accounting documents and risk assessment to R&D testing and pricing and promotions. While, overall, about half of reported gen AI applications within business functions are utilizing publicly available models or tools, gen AI high performers are less likely to use those off-the-shelf options than to either implement significantly customized versions of those tools or to develop their own proprietary foundation models.

What else are these high performers doing differently? For one thing, they are paying more attention to gen-AI-related risks. Perhaps because they are further along on their journeys, they are more likely than others to say their organizations have experienced every negative consequence from gen AI we asked about, from cybersecurity and personal privacy to explainability and IP infringement. Given that, they are more likely than others to report that their organizations consider those risks, as well as regulatory compliance, environmental impacts, and political stability, to be relevant to their gen AI use, and they say they take steps to mitigate more risks than others do.

Gen AI high performers are also much more likely to say their organizations follow a set of risk-related best practices (Exhibit 11). For example, they are nearly twice as likely as others to involve the legal function and embed risk reviews early on in the development of gen AI solutions—that is, to “ shift left .” They’re also much more likely than others to employ a wide range of other best practices, from strategy-related practices to those related to scaling.

In addition to experiencing the risks of gen AI adoption, high performers have encountered other challenges that can serve as warnings to others (Exhibit 12). Seventy percent say they have experienced difficulties with data, including defining processes for data governance, developing the ability to quickly integrate data into AI models, and an insufficient amount of training data, highlighting the essential role that data play in capturing value. High performers are also more likely than others to report experiencing challenges with their operating models, such as implementing agile ways of working and effective sprint performance management.

About the research

The online survey was in the field from February 22 to March 5, 2024, and garnered responses from 1,363 participants representing the full range of regions, industries, company sizes, functional specialties, and tenures. Of those respondents, 981 said their organizations had adopted AI in at least one business function, and 878 said their organizations were regularly using gen AI in at least one function. To adjust for differences in response rates, the data are weighted by the contribution of each respondent’s nation to global GDP.

Alex Singla and Alexander Sukharevsky are global coleaders of QuantumBlack, AI by McKinsey, and senior partners in McKinsey’s Chicago and London offices, respectively; Lareina Yee is a senior partner in the Bay Area office, where Michael Chui , a McKinsey Global Institute partner, is a partner; and Bryce Hall is an associate partner in the Washington, DC, office.

They wish to thank Kaitlin Noe, Larry Kanter, Mallika Jhamb, and Shinjini Srivastava for their contributions to this work.

This article was edited by Heather Hanselman, a senior editor in McKinsey’s Atlanta office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Moving past gen AI’s honeymoon phase: Seven hard truths for CIOs to get from pilot to scale

A generative AI reset: Rewiring to turn potential into value in 2024

Implementing generative AI with speed and safety

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

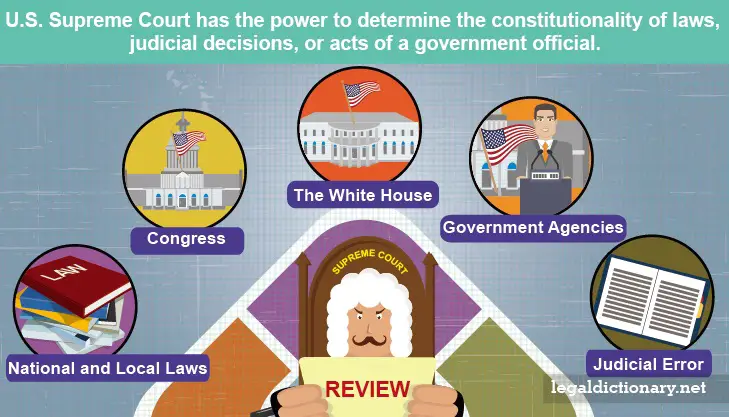

Judicial Review

In the United States, the courts have the ability to scrutinize statutes, administrative regulations, and judicial decisions to determine whether they violate provisions of existing laws, or whether they violate the individual State or United States Constitution . A court having judicial review power, such as the United States Supreme Court, may choose to quash or invalidate statutes, laws, and decisions that conflict with a higher authority. Judicial review is a part of the checks and balances system in which the judiciary branch of the government supervises the legislative and executive branches of the government. To explore this concept, consider the following judicial review definition.

Definition of Judicial Review

- Noun. The power of the U.S. Supreme Court to determine the constitutionality of laws, judicial decisions, or acts of a government official.

Origin: Early 1800s U.S. Supreme Court

What is Judicial Review

While the authors of the U.S. Constitution were unsure whether the federal courts should have the power to review and overturn executive and congressional acts, the Supreme Court itself established its power of judicial review in the early 1800s with the case of Marbury v. Madison (5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 2L Ed. 60). The case arose out of the political wrangling that occurred in the weeks before President John Adams left office for Thomas Jefferson.

The new President and Congress overturned the many judiciary appointments Adams had made at the end of his term, and overturned the Congressional act that had increased the number of Presidential judicial appointments. For the first time in the history of the new republic , the Supreme Court ruled that an act of Congress was unconstitutional. By asserting that it is emphatically the judicial branch ’s province to state and clarify what the law actually is, the court assured its position and power over judicial review.

Topics Subject to Judicial Review

The judicial review process exists to help ensure no law enacted, or action taken, by the other branches of government , or by lower courts, contradicts the U.S. Constitution. In this, the U.S. Supreme Court is the “supreme law of the land.” Individual State Supreme Courts have the power of judicial review over state laws and actions, charged with making rulings consistent with their state constitutions. Topics that may be brought before the Supreme Court may include:

- Executive actions or orders made by the President

- Regulations issued by a government agency

- Legislative actions or laws made by Congress

- State and local laws

- Judicial error

Judicial Review Example Cases

Throughout the years, the Supreme Court has made many important decisions on issues of civil rights , rights of persons accused of crimes, censorship , freedom of religion, and other basic human rights. Below are some notable examples.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

The history of modern day Miranda rights begins in 1963, when Ernesto Miranda was arrested for, and interrogated about, the rape of an 18-year-old woman in Phoenix, Arizona. During the lengthy interrogation, Miranda, who had never requested a lawyer , confessed and was later convicted of rape and sent to prison . Later, an attorney appealed the case, requesting judicial review by the Supreme Court, claiming that Ernesto Miranda’s rights had been violated, as he never knew he didn’t have to speak at all with the police.

The Supreme Court, in 1966, overturned Miranda’s conviction, and the court ruled that all suspects must be informed of their right to an attorney, as well as their right to say nothing, before questioning by law enforcement. The ruling declared that any statement, confession, or evidence obtained prior to informing the person of their rights would not be admissible in court. While Miranda was retried and ultimately convicted again, this landmark Supreme Court ruling resulted in the commonly heard “Miranda Rights” read to suspects by police everywhere in the country.

Weeks v. United States (1914)

Federal agents, suspecting Fremont Weeks was distributing illegal lottery chances through the U.S. mail system, entered and searched his home, taking some of his personal papers with them. The agents later returned to Weeks’ house to collect more evidence, taking with them letters and envelopes from his drawers. Although the agents had no search warrant , seized items were used to convict Weeks of operating an illegal gambling ring.

The matter was brought to judicial review before the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether Weeks’ Fourth Amendment right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure , as well as his Fifth Amendment right to not testify against himself, had been violated. The Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled that the agents had unlawfully searched for, seized, and kept Weeks’ letters. This landmark ruling led to the “ Exclusionary Rule ,” which prohibits the use of evidence obtained in an illegal search in trial .

Plessey v. Ferguson (1869)

Having been arrested and convicted for violating the law requiring “Blacks” to ride in separate train cars, Homer Plessey appealed to the Supreme Court, stating the so called “Jim Crow” laws violated his 14th Amendment right to receive “equal protection under the law.” During the judicial review, the state argued that Plessey and other Blacks were receiving equal treatment, but separately. The Court upheld Plessey’s conviction, and ruled that the 14th Amendment guarantees the right to “equal facilities,” not the “same facilities.” In this ruling, the Supreme Court created the principle of “ separate but equal .”

United States v. Nixon (“Watergate”) (1974)

During the 1972 election campaign between Republican President Richard Nixon and Democratic Senator George McGovern, the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate building was burglarized. Special federal prosecutor Archibald Cox was assigned to investigate the matter, but Nixon had him fired before he could complete the investigation. The new prosecutor obtained a subpoena ordering Nixon to release certain documents and tape recordings that almost certainly contained evidence against the President.

Nixon, asserting an “absolute executive privilege” regarding any communications between high government officials and those who assist and advise them, produced heavily edited transcripts of 43 taped conversations, asking in the same instant that the subpoena be quashed and the transcripts disregarded. The Supreme Court first ruled that the prosecutor had submitted sufficient evidence to obtain the subpoena, then specifically addressed the issue of executive privilege. Nixon’s declaration of an “absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,” was flatly rejected. In the midst of this “Watergate scandal,” Nixon resigned from office just 15 days later, on August 9, 1974.

The Authority Behind Judicial Review

Interestingly, Article III of the U.S. Constitution does not specifically give the judicial branch the authority of judicial review. It states specifically:

“The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority.”

This language clearly does not state whether the Supreme Court has the power to reverse acts of Congress. The power of judicial review has been garnered by assumption of that power:

- Power From the People . Alexander Hamilton, rather than attempting to prove that the Supreme Court had the power of judicial review, simply assumed it did. He then focused his efforts on persuading the people that the power of judicial review was a positive thing for the people of the land.

- Constitution Binding on Congress . Hamilton referred to the section that states “No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid,” and pointed out that judicial review would be needed to oversee acts of Congress that may violate the Constitution.

- The Supreme Court’s Charge to Interpret the Law . Hamilton observed that the Constitution must be seen as a fundamental law, specifically stated to be the supreme law of the land. As the courts have the distinct responsibility of interpreting the law, the power of judicial review belongs with the Supreme Court.

What Cases are Eligible for Judicial Review

Although one party or another is going to be unhappy with a judgment or verdict in most court cases, not every case is eligible for appeal . In fact, there must be some legal grounds for an appeal, primarily a reversible error in the trial procedures, or the violation of Constitutional rights . Examples of reversible error include:

- Jurisdiction . The court wrongly assumes jurisdiction in a case over which another court has exclusive jurisdiction.

- Admission or Exclusion of Evidence . The court incorrectly applies rules or laws to either admit or deny the admission of certain vital evidence in the case. If such evidence proves to be a key element in the outcome of the trial, the judgment may be reversed on appeal.

- Jury Instructions . If, in giving the jury instructions on how to apply the law to a specific case, the judge has applied the wrong law, or an inaccurate interpretation of the correct law, and that error is found to have been prejudicial to the outcome of the case, the verdict may be overturned on judicial review.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Executive Privilege – The principle that the President of the United States has the right to withhold information from Congress, the courts, and the public, if it jeopardizes national security, or because disclosure of such information would be detrimental to the best interests of the Executive Branch .

- Jim Crow Laws – The legal practice of racial segregation in many states from the 1880s through the 1960s. Named after a popular black character in minstrel shows, the Jim Crow laws imposed punishments for such things as keeping company with members of another race, interracial marriage, and failure of business owners to keep white and black patrons separated.

- Judicial Decision – A decision made by a judge regarding the matter or case at hand.

- Overturn – To change a decision or judgment so that it becomes the opposite of what it was originally.

- Search Warrant – A court order that authorizes law enforcement officers or agents to search a person or a place for the purpose of obtaining evidence or contraband for use in criminal prosecution.

Meaning Therapy: An Integrative and Positive Existential Psychotherapy

- Original Paper

- Published: 25 December 2009

- Volume 40 , pages 85–93, ( 2010 )

Cite this article

- Paul T. P. Wong 1

11k Accesses

131 Citations

13 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Meaning Therapy, also known as meaning-centered counseling and therapy, is an integrative, positive existential approach to counseling and psychotherapy. Originated from logotherapy, Meaning Therapy employs personal meaning as its central organizing construct and assimilates various schools of psychotherapy to achieve its therapeutic goal. Meaning Therapy focuses on the positive psychology of making life worth living in spite of sufferings and limitations. It advocates a psycho-educational approach to equip clients with the tools to navigate the inevitable negatives in human existence and create a preferred future. The paper first introduces the defining characteristics and assumptions of Meaning Therapy. It then briefly describes the conceptual frameworks and the major intervention strategies. In view of Meaning Therapy’s open, flexible and integrative approach, it can be adopted either as a comprehensive method in its own right or as an adjunct to any system of psychotherapy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Meaning in Life as the Aim of Psychotherapy: A Hypothesis

Integrative Meaning Therapy: From Logotherapy to Existential Positive Interventions

Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy: A Socratic Clinical Practice

Adler, A. (1969). The science of living . New York: Anchor.

Google Scholar

Arthur, N., & Pedersen, P. (2008). Case incidents in counseling for international transitions . Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory . London: Routledge.

Brooks-Harris, J. E. (2008). Multitheoretical psychotherapy: Key strategies for integration practice . Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bugental, J. F. T. (1990). Intimate journeys: Stories from life-changing therapy (Revision Ed. ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bugental, J. F. T. (1999). Psychotherapy isn’t what you think: Bringing the psychotherapeutic engagement into the living moment . Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy . Oxford, England: Lyle Stuart.

Ellis, A. (1987). The practice of rational-emotive therapy . New York: Springer.

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy . New York: Pocket books.

Frankl, V. E. (1986). The doctor and the soul (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

Hayes, S. C. (2005). Get out of your mind and into your life: The new acceptance and commitment therapy . Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Hoffman, L. (2009a). Introduction to existential psychology in a cross-cultural context: An east-west dialogue. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, & A. Chan (Eds.), Existential psychology east-west (pp. 1–67). Colorado Springs, CO: University of the Rockies Press.

Hoffman, L. (2009b). Gordo’s ghost: An introduction to existential perspectives on myth. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, & A. Chan (Eds.), Existential psychology east-west (pp. 259–274). Colorado Springs, CO: University of the Rockies Press.

Hoffman, L., Yang, M., Kaklauskas, F. J., & Chan, A. (2009). Existential psychology east-west (pp. 1–67). Colorado Springs, CO: University of the Rockies Press.

Ishiyama, I. (2003). A bending willow tree: A Japanese (Morita therapy) model of human nature and client change. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 37 , 216–231.

Klinger, E. (1998). The search for meaning in evolutionary perspective and its clinical implications. In P. T. P. Wong & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning (pp. 27–50). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Maddi, S. R. (1998). Creating meaning through making decisions. In P. T. P. Wong & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning (pp. 3–26). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

May, R. (1991). The cry for myth . New York: Delta.

May, R. (1999). Existential psychotherapy. Review of Existential Psychology and Psychotherapy, 12 , 3–9.

McAdams, D. P. (2006). The person: A new introduction to personality psychology (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Mendelowitz, E. (2009). Building the Great Wall of China: Postmodern reverie and the breakdown of meanings. In L. Hoffman, M. Yang, F. J. Kaklauskas, & A. Chan (Eds.), Existential psychology east-west (pp. 327–349). Colorado Springs, CO: University of the Rockies Press.

Norcross, J. C., & Goldfried, M. R. (2005). Handbook of psychotherapy integration . New York: Oxford University Press.

Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1990). The stress appraisal measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Medicine, 6 , 227–236.

Article Google Scholar

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy . New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being . New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Sarbin, T. R. (1986). Narrative psychology: The storied nature of human conduct . Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Schneider, K. J. (2008). Existential-integrative psychotherapy: Guideposts to the core of practice . New York: Routledge.

Schneider, K. J., Bugental, J. F. T., & Pierson, J. F. (2001). The handbook of humanistic psychology . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Seligman, M. E. P., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychology. American Psychologist, 61 (8), 774–788.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Siegel, D. J. (2009). Mindful awareness, mindsight, and neural integration. The Humanistic Psychologist, 37 (2), 137–158.

Sommer, K. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). The construction of meaning from life events: Empirical studies of personal narratives. In P. T. P. Wong & P. S. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning (pp. 143–161). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Spinelli, E. (2001). The mirror and the hammer—Challenges to therapeutic orthodoxy . New York: Continuum Books.

Sue, D. W., Ivey, A. E., & Pederson, P. B. (1996). A theory of multicultural counseling & therapy . Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing.

Tomer, A., Grafton, E., & Wong, P. T. P. (Eds.). (2008). Existential & spiritual issues in death attitudes . NY: Taylor & Francis.

Van Deurzen, E. (2007). Existential counselling & psychotherapy in practice (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Weissman, M. M., Markowitz, J. C., & Klerman, G. L. (2000). Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy . New York: Basic Books.

White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice . New York: Norton.

Wong, P. T. P. (1995a). The processes of adaptive reminiscence. In B. Haight & J. D. Webster (Eds.), Reminiscence: Theory, research methods, and applications (pp. 23–35). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

Wong, P. T. P. (1995b). Coping with frustrative stress: A behavioral and cognitive analysis. In R. Wong (Ed.), Biological perspective on motivated and cognitive activities . New York: Ablex Publishing.

Wong, P. T. P. (1997). Meaning-centered counseling: A cognitive-behavioral approach to logotherapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 20 , 85–94.

Wong, P. T. P. (1998a). Meaning-centered counselling. In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 395–435). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wong, P. T. P. (1998b). Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the personal meaning profile (PMP). In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 111–140). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wong, P. T. P. (1998c). Spirituality, meaning, and successful aging. In P. T. P. Wong & P. Fry (Eds.), The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications (pp. 359–394). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wong, P. T. P. (1999). Towards an integrative model of meaning-centered counselling and therapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 22 , 47–55.

Wong, P. T. P. (2002). Logotherapy. In G. Zimmer (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychotherapy (pp. 107–113). New York: Academic Press.

Wong, P. T. P. (2006). Existential and humanistic theories. In J. C. Thomas & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of personality and psychopathology . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Wong, P. T. P. (2008). Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In A. Tomer, E. Grafton, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential & spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 65–88). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wong, P. T. P. (2009a). Positive existential psychology. In S. Lopez (Ed.), Encyclopedia of positive psychology . Oxford: Blackwell.

Wong, P. T. P. (2009b). Viktor Frankl: Prophet of hope for the 21st century. In A. Batthyany & J. Levinson (Eds.), Existential psychotherapy of meaning: Handbook of logotherapy and existential analysis . Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Tucker & Theisen.

Wong, P. T. P. (Ed.). (2009c). The human quest for meaning (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. (in press).

Wong, P. T. P., & Fry, P. S. (Eds.). (1998). The human quest for meaning: A handbook of psychological research and clinical applications . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wong, P. T. P., & McDonald, M. (2002). Tragic optimism and personal meaning in counselling victims of abuse. Pastoral Sciences, 20 (2), 231–249.

Wong, P. T. P., & Weiner, B. (1981). When people ask “Why” questions and the heuristic of attributional search. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40 , 650–663.

Wong, P. T. P., & Wong, L. C. J. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of multicultural perspectives on stress and coping . New York: Springer.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy . New York: Basic Books.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Meaning Centered Counseling Institute, 13 Ballyconnor Court, Toronto, ON, M2M 4B3, Canada

Paul T. P. Wong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paul T. P. Wong .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wong, P.T.P. Meaning Therapy: An Integrative and Positive Existential Psychotherapy. J Contemp Psychother 40 , 85–93 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

Download citation

Published : 25 December 2009

Issue Date : June 2010

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9132-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Meaning Therapy

- Psychotherapy process

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Chronic Pain

Psychotherapy and the Meaning of Life

Finding new meaning may be at the heart of change in therapy..

Posted December 3, 2020

- What Is Therapy?

- Find a therapist near me

Different psychotherapies have traditionally focused on an active collaboration between therapist and client so as to foster a reconstruction of the meaning of the client's suffering, self-narrative, and life. Meaning has always been a central axis of therapies, which are not limited to an exclusive focus on symptomatic improvement—understood as a change in apparently isolated behaviours, cognitions, or emotions—as important as that is.

The historically known importance of this dimension of searching for and attributing meaning to experience has been highlighted by research. In one of these studies, Diaz, Horton, & Malloy (2014) investigated how adult attachment style (secure vs. insecure) and two dimensions of spirituality (existential purpose/meaning of life and religious well-being or perceived relationship with God) were associated with depressive symptoms in a group of patients who were being treated for their drug addiction . The researchers found that secure attachment style and high levels of existential purpose and meaning in life were significantly related to low levels of depressive symptoms, and, thus, existential purpose and meaning in life were strong predictors of depressive symptoms. In addition, their results indicated that fostering the creative talent of the participants (for example, through creative writing or painting workshops), providing them with the opportunity to carry out tasks of service to others, and fostering connection with their core values through introspective and meditative practices helped them build that existential purpose and meaning in life that contributed to their recovery process.

Another study (Dezutter, Luyckx, & Wachholtz, 2015) showed that the presence of meaning was an important predictor of well-being and adaptation to chronic pain in a sample of 273 patients. In addition, the achievement of meaning in life has been associated with reduced levels of anxiety (Shiah, Chang, Chiang, Lin, & Tam, 2015), the maintenance of healthy habits of physical activity and eating in adolescents (Brassai, Piko, & Stege, 2015), the healthy adaptation to grief and loss (Neimeyer, 2014) and, in general, to a great variety of adaptive or reconstructive processes in human life.

In fact, meaning reconstruction could well be considered a common factor to different forms of psychotherapy , and each of them is very likely to promote it in their clients, albeit in different ways—and even "despite" the fact that some therapies do not attempt it explicitly because they don’t consider it a therapeutic factor in itself. Thus, for example, behavioral therapies promote clients' processes of meaning reconstruction through their call to action and behavioral change ( new meanings through action ); Rogerian therapy through the use of the therapeutic relationship itself given the climate of empathy, acceptance, and congruence that is created ( new meanings through compassionate reflection ); psychodynamic therapy through the therapist's interpretations and the patient's intrapsychic processes ( new meanings through insight ); the systemics through the provision of new relational experiences ( new meanings through new ways of relating ); and cognitive therapies through the identification and restructuring of problematic cognitive processes ( new meanings through new ways of thinking ).

In other words, it is perfectly acceptable that there may be different preferential access routes to the processes of meaning reconstruction. In fact, it is quite coherent; if this was not so, all human life (at least from a psychological point of view) would depend on a single dimension—be it emotional, cognitive, behavioral, or relational. It would be as if evolution had made us extremely vulnerable to invalidation by gambling everything on a single card.

Now, how does achieving an acceptable meaning for our personal problem or difficulty contribute to our coping and wellbeing? A classic study with university students may shed light on this. Wilson, Damiani, & Shelton (2002) divided 40 Duke University freshmen who were having academic achievement problems into two groups: one intervention and one control. Those in the intervention group were exposed to information that showed that it is normal for a first-year student to have some adjustment difficulties: specifically, they saw videos of students with higher grades explaining how their grades had improved as they adjusted to University. The goal was to achieve a narrative change: instead of thinking of them as failures not fit for university, the experience of their classmates encouraged them to construct their situation as temporary, and the product of a provisional imbalance that would disappear as they adapt.

The results of the intervention were surprising. Students in the intervention group scored better on a sample test almost immediately. However, the long-term results were the most impressive: students who had been led to modify their personal stories improved their grade point average, and the dropout rate among them during the following course (5%) was significantly lower than that of those who did not receive information (20%).

What changed in them? Looking strictly at the “intervention,” it was not focused on them acquiring skills or abilities, nor on understanding their difficulties in a biographical, emotional, or relational past context. It focused on giving them a different meaning, whose implications went from being catastrophic and decisive to a more hopeful future , one more open to change, a future in which they were no longer victims but protagonists.

It is very possible that in all the cases mentioned in this post ( depression , chronic pain, anxiety, self-care, grief, academic performance) the problem is not only "the problem", but the position of helplessness, emptiness, and unpredictability in which one is placed by the problem. Attributing meaning to, or making sense of, the difficulties one experiences entails locating them in an ongoing narrative, a location that makes them intelligible (without forgetting that they can be very painful) and, in a profound sense, endurable. That is perhaps the process that initiates and maintains all the other human change processes that allow us to move forward, to keep elaborating the ongoing narrative that constitutes our own life and, in the best of cases, to close a chapter and start a new one.

—Luis Botella, Ph.D., professor of psychotherapy at FPCEE Blanquerna, Ramon Llull University, Barcelona (Spain)

___________________

To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory .

Join the Convergence Special Interest Group listserv here for more information about the latest on convergence in psychotherapy.

Brassai, L., Piko, B.F. & Steger, M.F. (2011). Meaning in Life: Is It a Protective Factor for Adolescents’ Psychological Health? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 18 , 44–51, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-010-9089-6

Dezutter, J., Luyckx, K. & Wachholtz, A. (2015). Meaning in life in chronic pain patients over time: associations with pain experience and psychological well-being. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38 , 384–396 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9614-1

Diaz, N., Horton, G., & Malloy, T. (2014). Attachment Style, Spirituality, and Depressive Symptoms Among Individuals in Substance Abuse Treatment. Journal of Social Service Research, 40 :3, 313-324, DOI: 10.1080/01488376.2014.896851

Neimeyer R.A. (2015) Meaning in Bereavement. In: Anderson R. (eds) World Suffering and Quality of Life. Social Indicators Research Series, vol 56. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9670-59

Shiah, YJ., Chang, F., Chiang, SK. et al. (2015). Religion and Health: Anxiety, Religiosity, Meaning of Life and Mental Health. Journal of Religion and Health, 54 , 35–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9781-3

Wilson, T. D., Damiani, M., & Shelton, N. (2002). Improving the academic performance of college students with brief attributional interventions. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Impact of psychological factors on education (pp. 89–108). New York, NY: Academic Press.

The Special Interest Group on Convergence in Psychotherapy is a component of the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Psychotherapy: A World of Meanings

Despite a wealth of findings that psychotherapy is an effective psychological intervention, the principal mechanisms of psychotherapy change are still in debate. It has been suggested that all forms of psychotherapy provide a context which enables clients to transform the meaning of their experiences and symptoms in such a way as to help clients feel better, and function more adaptively. However, psychotherapy is not the only health care intervention that has been associated with “meaning”: the reason why placebo has effects has also been proposed to be a “meaning response.” Thus, it has been argued that the meaning of treatments has a central impact on beneficial (and by extension, negative) health-related responses. In light of the strong empirical support of a contextual understanding of psychotherapy and its effects, the aim of this conceptual analysis is to examine the role of meaning and its transformation in psychotherapy—in general—and within three different, commonly used psychotherapy modalities.

Introduction

Psychotherapy is an effective psychological intervention for a multitude of psychological, behavioral, and somatic problems, symptoms, and disorders and thus rightfully considered as a main approach in mental and somatic health care management ( Prince et al., 2007 ; Goldfried, 2013 ). But despite the wealth of empirical findings, the principal mechanisms of psychotherapy change are still in debate ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ). Two rival models have been contested ever since the very beginning of psychotherapy research, when some 80 years ago Saul Rosenzweig wondered, “whether the factors alleged to be operating in a given therapy are identical with the factors that actually are operating and whether the factors that actually are operating in several different therapies may not have much more in common than have the factors alleged to be operating.” ( Rosenzweig, 1936 , p. 412). Rosenzweig questioned the common understanding of psychotherapy, in which it is assumed that specific techniques have specific effects. This proposition was later elaborated through the work of Jerome Frank who argued that all forms of psychotherapy provide a context which enables patients to transform the meaning of their experiences and symptoms in such a way as to help them to feel better, function more favorably, and think more adaptively ( Frank, 1986 ).

Interestingly and central to this paper, psychotherapy is not the only psychological intervention which has been associated with meaning. Following the assumption that “meaning responses are always there” ( Moerman, 2006 , p. 234)—i.e., in any medical and psychological treatment—the attribution of meaning has also been considered as an overarching mechanism for those treatment effects which placebo controls for in clinical trials. Thus, the attribution of a therapeutic meaning to a given intervention has a central impact on health-related responses ( Barrett et al., 2006 ).

The contextual model of psychotherapy remains topical ( Kirsch et al., 2016 ), and also controversial ( Marcus et al., 2014 ). The model has been developed to propose that it is the “common factors” (e.g., client-therapist relationship, clients’ expectations, trust, understanding, and expertise) across different versions of psychotherapy that explain their effectiveness (for details, see Wampold et al. (2011) ). The hypothesis for the general equivalence of various forms of psychotherapies is usually referred to as the dodo bird conjecture ( Rosenzweig, 1936 ). Hence, the contextual model of psychotherapy is markedly in contrast with the long-held assumption that specific methods are at the root of psychotherapy’s effects. The assumption that psychotherapy’s effects can be reduced to incidental—or contextual—constituents, which are typically called common or unspecific factors, has been a constant in psychotherapy research ( Luborsky et al., 2002 ; Gaab et al., 2016 ) but at least in terms of empirical evidence, there is sound reason and accumulating empirical support for a contextual understanding of psychotherapy ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ). For example, a number of meta-analyses showed that various bona fide psychotherapies, i.e., therapies with a clear treatment rationale but with very different underlying theories, aims, and methods appear to be equally effective ( Spielmans et al., 2007 ; Cuijpers et al., 2008 ; Barth et al., 2013 ; Frost et al., 2014 ). In addition, opposing treatment approaches with the same treatment rationale have shown to be equally effective in a trial on clients with panic disorder ( Kim et al., 2012 ) as much as similar treatments provided with opposing treatment rationales have shown to differ in their effects ( Tondorf et al., 2017 ).

Building on the strong empirical support for a contextual understanding of psychotherapy ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ), which proposes the transformation of meaning as its central mechanisms, the aim of this conceptual analysis is to examine the role of meaning and its transformation in psychotherapy in general and in three different and commonly used psychotherapy approaches.

In Search of a New Meaning

The main incentive to undergo a psychotherapy treatment is to change the general level of functioning, as well as to reduce the symptoms of suffering ( Strong and Matross, 1973 ). Clients’ belief that they are unable or incapable of solving disturbing problems contributes to demoralization and feelings of confusion, despair, and incompetence ( Vissers et al., 2010 ) or as Frank (1986) put it: “Often an important feature of demoralization is a sense of confusion resulting from the client’s inability to make sense out of his experiences or to control them, leading to the commonly expressed fear of going insane” (p. 341). This demoralization is not only a shared aspect of various psychological disorders, but can also be considered as a starting point for change in psychotherapy. Therapeutic change is thereby accompanied by clients “working through” their problems, gaining insight, achieving personal fulfillment, and becoming self-actualized, eventually transforming their problems and symptoms, self-perception, and experiences with their social environment ( Evans, 2013 ; Krause et al., 2015 ).

Frank (1986) stated that psychotherapy seeks to help clients to transform the meanings of their problems and symptoms and to overcome confusion with newly acquired clarity, i.e., by offering a narrative that links symptoms with hypothesized causes and providing a collaborative procedure for overcoming the suffering. Likewise, Wampold (2007) defined the core of psychotherapy in the transformation of non-adaptive explanations for their problems into new and more adaptive ones. Also, Dan Moerman ( Moerman, 2002 ) stated that “it sounds reasonable to me to say that psychotherapy evokes meaning responses” (p. 94) and that psychotherapy supports clients to create their stories and myths, although therapists are not considered a mandatory requirement for this ( Moerman, 2002 ). It should be noted that other mechanisms underlying positive response to psychotherapy have been proposed, e.g., reward mechanisms in psychotherapy ( Northoff and Boeker, 2006 ; Panksepp and Solms, 2012 ).

Considering processes of change in diverse interventions, narratives are thought to be created in order to render the demoralization less painful and promote remoralization ( Moerman, 2002 ). In this perspective, the therapists help their clients to give new meanings to their experiences or stories they tell, the language they use, and the beliefs they have ( Shaw, 2010 ).

Similar processes have been proposed to underlie placebo responses, which are “most likely to occur when the meaning of the illness experience is altered in a positive direction” ( Brody, 2000 ). These beneficial changes in meaning occur when three core conditions are present, which again resemble those proposed in the context of psychotherapy: (1) the clients feel listened to and receive a satisfactory, coherent explanation of their mental suffering and demoralization; (2) the client feels care and concern from the therapist; and (3) the clients feel an enhanced sense of mastery and control over their mental suffering (i.e., remoralization). A direct implementation can be seen in so-called narrative therapies, which are defined as “an approach that focuses on client stories with the goal of challenging existing meaning systems and creating more functional ones” ( Kropf and Tandy, 1998 ). Narrative approaches have come to a central role in systemic family therapy ( Carr, 1998 ; Wallis et al., 2011 ), emphasizing the role of language and how it affects the way clients frame their ideas of self and identity, while the therapist directly deals with clients’ concerns and the meaning of the worlds they live in ( Besley, 2002 ). Furthermore, it has been assumed that relying on the clients’ individual narratives is more significant than focusing on a pathological psychiatric diagnosis ( Gysin-Maillart et al., 2016 ). Of course, narrative therapies should not be mistaken as the exception of (dodo) rule, i.e., to be instances of “specific” therapies, but rather as possibilities to operationalize the rule in real life, i.e., to employ meaning processes in psychotherapy. Accordingly, it has been shown that meaning-making through language enhances clients’ well-being after a traumatic experience—which mainly stems from the connection, abstraction, and reflection of the whole experience ( Freda and Martino, 2015 ; Park et al., 2016 ).

Co-Construction of Narratives