Get Started

Take the first step and invest in your future.

Online Programs

Offering flexibility & convenience in 51 online degrees & programs.

Prairie Stars

Featuring 15 intercollegiate NCAA Div II athletic teams.

Find your Fit

UIS has over 85 student and 10 greek life organizations, and many volunteer opportunities.

Arts & Culture

Celebrating the arts to create rich cultural experiences on campus.

Give Like a Star

Your generosity helps fuel fundraising for scholarships, programs and new initiatives.

Bragging Rights

UIS was listed No. 1 in Illinois and No. 3 in the Midwest in 2023 rankings.

- Quick links Applicants & Students Important Apps & Links Alumni Faculty and Staff Community Admissions How to Apply Cost & Aid Tuition Calculator Registrar Orientation Visit Campus Academics Register for Class Programs of Study Online Degrees & Programs Graduate Education International Student Services Study Away Student Support Bookstore UIS Life Dining Diversity & Inclusion Get Involved Health & Wellness COVID-19 United in Safety Residence Life Student Life Programs UIS Connection Important Apps UIS Mobile App Advise U Canvas myUIS i-card Balance Pay My Bill - UIS Bursar Self-Service Email Resources Bookstore Box Information Technology Services Library Orbit Policies Webtools Get Connected Area Information Calendar Campus Recreation Departments & Programs (A-Z) Parking UIS Newsroom Connect & Get Involved Update your Info Alumni Events Alumni Networks & Groups Volunteer Opportunities Alumni Board News & Publications Featured Alumni Alumni News UIS Alumni Magazine Resources Order your Transcripts Give Back Alumni Programs Career Development Services & Support Accessibility Services Campus Services Campus Police Facilities & Services Registrar Faculty & Staff Resources Website Project Request Web Services Training & Tools Academic Impressions Career Connect CSA Reporting Cybersecurity Training Faculty Research FERPA Training Website Login Campus Resources Newsroom Campus Calendar Campus Maps i-Card Human Resources Public Relations Webtools Arts & Events UIS Performing Arts Center Visual Arts Gallery Event Calendar Sangamon Experience Center for Lincoln Studies ECCE Speaker Series Community Engagement Center for State Policy and Leadership Illinois Innocence Project Innovate Springfield Central IL Nonprofit Resource Center NPR Illinois Community Resources Child Protection Training Academy Office of Electronic Media University Archives/IRAD Institute for Illinois Public Finance

Request Info

How to Review a Journal Article

- Request Info Request info for.... Undergraduate/Graduate Online Study Away Continuing & Professional Education International Student Services General Inquiries

For many kinds of assignments, like a literature review , you may be asked to offer a critique or review of a journal article. This is an opportunity for you as a scholar to offer your qualified opinion and evaluation of how another scholar has composed their article, argument, and research. That means you will be expected to go beyond a simple summary of the article and evaluate it on a deeper level. As a college student, this might sound intimidating. However, as you engage with the research process, you are becoming immersed in a particular topic, and your insights about the way that topic is presented are valuable and can contribute to the overall conversation surrounding your topic.

IMPORTANT NOTE!!

Some disciplines, like Criminal Justice, may only want you to summarize the article without including your opinion or evaluation. If your assignment is to summarize the article only, please see our literature review handout.

Before getting started on the critique, it is important to review the article thoroughly and critically. To do this, we recommend take notes, annotating , and reading the article several times before critiquing. As you read, be sure to note important items like the thesis, purpose, research questions, hypotheses, methods, evidence, key findings, major conclusions, tone, and publication information. Depending on your writing context, some of these items may not be applicable.

Questions to Consider

To evaluate a source, consider some of the following questions. They are broken down into different categories, but answering these questions will help you consider what areas to examine. With each category, we recommend identifying the strengths and weaknesses in each since that is a critical part of evaluation.

Evaluating Purpose and Argument

- How well is the purpose made clear in the introduction through background/context and thesis?

- How well does the abstract represent and summarize the article’s major points and argument?

- How well does the objective of the experiment or of the observation fill a need for the field?

- How well is the argument/purpose articulated and discussed throughout the body of the text?

- How well does the discussion maintain cohesion?

Evaluating the Presentation/Organization of Information

- How appropriate and clear is the title of the article?

- Where could the author have benefited from expanding, condensing, or omitting ideas?

- How clear are the author’s statements? Challenge ambiguous statements.

- What underlying assumptions does the author have, and how does this affect the credibility or clarity of their article?

- How objective is the author in his or her discussion of the topic?

- How well does the organization fit the article’s purpose and articulate key goals?

Evaluating Methods

- How appropriate are the study design and methods for the purposes of the study?

- How detailed are the methods being described? Is the author leaving out important steps or considerations?

- Have the procedures been presented in enough detail to enable the reader to duplicate them?

Evaluating Data

- Scan and spot-check calculations. Are the statistical methods appropriate?

- Do you find any content repeated or duplicated?

- How many errors of fact and interpretation does the author include? (You can check on this by looking up the references the author cites).

- What pertinent literature has the author cited, and have they used this literature appropriately?

Following, we have an example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. Note that in most literature review contexts, the summary and evaluation would be much shorter. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article.

Chik, A. (2012). Digital gameplay for autonomous foreign language learning: Gamers’ and language teachers’ perspectives. In H. Reinders (ed.), Digital games in language learning and teaching (pp. 95-114). Eastbourne, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Be sure to include the full citation either in a reference page or near your evaluation if writing an annotated bibliography .

In Chik’s article “Digital Gameplay for Autonomous Foreign Language Learning: Gamers’ and Teachers’ Perspectives”, she explores the ways in which “digital gamers manage gaming and gaming-related activities to assume autonomy in their foreign language learning,” (96) which is presented in contrast to how teachers view the “pedagogical potential” of gaming. The research was described as an “umbrella project” consisting of two parts. The first part examined 34 language teachers’ perspectives who had limited experience with gaming (only five stated they played games regularly) (99). Their data was recorded through a survey, class discussion, and a seven-day gaming trial done by six teachers who recorded their reflections through personal blog posts. The second part explored undergraduate gaming habits of ten Hong Kong students who were regular gamers. Their habits were recorded through language learning histories, videotaped gaming sessions, blog entries of gaming practices, group discussion sessions, stimulated recall sessions on gaming videos, interviews with other gamers, and posts from online discussion forums. The research shows that while students recognize the educational potential of games and have seen benefits of it in their lives, the instructors overall do not see the positive impacts of gaming on foreign language learning.

The summary includes the article’s purpose, methods, results, discussion, and citations when necessary.

This article did a good job representing the undergraduate gamers’ voices through extended quotes and stories. Particularly for the data collection of the undergraduate gamers, there were many opportunities for an in-depth examination of their gaming practices and histories. However, the representation of the teachers in this study was very uneven when compared to the students. Not only were teachers labeled as numbers while the students picked out their own pseudonyms, but also when viewing the data collection, the undergraduate students were more closely examined in comparison to the teachers in the study. While the students have fifteen extended quotes describing their experiences in their research section, the teachers only have two of these instances in their section, which shows just how imbalanced the study is when presenting instructor voices.

Some research methods, like the recorded gaming sessions, were only used with students whereas teachers were only asked to blog about their gaming experiences. This creates a richer narrative for the students while also failing to give instructors the chance to have more nuanced perspectives. This lack of nuance also stems from the emphasis of the non-gamer teachers over the gamer teachers. The non-gamer teachers’ perspectives provide a stark contrast to the undergraduate gamer experiences and fits neatly with the narrative of teachers not valuing gaming as an educational tool. However, the study mentioned five teachers that were regular gamers whose perspectives are left to a short section at the end of the presentation of the teachers’ results. This was an opportunity to give the teacher group a more complex story, and the opportunity was entirely missed.

Additionally, the context of this study was not entirely clear. The instructors were recruited through a master’s level course, but the content of the course and the institution’s background is not discussed. Understanding this context helps us understand the course’s purpose(s) and how those purposes may have influenced the ways in which these teachers interpreted and saw games. It was also unclear how Chik was connected to this masters’ class and to the students. Why these particular teachers and students were recruited was not explicitly defined and also has the potential to skew results in a particular direction.

Overall, I was inclined to agree with the idea that students can benefit from language acquisition through gaming while instructors may not see the instructional value, but I believe the way the research was conducted and portrayed in this article made it very difficult to support Chik’s specific findings.

Some professors like you to begin an evaluation with something positive but isn’t always necessary.

The evaluation is clearly organized and uses transitional phrases when moving to a new topic.

This evaluation includes a summative statement that gives the overall impression of the article at the end, but this can also be placed at the beginning of the evaluation.

This evaluation mainly discusses the representation of data and methods. However, other areas, like organization, are open to critique.

Page Content

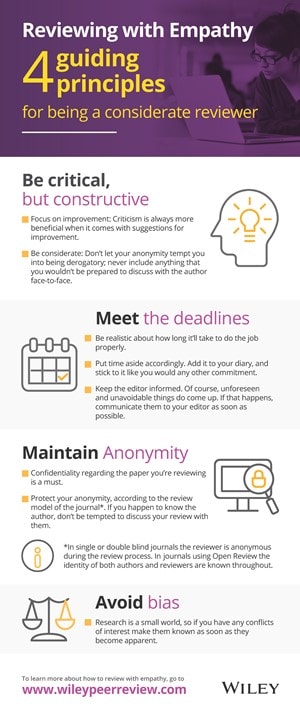

Overview of the review report format, the first read-through, first read considerations, spotting potential major flaws, concluding the first reading, rejection after the first reading, before starting the second read-through, doing the second read-through, the second read-through: section by section guidance, how to structure your report, on presentation and style, criticisms & confidential comments to editors, the recommendation, when recommending rejection, additional resources, step by step guide to reviewing a manuscript.

When you receive an invitation to peer review, you should be sent a copy of the paper's abstract to help you decide whether you wish to do the review. Try to respond to invitations promptly - it will prevent delays. It is also important at this stage to declare any potential Conflict of Interest.

The structure of the review report varies between journals. Some follow an informal structure, while others have a more formal approach.

" Number your comments!!! " (Jonathon Halbesleben, former Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Informal Structure

Many journals don't provide criteria for reviews beyond asking for your 'analysis of merits'. In this case, you may wish to familiarize yourself with examples of other reviews done for the journal, which the editor should be able to provide or, as you gain experience, rely on your own evolving style.

Formal Structure

Other journals require a more formal approach. Sometimes they will ask you to address specific questions in your review via a questionnaire. Or they might want you to rate the manuscript on various attributes using a scorecard. Often you can't see these until you log in to submit your review. So when you agree to the work, it's worth checking for any journal-specific guidelines and requirements. If there are formal guidelines, let them direct the structure of your review.

In Both Cases

Whether specifically required by the reporting format or not, you should expect to compile comments to authors and possibly confidential ones to editors only.

Following the invitation to review, when you'll have received the article abstract, you should already understand the aims, key data and conclusions of the manuscript. If you don't, make a note now that you need to feedback on how to improve those sections.

The first read-through is a skim-read. It will help you form an initial impression of the paper and get a sense of whether your eventual recommendation will be to accept or reject the paper.

Keep a pen and paper handy when skim-reading.

Try to bear in mind the following questions - they'll help you form your overall impression:

- What is the main question addressed by the research? Is it relevant and interesting?

- How original is the topic? What does it add to the subject area compared with other published material?

- Is the paper well written? Is the text clear and easy to read?

- Are the conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented? Do they address the main question posed?

- If the author is disagreeing significantly with the current academic consensus, do they have a substantial case? If not, what would be required to make their case credible?

- If the paper includes tables or figures, what do they add to the paper? Do they aid understanding or are they superfluous?

While you should read the whole paper, making the right choice of what to read first can save time by flagging major problems early on.

Editors say, " Specific recommendations for remedying flaws are VERY welcome ."

Examples of possibly major flaws include:

- Drawing a conclusion that is contradicted by the author's own statistical or qualitative evidence

- The use of a discredited method

- Ignoring a process that is known to have a strong influence on the area under study

If experimental design features prominently in the paper, first check that the methodology is sound - if not, this is likely to be a major flaw.

You might examine:

- The sampling in analytical papers

- The sufficient use of control experiments

- The precision of process data

- The regularity of sampling in time-dependent studies

- The validity of questions, the use of a detailed methodology and the data analysis being done systematically (in qualitative research)

- That qualitative research extends beyond the author's opinions, with sufficient descriptive elements and appropriate quotes from interviews or focus groups

Major Flaws in Information

If methodology is less of an issue, it's often a good idea to look at the data tables, figures or images first. Especially in science research, it's all about the information gathered. If there are critical flaws in this, it's very likely the manuscript will need to be rejected. Such issues include:

- Insufficient data

- Unclear data tables

- Contradictory data that either are not self-consistent or disagree with the conclusions

- Confirmatory data that adds little, if anything, to current understanding - unless strong arguments for such repetition are made

If you find a major problem, note your reasoning and clear supporting evidence (including citations).

After the initial read and using your notes, including those of any major flaws you found, draft the first two paragraphs of your review - the first summarizing the research question addressed and the second the contribution of the work. If the journal has a prescribed reporting format, this draft will still help you compose your thoughts.

The First Paragraph

This should state the main question addressed by the research and summarize the goals, approaches, and conclusions of the paper. It should:

- Help the editor properly contextualize the research and add weight to your judgement

- Show the author what key messages are conveyed to the reader, so they can be sure they are achieving what they set out to do

- Focus on successful aspects of the paper so the author gets a sense of what they've done well

The Second Paragraph

This should provide a conceptual overview of the contribution of the research. So consider:

- Is the paper's premise interesting and important?

- Are the methods used appropriate?

- Do the data support the conclusions?

After drafting these two paragraphs, you should be in a position to decide whether this manuscript is seriously flawed and should be rejected (see the next section). Or whether it is publishable in principle and merits a detailed, careful read through.

Even if you are coming to the opinion that an article has serious flaws, make sure you read the whole paper. This is very important because you may find some really positive aspects that can be communicated to the author. This could help them with future submissions.

A full read-through will also make sure that any initial concerns are indeed correct and fair. After all, you need the context of the whole paper before deciding to reject. If you still intend to recommend rejection, see the section "When recommending rejection."

Once the paper has passed your first read and you've decided the article is publishable in principle, one purpose of the second, detailed read-through is to help prepare the manuscript for publication. You may still decide to recommend rejection following a second reading.

" Offer clear suggestions for how the authors can address the concerns raised. In other words, if you're going to raise a problem, provide a solution ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Preparation

To save time and simplify the review:

- Don't rely solely upon inserting comments on the manuscript document - make separate notes

- Try to group similar concerns or praise together

- If using a review program to note directly onto the manuscript, still try grouping the concerns and praise in separate notes - it helps later

- Note line numbers of text upon which your notes are based - this helps you find items again and also aids those reading your review

Now that you have completed your preparations, you're ready to spend an hour or so reading carefully through the manuscript.

As you're reading through the manuscript for a second time, you'll need to keep in mind the argument's construction, the clarity of the language and content.

With regard to the argument’s construction, you should identify:

- Any places where the meaning is unclear or ambiguous

- Any factual errors

- Any invalid arguments

You may also wish to consider:

- Does the title properly reflect the subject of the paper?

- Does the abstract provide an accessible summary of the paper?

- Do the keywords accurately reflect the content?

- Is the paper an appropriate length?

- Are the key messages short, accurate and clear?

Not every submission is well written. Part of your role is to make sure that the text’s meaning is clear.

Editors say, " If a manuscript has many English language and editing issues, please do not try and fix it. If it is too bad, note that in your review and it should be up to the authors to have the manuscript edited ."

If the article is difficult to understand, you should have rejected it already. However, if the language is poor but you understand the core message, see if you can suggest improvements to fix the problem:

- Are there certain aspects that could be communicated better, such as parts of the discussion?

- Should the authors consider resubmitting to the same journal after language improvements?

- Would you consider looking at the paper again once these issues are dealt with?

On Grammar and Punctuation

Your primary role is judging the research content. Don't spend time polishing grammar or spelling. Editors will make sure that the text is at a high standard before publication. However, if you spot grammatical errors that affect clarity of meaning, then it's important to highlight these. Expect to suggest such amendments - it's rare for a manuscript to pass review with no corrections.

A 2010 study of nursing journals found that 79% of recommendations by reviewers were influenced by grammar and writing style (Shattel, et al., 2010).

1. The Introduction

A well-written introduction:

- Sets out the argument

- Summarizes recent research related to the topic

- Highlights gaps in current understanding or conflicts in current knowledge

- Establishes the originality of the research aims by demonstrating the need for investigations in the topic area

- Gives a clear idea of the target readership, why the research was carried out and the novelty and topicality of the manuscript

Originality and Topicality

Originality and topicality can only be established in the light of recent authoritative research. For example, it's impossible to argue that there is a conflict in current understanding by referencing articles that are 10 years old.

Authors may make the case that a topic hasn't been investigated in several years and that new research is required. This point is only valid if researchers can point to recent developments in data gathering techniques or to research in indirectly related fields that suggest the topic needs revisiting. Clearly, authors can only do this by referencing recent literature. Obviously, where older research is seminal or where aspects of the methodology rely upon it, then it is perfectly appropriate for authors to cite some older papers.

Editors say, "Is the report providing new information; is it novel or just confirmatory of well-known outcomes ?"

It's common for the introduction to end by stating the research aims. By this point you should already have a good impression of them - if the explicit aims come as a surprise, then the introduction needs improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

Academic research should be replicable, repeatable and robust - and follow best practice.

Replicable Research

This makes sufficient use of:

- Control experiments

- Repeated analyses

- Repeated experiments

These are used to make sure observed trends are not due to chance and that the same experiment could be repeated by other researchers - and result in the same outcome. Statistical analyses will not be sound if methods are not replicable. Where research is not replicable, the paper should be recommended for rejection.

Repeatable Methods

These give enough detail so that other researchers are able to carry out the same research. For example, equipment used or sampling methods should all be described in detail so that others could follow the same steps. Where methods are not detailed enough, it's usual to ask for the methods section to be revised.

Robust Research

This has enough data points to make sure the data are reliable. If there are insufficient data, it might be appropriate to recommend revision. You should also consider whether there is any in-built bias not nullified by the control experiments.

Best Practice

During these checks you should keep in mind best practice:

- Standard guidelines were followed (e.g. the CONSORT Statement for reporting randomized trials)

- The health and safety of all participants in the study was not compromised

- Ethical standards were maintained

If the research fails to reach relevant best practice standards, it's usual to recommend rejection. What's more, you don't then need to read any further.

3. Results and Discussion

This section should tell a coherent story - What happened? What was discovered or confirmed?

Certain patterns of good reporting need to be followed by the author:

- They should start by describing in simple terms what the data show

- They should make reference to statistical analyses, such as significance or goodness of fit

- Once described, they should evaluate the trends observed and explain the significance of the results to wider understanding. This can only be done by referencing published research

- The outcome should be a critical analysis of the data collected

Discussion should always, at some point, gather all the information together into a single whole. Authors should describe and discuss the overall story formed. If there are gaps or inconsistencies in the story, they should address these and suggest ways future research might confirm the findings or take the research forward.

4. Conclusions

This section is usually no more than a few paragraphs and may be presented as part of the results and discussion, or in a separate section. The conclusions should reflect upon the aims - whether they were achieved or not - and, just like the aims, should not be surprising. If the conclusions are not evidence-based, it's appropriate to ask for them to be re-written.

5. Information Gathered: Images, Graphs and Data Tables

If you find yourself looking at a piece of information from which you cannot discern a story, then you should ask for improvements in presentation. This could be an issue with titles, labels, statistical notation or image quality.

Where information is clear, you should check that:

- The results seem plausible, in case there is an error in data gathering

- The trends you can see support the paper's discussion and conclusions

- There are sufficient data. For example, in studies carried out over time are there sufficient data points to support the trends described by the author?

You should also check whether images have been edited or manipulated to emphasize the story they tell. This may be appropriate but only if authors report on how the image has been edited (e.g. by highlighting certain parts of an image). Where you feel that an image has been edited or manipulated without explanation, you should highlight this in a confidential comment to the editor in your report.

6. List of References

You will need to check referencing for accuracy, adequacy and balance.

Where a cited article is central to the author's argument, you should check the accuracy and format of the reference - and bear in mind different subject areas may use citations differently. Otherwise, it's the editor’s role to exhaustively check the reference section for accuracy and format.

You should consider if the referencing is adequate:

- Are important parts of the argument poorly supported?

- Are there published studies that show similar or dissimilar trends that should be discussed?

- If a manuscript only uses half the citations typical in its field, this may be an indicator that referencing should be improved - but don't be guided solely by quantity

- References should be relevant, recent and readily retrievable

Check for a well-balanced list of references that is:

- Helpful to the reader

- Fair to competing authors

- Not over-reliant on self-citation

- Gives due recognition to the initial discoveries and related work that led to the work under assessment

You should be able to evaluate whether the article meets the criteria for balanced referencing without looking up every reference.

7. Plagiarism

By now you will have a deep understanding of the paper's content - and you may have some concerns about plagiarism.

Identified Concern

If you find - or already knew of - a very similar paper, this may be because the author overlooked it in their own literature search. Or it may be because it is very recent or published in a journal slightly outside their usual field.

You may feel you can advise the author how to emphasize the novel aspects of their own study, so as to better differentiate it from similar research. If so, you may ask the author to discuss their aims and results, or modify their conclusions, in light of the similar article. Of course, the research similarities may be so great that they render the work unoriginal and you have no choice but to recommend rejection.

"It's very helpful when a reviewer can point out recent similar publications on the same topic by other groups, or that the authors have already published some data elsewhere ." (Editor feedback)

Suspected Concern

If you suspect plagiarism, including self-plagiarism, but cannot recall or locate exactly what is being plagiarized, notify the editor of your suspicion and ask for guidance.

Most editors have access to software that can check for plagiarism.

Editors are not out to police every paper, but when plagiarism is discovered during peer review it can be properly addressed ahead of publication. If plagiarism is discovered only after publication, the consequences are worse for both authors and readers, because a retraction may be necessary.

For detailed guidelines see COPE's Ethical guidelines for reviewers and Wiley's Best Practice Guidelines on Publishing Ethics .

8. Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

After the detailed read-through, you will be in a position to advise whether the title, abstract and key words are optimized for search purposes. In order to be effective, good SEO terms will reflect the aims of the research.

A clear title and abstract will improve the paper's search engine rankings and will influence whether the user finds and then decides to navigate to the main article. The title should contain the relevant SEO terms early on. This has a major effect on the impact of a paper, since it helps it appear in search results. A poor abstract can then lose the reader's interest and undo the benefit of an effective title - whilst the paper's abstract may appear in search results, the potential reader may go no further.

So ask yourself, while the abstract may have seemed adequate during earlier checks, does it:

- Do justice to the manuscript in this context?

- Highlight important findings sufficiently?

- Present the most interesting data?

Editors say, " Does the Abstract highlight the important findings of the study ?"

If there is a formal report format, remember to follow it. This will often comprise a range of questions followed by comment sections. Try to answer all the questions. They are there because the editor felt that they are important. If you're following an informal report format you could structure your report in three sections: summary, major issues, minor issues.

- Give positive feedback first. Authors are more likely to read your review if you do so. But don't overdo it if you will be recommending rejection

- Briefly summarize what the paper is about and what the findings are

- Try to put the findings of the paper into the context of the existing literature and current knowledge

- Indicate the significance of the work and if it is novel or mainly confirmatory

- Indicate the work's strengths, its quality and completeness

- State any major flaws or weaknesses and note any special considerations. For example, if previously held theories are being overlooked

Major Issues

- Are there any major flaws? State what they are and what the severity of their impact is on the paper

- Has similar work already been published without the authors acknowledging this?

- Are the authors presenting findings that challenge current thinking? Is the evidence they present strong enough to prove their case? Have they cited all the relevant work that would contradict their thinking and addressed it appropriately?

- If major revisions are required, try to indicate clearly what they are

- Are there any major presentational problems? Are figures & tables, language and manuscript structure all clear enough for you to accurately assess the work?

- Are there any ethical issues? If you are unsure it may be better to disclose these in the confidential comments section

Minor Issues

- Are there places where meaning is ambiguous? How can this be corrected?

- Are the correct references cited? If not, which should be cited instead/also? Are citations excessive, limited, or biased?

- Are there any factual, numerical or unit errors? If so, what are they?

- Are all tables and figures appropriate, sufficient, and correctly labelled? If not, say which are not

Your review should ultimately help the author improve their article. So be polite, honest and clear. You should also try to be objective and constructive, not subjective and destructive.

You should also:

- Write clearly and so you can be understood by people whose first language is not English

- Avoid complex or unusual words, especially ones that would even confuse native speakers

- Number your points and refer to page and line numbers in the manuscript when making specific comments

- If you have been asked to only comment on specific parts or aspects of the manuscript, you should indicate clearly which these are

- Treat the author's work the way you would like your own to be treated

Most journals give reviewers the option to provide some confidential comments to editors. Often this is where editors will want reviewers to state their recommendation - see the next section - but otherwise this area is best reserved for communicating malpractice such as suspected plagiarism, fraud, unattributed work, unethical procedures, duplicate publication, bias or other conflicts of interest.

However, this doesn't give reviewers permission to 'backstab' the author. Authors can't see this feedback and are unable to give their side of the story unless the editor asks them to. So in the spirit of fairness, write comments to editors as though authors might read them too.

Reviewers should check the preferences of individual journals as to where they want review decisions to be stated. In particular, bear in mind that some journals will not want the recommendation included in any comments to authors, as this can cause editors difficulty later - see Section 11 for more advice about working with editors.

You will normally be asked to indicate your recommendation (e.g. accept, reject, revise and resubmit, etc.) from a fixed-choice list and then to enter your comments into a separate text box.

Recommending Acceptance

If you're recommending acceptance, give details outlining why, and if there are any areas that could be improved. Don't just give a short, cursory remark such as 'great, accept'. See Improving the Manuscript

Recommending Revision

Where improvements are needed, a recommendation for major or minor revision is typical. You may also choose to state whether you opt in or out of the post-revision review too. If recommending revision, state specific changes you feel need to be made. The author can then reply to each point in turn.

Some journals offer the option to recommend rejection with the possibility of resubmission – this is most relevant where substantial, major revision is necessary.

What can reviewers do to help? " Be clear in their comments to the author (or editor) which points are absolutely critical if the paper is given an opportunity for revisio n." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Recommending Rejection

If recommending rejection or major revision, state this clearly in your review (and see the next section, 'When recommending rejection').

Where manuscripts have serious flaws you should not spend any time polishing the review you've drafted or give detailed advice on presentation.

Editors say, " If a reviewer suggests a rejection, but her/his comments are not detailed or helpful, it does not help the editor in making a decision ."

In your recommendations for the author, you should:

- Give constructive feedback describing ways that they could improve the research

- Keep the focus on the research and not the author. This is an extremely important part of your job as a reviewer

- Avoid making critical confidential comments to the editor while being polite and encouraging to the author - the latter may not understand why their manuscript has been rejected. Also, they won't get feedback on how to improve their research and it could trigger an appeal

Remember to give constructive criticism even if recommending rejection. This helps developing researchers improve their work and explains to the editor why you felt the manuscript should not be published.

" When the comments seem really positive, but the recommendation is rejection…it puts the editor in a tough position of having to reject a paper when the comments make it sound like a great paper ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Visit our Wiley Author Learning and Training Channel for expert advice on peer review.

Watch the video, Ethical considerations of Peer Review

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Review & Evaluate a Journal Publication

Last Updated: January 8, 2024 Fact Checked

Active Reading

Critical evaluation, final review.

This article was co-authored by Richard Perkins . Richard Perkins is a Writing Coach, Academic English Coordinator, and the Founder of PLC Learning Center. With over 24 years of education experience, he gives teachers tools to teach writing to students and works with elementary to university level students to become proficient, confident writers. Richard is a fellow at the National Writing Project. As a teacher leader and consultant at California State University Long Beach's Global Education Project, Mr. Perkins creates and presents teacher workshops that integrate the U.N.'s 17 Sustainable Development Goals in the K-12 curriculum. He holds a BA in Communications and TV from The University of Southern California and an MEd from California State University Dominguez Hills. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 149,390 times.

Whether you’re publishing a journal article review or completing one for a class, your critique should be fair, thorough, and constructive. Don't worry—this article will walk you through exactly how to review a journal article step-by-step. Keep reading for tips on how to analyze the article, assess how successful it is, and put your thoughts into words.

- Familiarizing yourself with format and style guidelines is especially important if you haven’t published with that journal in the past. For example, a journal might require you to recommend an article for publication, meet a certain word count, or provide revisions that the authors should make.

- If you’re reviewing a journal article for a school assignment, familiarize yourself the guidelines your instructor provided.

- While giving the article a closer read, gauge whether and how well the article resolves its central problem. Ask yourself, “Is this investigation important, and does it uniquely contribute to its field?”

- At this stage, note any terminological inconsistencies, organizational problems, typos, and formatting issues.

- How well does the abstract summarize the article, the problem it addresses, its techniques, results, and significance? For example, you might find that an abstract describes a pharmaceutical study's topic and skips to results without discussing the experiment's methods with much detail.

- Does the introduction map out the article’s structure? Does it clearly lay out the groundwork? A good introduction gives you a clear idea of what to expect in the coming sections. It might state the problem and hypothesis, briefly describe the investigation's methods, then state whether the experiment proved or disproved the hypothesis.

- If necessary, spend some time perusing copies of the article’s sources so you can better understand the topic’s existing literature.

- A good literature review will say something like, "Smith and Jones, in their authoritative 2015 study, demonstrated that adult men and women responded favorably to the treatment. However, no research on the topic has examined the technique's effects and safety in children and adolescents, which is what we sought to explore in our current work."

- For example, you might observe that subjects in medical study didn’t accurately represent a diverse population.

- For example, you might find that tables list too much undigested data that the authors don’t adequately summarize within the text.

- For example, if you’re reviewing an art history article, decide whether it analyzes an artwork reasonably or simply leaps to conclusions. A reasonable analysis might argue, “The artist was a member of Rembrandt’s workshop, which is evident in the painting’s dramatic light and sensual texture.”

- Is the language clear and unambiguous, or does excessive jargon interfere with its ability to make an argument?

- Are there places that are too wordy? Can any ideas be stated in a simpler way?

- Are grammar, punctuation, and terminology correct?

- Your thesis and evidence should be constructive and thoughtful. Point out both strengths and weaknesses, and propose alternative solutions instead of focusing only on weaknesses.

- A good, constructive thesis would be, “The article demonstrates that the drug works better than a placebo in specific demographics, but future research that includes a more diverse subject sampling is necessary.”

- The introduction summarizes the article and states your thesis.

- The body provides specific examples from the text that support your thesis.

- The conclusion summarizes your review, restates your thesis, and offers suggestion for future research.

- Make sure your writing is clear, concise, and logical. If you mention that an article is too verbose, your own writing shouldn’t be full of unnecessarily complicated terms and sentences.

- If possible, have someone familiar with the topic read your draft and offer feedback.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.science.org/content/article/how-review-paper

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ http://library.queensu.ca/inforef/criticalreview.htm

About This Article

If you want to review a journal article, you’ll need to carefully read it through and come up with a thesis for your piece. Read the article once to get a general idea of what it says, then read it through again and make detailed notes. You should focus on things like whether the introduction gives a good overview of the topic, whether the writing is concise, and whether the results are presented clearly. When you write your review, present both strengths and weaknesses of the article so you’re giving a balanced assessment. Back up your points with examples in the main body of your review, which will make it more credible. You should also ensure your thesis about the article is clear by mentioning it in the introduction and restating it in the conclusion of your review. For tips on how to edit your review before publication, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jun 30, 2019

Did this article help you?

Laura Drawls

Aug 26, 2017

Oct 29, 2019

Sep 27, 2018

Sarah Corduroy

Dec 5, 2022

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

How to review articles.

Become a reviewer | Things to consider | What to include | Your recommendation | Webinar | Web of Science Academy

Peer review is essential for filtering out poor quality articles by assessing the validity and integrity of the research. We value the work done by peer reviewers in the academic community, who facilitate the process of publication and drive research within their fields of expertise. Please visit the Reviewer Rewards page to learn more about discounts and free journal access offered to reviewers of articles for Sage journals.

If you are an inexperienced or first-time reviewer, the peer review process may seem daunting. In fact, peer review can be a very rewarding process that allows you to contribute to the development of your field and hone your own research and writing skills. The resources below will explain what peer review involves and help you to write useful reviews.

How to become a reviewer

There are three ways to register as a reviewer.

1. Create a journal-specific reviewer account on Sage Track. Search for the journal’s name here and then click the ‘Submit paper’ link. This will take you to the peer review system where you can create an account.

Why create an account on a specific journal Sage Track site?

- You will be part of the journal’s reviewer database.

- You can make your profile more attractive by adding keywords related to your areas of expertise to boost your chances of being invited to review.

- Editors can rate your reviews which may increase your chances of being invited to review again.

2. Contact the journal editor or editorial office directly. In your communication, express your interest, summarize your expertise, and present yourself as a valuable reviewer.

Why contact the editor or editorial office directly?

- If you’re unsure if your area of expertise fits the journal's scope you can double-check with the editor or editorial office directly before registering your details on the Web of Science or the journal’s Sage Track site.

- Editors get a firsthand look at your experience and expertise.

- This is an opportunity for you to introduce yourself and your interests to the editor to increase your chances of being invited to review.

3. Sign up to the Web of Science Reviewer Recognition Service . Indicate your interest in reviewing for a journal by clicking on the journal’s Reviewer Recognition page. Editors use Reviewer Recognition to find suitable reviewers for their journals and may contact you directly via the Reviewer Recognition site.

Why sign up to WoS Reviewer Recognition?

- Editors can clearly see your interest in reviewing for their journal.

- Editors can look into your reviewer insights, including which other journals you are reviewing for.

- Editors can rate reviewers as ‘excellent’.

- You can review your satisfaction of Reviewer Recognition.

- You can receive weekly email updates summarizing your reviewer activity on the site.

- For Sage Journals, a claimed review will result in the individual’s name being listed as a reviewer for that journal.

- Co-reviewers can also receive credit on Reviewer Recognition.

Once you are registered as a reviewer, the editors will send you an invitation to review if a manuscript in your area of expertise is submitted.

We understand that our reviewers are busy, so it may not always be possible for you to accept an invitation to review. To avoid delays, please inform the editor as soon as possible if you are unable to accept an invitation to review or encounter any issues after accepting. If you cannot review a manuscript, we appreciate if you can suggest an alternative reviewer.

Tip: To further increase your chances of receiving review invitations, see our comprehensive blog post on Steps to Strengthen Your Reviewer Profile .

Watch the Video Tutorial

Things to consider before you begin a review

- Timing Inform the editor immediately if you will not be able to meet the deadline and keep your availability updated in Sage Track to avoid receiving invitations to review when you are unavailable.

- Suitability Do you have any reason why you should not review the submission? If in doubt, check with the journal’s editor. Learn more about your ethical responsibilities as a reviewer.

- Individual Journal Reviewer Guidelines Some journals ask reviewers to answer specific questions, so check what is expected before beginning your review.

- Confidentiality You must not share the content of a paper you have been invited to review, unless you have permission from the journal’s editor. If you suspect that author misconduct has taken place, only discuss this with the editor.

- Co-reviewing Inform the journal editor if you wish to collaborate on a review with a colleague or student. See the Ethics and Responsibility page for further instructions on this.

You may also wish to refer to COPE’s guide on what to consider when asked to peer review a manuscript before beginning a review .

What to include in a review

Watch our short video, How to Conduct a Peer Review , for a step-by-step walkthrough of the review process. Alternatively, you can download our Reviewer's Guide for written instructions on how to assess a manuscript and what to include in a review.

Watch the video tutorial

DOWNLOAD REVIEWER'S GUIDE PDF

Making your recommendation

In addition to your review comments, you will likely be expected to select an overall recommendation to the editor. Sage’s most common recommendation types are:

Accept: No further revision required. The manuscript is publishable in its current form.

The majority of articles require revision before reaching this stage.

Minor Revision: The paper is mostly sound but will be sent back to the authors for minor corrections and clarifications such as the addition of minor citations or the tweaking of arguments.

These revisions should not involve any major changes. However, changes should be clearly marked for the attention of the previous reviewers. The paper may be subject to re-review.

Major Revision: The principle of the article is sound and it has a chance of being accepted but requires substantial change to be made. This may include further experiments or analysis, the inclusion of additional literature or theory, or an improvement of arguments and conclusions. The authors are required to submit a point-by-point response to the reviewers and the paper will be subject to a re-review.

If issues of quality, novelty and/or contribution* cannot be addressed through revision, the reviewer should recommend rejection rather than revision. Editors withhold the right to reject the paper should revisions be insufficient.

Reject: The manuscript is of insufficient quality, novelty or significance to warrant publication.

Even when recommending rejection, the reviewer is encouraged to share their suggestions for improvement in the Comments to the Authors field.

If you would like to give us feedback on your experience of reviewing for a Sage journal to help us to improve our systems, please contact [email protected] .

*Check the journal Aims and Scope for any specific requirements with regard to levels of novelty and/or contribution.

How to Be a Peer Reviewer webinar

Considering becoming a reviewer or getting more involved with peer review? Our free webinar will guide you through the process of conducting peer review, including how to get started, basic principles of reviewing articles, what journal editors expect from reviewers, and important considerations such as research ethics and reviewer responsibilities. Learn more here .

Learn more with the Web of Science Academy

The Web of Science Academy offers free-of-charge short courses providing researchers with the skills and experience required to become an expert peer reviewer. Courses cover:

- What's expected of you as a reviewer

- What to look for in a manuscript

- How to write a review

- Co-reviewing with a mentor

A certificate is awarded on completion of the course.

- Journal Author Gateway

- Journal Editor Gateway

- What is Peer Review?

- How to Be a Peer Reviewer Webinar

- How to Review Plain Language Summaries

- How to Review Registered Reports

- Using Sage Track

- Peer Review Ethics

- Resources for Reviewers

- Reviewer Rewards

- Ethics & Responsibility

- Sage Editorial Policies

- Publication Ethics Policies

- Sage Chinese Author Gateway 中国作者资源

- Open Resources & Current Initiatives

- Discipline Hubs

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- The PRISMA 2020...

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews

- Related content

- Peer review

- Matthew J Page , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Joanne E McKenzie , associate professor 1 ,

- Patrick M Bossuyt , professor 2 ,

- Isabelle Boutron , professor 3 ,

- Tammy C Hoffmann , professor 4 ,

- Cynthia D Mulrow , professor 5 ,

- Larissa Shamseer , doctoral student 6 ,

- Jennifer M Tetzlaff , research product specialist 7 ,

- Elie A Akl , professor 8 ,

- Sue E Brennan , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Roger Chou , professor 9 ,

- Julie Glanville , associate director 10 ,

- Jeremy M Grimshaw , professor 11 ,

- Asbjørn Hróbjartsson , professor 12 ,

- Manoj M Lalu , associate scientist and assistant professor 13 ,

- Tianjing Li , associate professor 14 ,

- Elizabeth W Loder , professor 15 ,

- Evan Mayo-Wilson , associate professor 16 ,

- Steve McDonald , senior research fellow 1 ,

- Luke A McGuinness , research associate 17 ,

- Lesley A Stewart , professor and director 18 ,

- James Thomas , professor 19 ,

- Andrea C Tricco , scientist and associate professor 20 ,

- Vivian A Welch , associate professor 21 ,

- Penny Whiting , associate professor 17 ,

- David Moher , director and professor 22

- 1 School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

- 2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3 Université de Paris, Centre of Epidemiology and Statistics (CRESS), Inserm, F 75004 Paris, France

- 4 Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia

- 5 University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA; Annals of Internal Medicine

- 6 Knowledge Translation Program, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, Toronto, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 7 Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada

- 8 Clinical Research Institute, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon; Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 9 Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, USA

- 10 York Health Economics Consortium (YHEC Ltd), University of York, York, UK

- 11 Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 12 Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Odense (CEBMO) and Cochrane Denmark, Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Open Patient data Exploratory Network (OPEN), Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

- 13 Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Clinical Epidemiology Program, Blueprint Translational Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; Regenerative Medicine Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

- 14 Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado, United States; Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- 15 Division of Headache, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; Head of Research, The BMJ , London, UK

- 16 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Indiana University School of Public Health-Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

- 17 Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 18 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK

- 19 EPPI-Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

- 20 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Epidemiology Division of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Institute of Health Management, Policy, and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; Queen's Collaboration for Health Care Quality Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Queen's University, Kingston, Canada

- 21 Methods Centre, Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 22 Centre for Journalology, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- Correspondence to: M J Page matthew.page{at}monash.edu

- Accepted 4 January 2021

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, published in 2009, was designed to help systematic reviewers transparently report why the review was done, what the authors did, and what they found. Over the past decade, advances in systematic review methodology and terminology have necessitated an update to the guideline. The PRISMA 2020 statement replaces the 2009 statement and includes new reporting guidance that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies. The structure and presentation of the items have been modified to facilitate implementation. In this article, we present the PRISMA 2020 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and the revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews.

Systematic reviews serve many critical roles. They can provide syntheses of the state of knowledge in a field, from which future research priorities can be identified; they can address questions that otherwise could not be answered by individual studies; they can identify problems in primary research that should be rectified in future studies; and they can generate or evaluate theories about how or why phenomena occur. Systematic reviews therefore generate various types of knowledge for different users of reviews (such as patients, healthcare providers, researchers, and policy makers). 1 2 To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did (such as how studies were identified and selected) and what they found (such as characteristics of contributing studies and results of meta-analyses). Up-to-date reporting guidance facilitates authors achieving this. 3

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement published in 2009 (hereafter referred to as PRISMA 2009) 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 is a reporting guideline designed to address poor reporting of systematic reviews. 11 The PRISMA 2009 statement comprised a checklist of 27 items recommended for reporting in systematic reviews and an “explanation and elaboration” paper 12 13 14 15 16 providing additional reporting guidance for each item, along with exemplars of reporting. The recommendations have been widely endorsed and adopted, as evidenced by its co-publication in multiple journals, citation in over 60 000 reports (Scopus, August 2020), endorsement from almost 200 journals and systematic review organisations, and adoption in various disciplines. Evidence from observational studies suggests that use of the PRISMA 2009 statement is associated with more complete reporting of systematic reviews, 17 18 19 20 although more could be done to improve adherence to the guideline. 21

Many innovations in the conduct of systematic reviews have occurred since publication of the PRISMA 2009 statement. For example, technological advances have enabled the use of natural language processing and machine learning to identify relevant evidence, 22 23 24 methods have been proposed to synthesise and present findings when meta-analysis is not possible or appropriate, 25 26 27 and new methods have been developed to assess the risk of bias in results of included studies. 28 29 Evidence on sources of bias in systematic reviews has accrued, culminating in the development of new tools to appraise the conduct of systematic reviews. 30 31 Terminology used to describe particular review processes has also evolved, as in the shift from assessing “quality” to assessing “certainty” in the body of evidence. 32 In addition, the publishing landscape has transformed, with multiple avenues now available for registering and disseminating systematic review protocols, 33 34 disseminating reports of systematic reviews, and sharing data and materials, such as preprint servers and publicly accessible repositories. To capture these advances in the reporting of systematic reviews necessitated an update to the PRISMA 2009 statement.

Summary points

To ensure a systematic review is valuable to users, authors should prepare a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the review was done, what they did, and what they found

The PRISMA 2020 statement provides updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews that reflects advances in methods to identify, select, appraise, and synthesise studies

The PRISMA 2020 statement consists of a 27-item checklist, an expanded checklist that details reporting recommendations for each item, the PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist, and revised flow diagrams for original and updated reviews

We anticipate that the PRISMA 2020 statement will benefit authors, editors, and peer reviewers of systematic reviews, and different users of reviews, including guideline developers, policy makers, healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders

Development of PRISMA 2020

A complete description of the methods used to develop PRISMA 2020 is available elsewhere. 35 We identified PRISMA 2009 items that were often reported incompletely by examining the results of studies investigating the transparency of reporting of published reviews. 17 21 36 37 We identified possible modifications to the PRISMA 2009 statement by reviewing 60 documents providing reporting guidance for systematic reviews (including reporting guidelines, handbooks, tools, and meta-research studies). 38 These reviews of the literature were used to inform the content of a survey with suggested possible modifications to the 27 items in PRISMA 2009 and possible additional items. Respondents were asked whether they believed we should keep each PRISMA 2009 item as is, modify it, or remove it, and whether we should add each additional item. Systematic review methodologists and journal editors were invited to complete the online survey (110 of 220 invited responded). We discussed proposed content and wording of the PRISMA 2020 statement, as informed by the review and survey results, at a 21-member, two-day, in-person meeting in September 2018 in Edinburgh, Scotland. Throughout 2019 and 2020, we circulated an initial draft and five revisions of the checklist and explanation and elaboration paper to co-authors for feedback. In April 2020, we invited 22 systematic reviewers who had expressed interest in providing feedback on the PRISMA 2020 checklist to share their views (via an online survey) on the layout and terminology used in a preliminary version of the checklist. Feedback was received from 15 individuals and considered by the first author, and any revisions deemed necessary were incorporated before the final version was approved and endorsed by all co-authors.

The PRISMA 2020 statement

Scope of the guideline.

The PRISMA 2020 statement has been designed primarily for systematic reviews of studies that evaluate the effects of health interventions, irrespective of the design of the included studies. However, the checklist items are applicable to reports of systematic reviews evaluating other interventions (such as social or educational interventions), and many items are applicable to systematic reviews with objectives other than evaluating interventions (such as evaluating aetiology, prevalence, or prognosis). PRISMA 2020 is intended for use in systematic reviews that include synthesis (such as pairwise meta-analysis or other statistical synthesis methods) or do not include synthesis (for example, because only one eligible study is identified). The PRISMA 2020 items are relevant for mixed-methods systematic reviews (which include quantitative and qualitative studies), but reporting guidelines addressing the presentation and synthesis of qualitative data should also be consulted. 39 40 PRISMA 2020 can be used for original systematic reviews, updated systematic reviews, or continually updated (“living”) systematic reviews. However, for updated and living systematic reviews, there may be some additional considerations that need to be addressed. Where there is relevant content from other reporting guidelines, we reference these guidelines within the items in the explanation and elaboration paper 41 (such as PRISMA-Search 42 in items 6 and 7, Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline 27 in item 13d). Box 1 includes a glossary of terms used throughout the PRISMA 2020 statement.

Glossary of terms

Systematic review —A review that uses explicit, systematic methods to collate and synthesise findings of studies that address a clearly formulated question 43

Statistical synthesis —The combination of quantitative results of two or more studies. This encompasses meta-analysis of effect estimates (described below) and other methods, such as combining P values, calculating the range and distribution of observed effects, and vote counting based on the direction of effect (see McKenzie and Brennan 25 for a description of each method)

Meta-analysis of effect estimates —A statistical technique used to synthesise results when study effect estimates and their variances are available, yielding a quantitative summary of results 25

Outcome —An event or measurement collected for participants in a study (such as quality of life, mortality)

Result —The combination of a point estimate (such as a mean difference, risk ratio, or proportion) and a measure of its precision (such as a confidence/credible interval) for a particular outcome

Report —A document (paper or electronic) supplying information about a particular study. It could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report, or any other document providing relevant information

Record —The title or abstract (or both) of a report indexed in a database or website (such as a title or abstract for an article indexed in Medline). Records that refer to the same report (such as the same journal article) are “duplicates”; however, records that refer to reports that are merely similar (such as a similar abstract submitted to two different conferences) should be considered unique.

Study —An investigation, such as a clinical trial, that includes a defined group of participants and one or more interventions and outcomes. A “study” might have multiple reports. For example, reports could include the protocol, statistical analysis plan, baseline characteristics, results for the primary outcome, results for harms, results for secondary outcomes, and results for additional mediator and moderator analyses

PRISMA 2020 is not intended to guide systematic review conduct, for which comprehensive resources are available. 43 44 45 46 However, familiarity with PRISMA 2020 is useful when planning and conducting systematic reviews to ensure that all recommended information is captured. PRISMA 2020 should not be used to assess the conduct or methodological quality of systematic reviews; other tools exist for this purpose. 30 31 Furthermore, PRISMA 2020 is not intended to inform the reporting of systematic review protocols, for which a separate statement is available (PRISMA for Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement 47 48 ). Finally, extensions to the PRISMA 2009 statement have been developed to guide reporting of network meta-analyses, 49 meta-analyses of individual participant data, 50 systematic reviews of harms, 51 systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies, 52 and scoping reviews 53 ; for these types of reviews we recommend authors report their review in accordance with the recommendations in PRISMA 2020 along with the guidance specific to the extension.

How to use PRISMA 2020

The PRISMA 2020 statement (including the checklists, explanation and elaboration, and flow diagram) replaces the PRISMA 2009 statement, which should no longer be used. Box 2 summarises noteworthy changes from the PRISMA 2009 statement. The PRISMA 2020 checklist includes seven sections with 27 items, some of which include sub-items ( table 1 ). A checklist for journal and conference abstracts for systematic reviews is included in PRISMA 2020. This abstract checklist is an update of the 2013 PRISMA for Abstracts statement, 54 reflecting new and modified content in PRISMA 2020 ( table 2 ). A template PRISMA flow diagram is provided, which can be modified depending on whether the systematic review is original or updated ( fig 1 ).

Noteworthy changes to the PRISMA 2009 statement

Inclusion of the abstract reporting checklist within PRISMA 2020 (see item #2 and table 2 ).

Movement of the ‘Protocol and registration’ item from the start of the Methods section of the checklist to a new Other section, with addition of a sub-item recommending authors describe amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol (see item #24a-24c).

Modification of the ‘Search’ item to recommend authors present full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites searched, not just at least one database (see item #7).

Modification of the ‘Study selection’ item in the Methods section to emphasise the reporting of how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process (see item #8).

Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Data items’ item recommending authors report how outcomes were defined, which results were sought, and methods for selecting a subset of results from included studies (see item #10a).

Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Methods section into six sub-items recommending authors describe: the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis; any methods required to prepare the data for synthesis; any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses; any methods used to synthesise results; any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (such as subgroup analysis, meta-regression); and any sensitivity analyses used to assess robustness of the synthesised results (see item #13a-13f).

Addition of a sub-item to the ‘Study selection’ item in the Results section recommending authors cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded (see item #16b).

Splitting of the ‘Synthesis of results’ item in the Results section into four sub-items recommending authors: briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among studies contributing to the synthesis; present results of all statistical syntheses conducted; present results of any investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results; and present results of any sensitivity analyses (see item #20a-20d).

Addition of new items recommending authors report methods for and results of an assessment of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome (see items #15 and #22).

Addition of a new item recommending authors declare any competing interests (see item #26).

Addition of a new item recommending authors indicate whether data, analytic code and other materials used in the review are publicly available and if so, where they can be found (see item #27).

PRISMA 2020 item checklist

- View inline

PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist*

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram template for systematic reviews. The new design is adapted from flow diagrams proposed by Boers, 55 Mayo-Wilson et al. 56 and Stovold et al. 57 The boxes in grey should only be completed if applicable; otherwise they should be removed from the flow diagram. Note that a “report” could be a journal article, preprint, conference abstract, study register entry, clinical study report, dissertation, unpublished manuscript, government report or any other document providing relevant information.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

We recommend authors refer to PRISMA 2020 early in the writing process, because prospective consideration of the items may help to ensure that all the items are addressed. To help keep track of which items have been reported, the PRISMA statement website ( http://www.prisma-statement.org/ ) includes fillable templates of the checklists to download and complete (also available in the data supplement on bmj.com). We have also created a web application that allows users to complete the checklist via a user-friendly interface 58 (available at https://prisma.shinyapps.io/checklist/ and adapted from the Transparency Checklist app 59 ). The completed checklist can be exported to Word or PDF. Editable templates of the flow diagram can also be downloaded from the PRISMA statement website.

We have prepared an updated explanation and elaboration paper, in which we explain why reporting of each item is recommended and present bullet points that detail the reporting recommendations (which we refer to as elements). 41 The bullet-point structure is new to PRISMA 2020 and has been adopted to facilitate implementation of the guidance. 60 61 An expanded checklist, which comprises an abridged version of the elements presented in the explanation and elaboration paper, with references and some examples removed, is available in the data supplement on bmj.com. Consulting the explanation and elaboration paper is recommended if further clarity or information is required.