- Search Menu

- About OAH Magazine of History

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The bigger picture, teaching the lesson, reflections and conclusions.

- < Previous

Interpreting John Brown: Infusing Historical Thinking into the Classroom

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Bruce A. Lesh, Interpreting John Brown: Infusing Historical Thinking into the Classroom, OAH Magazine of History , Volume 25, Issue 2, April 2011, Pages 46–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/oahmag/oar003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

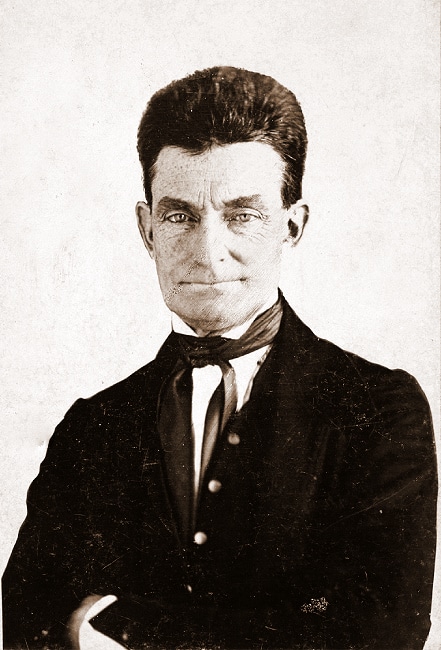

John Brown has been subject to constant reinterpretation in the century and half since he led the 1859 attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. In this photograph by John H. Tarbell, an unnamed African American man in Ashville, North Carolina is holding a copy of Joseph Barry's The Strange Story of Harper's Ferry , published a year earlier. Judging by the man's age, he was alive in 1859, and quite possibly enslaved. One can only wonder at his interpretation of John Brown. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

On the cusp of his December 1859 execution for treason, murder, and inciting a slave rebellion, John Brown handed a note to his guard which read, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood.” Although the institution of slavery was purged in the crucible of the American Civil War, John Brown's determination to expose and end chattel slavery still resonates. The multiple legacies of slavery and questions about the efficacy of violence as a tool for change in a democratic society continually bring historians and teachers back to the complicated life of John Brown. When students consider Brown's contributions to the American narrative, lines between advocacy and criminality, contrasts between intensity and obsession, and differences between democratic ideals and harsh reality are brought to the surface. To this day, artists, authors, historians, political activists, and creators of popular culture maintain a fascination with the antebellum rights-warrior and his death.

This continuing interest in John Brown presents a great teaching opportunity. Not only can we help to situate John Brown within the context of his era, but we can explore how historical interpretations of the man and his actions have changed over time. The lesson I describe in this article asks students to consider Brown's biography, multiple artistic representations of the abolitionist, as well as historical and contemporary viewpoints in order to develop an evidence-based interpretation of how this controversial historical figure should be commemorated. Students conduct an analysis of the diverse, and often conflicting, historical sources, and then apply their interpretations to the development of a historical marker that would be placed at the Harper's Ferry National Historical Park. In this sense, Brown provides a unique opportunity for students to examine a figure whose actions, and their attendant meanings, tell us as much about antebellum America and the origins of the Civil War as they do about our own time.

Challenging students to develop an interpretation of John Brown ties into my broader philosophy about history instruction. Research on history education, going back nearly a century, indicates that few students retain, understand, or enjoy their school experiences with history ( 1 ). This dismal track record stems from a teaching method that relies primarily on the memorization of names and dates. To limit the study and assessment of history to a student's ability to regurgitate these facts hides the true nature of the discipline. History, at its core, is the study of questions and the analysis of evidence in an effort to develop and defend thoughtful responses. For students to truly be engaged with the past, they must be taught thinking skills that mirror those employed by historians. Recent research suggests that students are more capable of evaluating historical sources, using them to develop an interpretation, and articulating their interpretations in a variety of formats. When doing so, students become powerful thinkers rather than consumers of a predetermined narrative path ( 2 ).

Asking questions about causality, chronology, continuity and change over time , multiple perspectives , contingency , empathy , significance, and motivation enable students to use the substantive information to address essential historical issues. In addition, students must be taught to approach historical sources with the understanding that they are repositories of information that reflect a particular temporal, geographic, and socio-economic perspective. Analyzing a variety of historical sources—be they diaries, artifacts, music, images, or monographs—enables students to scrutinize the remnants of the past and apply this evidence to the task at hand. Employing these historical thinking skills in a classroom setting empowers students to use the names, dates, and events to develop, revise, and defend evidence-based interpretations of the questions that drive the study of history ( 3 ).

Given the path illuminated in the scholarship and my own experiences with teaching history to high school students for eighteen years, I planned the John Brown lesson with an emphasis on source work and student development of evidence-based explanations focused on a key historical question. At the conclusion of the lesson, my students are asked to determine how John Brown and his life should be commemorated. Engaging in many, though not all, of the considerations involved in public history, my students set out to interpret Brown's life for a twenty-first century audience. To do so, they must get to know the individual, his actions, and how Brown was seen by both his contemporaries and historians from his time to the present.

Born in the first year of the nineteenth century to a devoutly Calvinist family, John Brown credits witnessing a slave being beaten with a shovel as the origin of his devotion to the anti-slavery cause. Unlike most of the abolitionists that arose in the 1830s, Brown was dedicated to both the abolition of chattel slavery and racial equality. This commitment was exemplified in his 1838 decision to escort a free black to sit in his family pew. This bold act led to his family's expulsion from the church. In a fruitless attempt to become economically solvent, Brown moved to Springfield, Massachusetts in 1846 to develop his wool business. In Springfield, Brown befriended, lived among, and attended church alongside African Americans. Brown's sincere empathy for the plight of the slave was reflected in a letter written by abolitionist Frederick Douglass after meeting Brown. Douglass, who made a trip to Springfield expressly to meet Brown, stated that Brown was “in sympathy, a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.” During this meeting, Brown revealed what he called his “Subterranean Pass Way.” Using the Appalachian Mountains as a base, this plan envisioned a rebellion that would arm slaves, encourage their revolt, and direct people northward to freedom. It was in Springfield where Brown first revealed the elements of what would become the final act of his life: a raid on the South to promote a slave rebellion.

In 1849, Brown moved his family to North Elba, New York to live on a communal farm created by abolitionist Gerrit Smith ( Figure 2 ). Living with black families was a clear indication of Brown's commitment to a biracial society. In 1851, reacting to the Fugitive Slave provisions of the Compromise of 1850, Brown returned to Springfield and established the League of Gileadites. Dedicated to protecting escaped slaves from slave catchers, the League was a concrete expression of Brown's visceral distaste for federal complicity with the institution of slavery. Brown vehemently expressed his passion for equality in May of 1858, when he presented his “Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States” to an anti-slavery convention in Ontario, Canada. Essentially a new constitution for a slavery-free United States, the document stated that:

In 1848, John Brown learned of abolitionist Gerrit Smith's offer of free land to blacks in the Adirondacks. The next year, Brown moved his family to North Elba, New York to join this experiment. Though he soon left for “Bloody” Kansas, he considered North Elba his home and asked to be buried there. In 1935, the John Brown Memorial Association dedicated this statue, designed by Joseph P. Pollia, just north of the gravesite, now part of the John Brown Farm State Historic Site: < http://nysparks.state.ny.us/historic-sites/29/details.aspx > (Courtesy of photographer David Blakie, < http://davidblaikie.ca/ >)

Whereas slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion-the only conditions of which are perpetual imprisonment and hopeless servitude or absolute extermination-in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence:

Therefore, we, citizens of the United States, and the oppressed people who, by a recent decision of the Supreme Court, [The Dred Scott Decisions] are declared to have no rights which the white man is bound to respect, together with all other people degraded by the laws thereof, do, for the time being, ordain and establish for ourselves the following Provisional Constitution and Ordinances, the better to protect our persons, property, lives, and liberties, and to govern our actions ( 4 ).

This was a clear statement of Brown's opposition to slavery and his dedication to equality. Yet for Brown, it was not words, but actions, that seared his name into the pantheon of American history. Speaking to the community of former slaves in Canada, Brown announced his plan to invade the American South and foment a slave rebellion using the mountains of western Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama to provide cover for his uprising. It would be this uprising that occupied much of his travel, speaking, and fundraising between 1858 and his death in 1859.

Brown's first overt public action took place in May of 1856. In Kansas, Brown led a group of men on a raid that killed five proslavery men along the Pottawatomie Creek. Though Brown claimed not to have participated in the actual murders, the brutality of the act has come to symbolize the violence that struck Kansas territory as a result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Violence as a tool for change was again employed by Brown in 1858 in Missouri. Brown entered Vernon County, just across the Kansas border, and attacked several proslavery farmers, stole horses and wagons, and secured the freedom of eleven enslaved persons. His raid led to the deaths of several farmers, and consequently a bounty of $250 was placed on his head by President James Buchanan and his name was splashed over newspapers across the nation. After traveling more than a thousand miles over eighty-plus days, Brown delivered the newly liberated former-slaves into the hands of Canada and freedom.

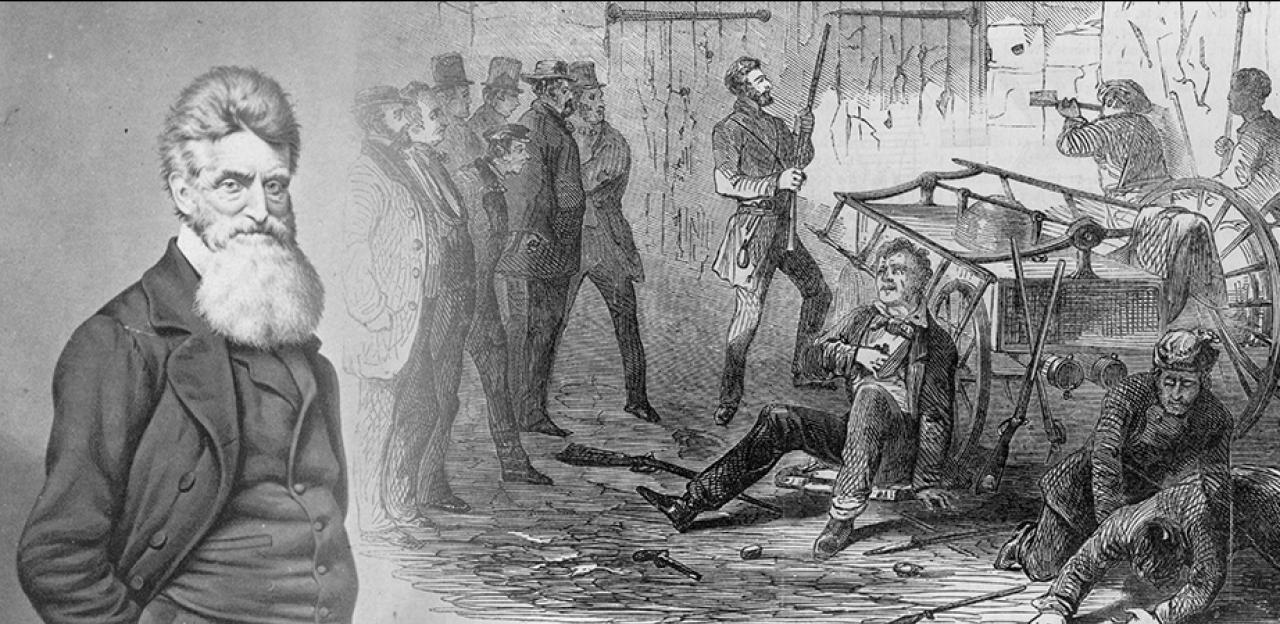

Secretly funded by six abolitionists from Massachusetts, armed with thousands of pikes purchased in Connecticut, driven by his deep disdain for slavery, and supported by twenty-one other men, Brown headed to western Maryland to reconnoiter for his final attempt to foment a rebellion aimed at destroying the institution of slavery. The raid on the federal arsenal in Harper's Ferry, Virginia was initiated on the evening of October 16, 1859. In what quickly developed into a rout, more than half of Brown's followers were killed and the remaining eight, including Brown, were captured the following day. Indicted, found guilty, and sentenced to die, John Brown was hanged in Charlestown, Virginia on December 2, 1859 ( 5 ).

John Brown of Osawatomie spake on his dying day: ‘I will not have to shrive my soul a priest in Slavery's pay; But let some poor slave-mother whom I have striven to free, With her children, from the gallows-stair put up a prayer for me!’ John Brown of Ossawatomie, they led him out to die; And lo! a poor slave-mother with her little child pressed nigh: Then the bold, blue eye grew tender, and the old harsh face grew mild, As he stooped between the jeering ranks and kissed the negro's child! The shadows of his stormy life that moment fell apart, And they who blamed the bloody hand forgave the loving heart; That kiss from all its guilty means redeemed the good intent, And round the grisly fighter's hair the martyr's aureole bent! ( 6 )

The notion of Brown consecrating his sacrifice for slaves with a kiss to the cheek of a slave child found visual form in the 1860 painting, John Brown on His Way to Execution by Louis Ransom. It was further popularized by an 1863 Currier and Ives colored lithograph entitled John Brown , and subtitled Meeting the slave-mother and her child on the steps of Charlestown jail on his way to execution. Thomas Noble's John Brown's Blessing appeared in 1867, a redrawn Currier and Ives, John Brown—The Martyr debuted in 1870. Finally, in 1884, Thomas Hovenden painted his memorialization of the mythical kiss in his Last Moments of John Brown (See cover image) ( 7 ). This introductory element of the lesson fertilizes the pedagogical ground for growing a deep and meaningful investigation of Brown.

Based on an 1859 painting by Louis Ransom, this Currier & Ives lithograph is entitled John Brown. Meeting the slave-mother and her child on the steps of Charlestown jail on his way to execution . A precursor of Thomas Hovenden's 1884 painting on the cover of this issue, it offers a darker, more symbolic depiction of the mythical event. To Brown's left, we see his elderly jailer, a wealthy slaveholder, and a militia member dressed in an aristocratic uniform. To his right stands the embodied spirit of the American Revolution somberly assessing the scene and a soldier pushing back an enslaved woman who suckles her light-skinned child, perhaps the product of a rape by her master. Behind her stands a broken and neglected statue of Justice. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

A one-page biographical reading, assigned for homework, is used to structure class discussion of Brown's upbringing, his early efforts to address slavery in Springfield, Massachusetts, and the events leading up to his attack on the federal arsenal in Harper's Ferry. Emphasis is drawn to Brown's religious beliefs, his role in “Bleeding Kansas,” his raid into Missouri, and finally the ill-fated Harper's Ferry Raid. To firmly place Brown's actions within the growing sectional mentality of the 1850s, I discuss with students the various sectional reactions to Brown's failed raid. With the contrasting images of Brown fresh in their minds, I inform students that it is their task to determine how Brown should be memorialized historically.

To deepen their analysis of Brown, students are assigned one of several readings. Selected to represent contrasting interpretations of the man and his actions, these readings are intended to complicate students’ investigation. I traditionally select six sources from the list of “Further Readings” located at the end of the article, but I have provided all of the potential sources on the online version of the lesson materials. Historiographically, the discussion of Brown has evolved from the hero-worship of James Redpath and Oswald Garrison Villard to critical analysis of his mental state as found in the work of Bruce Catton and James C. Malin.

Students are organized so that all of the six sources are represented within a group. Each student then presents the interpretation of John Brown expounded by their source. Next, to assist students in better understanding each perspective, I identify some relevant background information of the various authors and the time period in which they wrote. It is important to ensure that students consider authorship, context, and subtext as they derive information from a historical source. By confronting the milieu in which Malcolm X spoke about Brown, or how personal biography impacts Villard's telling of the Brown story, students are forced to consider the sources not as words, but as a perspective informed by and reflecting the social, cultural, economic, and political background of the author and the time period of its construction. Exposing the subtext of each source illuminates for students how John Brown has been interpreted differently and empowers them to develop their own evidence-based interpretations of the past.

Since I teach a forty-five minute class period, my lesson usually breaks in the midst of students sharing the evidence provided by their sources. At times, I will ask students, as homework between day one and two of the lesson, to consult one Northern and one Southern editorial found at < http://history.furman.edu/editorials/see.py >. These articles, and the context and subtext that influence their perspectives, help complicate, but also deepen, our final discussion on how to commemorate John Brown.

After sharing and taking notes, students are asked to consider how they feel John Brown and his actions should be commemorated. Small group discussions of the topic eventually become a large group debate. It is key to this phase of the lesson that students base their interpretations on the evidence they have confronted. Issues of authorship and context add to our discussion about what John Brown means to the telling of American history and how his efforts should be memorialized.

At the conclusion of the lesson, students are asked to apply the evidence they have examined to one of two assessments. The first option is to complete a historical marker that is to be placed at the entrance of the Harper's Ferry National Historic Park. The second is to select five items that would be displayed in the museum at the same park, explain why they were selected, and how these items help to describe John Brown and account for his actions. These assessments place students in a position where they must adhere to the basic historical facts in order to develop and defend an interpretation of the choice they made about commemorating John Brown. Either iteration of the assessment requires students to identify what historical sources informed their decisions and how these sources influenced their choices.

Students have a hard time wrapping their minds around John Brown. Go figure, so do historians. Brown has been the subject of hundreds of books, articles, documentaries, and other forms of historical interpretation. My students, just as historians, are drawn into the complexities of Brown's personality and the actions he takes over the course of his life.

When crafting their interpretations for the historical marker, students tend to run in one of three directions. A large number take a middle of the road approach. After examining the multiple images and textual viewpoints of Brown, they stick to what they see as the pertinent facts. Gone are incendiary adjectives or overt ideological typecasting of Brown and his actions. In many ways, their markers are reminiscent of those produced by the National Park Service for many historical figures and events. The second third stress Brown's actions in both Missouri and Harper's Ferry, but do not address his beliefs. They reflect in their analysis that they are unwilling or unable to determine if he was crazy, obsessively focused, or simply devoted to his cause. The final third interpret and represent Brown as a madman whose actions intentionally set the nation barreling towards civil discord.

What strikes me about this lesson is that students come to see history as alive and interpretive, rather than inert and handed down from some central authoritative body. Most instruments that measure student achievement in history would simply ask students to select the response in a multiple choice question that correctly identifies the impact of Brown's actions. This is achieved within the first five minutes of my lesson. Instead, it is the pastness of Brown that captures their interest and generates in-depth analysis, far beyond a discussion that establishes the basis for an answer to a multiple-choice question. The power and depth of the discussion generated about Brown has been the impetus for me to apply this structure to other historical figures and events. Individuals such as Nat Turner, Daniel Shays, or Eugene Debs and events such as the Haymarket Affair, Busing in Boston, or the Tet Offensive become ripe for deep historical investigation once I realized that my students could do so. The depth of connection my students make with these watershed events and transitional figures far outweighs the time it takes to plan or execute such investigations.

At the same time, the power of images to quickly connect students to a topic is also readily evident when I teach this lesson. The images empower students to become more critical in their analysis of the textual sources they are asked to read. Because the images are so stark, both in contrast to one another as well as individually, students look for similar differences within the text. This transfer of critical reading from the more comfortable image analysis to the more difficult text is a key ingredient for students as they evolve their abilities to think historically. When students are taught to be aware that historical sources are not simply repositories of information, but instead vehicles for communicating an author's perspective on an individual, event, or historical idea, they are enabled to begin crossing the bridge from the “unnatural act of thinking historically” towards a mindset more parallel to that employed by historians.

Ultimately, what my students enjoy is the opportunity to examine the past rather than having it examined for them. The occasion to apply historical thinking skills to determine how to commemorate the life and actions of one of the most divisive figures in American History empowers students to examine multiple sources of historical evidence, develop, revise, and defend evidence-based interpretations, and grapple with key questions of the past. Just as John Brown taught us that challenging the norms of American society is a difficult endeavor, so too is challenging the manner in which we approach teaching history.

J. Carelton Bell and David F. McCollum, “A Study of the Attainments of Pupils in United States History,” Journal of Educational Psychology 8 (1917): 257–74; James P. Shaver, O.L. Davis, Jr., and Suzanne Helburn, “The Status of Social Studies Education: Impressions from Three NSF Studies,” Social Education (February 1979): 150–53; James B. Schick, “What do Students Really Think of History?” The History Teacher , 24 (May 1991): 331–42; T he Nation's Report Card: U.S. History 2006. National Assessment of Educational Progress at grades 4, 8, and 12 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, United States Department of Education, 2006); Anne Neal and Jerry Martin, Losing America's Memory: Historical Illiteracy in the 21st Century (Washington, D.C.: American Council of Trustees and Alumni, 2000); Dale Whittington, “What Have 17-Year Olds Known in the Past?” American Educational Research Journal 28 (Winter 1991): 759–80.

Bruce VanSledright. The Challenge of Rethinking History Education: On Practices, Theories, and Policy (New York: Routledge, 2010); Nikki Mandell and Bobbie Malone. Thinking Like a Historian: Rethinking History Instruction, A Framework to Enhance and Improve Teaching and Learning (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007); Keith Barton. “Research on Students’ Historical Thinking and Learning.” AHA Perspectives Magazine , October 2004, 19–21.

Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001); Bruce VanSledright, I n Search of America's Past: Learning to Read History in Elementary School (New York: Teacher's College Press, 2002); Suzanne M. Donovan and John D. Bransford, eds. How Students Learn: History in the Classroom (Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2005); Lendol Calder, “Uncoverage: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey.” Journal of American History , March 2006, 1358–1370.

“John Brown's Provisional Constitution,” University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law, < http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/johnbrown/brownconstitution.html .>.

David Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (New York: Vintage Books, 2005). Jonathan Earle, John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry: A Brief History with Documents (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2008).

John Greenleaf Whittier, “Brown of Ossawatomie,” The Lost Museum, < http://chnm.gmu.edu/lostmuseum/lm/144/ .>.

James C. Malin, “ The John Brown Legend in Pictures, Kissing the Negro Baby,” Kansas Historical Quarterly 8 (1939): 339–441, < www.kancoll.org/khq/1939/39_4_malin.htm .>.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1938-2340

- Print ISSN 0882-228X

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 27, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

John Brown was a leading figure in the abolitionist movement in the pre-Civil War United States. Unlike many anti-slavery activists, he was not a pacifist and believed in aggressive action against slaveholders and any government officials who enabled them. An entrepreneur who ran tannery and cattle trading businesses prior to the economic crisis of 1839, Brown became involved in the abolitionist movement following the brutal murder of Presbyterian minister and anti-slavery activist Elijah P. Lovejoy in 1837. He said at the time, “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery !”

Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington , Connecticut, the son of Owen and Ruth Mills Brown. His father, who was in the tannery business, relocated the family to Ohio , where the abolitionist spent most of his childhood.

The Brown family’s new home of Hudson, Ohio , happened to be a key stop on the Underground Railroad , and Owen Brown became active in the effort to bring former enslaved people to freedom. The family home soon became a safe house for fugitive enslaved people.

The younger Brown left his family at 16 for Massachusetts and then Connecticut , where he attended school and was ordained a Congregational minister. By 1819, though, he had returned to Hudson and opened a tannery of his own, on the opposite side of town from his father. He also married and started a family during that time.

Did you know? John Brown declared bankruptcy at age 42 and had more than 20 lawsuits filed against him.

Family and Financial Problems

Initially, Brown’s business ventures were very successful, but by the 1830s his finances took a turn for the worse. It didn’t help that he lost his wife and two of his children to illness at the time.

He relocated the family business and his four surviving children to present-day Kent, Ohio . However, Brown’s financial losses continued to mount, although he did remarry in 1833.

With a new business partner, Brown set up shop in Springfield, Massachusetts , hoping to reverse his fortunes. In addition to finding some business success, Brown quickly became immersed in the city’s influential abolitionist community.

He also became more familiar with the so-called mercantile class of wealthy entrepreneurs and their often ruthless business practices. It is in Springfield that many historians believe Brown became a radical abolitionist.

By 1850, he had relocated his family again, this time to the Timbuctoo farming community in the Adirondack region of New York State. Abolitionist leader Gerrit Smith was providing land in the area to Black farmers—at that time, owning land or a house enabled Black men to vote.

Brown bought a farm there himself, near Lake Placid, New York , where he not only worked the land but could advise and assist members of the Black communities in the region.

Bleeding Kansas

Brown’s first militant actions as part of the abolitionist movement didn’t occur until 1855. By then, two of his sons had started families of their own, in the western territory that eventually became the state of Kansas .

His sons were involved in the abolitionist movement in the territory, and they summoned their father, fearing attack from pro-slavery settlers. Confident he and his family could bring Kansas into the Union as a “free" state for Black people, Brown went west to join his sons.

After pro-slavery activists attacked at Lawrence, Kansas , in 1856, Brown and other abolitionists mounted a counterattack. They targeted a group of pro-slavery settlers called the Pottawatomie Rifles.

What became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre occurred on May 25, 1856, and resulted in the deaths of five pro-slavery settlers.

These and other events surrounding Kansas' difficult transition to statehood, made even more complicated by the issue of slavery, became known as Bleeding Kansas . But John Brown’s legend as a militant abolitionist was just beginning.

Over the next several years, Brown’s efforts in Kansas continued, and two of his sons were captured — and a third was killed — by pro-slavery settlers.

The abolitionist was undaunted, however, and Brown still advocated for the movement, traveling all over the country to raise money and obtain weapons for the cause. In the meantime, Kansas held elections and voted to be a free state in 1858.

Harpers Ferry

By early 1859, Brown was leading raids to free enslaved people in areas where forced labor was still in practice, primarily in the present-day Midwest. At this time, he also met Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass , activists and abolitionists both, and they became important people in Brown’s life, reinforcing much of his ideology.

With Tubman, whom he called “General Tubman,” Brown began planning an attack on slaveholders, as well as a United States military armory, at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia ), using armed freed enslaved people. He hoped the attack would help lay the groundwork for a revolt, but historians have called the raid a dress rehearsal for the Civil War .

Brown recruited 22 men in all, including his sons Owen and Watson, and several freed enslaved people. The group received military training in advance of the raid from experts within the abolitionist movement.

John Brown's Raid

The operation began on October 16, 1859, with the planned capture of Colonel Lewis Washington, a distant relative of George Washington , at the former’s estate. The Washington family continued to own enslaved people.

A group of men, led by Owen Brown, was able to kidnap Washington, while the rest of the men, with John Brown at the lead, began a raid on Harpers Ferry to seize both weapons and pro-slavery leaders in the town. Key to the raid’s success was accomplishing the objective — namely the seizure of the armory — before officials in Washington, D.C., could be informed and send in reinforcements.

To that end, John Brown’s men stopped a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train headed for the nation’s capital. However, Brown relented and let the train continue—the conductor ultimately notified authorities in Washington about what was happening at Harpers Ferry.

It was during the efforts to stop the train that the first casualty of the raid on Harpers Ferry occurred. A baggage handler at the town’s train station was shot in the back and killed when he refused the orders of Brown’s men. The victim was a free Black man—one of the very people the abolitionist movement sought to help.

John Brown's Fort

Brown’s men were able to capture several local slaveowners but, by the end of the day on October 16, local townspeople began to fight back. Early the next morning, they raised a local militia, which captured a bridge crossing the Potomac River, effectively cutting off an important escape route for Brown and his compatriots.

Although Brown and his men were able to take the Harpers Ferry armory during the morning of October 17, the local militia soon had the facility surrounded, and the two sides traded gunfire.

There were casualties on both sides, with four Harpers Ferry citizens killed, including the town’s mayor. A militia made up of men from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad arrived in town and assisted local residents in countering Brown’s attack.

Brown was forced to move his remaining men and their captives to the armory’s engine house, a smaller building that later became known as John Brown’s Fort. They effectively barricaded themselves inside.

The militia attack was able to free several of Brown’s captives, although eight of the railroad men died in the fighting. With no escape route and under heavy fire, Brown sent his son Watson out to surrender. However, the younger Brown was shot by the militia and mortally wounded.

Robert E. Lee and the Marines

Late in the afternoon of October 17, 1859, President James Buchanan ordered a company of Marines under the command of Brevet Colonel (and future Confederate General) Robert E. Lee to march into Harpers Ferry.

The next morning, Lee attempted to get Brown to surrender, but the latter refused. Ordering the Marines under his command to attack, the military men stormed John Brown's Fort, taking all of the abolitionist fighters and their captives alive.

In the end, John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry ended in failure.

John Brown's Body

Lee and his men arrested Brown and transported him to the courthouse in nearby Charles Town, where he was imprisoned until he could be tried. In November, a jury found Brown guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, at the age of 59. Among the witnesses to his execution were Lee and the actor and pro-slavery activist John Wilkes Booth . (Booth would later assassinate President Abraham Lincoln over the latter’s decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation .)

After he was executed, his wife, Mary Ann (Day) took John Brown's body to the family farm in upstate New York for burial. The farm and gravesite are owned by New York State and operated as the John Brown Farm State Historic Site , a National Historic Landmark.

Slavery would ultimately come to an end in the United States in 1865, six years after Brown’s death, following the Union’s defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War. Although Brown’s actions didn’t bring an end to slavery, they did spur those opposed to it to more aggressive action, perhaps fueling the bloody conflict that finally ended slavery in America.

American Battlefield Trust. “John Brown’s Harpers Ferry Raid.” Battlefields.org . Bordewich, F.M. (2009). “John Brown’s Day of Reckoning.” Smithsonianmag.com . “John Brown.” PBS.org .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

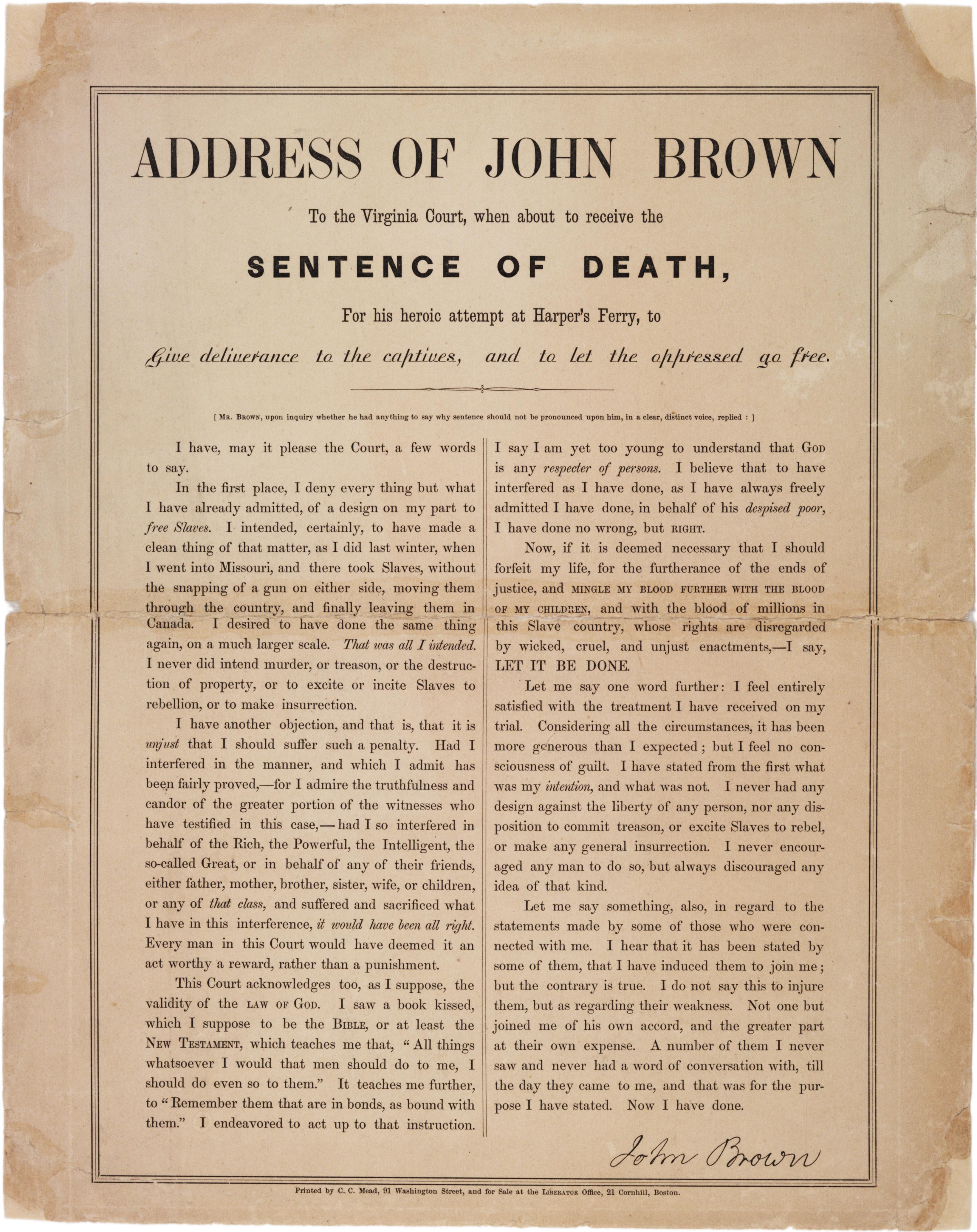

John Brown’s final speech, 1859

A spotlight on a primary source by john brown.

Brown’s plan soon went awry. Angry townspeople and local militia companies trapped his men in the armory. About twenty-four hours later, US troops commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived and stormed the engine house. Five of Brown’s party escaped, ten were killed, and seven, including Brown himself, were taken prisoner. Brown was tried in a Virginia court, although he had attacked federal property.

The trial’s high point came at its end when Brown was permitted to make a speech, which appears on this broadside printed in December 1859 by the abolitionist newspaper, the Liberator . In his address, Brown asserted that he "never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite Slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection," but rather wanted only to "free Slaves." He defended his actions as righteous and just, saying that "to have interfered as I have done—In behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong but right."

Brown also told the court that he was at peace with his actions and their consequences, proclaiming: “Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice and MINGLE MY BLOOD FURTHER WITH THE BLOOD OF MY CHILDREN, and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments—I submit; so LET IT BE DONE.”

Brown’s speech convinced many northerners that this grizzled man of fifty-nine was not an extremist but rather a martyr to the cause of freedom.

The Virginia court, however, found him guilty of treason, conspiracy, and murder, and he was sentenced to die. Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, and his body was buried on his family farm at North Elba, New York.

A full transcript is available.

In the first place, I deny every thing but what I have already admitted, of a design on my part to free Slaves. I intended, certainly, to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri, and there took Slaves, without the snapping of a gun on either side, moving them through the country, and finally leaving them in Canada. I desired to have done the same thing again, on a much larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite Slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction, examine the transcript, and the image, and apply your knowledge of American history in order to answer the questions that follow.

- Illustrations and descriptions of John Brown published in magazines and newspapers during his lifetime and following his execution frequently describe a fiery, violent, wild-eyed radical. How closely do those descriptions match the words in his speech?

- How did John Brown use Biblical scripture to explain and justify his actions?

- Why was it particularly appropriate that John Brown’s final statement to the court was reprinted in the Liberator ?

- Imagine that you are the prosecuting attorney for Virginia. Create a short final statement to the jury summarizing your reasons for bringing the case against John Brown.

- John Brown has been referred to by some as an honorable man and true patriot and by others as a radical terrorist. Which is most appropriate? Defend your answer using historical facts.

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Home — Essay Samples — History — Historical Figures — John Brown

Essays on John Brown

John brown essay topics for college students.

As a college student, choosing the right essay topic is crucial. It not only sets the tone for your entire paper but also allows you to explore your creativity and personal interests. This page aims to provide you with a variety of essay topics related to John Brown, ensuring that you find the perfect topic for your next assignment.

Essay Types and Topics

Argumentative essay topics.

- The impact of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry

- The role of violence in John Brown's abolitionist activities

- John Brown's legacy and its relevance in modern society

Paragraph Example:

An argumentative essay on John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry must carefully examine the historical context and the impact of this event on the abolitionist movement. As such, it is important to consider the various perspectives and debates surrounding this pivotal moment in American history. This essay seeks to provide a balanced analysis of the raid and its implications.

It is evident that John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry ignited intense debates about the moral and ethical implications of using violence to achieve social change. While opinions on Brown's actions remain divided, it is undeniable that his legacy continues to inspire discussions about the nature of activism and the pursuit of justice.

Compare and Contrast Essay Topics

- John Brown and Frederick Douglass: A comparative analysis

- The impact of John Brown's actions compared to other abolitionists

- John Brown's ideology versus other prominent figures in the abolitionist movement

Descriptive Essay Topics

- A day in the life of John Brown

- The landscapes and settings associated with John Brown's activities

- The emotional impact of John Brown's legacy on local communities

Persuasive Essay Topics

- Why John Brown should be celebrated as a hero

- The relevance of John Brown's principles in contemporary social justice movements

- Challenging misconceptions about John Brown's character and motivations

Narrative Essay Topics

- An eyewitness account of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry

- A fictional retelling of John Brown's life from the perspective of a supporter

- The impact of John Brown's legacy on future generations

Engagement and Creativity

When selecting an essay topic, consider your personal interests and the aspects of John Brown's life and impact that intrigue you the most. By choosing a topic that resonates with you, you can engage more deeply with the subject matter and produce a more compelling essay.

Educational Value

Each essay type offers unique opportunities for developing critical thinking and writing skills. Argumentative essays encourage you to analyze historical events and engage in persuasive writing, while descriptive essays allow you to hone your descriptive abilities. Compare and contrast essays help you develop analytical thinking, and narrative essays enable you to explore storytelling techniques and personal reflection.

John Brown Hero

John brown: a terrorist and a patriot, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Discussion on Whether John Brown Was a Terrorist

The life of john brown and his role in the anti-slavery movement, john brown – a slavery abolitionist with terrorist methods, john brown: the battle between martyr and madman, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Review of a Plea for John Brown by Henry David Thoreau

The life of john brown and his impact on civil rights movement, john brown's life and fight against slavery.

May 9, 1800

December 2, 1859 (aged 59)

Involvement in Bleeding Kansas; Raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Abolitionism

Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut. At young age, Brown witnessed an enslaved African American boy being beaten, that moment created his own abolitionism. Brown experienced great financial difficulties from the 1820s to the 1850s.

Brown established the League of Gileadites, a group for protecting Black citizens from slave hunters. Brown believed in using violent means to end slavery. In 1856, became involved in the conflict, known as Pottawatomie massacre.

In 1858, Brown liberated a group of enslaved people from a Missouri. By early 1859, Brown was leading raids to free enslaved people. In 1859, Brown led 21 men on a raid of the federal armory of Harpers Ferry in Virginia, but they were defeated by military forces led by Robert E. Lee. Brown was captured, and on November 2 he was sentenced to death.

Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, at the age of 59.

Six years after Brown’s death, slavery ultimately came to an end in the United States in 1865. Brown’s action helped to hasten the war that would bring emancipation.

Relevant topics

- Frederick Douglass

- Alexander Hamilton

- Harriet Tubman

- Mahatma Gandhi

- John Proctor

- Abigail Adams

- Anne Boleyn

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

John Brown | Summary and Analysis

Summary and analysis of john brown by bob dylan.

John Brown is an interesting anti-war lyric which describes the horrors of war and the ease with which young men find themselves trapped in one. The idea of being a hero in the battlefield is as tantalizing as it is fatal. This idea of heroism in often driven by a false sense of bravado and machismo which drives men to a situation where they find themselves “ a-tryin kill somebody or die tryin “. It is too late when they discover that all the power and glory is nothing more than political puppetry where the strings are pulled by powerful, interested players. This aspect is further explored in the summary and analysis of John Brown in the section John Brown Summar and Analysis.

John Brown uses colloquial diction to interrogate the ideas of war, honour and masculinity and show what happens when people go to fight a ‘ good old fashioned war ‘.

Got No Time? Check out this Quick Revision Infographic on our Facebook Page by clicking the link below.

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=848959309243734&substory_index=0&id=353002535506083&ref=bookmarks

John Brown | Analysis, Stanza 1

John Brown went off to war to fight on a foreign shore His mama sure was proud of him Hestood straight and tal in his uniform and all His mama’s face broke out all in a grin “Oh son, you look so fine, I’m glad you’re a son of mine You make me proud to know you hold a can Do what the captain says, lots of medals you will get And we’ll put them on the wall when you come home”

This lyric opens with a certain John Brown going off to fight “ a war on a foreign shore “. The name of the place of battle isn’t known. It isn’t even required anyway. A war is a war, wherever it maybe. Brown’s mother is happy to watch him hold a gun. She wants her son to bring home some medals which they can put up on the wall when he returns. That she is so sure of his return is indicative of either a motherly optimism for her son or a complete ignorance of the realities of war on her part. We come to know that the latter is actually the case by the time we reach the end.

The idea of ‘glory ‘ and the embodiment of it in the form of the medal in the imagination of the mother (and a large group of people) is emphasized right in the beginning of the lyric. This must be kept in mind when the soldier speaks out towards the end against the very idea of ‘glory’ and its physical embodiment in the form of medal seems to be nothing more a piece of metal.

John Brown | Analysis, Stanzas 2- 3

As that old train pulled out, John’s ma began to shout Tellin’ everyone in the neighbourhood “That’s my son that’s about to go, he’s a soldier now, you know” She made well sure her neighbours understood She got a letter once in a while and her face broke into a smile As she showed them to the people from next door And she bragged about her son with his uniform and gun And these things you called a good old-fashioned war Oh, good old-fashioned war! Then the letters ceased to come, for a long time they did not come They ceased to come about ten months or more Then a letter finally came saying, “Go down and meet the train Your son’s a-coming home from the war”

The son decides to fight the good old-fashioned war and his mum goes around telling everyone of her brave son. The romanticization of war and valour finds its expression in the mom’s treatment of the letter her son sends her. Not only does she treat the letter as a means of personal communication but also as a sign of his son’s valour and sacrifice – his red badge of courage. As often is the case, the letters cease to come and when she gets the message that her son has eventually returned, she rushes to meet him. At first she doesn’t see her son ( the readers know why) and is hardly able to believe her eyes when she does:

John Brown | Analysis, Stanza 4

Oh his face was all shot up and his hand was all blown off And he wore a metal brace around his waist He whispered kind of slow, in a voice she did not know While she couldn’t even recognise his face! Oh, lord, not even his face! “Oh tell me, my darling son, pray tell me what they done How is it you come to be this way?” He tried his best to talk but his mouth could hardly move And the mother had to turn her face away

The brutality of the war is all too evident. Dylan minces no words while providing the gruesome picture of a son whose “ face is all blown up ” and whose “ hand is all blown off ” and who has to wear a metal brace around his waist. The debilitating effects of the war and the long-term consequences of it is a sad reality which many war veterans have to deal with in their day-to-day lives after a good old-fashioned war . By the time John Brown returns, he has become a different man : one who is thoroughly disillusioned by the idea of heroism , one who can hardly move his mouth and whose mother can barely recognise him. What follows next is the condemnation of the idea of glory by the very person who was a constituent pawn in the making of it :

John Brown | Analysis, Stanza 5

Don’t you remember ma, when I went off to war You thought it was the best thing I could do? I was on the battleground you were home acting proud You wasn’t there standing in my shoes “ “Oh and I thought when I was there, God, what am I doing here? I’m a-tryin’ to kill somebody or die tryin’ But the thing that scared me the most was when my enemy came close and I saw that is face looked just like mine” Oh, lord, just like mine “ “And I couldn’t help but think, through the thunder rolling and stink That I was just a puppet in a play And through the roar and smoke this string is finally broke And a cannonball blew my eyes away.”

The soldier relates the brutality of the war where parents send off their children, not realising the full consequences of it. Far from being an arena for glory, it simply turns out to be a hell-hole where people spend their time “ tryin to kill somebody or die trying “. Above all, it is the rending away of humanity which is the most brutal component of war as it denies the humanity of the very people involved in it which is expressed by the narrator :

But the thing that scared me the most was

when my enemy came close

And I saw that his face looked just like mine”

The soldiers are mere puppets following their master’s order as a consequence of which soldiers like her son come home maimed, blinded and devastated. Some do not even return at all. The idea of glory and bravery are simply hollow words which act as the means of procuring cannon fodder :

As he turned away to walk, his ma was still in shock At seein’ the metal brace that helped him stand But as he turned to go, he called his mother close And he dropped his medal down into her hand.

His mother finally wakes to the shock and the horror of the gruesome realities of war when she sees her son unable to stand without the aid of the waist brace. She sees no glory, no bravery, only devastation.

However, as he walks away, he turns to his mother and drops into her hand all that the war was worth: some piece of metal. By the time we reach the end of the narrative, he is no longer the John Brown we saw we met at the first stanza . In fact, the first line is the only place where his name is explicitly mentioned . By the end, he is just another handicapped soldier who has been chewed up and spit out by the bloody system and is nothing more than a damaged good. The compensation : some stray piece of metal to hang on your wall as a useless showpiece.

John Brown | About the Author

Like a Rolling Stone, A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall, Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright , Blowing in the Wind… has been the ubiquitous folk singer-songwriter whose gruffy voice and robust lyrics can grip oneself in dimly lit alleyways and late night gigs when least expected. Born Robert Allen Zimmerman, the kid who got hold of his first guitar aged 14 went on to become one of the greatest song writers of his time.

Dylan released his first album in 1962 which didn’t receive much attention. However, it was The Freewheeling Bob Dylan in 1963 that made him “viral” before it was cool. The 60s saw his meteoric rise as the leading voice of protest music. Many of his popular songs like Masters of War , Hard Rain’s a gonna fall come from this period. His songs like Blowin’ in the Wind, Only a Pawn in their Game , The Times They are A-Changin’ were at the forefront of anti-war and Civil Rights movements. Mid 60s saw him gradually shift from folk to rock music, gaining a new fan base on one hand and drawing considerable ire from his ex-fans on the other. The 1965 Newport Folk Festival even saw him getting booed by his folk-fans in a grand folk-you gesture which was as ineffective as the hopeless pun you just read.

Dylan married Sara Lowndes in 1965, got in a near-fatal motorcycle accident in 1966 and made a comeback with Nashville Skyline in 1969, launching country rock as an altogether new genre. Like a boss.

A songwriter whose lyrics border on poetry, Dylan was one of the greatest artists to combine the realms of music and literature. He received three Grammys in 1988 and a special citation from Pulitzer Prize in 2008 . The jury for Spain’s Prince of Austrius Prize for Arts described him as a “ living myth in the history of popular music and a light for a generation that dreamt of changing the world “.

Dylan won the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming the first ever musician to do so.

The Darkling Thrush | Summary and Analysis

Birches by robert frost | summary and analysis, related articles, catch the moon summary.

To An Athlete Dying Young | Summary And Analysis

Brownies by zz packer | summary & analysis.

The Soul of Laploshka | Summary and Analysis

This helped a lot in my assignment. Thank you! 🙂

Such clarity in explanation ????

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Adblock Detected

John Brown and Self-Deception

Students will explor

Essential Question

- Why is self-deception destructive to a healthy civil society?

Guiding Questions

- When can an individual or a group justifiably decide to break the law?

- How can people become so deceived by ideas that they will commit horrific acts against others?

- How can one prevent themselves from being deceived by harmful ideas?

Learning Objectives

- Students will analyze the story of John Brown to identify examples of self-deception.

- Students will compare primary sources from John Brown and other historic examples to explain the dangers of self-deception in a civil society.

- Students will apply an understanding of the consequences of self-deception to their own behaviors.

Expand Materials Materials

Student resources, john brown and self-deception narrative.

- Primary Source Activity Handout and Graphic Organizer

- Scaffolded Primary Source Activity Handout and Graphic Organizer

Teacher Resources

- Analysis Questions

- Virtue in Action

- Journal Activity

- Sources for Further Reading

- Virtue Across the Curriculum

Expand Key Terms Key Terms

- Self-deception: Acting on a belief that a false idea or situation is true. Being deluded or deceived by ideas that endanger the humanity of others and movements that are unjust.

- Abolitionist: A person who favors the abolition of a practice or institution, such as slavery.

- Equivocate: To use unclear language, especially to deceive or mislead someone.

- Consecrate: To make or declare something sacred.

- Deceive: To make someone believe something that is not true.

- Popular sovereignty: A political policy under which residents of a territory voted on whether slavery would be allowed or not.

- Inciting: E ncourage or stir up (violent or unlawful behavior).

- Insurrection: A v iolent uprising against an authority or government.

- Oration: A formal speech.

- Sectionalism: Loyalty to one’s own region or section of the country, rather than to the country as a whole.

Expand More Information More Information

Procedures .

- The following lesson asks students to consider the vice of self-deception and how it can cause an individual to fail to act with integrity. Students will engage with the story of John Brown, as they consider the essential question: Why is self-deception destructive to a healthy civil society?

- The main activity in this lesson requires students to read and analyze a narrative that explores John Brown’s decisions that led him to self-deception. Students may work individually, in pairs, or small groups as best fits your classroom. The analysis questions provided can be used to help students comprehend and think critically about the content. As the teacher, you can decide which questions best fit your students’ needs and time restraints.

- The lesson includes a variety of activities and suggestions for your classroom. Time estimates are included in the activities, so that you can decide what’s most appropriate for your teaching.

- The excerpt from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” contains terminology that is no longer used because the terms are recognized to be offensive or derogatory. These terms are retained in their original usage in order to present them accurately in their historical context for student learning.

- Lastly, the lesson includes sources used in this lesson for further reading and suggestions for cross-curricular connections.

Expand Warmup Warmup

- Scaffolding Note : You may use this activity to prepare your students and introduce the vocabulary and ideas discussed in this lesson.

- Is it ever morally permissible to disobey the law? Explain your answer.

- Scaffolding Note: You may wish to have students write their response first, then share with a shoulder partner before leading a brief share-out with the class.

- Time estimate: 5 minutes

Expand Activities Activities

- Transition to the John Brown and Self-Deception Narrative . Students will learn and analyze the story of John Brown to understand how he fell for self-deception while trying to end slavery.

- Scaffolding Note: It may be helpful to instruct students to do a close reading of the text. Close reading asks students to read and reread a text purposefully to ensure students understand and make connections. For more detailed instructions on how to use close reading in your classroom, use these directions . Additional reading strategies are provided for other options that may meet your students’ needs.

- Equivocate: To use unclear language, especially to deceive or mislead someone.

- Consecrate: To make or declare something sacred.

- Deceive: To make someone believe something that is not true

- Popular sovereignty: A political policy under which residents of a territory voted on whether slavery would be allowed or not.

- Inciting: Encourage or stir up (violent or unlawful behavior).

- Insurrection: A violent uprising against an authority or government.

- Oration: A formal speech.

- Sectionalism: Loyalty to one’s own region or section of the country, rather than to the country as a whole.

- Scaffolding Note: If there are questions that are not necessary to your students’ learning or time restraints, then you can remove those questions.

- What ideals encouraged John Brown to dedicate his life to abolitionism?

- When John Brown dedicated his life to the destruction of slavery, what means did he use to achieve his goal? Were there other means at his disposal that were less violent? What other courses did abolitionists use to work for the end of slavery in the United States?

- What is the difference between acting according to uncompromising principles and acting according to the classical idea of prudence, or practical wisdom? Which course guided Brown, and did it benefit his cause?

- Why did John Brown move to Kansas? What actions against slavery did he take while he was there? Were his actions justified? Explain your answer.

- What was Brown’s plan to rid the country of slavery? Was it a realistic plan? Were there other alternatives that he could have pursued to help end slavery? Had he deluded himself into thinking that it was the right and only path? Explain your answers.

- Did the raid on Harper’s Ferry go according to plan? Were innocent people swept up in the violence and lost their lives? Did Brown consider the loss of life tragic or necessary to achieve his goals? Explain your answer.

- Did Brown express any remorse for killing people or breaking the law? Did his righteous vision cloud his judgment regarding the rightness or wrongness of his actions? Explain your answer.

- Did Brown consider the consequences of his raid for human lives? Did he consider the consequences if he had actually succeeded in raiding Harper’s Ferry and starting a race war in the South? Did he consider the consequences of fueling tensions between the North and South because of his violent plan? Explain your answers.

- Why was John Brown considered by some to be a hero and by some to be a villain? Why is his life and legacy still debated as a hero or villain?

Estimated time: 50 minutes

- Students will read statements from John Brown, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr. Then students will complete the following graphic organizer related to Brown, Lincoln and King’s views on just and unjust laws.

- Scaffolding Note: A scaffolded version of the primary sources is also available with shorter excerpts and space for note-taking. Scaffolded Primary Source Activity Handout and Graphic Organizer

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Expand Wrap Up Wrap Up

Assess & reflect, virtue in action .

- How can you be mindful to avoid self-deception while remaining true to your values?

- Scaffolding note: Use the concentric circles discussion strategy for this discussion. This strategy involves students standing in two concentric circles facing one another and responding to a question in a paired discussion. When prompted by the teacher, one of the circles rotates so each student now faces a new partner.

- Estimated time: 10 minutes

Self-Deception Journal Activity

- President Abraham Lincoln was strongly dedicated to the principle of natural rights for all human beings. Although the abolitionists pressed for immediate action, Lincoln was also firmly dedicated to the constitutional rule of law and would not break it to do what was right. The Emancipation Proclamation (1863) demonstrated that Lincoln wanted the slaves to be free while acting under presidential authority in the Constitution.

- Compare and contrast the goals and methods of John Brown and Abraham Lincoln. Did Brown or Lincoln demonstrate the virtue of prudence, or practical wisdom, in achieving his goal?

Expand Extensions Extensions

Sources & further reading .

- Carlton, Evan. Patriotic Treason. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- Horowitz, Tony. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War. New York: Henry Holt, 2011.

- Oates, Stephen. To Purge This Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1984.

- Peterson, Merrill D. John Brown: The Legend Revisited. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002.

- Reynolds, David. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Knopf, 2005.

Virtue Across the Curriculum

- Playwright Robert Bold dramatizes the struggle between King Henry VIII of England and his chancellor Thomas More. How does Thomas More preserve both his moral conscience and his dedication to the rule of law? What sacrifice does More and his family make for his obedience to conscience and law? How do More and his daughter, Margaret, demonstrate great courage? Note: The 1966 film version of this play is rated G.

- Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau wrote this essay as a response to the Mexican-American war and the abhorrence of slavery. According to Thoreau, what is the relationship between one’s personal integrity or conscience and the law?

- Protesting the treatment of Indians in South Africa https://bit.ly/42E3hbA

- Explaining his tactics for fighting British rule in India https://bit.ly/43Q6YMn

- A nonviolent protest at a salt mine https://bit.ly/3P6KTVx

- Lincoln (2012), Directed by Ste ph v en Spielberg

- Plato, Crito

- Mark Twain, Joan of Arc

Student Handouts

John brown and self-deception primary source analysis, john brown and self-deception scaffolded primary source, john brown’s last speech, 1859, related resources.

John Brown and Harpers Ferry

Was John Brown a righteous crusader or violent radical?

John Brown: Hero or Villain? DBQ

Use this Lesson alongside theJohn Brown and Harpers Ferry Narrative to allow students to fully evaluate John Brown's approach to abolitionism. Facilitation Notes: Use available classroom technology to display a United States map so that they are within view throughout the lesson. Also, write theKey Questionon the board so that it is in view throughout the lesson.

John Brown: APUSH Topics to Study for Test Day

John Brown was a radical abolitionist who believed that the only way to abolish slavery was to arm slaves and to spur their insurrection. To successfully respond to John Brown APUSH questions, it is important to know the effects John Brown’s actions had on pro and antislavery voices, and to look especially at his raid on Harpers Ferry.

Who is John Brown?

John Brown was a northern abolitionist who moved about the country supporting antislavery causes, which included giving land to fugitive slaves and participating in the Underground Railroad. He was unsatisfied with the results of the peaceful protests of the mainstream abolitionist movement and became a violent radical for the cause. In 1855, Brown and his sons moved to Kansas where they took part in guerrilla warfare during the Bleeding Kansas crisis, murdering five pro-slavery settlers.

John Brown’s actions in Kansas brought him national attention. He moved to Virginia and began hatching an elaborate plot to fund an army that would raid Harpers Ferry , arm slaves, and begin an uprising. Brown led 21 men on his raid, where they attacked and occupied the federal armory for two days. Brown’s army was surrounded and many of his men were killed. Brown himself was eventually captured, charged of murder, conspiring, and treason, and hanged.

Important years to note for John Brown:

- 1856: John Brown murders five proslavery settlers in Kansas during the Bleeding Kansas crisis

- 1859: John Brown raids Harpers Ferry

Why is John Brown so important?

John Brown was a divisive figure. His ideas attracted many abolitionists who were no longer content with the institution of slavery and grew impatient for emancipation. He remained, however, a radical figure, and his methods, especially after the Harpers Ferry attack, were condemned by mainstream abolitionists. Southern Democrats and other pro-slavery Americans, however, were convinced that Brown was acting on the behest of Republicans, and that his Harpers Ferry raid was just the beginning of an advanced abolitionist plot to overthrow the system of slavery. John Brown’s actions likely hastened the coming of war, as they emboldened northern abolitionists and convinced those with an interest in slavery that if republicans took control of the government slavery in the South would be ended.

What are some historical people and events related to John Brown?

- Bleeding Kansas: The crisis that followed the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Fighting ensued as Kansas citizens fought over whether or not the territory would be a free or slave state.

- Robert E. Lee: Led the military forces that captured Brown at Harpers Ferry.

What example question about John Brown might come up on the APUSH exam?

“The newspapers seem to ignore, or perhaps are really ignorant of the fact, that there are at least as many as two or three individuals to a town throughout the North who think much as the present speaker does about him and his enterprise. I do not hesitate to say that they are an important and growing party. We aspire to be something more than stupid and timid chattels, pretending to read history and our Bibles, but desecrating every house and every day we breathe in. Perhaps anxious politicians may prove that only seventeen white men and five Negroes were concerned in the late [raid on Harpers Ferry]; but their very anxiety to prove this might suggest to themselves that all is not told. Why do they still dodge the truth? They are so anxious because of a dim consciousness of the fact, which they do not distinctly face, that at least a million of the free inhabitants of the United States would have rejoiced if it had succeeded. They at most only criticize the tactics.” -“A Plea for Captain John Brown” by Henry David Thoreau, 1859 ( Source ) Thoreau’s assessment of Harpers Ferry seems to support A) the Democrats’ assertion that slavery should be a matter of popular sovereignty. B) the Republicans’ conviction that John Brown’s actions were fair and just. C) the South’s fears that the North aimed not to contain slavery, but to end it. D) the North’s concern that the South would secede over John Brown’s actions.

The correct answer is (C). After John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Southern Democrats and others with a stake in the institution of slavery feared that it was a sign of the insurrection to come. Republicans insisted that they did not condone Brown’s actions, but abolitionists like Thoreau came out in support of Brown and stoked the South’s fears that, should the northern Republicans win Congress and the White House, slavery would be ended.

Sarah is an educator and writer with a Master’s degree in education from Syracuse University who has helped students succeed on standardized tests since 2008. She loves reading, theater, and chasing around her two kids.

View all posts

More from Magoosh

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Witnesses and Testimony at the Trial of John Brown

The Trial of John Brown Charlestown, Virginia October 25 to November 2, 1859

From “The Life, Trial and Execution of Captain John Brown, Known as “Old Brown of Ossawatomie,” with a Full Account of the Attempted Insurrection at Harpers Ferry”. New York: Robert M.De Witt, Publisher, 1859

Oct. 25, 1859.

The Circuit Court of Jefferson County, Judge Richard Parker on the bench, assembled at two o'clock. The Grand Jury were called, and the Magistrate's Court reported the result of the examination in the case of Capt. Brown and the other prisoners. The Grand Jury retired with the witnesses for the State. At five o'clock they returned into Court and stated that they had not finished the examination of witnesses, and they were therefore discharged until ten o'clock to-morrow morning. It is rumored that Brown is desirous of making a full statement of his motives and intentions, through the press, but the Court has refused all further access to him by reporters, fearing that be may put forth something calculated to influence the public mind, and to have a bad effect upon slaves, The mother of Cook's wife was in the Court House throughout the examination.

Coffee says that he had a brother in the party, and that Brown had three sons in it. Also that there were two other persons, named Taylor and Hazlitt, engaged, so that, numbering Cook, five have escaped, twelve were killed, and five captured, making twenty-two in all.

Capt. Brown's object in refusing the aid of counsel is, that if he has counsel he will not be allowed to speak himself, and Southern counsel will not be willing to express his views.

The reason given for hurrying the trial, is, that the people of the whole country are kept in a state of excitement, and a large armed force is required to prevent attempts at rescue.

The prisoners, as brought into the Court, presented a pitiable sight --Brown and Stephens being unable to stand without assistance. Brown has three sword-stabs in his body, and one saber-cut over the heart. Stephens has three balls in his head, and had two in his breast and one in his arm. He was also cut on the forehead with a rifle bullet, which glanced off leaving a bad wound.

Oct. 26, 1859.

Brown has made no confession; but, on the contrary, says he has full confidence in the goodness of God, and is confident that he will rescue him from the perils that surround him. He says he has had rifles leveled at him, knives at his throat, and his life in as great peril as it now is, but that God has always been at his side. He knows God is with him, and fears nothing.

Alex. R. Boteler, member elect for Congress of this district, has collected from 50 to 100 letters from the citizens of the neighborhood of Brown's house, who searched it before the arrival of the marines. The letters are in the possession of Andrew Hunter, Esq., who has a large number of letters obtained from Brown's house by the marines and other parties. Among them is a roll of the conspirators, containing forty-seven signatures; an accurately traced map from Chambersburg to Brown's house; copies of letters from Brown, stating that as the arrival of too many men at once would excite suspicion, they should arrive singly; a letter from Merriam, stating that of the twenty thousand wanted, G. S. was good for one-fifth; also a letter from J. E. Cook, stating that the Maryland election was about to come off, the people will become excited, and we will get some of the candidates that will join our side.