An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ann Glob Health

- v.85(1); 2019

The Manila Declaration on the Drug Problem in the Philippines

Nymia simbulan.

1 University of Southern California, US

Leonardo Estacio

Carissa dioquino-maligaso, teodoro herbosa, mellissa withers.

2 University of the Philippines, PH

When Philippine President Rodrigo R. Duterte assumed office in 2016, his government launched an unprecedented campaign against illegal drugs. The drug problem in the Philippines has primarily been viewed as an issue of law enforcement and criminality, and the government has focused on implementing a policy of criminalization and punishment. The escalation of human rights violations has caught the attention of groups in the Philippines as well as the international community. The Global Health Program of the Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU), a non-profit network of 50 universities in the Pacific Rim, held its 2017 annual conference in Manila. A special half-day workshop was held on illicit drug abuse in the Philippines which convened 167 participants from 10 economies and 21 disciplines. The goal of the workshop was to collaboratively develop a policy statement describing the best way to address the drug problem in the Philippines, taking into consideration a public health and human rights approach to the issue. The policy statement is presented here.

When Philippine President Rodrigo R. Duterte assumed office on June 30, 2016, his government launched an unprecedented campaign against illegal drugs. He promised to solve the illegal drug problem in the country, which, according to him, was wreaking havoc on the lives of many Filipino families and destroying the future of the Filipino youth. He declared a “war on drugs” targeting users, peddlers, producers and suppliers, and called for the Philippine criminal justice system to put an end to the drug menace [ 1 ].

According to the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) (the government agency mandated to formulate policies on illegal drugs in the Philippines), there are 1.8 million current drug users in the Philippines, and 4.8 million Filipinos report having used illegal drugs at least once in their lives [ 2 ]. More than three-quarters of drug users are adults (91%), males (87%), and have reached high school (80%). More than two-thirds (67%) are employed [ 2 ]. The most commonly used drug in the Philippines is a variant of methamphetamine called shabu or “poor man’s cocaine.” According to a 2012 United Nations report, the Philippines had the highest rate of methamphetamine abuse among countries in East Asia; about 2.2% of Filipinos between the ages 16–64 years were methamphetamines users.

The drug problem in the Philippines has primarily been viewed as an issue of law enforcement and criminality, and the government has focused on implementing a policy of criminalization and punishment. This is evidenced by the fact that since the start of the “war on drugs,” the Duterte government has utilized punitive measures and has mobilized the Philippine National Police (PNP) and local government units nationwide. With orders from the President, law enforcement agents have engaged in extensive door-to-door operations. One such operation in Manila in August 2017 aimed to “shock and awe” drug dealers and resulted in the killing of 32 people by police in one night [ 3 ].

On the basis of mere suspicion of drug use and/or drug dealing, and criminal record, police forces have arrested, detained, and even killed men, women and children in the course of these operations. Male urban poor residents in Metro Manila and other key cities of the country have been especially targeted [ 4 ]. During the first six months of the Duterte Presidency (July 2016–January 2017), the PNP conducted 43,593 operations that covered 5.6 million houses, resulting in the arrest of 53,025 “drug personalities,” and a reported 1,189,462 persons “surrendering” to authorities, including 79,349 drug dealers and 1,110,113 drug users [ 5 ]. Government figures show that during the first six months of Duterte’s presidency, more than 7,000 individuals accused of drug dealing or drug use were killed in the Philippines, both from legitimate police and vigilante-style operations. Almost 2,555, or a little over a third of people suspected to be involved in drugs, have been killed in gun battles with police in anti-drug operations [ 5 , 6 ]. Community activists estimate that the death toll has now reached 13,000 [ 7 ]. The killings by police are widely believed to be staged in order to qualify for the cash rewards offered to policeman for killing suspected drug dealers. Apart from the killings, the recorded number of “surrenderees” resulting in mass incarceration has overwhelmed the Philippine penal system, which does not have sufficient facilities to cope with the population upsurge. Consequently, detainees have to stay in overcrowded, unhygienic conditions unfit for humans [ 8 ].

The escalation of human rights violations, particularly the increase in killings, both state-perpetrated and vigilante-style, has caught the attention of various groups and sectors in society including the international community. Both police officers and community members have reported fear of being targeted if they fail to support the state-sanctioned killings [ 9 ]. After widespread protests by human rights groups, Duterte called for police to shoot human rights activists who are “obstructing justice.” Human Rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have said that Duterte’s instigation of unlawful police violence and the incitement of vigilante killings may amount to crimes against humanity, violating international law [ 10 , 11 ]. The European Union found that human rights have deteriorated significantly since Duterte assumed power, saying “The Philippine government needs to ensure that the fight against drug crimes is conducted within the law, including the right to due process and safeguarding of the basic human rights of citizens of the Philippines, including the right to life, and that it respects the proportionality principle [ 12 ].” Despite the fact that, in October 2017, Duterte ordered the police to end all operations in the war on drugs, doubts remain as to whether the state-sanctioned killings will stop [ 13 ]. Duterte assigned the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) to be the sole anti-drug enforcement agency.

Duterte’s war on drugs is morally and legally unjustifiable and has created large-scale human rights violations; and is also counterproductive in addressing the drug problem. International human rights groups and even the United Nations have acknowledged that the country’s drug problem cannot be resolved using a punitive approach, and the imposition of criminal sanctions and that drug users should not be viewed and treated as criminals [ 14 ]. Those critical of the government’s policy towards the illegal drug problem have emphasized that the drug issue should be viewed as a public health problem using a rights-based approach (RBA). This was affirmed by UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon on the 2015 International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illegal Trafficking when he stated, “…We should increase the focus on public health, prevention, treatment and care, as well as on economic, social and cultural strategies [ 15 ].” The United Nations Human Rights Council released a joint statement in September 2017, which states that the human rights situation in the Philippines continued to cause serious concern. The Council urged the government of the Philippines to “take all necessary measures to bring these killings to an end and cooperate with the international community to pursue appropriate investigations into these incidents, in keeping with the universal principles of democratic accountability and the rule of law [ 16 ].” In October 2017, the Philippines Dangerous Drug Board (DDB) released a new proposal for an anti-drug approach that protects the life of the people. The declaration includes an implicit recognition of the public health aspect of illegal drug use, “which recognizes that the drug problem as both social and psychological [ 16 ].”

Workshop on Illicit Drug Abuse in the Philippines

The Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU) is a non-profit network of 50 leading research universities in the Pacific Rim region, representing 16 economies, 120,000 faculty members and approximately two million students. Launched in 2007, the APRU Global Health Program (GHP) includes approximately 1,000 faculty, students, and researchers who are actively engaged in global health work. The main objective of the GHP is to advance global health research, education and training in the Pacific Rim, as APRU member institutions respond to global and regional health challenges. Each year, about 300 APRU GHP members gather at the annual global health conference, which is hosted by a rotating member university. In 2017, the University of the Philippines in Manila hosted the conference and included a special half-day workshop on illicit drug abuse in the Philippines.

Held on the first day of the annual APRU GHP conference, the workshop convened 167 university professors, students, university administrators, government officials, and employees of non-governmental organizations (NGO), from 21 disciplines, including anthropology, Asian studies, communication, dentistry, development, education, environmental health, ethics, international relations, law, library and information science, medicine, nutrition, nursing, occupational health, pharmaceutical science, physical therapy, political science, psychology, public health, and women’s studies. The participants came from 10 economies: Australia, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Nepal, the Philippines, Thailand, and the US. The special workshop was intended to provide a venue for health professionals and workers, academics, researchers, students, health rights advocates, and policy makers to: 1) give an overview on the character and state of the drug problem in the Philippines, including the social and public health implications of the problem and the approaches being used by the government in the Philippines; 2) learn from the experiences of other countries in the handling of the drug and substance abuse problem; and 3) identify appropriate methods and strategies, and the role of the health sector in addressing the problem in the country. The overall goal of the workshop was to collaboratively develop a policy statement describing the best way to address this problem in a matnner that could be disseminated to all the participants and key policymakers both in the Philippines, as well as globally.

The workshop included presentations from three speakers and was moderated by Dr. Carissa Paz Dioquino-Maligaso, head of the National Poison Management and Control Center in the Philippines. The first speaker was Dr. Benjamin P. Reyes, Undersecretary of the Philippine Dangerous Drugs Board, who spoke about “the State of the Philippine Drug and Substance Abuse Problem in the Philippines.” The second speaker was Dr. Joselito Pascual, a medical specialist from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, at the University of the Philippines General Hospital in Manila. His talk was titled “Psychotropic Drugs and Mental Health.” The final speaker was Patrick Loius B. Angeles, a Policy and Research Officer of the NoBox Transitions Foundation, whose talk was titled “Approaches to Addressing the Drug and Substance Abuse Problem: Learning from the Experiences of Other Countries.” Based on the presentations, a draft of the Manila Declaration on the Drug Problem in the Philippines was drafted by the co-authors of this paper. The statement was then sent to the workshop participants for review and comments. The comments were reviewed and incorporated into the final version, which is presented below.

Declaration

“Manila Statement on the Drug Problem in the Philippines”

Gathering in this workshop with a common issue and concern – the drug problem in the Philippines and its consequences and how it can be addressed and solved in the best way possible;

Recognizing that the drug problem in the Philippines is a complex and multi-faceted problem that includes not only criminal justice issues but also public health issues and with various approaches that can be used in order to solve such;

We call for drug control policies and strategies that incorporate evidence-based, socially acceptable, cost-effective, and rights-based approaches that are designed to minimize, if not to eliminate, the adverse health, psychological, social, economic and criminal justice consequences of drug abuse towards the goal of attaining a society that is free from crime and drug and substance abuse;

Recognizing, further, that drug dependency and co-dependency, as consequences of drug abuse, are mental and behavioral health problems, and that in some areas in the Philippines injecting drug use comorbidities such as the spread of HIV and AIDS are also apparent, and that current prevention and treatment interventions are not quite adequate to prevent mental disorders, HIV/AIDS and other co-morbid diseases among people who use drugs;

Affirming that the primacy of the sanctity/value of human life and the value of human dignity, social protection of the victims of drug abuse and illegal drugs trade must be our primary concern;

And that all health, psycho-social, socio-economic and rights-related interventions leading to the reduction or elimination of the adverse health, economic and social consequences of drug abuse and other related co-morbidities such as HIV/AIDS should be considered in all plans and actions toward the control, prevention and treatment of drug and substance abuse;

As a community of health professionals, experts, academics, researchers, students and health advocates, we call on the Philippine government to address the root causes of the illegal drug problem in the Philippines utilizing the aforementioned affirmations . We assert that the drug problem in the country is but a symptom of deeper structural ills rooted in social inequality and injustice, lack of economic and social opportunities, and powerlessness among the Filipino people. Genuine solutions to the drug problem will only be realized with the fulfillment and enjoyment of human rights, allowing them to live in dignity deserving of human beings. As members of educational, scientific and health institutions of the country, being rich and valuable sources of human, material and technological resources, we affirm our commitment to contribute to solving this social ill that the Philippine government has considered to be a major obstacle in the attainment of national development.

The statement of insights and affirmations on the drug problem in the Philippines is a declaration that is readily applicable to other countries in Asia where approaches to the problem of drug abuse are largely harsh, violent and punitive.

As a community of scholars, health professionals, academics, and researchers, we reiterate our conviction that the drug problem in the Philippines is multi-dimensional in character and deeply rooted in the structural causes of poverty, inequality and powerlessness of the Filipino people. Contrary to the government’s position of treating the issues as a problem of criminality and lawlessness, the drug problem must be addressed using a holistic and rights-based approach, requiring the mobilization and involvement of all stakeholders. This is the message and the challenge which we, as members of the Association of Pacific Rim Universities, want to relay to the leaders, policymakers, healthcare professionals, and human rights advocates in the region; we must all work together to protect and promote health and well being of all populations in our region.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A World Court Inches Closer To A Reckoning In The Philippines' War On Drugs

Julie McCarthy

Relatives and friends mourn during Lilibeth Valdez's funeral on June 4 in Manila, Philippines. An off-duty police officer was seen pulling the hair of 52-year-old Valdez, before shooting her dead. The former chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court recommended the court open an investigation into alleged crimes against humanity committed during President Rodrigo Duterte's drug war. Ezra Acayan/Getty Images hide caption

Relatives and friends mourn during Lilibeth Valdez's funeral on June 4 in Manila, Philippines. An off-duty police officer was seen pulling the hair of 52-year-old Valdez, before shooting her dead. The former chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court recommended the court open an investigation into alleged crimes against humanity committed during President Rodrigo Duterte's drug war.

After years of a deadly counternarcotics campaign that has riven the Philippines, the International Criminal Court is a step closer to opening what international law experts say would be its first case bringing crimes against humanity charges in the context of a drug war.

On June 14, the last day of her nine-year term as the ICC's chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda announced there was "a reasonable basis to believe that the crime against humanity of murder" had been committed in the war on drugs carried out under the government of President Rodrigo Duterte. Bensouda urged the court to open a full-scale investigation into the bloody crackdown between July 1, 2016, when Duterte took office, and March 16, 2019, when the Philippines' withdrawal from the ICC took effect.

Said at first to be unfazed by the prosecutor's findings of alleged murder under his watch, Duterte went on to rail against the international court in his June 21 "Talk to the People," vowing, in an invective-filled rant, never to submit to its jurisdiction. "This is bulls***. Why would I defend or face an accusation before white people? You must be crazy," Duterte scoffed. (The 18 judges on the ICC are an ethnically diverse group from around the world . And Bensouda, from Gambia, is the first female African to serve as the court's chief prosecutor.)

The drug war has been a signature policy of President Duterte's administration, and its brutality has drawn international condemnation. But for years the world has stood by as allegations of human rights violations accumulated, and Duterte barred international investigators. The findings of the chief prosecutor represent the most prominent record to date of the killings committed under the Philippines' anti-narcotics campaign and set the stage for a potential legal reckoning for its perpetrators.

"It wasn't a rushed decision," Manila-based human rights attorney Neri Colmenares says of Bensouda's three years of examination, which "makes the case stronger." He says, "It is not yet justice, but it is a major step toward that."

The prosecutor's findings

Bensouda's final report says the nationwide anti-drug campaign deployed "unnecessary and disproportionate" force. The information the prosecutor gathered suggests "members of Philippine security forces and other, often associated, perpetrators deliberately killed thousands of civilians suspected to be involved in drug activities." The report cites Duterte's statements encouraging law enforcement to kill drug suspects, promising police immunity, and inflating numbers, claiming there were variously "3 million" and "4 million" addicts in the Philippines. The government itself puts the figures of drug users at 1.8 million.

Fatou Bensouda speaks during an interview with The Associated Press in The Hague, Netherlands, June 14, before ending her nine-year tenure as chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court. Peter Dejong/AP hide caption

Fatou Bensouda speaks during an interview with The Associated Press in The Hague, Netherlands, June 14, before ending her nine-year tenure as chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court.

The Philippines' Drug Enforcement Agency reports more than 6,100 drug crime suspects have been killed in police operations since Duterte became president. But Bensouda says, "Police and other government officials planned, ordered, and sometimes directly perpetrated" killings outside official police operations. Independent researchers estimate the drug war's death toll, including those extrajudicial killings, could be as high as 12,000 to 30,000 .

The international court's now former prosecutor based her findings on evidence gathered in part from families of slain suspects, their testimonials redacted from her report to protect their identities. She cited rights groups such as Amnesty International that detailed how police planted evidence at crime scenes, fabricated official reports, and pilfered belongings from victims' homes.

Colmenares, who is a former congressman, says the police appeared to have a modus operandi. "Sometimes the police would go into the house and segregate the family from the father or the son, and then later on the father and the son would be killed. The witnesses say that the husband was already kneeling or raising their hand," he says.

Colmenares says in the prevailing atmosphere of impunity in the Philippines, families are "courageous" for bearing witness.

Police self-defense debunked

Police have justified the killings by saying that the suspects put up a struggle, requiring the use of deadly force, a scenario they call nanlaban . Duterte himself said last week, "We kill them because they fight back." Duterte fears that if drastic measures were not taken, the Philippines could wind up in the sort of destabilizing narco-conflict that afflicts Mexico. "What will then happen to my country?"

Bensouda rejects police claims that they acted in self-defense, citing witness testimony, and findings of rights groups such as Amnesty International .

In February, the Philippines' own Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra conceded to the United Nations Human Rights Council that the police's nanlaban argument is often deeply flawed. His ministry had reviewed many incident reports where police said suspects were killed in shootouts. "Yet, no full examination of the weapon recovered was conducted. No verification of its ownership was undertaken. No request for ballistic examination or paraffin test was pursued," he said .

Supporters of Kian delos Santos attend a vigil on Nov. 29, 2018, outside a Manila police station where officers thought to be involved in the teenager's killing were assigned. Three Philippine policemen were sentenced to decades in prison for murdering delos Santos during an anti-narcotics sweep. Noel Celis/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Supporters of Kian delos Santos attend a vigil on Nov. 29, 2018, outside a Manila police station where officers thought to be involved in the teenager's killing were assigned. Three Philippine policemen were sentenced to decades in prison for murdering delos Santos during an anti-narcotics sweep.

Despite that, only a single case has resulted in the prosecution and conviction of three police officers for the murder of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos in August 2017, after the incident sparked national outrage. Police accused delos Santos, a student, of being a drug-runner, a charge his family denied. When the teenager was found dead in an alley, police said they had killed him in self-defense. CCTV footage contradicted the police version of events.

"Duterte Harry"

Bensouda buttresses her case by citing Duterte's 22 years as mayor of Davao City on the island of Mindanao, where her report says he "publicly supported and encouraged the killing of petty criminals and drug dealers," ostensibly to enforce discipline on a city besieged by crime, a communist rebellion, and an active counterinsurgency campaign .

Over 120,000 People Remain Displaced 3 Years After Philippines' Marawi Battle

Former police officials testified to the existence of a death squad that acted on the orders of then-Mayor Duterte and which rights groups allege carried out more than 1,400 killings .

Bensouda's report says Duterte's central focus on fighting crime and drug use earned him monikers such as " The Punisher " and " Duterte Harry ," and in 2016 he rode that strongman image to the presidency in a country that had been battling drug syndicates for decades and was weary of crime.

A policeman comes out of the shanty home of two brothers and an unidentified man who were killed during an operation as part of the continuing war on drugs in Manila, Philippines, Oct. 6, 2016. Aaron Favila/AP hide caption

A policeman comes out of the shanty home of two brothers and an unidentified man who were killed during an operation as part of the continuing war on drugs in Manila, Philippines, Oct. 6, 2016.

In a 2016 address to the national police, he warned drug criminals who would harm the nation's sons and daughters: "I will kill you, I will kill you. I will take the law into my own hands. ... Forget about the laws of men, forget about the laws of international order."

American University international law professor Diane Orentlicher says the ICC prosecutor reached back to the ultra-aggressive approach Duterte first deployed in Davao City to show that "there were the same kind of summary executions earlier in the Philippines." Orentlicher says it identifies "continuity of certain patterns" and the threat they pose "over almost a quarter of a century."

Obstacles ahead

While the finding of possible crimes against humanity is a significant step in the ICC's scrutiny, formidable hurdles remain before any prosecutor could formally name perpetrators or issue indictments.

Goats and Soda

Looking for a bed for daddy lolo: inside the philippines' covid crisis.

Firstly, President Duterte denies any wrongdoing, unambiguously vows not to cooperate in an international court investigation, and could stonewall the effort in his last year in office. And despite the bloodshed, and mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic , Duterte's " crude everyman " image still appeals to a majority of Filipinos.

Orentlicher says building a crimes against humanity case is complex, involving potentially thousands of victims "over time [and] over territory." While human rights activists would like to see Duterte in the dock, linking the alleged crimes to individual perpetrators is a massive evidentiary undertaking.

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte delivers a speech in Quezon City, Philippines, on June 25. Ace Morandante/Malacanang Presidential Photographers Division via AP hide caption

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte delivers a speech in Quezon City, Philippines, on June 25.

Powerful leaders facing scrutiny, she says, have been able to "interfere with witnesses, obstruct justice [and] intimidate people who would be key sources for the prosecutor." While the most senior officials are the ones the public expects the world court to take on, Orentlicher says they "are in the best position to keep a prosecutor from getting the evidence."

David Bosco, author of a book about the International Criminal Court titled Rough Justice, says it's also entirely possible the judges may not authorize an investigation. Bosco says it would not be because the Philippine case lacks merit, rather he says the plethora of allegations involving possible war crimes from Afghanistan to Nigeria to the Gaza Strip has the court overstretched.

"And even if the judges were to authorize an investigation, then you're talking about trying to launch an investigation when you have a hostile government," Bosco says. "So I think this is a very long road before we get to any perpetrator seeing the inside of a courtroom."

But Bosco adds prosecutors who have opened an ICC investigation have also been content to have the case lie dormant for long periods.

Why Rights Groups Worry About The Philippines' New Anti-Terrorism Law

"And then they revive," he says. "And so, we shouldn't ignore the possibility that there could be political changes in the Philippines that suddenly make a new government much more amenable to cooperating. So things could change."

Bosco says a potential investigation of the Philippines is also important because it raises the critical question: whether a state that has joined the ICC and then subsequently has come under scrutiny can "immunize itself by leaving the court." As the chief prosecutor persisted in examining the country's drug war, the Philippines withdrew as a member of the ICC.

Bosco believes the fact Bensouda sought authorization for her successor to open an investigation into the Philippines is "an important signal that the court is still going to pursue countries that have left the ICC once they've come under scrutiny."

Orentlicher says the court may look to the case of Burundi, the first country to leave the ICC. Prosecutors have continued to investigate alleged crimes against humanity committed in the country before it withdrew in 2017.

Decades of drug wars

The focus on the Philippines comes at a time when countries around the world are questioning heavy-handed counternarcotics tactics. That includes the United States, whose war on drugs dates back to at least 1971 when President Richard Nixon called for an "all-out offensive" against drug abuse and addiction.

The War On Drugs: 50 Years Later

"Over the last 50 years, we've unfortunately seen the 'War on Drugs' be used as an excuse to declare war on people of color, on poor Americans and so many other marginalized groups," New York Attorney General Letitia James said .

Likewise, the former ICC chief prosecutor Bensouda notes that the Philippines' drug fight has been called a "war on the poor" as the most affected group "has been poor, low-skilled residents of impoverished urban areas."

Drug addiction, especially crystal meth, known locally as shabu , grips the Philippines. Just this month, the national police said that security forces have been "seizing large volumes of shabu left and right," an acknowledgment that drugs remain rampant five years into the brutal drug war.

An aerial view shows Filipinos observing social distancing as they take part in a protest against President Duterte's anti-terrorism bill on June 12, 2020, in Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines. Critics says the legislation gives the state power to violate due process, privacy and other basic rights of Filipino citizens. Ezra Acayan/Getty Images hide caption

An aerial view shows Filipinos observing social distancing as they take part in a protest against President Duterte's anti-terrorism bill on June 12, 2020, in Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines. Critics says the legislation gives the state power to violate due process, privacy and other basic rights of Filipino citizens.

Calls are mounting for greater attention to drug prevention and public health for drug users. "Heavy suppression efforts marked by extra-judicial killings and street arrests were not going to slow down demand," Jeremy Douglas, Southeast Asia representative for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, told Reuters .

Edcel C. Lagman, a long-serving member of the Philippine Congress, recently wrote in the Manila Times that the ammunition needed in this war includes drug-abuse prevention education, skill training and "well-funded health interventions" to "reintegrate former drug dependent into society."

The Philippine National Police's narcotics chief himself, Col. Romeo Caramat, acknowledged that the violent approach to curbing illicit drugs has not been effective. "Shock and awe definitely did not work," he told Reuters in 2020.

A long, tough process

Philippine Journalist Maria Ressa: 'Journalism Is Activism'

Even if the ICC decides to open a formal investigation, Orentlicher says Duterte's defiance should not be underestimated. Journalists who have exposed the drug war have been jailed, and human rights advocates who have spoken out, including members of the clergy, have been threatened.

"This is going to be a very tough process," Orentlicher says, "not for the faint of heart at all."

Portraits of alleged victims of the Philippine war on drugs are displayed during a protest on July 22, 2019, in Manila. Richard James Mendoza/NurPhoto via Getty Images hide caption

Portraits of alleged victims of the Philippine war on drugs are displayed during a protest on July 22, 2019, in Manila.

Human rights attorney Colmenares maintains a cautious optimism that there will be a legal reckoning on behalf of the victims' families who want justice.

"It may be long and it may be arduous," Colmenares says, "but that's how struggles are fought and that's how struggles are won."

- international law

- Philippine drug war

- The Philippines

- rodrigo duterte

- International Criminal Court

- crimes against humanity

- Philippines

- Fatou Bensouda

Annals of Global Health

- Download PDF (English) XML (English)

- Alt. Display

Expert Consensus Documents, Recommendations, and White Papers

The manila declaration on the drug problem in the philippines.

- Nymia Simbulan

- Leonardo Estacio

- Carissa Dioquino-Maligaso

- Teodoro Herbosa

- Mellissa Withers

When Philippine President Rodrigo R. Duterte assumed office in 2016, his government launched an unprecedented campaign against illegal drugs. The drug problem in the Philippines has primarily been viewed as an issue of law enforcement and criminality, and the government has focused on implementing a policy of criminalization and punishment. The escalation of human rights violations has caught the attention of groups in the Philippines as well as the international community. The Global Health Program of the Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU), a non-profit network of 50 universities in the Pacific Rim, held its 2017 annual conference in Manila. A special half-day workshop was held on illicit drug abuse in the Philippines which convened 167 participants from 10 economies and 21 disciplines. The goal of the workshop was to collaboratively develop a policy statement describing the best way to address the drug problem in the Philippines, taking into consideration a public health and human rights approach to the issue. The policy statement is presented here.

When Philippine President Rodrigo R. Duterte assumed office on June 30, 2016, his government launched an unprecedented campaign against illegal drugs. He promised to solve the illegal drug problem in the country, which, according to him, was wreaking havoc on the lives of many Filipino families and destroying the future of the Filipino youth. He declared a “war on drugs” targeting users, peddlers, producers and suppliers, and called for the Philippine criminal justice system to put an end to the drug menace [ 1 ].

According to the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) (the government agency mandated to formulate policies on illegal drugs in the Philippines), there are 1.8 million current drug users in the Philippines, and 4.8 million Filipinos report having used illegal drugs at least once in their lives [ 2 ]. More than three-quarters of drug users are adults (91%), males (87%), and have reached high school (80%). More than two-thirds (67%) are employed [ 2 ]. The most commonly used drug in the Philippines is a variant of methamphetamine called shabu or “poor man’s cocaine.” According to a 2012 United Nations report, the Philippines had the highest rate of methamphetamine abuse among countries in East Asia; about 2.2% of Filipinos between the ages 16–64 years were methamphetamines users.

The drug problem in the Philippines has primarily been viewed as an issue of law enforcement and criminality, and the government has focused on implementing a policy of criminalization and punishment. This is evidenced by the fact that since the start of the “war on drugs,” the Duterte government has utilized punitive measures and has mobilized the Philippine National Police (PNP) and local government units nationwide. With orders from the President, law enforcement agents have engaged in extensive door-to-door operations. One such operation in Manila in August 2017 aimed to “shock and awe” drug dealers and resulted in the killing of 32 people by police in one night [ 3 ].

On the basis of mere suspicion of drug use and/or drug dealing, and criminal record, police forces have arrested, detained, and even killed men, women and children in the course of these operations. Male urban poor residents in Metro Manila and other key cities of the country have been especially targeted [ 4 ]. During the first six months of the Duterte Presidency (July 2016–January 2017), the PNP conducted 43,593 operations that covered 5.6 million houses, resulting in the arrest of 53,025 “drug personalities,” and a reported 1,189,462 persons “surrendering” to authorities, including 79,349 drug dealers and 1,110,113 drug users [ 5 ]. Government figures show that during the first six months of Duterte’s presidency, more than 7,000 individuals accused of drug dealing or drug use were killed in the Philippines, both from legitimate police and vigilante-style operations. Almost 2,555, or a little over a third of people suspected to be involved in drugs, have been killed in gun battles with police in anti-drug operations [ 5 , 6 ]. Community activists estimate that the death toll has now reached 13,000 [ 7 ]. The killings by police are widely believed to be staged in order to qualify for the cash rewards offered to policeman for killing suspected drug dealers. Apart from the killings, the recorded number of “surrenderees” resulting in mass incarceration has overwhelmed the Philippine penal system, which does not have sufficient facilities to cope with the population upsurge. Consequently, detainees have to stay in overcrowded, unhygienic conditions unfit for humans [ 8 ].

The escalation of human rights violations, particularly the increase in killings, both state-perpetrated and vigilante-style, has caught the attention of various groups and sectors in society including the international community. Both police officers and community members have reported fear of being targeted if they fail to support the state-sanctioned killings [ 9 ]. After widespread protests by human rights groups, Duterte called for police to shoot human rights activists who are “obstructing justice.” Human Rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have said that Duterte’s instigation of unlawful police violence and the incitement of vigilante killings may amount to crimes against humanity, violating international law [ 10 , 11 ]. The European Union found that human rights have deteriorated significantly since Duterte assumed power, saying “The Philippine government needs to ensure that the fight against drug crimes is conducted within the law, including the right to due process and safeguarding of the basic human rights of citizens of the Philippines, including the right to life, and that it respects the proportionality principle [ 12 ].” Despite the fact that, in October 2017, Duterte ordered the police to end all operations in the war on drugs, doubts remain as to whether the state-sanctioned killings will stop [ 13 ]. Duterte assigned the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) to be the sole anti-drug enforcement agency.

Duterte’s war on drugs is morally and legally unjustifiable and has created large-scale human rights violations; and is also counterproductive in addressing the drug problem. International human rights groups and even the United Nations have acknowledged that the country’s drug problem cannot be resolved using a punitive approach, and the imposition of criminal sanctions and that drug users should not be viewed and treated as criminals [ 14 ]. Those critical of the government’s policy towards the illegal drug problem have emphasized that the drug issue should be viewed as a public health problem using a rights-based approach (RBA). This was affirmed by UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon on the 2015 International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illegal Trafficking when he stated, “…We should increase the focus on public health, prevention, treatment and care, as well as on economic, social and cultural strategies [ 15 ].” The United Nations Human Rights Council released a joint statement in September 2017, which states that the human rights situation in the Philippines continued to cause serious concern. The Council urged the government of the Philippines to “take all necessary measures to bring these killings to an end and cooperate with the international community to pursue appropriate investigations into these incidents, in keeping with the universal principles of democratic accountability and the rule of law [ 16 ].” In October 2017, the Philippines Dangerous Drug Board (DDB) released a new proposal for an anti-drug approach that protects the life of the people. The declaration includes an implicit recognition of the public health aspect of illegal drug use, “which recognizes that the drug problem as both social and psychological [ 16 ].”

Workshop on Illicit Drug Abuse in the Philippines

The Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU) is a non-profit network of 50 leading research universities in the Pacific Rim region, representing 16 economies, 120,000 faculty members and approximately two million students. Launched in 2007, the APRU Global Health Program (GHP) includes approximately 1,000 faculty, students, and researchers who are actively engaged in global health work. The main objective of the GHP is to advance global health research, education and training in the Pacific Rim, as APRU member institutions respond to global and regional health challenges. Each year, about 300 APRU GHP members gather at the annual global health conference, which is hosted by a rotating member university. In 2017, the University of the Philippines in Manila hosted the conference and included a special half-day workshop on illicit drug abuse in the Philippines.

Held on the first day of the annual APRU GHP conference, the workshop convened 167 university professors, students, university administrators, government officials, and employees of non-governmental organizations (NGO), from 21 disciplines, including anthropology, Asian studies, communication, dentistry, development, education, environmental health, ethics, international relations, law, library and information science, medicine, nutrition, nursing, occupational health, pharmaceutical science, physical therapy, political science, psychology, public health, and women’s studies. The participants came from 10 economies: Australia, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Nepal, the Philippines, Thailand, and the US. The special workshop was intended to provide a venue for health professionals and workers, academics, researchers, students, health rights advocates, and policy makers to: 1) give an overview on the character and state of the drug problem in the Philippines, including the social and public health implications of the problem and the approaches being used by the government in the Philippines; 2) learn from the experiences of other countries in the handling of the drug and substance abuse problem; and 3) identify appropriate methods and strategies, and the role of the health sector in addressing the problem in the country. The overall goal of the workshop was to collaboratively develop a policy statement describing the best way to address this problem in a matnner that could be disseminated to all the participants and key policymakers both in the Philippines, as well as globally.

The workshop included presentations from three speakers and was moderated by Dr. Carissa Paz Dioquino-Maligaso, head of the National Poison Management and Control Center in the Philippines. The first speaker was Dr. Benjamin P. Reyes, Undersecretary of the Philippine Dangerous Drugs Board, who spoke about “the State of the Philippine Drug and Substance Abuse Problem in the Philippines.” The second speaker was Dr. Joselito Pascual, a medical specialist from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, at the University of the Philippines General Hospital in Manila. His talk was titled “Psychotropic Drugs and Mental Health.” The final speaker was Patrick Loius B. Angeles, a Policy and Research Officer of the NoBox Transitions Foundation, whose talk was titled “Approaches to Addressing the Drug and Substance Abuse Problem: Learning from the Experiences of Other Countries.” Based on the presentations, a draft of the Manila Declaration on the Drug Problem in the Philippines was drafted by the co-authors of this paper. The statement was then sent to the workshop participants for review and comments. The comments were reviewed and incorporated into the final version, which is presented below.

Declaration

“Manila Statement on the Drug Problem in the Philippines”

Gathering in this workshop with a common issue and concern – the drug problem in the Philippines and its consequences and how it can be addressed and solved in the best way possible;

Recognizing that the drug problem in the Philippines is a complex and multi-faceted problem that includes not only criminal justice issues but also public health issues and with various approaches that can be used in order to solve such;

We call for drug control policies and strategies that incorporate evidence-based, socially acceptable, cost-effective, and rights-based approaches that are designed to minimize, if not to eliminate, the adverse health, psychological, social, economic and criminal justice consequences of drug abuse towards the goal of attaining a society that is free from crime and drug and substance abuse;

Recognizing, further, that drug dependency and co-dependency, as consequences of drug abuse, are mental and behavioral health problems, and that in some areas in the Philippines injecting drug use comorbidities such as the spread of HIV and AIDS are also apparent, and that current prevention and treatment interventions are not quite adequate to prevent mental disorders, HIV/AIDS and other co-morbid diseases among people who use drugs;

Affirming that the primacy of the sanctity/value of human life and the value of human dignity, social protection of the victims of drug abuse and illegal drugs trade must be our primary concern;

And that all health, psycho-social, socio-economic and rights-related interventions leading to the reduction or elimination of the adverse health, economic and social consequences of drug abuse and other related co-morbidities such as HIV/AIDS should be considered in all plans and actions toward the control, prevention and treatment of drug and substance abuse;

As a community of health professionals, experts, academics, researchers, students and health advocates, we call on the Philippine government to address the root causes of the illegal drug problem in the Philippines utilizing the aforementioned affirmations . We assert that the drug problem in the country is but a symptom of deeper structural ills rooted in social inequality and injustice, lack of economic and social opportunities, and powerlessness among the Filipino people. Genuine solutions to the drug problem will only be realized with the fulfillment and enjoyment of human rights, allowing them to live in dignity deserving of human beings. As members of educational, scientific and health institutions of the country, being rich and valuable sources of human, material and technological resources, we affirm our commitment to contribute to solving this social ill that the Philippine government has considered to be a major obstacle in the attainment of national development.

The statement of insights and affirmations on the drug problem in the Philippines is a declaration that is readily applicable to other countries in Asia where approaches to the problem of drug abuse are largely harsh, violent and punitive.

As a community of scholars, health professionals, academics, and researchers, we reiterate our conviction that the drug problem in the Philippines is multi-dimensional in character and deeply rooted in the structural causes of poverty, inequality and powerlessness of the Filipino people. Contrary to the government’s position of treating the issues as a problem of criminality and lawlessness, the drug problem must be addressed using a holistic and rights-based approach, requiring the mobilization and involvement of all stakeholders. This is the message and the challenge which we, as members of the Association of Pacific Rim Universities, want to relay to the leaders, policymakers, healthcare professionals, and human rights advocates in the region; we must all work together to protect and promote health and well being of all populations in our region.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Xu M. Human Rights and Duterte’s War on Drugs. Council on Foreign Relations ; 16 December, 2016. https://www.cfr.org/interview/human-rights-and-dutertes-war-drugs . Accessed December 20, 2017.

Gavilan J. Duterte’s War on Drugs: The first 6 months. Rappler ; 2016. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/rich-media/rodrigo-duterte-war-on-drugs-2016 . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Holmes O. Human rights group slams Philippines president Duterte’s threat to kill them. The Guardian ; 17 August, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/17/human-rights-watch-philippines-president-duterte-threat . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Almendral A. On patrol with police as Philippines battles drugs. New York Times ; 2016. 21 December 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/21/world/asia/on-patrol-with-police-as-philippines-wages-war-on-drugs.html . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Bueza M. In Numbers: The Philippines’ ‘war on drugs.’ Rappler ; 13 September 2017. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/145814-numbers-statistics-philippines-war-drugs . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Mogato M and Baldwin C. Special Report: Police Describe Kill Rewards, Staged Crime Scenes in Duterte’s Drug War. Reuters ; 18 April, 2017. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-duterte-police-specialrep-idUSKBN17K1F4 . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Al Jazeera. Thousands demand end to killings in Duterte’s drug war; 21 August, 2017. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/08/thousands-demand-killings-duterte-drug-war-170821124440845.html Published 2017. Accessed January 18, 2018.

Worley W. Harrowing photos from inside Filipino jail show reality of Rodrigo Duterte’s brutal war on drugs. The Independent ; 30 July, 2016. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/filipino-philippines-prison-jail-presidentrodrigo-duterte-war-on-drugs-a7164006.html . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Baldwin C, Marshall ARC and Sagolj D. Police Rack Up an Almost Perfectly Deadly Record in Philippine Drug War. Reuters ; 5 December, 2016. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/philippines-duterte-police/ . Accessed January 20, 2018.

Amnesty International. Philippines: The police’s murderous war on the poor; 31 January, 2017. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/01/philippines-the-police-murderous-war-on-the-poor/ . Accessed January 18,2018.

Human Rights Watch. Philippines: Duterte threatens human rights community; 17 August, 2017. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/08/17/philippines-duterte-threatens-human-rights-community . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Andadolu News Agency. EU: Human rights worsened with Duterte’s drug war. Al Jazeera ; 24 October, 2017. www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/eu-human-rights-worsened-duterte-drug-war-171024064212027.html . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Holmes O. Rodrigo Duterte pulls Philippine police out of brutal war on drugs. Reuters ; 2017b. 11 October, 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/12/philippines-rodrigo-duterte-police-war-drugs . Accessed January 18, 2018.

International Drug Policy Consortium. A Public Health Approach to Drug Use in Asia; 2016. https://fileserver.idpc.net/library/Drug-decriminalisation-in-Asia_ENGLISH-FINAL.pdf . Accessed April 5, 2018.

United Nations Secretary-General. Secretary-General’s message on International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking; 26 June, 2015. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2015-06-26/secretary-generals-message-international-day-against-drug-abuse-and . Accessed January 18, 2018.

Kine P. Philippine Drug Board Urges New Focus To Drug Campaign. Human Rights Watch ; 30 October, 2017. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/10/30/philippine-drug-board-urges-new-focus-drug-campaign . Accessed January 18, 2018.

- Top Stories

- Pinoy Abroad

- #ANONGBALITA

- Economy & Trade

- Banking & Finance

- Agri & Mining

- IT & Telecom

- Fightsports

- Sports Plus

- One Championship

- TV & Movies

- Celebrity Profiles

- Music & Concerts

- Digital Media

- Culture & Media

- Health and Home

- Accessories

- Motoring Plus

- Commuter’s Corner

- Residential

- Construction

- Environment and Sustainability

- Agriculture

- Performances

- Malls & Bazaars

- Hobbies & Collections

Substance use and vices have primarily declined in the youth in the year 2021 compared to consumption in earlier years.

This was indicated in a study conducted by the University of the Philippines Population Institute (UPPI).

Key findings by the 2021 Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Study (YAFS5) identified drinking, smoking, and using illegal drugs as the main vices seen in the youth of today. Three out of 10 young adult Filipinos are currently drinking, one out of 10 are smoking, and nearly none are engaging in illegal drug use.

“From 1994 to 2013, close to four in 10 youth were drinking, but the percentage declined to 29% in 2021. Some 45% of drinkers said they were drinking less during the pandemic, while 65% said they want to stop drinking,” The press release by UPPI stated.

Since 1994, the YAFS has been monitoring young Filipinos’ substance use mainly alcohol, nicotine, and illicit drugs. They have deemed the latest data as having a positive impact on the youth’s non-sexual risk behaviors.

The study also showed that in 2021, two percent of Filipino smokers are young adult females, while 23 percent are young adult males. Forty-three percent of alcohol consumers, on the other hand, have been identified to be young adult males, while 17 percent are young adult females.

Despite this decline, however, an alarming 16 percent of Filipino youth have found themselves engaged in vaping which comes with its own health risks.

Some young adults had expressed that their decision to decrease their vices is strongly affiliated with not only the price hike but also their hazardous effects on human health.

“You need to save money a lot, hence the hobbies, vices or something else are really decreasing, which you really need to minimize because we need more of our essentials,” Kevin Tolentino, a vape user, stated in a GMA news interview.

A smoker also explained that the pandemic had played a big factor in his smoking habits.

“The pandemic has actually reduced my smoking quite by a lot. I think there was a time during the pandemic where I didn’t smoke for 3 months and I think that’s the longest I’ve gone without smoking,” Sheldon, 22, told reporters.

He also said that the thought of quitting smoking has crossed his mind “Whenever I smoke a lot and start to get headaches, I tell myself that maybe I should stop smoking and contemplate quitting,” he added.

As the study claims, the youth were confined at home during the pandemic which resulted in an increase in involvement in more sedentary activities.

According to the Department of Health, the juice from electronic cigarettes has a high level of addictive nicotine, which can lead to acute or fatal poisoning through ingestion. The Philippine Pediatric Society has also shared the same sentiments as previously released in a statement, claiming that e-cigarettes are strongly addictive and can possibly lead to cancer.

“Nicotine impairs maximum development of their brain, making them vulnerable to engage in deleterious habits which threaten their health and more so, making them at risk to try other dangerous substances,” a statement on the society’s official website reads.

“We cannot allow our children and our youth to be exposed to the harmful effects of e-cigarettes. In the US, they have reported the health hazards of e-cigarettes in the young population i.e. vape-induced lung injuries, seizure, early onset cardiovascular diseases, poisoning, and accidental explosions. The same scenario may happen in our country, and these health problems in the young due to e-cigarettes will add up to the burden of health care in our country,” The society concluded.

Based on the Philippine Statistics Authority’s study, in March 2019, “The increment in the index of beverages and tobacco in March 2019 at 0.4 percent was slower compared with its previous month’s rate of 1.0 percent. Higher prices noted in selected alcoholic beverages during the period were tempered by the price decreases in selected cigarettes.”

By December 2020, the prices of alcoholic beverages and tobacco increased by 16.1 percent.

In December of the previous year, the PSA said that “lower annual increments were observed in the indices” with tobacco and alcoholic beverages at 6.2 percent. They also claimed that “slower annual average inflation rates were observed in the following commodity groups in 2021,” with tobacco and alcoholic beverages at 11.1%.

In the National Capital Region (NCR), the prices for alcoholic beverages and tobacco had slowed down by following the annual hikes during the month of December 2021 by 7.6 percent. For the areas outside of NCR (AONCR), the prices had slowed down as well by 6.2 percent.

The government, with encouragement from civil society groups, has already taken action against the issue of substance abuse in the form of excessive consumption through the passing of the Sin Tax Law of 2012. It aims to curb tobacco and alcohol consumption.

- Substance use

LATEST NEWS

‘divorce covers church unions’, ombudsman suspends bohol governor over controversial chocolate hills resort, driver of white suv killed in ayala tunnel, bsp confirms ‘unprecedented’ irregularities involving 2 supervisors, 4 employees, popular articles, owag shi kayapa, happy living marks 30th anniversary with epic wine festival – enjoy 150+ kinds of the world’s best wines this june, plebescite forms., modern vehicles for dswd.

- Economy & Trade

- Banking & Finance

- Agri & Mining

- IT & Telecom

On the Road

- Monitoring Plus

- Commuter's Corner

- Malls & Bazaars

- Hobbies & Collections

- Travel Features

- Travel Reels

- Travel Logs

- Entertainment

- TV & Movies

- Music & Concerts

- Culture & Media

Home & Design

- Environment & Sustainability

- Users Agreement

© All Rights Reserved, Newspaper Theme.

- Special Pages

- Transparency Seal

- Major Programs & Projects

2022 Statistical Analysis

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

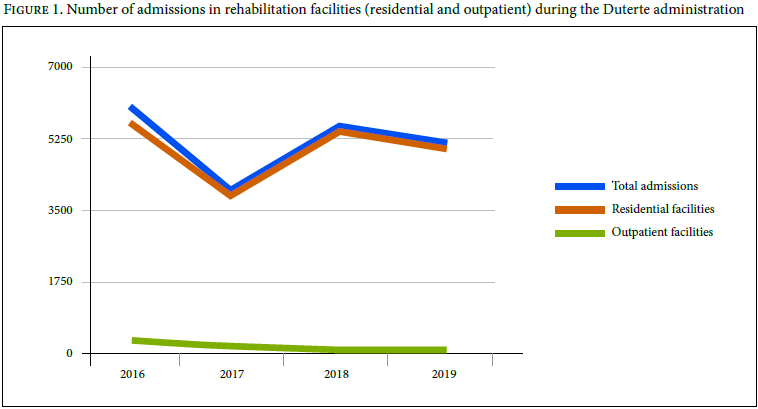

For 2022, a total of seventy (70) treatment and rehabilitation facilities reporting to the Treatment and Rehabilitation Admission Information System (TRAIS). Of this, sixty-two (62) are residential and eight (8) are outpatient.

Three thousand, eight hundred sixty-five (3,865) admissions were recorded from these reporting facilities. Of these number, three thousand, three hundred forty-three (3,343) are new admissions, seventy-nine (79) are readmitted or relapse cases and four hundred forty-three (443) are Outpatient.

Compared with the previous year’s cases, around forty-three percent (42.73%) increase in admission was noted despite some facilities having reported no admissions. The rise in admission can be attributed to the resumption of operation by the different rehabilitation centers and the seeming willingness of the Persons Who Use Drugs (PWUDs) to undergo treatment and rehabilitation as evidenced by almost forty-one percent (40.78%) of voluntary submission and twenty-nine percent (29.00%) cases who availed of plea bargaining.

Demographic profile

The center admissions consist of ninety percent (90.06%) males, nine percent (9.08%) females, and around one percent (0.85%) LGBT. The male-to-female ratio is 10:1 with a computed mean of 33 years old and a median age of 34. The youngest admission for the year under review is 13 , whilethe eldest is 72. The majority of the admissions belong to the age group of 40 years old and above with thirty-one percent (31.23%) of the reported cases.

Fifty-three percent (52.68%) are single and around twenty-four percent (23.91%) are married, those who have live-in partners comprised nineteen percent (19.22%), and the rest, about four percent (4.19%) are either widow/er, separated, divorced, or annulled.

As to educational attainment, almost a third (26.99%) have attained high school level. On the second spot are those who have reached college with twenty percent (19.61%) followed by those who have graduated high school at seventeen percent (17.44%).

The average monthly family income is around thirteen thousand pesos (Php 13,199.22).

Regarding the status of employment, those employed (either workers/employees or businessmen and self-employed) comprised fifty-eight percent (58.40%) while unemployed thirty-seven percent (37.05%). Three percent (3.49%) of the admission constitute students and almost one percent (0.88%) are out-of-school youth while a few (0.18%) were pensioners.

About twenty-five percent (24.53%) of reported cases are residents of the National Capital Region while sixteen percent (16.25%) are from Region III.

Considering the age at first drug use, forty-one percent (41.32%) belong to ages 15 to 19 years old. Nearly thirty-nine percent (38.73%) admitted to having taken drugs two (2) to five (5) times a week while around twenty-five percent (24.68%) used drugs monthly and twenty-one percent (20.62%) weekly.

Most Commonly Abused Drugs

Methamphetamine Hydrochloride or “Shabu” remains the leading drug of abuse, comprising ninety-two percent (92.06%) of the total admission. This is followed by Cannabis (Marijuana) at twenty-seven percent (27.04%) and followed distantly by MDMA or Ecstasy as the third drug of choice at less than one percent (0.65%).

Mono-drug use is still the nature of drug-taking; the administration routes are inhalation/sniffing and oral ingestion.

Divi Business Management Software

Ready to get started.

We found over 300 million young people had experienced online sexual abuse and exploitation over the course of our meta-study

Professor of International Child Protection Research and Director of Data at the Childlight Global Child Safety Institute , The University of Edinburgh

Disclosure statement

Deborah Fry receives funding from the Human Dignity Foundation.

The University of Edinburgh provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

It takes a lot to shock Kelvin Lay. My friend and colleague was responsible for setting up Africa’s first dedicated child exploitation and human trafficking units, and for many years he was a senior investigating officer for the Child Exploitation Online Protection Centre at the UK’s National Crime Agency, specialising in extra territorial prosecutions on child exploitation across the globe.

But what happened when he recently volunteered for a demonstration of cutting-edge identification software left him speechless. Within seconds of being fed with an image of how Lay looks today, the AI app sourced a dizzying array of online photos of him that he had never seen before – including in the background of someone else’s photographs from a British Lions rugby match in Auckland eight years earlier.

“It was mind-blowing,” Lay told me. “And then the demonstrator scrolled down to two more pictures, taken on two separate beaches – one in Turkey and another in Spain – probably harvested from social media. They were of another family but with me, my wife and two kids in the background. The kids would have been six or seven; they’re now 20 and 22.”

The AI in question was one of an arsenal of new tools deployed in Quito, Ecuador, in March when Lay worked with a ten-country taskforce to rapidly identify and locate perpetrators and victims of online child sexual exploitation and abuse – a hidden pandemic with over 300 million victims around the world every year.

That is where the work of the Childlight Global Child Safety Institute , based at the University of Edinburgh, comes in. Launched a little over a year ago in March 2023 with the financial support of the Human Dignity Foundation , Childlight’s vision is to use the illuminating power of data and insight to better understand the nature and extent of child sexual exploitation and abuse.

This article is part of Conversation Insights The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

I am a professor of international child protection research and Childlight’s director of data, and for nearly 20 years I have been researching sexual abuse and child maltreatment, including with the New York City Alliance Against Sexual Assault and Unicef.

The fight to keep our young people safe and secure from harm has been hampered by a data disconnect – data differs in quality and consistency around the world, definitions differ and, frankly, transparency isn’t what it should be. Our aim is to work in partnership with many others to help join up the system, close the data gaps and shine a light on some of the world’s darkest crimes.

302 million victims in one year

Our new report, Into The Light , has produced the world’s first estimates of the scale of the problem in terms of victims and perpetrators.

Our estimates are based on a meta-analysis of 125 representative studies published between 2011 and 2023, and highlight that one in eight children – 302 million young people – have experienced online sexual abuse and exploitation in a one year period preceding the national surveys.

Additionally, we analysed tens of millions of reports to the five main global watchdog and policing organisations – the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), the Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P), the International Association of Internet Hotlines (INHOPE), and Interpol’s International Child Sexual Exploitation database (ICSE). This helped us better understand the nature of child sexual abuse images and videos online.

While huge data gaps mean this is only a starting point, and far from a definitive figure, the numbers we have uncovered are shocking.

We found that nearly 13% of the world’s children have been victims of non-consensual taking, sharing and exposure to sexual images and videos.

In addition, just over 12% of children globally are estimated to have been subject to online solicitation, such as unwanted sexual talk which can include non-consensual sexting, unwanted sexual questions and unwanted sexual act requests by adults or other youths.

Cases have soared since COVID changed the online habits of the world. For example, the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) reported in 2023 that child sexual abuse material featuring primary school children aged seven to ten being coached to perform sexual acts online had risen by more than 1,000% since the UK went into lockdown.

The charity pointed out that during the pandemic, thousands of children became more reliant on the internet to learn, socialise, and play and that this was something which internet predators exploited to coerce more children into sexual activities – sometimes even including friends or siblings over webcams and smartphones.

There has also been a sharp rise in reports of “financial sextortion”, with children blackmailed over sexual imagery that abusers have tricked them into providing – often with tragic results, with a spate of suicides across the world .

This abuse can also utilise AI deepfake technology – notoriously used recently to generate false sexual images of the singer Taylor Swift.

Our estimates indicate that just over 3% of children globally experienced sexual extortion in the past year.

A child sexual exploitation pandemic

This child sexual exploitation and abuse pandemic affects pupils in every classroom, in every school, in every country, and it needs to be tackled urgently as a public health emergency. As with all pandemics, such as COVID and AIDS, the world must come together and provide an immediate and comprehensive public health response.

Our report also highlights a survey which examines a representative sample of 4,918 men aged over 18 living in Australia , the UK and the US. It has produced some startling findings. In terms of perpetrators:

One in nine men in the US (equating to almost 14 million men) admitted online sexual offending against children at some point in their lives – enough offenders to form a line stretching from California on the west coast to North Carolina in the east or to fill a Super Bowl stadium more than 200 times over.

The surveys found that 7% of men in the UK had admitted the same – equating to 1.8 million offenders, or enough to fill the O2 area 90 times over and by 7.5% of men in Australia (nearly 700,000).

Meanwhile, millions across all three countries said they would also seek to commit contact sexual offences against children if they knew no one would find out, a finding that should be considered in tandem with other research indicating that those who watch child sexual abuse material are at high risk of going on to contact or abuse a child physically.

The internet has enabled communities of sex offenders to easily and rapidly share child abuse and exploitation images on a staggering scale, and this in turn, increases demand for such content among new users and increases rates of abuse of children, shattering countless lives.

In fact, more than 36 million reports of online sexual images of children who fell victim to all forms form of sexual exploitation and abuse were filed in 2023 to watchdogs by companies such as X, Facebook, Instagram, Google, WhatsApp and members of the public. That equates to one report every single second.

Quito operation

Like everywhere in the world, Ecuador is in the grip of this modern, transnational problem: the rapid spread of child sexual exploitation and abuse online. It can see an abuser in, say, London, pay another abuser in somewhere like the Philippines to produce images of atrocities against a child that are in turn hosted by a data centre in the Netherlands and dispersed instantly across multiple other countries.

When Lay – who is also Childlight’s director of engagement and risk – was in Quito in 2024, martial law meant a large hotel normally busy with tourists flocking for the delights of the Galápagos Islands, was eerily quiet, save for a group of 40 law enforcement analysts, researchers and prosecutors who had more than 15,000 child sexual abuse images and videos to analyse.

The cache of files included material logged with authorities annually, content from seized devices, and from Interpol’s International Child Sexual Exploitation (ICSE) database database. The files were potentially linked to perpetrators in ten Latin American and Caribbean countries: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Peru and the Dominican Republic.

Child exploitation exists in every part of the world but, based on intelligence from multiple partners in the field, we estimate that a majority of Interpol member countries lack the training and resources to properly respond to evidence of child sexual abuse material shared with them by organisations like the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). NCMEC is a body created by US Congress to log and process evidence of child sexual abuse material uploaded around the world and spotted, largely, by tech giants. However, we believe this lack of capacity means that millions of reports alerting law enforcement to abuse material are not even opened.

The Ecuador operation, in conjunction with the International Center for Missing and Exploited Children (ICMEC) and US Homeland Security, aimed to help change that by supporting authorities to develop further skills and confidence to identify and locate sex offenders and rescue child victims.

Central to the Quito operation was Interpol’s database database that contains around five million images and videos that specialised investigators from more than 68 countries use to share data and co-operate on cases.

Using image and video comparison software – essentially photo ID work that instantly recognises the digital fingerprint of images – investigators can quickly compare images they have uncovered with images contained in the database. The software can instantly make connections between victims, abusers and places. It also avoids duplication of effort and saves precious time by letting investigators know whether images have already been discovered or identified in another country. So far, it has helped identify more than 37,900 victims worldwide.

Lay has significant field experience using these resources to help Childlight turn data into action – recently providing technical advice to law enforcement in Kenya where successes included using data to arrest paedophile Thomas Scheller. In 2023, Scheller, 74, was given an 81-year jail sentence . The German national was found guilty by a Nairobi court of three counts of trafficking, indecent acts with minors and possession of child sexual abuse material.

But despite these data strides, there are concerns about the inability of law enforcement to keep pace with a problem too large for officers to arrest their way out of. It is one enabled by emerging technological advances, including AI-generated abuse images, which threaten to overwhelm authorities with their scale.

In Quito, over a warming rainy season meal of encocado de pescado, a tasty regional dish of fish in a coconut sauce served with white rice, Lay explained:

This certainly isn’t to single out Latin America but it’s become clear that there’s an imbalance in the way countries around the world deal with data. There are some that deal with pretty much every referral that comes in, and if it’s not dealt with and something happens, people can lose their jobs. On the opposite side of the coin, some countries are receiving thousands of email referrals a day that don’t even get opened.

Now, we are seeing evidence that advances in technology can also be utilised to fight online sexual predators. But the use of such technology raises ethical questions.

Contentious AI tool draws on 40 billion online images

The powerful, but contentious AI tool, that left Lay speechless was a case in point: one of multiple AI facial recognition tools that have come onto the market, and with multiple applications. The technology can help identify people using billions of images scraped from the internet, including social media.

AI facial recognition software like this has reportedly been used by Ukraine to debunk false social media posts, enhance safety at check points and identify Russian infiltrators, as well as dead soldiers. It was also reportedly used to help identify rioters who stormed the US capital in 2021.

The New York Times magazine reported on another remarkable case. In May 2019, an internet provider alerted authorities after a user received images depicting the sexual abuse of a young girl.

One grainy image held a vital clue: an adult face visible in the background that the facial recognition company was able to match to an image on an Instagram account featuring the same man, again in the background. This was in spite of the fact that the image of his face would have appeared about half the size of a human fingernail when viewing it. It helped investigators pinpoint his identity and the Las Vegas location where he was found to be creating the child sexual abuse material to sell on the dark web. That led to the rescue of a seven-year-old girl and to him being sentenced to 35 years in jail.

Meanwhile, for its part, the UK government recently argued that facial recognition software can allow police to “stay one step ahead of criminals” and make Britain’s streets safer. Although, at the moment, the use of such software is not allowed in the UK.

When Lay volunteered to allow his own features to be analysed, he was stunned that within seconds the app produced a wealth of images, including one that captured him in the background of a photo taken at the rugby match years before. Think about how investigators can equally match a distinctive tattoo or unusual wallpaper where abuse has occurred and the potential of this as a crime-fighting tool is easy to appreciate.

Of course, it is also easy to appreciate the concerns some people have on civil liberties grounds which have limited the use of such technology across Europe. In the wrong hands, what might such technology mean for a political dissident in hiding for instance? One Chinese facial recognition startup has come under scrutiny by the US government for its alleged role in the surveillance of the Uyghur minority group, for example.

Role of big tech

Similar points are sometimes made by big tech proponents of end-to-end encryption on popular apps: apps which are also used to share child abuse and exploitation files on an industrial scale – effectively turning the lights off on some of the world’s darkest crimes.