Exploring the World of 250+ Interesting Topics to Research

Research is a fascinating journey into the unknown, a quest for answers, and a process of discovery. Whether you’re an academic, a student, or just a curious mind, finding the right and interesting topics to research is paramount. Not only does it determine the success of your research project, but it can also make the experience enjoyable.

In this blog, we’ll delve into the art of selecting interesting topics to research, particularly catering to the average reader.

How to Select Interesting Topics to Research?

Table of Contents

Choosing a research topic is like setting sail on a ship. It’s a decision that will dictate your course, so you must make it wisely. Here are some effective strategies to help you pick a captivating topic:

- Personal Interests: Researching a topic you’re genuinely passionate about can turn the entire process into an exciting adventure. Your enthusiasm will show in your work and make it more engaging for the reader.

- Current Trends and Issues: Current events and trends are always intriguing because they’re relevant. They often raise questions and uncertainties, making them excellent research candidates. Think of topics like the impact of a global pandemic on mental health or the evolution of renewable energy technologies in the face of climate change.

- Problem-Solving Approach: Identify a problem that needs a solution or an unanswered question. Researching with the aim to solve a real-world issue can be highly motivating. For instance, you could explore strategies to reduce plastic waste in your community.

- Impact and Relevance: Consider the significance of your topic. Will it impact people’s lives or contribute to existing knowledge? Research with a purpose tends to be more engaging. Topics like gender equality, public health, or environmental conservation often fall into this category.

- Unexplored or Unique Topics: Researching less-explored or unique topics can be exciting. It gives you the opportunity to contribute something new to your field. Remember, research isn’t limited to established subjects; there’s room for exploration in every discipline.

250+ Interesting Topics to Research: Popular Categories

Research topics come in various flavors. Let’s explore some popular categories, which are often engaging for average readers:

Science and Technology

- Artificial intelligence in healthcare.

- Quantum computing advancements.

- Space exploration and colonization.

- Genetic editing and CRISPR technology.

- Cybersecurity in the digital age.

- Augmented and virtual reality applications.

- Climate change and mitigation strategies.

- Sustainable energy sources.

- Internet of Things (IoT) innovations.

- Nanotechnology breakthroughs.

- 3D printing in various industries.

- Biotechnology in medicine.

- Autonomous vehicles and self-driving technology.

- Robotics in everyday life.

- Clean water technology.

- Renewable energy storage solutions.

- Wearable technology and health tracking.

- Green architecture and sustainable design.

- Bioinformatics and genomics.

- Machine learning in data analysis.

- Space tourism development.

- Advancements in quantum mechanics.

- Biometrics and facial recognition.

- Aerospace engineering innovations.

- Ethical considerations in AI development.

- Artificial organs and 3D bioprinting.

- Holography and holographic displays.

- Sustainable agriculture practices.

- Climate modeling and prediction.

- Advancements in battery technology.

- Neurotechnology and brain-computer interfaces.

- Space-based solar power.

- Green transportation options.

- Materials science and superconductors.

- Telemedicine and remote healthcare.

- Cognitive computing and AI ethics.

- Renewable energy policy and regulation.

- The role of 5G in the digital landscape.

- Precision medicine and personalized treatment.

- Advancements in quantum cryptography.

- Drone technology and applications.

- Environmental sensors and monitoring.

- Synthetic biology and bioengineering.

- Smart cities and urban planning.

- Quantum teleportation research.

- AI-powered virtual assistants.

- Space-based mining and resource extraction.

- Advancements in neuroprosthetics.

- Sustainable transportation solutions.

- Blockchain technology and applications.

Social Issues

- Gender inequality in the workplace.

- Racial discrimination and systemic racism.

- Income inequality and wealth gap.

- Climate change and environmental degradation.

- Mental health stigma and access to care.

- Access to quality education.

- Immigration and border control policies.

- Gun control and Second Amendment rights.

- Opioid epidemic and substance abuse.

- Affordable healthcare and insurance.

- LGBTQ+ rights and discrimination.

- Cyberbullying and online harassment.

- Homelessness and affordable housing.

- Police brutality and reform.

- Human trafficking and modern slavery.

- Voter suppression and electoral integrity.

- Access to clean water and sanitation.

- Child labor and exploitation.

- Aging population and healthcare for the elderly.

- Indigenous rights and land disputes.

- Bullying in schools and online.

- Obesity and public health.

- Access to reproductive healthcare.

- Income tax policies and fairness.

- Mental health support for veterans.

- Child abuse and neglect.

- Animal rights and cruelty.

- The digital divide and internet access.

- Youth unemployment and opportunities.

- Religious freedom and tolerance.

- Disability rights and accessibility.

- Affordable childcare and parental leave.

- Food insecurity and hunger.

- Drug policy and legalization.

- Human rights violations in conflict zones.

- Aging infrastructure and public safety.

- Cybersecurity and data privacy.

- Human rights in authoritarian regimes.

- Environmental racism and pollution.

- Discrimination against people with disabilities.

- Income and education disparities in rural areas.

- Freedom of the press and media censorship.

- Bullying and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ youth.

- Access to clean energy and sustainable practices.

- Child marriage and forced unions.

- Mental health in the workplace.

- Domestic violence and abuse.

- Education funding and quality.

- Childhood obesity and healthy habits.

- Poverty and economic development.

History and Culture

- The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire

- Ancient Egyptian Civilization

- The Renaissance Period in Europe

- The Industrial Revolution

- The French Revolution

- The American Civil War

- The Silk Road and Cultural Exchange

- The Mayan Civilization

- The Byzantine Empire

- The Age of Exploration

- World War I: Causes and Consequences

- The Harlem Renaissance

- The Aztec Empire

- Ancient Greece: Democracy and Philosophy

- The Vietnam War

- The Cold War

- The Inca Empire

- The Enlightenment Era

- The Crusades

- The Spanish Inquisition

- The African Slave Trade

- The Suffragette Movement

- The Black Death in Europe

- The Apollo Moon Landing

- The Roaring Twenties

- The Chinese Cultural Revolution

- The Salem Witch Trials

- The Great Wall of China

- The Abolitionist Movement

- The Golden Age of Islam

- The Mesoamerican Ballgame

- The Age of Vikings

- The Ottoman Empire

- The Cultural Impact of the Beatles

- The Space Race

- The Fall of the Berlin Wall

- The History of Hollywood Cinema

- The Renaissance Art and Artists

- The British Empire

- The Age of Samurai in Japan

- The Ancient Indus Valley Civilization

- The Russian Revolution

- The Age of Chivalry

- The History of Native American Tribes

- The Cultural Significance of Greek Mythology

- The Etruscans in Ancient Italy

- The History of African Kingdoms

- The Great Famine in Ireland

- The Age of Invention and Innovation

- The Cultural Impact of Shakespeare’s Works

Business and Economics

- Impact of E-commerce on Traditional Retail

- Global Supply Chain Challenges

- Green Business Practices and Sustainability

- Strategies for Small Business Growth

- Cryptocurrency and Its Economic Implications

- Consumer Behavior in the Digital Age

- The Gig Economy and Its Future

- Economic Consequences of Climate Change

- The Role of AI in Financial Services

- Trade Wars and Their Effects on Global Markets

- Entrepreneurship in Emerging Markets

- Corporate Social Responsibility Trends

- The Economics of Healthcare

- The Impact of Inflation on Savings

- Startup Ecosystems and Innovation Hubs

- Financial Literacy and Education Initiatives

- Income Inequality and Economic Mobility

- The Sharing Economy and Collaborative Consumption

- International Trade Policies

- Behavioral Economics in Marketing

- Economic Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Fintech Innovations and Banking

- Real Estate Market Trends

- Public vs. Private Healthcare Systems

- Market Entry Strategies for New Businesses

- Global Economic Growth Prospects

- The Economics of Education

- Mergers and Acquisitions Trends

- Impact of Tax Reforms on Businesses

- Sustainable Investing and ESG Factors

- Monetary Policy and Interest Rates

- The Future of Work: Remote vs. Office

- Business Ethics and Corporate Governance

- The Economics of Artificial Intelligence

- Stock Market Volatility

- Supply and Demand Dynamics

- Entrepreneurial Finance and Fundraising

- Innovation and Technology Transfer

- Competition in the Digital Marketplace

- Economic Impacts of Aging Populations

- Economic Development in Developing Countries

- Regulatory Challenges in the Financial Sector

- The Economics of Healthcare Insurance

- Corporate Profitability and Market Share

- Energy Economics and Renewable Sources

- Economic Factors in Mergers and Acquisitions

- Financial Crises and Their Aftermath

- Economics of the Entertainment Industry

- Global Economic Trends Post-Pandemic

- Economic Consequences of Cybersecurity Threats

- The Impact of Online Learning

- Strategies for Inclusive Education

- Early Childhood Development

- The Role of Teachers in Student Motivation

- Educational Technology Trends

- Assessment Methods in Education

- The Importance of Multilingual Education

- Special Education Approaches

- Global Education Disparities

- Project-Based Learning

- Critical Thinking in the Classroom

- Educational Leadership

- Homeschooling vs. Traditional Education

- Education and Social Inequality

- Student Mental Health Support

- The Benefits of Student Extracurricular Activities

- The Montessori Approach

- STEM Education

- Educational Policy Reforms

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Educational Psychology

- Learning Disabilities

- Adult Education Programs

- The Role of Arts in Education

- The Flipped Classroom Model

- Educational Gamification

- School Bullying Prevention

- Inclusive Curriculum Design

- The Future of College Admissions

- Early Literacy Development

- Education and Gender Equity

- Teacher Training and Professional Development

- Homeschooling Challenges

- Gifted and Talented Education

- Education for Global Citizenship

- Virtual Reality in Education

- Outdoor and Environmental Education

- Education for Sustainable Agriculture

- Music Education Benefits

- Education and Technological Divide

- Cultural Competence in Education

- Education and Social Emotional Learning

- Personalized Learning

- Educational Equity

- Restorative Justice in Schools

- Study Abroad Programs

- Education for Digital Citizenship

- The Role of Parents in Education

- Vocational Education and Training

- The History of Education Movements

Techniques for Researching Interesting Topics

Once you’ve chosen the interesting topics to research, you’ll need effective techniques to delve deeper into it:

- Online Databases and Journals: Online academic databases like Google Scholar, JSTOR, or PubMed are invaluable resources. They provide access to a vast pool of academic research papers.

- Interviews and Surveys: If your topic involves human perspectives, conducting interviews or surveys can offer firsthand insights. Tools like Jotform Survey Maker , SurveyMonkey or Zoom can be helpful.

- Libraries and Archives: Traditional libraries still hold a treasure trove of information. Whether you visit in person or explore digital archives, libraries can provide a wealth of resources.

- Online Forums and Social Media: Online communities and forums can be excellent sources of information, particularly for trending topics. Sites like Reddit and Quora can connect you with experts and enthusiasts.

- Academic and Expert Sources: Seek out academic articles, books, and experts in your field. Don’t hesitate to reach out to professionals who may be willing to share their expertise.

How to Make Your Research Engaging?

Once you’ve conducted your research, it’s essential to present it in a way that captures the interest of your average reader:

1. Clear and Accessible Language

Avoid jargon and complex terminology. Use simple and straightforward language to ensure your research is accessible to a wide audience.

2. Storytelling and Anecdotes

Weave stories and anecdotes into your research to make it relatable and engaging. Personal narratives and real-life examples can resonate with readers.

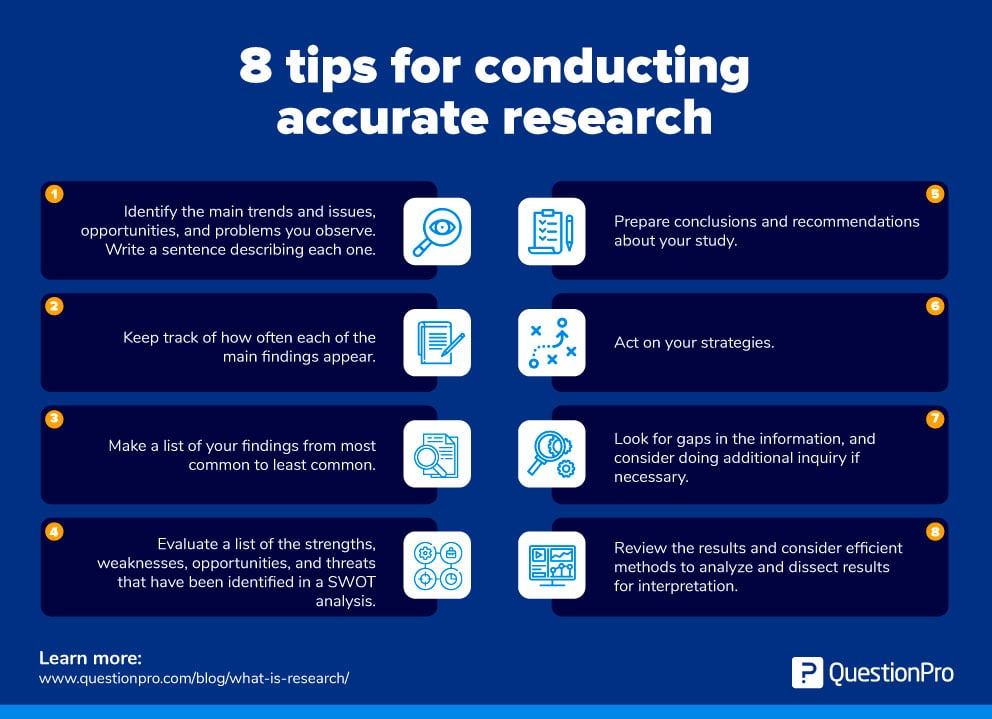

3. Visual Aids (Images, Infographics)

Incorporate visuals like images, charts, and infographics to make your research visually appealing and easier to understand.

4. Real-Life Examples and Case Studies

Use real-life examples and case studies to illustrate the practical applications of your research findings. This makes the information tangible and relevant.

5. Relatable Examples from Popular Culture

Relate your research to pop culture, current events, or everyday experiences. This helps readers connect with the material on a personal level.

Examples of Interesting Topics to Research

To provide some inspiration, let’s explore a few intriguing research topics:

The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health

Examine the relationship between social media use and mental health, including topics like social comparison, cyberbullying, and the benefits of online support networks.

The Future of Renewable Energy

Research the latest advancements in renewable energy technologies, such as solar power, wind energy, and the feasibility of a global transition to sustainable energy sources.

The History of Women’s Suffrage

Delve into the historical struggles and milestones of the women’s suffrage movement, both in the United States and around the world.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

Investigate the applications of AI in healthcare, from diagnosis algorithms to patient data analysis and the ethical implications of AI in medical practice.

Strategies for Sustainable Business Practices

Examine business sustainability practices , exploring how companies can balance profit and environmental responsibility in an increasingly eco-conscious world.

Challenges you Might Face in Research

While you are looking for interesting topics to research, it’s important to be aware of the challenges:

- Avoiding Bias and Misinformation: Ensure your research is unbiased and based on credible sources. Critical thinking is key to avoiding misinformation.

- Ethical Considerations: Research involving humans or animals should follow ethical guidelines. Always prioritize ethical research practices.

- Data Collection and Analysis: Data collection can be time-consuming and challenging. Make sure to use appropriate data collection methods and robust analysis techniques.

- Staying Updated with Latest Research: Research is an ongoing process. Stay up-to-date with the latest research in your field to ensure the relevance and accuracy of your work.

Research is a gateway to knowledge, innovation, and solutions. Choosing interesting topics to research is the first step in this exciting journey. Whether you’re exploring the depths of science, the intricacies of culture, or the dynamics of business, there’s a captivating research topic waiting for you.

So, start your exploration, share your discoveries, and keep the flame of curiosity alive. The world is waiting to learn from your research.

Related Posts

Step by Step Guide on The Best Way to Finance Car

The Best Way on How to Get Fund For Business to Grow it Efficiently

How To Find A High-Quality Research Topic

6 steps to find & evaluate high-quality dissertation/thesis topics.

By: Caroline Osella (PhD, BA) and Derek Jansen (MBA) | July 2019

So, you’re finally nearing the end of your degree and it’s now time to find a suitable topic for your dissertation or thesis. Or perhaps you’re just starting out on your PhD research proposal and need to find a suitable area of research for your application proposal.

In this post, we’ll provide a straightforward 6-step process that you can follow to ensure you arrive at a high-quality research topic . Follow these steps and you will formulate a well-suited, well-defined core research question .

There’s a helpful clue already: your research ‘topic’ is best understood as a research question or a problem . Your aim is not to create an encyclopedia entry into your field, but rather to shed light on an acknowledged issue that’s being debated (or needs to be). Think research questions , not research topics (we’ll come back to this later).

Overview: How To Find A Research Topic

- Get an understanding of the research process

- Review previous dissertations from your university

- Review the academic literature to start the ideation process

- Identify your potential research questions (topics) and shortlist

- Narrow down, then evaluate your research topic shortlist

- Make the decision (and stick with it!)

Step 1: Understand the research process

It may sound horribly obvious, but it’s an extremely common mistake – students skip past the fundamentals straight to the ideation phase (and then pay dearly for it).

Start by looking at whatever handouts and instructions you’ve been given regarding what your university/department expects of a dissertation. For example, the course handbook, online information and verbal in-class instructions. I know it’s tempting to just dive into the ideation process, but it’s essential to start with the prescribed material first.

There are two important reasons for this:

First , you need to have a basic understanding of the research process , research methodologies , fieldwork options and analysis methods before you start the ideation process, or you will simply not be equipped to think about your own research adequately. If you don’t understand the basics of quantitative , qualitative and mixed methods BEFORE you start ideating, you’re wasting your time.

Second , your university/department will have specific requirements for your research – for example, requirements in terms of topic originality, word count, data requirements, ethical adherence , methodology, etc. If you are not aware of these from the outset, you will again end up wasting a lot of time on irrelevant ideas/topics.

So, the most important first step is to get your head around both the basics of research (especially methodologies), as well as your institution’s specific requirements . Don’t give in to the temptation to jump ahead before you do this. As a starting point, be sure to check out our free dissertation course.

Step 2: Review past dissertations/theses

Unless you’re undertaking a completely new course, there will be many, many students who have gone through the research process before and have produced successful dissertations, which you can use to orient yourself. This is hugely beneficial – imagine being able to see previous students’ assignments and essays when you were doing your coursework!

Take a look at some well-graded (65% and above) past dissertations from your course (ideally more recent ones, as university requirements may change over time). These are usually available in the university’s online library. Past dissertations will act as a helpful model for all kinds of things, from how long a bibliography needs to be, to what a good literature review looks like, through to what kinds of methods you can use – and how to leverage them to support your argument.

As you peruse past dissertations, ask yourself the following questions:

- What kinds of topics did these dissertations cover and how did they turn the topic into questions?

- How broad or narrow were the topics?

- How original were the topics? Were they truly groundbreaking or just a localised twist on well-established theory?

- How well justified were the topics? Did they seem important or just nice to know?

- How much literature did they draw on as a theoretical base? Was the literature more academic or applied in nature?

- What kinds of research methods did they use and what data did they draw on?

- How did they analyse that data and bring it into the discussion of the academic literature?

- Which of the dissertations are most readable to you – why? How were they presented?

- Can you see why these dissertations were successful? Can you relate what they’ve done back to the university’s instructions/brief?

Seeing a variety of dissertations (at least 5, ideally in your area of interest) will also help you understand whether your university has very rigid expectations in terms of structure and format , or whether they expect and allow variety in the number of chapters, chapter headings, order of content, style of presentation and so on.

Some departments accept graphic novels; some are willing to grade free-flow continental-philosophy style arguments; some want a highly rigid, standardised structure. Many offer a dissertation template , with information on how marks are split between sections. Check right away whether you have been given one of those templates – and if you do, then use it and don’t try to deviate or reinvent the wheel.

Step 3: Review the academic literature

Now that you (1) understand the research process, (2) understand your university’s specific requirements for your dissertation or thesis, and (3) have a feel for what a good dissertation looks like, you can start the ideation process. This is done by reviewing the current literature and looking for opportunities to add something original to the academic conversation.

Kick start the ideation process

So, where should you start your literature hunt? The best starting point is to get back to your modules. Look at your coursework and the assignments you did. Using your coursework is the best theoretical base, as you are assured that (1) the literature is of a high enough calibre for your university and (2) the topics are relevant to your specific course.

Start by identifying the modules that interested you the most and that you understood well (i.e. earned good marks for). What were your strongest assignments, essays or reports? Which areas within these were particularly interesting to you? For example, within a marketing module, you may have found consumer decision making or organisation trust to be interesting. Create a shortlist of those areas that you were both interested in and academically strong at. It’s no use picking an area that does not genuinely interest you – you’ll run out of motivation if you’re not excited by a topic.

Understand the current state of knowledge

Once you’ve done that, you need to get an understanding of the current state of the literature for your chosen interest areas. What you’re aiming to understand is this: what is the academic conversation here and what critical questions are yet unanswered? These unanswered questions are prime opportunities for a unique, meaningful research topic . A quick review of the literature on your favourite topics will help you understand this.

Grab your reading list from the relevant section of the modules, or simply enter the topics into Google Scholar . Skim-read 3-5 journal articles from the past 5 years which have at least 5 citations each (Google Scholar or a citations index will show you how many citations any given article has – i.e., how many other people have referred to it in their own bibliography). Also, check to see if your discipline has an ‘annual review’ type of journal, which gathers together surveys of the state of knowledge on a chosen topic. This can be a great tool for fast-tracking your understanding of the current state of the knowledge in any given area.

Start from your course’s reading list and work outwards. At the end of every journal article, you’ll find a reference list. Scan this reference list for more relevant articles and read those. Then repeat the process (known as snowballing) until you’ve built up a base of 20-30 quality articles per area of interest.

Absorb, don’t hunt

At this stage, your objective is to read and understand the current state of the theory for your area(s) of interest – you don’t need to be in topic-hunting mode yet. Don’t jump the gun and try to identify research topics before you are well familiarised with the literature.

As you read, try to understand what kinds of questions people are asking and how they are trying to answer them. What matters do the researchers agree on, and more importantly, what are they in disagreement about? Disagreements are prime research territory. Can you identify different ‘schools of thought’ or different ‘approaches’? Do you know what your own approach or slant is? What kinds of articles appeal to you and which ones bore you or leave you feeling like you’ve not really grasped them? Which ones interest you and point towards directions you’d like to research and know more about?

Once you understand the fundamental fact that academic knowledge is a conversation, things get easier.

Think of it like a party. There are groups of people in the room, enjoying conversations about various things. Which group do you want to join? You don’t want to be that person in the corner, talking to themself. And you don’t want to be the hanger-on, laughing at the big-shot’s jokes and repeating everything they say.

Do you want to join a large group and try to make a small contribution to what’s going on, or are you drawn to a smaller group that’s having a more niche conversation, but where you feel you might more easily find something original to contribute? How many conversations can you identify? Which ones feel closer to you and more attractive? Which ones repel you or leave you cold? Are there some that, frankly, you just don’t understand?

Now, choose a couple of groups who are discussing something you feel interested in and where you feel like you might want to contribute. You want to make your entry into this group by asking a question – a question that will make the other people in the group turn around and look at you, listen to you, and think, “That’s interesting”.

Your dissertation will be the process of setting that question and then trying to find at least a partial answer to that question – but don’t worry about that now. Right now, you need to work out what conversations are going on, whether any of them are related or overlapping, and which ones you might be able to walk into. I’ll explain how you find that question in the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 4: Identify potential research questions

Now that you have a decent understanding of the state of the literature in your area(s) of interest, it’s time to start developing your list of possible research topics. There are (at least) three approaches you can follow here, and they are not mutually exclusive:

Approach 1: Leverage the FRIN

Towards the end of most quality journal articles, you will find a section labelled “ further research ” or something similar. Generally, researchers will clearly outline where they feel further research is needed (FRIN), following on from their own research. So, essentially, every journal article presents you with a list of potential research opportunities.

Of course, only a handful of these will be both practical and of interest to you, so it’s not a quick-fix solution to finding a research topic. However, the benefit of going this route is that you will be able to find a genuinely original and meaningful research topic (which is particularly important for PhD-level research).

The upside to this approach is originality, but the downside is that you might not find something that really interests you , or that you have the means to execute. If you do go this route, make sure that you pay attention to the journal article dates, as the FRIN may already have been “solved” by other researchers if the article is old.

Approach 2: Put a context-based spin on an existing topic

The second option is to consider whether a theory which is already well established is relevant within a local or industry-specific context. For example, a theory about the antecedents (drivers) of trust is very well established, but there may be unique or uniquely important drivers within a specific national context or industry (for example, within the financial services industry in an emerging market).

If that industry or national context has not yet been covered by researchers and there is a good reason to believe there may be meaningful differences within that context, then you have an opportunity to take a unique angle on well-established theory, which can make for a great piece of research. It is however imperative that you have a good reason to believe that the existing theory may not be wholly relevant within your chosen context, or your research will not be justified.

The upside to this approach is that you can potentially find a topic that is “closer to home” and more relevant and interesting to you , while still being able to draw on a well-established body of theory. However, the downside is that this approach will likely not produce the level of originality as approach #1.

Approach 3: Uncensored brainstorming

The third option is to skip the FRIN, as well as the local/industry-specific angle and simply engage in a freeform brainstorming or mind-mapping session, using your newfound knowledge of the theory to formulate potential research ideas. What’s important here is that you do not censor yourself . However crazy, unfeasible, or plain stupid your topic appears – write it down. All that matters right now is that you are interested in this thing.

Next, try to turn the topic(s) into a question or problem. For example:

- What is the relationship between X, Y & Z?

- What are the drivers/antecedents of X?

- What are the outcomes of Y?

- What are the key success factors for Z?

Re-word your list of topics or issues into a list of questions . You might find at this stage that one research topic throws up three questions (which then become sub-topics and even new separate topics in their own right) and in so doing, the list grows. Let it. Don’t hold back or try to start evaluating your ideas yet – just let them flow onto paper.

Once you’ve got a few topics and questions on paper, check the literature again to see whether any of these have been covered by the existing research. Since you came up with these from scratch, there is a possibility that your original literature search did not cover them, so it’s important to revisit that phase to ensure that you’re familiar with the relevant literature for each idea. You may also then find that approach #1 and #2 can be used to build on these ideas.

Try use all three approaches

As mentioned earlier, the three approaches discussed here are not mutually exclusive. In fact, the more, the merrier. Hopefully, you manage to utilise all three, as this will give you the best odds of producing a rich list of ideas, which you can then narrow down and evaluate, which is the next step.

Step 5: Narrow down, then evaluate

By this stage, you should have a healthy list of research topics. Step away from the ideation and thinking for a few days, clear your mind. The key is to get some distance from your ideas, so that you can sit down with your list and review it with a more objective view. The unbridled ideation phase is over and now it’s time to take a reality check .

Look at your list and see if any options can be crossed off right away . Maybe you don’t want to do that topic anymore. Maybe the topic turned out to be too broad and threw up 20 hard to answer questions. Maybe all the literature you found about it was 30 years old and you suspect it might not be a very engaging contemporary issue . Maybe this topic is so over-researched that you’ll struggle to find anything fresh to say. Also, after stepping back, it’s quite common to notice that 2 or 3 of your topics are really the same one, the same question, which you’ve written down in slightly different ways. You can try to amalgamate these into one succinct topic.

Narrow down to the top 5, then evaluate

Now, take your streamlined list and narrow it down to the ‘top 5’ that interest you the most. Personal interest is your key evaluation criterion at this stage. Got your ‘top 5’? Great! Now, with a cool head and your best analytical mind engaged, go systematically through each option and evaluate them against the following criteria:

Research questions – what is the main research question, and what are the supporting sub-questions? It’s critically important that you can define these questions clearly and concisely. If you cannot do this, it means you haven’t thought the topic through sufficiently.

Originality – is the topic sufficiently original, as per your university’s originality requirements? Are you able to add something unique to the existing conversation? As mentioned earlier, originality can come in many forms, and it doesn’t mean that you need to find a completely new, cutting-edge topic. However, your university’s requirements should guide your decision-making here.

Importance – is the topic of real significance, or is it just a “nice to know”? If it’s significant, why? Who will benefit from finding the answer to your desired questions and how will they benefit? Justifying your research will be a key requirement for your research proposal , so it’s really important to develop a convincing argument here.

Literature – is there a contemporary (current) body of academic literature around this issue? Is there enough literature for you to base your investigation on, but not too much that the topic is “overdone”? Will you be able to navigate this literature or is it overwhelming?

Data requirements – What kind of data would you need access to in order to answer your key questions? Would you need to adopt a qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods approach to answer your questions? At this stage, you don’t need to be able to map out your exact research design, but you should be able to articulate how you would approach it in high-level terms. Will you use qual, quant or mixed methods? Why?

Feasibility – How feasible would it be to gather the data that would be needed in the time-frame that you have – and do you have the will power and the skills to do it? If you’re not confident with the theory, you don’t want something that’s going to draw you into a debate about the relative importance of epistemology and ontology. If you are shy, you won’t want to be doing ethnographic interviews. If you feel this question calls for a 100-person survey, do you have the time to plan, organise and conduct it and then analyse it? What will you do if you don’t get the response rate you expect? Be very realistic here and also ask advice from your supervisor and other experts – poor response rates are extremely common and can derail even the best research projects.

Personal attraction – On a scale of 1-10, how excited are you about this topic? Will addressing it add value to your life and/or career? Will undertaking the project help you build a skill you’ve previously wanted to work on (for example, interview skills, statistical analysis skills, software skills, etc.)?

The last point is particularly important. You will have to engage with your dissertation in a very sustained and deep way, face challenges and difficulties, and get it to completion. If you don’t start out enthusiastic about it, you’re setting yourself up for problems like ‘writer’s block’ or ‘burnout’ down the line. This is the reason personal interest was the sole evaluation criterion when we chose the top 5. So, don’t underestimate the importance of personal attraction to a topic – at the same time, don’t let personal attraction lead you to choose a topic that is not relevant to your course or feasible given your resources.

Narrow down to 3, then get human feedback

We’re almost at the finishing line. The next step is to narrow down to 2 or 3 shortlisted topics. No more! Write a short paragraph about each topic, addressing the following:

Firstly, WHAT will this study be about? Frame the topic as a question or a problem. Write it as a dissertation title. No more than two clauses and no more than 15 words. Less than 15 is better (go back to good journal articles for inspiration on appropriate title styles).

Secondly, WHY this is interesting (original) and important – as proven by existing academic literature? Are people talking about this and is there an acknowledged problem, debate or gap in the literature?

Lastly, HOW do you plan to answer the question? What sub-questions will you use? What methods does this call for and how competent and confident are you in those methods? Do you have the time to gather the data this calls for?

Show the shortlist and accompanying paragraphs to a couple of your peers from your course and also to an expert or two if at all possible (you’re welcome to reach out to us ), explaining what you will investigate, why this is original and important and how you will go about investigating it.

Once you’ve pitched your ideas, ask for the following thoughts :

- Which is most interesting and appealing to them?

- Why do they feel this way?

- What problems do they foresee with the execution of the research?

Take advice and feedback and sit on it for another day. Let it simmer in your mind overnight before you make the final decision.

Step 6: Make the decision (and stick with it!)

Then, make the commitment. Choose the one that you feel most confident about, having now considered both your opinion and the feedback from others.

Once you’ve made a decision, don’t doubt your judgement, don’t shift. Don’t be tempted by the ones you left behind. You’ve planned and thought things through, checked feasibility and now you can start. You have your research topic. Trust your own decision-making process and stick with it now. It’s time to get started on your research proposal!

Let’s recap…

In this post, I’ve proposed a straightforward 6-step plan to finding relevant research topic ideas and then narrowing them down to finally choose one winner. To recap:

- Understand the basics of academic research, as well as your university’s specific requirements for a dissertation, thesis or research project.

- Review previous dissertations for your course to get an idea of both topics and structure.

- Start the ideation process by familiarising yourself with the literature.

- Identify your potential research questions (topics).

- Narrow down your options, then evaluate systematically.

- Make your decision (and don’t look back!)

If you follow these steps, you’ll find that they also set you up for what’s coming next – both the proposal and the first three chapters of your dissertation. But that’s for future posts!

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

23 Comments

I would love to get a topic under teachers performance. I am a student of MSC Monitoring and Evaluations and I need a topic in the line of monitoring and evaluations

I just we put for some full notes that are payable

Thank you very much Dr Caroline

I need a project topics on transfer of learning

m a PhD Student I would like to be assisted inn formulating a title around: Internet of Things for online education in higher education – STEM (Science, technology, engineering and Mathematics, digital divide ) Thank you, would appreciate your guidance

Well structured guide on the topic… Good materials for beginners in research writing…

Hello Iam kindly seeking for help in formulating a researchable topic for masters degree program in line with teaching GRAPHIC ART

I read a thesis about a problem in a particular. Can I use the same topic just referring to my own country? Is that being original? The interview questions will mostly be the same as the other thesis.

Hi, thanks I managed to listen to the video so helpful indeed. I am currently an MBA student looking for a specific topic and I have different ideas that not sure they can be turned to be a study.

I am doing a Master of Theology in Pastoral Care and Counselling and I felt like doing research on Spiritual problem cause by substance abuse among Youth. Can I get help to formulate the Thesis Title in line with it…please

Hello, I am kindly seeking help in formulating a researchable topic for a National diploma program

As a beginner in research, I am very grateful for this well-structured material on research writing.

Hello, I watched the video and its very helpful. I’m a student in Nursing (degree). May you please help me with any research problems (in Namibian society or Nursing) that need to be evaluate or solved?

I have been greatly impacted. Thank you.

more than useful… there will be no justification if someone fails to get a topic for his thesis

I watched the video and its really helpful.

How can i started discovery

Analysing the significance of Integrated reporting in Zimbabwe. A case of institutional investors. this is my topic for PHD Accounting sciences need help with research questions

Excellent session that cleared lots of doubts.

Excellent session that cleared lots of doubts

It was a nice one thank you

Wow, This helped a lot not only with how to find a research topic but inspired me to kick it off from now, I am a final year student of environmental science. And have to complete my project in the coming six months.

I was really stressed and thinking about different topics that I don’t know nothing about and having more than a hundred topics in the baggage, couldn’t make the tradeoff among them, however, reading this scrubbed the fuzzy layer off my head and now it seems like really easy.

Thanks GRADCOACH, you saved me from getting into the rabbit hole.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Dissertation vs Thesis: What's the difference? - Grad Coach - […] we receive questions about dissertation and thesis writing on a daily basis – everything from how to find a…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Selecting a Research Topic: Overview

- Refine your topic

- Background information & facts

- Writing help

Here are some resources to refer to when selecting a topic and preparing to write a paper:

- MIT Writing and Communication Center "Providing free professional advice about all types of writing and speaking to all members of the MIT community."

- Search Our Collections Find books about writing. Search by subject for: english language grammar; report writing handbooks; technical writing handbooks

- Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation Online version of the book that provides examples and tips on grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and other writing rules.

- Select a topic

Choosing an interesting research topic is your first challenge. Here are some tips:

- Choose a topic that you are interested in! The research process is more relevant if you care about your topic.

- If your topic is too broad, you will find too much information and not be able to focus.

- Background reading can help you choose and limit the scope of your topic.

- Review the guidelines on topic selection outlined in your assignment. Ask your professor or TA for suggestions.

- Refer to lecture notes and required texts to refresh your knowledge of the course and assignment.

- Talk about research ideas with a friend. S/he may be able to help focus your topic by discussing issues that didn't occur to you at first.

- WHY did you choose the topic? What interests you about it? Do you have an opinion about the issues involved?

- WHO are the information providers on this topic? Who might publish information about it? Who is affected by the topic? Do you know of organizations or institutions affiliated with the topic?

- WHAT are the major questions for this topic? Is there a debate about the topic? Are there a range of issues and viewpoints to consider?

- WHERE is your topic important: at the local, national or international level? Are there specific places affected by the topic?

- WHEN is/was your topic important? Is it a current event or an historical issue? Do you want to compare your topic by time periods?

Table of contents

- Broaden your topic

- Information Navigator home

- Sources for facts - general

- Sources for facts - specific subjects

Start here for help

Ask Us Ask a question, make an appointment, give feedback, or visit us.

- Next: Refine your topic >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2021 2:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 113 great research paper topics.

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?

- What was the impact of the No Child Left Behind act?

- How does the US education system compare to education systems in other countries?

- What impact does mandatory physical education classes have on students' health?

- Which methods are most effective at reducing bullying in schools?

- Do homeschoolers who attend college do as well as students who attended traditional schools?

- Does offering tenure increase or decrease quality of teaching?

- How does college debt affect future life choices of students?

- Should graduate students be able to form unions?

- What are different ways to lower gun-related deaths in the US?

- How and why have divorce rates changed over time?

- Is affirmative action still necessary in education and/or the workplace?

- Should physician-assisted suicide be legal?

- How has stem cell research impacted the medical field?

- How can human trafficking be reduced in the United States/world?

- Should people be able to donate organs in exchange for money?

- Which types of juvenile punishment have proven most effective at preventing future crimes?

- Has the increase in US airport security made passengers safer?

- Analyze the immigration policies of certain countries and how they are similar and different from one another.

- Several states have legalized recreational marijuana. What positive and negative impacts have they experienced as a result?

- Do tariffs increase the number of domestic jobs?

- Which prison reforms have proven most effective?

- Should governments be able to censor certain information on the internet?

- Which methods/programs have been most effective at reducing teen pregnancy?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Keto diet?

- How effective are different exercise regimes for losing weight and maintaining weight loss?

- How do the healthcare plans of various countries differ from each other?

- What are the most effective ways to treat depression ?

- What are the pros and cons of genetically modified foods?

- Which methods are most effective for improving memory?

- What can be done to lower healthcare costs in the US?

- What factors contributed to the current opioid crisis?

- Analyze the history and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic .

- Are low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets more effective for weight loss?

- How much exercise should the average adult be getting each week?

- Which methods are most effective to get parents to vaccinate their children?

- What are the pros and cons of clean needle programs?

- How does stress affect the body?

- Discuss the history of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

- What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Who was responsible for the Iran-Contra situation?

- How has New Orleans and the government's response to natural disasters changed since Hurricane Katrina?

- What events led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

- What were the impacts of British rule in India ?

- Was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary?

- What were the successes and failures of the women's suffrage movement in the United States?

- What were the causes of the Civil War?

- How did Abraham Lincoln's assassination impact the country and reconstruction after the Civil War?

- Which factors contributed to the colonies winning the American Revolution?

- What caused Hitler's rise to power?

- Discuss how a specific invention impacted history.

- What led to Cleopatra's fall as ruler of Egypt?

- How has Japan changed and evolved over the centuries?

- What were the causes of the Rwandan genocide ?

- Why did Martin Luther decide to split with the Catholic Church?

- Analyze the history and impact of a well-known cult (Jonestown, Manson family, etc.)

- How did the sexual abuse scandal impact how people view the Catholic Church?

- How has the Catholic church's power changed over the past decades/centuries?

- What are the causes behind the rise in atheism/ agnosticism in the United States?

- What were the influences in Siddhartha's life resulted in him becoming the Buddha?

- How has media portrayal of Islam/Muslims changed since September 11th?

Science/Environment

- How has the earth's climate changed in the past few decades?

- How has the use and elimination of DDT affected bird populations in the US?

- Analyze how the number and severity of natural disasters have increased in the past few decades.

- Analyze deforestation rates in a certain area or globally over a period of time.

- How have past oil spills changed regulations and cleanup methods?

- How has the Flint water crisis changed water regulation safety?

- What are the pros and cons of fracking?

- What impact has the Paris Climate Agreement had so far?

- What have NASA's biggest successes and failures been?

- How can we improve access to clean water around the world?

- Does ecotourism actually have a positive impact on the environment?

- Should the US rely on nuclear energy more?

- What can be done to save amphibian species currently at risk of extinction?

- What impact has climate change had on coral reefs?

- How are black holes created?

- Are teens who spend more time on social media more likely to suffer anxiety and/or depression?

- How will the loss of net neutrality affect internet users?

- Analyze the history and progress of self-driving vehicles.

- How has the use of drones changed surveillance and warfare methods?

- Has social media made people more or less connected?

- What progress has currently been made with artificial intelligence ?

- Do smartphones increase or decrease workplace productivity?

- What are the most effective ways to use technology in the classroom?

- How is Google search affecting our intelligence?

- When is the best age for a child to begin owning a smartphone?

- Has frequent texting reduced teen literacy rates?

How to Write a Great Research Paper

Even great research paper topics won't give you a great research paper if you don't hone your topic before and during the writing process. Follow these three tips to turn good research paper topics into great papers.

#1: Figure Out Your Thesis Early

Before you start writing a single word of your paper, you first need to know what your thesis will be. Your thesis is a statement that explains what you intend to prove/show in your paper. Every sentence in your research paper will relate back to your thesis, so you don't want to start writing without it!

As some examples, if you're writing a research paper on if students learn better in same-sex classrooms, your thesis might be "Research has shown that elementary-age students in same-sex classrooms score higher on standardized tests and report feeling more comfortable in the classroom."

If you're writing a paper on the causes of the Civil War, your thesis might be "While the dispute between the North and South over slavery is the most well-known cause of the Civil War, other key causes include differences in the economies of the North and South, states' rights, and territorial expansion."

#2: Back Every Statement Up With Research

Remember, this is a research paper you're writing, so you'll need to use lots of research to make your points. Every statement you give must be backed up with research, properly cited the way your teacher requested. You're allowed to include opinions of your own, but they must also be supported by the research you give.

#3: Do Your Research Before You Begin Writing

You don't want to start writing your research paper and then learn that there isn't enough research to back up the points you're making, or, even worse, that the research contradicts the points you're trying to make!

Get most of your research on your good research topics done before you begin writing. Then use the research you've collected to create a rough outline of what your paper will cover and the key points you're going to make. This will help keep your paper clear and organized, and it'll ensure you have enough research to produce a strong paper.

What's Next?

Are you also learning about dynamic equilibrium in your science class? We break this sometimes tricky concept down so it's easy to understand in our complete guide to dynamic equilibrium .

Thinking about becoming a nurse practitioner? Nurse practitioners have one of the fastest growing careers in the country, and we have all the information you need to know about what to expect from nurse practitioner school .

Want to know the fastest and easiest ways to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius? We've got you covered! Check out our guide to the best ways to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit (or vice versa).

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction