Home > USC Columbia > Arts and Sciences > Comparative Literature > Comparative Literature Theses and Dissertations

Comparative Literature Theses and Dissertations

Theses/dissertations from 2023 2023.

Constructing Selfhood Through Fantasy: Mirror Women and Dreamscape Conversations in Olga Grushin’s Forty Rooms , Grace Marie Alger

Eugene O’Neill Returns: Theatrical Modernization and O’Neill Adaptations in 1980s China , Shuying Chen

The Supernatural in Migration: A Reflection on Senegalese Literature and Film , Rokhaya Aballa Dieng

Breaking Down the Human: Disintegration in Nineteenth-Century Fiction , Benjamin Mark Driscol

Archetypes Revisited: Investigating the Power of Universals in Soviet and Hollywood Cinema , Iana Guselnikova

Planting Rhizomes: Roots and Rhizomes in Maryse Condé’s Traversée de la Mangrove and Calixthe Beyala’s Le Petit Prince de Belleville , Rume Kpadamrophe

Violence, Rebellion, and Compromise in Chinese Campus Cinema ----- The Comparison of Cry Me a Sad River and Better Days , Chunyu Liu

Tracing Modern and Contemporary Sino-French Literary and Intellectual Relations: China, France, and Their Shifting Peripheries , Paul Timothy McElhinny

Truth And Knowledge In A Literary Text And Beyond: Lydia Chukovskaya’s Sofia Petrovna At The Intersections Between Selves, Culture, And Paratext , Angelina Rubina

From Roland to Gawain, or the Origin of Personified Knights , Clyde Tilson

Theses/Dissertations from 2022 2022

Afro-Diasporic Literatures of the United States and Brazil: Imaginaries, Counter-Narratives, and Black Feminism in the Americas , David E. S. Beek

The Pursuit of Good Food: The Alimentary Chronotope in Madame Bovary , Lauren Flinner

Form and Voice: Representing Contemporary Women’s Subaltern Experience in and Beyond China , Tingting Hu

Geography of a “Foreign” China: British Intellectuals’ Encounter With Chinese Spaces, 1920-1945 , Yuzhu Sun

Truth and Identity in Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov and Prince Myshkin , Gwendolyn Walker

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

Postcolonial Narrative and The Dialogic Imaginatio n: An Analysis of Early Francophone West African Fiction and Cinema , Seydina Mouhamed Diouf

The Rising of the Avant-Garde Movement In the 1980s People’s Republic of China: A Cultural Practice of the New Enlightenment , Jingsheng Zhang

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

L’ Entre- Monde : The Cinema of Alain Gomis , Guillaume Coly

Digesting Gender: Gendered Foodways in Modern Chinese Literature, 1890s–1940s , Zhuo Feng

The Deconstruction of Patriarchal War Narratives in Svetlana Alexievich’s The Unwomanly Face of War , Liubov Kartashova

Pushing the Limits of Black Atlantic and Hispanic Transatlantic Studies Through the Exploration of Three U.S. Afro-Latio Memoirs , Julia Luján

Taiwanese Postcolonial Identities and Environmentalism in Wu Ming-Yi’s the Stolen Bicycle , Chihchi Sunny Tsai

Games and Play of Dream of the Red Chamber , Jiayao Wang

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

Convertirse en Inmortal, 成仙 ChéngxiāN, Becoming Xian: Memory and Subjectivity in Cristina Rivera Garza’s Verde Shanghai , Katherine Paulette Elizabeth Crouch

Between Holy Russia and a Monkey: Darwin's Russian Literary and Philosophical Critics , Brendan G. Mooney

Emerging Populations: An Analysis of Twenty-First Century Caribbean Short Stories , Jeremy Patterson

Time, Space and Nonexistence in Joseph Brodsky's Poetry , Daria Smirnova

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

Through the Spaceship’s Window: A Bio-political Reading of 20th Century Latin American and Anglo-Saxon Science Fiction , Juan David Cruz

The Representations of Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Arab Women’s Literature: Elements of Subversion and Resignification. , Rima Sadek

Insects As Metaphors For Post-Civil War Reconstruction Of The Civic Body In Augustan Age Rome , Olivia Semler

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

Flannery O’Connor’s Art And The French Renouveau Catholique: A Comparative Exploration Of Contextual Resources For The Author’s Theological Aesthetics Of Sin and Grace , Stephen Allen Baarendse

The Quixotic Picaresque: Tricksters, Modernity, and Otherness in the Transatlantic Novel, or the Intertextual Rhizome of Lazarillo, Don Quijote, Huck Finn, and The Reivers , David Elijah Sinsabaugh Beek

Piglia and Russia: Russian Influences in Ricardo Piglia’s Nombre Falso , Carol E. Fruit Diouf

Beyond Life And Death Images Of Exceptional Women And Chinese Modernity , Wei Hu

Archival Resistance: A Comparative Reading of Ulysses and One Hundred Years of Solitude , Maria-Josee Mendez

Narrating the (Im)Migrant Experience: 21st Century African Fiction in the Age of Globalization , Bernard Ayo Oniwe

Narrating Pain and Freedom: Place and Identity in Modern Syrian Poetry (1970s-1990s) , Manar Shabouk

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

The Development of ‘Meaning’ in Literary Theory: A Comparative Critical Study , Mahmoud Mohamed Ali Ahmad Elkordy

Familial Betrayal And Trauma In Select Plays Of Shakespeare, Racine, And The Corneilles , Lynn Kramer

Evil Men Have No Songs: The Terrorist and Literatuer Boris Savinkov, 1879-1925 , Irina Vasilyeva Meier

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Resurrectio Mortuorum: Plato’s Use of Ἀνάγκη in the Dialogues , Joshua B. Gehling

Two Million "Butterflies" Searching for Home: Identity and Images of Korean Chinese in Ho Yon-Sun's Yanbian Narratives , Xiang Jin

The Trialectics Of Transnational Migrant Women’s Literature In The Writing Of Edwidge Danticat And Julia Alvarez , Jennifer Lynn Karash-Eastman

Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials , Isabel Meusen

Making the Irrational Rational: Nietzsche and the Problem of Knowledge in Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita , Brendan Mooney

Invective Drag: Talking Dirty in Catullus, Cicero, Horace, and Ovid , Casey Catherine Moore

Destination Hong Kong: Negotiating Locality in Hong Kong Novels 1945-1966 , Xianmin Shen

H.P. Lovecraft & The French Connection: Translation, Pulps and Literary History , Todd David Spaulding

Female Representations in Contemporary Postmodern War Novels of Spain and the United States: Women as Tools of Modern Catharsis in the Works of Javier Cercas and Tim O'Brien , Joseph P. Weil

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Poetic Appropriations in Vergil’s Aeneid: A Study in Three Themes Comprising Aeneas’ Character Development , Edgar Gordyn

Ekphrasis and Skepticism in Three Works of Shakespeare , Robert P. Irons

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

The Role of the Trickster Figure and Four Afro-Caribbean Meta-Tropes In the Realization of Agency by Three Slave Protagonists , David Sebastian Cross

Putting Place Back Into Displacement: Reevaluating Diaspora In the Contemporary Literature of Migration , Christiane Brigitte Steckenbiller

Using Singular Value Decomposition in Classics: Seeking Correlations in Horace, Juvenal and Persius against the Fragments of Lucilius , Thomas Whidden

Theses/Dissertations from 2012 2012

Decolonizing Transnational Subaltern Women: The Case of Kurasoleñas and New York Dominicanas , Florencia Cornet

Representation of Women In 19Th Century Popular Art and Literature: Forget Me Not and La Revista Moderna , Juan David Cruz

53x+m³=Ø? (Sex+Me=No Result?): Tropes of Asexuality in Literature and Film , Jana -. Fedtke

Argentina in The African Diaspora: Afro-Argentine And African American Cultural Production, Race, And Nation Building in the 19th Century , Julia Lujan

Male Subjectivity and Twenty-First Century German Cinema: Gender, National Idenity, and the Problem of Normalization , Richard Sell

Theses/Dissertations from 2011 2011

Blue Poets: Brilliant Poetry , Evangelin Grace Chapman-Wall

Sickness of the Spirit: A Comparative Study of Lu Xun and James Joyce , Liang Meng

Dryden and the Solution to Domination: Bonds of Love In the Conquest of Granada , Lydia FitzSimons Robins

Theses/Dissertations from 2010 2010

The Family As the New Collectivity of Belonging In the Fiction of Bharati Mukherjee and Jhumpa Lahiri , Sarbani Bose

Lyric Transcendence: the Sacred and the Real In Classical and Early-Modern Lyric. , Larry Grant Hamby

Abd al-Rahman Al-Kawakibi's Tabai` al-Istibdad wa Masari` al-Isti`bad (The Characteristics of Despotism and The Demises of Enslavement): A Translation and Introduction , Mohamad Subhi Hindi

Re-Visions: Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy In German and Italian Film and Literature , Kristina Stefanic Brown

Plato In Modern China: A Study of Contemporary Chinese Platonists , Leihua Weng

Making Victims: History, Memory, and Literature In Japan's Post-War Social Imaginary , Kimberly Wickham

Theses/Dissertations from 2009 2009

The Mirrored Body: Doubling and Replacement of the Feminine and androgynous Body In Hadia Said'S Artist and Haruki Murakami'S Sputnik Sweetheart , Fatmah Alsalamean

Making Monsters: The Monstrous-Feminine In Horace and Catullus , Casey Catherine Moore

Not Quite American, Not Quite European: Performing "Other" Claims to Exceptionality In Francoist Spain and the Jim Crow South , Brittany Powell

Developing Latin American Feminist Theory: Strategies of Resistance In the Novels of Luisa Valenzuela and Sandra Cisneros , Jennifer Lyn Slobodian

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Submissions

- Give us Feedback

- University Libraries

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Comparing & Contrasting

A compare and contrast paper discusses the similarities and differences between two or more topics. The paper should contain an introduction with a thesis statement, a body where the comparisons and contrasts are discussed, and a conclusion.

Address Both Similarities and Differences

Because this is a compare and contrast paper, both the similarities and differences should be discussed. This will require analysis on your part, as some topics will appear to be quite similar, and you will have to work to find the differing elements.

Make Sure You Have a Clear Thesis Statement

Just like any other essay, a compare and contrast essay needs a thesis statement. The thesis statement should not only tell your reader what you will do, but it should also address the purpose and importance of comparing and contrasting the material.

Use Clear Transitions

Transitions are important in compare and contrast essays, where you will be moving frequently between different topics or perspectives.

- Examples of transitions and phrases for comparisons: as well, similar to, consistent with, likewise, too

- Examples of transitions and phrases for contrasts: on the other hand, however, although, differs, conversely, rather than.

For more information, check out our transitions page.

Structure Your Paper

Consider how you will present the information. You could present all of the similarities first and then present all of the differences. Or you could go point by point and show the similarity and difference of one point, then the similarity and difference for another point, and so on.

Include Analysis

It is tempting to just provide summary for this type of paper, but analysis will show the importance of the comparisons and contrasts. For instance, if you are comparing two articles on the topic of the nursing shortage, help us understand what this will achieve. Did you find consensus between the articles that will support a certain action step for people in the field? Did you find discrepancies between the two that point to the need for further investigation?

Make Analogous Comparisons

When drawing comparisons or making contrasts, be sure you are dealing with similar aspects of each item. To use an old cliché, are you comparing apples to apples?

- Example of poor comparisons: Kubista studied the effects of a later start time on high school students, but Cook used a mixed methods approach. (This example does not compare similar items. It is not a clear contrast because the sentence does not discuss the same element of the articles. It is like comparing apples to oranges.)

- Example of analogous comparisons: Cook used a mixed methods approach, whereas Kubista used only quantitative methods. (Here, methods are clearly being compared, allowing the reader to understand the distinction.

Related Webinar

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Developing Arguments

- Next Page: Avoiding Logical Fallacies

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Comparative Studies

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 09 February 2018

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Mario Coccia 2 , 3 &

- Igor Benati 3

3451 Accesses

11 Citations

Comparative analysis ; Comparative approach

Comparative is a concept that derives from the verb “to compare” (the etymology is Latin comparare , derivation of par = equal, with prefix com- , it is a systematic comparison). Comparative studies are investigations to analyze and evaluate, with quantitative and qualitative methods, a phenomenon and/or facts among different areas, subjects, and/or objects to detect similarities and/or differences.

Introduction: Why Comparative Studies Are Important in Scientific Research

Natural sciences apply the method of controlled experimentation to test theories, whereas social and human sciences apply, in general, different approaches to support hypotheses. Comparative method is a process of analysing differences and/or similarities betwee two or more objects and/or subjects. Comparative studies are based on research techniques and strategies for drawing inferences about causation and/or association of factors that are similar or...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Benati I, Coccia M (2017) General trends and causes of high compensation of government managers in the OECD countries. Int J Public Adm. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2017.1318399

Benati I, Coccia M (2018) Rewards in Bureaucracy and Politics. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance –section Bureaucracy (edited by Ali Farazmand) Chapter No: 3417-1, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3417-1 , Springer International Publishing AG

Coccia M, Rolfo S (2007) How research policy changes can affect the organization and productivity of public research institutes. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Research and Practice, 9(3): 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980701494624

Coccia M, Rolfo S (2013) Human Resource Management and Organizational Behavior of Public Research Institutions. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(4): 256–268, https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2012.756889

Cooksey RW (2007) Illustrating statistical procedures. Tilde University Press, Prahran

Google Scholar

Gomm R, Hammersley M, Foster P (eds) (2000) Case study method. SAGE Publications, London

Hague R, Harrop M (2004) Comparative government and politics. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Levine CH, Peters BG, Thompson FJ (1990) Public administration: challenges, choices, consequences. Scott Foresman and Company, Glenview

Peters BG (1998) Comparative politics-theory and method. Macmillan Press, London

Peters BG, Pierre J (2016) Comparative governance: rediscovering the functional dimension of governing. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Mario Coccia

CNR – National Research Council of Italy, Torino, Italy

Mario Coccia & Igor Benati

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Igor Benati .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida, USA

Ali Farazmand

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Coccia, M., Benati, I. (2018). Comparative Studies. In: Farazmand, A. (eds) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1197-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1197-1

Received : 31 January 2018

Accepted : 03 February 2018

Published : 09 February 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-31816-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-31816-5

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Economics and Finance Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Comparative Essay

How to Write a Comparative Essay – A Complete Guide

10 min read

People also read

Learn How to Write an Editorial on Any Topic

Best Tips on How to Avoid Plagiarism

How to Write a Movie Review - Guide & Examples

A Complete Guide on How to Write a Summary for Students

Write Opinion Essay Like a Pro: A Detailed Guide

Evaluation Essay - Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

How to Write a Thematic Statement - Tips & Examples

How to Write a Bio - Quick Tips, Structure & Examples

How to Write a Synopsis – A Simple Format & Guide

Visual Analysis Essay - A Writing Guide with Format & Sample

List of Common Social Issues Around the World

Writing Character Analysis - Outline, Steps, and Examples

11 Common Types of Plagiarism Explained Through Examples

Article Review Writing: A Complete Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

A Detailed Guide on How to Write a Poem Step by Step

Detailed Guide on Appendix Writing: With Tips and Examples

Comparative essay is a common assignment for school and college students. Many students are not aware of the complexities of crafting a strong comparative essay.

If you too are struggling with this, don't worry!

In this blog, you will get a complete writing guide for comparative essay writing. From structuring formats to creative topics, this guide has it all.

So, keep reading!

- 1. What is a Comparative Essay?

- 2. Comparative Essay Structure

- 3. How to Start a Comparative Essay?

- 4. How to Write a Comparative Essay?

- 5. Comparative Essay Examples

- 6. Comparative Essay Topics

- 7. Tips for Writing A Good Comparative Essay

- 8. Transition Words For Comparative Essays

What is a Comparative Essay?

A comparative essay is a type of essay in which an essay writer compares at least two or more items. The author compares two subjects with the same relation in terms of similarities and differences depending on the assignment.

The main purpose of the comparative essay is to:

- Highlight the similarities and differences in a systematic manner.

- Provide great clarity of the subject to the readers.

- Analyze two things and describe their advantages and drawbacks.

A comparative essay is also known as compare and contrast essay or a comparison essay. It analyzes two subjects by either comparing them, contrasting them, or both. The Venn diagram is the best tool for writing a paper about the comparison between two subjects.

Moreover, a comparative analysis essay discusses the similarities and differences of themes, items, events, views, places, concepts, etc. For example, you can compare two different novels (e.g., The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Red Badge of Courage).

However, a comparative essay is not limited to specific topics. It covers almost every topic or subject with some relation.

Comparative Essay Structure

A good comparative essay is based on how well you structure your essay. It helps the reader to understand your essay better.

The structure is more important than what you write. This is because it is necessary to organize your essay so that the reader can easily go through the comparisons made in an essay.

The following are the two main methods in which you can organize your comparative essay.

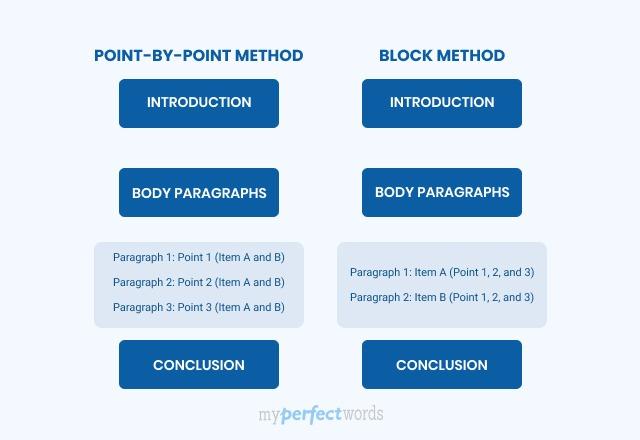

Point-by-Point Method

The point-by-point or alternating method provides a detailed overview of the items that you are comparing. In this method, organize items in terms of similarities and differences.

This method makes the writing phase easy for the writer to handle two completely different essay subjects. It is highly recommended where some depth and detail are required.

Below given is the structure of the point-by-point method.

Block Method

The block method is the easiest as compared to the point-by-point method. In this method, you divide the information in terms of parameters. It means that the first paragraph compares the first subject and all their items, then the second one compares the second, and so on.

However, make sure that you write the subject in the same order. This method is best for lengthy essays and complicated subjects.

Here is the structure of the block method.

Therefore, keep these methods in mind and choose the one according to the chosen subject.

Mixed Paragraphs Method

In this method, one paragraph explains one aspect of the subject. As a writer, you will handle one point at a time and one by one. This method is quite beneficial as it allows you to give equal weightage to each subject and help the readers identify the point of comparison easily.

How to Start a Comparative Essay?

Here, we have gathered some steps that you should follow to start a well-written comparative essay.

Choose a Topic

The foremost step in writing a comparative essay is to choose a suitable topic.

Choose a topic or theme that is interesting to write about and appeals to the reader.

An interesting essay topic motivates the reader to know about the subject. Also, try to avoid complicated topics for your comparative essay.

Develop a List of Similarities and Differences

Create a list of similarities and differences between two subjects that you want to include in the essay. Moreover, this list helps you decide the basis of your comparison by constructing your initial plan.

Evaluate the list and establish your argument and thesis statement .

Establish the Basis for Comparison

The basis for comparison is the ground for you to compare the subjects. In most cases, it is assigned to you, so check your assignment or prompt.

Furthermore, the main goal of the comparison essay is to inform the reader of something interesting. It means that your subject must be unique to make your argument interesting.

Do the Research

In this step, you have to gather information for your subject. If your comparative essay is about social issues, historical events, or science-related topics, you must do in-depth research.

However, make sure that you gather data from credible sources and cite them properly in the essay.

Create an Outline

An essay outline serves as a roadmap for your essay, organizing key elements into a structured format.

With your topic, list of comparisons, basis for comparison, and research in hand, the next step is to create a comprehensive outline.

Here is a standard comparative essay outline:

How to Write a Comparative Essay?

Now that you have the basic information organized in an outline, you can get started on the writing process.

Here are the essential parts of a comparative essay:

Comparative Essay Introduction

Start off by grabbing your reader's attention in the introduction . Use something catchy, like a quote, question, or interesting fact about your subjects.

Then, give a quick background so your reader knows what's going on.

The most important part is your thesis statement, where you state the main argument , the basis for comparison, and why the comparison is significant.

This is what a typical thesis statement for a comparative essay looks like:

Comparative Essay Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs are where you really get into the details of your subjects. Each paragraph should focus on one thing you're comparing.

Start by talking about the first point of comparison. Then, go on to the next points. Make sure to talk about two to three differences to give a good picture.

After that, switch gears and talk about the things they have in common. Just like you discussed three differences, try to cover three similarities.

This way, your essay stays balanced and fair. This approach helps your reader understand both the ways your subjects are different and the ways they are similar. Keep it simple and clear for a strong essay.

Comparative Essay Conclusion

In your conclusion , bring together the key insights from your analysis to create a strong and impactful closing.

Consider the broader context or implications of the subjects' differences and similarities. What do these insights reveal about the broader themes or ideas you're exploring?

Discuss the broader implications of these findings and restate your thesis. Avoid introducing new information and end with a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression.

Below is the detailed comparative essay template format for you to understand better.

Comparative Essay Format

Comparative Essay Examples

Have a look at these comparative essay examples pdf to get an idea of the perfect essay.

Comparative Essay on Summer and Winter

Comparative Essay on Books vs. Movies

Comparative Essay Sample

Comparative Essay Thesis Example

Comparative Essay on Football vs Cricket

Comparative Essay on Pet and Wild Animals

Comparative Essay Topics

Comparative essay topics are not very difficult or complex. Check this list of essay topics and pick the one that you want to write about.

- How do education and employment compare?

- Living in a big city or staying in a village.

- The school principal or college dean.

- New Year vs. Christmas celebration.

- Dried Fruit vs. Fresh. Which is better?

- Similarities between philosophy and religion.

- British colonization and Spanish colonization.

- Nuclear power for peace or war?

- Bacteria or viruses.

- Fast food vs. homemade food.

Tips for Writing A Good Comparative Essay

Writing a compelling comparative essay requires thoughtful consideration and strategic planning. Here are some valuable tips to enhance the quality of your comparative essay:

- Clearly define what you're comparing, like themes or characters.

- Plan your essay structure using methods like point-by-point or block paragraphs.

- Craft an introduction that introduces subjects and states your purpose.

- Ensure an equal discussion of both similarities and differences.

- Use linking words for seamless transitions between paragraphs.

- Gather credible information for depth and authenticity.

- Use clear and simple language, avoiding unnecessary jargon.

- Dedicate each paragraph to a specific point of comparison.

- Summarize key points, restate the thesis, and emphasize significance.

- Thoroughly check for clarity, coherence, and correct any errors.

Transition Words For Comparative Essays

Transition words are crucial for guiding your reader through the comparative analysis. They help establish connections between ideas and ensure a smooth flow in your essay.

Here are some transition words and phrases to improve the flow of your comparative essay:

Transition Words for Similarities

- Correspondingly

- In the same vein

- In like manner

- In a similar fashion

- In tandem with

Transition Words for Differences

- On the contrary

- In contrast

- Nevertheless

- In spite of

- Notwithstanding

- On the flip side

- In contradistinction

Check out this blog listing more transition words that you can use to enhance your essay’s coherence!

In conclusion, now that you have the important steps and helpful tips to write a good comparative essay, you can start working on your own essay.

However, if you find it tough to begin, you can always hire our college paper writing service .

Our skilled writers can handle any type of essay or assignment you need. So, don't wait—place your order now and make your academic journey easier!

Frequently Asked Question

How long is a comparative essay.

A comparative essay is 4-5 pages long, but it depends on your chosen idea and topic.

How do you end a comparative essay?

Here are some tips that will help you to end the comparative essay.

- Restate the thesis statement

- Wrap up the entire essay

- Highlight the main points

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Honors Theses - Examples

1. A Carne e a Navalha : Self-Reflective Representation of Marginalized Characters in Brazilian Narrative by Clarice Lispector, Eduardo Coutinho, and Racionias MCs by Corina Ahlswede, 2018

2. The Travel of Clear Waters: A Case Study on the Afterlife of a Poem by Kaiyu Xu, 2019

3. Examining Blurring: An Anti-anthropocentric Comparative Study of European Vampirism and Shuten Dōji by Yisheng Tang, 2018

4. The Revolutionary Potential of Mythology by Zachary Morgan, 2017

5. “Use your authority!”: Pedagogy in William Shakespeare’s The Tempest by Wesley Boyko, 2018

6. Train of Thought by Yana Zlochistaya, 2017

7. “Between here and there”: Assertion of the Poetic Voice in the Poetry of Rita Bouvier and Marilyn Dumont by Molly Kearnan, 2020

8. Unveiling the Invaluable: Female Voices, Affective Labor, and Play in Reḵẖtī Poetry by Elizabeth Gobbo, 2020

9. The Prospect Garden of Forking Paths: Reading Jorge Luis Borges’s Fiction through Cao Xueqin’s Honglou meng and Buddhism by Jenny Chen, 2023

10. La Politisation du Féminisme Littéraire et de la Différence Sexuelle chez Woolf et Cixous by Samantha Bonadio, 2023

11. AENEAS’ EMPIRE AND CÉSAIRE’S EVASION: BLACK POETICS AS REFUSAL AND REDACTION IN CAHIER D’UN RETOUR AU PAYS NATAL by des jackson, 2023

- Undergraduate Program

- Program Requirements

- Study Abroad

- Transfer Students

- Comp Lit Undergraduate Journal

- Annual Research Symposium

- Why I Majored in Comp Lit

- Undergrad Peer Representatives

- Commencement

Comparative Research

Although not everyone would agree, comparing is not always bad. Comparing things can also give you a handful of benefits. For instance, there are times in our life where we feel lost. You may not be getting the job that you want or have the sexy body that you have been aiming for a long time now. Then, you happen to cross path with an old friend of yours, who happened to get the job that you always wanted. This scenario may put your self-esteem down, knowing that this friend got what you want, while you didn’t. Or you can choose to look at your friend as an example that your desire is actually attainable. Come up with a plan to achieve your personal development goal . Perhaps, ask for tips from this person or from the people who inspire you. According to the article posted in brit.co , licensed master social worker and therapist Kimberly Hershenson said that comparing yourself to someone successful can be an excellent self-motivation to work on your goals.

Aside from self-improvement, as a researcher, you should know that comparison is an essential method in scientific studies, such as experimental research and descriptive research . Through this method, you can uncover the relationship between two or more variables of your project in the form of comparative analysis .

What is Comparative Research?

Aiming to compare two or more variables of an experiment project, experts usually apply comparative research examples in social sciences to compare countries and cultures across a particular area or the entire world. Despite its proven effectiveness, you should keep it in mind that some states have different disciplines in sharing data. Thus, it would help if you consider the affecting factors in gathering specific information.

Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods in Comparative Studies

In comparing variables, the statistical and mathematical data collection, and analysis that quantitative research methodology naturally uses to uncover the correlational connection of the variables, can be essential. Additionally, since quantitative research requires a specific research question, this method can help you can quickly come up with one particular comparative research question.

The goal of comparative research is drawing a solution out of the similarities and differences between the focused variables. Through non-experimental or qualitative research , you can include this type of research method in your comparative research design.

13+ Comparative Research Examples

Know more about comparative research by going over the following examples. You can download these zipped documents in PDF and MS Word formats.

1. Comparative Research Report Template

- Google Docs

Size: 113 KB

2. Business Comparative Research Template

Size: 69 KB

3. Comparative Market Research Template

Size: 172 KB

4. Comparative Research Strategies Example

5. Comparative Research in Anthropology Example

Size: 192 KB

6. Sample Comparative Research Example

Size: 516 KB

7. Comparative Area Research Example

8. Comparative Research on Women’s Emplyment Example

Size: 290 KB

9. Basic Comparative Research Example

Size: 19 KB

10. Comparative Research in Medical Treatments Example

11. Comparative Research in Education Example

Size: 455 KB

12. Formal Comparative Research Example

Size: 244 KB

13. Comparative Research Designs Example

Size: 259 KB

14. Casual Comparative Research in DOC

Best Practices in Writing an Essay for Comparative Research in Visual Arts

If you are going to write an essay for a comparative research examples paper, this section is for you. You must know that there are inevitable mistakes that students do in essay writing . To avoid those mistakes, follow the following pointers.

1. Compare the Artworks Not the Artists

One of the mistakes that students do when writing a comparative essay is comparing the artists instead of artworks. Unless your instructor asked you to write a biographical essay, focus your writing on the works of the artists that you choose.

2. Consult to Your Instructor

There is broad coverage of information that you can find on the internet for your project. Some students, however, prefer choosing the images randomly. In doing so, you may not create a successful comparative study. Therefore, we recommend you to discuss your selections with your teacher.

3. Avoid Redundancy

It is common for the students to repeat the ideas that they have listed in the comparison part. Keep it in mind that the spaces for this activity have limitations. Thus, it is crucial to reserve each space for more thoroughly debated ideas.

4. Be Minimal

Unless instructed, it would be practical if you only include a few items(artworks). In this way, you can focus on developing well-argued information for your study.

5. Master the Assessment Method and the Goals of the Project

We get it. You are doing this project because your instructor told you so. However, you can make your study more valuable by understanding the goals of doing the project. Know how you can apply this new learning. You should also know the criteria that your teachers use to assess your output. It will give you a chance to maximize the grade that you can get from this project.

Comparing things is one way to know what to improve in various aspects. Whether you are aiming to attain a personal goal or attempting to find a solution to a certain task, you can accomplish it by knowing how to conduct a comparative study. Use this content as a tool to expand your knowledge about this research methodology .

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 10 methods for comparative studies.

Francis Lau and Anne Holbrook .

10.1. Introduction

In eHealth evaluation, comparative studies aim to find out whether group differences in eHealth system adoption make a difference in important outcomes. These groups may differ in their composition, the type of system in use, and the setting where they work over a given time duration. The comparisons are to determine whether significant differences exist for some predefined measures between these groups, while controlling for as many of the conditions as possible such as the composition, system, setting and duration.

According to the typology by Friedman and Wyatt (2006) , comparative studies take on an objective view where events such as the use and effect of an eHealth system can be defined, measured and compared through a set of variables to prove or disprove a hypothesis. For comparative studies, the design options are experimental versus observational and prospective versus retrospective. The quality of eHealth comparative studies depends on such aspects of methodological design as the choice of variables, sample size, sources of bias, confounders, and adherence to quality and reporting guidelines.

In this chapter we focus on experimental studies as one type of comparative study and their methodological considerations that have been reported in the eHealth literature. Also included are three case examples to show how these studies are done.

10.2. Types of Comparative Studies

Experimental studies are one type of comparative study where a sample of participants is identified and assigned to different conditions for a given time duration, then compared for differences. An example is a hospital with two care units where one is assigned a cpoe system to process medication orders electronically while the other continues its usual practice without a cpoe . The participants in the unit assigned to the cpoe are called the intervention group and those assigned to usual practice are the control group. The comparison can be performance or outcome focused, such as the ratio of correct orders processed or the occurrence of adverse drug events in the two groups during the given time period. Experimental studies can take on a randomized or non-randomized design. These are described below.

10.2.1. Randomized Experiments

In a randomized design, the participants are randomly assigned to two or more groups using a known randomization technique such as a random number table. The design is prospective in nature since the groups are assigned concurrently, after which the intervention is applied then measured and compared. Three types of experimental designs seen in eHealth evaluation are described below ( Friedman & Wyatt, 2006 ; Zwarenstein & Treweek, 2009 ).

Randomized controlled trials ( rct s) – In rct s participants are randomly assigned to an intervention or a control group. The randomization can occur at the patient, provider or organization level, which is known as the unit of allocation. For instance, at the patient level one can randomly assign half of the patients to receive emr reminders while the other half do not. At the provider level, one can assign half of the providers to receive the reminders while the other half continues with their usual practice. At the organization level, such as a multisite hospital, one can randomly assign emr reminders to some of the sites but not others. Cluster randomized controlled trials ( crct s) – In crct s, clusters of participants are randomized rather than by individual participant since they are found in naturally occurring groups such as living in the same communities. For instance, clinics in one city may be randomized as a cluster to receive emr reminders while clinics in another city continue their usual practice. Pragmatic trials – Unlike rct s that seek to find out if an intervention such as a cpoe system works under ideal conditions, pragmatic trials are designed to find out if the intervention works under usual conditions. The goal is to make the design and findings relevant to and practical for decision-makers to apply in usual settings. As such, pragmatic trials have few criteria for selecting study participants, flexibility in implementing the intervention, usual practice as the comparator, the same compliance and follow-up intensity as usual practice, and outcomes that are relevant to decision-makers.

10.2.2. Non-randomized Experiments

Non-randomized design is used when it is neither feasible nor ethical to randomize participants into groups for comparison. It is sometimes referred to as a quasi-experimental design. The design can involve the use of prospective or retrospective data from the same or different participants as the control group. Three types of non-randomized designs are described below ( Harris et al., 2006 ).

Intervention group only with pretest and post-test design – This design involves only one group where a pretest or baseline measure is taken as the control period, the intervention is implemented, and a post-test measure is taken as the intervention period for comparison. For example, one can compare the rates of medication errors before and after the implementation of a cpoe system in a hospital. To increase study quality, one can add a second pretest period to decrease the probability that the pretest and post-test difference is due to chance, such as an unusually low medication error rate in the first pretest period. Other ways to increase study quality include adding an unrelated outcome such as patient case-mix that should not be affected, removing the intervention to see if the difference remains, and removing then re-implementing the intervention to see if the differences vary accordingly. Intervention and control groups with post-test design – This design involves two groups where the intervention is implemented in one group and compared with a second group without the intervention, based on a post-test measure from both groups. For example, one can implement a cpoe system in one care unit as the intervention group with a second unit as the control group and compare the post-test medication error rates in both units over six months. To increase study quality, one can add one or more pretest periods to both groups, or implement the intervention to the control group at a later time to measure for similar but delayed effects. Interrupted time series ( its ) design – In its design, multiple measures are taken from one group in equal time intervals, interrupted by the implementation of the intervention. The multiple pretest and post-test measures decrease the probability that the differences detected are due to chance or unrelated effects. An example is to take six consecutive monthly medication error rates as the pretest measures, implement the cpoe system, then take another six consecutive monthly medication error rates as the post-test measures for comparison in error rate differences over 12 months. To increase study quality, one may add a concurrent control group for comparison to be more convinced that the intervention produced the change.

10.3. Methodological Considerations

The quality of comparative studies is dependent on their internal and external validity. Internal validity refers to the extent to which conclusions can be drawn correctly from the study setting, participants, intervention, measures, analysis and interpretations. External validity refers to the extent to which the conclusions can be generalized to other settings. The major factors that influence validity are described below.

10.3.1. Choice of Variables

Variables are specific measurable features that can influence validity. In comparative studies, the choice of dependent and independent variables and whether they are categorical and/or continuous in values can affect the type of questions, study design and analysis to be considered. These are described below ( Friedman & Wyatt, 2006 ).

Dependent variables – This refers to outcomes of interest; they are also known as outcome variables. An example is the rate of medication errors as an outcome in determining whether cpoe can improve patient safety. Independent variables – This refers to variables that can explain the measured values of the dependent variables. For instance, the characteristics of the setting, participants and intervention can influence the effects of cpoe . Categorical variables – This refers to variables with measured values in discrete categories or levels. Examples are the type of providers (e.g., nurses, physicians and pharmacists), the presence or absence of a disease, and pain scale (e.g., 0 to 10 in increments of 1). Categorical variables are analyzed using non-parametric methods such as chi-square and odds ratio. Continuous variables – This refers to variables that can take on infinite values within an interval limited only by the desired precision. Examples are blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature. Continuous variables are analyzed using parametric methods such as t -test, analysis of variance or multiple regression.

10.3.2. Sample Size

Sample size is the number of participants to include in a study. It can refer to patients, providers or organizations depending on how the unit of allocation is defined. There are four parts to calculating sample size. They are described below ( Noordzij et al., 2010 ).

Significance level – This refers to the probability that a positive finding is due to chance alone. It is usually set at 0.05, which means having a less than 5% chance of drawing a false positive conclusion. Power – This refers to the ability to detect the true effect based on a sample from the population. It is usually set at 0.8, which means having at least an 80% chance of drawing a correct conclusion. Effect size – This refers to the minimal clinically relevant difference that can be detected between comparison groups. For continuous variables, the effect is a numerical value such as a 10-kilogram weight difference between two groups. For categorical variables, it is a percentage such as a 10% difference in medication error rates. Variability – This refers to the population variance of the outcome of interest, which is often unknown and is estimated by way of standard deviation ( sd ) from pilot or previous studies for continuous outcome.

Sample Size Equations for Comparing Two Groups with Continuous and Categorical Outcome Variables.

An example of sample size calculation for an rct to examine the effect of cds on improving systolic blood pressure of hypertensive patients is provided in the Appendix. Refer to the Biomath website from Columbia University (n.d.) for a simple Web-based sample size / power calculator.

10.3.3. Sources of Bias

There are five common sources of biases in comparative studies. They are selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting biases ( Higgins & Green, 2011 ). These biases, and the ways to minimize them, are described below ( Vervloet et al., 2012 ).

Selection or allocation bias – This refers to differences between the composition of comparison groups in terms of the response to the intervention. An example is having sicker or older patients in the control group than those in the intervention group when evaluating the effect of emr reminders. To reduce selection bias, one can apply randomization and concealment when assigning participants to groups and ensure their compositions are comparable at baseline. Performance bias – This refers to differences between groups in the care they received, aside from the intervention being evaluated. An example is the different ways by which reminders are triggered and used within and across groups such as electronic, paper and phone reminders for patients and providers. To reduce performance bias, one may standardize the intervention and blind participants from knowing whether an intervention was received and which intervention was received. Detection or measurement bias – This refers to differences between groups in how outcomes are determined. An example is where outcome assessors pay more attention to outcomes of patients known to be in the intervention group. To reduce detection bias, one may blind assessors from participants when measuring outcomes and ensure the same timing for assessment across groups. Attrition bias – This refers to differences between groups in ways that participants are withdrawn from the study. An example is the low rate of participant response in the intervention group despite having received reminders for follow-up care. To reduce attrition bias, one needs to acknowledge the dropout rate and analyze data according to an intent-to-treat principle (i.e., include data from those who dropped out in the analysis). Reporting bias – This refers to differences between reported and unreported findings. Examples include biases in publication, time lag, citation, language and outcome reporting depending on the nature and direction of the results. To reduce reporting bias, one may make the study protocol available with all pre-specified outcomes and report all expected outcomes in published results.

10.3.4. Confounders

Confounders are factors other than the intervention of interest that can distort the effect because they are associated with both the intervention and the outcome. For instance, in a study to demonstrate whether the adoption of a medication order entry system led to lower medication costs, there can be a number of potential confounders that can affect the outcome. These may include severity of illness of the patients, provider knowledge and experience with the system, and hospital policy on prescribing medications ( Harris et al., 2006 ). Another example is the evaluation of the effect of an antibiotic reminder system on the rate of post-operative deep venous thromboses ( dvt s). The confounders can be general improvements in clinical practice during the study such as prescribing patterns and post-operative care that are not related to the reminders ( Friedman & Wyatt, 2006 ).

To control for confounding effects, one may consider the use of matching, stratification and modelling. Matching involves the selection of similar groups with respect to their composition and behaviours. Stratification involves the division of participants into subgroups by selected variables, such as comorbidity index to control for severity of illness. Modelling involves the use of statistical techniques such as multiple regression to adjust for the effects of specific variables such as age, sex and/or severity of illness ( Higgins & Green, 2011 ).

10.3.5. Guidelines on Quality and Reporting

There are guidelines on the quality and reporting of comparative studies. The grade (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) guidelines provide explicit criteria for rating the quality of studies in randomized trials and observational studies ( Guyatt et al., 2011 ). The extended consort (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) Statements for non-pharmacologic trials ( Boutron, Moher, Altman, Schulz, & Ravaud, 2008 ), pragmatic trials ( Zwarestein et al., 2008 ), and eHealth interventions ( Baker et al., 2010 ) provide reporting guidelines for randomized trials.

The grade guidelines offer a system of rating quality of evidence in systematic reviews and guidelines. In this approach, to support estimates of intervention effects rct s start as high-quality evidence and observational studies as low-quality evidence. For each outcome in a study, five factors may rate down the quality of evidence. The final quality of evidence for each outcome would fall into one of high, moderate, low, and very low quality. These factors are listed below (for more details on the rating system, refer to Guyatt et al., 2011 ).

Design limitations – For rct s they cover the lack of allocation concealment, lack of blinding, large loss to follow-up, trial stopped early or selective outcome reporting. Inconsistency of results – Variations in outcomes due to unexplained heterogeneity. An example is the unexpected variation of effects across subgroups of patients by severity of illness in the use of preventive care reminders. Indirectness of evidence – Reliance on indirect comparisons due to restrictions in study populations, intervention, comparator or outcomes. An example is the 30-day readmission rate as a surrogate outcome for quality of computer-supported emergency care in hospitals. Imprecision of results – Studies with small sample size and few events typically would have wide confidence intervals and are considered of low quality. Publication bias – The selective reporting of results at the individual study level is already covered under design limitations, but is included here for completeness as it is relevant when rating quality of evidence across studies in systematic reviews.

The original consort Statement has 22 checklist items for reporting rct s. For non-pharmacologic trials extensions have been made to 11 items. For pragmatic trials extensions have been made to eight items. These items are listed below. For further details, readers can refer to Boutron and colleagues (2008) and the consort website ( consort , n.d.).

Title and abstract – one item on the means of randomization used. Introduction – one item on background, rationale, and problem addressed by the intervention. Methods – 10 items on participants, interventions, objectives, outcomes, sample size, randomization (sequence generation, allocation concealment, implementation), blinding (masking), and statistical methods. Results – seven items on participant flow, recruitment, baseline data, numbers analyzed, outcomes and estimation, ancillary analyses, adverse events. Discussion – three items on interpretation, generalizability, overall evidence.

The consort Statement for eHealth interventions describes the relevance of the consort recommendations to the design and reporting of eHealth studies with an emphasis on Internet-based interventions for direct use by patients, such as online health information resources, decision aides and phr s. Of particular importance is the need to clearly define the intervention components, their role in the overall care process, target population, implementation process, primary and secondary outcomes, denominators for outcome analyses, and real world potential (for details refer to Baker et al., 2010 ).

10.4. Case Examples

10.4.1. pragmatic rct in vascular risk decision support.

Holbrook and colleagues (2011) conducted a pragmatic rct to examine the effects of a cds intervention on vascular care and outcomes for older adults. The study is summarized below.

Setting – Community-based primary care practices with emr s in one Canadian province. Participants – English-speaking patients 55 years of age or older with diagnosed vascular disease, no cognitive impairment and not living in a nursing home, who had a provider visit in the past 12 months. Intervention – A Web-based individualized vascular tracking and advice cds system for eight top vascular risk factors and two diabetic risk factors, for use by both providers and patients and their families. Providers and staff could update the patient’s profile at any time and the cds algorithm ran nightly to update recommendations and colour highlighting used in the tracker interface. Intervention patients had Web access to the tracker, a print version mailed to them prior to the visit, and telephone support on advice. Design – Pragmatic, one-year, two-arm, multicentre rct , with randomization upon patient consent by phone, using an allocation-concealed online program. Randomization was by patient with stratification by provider using a block size of six. Trained reviewers examined emr data and conducted patient telephone interviews to collect risk factors, vascular history, and vascular events. Providers completed questionnaires on the intervention at study end. Patients had final 12-month lab checks on urine albumin, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and A1c levels. Outcomes – Primary outcome was based on change in process composite score ( pcs ) computed as the sum of frequency-weighted process score for each of the eight main risk factors with a maximum score of 27. The process was considered met if a risk factor had been checked. pcs was measured at baseline and study end with the difference as the individual primary outcome scores. The main secondary outcome was a clinical composite score ( ccs ) based on the same eight risk factors compared in two ways: a comparison of the mean number of clinical variables on target and the percentage of patients with improvement between the two groups. Other secondary outcomes were actual vascular event rates, individual pcs and ccs components, ratings of usability, continuity of care, patient ability to manage vascular risk, and quality of life using the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire ( eq-5D) . Analysis – 1,100 patients were needed to achieve 90% power in detecting a one-point pcs difference between groups with a standard deviation of five points, two-tailed t -test for mean difference at 5% significance level, and a withdrawal rate of 10%. The pcs , ccs and eq-5D scores were analyzed using a generalized estimating equation accounting for clustering within providers. Descriptive statistics and χ2 tests or exact tests were done with other outcomes. Findings – 1,102 patients and 49 providers enrolled in the study. The intervention group with 545 patients had significant pcs improvement with a difference of 4.70 ( p < .001) on a 27-point scale. The intervention group also had significantly higher odds of rating improvements in their continuity of care (4.178, p < .001) and ability to improve their vascular health (3.07, p < .001). There was no significant change in vascular events, clinical variables and quality of life. Overall the cds intervention led to reduced vascular risks but not to improved clinical outcomes in a one-year follow-up.

10.4.2. Non-randomized Experiment in Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care

Mainous, Lambourne, and Nietert (2013) conducted a prospective non-randomized trial to examine the impact of a cds system on antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections ( ari s) in primary care. The study is summarized below.

Setting – A primary care research network in the United States whose members use a common emr and pool data quarterly for quality improvement and research studies. Participants – An intervention group with nine practices across nine states, and a control group with 61 practices. Intervention – Point-of-care cds tool as customizable progress note templates based on existing emr features. cds recommendations reflect Centre for Disease Control and Prevention ( cdc ) guidelines based on a patient’s predominant presenting symptoms and age. cds was used to assist in ari diagnosis, prompt antibiotic use, record diagnosis and treatment decisions, and access printable patient and provider education resources from the cdc . Design – The intervention group received a multi-method intervention to facilitate provider cds adoption that included quarterly audit and feedback, best practice dissemination meetings, academic detailing site visits, performance review and cds training. The control group did not receive information on the intervention, the cds or education. Baseline data collection was for three months with follow-up of 15 months after cds implementation. Outcomes – The outcomes were frequency of inappropriate prescribing during an ari episode, broad-spectrum antibiotic use and diagnostic shift. Inappropriate prescribing was computed by dividing the number of ari episodes with diagnoses in the inappropriate category that had an antibiotic prescription by the total number of ari episodes with diagnosis for which antibiotics are inappropriate. Broad-spectrum antibiotic use was computed by all ari episodes with a broad-spectrum antibiotic prescription by the total number of ari episodes with an antibiotic prescription. Antibiotic drift was computed in two ways: dividing the number of ari episodes with diagnoses where antibiotics are appropriate by the total number of ari episodes with an antibiotic prescription; and dividing the number of ari episodes where antibiotics were inappropriate by the total number of ari episodes. Process measure included frequency of cds template use and whether the outcome measures differed by cds usage. Analysis – Outcomes were measured quarterly for each practice, weighted by the number of ari episodes during the quarter to assign greater weight to practices with greater numbers of relevant episodes and to periods with greater numbers of relevant episodes. Weighted means and 95% ci s were computed separately for adult and pediatric (less than 18 years of age) patients for each time period for both groups. Baseline means in outcome measures were compared between the two groups using weighted independent-sample t -tests. Linear mixed models were used to compare changes over the 18-month period. The models included time, intervention status, and were adjusted for practice characteristics such as specialty, size, region and baseline ari s. Random practice effects were included to account for clustering of repeated measures on practices over time. P -values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Findings – For adult patients, inappropriate prescribing in ari episodes declined more among the intervention group (-0.6%) than the control group (4.2%)( p = 0.03), and prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics declined by 16.6% in the intervention group versus an increase of 1.1% in the control group ( p < 0.0001). For pediatric patients, there was a similar decline of 19.7% in the intervention group versus an increase of 0.9% in the control group ( p < 0.0001). In summary, the cds had a modest effect in reducing inappropriate prescribing for adults, but had a substantial effect in reducing the prescribing of broad-spectrum antibiotics in adult and pediatric patients.

10.4.3. Interrupted Time Series on EHR Impact in Nursing Care

Dowding, Turley, and Garrido (2012) conducted a prospective its study to examine the impact of ehr implementation on nursing care processes and outcomes. The study is summarized below.

Setting – Kaiser Permanente ( kp ) as a large not-for-profit integrated healthcare organization in the United States. Participants – 29 kp hospitals in the northern and southern regions of California. Intervention – An integrated ehr system implemented at all hospitals with cpoe , nursing documentation and risk assessment tools. The nursing component for risk assessment documentation of pressure ulcers and falls was consistent across hospitals and developed by clinical nurses and informaticists by consensus. Design – its design with monthly data on pressure ulcers and quarterly data on fall rates and risk collected over seven years between 2003 and 2009. All data were collected at the unit level for each hospital. Outcomes – Process measures were the proportion of patients with a fall risk assessment done and the proportion with a hospital-acquired pressure ulcer ( hapu ) risk assessment done within 24 hours of admission. Outcome measures were fall and hapu rates as part of the unit-level nursing care process and nursing sensitive outcome data collected routinely for all California hospitals. Fall rate was defined as the number of unplanned descents to the floor per 1,000 patient days, and hapu rate was the percentage of patients with stages i-IV or unstageable ulcer on the day of data collection. Analysis – Fall and hapu risk data were synchronized using the month in which the ehr was implemented at each hospital as time zero and aggregated across hospitals for each time period. Multivariate regression analysis was used to examine the effect of time, region and ehr . Findings – The ehr was associated with significant increase in document rates for hapu risk (2.21; 95% CI 0.67 to 3.75) and non-significant increase for fall risk (0.36; -3.58 to 4.30). The ehr was associated with 13% decrease in hapu rates (-0.76; -1.37 to -0.16) but no change in fall rates (-0.091; -0.29 to 011). Hospital region was a significant predictor of variation for hapu (0.72; 0.30 to 1.14) and fall rates (0.57; 0.41 to 0.72). During the study period, hapu rates decreased significantly (-0.16; -0.20 to -0.13) but not fall rates (0.0052; -0.01 to 0.02). In summary, ehr implementation was associated with a reduction in the number of hapu s but not patient falls, and changes over time and hospital region also affected outcomes.

10.5. Summary

In this chapter we introduced randomized and non-randomized experimental designs as two types of comparative studies used in eHealth evaluation. Randomization is the highest quality design as it reduces bias, but it is not always feasible. The methodological issues addressed include choice of variables, sample size, sources of biases, confounders, and adherence to reporting guidelines. Three case examples were included to show how eHealth comparative studies are done.

- Baker T. B., Gustafson D. H., Shaw B., Hawkins R., Pingree S., Roberts L., Strecher V. Relevance of consort reporting criteria for research on eHealth interventions. Patient Education and Counselling. 2010; 81 (suppl. 7):77–86. [ PMC free article : PMC2993846 ] [ PubMed : 20843621 ]

- Columbia University. (n.d.). Statistics: sample size / power calculation. Biomath (Division of Biomathematics/Biostatistics), Department of Pediatrics. New York: Columbia University Medical Centre. Retrieved from http://www .biomath.info/power/index.htm .

- Boutron I., Moher D., Altman D. G., Schulz K. F., Ravaud P. consort Group. Extending the consort statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008; 148 (4):295–309. [ PubMed : 18283207 ]

- Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook. London: Author; (n.d.) Retrieved from http://handbook .cochrane.org/

- consort Group. (n.d.). The consort statement . Retrieved from http://www .consort-statement.org/

- Dowding D. W., Turley M., Garrido T. The impact of an electronic health record on nurse sensitive patient outcomes: an interrupted time series analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012; 19 (4):615–620. [ PMC free article : PMC3384108 ] [ PubMed : 22174327 ]

- Friedman C. P., Wyatt J.C. Evaluation methods in biomedical informatics. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, Inc; 2006.

- Guyatt G., Oxman A. D., Akl E. A., Kunz R., Vist G., Brozek J. et al. Schunemann H. J. grade guidelines: 1. Introduction – grade evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011; 64 (4):383–394. [ PubMed : 21195583 ]

- Harris A. D., McGregor J. C., Perencevich E. N., Furuno J. P., Zhu J., Peterson D. E., Finkelstein J. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2006; 13 (1):16–23. [ PMC free article : PMC1380192 ] [ PubMed : 16221933 ]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. London: 2011. (Version 5.1.0, updated March 2011) Retrieved from http://handbook .cochrane.org/

- Holbrook A., Pullenayegum E., Thabane L., Troyan S., Foster G., Keshavjee K. et al. Curnew G. Shared electronic vascular risk decision support in primary care. Computerization of medical practices for the enhancement of therapeutic effectiveness (compete III) randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011; 171 (19):1736–1744. [ PubMed : 22025430 ]

- Mainous III A. G., Lambourne C. A., Nietert P.J. Impact of a clinical decision support system on antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in primary care: quasi-experimental trial. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2013; 20 (2):317–324. [ PMC free article : PMC3638170 ] [ PubMed : 22759620 ]

- Noordzij M., Tripepi G., Dekker F. W., Zoccali C., Tanck M. W., Jager K.J. Sample size calculations: basic principles and common pitfalls. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010; 25 (5):1388–1393. Retrieved from http://ndt .oxfordjournals .org/content/early/2010/01/12/ndt .gfp732.short . [ PubMed : 20067907 ]

- Vervloet M., Linn A. J., van Weert J. C. M., de Bakker D. H., Bouvy M. L., van Dijk L. The effectiveness of interventions using electronic reminders to improve adherence to chronic medication: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012; 19 (5):696–704. [ PMC free article : PMC3422829 ] [ PubMed : 22534082 ]

- Zwarenstein M., Treweek S., Gagnier J. J., Altman D. G., Tunis S., Haynes B., Oxman A. D., Moher D. for the consort and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) groups. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the consort statement. British Medical Journal. 2008; 337 :a2390. [ PMC free article : PMC3266844 ] [ PubMed : 19001484 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zwarenstein M., Treweek S. What kind of randomized trials do we need? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009; 180 (10):998–1000. [ PMC free article : PMC2679816 ] [ PubMed : 19372438 ]

Appendix. Example of Sample Size Calculation

This is an example of sample size calculation for an rct that examines the effect of a cds system on reducing systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients. The case is adapted from the example described in the publication by Noordzij et al. (2010) .

(a) Systolic blood pressure as a continuous outcome measured in mmHg

Based on similar studies in the literature with similar patients, the systolic blood pressure values from the comparison groups are expected to be normally distributed with a standard deviation of 20 mmHg. The evaluator wishes to detect a clinically relevant difference of 15 mmHg in systolic blood pressure as an outcome between the intervention group with cds and the control group without cds . Assuming a significance level or alpha of 0.05 for 2-tailed t -test and power of 0.80, the corresponding multipliers 1 are 1.96 and 0.842, respectively. Using the sample size equation for continuous outcome below we can calculate the sample size needed for the above study.

n = 2[(a+b)2σ2]/(μ1-μ2)2 where

n = sample size for each group

μ1 = population mean of systolic blood pressures in intervention group

μ2 = population mean of systolic blood pressures in control group

μ1- μ2 = desired difference in mean systolic blood pressures between groups

σ = population variance

a = multiplier for significance level (or alpha)

b = multiplier for power (or 1-beta)

Providing the values in the equation would give the sample size (n) of 28 samples per group as the result

n = 2[(1.96+0.842)2(202)]/152 or 28 samples per group

(b) Systolic blood pressure as a categorical outcome measured as below or above 140 mmHg (i.e., hypertension yes/no)

In this example a systolic blood pressure from a sample that is above 140 mmHg is considered an event of the patient with hypertension. Based on published literature the proportion of patients in the general population with hypertension is 30%. The evaluator wishes to detect a clinically relevant difference of 10% in systolic blood pressure as an outcome between the intervention group with cds and the control group without cds . This means the expected proportion of patients with hypertension is 20% (p1 = 0.2) in the intervention group and 30% (p2 = 0.3) in the control group. Assuming a significance level or alpha of 0.05 for 2-tailed t -test and power of 0.80 the corresponding multipliers are 1.96 and 0.842, respectively. Using the sample size equation for categorical outcome below, we can calculate the sample size needed for the above study.

n = [(a+b)2(p1q1+p2q2)]/χ2

p1 = proportion of patients with hypertension in intervention group

q1 = proportion of patients without hypertension in intervention group (or 1-p1)

p2 = proportion of patients with hypertension in control group

q2 = proportion of patients without hypertension in control group (or 1-p2)

χ = desired difference in proportion of hypertensive patients between two groups

Providing the values in the equation would give the sample size (n) of 291 samples per group as the result

n = [(1.96+0.842)2((0.2)(0.8)+(0.3)(0.7))]/(0.1)2 or 291 samples per group

From Table 3 on p. 1392 of Noordzij et al. (2010).

This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0): see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

- Cite this Page Lau F, Holbrook A. Chapter 10 Methods for Comparative Studies. In: Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

- PDF version of this title (4.5M)

- Disable Glossary Links

In this Page

- Introduction

- Types of Comparative Studies

- Methodological Considerations

- Case Examples

- Example of Sample Size Calculation

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Chapter 10 Methods for Comparative Studies - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An ... Chapter 10 Methods for Comparative Studies - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

How to Do Comparative Analysis in Research ( Examples )

Comparative analysis is a method that is widely used in social science . It is a method of comparing two or more items with an idea of uncovering and discovering new ideas about them. It often compares and contrasts social structures and processes around the world to grasp general patterns. Comparative analysis tries to understand the study and explain every element of data that comparing.

We often compare and contrast in our daily life. So it is usual to compare and contrast the culture and human society. We often heard that ‘our culture is quite good than theirs’ or ‘their lifestyle is better than us’. In social science, the social scientist compares primitive, barbarian, civilized, and modern societies. They use this to understand and discover the evolutionary changes that happen to society and its people. It is not only used to understand the evolutionary processes but also to identify the differences, changes, and connections between societies.

Most social scientists are involved in comparative analysis. Macfarlane has thought that “On account of history, the examinations are typically on schedule, in that of other sociologies, transcendently in space. The historian always takes their society and compares it with the past society, and analyzes how far they differ from each other.