What is case study research?

Last updated

8 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Suppose a company receives a spike in the number of customer complaints, or medical experts discover an outbreak of illness affecting children but are not quite sure of the reason. In both cases, carrying out a case study could be the best way to get answers.

Organization

Case studies can be carried out across different disciplines, including education, medicine, sociology, and business.

Most case studies employ qualitative methods, but quantitative methods can also be used. Researchers can then describe, compare, evaluate, and identify patterns or cause-and-effect relationships between the various variables under study. They can then use this knowledge to decide what action to take.

Another thing to note is that case studies are generally singular in their focus. This means they narrow focus to a particular area, making them highly subjective. You cannot always generalize the results of a case study and apply them to a larger population. However, they are valuable tools to illustrate a principle or develop a thesis.

Analyze case study research

Dovetail streamlines case study research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What are the different types of case study designs?

Researchers can choose from a variety of case study designs. The design they choose is dependent on what questions they need to answer, the context of the research environment, how much data they already have, and what resources are available.

Here are the common types of case study design:

Explanatory

An explanatory case study is an initial explanation of the how or why that is behind something. This design is commonly used when studying a real-life phenomenon or event. Once the organization understands the reasons behind a phenomenon, it can then make changes to enhance or eliminate the variables causing it.

Here is an example: How is co-teaching implemented in elementary schools? The title for a case study of this subject could be “Case Study of the Implementation of Co-Teaching in Elementary Schools.”

Descriptive

An illustrative or descriptive case study helps researchers shed light on an unfamiliar object or subject after a period of time. The case study provides an in-depth review of the issue at hand and adds real-world examples in the area the researcher wants the audience to understand.

The researcher makes no inferences or causal statements about the object or subject under review. This type of design is often used to understand cultural shifts.

Here is an example: How did people cope with the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami? This case study could be titled "A Case Study of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and its Effect on the Indonesian Population."

Exploratory

Exploratory research is also called a pilot case study. It is usually the first step within a larger research project, often relying on questionnaires and surveys . Researchers use exploratory research to help narrow down their focus, define parameters, draft a specific research question , and/or identify variables in a larger study. This research design usually covers a wider area than others, and focuses on the ‘what’ and ‘who’ of a topic.

Here is an example: How do nutrition and socialization in early childhood affect learning in children? The title of the exploratory study may be “Case Study of the Effects of Nutrition and Socialization on Learning in Early Childhood.”

An intrinsic case study is specifically designed to look at a unique and special phenomenon. At the start of the study, the researcher defines the phenomenon and the uniqueness that differentiates it from others.

In this case, researchers do not attempt to generalize, compare, or challenge the existing assumptions. Instead, they explore the unique variables to enhance understanding. Here is an example: “Case Study of Volcanic Lightning.”

This design can also be identified as a cumulative case study. It uses information from past studies or observations of groups of people in certain settings as the foundation of the new study. Given that it takes multiple areas into account, it allows for greater generalization than a single case study.

The researchers also get an in-depth look at a particular subject from different viewpoints. Here is an example: “Case Study of how PTSD affected Vietnam and Gulf War Veterans Differently Due to Advances in Military Technology.”

Critical instance

A critical case study incorporates both explanatory and intrinsic study designs. It does not have predetermined purposes beyond an investigation of the said subject. It can be used for a deeper explanation of the cause-and-effect relationship. It can also be used to question a common assumption or myth.

The findings can then be used further to generalize whether they would also apply in a different environment. Here is an example: “What Effect Does Prolonged Use of Social Media Have on the Mind of American Youth?”

Instrumental

Instrumental research attempts to achieve goals beyond understanding the object at hand. Researchers explore a larger subject through different, separate studies and use the findings to understand its relationship to another subject. This type of design also provides insight into an issue or helps refine a theory.

For example, you may want to determine if violent behavior in children predisposes them to crime later in life. The focus is on the relationship between children and violent behavior, and why certain children do become violent. Here is an example: “Violence Breeds Violence: Childhood Exposure and Participation in Adult Crime.”

Evaluation case study design is employed to research the effects of a program, policy, or intervention, and assess its effectiveness and impact on future decision-making.

For example, you might want to see whether children learn times tables quicker through an educational game on their iPad versus a more teacher-led intervention. Here is an example: “An Investigation of the Impact of an iPad Multiplication Game for Primary School Children.”

- When do you use case studies?

Case studies are ideal when you want to gain a contextual, concrete, or in-depth understanding of a particular subject. It helps you understand the characteristics, implications, and meanings of the subject.

They are also an excellent choice for those writing a thesis or dissertation, as they help keep the project focused on a particular area when resources or time may be too limited to cover a wider one. You may have to conduct several case studies to explore different aspects of the subject in question and understand the problem.

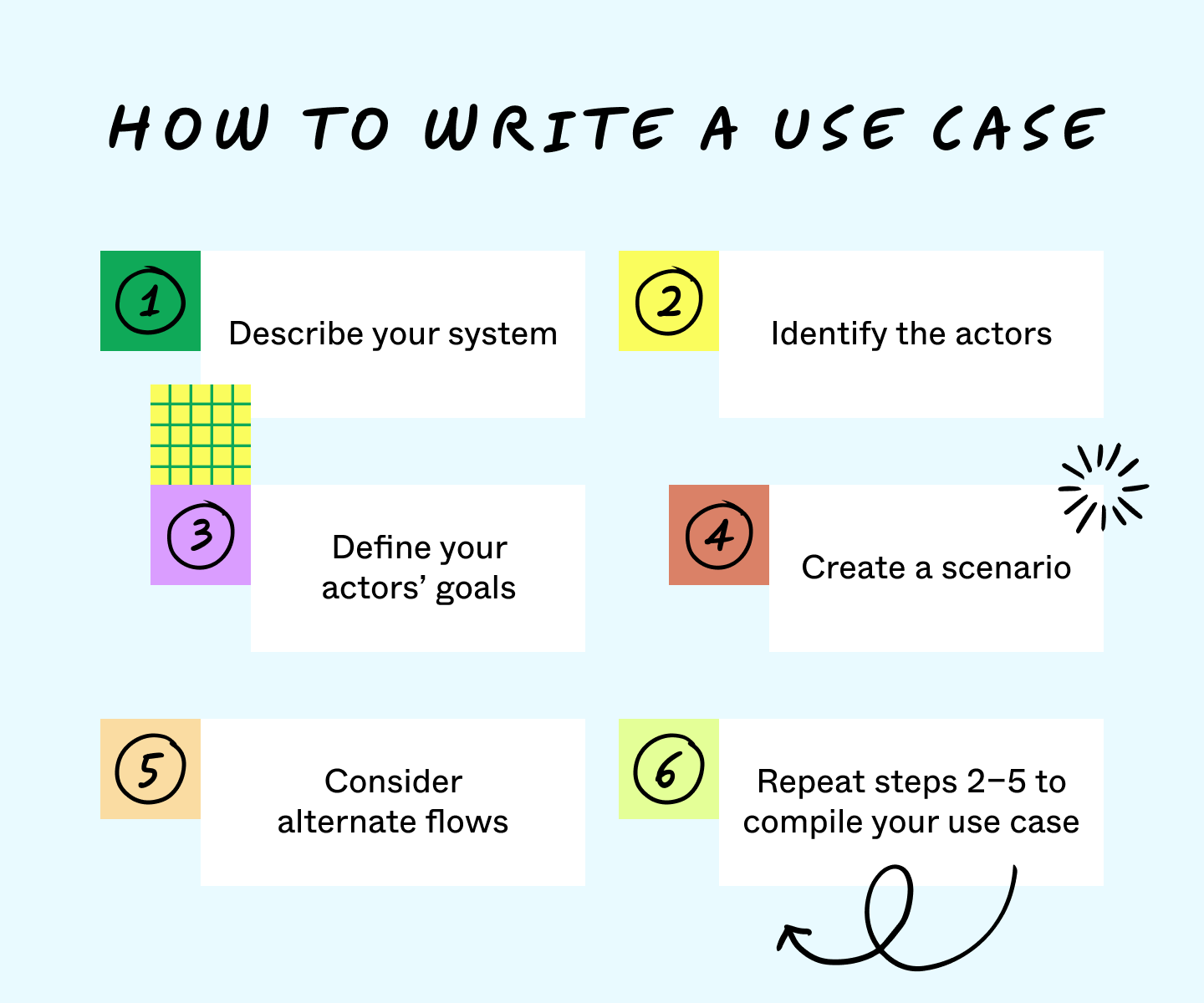

- What are the steps to follow when conducting a case study?

1. Select a case

Once you identify the problem at hand and come up with questions, identify the case you will focus on. The study can provide insights into the subject at hand, challenge existing assumptions, propose a course of action, and/or open up new areas for further research.

2. Create a theoretical framework

While you will be focusing on a specific detail, the case study design you choose should be linked to existing knowledge on the topic. This prevents it from becoming an isolated description and allows for enhancing the existing information.

It may expand the current theory by bringing up new ideas or concepts, challenge established assumptions, or exemplify a theory by exploring how it answers the problem at hand. A theoretical framework starts with a literature review of the sources relevant to the topic in focus. This helps in identifying key concepts to guide analysis and interpretation.

3. Collect the data

Case studies are frequently supplemented with qualitative data such as observations, interviews, and a review of both primary and secondary sources such as official records, news articles, and photographs. There may also be quantitative data —this data assists in understanding the case thoroughly.

4. Analyze your case

The results of the research depend on the research design. Most case studies are structured with chapters or topic headings for easy explanation and presentation. Others may be written as narratives to allow researchers to explore various angles of the topic and analyze its meanings and implications.

In all areas, always give a detailed contextual understanding of the case and connect it to the existing theory and literature before discussing how it fits into your problem area.

- What are some case study examples?

What are the best approaches for introducing our product into the Kenyan market?

How does the change in marketing strategy aid in increasing the sales volumes of product Y?

How can teachers enhance student participation in classrooms?

How does poverty affect literacy levels in children?

Case study topics

Case study of product marketing strategies in the Kenyan market

Case study of the effects of a marketing strategy change on product Y sales volumes

Case study of X school teachers that encourage active student participation in the classroom

Case study of the effects of poverty on literacy levels in children

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

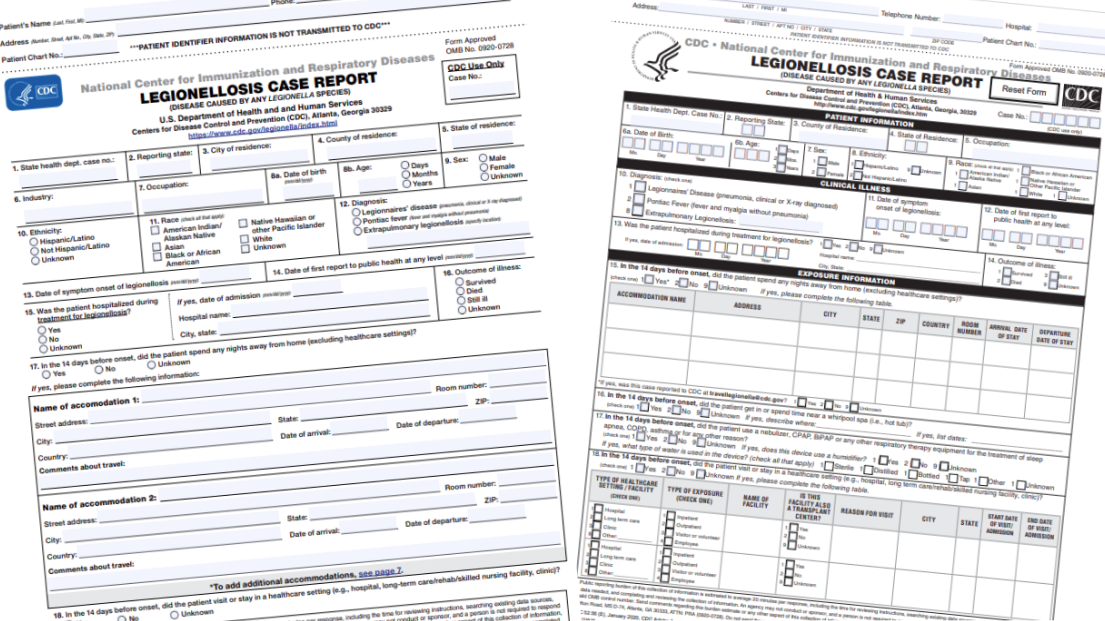

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Quantitative Research Questions

- Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

Writing a Case Study

What is a case study?

A Case study is:

- An in-depth research design that primarily uses a qualitative methodology but sometimes includes quantitative methodology.

- Used to examine an identifiable problem confirmed through research.

- Used to investigate an individual, group of people, organization, or event.

- Used to mostly answer "how" and "why" questions.

What are the different types of case studies?

Note: These are the primary case studies. As you continue to research and learn

about case studies you will begin to find a robust list of different types.

Who are your case study participants?

What is triangulation ?

Validity and credibility are an essential part of the case study. Therefore, the researcher should include triangulation to ensure trustworthiness while accurately reflecting what the researcher seeks to investigate.

How to write a Case Study?

When developing a case study, there are different ways you could present the information, but remember to include the five parts for your case study.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Next: Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 8:25 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchtools

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion