An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Glob Health

- v.4(Suppl 4); 2019

Early childhood development: an imperative for action and measurement at scale

Linda richter.

1 Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg-Braamfontein, South Africa

Maureen Black

2 RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA

3 Early Childhood Development, Unicef USA, New York City, New York, USA

Bernadette Daelmans

4 Department of Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland

Chris Desmond

5 DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Amanda Devercelli

6 Early Childhood Development, World Bank Group, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

7 Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland

Günther Fink

8 Household Economics and Health Systems, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland

9 Global Health and Population, Harvard University T H Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Jody Heymann

10 Fielding School of Public Health and WORLD Policy Analysis Center, University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Joan Lombardi

11 Early Opportunities, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

Chunling Lu

12 Division of Global Health, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Sara Naicker

Emily vargas-barón.

13 RISE Institute, Washington, District of Columbia, USA

Experiences during early childhood shape biological and psychological structures and functions in ways that affect health, well-being and productivity throughout the life course. The science of early childhood and its long-term consequences have generated political momentum to improve early childhood development and elevated action to country, regional and global levels. These advances have made it urgent that a framework, measurement tools and indicators to monitor progress globally and in countries are developed and sustained. We review progress in three areas of measurement contributing to these goals: the development of an index to allow country comparisons of young children’s development that can easily be incorporated into ongoing national surveys; improvements in population-level assessments of young children at risk of poor early development; and the production of country profiles of determinants, drivers and coverage for early childhood development and services using currently available data in 91 countries. While advances in these three areas are encouraging, more investment is needed to standardise measurement tools, regularly collect country data at the population level, and improve country capacity to collect, interpret and use data relevant to monitoring progress in early childhood development.

Summary box

- New knowledge of the extent to which experiences during early childhood shape health, well-being and productivity throughout the life course has prompted action to improve early childhood development at the country, regional and global levels.

- Advances have been made in three areas of measurement needed to achieve these goals: population-level child assessments, population proxies of children at risk of poor childhood development, and country and regional profiles of drivers and supports for early childhood development.

- Regular, country-comparable, population-level measurements of childhood development, as well as threats to development and available supports and services, are needed to drive progress and accountability in efforts to improve early childhood development.

Introduction

Scientific findings from diverse disciplines are in agreement that critical elements of lifelong health, well-being and productivity are shaped during the first 2–3 years of life, 1 beginning with parental health and well-being. 2 The experiences and exposures of young children during this time-bound period of neuroplasticity shape the development of both biological and psychological structures and functions across the life course.

Adversities during pregnancy and early childhood, due to undernutrition, stress, poverty, violence, chronic illnesses and exposure to toxins, among others, can disrupt brain development, with consequences that endure throughout life and into future generations. 3 4 Children whose early development is compromised have fewer personal and social skills and less capacity to benefit from schooling. These deficits limit their work opportunities and earnings as adults. 5 A corollary of early susceptibility to adversity includes responsiveness to opportunities during these early years. As a result, interventions during the first 3 years of life are more effective and less costly than later efforts to compensate for early adversities and to promote human development. 6

It is estimated that, in 2010, at least 249 million (43%) children under the age of 5 years in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) were at risk of poor early childhood development (ECD) as a consequence of being stunted or living in extreme poverty. 7 This loss of potential is costly for individuals and societies. The average percentage loss of adult income per year is estimated at 26%, increasing the likelihood of persistent poverty for these children, families and societies. 5 Assuming 125 million children are born each year with a global average of poor infant growth, 8 the estimated annual global income loss is US$177 billion. 9 These impacts have serious consequences on economic growth. Recent World Bank estimates suggest that the average country’s per capital gross domestic product would be 7% higher than it is now had stunting been eliminated when today’s workers were children. 10 At the global level, human capital accounts for as much as two-thirds of the wealth differences between countries. ECD is the foundation of human capital. 11

Supported by a growing body of evidence and increasing global interest in this field, ECD is included in the 2015 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Target 4.2 is ‘improved access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education’. Progress towards achieving this target is measured by indicator 4.2.1, ‘the proportion of children under 5 years of age who are developmentally on track in health, learning and psychosocial well-being, by sex’. ECD is closely linked to other SDGs as well, for example, eradicate poverty (1), end hunger and improve nutrition (2), ensure healthy lives (3), achieve gender equality (5), reduce inequality in and among countries (10), and promote peaceful societies (16), and it is implied in several more. 5

The United Nations Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, 2016–2030 synthesises the 17 SDGs in three strategies: survive, thrive and transform. Survive refers to sustained and increased reductions in preventable deaths of women, newborns, children and adolescents, as well as stillbirths; thrive refers to children receiving the nurturing care necessary to reach their developmental potential; and transform refers to comprehensive changes in policies, programmes and services for women, children and adolescents to achieve their potential. 12

ECD has also become an important component of other global agendas, including Scaling Up Nutrition, the Global Partnership for Education, the Global Financing Facility for Every Woman Every Child, the Every Woman Every Child movement, the work plans of the WHO, Unicef and the World Bank Group, the G20, 13 international funding agencies, and philanthropic foundations. 7

These multifaceted findings have generated political momentum to improve ECD as a critical phase in the life course, making it urgent to develop measurement tools and indicators to monitor progress globally and in countries. Advances in measurement are needed to support efforts to motivate and track political and financial commitments, and to monitor implementation and impact. This means that we must be able to determine how many and which children are thriving, and on track in health, learning and psychosocial well-being.

Measurement of children’s progress in childhood is acknowledged to be challenging because development is by nature dynamic and children have varying individual trajectories. Well-validated instruments of individual development are complex and require extensive training and expertise. These challenges are amplified in efforts to make measurements across populations of children. Taking these limitations into account, we review progress in three areas of measurement that are contributing data to the current political momentum for ECD and efforts to monitor implementation and impact. Progress is being made to construct a feasible country-comparable measure of young children’s development that could be incorporated into national surveys, to improve proxies of population levels of young children at risk of poor early development, and to generate country profiles of determinants, drivers and coverage for early childhood development and services, using currently available data.

A new initiative to construct a population measure of ECD

A direct measure of the development of children 0–5 years that could be administered globally and used both within and across countries is urgently needed. Efforts have been made since the 1980s to develop a globally applicable measure of ECD, with the major challenges being individual and cultural variations in the onset of early skills. 14

Currently, the Early Child Development Index (ECDI) is included as the indicator of SDG goal 4, target 4.2. It is a composite index, first introduced in Unicef’s fourth Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) in 2010. It is derived from 10 caregiver-reported questions designed for children aged 36–59 months to assess four domains of development: literacy-numeracy, learning/cognition, physical development and socioemotional development. Some items are acknowledged to be unsuitable for assessing development, 15 and efforts are under way to revise the index, as well as to include items applicable to children younger than 3 years of age.

Three research efforts have collaborated to create the Global Scale for Early Development (GSED): the Infant and Young Child Development from the WHO, 16 the Caregiver-Reported Early Development Instrument from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, 17 and the Developmental Score from the Global Child Development Group at the University of the West Indies. 18 The goals of the GSED are to develop two instruments for measuring ECD (0–3 years) globally: a population-based instrument and a programme evaluation instrument, as described in table 1 .

Global Scale for Early Development: population and programme measures

The GSED takes advantage of large-scale and cohort studies from many countries and is harmonising efforts to generate population-based and programmatic evaluation measures of the development of children aged 0–3 years old that can be used globally ( table 2 ). The scale will be available for country testing in 2019. The aim is to have the population-based measure incorporated into national surveys, including Unicef’s MICS and the US Agency for International Development’s Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), to produce globally comparable monitoring data. Efforts are also under way to harmonise the revision of ECDI and the development of GSED to align on child outcome measurement from birth to 59 months of age.

Development and validation of the Global Scale for Early Development

CREDI, Caregiver-Reported Early Development Instrument; D-score, Developmental Score; IYCD, Infant and Young Child Development.

A country-comparable proxy for population levels of risk of poor childhood development

Information about children’s risk for poor development is important, as is identifying areas for intervention. To track these, a proxy measure of population levels of young children at risk of suboptimal development has been calculated.

Stunting and poverty were used in the first published estimation in 2007 of the global prevalence of risk to children’s development. The initial choice of indicators was based on evidence that they both predict poor cognitive development and school performance. 19 20 Additional advantages are that their definitions are standardised and many countries have data on both indicators. 21

Lu et al 21 updated the earlier values to 2010, using the 2006 WHO growth standards and World Bank poverty rates (US$1.25 per person per day), leading to an estimate of 249 million children or 43% of all children under 5 years of age in LMICs being at risk of poor childhood development. The accuracy and comparability of the later estimates benefited greatly from major advances in both data availability and estimation methods. 21

To estimate the long-term consequences of poor ECD, studies focus on estimating the impact on subsequent schooling and labour market participation and wages. The current estimate, that the average percentage of annual adult income lost as a result of stunting and extreme poverty in early childhood is about 26%, is supported by follow-up adult data from early life interventions. Two programmes have found wage increases between 25% in Jamaica attributed to a psychosocial intervention 22 and 46% in Guatemala attributed to a protein supplement. 23

In order to improve the estimate of risk, efforts are under way to include additional risks experienced in ECD known to affect health and well-being across the life course. For example, adding low maternal schooling and exposure to harsh punishment to stunting and extreme poverty, for 15 countries with available data from MICS in 2010/2011, increased the number of children estimated to be at risk of poor childhood development substantially. 5

Country profiles of ECD

Population-based measures of early child development and proxies of children at risk give an indication of prevalence, and indicators of disparity can be derived according to gender, urban–rural location and socioeconomic status. However, they do not include drivers, determinants nor coverage of interventions that could improve childhood development.

The Countdown to 2015 for Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival , established in 2005, set a precedent by creating mechanisms to portray multidimensional aspects of progress towards improving maternal and child health, and is testimony of its value. 24 Countdown to 2030 , which tracks maternal, child and adolescent health and nutrition goals, has expanded to address the broader SDG agenda, including ECD, health in humanitarian settings and conflict, and adolescent health and well-being. 25 26 It includes coverage and equity of essential interventions, as well as indicators of determinants and the enabling environment provided by policies.

This approach has been applied to ECD using the Nurturing Care Framework, 27 launched at the 71st World Health Assembly. The concept of nurturing care was introduced in the 2017 Lancet Series Advancing Early Child Development: From Science to Scale . Nurturing Care Framework comprises conditions for early development: good health and nutrition; protection from environmental and personal harm; affectionate and encouraging responses to young children’s communications; and opportunities for young children to learn through exploration and interpersonal interactions. 7

These early experiences are nested in caregiver–child and family relationships. In turn, parents, families and other caregivers require support from a facilitating environment of policies, services and communities. Policies, services and programmes can protect women’s health and well-being, safeguard pregnancy and birth, and enable families and caregivers to promote and protect young children’s development. 6

The Nurturing Care Framework has been used to produce ECD profiles for 91 LMICs. 28 Countries were selected either to ensure alignment of ECD with Countdown to 2030 , or because more than 30% of children are estimated to be at risk of poor ECD in 2010, using the methods described in Lu et al 21 and Black et al . 7

These country profiles, which consist of currently available data from LMICs, are laid out to represent the Nurturing Care Framework. The profiles consist of the following sections:

- Selected demographic indicators of the country relevant to early child development: total population, annual births, children under 5 years of age and under-5 mortality.

- Threats to ECD, including maternal mortality, young motherhood, low birth weight, preterm births, child poverty, under-5 stunting, harsh punishment and inadequate supervision.

- The prevalence of young children at risk of poor child development disaggregated by gender and rural–urban residence, and lifetime costs of growth deficit in early childhood in US dollars.

- The facilitating policy environment for caregivers and children, as indexed by relevant conventions and national policies.

- Support and services to promote ECD in the five areas of nurturing care: early learning, health, nutrition, responsive caregiving, and security and safety.

Most of the existing data are published in Unicef’s annual State of the World’s Children. Convention and policy data come from, among others, the United Nations Treaty Collections and the International Labour Organization.

Figure 1 shows an example of the country profiles, with the country name replace by ‘Country Profiles’.

An example of an early childhood development (ECD) country profile. CRC, convention on the rights of the child.

In a forthcoming paper, Lu and Richter (2019) describe in detail the updated estimates of children at risk of poor childhood development using the newly released poverty line of US$1.9 per person per day to estimate that, in 2015, 233 million children or 40.5% of children under 5 years of age were at risk of poor childhood development. Figures 2 and 3 show the estimates of risk for poor ECD across a decade, from 2005 to 2010 and 2015, and using the 2010 data variations between children at risk living in rural and urban areas. Gender is not illustrated here because, in most countries, the differences are small and not statistically significant.

Decline in the number of countries with high proportions of young children at risk of poor development between 2005 and 2015.

Differences in risk of poor development among urban and rural children in 63 countries (most recent years with available data).

Figure 2 shows that, between 2005 and 2010, countries with two-thirds of young children at risk (>67%) declined in both central Europe and South-East Asia. There was little change in countries with high proportions of young children at risk in sub-Saharan Africa during this period, and by 2015 countries with the highest proportion of children at risk were in Central and Southern Africa.

Estimates on the prevalence of children at risk of poor development in urban and rural areas were derived using DHS, MICS and country data for 63 countries with available data in most recent years ( figure 3 ). The differences are strikingly high, with more rural children at risk than their urban counterparts in 50 countries (differences of more than 20%). Almost all countries with 40% point differences were in sub-Saharan Africa. 28

There are additional indicators that ideally should be included in a monitoring framework, but currently lack comparable country data. Data are usually unavailable because reliable, valid instruments feasible for multicountry administration are still in development, or the instruments are not yet included in representative surveys. In particular, there are as yet no global population-based indicators for assessing responsive caregiving. Suggestions have been made that data should be collected on whether information about ECD and caregiver–child interaction is publicly disseminated, whether home visits or groups are provided for parents at high risk of experiencing difficulties providing their children with nurturing care, and whether affordable good quality child day care is available for families who need it. 29 National data on laws and policies that support responsive caregiving are also insufficient, for example, wages and other forms of income to enable families to provide for their young children. 30

Additional data gaps concern risks arising from poor parental mental health, 31 low maternal schooling, and maternal tobacco and alcohol use, among others, prevalence of childhood developmental delays and disabilities, 32 and maltreatment and institutionalisation of young children. 33 There is also no comparable information on government budget allocation to ECD or household expenditure on ECD services care, among others.

Multidisciplinary scientific evidence and political momentum are focusing on ECD as a critical phase in enhancing health and well-being across the life course. Additional measurements and indicators for monitoring and evaluation are urgently needed to support expansions in implementation and investment, and to report progress. New data will stimulate global, regional and national action, and in turn motivate for more areas of ECD to be covered in national surveys.

The Nurturing Care Framework provides a platform for three important areas of work. First, very significant progress is being made through the revision of the ECDI and the development of the GSED, a short caregiver-reported population measure of ECD that could feasibly be included in DHS, MICS and other nationally representative household surveys. The GSED will enable ECD to be tracked at population levels, and for programmes and services to be monitored and evaluated in comparable ways.

Second, a country-comparable proxy of the risk of poor ECD developed from 2004 data and updated with 2010 data has been extended to 2015, enabling comparisons to be made globally, regionally and by country across the last decade. Plans are in place to update these estimates regularly, and to add new risks as data for more countries become available.

Third, using these estimates, data included in Countdown to 2030 , and additional data from MICS and policy databases, initial profiles have been constructed for 91 LMICs. The profiles are organised according to the ecological model of the Nurturing Care Framework with policies, services and programmes supporting families and caregivers to provide good health and nutrition, security and safety, opportunities for early learning, and responsive caregiving for young children to thrive. The further development of these profiles is overseen by a multiagency committee as part of Countdown to 2030 and are freely available ( http://www.ecdan.org/countries.html and https://nurturing-care.org/?page_id=703 ). Unicef will update the country data annually and the profiles will be reproduced every 2 years.

However, as indicated earlier, substantial gaps in national and global data on topics of concern to ECD remain. The current global estimation on burden of risks, for example, does not include known risk factors other than stunting and extreme poverty, as a result of which the existing burden calculation is considerably underestimated. 5 The limited information on ECD investments at the country and global levels is exacerbated by the lack of appreciation of what constitute essential and continuous services, standard indicators for measuring ECD interventions and policies, as well as systematically collected data. Country capacity needs to be strengthened and ECD costing modules integrated into existing household income or expenditure surveys, and routinely collected from specific types of programmes. Clear definitions are needed to track donor contributions to ECD, and efforts should be made to address data issues, including collecting data from emerging donor countries (eg, China), foundations and international non-governmental organisations that are playing an increasing role in financing ECD, as has been called for by the G20. 33 National policies, strategic plans and laws which support ECD through nurturing care should be tracked for this intersectoral area.

To improve measurements of risks, intervention coverage, policies, financial commitments and impact on young children’s development, more investment is needed to regularly collect and disseminate data at the national and subnational levels. Analytical gaps at the country and global levels exist, especially with respect to equity analyses by household wealth, maternal education and rural–urban location, as well as by gender and child age within 0–5 years.

In conclusion, progress has been extremely positive, but too slow and too fragmented for the bold global agenda of ECD and the Nurturing Care Framework. The alliance with Countdown to 2030 is helpful as there is much to be learnt from the initiative’s experience under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), as well as collaboration with the SDGs. The country profiles boldly portray what we currently know about ECD in some of the most at-risk conditions and will prove a valuable tool for advocacy and implementation, including to improve measurement. Successful implementation and impact are dependent on accountability supported by regularly updated reliable and valid information.

Acknowledgments

Robert Inglis (Jive Media Africa, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa) and Frank Sokolic (EduAction, Durban, South Africa) for assistance with the country profiles and maps.

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: All authors meet the conditions for authorship: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study has been funded by Conrad N Hilton Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data on the country profiles are publicly available on the websites cited in the paper.

InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

This brief is part of a series that summarizes essential scientific findings from Center publications.

Content in This Guide

Step 1: why is early childhood important.

- : Brain Hero

- : The Science of ECD (Video)

- You Are Here: The Science of ECD (Text)

Step 2: How Does Early Child Development Happen?

- : 3 Core Concepts in Early Development

- : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development

- : InBrief: The Science of Resilience

Step 3: What Can We Do to Support Child Development?

- : From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

- : 3 Principles to Improve Outcomes

The science of early brain development can inform investments in early childhood. These basic concepts, established over decades of neuroscience and behavioral research, help illustrate why child development—particularly from birth to five years—is a foundation for a prosperous and sustainable society.

Brains are built over time, from the bottom up.

The basic architecture of the brain is constructed through an ongoing process that begins before birth and continues into adulthood. Early experiences affect the quality of that architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for all of the learning, health and behavior that follow. In the first few years of life, more than 1 million new neural connections are formed every second . After this period of rapid proliferation, connections are reduced through a process called pruning, so that brain circuits become more efficient. Sensory pathways like those for basic vision and hearing are the first to develop, followed by early language skills and higher cognitive functions. Connections proliferate and prune in a prescribed order, with later, more complex brain circuits built upon earlier, simpler circuits.

The interactive influences of genes and experience shape the developing brain.

Scientists now know a major ingredient in this developmental process is the “ serve and return ” relationship between children and their parents and other caregivers in the family or community. Young children naturally reach out for interaction through babbling, facial expressions, and gestures, and adults respond with the same kind of vocalizing and gesturing back at them. In the absence of such responses—or if the responses are unreliable or inappropriate—the brain’s architecture does not form as expected, which can lead to disparities in learning and behavior.

The brain’s capacity for change decreases with age.

The brain is most flexible, or “plastic,” early in life to accommodate a wide range of environments and interactions, but as the maturing brain becomes more specialized to assume more complex functions, it is less capable of reorganizing and adapting to new or unexpected challenges. For example, by the first year, the parts of the brain that differentiate sound are becoming specialized to the language the baby has been exposed to; at the same time, the brain is already starting to lose the ability to recognize different sounds found in other languages. Although the “windows” for language learning and other skills remain open, these brain circuits become increasingly difficult to alter over time. Early plasticity means it’s easier and more effective to influence a baby’s developing brain architecture than to rewire parts of its circuitry in the adult years.

Cognitive, emotional, and social capacities are inextricably intertwined throughout the life course.

The brain is a highly interrelated organ, and its multiple functions operate in a richly coordinated fashion. Emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they are the bricks and mortar that comprise the foundation of human development. The emotional and physical health, social skills, and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important prerequisites for success in school and later in the workplace and community.

Toxic stress damages developing brain architecture, which can lead to lifelong problems in learning, behavior, and physical and mental health.

Scientists now know that chronic, unrelenting stress in early childhood, caused by extreme poverty, repeated abuse, or severe maternal depression, for example, can be toxic to the developing brain. While positive stress (moderate, short-lived physiological responses to uncomfortable experiences) is an important and necessary aspect of healthy development, toxic stress is the strong, unrelieved activation of the body’s stress management system. In the absence of the buffering protection of adult support, toxic stress becomes built into the body by processes that shape the architecture of the developing brain.

Policy Implications

- The basic principles of neuroscience indicate that early preventive intervention will be more efficient and produce more favorable outcomes than remediation later in life.

- A balanced approach to emotional, social, cognitive, and language development will best prepare all children for success in school and later in the workplace and community.

- Supportive relationships and positive learning experiences begin at home but can also be provided through a range of services with proven effectiveness factors. Babies’ brains require stable, caring, interactive relationships with adults — any way or any place they can be provided will benefit healthy brain development.

- Science clearly demonstrates that, in situations where toxic stress is likely, intervening as early as possible is critical to achieving the best outcomes. For children experiencing toxic stress, specialized early interventions are needed to target the cause of the stress and protect the child from its consequences.

Suggested citation: Center on the Developing Child (2007). The Science of Early Childhood Development (InBrief). Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu .

Related Topics: toxic stress , brain architecture , serve and return

Explore related resources.

- Reports & Working Papers

- Tools & Guides

- Presentations

- Infographics

Videos : Serve & Return Interaction Shapes Brain Circuitry

Reports & Working Papers : From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

Briefs : InBrief: The Science of Neglect

Videos : InBrief: The Science of Neglect

Reports & Working Papers : The Science of Neglect: The Persistent Absence of Responsive Care Disrupts the Developing Brain

Reports & Working Papers : Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships

Tools & Guides , Briefs : 5 Steps for Brain-Building Serve and Return

Briefs : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development

Partner Resources : Building Babies’ Brains Through Play: Mini Parenting Master Class

Podcasts : About The Brain Architects Podcast

Videos : FIND: Using Science to Coach Caregivers

Videos : How-to: 5 Steps for Brain-Building Serve and Return

Briefs : How to Support Children (and Yourself) During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Videos : InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : MOOC: The Best Start in Life: Early Childhood Development for Sustainable Development

Presentations : Parenting for Brain Development and Prosperity

Videos : Play in Early Childhood: The Role of Play in Any Setting

Videos : Child Development Core Story

Videos : Science X Design: Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children

Podcasts : The Brain Architects Podcast: COVID-19 Special Edition: Self-Care Isn’t Selfish

Podcasts : The Brain Architects Podcast: Serve and Return: Supporting the Foundation

Videos : Three Core Concepts in Early Development

Reports & Working Papers : Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : Training Module: “Talk With Me Baby”

Infographics : What Is COVID-19? And How Does It Relate to Child Development?

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : Vroom

Digital parenting and its impact on early childhood development: A scoping review

- Published: 07 May 2024

Cite this article

- Yun Nga Choy 1 ,

- Eva Yi Hung Lau 1 &

- Dandan Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1855-3570 1

110 Accesses

Explore all metrics

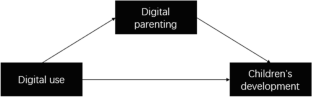

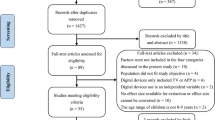

Digital parenting refers to the parenting practices that maximize the benefits and minimize potential risks of children’s interactions with digital media and online spaces. Balancing the pros and cons of early digital usage is a challenge for many caregivers. This scoping review synthesizes evidence regarding digital parenting practices and their impact on children's digital use and development, drawing from 40 studies published in international peer-reviewed journals between 2010 and 2023. Four themes have emerged from this scoping review. Firstly, parental perspectives on early digital use diverged into positive views (as ‘educational aids’), negative views (as ‘distractions’), and cultural differences. Secondly, children's digital use was influenced by digital parenting practices, specifically parental modeling, parenting style, parental mediation and the intended purpose of children's digital use. Thirdly, a correlation was noted between varying results of digital parenting and children's digital use, with outcomes manifested in children's digital literacy, parent–child relationships, social-emotional and language development, behavioral issues, and emergent literacy. Fourthly, influential factors were child ages, parental and family-related factors (including gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, family structure, religion, and parents' digital literacy), and the type of digital resources. The review suggests that future research should concentrate on training programs to enhance parental digital literacy skills and employ monitoring tools to better assess children's digital use.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Universal Digital Programs for Promoting Mental and Relational Health for Parents of Young Children: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis

Parental risk factors and moderators of prolonged digital use in preschoolers: A meta-analysis

A mixed method research on increasing digital parenting awareness of parents

Data availability.

The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Anandari, D. R. (2016, February). Permissive parenting style and its risks to trigger online game addiction among children. In Asian Conference 2nd Psychology & Humanity (pp. 773-781).

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8 (1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Article Google Scholar

Bedford, R., Saez de Urabain, I. R., Cheung, C. H., Karmiloff-Smith, A., & Smith, T. J. (2016). Toddlers’ fine motor milestone achievement is associated with early touchscreen scrolling. Frontiers in Psychology, 7 , 1108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01108

Benedetto, L., & Ingrassia, M. (Eds.). (2021). Parenting: Studies by an Ecocultural and Transactional Perspective . BoD–Books on Demand.

Google Scholar

Beyens, I., & Beullens, K. (2017). Parent-child conflict about children’s tablet use: The role of parental mediation. New Media & Society, 19 (12), 2075–2093. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816655099

Buabbas, A., Hasan, H., & Shehab, A. A. (2021). Parents’ attitudes toward school students’ overuse of smartphones and its detrimental health impacts: Qualitative study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 4 (2), e24196. https://doi.org/10.2196/24196

Cao, S., Dong, C., & Li, H. (2021). Digital parenting during the COVID-19 lockdowns: how Chinese parents viewed and mediated young children's digital use. Early Child Development and Care , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2021.2016732

Cao, S., & Li, H. (2023). A Scoping Review of Digital Well-Being in Early Childhood: Definitions, Measurements, Contributors, and Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20 (4), 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043510

Chia, M. Y. H., Komar, J., Chua, T. B. K., & Tay, L. Y. (2022). Associations between Parent Attitudes and on-and off-Screen Behaviours of Preschool Children in Singapore. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19 (18), 11508. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811508

Chou, H. L., Chou, C., & Chen, C. H. (2016). The moderating effects of parenting styles on the relation between the internet attitudes and internet behaviors of high-school students in Taiwan. Computers & Education, 94 , 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.017

Clark, L. S. (2011). Parental mediation theory for the digital age. Communication Theory, 21 (4), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01391.x

Collier, K. M., Coyne, S. M., Rasmussen, E. E., Hawkins, A. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Erickson, S. E., & Memmott-Elison, M. K. (2016). Does parental mediation of media influence child outcomes? A meta-analysis on media time, aggression, substance use, and sexual behavior. Developmental Psychology, 52 (5), 798. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000108

Dardanou, M., Unstad, T., Brito, R., Dias, P., Fotakopoulou, O., Sakata, Y., & O’Connor, J. (2020). Use of touchscreen technology by 0–3-year-old children: Parents’ practices and perspectives in Norway, Portugal and Japan. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 20 (3), 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798420938445

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (2017). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Interpersonal development (pp. 161–170). London: Routledge.

Dias, P., Brito, R., Ribbens, W., Daniela, L., Rubene, Z., Dreier, M., … & Chaudron, S. (2016). The role of parents in the engagement of young children with digital technologies: Exploring tensions between rights of access and protection, from 'Gatekeepers' to 'Scaffolders'. Global Studies of Childhood , 6 (4), 414–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610616676024

Dong, C., & Mertala, P. (2021). Preservice teachers’ beliefs about young children’s technology use at home. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102 , 103325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103325

Dong, C., Cao, S., & Li, H. (2020). Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Children and Youth Services Review, 118 , 105440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440

Dong, C., Cao, S., & Li, H. (2021). Profiles and predictors of young children's digital literacy and multimodal practices in central China. Early Education and Development , 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.1930937

Eichen, L., Hackl‐Wimmer, S., Eglmaier, M. T. W., Lackner, H. K., Paechter, M., Rettenbacher, K., … & Walter‐Laager, C. (2021). Families' digital media use: Intentions, rules and activities. British Journal of Educational Technology , 52 (6), 2162–2177. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13161

Fan, M., Antle, A. N., & Lu, Z. (2022). The Use of Short-Video Mobile Apps in Early Childhood: a Case Study of Parental Perspectives in China. Early Years , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2022.2038088

Fidan, A., & Seferoğlu, S. S. (2020). Online environments and digital parenting: an investigation of approaches, problems, and recommended solutions. Bartin Üniversitesi Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 9 (2), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.14686/buefad.664141

Fitzpatrick, C., Almeida, M. L., Harvey, E., Garon-Carrier, G., Berrigan, F., & Asbridge, M. (2022). An examination of bedtime media and excessive screen time by Canadian preschoolers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pediatrics, 22 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03280-8

Gjelaj, M., Buza, K., Shatri, K., & Zabeli, N. (2020). Digital Technologies in Early Childhood: Attitudes and Practices of Parents and Teachers in Kosovo. International Journal of Instruction, 13 (1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2020.13111a

Gou, H., & Perceval, G. (2023). Does digital media use increase risk of social-emotional delay for Chinese preschoolers? Journal of Children and Media, 17 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2022.2118141

Griffith, S. F. (2023). Parent beliefs and child media use: Stress and digital skills as moderators. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 86 , 101535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2023.101535

Herodotou, C. (2018). Young children and tablets: A systematic review of effects on learning and development. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12220

Huber, B., Highfield, K., & Kaufman, J. (2018). Detailing the digital experience: Parent reports of children’s media use in the home learning environment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49 (5), 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12667

Hutton, J. S., Dudley, J., Horowitz-Kraus, T., DeWitt, T., & Holland, S. K. (2020). Associations between screen-based media use and brain white matter integrity in preschool-aged children. JAMA Pediatrics, 174 (1), e193869–e193869. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3869

Iqbal, M. K., Iqbal, M. B., Rasheed, I., & Sandhu, A. (2012, October). 4G Evolution and Multiplexing Techniques with solution to implementation challenges. In 2012 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (pp. 485–488). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/CyberC.2012.88

Isikoglu Erdogan, N., Johnson, J. E., Dong, P. I., & Qiu, Z. (2019). Do parents prefer digital play? Examination of parental preferences and beliefs in four nations. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47 (2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-018-0901-2

Işıkoğlu, N., Erol, A., Atan, A., & Aytekin, S. (2021). A qualitative case study about overuse of digital play at home. Current Psychology , 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01442-y

Istenič, A., Rosanda, V., & Gačnik, M. (2023). Surveying Parents of Preschool Children about Digital and Analogue Play and Parent-Child Interaction. Children, 10 (2), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020251

Jago, R., Thompson, J. L., Sebire, S. J., Wood, L., Pool, L., Zahra, J., & Lawlor, D. A. (2014). Cross-sectional associations between the screen-time of parents and young children: Differences by parent and child gender and day of the week. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-11-54

Kaye, L. (Ed.). (2016). Young children in a digital age: Supporting learning and development with technology in early years . Routledge.

Keya, F. D., Rahman, M. M., Nur, M. T., & Pasa, M. K. (2020). Parenting and child’s (five years to eighteen years) digital game addiction: A qualitative study in North-Western part of Bangladesh. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 2 , 100031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100031

Konca, A. S. (2021). Digital technology usage of young children: Screen time and families. Early Childhood Education Journal , 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01245-7

Konok, V., & Szőke, R. (2022). Longitudinal Associations of Children’s Hyperactivity/Inattention, Peer Relationship Problems and Mobile Device Use. Sustainability, 14 (14), 8845. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148845

Konok, V., Bunford, N., & Miklósi, Á. (2020). Associations between child mobile use and digital parenting style in Hungarian families. Journal of Children and Media, 14 (1), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2019.1684332

Kulakci-Altintas, H. (2019). Technological device use among 0–3 year old children and attitudes and behaviors of their parents towards technological devices. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29 (1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01457-x

Lam, L. T. (2015). Parental mental health and Internet Addiction in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 42 , 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.033

Lau, E. Y. H., & Lee, K. (2021). Parents’ views on young children’s distance learning and screen time during COVID-19 class suspension in Hong Kong. Early Education and Development, 32 (6), 863–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1843925

Lauricella, A. R., Wartella, E., & Rideout, V. J. (2015). Young children’s screen time: The complex role of parent and child factors. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36 , 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.12.001

Lei, H., Chiu, M. M., Cui, Y., Zhou, W., & Li, S. (2018). Parenting style and aggression: A meta-analysis of mainland Chinese children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 94 , 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.033

Lepicnik-Vodopivec, J., & Samec, P. (2013). Uso de tecnologías en el entorno familiar en niños de cuatro años de Eslovenia. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación, 20 (40), 119–126. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-03-02

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5 , 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Levine, L. E., Waite, B. M., Bowman, L. L., & Kachinsky, K. (2019). Mobile media use by infants and toddlers. Computers in Human Behavior, 94 , 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.045

Levy, R. (2009). “You have to understand words … but not read them”: Young children becoming readers in a digital age. Journal of Research in Reading, 32 , 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2008.01382.x

Lewis, K. L., Howard, S. J., Verenikina, I., & Kervin, L. K. (2023). Parent perspectives on young children’s changing digital practices: Insights from Covid-19. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 21 (1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X221145486

Li, P., Legault, J., & Litcofsky, K. A. (2014). Neuroplasticity as a function of second language learning: Anatomical changes in the human brain. Cortex, 58 , 301–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2014.05.001

Lim, S. S. (2016). Through the tablet glass: transcendent parenting in an era of mobile media and cloud computing. Journal of Children and Media, 10 (1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2015.1121896

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2008). Parental mediation of children’s internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52 (4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

Madigan, S., Browne, D., Racine, N., Mori, C., & Tough, S. (2019). Association between screen time and children’s performance on a developmental screening test. JAMA Pediatrics, 173 (3), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5056

Mallawaarachchi, S. R., Anglim, J., Hooley, M., & Horwood, S. (2022). Associations of smartphone and tablet use in early childhood with psychosocial, cognitive and sleep factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60 , 13–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.12.008

Mascheroni, G., Ponte, C., & Jorge, A. (2018). Digital Parenting: The Challenges for Families in the Digital Age, Yearbook 2018 . University of Gothenburg.

McCarthy, D. M., & Bhide, P. G. (2021). Heritable consequences of paternal nicotine exposure: From phenomena to mechanisms. Biology of Reproduction, 105 (3), 632–643. https://doi.org/10.1093/biolre/ioab116

McCloskey, M., Johnson, S. L., Benz, C., Thompson, D. A., Chamberlin, B., Clark, L., & Bellows, L. L. (2018). Parent perceptions of mobile device use among preschool-aged children in rural head start centers. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 50 (1), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2017.03.006

McNeill, J., Howard, S. J., Vella, S. A., & Cliff, D. P. (2019). Longitudinal associations of electronic application use and media program viewing with cognitive and psychosocial development in preschoolers. Academic Pediatric, 19 , 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.02.010

Medawar, J., Tabullo, Á. J., & Gago-Galvagno, L. G. (2023). Early language outcomes in Argentinean toddlers: Associations with home literacy, screen exposure and joint media engagement. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 41 (1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12429

Mehta, S. K., & Murkey, B. (2020). Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic Imposed Lockdown on Internet Addiction. IAHRW International Journal of Social Sciences Review , 8 (7-9), 285–290. Retrieved from https://ischolar.sscldl.in/index.php/IIJSSR/article/view/208656

Montag, C., & Elhai, J. D. (2020). Discussing digital technology overuse in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: On the importance of considering Affective Neuroscience Theory. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 12 , 100313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100313

Neumann, M. M. (2018). Parent scaffolding of young children’s use of touch screen tablets. Early Child Development and Care, 188 (12), 1654–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1278215

Neumann, M. M. (2015). Young children and screen time: Creating a mindful approach to digital technology. Australian Educational Computing , 30 (2). http://journal.acce.edu.au/index.php/AEC/article/view/67 . Accessed 15 Apr 2023.

Nevski, E., & Siibak, A. (2016). The role of parents and parental mediation on 0–3-year olds’ digital play with smart devices: Estonian parents’ attitudes and practices. Early Years, 36 (3), 227–241. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429444418

Nikken, P., & de Haan, J. (2015). Guiding young children's internet use at home: Problems that parents experience in their parental mediation and the need for parenting support. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace , 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2015-1-3

Nikken, P., & Jansz, J. (2014). Developing scales to measure parental mediation of young children’s internet use. Learning, Media and Technology, 39 (2), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2013.782038

Nikken, P., & Opree, S. J. (2018). Guiding young children’s digital media use: SES-differences in mediation concerns and competence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27 (6), 1844–1857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1018-3

Nikken, P., & Schols, M. (2015). How and why parents guide the media use of young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 (11), 3423–3435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0144-4

Nur’Aini, A. (2022). The Effect of Parenting in the Digital Era on the Behavior of Elementary School Students. Jurnal Ilmiah Sekolah Dasar , 6 (4). https://doi.org/10.23887/jisd.v6i4.56036

Oh, W. O. (2005). Patterns of the internet usage and related factors with internet addiction among middle school students. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health, 9 (1), 33–49.

Pagani, L., Argentin, G., Gui, M., & Stanca, L. (2016). The impact of digital skills on educational outcomes: Evidence from performance tests. Educational Studies, 42 (2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2016.1148588

Papadakis, S., Zaranis, N., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2019). Parental involvement and attitudes towards young Greek children’s mobile usage. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 22 , 100144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2019.100144

Papadakis, S., Alexandraki, F., & Zaranis, N. (2022). Mobile device use among preschool-aged children in Greece. Education and Information Technologies, 27 (2), 2717–2750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10718-6

Park, C., & Park, Y. R. (2014). The conceptual model on smart phone addiction among early childhood. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 4 (2), 147. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJSSH.2014.V4.336

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Pons-Salvador, G., Zubieta-Méndez, X., & Frias-Navarro, D. (2022). Parents’ digital competence in guiding and supervising young children’s use of the Internet. European Journal of Communication, 37 (4), 443–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231211072669

Purnama, S., Wibowo, A., Narmaditya, B. S., Fitriyah, Q. F., & Aziz, H. (2022). Do parenting styles and religious beliefs matter for child behavioral problem? The mediating role of digital literacy. Heliyon, 8 (6), e09788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09788

Rek, M., & Kovačič, A. (2018). Media and Preschool children: The role of Parents as role Models and educaTors. Medijske studije, 9 (18), 27–43. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0928-1163 .

Rideout, V., & Robb, M. B. (2020). The Common Sense Census: Media use by kids age zero to eight, 2020 . Common Sense Media. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2020_zero_to_eight_census_final_web.pdf

Rideout, V. (2019). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2019 . Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Rode, J. A. (2009). Digital parenting: designing children’s safety. People and computers XXIII celebrating people and technology , 244–251. https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/HCI2009.29

Rohr, C. S., Arora, A., Cho, I. Y., Katlariwala, P., Dimond, D., Dewey, D., & Bray, S. (2018). Functional network integration and attention skills in young children. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 30 , 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.007

Sivrikova, N. V., Ptashko, T. G., Perebeynos, A. E., Chernikova, E. G., Gilyazeva, N. V., & Vasilyeva, V. S. (2020). Parental reports on digital devices use in infancy and early childhood. Education and Information Technologies, 25 (5), 3957–3973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10145-z

Stites, M. L., Sonneschein, S., & Galczyk, S. H. (2021). Preschool parents’ views of distance learning during COVID-19. Early Education and Development, 32 (7), 923–939. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.1930936

Strouse, G. A., Newland, L. A., & Mourlam, D. J. (2019). Educational and fun? Parent versus preschooler perceptions and co-use of digital and print media. AERA Open, 5 (3), 2332858419861085. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419861085

Thurlow, R. (2009). Improving emergent literacy skills: Web destinations for young children. Computers in the Schools, 26 , 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380560903360210

Timmons, K., Cooper, A., Bozek, E., & Braund, H. (2021). The impacts of COVID-19 on early childhood education: Capturing the unique challenges associated with remote teaching and learning in K-2. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49 (5), 887–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01207-z

Valkenburg, P. M., Krcmar, M., Peeters, A. L., & Marseille, N. M. (1999). Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation:“Instructive mediation”,“restrictive mediation”, and “social coviewing.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 43 (1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838159909364474

Wahyuningrum, E., Suryanto, S., & Suminar, D. R. (2020). Parenting in digital era: A systematic literature review. Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology, 3 , 226–258. https://doi.org/10.12928/jehcp.v9i3.16984

Wang, C., Qian, H., Li, H., & Wu, D. (2023). The status quo, contributors, consequences and models of digital overuse/problematic use in preschoolers: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology , 14 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1049102

Wartella, E., Kirkpatrick, E., Rideout, V., Lauricella, A., & Connell, S. (2014). Media, technology, and reading in Hispanic families: A national survey. Center on Media and Human Development at Northwestern University and National Center for Families Learning . http://web5.soc.northwestern.edu/cmhd/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/NWU.MediaTechReading.Hispanic.FINAL2014.pdf . Accessed 10 Mar 2023.

WHO. (2019). New WHO guidance: Very limited daily screen time recommended for children under 5. https://www.aoa.org/news/clinical-eye-care/public-health/screen-time-for-children-under-5?sso=y . Accessed 10 Mar 2023.

Wu, C. S. T., Fowler, C., Lam, W. Y. Y., Wong, H. T., Wong, C. H. M., & Yuen Loke, A. (2014). Parenting approaches and digital technology use of preschool-age children in a Chinese community. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 22 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-40-44

Wu, D., Dong, X., Liu, D., & Li, H. (2023). How Early Digital Experience Shapes Young Brains: A Scoping Review. Early Education and Development . https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2023.2278117

Xie, H., Peng, J., Qin, M., Huang, X., Tian, F., & Zhou, Z. (2018). Can touchscreen devices be used to facilitate young children’s learning? A meta-analysis of touchscreen learning effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 2580. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02580

Yang, H., Ng, W. Q., Yang, Y., & Yang, S. (2022). Inconsistent media mediation and problematic smartphone use in preschoolers: Maternal conflict resolution styles as moderators. Children, 9 (6), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060816

Yaşaroğlu, C., & Sönmez, D. (2022). Evaluating the digital parenting levels of parents of primary school students during the pandemic based on different variables. Research on Education and Media, 14 (2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.2478/rem-2022-0027

Download references

This research was funded by the Departmental Research Grant (Reference Number: DRG2022-23/008) at the Department of Early Childhood Education in the Education University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Early Childhood Education, Faculty of Education and Human Development, The Education University of Hong Kong, 10 Lo Ping Road, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong, Hong Kong S.A.R., China

Yun Nga Choy, Eva Yi Hung Lau & Dandan Wu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dandan Wu .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This manuscript is one of the chapters in Yun Nga Choy's EdD thesis.

See Table 5 .

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Choy, Y.N., Lau, E.Y.H. & Wu, D. Digital parenting and its impact on early childhood development: A scoping review. Educ Inf Technol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12643-w

Download citation

Received : 11 July 2023

Accepted : 21 March 2024

Published : 07 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12643-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital parenting

- Digital devices

- Scoping review

- Early digital use

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 20 February 2015

Qualitative Research in Early Childhood Education and Care Implementation

- Wendy K. Jarvie 1

International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy volume 6 , pages 35–43 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

66k Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

Governments around the world have boosted their early childhood education and care (ECEC) engagement and investment on the basis of evidence from neurological studies and quantitative social science research. The role of qualitative research is less understood and under-valued. At the same time the hard evidence is only of limited use in helping public servants and governments design policies that work on the ground. The paper argues that some of the key challenges in ECEC today require a focus on implementation. For this a range of qualitative research is required, including knowledge of organisational and parent behaviour, and strategies for generating support for change. This is particularly true of policies and programs aimed at ethnic minority children. It concludes that there is a need for a more systematic approach to analysing and reporting ECEC implementation, along the lines of “implementation science” developed in the health area.

Introduction

Research conducted over the last 15 years has been fundamental to generating support for ECEC policy reform and has led to increased government investments and intervention in ECEC around the world. While neurological evidence has been a powerful influence on ECEC policy practitioners, quantitative research has also been persuasive, particularly randomised trials and longitudinal studies providing evidence (1) on the impact of early childhood development experiences to school success, and to adult income and productivity, and (2) that properly constructed government intervention, particularly for the most disadvantaged children, can make a significant difference to those adult outcomes. At the same time the increased focus on evidence-informed policy has meant experimental/quantitative design studies have become the “gold standard” for producing knowledge (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005 ), and pressures for improved reporting and accountability have meant systematic research effort by government has tended to focus more on data collection and monitoring, than on qualitative research (Bink, 2007 ). In this environment the role of qualitative research has been less valued by senior government officials.

Qualitative Research-WhatIs It?

The term qualitative research means different things to different people (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005 ). For some researchers it is a way of addressing social justice issues and thus is part of radical politics to give power to the marginalised. Others see it simply as another research method that complements quantitative methodologies, without any overt political function. Whatever the definition of qualitative research, or its role, a qualitative study usually:

Features an in depth analysis of an issue, event, entity, or process. This includes literature reviews and meta studies that draw together findings from a number of studies.

Is an attempt to explain a highly complex and/or dynamic issue or process that is unsuited to experimental or quantitative analysis.

Includes a record of the views and behaviours of the players — it studies the world from the perspective of the participating individual.

Cuts across disciplines, fields and subject matter.

Uses a range of methods in one study, such as participant observation; in depth interviewing of participants, key stakeholders, and focus groups; literature review; and document analysis.

High quality qualitative research requires high levels of skill and judgement. Sometimes it requires pulling together information from a mosaic of data sources and can include quantitative data (the latter is sometimes called mixed mode studies). From a public official perspective, the weaknesses of qualitative research can include (a) the cost-it can be very expensive to undertake case studies if there are a large number of participants and issues, (b) the complexity — the reports can be highly detailed, contextually specific examples of implementation experience that while useful for service delivery and front line officials are of limited use for national policy development, (c) difficultyin generalising from poor quality and liable to researcher bias, and (d) focus, at times, more on political agendas of child rights than the most cost-effective policies to support the economic and social development of a nation. It has proved hard for qualitative research to deliver conclusions that are as powerful as those from quantitative research. Educational research too, has suffered from the view that education academics have over-used qualitative research and expert judgement, with little rigorous or quantitative verification (Cook & Gorard, 2007 ).

Qualitative Research and Early Childhood Education and Care

In fact, the strengths of qualitative ECEC research are many, and their importance for government, considerable. Qualitative research has been done in all aspects of ECEC operations and policies, from coordinating mechanisms at a national level (OECD, 2006 ), curriculum frameworks (Office for Children and Early Childhood Development, 2008 ), and determining the critical elements of preschool quality (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2003 ), to developing services at a community level including effective outreach practices and governance arrangements. Qualitative research underpins best practice guides and regulations (Bink, 2007 ). Cross country comparative studies on policies and programs rely heavily on qualitative research methods.

For public officials qualitative components of program evaluations are essential to understanding how a program has worked, and to what extent variation in outcomes and impacts from those expected, or between communities, are the result of local or national implementation issues or policy flaws. In addition, the public/participant engagement in qualitative components of evaluations can reinforce public trust in public officials and in government more broadly.

In many ways the contrast between quantitative and qualitative research is a false dichotomy and an unproductive comparison. Qualitative research complements quantitative research, for example, through provision of background material and identification of research questions. Much quantitative research relies on qualitative research to define terms, and to identify what needs to be measured. For example, the Effective Provision of PreSchool Education (EPPE) studies, which have been very influential and is a mine of information for policy makers, rely on initial qualitative work on what is quality in a kindergarten, and how can it be assessed systematically (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2003 ). Qualitative research too can elucidate the “how” of a quantitative result. For example, quantitative research indicates that staff qualifications are strongly associated with better child outcomes, but it is qualitative work that shows that it is not the qualification per se that has an impact on child outcomes-rather it is the ability of staff to create a high quality pedagogic environment (OECD, 2012 ).

Challenges of Early Childhood Education and Care

Systematic qualitative research focused on the design and implementation of government programs is essential for governments today.

Consider some of the big challenges facing governments in early childhood development (note this is not a complete list):

Creating coordinated national agendas for early childhood development that bring together education, health, family and community policies and programs, at national, provincial and local levels (The Lancet, 2011 ).

Building parent and community engagement in ECEC/Early Childhood Development (ECD), including increasing parental awareness of the importance of early childhood services. In highly disadvantaged or dysfunctional communities this also includes increasing their skills and abilities to provide a healthy, stimulating and supportive environment for young children, through for example parenting programs (Naudeau, Kataoka, Valerio, Neuman & Elder, 2011 ; The Lancet, 2011 ; OECD, 2012 ).

Strategies and action focused on ethnic minority children, such as outreach, ethnic minority teachers and teaching assistants and informal as well as formal programs.

Enhancing workforce quality, including reducing turnover, and improved practice (OECD, 2012 ).

Building momentum and advocacy to persuade governments to invest in the more “invisible” components of quality such as workforce professional development and community liaison infrastructure; and to maintain investment over significant periods of time (Jarvie, 2011 ).

Driving a radical change in the way health/education/familyservicepro fessions and their agencies understand each other and to work together. Effectively integrated services focused on parents, children and communities can only be achieved when professions and agencies step outside their silos (Lancet, 2011 ). This would include redesign of initial training and professional development, and fostering collaborations in research, policy design and implementation.

There are also the ongoing needs for,

Identifying and developing effective parenting programs that work in tandem with formal ECEC provision.

Experiments to determine if there are lower cost ways of delivering quality and outcomes for disadvantaged children, including the merits of adding targeted services for these children on the base of universal services.

Figuring out how to scale up from successful trials (Grunewald & Rolnick, 2007 ; Engle et al., 2011 ).

Working out how to make more effective transitions between preschool and primary school.

Making research literature more accessible to public officials (OECD, 2012 ).

Indeed it can be argued that some of the most critical policy and program imperatives are in areas where quantitative research is of little help. In particular, qualitative research on effective strategies for ethnic minority children, their parents and their communities, is urgently needed. In most countries it is the ethnic minority children who are educationally and economically the most disadvantaged, and different strategies are required to engage their parents and communities. This is an area where governments struggle for effectiveness, and public officials have poor skills and capacities. This issue is common across many developed and developing countries, including countries with indigenous children such as Australia, China, Vietnam, Chile, Canada and European countries with migrant minorities (OECD, 2006 ; COAG, 2008 ; World Bank, 2011 ). Research that is systematic and persuasive to governments is needed on for example, the relative effectiveness of having bilingual environments and ethnic minority teachers and teaching assistants in ECEC centres, compared to the simpler community outreach strategies, and how to build parent and community leadership.

Many countries are acknowledging that parental and community engagement is a critical element of effective child development outcomes (OECD, 2012 ). Yet public officials, many siloed in education and child care ministries delivering formal ECEC services, are remote from research on raising parent awareness and parenting programs. They do not see raising parental skills and awareness as core to their policy and program responsibilities. Improving parenting skills is particularly important for very young children (say 0–3) where the impact on brain development is so critical. It has been argued there needs to be a more systematic approach to parenting coach/support programs, to develop a menu of options that we know will work, to explore how informal programs can work with formal programs, and how health programs aimed young mothers or pregnant women can be enriched with education messages (The Lancet, 2011 ).

Other areas where qualitative research could assist are shown in Table 1 (see p. 40).

Implementation Science in Early Childhood Education and Care

Much of the suggested qualitative research in Table 1 is around program design and implementation . It is well-known that policies often fail because program design has not foreseen implementation issues or implementation has inadequate risk management. Early childhood programs are a classic example of the “paradox of non-evidence-based implementation of evidence-based practice” (Drake, Gorman & Torrey, 2005). Governments recognise that implementation is a serious issue: there may be a lot of general knowledge about “what works”, but there is minimal systematic information about how things actually work . One difficulty is that there is a lack of a common language and conceptual framework to describe ECEC implementation. For example, the word “consult” can describe a number of different processes, from public officials holding a one hour meeting with available parents in alocation,to ongoing structures set up which ensureall communityelementsare involved and reflect thespectrum of community views, and tocontinue tobuild up community awareness and engagement over time.

There is a need to derive robust findingsof generic value to public officials, for program design. In the health sciences, there is a developing literature on implementation, including a National implementation Research Network based in the USA, and a Journal of Implementation Science (Fixsen, Naoom, Blasé, Friedman & Wallace, 2005 ). While much of the health science literature is focused on professional practice, some of the concepts they have developed are useful for other fields, such as the concept of “fidelity” of implementation which describes the extent to which a program or service has been implemented as designed. Education program implementation is sometimes included in these fora, however, there is no equivalent significant movement in early childhood education and care.

A priority in qualitative research for ECEC of value to public officials would then appear to be a systematic focus on implementation studies, which would include developing a conceptual framework and possibly a language for systematic description of implementation, as well as, meta-studies. This need not start from scratch-much of the implementation science literature in health is relevant, especially the components around how to influence practitioners to incorporate latest evidence-based research into their practice, and the notions of fidelity of implementation. It could provide an opportunity to engage providers and ECE professionals in research, where historically ECEC research has been weak.

Essential to this would be collaborative relationships between government agencies, providers and research institutions, so that there is a flow of information and findings between all parties.

Quantitative social science research, together with studies of brain development, has successfully made the case for greater investment in the early years.There has been less emphasis on investigating what works on the ground especially for the most disadvantaged groups, and bringing findings together to inform government action. Yet many of the ECEC challenges facing governments are in implementation, and in ensuring that interventions are high quality. This is particularly true of interventions to assist ethnic minority children, who in many countries are the most marginalised and disadvantaged. Without studies that can improve the quality of ECEC implementation, governments, and other bodies implementing ECEC strategies, are at risk of not delivering the expected returns on early childhood investment. This could, over time, undermine the case for sustained government support.