Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating assignments.

Here are some general suggestions and questions to consider when creating assignments. There are also many other resources in print and on the web that provide examples of interesting, discipline-specific assignment ideas.

Consider your learning objectives.

What do you want students to learn in your course? What could they do that would show you that they have learned it? To determine assignments that truly serve your course objectives, it is useful to write out your objectives in this form: I want my students to be able to ____. Use active, measurable verbs as you complete that sentence (e.g., compare theories, discuss ramifications, recommend strategies), and your learning objectives will point you towards suitable assignments.

Design assignments that are interesting and challenging.

This is the fun side of assignment design. Consider how to focus students’ thinking in ways that are creative, challenging, and motivating. Think beyond the conventional assignment type! For example, one American historian requires students to write diary entries for a hypothetical Nebraska farmwoman in the 1890s. By specifying that students’ diary entries must demonstrate the breadth of their historical knowledge (e.g., gender, economics, technology, diet, family structure), the instructor gets students to exercise their imaginations while also accomplishing the learning objectives of the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1989, p. 25).

Double-check alignment.

After creating your assignments, go back to your learning objectives and make sure there is still a good match between what you want students to learn and what you are asking them to do. If you find a mismatch, you will need to adjust either the assignments or the learning objectives. For instance, if your goal is for students to be able to analyze and evaluate texts, but your assignments only ask them to summarize texts, you would need to add an analytical and evaluative dimension to some assignments or rethink your learning objectives.

Name assignments accurately.

Students can be misled by assignments that are named inappropriately. For example, if you want students to analyze a product’s strengths and weaknesses but you call the assignment a “product description,” students may focus all their energies on the descriptive, not the critical, elements of the task. Thus, it is important to ensure that the titles of your assignments communicate their intention accurately to students.

Consider sequencing.

Think about how to order your assignments so that they build skills in a logical sequence. Ideally, assignments that require the most synthesis of skills and knowledge should come later in the semester, preceded by smaller assignments that build these skills incrementally. For example, if an instructor’s final assignment is a research project that requires students to evaluate a technological solution to an environmental problem, earlier assignments should reinforce component skills, including the ability to identify and discuss key environmental issues, apply evaluative criteria, and find appropriate research sources.

Think about scheduling.

Consider your intended assignments in relation to the academic calendar and decide how they can be reasonably spaced throughout the semester, taking into account holidays and key campus events. Consider how long it will take students to complete all parts of the assignment (e.g., planning, library research, reading, coordinating groups, writing, integrating the contributions of team members, developing a presentation), and be sure to allow sufficient time between assignments.

Check feasibility.

Is the workload you have in mind reasonable for your students? Is the grading burden manageable for you? Sometimes there are ways to reduce workload (whether for you or for students) without compromising learning objectives. For example, if a primary objective in assigning a project is for students to identify an interesting engineering problem and do some preliminary research on it, it might be reasonable to require students to submit a project proposal and annotated bibliography rather than a fully developed report. If your learning objectives are clear, you will see where corners can be cut without sacrificing educational quality.

Articulate the task description clearly.

If an assignment is vague, students may interpret it any number of ways – and not necessarily how you intended. Thus, it is critical to clearly and unambiguously identify the task students are to do (e.g., design a website to help high school students locate environmental resources, create an annotated bibliography of readings on apartheid). It can be helpful to differentiate the central task (what students are supposed to produce) from other advice and information you provide in your assignment description.

Establish clear performance criteria.

Different instructors apply different criteria when grading student work, so it’s important that you clearly articulate to students what your criteria are. To do so, think about the best student work you have seen on similar tasks and try to identify the specific characteristics that made it excellent, such as clarity of thought, originality, logical organization, or use of a wide range of sources. Then identify the characteristics of the worst student work you have seen, such as shaky evidence, weak organizational structure, or lack of focus. Identifying these characteristics can help you consciously articulate the criteria you already apply. It is important to communicate these criteria to students, whether in your assignment description or as a separate rubric or scoring guide . Clearly articulated performance criteria can prevent unnecessary confusion about your expectations while also setting a high standard for students to meet.

Specify the intended audience.

Students make assumptions about the audience they are addressing in papers and presentations, which influences how they pitch their message. For example, students may assume that, since the instructor is their primary audience, they do not need to define discipline-specific terms or concepts. These assumptions may not match the instructor’s expectations. Thus, it is important on assignments to specify the intended audience http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm (e.g., undergraduates with no biology background, a potential funder who does not know engineering).

Specify the purpose of the assignment.

If students are unclear about the goals or purpose of the assignment, they may make unnecessary mistakes. For example, if students believe an assignment is focused on summarizing research as opposed to evaluating it, they may seriously miscalculate the task and put their energies in the wrong place. The same is true they think the goal of an economics problem set is to find the correct answer, rather than demonstrate a clear chain of economic reasoning. Consequently, it is important to make your objectives for the assignment clear to students.

Specify the parameters.

If you have specific parameters in mind for the assignment (e.g., length, size, formatting, citation conventions) you should be sure to specify them in your assignment description. Otherwise, students may misapply conventions and formats they learned in other courses that are not appropriate for yours.

A Checklist for Designing Assignments

Here is a set of questions you can ask yourself when creating an assignment.

- Provided a written description of the assignment (in the syllabus or in a separate document)?

- Specified the purpose of the assignment?

- Indicated the intended audience?

- Articulated the instructions in precise and unambiguous language?

- Provided information about the appropriate format and presentation (e.g., page length, typed, cover sheet, bibliography)?

- Indicated special instructions, such as a particular citation style or headings?

- Specified the due date and the consequences for missing it?

- Articulated performance criteria clearly?

- Indicated the assignment’s point value or percentage of the course grade?

- Provided students (where appropriate) with models or samples?

Adapted from the WAC Clearinghouse at http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm .

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

- Books, Articles, & More

- Curriculum Library

- Archives & Special Collections

- Scholars Crossing

- Research Guides

- Student Support

- Faculty Support

- Interlibrary Loan

APA Writing Guide: Formatting for Graduate Students

- Formatting for Undergraduates

- Formatting for Graduate Students

- In-text Citations

- Books and Ebooks

- Journal Articles

- Misc.Citations

Writing Center

The Liberty University Writing Center is available to provide writing coaching to students. Residential students should contact the On-Campus Writing Center for assistance. Online students should contact the Online Writing Center for assistance.

General Rules

Liberty University has determined that graduate students will use APA 7’s formatting guidelines for professional papers. To assist you, Liberty University's Writing Center provides a template paper and a sample paper .

For professional papers, the following four sections are required:

- Title Page with Running Head

- Abstract with Keywords

- Reference List

Here are a few things to keep in mind as you format your paper:

- Fonts - LU recommends that papers be typed in 12-point Times New Roman or 11-point Calibri fonts.

- Use only one space at the end of each sentence in the body of your paper.

- In general, APA papers should be double spaced throughout. A list of exceptions can be found here.

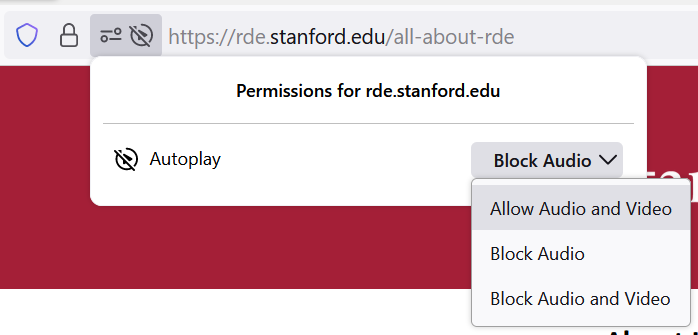

- To make sure that your paper is double spaced throughout, select the text , right click , select ' Paragraph ,' and look under the section ' Line Spacing ' as shown below:

- Margins/Alignment - Your paper should use 1-inch margins on standard-sized paper (8.5' X 11'). Make sure that you use Align Left (CTRL + L) on the paper, except for the title page.

- Indentation – The first sentence in each new paragraph in the body of the paper should be indented a half inch. The abstract, however, should not be indented. References use hanging indentation .

- Headings: Please note that all headings are in title case. Level 1 headings should be centered (and in bold), and Level 2 and 3 headings should be left-aligned (and in bold or bold italic, respectively). Level 4 and 5 headings are indented like regular paragraphs. An example of formatting headings in a paper is available here

Title Page: When setting up the professional title page, please note the following elements should be present on the page:

- There is no limit to the number of words in the title.

- Add an extra blank double-spaced line between the title and author’s name.

- Name of each author (centered)

- Name of department and institution/affiliation (centered)

- Place the author note in the bottom half of the title page. Center and bold the label “Author Note.” Align the paragraphs of the author note to the left. For an example, see the LU Writing Center template for graduate students here .

- Page number in top right corner of the header, starting with page 1 on the title page

- The running head is an abbreviated version of the title of your paper (or the full title if the title is already short).

- Type the running head in all-capital letters.

- Ensure the running head is no more than 50 characters, including spaces and punctuation.

- The running head appears in the same format on every page, including the first page.

- Do not use the label “Running head:” before the running head.

- Align the running head to the left margin of the page header, across from the right-aligned page number.

Abstract Page: The abstract page includes the abstract and related keywords.

The abstract is a brief but comprehensive summary of your paper. Here are guidelines for formatting the abstract:

- It should be the second page of a professional (graduate level) paper.

- The first line should say “Abstract” centered and in bold.

- The abstract should start one line below the section label.

- It should be a single paragraph and should not be indented.

- It should not exceed 250 words.

Keywords are used for indexing in databases and as search terms. Your keywords should capture the most important aspects of your paper in three to five words, phrases, or acronyms. Here are formatting guidelines:

- Label “ Keywords ” one line below the abstract, indented and in italics (not bolded).

- The keywords should be written on the same line as and one space after the label “ Keywords ”.

- The keywords should be lowercase (but capitalize proper nouns) and not italic or bold.

- Each keyword should be separated by a comma and a space and followed by a colon.

- There should be no ending punctuation.

- << Previous: Formatting for Undergraduates

- Next: In-text Citations >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2023 11:29 AM

- URL: https://libguides.liberty.edu/APAguide

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Types of Assignments

Gen Ed courses transcend disciplinary boundaries in a variety of ways, so the types of writing assignments that they include also often venture outside the traditional discipline-specific essays. You may encounter a wide variety of assignment types in Gen Ed, but most can be categorized into four general types:

- Traditional academic assignments include the short essays or research papers most commonly associated with college-level assignments. Generally speaking, these kinds of assignments are "expository" in nature, i.e., they ask you to engage with ideas through evidence-base argument, written in formal prose. The majority of essays in Expos courses fall into this category of writing assignment types.

- Less traditional academic assignments include elements of engagement in academia not normally encountered by undergraduates.

- Traditional non-academic assignments include types of written communication that students are likely to encounter in real world situations.

- Less traditional non-academic assignments are those that push the boundaries of typical ‘writing’ assignments and are likely to include some kind of creative or artistic component.

Examples and Resources

Traditional academic.

For most of us, these are the most familiar types of college-level writing assignments. While they are perhaps less common in Gen Ed than in departmental courses, there are still numerous examples we could examine.

Two illustrations of common types include:

Example 1: Short Essay Professor Michael Sandel asks the students in his Gen Ed course on Tech Ethics to write several short essays over the course of the semester in which they make an argument in response to the course readings. Because many students will never have written a philosophy-style paper, Professor Sandel offers students a number of resources—from a guide on writing in philosophy, to sample graded essays, to a list of logical fallacies—to keep in mind.

Example 2: Research Paper In Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Cares?, a Gen Ed course co-taught by multiple global health faculty members, students write a 12–15 page research paper on a biosocial analysis of a global health topic of their choosing for the final assignment. The assignment is broken up into two parts: (1) a proposal with annotated bibliography and (2) the final paper itself. The prompt clearly outlines the key qualities and features of a successful paper, which is especially useful for students who have not yet written a research paper in the sciences.

Less Traditional Academic

In Gen Ed, sometimes assignments ask students to engage in academic work that, while familiar to faculty, is beyond the scope of the typical undergraduate experience.

Here are a couple of examples from Gen Ed courses:

Example 1: Design a conference For the final project in her Gen Ed course, Global Feminisms, Professor Durba Mitra asks her students to imagine a dream conference in the style of the feminist conferences they studied in class. Students are asked to imagine conference panels and events, potential speakers or exhibitions, and advertising materials. While conferences are a normal occurrence for graduate students and professors, undergraduates are much less likely to be familiar with this part of academic life, and this kind of assignment might require more specific background and instructions as part of the prompt.

Example 2: Curate a museum exhibit In his Gen Ed class, Pyramid Schemes, Professor Peter Der Manuelian's final project offers students the option of designing a virtual museum exhibit . While exhibit curation can be a part of the academic life of an anthropologist or archaeologist, it's not often found in introductory undergraduate courses. In addition to selecting objects and creating a virtual exhibit layout, students also wrote an annotated bibliography as well as an exhibit introduction for potential visitors.

Traditional Non-academic

One of the goals of Gen Ed is to encourage students to engage with the world around them. Sometimes writing assignments in Gen Ed directly mirror types of writing that students are likely to encounter in real-world, non-academic settings after they graduate.

The following are several examples of such assignments:

Example 1: Policy memo In Power and Identity in the Middle East, Professor Melani Cammett assigns students a group policy memo evaluating "a major initiative aimed at promoting democracy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)." The assignment prompt is actually structured as a memo, providing context for students who likely lack experience with the format. It also outlines the key characteristics of a good memo, and it provides extensive advice on the process—especially important when students are working in groups.

Example 2: Letter In Loss, Professor Kathleen Coleman asks students to write a letter of condolence . The letter has an unusual audience: a mother elephant who lost her calf. Since students may not have encountered this type of writing before, Professor Coleman also provides students with advice on process, pointing to some course readings that might be a good place to start. She also suggests a list of outside resources to help students get into the mindframe of addressing an elephant.

Example 3: Podcast Podcasts are becoming increasingly popular in Gen Ed classes, as they are in the real world. Though they're ultimately audio file outputs, they usually require writing and preparing a script ahead of time. For example, in Music from Earth, Professor Alex Rehding asks students to create a podcast in which they make an argument about a song studied in class. He usefully breaks up the assignments into two parts: (1) researching the song and preparing a script and (2) recording and making sonic choices about the presentation, offering students the opportunity to get feedback on the first part before moving onto the second.

Less Traditional Non-academic

These are the types of assignments that perhaps are less obviously "writing" assignments. They usually involve an artistic or otherwise creative component, but they also often include some kind of written introduction or artist statement related to the work.

The following are several examples from recently offered Gen Ed courses:

Example 1: Movie Professor Peter Der Manuelian offers students in his class, Pyramid Schemes, several options for the final project, one of which entails creating a 5–8 minute iMovie making an argument about one of the themes of the course. Because relatively few students have prior experience making films, the teaching staff provide students with a written guide to making an iMovie as well as ample opportunities for tech support. In addition to preparing a script as part of the production, students also submit both an annotated bibliography and an artist’s statement.

Example 2: Calligram In his course, Understanding Islam and Contemporary Muslim Societies, Professor Ali Asani asks students to browse through a provided list of resources about calligrams, which are an important traditional Islamic art form. Then they are required to "choose a concept or symbol associated with God in the Islamic tradition and attempt to represent it through a calligraphic design using the word Allah," in any medium they wish. Students also write a short explanation to accompany the design itself.

Example 3: Soundscape In Music from Earth, Professor Alex Rehding has students create a soundscape . The soundscape is an audio file which involves layering sounds from different sources to create a single piece responding to an assigned question (e.g. "What sounds are characteristic of your current geographical region?"). Early on, as part of the development of the soundscape, students submit an artist's statement that explains the plan for the soundscape, the significance of the sounds, and the intention of the work.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Receiving Feedback

Assignment Decoder

Preparing for Graduate School: Advice for New Student Success

The idea of going back to graduate school as a working adult presents both opportunities and challenges. Here are a few tips for setting yourself up for success in graduate school and beyond.

Maxine Giza

When you’re considering going back to school, choosing the right graduate program is a challenging first step. But perhaps even more daunting is the next step: preparing for success in graduate school.

The thought of juggling classwork with your job and family commitments can be overwhelming. After all, you have made a major commitment in both time and money. But don’t worry. Countless professionals have successfully completed their degree while continuing to work full time. And you will, too!

Life as a graduate student is different from what you remember from your undergraduate days. Professors expect you to be more proactive and self-sufficient. You also likely have many other priorities in your life — from professional responsibilities to family obligations — competing for your time.

If you have been out of school for a few years, you may also notice differences in teaching tools and techniques.

“University instruction has changed dramatically over the past few years, especially with the increase of online courses,” says Kelly Ross, predegree and admissions advisor at Harvard Extension School.

Properly preparing for graduate school before you start your first class can help you start your semester off right and overcome unforeseen challenges that may arise.

Here are four questions to ask yourself as you begin the process of preparing for graduate school .

1. How will you approach work/life/school balance?

Achieving a healthy and appropriate work/life balance can be a struggle for anyone. Toss graduate school into the mix and you have a recipe for stress. While you won’t be able to completely eliminate stress, there are things you can do to minimize it.

Figuring out how to restructure your time is key.

You need to be honest with your friends and family about how graduate school is going to make your schedule less flexible than what they may be accustomed to.

Many people find that establishing a schedule works well.

Consider carving out specific times in the week for projects, studying, friends, family, and activities like going to the gym. There will certainly be times you’ll have to say no to social functions. But planning ahead carefully will help you avoid schedule conflicts and the scramble to get assignments completed on time.

It’s also important to seek out flexibility in your schedule wherever possible.

Consider talking to your employer about flex time and working from home. Depending on your academic program, consider online courses to save you time on commuting. At Harvard Extension School, for example, most degree and certificate programs are online.

Also, be honest with yourself about what you can handle. Avoid the temptation to take on too much.

“Remember to be as realistic as possible when deciding how many courses to take per term,” says Ross.

Remember that a graduate course may only meet for two hours per week. But it will require a significant amount of time outside of the classroom to complete the readings and assignments.

Learn how these Harvard Extension School alumni juggled their work/life balance .

Explore Graduate Degrees and Certificates at Harvard Extension School.

2. Who can you recruit to be your support network?

Your friends and family may initially struggle to accept that graduate school is going to take up time that you used to spend with them.

Make it clear why you are continuing your education. If they understand why graduate school is important to you, they can find ways to support you.

If you have children or are caring for elderly relatives, you’ll need to figure out who can step in to lend a hand. If you are a parent with young children, for example, you’ll want to make sure you have adequate child care in place before your first class even starts.

Don’t forget your classmates can serve as a support network as well.

It’s likely you’ll have classmates who are also balancing work and family commitments. You can gain insight from their experiences . Nothing compares to learning from people who are coping with the same struggles as you are.

3. What do you need to feel prepared for your first class?

Are you feeling anxious about returning to the rigors of academic life? One way to prepare for graduate school coursework is to review your syllabus before the class starts so you know when all major assignments are due. This will help you allocate your time around family and work commitments.

Knowing what your instructors will expect will also motivate you to develop a strategy to avoid procrastination , schedule conflicts, and last-minute scrambling.

If you went to college years ago, you may have memories of lugging heavy textbooks around. Today, however, many resources are accessible online.

You’ll want to make sure you have all the necessary technology at your fingertips before your program starts. For example, will you need programs like Microsoft Excel or Word? Do you need a stronger Internet connection for online classes?

You may even need to invest in a dedicated computer. While a family can share one computer for casual use, you may need your own device — especially if taking online courses.

4. How will you face unexpected challenges?

Even the most prepared graduate student will face unexpected challenges during their time as a graduate student. As the old saying goes, “expect the unexpected.”

Being flexible with your time is key to handling life when things don’t go according to plan.

And remember: some of the toughest challenges you’ll face may be psychological.

“A major challenge that many (students) don’t necessarily expect but begin experiencing is imposter syndrome,” says Ross.

Imposter syndrome —feelings of inadequacy and doubt in your abilities, and that you will soon be seen as a fraud—is common for many graduate students, especially at the beginning of graduate school.

“Imposter syndrome can be really difficult to overcome,” says Ross. “But students should just take it one day at a time, one assignment at a time, one class at a time. It’s likely that many of your classmates are experiencing it too but no one is talking about it.”

Remind yourself that yes, you DO belong in the program you’re in!

Preparation for graduate school is key to your success. Keep your end goal in sight and the payoff will make all the temporary sacrifices worth it.

Ready to get started? Find the program that’s right for you.

Browse Degree and Certificate Programs at Harvard Extension School.

About the Author

Maxine Giza is a Digital Content Producer. She is a graduate of Endicott College and Emerson College. When she isn’t thinking of creative ways to tell stories, Maxine can be found playing hockey, training for a road race or attempting to swing a golf club.

Graduate Certificate vs. Master’s Degree: What’s the Difference?

Learn the similarities and differences between these two postgraduate academic credentials.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

10 Types of Assignments in Online Degree Programs

Students may respond to recorded video lectures, participate in discussion boards and write traditional research papers.

(Getty Images) |

Learn What to Expect

Experts say online degree programs are just as rigorous as those offered on campus. Prospective online students should expect various types of coursework suited for a virtual environment, such as discussion boards or wikis, or more traditional research papers and group projects .

Here are 10 types of assignments you may encounter in online courses.

Read or Watch, Then Respond

An instructor provides a recorded lecture, article or book chapter and requires students to answer questions. Students generally complete the assignment at their own pace, so long as they meet the ultimate deadline, Bradley Fuster, associate vice president of institutional effectiveness at SUNY Buffalo State , wrote in a recent U.S. News blog post .

(Jessica Peterson | Getty Images)

Discussion Boards

The discussion forum is a major part of many online classes, experts say, and often supplements weekly coursework. Generally, the professor poses a question, and students respond to the prompt as well as each other. Sometimes, students must submit their own post before seeing classmates' answers.

"Good response posts are response posts that do not only agree or disagree," Noam Ebner, who then led the online graduate program in negotiation and conflict resolution at Creighton University 's law school, told U.S. News in 2015. "When you read another student's post, you have the ability to expand the conversation."

(Ariel Skelley | Getty Images)

Group Projects

Just because online students may live around the world doesn't mean they won't complete group work. Students may use Google Docs to edit assignments, email to brainstorm ideas and software such as Zoom to videoconference. Katy Katz, who earned an online MBA in 2013 at Benedictine University in Illinois, used both Skype and a chat feature in her online classroom to communicate with classmates.

"That was a good way for our instructor to see that everyone was participating," she told U.S. News in 2015. "Any planning we did – if there were going to be changes to meeting times – we would communicate in that chat area."

(Dave and Les Jacobs | Getty Images)

Virtual Presentations

Students may also give either live or recorded presentations to their classmates. At Colorado State University—Global Campus , for example, students use various video technologies and microphones for oral presentations, or software such as Prezi for more visual assignments, says Karen Ferguson, the online school's vice provost.

Oftentimes, Ferguson says, "They're using the technology that they will use in their field."

(Westend61 | Getty Images)

Like on-campus courses, online courses may have exams , depending on the discipline. These may be proctored at a local testing center, or an actual human may monitor online students through their webcam. Companies such as ProctorU make this possible.

In other cases, students may take online exams while being monitored by a computer. Automated services including ProctorTrack can keep track of what's happening on an online student's screen in case there are behaviors that may indicate cheating.

(Dr T J Martin | Getty Images)

Research Papers

Formal research papers, wrote Buffalo State's Fuster, remain common in online courses, as this type of writing is important in many disciplines, especially at the graduate level .

While there are few differences between these assignments for online and on-ground courses, online students should ensure their program offers remote access to a university's library and its resources, which may include live chats with staff, experts say.

(golibo | Getty Images)

Case Studies and Real-World Scenarios

When it comes to case studies, a reading or video may provide detailed information about a specific situation related to the online course material, Fuster wrote. Students analyze the presented issues and develop solutions.

Real-world learning can also take other forms, says Brian Worden, manager of curriculum and course development for several schools at the for-profit Capella University . In online psychology degree programs, students may hold mock therapy sessions through videoconferencing. In the K-12 education online master's program , they create lesson plans and administer them to classmates.

(Tetra Images | Getty Images)

These are particularly useful in online courses where students reflect on personal experiences, internships or clinical requirements , Fuster wrote. Generally, these are a running dialogue of a student's thoughts or ideas about a topic. They may update their blogs throughout the course, and in some cases, their classmates can respond.

(vertmedia | Getty Images)

These allow students to comment on and edit a shared document to write task lists, answer research questions, discuss personal experiences or launch discussions with classmates. They are particularly beneficial when it comes to group work, Fuster wrote.

"A blog, a wiki, even building out portfolios – we see a lot of those in communications, marketing and some of our business programs ," says Ferguson, of CSU—Global. "You may not see as much of that in accounting," for example, where students focus more on specific financial principles.

(Nalinratana Phiyanalinmat | EyeEm

A journal assignment allows an online student to communicate with his or her professor directly. While topics are sometimes assigned, journals often enable students to express ideas, concerns, opinions or questions about course material, Fuster wrote.

(Yuri_Arcurs | Getty Images)

More About Online Education

Learn more about selecting an online degree program by checking out the U.S. News 2017 Best Online Programs rankings and exploring the Online Learning Lessons blog.

For more advice, follow U.S. News Education on Twitter and Facebook .

2024 Best Online Programs

Compare online degree programs using the new U.S. News rankings and data.

You May Also Like

20 lower-cost online private colleges.

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

Basic Components of an Online Course

Cole Claybourn March 19, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

Online Programs With Diverse Faculty

Sarah Wood Feb. 16, 2024

Online Learning Trends to Know Now

Sarah Wood Feb. 8, 2024

Top Online MBAs With No GMAT, GRE

Cole Claybourn Feb. 8, 2024

Veterans Considering Online College

Anayat Durrani Feb. 8, 2024

Affordable Out-of-State Online Colleges

Sarah Wood Feb. 7, 2024

The Cost of an Online Bachelor's Degree

Emma Kerr and Cole Claybourn Feb. 7, 2024

How to Select an Online College

Cole Claybourn Feb. 7, 2024

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

99 Free Online Resources for Graduate Students

Reviewed by David Krug David Krug is a seasoned expert with 20 years in educational technology (EdTech). His career spans the pivotal years of technology integration in education, where he has played a key role in advancing student-centric learning solutions. David's expertise lies in marrying technological innovation with pedagogical effectiveness, making him a valuable asset in transforming educational experiences. As an advisor for enrollment startups, David provides strategic guidance, helping these companies navigate the complexities of the education sector. His insights are crucial in developing impactful and sustainable enrollment strategies.

Updated: February 26, 2024 , Reading time: 40 minutes

Share this on:

Find your perfect college degree

In this article, we will be covering...

Grad school is an even tougher hurdle to conquer than college; any grad student can attest to this. But with loads of free resources on the web these days, navigating higher ed has become more efficient and manageable.

Take Advantage of Online Learning

As the world shifts from traditional learning setups to remote or distance learning, or blended learning in some cases, these online resources are now essential tools for grad students.

These resources come in many forms, like online databases, search engines, niche sites, OCWs, OERs, MOOCs, online tools, and pages that write about grad school topics and everything in between that can help students thrive and survive grad school.

Free Online Resources

Check out this extensive list of free online resources for grad students. The resources are listed in random order and category. Browse away!

MIT OpenCourseWare

A self-guided tool initiated in 2001, the MIT OpenCourseWare (MIT OCW) was created by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a free repository of all the school’s materials for both undergraduate and graduate students. There is no need to register to freely access, download, and even share the courses, and these can be taken anytime.

MIT OCW contains close to 2500 materials from its various graduate course offerings – from business topics to the liberal arts to STEM courses. Graduate-level courses in sustainable energies, medicine, and education are also available. Video lectures and podcasts are also available on the MIT OCW YouTube channel .

UC Berkeley Digital Learning Services (DLS)

The Digital Learning Services (DLS) of UC Berkeley is a portal for both UC grad students and faculty who are gearing up for the transition to remote instruction and learning. Its Learning Management System, bCourses (also known as Canvas), is an online tool available to Berkeley students.

By using their CalCentral or bCourses account credentials, they can access learning materials uploaded by their instructors. The portal also allows for interactive learning, collaboration, and discussions with the faculty and fellow grad students. Course grades are also uploaded here so students can track their progress.

OpenStax is an initiative of Rice University that creates and publishes textbooks online for free, while hard copies can be bought for a low price. Its textbook collection is regularly peer-reviewed by educator-authors for accuracy, relevance, and standardization of outline, ensuring that the materials can be easily incorporated into any level of tertiary and or graduate learning.

OpenStax also supports mobility across devices and platforms, as it is also available on Google Play , the App Store , and YouTube .

UMass Boston OCW

The Umass Boston OpenCour s eWare is an open repository of educational materials in the form of lecture notes, audio lectures, and laboratory coursework (if any). No account registration is required, and the site can be freely accessed by anyone, anywhere.

Though none of the courses featured offer credits or certificates, the course listing is well-varied, which includes STEM courses like biology and computer science, psychology, creatives like performing arts, public policy and politics, natural sciences, history, and early and special education.

MITx on edX

Hosted on the MOOC platform edX, MITx is MIT’s most comprehensive MOOC offering. Its collection is similar to that of MITOCW’s, but it also has graded course works, live discussions with MIT faculty, and peer discussion boards. Many courses are free, while some, especially those that offer completion certificates and micro master’s degrees , include a modest fee.

The micro master’s track can also be credited as a full semester, thus allowing graduate students to continue with the corresponding full master’s program on campus. The following are MITx’s micro master’s offerings: 1) Supply Chain Management, 2) Data, Economics, and Development, 3) Principles of Manufacturing, 4) Statistics and Data Science, and 5) Finance.

Those who are on MITx are strongly suggested to explore and utilize the MIT OCW for a more complementary learning experience.

The Purdue Online Writing Lab or OWL is a free-for-use resource for aspiring – and even experienced – writers. The portal was created as a complement to Purdue University’s in-house and in-person writing tutorial service – The Writing Lab . Various writing instructional resources are available to those who are on a creative writing track.

Specific resources on the citation for research work , with provisioned guides for the following writing styles: APA 6 th and 7 th edition, MLA, Chicago, IEEE, AMA, and ASA, and job search writing should be highly useful to grad students. Video podcasts are also available, as well as materials in Spanish .

Created through the joint effort of Harvard University and MIT, edX is a vast MOOC storehouse of resources provided by over 140 partner universities from all over the world. For graduate students looking to augment their learning, edX has more than 2500 courses and programs on almost all types of subjects you can think of – from liberal arts to humanities to the sciences, to even law and medicine.

Assignments and quizzes are also available to track one’s progress and learning. Many of the courses are free, while some grant certificates and even micro master’s degrees.

EBSCO Open Dissertation Database

The EBSCO Open Dissertation Database is an excellent aid for graduate students looking for research trends in their respective fields and significant and verifiable references for their theses or dissertations.

The database is home to almost 200,000 academic papers from universities across the country and more than a million papers from around the world, with publishing dates spanning the early 1900s to the present. Searches can be filtered by university and publishing date, and full texts of the theses and dissertations can be freely accessed.

MIT Open Learning Library

The MIT Open Learning Library is a select collection that combines the best of MIT OCW and MITx. An account is required to access a variety of free resources, which include video and audio lectures, podcasts, lecture notes, problem sets, and answers. Materials marked as OCW content can be freely downloaded and shared.

While no live feedback or discussion is provided, as well as certifications – similar to MIT OCW – auto-graded problem sets and other coursework will help graduate students monitor their progress. Course offerings include aeronautics and STEM topics, particularly engineering, management, history, linguistics, media writing, and urban planning .

Google Scholar

Google Scholar houses a massive collection of academic literature, both old and current. Grad students can use this to search for papers from hundreds of renowned journal publications from both ends of the scholastic spectrum. The portal also has information about the author(s), related literature, and citations.

To enhance the search results with reliable, valid, and substantial sources, Google ranks the materials based on their content, the place and date of publication, the author, and the frequency by which other authors cited it.

Another popular MOOC site, Coursera has partnerships with more than 200 schools and companies worldwide. It houses a whole library of free courses, which, aside from lectures, also include assignments and discussion boards.

For grad students who would want to earn specializations and professional and Master Track certificates (a one-semester course that can be carried over to a full master’s program), they can obtain these for a modest fee.

Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC)

A project of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) of the Department of Education, ERIC , or the Education Resources Information Center is another great resource.

Through its partnerships with various organizations and publications worldwide, ERIC can store more than 1.5 million journal and non-journal materials that can be accessed by anyone and anytime, free of charge. Books, reports, policy documents, and other relevant scholastic work can also be found here.

Harvard Extension School

Harvard Extension School is home to Harvard’s open learning portal. It offers a good number of free courses, which include Abstract Algebra, Greek History, American Poetry, Introduction to Computer Science, World Literature, Culinary Science, Probability Models, US Education Policy, and more.

The site also offers about 800 online courses where credits can be earned for modest fees. Application and registration are not required for both the free and paid courses.

Duke Options

A tool specially designed for Ph.D. students with their professional development in mind, Duke Options allows doctoral candidates to create a roadmap on how to better craft their grad school journey on their way to building a professional career. Students can choose their target competency and stage or current academic level and customize the planned activities from here.

The portal has link suggestions matching the activities on the roadmap, which are also based on the student’s profile and career objectives. While anyone can access Duke Options, only those with NetID credentials can save their roadmaps and plans.

RefSeek is a search engine dedicated to academic materials, literature, and references, such as the website’s name. It has been around since 2008 and works pretty much like a Google search page.

The difference is that the results are more streamlined to show only academic and educational materials instead of manually weeding through the generic list that a standard search engine would have shown, thus saving one’s time. An option also exists for users to choose between all relevant results or to show only documents, which are usually in PDF format.

Carnegie Mellon University Open Learning Initiative (OLI)

Created in partnership with online curriculum site Lumen Learning, the Open Learning Initiative of Carnegie Mellon University offers both free and paid courses in various learning paths, from STEM tracks, which also includes specialized courses like electric car technology and other sustainable energy courses, to linguistics, to public policy, and many more.

There are separate offerings for independent learners or self-learners and those with the OLI Course Key (usually acquired from CMU instructors).

Online resources for Ph.D. students are not just about open courseware; job portals like LinkedIn offer excellent career advice for grad students on how to market their academic achievements and competencies to land that life-changing career.

It also houses – what else – job openings for all career levels, whether you have a bachelor’s or a doctorate, which is usually the next step after attending higher education.

Glassdoor is a comprehensive job market portal that not only posts job openings but also offers insight into the top companies to work for as a master’s or doctorate holder. You might need to sign up for a free account or sign in using your social media accounts to explore and read the resources available here thoroughly.

US Census Bureau

Grad school is all about factual research, and it is better to look than on the US Census Bureau website! Whether you’re looking for past or current figures or statistical trends in health, public policies, population, or the economy, the US census has all these. The bureau conducts more than 130 surveys yearly, all of which are uploaded on the website.

While Udemy is more known to offer paid but affordable online courses that can be taken anytime, anywhere, the site also offers a good number of free resources via video tutorials to complement or augment one’s grad school coursework. Aside from the usual subjects like programming, coding, and languages, Udemy also offers short and free courses.

The list includes personal development and productivity, social influence, emotional intelligence, and other soft skills, which could all be useful to master’s or doctoral candidates gearing up for life (back) in the professional world.

LinkedIn Learning

LinkedIn Learning is not precisely a free online learning portal. Still, it does offer a free one-month trial that allows full access to its 15,000-and-counting course catalog and even earns certificates upon completion.

The course offerings include learning paths in Project Management, as well as Design Thinking and Leadership. These courses are seldom offered by other platforms but are among the top in-demand skills companies are looking for today.

Are you an MBA or grad student looking to enhance your resume with in-demand IT skills or gain some familiarity with topics like Data Science, Big Data, Machine Learning, AI, or Blockchain? Udacity offers free courses on these topics!

The site also has free resources on business topics and its confluence with IT concepts, particularly with data science, such as business and marketing analytics, digital marketing, UX design, and many more.

Course Hero

Course Hero offers free courses in the form of lecture notes, study guides, and documents on different course topics like business and economics, STEM, social sciences, and humanities. Each sub-topic is presented boot camp-style with explanations, short videos, infographics, and links to related resources that can also be found within the site.

It also encourages users – educators and grad students – to contribute to the site through material sharing or tutoring for a modest stipend. Course Hero also offers scholarships to deserving students.

Academic Earth

Academic Earth aims to put distance learning at the forefront of higher education through its well-curated collection of learning materials, both created and from renowned universities such as CalTech, MIT, Yale, Stanford, and many more.

The site also features investigative journalism-like short, original elective videos , which could be good references for grad students working on essays or research papers. The videos touch on topics like mathematics, IT, literature, health policy, history, economics, politics, and even modern psychology, with the list being updated regularly.

Khan Academy

Khan Academy is one of the more popular online resources offering free learning materials for all levels of education. Materials include lecture videos, practice assignments, and even test prep materials for grad school exams like the LSAT, GMAT, MCAT, and others.

Each account is provided with a personalized dashboard to personalize one’s learning track by choosing the topics or courses, taking these anywhere at their own time, and tracking their progress. Khan Academy also runs its own YouTube Channel for its video lectures and infographics.

If you’re thinking of going into grad school for your master’s but can’t decide which program is right for you, your degree, and your career objectives, Study.com has an extensive glossary of all the master’s degree programs offered in the country.

It itemizes the programs, the units, and courses required, as well as the job market outlook and prospects. The website also offers a free one-month trial of its online courses and grad school test preps like the GMAT, GRE, etc.

ThoughtCo has been in the online education industry for more than two decades. The site’s content is more article- and insight-based and written by published authors, doctoral fellows, and members of academia.

Go to this site if you’re looking for expert advice on applying to grad school, how to ace that interview, or other tips on how to survive and make the most of your higher education experience.

Online Ph.D. Degrees

As the outbreak forces many students, like doctoral candidates, to switch to online learning, Online Ph.D. Degrees is an excellent resource for grad students looking to see which schools offer the best distance-learning programs.

It has ranked different Ph.D. programs based on online accessibility, cost-effectivity, completion timeframe, and others. It also offers valuable insight into the value – both professional and monetary (cost and ROI) – of earning a master’s and a doctorate, as well as other frequently asked questions about Ph.D. degrees.

CreativeLive

Community-based, innovative, and fresh – this is what CreativeLive is to many of its site visitors, students, and live audiences. Yes, live. Many of the workshops are free and streamed live , with a weekly schedule posted on the site. Lecturers are real experts in their fields, whether in the various facets of the creative arts or business and entrepreneurship.

Classes are curated non-traditionally, meaning there’s no curriculum or learning path. It’s all self-guided – you learn what you want to learn and use it as an adjunct to your current grad coursework.

The Balance Careers

Before you earn your master’s or doctoral degree, it is good practice to see what opportunities lay ahead and what the job market outlook is. The Balance Careers offers insights into these topics and other relevant topics to grad students who will soon join (or will return) to the workforce armed with a graduate degree.

Its content is authored by career experts from various industries and fields who share advice on matters like getting into grad school and the program of your choice or leveraging your new degree to field competitive job offers to lead to a growing career.

Open Yale Courses

Open Yale Courses (OYC) is Yale University’s free online repository of select courses whose lectures were recorded directly from the classroom. Aside from video formats, the lectures are also available in audio and written (transcript) formats as well.

Courses include introductory lectures to a wide array of subjects like American Studies, Biomedical Engineering, Economics, Linguistics, Philosophy, Political Science, and many more – a good refresher for newly enrolled grad students.

Wolfram Alpha

Wolfram Alpha is a free online resource for all your computational needs, whether it’s for differential calculus, computational sciences like algorithms, or demographic statistics. Grad students pursuing MBAs or master’s and doctorates in STEM courses will find this useful. It even has an expanded calculator with all the mathematical symbols and constants for the calculations.

Saylor Academy

Saylor Academy advocates open and accessible education for everyone. Its comprehensive list of free resources at the tertiary and grad school level encompasses various courses from STEM to the humanities, business administration and analytics, and professional development, which includes industry-specific skills and soft skills.

Saylor’s direct partnership with almost 30 universities and its membership with the ACE and the NCCRS allows Saylor students or users to gain college credit, which they can use upon transferring and the eventual completion of their degrees at a lower cost.

Created by Barnes & Noble, SparkNotes makes learning and reading your good old textbook enjoyable. Think of it as an online reviewer. SparkNotes dissects various reading materials of any subject – with literature as its forte, mainly Shakespeare – and lays it out where all the essential details are cohesively presented and not just bombarded or outlined.

It’s like having flashcards or study guides made out for you – it’s not too summarized but not too lengthy, either. You can also cite them as sources since site content is authored by doctoral graduates, book editors, and academics.

Technology, Entertainment, and Design – this is what TED stands for, the non-profit idea-sharing platform that has become very popular for its TED Talks , but it is much more than that. Among its several other initiatives include TED Books, TED-ed, podcasts, TED Institute and Partnerships, and many more.

The TED Institute , in particular, is an excellent resource for grad students as it features a collection of TED Talks in partnership with global companies. They tackle socioeconomic challenges, like pollution , and proffer solutions like sustainability programs .

Such workshops, which bridge the gap between higher learning and the real world, could be useful for theses, dissertations, essays, and other grad school coursework.

If you’re looking for an online resource that will challenge common beliefs and perhaps even your hypothesis – kind of like an antithesis, just to make sure all your bases are covered – Big Think is an excellent resource for these purposes.

It houses videos that are presented in an investigative format and authored by the most impactful industry disruptors and subject matter experts – from social issues and psychology to AI and the dark web and everything in between.

Whether you’re pursuing visual arts or the art and science of business, SkillShare is perfect! Users gain knowledge and hands-on experience in a wide array of specialized skills like creative writing, using Shopify and Adobe to build a website without coding, building your brand, design thinking, Google Analytics, Microsoft BI, writing for children, publishing, and many more.

An account is required to access the video collection, which is mostly free. SkillShare is also available on Google Play and the App Store.

Inside Higher Ed

As a grad student, it’s equally important to know about the latest news and issues affecting the education sector, particularly the tertiary and post-tertiary levels. Inside Higher Ed is an excellent site for all the hard-hitting news circling higher ed.

It also features editorials, podcasts, blogs, data compilations, job postings, and special reports that pose thought-provoking questions and shed light on current educational paradigms.

Microsoft Academic

Perhaps the most intuitive of all the literary search engines on the web now, Microsoft Academic (MA), brings the use of AI and machine learning to the forefront of online education. By using semantic inference, MA’s search results are more contextual and substantial, as the engine is not keyword-based.

It attempts to understand the search inputs; thus, aside from generating the usual hit, MA will also generate searches that it deems relevant to the query. As of writing, it houses more than 240 million publications encompassing more than 700,000 topics. MA houses one of the largest – if not the largest – collections of educational references pertinent to all levels of learning, especially grad school.