You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

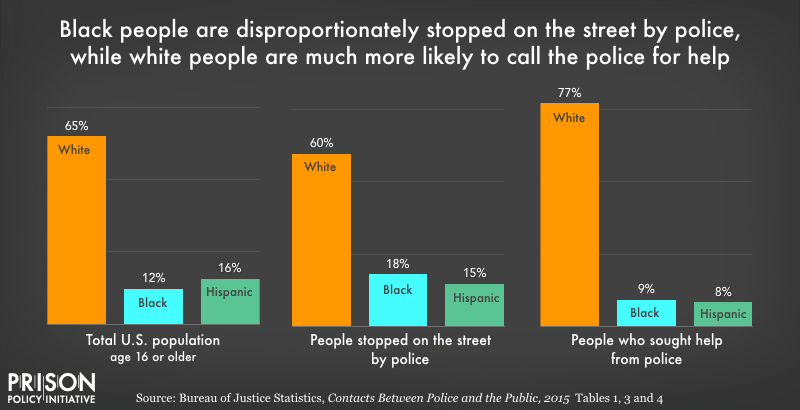

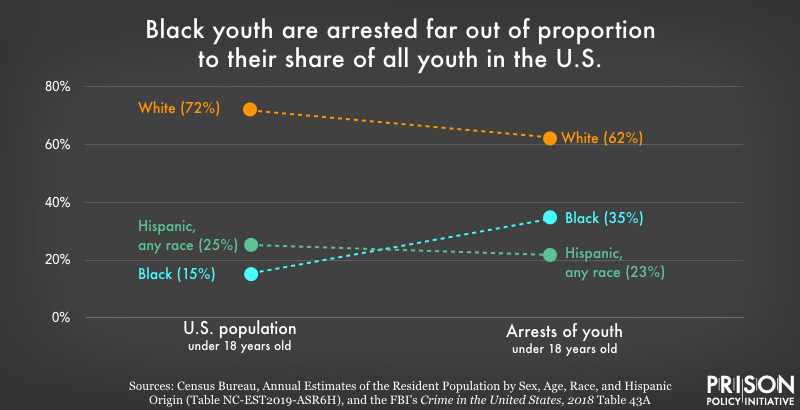

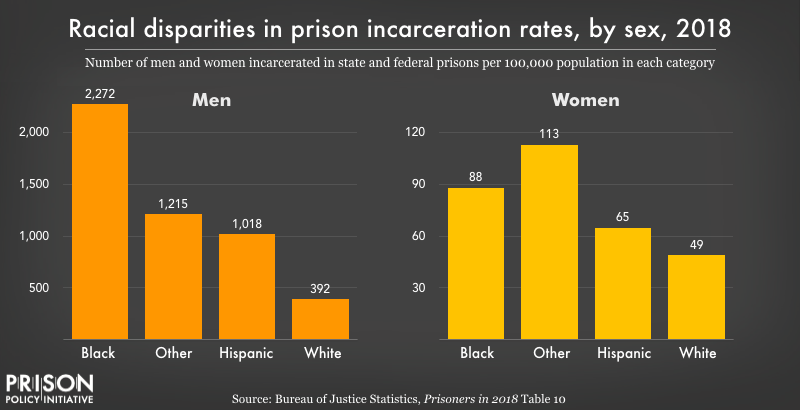

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Analysis & Opinion

Criminal Justice Reform Is More than Fixing Sentencing

Experts explain how we got here and solutions that will benefit everyone.

- Changing Incentives

- Cutting Jail & Prison Populations

A single criminal conviction bars a person for life from calling a bingo game in New York State. Before you chuckle at this gratuitous prohibition, take a second to appreciate the wider context: this is one of 27,000 (!) rules nationwide barring people with criminal records from obtaining a professional license. Conviction of a crime excludes people from holding jobs from real estate appraiser to massage therapist.

In our work to end mass incarceration, the Brennan Center has focused on the length of prison sentences. As our studies have shown, 39 percent of those in prison are there without a current public safety rationale. But the reach of our criminal justice system — its inefficiencies and its unfairness — extends far beyond the time an individual is incarcerated.

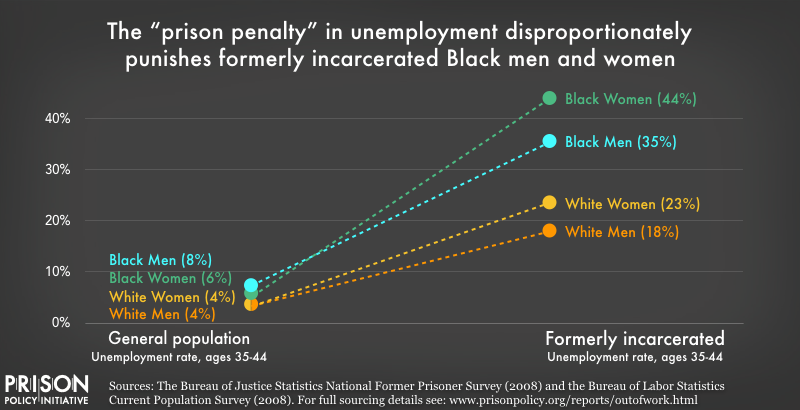

We all have a stake, for example, in making sure that a person leaving prison can reintegrate into society. Instead, we throw up barriers. Getting a job, even one that does not require a professional license, becomes extremely challenging. Studies show that a criminal conviction reduces the likelihood of getting a job callback by 50 percent for a white applicant and nearly two-thirds for a black applicant. These long odds have serious consequences. Finding work is the keystone to getting housing, becoming a contributing family member, and living an independent life.

Since many people are convicted of crimes when young, the negative effects reverberate for decades. The annual reduction in income that accompanies a criminal conviction rises from $7,000 initially to over $20,000 later in life.

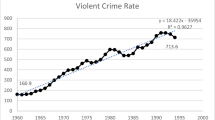

Today crime is rising. Public safety must be a paramount goal. When violence cascades, it affects and hurts poor and marginalized communities most. As Alvin Bragg, the new Manhattan district attorney, put it so well, “The two goals of justice and safety are not opposed to each other. They are inextricably linked.”

Progress toward criminal justice reform was made possible, in part, by the fact that crime rates were falling for decades. Now, rising crime again creates the conditions where demagogic politics and unwise policies can recur — with potentially crushing social, economic, and racial consequences. So we need to think anew, to make sure that the reaction to rising crime does not provoke a policy response that produces neither safety nor fairness.

A year ago, the Brennan Center set out to broaden the national discussion about criminal justice reform. Since then, through our Punitive Excess series , we have published 25 essays by diverse authors ranging from scholars to formerly incarcerated people. The ill-considered collateral consequences of criminal conviction is just one of many topics, which also include perverse financial incentives in the system, inhumane prison conditions, racism, the treatment of child offenders, and more.

It is a trove of analysis and scholarship that deserves your attention. Today we published the concluding essay , which surveys the damage from heavy-handed tactics and offers alternatives that empower communities. We also released a new video exploring the problems caused by excessive punishment. I hope you will read, view, and share widely.

Related Issues:

- Cutting Jail & Prison Populations

How Profit Shapes the Bail Bond System

The for-profit bail bond industry is an overlooked but significant factor in pushback against attempts to reform or end the cash bail system.

DeSantis’s Suspension of Orlando-Area Prosecutor Is Counterproductive Justice Policy

State Attorney Monique Worrell was elected running on evidence-based reforms.

America's Dystopian Incarceration System of Pay to Stay Behind Bars

To reduce unnecessary incarceration, focus on public safety and prison reduction, a new idea on justice reform, the federal government must incentivize states to incarcerate fewer people, criminal justice reform halfway through the biden administration, informed citizens are democracy’s best defense.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

How to Think about Criminal Justice Reform: Conceptual and Practical Considerations

Charis e. kubrin.

Social Ecology II, University of California, Room 3309, Irvine, CA 92697-7080 USA

Rebecca Tublitz

How can we improve the effectiveness of criminal justice reform efforts? Effective reform hinges on shared understandings of what the problem is and shared visions of what success looks like. But consensus is hard to come by, and there has long been a distinction between “policy talk” or how problems are defined and solutions are promoted, and “policy action” or the design and adoption of certain policies. In this essay, we seek to promote productive thinking and talking about, as well as designing of, effective and sustainable criminal justice reforms. To this end, we offer reflections on underlying conceptual and practical considerations relevant for both criminal justice policy talk and action.

Across the political spectrum in the United States, there is agreement that incarceration and punitive sanctions cannot be the sole solution to crime. After decades of criminal justice expansion, incarceration rates peaked between 2006 and 2008 and have dropped modestly, but consistently, ever since then (Gramlich, 2021 ). Calls to ratchet up criminal penalties to control crime, with some exceptions, are increasingly rare. Rather, where bitter partisanship divides conservatives and progressives on virtually every other issue, bipartisan support for criminal justice reform is commonplace. This support has yielded many changes in recent years: scaling back of mandatory sentencing laws, limiting sentencing enhancements, expanding access to non-prison alternatives for low-level drug and property crimes, reducing revocations of community supervision, and increasing early release options (Subramanian & Delaney, 2014 ). New laws passed to reduce incarceration have outpaced punitive legislation three-to-one (Beckett et al., 2016 , 2018 ). Rather than the rigid “law and order” narrative that characterized the dominant approach to crime and punishment since the Nixon administration, policymakers and advocates have found common ground in reform conversations focused on cost savings, evidence-based practice, and being “smart on crime.” A “new sensibility” prevails (Phelps, 2016 ).

Transforming extensive support for criminal justice reform into substantial reductions in justice-involved populations has proven more difficult, and irregular. While the number of individuals incarcerated across the nation has declined, the U.S. continues to have the highest incarceration rate in the world, with nearly 1.9 million people held in state and federal prisons, local jails, and detention centers (Sawyer & Wagner, 2022 ; Widra & Herring, 2021 ). Another 3.9 million people remain on probation or parole (Kaeble, 2021 ). And, not all jurisdictions have bought into this new sensibility: rural and suburban reliance on prisons has increased during this new era of justice reform (Kang-Brown & Subramanian, 2017 ). Despite extensive talk of reform, achieving actual results “is about as easy as bending granite” (Petersilia, 2016 :9).

How can we improve the effectiveness of criminal justice reform? At its core, a reform is an effort to ameliorate an undesirable condition, eliminate an identified problem, achieve a goal, or strengthen an existing (successful) policy. Scholarship yields real insights into effective programming and practice in response to a range of issues in criminal justice. Equally apparent, however, is the lack of criminological knowledge incorporated into the policymaking process. Thoughtful are proposals to improve the policy-relevance of criminological knowledge and increase communication between research and policy communities (e.g., Blomberg et al., 2016 ; Mears, 2022 ). But identifying what drives effective criminal justice reform is not so straightforward. For one, the goals of reform vary across stakeholders: Should reform reduce crime and victimization? Focus on recidivism? Increase community health and wellbeing? Ensure fairness in criminal justice procedure? Depending upon who is asked, the answer differs. Consensus on effective reform hinges on shared understandings of what the problem is and shared visions of what success looks like. Scholars of the policy process often distinguish “policy talk,” or how problems are defined and solutions are promoted, from “policy action,” or the design and adoption of policy solutions, to better understand the drivers of reform and its consequences. This distinction is relevant to criminal justice reform (Bartos & Kubrin, 2018 :2; Tyack & Cuban, 1995 ).

We argue that an effective approach to criminal justice reform—one that results in policy action that matches policy talk—requires clarity regarding normative views about the purpose of punishment, appreciation of practical realities involved in policymaking, and insight into how the two intersect. To this end, in this essay we offer critical reflections on underlying conceptual and practical considerations that bear on criminal justice policy talk and action.

Part I. Conceptual Considerations: Narratives of Crime and Criminal Justice

According to social constructionist theory, the creation of knowledge is rooted in interactions between individuals through common language and shared meanings in social contexts (Berger & Luckmann, 1966 ). Common language and shared meanings create ways of thinking, or narratives, that socially construct our reality and profoundly influence public definitions of groups, events, and social phenomena, including crime and criminal justice. As such, any productive conversation about reform must engage with society’s foundational narratives about crime and criminal justice, including views about the rationales for punishment.

I. Rationales of Punishment

What is criminal justice? What purpose does our criminal justice system serve? Answers to these questions are found in the theories, organization, and practices of criminal justice. A starting point for discovery is the fact that criminal justice is a system for the implementation of punishment (Cullen & Gilbert, 1982 ). This has not always been the case but today, punishment is largely meted out in our correctional system, or prisons and jails, which embody rationales for punishment including retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and restoration. These rationales offer competing purposes and goals, and provide varying blueprints for how our criminal justice system should operate.

Where do these rationales come from? They derive, in part, from diverse understandings and explanations about the causes of crime. While many theories exist, a useful approach for thinking about crime and its causes is found in the two schools of criminological thought, the Classical and Positivist Schools of Criminology. These Schools reflect distinct ideological assumptions, identify competing rationales for punishment, and suggest unique social policies to address crime—all central to any discussion of criminal justice reform.

At its core, the Classical School sought to bring about reform of the criminal justice systems of eighteenth century Europe, which were characterized by such abuses as torture, presumption of guilt before trial, and arbitrary court procedures. Reformers of the Classical School, most notably Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, were influenced by social contract theorists of the Enlightenment, a cultural movement of intellectuals in late seventeenth and eighteenth century Europe that emphasized reason and individualism rather than tradition, along with equality. Central assumptions of the Classical School include that people are rational and possessed of free will, and thus can be held responsible for their actions; that humans are governed by the principle of utility and, as such, seek pleasure or happiness and avoid pain; and that, to prevent crime, punishments should be just severe enough such that the pain or unhappiness created by the punishment outweighs any pleasure or happiness derived from crime, thereby deterring would-be-offenders who will see that “crime does not pay.”

The guiding concept of the Positivist School was the application of the scientific method to study crime and criminals. In contrast to the Classical School’s focus on rational decision-making, the Positivist School adopted a deterministic viewpoint, which suggests that crime is determined by factors largely outside the control of individuals, be they biological (such as genetics), psychological (such as personality disorder), or sociological (such as poverty). Positivists also promote the idea of multiple-factor causation, or that crime is caused by a constellation of complex forces.

When it comes to how we might productively think about reform, a solid understanding of these schools is necessary because “…the unique sets of assumptions of two predominant schools of criminological thought give rise to vastly different explanations of and prescriptions for the problem of crime” (Cullen & Gilbert, 1982 :36). In other words, the two schools of thought translate into different strategies for policy. They generate rationales for punishment that offer competing narratives regarding how society should handle those who violate the law. These rationales for punishment motivate reformers, whether the aim is to “rehabilitate offenders” or “get tough on crime,” influencing policy and practice.

The earliest rationale for punishment is retribution. Consistent with an individual’s desire for revenge, the aim is that offenders experience an unpleasant consequence for violating the law. Essentially, criminals should get what they deserve. While other rationales focus on changing future behavior, retribution focuses on an individual’s past actions and implies they have rightfully “earned” their punishment. Punishment, then, expresses moral disapproval for the criminal act committed. Advocates of retribution are not concerned with controlling crime; rather, they are in the business of “doing justice.” The death penalty and sentencing guidelines, a system of recommended sentences based upon offense (e.g., level of seriousness) and offender (e.g., number and type of prior offenses) characteristics, reflect basic principles of retribution.

Among the most popular rationales for punishment is deterrence, which refers to the idea that those considering crime will refrain from doing so out of a fear of punishment, consistent with the Classical School. Deterrence emphasizes that punishing a person also sends a message to others about what they can expect if they, too, violate the law. Deterrence theory provides the basis for a particular kind of correctional system that punishes the crime, not the criminal. Punishments are to be fixed tightly to specific crimes so that offenders will soon learn that the state means business. The death penalty is an example of a policy based on deterrence (as is obvious, these rationales are not mutually exclusive) as are three-strikes laws, which significantly increase prison sentences of those convicted of a felony who have been previously convicted of two or more violent crimes or serious felonies.

Another rationale for punishment, incapacitation, has the goal of reducing crime by incarcerating offenders or otherwise restricting their liberty (e.g., community supervision reflected in probation, parole, electronic monitoring). Uninterested in why individuals commit crime in the first place, and with no illusion they can be reformed, the goal is to remove individuals from society during a period in which they are expected to reoffend. Habitual offender laws, which target repeat offenders or career criminals and provide for enhanced or exemplary punishments or other sanctions, reflect this rationale.

Embodied in the term “corrections” is the notion that those who commit crime can be reformed, that their behavior can be “corrected.” Rehabilitation refers to when individuals refrain from crime—not out of a fear of punishment—but because they are committed to law-abiding behavior. The goal, from this perspective, is to change the factors that lead individuals to commit crime in the first place, consistent with Positivist School arguments. Unless criminogenic risks are targeted for change, crime will continue. The correctional system should thus be arranged to deliver effective treatment; in other words, prisons must be therapeutic. Reflective of this rationale is the risk-need-responsibility (RNR) model, used to assess and rehabilitate offenders. Based on three principles, the risk principle asserts that criminal behavior can be reliably predicted and that treatment should focus on higher risk offenders, the need principle emphasizes the importance of criminogenic needs in the design and delivery of treatment and, the responsivity principle describes how the treatment should be provided.

When a crime takes place, harm occurs—to the victim, to the community, and even to the offender. Traditional rationales of punishment do not make rectifying this harm in a systematic way an important goal. Restoration, or restorative justice, a relatively newer rationale, aims to rectify harms and restore injured parties, perhaps by apologizing and providing restitution to the victim or by doing service for the community. In exchange, the person who violated the law is (ideally) forgiven and accepted back into the community as a full-fledged member. Programs associated with restorative justice are mediation and conflict-resolution programs, family group conferences, victim-impact panels, victim–offender mediation, circle sentencing, and community reparative boards.

II. Narratives of Criminal Justice

Rationales for punishment, thus, are many. But from where do they arise? They reflect and reinforce narratives of crime and criminal justice (Garland, 1991 ). Penological and philosophical narratives constitute two traditional ways of thinking about criminal justice. In the former, punishment is viewed essentially as a technique of crime control. This narrative views the criminal justice system in instrumental terms, as an institution whose overriding purpose is the management and control of crime. The focal question of interest is a technical one: What works to control crime? The latter, and second, narrative considers the philosophy of punishment. It examines the normative foundations on which the corrections system rests. Here, punishment is set up as a distinctively moral problem, asking how penal sanctions can be justified, what their proper objectives should be, and under what circumstances they can be reasonably imposed. The central question here is “What is just?”.

A third narrative, “the sociology of punishment,” conceptualizes punishment as a social institution—one that is distinctively focused on punishment’s social forms, functions, and significance in society (Garland, 1991 ). In this narrative, punishment, and the criminal justice system more broadly, is understood as a cultural and historical artifact that is concerned with the control of crime, but that is shaped by an ensemble of social forces and has significance and impacts that reach well beyond the population of criminals (pg. 119). A sociology of punishment narrative raises important questions: How do specific penal measures come into existence?; What social functions does punishment perform?; How do correctional institutions relate to other institutions?; How do they contribute to social order or to state power or to class domination or to cultural reproduction of society?; What are punishment’s unintended social effects, its functional failures, and its wider social costs? (pg. 119). Answers to these questions are found in the sociological perspectives on punishment, most notably those by Durkheim (punishment is a moral process, functioning to preserve shared values and normative conventions on which social life is based), Marx (punishment is a repressive instrument of class domination), Foucault (punishment is one part of an extensive network of “normalizing” practices in society that also includes school, family, and work), and Elias (punishment reflects a civilizing process that brings with it a move toward the privatization of disturbing events), among others.

Consistent with the sociology of punishment, Kraska and Brent ( 2011 ) offer additional narratives, which they call theoretical orientations, for organizing thoughts on the criminal justice system generally, and the control of crime specifically. They argue a useful way to think about theorizing is through the use of metaphors. Adopting this approach, they identify eight ways of thinking based on different metaphors: criminal justice as rational/legalism, as a system, as crime control vs. due process, as politics, as the social construction of reality, as a growth complex, as oppression, and as modernity. Several overlap with concepts and frameworks discussed earlier, while others, such as oppression, are increasingly applicable in current conversations about racial justice—something we take up in greater detail below. Consistent with Garland ( 1991 ), Kraska and Brent ( 2011 ) emphasize that each narrative tells a unique story about the history, growth, behaviors, motivations, functioning, and possible future of the criminal justice system. What unites these approaches is their shared interest in understanding punishment’s broader role in society.

There are still other narratives of crime and criminal justice, with implications for thinking about and conceptualizing reform. Packer ( 1964 ) identifies two theoretical models, each offering a different narrative, which reflect value systems competing for priority in the operation of the criminal process: the Crime Control Model and the Due Process Model. The Crime Control Model is based on the view that the most important function of the criminal process is the repression of criminal conduct. The failure of law enforcement to bring criminal conduct under tight control is seen as leading to a breakdown of public order and hence, to the disappearance of freedom. If laws go unenforced and offenders perceive there is a low chance of being apprehended and convicted, a disregard for legal controls will develop and law-abiding citizens are likely to experience increased victimization. In this way, the criminal justice process is a guarantor of social freedom.

To achieve this high purpose, the Crime Control Model requires attention be paid to the efficiency with which the system operates to screen suspects, determine guilt, and secure dispositions of individuals convicted of crime. There is thus a premium on speed and finality. Speed, in turn, depends on informality, while finality depends on minimizing occasions for challenge. As such, the process cannot be “cluttered up” with ceremonious rituals. In this way, informal operations are preferred to formal ones, and routine, stereotyped procedures are essential to handle large caseloads. Packer likens the Crime Control Model to an “assembly line or a conveyor belt down which moves an endless stream of cases, never stopping, carrying the cases to workers who stand at fixed stations and who perform on each case as it comes by the same small but essential operation that brings it one step closer to being a finished product, or, to exchange the metaphor for the reality, a closed file” (pg. 11). Evidence of this model today is witnessed in the extremely high rate of criminal cases disposed of via plea bargaining.

In contrast, the Due Process model calls for strict adherence to the Constitution and a focus on the accused and their Constitutional rights. Stressing the possibility of error, this model emphasizes the need to protect procedural rights even if this prevents the system from operating with maximum efficiency. There is thus a rejection of informal fact-finding processes and insistence on formal, adjudicative, adversary fact-finding processes. Packer likens the Due Process model to an obstacle course: “Each of its successive stages is designed to present formidable impediments to carrying the accused any further along in the process” (pg. 13). That all death penalty cases are subject to appeal, even when not desired by the offender, is evidence of the Due Process model in action.

Like the frameworks described earlier, the Crime Control and Due Process models offer a useful framework for discussing and debating the operation of a system whose day-to-day functioning involves a constant tension between competing demands of different sets of values. In the context of reform, these models encourage us to consider critical questions: On a spectrum between the extremes represented by the two models, where do our present practices fall? What appears to be the direction of foreseeable trends along this spectrum? Where on the spectrum should we aim to be? In essence, which value system is reflected most in criminal justice practices today, in which direction is the system headed, and where should it aim go in the future? Of course this framework, as all others reviewed here, assumes a tight fit between structure and function in the criminal courts yet some challenge this assumption arguing, instead, that criminal justice is best conceived of as a “loosely coupled system” (Hagan et al., 1979 :508; see also Bernard et al., 2005 ).

III. The Relevance of Crime and Criminal Justice Narratives for Thinking about Reform

When it comes to guiding researchers and policymakers to think productively about criminal justice reform, at first glance the discussion above may appear too academic and intellectual. But these narratives are more than simply fodder for discussion or topics of debate in the classroom or among academics. They govern how we think and talk about criminal justice and, by extension, how the system should be structured—and reformed.

An illustrative example of this is offered in Haney’s ( 1982 ) essay on psychological individualism. Adopting the premise that legal rules, doctrines, and procedures, including those of the criminal justice system, reflect basic assumptions about human nature, Haney’s thesis is that in nineteenth century America, an overarching narrative dominated legal and social conceptions of human behavior—that of psychological individualism. Psychological individualism incorporates three basic “facts” about human behavior: 1) individuals are the causal locus of behavior; 2) socially problematic and illegal behavior therefore arises from some defect in the individual persons who perform it; and, 3) such behavior can be changed or eliminated only by effecting changes in the nature or characteristics of those persons. Here, crime is rooted in the nature of criminals themselves be the source genetic, biological, or instinctual, ideas consistent with the Classical School of Criminology.

Haney reviews the rise and supremacy of psychological individualism in American society, discusses its entrenchment in legal responses to crime, and describes the implications of adopting such a viewpoint. Psychological individualism, he claims, diverted attention away from the structural and situational causes of crime (e.g., poverty, inequality, capitalism) and suggested the futility of social reforms that sought solutions to human problems through changes in larger social conditions: “The legal system, in harmony with widely held psychological theories about the causal primacy of individuals, acted to transform all structural problems into matters of moral depravity and personal shortcoming” (pg. 226–27). This process of transformation is nowhere clearer than in our historical commitment to prisons as the solution to the problem of crime, a commitment that continues today. Psychological individualism continues to underpin contemporary reform efforts. For example, approaches to reducing racial disparities in policing by eliminating officers’ unconscious racial bias through implicit-bias trainings shifts the focus away from organizational and institutional sources of disparate treatment.

In sum, the various narratives of crime and criminal justice constitute an essential starting point for any discussion of reform. They reflect vastly differing assumptions and, in many instances, value orientations or ideologies. The diversity of ways of thinking arguably contribute to conflict in society over contemporary criminal justice policy and proposed reforms. Appreciating that point is critical for identifying ways to create effective and sustainable reforms.

At the same time, these different ways of thinking do not exist in a vacuum. Rather, they collide with practical realities and constraints, which can and do shape how the criminal justice system functions, as well as determine the ability to reform it moving forward. For that reason, we turn to a discussion of how narratives about crime and criminal justice intersect with practical realities in the policy sphere, and suggest considerations that policymakers, researchers, and larger audiences should attend to when thinking about the future of reform.

Part II. Practical Considerations: Criminal Justice Reform through a Policy Lens

Criminal justice reform is no simple matter. Unsurprisingly, crime has long been considered an example of a “wicked” problem in public policy: ill-defined; with uncertainty about its causes and incomplete knowledge of effective solutions; complex arrangements of institutions responsible for addressing the problem; and, disagreement on foundational values (Head & Alford, 2015 ; Rittel & Webber, 1973 )—the latter apparent from the discussion above. Many note a large gap between criminological knowledge and policy (Mears, 2010 , 2022 ; Currie, 2007 ). While a movement to incorporate research evidence into the policy-making process has made some in-roads, we know less about how policymakers use this information to adopt and enact reforms. Put differently, more attention is paid to understanding the outcomes of crime-related policy while less is known about the contexts of, and inputs into, the process itself (Ismaili, 2006 ).

We identify practical considerations for policy-oriented researchers and policymakers in thinking through how to make criminal justice reform more effective. Specifically, we discuss practical considerations that reformers are likely to encounter related to problem formulation and framing (policy talk) and policy adoption (policy action), including issues of 1) variation and complexity in the criminal justice policy environment, 2) problem framing and policy content, 3) policy aims and outcomes, 4) equity considerations in policy design and evaluation; and, 5) policy process and policy change. These considerations are by no means exhaustive nor are they mutually exclusive. We offer these thoughts as starting points for discussion.

I. The Criminal Justice Policy Environment: Many Systems, Many Players

The criminal justice “system” in the United States is something of a misnomer. There is no single, centralized system. Instead, there are at least 51 separate systems—one for each of the 50 states, and the federal criminal justice system—each with different laws, policies, and administrative arrangements. Multiple agencies are responsible for various aspects of enforcing the law and administering justice. These agencies operate across multiple, overlapping jurisdictions. Some are at the municipal level (police), others are governed by counties (courts, prosecution, jails), and still others by state and federal agencies (prisons, probation, parole). Across these systems is an enormous amount of discretion regarding what crimes to prioritize for enforcement, whether and what charges to file, which sentences to mete out, what types of conditions, treatment, and programming to impose, and how to manage those under correctional authority. Scholars note the intrinsic problem with this wide-ranging independence: “criminal justice policy is made and put into action at the municipal, county, state, and national levels, and the thousands of organizations that comprise this criminal justice network are, for the most part, relatively autonomous both horizontally and vertically” (Lynch, 2011 :682; see also Bernard et al., 2005 ; Mears, 2017 ).

Criminal justice officials are not the only players. The “policy community” is made up of other governmental actors, including elected and appointed officials in the executive branches (governors and mayors) and legislative actors (council members, state, and federal representatives), responsible for formulating and executing legislation. Non-governmental actors play a role in the policy community as well, including private institutions and non-profit organizations, the media, interest and advocacy groups, academics and research institutions, impacted communities, along with the public at large (Ismaili, 2006 ).

Any consideration of criminal justice reform must attend to the structural features of the policy environment, including its institutional fragmentation. This feature creates both obstacles and opportunities for reform. Policy environments vary tremendously across states and local communities. Policies championed in Washington State are likely different than those championed in Georgia. But the policy community in Atlanta may be decidedly different than that of Macon, and policy changes can happen at hyper-local levels (Ouss & Stevenson, 2022 ). Differences between local jurisdictions can have national impacts: while urban jurisdictions have reduced their reliance on jails and prisons, rural and suburban incarceration rates continue to increase (Kang-Brown & Subramanian, 2017 ). Understanding key stakeholders, their political and policy interests, and their administrative authority to act is critical for determining how effective policy reforms can be pursued (Miller, 2008 ; Page, 2011 ). Prospects for, and possible targets of, reform thus necessitate a wide view of what constitutes “policy,” 1 looking not only to federal and state law but also to state and local administrative policies and practices (Reiter & Chesnut, 2018 ).

II. Policy Talk: Framing Problems, Shaping Possible Solutions

While agreement exists around the need for reform in the criminal justice system, this apparent unanimity belies disagreements over the proposed causes of the problem and feasible solutions (Gottschalk, 2015 ; Levin, 2018 ). This is evident in how reform is talked about in political and policy spheres, the types of reforms pursued, and which groups are its beneficiaries. Since the Great Recession of 2008, bipartisan reforms have often been couched in the language of fiscal conservatism, “right-sizing” the system, and being “smart on crime” (Beckett et al., 2016 ). These economic frames, focused on cost-efficiency, are effectively used to defend non-punitive policies including changes to the death penalty, marijuana legalization, and prison down-sizing (Aviram, 2015 ). However, cost-saving rationales are also used to advance punitive policies that shift the costs of punishment onto those who are being sanctioned, such as “pay-to-stay” jails and the multitude of fines and fees levied on justice-involved people for the cost of criminal justice administration. Economic justifications are not the only arguments that support the very same policy changes; fairness and proportionality, reducing prison overcrowding, enhancing public safety, and increasing rehabilitation are all deployed to defend various reforms (Beckett et al., 2016 ). Similarity in rhetorical justifications—cost-efficiency and fiscal responsibility, for example—can obscure deep divisions over how, and whom, to punish, divisions which stem from different narratives on the causes and consequences of crime.

The content of enacted policies also reveals underlying disagreements within justice reform. Clear distinctions are seen in how cases and people are categorized, and in who benefits from, or is burdened by, reform. For example, many states have lowered penalties and expanded rehabilitation alternatives for non-violent drug and other low-level offenses and technical violations on parole. Substantially fewer reforms target violent offenses. Decarceration efforts for non-violent offenders are often coupled with increasing penalties for others, including expansions of life imprisonment without parole for violent offenses (Beckett, 2018 ; Seeds, 2017 ). Reforms aimed only at individuals characterized as “non-violent, non-serious, and non-sexual” can reinforce social distinctions between people (and offenses) seen as deserving of lenient treatment from those who aren’t (Beckett et al., 2016 ).

The framing of social problems can shape the nature of solutions, although the impact of “framing” deserves greater attention in the criminal justice policy process (Rein & Schön, 1977 ; Schneider & Ingram, 1993 ). Policies can be understood in rational terms—for their application of technical solutions to resolve pre-defined problems—but also through “value-laden components, such as social constructions, rationales, and underlying assumptions” (Schneider & Sidney, 2006 :105). Specific frames (e.g., “crime doesn’t pay” or “don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time”) derive from underlying narratives (e.g., classical school, rational-actor models of behavior, and deterrence) that shape how crime and criminal justice are understood, as discussed in Part I. Framing involves how issues are portrayed and categorized, and even small changes to language or images used to frame an issue can impact policy preferences (Chong & Druckman, 2007 ). Public sentiments play an important role in the policy process, as policymakers and elected officials are responsive to public opinion about punishments (Pickett, 2019 ). Actors in the policy community—criminal justice bureaucrats, elected officials, interest groups, activists—compete to influence how a problem is framed, and thus addressed, by policymakers (Baumgartner & Jones, 2009 ; Benford & Snow, 2000 ). Policymakers, particularly elected officials, commonly work to frame issues in ways that support their political goals and resonate with their constituents (Gamson, 1992 ).

As noted at the outset, public support for harsh punishments has declined since the 1990’s and the salience of punitive “law and order” and “tough-on-crime” politics has fallen as well, as public support for rehabilitative approaches has increased (Thielo et al., 2016 ). How can researchers and policymakers capitalize on this shift in public sentiments? Research suggests that different issue frames, such as fairness, cost to taxpayers, ineffectiveness, and racial disparities, can increase (or reduce) public support for policies for nonviolent offenders (e.g., Dunbar, 2022 ; Gottlieb, 2017 ) and even for policies that target violent offenders (Pickett et al., 2022 ). Public sentiment and framing clearly matter for what problems gain attention, the types of policies that exist, and who ultimately benefits. These themes raise orienting questions: In a specific locale, what are the dominant understandings of the policy problem? How do these understandings map to sets of foundational assumptions about the purpose of intervention (e.g., deterrence, retribution, rehabilitation, restoration) and understandings of why people commit crime (e.g., Classical and Positivist approaches)? What types of issue frames are effective in garnering support for reforms? How does this support vary by policy context (urban, suburban, rural; federal, statewide, and local) and audience (elected officials, agency leadership, frontline workers, political constituents)?

III. Proposed Solutions and Expected Outcomes: Instrumental or Symbolic?

There are a variety of motivations in pursuing various policy solutions, along with different kinds of goals. Some reflect a desire to create tangible change for a specific problem while others are meant to mollify a growing concern. As such, one practical consideration related to policymaking and reform that bears discussion is the symbolic and instrumental nature of criminal justice policies.

Policies are considered to have an instrumental nature when they propose or result in changes to behaviors related to a public problem such as crime—that is, when they change behavior through direct influence on individuals’ actions (Sample et al., 2011 :29; see also Grattet & Jenness, 2008 ; Gusfield, 1963 ; Oliver & Marion, 2008 ). Symbolic policies, by contrast, are those that policymakers pass in order to be seen in a favorable light by the public (Jenness, 2004 ), particularly in the context of a “moral panic” (Barak, 1994 ; Ben-Yehuda, 1990 ). As Sample et al., ( 2011 :28) explain, symbolic policies provide three basic functions to society: 1) reassuring the public by helping reduce angst and demonstrate that something is being done about a problem; 2) solidifying moral boundaries by codifying public consensus of right and wrong; and 3) becoming a model for the diffusion of law to other states and the federal government. Symbolic policies are thus meant to demonstrate that policymakers understand, and are willing to address, a perceived problem, even when there is little expectation such policies will make a difference. In this way, symbolic policies are “values statements” and function largely ceremonially.

This distinction has a long history in criminological work, dating back to Gusfield’s ( 1963 ) analysis of the temperance movement. Suggesting that policymaking is often dramatic in nature and intended to shift ways of thinking, Gusfield ( 1963 ) argues that Prohibition and temperance were intended as symbolic, rather than instrumental, goals in that their impacts were felt in the action of prohibition itself rather than in its effect on citizens’ consumptive behaviors.

A modern-day example of symbolic policy is found in the sanctuary status movement as it relates to the policing of immigrants. Historically, immigration enforcement was left to the federal government however state and local law enforcement have faced increasing demands to become more involved in enforcing immigration laws in their communities. Policies enacted to create closer ties between local police departments and federal immigration officials reflect this new pattern of “devolution of immigration enforcement” (Provine et al., 2016 ). The Secure Communities Program, the Criminal Alien Program, and 287g agreements, in different but complementary ways, provide resources and training to help local officials enforce immigration statutes.

The devolution of immigration enforcement has faced widespread scrutiny (Kubrin, 2014 ). Many local jurisdictions have rejected devolution efforts by passing sanctuary policies, which expressly limit local officials’ involvement in the enforcement of federal immigration law. Among the most comprehensive is California’s SB54, passed in 2017, which made California a sanctuary state. The law prohibits local authorities from cooperating with federal immigration detainer requests, limits immigration agents’ access to local jails, and ends the use of jails to hold immigration detainees. At first glance, SB54 appears instrumental—its aim is to change the behavior of criminal justice officials in policing immigration. In practice, however, it appears that little behavioral change has taken place. Local police in California had already minimized their cooperation with Federal officials, well before SB54 was passed. In a broader sense then, “…the ‘sanctuary city’ name is largely a symbolic message of political support for immigrants without legal residency” and with SB54 specifically, “California [helped build] a wall of justice against President Trump’s xenophobic, racist and ignorant immigration policies,” (Ulloa, 2017 ).

Instrumental and symbolic goals are not an either-or proposition. Policies can be both, simultaneously easing public fears, demonstrating legislators’ desire to act, and having direct appreciable effects on people’s behaviors (Sample et al., 2011 ). This may occur even when not intended. At the same time, a policy’s effects or outcomes can turn out to be different from the original aim, creating a gap between “policy talk” and “policy action.” In their analysis of law enforcement action in response to the passage of hate crime legislation, Grattet and Jenness ( 2008 ) find that legislation thought to be largely symbolic in nature, in fact, ended up having instrumental effects through changes in enforcement practices, even as these effects were conditioned by the organizational context of enforcement agencies. Symbolic law can be rendered instrumental (under certain organizational and social conditions) and symbolic policies may evolve to have instrumental effects.

As another example, consider aims and outcomes of sex offender registration laws, which provide information about people convicted of sex offenses to local and federal authorities and the public, including the person’s name, current location, and past offenses. As Sample et al. ( 2011 ) suggest, these laws, often passed immediately following a highly publicized sex crime or in the midst of a moral panic, are largely cast as symbolic policy, serving to reassure the public through notification of sex offenders’ whereabouts so their behaviors can be monitored (Jenkins, 1998 ; Sample & Kadleck, 2008 ). While notification laws do not yield a discernable instrumental effect on offenders’ behavior (Tewksbury, 2002 ), this is not the sole goal of such policies. Rather, they are intended to encourage behavioral change among citizens (Sample et al., 2011 ), encouraging the public’s participation in their own safety by providing access to information. Do sex offender notification laws, in fact, alter citizen behavior, thereby boosting public safety?

To answer this question, Sample and her colleagues ( 2011 ) surveyed a random sample of Nebraska residents to determine whether they access sex offender information and to explore the reasons behind their desire, or reluctance, to do so. They find largely symbolic effects of registry legislation, with a majority of residents (over 69%) indicating they had never accessed the registry. These findings raise important questions about the symbolic vs. instrumental nature of criminal justice policies more broadly: “Should American citizens be content with largely symbolic crime policies and laws that demonstrate policy makers’ willingness to address problems, ease public fear, solidify public consensus of appropriate and inappropriate behavior, and provide a model of policies and laws for other states, or should they want more from crime control efforts? Is there a tipping point at which time the resources expended to adhere to symbolic laws and a point where the financial and human costs of the law become too high to continue to support legislation that is largely symbolic in nature? Who should make this judgment?” (pg. 46). These two examples, immigration-focused laws and sex offender laws, illustrate the dynamics involved in policymaking, particularly the relationship between proposed solutions and their expected outcomes. They reveal that instrumental and symbolic goals often compete for priority in the policy-making arena.

IV. Equity-Consciousness in Policy Formulation

As the criminal justice system exploded in size in the latter half of the twentieth century, its impacts have not spread equally across the population. Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by policing, mass incarceration, and surveillance practices. At a moment of political momentum seeking to curb the excesses of the criminal justice system, careful attention must be paid not only to its overreach, but also to its racialized nature and inequitable impacts. Many evaluative criteria are used to weigh policies including efficiency, effectiveness, cost, political acceptability, and administrative feasibility, among others. One critical dimension is the extent to which a policy incorporates equity considerations into its design, or is ignorant about potential inequitable outcomes. While reducing racial disparities characterizes reform efforts of the past, these efforts often fail to yield meaningful impacts, and sometimes unintentionally exacerbate disparities. Equity analyses should be more formally centered in criminal justice policymaking.

Racial and ethnic disparities are a central feature of the U.S. criminal justice system. Decades of research reveals Black people, and to a lesser degree Latinos and Native Americans, are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system at all stages (Bales & Piquero, 2012 ; Hinton et al., 2018 ; Kutateladze et al., 2014 ; Menefee, 2018 ; Mitchell, 2005 ; Warren et al., 2012 ). These disparities have many sources: associations between blackness and criminality, and stereotypes of dangerousness (Muhammad, 2010 ); implicit racial bias (Spencer et al., 2016 ); residential and economic segregation that expose communities of color to environments that encourage criminal offending and greater police presence (Peterson & Krivo, 2010 ; Sharkey, 2013 ); and, punitive criminal justice policies that increase the certainty and severity of punishments, such as mandatory minimum sentences, life imprisonment, and habitual offender laws, for which people of color are disproportionately arrested and convicted (Raphael & Stoll, 2013 ; Schlesinger, 2011 ). Disparities in initial stages of criminal justice contact, at arrest or prosecution, can compound to generate disparate outcomes at later stages, such as conviction and sentencing, even where legal actors are committed to racial equality (Kutateladze et al., 2014 ). Disparities compound over time, too; having prior contact with the justice system may increase surveillance and the likelihood of being arrested, charged, detained pretrial, and sentenced to incarceration (Ahrens, 2020 ; Kurlychek & Johnson, 2019 ).

Perspectives on how to reduce disparities vary widely, and understanding how the benefits or burdens of a given policy change will be distributed across racial and ethnic groups is not always clear. Even well-intentioned reforms intended to increase fairness and alleviate disparities can fail to achieve intended impacts or unintentionally encourage inequity. For example, sentencing guidelines adopted in the 1970s to increase consistency and reduce inequitable outcomes across groups at sentencing alleviated, but did not eliminate, racial disparities (Johnson & Lee, 2013 ); popular “Ban the Box” legislation, aimed at reducing the stigma of a criminal record, may increase racial disparities in callbacks for job seekers of color (Agan & Starr, 2018 ; Raphael, 2021 ); and “risk assessments,” used widely in criminal justice decision-making, may unintentionally reproduce existing disparities by relying on information that is itself a product of racialized policing, prosecution, and sentencing (Eckhouse et al., 2019 ). Conversely, policies enacted without explicit consideration of equity effects may result in reductions of disparities: California’s Proposition 47, which reclassifies certain felony offenses to misdemeanors, reduced Black and Latino disparities in drug arrests, likelihood of conviction, and rates of jail incarceration relative to Whites (Mooney et al., 2018 ; Lofstrom et al., 2019 ; MacDonald & Raphael, 2020 ).

Understanding the potential equity implications of criminal justice reforms should be a key consideration for policymakers and applied researchers alike. However, an explicit focus on reducing racial disparities is often excluded from the policymaking process, seen as a secondary concern to other policy goals, or framed in ways that focus on race-neutral processes rather than race-equitable outcomes (Chouhy et al., 2021 ; Donnelly, 2017 ). But this need not be the case; examinations of how elements of a given policy (e.g., goals, target population, eligibility criteria) and proposed changes to procedure or practice might impact different groups can be incorporated into policy design and evaluation. As one example, racial equity impact statements (REIS), a policy tool that incorporates an empirical analysis of the projected impacts of a change in law, policy, or practice on racial and ethnic groups (Porter, 2021 ), are used in some states. Modeled after the now-routine environmental impact and fiscal impact statements, racial impact statements may be conducted in advance of a hearing or vote on any proposed change to policy, or can even be incorporated in the policy formulation stages (Chouhy et al., 2021 ; Mauer, 2007 ). Researchers, analysts, and policymakers should also examine potential differential effects of existing policies and pay special attention to how structural inequalities intersect with policy features to contribute to—and potentially mitigate—disparate impacts of justice reforms (Anderson et al., 2022 ; Mooney et al., 2022 ).

V. Putting It Together: Modeling the Policy Change Process

Approaches to crime and punishment do not change overnight. Policy change can be incremental or haphazard, and new innovations adopted by criminal justice systems often bear markers of earlier approaches. There exist multiple frameworks for understanding change and continuity in approaches to crime and punishment. The metaphor of a pendulum is often used to characterize changes to criminal justice policy, where policy regimes swing back and forth between punishment and leniency (Goodman et al., 2017 ). These changes are ushered along by macro-level shifts of economic, political, demographics, and cultural sensibilities (Garland, 2001 ).

Policy change is rarely predictable or mechanical (Smith & Larimer, 2017 ). Actors struggle over whom to punish and how, and changes in the relative resources, political position, and power among actors drive changes to policy and practice (Goodman et al., 2017 ). This conflict, which plays out at the level of politics and policymaking and is sometimes subsumed within agencies and day-to-day practices in the justice system, creates a landscape of contradictory policies, logics, and discourses. New policies and practices are “tinted” by (Dabney et al., 2017 ) or “braided” with older logics (Hutchinson, 2006 ), or “layered” onto existing practices (Rubin, 2016 ).

Public policy theory offers different, but complementary, insights into how policies come to be, particularly under complex conditions. One widely used framework in policy studies is the “multiple streams” framework (Kingdon, 1995 ). This model of the policymaking process focuses on policy choice and agenda setting, or the question of what leads policymakers to pay attention to one issue over others, and pursue one policy in lieu of others.

The policy process is heuristically outlined as a sequential set of steps or stages: problem identification, agenda setting, policy formulation, adoption or decision-making, implementation, and evaluation. However, real-world policymaking rarely conforms to this process (Smith & Larimer, 2017 ). In the multiple streams lens, the process is neither rational nor linear but is seen as “organized anarchy,” described by several features: 1) ambiguity over the definition of the problem, creating many possible solutions for the same circumstances and conditions; 2) limited time to make decisions and multiple issues vying for policymakers’ attention, leading to uncertain policy preferences; 3) a crowded policy community with shifting participation; and, 4) multiple agencies and organizations in the policy environment working on similar problems with little coordination or transparency (Herweg et al., 2018 ).

In this context, opportunity for change emerges when three, largely separate, “streams” of interactions intersect: problems , politics , and policies . First, in the “problem stream,” problems are defined as conditions that deviate from expectations and are seen by the public as requiring government intervention. Many such “problems” exist, but not all rise to the level of attention from policymakers. Conditions must be re-framed into problems requiring government attention. Several factors can usher this transformation. Changes in the scale of problem, such as increases or decreases in crime, can raise the attention of government actors. So-called “focusing events” (Birkland, 1997 ), or rare and unexpected events, such as shocking violent crime or a natural disaster (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic), can also serve this purpose. The murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis, for instance, was a focusing event for changing the national conversation around police use of force into a problem requiring government intervention. Finally, feedback from existing programs or policies, particularly those that fail to achieve their goals or have unwanted effects, can reframe existing conditions as problems worthy of attention.

The “policy stream” is where solutions, or policy alternatives, are developed to address emerging problems. Solutions are generated both by “visible” participants in the stream, such as prominent elected officials, or by “hidden” actors, such as criminal justice bureaucrats, interest groups, academics, or consultants. Policy ideas float around in this stream until they are “coupled,” or linked, with specific problems. At any given time, policy ideas based in deterrence or incapacitation rationales, including increasing the harshness of penalties or the certainty of sanctions, and solutions based in rehabilitative rationales, such as providing treatment-oriented diversion or restorative justice programs, all co-exist in the policy stream. Not all policy alternatives are seen as viable and likely to reach the agenda; viable solutions are marked by concerns of feasibility, value acceptability, public support or tolerance, and financial viability.

Lastly, the “political stream” is governed by several elements, including changes to the national mood and changing composition of governments and legislatures as new politicians are elected and new government administrators appointed. This stream helps determine whether a problem will find a receptive venue (Smith & Larimer, 2017 ). For example, the election of a progressive prosecutor intent on changing status quo processing of cases through the justice system creates a viable political environment for new policies to be linked with problems. When the three streams converge, that is, when conditions become problems, a viable solution is identified, and a receptive political venue exists, a “policy window” opens and change is most likely. For Kingdon ( 2011 ), this is a moment of “opportunity for advocates of proposals to push their pet solutions, or to push attention to their special problems” (pg. 165).

Models of the policy change process, of which the multiple streams framework is just one, may be effectively applied to crime and justice policy spheres. Prior discussions on the ways of thinking about crime and criminal justice can be usefully integrated with models of the policy change process; narratives shape how various conditions are constructed as problems worthy of collective action and influence policy ideas and proposals available among policy communities. We encourage policymakers and policy-oriented researchers to examine criminal justice reform through policy process frameworks in order to better understand why some reforms succeed, and why others fail.

When it comes to the criminal justice system, one of the most commonly asked questions today is: How can we improve the effectiveness of reform efforts? Effective reform hinges on shared understandings of what the problem is as well as shared visions of what success looks like. Yet consensus is hard to come by, and scholars have long differentiated between “policy talk” and “policy action.” The aim of this essay has been to identify conceptual and practical considerations related to both policy talk and policy action in the context of criminal justice reform today.

On the conceptual side, we reviewed narratives that create society’s fundamental ways of thinking about or conceptualizing crime and criminal justice. These narratives reflect value orientations that underlie our criminal justice system and determine how it functions. On the practical side, we identified considerations for both policy-oriented researchers and policymakers in thinking through how to make criminal justice reform more effective. These practical considerations included variation and complexity in the criminal justice policy environment, problem framing and policy content, policy aims and outcomes, equity considerations in policy design and evaluation, and models of the policy change process.

These conceptual and practical considerations are by no means exhaustive, nor are they mutually-exclusive. Rather, they serve as starting points for productively thinking and talking about, as well as designing, effective and sustainable criminal justice reform. At the same time, they point to the need for continuous policy evaluation and monitoring—at all levels—as a way to increase accountability and effectiveness. Indeed, policy talk and policy action do not stop at the problem formation, agenda setting, or adoption stages of policymaking. Critical to understanding effective policy is implementation and evaluation, which create feedback into policy processes, and is something that should be addressed in future work on criminal justice reform.

Biographies

is Professor of Criminology, Law & Society and (by courtesy) Sociology at the University of California, Irvine. Among other topics, her research examines the impact of criminal justice reform on crime rates. Professor Kubrin has received several national awards including the Ruth Shonle Cavan Young Scholar Award from the American Society of Criminology (for outstanding scholarly contributions to the discipline of criminology); the W.E.B. DuBois Award from the Western Society of Criminology (for significant contributions to racial and ethnic issues in the field of criminology); and the Paul Tappan Award from the Western Society of Criminology (for outstanding contributions to the field of criminology). In 2019, she was named a Fellow of the American Society of Criminology.

, M.P.P. is a doctoral student in the Department of Criminology, Law & Society at the University of California, Irvine. Her research explores criminal justice reform, inequality, courts, and corrections. She has over 10 years of experience working with state and local governments to conduct applied research, program evaluation, and technical assistance in criminal justice and corrections. Her work has appeared in the peer-reviewed journals Justice Quarterly and PLOS One.

1 No single definition of public policy exists. Here we follow Smith and Larimer ( 2017 ) and define policy as any action by the government in response to a problem, including laws, rules, agency policies, programs, and day-to-day practices.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Charis E. Kubrin, Email: ude.icu@nirbukc .

Rebecca Tublitz, Email: ude.icu@ztilbutr .

- Agan, A. & Starr, S. (2018) Ban the box criminal records and racial discrimination: A field experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133 (1), 191–235. 10.1093/qje/qjx028

- Ahrens DM. Retroactive legality: Marijuana convictions and restorative justice in an era of criminal justice reform. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 2020; 110 :379. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson CN, Wooldredge J, Cochran JC. Can “race-neutral” program eligibility requirements in criminal justice have disparate effects? An examination of race, ethnicity, and prison industry employment. Criminology & Public Policy. 2022; 21 :405–432. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12576. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aviram H. Cheap on Crime: Recession-era Politics and the Transformation of American Punishment. University of California Press; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bales WD, Piquero AR. Racial/Ethnic differentials in sentencing to incarceration. Justice Quarterly. 2012; 29 :742–773. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2012.659674. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barak G. Media, process, and the social construction of crime. Garland; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartos BJ, Kubrin CE. Can we downsize our prisons and jails without compromising public safety? Findings from California's Prop 47. Criminology & Public Policy. 2018; 17 :693–715. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12378. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baumgartner FR, Jones BD. Agendas and instability in American politics. 2. University of Chicago Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckett, K. (2018). The politics, promise, and peril of criminal justice reform in the context of mass incarceration. Annual Review of Criminology, 1 , 235–259.

- Beckett K, Reosti A, Knaphus E. The end of an era? Understanding the contradictions of criminal justice reform. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2016; 664 :238–259. doi: 10.1177/0002716215598973. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beckett, K., Beach, L., Knaphus, E., & Reosti, A. (2018). US criminal justice policy and practice in the twenty‐first century: Toward the end of mass incarceration?. Law & Policy, 40 (4), 321–345. 10.1111/lapo.12113

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 611–639.

- Ben-Yehuda N. The politics and morality of deviance. State University of New York Press; 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berger PL, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology knowledge. Anchor Books; 1966. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard TJ, Paoline EA, III, Pare PP. General systems theory and criminal justice. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2005; 33 :203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2005.02.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Birkland TA. After disaster: Agenda setting, public policy, and focusing events. Georgetown University Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blomberg T, Brancale J, Beaver K, Bales W. Advancing criminology & criminal justice policy. Routledge; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Currie Elliott. Against marginality. Theoretical Criminology. 2007; 11 (2):175–190. doi: 10.1177/1362480607075846. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chong D, Druckman JN. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science. 2007; 10 :103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chouhy C, Swagar N, Brancale J, Noorman K, Siennick SE, Caswell J, Blomberg TG. Forecasting the racial and ethnic impacts of ‘race-neutral’ legislation through researcher and policymaker partnerships. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12103-021-09619-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cullen, F. T. & Gilbert, K. E. (1982). Criminal justice theories and ideologies. In Reaffirming rehabilitation (pp. 27–44). Andersen.

- Dabney DA, Page J, Topalli V. American bail and the tinting of criminal justice. Howard Journal of Crime and Justice. 2017; 56 :397–418. doi: 10.1111/hojo.12212. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donnelly EA. The politics of racial disparity reform: Racial inequality and criminal justice policymaking in the states. Am J Crim Just. 2017; 42 :1–27. doi: 10.1007/s12103-016-9344-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunbar, A. (2022). Arguing for criminal justice reform: Examining the effects of message framing on policy preferences. Justice Quarterly . 10.1080/07418825.2022.2038243

- Eckhouse L, Lum K, Conti-Cook C, Ciccolini J. Layers of bias: A unified approach for understanding problems with risk assessment. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2019; 46 :185–209. doi: 10.1177/0093854818811379. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gamson WA. Talking politics. Cambridge University Press; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garland D. Sociological Perspectives on Punishment. Crime and Justice. 1991; 14 :115–165. doi: 10.1086/449185. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garland D. The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. University of Chicago Press; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodman P, Page J, Phelps M. Breaking the pendulum: The long struggle over criminal justice. Oxford University Press; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottlieb A. The effect of message frames on public attitudes toward criminal justice reform for nonviolent offenses. Crime & Delinquency. 2017; 63 :636–656. doi: 10.1177/0011128716687758. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottschalk M. Caught: The prison state and the lockdown of American politics. Princeton University Press; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gramlich J. America’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995. Pew Research Center; 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grattet R, Jenness V. Transforming symbolic law into organizational action: Hate crime policy and law enforcement practice. Social Forces. 2008; 87 :501–527. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0122. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gusfield JR. Symbolic crusade: Status politics and the American temperance movement. University of Illinois Press; 1963. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagan J, Hewitt JD, Alwin DF. Ceremonial justice: Crime and punishment in a loosely coupled system. Social Forces. 1979; 58 :506–527. doi: 10.2307/2577603. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haney C. Criminal justice and the nineteenth-century paradigm: The triumph of psychological individualism in the ‘Formative Era’ Law and Human Behavior. 1982; 6 :191–235. doi: 10.1007/BF01044295. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Head BW, Alford J. Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Administration & Society. 2015; 47 :711–739. doi: 10.1177/0095399713481601. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herweg, N., Zahariadis, N., & Zohlnhöfer, R. (2018). The Multiple streams framework: Foundations, refinements, and empirical applications. In Theories of the policy process (pp 17–53). Routledge.

- Hinton E, Henderson L, Reed C. An unjust burden: The disparate treatment of Black Americans in the criminal justice system. Vera Institute of Justice; 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hutchinson S. Countering catastrophic criminology. Punishment & Society. 2006; 8 :443–467. doi: 10.1177/1462474506067567. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ismaili K. Contextualizing the criminal justice policy-making process. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2006; 17 :255–269. doi: 10.1177/0887403405281559. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jenkins P. Moral panic: Changing concepts of the child molester in Modern America. Yale University Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jenness V. Explaining criminalization: From demography and status politics to globalization and modernization. Annual Review of Sociology. 2004; 30 :147–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110515. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson BD, Lee JG. Racial disparity under sentencing guidelines: A survey of recent research and emerging perspectives. Sociology Compass. 2013; 7 :503–514. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12046. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaeble, D. (2021). Probation and parole in the United States, 2020. Bureau of Justice Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice.

- Kang-Brown J, Subramanian R. Out of sight: The growth of jails in rural America. Vera Institute of Justice; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kingdon, J. W. (2011[1995]). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies . Harper Collins.

- Kraska PB, Brent JJ. Theorizing criminal justice: Eight essential orientations. 2. Waveland Press; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kubrin CE. Secure or insecure communities?: Seven reasons to abandon the secure communities program. Criminology & Public Policy. 2014; 13 :323–338. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12086. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurlychek MC, Johnson BD. Cumulative disadvantage in the American Criminal Justice System. Annual Review of Criminology. 2019; 2 :291–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-011518-024815. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kutateladze BL, Andiloro NR, Johnson BD, Spohn CC. Cumulative disadvantage: Examining racial and ethnic disparity in prosecution and sentencing. Criminology. 2014; 52 :514–551. doi: 10.1111/1745-9125.12047. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levin B. The consensus myth in criminal justice reform. Michigan Law Review. 2018; 117 :259. doi: 10.36644/mlr.117.2.consensus. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lofstrom, M., Martin, B., & Raphael, S. (2019). The effect of sentencing reform on racial and ethnic disparities in involvement with the criminal justice system: The case of California's Proposition 47 (University of California, Working Paper).

- Lynch, M. (2011). Mass incarceration legal change and locale. Criminology & Public Policy , 10(3), 673–698. 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00733.x

- MacDonald J, Raphael S. Effect of scaling back punishment on racial and ethnic disparities in criminal case outcomes. Criminology & Public Policy. 2020; 19 :1139–1164. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12495. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mauer M. Racial impact statements as a means of reducing unwarranted sentencing disparities. Ohio State Journal of Crime Law. 2007; 5 (19):33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mears DP. American criminal justice policy: An evaluation approach to increasing accountability and effectiveness. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mears DP. Out-of-control criminal justice: The systems improvement solution for more safety, justice, accountability, and efficiency. Cambridge University Press; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mears, D. P. (2022). Bridging the research-policy divide to advance science and policy: The 2022 Bruce Smith, Sr. award address to the academy of criminal justice sciences. Justice Evaluation Journal , 1–23.

- Menefee MR. The role of bail and pretrial detention in the reproduction of racial inequalities. Sociology Compass. 2018; 12 :e12576. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12576. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller LL. The perils of federalism: Race, poverty, and the politics of crime control. Oxford University Press; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mitchell O. A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: Explaining the inconsistencies. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2005; 21 :439–466. doi: 10.1007/s10940-005-7362-7. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mooney AC, Giannella E, Glymour MM, Neilands TB, Morris MD, Tulsky J, Sudhinaraset M. Racial/ethnic disparities in arrests for drug possession after California proposition 47, 2011–2016. American Journal of Public Health. 2018; 108 :987–993. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304445. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mooney, A. C., Skog, A., & Lerman, A. E. (2022). Racial equity in eligibility for a clean slate under automatic criminal record relief laws. Law and Society Review, 56 (3). 10.1111/lasr.12625

- Muhammad, K. G. (2010). The condemnation of Blackness: Race, crime, and the making of modern urban America . Harvard University Press.

- Oliver WM, Marion NE. Political party platforms: Symbolic politics and criminal justice policy. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2008; 19 :397–413. doi: 10.1177/0887403408318829. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ouss, A., & Stevenson, M. (2022). Does cash bail deter misconduct? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3335138

- Packer H. Two models of the criminal process. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 1964; 113 :1–68. doi: 10.2307/3310562. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Page J. The toughest beat: Politics, punishment, and the prison officers union in California. Oxford University Press; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petersilia J. Realigning corrections, California style. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2016; 664 :8–13. doi: 10.1177/0002716215599932. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peterson RD, Krivo LJ. Divergent social worlds: Neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Phelps MS. Possibilities and contestation in twenty-first-century US criminal justice downsizing. Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 2016; 12 :153–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110615-085046. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pickett JT. Public opinion and criminal justice policy: Theory and research. Annual Review of Criminology. 2019; 2 :405–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-011518-024826. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pickett JT, Ivanov S, Wozniak KH. Selling effective violence prevention policies to the public: A nationally representative framing experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2022; 18 :387–409. doi: 10.1007/s11292-020-09447-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Porter, N. (2021). Racial impact statements, sentencing project . Retrieved July 16 2022, from https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/racial-impact-statements/

- Provine DM, Varsanyi MW, Lewis PG, Decker SH. Policing immigrants: Local law enforcement on the front lines. University of Chicago Press; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Raphael S. The Intended and Unintended Consequences of Ban the Box. Annual Review of Criminology. 2021; 4 (1):191–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev-criminol-061020-022137. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Raphael S, Stoll MA. Why are so many Americans in prison? Russell Sage Foundation; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]