Customer experience: a systematic literature review and consumer culture theory-based conceptualisation

- Published: 15 February 2020

- Volume 71 , pages 135–176, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Muhammad Waqas 1 ,

- Zalfa Laili Binti Hamzah 1 &

- Noor Akma Mohd Salleh 2

10k Accesses

47 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The study aims to summarise and classify the existing research and to better understand the past, present, and the future state of the theory of customer experience. The main objectives of this study are to categorise and summarise the customer experience research, identify the extant theoretical perspectives that are used to conceptualise the customer experience, present a new conceptualisation and conceptual model of customer experience based on consumer culture theory and to highlight the emerging trends and gaps in the literature of customer experience. To achieve the stated objectives, an extensive literature review of existing customer experience research was carried out covering 49 journals. A total of 99 empirical and conceptual articles on customer experience from the year 1998 to 2019 was analysed based on different criteria. The findings of this study contribute to the knowledge by highlighting the role of customer attribution of meanings in defining their experiences and how such experiences can predict consumer behaviour.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Online influencer marketing

Customer engagement in social media: a framework and meta-analysis

Customer experience: fundamental premises and implications for research

Abbott L (1955) Quality and competition. Columbia University Press, New York

Google Scholar

Addis M, Holbrook MB (2001) On the conceptual link between mass customisation and experiential consumption: an explosion of subjectivity. J Consum Behav 1:50–66

Alben L (1996) Defining the criteria for effective interaction design. Interactions 3:11–15

Allen CT, Fournier S, Miller F (2008) Brands and their meaning makers. In: Haugtvedt C, Herr P, Kardes F (eds) Handbook of consumer psychology. Taylor & Francis, Milton Park, pp 781–822

Andreini D, Pedeliento G, Zarantonello L, Solerio C (2019) A renaissance of brand experience: advancing the concept through a multi-perspective analysis. J Bus Res 91:123–133

Arnold MJ, Reynolds KE, Ponder N, Lueg JE (2005) Customer delight in a retail context: investigating delightful and terrible shopping experiences. J Bus Res 58:1132–1145

Arnould EJ, Thompson CJ (2005) Consumer culture theory (CCT): twenty years of research. J Consum Res 31:868–882

Beckman E, Kumar A, Kim Y-K (2013) The impact of brand experience on downtown success. J Travel Res 52:646–658

Belk RW, Costa JA (1998) The mountain man myth: a contemporary consuming fantasy. J Consum Res 25:218–240

Bennett R, Härtel CE, McColl-Kennedy JR (2005) Experience as a moderator of involvement and satisfaction on brand loyalty in a business-to-business setting 02-314R. Ind Mark Manag 34:97–107

Berry LL (2000) Cultivating service brand equity. J Acad Mark Sci 28:128–137

Berry LL, Carbone LP, Haeckel SH (2002) Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 43:85–89

Biedenbach G, Marell A (2010) The impact of customer experience on brand equity in a business-to-business services setting. J Brand Manag 17:446–458

Bilgihan A, Okumus F, Nusair K, Bujisic M (2014) Online experiences: flow theory, measuring online customer experience in e-commerce and managerial implications for the lodging industry. Inf Technol Tour 14:49–71

Bilro RG, Loureiro SMC, Ali F (2018) The role of website stimuli of experience on engagement and brand advocacy. J Hosp Tour Technol 9:204–222

Bolton RN, Kannan PK, Bramlett MD (2000) Implications of loyalty program membership and service experiences for customer retention and value. J Acad Mark Sci 28:95–108

Brakus JJ, Schmitt BH, Zarantonello L (2009) Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J Mark 73:52–68

Branch JD (2007) Postmodern consumption and the high-fidelity audio microculture. In: Belk RW, Sherry JF Jr (eds) Consumer culture theory. JAI Press, Oxford

Braun-LaTour KA, LaTour MS (2005) Transforming consumer experience: when timing matters. J Advert 34:19–30

Braun-LaTour KA, LaTour MS, Pickrell JE, Loftus EF, SUia (2004) How and when advertising can influence memory for consumer experience. J Advert 33:7–25

Bridges E, Florsheim R (2008) Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: the online experience. J Bus Res 61:309–314

Brodie RJ, Ilic A, Juric B, Hollebeek L (2013) Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: an exploratory analysis. J Bus Res 66:105–114

Bronner F, Neijens P (2006) Audience experiences of media context and embedded advertising-a comparison of eight media international. Int J Mark Res 48:81–100

Calder BJ, Malthouse EC, Schaedel U (2009) An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. J Interact Mark 23:321–331

Carù A, Cova B (2003) Revisiting consumption experience: a more humble but complete view of the concept. Mark Lett 3:267–286

Chandler JD, Lusch RF (2015) Service systems: a broadened framework and research agenda on value propositions, engagement, and service experience. J Serv Res 18:6–22

Constantinides E (2004) Influencing the online consumer’s behavior: the web experience. Internet Res 14:111–126

Constantinides E, Lorenzo-Romero C, Gómez MA (2010) Effects of web experience on consumer choice: a multicultural approach. Internet Res 20:188–209

Cooper H, Schembri S, Miller D (2010) Brand-self identity narratives in the James Bond movies. Psychol Mark 27:557–567

Cova B (1997) Community and consumption: towards a definition of the “linking value” of product or services. Eur J Mark 31:297–316

Creswell JW (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Das K (2009) Relationship marketing research (1994–2006) an academic literature review and classification. Mark Intell Plan 27:326–363

Das G, Agarwal J, Malhotra NK, Varshneya G (2019) Does brand experience translate into brand commitment? A mediated-moderation model of brand passion and perceived brand ethicality. J Bus Res 95:479–490

Daugherty T, Li H, Biocca F (2008) Consumer learning and the effects of virtual experience relative to indirect and direct product experience. Psychol Mark 25:568–586

De Keyser A, Lemon KN, Klaus P, Keiningham TL (2015) A framework for understanding and managing the customer experience. Marketing Science Institute working paper series, pp 15–121

de Oliveira Santini F, Ladeira WJ, Sampaio CH, Pinto DC (2018) The brand experience extended model: a meta-analysis. J Brand Manag 25:519–535

De Vries L, Gensler S, Leeflang PS (2012) Popularity of brand posts on brand fan pages: an investigation of the effects of social media marketing. J Interact Mark 26:83–91

Ding CG, Tseng TH (2015) On the relationships among brand experience, hedonic emotions, and brand equity. Eur J Mark 49:994–1015

Elliot S, Fowell S (2000) Expectations versus reality: a snapshot of consumer experiences with internet retailing. Int J Inf Manag 20:323–336

Escalas et al (2013) Self-identity and consumer behavior. J Consum Res 39:15–18

Farndale E, Kelliher C (2013) Implementing performance appraisal: exploring the employee experience. Hum Resour Manag 52:879–897

Fisch C, Block J (2018) Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Manag Rev Q 68:103–106

Flavián C, Guinalíu M, Gurrea R (2006) The influence of familiarity and usability on loyalty to online journalistic services: the role of user experience. J Retail Consum Serv 13:363–375

Forlizzi J, Battarbee K (2004) Understanding experience in interactive systems. In: Proceedings of the 5th conference on designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques. ACM, New York, pp 261–268

Frambach RT, Roest HC, Krishnan TV (2007) The impact of consumer internet experience on channel preference and usage intentions across the different stages of the buying process. J Interact Mark 21:26–41

Froehle CM, Roth AV (2004) New measurement scales for evaluating perceptions of the technology-mediated customer service experience. J Oper Manag 22:1–21

Frow P, Payne A (2007) Towards the ‘perfect’ customer experience. J Brand Manag 15:89–101

Garg R, Rahman Z, Kumar I (2011) Customer experience: a critical literature review and research agenda. Int J Serv Sci 4:146–173

Geertz C (2008) Local knowledge: further essays in interpretive anthropology. Basic books, New York

Gensler S, Völckner F, Liu-Thompkins Y, Wiertz C (2013) Managing brands in the social media environment. J Interact Mark 27:242–256

Gentile C, Spiller N, Noci G (2007) How to sustain the customer experience: an overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. Eur Manag J 25:395–410

Goldstein SM, Johnston R, Duffy J, Rao J (2002) The service concept: the missing link in service design research? J Oper Manag 20:121–134

Grace D, O’Cass A (2004) Examining service experiences and post-consumption evaluations. J Serv Mark 18:450–461

Greenwell TC, Fink JS, Pastore DL (2002) Assessing the influence of the physical sports facility on customer satisfaction within the context of the service experience. Sport Manag Rev 5:129–148

Grewal D, Levy M, Kumar V (2009) Customer experience management in retailing: an organizing framework. J Retail 85:1–14

Ha HY, Perks H (2005) Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: brand familiarity, satisfaction and brand trust. J Consum Behav An Int Res Rev 4:438–452

Hamzah ZL, Alwi SFS, Othman MN (2014) Designing corporate brand experience in an online context: a qualitative insight. J Bus Res 67:2299–2310

Harris P (2007) We the people: the importance of employees in the process of building customer experience. J Brand Manag 15:102–114

Harris K, Baron S, Parker C (2000) Understanding the consumer experience: it’s’ good to talk’. J Mark Manag 16:111–127

Hassenzahl M (2008) User experience (UX): towards an experiential perspective on product quality. In: Proceedings of the 20th conference on l’Interaction Homme-Machine. ACM, pp 11–15

Hatcher EP (1999) Art as culture: an introduction to the anthropology of art. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport

Hepola J, Karjaluoto H, Hintikka A (2017) The effect of sensory brand experience and involvement on brand equity directly and indirectly through consumer brand engagement. J Prod Brand Manag 26:282–293

Hirschman EC, Holbrook MB (1982) Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J Mark 46:92–101

Hoffman DL, Novak TP (1996) Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: conceptual foundations. J Mark 60:50–68

Hoffman DL, Novak TP (2017) Consumer and object experience in the internet of things: an assemblage theory approach. J Consum Res 44:1178–1204

Holbrook MB, Hirschman EC (1982) The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J Consum Res 9:132–140

Hollebeek LD, Glynn MS, Brodie RJ (2014) Consumer brand engagement in social media: conceptualization, scale development and validation. J Int Mark 28:149–165

Holt DB (2003) Brands and branding. Harvard Business School, Boston

Homburg C, Jozić D, Kuehnl C (2017) Customer experience management: toward implementing an evolving marketing concept. J Acad Mark Sci 45:377–401

Hsu HY, Tsou H-T (2011) Understanding customer experiences in online blog environments. Int J Inf Manag 31:510–523

Huang P, Lurie NH, Mitra S (2009) Searching for experience on the web: an empirical examination of consumer behavior for search and experience goods. J Mark 73:55–69

Hultén B (2011) Sensory marketing: the multi-sensory brand-experience concept. Eur Bus Rev 23:256–273

Iglesias O, Singh JJ, Batista-Foguet JM (2011) The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. J Brand Manag 18:570–582

Islam JU, Rahman Z (2016) The transpiring journey of customer engagement research in marketing: a systematic review of the past decade. Manag Dec 54:2008–2034

Jacoby J (2002) Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: an evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J Consum Psychol 12:51–57

Kaplan S (1992) The restorative environment: nature and human experience. In: Relf D (ed) The role of horticulture in human well-being and social development. Timber Press, Arlington, pp 134–142

Keng C-J, Ting H-Y, Chen Y-T (2011) Effects of virtual-experience combinations on consumer-related “sense of virtual community”. Internet Res 21:408–434

Khalifa M, Liu V (2007) Online consumer retention: contingent effects of online shopping habit and online shopping experience. Eur J Inf Syst 16:780–792

Khan I, Fatma M (2017) Antecedents and outcomes of brand experience: an empirical study. J Brand Manag 24:439–452

Khan I, Rahman Z (2015) Brand experience formation mechanism and its possible outcomes: a theoretical framework. Mark Rev 15:239–259

Khan I, Rahman Z, Fatma M (2016) The role of customer brand engagement and brand experience in online banking. Int J Bank Mark 34:1025–1041

Kim H, Suh K-S, Lee U-K (2013) Effects of collaborative online shopping on shopping experience through social and relational perspectives. Inf Manag 50:169–180

Kinard BR, Hartman KB (2013) Are you entertained? The impact of brand integration and brand experience in television-related advergames. J Advert 42:196–203

Kozinets RV (2001) Utopian enterprise: articulating the meanings of Star Trek’s culture of consumption. J Consum Res 28:67–88

Kozinets RV (2002) Can consumers escape the market? Emancipatory illuminations from burning man. J Consum Res 29:20–38

Kuksov D, Shachar R, Wang K (2013) Advertising and consumers’ communications. Mark Sci 32:294–309

LaSalle D, Britton TA (2003) Priceless: turning ordinary products into extraordinary experiences. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Laugwitz B, Held T, Schrepp M (2008) Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In: Symposium of the Austrian HCI and usability engineering group. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 63–76

Lee YH, Lim EAC (2008) What’s funny and what’s not: the moderating role of cultural orientation in ad humor. J Advert 37:71–84

Lemke F, Clark M, Wilson H (2011) Customer experience quality: an exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. J Acad Mark Sci 39:846–869

Lemon KN, Verhoef PC (2016) Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J Mark 80:69–96

Lin YH (2015) Innovative brand experience’s influence on brand equity and brand satisfaction. J Bus Res 68:2254–2259

Lindsey-Mullikin J, Munger JL (2011) Companion shoppers and the consumer shopping experience. J Relatsh Mark 10:7–27

Loureiro SMC, de Araújo CMB (2014) Luxury values and experience as drivers for consumers to recommend and pay more. J Retail Consum Serv 21:394–400

Lundqvist A, Liljander V, Gummerus J, Van Riel A (2013) The impact of storytelling on the consumer brand experience: the case of a firm-originated story. J Brand Manag 20:283–297

Mann SJ (2001) Alternative perspectives on the student experience: alienation and engagement. Stud High Educ 26:7–19

Martin J, Mortimer G, Andrews L (2015) Re-examining online customer experience to include purchase frequency and perceived risk. J Retail Consum Serv 25:81–95

Mascarenhas OA, Kesavan R, Bernacchi M (2006) Lasting customer loyalty: a total customer experience approach. J Consum Mark 23:397–405

McCarthy J, Wright P (2004) Technology as experience. Interactions 11:42–43

Menon S, Kahn B (2002) Cross-category effects of induced arousal and pleasure on the Internet shopping experience. J Retail 78:31–40

Mersey RD, Malthouse EC, Calder BJ (2010) Engagement with online media. J Media Bus Stud 7:39–56

Meyer C, Schwager A (2007) Customer experience. Harv Bus Rev 85:1–11

Milligan A, Smith S (2002) Uncommon practice: People who deliver a great brand experience. Financial Times/Prentice Hall, London

Mollen A, Wilson H (2010) Engagement, telepresence and interactivity in online consumer experience: reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. J Bus Res 63:919–925

Morgan-Thomas A, Veloutsou C (2013) Beyond technology acceptance: brand relationships and online brand experience. J Bus Res 66:21–27

Mosley RW (2007) Customer experience, organisational culture and the employer brand. J Brand Manag 15:123–134

Mosteller J, Donthu N, Eroglu S (2014) The fluent online shopping experience. J Bus Res 67:2486–2493

MSI (2016) Research priorities 2016–2018. http://www.msi.org/research/2016-2018-research-priorities/ . Accessed 28 Aug 2017

MSI (2018) Research priorities 2018–2020. Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge

Mulet-Forteza C, Genovart-Balaguer J, Mauleon-Mendez E, Merigó JM (2019) A bibliometric research in the tourism, leisure and hospitality fields. J Bus Res 101:819–827

Nairn A, Griffin C, Gaya Wicks P (2008) Children’s use of brand symbolism: a consumer culture theory approach. Eur J Mark 42:627–640

Nambisan S, Baron RA (2007) Interactions in virtual customer environments: implications for product support and customer relationship management. J Int Mark 21:42–62

Ngo LV, Northey G, Duffy S, Thao HTP (2016) Perceptions of others, mindfulness, and brand experience in retail service setting. J Retail Consum Serv 33:43–52

Novak TP, Hoffman DL, Yung Y-F (2000) Measuring the customer experience in online environments: a structural modeling approach. Mark Sci 19:22–42

Nysveen H, Pedersen PE (2004) An exploratory study of customers’ perception of company web sites offering various interactive applications: moderating effects of customers’ Internet experience. Dec Support Syst 37:137–150

Nysveen H, Pedersen PE (2014) Influences of cocreation on brand experience. Int J Mark Res 56:807–832

Nysveen H, Pedersen PE, Skard S (2013) Brand experiences in service organizations: exploring the individual effects of brand experience dimensions. J Brand Manag 20:404–423

O’Cass A, Grace D (2004) Exploring consumer experiences with a service brand. J Prod Brand Manag 13:257–268

Ofir C, Raghubir P, Brosh G, Monroe KB, Heiman A (2008) Memory-based store price judgments: the role of knowledge and shopping experience. J Retail 84:414–423

Palmer A (2010) Customer experience management: a critical review of an emerging idea. J Serv Mark 24:196–208

Piedmont RL, Leach MM (2002) Cross-cultural generalizability of the spiritual transcendence scale in india: spirituality as a universal aspect of human experience. Am Behav Sci 45:1888–1901

Pine BJ, Gilmore JH (1998) Welcome to the experience economy. Harv Bus Rev 76:97–105

Ponsonby-Mccabe S, Boyle E (2006) Understanding brands as experiential spaces: axiological implications for marketing strategists. J Strateg Mark 14:175–189

Prahalad CK, Ramaswamy V (2004) Co-creation experiences: the next practice in value creation. J Interact Mark 18:5–14

Rageh Ismail A, Melewar T, Lim L, Woodside A (2011) Customer experiences with brands: literature review and research directions. Mark Rev 11:205–225

Rahman M (2014) Differentiated brand experience in brand parity through branded branding strategy. J Strateg Mark 22:603–615

Ramaseshan B, Stein A (2014) Connecting the dots between brand experience and brand loyalty: the mediating role of brand personality and brand relationships. J Brand Manag 21:664–683

Rigby D (2011) The future of shopping. Harv Bus Rev 89:65–76

Robertson TS, Gatignon H, Cesareo L (2018) Pop-ups, ephemerality, and consumer experience: the centrality of buzz. J Assoc Consum Res 3:425–439

Rose S, Hair N, Clark M (2011) Online customer experience: a review of the business-to-consumer online purchase context. Int J Manag Rev 13:24–39

Rose S, Clark M, Samouel P, Hair N (2012) Online customer experience in e-retailing: an empirical model of antecedents and outcomes. J Retail 88:308–322

Roswinanto W, Strutton D (2014) Investigating the advertising antecedents to and consequences of brand experience. J Promot Manag 20:607–627

Salmon P (1989) Personal stances in learning. In: Weil SW, McGill I (eds) Making sense of experiential learning: diversity in theory and practice. The Open University Press, Milton Keynes, pp 230–241

Schembri S, Sandberg J (2002) Service quality and the consumer’s experience: towards an interpretive approach. Mark Theory 2:189–205

Schivinski B, Christodoulides G, Dabrowski D (2016) Measuring consumers’ engagement with brand-related social-media content. J Advert Res 56:64–80

Schmitt B (1999) Experiential marketing. J Mark Manag 15:53–67

Schmitt B (2000) Creating and managing brand experiences on the internet. Des Manag J 11:53–58

Schmitt B, Joško Brakus J, Zarantonello L (2015) From experiential psychology to consumer experience. J Consum Psychol 25:166–171

Scholz J, Smith AN (2016) Augmented reality: designing immersive experiences that maximize consumer engagement. Bus Horiz 59:149–161

Schouten JW, McAlexander JH, Koenig HF (2007) Transcendent customer experience and brand community. J Acad Mark Sci 35:357–368

Shaw C, Ivens J (2002) Building great customer experiences, vol 241. Palgrave, London

Sherry JF, Kozinets RV (2007) Comedy of the commons: nomadic spirituality and the Burning Man festival. In: Belk RW, Sherry JF (eds) Consumer culture theory. JAI Press, Oxford, pp 119–147

Shimp TA, Andrews JC (2013) Advertising, promotion, and other aspects of integrated marketing communications, 9th edn. Cengage Learning, Mason

Singh S, Sonnenburg S (2012) Brand performances in social media. J Interact Mark 26:189–197

Skadberg YX, Kimmel JR (2004) Visitors’ flow experience while browsing a web site: its measurement, contributing factors and consequences. Comput Hum Behav 20:403–422

Smith S, Wheeler J (2002) Managing the customer experience: turning customers into advocates. Financial Times/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Syrdal HA, Briggs E (2018) Engagement with social media content: a qualitative exploration. J Mark theory Pract 26:4–22

Tafesse W (2016a) Conceptualization of brand experience in an event marketing context. J Promot Manag 22:34–48

Tafesse W (2016b) An experiential model of consumer engagement in social media. J Prod Brand Manag 25:424–434

Takatalo J, Nyman G, Laaksonen L (2008) Components of human experience in virtual environments. Comput Hum Behav 24:1–15

Tax SS, Brown SW, Chandrashekaran M (1998) Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: implications for relationship marketing. J Mark 62:60–76

Thompson CJ, Locander WB, Pollio HR (1989) Putting consumer experience back into consumer research: the philosophy and method of existential-phenomenology. J Consum Res 16:133–146

Thorbjørnsen H, Supphellen M, Nysveen H, Egil P (2002) Building brand relationships online: a comparison of two interactive applications. J Interact Mark 16:17–34

Trevinal AM, Stenger T (2014) Toward a conceptualization of the online shopping experience. J Retail Consum Serv 21:314–326

Triantafillidou A, Siomkos G (2018) The impact of facebook experience on consumers’ behavioral brand engagement. J Res Interact Mark 12:164–192

Turner P (2017) A psychology of user experience: involvement, Affect and Aesthetics. Springer, Cham

Underwood LG, Teresi JA (2002) The daily spiritual experience scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann Behav Med 24:22–33

Van Noort G, Voorveld HA, Van Reijmersdal EA (2012) Interactivity in brand web sites: cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses explained by consumers’ online flow experience. J Interact Mark 26:223–234

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2008) Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. J Acad Mark Sci 36:1–10

Verhoef PC, Lemon KN, Parasuraman A, Roggeveen A, Tsiros M, Schlesinger LA (2009) Customer experience creation: determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J Retail 85:31–41

Walls A, Okumus F, Wang Y, Kwun DJ-W (2011) Understanding the consumer experience: an exploratory study of luxury hotels. J Hosp Mark Manag 20:166–197

Wan Y, Nakayama M, Sutcliffe N (2012) The impact of age and shopping experiences on the classification of search, experience, and credence goods in online shopping. Inf Syst E bus Manag 10:135–148

Whitener EM (2001) Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect employee commitment? A cross-level analysis using hierarchical linear modeling. J Manag 27:515–535

Won Jeong S, Fiore AM, Niehm LS, Lorenz FO (2009) The role of experiential value in online shopping: the impacts of product presentation on consumer responses towards an apparel web site. Internet Res 19:105–124

Wooten DB, Reed A II (1998) Informational influence and the ambiguity of product experience: order effects on the weighting of evidence. J Consum Psychol 7:79–99

Yoon D, Youn S (2016) Brand experience on the website: its mediating role between perceived interactivity and relationship quality. J Interact Advert 16:1–15

Zarantonello L, Schmitt BH (2010) Using the brand experience scale to profile consumers and predict consumer behaviour. J Brand Manag 17:532–540

Zarantonello L, Schmitt BH (2013) The impact of event marketing on brand equity: the mediating roles of brand experience and brand attitude. Int J Advert 32:255–280

Zenetti G, Klapper D (2016) Advertising effects under consumer heterogeneity–the moderating role of brand experience, advertising recall and attitude. J Retail 92:352–372

Zhang H, Lu Y, Gupta S, Zhao L (2014) What motivates customers to participate in social commerce? The impact of technological environments and virtual customer experiences. Inf Manag 51:1017–1030

Zhang H, Lu Y, Wang B, Wu S (2015) The impacts of technological environments and co-creation experiences on customer participation. Inf Manag 52:468–482

Zolfagharian M, Jordan AT (2007) Multiracial identity and art consumption. In: Belk RW, Sherry JF Jr (eds) Consumer culture theory. JAI Press, Oxford

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank editor-in-chief (Prof. Dr Joern Block), and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Marketing, Faculty of Business and Accountancy, Graduate School of Business, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Muhammad Waqas & Zalfa Laili Binti Hamzah

Department of Operation and Management Information System, Faculty of Business and Accountancy, Graduate School of Business, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Noor Akma Mohd Salleh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zalfa Laili Binti Hamzah .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See Table 8 .

See Table 9 .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Waqas, M., Hamzah, Z.L.B. & Salleh, N.A.M. Customer experience: a systematic literature review and consumer culture theory-based conceptualisation. Manag Rev Q 71 , 135–176 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00182-w

Download citation

Received : 08 May 2019

Accepted : 10 February 2020

Published : 15 February 2020

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00182-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Customer experience

- Literature review

- Consumer culture theory

- Online experience

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

COVID-19, consumer behavior, technology, and society: A literature review and bibliometric analysis

Jorge cruz-cárdenas.

a Research Center in Business, Society, and Technology, ESTec, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Machala y Sabanilla s/n, 170301 Quito, Ecuador

b School of Administrative and Economic Science, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Machala y Sabanilla s/n, 170301 Quito, Ecuador

Ekaterina Zabelina

c Department of Psychology, Chelyabinsk State University, Bratiev Kashirinykh 129, 454001 Chelyabinsk, Russia

Jorge Guadalupe-Lanas

Andrés palacio-fierro.

d Programa doctoral en Ciencias Jurídicas y Económicas, Universidad Camilo José Cela, Castillo de Alarcón, 49, 28692 Madrid, Spain

Carlos Ramos-Galarza

e Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Av . 12 de octubre 1076, 170523, Quito, Ecuador

f Centro de Investigación MIST, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Machala y Sabanilla s/n, 170301 Quito, Ecuador

Associated Data

The COVID-19 crisis is among the most disruptive events in recent decades. Its profound consequences have garnered the interest of many studies in various disciplines, including consumer behavior, thereby warranting an effort to review and systematize the literature. Thus, this study systematizes the knowledge generated by 70 COVID-19 and consumer behavior studies in the Scopus database. It employs descriptive analysis, highlighting the importance of using quantitative methods and China and the US as research settings. Co-occurrence analysis further identified various thematic clusters among the studies. The input-process-output consumer behavior model guided the systematic review, covering several psychological characteristics and consumer behaviors. Accordingly, measures adopted by governments, technology, and social media stand out as external factors. However, revised marketing strategies have been oriented toward counteracting various consumer risks. Hence, given that technological and digital formats mark consumer behavior, firms must incorporate digital transformations in their process.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is among the most relevant events of recent decades. Its social and economic consequences on a global level are enormous. At the social level, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported over four million global deaths due to COVID-19 ( WHO, 2021a ). Economies have also been severely affected ( Donthu and Gustafsson, 2020 ). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that the gross domestic product, worldwide, will plummet to about 4.9% in 2020 ( IMF, 2020 ). These remarkable social and economic implications of the pandemic and its unique features have inspired many studies from various disciplines, including consumer behavior. The crisis scenario has profoundly shifted consumer behavior toward one based on technology ( Sheth, 2020 ).

In prior pandemics, social and behavioral science research focused heavily on preventive and health behavior, while consumer behavior received less attention ( Laato et al., 2020 ). The situation has been different for the COVID-19 pandemic; COVID-19 and consumer behavior studies proliferate the literature. Reasonably, such rapidly accumulating bodies of knowledge require organization and systematization, lest such knowledge produced in fast-growing fields remains fragmented ( Snyder, 2019 ). Thus, this study fulfills this need by identifying knowledge generated by 70 relevant studies in the Scopus database, indexed up to January 5, 2021, for systematic processing.

Prior theoretical efforts created a global and general perspective of consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Such efforts have sought to propose possible stages in behavior, comparing old and new consumption habits, or explain behaviors based on similarities with other crises and disruptive events, such as other pandemics, wars, or natural disasters (e.g., Kirk and Rifkin, 2020 ; Sheth, 2020 ; Zwanka and Buff, 2020 ). However, this study is evidently among the first to review the literature on COVID-19 and consumer behavior. The study is necessary because, beyond its similarities with other disruptive events, the COVID-19 crisis has several fundamental differences. First, it is truly global ( Brem et al., 2020 ). Second, it coincides with the rapid advance of various disruptive technologies, the confluence of which has been called “digital transformation” ( Abdel-Basset et al., 2021 ).

First, the study conducts descriptive and bibliometric analyses of the 70 selected COVID-19 and consumer behavior articles. Second, an input-process-output consumer behavior model is used to systematize the existing literature. The model, adapted by Cruz-Cárdenas and Arévalo-Chávez (2018) from Schiffman and Wisenblit (2015) for systematic reviews, furnished a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic-era consumer behavior via macro-environmental, micro-environmental, and internal-consumer-factor integration.

Accordingly, government regulations and technology stand out as fundamental forces at the macro level. At the micro-level, specific technological applications like social media and business platforms, social group and family pressure, and marketing strategies stand out. Meanwhile, many personal and psychological characteristics help us to understand how consumers process external influences and make decisions at the consumer level. Finally, regarding purchasing behaviors, the use and adoption of technologies like e-commerce platforms have had a prominent place in consumer behavior during the pandemic.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the construction of a theoretical framework on consumer behavior and disruptive events. The method is explained in Section 3 . Section 4 presents the descriptive and co-occurrence bibliometric technique results of generating an understanding of the literature interrelationships and characteristics. Section 5 documents the systematization and grouping of the knowledge generated based on an input-process-output model of consumer behavior. Finally, Section 6 concludes with the main implications and scope for future research.

2. Consumer behavior and disruptive events

Many consumer and human behavior studies in the context of disruptive events precede the COVID-19 pandemic. The term “disruptive event” is a situation that leads to profound changes regarding the unit analyzed ( Dahlhamer and Tierney, 1998 ). Thus, it can apply to individual consumers, organizations, industries, or society. Disruptive events can also be classified by their nature (e.g., pandemic, war, natural disaster, and personal calamity).

At the personal level, prior studies establish that in the aftermath of calamities or unfavorable events, such as the death of loved ones, divorces, and illness, consumers get rid of products that remind them of difficult times and, thus, buy new products ( Cruz-Cárdenas and Arévalo-Chávez, 2018 ). Although such disruption studies are interesting, they fail to shed enough light on consumer behavior during the COVID-19 crisis. On a larger scale, past disruptive events—such as other pandemics, natural disasters, or extreme social violence and terrorism—can contribute to understanding the pandemic-induced consumer behavior, because they affect a greater number of consumers simultaneously and in similar fashion.

Natural disasters like earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, and typhoons are frequent. They cause damage to infrastructure, economy, and human lives, thereby creating a permanent field of consumer behavior studies. Some natural disasters are carefully monitored, and their arrival and intensity can be anticipated (e.g., hurricanes). The anticipation of such events induces a behavior of stockpiling basic necessities ( Pan et al., 2020 ). Others cannot be anticipated in the short term (e.g., earthquakes). In both types of natural disasters, consumers may lose possessions and loved ones. The feeling of loss induces impulsive, therapeutic, and replacement purchases ( Delorme et al., 2004 ; Sneath et al., 2009 ). Natural disasters are primarily noted for their destructiveness and scope, which can reach regional levels.

Extreme social violence and so-called terrorism constitute another category of disruptive events affecting a country or region. Terrorism comprises violent actions by a group with less power that seeks to destabilize a government or a dominant organization ( Bates and LaBrecque, 2019 ). Such violent actions often impact human lives and negatively affect the economy and physical infrastructure. Moreover, their intensity and frequency in society are highly variable.

Although terrorist actions significantly affect the economy and infrastructure, the impact on consumer behavior is in the short term ( Baumert et al., 2020 ; Crawford, 2012 ), which induces an avoidant behavior, due to certain consumption options they consider to be of greater risk; that is, consumers choose an alternative option rather than give up their plans or consumption ( Herzenstein et al., 2015 ) (e.g., the choice between air and land travel or a destination change for tourism). The selection of consumption alternatives hinges on past events and anticipated threats ( Baumert et al., 2020 ).

Prior outbreaks from recent decades like SARS, Influenza A, and H1N1 present another type of disruptive event, which consumer behavior scholars have largely ignored ( Laato et al., 2020 ). Current knowledge on human behavior during disease outbreaks stems from other social and human sciences. Thus, two consumption-behavior types have been noted: purchasing necessities and protective equipment, and curbing leisure outside the home. For example, Goodwin et al. (2009) find that the purchase of protective items (e.g., masks and personal hygiene items) and food rose significantly during the influenza A, and H1N1 outbreaks, as people engaged in stockpiling. However, regarding SARS in China, Wen et al. (2005) found that people altered their leisure activities, modes of transportation, and the places they visited. Table 1 summarizes the features of prior disruptive events and the relevant knowledge regarding consumer behavior therein.

Disruptive events, their characteristics, and effects on the consumer.

The COVID-19 pandemic, like other prior disruptive events, has significantly impacted the economy and human life ( IMF, 2020 ; WHO, 2021a ). However, unlike natural disasters and terrorism, it (similar to prior disease outbreaks) does not damage physical infrastructure. Further, it is characterized by its persistence (the current pandemic has continued for a year and a half). Even so, the COVID-19 pandemic is unique in its global scope ( WHO, 2021b ). Moreover, it occurs within the context of significant technological advancement, known in the business and organizational world as “digital transformation” ( Abdel-Basset et al., 2021 ).

Against this comparison, prior to the systematic review, consumer behaviors reported in other disruptive events probably occurred on a large scale. However, the scope of the COVID-19 pandemic and technological advancement is expected to provide a distinctive character to consumer behavior, caught between the unique confluences of the two.

This study was developed in a series of stages, common to systematic literature reviews ( Balaid et al., 2016 ; Cruz-Cárdenas and Arévalo-Chávez, 2018 : Osobajo and Moore, 2017 ) (see Fig. 1 ).

Stages of this study.

3.1 Study objectives

Regarding Stage 1, this study primarily describes and systematizes the existing literature on consumer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. This objective can be broken down into three specific objectives. Thus, this study aims

- • O1: To describe the characteristics and interrelationships of relevant studies

- • O2: To generate a structured systematization of their contents and results

- • O3: To establish the limitations and gaps in existing knowledge, thereby ascertaining the scope for future lines of research

Accordingly, recognizing the multidisciplinary nature of consumer behavior, researchers from marketing, business administration, psychology, and economics teamed up to bring together experts in diverse research methodologies, such as machine learning and big data techniques. The study commenced when COVID-19 became a pandemic in March 2020.

3.2 Criteria for inclusion of articles

The study developed several article-inclusion criteria. Importantly, studies must address COVID-19 only from the perspective of consumer behavior. Thus, it was important to differentiate consumer behavior from other types of human behavior in the COVID-19 framework. Consumer behavior encompasses people's behavior in their search, purchase, usage, and disposal of goods and services ( Schiffman and Wisenblit, 2015 ). Further, articles must have an acceptable quality level, be written only in English, and have no time restriction on the date of their publication.

3.3 Search strategies

The search strategies were then developed, operationalizing the inclusion criteria. The study drew from the Scopus database, which offers a good balance between quality and coverage ( Singh et al., 2020 ). The search terms aimed to extract two central contents simultaneously: the COVID-19 pandemic and consumer behavior. The search process was initiated with the following terms: Covid AND (consum* AND behav*). The asterisk in the terms allowed for including variants of the keywords such as: consumer, consumers, consumption behavior, and behavior. Additionally, the search scanned the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the documents.

As the search process progressed, other terms were added, because they were also used significantly by relevant articles; this was particularly important because there was no consensus regarding the name for the pandemic at its inception. Hence, regarding the pandemic, alternative terms included “Covid-19,” “Sars-Cov-2,” “Pandemic,” and “Coronavirus.” Similarly, regarding consumer behavior, “marketing,” “purchasing,” “shopping,” and “buying” were the alternative terms.

The search process involved reading the titles and abstracts of the outputs generated for an initial and main debugging. A second purification was then conducted. Among the biggest search challenges was that, although some articles addressed consumer behavior and included “Covid” or its synonyms in their titles, keywords, and abstracts, as well as their topic incorporation, they were unclear. The situation is attributed to a temporal coincidence with the COVID-19 crisis, rather than a deliberate intention of studying its effects on consumer behavior. From the start of the study to its culmination on January 5, 2021, 347 articles were reviewed, of which 70 relevant articles were selected after satisfying the inclusion and search criteria.

3.4 Method describing and systematizing the literature

The study employed various bibliometric and literature systematization techniques, to describe the characteristics and interrelationships of the 70 articles and systematize their content. Bibliometric techniques estimated the main descriptive statistics of the relevant body of knowledge. Further, a visual analysis of co-occurrence was performed.

The study used content analyses of the generated knowledge and findings to systematize the literature ( Kaur et al., 2021 ), seeking a knowledge organization structure. The search focused on identifying a widely accepted model of consumer behavior. Thus, the selected model was the input-process-output model of Schiffman and Wisenblit (2015) , modified by Cruz-Cárdenas and Arévalo-Chávez (2018) to apply to literature reviews on consumer behavior topics. This model is employed in empirical research (e.g., Ting et al., 2019 ).

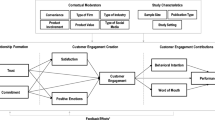

Fig. 2 presents the generic model. The left of the model presents the external influences or stimuli, processed and interpreted as per the personal and psychological characteristics of the consumer at the center of the model. The consumer also follows a decision-making process. Finally, the right of the model yields the results or outputs: the purchase and post-purchase behaviors. Furthermore, this study incorporates arrows connecting macro-environmental to micro-environmental forces, marketing strategies, and the consumer. It highlights that the macro-environment spans the entire model ( Kotler and Keller, 2016 ).

Generic model of consumer behavior. Adapted from Schiffman and Wisenblit (2015) and Cruz-Cárdenas and Arévalo-Chávez (2018) .

4. Descriptive and bibliometric analysis

4.1 descriptive analysis of relevant articles.

Table A.1 presents the 70 relevant articles, among which 57 were published in 2020; 12, 2021; and one, in press. Fig. 3 shows the number of articles per their methodology. Most articles (58 articles or 82.9%) employ quantitative empirical approximations, followed by studies with a theoretical approach (five articles or 7.1%). Notably, few studies employed qualitative or mixed methods (5.7% and 4.3%, respectively).

Number of articles according to their methodology.

This marginal use is likely for the following reasons. First, societies and funders exert time constraints for fast and conclusive results. Second, there are many studies on consumer behavior and the adoption of technologies before the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, the rise in machine learning methods, particularly natural language processing, allows for processing significant textual social media data using artificial intelligence ( Géron, 2019 ).

Considering only the 65 empirical studies, Fig. 4 presents the main countries where data was collected. China has 15 articles (23.1%), followed by the US, with seven articles (10.8%), and Italy, five articles (7.7%). Next are India, Romania, the UK, and Vietnam, each with three articles (4.6%). Others attracted 15 articles (23.1), and 11 articles (16.9%) had several countries simultaneously as study settings, either because they deliberately chose several countries or studied social media. China's dominance as a study setting can be attributed to its status as the origin of the pandemic. However, it can also be attributed to China's rapid growth in the scientific field.

Number of empirical articles according to their study setting.

Table 2 presents the journals in which the articles were published. Most articles appeared in three major journals: Sustainability had seven articles (10%), and the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health and the Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services each had five articles (7.1%), respectively. Notably, several journals not traditionally linked to consumer studies or marketing are represented, probably because of the multidisciplinary character of consumer studies ( Schiffman and Wisenblit, 2015 ).

Journals in which reviewed articles were published.

While the selected articles examined various products, food was the main preference in 29 articles (41.4%). Other products, studied to a lesser extent, included personal hygiene items, hotels, and the banking sector. Further, the studies widely employed two theories: the theory of planned behavior (TPB) ( Ajzen, 1991 ) and the technology acceptance model (TAM) ( Davis, 1989 ).

TPB stems from psychology, and it asserts that attitude toward behavior (personal view on behavior), subjective norm (perceived social pressure to act), and perceived behavioral control (difficulty in acting) determine the intention of a person to act out a behavior. This behavioral intention then determines whether the behavior occurs ( Ajzen, 1991 ). TAM stems from Information Technology and draws from TPB; it indicates that a user's acceptance of new technology is determined by the perceived usefulness and ease of use ( Davis, 1989 ). TPB and TAM are general theories that allow for much flexibility in application. The two theories and their many variants are widely used in consumer behavior research and, particularly, cases of a new product, service, and technology acceptance ( Lin and Chang, 2011 ; Schmidthuber et al., 2020 ).

Considering the prevalence of TPB and TAM, and their variants in consumer studies prior to COVID-19 (particularly regarding technologies) coupled with the massive popularity of technologies during the pandemic ( Baicu et al., 2020 : Sheth, 2020 ), the dominance of the two theories in this study is not surprising. Furthermore, they also explain the popularity of quantitative methods in the selected studies, and by specifying a set of directional relationships, they allow for testing the proposed models via structural equation modeling ( Kline, 2016 ). The studies reviewed largely model consumer purchasing behaviors in technological environments and include fear or concern about COVID-19 as an additional variable, either in an exogenous or moderating variable role.

4.2 Analysis of the co-occurrence

The study employed co-occurrence analysis to establish the topics of interest in the set of articles on COVID-19 and consumer behavior. The analysis was performed in two ways to obtain more reliable results: keyword-based and title- and abstract-based.

First, we sought to identify the clusters formed based on the co-occurrence of keywords in the set of articles ( Singh et al., 2020 ). We employed VOSviewer 1.6.15 ( VanEck and Waltman, 2010 ) for this analysis. VOSviewer suggests, by default, a minimum number of five occurrences for a term to be considered. However, we set this number to three, given the relatively small number of articles. Generic terms like “article” and “study” were removed during the data cleanup. Additionally, similar terms were grouped into a single term ( van Eck and Waltman, 2010 , 2020 ), such as “Covid-19,” “Covid,” and “pandemic.” Fig. 5 shows the obtained clusters. The nodes represent keywords or concepts, while their size corresponds with their frequency ( van Eck and Waltman, 2010 , 2020 ). VOSviewer represents each cluster of keywords or concepts with a different color.

Co-occurrence network of articles based on keywords.

Cluster 1 (yellow) has “consumer behavior” as a prominent node and groups together other keywords such as “social distance,” “social media,” and “electronic commerce.” Thus, the cluster is related to purchasing behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is strongly marked by technology use. Cluster 2 (green) has the term “COVID-19″ as its central node. It gathers terms such as “public health,” “food waste,” “food consumption,” “sustainability,” and “panic buying.” Hence, this cluster regards the consumption and handling of food during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cluster 3 (blue) has no central node. However, “fear,” “decision making,” and “purchasing” suggest a cluster focused on the purchase decision process. Finally, Cluster 4 (red), while without a prominent node, is the most prevalent. Terms such as “materialism,” “adult,” “attitude,” and “psychology,” “government,” and “economics” suggest that this cluster is mainly about macro, micro, and internal influences on the consumer.

Further, to allow for greater context richness, the second analysis was based on the titles and abstracts of selected articles ( VanEck and Waltman, 2010 ). Similar to the procedure based on keywords and with the same criteria, the minimum number of occurrences of words was set to three. The data was also cleaned by elimination or grouping ( VanEck and Waltman, 2010 ). For example, generic or irrelevant words, such as “article,” “item,” “author,” and “study,” were eliminated. However, similar terms were grouped together, as in the case of “covid,” “covid-19,” and “pandemic.” Fig. 6 shows the results of the co-occurrence analysis based on titles and abstracts.

Co-occurrence network of articles based on titles and abstracts.

The analysis generated four clusters. Cluster 1 (red) had “consumer behavior” as a prominent node and included other terms like “risk perception,” “threat,” “panic buying,” “impulsive buying,” and “China.” Thus, this cluster is related to consumer panic buying. Cluster 2 (green) had as prominent nodes “service,” “emergency,” “purchasing,” and technology-related actions, such as “online shopping,” “e-commerce,” and “internet.” Hence, it regards consumer behavior and the use of technology in purchases. Cluster 3 (blue) featured “food” as a prominent node and included other terms like “stockpiling,” “covid lockdown,” “covid outbreak,” and “policymaker.” Therefore, this cluster focused on consumer behavior in the purchase and handling of food under lockdown conditions. Cluster 4 (yellow) did not have particularly prominent nodes. It included customer,” “infection,” “policy,” “home,” “uncertainty,” “business,” and “reduction,” showing that this cluster refers to the consumer subject to macro, micro, and internal influences.

The analysis of co-occurrence of keywords is similar to that of titles and abstracts in the dominance of the reviewed studies on Covid-19 and consumer behavior, thus increasing the confidence in the results. Accordingly, three fundamental areas can be identified: consumer behavior and technology use; purchasing and handling basic necessities, particularly food; and consumer subject to internal and external (micro and macro) forces. A possible fourth area may induce a discrepancy, putting the keyword analysis emphasis on the decision-making process and the analysis of titles and abstracts in panic purchases.

5. Systematization of the relevant literature

This section presents the analysis and systematization of the 70 relevant studies. The authors used content analysis techniques to identify the main findings from the literature ( Kaur et al., 2021 ). The relevant content is organized using the structure of the consumer behavior model in Fig. 2 .

5.1 Macro-environmental factors

Macro-environmental factors affect the entire analytical micro-environment ( Kotler and Keller, 2016 ). In this study, the micro-environment is built around the consumer, the center of the analysis. The consumer micro-environment is formed by organizations and groups of people close to the consumer (e.g., companies, the media, family, and friends).

Regarding COVID-19 and consumer behavior, five macro forces are fundamental: the COVID-19 pandemic and the technological, political-legal, economic, and socio-cultural environments. High importance is attached to COVID-19, the technological environment, and the politico-legal environment. Various studies indicate how the COVID-19 and available technology confluence has induced consumers to massively and rapidly adopt technologies and increase their consumption of highly digital business formats ( Baicu et al., 2020 : Sheth, 2020 ). Specifically, e-commerce and business platform formats solved possible shortage problems and allowed consumers to accumulate products ( Hao et al., 2020 ; Pillai et al., 2020 ). Further, the technology allowed social lives to thrive amidst the pandemic, reflecting the increased use of social media platforms ( Pillai et al., 2020 ).

The political-legal environment is strongly intertwined with economic performance. Significant legal regulations by many governments were enforced during quarantines, lockdowns, social distancing, and educational service closure ( Yoo and Managi, 2020 ). However, not all governments resorted to lockdown measures. Regardless, economies fell in many areas because of consumer decisions ( Sheridan et al., 2020 ). However, food and hygiene item purchases increased. In non-lockdown (lockdown) countries, consumers were guided by caution (anxiety and fear were) ( Anastasiadou et al., 2020 ; Prentice et al., 2020 ).

Another very important aspect derived from the political-legal environment is trust in government institutions. Increased confidence in governments and their actions made consumers less likely to experience fear of food shortages and engage in panic buying ( Dammeyer, 2020 ; Jeżewska-Zychowicz et al., 2020 ). Effective public announcements moderated the effects of negative feelings, such as anxiety and a sense of losing control in terms of panic buying ( Barnes et al., 2021 ).

A diagnosis of the state of knowledge on macro-environmental factors allows for seeing a significant amount of research on political-legal and technological factors. However, the COVID-19 crisis is dynamic. Currently, many governments have halted lockdown measures, betting more on social distancing as a new mass vaccination phase emerges, which is worthy of exploration. Further, few studies address cultural issues during the COVID-19 crisis, even though culture is another determining force in consumer behavior.

5.2 Micro-environmental factors

As noted, the political-legal macro-environment of the COVID-19 pandemic is marked by lockdown and social distancing measures, while the digital transformation process marks the technological macro-environment. A logical consequence of their interaction is that the micro-environment (family, friends, acquaintances, society, the media, and companies) interacts with consumers through technology and digital media. Section 5.3 will discuss consumer interaction with businesses and companies.

During the COVID-19 crisis, consumers use information as a valuable factor in decision-making, as they actively or passively seek it. Social media is a common source of information. Popular topics regard food acquisition and storage, health issues, social distancing, and economic issues ( Laguna et al., 2020 ). However, social media also induces panic buying, especially during lockdowns. Advice from associates, product shortage perceptions, the COVID-19 spread, official announcements, and global news inspired this behavior ( Ahmend et al., 2020 ; Grashuis et al., 2020 ; (Jeżewska-Zychowicz et al., 2020) ; Naeem, 2021a ). Further, the news, social media, and associates also influence technology use in purchases on company pages, platforms, or apps ( Koch et al., 2020 ; Troise et al., 2021 ).

Therefore, despite contributing to panic buying, the mainstream news media and social media have also curbed the spread of COVID-19 ( Liu et al., 2021 ). The extensive knowledge on the micro-environmental effects on consumer behavior was generated primarily due to previous non-relevant studies that focused on social media; they created a solid base of departure.

5.3 Marketing strategies and influences

Marketing influences are in the consumer's micro-environment. They are vital, because they are tools that companies can design and control. Thus, consumer behavior models usually consider them separately from other influences, such as those discussed in the preceding section. The main marketing tool is the product or service. Others are prices, distribution, and communication strategies.

Two key elements of marketing strategies during the pandemic are reducing various risks and increasing benefits perceived by the consumer. Two central risks marketing strategies must address are the risks of coinfection and conducting online transactions. Further, the reviewed studies address the forms of action regarding the two types of risks. Thus, while the perceived COVID-19 risk increases the probability of online purchases, the perceived risk of online purchases moderates this relationship ( Gao et al., 2020 ).

Accordingly, using technology to digitize processes or products, and reduce physical contact with employees or other consumers, has encouraged consumer purchases during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, technology that allows consumers to make reservations via smartphones or kiosks reduces the perceived health risk, thereby increasing the probability of hotel reservations ( Shin and Kang, 2020 ). Moreover, state-of-the-art cleaning technology moderates the negative effect of staff interaction on service use intentions ( Shin and Kang, 2020 ). Thus, technology guarantees cleanliness and minimal contact for the consumer. Further, the perceived risk of online transactions involves the possible misuse of personal information and financial fraud ( Tran, 2021 ). Marketing strategies to reduce this risk have focused on building trust and image ( Lv et al., 2020 ; Troise et al., 2021 ). Regarding the strategy duration, other recommended marketing strategies for e-commerce sites and platforms with less renown are increasing profits or reducing prices ( Lv et al., 2020 ; Tran, 2021 ).

During the lockdowns in most countries, consumer demand centered on food products, personal hygiene, and disinfection. Thus, implementing or increasing promotions of non-priority items is a recommended strategy ( Anastasiadou et al., 2020 ). Finally, regarding small businesses that use technology less intensively, the speed of adaptation and digital transformation are vital, even at basic levels. Many small businesses have survived by adopting elementary digital transformation strategies in the form of a mix of social media sales and home delivery services ( Butu et al., 2020 ).

Hence, although there are interesting results, the transcendental importance of studies on marketing strategies within the framework of consumer studies deserves more research. Further, since the pandemic is dynamic, companies must adapt their strategies constantly. Notably, few studies employ case studies or experimental methodologies, which are appropriate for studying the effects of marketing strategies.

5.4 Personal and psychological characteristics and decision-making

Most of the reviewed studies stemmed from this area. The personal characteristics of consumers (e.g., age, gender, income, and educational level) and their psychological characteristics (e.g., motivation, perception, and attitudes) determine how they interpret stimuli ( Schiffman and Wisenblit, 2015 ).

For instance, many studies address gender. There is no consensus about which gender makes the most panic purchases. A study carried from Brazil reports that men tend to make the most panic purchases ( Lins and Aquino, 2020 ), while a study in China ( Wang et al., 2020a ) attributes this behavior to women. However, another study in several European countries found gender differences irrelevant in the tendency to make extra purchases ( Dammeyer, 2020 ). The inconsistency may be attributable to cultural issues; however, the methodology may also have a bearing on the conflicting results. For example, while the study by Lins and Aquino (2020) asked respondents about purchasing products in general, Wang et al. (2020a) focused on food, and Dammeyer (2020) on food, medicine, and hygiene items. The same discrepancy in gender issues and panic purchases extends to the age variable. Some studies found that age is negatively related to the tendency to panic buy ( Lins and Aquino, 2020 ), while other studies found no relationship at all (e.g., Dammeyer, 2020 ).

Many studies also examine the pandemic-induced negative psychological states and feelings. The perceived risk and information overload regarding COVID-19, led to sadness, anxiety, and cognitive dissonance ( Song et al., 2020b ). The perceived severity of the pandemic leads to self-isolation ( Laato et al., 2020 ). The negative psychological states that the consumer experiences, are associated with hoarding behavior. Excessive concern regarding health leads to excessive purchasing and stockpiling of food and hygiene items ( Laato et al., 2020 ). While negative emotions encourage excessive purchases, particularly the purchasing of necessities, they also discourage them from consuming services that involve contact. For example, the fear of contracting COVID-19 has been central to avoiding air transport during the pandemic ( Lamb et al., 2020 ).

Consumer personality traits were also critical to understanding consumer behavior during the COVID-19 crisis. Extraversion (conscientiousness) and neuroticism (openness to experience) were positively (negatively) associated with extra purchases ( Dammeyer, 2020 ). Another personality trait, such as agreeableness (sympathetic or considerate), led to the renunciation of consumption. Consumers with high scores on this trait gave up consumption that could negatively affect third parties ( Lamb et al., 2020 ).

The pandemic has also encouraged favorable attitudes among consumers, be they pro-environmental or pro-health attitudes. The fear of COVID-19 and the uncertainty it brings has a positive effect on people's pro-environmental attitudes, which, in turn, increase trust in green brands ( Jian et al., 2020 ). However, while consumers gave less importance to the nutritional value of food during the first months of the crisis ( Ellison et al., 2021 ), there was an increase in health awareness in later months ( Čvirik, 2020 ).

Despite great interest in consumers’ personal and psychological processes, the purchase decision-making process garnered less attention. Studies note three types of decision-making processes: impulse (e.g., Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Islam et al., 2020 ), panic (e.g., Prentice et al., 2020 ), and rational ( Wang and Hao, 2020 ) purchases.

In summary, consumer behavior, as it relates to consumers’ personal and psychological characteristics, has been widely studied, especially in its relationship with the first phases of COVID-19, characterized by lockdown and social distancing. The broad base of prior knowledge on consumer psychology and the adoption and use of technologies facilitates such studies. Here too, given the dynamic pandemic and its entry into new stages involving vaccination and social distancing, future studies must extend the discussion on personal and psychological processes. In addition, more research should be conducted on purchase decision-making processes during the COVID-19 crisis.

5.5 Purchasing behaviors

In consumer behavior models, purchasing behavior is the output of the model. This output is generated by selecting products and places or points of purchase. During the pandemic, these two behaviors were central to consumers’ strategies to ensure their own well-being.

The imposition lockdowns led to an increase in the purchase of food, beverages, hygiene items, and medicines, inducing frequent stockpiling. This behavior occurred before and during the measures and has been widely confirmed worldwide (e.g., Antonides and van Leeuwen, 2020 ; Prentice et al., 2020 ; Seiler, 2020 ;). After the lockdown and the transition to social distancing, moderate stockpiling may be expected ( Anastasiadou et al., 2020 ). Meanwhile, the consumption of goods and services in industries such as entertainment, dining, travel, and tourism decreased ( Antonides and van Leeuwen, 2020 ; Ellison et al., 2021 ; Seiler, 2020 ; Skare et al., 2021 ). Another essential aspect is the selection of the purchase method. Various purchase methods were implemented to reduce the risk of infection, among which consumers favored online purchases while making changes in their selection of physical retailers.

The lockdown and later, social distancing, inspired many consumers to rapidly adopt purchasing behaviors mediated by technology (e.g., online shopping) ( Butu et al., 2020 ), creating an “online awareness” among populations ( Zwanka and Buff, 2020 ). A digital means of purchase was extended to categories which did not have a strong online presence previously. Thus, online purchases of food, beverages, and cleaning supplies grew ( Antoides and van Leeuwen, 2020 ; Ellison et al., 2020; Hassen et al., 2020 ; Li et al., 2020b ; Wang et al., 2020b ). However, there was also an increase in the use of technology for entertainment. For example, there has been an increase in users and streaming hours on services such as Netflix and Spotify ( Madnani et al., 2020 ). Another change in consumer purchasing behavior regarded the physical point of sale. This change occurred as consumers aimed to decrease the number of trips they made to physical stores (purchase frequency) ( Laguna et al., 2020 ; Principato et al., 2020 , in press; Wang et al., 2020a ). In some countries and cities, consumers stopped buying from large retailers and places that could be crowded, preferring small local retailers instead ( Li et al., 2020b ).

Hence, there is a solid global consolidation of technology in purchasing (i.e., online shopping) and the strengthening of small local retailers. Given the dynamic nature of the COVID-19 crisis, future studies can evaluate the changes in the next stages of the pandemic.

5.6 Post-purchase behavior

Another key behavior is disposal, of which results are very interesting. During the lockdown, there is less food waste, more likely for future supply than ecological reasons ( Amicarelli and Bux, 2021 ; Jribi et al., 2020 ). However, dire health precautions increased the usage of disposable protective items, and more electronic commerce transactions increased waste created by packaging material ( Vanapalli et al., 2021 ). Thus, from a social and environmental perspective, the effects of the pandemic on product waste are mixed.

Future studies can examine product disposition and the new stages of the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, consumer satisfaction with purchases has garnered less attention in the literature. Fig. 7 presents the model of consumer behavior during the COVID-19 crisis, summarizing the systematization of the literature.

Model of consumer behavior during the COVID-19 crisis.

5.7 Consumer behavior model under COVID-19: the near future

This subsection seeks to use the model ( Figs. 2 and and7) 7 ) to anticipate consumer behaviors, given the ongoing, dynamic development of the pandemic ( WHO, 2021b ). Accordingly, the crisis thus far has induced intense consumer learning, particularly in the use of technologies (personal and psychological factors). Moreover, although technologies can satisfy both hedonic and utilitarian needs ( Cruz-Cárdenas et al., 2021 ), some consumer needs remain unsatisfied, particularly social needs (personal and psychological factors) ( Sheth, 2020 ). However, public vaccination campaigns (macro-environmental factor) and their protective effects on the population can reduce people's fear and avoidance behavior regarding certain products and services (personal and psychological factors). Further, consumers can have a greater range of consumption options (decision-making process), given their decreased fear, and due to the relaxation of restrictions on mobility and the congregation of people (macro-environmental factor). However, the trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic (macro-environmental factor) will not be a linear process, given the appearance of new waves of infections and strains ( WHO, 2021b ).

Therefore, the new consumer behavior (output or results) will not embark on a gradual return to pre-pandemic conditions. Rather, consumer learning about technologies, attenuated avoidance behavior, and unsatisfied needs mark consumer practices that tend to combine pre-COVID-19 behaviors (some intensified by the level of unsatisfied needs) with new technology-based behaviors (e.g., use of electronic banking, e-learning, e-commerce, and social media). However, this combination of old and new consumer behaviors will likely be dynamic (in varying proportions) and creative, as consumers will have to go through new stages of the pandemic marked by uncertainty.

6. Discussion, implications, and limitations

6.1 the covid-19 pandemic versus other disruptive events: differences and similarities in their nature and consumer behavior.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the context of disruptive events affecting humanity shares traits with other disruptive events and has unique characteristics. Like any disruptive event, it has profoundly impacted societies ( Dahlhamer and Tierney, 1998 ). Among its unique characteristics are its truly global scope and occurrence within the context of the “digital transformation” technological advancement ( Abdel-Basset et al., 2021 ).

Regarding consumer behavior, comparing the study findings to behaviors observed in other disruptive events yield interesting conclusions. Impulsive and panic buying seems to be common to all disruptive events. Therapeutic purchases seem to be more linked to natural disasters, where physical possessions suffer damages. The avoidance behavior of certain products and services appears to be more linked to terrorism and pandemics. However, despite these similarities, the role of technology in shopping has induced a unique consumer behavior under COVID-19. Indeed, technology has been transversal to the different consumer behaviors under COVID-19.

Consumer behavior and COVID-19 studies are characterized by three thematic areas: consumer behavior and technology use; purchase and handling of essential, hygiene, and protective products; and internal and external influences on consumers. Notably, the current pandemic is an ongoing event that follows a non-linear trajectory (WHO, 221b). Hence, the study priorities will surely change, marked by the new stages of the pandemic. For example, in light of the vaccination campaigns, the interest of future studies in the purchase and handling of basic necessities and protection products will decline. Further, given the decreased avoidance behavior, interest in the study of fun and leisure behaviors will increase. However, the use of technologies in consumption will remain at a high profile throughout the pandemic.

6.2 The nature of consumer behavior studies under the COVID-19 pandemic

Studies examining consumer behavior under the COVID-19 pandemic exhibit unique characteristics. Prior studies on consumer behavior and other disruptive events had a significant presence of qualitative studies, given their ability to explore and thoroughly understand how certain phenomena profoundly affect people's lives ( Delorme et al., 2004 ). However, in studies on consumer behavior and COVID-19, their presence is modest, where quantitative studies dominate.

Various factors can explain the preeminence of quantitative studies; however, this subsection addresses the key factor of technology. Specifically, the confluence of intensive use of technologies by consumers during COVID-19, and the body of knowledge accumulated before the pandemic on consumer behavior and the use and adoption of technologies. Hence, this body of knowledge created a solid foundation for quantitatively oriented consumer studies. However, the existing knowledge about consumer behavior and disruptive events did not provide a solid foundation since its extension is rather modest. ( Laato et al., 2020 ).

6.3 Reassessment of pre-COVID-19 knowledge on key topics of consumer behavior and recommendation for future studies

A crucial consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is the massive rise in the learning and use of technologies ( Baicu et al., 2020 : Sheth, 2020 ), which is unprecedented considering the global scale of the pandemic and its sustained duration. This massive and extensive learning of the use of technologies will have consequences in the validity of knowledge developed before the pandemic in key consumer behavior topics and technology use. Although there are various topics, this subsection will focus on two: Consumer segments in the use of technologies and the digital divide.

Before the pandemic, many studies in different countries apply various scales, including the technology readiness index scale ( Parasuraman and Colby, 2015 ), to gage consumer segments in technology markets. The studies yielded strong results on consumer segments and their sizes. Thus, considering the rapid adoption of technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic, an obvious question is how current this knowledge is. Hence, future studies can determine how the COVID-19 pandemic reconfigured consumer segments in the use of technologies, how they changed regarding their importance, and whether a revision of existing measuring instruments (scales) is necessary.

Moreover, the digital divide (i.e., the gaps in the access and use of technologies between different societal sectors) has also been extensively studied before COVID-19. For example, older and lower-income people used technology-based services to a much lesser degree ( Cruz-Cárdenas et al., 2019 ). The information is useful to design profitable and social marketing strategies. However, the pandemic-induced massive learning of technologies may leave out a part of society. Ultimately, future studies can focus on determining what happened to the digital gaps between social groups as an effect of the pandemic.

6.4 COVID-19 and the future: recommendations for practice and future studies