Japanese History: Edo Period Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Bibliography

The Edo period also known as the Tokugawa period is the period between 1603-1868 in the Japanese history when Japan was under the Tokugawa Shogunate rule who had divided the country into 300 regions known as Daimyos. Tokugawa leyasu officially opened the era on March, 24, 1603 while Tokugawa yoshinobu resigned on May, 3 1868 after the Meiji restoration. The Tokugawa family ruled Japan from their base in Edo (currently Tokyo). The post of Emperor was more ceremonial during the Edo era (Patricia 60).

Tokugawa leyasu supported foreign trade but he was also suspicious of the influence of the outsiders during the pre-Edo period; Japan underwent the Nanban trade era during which the intense interaction with the European powers took place, namely, economic and religious. Trade restrictions, Christian missionary execution and Spanish expulsion were some of the restrictions that were enforced. The Closed Country Edict in 1635 was the climax of all the restrictions because of the following:

- Set highly strict regulations to minimize the movement of people into and out of the Japanese territory; death penalty was the consequence.

- Catholicism and all Christian practices were forbidden; Missionaries were also barred from entering Japan, and harsh sentences were drawn for those who entered.

- Trade restrictions were set; trade along ports was consequently limited. Portuguese relations with Japan were completely cut off (Alfred 138).

The Edo period was marked by the urban culture in Japan, for instance, Edo became the largest city on earth during those times with a population of 1.2 million residents as compared to the second largest place, London, with 800,000 residents. The period also experienced the rise of entertainment culture such as theaters or humorous novels.

Ordinary residents were also able to gain access to print media following the polychrome woodblocks development. People were also interested in learning more about Europe and all its sciences, commonly known as “Dutch learning” despite the minimal contact between Japan and the Western world (Alfred 100).

Arrival of Matthew Calbraith Perry and his four-ship fleet along the Edo Bay in July 1853 marked the end of the seclusion period in Japan. Japan finally accepted Perry’s demands to ending seclusion and opening up to foreign trade, consequently, the Treaty of Kanagawa that opened-up two ports (Hakodate and the port of Shimoda) to foreign American ships was signed (Administration, United States. National Archives and Records 1-4).

Five years after the Treaty of Kanagawa, the Harris treaty was signed between Japan and the US. The Kanagawa treaty became a catalyst factor of internal conflicts, which were only solved after the Tokugawa shogunate’s fall; similar agreements were negotiated by European powers such as Russia, the United Kingdom and France. (William 4)

After 250 years rule over Japan, the Tokugawa Shogunate turned the Japanese nation into a united cohesive nation with the mushrooming of many urban centers across Japan, for example, Edo became the largest and most populated city on earth with 1.2 million residents; Japan also experienced some artistic as well as intellectual development during this period.

On the other hand, the seclusion policy undermined all the good things that are associated with the rule; it is a policy that consistently haunted the Tokugawa rule, and finally led to its fall as the Japanese opted for a more open Meiji restoration that allowed all forms of Western culture to freely penetrate into Japan without necessarily having to restrict them.

Administration, United States. National Archives and Records. The Treaty of Kanagawa: Setting the Stage for Japanese-American Relations. New York City: National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. Print.

Alfred J. Andrea, and James H. Overfield. The Human Record, Volume II: Sources of Global History: Since 1500. London: Cengage Learning, 2011. Print.

Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Anne Walthall, and James Palais. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Tokyo: Cengage Learning, 2008. Print.

William C. Middlebrooks. Beyond Pacifism: Why Japan Must Become a Normal Nation: Why Japan Must Become a Normal Nation. New York City: ABC-CLIO, 2008. Print.

- Hiroshima: Rising from the Ashes of Nuclear Destruction

- Tokugawa Settlements and Rule of Meiji in Japan

- Kitagawa and Gainsborough Artworks

- World History: A Peace to End All Peace by David Fromkin

- The Adventures of Ibn Battuta

- The Effects of the Korea Division on South Korea After the Korean War

- The Tale of a Great Journey: "The Rihla" by Ibn Battuta

- The Boxer Rebellion

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 20). Japanese History: Edo Period. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/

"Japanese History: Edo Period." IvyPanda , 20 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Japanese History: Edo Period'. 20 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Japanese History: Edo Period." November 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

1. IvyPanda . "Japanese History: Edo Period." November 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

IvyPanda . "Japanese History: Edo Period." November 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/edo-tokugawa-japan/.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Art of Asia

Course: art of asia > unit 4.

- Introduction to Japan

- Buddhism in Japan

- Zen Buddhism

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

- Japanese art: the formats of two-dimensional works

Jōmon period (c. 10,500 – c. 300 B.C.E.): grasping the world, creating a world

Yayoi period (300 b.c.e. - 300 c.e.): influential importations from the asian continent (i), asuka period (538-710): the introduction of buddhism, nara period (710-794): the influence of tang-dynasty chinese culture, heian period (794-1185): courtly refinement and poetic expression, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Environment

- Globalization

- Japanese Language

- Social Issues

Early Japan (50,000 BC - 710 AD)

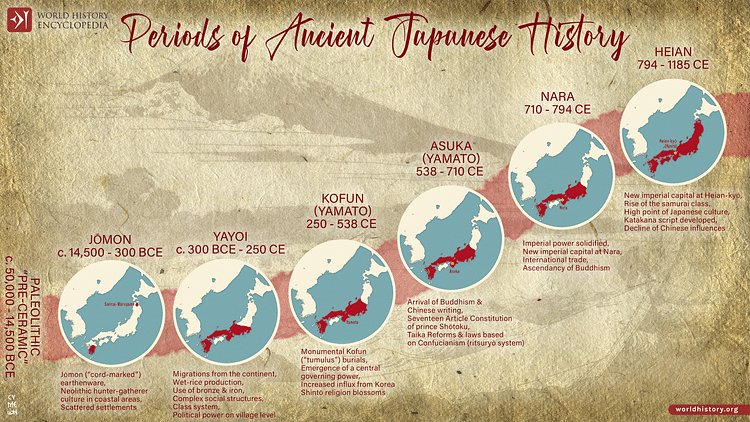

Editor's Note: This article was originally written for Japan Society's previous site for educator's, Journey through Japan," in 2003. Some of this material has been adapted from the author’s previous work in Martin Collcutt, Marius Jansen and Isao Kumakura, The Cultural Atlas of Japan , Facts on File, New York, 1988. Early Japanese history is traditionally divided into five major eras: the Paleolithic (c. 50,000 BC – c. 12,000BC), Jomon (c.11,000 BC to 300 BC), Yayoi (9,000 BC – 250 AD), Kofun (300 AD – 552 AD) and Yamato Periods (552-710 AD). While the dating of these periods is complex (see accompanying chart) and the cultures in any case tended to overlap, it is clear that early Japan underwent profound changes in each of these important periods.

1. The Paleolithic Period (c. 50,000 BC – c. 12,000 BC)

The first human beings to inhabit the islands we know as Japan appear to have been stone-age hunters from northeast Asia. Traveling in small groups and using stone-tipped weapons, they followed herds of wild animals including mammoths, elephants and deer across land bridges to Japan that had formed when the seas receded during the ice ages. While many believe that they came earlier, we know for certain that these hunters arrived in Japan at least as early as 35,000 BC. While the tools prior to that time are so crude that there is some debate over whether they were made by humans, surviving late Paleolithic artifacts include finely made blade tools similar to groups in Siberia and the rest of Eurasia, and axes made from ground stone. Since no pottery has yet been discovered, on the other hand, the Paleolithic Period in Japan is also sometimes referred to as the “pre-ceramic” (sendoki) period. This helps distinguish its inhabitants from those of the following eras. Research in this period has been complicated by the fact that an amateur archeologist named Fujimura Shin’ichi was caught “salting” various sites with alleged very old Paleolithic artifacts. Fujimura’s crime reflected not only his own desire to become famous, but also a Japanese fascination with the origins of the Japanese people and Japanese society. In Japan, the emphasis is on “the older the better,” especially if Japanese origins in any field predate Chinese or Korean developments. Fujimura’s “discoveries” thus fueled a rapidly developing “early Paleolithic” boom that sold newspapers and books and created a self-satisfied stir among ordinary people. All this helps to explain why neither the media (at first) nor archeological specialists saw through the fraud. In perpetuating his fraud, in other words, Fujimura was catering to the sense of Japanese narcissism and exceptionalism (nihonjin-ron) that is not very far beneath the surface of contemporary Japanese public opinion.

2. The Jomon Period (c. 11,000 BC – c. 300 BC)

About 20,000 years ago, the world’s fourth (and most recent) ice age ended. As the climate warmed, the polar ice caps melted and the sea levels rose. The land bridges that had provided walkways for such Paleolithic inhabitants of Japan as giant woolly mammoths, deer and humans were submerged for the final time. The islands of Honshu and Hokkaido were again separated, and Japan was once more isolated geographically. As Japan became hotter (reaching its peak about 3,000 BC), animals such as the wooly mammoth that had traditionally been hunted died out, but fortunately other plants and animals did better, and new, more sophisticated civilization began to emerge. This new stage in Japanese history is known as the Jomon (literally “cord pattern”) period because it is characterized by the appearance of earthenware pottery that often decorated with marks and swirling designs impressed by sticks, bamboo, vines or rope. The pots were fired in open pits at fairly low temperatures. Thousands of different pots have been found, but the earliest ones (12,000 BC – 5,000 BC) typically had rounded or pointed bottoms so that they could easily be stuck into the ground or in the ashes of a cooking fire. The pottery of this sort is the earliest pottery yet to be found in the world. Flat bottomed pots became common by the so-called Early Jomon period (5,500 BC – 2,500 BC), perhaps indicating that they were now used indoors on packed earthen floors rather than looser ashes or dirt. Middle Jomon (3,500 BC – 2,500 BC) and Late Jomon (2,500 BC – 1,500 BC) typically had elaborate designs. By later Jomon, large stone jars were made, perhaps for infant burial and religious offerings, while carved stone and clay figures known as dogu became increasingly elaborate. Many of these look like pregnant females, and hence were undoubtedly meant to pray for fertility and a good harvest. Stone fertility symbols have also been found. Unlike Neolithic humans in China and other cultural centers, the Paleolithic and Jomon period inhabitants of Japan subsisted primarily by hunting, fishing and gathering rather than settled agriculture. They may have cultivated some millet and herbs, but most likely they simply knew where to find and gather edible plants, and how to help preserve their food with salt. They also lived on nuts, fruit, roots, deer, wild boar and, where available, sea food. Obsidian (a glass-like stone) was a prized material for arrowheads. In the early period, individual hunters prowled for game, but soon bands of hunters were formed. The dog, the only domesticated animal known to the Jomon Japanese, joined in the chase. The Jomon people typically lived in small villages of six to ten dwellings per village. The standard house was a pit scooped in the earth with a makeshift grass or brush-wood roof held up by five or six posts, and an interior central fireplace with stone slabs. Each dwelling was large enough to accommodate between four and eight persons, and most settlements were at least semi-permanent. Most communities probably tried to be self-sufficient, but there was some local or regional exchange, with, for example, salt from the coastal regions being traded for stone (for tools and arrowheads) from the mountains. In Late Jomon communities (2,500 BC – 1,500 BC) there are house pits considerably larger than their neighbors. These may have been the homes of village chiefs, or places of worship for one or more villages. Archeologists have estimated the population of Jomon Japan at between 125,000 and 250,000, with the peak population about 5,000 BC and then declining. Skeletal remains suggest that the adults were about five feet six inches tall or quite high for human beings of this period. They decorated themselves with lacquered combs, bone hairpins, shell earrings and other ornaments. Life expectancy was probably about 30 years, with death rates highest among new born and those over forty. While some linguists have detected traces of Southeast Asian languages in modern Japanese speech, it seems likely that the language the Jomon people spoke was related mainly to Korean, Chinese and other Altaic (i.e. Mongolian, Turkish) languages. By the end of this period, in sum, the Jomon Japanese clearly had a complex community life.

In 1884, some distinctive pottery – clearly different in style and technique from Jomon pots – was unearthed in the Yayoi district of modern Tokyo. This district gave its name to a relatively brief but decisive period of Japanese culture in which Late Jomon culture was overlaid with a new and more advanced culture based not only on new pottery forms, but also the mining, smelting and casting of bronze and iron, and the irrigation and cultivation of rice. Yayoi culture varied by region, but overall was a culture unique to Japan. It has been traditionally dated from 300 BC to 300 AD, but scholars now think that it developed from at least 800 or 900 BC to 250 AD. Rice cultivation was one characteristic of the period. Rice had been grown in the Yangtze River basin in China from at least 5000 BC and in Korea from about 1500 BC, but apparently did not reach Japan until about 300 AD. Probably small groups of immigrants from the continent brought rice cultivation techniques to Japan where they and the Jomon peoples began to prepare special fields that had ample supplies of water and develop the necessary seeding, weeding and harvesting skills. The earliest fields were natural wetlands, but gradually the Yayoi people learned to construct irrigation canals that could supply the right amount of water. To round out their diet, the Yayoi people also gathered wild plants, cultivated fruit, hunted and fished. The Yayoi period also saw the extensive use of metal. Practical iron tools from Korea (such as axes and knives) have been found in the oldest Yayoi sites in the western part of Japan and even in a Jomon site from the same period in the northern island of Hokkaido. Ritual bronze objects such as mirrors, swords and spears also came from China and Korea. Eventually the Yayoi people learned to mine, smelt and produce these items on their own. One example of this local manufacture was the bronze, bell shaped objects known as dotaku. The idea for these objects may have come from the continent, but they quickly developed into a uniquely Japanese style. They appear to have symbolized divine spirits, and hence to have been used for religious fertility symbols. Yayoi pottery also reflected technological improvements. The pots were normally fired at higher temperatures (850 degrees Celsius or 1500+ degrees Fahrenheit) than was Jomon pottery. Unlike Jomon pottery, the surfaces of these pots were generally smooth with geometric designs. There were many different kinds of this pottery, ranging from cooking and storage pots to more formal vessels used for burial and religious purposes, but it was clear that all were made by quite sophisticated artisans. The Yayoi people looked rather like the inhabitants of Northeast Asia and hence more closely resembled modern Japanese than did the more South China and Southeast Asia looking Jomon. Some of the differences may have been due to a better diet, but most likely the slow trickle of immigrants moving from the more northern areas of Asia through Korea to Japan greatly increased in this period. They lived in villages that were in many ways similar to those around the lower Yangtze River in China. As many as 30 households may have lived together at one time in houses that were oval in shape and over 48 square meters (1500+ square feet) in size. These houses had roofs of thatched material that were supported by heavy beams and posts. The floors were set into the ground, but protected from flood damage by earthen walls. There was usually a hearth for cooking and warmth in the center. Cultivated rice and other foods could be stored in jars or in specially designed storehouses. Wooden fencing marked off their fields, some of which were larger that 400 square meters or more than 4,300 square feet. Judging from implements found in the area, cultivation was done with stone reapers, wooden rakes and hoes. As the population increased and more conflicts over land and water rights occurred, Yayoi village leaders gradually evolved into village chiefs, villages coalesced into chiefdoms, and fighting between chiefdoms became common. By the last century of the Yayoi (150 AD – 250 AD), confederations of chiefdoms had developed into political bodies that ultimately laid the foundation for the ancient state. One of these confederations was a legendary “nation” known as Yamatai-koku (the country of Yamatai). Chinese records indicate that this “nation” was ruled over – at least religiously -- by a priestess known a Himiko (literally “Daughter of the Sun”). She is said to have sent an envoy to China in 238 BC and to have received a gift from China in return. Early chronicles suggest that she may have been the Empress Jingu, a powerful ruler who Japanese sources claim lived at the same time. The location of her capital of Yamatai is also unclear, as over 50 different sites in northern Kyushu and the Kansai (Osaka-Kyoto) area on the main island of Honshu have been suggested. While little is certain about both the capital and its rulers, in sum, it does appear that Yayoi Japan was gradually developing into a strong and sophisticated state.

4. The Kofun Period (300 AD – 552 AD)

By 250 AD, the building of large tombs became so strikingly different from what had gone on before that the period from around 250 AD to the introduction of Buddhism in 552 AD is now commonly called the Kofun or “Old Tomb” period. These tombs reflect the power of an extensive political regime. They have been found from southern Kyushu to northern Honshu. Shapes varied from round to square to “keyhole” shaped. One striking example, the alleged tomb of Emperor Nintoku (who may have ruled in the early 400’s) near modern Osaka, covers over 80 acres and hence -- except for the extraordinary tomb of the first emperor of the Qin Dynasty (c. 200 BC) in China -- is bigger than all of the tombs of the world. As might be expected from the size and sophistication of these tombs, a great many personal effects have been recovered from the inside including jewelry, mirrors, and tools that were meant to accompany the dead spirits in an afterlife. Because many tombs from the 5th and 6th century also contain horse bones and trappings, it seems probable that a horse riding and militarily sophisticated aristocracy may have come into Japan at this time, either by a sudden invasion or a gradual process. A particularly rich art form known as haniwa also developed in this period. These gradually developed from simple cylinders into complex clay figures of important members of the traditional society as well as buildings. Carefully laid out, again in hopes of being useful or bringing comfort to the spirits, thousands of beautifully made haniwa have survived to this day.

The Yamato Period (552 AD -710 AD)

The number and size of these tombs suggest that by the 5th and 6th centuries, Japanese society was becoming more sophisticated. As it did so, a shifting confederation of intermarried tribal chieftains began in this period to call itself the Yamato people. “Yamato” refers both to the area around Nara and to the clan that eventually founded the present day imperial line in Japan. Particularly in literary works, the word is also often used to refer to Japan as a whole. While historians are still divided on whether these chieftains came from Korean immigrant families, the Yamato chieftains themselves claimed descent from the Sun Goddess Amaterasu. They used this religious symbol, their military supremacy, intermarriage and the awarding of titles to extend gradually their power from the Kansai (Kyoto-Osaka-Nara) area to other parts of Japan. The Yamato chieftains were called Great Kings (okio or okimi), one of which apparently claimed the right to be the most powerful king by the 5th or 6th century. From this time on to the present, blood ties were a powerful factor in the imperial family’s power. Yamato society was organized into clans (uji), occupation groups and slaves. Because of their traditional power, loyalty and service the Yamato court, the Soga, Mononobe and Nakatomi clans were given special titles and allowed to be in attendance at the newly forming imperial court. There they made themselves useful by performing both state duties and religious worship. Beneath them, the so-called occupation groups (be) produced special products (such as paper, cloth, arms or agricultural products) or performed other hereditary services such as grooms or scribes. Less skilled or pleasant tasks, such as burying the dead, were performed by slaves (be). Although Korean historians play down the possibility, Japanese historians believe that the Yamato dynasty established diplomatic relations with the kingdom of Packche in 366 AD and maintained a foothold in Korea until 562. The dynasty then stayed allied with Packche until Packche and its Yamato allies were soundly defeated in 663. From this point, unable to secure their influence by military means, Japanese rulers turned to cultural and diplomatic contacts with China in what can be described as a great effort at domestic self-strengthening along Chinese lines. By the 6th century, great tombs were still being built, but Japanese society was being transformed by new cultural elements from the continent, the most important of which was Buddhism. Buddhism probably began to filter into Yamato via Korean immigrants in the late 5th and 6th century. The faith was not taken up very seriously in court circles, however, until the king of Paekche sent in 552 (some sources say 538) Buddhist texts and a gilt statue to the Yamato ruler with words of praise for this allegedly superior faith. The Paekche gift caused conflict in the court both because some did not support an alliance with Paekche and because some worried about the wisdom of adopting a new and alien religion. Several powerful clans (uji), led by the Nakatomi (who were in charge of the traditional rituals) and the Mononobe (who were military specialists) opposed the introduction of this foreign faith, while others, led by the powerful Soga family, argued for acceptance. Buddhism suffered a set back when traditionalists blamed an epidemic on the new faith, but the Soga’s victory over the Mononobe in 587 assured fuller acceptance of Buddhism. By 593, the Soga has succeeded in placing a relative on the throne as Empress Suiko (ruled 593-628), and she in turn had named Prince Shotoku (Shotoku Taishi, 572-622) as Regent. An enthusiastic promulgator of Buddhism and patron saint of Buddhists, he is said to have founded the great Horyu-ji temple near Nara and to have written the famous 17 article “constitution” (actually moral injunctions) of 604, the second article of which asks his subjects to respect the teachings of the Buddha. He is also said to have been a wonderful Buddhist scholar. (The religious significance of this new faith, as well as the ways in which Buddhism eventually meshed with traditional faiths, is explained in the separate essay on religion, Japanese Religions to 710AD). Shotoku’s constitution also used the Chinese imperial model to build a stronger imperial state for the Yamato (and now Soga) rulers. A new series of court ranks, symbolized by the wearing of twelve different caps, was intended to promote men of ability and hence weaken the hereditary power of the traditional court chieftains. The document also stressed loyalty, harmony, dedication and ability in government as ideals to be realized in Japanese political life. “When you receive the imperial commands, fail not scrupulously to obey them,” Article 3 declares. “The lord is Heaven. The vassal is earth. Heaven overspreads. The earth upbears.” In another famous statement, he insulted the Chinese sense of cultural superiority by addressing greetings “from the son of Heaven in the land where the sun rises to the son of Heaven in the land where the sun sets.” Shotoku’s statement reflected both a growing sense of Japan’s unique national identity and his sense that the Imperial family held a special place in Japan, above and beyond that of the other, more ordinary clans (uji). Given the power of the Soga family, Shotoku was not able to implement all – or perhaps even many – of his reforms, yet for all that he did set standards to which future rulers, soon to be called “Emperors” (tenno), could aspire. After Prince Shotoku died, Prince Naka no Oe and Nakatomi no Kamatari, the head of one of the rival Nakatomi clan (uji), in 645 led a coup in which they killed the head of the Soga and his son. Both Buddhism and Shotoku’s political ideals were still respected, but a new Emperor, Kotoku, was installed, the capital was moved to Naniwa (modern Osaka), and the era name was changed to Taika (literally “great change”). Nakatomi no Kamatari became a powerful figure in court, while Naka no Oe later became an Emperor himself. In 646, these leaders issued the first of a number of edicts that formed the so-called Taika Reforms. The declared aims of the coup leaders were to recover power for the emperor (tenno), and to follow Prince Shotoku’s example by using Chinese administrative codes to create a just and effective administration. Land tenure was also supposed to follow the Chinese ideal of belonging to the Emperor and hence being reallocated from time to time to meet the needs of the peasants. The occupation groups that had formerly supported the clans (uji) were abolished, and the provincial clan chieftains were co-opted into the system by being granted title and offices in the new administrative districts. A new tax system, including taxes in kind, labor or military service was imposed to pay for the new capital, a central bureaucracy, roads, post stations and the military establishment. This in turn called for regular census taking. As was the case with Prince Shotoku’s “constitution,” the proposed reforms were not easily implemented. Yet again like Prince Shotoku’s constitution, the “great changes” proposed in the Taika reforms had set a course of future reforms that were slowly implemented over time. As new Chinese influenced penal and administrative codes (ritsu and ryo) such as the Taiho ritsuryo of 702 were promulgated, Japan evolved steadily into a new and more powerful imperial state.

Receive Website Updates

Please complete the following to receive notification when new materials are added to the website.

Ancient Japan

Ancient Japan has made unique contributions to world culture which include the Shinto religion and its architecture , distinctive art objects such as haniwa figurines, the oldest pottery vessels in the world, the largest wooden buildings anywhere at their time of construction, and many literary classics including the world's first novel. Although Japan was significantly influenced by China and Korea , the islands were never subject to foreign political control and so were free to select those ideas which appealed to them, adapt them how they wished, and to continue with their indigenous cultural practices to create a unique approach to government, religion , and the arts.

Japan in Mythology

In Shinto mythology, the Japanese islands were created by the gods Izanami and Izanagi when they dipped a jewelled spear into the primordial sea. They also created over 800 kami or spirits, chief amongst which was the sun goddess Amaterasu , and so created the deities of Shinto, the indigenous religion of ancient Japan. Amaterasu's grandson Ninigi became the first ruler, and he was the great-grandfather of Japan's first emperor, the semi-legendary Emperor Jimmu (r. 660-585 BCE). Thus, a divine link was established between all subsequent emperors and the gods.

The Jomon Period

The first historical period of Japan is the Jomon Period which covers c. 14,500 to c. 300 BCE (although both the start and end dates for this period are disputed). The period's name derives from the distinctive pottery produced at that time, the oldest vessels in the world, which has simple rope-like decoration or jomon . It is the appearance of this pottery that marks the end of the previous period, the Palaeolithic Age (30,000 years ago) when people crossed now lost land bridges from mainland Asia to the northern and southern Japanese islands. They then spread to the four main islands of Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, and eventually to the several hundred smaller islands that make up Japan. The production of pottery does not necessarily signify communities lived in fixed settlements, and for the majority of this time period, people would have continued to live a hunter-gatherer existence using wood and stone tools.

The first signs of agriculture appear c. 5000 BCE and the earliest known settlement at Sannai-Maruyama dates to c. 3500 BCE and lasts until c. 2000 BCE. Populations seem to have concentrated in coastal areas and numbered somewhere between 100,000 and 150,000 across the islands. There is evidence of rice c. 1250 BCE, but its cultivation was likely not until c. 800 BCE. The first evidence of growing rice in wet fields dates to c. 600 BCE. Skeletons from the period indicate people of muscular build with wide square faces and an average height of 1.52 m (5 ft) for females and 1.60 m (5 ft 3 inches) for males. Genetic and cranial studies suggest that Jomon people are the ancestors of the present-day minority group, the Ainu.

The most common burial type of the period is in pits, sometimes lined with stone slabs, which contain one or more individuals. Other types of burial include single individuals in jars and large pits containing up to 100 skeletons. Artefacts discovered relating to the Jomon Period include clay and stone human-shaped figurines, clay masks, stone rods, and clay, stone, and jade jewellery (beads and earrings). Archaeology has also revealed the Jomon built ritual structures of stone circles, lines of stones forming arrow shapes, and single tall standing stones surrounded by a cluster of smaller stones.

The Yayoi Period

The Yayoi Period covers c. 300 BCE to c. 250 CE, although, as mentioned above, the start date is being pushed back as more discoveries are made in archaeology. The name derives from the reddish pottery first found in the Yayoi district of Tokyo, which indicated a development from the pottery of the Jomon Period. From around 400 BCE (or even earlier) migrants began to arrive from continental Asia, especially the Korean peninsula, probably driven by the wars caused by Chinese expansion and between rival kingdoms.

The new arrivals conquered or integrated with the indigenous peoples, as indicated by genetic evidence, and they brought with them new pottery, bronze , iron and improved metalworking techniques which produced more efficient farming tools and better weaponry and armour.

With improved agricultural management, society was able to develop with specialised trades and professions (and consequent markets for trade appeared), ritual practices using such distinctive items as dotaku bronze bells, social classes of varying prosperity, and an established ruling class who governed over alliances of clan groups which eventually formed small kingdoms. Chinese sources note the frequency of warfare in Japan between rival kingdoms, and archaeology has revealed the remains of fortified villages. The population of Japan by the end of the period may have been as high as 4.5 million.

Japan was beginning its first attempts at international relations by the end of the period. Envoys and tribute were sent to the Chinese commanderies in northern Korea by the Wa, as the confederation of small states in southern and western Japan were then known, the most important of which was Yamato. These missions are recorded in 57 and 107 CE. One Japanese ruler known to have sent embassies to Chinese territory (238, 243, and c. 248 CE) and the most famous figure of the period was Queen Himiko (r. c.189-248 CE). Ruling over 100 kingdoms (or perhaps just the monarch of the most powerful one), the queen never married and lived in a castle served by 1,000 women . Himiko was also a shamaness, embodying the dual role of ruler and high priest, which would have been common in the period. That a woman could perform either of both roles is an indicator of the more favourable attitude to women in ancient Japan before Chinese culture became more influential from the 7th century CE.

The Kofun Period

The Kofun Period covers c. 250 to 538 CE and is named after the large burial mounds which were constructed at that time. Sometimes the period is referred to as the Yamato Period (c. 250-710 CE) as that was then the dominant state or region, either incorporating rival regions into its own domain or, as in the case of chief rival Izumo, conquering through warfare. The exact location of Yamato is not known for certain, but most historians agree it was in the Nara region.

From the 4th century CE there was a significant influx of people from the Korean peninsula, especially the Baekje ( Paekche ) kingdom and Gaya ( Kaya ) Confederation. These may have been the horse-riding warriors of the controversial 'horse-rider theory' which claims that Japan was conquered by Koreans and was no more than a vassal state. It seems unlikely a total conquest did actually occur (and some sources controversially suggest the reverse and that Japan had established a colony in southern Korea), but it is more certain that Koreans held high government positions and even mixed with the imperial bloodline. Whatever the political relationship between Korea and Japan at this time, there was certainly an influx of Korean manufactured goods, raw materials such as iron, and cultural ideas which came via Korean teachers, scholars, and artists travelling to Japan. They brought with them elements of Chinese culture such as writing , classic Confucian texts, Buddhism , weaving, and irrigation, as well as Korean ideas in architecture. There were also envoys to China in 425 CE, 478 CE, and then 11 more up to 502 CE. Yamato Japan was establishing an international diplomatic presence.

The large burial mounds known as kofun are another link with mainland Asia as they were built for the elite in various states of the Korean peninsula. There are over 20,000 mounds across Japan, and they usually have a keyhole shape when seen from above; the largest examples measure several hundred metres across and are surrounded by a moat. Many of the tombs contain horse trappings which are not seen in previous burials and which add weight to contact with the Asian continental mainland. Another feature of kofun was the placement of large terracotta figurines of humans, animals, and even buildings called haniwa around and on top them, probably to act as guardians.

Kofun , built on a grander scale as time went on, are indicators that the Yamato rulers could command tremendous resources - both human and material. Ruling with a mixture of force and alliances with important clans or uji consolidated by intermarriages, the Yamato elite were well on their way to creating a centralised state proper. What was needed now was a better model of government with a fully functioning bureaucratic apparatus, and it would come from China.

The Asuka Period

The Asuka Period covers 538 to 710 CE. The name derives from the capital at that time, Asuka, located in the northern Nara prefecture. In 645 CE the capital was moved to Naniwa, and between 694 and 710 CE it was at Fujiwarakyo. Now we see the first firmly established historical emperor (as opposed to legendary or mythical rulers), Emperor Kimmei, who was 29th in the imperial line (r. 531-539 CE to 571 CE). The most significant ruler was Prince Shotoku who was regent until his death in 622 CE. Shotoku is credited with reforming and centralising government on the Chinese model by, amongst other things, creating his Seventeen Article Constitution , rooting out corruption and encouraging greater ties with China.

The next major political event of the Asuka period occurred in 645 CE when the founder of the Fujiwara clan , Fujiwara no Kamatari, staged a coup which took over power from the then dominant Soga clan. The new government was remodelled, again along Chinese lines, in a series of lasting reforms, known as the Taika Reforms, in which land was nationalised, taxes were to be paid in kind instead of labour, social ranks were recategorised, civil service entrance examinations were introduced, law codes were written, and the absolute authority of the emperor was established. Kamatari was made the emperor's senior minister and given the surname Fujiwara. This was the beginning of one of Japan's most powerful clans who would monopolise government until the 12th century CE.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Emperor Temmu (r. 672-686 CE) pruned the extended royal family so that only direct descendants could claim any right to the imperial throne in a move which would create more rival clan groups. Temmu selected Fujiwarakyo as the first proper Japanese capital which had a palace in the Chinese style and streets laid out in a regular grid pattern.

Perhaps the most significant development of the Asuka Period was not political but religious, with the introduction of Buddhism to Japan sometime in the 6th century CE, traditionally in 552 CE. It was officially adopted by Emperor Yomei and further encouraged by Prince Shotoku who built several impressive temples such as Horyuji . Buddhism was generally welcomed by Japan's elite as it helped raise Japan's cultural status as a developed nation in the eyes of their powerful neighbours Korea and China.

Shotoku had sent official embassies to the Sui court in China from c. 607 CE and they continued throughout the 7th century CE. However, relations with Japan's neighbours were not always amicable. The Silla kingdom overran its neighbour Baekje in 660 CE with the help of a massive Chinese Tang naval force. A rebel Baekje force persuaded Japan to send 800 ships to aid their attempt to regain control of their kingdom, but the joint force was defeated at the Battle of Baekgang in 663 CE. The success of the Unified Silla Kingdom resulted in another wave of immigrants entering Japan from the collapsed Baekje and Goguryeo kingdoms.

The arts, meanwhile, flourished and have given rise to an alternative name, the Suiko Period (552-645 CE) after Empress Suiko (r. 592-628 CE). Literature and music following Chinese models were actively promoted by the court and artists were given tax reliefs.

The Nara Period

The Nara Period covers 710 to 794 CE and is so called because the capital was at Nara (Heijokyo) during that time and then moved briefly to Nagaokakyo in 784 CE. The capital was built on the Chinese model of Chang -an, the Tang capital and so had a regular and well-defined grid layout, and public buildings familiar to Chinese architecture . A sprawling royal palace, the Heijo, was built and the state bureaucracy was expanded to some 7,000 civil servants. The total population of Nara may have been as high as 200,000 by the end of the period.

Control of the central government over the provinces was increased by a heightened military presence throughout the islands of Japan, and Buddhism was further spread by Emperor Shomu's (r. 724-749 CE) project of building a temple in every province, a plan that raised taxation to brutal levels. Major temples were built at Nara, too, such as the Todaiji (752 CE) with its Great Buddha Hall, the largest wooden building in the world containing the largest bronze sculpture of the Buddha in the world. Shinto was represented by, amongst others, the Kasuga Taisha shrine in the forests outside the capital (710 or 768 CE) and the Fushimi Inari Taisha shrine (711 CE) near Kyoto.

Japan also became more ambitious abroad and forged a strong relationship with Balhae ( Parhae ), the state in northern Korea and Manchuria. Japan sent 13 diplomatic embassies and Balhae 35 in return over the decades. Trade flourished with Japan exporting textiles and Balhae furs, silk , and hemp cloth. The two states plotted to invade the Unified Silla Kingdom, which now controlled the Korean peninsula, with a joint army with an attack in 733 CE involving a large Japanese fleet, but it came to nothing. Then a planned invasion of 762 CE never got off the generals' map board.

The Nara Period produced arguably the two most famous and important works of Japanese literature ever written: the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki histories with their creation myths, Shinto gods, and royal genealogies. There was also the Manyoshu poetry anthology, Japan's first of many, which was compiled c. 760 CE.

In contrast to the arts, the ordinary populace did anything but flourish. Agriculture still depended on primitive tools, not enough land was prepared for crops, and irrigation techniques were insufficient to prevent frequent crop failures and outbreaks of famine. Thus, most peasants preferred the greater security of working for landed aristocrats. On top of these woes, there were smallpox epidemics in 735 and 737 CE, which historians calculate reduced the country's population by 25-35%.

The court, besides facing these natural disasters, was low on funds after too many landed aristocrats and temples were given exemption from tax. Nara, too, was beset by internal conflicts for favours and positions amongst the aristocracy and politics was being unduly influenced by the Buddhist temples dotted around the city . Consequently, Emperor Kammu (r. 781-806 CE) changed the capital yet again, a move which heralded the next Golden period of Japanese history.

The Heian Period

The Heian Period covers 794 to 1185 CE and is named after the capital during that time, Heiankyo , known today as Kyoto. The new capital was laid out on a regular grid plan. The city had a wide central avenue and, like Nara before it, architecture followed Chinese models, at least for public buildings. The city had palaces for the aristocracy, and a large pleasure park was built south of the royal palace (Daidairi). No Heian buildings survive today except the Shishin-den (Audience Hall), which was burnt down but faithfully reconstructed, and the Daigoku-den (Hall of State), which suffered a similar fate and was rebuilt on a smaller scale at the Heian Shrine. From the 11th century CE the city's longtime informal name meaning simply 'the capital city' was officially adopted: Kyoto. It would remain the capital of Japan for a thousand years.

Kyoto was the centre of a government which consisted of the emperor, his high ministers, a council of state, and eight ministries, which, with the help of an extensive bureaucracy, ruled over some 7,000,000 people spread over 68 provinces. The vast majority of Japan's population worked the land, either for themselves or the estates of others. Burdened by banditry and excessive taxation, rebellions were not uncommon. By the 12th century CE 50% of land was held in private estates ( shoen ), and many of these, given special dispensation through favours or due to religious reasons, were exempt from paying tax, causing a serious dent in the state's finances.

At court the emperor, although still considered divine, became sidelined by powerful bureaucrats who all came from one family: the Fujiwara clan. Further weakening the royal position was the fact that many emperors took the throne as children and so were governed by a regent ( Sessho ), usually a representative of the Fujiwara family. When the emperor reached adulthood, he was still advised by a new position, the Kampaku , which ensured the Fujiwara still pulled the political strings of court. Emperor Shirakawa (r. 1073-1087 CE) attempted to assert his independence from the Fujiwara by abdicating in 1087 CE and allowing his son Horikawa to reign under his supervision. This strategy of 'retired' emperors still, in effect, governing, became known as 'cloistered government' ( insei ) as the emperor usually remained behind closed doors in a monastery. It added another wheel to the already complex machine of government.

Buddhism continued its dominance, helped by such noted scholar monks as Kukai (774-835 CE) and Saicho (767-822 CE), who both brought ideas and texts from China and founded the Shingon and Tendai Buddhist sects respectively. At the same time, Confucian and Taoist principles continued to be influential in government and the old Shinto and animist beliefs continued to hold sway over the general populace.

In foreign affairs, after 838 CE Japan became somewhat isolationist without any necessity to defend its borders or embark on territorial conquest. However, sporadic trade and cultural exchanges continued with China, as before. Goods imported from China included medicines, worked silk fabrics, books, ceramics, weapons, and musical instruments while Japan sent in return pearls, gold dust, amber , raw silk, and gilt lacquerware. Monks, scholars, students, musicians, and artists were sent to see what they could learn from the still more advanced culture of China.

The period is noted for its cultural achievements, which included the creation of a Japanese writing ( kana ) using Chinese characters, mostly phonetically, which permitted the production of the world's first novel, the Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (c. 1020 CE), and several noted diaries ( nikki ) written by court ladies, including The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon (c. 1002 CE). Another important work was the 905 CE Kokinshu poem anthology.

Visual arts were represented by screen paintings, hand scrolls of pictures and text ( e-maki ), and fine calligraphy. Painters and sculptors continued to use Buddhism as their inspiration, but gradually, a more wholly Japanese approach expanded the range of subject matter in art to ordinary people and places. A Japanese style, Yamato-e , developed in painting particularly, which distinguished it from Chinese works. It is characterised by more angular lines, the use of brighter colours and greater decorative details.

All of this artistic output at the capital was very fine, but in the provinces, new power-brokers were emerging. Left to their own devices and fuelled by blood from the minor nobility two important groups evolved: the Minamoto and Taira clans. With their own private armies of samurai they became important instruments in the hands of rival members of the Fujiwara clan's internal power struggle, which broke out in the 1156 CE Hogen Disturbance and the 1160 CE Heiji Disturbance.

The Taira eventually swept away the Fujiwara and all rivals, but in the Genpei War (1180-1185 CE), the Minamoto returned victorious, and at the war 's finale, the Battle of Dannoura, the Taira leader, Tomamori, and the young emperor Antoku committed suicide. The Minamoto clan leader Yoritomo was shortly after given the title of shogun by the emperor, and his rule would usher in the medieval chapter of Japanese history with the Kamakura Period (1185-1333 CE), also known as the Kamakura Shogunate, when Japanese government became dominated by the military.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation .

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Beasley, W.G. The Japanese Experience. University of California Press, 2017.

- Cali, J. Shinto Shrines. Latitude 20, 2012.

- Dougill, J. Japan's World Heritage Sites. Tuttle Publishing, 2014.

- Ebrey, P.B. Pre-Modern East Asia. Wadsworth Publishing, 2013.

- Henshall, K. Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945. Scarecrow Press, 2013.

- Sansom, G. A History of Japan to 1334 by George Sansom. Stanford University Press, 2017.

- Tsuda, N. A History of Japanese Art. Tuttle Publishing, 2009.

- Whitney Hall, J. The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What are 5 facts about ancient japan, is japan an ancient civilization, who were the first humans on japan, related content.

The History of Japanese Green Tea

Japanese Tea Ceremony

Jomon Period

Itsukushima Shrine

Free for the World, Supported by You

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Tuttle Publishing (2023) |

| , published by Armadillo (2014) |

| , published by Enthralling History (2022) |

| , published by Tuttle Publishing (1997) |

| , published by Cambridge University Press (1993) |

External Links

Cite this work.

Cartwright, M. (2017, June 09). Ancient Japan . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/Ancient_Japan/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Ancient Japan ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified June 09, 2017. https://www.worldhistory.org/Ancient_Japan/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Ancient Japan ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 09 Jun 2017. Web. 08 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 09 June 2017. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The enduring appeal of Japanese literature

- Early writings

- Origin of the tanka in the Kojiki

- The significance of the Man’yōshū

- Kamakura period (1192–1333)

- The Muromachi (1338–1573) and Azuchi-Momoyama (1574–1600) periods

- Early Tokugawa period (1603– c. 1770)

- Late Tokugawa period ( c. 1770–1867)

- Introduction of Western literature

- Western influences on poetry

- Revitalization of the tanka and haiku

- The novel between 1905 and 1941

- The postwar novel

- The modern drama

- Modern poetry

Japanese literature

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Japanese literature - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Japanese literature - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Japanese literature , the body of written works produced by Japanese authors in Japanese or, in its earliest beginnings, at a time when Japan had no written language, in the Chinese classical language .

Both in quantity and quality, Japanese literature ranks as one of the major literatures of the world, comparable in age, richness, and volume to English literature , though its course of development has been quite dissimilar. The surviving works comprise a literary tradition extending from the 7th century ce to the present; during all this time there was never a “dark age” devoid of literary production. Not only do poetry , the novel , and the drama have long histories in Japan, but some literary genres not so highly esteemed in other countries—including diaries , travel accounts , and books of random thoughts—are also prominent. A considerable body of writing by Japanese in the Chinese classical language, of much greater bulk and importance than comparable Latin writings by Englishmen, testifies to the Japanese literary indebtedness to China . Even the writings entirely in Japanese present an extraordinary variety of styles, which cannot be explained merely in terms of the natural evolution of the language. Some styles were patently influenced by the importance of Chinese vocabulary and syntax , but others developed in response to the internal requirements of the various genres, whether the terseness of haiku (a poem in 17 syllables) or the bombast of the dramatic recitation.

The difficulties of reading Japanese literature can hardly be exaggerated; even a specialist in one period is likely to have trouble deciphering a work from another period or genre . Japanese style has always favoured ambiguity , and the particles of speech necessary for easy comprehension of a statement are often omitted as unnecessary or as fussily precise. Sometimes the only clue to the subject or object of a sentence is the level of politeness in which the words are couched; for example, the verb mesu (meaning “to eat,” “to wear,” “to ride in a carriage,” etc.) designates merely an action performed by a person of quality. In many cases, ready comprehension of a simple sentence depends on a familiarity with the background of a particular period of history. The verb miru , “to see,” had overtones of “to have an affair with” or even “to marry” during the Heian period in the 10th and 11th centuries, when men were generally able to see women only after they had become intimate . The long period of Japanese isolation in the 17th and 18th centuries also tended to make the literature provincial, or intelligible only to persons sharing a common background; the phrase “some smoke rose noisily” ( kemuri tachisawagite ), for example, was all readers of the late 17th century needed to realize that an author was referring to the Great Fire of 1682 that ravaged the shogunal capital of Edo (the modern city of Tokyo ).

Despite the great difficulties arising from such idiosyncrasies of style, Japanese literature of all periods is exceptionally appealing to modern readers, whether read in the original or in translation. Because it is prevailingly subjective and coloured by an emotional rather than intellectual or moralistic tone, its themes have a universal quality almost unaffected by time. To read a diary by a court lady of the 10th century is still a moving experience, because she described with such honesty and intensity her deepest feelings that the modern-day reader forgets the chasm of history and changed social customs separating her world from today’s.

The “pure” Japanese language, untainted and unfertilized by Chinese influence, contained remarkably few words of an abstract nature. Just as English borrowed words such as morality , honesty , justice , and the like from the Continent, the Japanese borrowed these terms from China ; but if the Japanese language was lacking in the vocabulary appropriate to a Confucian essay , it could express almost infinite shadings of emotional content. A Japanese poet who was dissatisfied with the limitations imposed by his native language or who wished to describe unemotional subjects—whether the quiet outing of aged gentlemen to a riverside or the poet’s awareness of his insignificance as compared to the grandeur of the universe—naturally turned to writing poetry in Chinese. For the most part, however, Japanese writers, far from feeling dissatisfied with the limitations on expression imposed by their language, were convinced that virtuoso perfection in phrasing and an acute refinement of sentiment were more important to poetry than the voicing of intellectually satisfying concepts.

From the 16th century on, many words that had been excluded from Japanese poetry because of their foreign origins or their humble meanings, following the dictates of the “codes” of poetic diction established in the 10th century, were adopted by the practitioners of the haiku , originally an iconoclastic, popular verse form. These codes of poetic diction , accompanied by a considerable body of criticism , were the creation of an acute literary sensibility, fostered especially by the traditions of the court, and were usually composed by the leading poets or dramatists themselves. These codes exerted an inhibiting effect on new forms of literary composition , but they also helped to preserve a distinctively aristocratic tone.

The Japanese language itself also shaped poetic devices and forms. Japanese lacks a stress accent and meaningful rhymes (all words end in one of five simple vowels), two traditional features of poetry in the West. By contrast, poetry in Japanese is distinguished from prose mainly in that it consists of alternating lines of five and seven syllables ; however, if the intensity of emotional expression is low, this distinction alone cannot save a poem from dropping into prose. The difficulty of maintaining a high level of poetic intensity may account for the preference for short verse forms that could be polished with perfectionist care. But however moving a tanka (verse in 31 syllables) is, it clearly cannot fulfill some of the functions of longer poetic forms, and there are no Japanese equivalents to the great longer poems of Western literature , such as John Milton ’s Paradise Lost and Dante ’s The Divine Comedy . Instead, Japanese poets devoted their efforts to perfecting each syllable of their compositions , expanding the content of a tanka by suggestion and allusion , and prizing shadings of tone and diction more than originality or boldness of expression.

The fluid syntax of the prose affected not only style but content as well. Japanese sentences are sometimes of inordinate length, responding to the subjective turnings and twistings of the author’s thought, and smooth transitions from one statement to the next, rather than structural unity, are considered the mark of excellent prose. The longer works accordingly betray at times a lack of overall structure of the kind associated in the West with Greek concepts of literary form but consist instead of episodes linked chronologically or by other associations. The difficulty experienced by Japanese writers in organizing their impressions and perceptions into sustained works may explain the development of the diary and travel account , genres in which successive days or the successive stages of a journey provide a structure for otherwise unrelated descriptions. Japanese literature contains some of the world’s longest novels and plays, but its genius is most strikingly displayed in the shorter works, whether the tanka, the haiku, the Noh plays (also called No, or nō), or the poetic diaries.

Japanese literature absorbed much direct influence from China , but the relationship between the two literatures is complex. Although the Japanese have been criticized (even by some Japanese) for their imitations of Chinese examples, the earliest Japanese novels in fact antedate their Chinese counterparts by centuries, and Japanese theatre developed quite independently. Because the Chinese and Japanese languages are unrelated, Japanese poetry naturally took different forms, although Chinese poetic examples and literary theories were often in the minds of the Japanese poets. Japanese and Korean may be related languages, but Korean literary influence was negligible, though Koreans served an important function in transmitting Chinese literary and philosophical works to Japan. Poetry and prose written in the Korean language were unknown to the Japanese until relatively modern times.

From the 8th to the 19th century Chinese literature enjoyed greater prestige among educated Japanese than their own; but a love for the Japanese classics, especially those composed at the court in the 10th and 11th centuries, gradually spread among the entire people and influenced literary expression in every form, even the songs and tales composed by humble people totally removed from the aristocratic world portrayed in classical literature .

Site Content

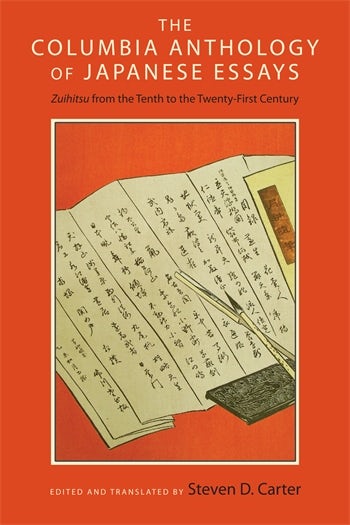

The columbia anthology of japanese essays.

Zuihitsu from the Tenth to the Twenty-First Century

Edited and translated by Steven D. Carter

Columbia University Press

Pub Date: October 2014

ISBN: 9780231167710

Format: Paperback

List Price: $45.00 £38.00

Shipping Options

Purchasing options are not available in this country.

ISBN: 9780231167703

Format: Hardcover

List Price: $135.00 £113.00

ISBN: 9780231537551

Format: E-book

List Price: $44.99 £38.00

- EPUB via the Columbia UP App

- PDF via the Columbia UP App

The focused ramble of the traditional Japanese essay format called zuihitsu (literally, 'following the brush') has appealed to writers of both genders, all ages, and every class in Japanese society. Highly personal, these essays contain dollops of philosophy, odd anecdotes, quiet reflection, and pronouncements on taste. In running alongside the main tracks of Japanese literature, this broad collection of zuihitsu brims with idiosyncratic interest. Liza Dalby, author of The Tale of Murasaki and East Wind Melts the Ice: A Memoir Through the Seasons

Savor a copy of The Columbia Anthology of Japanese Essays , and take a contemplative walk through the Japanese mind, full of poetic turns and pithy longings, ribald humor and lofty aspirations. Kris Kosaka, The Japan Times

Rich and highly enjoyable.... This evocative selection serves both as an excellent introduction to the genre for the English-speaking world and as a reminder that, no matter how distant or seemingly different the society, people's individual struggles, aspirations and aesthetics transcend their own times. Morgan Giles, Times Literary Supplement

Winner, 2016 2015-2016 Japan-United States Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature

About the Author

- Asian Fiction and Literature

- Asian Literature in Translation

- Asian Studies

- Asian Studies: Arts and Culture

- Asian Studies: Fiction and Literature

- Fiction and Literature

- Literary Studies

- Asian Studies: East Asian History

- History: East Asian History

Asuka Period (538 to 710)

• Japan, 500-1000 A.D. [Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art] "The introduction of Buddhism to the Japanese archipelago from China and Korea in the sixth century causes momentous changes amounting to a fundamentally different way of life for the Japanese. Along with the foreign faith, Japan establishes and maintains for 400 years close connections with the Chinese and Korean courts and adopts a more sophisticated culture." With a period overview, list of key events, and five related artworks.

• Asuka and Nara Periods [Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art] A short introduction, with images of three artworks in the museum's collection.

• Early Japan (50,000 BC - 710 AD) [About Japan: A Teacher's Resource] An overview of Japanese history from 50,000 BCE to 710 CE. Section 5 is about the Asuka period (called the Yamato period in this article).

• Powerful Soga clan in ancient Japan likely of Korean origin [Asahi Shimbun]

• Japan Rediscovers its Korean Past [New York Times]

Nara Period (710 to 794); Heian Period, (794 to 1185)

• Nara and Heian Japan (710 AD - 1185 AD) [About Japan: A Teacher's Resource] An overview of Japan's Nara and Heian periods. Discusses the Fujiwara family, their private estates, and the rise of the warrior.

• Heian Japan: An Introductory Essay [Program for Teaching East Asia, Center for Asian Studies, University of Colorado] Essay highlighting the key points of Japanese history during the Heian Period, including the moving of the capital from Nara, the turning away from Chinese models, the Fujiwara family and the Heian aristocracy, and Buddhism in Japan. Part of a larger unit for teaching the Heian Period through art.

Video Unit • Classical Japan [Asia for Educators] An introduction to Classical Japan covering the influence of Chinese culture on Classical Japan, the Imperial family, the Nara period, Buddhism, Shinto, the Japanese language, and Japanese poetry of the period. Featuring Columbia University professors Donald Keene, Carol Gluck, Haruo Shirane, and Paul Varley, and Asia Society President Emeritus Robert Oxnam. Section Topics:

• Todai-ji and the Shosoin Repository [Smart History] "When completed in the 740s, Tōdai-ji (or 'Great Eastern Temple') was the largest building project ever on Japanese soil. Its creation reflects the complex intermingling of Buddhism and politics in early Japan. When it was rebuilt in the twelfth century, it ushered in a new era of Shoguns and helped to found Japan's most celebrated school of sculpture. It was built to impress. Twice...The roots of Tōdai-ji are found in the arrival of Buddhism in Japan in the sixth century. Buddhism made its way from India along the Silk Route through Central Asia, China and Korea. Mahayana Buddhism was officially introduced to the Japanese Imperial court around 552 by an emissary from a Korean king who offered the Japanese Emperor Kimmei a gilded bronze statue of the Buddha, a copy of the Buddhist sutras (sacred writings) and a letter stating: 'This doctrine can create religious merit and retribution without measure and bounds and so lead on to a full appreciation of the highest wisdom.'"

• The Shosoin Repository and its Treasure (on the grounds of the Todai-ji) [Smart History] "In the Japanese city, Nara, on the northwest rear corner of Tōdai-ji Temple's Daibutsuden Hall stands a building largely unaltered since the 8th century...For almost 1200 years, until the twentieth century, it preserved in excellent condition approximately nine thousand artifacts from China, Southeast Asia, Iran, and the Middle East— a miscellany connecting ancient Japan to the cultural trade and artistic exchange of the Eurasian continent . While other collections worldwide hold treasures from the ancient Silk Roads, the Shōsōin is unique as a time capsule of the entire known world of its time—when Nara-period Japan glowed as a star in the brilliant cultural cosmos of Tang-dynasty China (618-907)."

• The Legends of Hachiman [Smith College Museum of Art] From protector of the imperial house, to protector of the Minamoto military house, to protector of the nation, the legend of the Shinto deity, Hachiman, evolved throughout Japanese history...Hachiman was established as the protector of the imperial house through several key events in the Nara period (710-794) . One of the most formative was Hachiman's role in the construction of the huge Buddha statue ( daibutsu ) in Nara. At the time, Emperor Shōmu (701-756) issued an edict to build state-sponsored Buddhist temples in each province in Japan in order to protect the realm. The most important of these was the temple in the capital of Nara, Tōdai-ji , the upmost symbol of national unity and imperial rule. Through an oracle, Hachiman promised the discovery of copper and gold for the casting of the huge Buddha statue that would be housed there. With the successful completion of the project, Hachiman was honored for his invaluable help with first court rank. In this way, Hachiman became a protector of the imperial house. The site provides background on the scrolls, suggestions for viewing a handscroll, and questions for discussion .

Katakana, Hiragana, Kanji

• The Japanese Language [Asia for Educators] This unit presents an overview of the Japanese language, both spoken and written. It includes a chart of the Japanese syllabary and discussion questions/student exercises.

• Japanese Syllabaries [Asia for Educators] This unit provides an opportunity for students to practice writing both Japanese syllabaries — katakana and hiragana .

• Chinese Characters ( Kanji ) [Asia for Educators] This unit provides the opportunity for students to read and write kanji , the Chinese characters used in the Japanese writing system.

Also see the Video Unit on Classical Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Nara and Heian Periods) for more about the Japanese use of the Chinese writing system .

Buddhism in Japan

• Japanese Buddhism [The Art of Asia, Minneapolis Institute of Arts] A transcript of a video unit on Buddhism in Japan. See also the original media in flash.

• Buddhism in Japan [Asia Society] "A short history of Buddhism, with special focus on its introduction and development in Japan. Includes an exploration of Zen Buddhism and art imagery."

• Buddhism and Japanese Aesthetics [ExEAS, Columbia University] This unit provides a general introduction to three aesthetic concepts — mono no aware , wabi-sabi , and yūgen — that are basic to the Japanese arts and “ways” ( dō ). Secondly, it traces some of the Buddhist (and Shintō) influences on the development of the Japanese aesthetic sensibility.

• Kukai in China: What he Studied and Brought back to Japan [Education About Asia, Association for Asian Studies] Article with images on the popular Japanese Buddhist priest, Kūkai (774-835 CE), whose significance as a historical figure continues to exists in every day life - and even a Maga series. He introduced Shingon esoteric Buddhism into his country in the Heian period, influenced the development of calligraphy and literature, planned the Mount Kōya Temple complex (an UNESCO World Heritage Site), and constructed the irrigation systems still in use today in his native island of Shikoku. Thousands continue to undertake "the Shikoku Pilgrimage" and invoke his legacy in aphorisms such as “Even Kūkai's brush makes mistakes." Download PDF on page.

Kukai, 774-835, founder of the Shingon or "True Word" school Primary Source w/DBQs • "Indications of the Goals of the Three Teachings" (Sango Shiki) and "A School of Arts and Sciences" [PDF] [Asia for Educators] Saicho, 767-822, founder of the Tendai (Tiantai) school Primary Source w/DBQs • Selected Writings: "Prayer on Mount Hiei"; "On the Possibility of Enlightenment for All Men"; "Vow of the Uninterrupted Study of the Lotus Sutra "; The Mahayana Precepts in Admonitions of the Fanwang Sutra " [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Also see the Video Unit on Classical Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Nara and Heian Periods) for more about Buddhism in Japan during this period .

Japanese Missions to Tang China: Remaking the Government

• The Japanese Missions to Tang China, 7th-9th Centuries [About Japan: A Teacher's Resource] "On nineteen occasions from 630 to 894, the Japanese court appointed official envoys to Tang China known as kentōshi to serve as political and cultural representatives to China. Fourteen of these missions completed the arduous journey to and from the Chinese capital. The missions brought back elements of Tang civilization that profoundly affected Japan's government, economics, culture, and religion." An in-depth article on the topic.

Prince Shōtoku, 573-621; Constitution, 604 CE Primary Source w/DBQs • The Constitution of Prince Shōtoku [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Emperor Kōtoku, 596-654; Reform Edict, 646 CE Primary Source w/DBQs • The Reform Edict of Taika [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Emperor Kammu, 737-806; Kondei System, 792 CE Primary Source w/DBQs • The Kondei System: An Official Order of the Council of State [PDF] [Asia for Educators]

Also see the Video Unit on Classical Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Nara and Heian Periods) for more about the influence of Confucianism on Prince Shōtoku's Constitution .

Waka (Tanka) Poetry: Manyōshū and Kokinshū

Manyôshū, compiled 7th century; Kokinshū, compiled 8th to 10th centuries Primary Source • The Manyōshū and Kokinshū Poetry Collections [Asia for Educators] Excerpts from Japan's oldest collections of poems. The Kokinshū was the first collection of poems of the waka form. Followed by discussion questions.

Primary Source • What Is a waka ? [Asia for Educators] An essay about the history and structure of waka (also called tanka ), a type of short poem from which the haiku was derived. Followed by discussion questions and classroom exercises.

Also see the Video Unit on Classical Japan in the History-Archaeology section (Nara and Heian Periods) for more about waka poetry and the Manyōshū and Kokinshū poetry collections .

Court Literature of the Heian Period: The Pillow Book (ca. 1002), The Tale of Genji (ca. 1021)

Multimedia • The Culture of Genji [Five College Center for East Asian Studies] Webinar on Youtube with accompanying handout [PDF] .

Multimedia • Tale of Genji [Annenberg/Invitation to World Literature] Part of the Annenberg Invitation to World Literature series, this excellent introduction to the "Tale of Genji," with short, introductory video, excerpts, maps, slide images of landscape, key points, characters, themes, and more. Specialists providing short insights on video include Patrick Caddeau, Lisa Dalby, and David Damrosch.

• Literature of the Heian Period (794-1185) [Asia for Educators] Two introductory readings on the aristocratic-court culture of the Heian Period, which produced such literary masterpieces as The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book . One reading is for students; the second reading is provides additional background information for teachers. Both readings are intended to serve as introductions to a lesson about The Tale of Genji , The Pillow Book , or waka .

Primary Source + Lesson Plan + DBQ • Writers of the Heian Era [Women in World History, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University] An excellent teaching module for Heian-period literature, with four excerpts from The Pillow Book and two excerpts from The Tale of Genji , plus three images from a 12th-century scroll depicting The Tale of Genji . There is also a lesson plan for high school students, "An Intimate Glimpse: Lives of Court Women in Japan," and a document-based question (DBQ).

Primary Source • Excerpts from The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon [Asia for Educators] With exercises for students.

• Murasaki Shikibu [Women in World History] A brief biography of the author of The Tale of Genji .

Primary Source • Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan [Digital Library, University of Pennsylvania] Full text of a 1920 book that includes the diary of Murasaki Shikibu, author of The Tale of Genji .

• The Tale of Genji [Asia for Educators] A short introduction to The Tale of Genji , followed by an analysis of the famous "Yūgao" chapter. With exercises for students.

Primary Source (in Japanese) • Genji monogatari [Japanese Text Initiative, University of Virginia] In three versions that can be viewed separately or together — in the original script, in a modernized script, and in romaji.

• The Heart of History: The Tale of Genji [Education About Asia, Association for Asian Studies] The author suggests "several ways in which aspects of The Tale of Genji may deepen our understanding of Japan during the Heian period as well as even contemporary Japan." Download PDF on page.

Video Unit • The Tale of Genji [Asia for Educators] Literary salons, women as authors, and the impact of The Tale of Genji are discussed by the featured speakers: Columbia University professors Haruo Shirane and Paul Varley, and Asia Society President Emeritus Robert Oxnam. Section Topics:

• Japanese Aesthetics and the Tale of Genji [ExEAS, Columbia University] Using an excerpt from the chapter “The Sacred Tree,” this unit offers a guide to a close examination of Japanese aesthetics in The Tale of Genji (ca.1010). This two-session lesson plan can be used in World Literature courses or any course that teaches components of Zen Buddhism or Japanese aesthetics (e.g. Introduction to Buddhism, the History of Buddhism, Philosophy, Japanese History, Asian Literature, or World Religion).