Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Lesson Plans

These lesson plans help you integrate learning about works of art in your classroom. Select an option below to browse lesson plans by grade, or continue scrolling to see all lesson plans.

Lesson plans for elementary school students

Lesson plans for middle school students

Lesson plans for high school students

Elementary School

Ancient Animals at Work

Identify ways animals (past and present) enhance daily life through a close look at an ancient figurine and art making.

Animal-Inspired Masks and Masquerades

Help students understand the connections between art and the environment of Guinea, animal anatomy, and the cultural context of the Banda mask with the help of viewing questions and a dance activity in the Museum's African Art galleries.

Armor—Function and Design

Identify moveable and static features of armor as well as functional and symbolic surface details and examine similarities and differences between human and animal "armor" through classroom viewing questions. Enhance the lesson with a sketching activity based on an English suit of armor in The Met collection.

The Astor Chinese Garden Court

Explore the Museum's Astor Chinese Garden Court and enhance students' understanding of how traditional Chinese gardens reflect the concept of yin and yang and how material selection and design can convey ideas about the human and natural worlds. Use viewing questions and a storytelling or drawing activity in the Museum's Chinese galleries.

The Burghers of Calais

Convey the interpretive significance of pose and expression in the visual arts—in the Museum or the classroom—with viewing questions and a story-writing activity inspired by a nineteenth-century French sculpture by Auguste Rodin.

Medieval Beasts and Bestiaries

Explore the use of animals as symbols in medieval art with viewing questions and a group drawing activity at The Met Cloisters or in the classroom.

Power in Ancient Mesopotamia

Examine how a great ancient Mesopotamian king conveyed power and leadership in a monumental wall relief in the Museum's Ancient Near Eastern art collection and consider how leaders today express the same attributes through viewing questions and an activity.

The Nomads of Central Asia—Turkmen Traditions

Students will be able to identify ways art of the Turkmen people of Central Asia reflects nomadic life and understand the functional and symbolic role objects play in their lives.

Voices of the Past

Focus on a slit gong in the Museum's Oceanic collection to illustrate the impact of scale in works of art, and consider objects' functions in their original contexts and ways different communities engage with their elders and ancestors. Classroom viewing questions and an oral history activity enhance the lesson.

Middle School

Aeneas, Art, and Storytelling

Virgil's epic poem, The Aeneid , has inspired generations of artists and writers. Create your own artwork inspired by the text and consider how artists draw upon and reinterpret stories from the past.

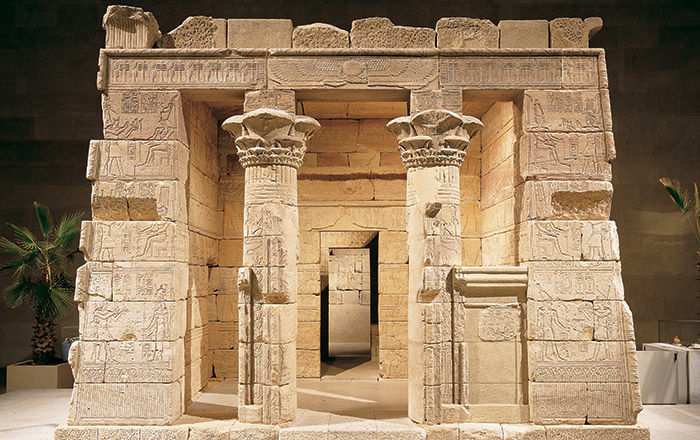

Architecture and the Natural World

How can buildings reflect the relationship between people and the environment? Explore possibilities in this lesson plan featuring an ancient Egyptian temple.

Art and Empire—The Ottoman Court

Students will be able to recognize ways a tughra functioned as a symbol of power and authority within a culturally diverse and geographically expansive empire.

The Battle of David and Goliath

Illuminate strategies for conveying stories through images in the classroom with viewing questions about a large silver plate in the Museum's Medieval collection and an illustrating activity.

Beyond the Figure

Consider how artists convey personality in nonfigural portraits and the relationship between visual and verbal expression by looking at a painting by Charles Demuth in the Museum's Modern and Contemporary galleries and through a portrait-making activity in the classroom.

Bravery Stands Tall

Examine a major turning point in the American Revolution through a close look at this depiction of General Washington and his troops crossing the Delaware River.

Composing a Landscape

Study the relationship between the human and natural worlds in art, as well as the techniques artists use to convey ideas, by exploring a painting by Frederic Edwin Church in the Museum's American Wing. Extend the lesson through a writing and drawing activity in the classroom, or a sketching activity outdoors.

The Making of a Persian Royal Manuscript

Students will be able to identify some of the key events and figures presented in the Persian national epic, the Shahnama (Book of Kings); make connections between the text and the illustrated pages of the manuscript produced for Shah Tahmasp; and create a historical record of their community.

The Mughal Court and the Art of Observation

Students will be able to recognize ways works of art reflect an intense interest in observation of the human and natural world among Mughal leaders; and understand ways works of art from the past and present communicate ideas about the natural world.

Muses vs. Sirens

Through movement and storytelling, uncover the layers of meaning embedded in a Roman sarcophagus.

Point of View in Print and Paint

Explore ways that viewpoint shapes the way we picture the past in this lesson plan featuring a depiction of the abolitionist John Brown.

The Power behind the Throne

Bring the Museum's African collection into the classroom with viewing questions and an art-making activity that cultivate visual analysis and an understanding of how surface detail and composition can express themes of power and leadership.

A Rite of Passage

Explore the ways rituals, ceremonies, and rites of passage play an important role in communities around the world through an investigation of related objects.

Science and the Art of the Islamic World

Students will be able to identify similarities and differences between scientific tools used now and long ago; and use research findings to support observations and interpretations.

Shiva—Creator, Protector, and Destroyer

Inspire students to interpret, communicate through, and personally connect with art through an in-classroom examination of a powerful sculpture in the Museum's Indian art collection and a self-portrait activity.

High School

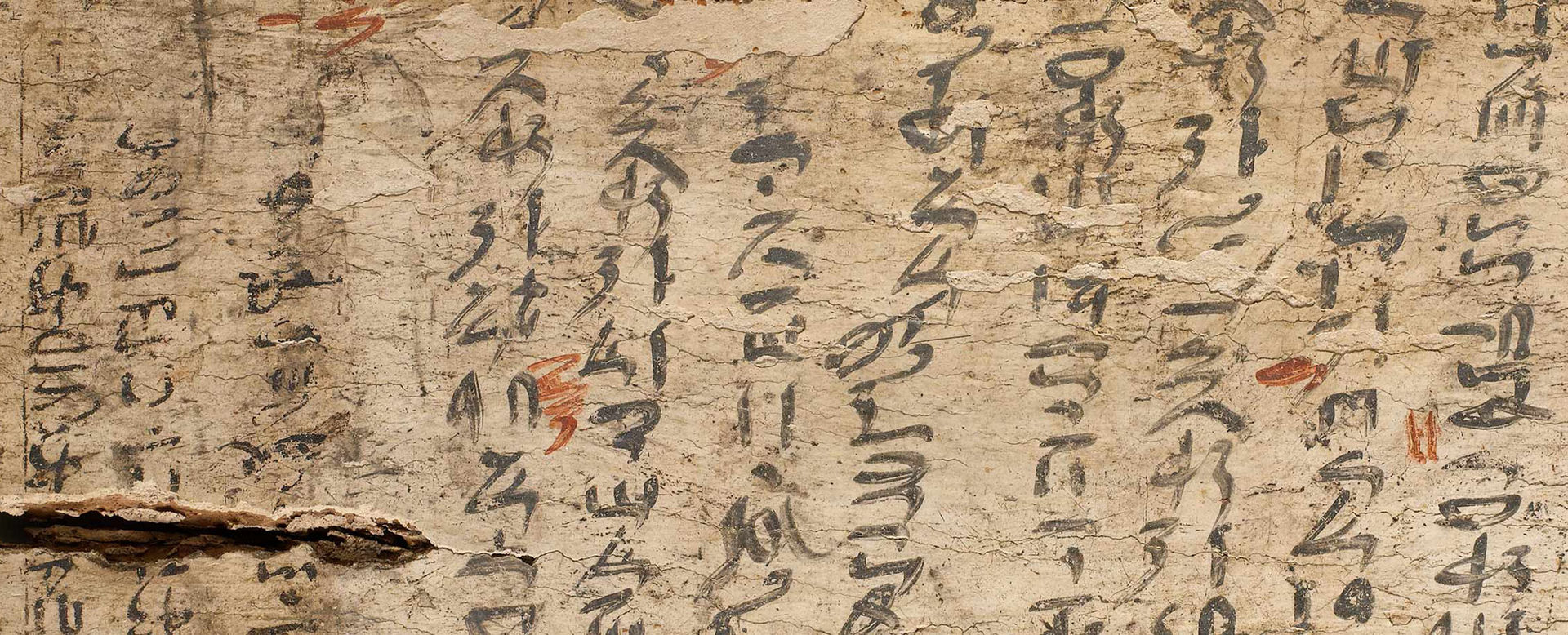

Ancient Mesopotamia—Literacy, Now and Then

From cuneiform inscriptions to digital tablets, this lesson highlights changes and continuity in written communications across the ages.

Arabic Script and the Art of Calligraphy

Students will be able to identify visual qualities of several calligraphic scripts; recognize ways artists from the Islamic world engage various scripts to enhance works of art supporting a range of functions; and assess the merits of several computer-generated fonts in supporting specific uses.

The Art of Industry

Use viewing questions and a debate activity to investigate the relationship between art and community values, techniques artists use to convey ideas, and strategies for interpreting an American painting in the Museum's Modern and Contemporary galleries.

Above: Writing board (detail), ca. 1981–1802 B.C. Middle Kingdom. Dynasty 12. From Egypt; Said to be from Upper Egypt, Thebes or Northern Upper Egypt, Akhmim (Khemmis, Panopolis). Wood, gesso, paint, 16 15/16 x 7 1/2 in. (43 x 19 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1928 (28.9.4)

*Grades 9-12

We’ve listed all of our High School (Secondary School) art lesson plans here. These activities are best suited for Grades 9-12 – or – ages 14 and up years.

Drawing with Glue

by Andrea Mulder-Slater If you are looking for a sure fire way to get a great response from your students, walk into the art room and tell them they will …

6 Ways to Make Sketchbooks

by Andrea Mulder-Slater When I was a student at art school, my drawing professor had one rule and that was to draw, every single day. From her I learned there …

Glue Flowers

K-2, Grades 3-5, Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12

Negative Space Plant Drawings

Grades 3-5, Grades 6-8, High School

Criss Cross Doodles

by Andrea Mulder-Slater Using materials found in every art room, students will draw criss cross lines to create shapes for doodles to live! Then, by following a few basic prompts, …

Architecture Mood Board

Grades 3-5, Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12

Draw and Paint a Sea Turtle

Go With the Flow Watercolor Trees

Printed Fall Trees

Pumpkin Swirls

PreK, K-2, Grades 3-5, Grades 6-8, Grades 9-12

Abstract Squares

Artist Trading Cards

Paper Butterflies

Cerealism (Cereal Box Collage) with Michael Albert

Roll a Harvest Basket

Teaching Art at Home

Creative Cursive

Name Color Wheels

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Art history

Special topics in art history, the seeing america project, prehistoric art, ancient mediterranean + europe, medieval europe + byzantine, art of the islamic world 640 to now, europe 1300 - 1800, art of the americas to world war i, europe 1800 - 1900, modernisms 1900-1980, global cultures 1980–now, art of asia, art of africa, art of oceania, for teachers, a brief introduction to art history, explore art from around the world.

A Fun New Way to Teach Art History!

Trying to sneak vegetables into my son’s diet is like trying to sneak art history into my visual arts curriculum. Sometimes it’s not as easy as it seems, and he gets bored of the same old vegetable, much like my students get bored when I teach art history the same way. Therefore, I frequently try to find new, unique, and hidden ways to incorporate more art history into my curriculum . The more art history the better.

A couple of years ago, I needed a lesson or activity to use on the last day of the quarter. If you’re like me, you prefer the last day of art class to be as stress and mess free as possible. I wanted the activity to include art history and to be fun for my students.

I browsed the internet and my art supply catalogs for ideas.

After finding an art BINGO game that was out of my budget, it occurred to me, I should make my own BINGO set! So that’s exactly what I did.

First, i created a blank bingo sheet using microsoft excel..

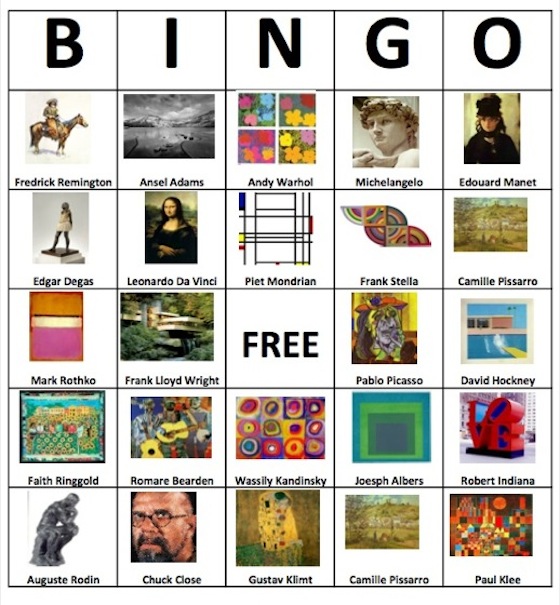

On a separate spreadsheet, I pasted images of famous works of art with the artists names below.

This second spreadsheet served as the bank of images used for the blank BINGO cards. (If you decided to try this, be sure to include extra images so the games last a little longer. I had a bank of 48 different images.)

I created a few examples and then I handed the project over to a couple of my students.

They copied and pasted the images randomly into the blank BINGO spreadsheet and created a classroom set of 30 Art History BINGO cards. Here is one example.

The best part about this project is that now since I have the blank template created, I can create a variety of art themed BINGO games!

If you’d like, you can download a free BINGO template right here !

What are your favorite activities or games to use to teach art history?

What kind of BINGO would you create for your classroom?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.

Cassidy Reinken

Cassidy Reinken, an art educator, is a former AOEU Writer. She enjoys helping students solve problems and reach their potential.

5 Art Activities to Unwind After Testing and Portfolio Submissions

3 Contemporary Artists Making Amazing Work from Materials Found in Every Art Room

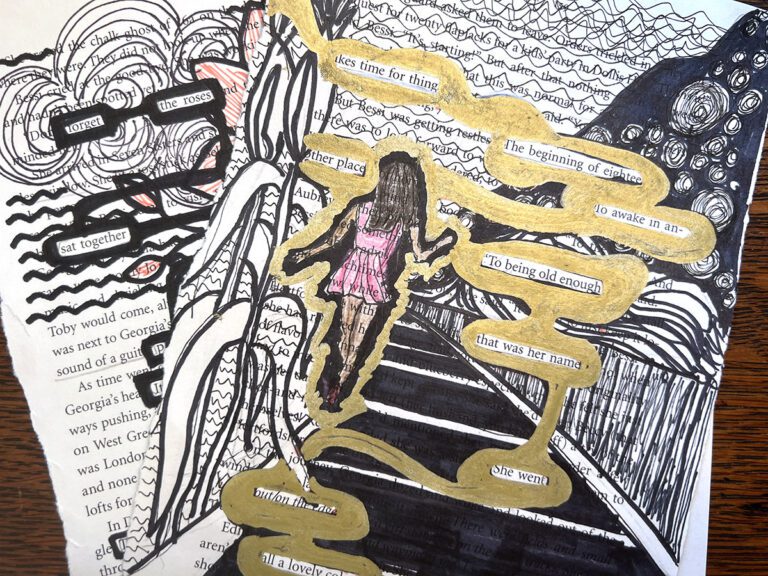

From Text to Powerful Art: How to Explore Blackout Poetry in Your Art Room

Bring Concrete Poetry Into the Art Room to Support All Learners

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy .

Sign Up for our FREE Newsletter!

Lesson plans.

- Lesson Templates

- Certificates

- Find Grants

- Fundraising

Search for Resources

You are here

Art history.

Art history, also called art historiography, historical study of the visual arts, being concerned with identifying, classifying, describing, evaluating, interpreting, and understanding the art products and historic development of the fields of painting, sculpture, architecture, the decorative arts, drawing, printmaking, photography, interior design, etc.

Studying the art of the past teaches us how people have seen themselves and their world, and how they want to show this to others. Art history provides a means by which we can understand our human past and its relationship to our present, because the act of making art is one of humanity's most ubiquitous activities.

Copyright © 2001 - 2024 TeacherPlanet.com ®. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement and Disclaimer Notice

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter and receive

top education news, lesson ideas, teaching tips, and more!

No thanks, I don't need to stay current on what works in education!

- Our Mission

How to Use Art to Teach History

A piece of art can provide a window into a historical time period for students.

Art is an important and perhaps unexpected tool in teaching history. Photos, drawings, and paintings can communicate an abundance of information about historical events. Students can analyze pieces of art to assist them in digging deeper into investigating an artist’s perspective and decision-making.

Provide students with the knowledge and time to learn how an artist’s techniques impact how we interpret historical events to help students become better historical thinkers and create deeper civil discourse. By making observations, asking questions, and sharing connections between art and history, students gain knowledge about history.

Select Works of Art

When choosing art for students to examine, first decide how the art will be incorporated in the lesson. For example, a piece of art can be an exciting way to introduce a new historical topic to students. When choosing which art to use, assess the degree of familiarity that students may have with the content of the work. Consider whether the art expresses a reaction to a historical decision and ways it might be used to frame a discussion about why people had those reactions and their responses.

Explore a range of media types. For example, a political cartoon can be a useful entry point for students who are less familiar with formal art. Three-dimensional work, such as a sculpture, offers variety. Avoid work that is too abstract, as it may be difficult for beginning students to comprehend. Consider works from artists of varying backgrounds.

Don’t limit the work to one piece. Multiple pieces may be beneficial in helping students investigate how a person or event was perceived in the historical period and today. Look for pieces that represent multiple perspectives so that students have the opportunity to grapple with the artists’ decisions. Selecting works that use several artistic techniques will allow for a more robust discussion of the connections that students can make between the work and history.

In making decisions about what art to use, consider supplemental materials that may help bring the work to life. Texts about interpretations of the work can be a helpful tool to scaffold learning. Lesson plans, supportive texts, and accompanying guided questions are readily available online through organizations such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art to support integration of art history into classrooms.

Model the Process

Model how to study art in detail to convey expectations for how students should approach the same practice.

For example, I walk students through an interpretation of the painting Washington Crossing the Delaware , by Emanuel Leutze. In this painting, George Washington is leading the Continental Army across the Delaware River to carry out an attack on Hessians. Leutze used various compositional techniques to define Washington as a leader while also allowing observers to interpret the painting for themselves.

Point out techniques in the work of art. Students will have their own opportunity to interpret the painting for themselves and reach their own conclusions, not only about the artist’s perspective but also about how it relates to the study of history.

Offer several elements for students to consider to analyze the visual composition of a painting:

- Color: Using different colors, especially those that contrast, can communicate how one may feel about a person, event, or idea.

- Framing: Ask students to examine how surrounding features create a frame around the main focus of the picture. In the Washington Crossing the Delaware example, Washington is surrounded by his soldiers, ice, and the flag, encouraging viewers to remain focused on his depiction.

- Symbolism: Encourage students to think about what something stands for more than what it just appears to be.

- Body language: Positioning and facial expression can communicate how a subject feels within the photo, drawing, or painting.

- Lighting and shadow: Amounts of light and dark can present information regarding something that occurred or will happen in the future.

Connect to History

After students understand the specific techniques used in a piece of art, explain how it may relate to historical events. Outline the learning goal for students at the outset. Be prepared to share pieces of information about the historical event as the students begin their task. Some students will be able to take the discussion in the direction you want, while others can benefit from guided questions to help focus their observations.

Begin with the basics by asking students to assess what the artwork tells them about the time period or individual. Then ask them to evaluate the artist’s choices in how they created the image. What techniques did they use to convey different points of view? What do the techniques used reveal about the historical period? Are there omissions in the artist’s work that reveal information about the time period?

For example, once students understand the technique of framing, they can consider what surrounds the main subject of the picture to create a frame instead of looking at these parts independently without any connection to one another. After students evaluate the artist’s choices, they can begin to interrogate the artist’s motive, the perspectives expressed, and the facts and omissions about the event itself. In Washington Crossing the Delaware , framing brings the flag to the viewer’s attention. Students can use that observation to respond to the prompts to gain insight on the historical significance of the work.

Once students have assessed the individual piece of art and the artist, ask them to consider the piece in the context of other works at the time. Providing other contrasting examples of art from the time period can help reinforce learning about the time period.

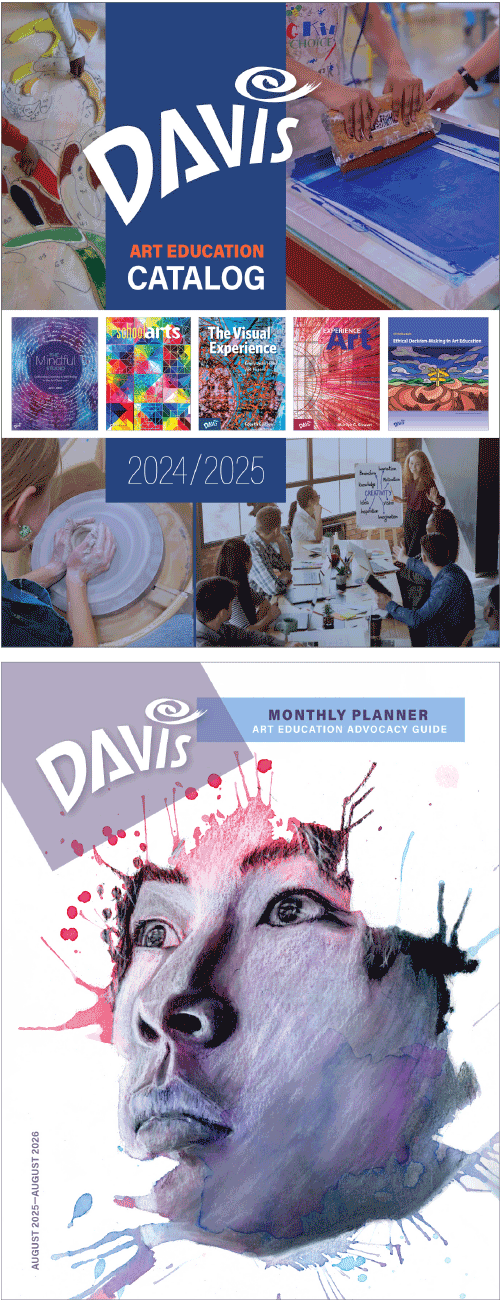

- Davis Art Images

- Free Resources

- Job Opportunities

- Write for Davis

- Sign up for the Digital Edition

- SchoolArts Collection

- Get Published in SchoolArts

- Writer’s Guidelines

- Request a Sample Issue

- K12ArtChat the Podcast

- Adaptive Art Resources

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Resources

- Professional Development

- SchoolArts Magazine Online

- Teaching Art Online

- FREE Lessons

- Elementary/Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Davis Select

- Davis Digital

Free Resource

Request Catalog or Planner

- Explorations in Art. Kindergarten

- Explorations in Art. Grades 1–6

- Creative Minds—Out of School

- Early Childhood Books

- Resource Books

- Experience Art

- Exploring Visual Design

- The Visual Experience

- The Davis Studio Series

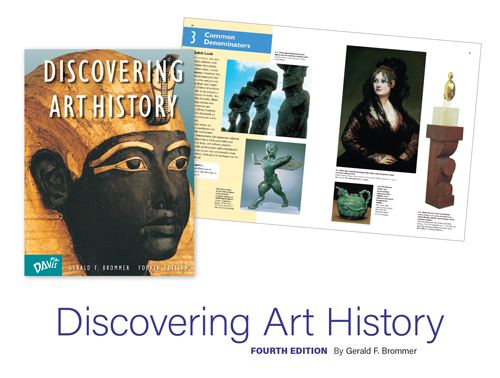

Discovering Art History

- Collaborative Tape Art and PiktoTape

- PiktoTape.com

- In-Person and Online Sessions

- Complimentary Sessions

- Art Education in Practice

- Davis Select Art Books

- Start a FREE Trail

High School Products

This outstanding art history textbook will show students how the visual arts serve to shape and reflect ideas, issues, and themes from the time of the first cave paintings to the twenty-first century.

Learn more about this engaging art history textbook and all it can provide for your classroom.

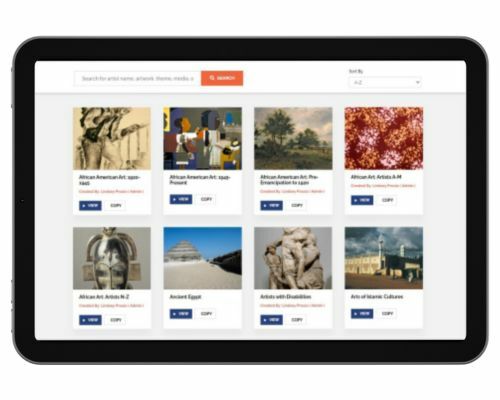

Easily access high-quality fine art images from leading museums and galleries.

Discovering Art History is an in-depth, comprehensive approach to art history. This art history textbook includes an extensive survey of Western art, studies of non-Western art, as well as an introduction to art appreciation. Engaging studio activities throughout the text are directly connected to chapter content.

Textbook Features

- Vibrant fine art examples.

- In-depth profiles of artists, artistic periods, and movements.

- Useful maps, timelines, and diagrams.

- Student profiles for peer comparison of studio exercises.

- Visual resources with point-of-use correlations.

- Two studio activities in each chapter.

- Multicultural and interdisciplinary connections.

- Hundreds of additional inquiry and research-related exercises.

- Contextual information to encourage discussion and understanding.

- Higher-order thinking skills that promote critical thinking.

Table of Contents

- Part One: The World and Work of the Artist

- Chapter 1: Learning about Art

- Chapter 2: The Visual Communication Process

- Part Two: Trends and Influences in the World of Art

- Chapter 3: Looking for a Common Denominator

- Chapter 4: Non-Western Art and Cultural Influences

- Part Three: Art in the Western World

- Chapter 5: Beginnings of Western Art

- Chapter 6: Greek and Roman Art

- Chapter 7: Religious Conviction

- Chapter 8: Romanesque and Gothic Art

- Chapter 9: The Italian Renaissance

- Chapter 10: Renaissance in the North

- Chapter 11: Baroque and Rococo

- Chapter 12: Three Opposing Views

- Chapter 13: Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

- Chapter 14: A Half-Century of “Isms”

- Chapter 15: American Art 1900–1950

- Chapter 16: Architecture after 1900

- Chapter 17: Art from the Fifties to the Present

Always Stay in the Loop

Want to know what’s new from Davis? Subscribe to our mailing list for periodic updates on new products, contests, free stuff, and great content.

We use cookies to improve our site and your experience. By continuing to browse our site, you accept our cookie policy. Find out more .

- Survey 1: Prehistory to Gothic

- Survey 2: Renaissance to Modern & Contemporary

- Thematic Lesson Plans

- AP Art History

- Books We Love

- CAA Conversations Podcasts

- SoTL Resources

- Teaching Writing About Art

- VISITING THE MUSEUM Learning Resource

- AHTR Weekly

- Digital Art History/Humanities

- Open Educational Resources (OERs)

Survey 1 See all→

- Prehistory and Prehistoric Art in Europe

- Art of the Ancient Near East

- Art of Ancient Egypt

- Jewish and Early Christian Art

- Byzantine Art and Architecture

- Islamic Art

- Buddhist Art and Architecture Before 1200

- Hindu Art and Architecture Before 1300

- Chinese Art Before 1300

- Japanese Art Before 1392

- Art of the Americas Before 1300

- Early Medieval Art

Survey 2 See all→

- Rapa Nui: Thematic and Narrative Shifts in Curriculum

- Proto-Renaissance in Italy (1200–1400)

- Northern Renaissance Art (1400–1600)

- Sixteenth-Century Northern Europe and Iberia

- Italian Renaissance Art (1400–1600)

- Southern Baroque: Italy and Spain

- Buddhist Art and Architecture in Southeast Asia After 1200

- Chinese Art After 1279

- Japanese Art After 1392

- Art of the Americas After 1300

- Art of the South Pacific: Polynesia

- African Art

- West African Art: Liberia and Sierra Leone

- European and American Architecture (1750–1900)

- Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth-Century Art in Europe and North America

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Sculpture

- Realism to Post-Impressionism

- Nineteenth-Century Photography

- Architecture Since 1900

- Twentieth-Century Photography

- Modern Art (1900–50)

- Mexican Muralism

- Art Since 1950 (Part I)

- Art Since 1950 (Part II)

Thematic Lesson Plans See all→

- Art and Cultural Heritage Looting and Destruction

- Art and Labor in the Nineteenth Century

- Art and Political Commitment

- Art History as Civic Engagement

- Comics: Newspaper Comics in the United States

- Comics: Underground and Alternative Comics in the United States

- Disability in Art History

- Educating Artists

- Feminism & Art

- Gender in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Globalism and Transnationalism

- Playing “Indian”: Manifest Destiny, Whiteness, and the Depiction of Native Americans

- Queer Art: 1960s to the Present

- Race and Identity

- Race-ing Art History: Contemporary Reflections on the Art Historical Canon

- Sacred Spaces

- Sexuality in Art

Creative Assessments for Creative Art History Teaching

Leah McCurdy

August 23, 2019

AHTR Weekly Categories

- Announcement

- Digital Humanities

- Equity in Education

- Lesson Plan

- Online Teaching

- Student Voices

- Teaching Strategies

- Uncategorized

- Writing About Art

Recent Posts

- Re-Teaching Rapa Nui

- Revealing Museums — Together

- Baptism by Fire: Tips and Tactics from My First Time Teaching Remotely

- Can COVID-19 Reinvigorate our Teaching? Employing Digital Tools for Spatial Learning

Pedagogical evolution and innovation in art history increase student engagement and ‘buy-in.’ Innovations also keep instruction from feeling stale for both the students and instructors. Innovation also can remind us why we keep walking into the classroom. An AHTR Weekly post by Cara Smulevitz from April 2018 about her move from the traditional “high-stakes exams + research paper model” to a structure focused on “multi-option creative assessments” helped to bring me out of an existential teaching spiral of doom last spring.

A couple years earlier, I had found myself googling something like ‘how do I teach nonwestern art history.’ As a recent PhD in anthropological archaeology, I felt unprepared returning to the arena of my undergraduate art history degree. Through that search, I found AHTR. The lesson plans were invaluable as a starting point and gave me confidence to design an introductory nonwestern survey that wouldn’t just sound like an anthropological tour of cultures. In exploring AHTR further, I found a platform focused on the types of pedagogical innovation that I had been striving for since I started teaching anthropology and archaeology as a grad student.

Addressing students’ needs

Like many in the AHTR community, I’ve tried to shake things up. Most of my students are studio or graphic design majors, required to take art history courses by their degree plans. (They often phrase it as being “forced” to learn art history.) I’ve been increasingly dissatisfied with what value traditional slide identification assessments offer for student learning. In my experience, they serve the grade much more than they serve insight, practice, or engagement. Adhering to a learner-centered approach, I regularly assign a participatory activity I call #hints for which students create hypothetical social media hashtags about artworks that they submit on index cards with brief explanations. They continually surprise me with their wit and creativity. I highlight some the best #hints when reviewing previous material and as actual hints on assessments. This gives the students a sense of ownership over the course and we always get a good laugh. I’ve also found that students make connections to contemporary media that I would not have considered. For example, I learned about the interesting appropriation of ancient Jomon flame rim vessels of Japan in the video game Zelda: Breath of the Wild . These #hints are one of the inspirations for my newly developed course entitled “Ancient Art in Contemporary Visual Culture.”

In terms of assessment, several semesters ago I implemented what I call VIZ IDs , or visual identifications, as an option on traditional slide ID tests. Students sketch an artwork and label facets of its significance according to a series of ‘landmarks’ highlighted in lecture. Visually minded students often struggle with the text-based memorization requirements of the slide ID but excel at recalling and visualizing important aesthetic or compositional qualities that relate to meaning. For studio and graphic design majors, the VIZ ID option helps them to visually engage with historic artworks in ways that can impact their own art making and increase the relevance they attribute to art history.

As an alternative to writing a final paper, I’ve offered art majors the option of producing an artwork and an academically written artist statement inspired by their experience in the class. It took me several semesters to situate the guidelines and rubrics for these projects comfortably. But since the beginning, I have been blown away by how students can represent their learning to such a better degree when given the opportunity to follow their preferred mode of expression. Students are still required to meet academic writing standards, such as citing sources and presenting a point of view, but this alternative allows them to focus on the type of writing that will be most relevant to them in the future. I started an online project exhibition called UTA Art History Matters to show off many of these projects with excerpts from artist statements. Glass arts, digital illustrations, research papers, and educational activities mingle in that exhibition to demonstrate the positive impact art history education can have for all students who make their way into our classrooms.

License to experiment

Fast forward to last spring and the existential spiral. I had just finished grading the first test for an intermediate course on ancient Egypt and the Near East. That class was engaged and participatory, but, inevitably, memorization-based assessments bring out the worst in many students (anxiety, apathy, anger, etc.). I sought help from AHTR and found Cara’s post. She described the creative options she offered to her students and the types of submissions she received. Following Cara’s lead, I offered my students four application project options that they could submit as a replacement of the last exam of the semester. In addition to the remix (or mashup), brief research essay, and documentary video options presented by Cara, I also offered an exhibition design option. All options required an academic document discussing their project with references to class discussions and external sources.

About half the class chose to submit a project replacement. Those who chose to stick with the exam said that it was easier, and they were more familiar with the expectations. The challenge to be creative and apply one’s understanding can be daunting. For many students, it seems more straightforward to memorize titles, artists, period, etc. But learning outcomes can be superficial and fleeting. Memorized detail often doesn’t stick long term.

Almost all who submitted project replacements chose the remix/mashup option. Many of them submitted creative, well-considered, and contextualized applications of class discussions, demonstrating that their experience in the course reached beyond surface learning. Some students struggled with articulating their ideas and others with following directions. These are larger issues that I don’t think undermine the success of the assessment strategy. The students that chose the application challenge found an opportunity to combine their art-making skills with class content that increased the likelihood they could be successful and earn a grade they would be happy with.

Results and reflections

Since first using Cara’s strategy in the spring, I’ve also implemented it in a 5-week upper level summer course. I assigned students a series of application projects of increasing difficulty and a final project ‘exhibition,’ where students present an improved and expanded version of a previously submitted project and present it to the class. In addition to the options described above, students could also choose to write public blog posts, create physical art objects and artist statements, or develop an art education activity for a target grade level. For each option, students submitted an academic paper with references to demonstrate their understanding of course themes and relevant artworks. Most studio or graphic design majors chose to make art objects or write blog posts. Most art history majors chose to write research papers or create exhibition designs. These projects allowed them to practice, demonstrate, and hone skills that are directly relevant to their interests, while upholding academic art history standards of writing and attribution.

In terms of course grades, the projects are weighted to encourage improvement, based on formative feedback, and to not overly penalize students with less experience in art making or writing. To ensure that grades reflect learning outcomes relevant to art history, I try to develop rubrics that do not focus on artistic merit but on the demonstration of understanding of course content and improvement. Thus, feedback is crucial and consumes most of my grading time.

Students in this recent course have once again blown me away. They have pursued themes of cultural appropriation, authenticity in art, and art world ethics through their own lens. Their perspective and creative interpretations have also allowed me to continue to learn more about these topics, and I plan to use artworks created by students of this semester as examples for discussion the next time I teach this course.. That is one of the most satisfying and valuable results of my move to creative assessment. This cycle makes the course itself a creative endeavor.

Previous Post

4 responses to “Creative Assessments for Creative Art History Teaching”

Wonderful ideas here! Thanks so much. I’d love to know more about the #hints activity. Could you give a few examples of what the students came up with? And is this all done just by writing on the index cards, or done online? Thanks again!

Thanks, Elise. #hints is one of my students’ favorites. They love seeing their #hint on the review and quiz slides. I experimented with having them submit on a social media site or online but it just encouraged students to be on their devices in class (which I find exceedingly annoying, though I know others are less irritated by it). I use the index cards as a way to take attendance and to assess participation each class session (thus, why I don’t use an LMS discussion board type submission). So when it is a #hints day, I ask them to provide the #hint, the artwork details that it relates to (as a way to practice remembering that info), and a brief explanation of why the hashtag works for that artwork. I started asking for the explanation because they pull from song lyrics, movies, and games that I’m not familiar with. I choose those that hit the mark the best to share with the rest of the class. I’ve found this works for me but I know there are many other ways to incorporate the #hints idea.

There are so many great examples. The ones that I have on my mind right now relate to early African arts from my large nonwestern survey.

Running Woman Rock Art Painting from Tassili N’ajjer, Algeria: #WWForestD?(as a hint to the title of “running”); #footloose (because it probably depicts dancing more than running); #simbasuncle (because it depicts SCARification).

Benin Kingdom Bronze Plaque depicting Warrior Chief and Attendants: #squad (based on the visual qualities of the chief and attendants, linking to the title of the work); #largerthanlife (because it is one of our first examples to highlight hierarchy of scale); #cameandtookit (because I highlight the British Punitive Expedition that resulted in these plaques and other Benin artifacts being in the British Museum collection).

Other examples from my Egyptian and Near East class:

Neo-Assyrian Stele of Ashurnasirpal II: #slampoetry (because he is depicted doing the Assyrian snapping gesture of worship)

Throne of King Tutankhamun: #laz-e-boy (referring to the armchair style and King Tut’s posture and the relevance of his medical condition to the history of the 18th Dynasty).

I hope those examples offer a picture of the variability and fun that can comes from #hints. As I mention in the post, several students submitted #breathofthewild for a hint about the early Japanese Jomon vessels. When I brought it up the next class, almost everyone knew the reference.

Great idea, Leah, and I love what your students came up with!

So glad my post was helpful Leah! I love your ideas here– particularly the VizID option, which is such a great way to make the memorization element of art history assessments more meaningful. I’m definitely going to think about ways I can integrate that into some of my courses. Thanks for sharing these valuable ideas and reflections!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

Whales Have an Alphabet

Until the 1960s, it was uncertain whether whales made any sounds at all..

This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email [email protected] with any questions.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

From “The New York Times,” I’m Michael Barbaro. This is “The Daily.”

Today, ever since the discovery that whales produce songs, scientists have been trying to find a way to decipher their lyrics. After 60 years, they may have finally done it. My colleague, Carl Zimmer, explains.

It’s Friday, May 24.

I have to say, after many years of working with you on everything from the pandemic to —

— CRISPR DNA technology, that it turns out your interests are even more varied than I had thought, and they include whales.

They do indeed.

And why? What is it about the whale that captures your imagination?

I don’t think I’ve ever met anybody who is not fascinated by whales. I mean, these are mammals like us, and they’re swimming around in the water. They have brains that are much bigger than ours. They can live maybe 200 years. These are incredible animals, and animals that we still don’t really understand.

Right. Well, it is this majestic creature that brings us together today, Carl, because you have been reporting on a big breakthrough in our understanding of how it is that whales communicate. But I think in order for that breakthrough to make sense, I think we’re going to have to start with what we have known up until now about how whales interact. So tell us about that.

Well, people knew that whales and dolphins traveled together in groups, but up until the 1960s, we didn’t really know that whales actually made any sounds at all. It was actually sort of an accident that we came across it. The American military was developing sophisticated microphones to put underwater. They wanted to listen for Russian submarines.

As one does. But there was an engineer in Bermuda, and he started hearing some weird stuff.

[WHALE SOUNDS]

And he wondered maybe if he was actually listening to whales.

What made him wonder if it was whales, of all things?

Well, this sound did not sound like something geological.

It didn’t sound like some underwater landslide or something like that. This sounded like a living animal making some kind of call. It has these incredible deep tones that rise up into these strange, almost falsetto type notes.

It was incredibly loud. And so it would have to be some really big animal. And so with humpback whales swimming around Bermuda, this engineer thought, well, maybe these are humpback whales.

And so he gets in touch with a husband and wife team of whale biologists, Roger and Katy Payne, and plays these recordings to them. And they’re pretty convinced that they’re hearing whales, too. And then they go on to go out and confirm that by putting microphones in the water, chasing after groups of whales and confirming, yes, indeed, that these sounds are coming from these humpback whales.

So once these scientists confirm in their minds that these are the sounds of a whale, what happens with this discovery?

Well, Roger and Katy Payne and their colleagues are astonished that this species of whale is swimming around singing all the time for hours on end. And it’s so inspirational to them that they actually help to produce a record that they release “The Song of the Humpback Whale” in 1970.

And so this is being sold in record stores, you know, along with Jimi Hendrix and Rolling Stones. And it is a huge hit.

Yeah, it sells like two million copies.

Well, at the time, it was a huge cultural event. This record, this became almost like an anthem of the environmental movement. And it led, for whales in particular, to a lot of protections for them because now people could appreciate that whales were a lot more marvelous and mysterious than they maybe had appreciated before.

And so you have legislation, like the Marine Mammal Act. The United States just agrees just to stop killing whales. It stops its whaling industry. And so you could argue that the discovery of these whale songs in Bermuda led to at least some species of whales escaping extinction.

Well, beyond the cultural impact of this discovery, which is quite meaningful, I wonder whether scientists and marine biologists are figuring out what these whale songs are actually communicating.

So the Paynes create a whole branch of science, the study of whale songs. It turns out that pretty much every species of whale that we know of sings in some way or another. And it turns out that within a species, different groups of whales in different parts of the world may sing with a different dialect. But the big question of what these whales are singing, what do these songs mean, that remains elusive into the 21st century. And things don’t really change until scientists decide to take a new look at the problem in a new way.

And what is that new way?

So in 2020, a group of whale biologists, including Roger Payne, come together with computer scientists from MIT. Instead of humpback whales, which were the whales where whale songs are first discovered, these scientists decide to study sperm whales in the Caribbean. And humpback whales and sperm whales have very, very different songs. So if you’re used to humpback whales with their crazy high and low singing voices —

Right, those best-selling sounds.

— those are rockin’ tunes of the humpback whales, that’s not what sperm whales do. Sperm whales have a totally different way of communicating with each other. And I actually have some recordings that were provided by the scientists who have been doing this research. And so we can take a listen to some of them.

Wow, It’s like a rhythmic clicking.

These are a group of sperm whales swimming together, communicating.

So whale biologists knew already that there was some structure to this sound. Those clicks that you hear, they come in little pulses. And each of those pulses is known as a coda. And whale biologists had given names to these different codas. So, for example, they call one coda, one plus one plus three —

— which is basically click, click, click, click, click, or four plus three, where you have four clicks in a row and a pause and then three clicks in a row.

Right. And the question would seem to be, is this decipherable communication, or is this just whale gibberish?

Well, this is where the computer scientists were able to come in and to help out. The whale biologists who were listening to the codas from the sperm whales in the Caribbean, they had identified about 21 types. And then that would seem to be about it.

But then, an MIT computer science graduate student named Prajusha Sharma was given the job of listening to them again.

And what does she hear?

In a way, it’s not so much what she heard, but what she saw.

Because when scientists record whale songs, you can look at it kind of like if you’re looking at an audio of a recording of your podcast, you will see the little squiggles of your voice.

And so whale biologists would just look at that ticker of whale songs going across the screen and try to compare them. And Sharma said, I don’t like this. I just — this is not how I look at data. And so what she decided to do is she decided to kind of just visualize the data differently. And essentially, she just kind of flipped these images on their side and saw something totally new.

And what she saw was that sperm whales were singing a whole bunch of things that nobody had actually been hearing.

One thing that she discovered was that you could have a whale that was producing a coda over and over and over again, but it was actually playing with it. It was actually stretching out the coda,

[CLICKING] So to get a little bit longer and a little bit longer, a little bit longer.

And then get shorter and shorter and shorter again. They could play with their codas in a way that nobody knew before. And she also started to see that a whale might throw in an extra click at the end of a coda. So it would be repeating a coda over and over again and then boom, add an extra one right at the end. What they would call an ornamentation. So now, you have yet another signal that these whales are using.

And if we just look at what the sperm whales are capable of producing in terms of different codas, we go from just 21 types that they had found in the Caribbean before to 156. So what the scientists are saying is that what we might be looking at is what they call a sperm whale phonetic alphabet.

Yeah, that’s a pretty big deal because the only species that we know of for sure that has a phonetic alphabet —

— is us, exactly. So the reason that we can use language is because we can make a huge range of sounds by just doing little things with our mouths. A little change in our lips can change a bah to a dah. And so we are able to produce a set of phonetic sounds. And we put those sounds together to make words.

So now, we have sperm whales, which have at least 150 of these different versions of sounds that they make just by making little adjustments to the existing way that they make sounds. And so you can make a chart of their phonetic alphabet, just like you make a chart of the human phonetic alphabet.

So then, that raises the question, do they combine their phonetic alphabet into words? Do they combine their words into sentences? In other words, do sperm whales have a language of their own?

Right. Are they talking to each other, really talking to each other?

If we could really show that whales had language on par with humans, that would be like finding intelligent life on another planet.

We’ll be right back.

So, Carl, how should we think about this phonetic alphabet and whether sperm whales are actually using it to talk to each other?

The scientists on this project are really careful to say that these results do not definitively prove what these sperm whale sounds are. There are a handful of possibilities here in terms of what this study could mean. And one of them is that the whales really are using full-blown language.

What they might be talking about, we don’t know. I mean, perhaps they like to talk about their travels over hundreds and thousands of miles. Maybe they’re talking about, you know, the giant squid that they caught last night. Maybe they’re gossiping about each other.

And you have to remember, sperm whales are incredibly social animals. They have relationships that last for decades. And they live in groups that are in clans of thousands of whales. I mean, imagine the opportunities for gossip.

These are all at least imaginable now. But it’s also possible that they are communicating with each other, but in a way that isn’t language as we know it. You know, maybe these sounds that they’re producing don’t add up to sentences. There’s no verb there. There’s no noun. There’s no structure to it in terms of how we think of language.

But maybe they’re still conveying information to each other. Maybe they’re somehow giving out who they are and what group they belong to. But it’s not in the form of language that we think of.

Right. Maybe it’s more kind of caveman like as in whale to whale, look, there, food.

It’s possible. But, you know, other species have evolved in other directions. And so you have to put yourself in the place of a sperm whale. You know, so think about this. They are communicating in the water. And actually, like sending sounds through water is a completely different experience than through the air like we do.

So a sperm whale might be communicating to the whale right next to it a few yards away, but it might be communicating with whales miles away, hundreds of miles away. They’re in the dark a lot of the time, so they don’t even see the whales right next to them. So it’s just this constant sound that they’re making because they’re in this dark water.

So we might want to imagine that such a species would talk the way we do, but there are just so many reasons to expect that whatever they’re communicating might be just profoundly different, so different that it’s actually hard for us to imagine. And so we need to really, you know, let ourselves be open to lots of possibilities.

And one possibility that some scientists have raised is that maybe language is just the wrong model to think about. Maybe we need to think about music. You know, maybe this strange typewriter, clickety clack is actually not like a Morse code message, but is actually a real song. It’s a kind of music that doesn’t necessarily convey information the way conversation does, but it brings the whales together.

In humans, like, when we humans sing together in choruses, it can be a very emotional experience. It’s a socially bonding experience, but it’s not really like the specific words that we’re singing that bring us together when we’re singing. It’s sharing the music together.

But at a certain point, we stop singing in the chorus, and we start asking each other questions like, hey, what are you doing for dinner? How are you going to get home? There’s a lot of traffic on the BQE. So we are really drawn to the possibility that whales are communicating in that same kind of a mode.

We’re exchanging information. We’re seeking out each other’s well-being and emotional state. And we’re building something together.

And I think that happens because, I mean, language is so fundamental to us as human beings. I mean, it’s like every moment of our waking life depends on language. We are talking to ourselves if we’re not talking to other people.

In our sleep, we dream, and there are words in our dreams. And we’re just stewing in language. And so it’s really, really hard for us to understand how other species might have a really complex communication system with hundreds of different little units of sound that they can use and they can deploy. And to think anything other than, well, they must be talking about traffic on the BQE. Like —

— we’re very human-centric. And we have to resist that.

So what we end up having here is a genuine breakthrough in our understanding of how whales interact. And that seems worth celebrating in and of itself. But it really kind of doubles as a lesson in humility for us humans when it comes to appreciating the idea that there are lots of non-human ways in which language can exist.

That’s right. Humility is always a good idea when we’re thinking about other animals.

So what now happens in this realm of research? And how is it that these scientists, these marine biologists and these computer scientists are going to try to figure out what exactly this alphabet amounts to and how it’s being used?

So what’s going to happen now is a real sea change in gathering data from whales.

So to speak.

So these scientists are now deploying a new generation of undersea microphones. They’re using drones to follow these whales. And what they want to do is they want to be recording sounds from the ocean where these whales live 24 hours a day, seven days a week. And so the hope is that instead of getting, say, a few 100 codas each year on recording, these scientists want to get several hundred million every year, maybe billions of codas every year.

And once you get that much data from whales, then you can start to do some really amazing stuff with artificial intelligence. So these scientists hope that they can use the same kind of artificial intelligence that is behind things like ChatGPT or these artificial intelligence systems that are able to take recordings of people talking and transcribing them into text. They want to use that on the whale communication.

They want to just grind through vast amounts of data, and maybe they will discover more phonetic letters in this alphabet. Who knows? Maybe they will actually find bigger structures, structures that could correspond to language.

If you go really far down this route of possibilities, the hope is that you would understand what sperm whales are saying to each other so well that you could actually create artificial sperm whale communication, and you could play it underwater. You could talk to the sperm whales. And they would talk back. They would react somehow in a way that you had predicted. If that happens, then maybe, indeed, sperm whales have something like language as we understand it.

And the only way we’re going to figure that out is if we figure out not just how they talk to themselves, but how we can perhaps talk to them, which, given everything we’ve been talking about here, Carl, is a little bit ironic because it’s pretty human-centric.

That’s right. This experiment could fail. It’s possible that sperm whales don’t do anything like language as we know it. Maybe they’re doing something that we can’t even imagine yet. But if sperm whales really are using codas in something like language, we are going to have to enter the conversation to really understand it.

Well, Carl, thank you very much. We appreciate it.

Thank you. Sorry. Can I say that again? My voice got really high all of a sudden.

A little bit like a whale’s. Ooh.

Yeah, exactly. Woot. Woot.

Thank yoooo. No. Thank you.

Here’s what else you need to know today.

We allege that Live Nation has illegally monopolized markets across the live concert industry in the United States for far too long. It is time to break it up.

On Thursday, the Justice Department sued the concert giant Live Nation Entertainment, which owns Ticketmaster, for violating federal antitrust laws and sought to break up the $23 billion conglomerate. During a news conference, Attorney General Merrick Garland said that Live Nation’s monopolistic tactics had hurt the entire industry of live events.

The result is that fans pay more in fees, artists have fewer opportunities to play concerts, smaller promoters get squeezed out, and venues have fewer real choices.

In a statement, Live Nation called the lawsuit baseless and vowed to fight it in court.

A reminder — tomorrow, we’ll be sharing the latest episode of our colleagues’ new show, “The Interview.” This week on “The Interview,” Lulu Garcia-Navarro talks with Ted Sarandos, the CEO of Netflix, about his plans to make the world’s largest streaming service even bigger.

I don’t agree with the premise that quantity and quality are somehow in conflict with each other. I think our content and our movie programming has been great, but it’s just not all for you.

Today’s episode was produced by Alex Stern, Stella Tan, Sydney Harper, and Nina Feldman. It was edited by MJ Davis, contains original music by Pat McCusker, Dan Powell, Elisheba Ittoop, Marion Lozano, and Sophia Lanman, and was engineered by Alyssa Moxley. Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly.

Special thanks to Project SETI for sharing their whale recordings.

That’s it for “The Daily.” I’m Michael Barbaro. See you on Tuesday after the holiday.

- May 31, 2024 • 31:29 Guilty

- May 30, 2024 • 25:21 The Government Takes On Ticketmaster

- May 29, 2024 • 29:46 The Closing Arguments in the Trump Trial

- May 28, 2024 • 25:56 The Alitos and Their Flags

- May 24, 2024 • 25:18 Whales Have an Alphabet

- May 23, 2024 • 34:24 I.C.C. Prosecutor Requests Warrants for Israeli and Hamas Leaders

- May 22, 2024 • 23:20 Biden’s Open War on Hidden Fees

- May 21, 2024 • 24:14 The Crypto Comeback

- May 20, 2024 • 31:51 Was the 401(k) a Mistake?

- May 19, 2024 • 33:23 The Sunday Read: ‘Why Did This Guy Put a Song About Me on Spotify?’

- May 17, 2024 • 51:10 The Campus Protesters Explain Themselves

- May 16, 2024 • 30:47 The Make-or-Break Testimony of Michael Cohen

Hosted by Michael Barbaro

Featuring Carl Zimmer

Produced by Alex Stern , Stella Tan , Sydney Harper and Nina Feldman

Edited by MJ Davis Lin

Original music by Elisheba Ittoop , Dan Powell , Marion Lozano , Sophia Lanman and Pat McCusker

Engineered by Alyssa Moxley

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | YouTube

Ever since the discovery of whale songs almost 60 years ago, scientists have been trying to decipher the lyrics.

But sperm whales don’t produce the eerie melodies sung by humpback whales, sounds that became a sensation in the 1960s. Instead, sperm whales rattle off clicks that sound like a cross between Morse code and a creaking door. Carl Zimmer, a science reporter, explains why it’s possible that the whales are communicating in a complex language.

On today’s episode

Carl Zimmer , a science reporter for The New York Times who also writes the Origins column .

Background reading

Scientists find an “alphabet” in whale songs.

These whales still use their vocal cords. But how?

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.

The Daily is made by Rachel Quester, Lynsea Garrison, Clare Toeniskoetter, Paige Cowett, Michael Simon Johnson, Brad Fisher, Chris Wood, Jessica Cheung, Stella Tan, Alexandra Leigh Young, Lisa Chow, Eric Krupke, Marc Georges, Luke Vander Ploeg, M.J. Davis Lin, Dan Powell, Sydney Harper, Mike Benoist, Liz O. Baylen, Asthaa Chaturvedi, Rachelle Bonja, Diana Nguyen, Marion Lozano, Corey Schreppel, Rob Szypko, Elisheba Ittoop, Mooj Zadie, Patricia Willens, Rowan Niemisto, Jody Becker, Rikki Novetsky, John Ketchum, Nina Feldman, Will Reid, Carlos Prieto, Ben Calhoun, Susan Lee, Lexie Diao, Mary Wilson, Alex Stern, Dan Farrell, Sophia Lanman, Shannon Lin, Diane Wong, Devon Taylor, Alyssa Moxley, Summer Thomad, Olivia Natt, Daniel Ramirez and Brendan Klinkenberg.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly. Special thanks to Sam Dolnick, Paula Szuchman, Lisa Tobin, Larissa Anderson, Julia Simon, Sofia Milan, Mahima Chablani, Elizabeth Davis-Moorer, Jeffrey Miranda, Renan Borelli, Maddy Masiello, Isabella Anderson and Nina Lassam.

Carl Zimmer covers news about science for The Times and writes the Origins column . More about Carl Zimmer

Advertisement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Art History Teaching Resources (AHTR) is a peer-populated platform for art history teachers. AHTR is home to a constantly evolving and collectively authored online repository of art history teaching content including, but not limited to, lesson plans, video introductions to museums, book reviews, image clusters, and classroom and museum activities.

Yearlong course with 7 chapters and over 300 lesson activities offers an in-depth overview of art throughout history. Rich graphics, charts, diagrams, animations, and interactive tools help students visualize content. Electronically-graded writing assignments allow students to strengthen their writing skills while saving parents time.

Lesson Plans. These lesson plans help you integrate learning about works of art in your classroom. Select an option below to browse lesson plans by grade, or continue scrolling to see all lesson plans. Lesson plans for elementary school students. Lesson plans for middle school students. Lesson plans for high school students.

Find art lesson plans for high school students (grade 9-12, ages 14 and up). Art curriculum for secondary school teachers. ... For 25 years, our goal has been to make art lessons accessible to those who need them. More than 80 million visitors have used our free collection of ideas in their homes and classrooms and hundreds have joined our ...

Lesson 40 - Art History & Appreciation Activities for High School Art History & Appreciation Activities for High School: Text Lesson Ch 2. Impressionist Painters Lesson Plans Course Progress ...

Art History & Appreciation. Camille Paglia once said 'the only road to freedom is self-education in art.'. Does life imitate art or does art imitate life? It has been said that early humans were ...

Rhythm with Reflective Objects. Colored Pencil Glass. Shattered Values. Monochromatic Painting. Stained Glass. Delphi Stained Glass. {ezoic-ad-1} This is the high school level art lessons category for subject area.

American and European Pop art. We understand the history of humanity through art. From prehistoric depictions of woolly mammoths to contemporary abstraction, artists have addressed their time and place in history and have expressed universal human truths for tens of thousands of years.

Grades 9-12. College/University. Find lesson plans for pre-kindergarten, grades 1-2, grades 3-5, grades 6-8, and grades 9-12, as well as college/university classrooms. Also, explore new resources to support your teaching during the pandemic.

The students set up there background and props then pose for 5 minutes as a curtain is lifted to show them. One student is picked to narrate the history of the artists and explain why the artist created the work. We entered a contest at a museum for middle school and high school students. My favorite rendition was the Three Musicians by Pablo ...

The more art history the better. A couple of years ago, I needed a lesson or activity to use on the last day of the quarter. If you're like me, you prefer the last day of art class to be as stress and mess free as possible. I wanted the activity to include art history and to be fun for my students. I browsed the internet and my art supply ...

Art History. Art history, also called art historiography, historical study of the visual arts, being concerned with identifying, classifying, describing, evaluating, interpreting, and understanding the art products and historic development of the fields of painting, sculpture, architecture, the decorative arts, drawing, printmaking, photography ...

CARLSTADT-EAST RUTHERFORD REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT VISUAL AND PERFORMING ARTS DEPARTMENT ART HISTORY Henry P. Becton Regional High School July 2018 Page 1 of 12 Art History Curriculum Guide Pacing Guide: Art History is a full year course that meets on a rotating basis for three (3) 55-minute blocks and one (1) 40-minute block for every

October 1, 2020. Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo. Art is an important and perhaps unexpected tool in teaching history. Photos, drawings, and paintings can communicate an abundance of information about historical events. Students can analyze pieces of art to assist them in digging deeper into investigating an artist's perspective and decision-making.

By Gerald F. Brommer. This outstanding art history textbook will show students how the visual arts serve to shape and reflect ideas, issues, and themes from the time of the first cave paintings to the twenty-first century. Learn more about this engaging art history textbook and all it can provide for your classroom. Download Flyer.

Summer Assignments 2023. Summer Design Institute 2023. Transcript Request Form. Tech Support. More. ART HISTORY. The required Art History course is taken by all students in their first year at the High School of Art & Design. Students will learn about the major art movements and global artistic traditions from the Old Stone Age to today ...

Pop Art for Today. Relief Printmaking Using Photoshop. Andy Warhol Linoleum Prints. Artist Research Scrapbook. Grant Wood. Ceramics Art History Research. American Gothic Parody. This is the high school level art lessons category for artists. See lessons on this page categorized by artist.

Art history worksheets work well for art or history lessons and encourage young learners to explore their own creativity. Read about Pablo Picasso or try replicating early Egyptian art. Share the gift of imagination with art history worksheets. Art history worksheets help kids learn about the past and present of visual art.

Northern Renaissance Art (1400-1600) Sixteenth-Century Northern Europe and Iberia. Italian Renaissance Art (1400-1600) Southern Baroque: Italy and Spain. Buddhist Art and Architecture in Southeast Asia After 1200. Chinese Art After 1279. Japanese Art After 1392. Art of the Americas After 1300.

Abstract photography. 3D printing art project. Illustrate a poem or piece of literature. Create a pop art portrait. Wire sculpture of an animal or object. Monochromatic artwork using a single color. Paint an abstract interpretation of an emotion. Create a mixed-media piece incorporating various materials.

Study U.S. History online free by downloading OpenStax's United States History textbook and using our accompanying online resources.

Cassidy and Morton sit side-by-side on Tates Creek Road in one of Lexington's high-end neighborhoods. Cassidy received the highest possible rating in Kentucky's school accountability system in ...

Welcome to the home page of Jr. High / Middle School level art lessons! The lessons are now categorized by grade level, subject, integration, art period, artist, and medium. (See below) Do you have a lesson to contribute? Just click on the "Submit a Lesson" link here or in the side column.

Jimalita Tillman continued her daughter on an accelerated track: By the time she was 8, she was taking high school classes. While most 9-year-olds were learning math and reading, Dr. Tillman was ...

More than 100,000 students are enrolled in music classes. More than 100,000 students are also taking a visual arts class. In addition, 10,200 students are taking a theater arts class, and 9,300 ...

transcript. Whales Have an Alphabet Until the 1960s, it was uncertain whether whales made any sounds at all. 2024-05-24T06:00:11-04:00