Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Research Questions & Hypotheses

Generally, in quantitative studies, reviewers expect hypotheses rather than research questions. However, both research questions and hypotheses serve different purposes and can be beneficial when used together.

Research Questions

Clarify the research’s aim (farrugia et al., 2010).

- Research often begins with an interest in a topic, but a deep understanding of the subject is crucial to formulate an appropriate research question.

- Descriptive: “What factors most influence the academic achievement of senior high school students?”

- Comparative: “What is the performance difference between teaching methods A and B?”

- Relationship-based: “What is the relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement?”

- Increasing knowledge about a subject can be achieved through systematic literature reviews, in-depth interviews with patients (and proxies), focus groups, and consultations with field experts.

- Some funding bodies, like the Canadian Institute for Health Research, recommend conducting a systematic review or a pilot study before seeking grants for full trials.

- The presence of multiple research questions in a study can complicate the design, statistical analysis, and feasibility.

- It’s advisable to focus on a single primary research question for the study.

- The primary question, clearly stated at the end of a grant proposal’s introduction, usually specifies the study population, intervention, and other relevant factors.

- The FINER criteria underscore aspects that can enhance the chances of a successful research project, including specifying the population of interest, aligning with scientific and public interest, clinical relevance, and contribution to the field, while complying with ethical and national research standards.

| Feasible | ||

| Interesting | ||

| Novel | ||

| Ethical | ||

| Relevant |

- The P ICOT approach is crucial in developing the study’s framework and protocol, influencing inclusion and exclusion criteria and identifying patient groups for inclusion.

| Population (patients) | ||

| Intervention (for intervention studies only) | ||

| Comparison group | ||

| Outcome of interest | ||

| Time |

- Defining the specific population, intervention, comparator, and outcome helps in selecting the right outcome measurement tool.

- The more precise the population definition and stricter the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the more significant the impact on the interpretation, applicability, and generalizability of the research findings.

- A restricted study population enhances internal validity but may limit the study’s external validity and generalizability to clinical practice.

- A broadly defined study population may better reflect clinical practice but could increase bias and reduce internal validity.

- An inadequately formulated research question can negatively impact study design, potentially leading to ineffective outcomes and affecting publication prospects.

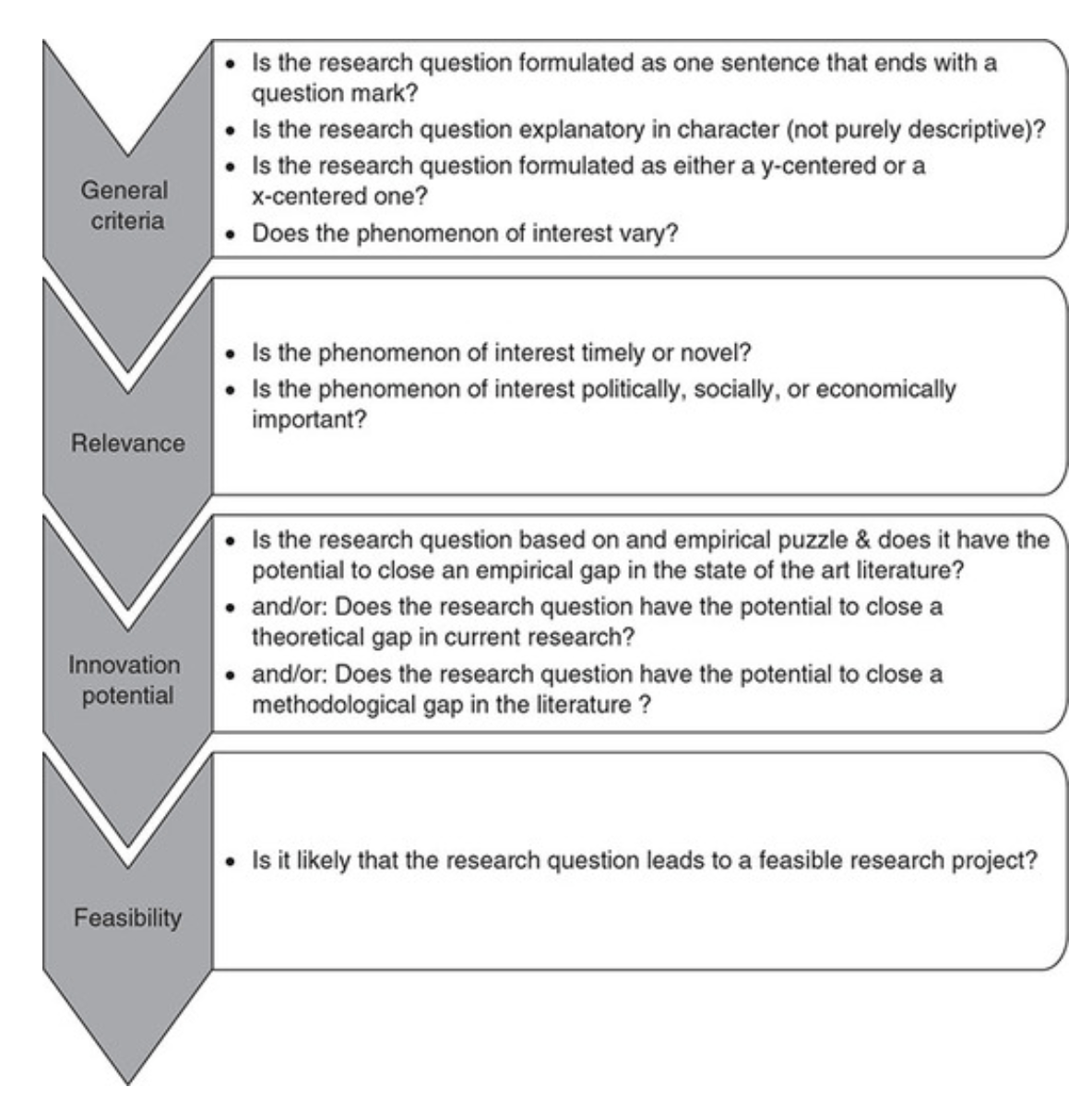

Checklist: Good research questions for social science projects (Panke, 2018)

Research Hypotheses

Present the researcher’s predictions based on specific statements.

- These statements define the research problem or issue and indicate the direction of the researcher’s predictions.

- Formulating the research question and hypothesis from existing data (e.g., a database) can lead to multiple statistical comparisons and potentially spurious findings due to chance.

- The research or clinical hypothesis, derived from the research question, shapes the study’s key elements: sampling strategy, intervention, comparison, and outcome variables.

- Hypotheses can express a single outcome or multiple outcomes.

- After statistical testing, the null hypothesis is either rejected or not rejected based on whether the study’s findings are statistically significant.

- Hypothesis testing helps determine if observed findings are due to true differences and not chance.

- Hypotheses can be 1-sided (specific direction of difference) or 2-sided (presence of a difference without specifying direction).

- 2-sided hypotheses are generally preferred unless there’s a strong justification for a 1-sided hypothesis.

- A solid research hypothesis, informed by a good research question, influences the research design and paves the way for defining clear research objectives.

Types of Research Hypothesis

- In a Y-centered research design, the focus is on the dependent variable (DV) which is specified in the research question. Theories are then used to identify independent variables (IV) and explain their causal relationship with the DV.

- Example: “An increase in teacher-led instructional time (IV) is likely to improve student reading comprehension scores (DV), because extensive guided practice under expert supervision enhances learning retention and skill mastery.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The dependent variable (student reading comprehension scores) is the focus, and the hypothesis explores how changes in the independent variable (teacher-led instructional time) affect it.

- In X-centered research designs, the independent variable is specified in the research question. Theories are used to determine potential dependent variables and the causal mechanisms at play.

- Example: “Implementing technology-based learning tools (IV) is likely to enhance student engagement in the classroom (DV), because interactive and multimedia content increases student interest and participation.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The independent variable (technology-based learning tools) is the focus, with the hypothesis exploring its impact on a potential dependent variable (student engagement).

- Probabilistic hypotheses suggest that changes in the independent variable are likely to lead to changes in the dependent variable in a predictable manner, but not with absolute certainty.

- Example: “The more teachers engage in professional development programs (IV), the more their teaching effectiveness (DV) is likely to improve, because continuous training updates pedagogical skills and knowledge.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis implies a probable relationship between the extent of professional development (IV) and teaching effectiveness (DV).

- Deterministic hypotheses state that a specific change in the independent variable will lead to a specific change in the dependent variable, implying a more direct and certain relationship.

- Example: “If the school curriculum changes from traditional lecture-based methods to project-based learning (IV), then student collaboration skills (DV) are expected to improve because project-based learning inherently requires teamwork and peer interaction.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis presumes a direct and definite outcome (improvement in collaboration skills) resulting from a specific change in the teaching method.

- Example : “Students who identify as visual learners will score higher on tests that are presented in a visually rich format compared to tests presented in a text-only format.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis aims to describe the potential difference in test scores between visual learners taking visually rich tests and text-only tests, without implying a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

- Example : “Teaching method A will improve student performance more than method B.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis compares the effectiveness of two different teaching methods, suggesting that one will lead to better student performance than the other. It implies a direct comparison but does not necessarily establish a causal mechanism.

- Example : “Students with higher self-efficacy will show higher levels of academic achievement.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis predicts a relationship between the variable of self-efficacy and academic achievement. Unlike a causal hypothesis, it does not necessarily suggest that one variable causes changes in the other, but rather that they are related in some way.

Tips for developing research questions and hypotheses for research studies

- Perform a systematic literature review (if one has not been done) to increase knowledge and familiarity with the topic and to assist with research development.

- Learn about current trends and technological advances on the topic.

- Seek careful input from experts, mentors, colleagues, and collaborators to refine your research question as this will aid in developing the research question and guide the research study.

- Use the FINER criteria in the development of the research question.

- Ensure that the research question follows PICOT format.

- Develop a research hypothesis from the research question.

- Ensure that the research question and objectives are answerable, feasible, and clinically relevant.

If your research hypotheses are derived from your research questions, particularly when multiple hypotheses address a single question, it’s recommended to use both research questions and hypotheses. However, if this isn’t the case, using hypotheses over research questions is advised. It’s important to note these are general guidelines, not strict rules. If you opt not to use hypotheses, consult with your supervisor for the best approach.

Farrugia, P., Petrisor, B. A., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2010). Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie , 53 (4), 278–281.

Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D., & Newman, T. B. (2007). Designing clinical research. Philadelphia.

Panke, D. (2018). Research design & method selection: Making good choices in the social sciences. Research Design & Method Selection , 1-368.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls

Wilson fandino.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Wilson Fandino, Anaesthesia Department, St Thomas' Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Westminster Bridge Road, Lambeth, London SE1 7EH, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected]

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

The process of formulating a good research question can be challenging and frustrating. While a comprehensive literature review is compulsory, the researcher usually encounters methodological difficulties in the conduct of the study, particularly if the primary study question has not been adequately selected in accordance with the clinical dilemma that needs to be addressed. Therefore, optimising time and resources before embarking in the design of a clinical protocol can make an impact on the final results of the research project. Researchers have developed effective ways to convey the message of how to build a good research question that can be easily recalled under the acronyms of PICOT (population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and time frame) and FINER (feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant). In line with these concepts, this article highlights the main issues faced by clinicians, when developing a research question.

Key words: Clinical protocols, medical education, medical writing, research design

INTRODUCTION

What is your research question? This is very often one of the first queries made by statisticians, when researchers come up with an interesting idea. In fact, the findings of a study may only acquire relevance if they provide an accurate and unbiased answer to a specific question,[ 1 , 2 ] and it has been suggested that up to one-third of the time spent in the whole process—from the conception of an idea to the publication of the manuscript—could be invested in finding the right primary study question.[ 3 ] Furthermore, selecting a good research question can be a time-consuming and challenging task: in one retrospective study, Mayo et al . reported that 3 out of 10 articles published would have needed a major rewording of the question.[ 1 ] This paper explores some recommendations to consider before starting any research project, and outlines the main difficulties faced by young and experienced clinicians, when it comes time to turn an exciting idea into a valuable and feasible research question.

OPTIMISATION OF TIME AND RESOURCES

Focusing on the primary research question.

The process of developing a new idea usually stems from a dilemma inherent to the clinical practice.[ 2 , 3 , 4 ] However, once the problem has been identified, it is tempting to formulate multiple research questions. Conducting a clinical trial with more than one primary study question would not be feasible. First, because each question may require a different research design, and second, because the necessary statistical power of the study would demand unaffordable sample sizes. It is the duty of editors and reviewers to make sure that authors clearly identify the primary research question, and as a consequence, studies approaching more than one primary research question may not be suitable for publication.

Working in the right environment

Teamwork is essential to find the appropriate research question. Working in the right environment will enable the investigator to interact with colleagues with different backgrounds, and create opportunities to exchange experiences in a collaborative way between clinicians and researchers. Likewise, it is of paramount importance to get involved colleagues with expertise in the field (lead clinicians, education supervisors, research mentors, department chairs, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and ethical consultants, among others), and ask for their guidance.[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]

Evaluating the pertinence of the study

The researcher should wonder if, on the basis of the research question formulated, there is a need for a study to address the problem, as clinical research usually entails a large investment of resources and workforce involvement. Thus, if the answer to the posed clinical question seems to be evident before starting the study, investing in research to address the problem would become superfluous. For example, in a clinical trial, Herzog-Niescery et al . compared laryngeal masks with cuffed and uncuffed tracheal tubes, in the context of surgeons' exposure to sevoflurane, in infants undergoing adenoidectomy. However, it appears obvious that cuffed tracheal tubes are preferred to minimise surgeons' exposure to volatile gases, as authors concluded after recruiting 60 patients.[ 9 ]

Conducting a thorough literature review

Any research project requires the identification of at least one of three problems: the evidence is scarce, the existing literature yields conflicting results, or the results could be improved. Hence, a comprehensive review of the topic is imperative, as it allows the researcher to identify this gap in the literature, formulate a hypothesis and develop a research question.[ 2 ] To this end, it is crucial to be attentive to new ideas, keep the imagination roaming with reflective attitude, and remain sceptical to the new-gained information.[ 4 , 7 ]

Narrowing the research question

A broad research question may encompass an unaffordable extensive topic. For instance, do supraglottic devices provide similar conditions for the visualization of the glottis aperture in a German hospital? Such a general research question usually needs to be narrowed, not only by cutting away unnecessary components (a German hospital is irrelevant in this context), but also by defining a target population, a specific intervention, an alternative treatment or procedure to be compared with the intervention, a measurable primary outcome, and a time frame of the study. In contrast, an example of a good research question would be: among children younger than 1 year of age undergoing elective minor procedures, to what extent the insertion times are different, comparing the Supreme™ laryngeal mask airway (LMA) to Proseal™ LMA, when placed after reaching a BIS index <60?[ 10 ] In this example, the core ingredients of the research question can be easily identified as: children <1 year of age undergoing minor elective procedures, Supreme™ LMA, Proseal™ LMA and insertion times at anaesthetic induction when reaching a BIS index <60. These components are usually gathered in the literature under the acronym of PICOT (population, intervention, comparator, outcome and time frame, respectively).[ 1 , 3 , 5 ]

PICOT FRAMEWORK

Table 1 summarises the foremost questions likely to be addressed when working on PICOT frame.[ 1 , 6 , 8 ] These components are also applicable to observational studies, where the exposure takes place of the intervention.[ 1 , 11 ] Remarkably, if after browsing the title and the abstract of a paper, the reader is not able to clearly identify the PICOT parameters, and elucidate the question posed by the authors, there should be reasonable scepticism regarding the scientific rigor of the work.[ 12 , 13 ] All these elements are crucial in the design and methodology of a clinical trial, as they can affect the feasibility and reliability of results. Having formulated the primary study question in the context of the PICOT framework [ Table 1 ],[ 1 , 6 , 8 ] the researcher should be able to elucidate which design is most suitable for their work, determine what type of data needs to be collected, and write a structured introduction tailored to what they want to know, explicitly mentioning the primary study hypothesis, which should lead to formulate the main research question.[ 1 , 2 , 6 , 8 ]

Key questions to be answered when working with the PICOT framework (population, intervention, comparator, outcome, and time frame) in a clinical research design

| Component | Related questions |

|---|---|

| Population | -What is the target population? -Is the target population narrow or broad? -Is the target population vulnerable? -What are the eligibility criteria? -What is the most appropriate recruitment strategy? |

| Intervention | -What is the intervention? (treatment, diagnostic test, procedure) -Is there any standard of care for the intervention? -Is the intervention the most appropriate for the study design? -Is there a need for standardizing the intervention? -What are the potential side effects of the intervention? -Will potential side effects be recorded? -If there is no intervention, what is the exposure? |

| Comparator | -How has control intervention been chosen? -Are there any ethical concerns related to the use of placebo? -Has a sham intervention been considered? -Will statistical analyses be adjusted for multiple comparisons? |

| Outcome | -What is the primary outcome? -What are the secondary outcomes? -Are the outcomes exploratory, explanatory or confirmatory? -Have surrogate and clinical outcomes been considered? -Are the outcomes validated? -Have safety outcomes been considered? -How are the outcomes going to be measured? -Will the dependent and independent variables be numerical, categorical or ordinal? -Will be enough statistical power to measure secondary outcomes? |

| Time frame | -Is the study designed to be cross -sectional or longitudinal? -How long will the recruitment phase take? -What is the time frame for data collection? -Have frequency and duration of the intervention been specified? -How often will outcomes be measured? -Which strategy will be used to prevent/decrease dropouts? |

Occasionally, the intended population of the study needs to be modified, in order to overcome any potential ethical issues, and/or for the sake of convenience and feasibility of the project. Yet, the researcher must be aware that the external validity of the results may be compromised. As an illustration, in a randomised clinical trial, authors compared the ease of tracheal tube insertion between C-MAC video laryngoscope and direct laryngoscopy, in patients presenting to the emergency department with an indication of rapid sequence intubation. However, owing to the existence of ethical concerns, a substantial amount of patients requiring emergency tracheal intubation, including patients with major maxillofacial trauma and ongoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, had to be excluded from the trial.[ 14 ] In fact, the design of prospective studies to explore this subset of patients can be challenging, not only because of ethical considerations, but because of the low incidence of these cases. In another study, Metterlein et al . compared the glottis visualisation among five different supraglottic airway devices, using fibreroptic-guided tracheal intubation in an adult population. Despite that the study was aimed to explore the ease of intubation in patients with anticipated difficult airway (thus requiring fibreoptic tracheal intubation), authors decided to enrol patients undergoing elective laser treatment for genital condylomas, as a strategy to hasten the recruitment process and optimise resources.[ 15 ]

Intervention

Anaesthetic interventions can be classified into pharmacological (experimental treatment) and nonpharmacological. Among nonpharmacological interventions, the most common include anaesthetic techniques, monitoring instruments and airway devices. For example, it would be appropriate to examine the ease of insertion of Supreme™ LMA, when compared with ProSeal™ LMA. Notwithstanding, a common mistake is the tendency to be focused on the data aimed to be collected (the “stated” objective), rather than the question that needs to be answered (the “latent” objective).[ 1 , 4 ] In one clinical trial, authors stated: “we compared the Supreme™ and ProSeal™ LMAs in infants by measuring their performance characteristics, including insertion features, ventilation parameters, induced changes in haemodynamics, and rates of postoperative complications”.[ 10 ] Here, the research question has been centered on the measurements (insertion characteristics, haemodynamic variables, LMA insertion characteristics, ventilation parameters) rather than the clinical problem that needs to be addressed (is Supreme™ LMA easier to insert than ProSeal™ LMA?).

Comparators in clinical research can also be pharmacological (e.g., gold standard or placebo) or nonpharmacological. Typically, not more than two comparator groups are included in a clinical trial. Multiple comparisons should be generally avoided, unless there is enough statistical power to address the end points of interest, and statistical analyses have been adjusted for multiple testing. For instance, in the aforementioned study of Metterlein et al .,[ 15 ] authors compared five supraglottic airway devices by recruiting only 10--12 participants per group. In spite of the authors' recommendation of using two supraglottic devices based on the results of the study, there was no mention of statistical adjustments for multiple comparisons, and given the small sample size, larger clinical trials will undoubtedly be needed to confirm or refute these findings.[ 15 ]

A clear formulation of the primary outcome results of vital importance in clinical research, as the primary statistical analyses, including the sample size calculation (and therefore, the estimation of the effect size and statistical power), will be derived from the main outcome of interest. While it is clear that using more than one primary outcome would not be appropriate, it would be equally inadequate to include multiple point measurements of the same variable as the primary outcome (e.g., visual analogue scale for pain at 1, 2, 6, and 12 h postoperatively).

Composite outcomes, in which multiple primary endpoints are combined, may make it difficult to draw any conclusions based on the study findings. For example, in a clinical trial, 200 children undergoing ophthalmic surgery were recruited to explore the incidence of respiratory adverse events, when comparing desflurane with sevoflurane, following the removal of flexible LMA during the emergence of the anaesthesia. The primary outcome was the number of respiratory events, including breath holding, coughing, secretions requiring suction, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and mild desaturation.[ 16 ] Should authors had claimed a significant difference between these anaesthetic volatiles, it would have been important to elucidate whether those differences were due to serious adverse events, like laryngospasm or bronchospasm, or the results were explained by any of the other events (e.g., secretions requiring suction). While it is true that clinical trials evaluating the occurrence of adverse events like laryngospasm/bronchospasm,[ 16 , 17 ] or life-threating complications following a tracheal intubation (e.g., inadvertent oesophageal placement, dental damage or injury of the larynx/pharynx)[ 14 ] are almost invariably underpowered, because the incidence of such events is expected to be low, subjective outcomes like coughing or secretions requiring suction should be avoided, as they are highly dependent on the examiner's criteria.[ 16 ]

Secondary outcomes are useful to document potential side effects (e.g., gastric insufflation after placing a supraglottic device), and evaluate the adherence (say, airway leak pressure) and safety of the intervention (for instance, occurrence, or laryngospasm/bronchospasm).[ 17 ] Nevertheless, the problem of addressing multiple secondary outcomes without the adequate statistical power is habitual in medical literature. A good illustration of this issue can be found in a study evaluating the performance of two supraglottic devices in 50 anaesthetised infants and neonates, whereby authors could not draw any conclusions in regard to potential differences in the occurrence of complications, because the sample size calculated made the study underpowered to explore those differences.[ 17 ]

Among PICOT components, the time frame is the most likely to be omitted or inappropriate.[ 1 , 12 ] There are two key aspects of the time component that need to be clearly specified in the research question: the time of measuring the outcome variables (e.g. visual analogue scale for pain at 1, 2, 6, and 12 h postoperatively), and the duration of each measurement (when indicated). The omission of these details in the study protocol might lead to substantial differences in the methodology used. For instance, if a study is designed to compare the insertion times of three different supraglottic devices, and researchers do not specify the exact moment of LMA insertion in the clinical trial protocol (i.e., at the anaesthetic induction after reaching a BIS index < 60), placing an LMA with insufficient depth of anaesthesia would have compromised the internal validity of the results, because inserting a supraglottic device in those patients would have resulted in failed attempts and longer insertion times.[ 10 ]

FINER CRITERIA

A well-elaborated research question may not necessarily be a good question. The proposed study also requires being achievable from both ethical and realistic perspectives, interesting and useful to the clinical practice, and capable to formulate new hypotheses, that may contribute to the generation of knowledge. Researchers have developed an effective way to convey the message of how to build a good research question, that is usually recalled under the acronym of FINER (feasible, interesting, novel, ethical and relevant).[ 5 , 6 , 7 ] Table 2 highlights the main characteristics of FINER criteria.[ 7 ]

Main features of FINER criteria (Feasibility, interest, novelty, ethics, and relevance) to formulate a good research question. Adapted from Cummings et al .[ 7 ]

| Component | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Feasible | -Ensures adequacy of research design -Guarantees adequate funding -Recruits target population strategically -Aims an achievable sample size -Prioritises measurable outcomes -Optimises human and technical resources -Accounts for clinicians commitment -Procures high adherence to the treatment and low rate of dropouts -Opts for appropriate and affordable frame time |

| Interesting | -Engages the interest of principal investigators -Attracts the attention of readers -Presents a different perspective of the problem |

| Novel | -Provides different findings -Generates new hypotheses -Improves methodological flaws of existing studies -Resolves a gap in the existing literature |

| Ethical | -Complies with local ethical committees -Safeguards the main principles of ethical research -Guarantees safety and reversibility of side effects |

| Relevant | -Generates new knowledge -Contributes to improve clinical practice -Stimulates further research -Provides an accurate answer to a specific research question |

Novelty and relevance

Although it is clear that any research project should commence with an accurate literature interpretation, in many instances it represents the start and the end of the research: the reader will soon realise that the answer to several questions can be easily found in the published literature.[ 5 ] When the question overcomes the test of a thorough literature review, the project may become novel (there is a gap in the knowledge, and therefore, there is a need for new evidence on the topic) and relevant (the paper may contribute to change the clinical practice). In this context, it is important to distinguish the difference between statistical significance and clinical relevance: in the aforementioned study of Oba et al .,[ 10 ] despite the means of insertion times were reported as significant for the Supreme™ LMA, as compared with ProSeal™ LMA, the difference found in the insertion times (528 vs. 486 sec, respectively), although reported as significant, had little or no clinical relevance.[ 10 ] Conversely, a statistically significant difference of 12 sec might be of clinical relevance in neonates weighing <5 kg.[ 17 ] Thus, statistical tests must be interpreted in the context of a clinically meaningful effect size, which should be previously defined by the researcher.

Feasibility and ethical aspects

Among FINER criteria, there are two potential barriers that may prevent the successful conduct of the project and publication of the manuscript: feasibility and ethical aspects. These obstacles are usually related to the target population, as discussed above. Feasibility refers not only to the budget but also to the complexity of the design, recruitment strategy, blinding, adequacy of the sample size, measurement of the outcome, time of follow-up of participants, and commitment of clinicians, among others.[ 3 , 7 ] Funding, as a component of feasibility, may also be implicated in the ethical principles of clinical research, because the choice of the primary study question may be markedly influenced by the specific criteria demanded in the interest of potential funders.

Discussing ethical issues with local committees is compulsory, as rules applied might vary among countries.[ 18 ] Potential risks and benefits need to be carefully weighed, based upon the four principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice.[ 19 ] Although many of these issues may be related to the population target (e.g., conducting a clinical trial in patients with ongoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation would be inappropriate, as would be anaesthetising patients undergoing elective LASER treatment for condylomas, to examine the performance of supraglottic airway devices),[ 14 , 15 ] ethical conflicts may also arise from the intervention (particularly those involving the occurrence of side effects or complications, and their potential for reversibility), comparison (e.g., use of placebo or sham procedures),[ 19 ] outcome (surrogate outcomes should be considered in lieu of long term outcomes), or time frame (e.g., unnecessary longer exposition to an intervention). Thus, FINER criteria should not be conceived without a concomitant examination of the PICOT checklist, and consequently, PICOT framework and FINER criteria should not be seen as separated components, but rather complementary ingredients of a good research question.

Undoubtedly, no research project can be conducted if it is deemed unfeasible, and most institutional review boards would not be in a position to approve a work with major ethical problems. Nonetheless, whether or not the findings are interesting, is a subjective matter. Engaging the attention of readers also depends upon a number of factors, including the manner of presenting the problem, the background of the topic, the intended audience, and the reader's expectations. Furthermore, the interest is usually linked to the novelty and relevance of the topic, and it is worth nothing that editors and peer reviewers of high-impact medical journals are usually reluctant to accept any publication, if there is no novelty inherent to the research hypothesis, or there is a lack of relevance in the results.[ 11 ] Nevertheless, a considerable number of papers have been published without any novelty or relevance in the topic addressed. This is probably reflected in a recent survey, according to which only a third of respondents declared to have read thoroughly the most recent papers downloaded, and at least half of those manuscripts remained unread.[ 20 ] The same study reported that up to one-third of papers examined remained uncited after 5 years of publication, and only 20% of papers accounted for 80% of the citations.[ 20 ]

Formulating a good research question can be fascinating, albeit challenging, even for experienced investigators. While it is clear that clinical experience in combination with the accurate interpretation of literature and teamwork are essential to develop new ideas, the formulation of a clinical problem usually requires the compliance with PICOT framework in conjunction with FINER criteria, in order to translate a clinical dilemma into a researchable question. Working in the right environment with the adequate support of experienced researchers, will certainly make a difference in the generation of knowledge. By doing this, a lot of time will be saved in the search of the primary study question, and undoubtedly, there will be more chances to become a successful researcher.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Mayo NE, Asano M, Pamela Barbic S. When is a research question not a research question? J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:513–8. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1150. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Garg R. Methodology for research I. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:640–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.190619. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Riva JJ, Malik KM, Burnie SJ, Endicott AR, Busse JW. What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56:167–71. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Vandenbroucke JP, Pearce N. From ideas to studies: How to get ideas and sharpen them into research questions. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:253–64. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S142940. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Aslam S, Emmanuel P. Formulating a researchable question: A critical step for facilitating good clinical research. Indian J Sex Trans Dis. 2010;31:47–50. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.69003. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surgery. 2010;53:278–81. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB. Designing Clinical Research. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2013. Conceiving the research question and developing the study plan; pp. 14–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Durbin CG. How to come up with a good research question: Framing the hypothesis. Respir Care. 2004;49:1195–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Herzog-Niescery J, Gude P, Gahlen F, Seipp HM, Bartz H, Botteck NM, et al. Surgeons' exposure to sevoflurane during paediatric adenoidectomy: A comparison of three airway devices. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:915–20. doi: 10.1111/anae.13515. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Oba S, Turk HS, Isil CT, Erdogan H, Sayin P, Dokucu AI. Comparison of the Supreme™ and ProSeal™ laryngeal mask airways in infants: A prospective randomised clinical study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17:125. doi: 10.1186/s12871-017-0418-z. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Davidson A, Delbridge E. How to write a research paper. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;22:61–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Thabane L, Thomas T, Ye C, Paul J. Posing the research question: Not so simple. Can J Anesth. 2009;56:71–9. doi: 10.1007/s12630-008-9007-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Rios LP, Ye C, Thabane L. Association between framing of the research question using the PICOT format and reporting quality of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-11. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Sulser S, Ubmann D, Schlaepfer M, Brueesch M, Goliasch G, Seifert B, et al. C-MAC videolaryngoscope compared with direct laryngoscopy for rapid sequence intubation in an emergency department: A randomised clinical trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol (EJA) 2016;33:943–8. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000525. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Metterlein T, Dintenfelder A, Plank C, Graf B, Roth G. A comparison of various supraglottic airway devices for fiberoptical guided tracheal intubation. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2017;67:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2015.09.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Kim EH, Song IK, Lee JH, Kim HS, Kim HC, Yoon SH, et al. Desflurane versus sevoflurane in pediatric anesthesia with a laryngeal mask airway: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7977. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007977. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Kayhan GE, Begec Z, Sanli M, Gedik E, Durmus M. Performance of size 1 I-gel compared with size 1 ProSeal laryngeal mask in anesthetized infants and neonates. Scientific World Journal. 2015;2015:426186. doi: 10.1155/2015/426186. doi: 10.1155/2015/426186. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Hall R, McKnight D, Cox R, Coonan T. Guidelines on the ethics of clinical research in anesthesia. Can J Anesth. 2011;58:1115–24. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9596-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Johnson R, Watkinson A, Mabe M. The STM report: An overview of scientific and scholarly journals publishing. International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers [Internet] 2018. [Last cited on 2019 Jan 05]. Available from: https://www.stm.assoc.org/2018_10_04_STM_Report_2018.pdf .

- View on publisher site

- PDF (364.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on October 26, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

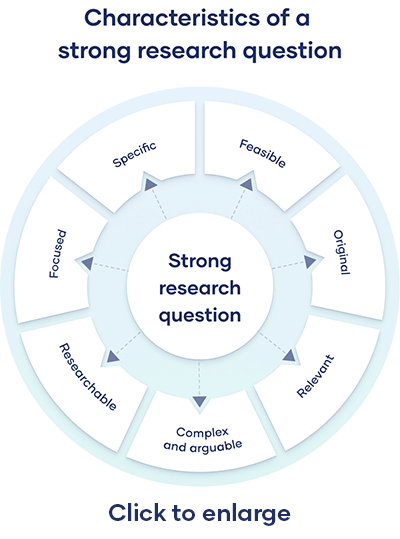

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, using sub-questions to strengthen your main research question, research questions quiz, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

| Research question formulations | |

|---|---|

| Describing and exploring | |

| Explaining and testing | |

| Evaluating and acting | is X |

Using your research problem to develop your research question

| Example research problem | Example research question(s) |

|---|---|

| Teachers at the school do not have the skills to recognize or properly guide gifted children in the classroom. | What practical techniques can teachers use to better identify and guide gifted children? |

| Young people increasingly engage in the “gig economy,” rather than traditional full-time employment. However, it is unclear why they choose to do so. | What are the main factors influencing young people’s decisions to engage in the gig economy? |

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Focused on a single topic | Your central research question should work together with your research problem to keep your work focused. If you have multiple questions, they should all clearly tie back to your central aim. |

| Answerable using | Your question must be answerable using and/or , or by reading scholarly sources on the to develop your argument. If such data is impossible to access, you likely need to rethink your question. |

| Not based on value judgements | Avoid subjective words like , , and . These do not give clear criteria for answering the question. |

Feasible and specific

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Answerable within practical constraints | Make sure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific. |

| Uses specific, well-defined concepts | All the terms you use in the research question should have clear meanings. Avoid vague language, jargon, and too-broad ideas. |

| Does not demand a conclusive solution, policy, or course of action | Research is about informing, not instructing. Even if your project is focused on a practical problem, it should aim to improve understanding rather than demand a ready-made solution. If ready-made solutions are necessary, consider conducting instead. Action research is a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as it is solved. In other words, as its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time. |

Complex and arguable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cannot be answered with or | Closed-ended, / questions are too simple to work as good research questions—they don’t provide enough for robust investigation and discussion. |

| Cannot be answered with easily-found facts | If you can answer the question through a single Google search, book, or article, it is probably not complex enough. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation prior to providing an answer. |

Relevant and original

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Addresses a relevant problem | Your research question should be developed based on initial reading around your . It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline. |

| Contributes to a timely social or academic debate | The question should aim to contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on. |

| Has not already been answered | You don’t have to ask something that nobody has ever thought of before, but your question should have some aspect of originality. For example, you can focus on a specific location, or explore a new angle. |

Chances are that your main research question likely can’t be answered all at once. That’s why sub-questions are important: they allow you to answer your main question in a step-by-step manner.

Good sub-questions should be:

- Less complex than the main question

- Focused only on 1 type of research

- Presented in a logical order

Here are a few examples of descriptive and framing questions:

- Descriptive: According to current government arguments, how should a European bank tax be implemented?

- Descriptive: Which countries have a bank tax/levy on financial transactions?

- Framing: How should a bank tax/levy on financial transactions look at a European level?

Keep in mind that sub-questions are by no means mandatory. They should only be asked if you need the findings to answer your main question. If your main question is simple enough to stand on its own, it’s okay to skip the sub-question part. As a rule of thumb, the more complex your subject, the more sub-questions you’ll need.

Try to limit yourself to 4 or 5 sub-questions, maximum. If you feel you need more than this, it may be indication that your main research question is not sufficiently specific. In this case, it’s is better to revisit your problem statement and try to tighten your main question up.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (“ x affects y because …”).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses . In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Formulating a main research question can be a difficult task. Overall, your question should contribute to solving the problem that you have defined in your problem statement .

However, it should also fulfill criteria in three main areas:

- Researchability

- Feasibility and specificity

- Relevance and originality

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 21). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved October 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-questions/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to define a research problem | ideas & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, 10 research question examples to guide your research project, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Hypothesis: What It Is, Types + How to Develop?

A research study starts with a question. Researchers worldwide ask questions and create research hypotheses. The effectiveness of research relies on developing a good research hypothesis. Examples of research hypotheses can guide researchers in writing effective ones.

In this blog, we’ll learn what a research hypothesis is, why it’s important in research, and the different types used in science. We’ll also guide you through creating your research hypothesis and discussing ways to test and evaluate it.

What is a Research Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is like a guess or idea that you suggest to check if it’s true. A research hypothesis is a statement that brings up a question and predicts what might happen.

It’s really important in the scientific method and is used in experiments to figure things out. Essentially, it’s an educated guess about how things are connected in the research.

A research hypothesis usually includes pointing out the independent variable (the thing they’re changing or studying) and the dependent variable (the result they’re measuring or watching). It helps plan how to gather and analyze data to see if there’s evidence to support or deny the expected connection between these variables.

Importance of Hypothesis in Research

Hypotheses are really important in research. They help design studies, allow for practical testing, and add to our scientific knowledge. Their main role is to organize research projects, making them purposeful, focused, and valuable to the scientific community. Let’s look at some key reasons why they matter:

- A research hypothesis helps test theories.

A hypothesis plays a pivotal role in the scientific method by providing a basis for testing existing theories. For example, a hypothesis might test the predictive power of a psychological theory on human behavior.

- It serves as a great platform for investigation activities.

It serves as a launching pad for investigation activities, which offers researchers a clear starting point. A research hypothesis can explore the relationship between exercise and stress reduction.

- Hypothesis guides the research work or study.

A well-formulated hypothesis guides the entire research process. It ensures that the study remains focused and purposeful. For instance, a hypothesis about the impact of social media on interpersonal relationships provides clear guidance for a study.

- Hypothesis sometimes suggests theories.

In some cases, a hypothesis can suggest new theories or modifications to existing ones. For example, a hypothesis testing the effectiveness of a new drug might prompt a reconsideration of current medical theories.

- It helps in knowing the data needs.

A hypothesis clarifies the data requirements for a study, ensuring that researchers collect the necessary information—a hypothesis guiding the collection of demographic data to analyze the influence of age on a particular phenomenon.

- The hypothesis explains social phenomena.

Hypotheses are instrumental in explaining complex social phenomena. For instance, a hypothesis might explore the relationship between economic factors and crime rates in a given community.

- Hypothesis provides a relationship between phenomena for empirical Testing.

Hypotheses establish clear relationships between phenomena, paving the way for empirical testing. An example could be a hypothesis exploring the correlation between sleep patterns and academic performance.

- It helps in knowing the most suitable analysis technique.

A hypothesis guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate analysis techniques for their data. For example, a hypothesis focusing on the effectiveness of a teaching method may lead to the choice of statistical analyses best suited for educational research.

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a specific idea that you can test in a study. It often comes from looking at past research and theories. A good hypothesis usually starts with a research question that you can explore through background research. For it to be effective, consider these key characteristics:

- Clear and Focused Language: A good hypothesis uses clear and focused language to avoid confusion and ensure everyone understands it.

- Related to the Research Topic: The hypothesis should directly relate to the research topic, acting as a bridge between the specific question and the broader study.

- Testable: An effective hypothesis can be tested, meaning its prediction can be checked with real data to support or challenge the proposed relationship.

- Potential for Exploration: A good hypothesis often comes from a research question that invites further exploration. Doing background research helps find gaps and potential areas to investigate.

- Includes Variables: The hypothesis should clearly state both the independent and dependent variables, specifying the factors being studied and the expected outcomes.

- Ethical Considerations: Check if variables can be manipulated without breaking ethical standards. It’s crucial to maintain ethical research practices.

- Predicts Outcomes: The hypothesis should predict the expected relationship and outcome, acting as a roadmap for the study and guiding data collection and analysis.

- Simple and Concise: A good hypothesis avoids unnecessary complexity and is simple and concise, expressing the essence of the proposed relationship clearly.

- Clear and Assumption-Free: The hypothesis should be clear and free from assumptions about the reader’s prior knowledge, ensuring universal understanding.

- Observable and Testable Results: A strong hypothesis implies research that produces observable and testable results, making sure the study’s outcomes can be effectively measured and analyzed.

When you use these characteristics as a checklist, it can help you create a good research hypothesis. It’ll guide improving and strengthening the hypothesis, identifying any weaknesses, and making necessary changes. Crafting a hypothesis with these features helps you conduct a thorough and insightful research study.

Types of Research Hypotheses

The research hypothesis comes in various types, each serving a specific purpose in guiding the scientific investigation. Knowing the differences will make it easier for you to create your own hypothesis. Here’s an overview of the common types:

01. Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states that there is no connection between two considered variables or that two groups are unrelated. As discussed earlier, a hypothesis is an unproven assumption lacking sufficient supporting data. It serves as the statement researchers aim to disprove. It is testable, verifiable, and can be rejected.

For example, if you’re studying the relationship between Project A and Project B, assuming both projects are of equal standard is your null hypothesis. It needs to be specific for your study.

02. Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is basically another option to the null hypothesis. It involves looking for a significant change or alternative that could lead you to reject the null hypothesis. It’s a different idea compared to the null hypothesis.

When you create a null hypothesis, you’re making an educated guess about whether something is true or if there’s a connection between that thing and another variable. If the null view suggests something is correct, the alternative hypothesis says it’s incorrect.

For instance, if your null hypothesis is “I’m going to be $1000 richer,” the alternative hypothesis would be “I’m not going to get $1000 or be richer.”

03. Directional Hypothesis

The directional hypothesis predicts the direction of the relationship between independent and dependent variables. They specify whether the effect will be positive or negative.

If you increase your study hours, you will experience a positive association with your exam scores. This hypothesis suggests that as you increase the independent variable (study hours), there will also be an increase in the dependent variable (exam scores).

04. Non-directional Hypothesis

The non-directional hypothesis predicts the existence of a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect. It suggests that there will be a significant difference or relationship, but it does not predict the nature of that difference.

For example, you will find no notable difference in test scores between students who receive the educational intervention and those who do not. However, once you compare the test scores of the two groups, you will notice an important difference.

05. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis predicts a relationship between one dependent variable and one independent variable without specifying the nature of that relationship. It’s simple and usually used when we don’t know much about how the two things are connected.

For example, if you adopt effective study habits, you will achieve higher exam scores than those with poor study habits.

06. Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is an idea that specifies a relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. It is a more detailed idea than a simple hypothesis.

While a simple view suggests a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship between two things, a complex hypothesis involves many factors and how they’re connected to each other.

For example, when you increase your study time, you tend to achieve higher exam scores. The connection between your study time and exam performance is affected by various factors, including the quality of your sleep, your motivation levels, and the effectiveness of your study techniques.

If you sleep well, stay highly motivated, and use effective study strategies, you may observe a more robust positive correlation between the time you spend studying and your exam scores, unlike those who may lack these factors.

07. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis proposes a connection between two things without saying that one causes the other. Basically, it suggests that when one thing changes, the other changes too, but it doesn’t claim that one thing is causing the change in the other.

For example, you will likely notice higher exam scores when you increase your study time. You can recognize an association between your study time and exam scores in this scenario.

Your hypothesis acknowledges a relationship between the two variables—your study time and exam scores—without asserting that increased study time directly causes higher exam scores. You need to consider that other factors, like motivation or learning style, could affect the observed association.

08. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables. It suggests that changes in one variable directly cause changes in another variable.

For example, when you increase your study time, you experience higher exam scores. This hypothesis suggests a direct cause-and-effect relationship, indicating that the more time you spend studying, the higher your exam scores. It assumes that changes in your study time directly influence changes in your exam performance.

09. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement based on things we can see and measure. It comes from direct observation or experiments and can be tested with real-world evidence. If an experiment proves a theory, it supports the idea and shows it’s not just a guess. This makes the statement more reliable than a wild guess.

For example, if you increase the dosage of a certain medication, you might observe a quicker recovery time for patients. Imagine you’re in charge of a clinical trial. In this trial, patients are given varying dosages of the medication, and you measure and compare their recovery times. This allows you to directly see the effects of different dosages on how fast patients recover.

This way, you can create a research hypothesis: “Increasing the dosage of a certain medication will lead to a faster recovery time for patients.”

10. Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement or assumption about a population parameter that is the subject of an investigation. It serves as the basis for statistical analysis and testing. It is often tested using statistical methods to draw inferences about the larger population.

In a hypothesis test, statistical evidence is collected to either reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis due to insufficient evidence.

For example, let’s say you’re testing a new medicine. Your hypothesis could be that the medicine doesn’t really help patients get better. So, you collect data and use statistics to see if your guess is right or if the medicine actually makes a difference.

If the data strongly shows that the medicine does help, you say your guess was wrong, and the medicine does make a difference. But if the proof isn’t strong enough, you can stick with your original guess because you didn’t get enough evidence to change your mind.

How to Develop a Research Hypotheses?

Step 1: identify your research problem or topic..

Define the area of interest or the problem you want to investigate. Make sure it’s clear and well-defined.

Start by asking a question about your chosen topic. Consider the limitations of your research and create a straightforward problem related to your topic. Once you’ve done that, you can develop and test a hypothesis with evidence.

Step 2: Conduct a literature review

Review existing literature related to your research problem. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge in the field, identify gaps, and build a foundation for your hypothesis. Consider the following questions:

- What existing research has been conducted on your chosen topic?

- Are there any gaps or unanswered questions in the current literature?

- How will the existing literature contribute to the foundation of your research?

Step 3: Formulate your research question

Based on your literature review, create a specific and concise research question that addresses your identified problem. Your research question should be clear, focused, and relevant to your field of study.

Step 4: Identify variables

Determine the key variables involved in your research question. Variables are the factors or phenomena that you will study and manipulate to test your hypothesis.

- Independent Variable: The variable you manipulate or control.

- Dependent Variable: The variable you measure to observe the effect of the independent variable.

Step 5: State the Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no significant difference or effect. It serves as a baseline for comparison with the alternative hypothesis.

Step 6: Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis

Choose research methods that align with your study objectives, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies. The selected methods enable you to test your research hypothesis effectively.

Creating a research hypothesis usually takes more than one try. Expect to make changes as you collect data. It’s normal to test and say no to a few hypotheses before you find the right answer to your research question.

Testing and Evaluating Hypotheses

Testing hypotheses is a really important part of research. It’s like the practical side of things. Here, real-world evidence will help you determine how different things are connected. Let’s explore the main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis.

Before testing, clearly articulate your research hypothesis. This involves framing both a null hypothesis, suggesting no significant effect or relationship, and an alternative hypothesis, proposing the expected outcome.

- Collect data strategically.

Plan how you will gather information in a way that fits your study. Make sure your data collection method matches the things you’re studying.

Whether through surveys, observations, or experiments, this step demands precision and adherence to the established methodology. The quality of data collected directly influences the credibility of study outcomes.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test.

Choose a statistical test that aligns with the nature of your data and the hypotheses being tested. Whether it’s a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, or regression analysis, selecting the right statistical tool is paramount for accurate and reliable results.

- Decide if your idea was right or wrong.

Following the statistical analysis, evaluate the results in the context of your null hypothesis. You need to decide if you should reject your null hypothesis or not.

- Share what you found.

When discussing what you found in your research, be clear and organized. Say whether your idea was supported or not, and talk about what your results mean. Also, mention any limits to your study and suggest ideas for future research.

The Role of QuestionPro to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

QuestionPro is a survey and research platform that provides tools for creating, distributing, and analyzing surveys. It plays a crucial role in the research process, especially when you’re in the initial stages of hypothesis development. Here’s how QuestionPro can help you to develop a good research hypothesis:

- Survey design and data collection: You can use the platform to create targeted questions that help you gather relevant data.

- Exploratory research: Through surveys and feedback mechanisms on QuestionPro, you can conduct exploratory research to understand the landscape of a particular subject.

- Literature review and background research: QuestionPro surveys can collect sample population opinions, experiences, and preferences. This data and a thorough literature evaluation can help you generate a well-grounded hypothesis by improving your research knowledge.

- Identifying variables: Using targeted survey questions, you can identify relevant variables related to their research topic.

- Testing assumptions: You can use surveys to informally test certain assumptions or hypotheses before formalizing a research hypothesis.

- Data analysis tools: QuestionPro provides tools for analyzing survey data. You can use these tools to identify the collected data’s patterns, correlations, or trends.

- Refining your hypotheses: As you collect data through QuestionPro, you can adjust your hypotheses based on the real-world responses you receive.

A research hypothesis is like a guide for researchers in science. It’s a well-thought-out idea that has been thoroughly tested. This idea is crucial as researchers can explore different fields, such as medicine, social sciences, and natural sciences. The research hypothesis links theories to real-world evidence and gives researchers a clear path to explore and make discoveries.

QuestionPro Research Suite is a helpful tool for researchers. It makes creating surveys, collecting data, and analyzing information easily. It supports all kinds of research, from exploring new ideas to forming hypotheses. With a focus on using data, it helps researchers do their best work.

Are you interested in learning more about QuestionPro Research Suite? Take advantage of QuestionPro’s free trial to get an initial look at its capabilities and realize the full potential of your research efforts.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

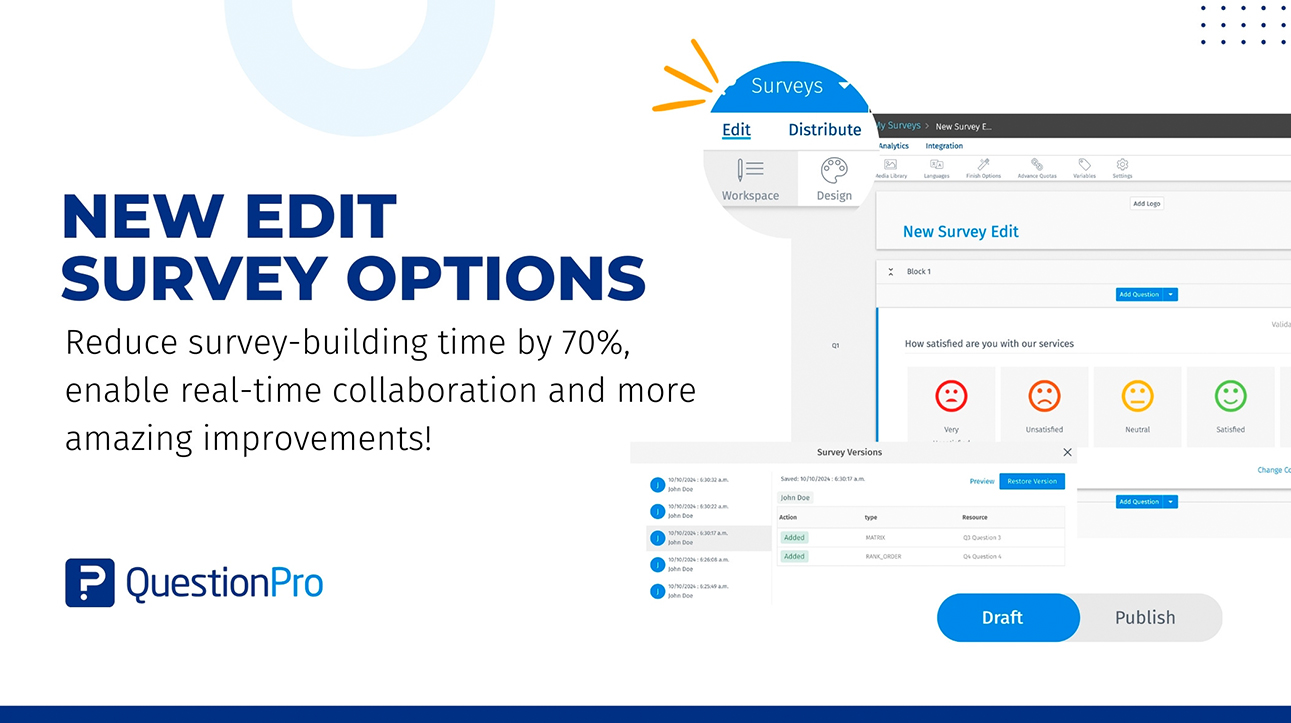

Edit survey: A new way of survey building and collaboration

Oct 10, 2024

Pulse Surveys vs Annual Employee Surveys: Which to Use

Oct 4, 2024

Employee Perception Role in Organizational Change

Oct 3, 2024

Mixed Methods Research: Overview of Designs and Techniques

Oct 2, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Quantitative Research in Mass Communications : R and RStudio

7 formulating research questions and hypotheses, 7.1 introduction to research questions and hypotheses.

In the realm of academic research, particularly within the field of mass communications, the formulation of research questions and hypotheses is a foundational step that sets the direction and scope of a study. These elements are crucial not only for guiding the research process but also for defining the study’s objectives and expectations. This section highlights the significance of research questions and hypotheses and elucidates the role they play in framing a study.

The Importance of Research Questions and Hypotheses in Guiding Research

Defining the Research Focus: Research questions serve as the cornerstone of any study, clearly outlining the specific issue or phenomenon that the research aims to explore. They help narrow down the broad area of interest into a focused inquiry that can be systematically investigated.

Guiding Methodology: The nature of the research question—whether it seeks to describe, compare, or determine cause and effect—directly influences the choice of research design, methods, and analysis techniques. Well-formulated questions ensure that the research methodology is appropriately aligned with the study’s objectives.

Facilitating Hypothesis Formulation: In quantitative research, hypotheses often stem from the research questions, proposing specific predictions or expectations based on theoretical foundations or previous studies. Hypotheses provide a testable statement that guides the empirical investigation and analysis.

7.1.1 Overview of the Role These Elements Play in Framing a Study

Structuring the Research Framework: Together, research questions and hypotheses establish the conceptual framework for a study, defining its boundaries and specifying the variables of interest. This framework serves as a blueprint, guiding all subsequent steps of the research process.

Informing Literature Review: Research questions and hypotheses inform the scope and focus of the literature review, directing attention to relevant theories, concepts, and empirical findings. This ensures that the review is tightly integrated with the study’s aims and contributes to building a solid theoretical foundation.

Determining Data Collection and Analysis: The formulation of research questions and hypotheses has direct implications for data collection methods, sampling strategies, and analytical techniques. They dictate what data are needed, how they should be collected, and the statistical tests or analytical approaches required to address the research questions and test the hypotheses.

Communicating the Study’s Purpose: Research questions and hypotheses effectively communicate the purpose and direction of the study to the academic community, stakeholders, and the broader public. They articulate the study’s contribution to knowledge, its relevance to theoretical debates or practical issues, and the potential implications of the findings.

In summary, research questions and hypotheses are indispensable components of the research process, serving as the guiding light for the entire study. They provide clarity, direction, and purpose, ensuring that the research is coherent, focused, and methodologically sound. By meticulously crafting these elements, researchers in mass communications lay the groundwork for meaningful and impactful studies that advance our understanding of complex media landscapes and communication dynamics.

7.2 Understanding Research Questions

Research questions are the foundation of any scholarly inquiry, guiding the direction and focus of the study. In mass communications research, where topics can range from analyzing media effects to understanding audience behaviors, formulating effective research questions is crucial for defining the scope and objectives of a study. This section delves into the definition and characteristics of a good research question, distinguishes between exploratory and descriptive research questions, and discusses strategies for developing clear and focused questions.

Definition and Characteristics of a Good Research Question

Definition: A research question is a clearly formulated question that outlines the issue or problem your study aims to address. It sets the stage for the research design, data collection, and analysis, directing the inquiry toward a specific goal.

Characteristics of a Good Research Question:

- Clarity: It should be clearly stated, avoiding ambiguity and ensuring that the research focus is understandable to others.

- Relevance: The question should be significant to the field of study, addressing gaps in the literature or emerging issues in mass communications.

- Researchability: It must be possible to answer the question through empirical investigation, using available research methods and tools.

- Specificity: A good question is specific, targeting a particular aspect of the broader topic to make the research manageable and focused.

Distinction Between Exploratory and Descriptive Research Questions

Exploratory Research Questions: These questions are used when little is known about the topic or phenomenon. Exploratory questions aim to investigate and gain insights into a subject, seeking to understand how or why something happens. In mass communications, an exploratory question might ask, “How do emerging social media platforms influence political engagement among young adults?”

Descriptive Research Questions: Descriptive questions aim to describe the characteristics or features of a subject. They are used when the goal is to provide an accurate representation or count of a phenomenon. A descriptive research question in mass communications might be, “What are the predominant themes in news coverage of environmental issues?”

Developing Clear and Focused Research Questions

- Specificity: Your research question should be narrowly tailored to address a specific issue within the broader field of mass communications. This specificity helps in defining the study’s scope and focusing the research efforts.