- National Curriculum Standards for Social Studies: Introduction

- NCSS Social Studies Standards

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR THE SOCIAL STUDIES (NCSS) first published national curriculum standards in 1994. Since then, the social studies standards have been widely and successfully used as a framework for teachers, schools, districts, states, and other nations as a tool for curriculum alignment and development. However, much has changed in the world and in education since these curriculum standards were published. This revision aims to provide a framework for teaching, learning, and assessment in social studies that includes a sharper articulation of curriculum objectives, and reflects greater consistency across the different sections of the document. It incorporates current research and suggestions for improvement from many experienced practitioners. These revised standards reflect a desire to continue and build upon the expectations established in the original standards for effective social studies in the grades from pre-K through 12.

The approach originally taken in these curriculum standards has been well received in the United States and internationally; therefore, while the document has been revised and updated, it retains the same organization around major themes basic to social studies learning. As in the original document, the framework moves beyond any single approach to teaching and learning and promotes much more than the transmission of knowledge alone. These updated standards retain the central emphasis of the original document on supporting students to become active participants in the learning process.

What Is Social Studies and Why Is It Important? National Council for the Social Studies, the largest professional association for social studies educators in the world, defines social studies as:

…the integrated study of the social sciences and humanities to promote civic competence. Within the school program, social studies provides coordinated, systematic study drawing upon such disciplines as anthropology, archaeology, economics, geography, history, law, philosophy, political science, psychology, religion, and sociology, as well as appropriate content from the humanities, mathematics, and natural sciences. The primary purpose of social studies is to help young people make informed and reasoned decisions for the public good as citizens of a culturally diverse, democratic society in an interdependent world. 1

The aim of social studies is the promotion of civic competence—the knowledge, intellectual processes, and democratic dispositions required of students to be active and engaged participants in public life. Although civic competence is not the only responsibility of social studies nor is it exclusive to the field, it is more central to social studies than to any other subject area in schools. By making civic competence a central aim, NCSS has long recognized the importance of educating students who are committed to the ideas and values of democracy. Civic competence rests on this commitment to democratic values, and requires the abilities to use knowledge about one’s community, nation, and world; apply inquiry processes; and employ skills of data collection and analysis, collaboration, decision-making, and problem-solving. Young people who are knowledgeable, skillful, and committed to democracy are necessary to sustaining and improving our democratic way of life, and participating as members of a global community.

The civic mission of social studies demands the inclusion of all students—addressing cultural, linguistic, and learning diversity that includes similarities and differences based on race, ethnicity, language, religion, gender, sexual orientation, exceptional learning needs, and other educationally and personally significant characteristics of learners. Diversity among learners embodies the democratic goal of embracing pluralism to make social studies classrooms laboratories of democracy.

In democratic classrooms and nations, deep understanding of civic issues—such as immigration, economic problems, and foreign policy—involves several disciplines. Social studies marshals the disciplines to this civic task in various forms. These important issues can be taught in one class, often designated “social studies,” that integrates two or more disciplines. On the other hand, issues can also be taught in separate discipline-based classes (e.g., history or geography). These standards are intended to be useful regardless of organizational or instructional approach (for example, a problem-solving approach, an approach centered on controversial issues, a discipline-based approach, or some combination of approaches). Specific decisions about curriculum organization are best made at the local level. To this end, the standards provide a framework for effective social studies within various curricular perspectives.

What is the Purpose of the National Curriculum Standards? The NCSS curriculum standards provide a framework for professional deliberation and planning about what should occur in a social studies program in grades pre-K through 12. The framework provides ten themes that represent a way of organizing knowledge about the human experience in the world. The learning expectations, at early, middle, and high school levels, describe purposes, knowledge, and intellectual processes that students should exhibit in student products (both within and beyond classrooms) as the result of the social studies curriculum. These curriculum standards represent a holistic lens through which to view disciplinary content standards and state standards, as well as other curriculum planning documents. They provide the framework needed to educate students for the challenges of citizenship in a democracy.

The Ten Themes are organizing strands for social studies programs. The ten themes are:

1 CULTURE 2 TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE 3 PEOPLE, PLACES, AND ENVIRONMENTS 4 INDIVIDUAL DEVELOPMENT AND IDENTITY 5 INDIVIDUALS, GROUPS, AND INSTITUTIONS 6 POWER, AUTHORITY, AND GOVERNANCE 7 PRODUCTION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSUMPTION 8 SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND SOCIETY 9 GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 10 CIVIC IDEALS AND PRACTICES

The themes represent strands that should thread through a social studies program, from grades pre-K through 12, as appropriate at each level. While at some grades and for some courses, specific themes will be more dominant than others, all the themes are highly interrelated. To understand culture ( Theme 1 ), for example, students also need to understand the theme of time, continuity, and change ( Theme 2 ); the relationships between people, places, and environments ( Theme 3 ); and the role of civic ideals and practices ( Theme 10 ). To understand power, authority, and governance ( Theme 6 ), students need to understand different cultures ( Theme 1 ); the relationships between people, places, and environments ( Theme 3 ); and the interconnections among individuals, groups, and institutions ( Theme 5 ). History is not confined to TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE ( Theme 2 ) because historical knowledge contributes to the understanding of all the other themes; similarly, geographic skills and knowledge can be found in more than ( Theme 3 ).

The thematic strands draw from all the social science disciplines and other related disciplines and fields of study to provide a framework for social studies curriculum design and development. The themes provide a basis from which social studies educators can more fully develop their programs by consulting the details of national content standards developed for history, geography, civics, economics, psychology, and other fields, 2 as well as content standards developed by their states. Thus, the NCSS social studies curriculum standards serve as the organizing basis for any social studies program in grades pre-K through 12. Content standards for the disciplines, as well as other standards, such as those for instructional technology,3 provide additional detail for curriculum design and development.

Snapshots of Practice provide educators with images of how the standards might look when enacted in classrooms.** Typically a Snapshot illustrates a particular Theme and one or more Learning Expectations; however, the Snapshot may also touch on other related Themes and Learning Expectations. For example, a lesson focused on the Theme of TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE in a world history class dealing with early river valley civilizations would certainly engage the theme of PEOPLE, PLACES, AND ENVIRONMENTS as well as that of TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE . These Snapshots also suggest ways in which Learning Expectations shape practice, emphasize skills and strategies, and provide examples of both ongoing and culminating assessment.

Who Can Use the Social Studies Standards? The social studies curriculum standards offer educators, parents, and policymakers the essential conceptual framework for curriculum design and development to prepare informed and active citizens. The standards represent the framework for professional deliberation and planning of the social studies curriculum for grades from pre-K through 12. They address overall curriculum development; while specific discipline-based content standards serve as guides for specific content that fits within this framework. Classroom teachers, teacher educators, and state, district, and school administrators can use this document as a starting point for the systematic design and development of an effective social studies curriculum for grades from pre-K through 12.

**Almost all of these Snapshots were crafted by the Task Force members, or (in the case of Snapshots reproduced from the earlier standards) by members of the Task Force that developed the standards published in 1994. The basis for the creation of Snapshots has been the personal experiences of members of the Task Forces as teachers, teacher educators, and supervisors. The Snapshots are designed to reflect the various ways in which performance indicators can be used in actual practice.

The publications of National Council for the Social Studies, including its journals Social Education and Social Studies and the Young Learner (for grades K-6), as well as books, regularly include lesson plans and other guidelines for implementing the social studies standards. A video library providing snapshots of the social studies standards in actual classrooms and linked to standards themes, which was produced by WGBH Educational Foundation, can be accessed at the Annenberg Media website at https://www.learner.org/resources/series166.html

How Do Content Standards Differ from Curriculum Standards? What is the Relationship Between Them? Content standards (e.g., standards for civics, history, economics, geography, and psychology) provide a detailed description of content and methodology considered central to a specific discipline by experts, including educators, in that discipline. The NCSS curriculum standards instead provide a set of principles by which content can be selected and organized to build a viable, valid, and defensible social studies curriculum for grades from pre-K through 12. They are not a substitute for content standards, but instead provide the necessary framework for the implementation of content standards. They address issues that are broader and deeper than the identification of content specific to a particular discipline. The ten themes and their elaboration identify the desirable range of social studies programs. The detailed descriptions of purposes, knowledge, processes, and products identify the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that social studies programs should provide students as part of their education for citizenship. The social studies curriculum standards should remind curriculum developers and others of the overarching purposes of social studies programs in grades pre-K through 12: to help young people make informed and reasoned decisions for the public good as citizens of a culturally diverse democratic society in an interdependent world.

Since standards have been developed both in social studies and in many of the individual disciplines that are integral to social studies, one might ask: What is the relationship among these various sets of standards? The answer is that the social studies standards address overall curriculum design and comprehensive student learning expectations, while state standards and the national content standards for individual disciplines (e.g., history, civics and government, geography, economics, and psychology)4 provide a range of specific content through which student learning expectations can be accomplished. For example, the use of the NCSS standards might support a plan to teach about the topic of the U.S. Civil War by drawing on three different themes: Theme 2 TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE ; Theme 3 PEOPLE, PLACES, AND ENVIRONMENTS ; and Theme 10 CIVIC IDEALS AND PRACTICES . National history standards and state standards could be used to identify specific content related to the topic of the U.S. Civil War.

- The definition was officially adopted by National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) in 1992. See National Council for the Social Studies, Expectations of Excellence: Curriculum Standards for Social Studies (Washington, D.C.: NCSS, 1994): 3.

- For national history standards, see National Center for History in the Schools (NCHS), National Standards for History: Basic Edition (Los Angeles: National Center for History in the Schools, 1996); information is available at the NCHS website at nchs.ucla.edu/standards/ . For national geography standards, see Geography Education Standards Project, Geography for Life: National Geography Standards (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Research and Exploration, 1994); information is available at www.aag.org/cs/education/geography_for_life_national_geography_standards_second_edition . For national standards in civics and government, see Center for Civic Education, National Standards for Civics and Government (Calabasas, CA: Center for Civic Education, 1994); information is available at www.civiced.org/standards . For national standards in economics, see Council for Economic Education (formerly National Council on Economic Education), Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics (New York: National Council on Economic Education, 1997); information is available at www.councilforeconed.org/ea/program.php?pid=19 . For psychology, high school psychology content standards are included in the American Psychological Association’s national standards for high school psychology curricula. See American Psychological Association, National Standards for High School Psychology Curricula (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2005); information is available at www.apa.org/education/k12/national-standards.aspx .

- National Educational Technology Standards have been published by the International Society for Technology in Education, Washington, D.C. These standards and regular updates can be accessed at www.iste.org .

- See note 2 above.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

PROBLEM-BASED LEARNING IN SOCIAL STUDIES

This chapter excerpt describes the salient elements of problem-solving and problem-based learning. Video mini-lectures are included at the end.

Related Papers

heny andini

Andrew Johnson

This chapter excerpt defines social studies as a study of humans interacting. It also describes what is involved in social studies teaching and learning.

Teacher-centered instruction and learner-centered instruction provide two distinctly different ways of thinking about the teaching and learning experience. Teacher-centered instruction focuses on the teacher and the teacher’s performance. learner-centered instruction puts more emphasis and responsibility on the learner and the learning process.

For teacher professional development, you do not have to rely on experts to tell you what does and does not work or to explain to you what research says about something. Action research enables you to become your own expert. This article describes how action research can be used to develop each of the four types of knowledge necessary for teacher expertise: pedagogical knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, content knowledge, and knowledge of learners and learning.

Veronica Barba

Carol Johnston

In this paper we report the findings of an evaluation of the influence of collaborative problem-solving (CPS hereafter) on student attitudes and learning in economics tutorials.

Simon Williams

Lauren E Rudd

Solving problems is a necessary life skill and design is a problem solving process. This study investigated whether learning to design affected college students’ awareness and perception of their problem solving ability, and whether that ability correlated to academic success. Pretest-posttest scores of The Problem Solving Inventory were compared from a design fundamentals class. Results showed significant improvement in self-appraisal of problem solving ability subsequent to learning design. Student awareness of problem solving skills development was identified through student opinions involving solving problems for design and real life. Students indicated broader thinking, simplified solution development, and improved confidence. The study clearly shows correlations between learning to design and problem solving skills, and between problem solving skills and real-life problem solving.

iyon triyono

Environmental developments in the 21st century in various fields is more accelerated than the previous times, which raise many challenges, risks and uncertainties. In order to compete and survive in an increasing complex world, creativity and innovation skills are needed. Developing students’ creativity and innovation can be done through science learning. Problem solving in science learning can train students creativity and innovation skills. One of science learning model is creative problem solving. Creative problem solving emphasizes on creativity in solving problems that train and facilitate students how to be creative and innovative. Integrating creativity has a positive effect in learning, supports and enhances longlife learning. In this case, scientific literacy is required to support the reasoning and decision making as a creative and innovative solutions to the challenges and problems that exist. In this paper, first the concept of creativity and innovation is introduced, then creativity and innovation in education, creative problem solving (CPS) model, learning to creativity and innovation in CPS, and science learning are discussed. Key words: creativity and innovation, science learning, creative problem solving, scientific literacy

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Food Protection

Latiful Bari

Proceedings of the 3rd Beehive International Social Innovation Conference, BISIC 2020, 3-4 October 2020, Bengkulu, Indonesia

Anggri Puspita Sari

Powder Diffraction

James Kaduk

2015 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision

Daniel Prusa

Biomedical Physics & Engineering Express

David Sanchez-Molina

Iranian Journal of Applied Ecology

JPP (Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pembelajaran)

Eddy Sutadji

Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research MJTHR

Samah Mahmoud

Americas Conference on Information Systems

Frada Burstein

Muriel Vasconcellos

Visión Gerencial

Anderzon Medina Roa

Sandra D Anderson

Ady Purnama

Gerd Bjørhovde

Glasnik ?umarskog fakulteta

Danijela Đunisijević-Bojović

Lecture Notes in Computer Science

Mamoun Filali

European Psychiatry

Suljo Kunic

European Respiratory Review

Javier Milara

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

Timothy Beach

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Social Problem Solving

- Reference work entry

- pp 1399–1403

- Cite this reference work entry

- Molly Adrian 3 ,

- Aaron Lyon 4 ,

- Rosalind Oti 5 &

- Jennifer Tininenko 6

807 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Interpersonal cognitive problem solving ; Interpersonal problem solving ; Social decision making ; Social information processing

Social problem solving is the process by which individuals identify and enact solutions to social life situations in an effort to alter the problematic nature of the situation, their relation to the situation, or both [ 7 ].

Description

In D’Zurilla and Goldfried’s [ 6 ] seminal article, the authors conceptualized social problem solving as an individuals’ processing and action upon entering interpersonal situations in which no immediately effective response is available. One primary component of social problem solving is the cognitive-behavioral process of generating potential solutions to the social dilemma. The steps in this process were posited to be similar across individuals despite the wide variability of observed behaviors. The revised model [ 7 ] is comprised of two interrelated domains: problem orientation and problem solving style....

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol 1: Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Google Scholar

Chen, X., & French, D. C. (2008). Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 591–616.

PubMed Google Scholar

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115 , 74–101.

Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1987). Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53 , 1146–1158.

Downey, G., & Coyne, J. C. (1990). Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108 , 50–76.

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Goldfried, M. R. (1971). Problem solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 78 , 107–126.

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (1999). Problem solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Lochman, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). Social-cognitive processes of severely violent, moderately aggressive, and nonaggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62 , 366–374.

Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Brown, M. M. (1988). Early family experience, social problem solving patterns, and children’s social competence. Child Development, 59 , 107–120.

Quiggle, N. L., Garber, J., Panak, W. F., & Dodge, K. A. (1992). Social information processing in aggressive and depressed children. Child Development, 63 , 1305–1320.

Rubin, K. H., & Krasnor, L. R. (1986). Social-cognitive and social behavioral perspectives on problem solving. In M. Perlmutter (Ed.), Cognitive perspectives on children’s social and behavioral development. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 1–68). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rubin, K. H., & Rose-Krasnor, L. (1992). Interpersonal problem-solving and social competence in children. In V. B. van Hasselt & M. Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of social development: A lifespace perspective . New York: Plenum.

Shure, M. B., & Spivack, G. (1980). Interpersonal problem solving as a mediator of behavioral adjustment in preschool and kindergarten children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 1 , 29–43.

Spivack, G., & Shure, M. B. (1974). Social adjustment of young children . San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Box 354920, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA

Molly Adrian

Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Health, Seattle Children's Hospital, 4800 Gand Point way NE, Seattle, WA, 98125, USA

Rosalind Oti

Evidence Based Treatment Center of Seattle, 1200 5th Avenue, Suite 800, Seattle, WA, 98101, USA

Jennifer Tininenko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Neurology, Learning and Behavior Center, 230 South 500 East, Suite 100, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84102, USA

Sam Goldstein Ph.D.

Department of Psychology MS 2C6, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, 22030, USA

Jack A. Naglieri Ph.D. ( Professor of Psychology ) ( Professor of Psychology )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Adrian, M., Lyon, A., Oti, R., Tininenko, J. (2011). Social Problem Solving. In: Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_2703

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_2703

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-77579-1

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-79061-9

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Social Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

- Identifying and Structuring Problems

- Investigating Ideas and Solutions

- Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Social problem-solving might also be called ‘ problem-solving in real life ’. In other words, it is a rather academic way of describing the systems and processes that we use to solve the problems that we encounter in our everyday lives.

The word ‘ social ’ does not mean that it only applies to problems that we solve with other people, or, indeed, those that we feel are caused by others. The word is simply used to indicate the ‘ real life ’ nature of the problems, and the way that we approach them.

Social problem-solving is generally considered to apply to four different types of problems:

- Impersonal problems, for example, shortage of money;

- Personal problems, for example, emotional or health problems;

- Interpersonal problems, such as disagreements with other people; and

- Community and wider societal problems, such as litter or crime rate.

A Model of Social Problem-Solving

One of the main models used in academic studies of social problem-solving was put forward by a group led by Thomas D’Zurilla.

This model includes three basic concepts or elements:

Problem-solving

This is defined as the process used by an individual, pair or group to find an effective solution for a particular problem. It is a self-directed process, meaning simply that the individual or group does not have anyone telling them what to do. Parts of this process include generating lots of possible solutions and selecting the best from among them.

A problem is defined as any situation or task that needs some kind of a response if it is to be managed effectively, but to which no obvious response is available. The demands may be external, from the environment, or internal.

A solution is a response or coping mechanism which is specific to the problem or situation. It is the outcome of the problem-solving process.

Once a solution has been identified, it must then be implemented. D’Zurilla’s model distinguishes between problem-solving (the process that identifies a solution) and solution implementation (the process of putting that solution into practice), and notes that the skills required for the two are not necessarily the same. It also distinguishes between two parts of the problem-solving process: problem orientation and actual problem-solving.

Problem Orientation

Problem orientation is the way that people approach problems, and how they set them into the context of their existing knowledge and ways of looking at the world.

Each of us will see problems in a different way, depending on our experience and skills, and this orientation is key to working out which skills we will need to use to solve the problem.

An Example of Orientation

Most people, on seeing a spout of water coming from a loose joint between a tap and a pipe, will probably reach first for a cloth to put round the joint to catch the water, and then a phone, employing their research skills to find a plumber.

A plumber, however, or someone with some experience of plumbing, is more likely to reach for tools to mend the joint and fix the leak. It’s all a question of orientation.

Problem-Solving

Problem-solving includes four key skills:

- Defining the problem,

- Coming up with alternative solutions,

- Making a decision about which solution to use, and

- Implementing that solution.

Based on this split between orientation and problem-solving, D’Zurilla and colleagues defined two scales to measure both abilities.

They defined two orientation dimensions, positive and negative, and three problem-solving styles, rational, impulsive/careless and avoidance.

They noted that people who were good at orientation were not necessarily good at problem-solving and vice versa, although the two might also go together.

It will probably be obvious from these descriptions that the researchers viewed positive orientation and rational problem-solving as functional behaviours, and defined all the others as dysfunctional, leading to psychological distress.

The skills required for positive problem orientation are:

Being able to see problems as ‘challenges’, or opportunities to gain something, rather than insurmountable difficulties at which it is only possible to fail.

For more about this, see our page on The Importance of Mindset ;

Believing that problems are solvable. While this, too, may be considered an aspect of mindset, it is also important to use techniques of Positive Thinking ;

Believing that you personally are able to solve problems successfully, which is at least in part an aspect of self-confidence.

See our page on Building Confidence for more;

Understanding that solving problems successfully will take time and effort, which may require a certain amount of resilience ; and

Motivating yourself to solve problems immediately, rather than putting them off.

See our pages on Self-Motivation and Time Management for more.

Those who find it harder to develop positive problem orientation tend to view problems as insurmountable obstacles, or a threat to their well-being, doubt their own abilities to solve problems, and become frustrated or upset when they encounter problems.

The skills required for rational problem-solving include:

The ability to gather information and facts, through research. There is more about this on our page on defining and identifying problems ;

The ability to set suitable problem-solving goals. You may find our page on personal goal-setting helpful;

The application of rational thinking to generate possible solutions. You may find some of the ideas on our Creative Thinking page helpful, as well as those on investigating ideas and solutions ;

Good decision-making skills to decide which solution is best. See our page on Decision-Making for more; and

Implementation skills, which include the ability to plan, organise and do. You may find our pages on Action Planning , Project Management and Solution Implementation helpful.

There is more about the rational problem-solving process on our page on Problem-Solving .

Potential Difficulties

Those who struggle to manage rational problem-solving tend to either:

- Rush things without thinking them through properly (the impulsive/careless approach), or

- Avoid them through procrastination, ignoring the problem, or trying to persuade someone else to solve the problem (the avoidance mode).

This ‘ avoidance ’ is not the same as actively and appropriately delegating to someone with the necessary skills (see our page on Delegation Skills for more).

Instead, it is simple ‘buck-passing’, usually characterised by a lack of selection of anyone with the appropriate skills, and/or an attempt to avoid responsibility for the problem.

An Academic Term for a Human Process?

You may be thinking that social problem-solving, and the model described here, sounds like an academic attempt to define very normal human processes. This is probably not an unreasonable summary.

However, breaking a complex process down in this way not only helps academics to study it, but also helps us to develop our skills in a more targeted way. By considering each element of the process separately, we can focus on those that we find most difficult: maximum ‘bang for your buck’, as it were.

Continue to: Decision Making Creative Problem-Solving

See also: What is Empathy? Social Skills

- Legislative Tracker on Education

- X (Twitter)

Problem-Solving: Our Social Studies Standards Call for Deep Engagement

We want Kentucky students to be increasingly able to “Think and solve problems in school situations and in a variety of situations they will encounter in life.” Yesterday’s post looked at how our science standards call for deep work to meet that expectation from our 1990 Kentucky Education Reform Act. Now, let’s turn to social studies, where our standards value problem-solving that includes attention to diverse perspectives and sustained work to develop shared and democratic decisions.

Examples of our social studies standards

Problem-solving matters across all grades in social studies. To give just a small taste:

- Kindergartners should be able to “Construct an argument to address a problem in the classroom or school.

- Third-graders should be able to “construct an explanation, using relevant information, to address a local, regional or global problem”

- Seventh grade students should be able to “analyze a specific problem from the growth and expansion of civilizations using each of the social studies disciplines”

Diverse perspectives get special attention in understanding social studies problems. As they work, students are also expected to discover that people all around them (and in all periods of the past) can see issues quite differently, and the standards expect students to grow steadily more skilled in understanding those varied views, Kentucky is working to equip:

- First graders to “identify information from two or more sources to describe multiple perspectives about communities in Kentucky”

- Fifth graders to “analyze primary and secondary sources on the same event or topic, noting key similarities and differences in the perspective they represent”

- Seventh graders to “Analyze evidence from multiple perspectives and sources to support claims and refute opposing claims, noting evidentiary limitations to answer compelling and supporting questions”

Shared decisions on solutions required intensive work in social studies, where the overall goal is to equip young citizens. Thus, our standards call for:

- Second graders who can “use listening and consensus-building procedures to discuss how to take action in the local community or Kentucky”

- Fourth graders who can “Use listening and consensus-building to determine ways to support people in transitioning to a new community.”

- Eight graders who can “Apply a range of deliberative and democratic procedures to make decisions about ways to take action on current local, regional and global issues”

All three elements –problem solving, understanding perspectives, and building shared decisions—come together at the high school level. There students are asked to “engage in disciplinary thinking and apply appropriate evidence to propose a solution or design an action plan relevant to compelling and/or compelling questions in civics” and do matching work on solutions and action plans in economics, geography, U.S. history and world history.

Working within a cycle of inquiry

Those examples and others like them reflect an “inquiry cycle” built into our social studies approach. As you can see from the graphic illustration below (taken from the standards document itself, Kentucky expects students to deepen their skills each year through work on:

- Questioning , which includes both developing major compelling questions that are “open-ended, enduring and centered on significant unresolved issues,” and smaller supporting questions for exploration on the way to answering the compelling ones.

- Investigating using the content, concepts and tools of civics, geography, economics, and history to gain insight into the questions they study

- Using evidence from their investigations to build sound explanations and arguments to support their claims

- Communicating conclusions to a variety of audiences, making their explanations and arguments available in traditional forms like essays, reports, diagrams and discussions and also in newer media forms. The introduction to the social studies standards advises that: “ A student’s ability to effectively communicate their own conclusions and listen carefully to the conclusions of others can be considered a capstone of social studies disciplinary practices.”

Do notice that the second part of the cycle –the disciplinary investigation phase– includes robust detail on working with specific content knowledge each year. These are standards for focused inquiry, organized in thoughtful sequences that connect disciplines and build understanding grade by grade. The problem-solving skills are integrated into that framework of needed knowledge and understanding.

You can get a fuller sense of how these elements work together in each grade from the full standards document , which is definitely worth your close attention.

Problem-solvers now and years from now

Students who take on this kind of problem solving will be participating citizens right here, right now. To learn these capacities, they’ll have to explore varied experiences and understandings, listen to one another, and collaborate to complete big projects and assignments. Done well, those will be challenging, satisfying, memorable parts of each learner’s school years.

Students who solve problems in this inquiry-driven way will also be building skills that can last a lifetime. Imagine communities where many residents are good at this kind of exploring, listening, collaborating, and working toward shared decisions. They’ll be better at tackling local issues than we are today. They’ll be ready to take on bigger problems together and find bolder solutions, with rich results for each of them and all of us.

A note on organization : the science standards and the social studies standards took on a similar design challenge, trying to combine (a) high expectations for students engaging in key practices of scientists, historians, and other practitioners and (b) a lean statement of very important disciplinary content. In the science version, each performance expectation marries a specific practice with a scientific topic. In social studies, there are distinct (though tightly connected) standards for the major inquiry practices and for the investigations into content in each discipline. My take is that the social studies approach has a major benefit in inviting teachers to develop varied ways to apply practices to topics. The science approach could mean that teachers will only feel free to work on the specific practice/content combinations listed as our performance expectations. I support both, but I do think the social studies version invites richer learning opportunities.

Susan Perkins Weston analyzes Kentucky data and policy, and she’s always on the lookout for ways to enrich the instructional core where students and teachers work together on learning content. Susan is an independent consultant who has been taking on Prichard Committee assignments since 1991. She is a Prichard Committee Senior Fellow.

Problem-Solving: Kentucky’s Science Standards Go Deep

Problem-Solving across Many Disciplines

Related posts, national board certification keeps teachers student-centered, focused and effective, we must close the digital divide in kentucky., failing to deliver: kentucky lacks in providing black students with advanced learning opportunities.

Comments are closed.

- Board of Directors

- Join Our Team

- Mission, Vision, & Values

- Annual Reports

- Equity Coalition

- Strong Start Kentucky

- Legislative Action Toolkit

- Big Bold Future

- Early Childhood

- K-12 Education

- Postsecondary

- Quality of Life

- Family Friendly Schools

- Groundswell

- Kentucky Community Schools

- Commonwealth Institute for Parent Leadership

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- 972-854-1266

- [email protected]

Creative Problem Solving Today

Each mind missions lesson includes a problem-based learning (pbl) challenge. students work in teams to devise a solution to historical and geographical steam problems..

Mind Missions is an elementary social studies curriculum. Each lesson contains a mission challenge based on a real-world geographical or historical problem. Students may be challenged to create a code for World War II. The mission challenge might be to build a moving monument to a person or a critical event. Students may be asked to create an advertising campaign to address a social or environmental problem. Student teams engage in problem based learning (PBL) lessons.

After they receive the essential problem, student teams brainstorm potential solutions. They discuss the merits and problems associated with each potential solution. Then students collaboratively and creatively generate a unique solution to the STEAM problem. Solutions draw on science, technology, engineering, art, and math for success. Throughout the process, students use design thinking to generate ideas, imagine solutions, innovate, create, test, and re-engineer for successful implementation. They evaluate their work for successful design, outcome, and ingenuity. When mission innovations fail, students re-design and grow as designers and team members.

Finally, teams present their solution to the class and test their mission success. After presentations, solutions are evaluated for effectiveness and creativity. Both are celebrated and recognized as essential elements of effective problem-based learning.

Students learn how to innovate, create, and evaluate using Mind Missions elementary social studies curriculum. While they build problem-solving skills, students are learning state standards for Language Arts and Social Studies.

Download these sample Mind Mission lessons to try in the classroom:

“History has demonstrated that the most notable winners usually encountered heartbreaking obstacles before they triumphed. They won because they refused to become discouraged by their defeats.” B.C. Forbes

No teacher should have to choose between lessons that are fun, immersive, and effective or lessons that are standards-aligned. Mind Missions exists so you don’t have to.

- 214-299-8665

The Company

- Mind Missions Blog

- Standards Alignment

- Professional Development

Customer Service

- Return Policy

©2024 Elementary Mind Missions, LLC | All rights reserved

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 22 May 2024

Can mathematicians help to solve social-justice problems?

- Rachel Crowell 0

Rachel Crowell is a freelance journalist near Des Moines, Iowa.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Detroit community members have raised concerns about gunshot-tracking technology, ShotSpotter. Mathematics are being used to study the effectiveness of such policing. Credit: Malachi Barrett

When Carrie Diaz Eaton trained as a mathematician, they didn’t expect their career to involve social-justice research. Growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, Diaz Eaton first saw social justice in action when their father, who’s from Peru, helped other Spanish-speaking immigrants to settle in the United States.

But it would be decades before Diaz Eaton would forge a professional path to use their mathematical expertise to study social-justice issues. Eventually, after years of moving around for education and training, that journey brought them back to Providence, where they collaborated with the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council on projects focused on preserving the local environment of the river’s drainage basin, and bolstering resources for the surrounding, often underserved communities.

By “thinking like a mathematician” and leaning on data analysis, data science and visualization skills, they found that their expertise was needed in surprising ways, says Diaz Eaton, who is now executive director of the Institute for a Racially Just, Inclusive, and Open STEM Education at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine.

For example, the council identified a need to help local people to better connect with community resources. “Even though health care and education don’t seem to fall under the purview of a watershed council, these are all interrelated issues,” Diaz Eaton says. Air pollution can contribute to asthma attacks, for example. In one project, Diaz Eaton and their collaborators built a quiz to help community members to choose the right health-care option, depending on the nature of their illness or injury, immigration status and health-insurance coverage.

“One of the things that makes us mathematicians, is our skills in logic and the questioning of assumptions”, and creating that quiz “was an example of logic at play”, requiring a logic map of cases and all of the possible branches of decision-making to make an effective quiz, they say.

Maths might seem an unlikely bedfellow for social-justice research. But applying the rigour of the field is turning out to be a promising approach for identifying, and sometimes even implementing, fruitful solutions for social problems.

Mathematicians can experience first-hand the messiness and complexity — and satisfaction — of applying maths to problems that affect people and their communities. Trying to work out how to help people access much-needed resources, reduce violence in communities or boost gender equity requires different technical skills, ways of thinking and professional collaborations compared with breaking new ground in pure maths. Even for an applied mathematician like Diaz Eaton, transitioning to working on social-justice applications brings fresh challenges.

Mathematicians say that social-justice research is difficult yet fulfilling — these projects are worth taking on because of their tremendous potential for creating real-world solutions for people and the planet.

Data-driven research

Mathematicians are digging into issues that range from social inequality and health-care access to racial profiling and predictive policing. However, the scope of their research is limited by their access to the data, says Omayra Ortega, an applied mathematician and mathematical epidemiologist at Sonoma State University in Rohnert Park, California. “There has to be that measured information,” Ortega says.

Lily Khadjavi used a pivotal set of traffic-stop data from the Los Angeles Police Department in her statistics class at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, California. Credit: Loyola Marymount University

Fortunately, data for social issues abound. “Our society is collecting data at a ridiculous pace,” Ortega notes. Her mathematical epidemiology work has examined which factors affect vaccine uptake in different communities. Her work 1 has found, for example, that, in five years, a national rotavirus-vaccine programme in Egypt would reduce disease burden enough that the cost saving would offset 76% of the costs of the vaccine. “Whenever we’re talking about the distribution of resources, there’s that question of social justice: who gets the resources?” she says.

Lily Khadjavi’s journey with social-justice research began with an intriguing data set.

About 15 years ago, Khadjavi, a mathematician at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, California, was “on the hunt for real-world data” for an undergraduate statistics class she was teaching. She wanted data that the students could crunch to “look at new information and pose their own questions”. She realized that Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) traffic-stop data fit that description.

At that time, every time that LAPD officers stopped pedestrians or pulled over drivers, they were required to report stop data. Those data included “the perceived race or ethnicity of the person they had stopped”, Khadjavi notes.

When the students analysed the data, the results were memorable. “That was the first time I heard students do a computation absolutely correctly and then audibly gasp at their results,” she says. The data showed that one in every 5 or 6 police stops of Black male drivers resulted in a vehicle search — a rate that was more than triple the national average, which was about one out of every 20 stops for drivers of any race or ethnicity, says Khadjavi.

Her decision to incorporate that policing data into her class was a pivotal moment in Khadjavi’s career — it led to a key publication 2 and years of building expertise in using maths to study racial profiling and police practice. She sits on California’s Racial Identity and Profiling Advisory Board , which makes policy recommendations to state and local agencies on how to eliminate racial profiling in law enforcement.

In 2023, she was awarded the Association for Women in Mathematics’ inaugural Mary & Alfie Gray Award for Social Justice, named after a mathematician couple who championed human rights and equity in maths and government.

Sometimes, gaining access to data is a matter of networking. One of Khadjavi’s colleagues shared Khadjavi’s pivotal article with specialists at the American Civil Liberties Union. In turn, these specialists shared key data obtained through public-records requests with Khadjavi and her colleague. “Getting access to that data really changed what we could analyse,” Khadjavi says. “[It] allowed us to shine a light on the experiences of civilians and police in hundreds of thousands of stops made every year in Los Angeles.”

The data-intensive nature of this research can be an adjustment for some mathematicians, requiring them to develop new skills and approach problems differently. Such was the case for Tian An Wong, a mathematician at the University of Michigan-Dearborn who trained in number theory and representation theory.

In 2020, Wong wanted to know more about the controversial issue of mathematicians collaborating with the police, which involves, in many cases, using mathematical modelling and data analysis to support policing activities. Some mathematicians were protesting about the practice as part of a larger wave of protests around systemic racism , following the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Wong’s research led them to a technique called predictive policing, which Wong describes as “the use of historical crime and other data to predict where future crime will occur, and [to] allocate policing resources based on those predictions”.

Wong wanted to know whether the tactics that mathematicians use to support police work could instead be used to critique it. But first, they needed to gain some additional statistics and data analysis skills. To do so, Wong took an online introductory statistics course, re-familiarized themself with the Python programming language, and connected with colleagues trained in statistical methods. They also got used to reading research papers across several disciplines.

Currently, Wong applies those skills to investigating the policing effectiveness of a technology that automatically locates gunshots by sound. That technology has been deployed in parts of Detroit, Michigan, where community members and organizations have raised concerns about its multimillion-dollar cost and about whether such police surveillance makes a difference to public safety.

Getting the lay of the land

For some mathematicians, social-justice work is a natural extension of their career trajectories. “My choice of mathematical epidemiology was also partially born out of out of my love for social justice,” Ortega says. Mathematical epidemiologists apply maths to study disease occurrence in specific populations and how to mitigate disease spread. When Ortega’s PhD adviser mentioned that she could study the uptake of a then-new rotovirus vaccine in the mid-2000s, she was hooked.

Applied mathematician Michael Small has turned his research towards understanding suicide risk in young people. Credit: Michael Small

Mathematicians, who decide to jump into studying social-justice issues anew, must do their homework and dedicate time to consider how best to collaborate with colleagues of diverse backgrounds.

Jonathan Dawes, an applied mathematician at the University of Bath, UK, investigates links between the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their associated target actions. Adopted in 2015, the SDGs are “a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity,” according to the United Nations , and each one has a number of targets.

“As a global agenda, it’s an invitation to everybody to get involved,” says Dawes. From a mathematical perspective, analysing connections in the complex system of SDGs “is a nice level of problem,” Dawes says. “You’ve got 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Between them, they have 169 targets. [That’s] an amount of data that isn’t very large in big-data terms, but just big enough that it’s quite hard to hold all of it in your head.”

Dawes’ interest in the SDGs was piqued when he read a 2015 review that focused on how making progress on individual goals could affect progress on the entire set. For instance, if progress is made on the goal to end poverty how does that affect progress on the goal to achieve quality education for all, as well as the other 15 SDGs?

“If there’s a network and you can put some numbers on the strengths and signs of the edges, then you’ve got a mathematized version of the problem,” Dawes says. Some of his results describe how the properties of the network change if one or more of the links is perturbed, much like an ecological food web. His work aims to identify hierarchies in the SDG networks, pinpointing which SDGs should be prioritized for the health of the entire system.

As Dawes dug into the SDGs, he realized that he needed to expand what he was reading to include different journals, including publications that were “written in very different ways”. That involved “trying to learn a new language”, he explains. He also kept up to date with the output of researchers and organizations doing important SDG-related work, such as the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Laxenburg, Austria, and the Stockholm Environment Institute.

Dawes’ research 3 showed that interactions between the SDGs mean that “there are lots of positive reinforcing effects between poverty, hunger, health care, education, gender equity and so on.” So, “it’s possible to lift all of those up” when progress is made on even one of the goals. With one exception: managing and protecting the oceans. Making progress on some of the other SDGs could, in some cases, stall progress for, or even harm, life below water.

Collaboration care

Because social-justice projects are often inherently cross-disciplinary, mathematicians studying social justice say it’s key in those cases to work with community leaders, activists or community members affected by the issues.

Getting acquainted with these stakeholders might not always feel comfortable or natural. For instance, when Dawes started his SDG research, he realized that he was entering a field in which researchers already knew each other, followed each other’s work and had decades of experience. “There’s a sense of being like an uninvited guest at a party,” Dawes says. He became more comfortable after talking with other researchers, who showed a genuine interest in what he brought to the discussion, and when his work was accepted by the field’s journals. Over time, he realized “the interdisciplinary space was big enough for all of us to contribute to”.

Even when mathematicians have been invited to join a team of social-justice researchers, they still must take care, because first impressions can set the tone.

Michael Small is an applied mathematician and director of the Data Institute at the University of Western Australia in Perth. For much of his career, Small focused on the behaviour of complex systems, or those with many simple interacting parts, and dynamical systems theory, which addresses physical and mechanical problems.

But when a former vice-chancellor at the university asked him whether he would meet with a group of psychiatrists and psychologists to discuss their research on mental health and suicide in young people, it transformed his research. After considering the potential social impact of better understanding the causes and risks of suicide in teenagers and younger children, and thinking about how the problem meshed well with his research in complex systems and ‘non-linear dynamics’, Small agreed to collaborate with the group.

The project has required Small to see beyond the numbers. For the children’s families, the young people are much more than a single data point. “If I go into the room [of mental-health professionals] just talking about mathematics, mathematics, mathematics, and how this is good because we can prove this really cool theorem, then I’m sure I will get push back,” he says. Instead, he notes, it’s important to be open to insights and potential solutions from other fields. Listening before talking can go a long way.

Small’s collaborative mindset has led him to other mental-health projects, such as the Transforming Indigenous Mental Health and Wellbeing project to establish culturally sensitive mental-health support for Indigenous Australians.

Career considerations

Mathematicians who engage in social-justice projects say that helping to create real-world change can be tremendously gratifying. Small wants “to work on problems that I think can do good” in the world. Spending time pursuing them “makes sense both as a technical challenge [and] as a social choice”, he says.

However, pursuing this line of maths research is not without career hurdles. “It can be very difficult to get [these kinds of] results published,” Small says. Although his university supports, and encourages, his mental-health research, most of his publications are related to his standard mathematics research. As such, he sees “a need for balance” between the two lines of research, because a paucity of publications can be a career deal breaker.

Diaz Eaton says that mathematicians pursuing social-justice research could experience varying degrees of support from their universities. “I’ve seen places where the work is supported, but it doesn’t count for tenure [or] it won’t help you on the job market,” they say.

Finding out whether social-justice research will be supported “is about having some really open and transparent conversations. Are the people who are going to write your recommendation letters going to see that work as scholarship?” Diaz Eaton notes.

All things considered, mathematicians should not feel daunted by wading into solving the world’s messy problems, Khadjavi says: “I would like people to follow their passions. It’s okay to start small.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01494-7

Connolly, M. P. et al. PharmacoEconomics 30 , 681–695 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Khadjavi, L. S. Chance 19 , 43–46 (2006).

Article Google Scholar

Dawes, J. H. P. World Dev. 149 , 105693 (2022)

Download references

Related Articles

- Mathematics and computing

- Scientific community

Who owns your voice? Scarlett Johansson OpenAI complaint raises questions

News Explainer 29 MAY 24

Low-latency automotive vision with event cameras

Article 29 MAY 24

Anglo-American bias could make generative AI an invisible intellectual cage

Correspondence 28 MAY 24

Defying the stereotype of Black resilience

Career Q&A 30 MAY 24

Nature’s message to South Africa’s next government: talk to your researchers

Editorial 29 MAY 24

How I run a virtual lab group that’s collaborative, inclusive and productive

Career Column 31 MAY 24

Japan’s push to make all research open access is taking shape

News 30 MAY 24

How I overcame my stage fright in the lab

Career Column 30 MAY 24

Global Talent Recruitment (Scientist Positions)

Global Talent Gathering for Innovation, Changping Laboratory Recruiting Overseas High-Level Talents.

Beijing, China

Changping Laboratory

Postdoctoral Associate - Amyloid Strain Differences in Alzheimer's Disease

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoctoral Associate- Bioinformatics of Alzheimer's disease

Postdoctoral associate- alzheimer's gene therapy, postdoctoral associate.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Innovative Educator: Galileo teacher reboots lessons with twist of technology

Editor's note: This content is sponsored by CapEd Credit Union .

Problem solving using technology – this week's Innovative Educator is using students' love for tech to learn every subject.

"Lots of tears on the last day of school, it's a safe place," said Gina Kwid, a second grade teacher at Galileo STEM Academy in Eagle.

While school may be out for students at Galileo, Kwid's students will hold onto the lessons they learned this year in her classroom.

"They love it … We are learning literally every second that we are in the classroom," Kwid said. "They're taking that, just that growth mindset."

The growth mindset includes problem solving, with encouragement and perspective from Mrs. Kwid.

"Even if it doesn't work the first time, you know, I can go back and iterate it's not a failure," Kwid said. "We just found one way that doesn't work."

With subjects that involve almost anything – sometimes it is out of this world.

"We tie in a lot of NASA lessons and we bring in space with science, with math, with social studies," Kwid said.

The second grade class also brings in a twist of technology. Kwid said "I love to integrate technology and educational technology into every subject," and she means literally every subject.

"The kids are coding robots to write stories. They are creating videos for assessments of stories that we've read," Kwid said. "The kids are doing mathematics with robots, social studies in science. We integrate a lot of space science and history through the use of educational technology tools."

As for the students at Galileo STEM Academy, Kwid said "they love it."

"It's just controlled chaos in here all the time," Kwid said.

The Innovative Educator said using robots for just about anything is a concept the students are pretty much used to.

"They truly are coding and technology natives," Kwid said. "You know, they've never known a world without it and they have no fear."

It is a common trend Kwid's seen in her 20 years of teaching.

"When they come back and they graduate college, and they're making more than me after doing this over 20 years, I go, 'yes! You know, that's the goal, you did it.'"

As students move on from her second grade classroom, Kwid hopes to continue inspiring future generations.

Educators, for information on submitting an application for a classroom grant through the Idaho CapEd Foundation, visit www.capedfoundation.org . If you would like to nominate an Innovative Educator, send us an email to [email protected] .

Watch more ' Innovative Educators ':

See every episode in our YouTube playlist :

HERE ARE MORE WAYS TO GET NEWS FROM KTVB:

Download the KTVB News Mobile App

Apple iOS: Click here to download

Google Play: Click here to download

Watch news reports for FREE on YouTube: KTVB YouTube channel

Stream Live for FREE on ROKU: Add the channel from the ROKU store or by searching 'KTVB'.

Stream Live for FREE on FIRE TV: Search ‘KTVB’ and click ‘Get’ to download.

FOLLOW US ON TWITTER , FACEBOOK & INSTAGRAM

Scientists may have finally solved the problem of the universe’s 'missing' black holes

Primordial black holes are one of the strongest candidates for the universe's missing dark matter. But a new theory suggests that not enough of the miniature black holes formed for this to be the case.

The early universe contained far fewer miniature black holes than previously thought, making the origins of our cosmos's missing matter an even greater mystery, a new study has suggested.

Miniature, or primordial, black holes (PBHs) are black holes thought to have formed in the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang. According to leading theories, these dime-sized singularities popped into existence from rapidly collapsing regions of thick, hot gas.

The pockets of infinitely dense space-time are how many physicists explain the universe's dark matter, a mysterious entity that, despite being completely invisible, makes the universe much heavier than can be explained by the matter we see.

But even though the hypothesis is popular, it has one big problem: we've yet to directly observe any primordial black holes. Now, a new study has offered a possible explanation as to why they didn't form, throwing open cosmology's dark matter problem to wider speculation.

According to the research, the modern universe could have taken shape with far fewer primordial black holes than previous models estimated. The researchers published their findings May 29 in the journal Physical Review Letters .

Related: 1st detection of 'hiccupping' black hole leads to surprising discovery of 2nd black hole orbiting around it

"Many researchers feel they [primordial black holes] are a strong candidate for dark matter, but there would need to be plenty of them to satisfy that theory," lead author Jason Kristiano , a graduate student in theoretical physics at the University of Tokyo, said in a statement . "They are interesting for other reasons too, as since the recent innovation of gravitational wave astronomy, there have been discoveries of binary black hole mergers, which can be explained if PBHs exist in large numbers. But despite these strong reasons for their expected abundance, we have not seen any directly, and now we have a model which should explain why this is the case."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A hole in the picture

The universe began 13.8 billion years ago with the Big Bang , causing the young cosmos to explode outward due to an invisible force known as dark energy .

As the universe grew, ordinary matter, which interacts with light, congealed around clumps of invisible dark matter to create the first galaxies, connected together by a vast cosmic web. Nowadays, cosmologists think that ordinary matter, dark matter and dark energy make up about 5%, 25% and 70% of the universe’s composition, respectively.

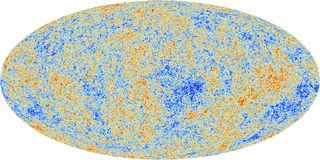

Initially, the universe was opaque, a plasma broth that no light could traverse without being snared by electromagnetic fields produced by moving charges. Yet after 380,000 years of cooling and expansion, the plasma eventually recombined into neutral matter, giving off microwave static that became the universe's first light, the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

Cosmologists have been searching for these early black holes by studying this first baby picture of the universe . Yet, so far, none have been found.

Some physicists think there's a possibility they haven't discovered the vast numbers of primordial black holes necessary to account for dark matter simply because they've yet to learn how to detect them.

But by applying a model built on an advanced form of quantum mechanics called quantum field theory to the problem, the researchers behind the new study arrived at a different conclusion — we can't find any primordial black holes because most of them simply aren't there.

— Scientists reveal largest map of the universe's active supermassive black holes ever created

— Universe's oldest X-ray-spitting quasar could reveal how the biggest black holes were born

— Mysterious 'ancient heart' of the Milky Way discovered using Gaia probe

Primordial black holes are believed to have emerged from the collapse of short but strong gravitational waves rippling across the universe. By applying their model to these waves, the researchers found that it could take much less of these waves to combine than other theories estimate in order to shape larger structures across the universe. And the fewer the waves necessary to recreate the picture, the fewer primordial black holes.

"It is widely believed that the collapse of short but strong wavelengths in the early universe is what creates primordial black holes," said Kristiano. "Our study suggests there should be far fewer PBHs than would be needed if they are indeed a strong candidate for dark matter or gravitational wave events."

To confirm their theory, the researchers will look to future, hyper-sensitive gravitational wave detectors such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) project , which is due to be sent into space on an Ariane 3 rocket in 2035.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

'Vanishing' stars may be turning into black holes without going supernova, new study hints

NASA spots 16 'Death Star' black holes blasting powerful beams at multiple targets

Sorry, Spock: 'Vulcan' planet spotted near famous star was just a mirage, NASA says

Most Popular

- 2 Alaska's rivers are turning bright orange and as acidic as vinegar as toxic metal escapes from melting permafrost

- 3 32 stunning photos of auroras seen from space

- 4 Things are finally looking up for the Voyager 1 interstellar spacecraft

- 5 Reaching absolute zero for quantum computing now much quicker thanks to breakthrough refrigerator design

- 2 Secrets of radioactive 'promethium' — a rare earth element with mysterious applications — uncovered after 80-year search

- 3 Auroras could paint Earth's skies again in early June. Here are the key nights to watch for.

- 4 32 optical illusions and why they trick your brain

- 5 Ramesses II's sarcophagus finally identified thanks to overlooked hieroglyphics

COMMENTS

Researchers found students were able to learn problem-solving skills through the series of structured computer analysis projects. "The purpose of social studies is to enhance student's ability to participate in a democratic society," said Meghan Manfra, associate professor of education at NC State.

The problem solving model, also referred to as discovery learning or inquiry, is a version of the scientific method and focuses on examining content. As applied to social studies instruction, the steps include the following: • Define or perceive the problem.

social studies scholars are exposed to both theory and research concerning critical-thinking. For the purpose of this study, a broad definition of critical-thinking is used, which encompasses all the cognitive processes and strategies, attitudes and dispositions, as well as decision-making, problem solving, inquiry, and higher-order

Framework, social studies prepares students for their post-secondary futures, including the disciplinary practices and literacies needed for college-level work in social studies aca-demic courses, and the critical thinking, problem solving, and collaborative skills needed for the workplace. This framework

Since social studies has as its primary goal the development of a democratic citizenry, the experiences students have in their social studies classrooms should enable learners to engage in civic discourse and problem-solving, and to take informed civic action.

Embedding problem solving into a social studies curriculum begins with teaching students the problem solving process. CPS and MEA should be taught to students using problems or situations with which they are familiar. You might ask students to use them to inventing new products or to solving problems for which they encounter in their lives.

This chapter focuses on effective preparation for civic reasoning, discourse, and problem solving. It reviews literatures, including major synthetic reviews and studies from the science of learning and development (SoLD), civics education, and mathematics education.

Development of Social Problem Solving Abilities. The attention to developmental factors highlighted by Spivack and Shure [], Crick and Dodge [] and Rubin and Krasnor [] represent significant steps toward understanding social problem solving processes in youth.The majority of research has emphasized the importance of social influences on the development of effective social problem solving skills.

become a common feature of programs designed to prevent and remediate discipline problems. (Bear, 1998). Social problem solving skills are skills that students "use to analyze, understand, and prepare to respond to everyday problems, decisions, and conflicts" (Elias & Clabby, 1988, p. 53). Learning these skills helps students to improve ...

Ideas regarding the way a social-science problem-solving skill is acquired and the way it is related to a more general problem-solving research are discussed in the chapter. Testing hypotheses in social sciences tends to be a much more protracted process. ... Studies 1 and 2 examine the differences between expert, beginning, and pre-service ...

One of the main models used in academic studies of social problem-solving was put forward by a group led by Thomas D'Zurilla. This model includes three basic concepts or elements: Problem-solving. This is defined as the process used by an individual, pair or group to find an effective solution for a particular problem. ...

What is Social Problem Solving? Social problem solving is the cognitive-behavioral process that an individual goes through to solve a social problem. Typically, there are five steps within this process: 1. Identifying that the problem exists: Recognizing there is a problem that needs to be solved. 2. Defining the problem: Naming and describing ...

Problem solving skills are mentioned among the skills which need to be acquired in the Social Studies course. In this study, how the social studies teachers perceived problem solving skills was ...

The approach known as Social Decision Making and Social Problem Solving (SDM/SPS) has been utilized since the late 1970s to promote the development of social-emotional skills in students, which is now also being applied in academic settings. This approach is rooted in the work of John Dewey (1933) and has been extensively studied and ...