What is kangaroo mother care? Systematic review of the literature

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Saving Newborn Lives, Save the Children, Washington, DC, USA.

- 2 Saving Newborn Lives, Save the Children, Washington, DC, USA.

- 3 Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

- PMID: 27231546

- PMCID: PMC4871067

- DOI: 10.7189/jogh.06.010701

Background: Kangaroo mother care (KMC), often defined as skin-to-skin contact between a mother and her newborn, frequent or exclusive breastfeeding, and early discharge from the hospital has been effective in reducing the risk of mortality among preterm and low birth weight infants. Research studies and program implementation of KMC have used various definitions.

Objectives: To describe the current definitions of KMC in various settings, analyze the presence or absence of KMC components in each definition, and present a core definition of KMC based on common components that are present in KMC literature.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review and searched PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and the World Health Organization Regional Databases for studies with key words "kangaroo mother care", "kangaroo care" or "skin to skin care" from 1 January 1960 to 24 April 2014. Two independent reviewers screened articles and abstracted data.

Findings: We screened 1035 articles and reports; 299 contained data on KMC and neonatal outcomes or qualitative information on KMC implementation. Eighty-eight of the studies (29%) did not define KMC. Two hundred and eleven studies (71%) included skin-to-skin contact (SSC) in their KMC definition, 49 (16%) included exclusive or nearly exclusive breastfeeding, 22 (7%) included early discharge criteria, and 36 (12%) included follow-up after discharge. One hundred and sixty-seven studies (56%) described the duration of SSC.

Conclusions: There exists significant heterogeneity in the definition of KMC. A large number of studies did not report definitions of KMC. Skin-to-skin contact is the core component of KMC, whereas components such as breastfeeding, early discharge, and follow-up care are context specific. To implement KMC effectively development of a global standardized definition of KMC is needed.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Attitude to Health

- Infant, Newborn

- Kangaroo-Mother Care Method / classification*

- Mothers / psychology*

- Physical Stimulation / methods*

- Open access

- Published: 18 November 2022

What influences the implementation of kangaroo mother care? An umbrella review

- Qian Cai 1 , 2 ,

- Dan-Qi Chen 1 , 2 ,

- Hua Wang 2 ,

- Yue Zhang 2 ,

- Rui Yang 1 , 2 ,

- Wen-Li Xu 3 &

- Xin-Fen Xu 2 , 3

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 22 , Article number: 851 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4081 Accesses

5 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is an evidence-based intervention that reduces morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. However, it has not yet been fully integrated into health systems around the world. The aim of this study is to provide a cogent summary of the evidence base of the key barriers and facilitators to implementing KMC.

An umbrella review of existing reviews on KMC was adopted to identify systematic and scoping reviews that analysed data from primary studies. Electronic English databases, including PubMed, Embase, CINAHL and Cochrane Library, and three Chinese databases were searched from inception to 1 July 2022. Studies were included if they performed a review of barriers and facilitators to KMC. Quality assessment of the retrieved reviews was performed by at least two reviewers independently using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist and risk of bias was assessed with the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) tool. This umbrella review protocol was documented in the PROSPERO registry (CRD42022327994).

We generated 531 studies, and after the removal of duplicates and ineligible studies, six eligible reviews were included in the analysis. The five themes identified were environmental factors, professional factors, parent/family factors, access factors, and cultural factors, and the factors under each theme were divided into barriers or facilitators depending on the specific features of a given scenario.

Conclusions

Support from facility management and leadership and well-trained medical staff are of great significance to the successful integration of KMC into daily medical practice, while the parents of preterm infants and other family members should be educated and encouraged in KMC practice. Further research is needed to propose strategies and develop models for implementing KMC.

Peer Review reports

According to reports from the World Health Organization (WHO), with the development of assisted reproductive technology and the improvement of emergency and critical care technology, the incidence of premature birth is rising, and premature birth has become a global problem [ 1 ]. Nearly fifteen million preterm infants are born each year, and more than one million of them unfortunately die each year [ 2 ]. According to statistics, complications of preterm birth directly account for more than 35% of all neonatal deaths, while the proportion of deaths indirectly caused by preterm birth is even higher because preterm birth increases the risk of infant death from infection [ 3 ]. Many surviving preterm infants encounter plenty of problems due to premature birth, such as sensory impairment and cognitive and language impairment [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. In addition, the birth of preterm infants may cause a substantial emotional crisis and economic cost to the family, as well as have an impact on public sector services such as education and other social support systems [ 7 , 8 ]. For mothers, preterm birth may also cause a range of perinatal diseases [ 5 , 9 ]. Therefore, effective evidence-based interventions that can be implemented at scale are urgently needed to reduce the incidence of preterm birth complications and neonatal mortality.

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is one such evidence-based life-saving intervention for preterm infants [ 10 ]. In KMC, the mother (or father) puts her (his) naked preterm infant on her (his) chest in the same way as kangaroo parenting so that the preterm infant is capable of having early, continuous and long-term skin-to-skin contact with his or her mother (father); in addition, measures such as exclusive breastfeeding or breastfeeding, early discharge, and follow-up after discharge are taken for the preterm infants [ 11 , 12 ]. Compared with the conventional nursing mode, KMC is not only able to maintain the body temperature of preterm infants but also significantly reduces the risk of death in low-birth-weight infants by 36% while significantly reducing the risk of sepsis, hypoglycaemia, and hypothermia [ 13 ]. Numerous studies have shown that KMC is a safe, effective, and multifaceted intervention with many short-term and long-term positive effects for preterm infants, such as stabilizing the neonatal physiological state, enhancing immunity, increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates, and promoting mother-infant bonding [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

Despite the clear benefits of KMC, this intervention has not yet been fully integrated into health systems around the world [ 18 , 19 ]. There are many barriers impeding the implementation of the KMC, including but not limited to lack of support from family members, lack of parental information, and lack of tools and resources [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Several studies have identified facilitators that may contribute to the implementation of KMC, such as providing KMC training programmes for parents and encouraging physicians to recommend KMC to parents [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Undoubtedly, a better understanding of these barriers and facilitators can optimize the implementation of KMC.

Studies on the subject of KMC have developed over many years, with extensive studies from around the world and several systematic reviews on KMC published. These studies spanned different clinical settings, and there are studies that have explored the influencing factors of KMC from different perspectives, such as caregivers (e.g., parents and families) and healthcare workers [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. A certain number of barriers and facilitators have been identified in these studies. However, the complexity and diversity of conventional studies make KMC difficult to describe and understand and impose challenges for health professionals and administrators who try to apply KMC in health systems [ 22 , 30 ]. Therefore, it is necessary to robustly summarize the evidence base to identify and elucidate key barriers and facilitators to the implementation of KMC.

One available approach is the umbrella review, which involves the synthesis of existing reviews, enabling researchers to collect evidence from multiple healthcare facilities instead of conducting systematic reviews at each facility. Essentially, an umbrella review is a review of existing reviews to provide an overview of the available evidence on a specific topic and allow comparisons of published reviews [ 31 ]. Furthermore, an umbrella review is capable of compiling evidence bases related to specific issues in a relatively short time frame [ 32 ]. We adopted this comprehensive assessment approach to outline factors that may facilitate or inhibit KMC implementation and expansion.

Protocol and registration

A protocol was prospectively developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [ 33 ]. Following current recommendations, the protocol was made openly available through registration with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews platform (registration number CRD42022327994).

Study design

This review was conducted according to the rules for conducting umbrella reviews and published approach [ 32 , 34 ], and was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA 2020) statement [ 35 ]. The PRISMA checklist is shown in Additional file 1 .

Search strategy

Electronic databases, including PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, for Chinese literature), SinoMed (for Chinese literature), and WAN FANG DATA (for Chinese literature), were searched to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses (published from database inception to 1 July 2022.) of the factors influencing the implementation of KMC in preterm infants. Additionally, we manually searched reference lists from the screened articles to avoid the omission of any related articles. Also, we searched Google Scholar and OpenGrey for grey literature.

The search terms were constructed by combining subject terms and free words, while the language was limited to Chinese or English. The English search terms used were “prematur*/preterm*/premie*/neonat*/infant*/newborn*/low birth weight/LBW/ NICU”, “kangaroo mother care/kangaroo mother method/kangaroo care/kangaroo attachment/kangaroo contact/KMC/KC/skin-to-skin care/skin-to-skin contact/SSC/mother-infant contact”, and “systematic review/meta-analys”, and “早产儿/新生儿/低出生体重儿”“袋鼠护理/袋鼠式护理/皮肤接触”“系统评价/Meta分析/荟萃分析” were adopted as the Chinese search terms. More details of the search strategies are shown in Additional file 2 .

Inclusion criteria

This umbrella review included studies published in peer-reviewed journals and grey literature that addressed the research question. Articles were included if they were published in Chinese, English or in other language with the English version; identified factors impacting KMC implementation, including barriers and facilitators as primary or secondary objectives; and were a systematic review or meta-analysis. Moreover, to retrieve valuable information about the subject under study, we also decided to include scoping reviews, a type of review study that uses a systematic method of searching for information with the aim of accumulating as much evidence as possible and mapping the results. Screening of the searched articles and their subsequent full-text review were carried out based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) studies that used a systematic/scoping review and/or meta-analysis design, (b) studies focused on preterm infants with KMC, and (c) studies that aimed to identify factors associated with KMC implementation. In addition, articles fulfilling the following criteria were excluded: (a) reviews written in any language other than English or Chinese, (b) duplicate publications, and (c) articles or conference abstracts for which the full text was not available.

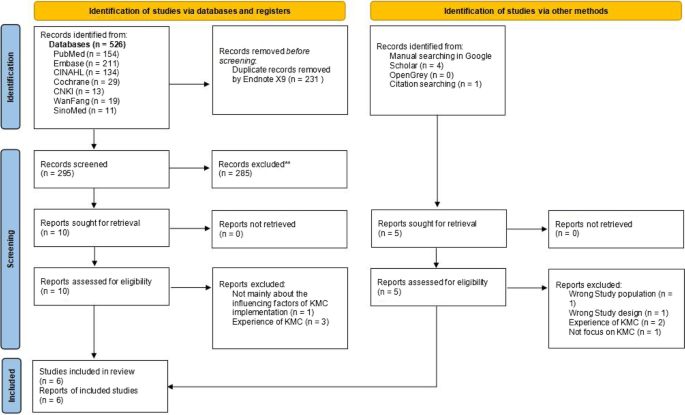

Study selection

Two researchers independently screened the literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, the two researchers first discussed and attempted to resolve the disagreement. If the disagreement could not be resolved, a third researcher was invited to adjudicate. The literature screening process was as follows: (1) Endnote (a literature management software) was used to remove duplicate records; (2) the title and abstract of the articles were read in Endnote, and those that were not related to the subject, population and literature type were removed; (3) the full text of the remaining articles was downloaded, excluding those for which the full text could not be obtained; and (4) the full texts of the articles were read to further exclude literature according to the standard cited in the second step. The study selection process is summarized in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included reviews was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses [ 36 ]. This assessment tool comprises 11 items, and the evaluation criteria for each item are “yes”, “no”, “unclear” or “not applicable”. Two members independently assessed the retrieved articles. Any disagreement between them was resolved by a third investigator.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias of the included studies was evaluated by two reviewers using the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews (ROBIS) [ 37 ]. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted until a final decision was made. ROBIS assesses four domains: 1) study eligibility criteria; 2) identification and selection of studies; 3) data collection and study appraisal; and 4) synthesis and findings. Each domain consists of five to six questions with six possible options: Yes, Probably yes, Probably No, No, Not indicated or Not applicable.

Data extraction

Two researchers independently used a unified Excel form that served as a data extraction sheet used to extract variables that were relevant to the scope of the current review, and another researcher verified the accuracy of the data extraction and quality assessment of all the included reviews. The extracted variables included the type of review, years covered, the total number of studies included in the review, country of origin, settings, aims/objectives and participants. As the aim was to provide a broad overview, all barriers and facilitators in all of the reviews were extracted except for those that were infrequently reported (i.e., those reported by only a few studies).

Data synthesis

After the data were extracted, a qualitative content analysis of the factors impacting KMC implementation was undertaken by the researcher. Each review article was read carefully to identify and extract the reported barriers and facilitators, and the researcher prepared the tables to summarize the data of all articles (see Additional file 3 ). The main key factors extracted from the articles were grouped and classified into themes to enhance the comprehension of the results outcomes. This classification of findings was performed based on the identified factors from the studies included in this review. Any uncertainties regarding the thematic categorizations were resolved through discussion and consensus by the reviewers.

Five hundred and thirty one hits retrieved in the initial search were exported into the reference management software Endnote, and 300 of them was left after duplicate records were excluded. A total of 285 references whose subject and theme were not matched were removed after title and abstract screening. Six eligible reviews were included after further full-text screening of the remaining 15 articles, as shown in Fig. 1 .

PRISMA flow diagram of barriers and facilitators to implementing KMC

Study characteristics

Table 1 provides an overview of five systematic reviews and one scope review related to KMC implementation as of July 1, 2022, all of which were published in 2015 and later, indicating this topic is relatively fresh. Two of the six articles described barriers and facilitators of KMC implementation from the perspective of caregivers of preterm infants [ 27 , 39 ]; one article explored these influencing factors from the the perspective of healthcare workers [ 28 ]; and the remaining articles discussed the factors affecting KMC implementation from both the perspectives of healthcare workers and parents of preterm infants [ 29 , 38 , 40 ].

The number of studies included in each review varied significantly, which often depended on the inclusion scope of the review [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. For instance, two most recently published reviews included a smaller number of studies as it defined a specific study area [ 29 , 39 ]. Most of the studies included in the reviews were carried out in low-and middle-income counties and were conducted in health facility.

The methodological quality of the included 6 articles was evaluated by the JBI critical appraisal checklist. The ninth item “Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed” for all the included articles was “No” because publication bias are not assessed in all the included reviews. As the tools for evaluating the quality of the included studies and how to evaluate the quality of the included studies were not described in the two studies conducted by Seidman et al. [ 38 ] and Mathias et al. [ 39 ], so the fifth item “Were the criteria for appraising studies appropriate” and the sixth item “Was critical appraisal conducted by two or more reviewers independently” for these two studied was “No”, and the evaluation results of the remaining items were all “Yes”. The results of the quality appraisal of all the included studies are displayed in Additional file 4 .

After applying the ROBIS tool for risk of bias evaluation, of the six included systematic reviews, four were evaluated to have a high bias risk [ 27 , 28 , 38 , 40 ], and two present an unclear bias risk [ 29 , 39 ] (see Additional file 5 ). Main concerns regarding this aspect were related to (a) limiting searches with language restrictions; (b) lack of risk of bias evaluation; and (c) selection and data extraction not done in duplicate.

Barriers and facilitators of KMC

The five themes identified were environmental factors, professional factors, parent/family factors, access factors, and cultural factors. The subfactors under each theme were divided into barriers or facilitators according to the descriptions provided in the included reviews. A brief summary of the barriers and facilitators identified under each theme is presented in Table 2 . These are described in more detail below.

Environmental factors

This theme comprised facility conditions, resources and materials, and the healthcare system. Facility conditions mainly refer to hardware support in medical institutions, the most common factors being space and privacy. Lack of privacy and insufficient space and supplies directly hinder the implementation of KMC [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], while access to private space/privacy screens and sufficient space and supplies are key facilitators for the implementation of KMC [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 40 ]. In addition, factors such as temperature stability and a quiet and relaxed atmosphere in clinical facilities are conducive to the implementation of KMC [ 27 , 28 , 40 ]. Resources and materials refer to the environmental software support mainly related to resource management and material access. The most common barrier is a lack of KMC guidelines or protocols in the clinical unit [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 38 ], while the implementation of KMC would be enhanced if the clinical unit adopted KMC guidelines or protocols and displayed KMC pictures/posters, etc. [ 28 , 29 , 39 ]. The healthcare system mainly involves educational and policy factors. Inadequate/inconsistent training and unsupportive staffing policies are barriers to KMC implementation [ 28 , 29 , 39 , 40 ], while the integration of KMC into the healthcare curriculum and KMC-related policies are important facilitators for KMC implementation [ 29 , 40 ].

Professional factors

This theme encompassed three subthemes: professional perception, professional characteristics, and professional management. The main barriers under this theme included medical staff’s lack of belief in the efficacy or importance of the KMC [ 38 , 40 ] and their perceptions that KMC is unsafe [ 28 , 39 ] and imposes extra workload on them [ 38 ], the limited level of experience and knowledge of health care workers [ 28 , 29 , 38 ] and lack of communication with each other [ 28 ], high staff and leadership turnover [ 28 , 40 ] and lack of leadership and management support [ 28 , 38 , 40 ]. The main facilitators under this theme included medical staff’s belief in KMC benefits [ 28 , 29 , 40 ] and their sufficient experience, passion, and willingness to implement KMC [ 28 , 29 , 39 ]; leadership and management support [ 29 , 40 ]; and multiple health worker support [ 28 , 39 ].

Parent/family factors

This theme involved parental perception and motivation, parenting capacity, and parental support and empowerment. Experienced and perceived discomfort [ 29 , 39 ], a lack of awareness of the benefits of KMC [ 27 , 29 , 38 , 39 ], and fear/anxiety of hurting the infant [ 38 ] were the most frequently identified barriers to the implementation of KMC. Parenting capacity mainly refers to the health state of the parents of preterm infants. Medical issues such as pain/fatigue [ 27 , 38 , 40 ] and postpartum depression [ 27 , 29 , 38 ] and lack of confidence and knowledge on KMC [ 39 ] were the most common barriers. Support and empowerment refer to the availability of support from family members [ 27 , 29 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], medical staff [ 28 , 29 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], community [ 39 , 40 ], and peers [ 28 , 29 ], which facilitates the implementation of KMC and hinders implementation otherwise.

Access factors

This theme involved time, location, and financing. For medical staff, time was a key barrier; staff perceived that the implementation of KMC would increase their workload [ 28 , 29 , 38 , 40 ] and reduce time with other critical patients [ 28 , 40 ], and they had difficulty finding time for training [ 40 ]. For the parents of preterm infants, commuting from home and the medical unit was another barrier that caregivers were unable to devote sufficient time in KMC practice due to long commutes [ 27 ] or dealing with heavy household chores [ 39 ]. The costs of transportation, accommodation renting, and KMC implementation in the clinical ward were the immediate challenges [ 27 , 38 , 40 ]. Lower hospital costs to family [ 27 , 29 , 40 ], lower cost for health system [ 29 ] and unlimited visitation hours [ 27 , 28 , 40 ] were conducive to the implementation of KMC.

Cultural factors

This theme comprised traditional newborn care, traditional mindset, and gender roles. Traditional newborn care approaches, such as traditional bathing, carrying and breastfeeding practices [ 27 , 28 , 40 ], and the type of wrap [ 39 ] were identified as barriers to the implementation of KMC. However, some aspects of newborn care facilitated the implementation of KMC, i.e., advising mothers to delay bathing [ 28 ]. Some mindsets such as feeling ashamed of having a preterm infant [ 27 , 38 , 40 ], believing that skin-to-skin contact between the preterm infants and their caregivers was inappropriate [ 29 , 38 , 39 ] and considering KMC to be taboo [ 39 ] were identified barriers to the KMC implementation. Additionally, gender inequality existing in the division of labour between fathers and mothers [ 27 , 38 ] was not conducive to the implementation of KMC that KMC was regarded as a role responsibility of the mother, and the father was not allowed to participate in KMC [ 38 , 39 , 40 ] .

Our umbrella review highlighted different factors, each factor comprising barriers and facilitators, that influence the implementation of KMC, provide decision-makers in healthcare with an overview of the field and provide information for the implementation of KMC. All of the included reviews were published in 2015 or later, which confirms the growth and interest in the field of KMC. However, there is considerable heterogeneity in the evidence base on KMC, which makes translation into practice challenging.

Factors related to facility conditions, mainly including lack of privacy and insufficient space and supplies, were mentioned in all six included reviews, which might be related to the operation characteristics of KMC. Skin-to-skin contact is the most important part of the KMC procedure, which requires parents to undress their upper bodies and put their preterm infants on their chests, which is why a suitable physical environment is of great significance [ 11 , 12 ]. Studies have reported that mothers felt uncomfortable and exposed due to the continuous coming and going of medical staff during KMC when insufficient KMC private space was provided, which has proved to be a serious barrier affecting the implementation of KMC in many countries around the world [ 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Therefore, medical units should strive to provide enough quiet, comfortable, and private space for NICUs to implement KMC. Apart from physical facility conditions, resources and materials were another factor. Limited by facility space and human resources, some hospitals in China had to perform intermittent KMC instead of continuous KMC [ 44 ]. A multicountry analysis of health system bottlenecks from 12 African and Asian countries reported that insufficient essential supplies in facilities to support KMC was a barrier to the implementation of KMC [ 21 ].

KMC should be systematically implemented within a facility in accordance with relevant rules and regulations, for example, by adopting standard checklists for mothers and infants to ensure orderly and standardized KMC implementation. In a majority of the hospitals, nurses were required to commit to KMC-related tasks such as KMC recording, assessment, and data monitoring due to the lack of relevant rules and regulations, which meant an extra workload for the nurses [ 45 , 46 ]. Studies have shown that human resource challenges, record keeping, and data collection are barriers to KMC implementation in countries such as Malawi and Indonesia [ 28 , 47 ]. Documentation and annotation of KMC implementation were still not common practices in NICUs, while KMC-related information was imported through electronic medical records in most cases [ 28 , 48 ]. Chan et al. noted that the implementation of KMC was promoted when medical units improved their electronic medical records to allow nurses to record the onset and duration of KMC [ 28 ]. Therefore, the Ministry of Health and government agencies should formulate practical KMC implementation guidelines based on local conditions, and medical units should also formulate and standardize KMC implementation guidelines and programs to promote the implementation of KMC.

Lack of proper leadership, insufficient professionalism of personnel, and insufficient training were also obstacles to KMC implementation. A study on the introduction of KMC in Indonesian hospitals found that government support, hospital management, staff acceptance, and training were identified as key facilitators of KMC implementation [ 47 ]. In some regions, KMC-specific training programs were provisioned for medical staff by the government [ 49 ]. However, the number of staff participating in the training is very limited due to the long distance between the training site and the medical unit and the shortage of personnel in the hospitals, although many medical personnel were willing to participate in the training [ 42 , 50 ]. In other words, although policymakers and decision-makers tried to provide assistance and intervention programs for healthcare workers, they did not anticipate these barriers to attendance. Of course, the support from hospital administrators and leadership could provide more space and human resources to provision KMC, optimize or update the staffing configuration of neonatal care nurses, strengthen the professionalization of neonatal care by healthcare workers, and improve healthcare staff’s attitudes towards and perceptions of KMC [ 43 , 51 ].

The attitudes of the health caregivers towards KMC were also a factor influencing the adoption of KMC for parents. If there were staff in the hospital who were familiar with KMC and willing to educate parents on KMC knowledge, it would help parents of preterm infants to acquire KMC-related knowledge, which would promote KMC preferences and the early initiation of KMC [ 52 , 53 ]. Correspondingly, insufficient awareness of KMC and infant health among parents/family members was a barrier to the practice of KMC [ 22 ]. Despite the generally low awareness of KMC, the reviews reported that it was relatively easier to train mothers on KMC practices and that they were more adherent to KMC practices after understanding and accepting KMC [ 54 ]. Perceived, observed, and experienced effects of KMC could provide comfort and satisfaction to the parents of preterm infants, which promotes KMC use, whereas KMC is inhibited if parents and/or preterm infants experience KMC-related discomfort.

Lack of assistance is a barrier to KMC practice, whereas support from family, friends, and other mothers is a facilitator to the implementation of KMC. There were many different forms of support. For example, family members took turns embracing the preterm infants to free the mother from this practice [ 55 , 56 ]. Evidence from the literature has suggested that emotional support, as well as support and help with household chores, is also a facilitator for mothers [ 57 , 58 ]. Kangaroo nursing can be implemented not only by mothers but also by fathers, grandfathers, grandmothers, and other family members of preterm infants [ 43 , 59 ], and if family members do not understand this point, preterm infants might lose the opportunity to receive kangaroo care [ 60 ]. Therefore, different educational approaches should be adopted to educate families of preterm infants about their roles in KMC, with additional health promotions and activities targeting grandparents and other family members about the benefits of KMC and the significance of supporting mothers, which may increase the number of people receiving KMC.

However, KMC is not suitable for all situations. In some clinical scenarios where mothers of preterm infants have special health conditions, it could be very challenging to train mothers and facilitate KMC implementation. These challenges include the infant being too difficult to embrace, the infant being too heavy, and the mother experiencing chest or back discomfort or pain/fatigue [ 38 ]. The reviews showed that mothers’ medical conditions, including postepisiotomy pain repair [ 61 ], postcesarean recovery [ 62 ], postpartum depression and general maternal illness [ 48 ], were another challenge for KMC practice. Additionally, mothers may mentally struggle with KMC practices, including positioning problems (difficulty sleeping on the chest with infants), breast milk expression, and other breastfeeding-related issues [ 57 , 63 ]. In this case, family support and father involvement make a great difference [ 64 ]. Postpartum depression is a barrier to the implementation of KMC, but interestingly, mothers who practised KMC experienced reduced symptoms of postpartum depression [ 65 , 66 ].

Inviting parents to the NICU to perform KMC could result in extra costs. Studies performed in low-income countries have shown that commuting between home and KMC wards was a barrier to the implementation of KMC, and fees for mothers and babies staying in KMC wards were also considered a barrier [ 39 , 67 ]. Studies have shown that higher economic status is more conducive to the implementation of KMC [ 40 , 43 ]. Therefore, accessing financial resources from hospital administration and/or parental health insurance to facilitate KMC would be a necessary part of KMC expansion. Meanwhile, it is necessary to consider how to reduce hospital charges or provide certain transportation subsidies for families with infants whose hospitalization time exceeds the average length of stay. Limited visiting time in the NICU is another obstacle to the implementation of KMC, especially in the case of closed management such as the NICU in China. Extending the visit time could increase the adoption of KMC to some extent [ 68 , 69 ].

Different cultures, religions, and traditional beliefs in different countries influence perceptions of preterm infants and KMC. In many countries, carrying infants on the chest rather than on the back is considered inappropriate [ 41 ], and some cultures believe that skin-to-skin contact between an infant and his or her caregiver is not appropriate [ 27 ]. Understanding these culturally specific barriers, it is of great importance to adapt KMC promotion programmes to the needs of the population. In some countries, mothers are ridiculed for giving birth to preterm infants, which results in stigma [ 55 , 70 ]. Studies have reported that stigma about preterm infants creates anxiety and guilt in mothers, causing them to abandon their infants, which is a factor hindering the implementation of KMC [ 27 , 38 ]. Muddu et al. [ 71 ] found that fondness was an enabler for parents to accept their preterm infants and utilize KMC to support the improvement of their preterm infants’ health. Cultural barriers also encompass the practice of postpartum confinement and traditional resistance to confinement from grandparents and community members. Most mothers are advised to stay home after delivery in China and India [ 72 , 73 ], which has potential health benefits for mothers and newborns, but it also causes mothers and families to be hesitant to adopt KMC.

Traditional gender role factors were identified as barriers to male participation in neonatal care. KMC was regarded as a breach of social duty or responsibility by mothers in some countries where it is believed that mothers should take care of the family, and when mothers comply with this social duty and gender responsibility, the implementation of KMC becomes a challenge [ 74 ]; meanwhile, fathers are not encouraged to participate in KMC implementation in such cultures. Therefore, it is of great significance to develop interventions on how to encourage fathers to participate in KMC and reduce the stigma surrounding this infant care strategy [ 75 ]. As Dumbaugh et al. [ 76 ] pointed out, the inclusion of males in neonatal care must be done in a way that empowers women. Fathers who are successfully involved in KMC might become peer mentors or examples for others to address the problem of fathers’ reluctance to participate in neonatal care. The name of the intervention, “kangaroo mother care”, could also be modified, e.g., to “kangaroo care”, so that it does not directly imply that the practice is performed only by mothers.

Limitations

The findings in this manuscript are subject to some limitations. First, due to resource constraints, we only searched for English and Chinese reviews, and there was a possibility of missing some relevant studies. Another limitation of the umbrella review approach was that it could only report on what researchers have investigated and published [ 32 ]. For example, some factors might be highly influential, but if they were not adequately investigated in the included studies, they might be reported as less important, or they might not even be included in the review. To mitigate this issue, other key literature not identified in this review was actively referenced. Finally, a potential limitation to the umbrella review approach could be the risk that bias is transmitted upwards from primary studies to the reviews and then to the umbrella review.

Recommendations for future research

KMC implementation issues are likely to differ among different regions, so there remains a need for further research into sustainable development mechanisms in varied settings to promote the adoption of KMC. The generalizability of the findings worldwide and their translation into practice is uncertain. Most of the studies focused at the facility level, such as the NICU, which highlights the lack of community-level studies. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the factors influencing KMC implementation at home and in the community. Male involvement was identified as a facilitator to KMC implementation, but there was no study discussing hindrance factors of father involvement in care specifically. Therefore, further research is also needed to explore the hindrance and/or facilitating factors of male involvement in KMC care from the perspective of fathers. In addition, further research is also needed to test models for addressing barriers and supporting facilitators to promote and implement context-specific health system changes for greater uptake of KMC.

KMC is a complicated intervention that encounters unique barriers and facilitators in different aspects of healthcare systems. Our umbrella review prioritizes the main factors influencing KMC implementation and highlights some key areas that implementers and implementation researchers may need to focus on. KMC should be implemented more systematically and continuously to strengthen and expand its adoption.

The parents of preterm infants and other family members, the medical unit, and the medical staff contribute to a dynamic whole as a triangle, that are closely linked with one another. Support from facility management and leadership and well-trained medical staff are of great significance to the successful integration of KMC into daily medical practice, while the parents of preterm infants and other family members should be educated and encouraged to adopt KMC practice. Effectively integrating KMC into current health systems by addressing barriers and building trust will greatly improve neonatal survival rates.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data were extracted from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

World Health Organization. Preterm birth. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (Accessed 13 May 2022).

Google Scholar

Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME), WHO, World Bank Group and United Nations. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2019, Estimates developed by the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/levels-and-trends-child-mortality-report-2019 (Accessed 16 May 2022)

Allotey J, Zamora J, Cheong-See F, Kalidindi M, Arroyo-Manzano D, Asztalos E, et al. Cognitive, motor, behavioural and academic performances of children born preterm: a meta-analysis and systematic review involving 64 061 children. BJOG. 2018;125(1):16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14832 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ream MA, Lehwald L. Neurologic Consequences of Preterm Birth. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(8):48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-018-0862-2 .

Dean B, Ginnell L, Ledsham V, Tsanas A, Telford E, Sparrow S, et al. Eye-tracking for longitudinal assessment of social cognition in children born preterm. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(4):470–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13304 .

Hodek JM, von der Schulenburg JM, Mittendorf T. Measuring economic consequences of preterm birth - Methodological recommendations for the evaluation of personal burden on children and their caregivers. Health Econ Rev. 2011;1(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-1991-1-6 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Behrman RE, Butler AS, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 2007.

Trumello C, Candelori C, Cofini M, Cimino S, Cerniglia L, Paciello M, et al. Mothers’ Depression, Anxiety, and Mental Representations After Preterm Birth: A Study During the Infant's Hospitalization in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Front Public Health. 2018;6:359. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00359 .

World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Interventions to Improve Preterm Birth Outcomes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241508988 (Accessed 16 May 2022)

World Health Organization. Kangaroo mother care: a practical guide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241590351 (Accessed 17 May 2022).

Chan GJ, Valsangkar B, Kajeepeta S, Boundy EO, Wall S. What is kangaroo mother care? Systematic review of the literature. J Glob Health. 2016;6(1):010701. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.010701 .

Boundy EO, Dastjerdi R, Spiegelman D, Fawzi WW, Missmer SA, Lieberman E, et al. Kangaroo Mother Care and Neonatal Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):e20152238. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2238 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Conde-Agudelo A, Díaz-Rossello JL. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(8):CD002771. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002771 .

Sharma D, Farahbakhsh N, Sharma S, Sharma P, Sharma A. Role of kangaroo mother care in growth and breast feeding rates in very low birth weight (VLBW) neonates: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(1):129–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2017.1304535 .

Cho ES, Kim SJ, Kwon MS, Cho H, Kim EH, Jun EM, et al. The Effects of Kangaroo Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit on the Physiological Functions of Preterm Infants, Maternal-Infant Attachment, and Maternal Stress. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(4):430–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.007 .

Furman L. Kangaroo mother care 20 years later: connecting infants and families. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20163332. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3332 .

Stefani G, Skopec M, Battersby C, Matthew H. Why is Kangaroo Mother Care not yet scaled in the UK? A systematic review and realist synthesis of a frugal innovation for newborn care. BMJ Innov. 2022;8:9–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2021-000828 .

Article Google Scholar

Salim N, Shabani J, Peven K, Rahman QS, Kc A, Shamba D, et al. Kangaroo mother care: EN-BIRTH multi-country validation study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(Suppl 1):231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03423-8 .

Bergh AM, Kerber K, Abwao S, de Graft Johnson J, Aliganyira P, Davy K, et al. Implementing facility-based kangaroo mother care services: lessons from a multi-country study in Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:293. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-293 .

Vesel L, Bergh AM, Kerber KJ, Valsangkar B, Mazia G, Moxon SG, et al. Kangaroo mother care: a multi-country analysis of health system bottlenecks and potential solutions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(Suppl 2):S5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-15-S2-S5 .

Bilal SM, Tadele H, Abebo TA, Tadesse BT, Muleta M, W/Gebriel F, et al. Barriers for kangaroo mother care (KMC) acceptance, and practices in southern Ethiopia: a model for scaling up uptake and adherence using qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03409-6 .

Saltzmann AM, Sigurdson K, Scala M. Barriers to Kangaroo Care in the NICU: A Qualitative Study Analyzing Parent Survey Responses. Adv Neonatal Care. 2022;22(3):261–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000907 .

Mathias CT, Mianda S, Ginindza TG. Facilitating factors and barriers to accessibility and utilization of kangaroo mother care service among parents of low birth weight infants in Mangochi District, Malawi: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02251-1 .

Maniago JD, Almazan JU, Albougami AS. Nurses’ Kangaroo Mother Care practice implementation and future challenges: an integrative review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(2):293–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12755 .

Cattaneo A, Amani A, Charpak N, De Leon-Mendoza S, Moxon S, Nimbalkar S, et al. Report on an international workshop on kangaroo mother care: lessons learned and a vision for the future. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1819-9 .

Smith ER, Bergelson I, Constantian S, Valsangkar B, Chan GJ. Barriers and enablers of health system adoption of kangaroo mother care: a systematic review of caregiver perspectives. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0769-5 .

Chan G, Bergelson I, Smith ER, Skotnes T, Wall S. Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care implementation from a health systems perspective: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(10):1466–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx098 .

Kinshella MW, Hiwa T, Pickerill K, Vidler M, Dube Q, Goldfarb D, et al. Barriers and facilitators of facility-based kangaroo mother care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03646-3 .

Bergh AM, de Graft-Johnson J, Khadka N, Om'Iniabohs A, Udani R, Pratomo H, et al. The three waves in implementation of facility-based kangaroo mother care: a multi-country case study from Asia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-016-0080-4 .

Hunt H, Pollock A, Campbell P, Estcourt L, Brunton G. An introduction to overviews of reviews: planning a relevant research question and objective for an overview. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0695-8 .

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055 .

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Mental Health. 2018;21(3):95–100. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2017 edition. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP, Caldwell DM, Reeves BC, Shea B, et al. ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 .

Seidman G, Unnikrishnan S, Kenny E, Myslinski S, Cairns-Smith S, Mulligan B, et al. Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care practice: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125643 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mathias CT, Mianda S, Ohdihambo JN, Hlongwa M, Singo-Chipofya A, Ginindza TG. Facilitating factors and barriers to kangaroo mother care utilisation in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2021;13(1):e1–e15. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.2856 .

Chan GJ, Labar AS, Wall S, Atun R. Kangaroo mother care: a systematic review of barriers and enablers. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(2):130–141J. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.157818 .

Charpak N, Ruiz-Peláez JG. Resistance to implementing kangaroo mother care in developing countries, and proposed solutions. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(5):529–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250600599735 .

Ferrarello D, Hatfield L. Barriers to skin-to-skin care during the postpartum stay. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2014;39(1):56–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NMC.0000437464.31628.3d .

Yue J, Liu J, Williams S, Zhang B, Zhao Y, Zhang Q, et al. Barriers and facilitators of kangaroo mother care adoption in five Chinese hospitals: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09337-6 .

Zhang B, Duan Z, Zhao Y, Williams S, Wall S, Huang L, et al. Intermittent kangaroo mother care and the practice of breastfeeding late preterm infants: results from four hospitals in different provinces of China. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00309-5 .

Shah RK, Sainju NK, Joshi SK. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Kangaroo Mother Care. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2018;15(3):275–81. https://doi.org/10.3126/jnhrc.v15i3.18855 .

Adisasmita A, Izati Y, Choirunisa S, Pratomo H, Adriyanti L. Kangaroo mother care knowledge, attitude, and practice among nursing staff in a hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252704 .

Pratomo H, Uhudiyah U, Sidi IP, Rustina Y, Suradi R, Bergh AM, et al. Supporting factors and barriers in implementing kangaroo mother care in Indonesia. Paediatrica Indonesiana. 2012;52(1):43–50. https://doi.org/10.14238/pi52.1.2012.43-50 .

Lee HC, Martin-Anderson S, Dudley RA. Clinician perspectives on barriers to and opportunities for skin-to-skin contact for premature infants in neonatal intensive care units. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(2):79–84. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2011.0004 .

Sacks E, Bailey JM, Robles C, Low LK. Neonatal care in the home in northern rural Honduras: a qualitative study of the role of traditional birth attendants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013;27(1):62–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e31827fb3fd .

Bergh AM, Rogers-Bloch Q, Pratomo H, Uhudiyah U, Sidi IP, Rustina Y, et al. Progress in the implementation of kangaroo mother care in 10 hospitals in Indonesia. J Trop Pediatr. 2012;58(5):402–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmr114 .

Yue J, Liu J, Zhao Y, Williams S, Zhang B, Zhang L, et al. Evaluating factors that influenced the successful implementation of an evidence-based neonatal care intervention in Chinese hospitals using the PARIHS framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07493-6 .

Deng Q, Zhang Y, Li Q, Wang H, Xu X. Factors that have an impact on knowledge, attitude and practice related to kangaroo care: National survey study among neonatal nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(21–22):4100–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14556 .

Kinshella MW, Salimu S, Chiwaya B, Chikoti F, Chirambo L, Mwaungulu E, et al. “So sometimes, it looks like it's a neglected ward”: Health worker perspectives on implementing kangaroo mother care in southern Malawi. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243770 .

Gill VR, Liley HG, Erdei C, Sen S, Davidge R, Wright AL, et al. Improving the uptake of Kangaroo Mother Care in neonatal units: A narrative review and conceptual framework. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(5):1407–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15705 .

Nguah SB, Wobil PN, Obeng R, Yakubu A, Kerber KJ, Lawn JE, et al. Perception and practice of Kangaroo Mother Care after discharge from hospital in Kumasi, Ghana: a longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11:99. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-11-99 .

Kymre IG, Bondas T. Skin-to-skin care for dying preterm newborns and their parents--a phenomenological study from the perspective of NICU nurses. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(3):669–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01076.x .

Chugh Sachdeva R, Mondkar J, Shanbhag S, Manuhar M, Khan A, Dasgupta R, et al. A Qualitative Analysis of the Barriers and Facilitators for Breastfeeding and Kangaroo Mother Care Among Service Providers, Mothers and Influencers of Neonates Admitted in Two Urban Hospitals in India. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14(2):108–14. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0177 .

Ariff S, Maznani I, Bhura M, Memon Z, Arshad T, Samejo TA, et al. Understanding Perceptions and Practices for Designing an Appropriate Community-Based Kangaroo Mother Care Implementation Package: Qualitative Exploratory Study. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(1):e30663. https://doi.org/10.2196/30663 .

Kuo SF, Chen IH, Chen SR, Chen KH, Fernandez RS. The Effect of Paternal Skin-to-Skin Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Adv Neonatal Care. 2022;22(1):E22–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000890 .

Mu PF, Lee MY, Chen YC, Yang HC, Yang SH. Experiences of parents providing kangaroo care to a premature infant: A qualitative systematic review. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22(2):149–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12631 .

Brimdyr K, Widström AM, Cadwell K, Svensson K, Turner-Maffei C. A Realistic Evaluation of Two Training Programs on Implementing Skin-to-Skin as a Standard of Care. J Perinat Educ. 2012;21(3):149–57. https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.21.3.149 .

Kymre IG, Bondas T. Balancing preterm infants’ developmental needs with parents’ readiness for skin-to-skin care: a phenomenological study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2013;8:21370. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v8i0.21370 .

Blomqvist YT, Frölund L, Rubertsson C, Nyqvist KH. Provision of Kangaroo Mother Care: supportive factors and barriers perceived by parents. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(2):345–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01040.x .

Filippa M, Saliba S, Esseily R, Gratier M, Grandjean D, Kuhn P. Systematic review shows the benefits of involving the fathers of preterm infants in early interventions in neonatal intensive care units. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110(9):2509–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15961 .

Kirca N, Adibelli D. Effects of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact on postpartum depression: A systematic review. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(4):2014–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12727 .

Scime NV, Gavarkovs AG, Chaput KH. The effect of skin-to-skin care on postpartum depression among mothers of preterm or low birthweight infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:376–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.101 .

Blencowe H, Kerac M, Molyneux E. Safety, effectiveness and barriers to follow-up using an ‘early discharge’ Kangaroo Care policy in a resource poor setting. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55(4):244–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/fmn116 .

Craig JW, Glick C, Phillips R, Hall SL, Smith J, Browne J. Recommendations for involving the family in developmental care of the NICU baby. J Perinatol. 2015;35(Suppl 1):S5–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.142 PMID: 26597804.

Calibo AP, De Leon MS, Silvestre MA, Murray JCS, Li Z, Mannava P, et al. Scaling up kangaroo mother care in the Philippines using policy, regulatory and systems reform to drive changes in birth practices. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(8):e006492. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006492 .

Hunter EC, Callaghan-Koru JA, Al Mahmud A, Shah R, Farzin A, Cristofalo EA, et al. Newborn care practices in rural Bangladesh: Implications for the adaptation of kangaroo mother care for community-based interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2014;122:21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.006 .

Muddu GK, Boju SL, Chodavarapu R. Knowledge and awareness about benefits of Kangaroo Mother Care. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80(10):799–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-013-1073-0 .

Wong J, Fisher J. The role of traditional confinement practices in determining postpartum depression in women in Chinese cultures: a systematic review of the English language evidence. J Affect Disord. 2009;116(3):161–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.002 .

Rao CR, Dhanya SM, Ashok K, Niroop SB. Assesment of cultural beliefs and practices during the postnatal period in a costal town of South India - A mixed method research study. Global J Med Public Health. 2014;3(5):1–8.

Opara PI, Okorie EMC. Kangaroo mother care: Mothers experiences post discharge from hospital. J Preg Neonatal Med. 2017;1(1):16–20. https://doi.org/10.35841/neonatal-medicine.1.1.16-20 .

Brotherton H, Daly M, Johm P, Jarju B, Schellenberg J, Penn-Kekana L, et al. “We All Join Hands”: Perceptions of the Kangaroo Method Among Female Relatives of Newborns in The Gambia. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(4):665–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320976365 .

Dumbaugh M, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Manu A, ten Asbroek GH, Kirkwood B, Hill Z. Perceptions of, attitudes towards and barriers to male involvement in newborn care in rural Ghana, West Africa: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:269. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-269 .

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nursing Department, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Qian Cai, Dan-Qi Chen & Rui Yang

Zhejiang University School of Medicine Women’s Hospital, No. 1 Xueshi Road, Shangcheng District, Hangzhou, 310006, Zhejiang Province, China

Qian Cai, Dan-Qi Chen, Hua Wang, Yue Zhang, Rui Yang & Xin-Fen Xu

Women’s Hospital School of Medicine Zhejiang University Haining Branch/Haining Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, No. 6 Qinjian Road, Haizhou Street, Haining, 314400, Zhejiang Province, China

Wen-Li Xu & Xin-Fen Xu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization, QC, XFX and HW; Methodology, QC, DQC and YZ; Validation, QC, DQC and RY and YZ; Formal Analysis, QC; Resources, QC, YZ and WLX; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, QC; Writing – Review & Editing, QC, DQC, RY and XFX; Supervision, XFX and HW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xin-Fen Xu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search strategies for English and Chinese databases.

Additional file 3.

1. Articles presenting barriers to implementing KMC. 2. Articles presenting facilitators to implementing KMC.

Additional file 4.

Result of the quality appraisal of included studies.

Additional file 5.

Risk of Bias analysis using ROBIS tool.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cai, Q., Chen, DQ., Wang, H. et al. What influences the implementation of kangaroo mother care? An umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22 , 851 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05163-3

Download citation

Received : 07 July 2022

Accepted : 27 October 2022

Published : 18 November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05163-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Kangaroo mother care

- Preterm birth

- Umbrella review

- Implementation

- Facilitators

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Barriers and Enablers of Kangaroo Mother Care Practice: A Systematic Review

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

Affiliation Boston Consulting Group, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

Affiliation Boston Consulting Group, New York City, New York, United States of America

Affiliation Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, Washington, United States of America

- Gabriel Seidman,

- Shalini Unnikrishnan,

- Emma Kenny,

- Scott Myslinski,

- Sarah Cairns-Smith,

- Brian Mulligan,

- Cyril Engmann

- Published: May 20, 2015

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125643

- Reader Comments

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is an evidence-based approach to reducing mortality and morbidity in preterm infants. Although KMC is a key intervention package in newborn health initiatives, there is limited systematic information available on the barriers to KMC practice that mothers and other stakeholders face while practicing KMC. This systematic review sought to identify the most frequently reported barriers to KMC practice for mothers, fathers, and health practitioners, as well as the most frequently reported enablers to practice for mothers. We searched nine electronic databases and relevant reference lists for publications reporting barriers or enablers to KMC practice. We identified 1,264 unique publications, of which 103 were included based on pre-specified criteria. Publications were scanned for all barriers / enablers. Each publication was also categorized based on its approach to identification of barriers / enablers, and more weight was assigned to publications which had systematically sought to understand factors influencing KMC practice. Four of the top five ranked barriers to KMC practice for mothers were resource-related: “Issues with the facility environment / resources,” “negative impressions of staff attitudes or interactions with staff,” “lack of help with KMC practice or other obligations,” and “low awareness of KMC / infant health.” Considering only publications from low- and middle-income countries, “pain / fatigue” was ranked higher than when considering all publications. Top enablers to practice were included “mother-infant attachment” and “support from family, friends, and other mentors.” Our findings suggest that mother can understand and enjoy KMC, and it has benefits for mothers, infants, and families. However, continuous KMC may be physically and emotionally difficult, and often requires support from family members, health practitioners, or other mothers. These findings can serve as a starting point for researchers and program implementers looking to improve KMC programs.

Citation: Seidman G, Unnikrishnan S, Kenny E, Myslinski S, Cairns-Smith S, Mulligan B, et al. (2015) Barriers and Enablers of Kangaroo Mother Care Practice: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0125643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125643

Academic Editor: Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, The Hospital for Sick Children, PAKISTAN

Received: August 22, 2014; Accepted: March 24, 2015; Published: May 20, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Seidman et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided funding for this review. Two authors (BM, CE) were employees of the foundation at the time of writing. They were not involved in collection or analysis of data, but did provide input into revisions / edits of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Preterm birth is a major global health issue, with 15 million preterm births occurring each year, and over 1 million of these preterm infants dying each year [ 1 ]. Preterm birth complications directly account for greater than 35% of all neonatal deaths each year, and preterm birth indirectly contributes to an even greater percentage because it increases the risk that an infant will die from infection. Preterm births are on the rise globally, both in high-income and low-income settings [ 1 ]. The 10 countries with highest rates of preterm births include those that are high-income, such as the USA, middle-income such as India, China, the Philippines, Indonesia and Brazil, and low-income such as Nigeria, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo [ 1 ]. Thus interventions that are feasible and applicable in both high- and low-income settings are highly desired.

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is an evidence-based approach to reducing mortality and morbidity in preterm infants which was first developed in Bogotá Colombia. According to the World Health Organization's definition, KMC consists of prolonged skin-to-skin (STS) contact between mother and infant, exclusive breastfeeding whenever possible, early discharge with adequate follow-up and support, and initiation of the practice in the facility and continuation at home [ 2 ]. In a meta-analysis, KMC was shown to significantly reduce preterm mortality at 40–41 weeks' corrected gestational age by 40% and to improve other outcomes including severe infection / sepsis, emotional attachment in mothers, and weight gain versus conventional neonatal care in preterm infants [ 3 ]. Another meta-analysis showed a similar mortality benefit, although it included fewer studies in its analysis [ 4 ]. Research from various countries also suggests that KMC is a cost-effective method for treating preterm infants [ 5 , 6 ], that mothers who have practiced KMC may find it acceptable [ 6 – 8 ], and that KMC can have a positive impact on the health of mothers in certain cases [ 9 , 10 ]. Therefore, KMC is a highly relevant intervention that should be considered for scaling across geographies. Although the WHO definition of KMC specifies that the practice should be initiated in a facility setting, several studies and trials have explored whether KMC can be effective in a community-initiated setting, and the effectiveness of KMC in this context has not yet been conclusively determined [ 11 , 12 ].

In spite of these benefits, mothers may face barriers to practice, some of which may prevent them from achieving the continuous STS contact with their infants (a defining feature of KMC). For example, a survey of 46 mothers of preterm infants who were trained on KMC in a facility in Andhra Pradesh, India found that only 6.5% of mothers felt that providing KMC for 12 hours / day or greater was feasible, whereas 52% of mothers felt that only 1 hour / day was practical[ 8 ]. Similarly, in a trial of community-initiated KMC with 1,565 mother-infant pairs, only 23.8% practiced STS for more than 7 hours / day in the first 48 hours of life, and the average number of hours of STS during days 3–7 of life was 2.7 ± 3.4 hours [ 11 ]. Barriers to the other components of KMC, including breastfeeding [ 12 , 13 ], and adequate follow-up after discharge [ 14 , 15 ], have also been noted.

KMC has emerged as a key intervention package for a number of newborn health initiatives, and this is epitomized by the Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP) [ 16 ]. Additionally a recent convening of ideas from 600 key programmers, policymakers, researchers and stakeholders in newborn health, using the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative [CHNRI] method, highlighted KMC as a top preterm intervention agenda [ 17 ]. Many agencies, such as Save the Children's Saving Newborn Lives III (SNL), USAID, WHO and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and some countries, such as Malawi and South Africa, have also made KMC a priority [ 18 – 22 ].

Therefore, to adequately implement and effectively scale-up this intervention, it is critical to understand the key factors that contribute to a mother's (in)ability to practice KMC. However, there is a dearth of synthesized information on all of the sociocultural, resourcing, and experiential factors that influence a mother's practice of KMC. Accordingly, this review sets out to synthesize existing literature on the factors which influence a mother's ability to practice KMC by answering two questions. First, what are the most frequently cited barriers that could prevent a mother from successfully practicing KMC? These barriers can exist at multiple levels, including barriers to implementation of a KMC program, deficiencies in the program itself, or specific challenges associated with the practice of KMC which the mother has to perform. Second, are there any key positive factors, cited in the relevant literature, that can enable a mother to practice KMC? We believe that it is of utmost importance to consider these different types of barriers together (along with key enablers to practice), even though the solutions for solving each barrier might be different. Even though the specific barriers most relevant for mothers may vary based on context, a comprehensive list of this type will give program implementers, policymakers, and researchers a synthesized set of factors to consider as they attempt to implement new or improve existing KMC programs.

Methodology

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We undertook a systematic review according to PRISMA 2009 guidelines to answer these two questions [ 23 ]. (See S1 Appendix for complete PRISMA checklist). We developed a review protocol with methods and eligibility criteria that were specified in advance. We included any publication in our study that met the following criteria: 1) the aim of the study was to document experiences implementing KMC, STS, or other interventions related to Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, & Child Health and Nutrition (RMNCH&N) that may have included KMC / STS, or the publication had relevant information on specific barriers to implementation listed in the abstract; 2) the study was published in a peer-reviewed journal; 3) the study included data on the sample population, sample size, and location of implementation; 4) the study was original research; and 5) the study was published in English. Studies testing the efficacy of KMC or STS practice (e.g. randomized controlled trials) were included if issues of acceptability, feasibility, or barriers to practice for parents or practitioners were documented in the abstract. Any publication published before August 13, 2013 (the date of the final database search) was eligible for inclusion. We excluded literature reviews, conference proceedings, letters to the editor, and abstracts in order to prevent double counting of data and to ensure that all barriers were understood in the context of the entire study.

We searched nine electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, and the WHO Regional Databases (AIM, LILACS, IMEMR, IMSEAR, and WPRIM). We searched all databases using the following search terms: "Kangaroo Mother Care" OR "Kangaroo Care" OR "Skin to skin care". In addition, because at least one relevant article identified from a list of references in a literature review included the terms Kangaroo Mother Care in quotations and the term Skin to skin, we also searched PubMed for "'Kangaroo Mother Care'" and "Skin to skin". We used broad search criteria to ensure that relevant articles were not missed, and we then filtered and excluded many articles based on the eligibility criteria mentioned above. Reference lists from literature reviews identified in the database search were also scanned for relevant titles, and articles were also identified in consultation with the authors on this study. Recommendations for studies to be included in the review were also received from participants at the KMC Acceleration Meeting in Istanbul, October 2013[ 24 ] and in consultation with leaders in the fields of KMC and newborn health.

Data collection

After our initial database search and identification of additional studies through recommendations and scans of reference lists, study titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers (GS and EK) for inclusion. In situations when a study's eligibility was disputed, a third reviewer (SU) provided an independent assessment until consensus was reached.

96 articles were reviewed to identify a comprehensive list of barriers to KMC practice in advance of the KMC Acceleration Convening [ 24 ]. A data extraction sheet was piloted and tested using these 96 articles. This piloting allowed for preliminary identification of relevant barriers and enablers to be included in the final review as well as final determination of stakeholders to be included in the review: mothers, fathers, community health workers, nurses, physicians, and program managers. The final tool included fields for collecting publication details, relevant study characteristics (sample size, location, and a short description of each study), barriers for each stakeholder group, and enablers to practice for mothers. Results from the preliminary analysis were shared at the KMC Acceleration Convening, ensuring that key stakeholders in the KMC community generally supported the methodology (described in further detail in the next section) and found the preliminary results to be consistent with their experiences [ 24 ]. This convening included researchers and practitioners from many different low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) across Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia, as well as major foundations and civil society organizations involved in RMNCH&N

Once the tool and list of studies was finalized, data was captured from each article into the tool independently by two reviewers (GS and EK) and a third reviewer (SU) provided independent assessment in case of disputes. The main outcome of interest was the frequency with which a barrier / enabler was mentioned across publications. Using frequency of mention allowed for a synthesized view of the barriers / enablers to practice listed in the relevant literature. The data collection process involved identifying barriers and enablers of KMC practice listed in each study (either through qualitative or quantitative findings) and categorizing them into one of the pre-determined categories of barriers / enablers in the tool. There was no limit to the number of barriers / enablers that could be found in a single study, but each study could only count toward a given barrier / enabler once. For example, if a study mentioned several statistics all indicating that mothers' low awareness of KMC was a barrier to practice, this would be coded as a single instance of low awareness among mothers in the tool. In cases where a barrier or enabler was listed for parents in general and did not distinguish between mothers and fathers, this barrier was listed as a barrier for mothers. In cases where a barrier was listed for both nurses and physicians but did not distinguish between the two, this barrier was listed as a barrier for nurses. Barriers / enablers were grouped into three different categories—resourcing, experiential, and sociocultural—based on consensus among all authors. Definitions for these three categories are included in S2 Appendix .

Risk of bias and publication weighting methodology

The goal of this study was to synthesize existing literature on barriers to and enablers of KMC practice. As noted, there is limited systematically organized information on this topic. Therefore, in order to ensure that our review captured as many relevant qualitative and quantitative findings as possible, we chose to include any study identified through our search strategy which had information on barriers and enablers to KMC practice, even if studying this topic was not the primary purpose of the publication.