Consumer-driven e-commerce: A literature review, design framework, and research agenda on last-mile logistics models

International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management

ISSN : 0960-0035

Article publication date: 14 March 2018

Issue publication date: 22 March 2018

The purpose of this paper is to re-examine the extant research on last-mile logistics (LML) models and consider LML’s diverse roots in city logistics, home delivery and business-to-consumer distribution, and more recent developments within the e-commerce digital supply chain context. The review offers a structured approach to what is currently a disparate and fractured field in logistics.

Design/methodology/approach

The systematic literature review examines the interface between e-commerce and LML. Following a protocol-driven methodology, combined with a “snowballing” technique, a total of 47 articles form the basis of the review.

The literature analysis conceptualises the relationship between a broad set of contingency variables and operational characteristics of LML configuration (push-centric, pull-centric, and hybrid system) via a set of structural variables, which are captured in the form of a design framework. The authors propose four future research areas reflecting likely digital supply chain evolutions.

Research limitations/implications

To circumvent subjective selection of articles for inclusion, all papers were assessed independently by two researchers and counterchecked with two independent logistics experts. Resulting classifications inform the development of future LML models.

Practical implications

The design framework of this study provides practitioners insights on key contingency and structural variables and their interrelationships, as well as viable configuration options within given boundary conditions. The reformulated knowledge allows these prescriptive models to inform practitioners in their design of last-mile distribution.

Social implications

Improved LML performance would have positive societal impacts in terms of service and resource efficiency.

Originality/value

This paper provides the first comprehensive review on LML models in the modern e-commerce context. It synthesises knowledge of LML models and provides insights on current trends and future research directions.

- Literature review

- Omnichannel

- Digital supply chains

Lim, S.F.W.T. , Jin, X. and Srai, J.S. (2018), "Consumer-driven e-commerce: A literature review, design framework, and research agenda on last-mile logistics models", International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 48 No. 3, pp. 308-332. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2017-0081

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Stanley Frederick W.T. Lim, Xin Jin and Jagjit Singh Srai

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Last-mile delivery has become a critical source for market differentiation, motivating retailers to invest in a myriad of consumer delivery innovations, such as buy-online-pickup-in-store, autonomous delivery solutions, lockers, and free delivery upon minimum purchase levels ( Lim et al. , 2017 ). Consumers care about last-mile delivery because it offers convenience and flexibility. For these reasons, same-day and on-demand delivery services are gaining traction for groceries (e.g. Deliv Fresh, Instacart), pre-prepared meals (e.g. Sun Basket), and retail purchases (e.g. Dropoff, Amazon Prime Now) ( Lopez, 2017 ). To meet customer needs, parcel carriers are increasing investments into urban and automated distribution hubs ( McKevitt, 2017 ). However, there is a lack of understanding as to how best to design last-mile delivery models with retailers turning to experimentations that, at times, attract scepticism from industry observers (e.g. Cassidy, 2017 ). For example, Sainsbury’s, Somerfield, and Asda established innovative pick centres, but closed them down within a few years ( Fernie et al. , 2010 ). eBay launched its eBay Now same-day delivery service in 2012, but in July 2015, it announced the closure of this programme. Google, likewise, opened and then closed its two delivery hubs for Google Express in 2013 and 2015, respectively ( O’Brien, 2015 ).

The development of these experimental last-mile logistics (LML) models, not surprisingly, created uncertainty within increasingly complicated and fragmented distribution networks. Without sustainable delivery economics, last-mile service provision will struggle to survive (as was the experience of Sainsbury’s, Somerfield, Asda, eBay, Google, and Webvan) with retailers increasingly challenged to find an optimal balance between pricing, consumer expectations for innovative new channels, and service levels ( Lopez, 2017 ; McKevitt, 2017 ).

Although several contributions have been made in the LML domain, the literature on LML models remains relatively fragmented, thus hindering a comprehensive and holistic understanding of the topic to direct research efforts. Hitherto, existing studies provide limited or no guidance on how contingency variables influence the selection of LML configurations ( Agatz et al. , 2008 ; Fernie et al. , 2010 ; Mangiaracina et al. , 2015 ; Lagorio et al. , 2016 ; Savelsbergh and Van Woensel, 2016 ). Our paper addresses this knowledge deficiency by reviewing the disparate academic literature to capture key contingency and structural variables characterizing the different forms of last-mile distribution. We then theoretically establish the connection between these variables thereby providing a design framework for LML models. Our corpus is comprised of 47 papers published in 16 selected peer-reviewed journals during the period from 2000 to 2017. The review is performed from the standpoint of retailers operating LML. As such, some LML research streams are deliberately excluded, including issues related to public policy, urban traffic regulations, logistics infrastructure, urban sustainability, and environment.

This paper is structured as follows. First, we provide a working definition for LML and introduce relevant terms. Second, we set out the research methodology and conduct descriptive analyses of the corpus. The substantive part of the paper is an analysis of the literature on LML models and the development of a design framework for LML. The framework synthesises a set of structural and contingency variables and explicates their interrelationships, shedding light on how these interactions influence LML design. Finally, we highlight the key gaps in the extant literature and propose future research opportunities.

Defining LML

The term “last-mile” originated in the telecommunications industry and refers to the final leg of a network. Today, LML denotes the last segment of a delivery process, which is often regarded as the most expensive, least efficient aspect of a supply chain and with the most pressing environmental concerns ( Gevaers et al. , 2011 ). Early definitions of LML were narrowly stated as the “extension of supply chains directly to the end consumer”; that is, a home delivery service for consumers ( Punakivi et al. , 2001 ; Kull et al. , 2007 ). Several synonyms, such as last-mile supply chain, last-mile, final-mile, home delivery, business-to-consumer distribution, and grocery delivery, have also been used.

Despite their nuances, existing LML definitions converge on a common understanding that refers to the last part of a delivery process. However, existing definitions (details available from the authors) appear incomplete in capturing the complexities driven by e-commerce, such as omission in defining an origin ( Esper et al. , 2003 ; Kull et al. , 2007 ; Gevaers et al. , 2011 ; Ehmke and Mattfeld, 2012 ; Dablanc et al. , 2013 ; Harrington et al. , 2016 ); exclusion of in-store order fulfilment processes as a fulfilment option ( Hübner, Kuhn and Wollenburg, 2016 ); and/or non-specification of the destination (or end point), including failure to capture the collection delivery point (CDP) as a reception option ( Esper et al. , 2003 ; Kull et al. , 2007 ). Without a consistent and robust definition of LML, the design of LML models is problematic.

For the purpose of this review, we examine existing terminology on last-mile delivery systems in order to create a working definition for LML. As part of this definition, we introduce the concept of an “order penetration point” ( Fernie and Sparks, 2009 ) as a way of defining the origin of the last-mile. The order penetration point refers to an inventory location (e.g. fulfilment centre, manufacturer site, or retail store) where a fulfilment process is activated by a consumer order. After this point, products are uniquely assigned to the consumers who ordered them, making the order penetration point a natural starting point for LML. The destination point is commonly dictated by the consumer, hence we use “final consignee’s preferred destination point” as the terminology to indicate where an order is delivered. The choice of destination point could be a home/office, a reception box (RB), or a pre-designated CDP.

Last-mile logistics is the last stretch of a business-to-consumer (B2C) parcel delivery service. It takes place from the order penetration point to the final consignee’s preferred destination point.

Extending the above definition, we reference Bowersox et al. ’s (2012) view of a supply chain as a series of “cycles”, with half the cycle being the product/order flow and the other, information flow. We also reference the Supply Chain Operations Reference model ( Supply Chain Council, 2010 ) recognising that LML operates within a broader supply network. In particular, the LML cycle coincides with the consumer service cycle, interfacing direct-to-consumer-goods manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers with the end consumer ( Bowersox et al. , 2012 ). The process may be divided into three sub-processes, namely source, make, and deliver.

These three sub-processes set the focus for this review and they align with the delivery order phase in LML, namely picking, packing, and delivery. This model is consistent with Campbell and Savelsbergh’s (2005) view of the business-to-consumer process comprising order sourcing, order assembly, and order delivery. Accordingly, this review focuses on the examination of LML models: LML distribution structures and the contingency variables associated with these structures. The term “distribution structure” covers the stages from order fulfilment to delivery to the final consignee’s preferred destination point. It includes the modes of picking (e.g. warehouse or store-based), transportation (e.g. direct delivery by the retailer’s own fleet), and reception (e.g. consumer-pickup) ( Kämäräinen et al. , 2001 ). The associated contingency variables provide guidance for decision support by highlighting the key characteristics of each distribution structure for the design and selection, matching product, and consumer attributes ( Boyer and Hult, 2005 ).

Research methodology

A structured literature review aims to identify the conceptual content of a rapidly growing field of knowledge, as well as to provide guidance on theory development and future research direction ( Meredith, 1993 ; Easterby-Smith et al. , 2002 ; Rousseau et al. , 2008 ). Structured reviews differ from more narrative-based reviews because of the requirement to provide a detailed description of the review procedure in order to reduce bias; this requirement thereby increases transparency and replicability ( Tranfield et al. , 2003 ). Therefore, undertaking a structured review ensures the fidelity, completeness, and rigour of the review itself ( Greenhalgh and Peacock, 2005 ).

Our review provides a snapshot of the diversity of theoretical approaches present in LML literature. It does not pretend to cover the entirety of the literature, but rather offers an informative and focused evaluation of purposefully selected literature to answer specific research questions. In the following sections, we discuss the execution of the four main steps (planning, searching, screening, and extraction/synthesis/reporting) as outlined by Tranfield et al. (2003) . We also incorporate literature review guidelines suggested by Saenz and Koufteros (2015) . Our study uses key research questions identified by an expert panel and we reference the Association of Business Schools journal ranking 2015 to decide which journals to include in this scholarship ( Cremer et al. , 2015 ). Our review includes the classification of contributions across methodological domains. In later sections, we utilise insights from the literature review to develop an LML design framework that captures the relationships between distribution structures via a set of structural and associated contingency variables.

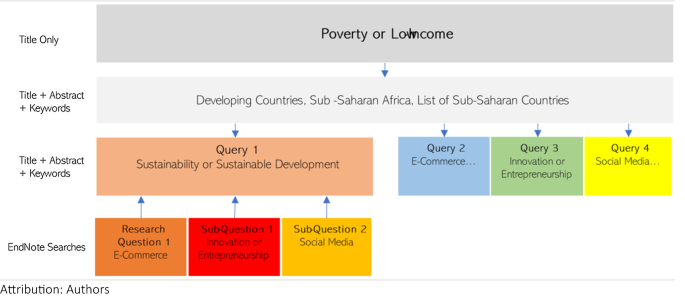

What is the current state of research and practice on LML distribution in the e-commerce context?

What are the associated contingency variables that can influence the selection of LML distribution structures?

How can the contingency variables identified in RQ2 be used to inform the selection of LML distribution structures?

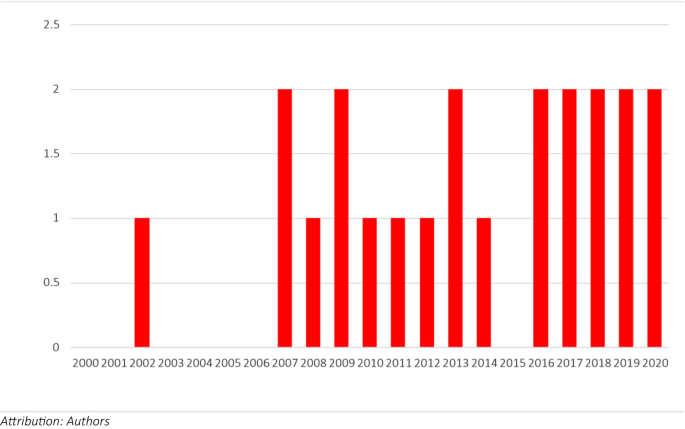

The academic material in this study covers the period from 2000 to 2017. This period coincides with critical industry events, such as the emergence and subsequent demise of the online grocer, Webvan. The review is limited to peer-reviewed publications to ensure the quality of the corpus ( Saenz and Koufteros, 2015 ) and considers 16 journals, including one practitioner journal ( MIT Sloan Management Review ), to capture theoretical perspectives on industry best practices. Only articles from the selected journals have been included in this review, with one exception, where we included the article by Wang et al. (2014) , published in Mathematical Problems in Engineering . The article was deemed critical as it represents the only piece of work to date that connects and extends prior research on the evaluation of CDPs.

The 16 journals were selected based on their primary focus on empirical and conceptual development, rather than on their discussion of analytical modelling. Although we appreciate that there are significant research studies in this area (e.g. operations research), the focus of this review led us to primarily consider how scholars conceptualise LML distribution structures and apply theoretical variables to LML design through quantitative, qualitative, or conceptual approaches, rather than through mathematic-based models. The mathematic-based model literature focuses on the development of stylised and optimisation models in areas of multi-echelon distribution systems, vehicle routing problems ( Savelsbergh and Van Woensel, 2016 ), buy-online-pick-up-in-store services ( Gao and Su, 2017 ), pricing and delivery choice, inventory-pricing, delivery service levels, discrete location-allocation, channel design, and optimal order quantities via newsvendor formulation for different fulfilment options ( Agatz et al. , 2008 ), amongst others. These studies typically employ a series of assumptions to simplify real-world operations in order to provide closed-form or heuristic-based prescriptive solutions ( Agatz et al. , 2008 ; Savelsbergh and Van Woensel, 2016 ). Therefore, this review excluded journals with a primarily mathematical modelling or operations research focus. However, it included relevant mathematical modelling articles – published in any of the 16 selected journals – as long as they explicated types of LML distribution structure and/or the associated contingency variables. Finally, this study also excluded general management journals in order to fit the operational focus of this research.

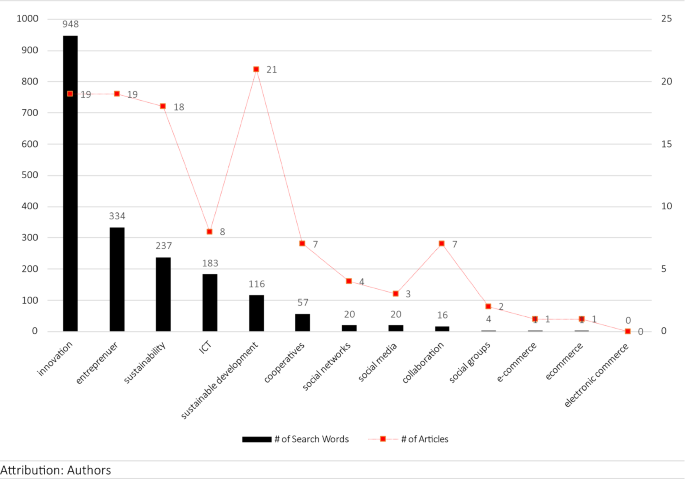

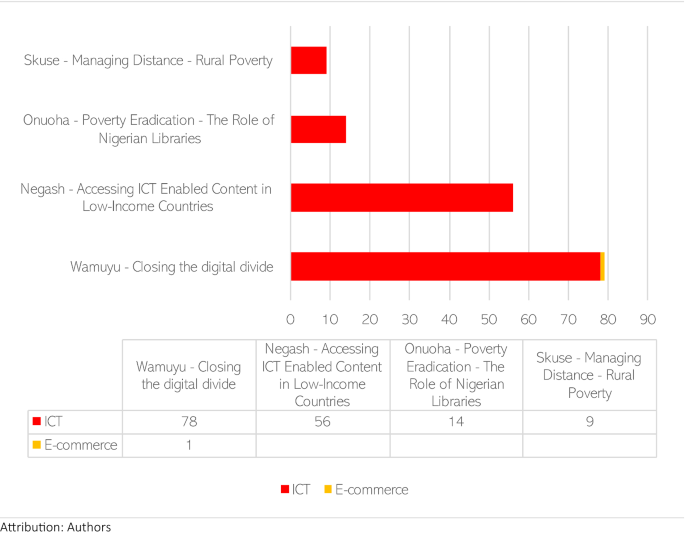

The literature search was conducted on the following databases: ISI Web of Science, Science Direct, Scopus, and ABI/Inform Global. Two search rounds were undertaken to maximise inclusion of all relevant articles. The first literature probe was performed using the following search terms: “urban logistics” OR “city logistics” OR “last-mile logistics” OR “last mile logistics”. To extend the corpus, we incorporated the “snowballing” technique of tracing citations backward and forward to locate leads to other related articles; this study used this process in the second round to supplement a protocol-driven methodology. This approach resulted in new search terms and scholar identification to refine the search strategy as the study unfolded ( Greenhalgh and Peacock, 2005 ). The following new search terms were identified: “home delivery”, “B2C distribution”, “extended supply chain”, “final mile”, “distribution network”, “distribution structure”, and “grocery delivery”. These new keywords were then used to create additional search strings with Boolean connectors (AND, OR, AND NOT). Finally, in order to cross-check the searches, we consulted with a supply chain professor from Arizona State University and one from the University of Cambridge. It is therefore posited that the review coverage is reasonably comprehensive.

Exclusion criteria: paper titles bearing the terms “urban logistics”, “city logistics”, “last-mile logistics”, or “last-mile” but with limited coverage on distribution structures and the associated design variables were excluded (e.g. public policy, urban traffic regulations, logistics infrastructure, urban sustainability, environment), as were editorial opinions, conference proceedings, textbooks, book reviews, dissertations, and unpublished working papers.

Inclusion criteria: papers with coverage of distribution structures and design variables in the e-commerce context were included, regardless of their actual study focus. We included multiple research methods to have both established findings as well as emergent theorising.

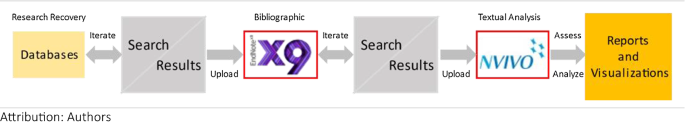

During the search phase, we identified 425 articles referencing our subject terms. We eliminated duplicates based on titles and name of authors and rejected articles matching the exclusion criteria. For example, while the paper by Gary et al. (2015) holds the keyword “urban logistics” in the title, it focuses on logistics prototyping, rather than LML models, as a method to engage stakeholders. This paper, therefore, was excluded. The elimination stage resulted in 100 articles being considered relevant for further review. Results were exported to reference management software, EndNote version X8, for further review and to facilitate data management. We then adopted the inclusion criteria to select the final articles. Finally, we grouped the articles into two categories: LML distribution structures and the associated contingency variables. Ultimately, a total of 47 journal articles form the corpus of this review.

Extraction, synthesis, and reporting

Following an initial review of the 47 articles, a summary of each article was prepared using a spreadsheet format organised under descriptive (year, journal, title), methodology (article type, theoretical lens, sampling protocol), and thematic categories (article purpose, context, LML distribution structures, design variables, others) as adapted from Pilbeam et al. (2012) .

Accordingly, we conducted three analyses: descriptive, methodological, and thematic ( Richard and Beverly, 2014 ). The descriptive analysis summarises the research development over the period of interest, and the distribution statistics of the journals. The methodological analysis highlights the research methods employed in the domain, while the thematic analysis synthesises the main outcomes from the extracted literature and provides an overview of the review structure. Reporting structures were organised in a manner that sequentially responds to the research questions posed earlier.

Descriptive analysis

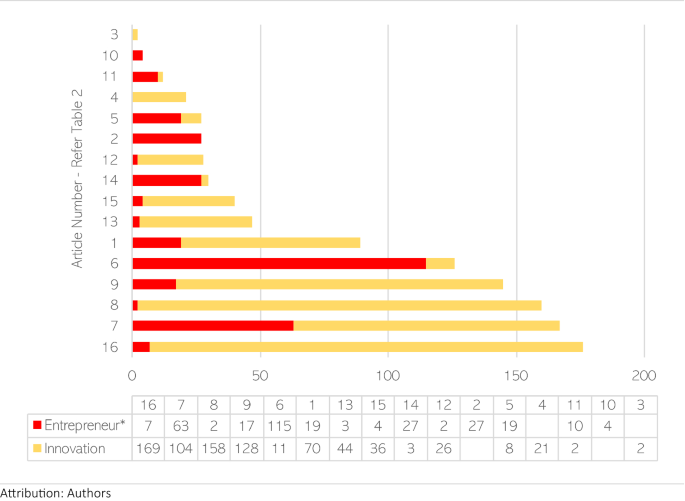

Table I provides summary statistics of the papers reviewed, author affiliations c , identifying contributions, as well as those journals where surprisingly contributions have yet to be made.

Methodological analysis

Typology-oriented provision: owing to the recent proliferation of LML models, a typology-oriented approach was particularly conducive for understanding LML practices. Lee and Whang (2001) , Chopra (2003) , Boyer and Hult (2005) , and Vanelslander et al. (2013) each developed LML structural types to assist design under different consumer and product attributes. These studies mostly captured the linearly “chain-centric” LML models prevalent in the pre-digital era.

Literature review and conceptual studies: several reviews have contributed in this domain. Some papers focused on specific areas, such as the evolution of British retailing ( Fernie et al. , 2010 ) and distribution network design ( Mangiaracina et al. , 2015 ), whereas others discussed several topics at once ( Agatz et al. , 2008 ; Lagorio et al. , 2016 ; Savelsbergh and Van Woensel, 2016 ). Narrowly focused papers identified limited LML structural types or variables influencing distribution network design, while more broadly focused papers examined wider issues in urban, city, or multichannel logistics. Conceptual studies typically provided guidance on the selection of LML “types” based on certain performance criteria (e.g. Punakivi and Saranen, 2001 ; Chopra, 2003 ), or logistics service quality (e.g. Yuan and David, 2006 ).

Empirical studies: these studies mainly compared LML types or demonstrated the impact of particular variables upon LML. Studies undertaking the former research purpose (contrasting types) employed simulations, field/mail surveys, and econometrics to examine performance or CO 2 emissions (e.g. Punakivi et al. , 2001 ). One paper employed a mixed-method approach (case research and modelling) to understand the organisation of the physical distribution processes in omnichannel supply networks ( Ishfaq et al. , 2016 ). Empirical studies aiming at the latter research purpose (evidencing impact) used field and laboratory experiments and statistical methods on survey data to examine the interplay between operational strategies and consumer behaviour (e.g. Esper et al. , 2003 ; Boyer and Hult, 2005 ; Kull et al. , 2007 ). These studies also employed econometrics to examine the effects of cross-channel interventions (e.g. Forman et al. , 2009 ; Gallino and Moreno, 2014 ). Additionally, a few studies used case research to provide operational guidance via framework development, such as last-mile order fulfilment ( Hübner, Kuhn and Wollenburg, 2016 ) and LML design, to capture the interests of various stakeholders ( Harrington et al. , 2016 ).

Mathematical modelling: studies also employed a variety of mathematical tools and techniques to formulate LML problems and find optimum solutions, mostly for vehicle routing problems ( Campbell and Savelsbergh, 2005 ; McLeod et al. , 2006 ; Aksen and Altinkemer, 2008 ; Crainic et al. , 2009 ; Wang et al. , 2014 ). In their work, Campbell and Savelsbergh (2006) combined optimisation modelling with simulation to demonstrate the value of incentives. Other studies focused on identifying optimum distribution strategies (e.g. Netessine and Rudi, 2006 ; Li et al. , 2015 ), inventory rationing policy ( Ayanso et al. , 2006 ), delivery time slot pricing ( Yang and Strauss, 2017 ), and formulating new models to capture emerging practices, such as crowd-sourced delivery ( Wang et al. , 2016 ).

Thematic analysis

The grounded theory approach ( Glasser and Strauss, 1967 ) was used to code and classify emerging repeated concepts and terminologies via the qualitative data analysis software, MAXQDA version 12. The classification was based on the two categories defining LML models: LML distribution structures and their associated contingency variables. Coding of the data was conducted independently by two authors. The distinguishing terms and concepts were documented in a codebook; where their views differed, the issues were discussed until consensus was reached. Terminologies relating to each classification level were either derived from the extant literature or introduced in this paper to unify key concepts.

For the first category, the types of LML distribution structure are classified based on different levels of effort required by vendor and consumer: push-centric, pull-centric, and hybrid. A push-centric system requires the vendor to wholly undertake the distribution functions required to deliver the ordered product(s) to the consumer’s doorstep; a pull-centric system requires the consumer to wholly undertake the collection and transporting function; and a hybrid system requires some effort on the parts of both the vendor and consumer and is varied by the location of the decoupling point. A further breakdown divided the push-centric distribution system into modes of picking (manufacturer-based, distribution centre (DC)-based, and local brick-and-mortar (B&M) store-based); the pull-centric distribution system was divided into modes of collection from fulfilment point (local B&M store and information store); and the hybrid distribution system was divided into modes of CDP (attended collection delivery point (CDP-A) and unattended collection delivery point (CDP-U)).

The second category captures the associated contingency variables commonly used in existing studies. This study created a list of 13 variables that influence the structural forms of last-mile distribution: consumer geographical density, consumer physical convenience, consumer time convenience, demand volume, order response time, order visibility, product availability, product variety, product customisability, product freshness, product margin, product returnability, and service capacity. These variables determine the manner in which, or the efficiency with which, a distribution structure fulfils consumer needs while relating to the idiosyncrasies of product types.

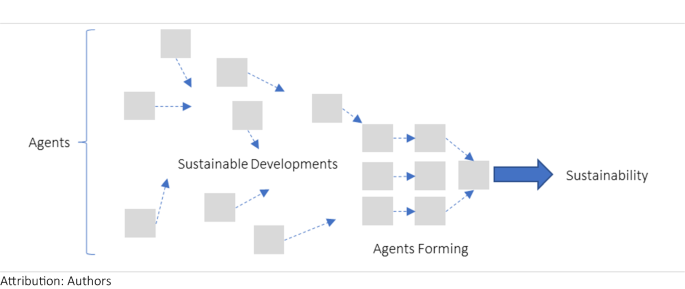

These classifications facilitate the understanding of LML models and enabled future structural variables to be consistently categorised. Figure 1 serves to present a structural overview of the LML models reported in the literature.

Review of LML distribution structures

push: product “sent” to consumer’s postcode by someone other than the consumer;

pull: product “fetched” from product source by the consumer; and

hybrid: product “sent” to an intermediate site, from which the product is “fetched” by the consumer.

Table II summarises the corpus on LML distribution structures.

Push-centric system: n -tier direct to home

This study found that the push-centric system is the most commonly adopted distribution form. It typically comprises a number of intermediate stages ( n -tier) between the source and destination in order to create distribution efficiencies. The literature classifies three picking variants according to fulfilment (inventory) location: manufacturer-based (or “drop-shipping”), DC-based, or local B&M store-based (i.e. retailer’s intermediate warehouse or store). The destination can either be consumers’ homes or, increasingly, their workplaces ( McKinnon and Tallam, 2003 ). The mode of delivery can be in-sourced (using retailer’s own vehicle fleet), outsourced to a third-party logistics provider (3PL) ( Boyer and Hult, 2005 ), or crowd-sourced using independent contractors ( Wang et al. , 2016 ).

When selecting a distribution channel, retailers need to trade-off between fulfilment capabilities, inventory levels ( Netessine and Rudi, 2006 ), product availability and variety ( Agatz et al. , 2008 ), transportation cost ( Rabinovich et al. , 2008 ), and responsiveness ( Chopra, 2003 ). The nearer the picking site is to the consumer segment, the more responsive is the channel. However, this responsiveness comes at the expense of lower-level inventory aggregation and higher risks associated with stock-outs ( Netessine and Rudi, 2006 ).

Pull-centric system: consumer self-help

The literature also discussed two variants of the pull-centric system. Both variants require consumers to participate (or self-help) throughout the transaction process, from order fulfilment to order transportation. The first variant represents the traditional way of shopping at a local B&M store, with consumers performing the last-mile “delivery”. The second “information store” variant adopts a concept known as “dematerialisation”, substituting information flow for material flow ( Lee and Whang, 2001 ). This variant recognises that material or physical flows are typically more expensive than information flows due to the costs of (un)loading, handling, warehousing, shipping, and product returns.

This study found that despite the popularity of online shopping, there are still occasions where consumers favour traditional offline shopping. Perceived or actual difficulties with inspecting non-digital products, the product returns process, or slow and expensive shipping can deter consumers from online shopping ( Forman et al. , 2009 ). This study also demonstrates other benefits of a pull-centric system, including lower capital investments and possible carry-over (or halo) effects into in-store sales ( Johnson and Whang, 2002 ).

Hybrid system: n -tier to consumer self-help location

The rich literature here mainly compared different modes of reception. Variants typically entailed a part-push and part-pull configuration. For instance, the problem associated with “not-at-home” responses within attended home delivery (AHD) can be mitigated by delivering the product to a CDP for consumers to pick up. The literature discussed two CDP variants: CDP-A and CDP-U. It found that retailers establish CDP-A through developing new infrastructure development, through utilising existing facilities, or establishing partnerships with a third party ( Wang et al. , 2014 ). Other terminologies associated with CDP-A include “click-and-collect”, “pickup centre”, “click-and-mortar”, and “buy-online-pickup-in-store”. The literature showed that retailers establish CDP-U (or unattended reception) through independent RBs equipped with a docking mechanism, or shared RBs, whose locations range from private homes to public sites (e.g. petrol kiosks and train stations) accessible by multiple users ( McLeod et al. , 2006 ).

These CDP-A and CDP-U strategies are commonly adopted by multi/omnichannel retailers to exploit their existing store networks, to provide convenience to consumers through ancillary delivery services, and to expedite returns handling ( Yrjölä, 2001 ). Moreover, the research showed that integrating online technologies with physical infrastructures enables retailers to achieve synergies in cost savings, improved brand differentiation, enhanced consumer trust, and market extension ( Fernie et al. , 2010 ). Studies have also investigated the cost advantage and operational efficiencies of using CDP-U over AHD and CDP-A (e.g. Wang et al. , 2014 ). CDP-U reduces home delivery costs by up to 60 per cent ( Punakivi et al. , 2001 ), primarily by exploiting time window benefit ( Kämäräinen et al. , 2001 ).

Development of LML design framework

This section addresses the second and third research questions by developing a framework that contributes to LML design practice. The development process is governed by contingency theory ( Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967 ), in which “fit” is a central concept. The contingency theory maintains that structural, contextual, and environmental variables should fit with one another to produce organisational effectiveness. The management literature conceptualises fit as profile deviation (e.g. Jauch and Osborn, 1981 ; Doty et al. , 1993 ) in terms of the degree of consistency across multiple dimensions of organisational design and context. The probability of organisational effectiveness increases as the fit between the different types of variables increases ( Jauch and Osborn, 1981 ; Doty et al. , 1993 ). In this paper, the environmental and contextual variables are jointly branded as contingency variables since the object was to examine how these variables impact the structural form of LML distribution.

We developed the LML design framework in two steps. First, we synthesised a set of LML structural and contingency variables and established the relationship between these through a review of the LML literature. Second, we reformulated the descriptive (i.e. science-mode) knowledge obtained via the first step into prescriptive (i.e. design-mode) knowledge. We adopted the contingency perspective in combination with Romme’s (2003) approach to inform knowledge reformulation.

Synthesising LML structural variables

Product source refers to the location where products are stored when an order is accepted; it coincides with the start point of an LML network. It can be contextualised as a supply network member entity (manufacturer, distributor, or retailer). To illustrate, the computer manufacturer Dell (customisation services), online grocer Ocado (home delivery services), and the UK’s leading supermarket chain Tesco (click-and-collect services) source their products from manufacturer, distributor, and retailer sites, respectively.

Geographical scope concerns the distance separating the start point (product source) and the end point (final consignee’s preferred destination point) of an LML network. An LML network can be classified as centrally based (e.g. Dell Services) or locally based (e.g. Tesco’s click-and-collect).

Mode of distribution describes the delivery mode from the point where an order is fully fulfilled to the end point; it can be classified into three types: self-delivery (e.g. Tesco’s self-owned fleet for home deliveries), 3PL delivery including crowdsourcing (e.g. Dell Services), and consumer-pickup (e.g. Tesco’s click-and-collect services).

Number of nodes concerns the operations in which products are “stationary”, residing in a facility for processing or storage. As opposed to nodes, links represent movements between nodes. There are two variations in respect to this variable: two-node and multiple-node. For example, a two-node structure can be found in Dell’s direct-to-consumer distribution channel, where computers are assembled and orders fulfilled at the factory prior to direct home delivery. In contrast, multiple-node structures are reflected in “in-transit merge” structure where an order comprising components sourced from multiple locations are assembled at a common node. As a case in point, when consumer order a computer processing unit (CPU) from Dell along with a Sony monitor, a parcel carrier would pick up the CPU from a Dell factory and the monitor from a Sony factory, then would merge the two into a single shipment at a hub prior to delivery ( Chopra, 2003 ).

Synthesising LML contingency variables

Consumer geographical density: the number of consumers per unit area ( Boyer and Hult, 2005 ; Boyer et al. , 2009 ; Mangiaracina et al. , 2015 ).

Consumer physical convenience: the effort consumers exert to receive orders ( Chopra, 2003 ; Harrington et al. , 2016 ).

Consumer time convenience: the time committed by consumers for the reception of orders. This variable fluctuates according to the structural form of last-mile distribution ( Rabinovich and Bailey, 2004 ; Yuan and David, 2006).

Demand volume: the number of products ordered by consumers relative to the distribution structure ( Chopra, 2003 ; Boyer and Hult, 2005 ).

Order response time: the time difference between order placement and order delivery ( Kämäräinen et al. , 2001 ; Mangiaracina et al. , 2015 ).

Order visibility: the ability of consumers to track their order from placement to delivery ( Chopra, 2003 ; Harrington et al. , 2016 ).

Product availability and product variety: product availability is the probability of having products in stock when a consumer order arrives ( Chopra, 2003 ; Yuan and David, 2006).

Product variety is the number of unique products (or stock keeping units) offered to consumers ( Punakivi et al. , 2001 ; Punakivi and Saranen, 2001 ).

Product customisability: the ability for products to be adapted to consumer specifications ( Boyer and Hult, 2005 ).

Product freshness: the time elapsed from the moment a product is fully manufactured to the moment when it arrives at the consumption point ( Boyer and Hult, 2005 ).

Product margin: the net income divided by revenue ( Boyer and Hult, 2005 ; Campbell and Savelsbergh, 2005 ).

Product returnability: the ease with which consumers can return unsatisfactory products ( Chopra, 2003 ; Yuan and David, 2006).

Service capacity: the ability of an LML system to provide the intended delivery service and to match consumer demand at any given point in time ( Rabinovich and Bailey, 2004 ; Yuan and David, 2006).

Synthesising the relationship between LML structural and contingency variables

Firms that target customers who can tolerate a large response time require few locations that may be far from the customer and can focus on increasing the capacity of each location. On the other hand, firms that target customers who value short response times need to locate close to them.

This statement identifies the association between a structural variable, namely “geographical scope”, and a contingency variable, namely “order response time”. Within the literature, two variations emerged for each variable: centralised vs localised network for geographical scope and long vs short delivery period for order response time; i.e. centralised geographical scope corresponds to long response time, while localised scope is more responsive. As such, the findings demonstrate that by identifying connecting rationales and the variations at different levels for each variable, we can capture correlations between two sets of variables (i.e. structural and contingency). Continuing this procedure across relevant statements found in our corpus, Table IV summarises the outputs.

Reformulation from science-mode into design-mode knowledge

We adopted the approach by Romme (2003) to reformulate the descriptive knowledge (i.e. science-mode, developed in the previous section) into prescriptive (i.e. design-mode) knowledge so that the latter becomes more accessible to guide practitioners in their LML design thinking. This approach has previously been used to contextualise various design scenarios (e.g. Zott and Amit, 2007 ; Holloway et al. , 2016 ; Busse et al. , 2017 ). For example, Busse et al. (2017) employed a variant of the approach to investigate how buying firms facing low supply chain visibility can utilise their stakeholder network to identify salient supply chain sustainability risks.

if necessary, redefine descriptive (properties of) variables into imperative ones (e.g. actions to be taken);

redefine the probabilistic nature of a hypothesis into an action-oriented design proposition;

add any missing context-specific conditions and variables (drawing on other research findings obtained in science- or design-mode); and

in case of any interdependencies between hypotheses/propositions, formulate a set of propositions.

[If order response time delivered by an LML network is short, then the geographical scope of the LML network should be localised].

[For an LML network to achieve short order response time, localise the geographical scope].

Following similar procedures, the science-mode knowledge describing the relationships between structural and contingency variables can be reformulated to the design-mode shown in Table V . Collectively, the resulting design-mode knowledge constitutes a set of design guidelines for LML practitioners.

Main research issues, gaps, and future lines of research

Although the literature covered in this study thoroughly addresses LML structures, the extant literature has limitations. Based on this study’s findings, there are four main areas that require future study.

Operational challenges in executing last-mile operations

The extant literature has focused on the planning aspect of LML, rather than exploring operational challenges. Consequently, research often takes a simplistic chain-level perspective of LML in order to develop simplistic design prescriptions for practitioners. While this approach seems suitable in the pre-digital era, it is inadequate to capture the complexities of last-mile operations in the omnichannel environment ( Lim et al. , 2017 ). The focus on LML nodes as solely unifunctional is also inadequate ( Vanelslander et al. , 2013 ). Not acknowledging the multi-functionality of individual nodes limits understanding of how this variant works.

To address the limitations of extant research, we propose extending the current research from addressing linear point-to-point LML “chains” (e.g. Chopra, 2003 ; Boyer and Hult, 2005 ) to also addressing the “networks” context, where multiple chains are intertwined and more widely practised in the industry. A study of LML systems using 3PL shared by multiple companies is an example of necessary future research. We also recommend future research to address the multi-functionality of individual nodes in an LML system. A study that addresses the ability of an LML node to simultaneously be a manufacturer and a distributor introduces more structural variance and needs to be theoretically addressed.

Additionally, existing literature typically focuses on comparing structural variants’ performance outcomes and their corresponding consumer and product attributes. However, we argue that such focus limits our understanding of how LML distribution structures interact as part of the broader omnichannel system. Accordingly, an avenue for future research would employ configuration perspectives ( Miller, 1986 ; Lim and Srai, 2018 ) to complement the traditional reductionist approaches (e.g. Boyer et al., 2009 ) in order to more holistically examine LML models. Future studies could consider the structural interactions with relational governance of supply network entities, in order to promote information sharing and enhancing visibility, which are critical in omnichannel retailing ( Lim et al. , 2016 ).

Finally, while recent articles have started to examine the effects of online and offline channel integrations (e.g. Gallino and Moreno, 2014 ), limited contributions have been made to date to understand how retailers integrate their online and offline operations and resources to deliver a seamless experience for consumers ( Piotrowicz and Cuthbertson, 2014 ; Hübner, Kuhn and Wollenburg, 2016 ). We propose revisiting the pull-centric system variants in the context of active consumer participation to understand the approaches retailers can use to attract consumers to their stores. In this regard, the subject can benefit from insightful case studies to advance our understanding of the challenges retailers face, as well as the operational processes retailers adopt to meet these challenges.

Intersection between last-mile operations and “sharing economy” models

With the exception of one paper ( Wang et al. , 2016 ), the majority of the extant literature discusses conventional LML models. Given the rapidly growing sharing economy that generates innovative business models (e.g. Airbnb, Uber, Amazon Prime Now) in several sectors (e.g. housing, transportation, and logistics, respectively) and exploits collaborative consumption ( Hamari et al. , 2016 , p. 2047) and logistics ( Savelsbergh and Van Woensel, 2016 ), there is an immense research scope at the intersection between LML and sharing economy models. First, we propose empirical studies to examine how retailers can effectively employ crowdsourcing models for the last-mile and to show how they can effectively integrate these models into their existing last-mile operations, such as combining in-store fulfilment through delivery using “Uber-type” solutions. This type of study is critical for understanding the impact of crowdsourcing models on retail operations and for promoting their adoption. Second, papers addressing omnichannel issues ( Hübner, Kuhn and Wollenburg, 2016 ; Hübner, Wollenburg and Holzapfel, 2016 ; Ishfaq et al. , 2016 ) are emerging. The emergence of new omnichannel distribution models demands theoretical development and the identification of new design variables. These models include on-demand delivery model (e.g. Instacart), distribution-as-a-service (e.g. Amazon, Ocado), “showroom” concept stores (e.g. Bonobos.com, Warby Parker), in-store digital walls (e.g. Adidas U.S. adiVerse), unmanned delivery (e.g. drones, ground robots), and additive printing (e.g. The UPS store 3D print). Increasingly, we also observe the growing convergence of roles and functions between online and traditional B&M retailers, which suggests new integrated LML models. These new roles and functions demand future research. Finally, while collaborative logistics enable the sharing of assets and capacities in order to increase utilisation and reduce freight, its success rests on developing a logistics ecosystem of relevant stakeholders (including institutions). Consequently, exciting research opportunities exist to explore new design variables that capture key stakeholders’ interests at various levels ( Harrington et al. , 2016 ).

Data harmonisation and analytics: collection and sharing platforms

The literature review revealed that, to date, there has been a tendency towards geographical-based studies and the use of simulated data. For example, this review reports studies based in Finland ( Punakivi and Saranen, 2001 ), Scotland ( McKinnon and Tallam, 2003 ), the USA ( Boyer et al. , 2009 ), England ( McLeod et al. , 2006 ), Germany ( Wollenburg et al. , 2017 ), and Brazil ( Wanke, 2012 ), amongst others. While these studies contribute to generating a useful library of contexts, they are difficult to compare, given differences in geography and geographically based data collection and analysis methods. Moreover, the majority of the studies in this review (41.30 per cent) were based on modelling and simulated data with limited application to real-world data sets, which might suggest a lack of quality data sets. Simulated data limit the advancement of domain knowledge, thus the development of real-world data sets could significantly fuel progress. As such, more attention should be focused on developing data sets, e.g. through the use of transaction and consumer-level data, to gain insights into last-mile behaviours and to design more effective LML models.

Additionally, future studies should standardise data collection in order to address current trends in urbanisation and omnichannel retailing, which are changing retail landscapes and consumer shopping behaviours. This study recommends establishing a data collection framework to guide scholars in LML design, with scholars developing new competences in data mining analytics to exploit large-scale data sets.

Moving from prescriptive to predictive last-mile distribution design

Extant studies have derived correlations between variation of independent variables (e.g. order response time) and variation of dependent variables (e.g. degree of centralisation) to provide prescriptive solutions to the design of last-mile distribution structures. However, these relationships (both linear and non-linear) are often confounded by other factors due to the real-world complexities and they inherently face multicollinearity and endogeneity issues, including the omitted variable bias problem, which leads to biased conclusions. Moreover, model complexity increases as more variables are included, potentially causing overfitting. Given these complexities, researchers usually find immense challenges in untangling these relationships. In this regard, we offer several valuable future lines of research leveraging more advanced techniques for the design of last-mile distribution.

First, our review captured 13 contingency variables that influence the design of last-mile distribution. Future research could discuss other contingency variables and investigate the use of statistical machine and deep learning techniques to identify the most critical contingency variables and uncover hidden relationships to develop predictive models. Second, as urbanisation trends continue, more institutional attention is required on urban logistics focused on negative externalities (congestion and carbon emissions) driven by the intensification of urban freight. According to our review, there is insufficient attention paid to urban freight delivery, and we propose exploring archetyping of urban areas for the development of predictive models to guide the design of urban last-mile distribution systems.

Third, the developed design framework is based on the assumption that only one last-mile distribution structure may be adopted for a given scenario. As we observed in the omnichannel setting, it is common for retailers to concurrently operate multiple distribution structures. The interrelationships between the various structural combinations under the management of a single LML operator also present a potential future research direction.

Last, there is room for a combination of methods to more appropriately tackle the increasingly complicated and fragmented distribution networks in the omnichannel environment. Indeed, this research revealed only two papers in the corpus that have employed a mixed-method approach. Ishfaq et al. (2016) used case research and classification-tree analysis to understand the organisation of distribution processes in omnichannel supply networks, while Campbell and Savelsbergh (2006) combined analytical modelling with simulation to demonstrate the value of incentives in influencing consumer behaviour to reduce delivery costs.

Conclusions

This paper offers the first comprehensive review and analysis of literature regarding e-commerce LML distribution structures and their associated contingency variables. Specifically, the study offers value by using a design framework to explicate the relationship between a broad set of contingency variables and the operational characteristics of LML configuration via a set of structural variables with clearly defined boundaries. The connection between contingency variables and structural variables is critical for understanding LML configuration choices; without understanding this connection, extant knowledge is non-actionable, leaving practitioners with an overwhelming number of seemingly relevant variables that have vague relationships with the structural forms of last-mile distribution.

From a theoretical contribution perspective, this paper identifies attributes of delivery performance linked to product-market segments and the system dynamics that underpin them. This understanding of the interrelationships between LML dimensions enables us to classify prior work, which is somewhat fragmented, to provide insights on emerging business models. The reclassification of LML structures helps practitioners understand the three dominant system dynamics (push-centric, pull-centric, and hybrid) and their related contingency variables. Synthesising structural and contingency variables, the network design framework ( Table IV ) sets out the connections, which when reformulated ( Table V ), provide practitioners design prescriptions under varying LML contexts.

Accordingly, the literature review demonstrates that push-centric LML models driven by order visibility performance are ideally suited to variety-seeking market segments where consumers prioritise time convenience over physical convenience. Conversely, it shows that pull-centric LML models favour order response time, order visibility, and product returnability performance, which are widely observed in markets where consumers desire high physical convenience, low product customisability, and high product variety. Most interestingly of all, this study explains the emergent hybrid systems, where service capacity performance excellence is delivered through multiple clusters of contingency variables, which suits availability-sensitive markets and markets where consumers prioritise physical (over time) convenience.

This paper identifies four areas for further research: operational challenges in executing last-mile operations; intersection between last-mile operations and sharing economy models; data harmonisation and analytics; and moving from prescriptive to predictive last-mile distribution design. Research in these areas could contribute to consolidating the body of knowledge on LML models while maintaining the essential multidisciplinary character. We hope that this review will serve as a foundation to current research efforts, stimulate suggested lines of future research, and assist practitioners to design enhanced LML models in a changing digital e-commerce landscape.

Classification of literature review on LML models

Journal pool for reviewed papers

LML design framework

Aksen , D. and Altinkemer , K. ( 2008 ), “ A location-routing problem for the conversion to the ‘click-and-mortar’ retailing: the static case ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 186 No. 2 , pp. 554 - 575 .

Agatz , N.A.H. , Fleischmann , M. and van Nunen , J.A.E.E. ( 2008 ), “ E-fulfillment and multi-channel distribution – a review ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 187 No. 2 , pp. 339 - 356 .

Ayanso , A. , Diaby , M. and Nair , S.K. ( 2006 ), “ Inventory rationing via drop-shipping in Internet retailing: a sensitivity analysis ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 171 No. 1 , pp. 135 - 152 .

Bell , D.R. , Gallia , S. and Moreno , A. ( 2014 ), “ How to win in an omnichannel world ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 56 No. 1 , pp. 45 - 53 .

Bowersox , D.J. , Closs , D.J. , Cooper , M.B. and John , C.B. ( 2012 ), Supply Chain Logistics Management , 4th ed. , McGraw-Hill , New York, NY .

Boyer , K. and Hult , G. ( 2005 ), “ Extending the supply chain: integrating operations and marketing in the online grocery industry ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 23 No. 6 , pp. 642 - 661 .

Boyer , K. and Hult , G. ( 2006 ), “ Customer behavioral intentions for online purchases: an examination of fulfillment method and customer experience level ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 124 - 147 .

Boyer , K.K. , Prud’homme , A.M. and Chung , W. ( 2009 ), “ The last mile challenge: evaluating the effects of customer density and delivery window patterns ”, Journal of Business Logistics , Vol. 30 No. 1 , pp. 185 - 201 .

Busse , C. , Schleper , M.C. , Weilenmann , J. and Wagner , S.M. ( 2017 ), “ Extending the supply chain visibility boundary: utilizing stakeholders for identifying supply chain sustainability risks ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 47 No. 1 , pp. 18 - 40 .

Campbell , A.M. and Savelsbergh , M. ( 2005 ), “ Decision support for consumer direct grocery initiatives ”, Transportation Science , Vol. 39 No. 3 , pp. 313 - 327 .

Campbell , A.M. and Savelsbergh , M. ( 2006 ), “ Incentive schemes for attended home delivery services ”, Transportation Science , Vol. 40 No. 3 , pp. 327 - 341 .

Cassidy , W.B. ( 2017 ), “ Last-mile business explodes on e-commerce demand ”, available at: www.joc.com/international-logistics/logistics-providers/last-mile-business-explodes-e-commerce-demand_20170529.html/ (accessed 16 September 2017 ).

Chopra , S. ( 2003 ), “ Designing the distribution network in a supply chain ”, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review , Vol. 39 No. 2003 , pp. 123 - 140 .

Crainic , T.G. , Ricciardi , N. and Storchi , G. ( 2009 ), “ Models for evaluating and planning city logistics systems ”, Transportation Science , Vol. 43 No. 4 , pp. 432 - 454 .

Cremer , R.D. , Laing , A. , Galliers , B. and Kiem , A. ( 2015 ), Academic Journal Guide 2015 , Association of Business Schools , London .

Dablanc , L. , Giuliano , G. , Holliday , K. and O’Brien , T. ( 2013 ), “ Best practices in urban freight management – lessons from an international survey ”, Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board , Vol. 2379 , pp. 29 - 38 , available at: http://trrjournalonline.trb.org/doi/abs/10.3141/2379-04

De Koster , R.B.M. ( 2002 ), “ Distribution structures for food home shopping ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 32 No. 5 , pp. 362 - 380 .

Doty , D.H. , Glick , W.H. and Huber , G.P. ( 1993 ), “ Fit, equifinality, and organizational effectiveness: a test of two configurational theories ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 36 No. 6 , pp. 1196 - 1250 .

Dumrongsiri , A. , Fan , M. , Jain , A. and Moinzadeh , K. ( 2008 ), “ A supply chain model with direct and retail channels ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 187 No. 3 , pp. 691 - 718 .

Easterby-Smith , M. , Thorpe , R. and Lowe , A. ( 2002 ), Management Research: An Introduction , Sage , London .

Ehmke , J.F. and Mattfeld , D.C. ( 2012 ), “ Vehicle routing for attended home delivery in city logistics ”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 39 No. 2012 , pp. 622 - 632 .

Esper , T.L. , Jensen , T.D. , Turnipseed , F.L. and Burton , S. ( 2003 ), “ The last mile: an examination of effects of online retail delivery strategies on consumers ”, Journal of Business Logistics , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 177 - 203 .

Fernie , J. and Sparks , L. ( 2009 ), Logistics and Retail Management , 3rd ed. , Kogan Page , London .

Fernie , J. , Sparks , L. and McKinnon , A.C. ( 2010 ), “ Retail logistics in the UK: past, present and future ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 38 Nos 11/12 , pp. 894 - 914 .

Forman , C. , Ghose , A. and Goldfarb , A. ( 2009 ), “ Competition between local and electronic markets: how the benefit of buying online depends on where you live ”, Management Science , Vol. 55 No. 1 , pp. 47 - 57 .

Gallino , S. and Moreno , A. ( 2014 ), “ Integration of online and offline channels in retail: the impact of sharing reliable inventory availability information ”, Management Science , Vol. 60 No. 6 , pp. 1434 - 1451 .

Gao , F. and Su , X. ( 2017 ), “ Omnichannel retail operations with buy-online-and-pick-up-in-store ”, Management Science , Vol. 63 No. 8 , pp. 2478 - 2492 .

Gary , G. , Rashid , M. and Eve , C. ( 2015 ), “ Exploring future cityscapes through urban logistics prototyping: a technical viewpoint ”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 341 - 352 .

Gevaers , R. , Van de Voorde , E. and Vanelslander , T. ( 2011 ), “ Characteristics and typology of last-mile logistics from an innovation perspective in an urban context ”, in Macharis , C. and Melo , S. (Eds), City Distribution and Urban Freight Transport , Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. , Cheltenham , pp. 56 - 71 , available at: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=DpYwMe9fBEkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA56&dq=%E2%80%9CCharacteristics+and+typology+of+last-mile+logistics+from+an+innovation+perspective+in+an+urban+context&ots=Gjvpb_6-Of&sig=S1ZYhHZ0gX1Ob6QBWKiNQ-wMkWc#v=onepage&q=%E2%80%9CCharacteristics%20and%20typology%20of%20last-mile%20logistics%20from%20an%20innovation%20perspective%20in%20an%20urban%20context&f=false

Glasser , B.G. and Strauss , A.L. ( 1967 ), The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research , Aldine , Chicago, IL .

Greenhalgh , T. and Peacock , R. ( 2005 ), “ Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources ”, British Medical Journal , Vol. 331 Nos 7524 , pp. 1064 - 1065 .

Hamari , J. , Sjöklint , M. and Ukkonen , A. ( 2016 ), “ The sharing economy: why people participate in collaborative consumption ”, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology , Vol. 67 No. 9 , pp. 2047 - 2059 .

Harrington , T.S. , Srai , J.S. , Kumar , M. and Wohlrab , J. ( 2016 ), “ Identifying design criteria for urban system ‘last-mile’ solutions – a multi-stakeholder perspective ”, Production Planning & Control , Vol. 27 No. 6 , pp. 456 - 476 .

Holloway , S.S. , van Eijnatten , F.M. , Romme , A.G.L. and Demerouti , E. ( 2016 ), “ Developing actionable knowledge on value crafting: a design science approach ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69 No. 5 , pp. 1639 - 1643 .

Hübner , A. , Kuhn , H. and Wollenburg , J. ( 2016 ), “ Last mile fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel grocery retailing ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 44 No. 3 , pp. 228 - 247 .

Hübner , A. , Wollenburg , J. and Holzapfel , A. ( 2016 ), “ Retail logistics in the transition from multi-channel to omni-channel ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 46 Nos 6/7 , pp. 562 - 583 .

Ishfaq , R. , Defee , C.C. and Gibson , B.J. ( 2016 ), “ Realignment of the physical distribution process in omni-channel fulfillment ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 46 Nos 6/7 , pp. 543 - 561 .

Jauch , L.R. and Osborn , R.N. ( 1981 ), “ Toward an integrated theory of strategy ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 491 - 498 .

Johnson , M.E. and Whang , S. ( 2002 ), “ e-Business and supply chain management: an overview and framework ”, Production and Operations Management , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 413 - 423 .

Kämäräinen , V. and Punakivi , M. ( 2002 ), “ Developing cost-effective operations for the e-grocery supply chain ”, International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications , Vol. 5 No. 3 , pp. 285 - 298 .

Kämäräinen , V. , Saranen , J. and Holmström , J. ( 2001 ), “ The reception box impact on home delivery efficiency in the e-grocery business ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 31 No. 6 , pp. 414 - 426 .

Kull , T.J. , Boyer , K. and Calantone , R. ( 2007 ), “ Last-mile supply chain efficiency: an analysis of learning curves in online ordering ”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management , Vol. 27 No. 4 , pp. 409 - 434 .

Lagorio , A. , Pinto , R. and Golini , R. ( 2016 ), “ Research in urban logistics: a systematic literature review ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 46 No. 10 , pp. 908 - 931 .

Lau , H.K. ( 2012 ), “ Demand management in downstream wholesale and retail distribution: a case study ”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal , Vol. 17 No. 6 , pp. 638 - 654 .

Lawrence , P.R. and Lorsch , J.W. ( 1967 ), Organization and Environment , Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA .

Lee , H.L. and Whang , S. ( 2001 ), “ Winning the last mile in e-commerce ”, MIT Sloan Management Review , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 54 - 62 .

Li , Z. , Lu , Q. and Talebian , M. ( 2015 ), “ Online versus bricks-and-mortar retailing: a comparison of price, assortment and delivery time ”, International Journal of Production Research , Vol. 53 No. 13 , pp. 3823 - 3835 .

Lim , S.F.W.T. and Srai , J.S. ( 2018 ), “ Examining the anatomy of last-mile distribution in e-commerce omnichannel retailing: a supply network configuration approach ”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management (forthcoming) .

Lim , S.F.W.T. , Wang , L. and Srai , J.S. ( 2017 ), “ Wal-mart’s omni-channel synergy ”, Supply Chain Management Review , September/October , pp. 30 - 37 , available at: www.scmr.com/article/wal_marts_omni_channel_synergy

Lim , S.F.W.T. , Rabinovich , E. , Rogers , D.S. and Laseter , T.M. ( 2016 ), “ Last-mile supply network distribution in omnichannel retailing: a configuration-based typology ”, Foundations and Trends in Technology Information and Operations Management , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 87 .

Lopez , E. ( 2017 ), “ Last-mile delivery options grow ever more popular ”, Supply Chain Dive, available at: www.supplychaindive.com/news/last-mile-technology-options-investment/442453/ (accessed 2 July 2017 ).

McKevitt , J. ( 2017 ), “ FedEx and UPS to compete with USPS for last-mile delivery ”, Supply Chain Dive, available at: www.internetretailer.com/2015/07/29/global-e-commerce-set-grow-25-2015 (accessed 2 July 2017 ).

McKinnon , A.C. and Tallam , D. ( 2003 ), “ Unattended delivery to the home: an assessment of the security implications ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 30 - 41 .

McLeod , F. , Cherrett , T. and Song , L. ( 2006 ), “ Transport impacts of local collection/delivery points ”, International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 307 - 317 .

Mangiaracina , R. , Song , G. and Perego , A. ( 2015 ), “ Distribution network design: a literature review and a research agenda ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 45 No. 5 , pp. 506 - 531 .

Meredith , J. ( 1993 ), “ Theory building through conceptual methods ”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management , Vol. 13 No. 5 , pp. 3 - 11 .

Miller , D. ( 1986 ), “ Configurations of strategy and structure: towards a synthesis ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 233 - 249 .

Netessine , S. and Rudi , N. ( 2006 ), “ Supply chain choice on the Internet ”, Management Science , Vol. 52 No. 6 , pp. 844 - 864 .

O’Brien , M. ( 2015 ), “ eBay shuts down same-day delivery pilots ”, Multichannel Merchant, available at: http://multichannelmerchant.com/news/ebay-shuts-day-delivery-pilots-28072015/ (accessed 6 September 2015 ).

Pilbeam , C. , Alvarez , G. and Wilson , W. ( 2012 ), “ The governance of supply networks: a systematic literature review ”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal , Vol. 17 No. 4 , pp. 358 - 376 .

Piotrowicz , W. and Cuthbertson , R. ( 2014 ), “ Introduction to the special issue information technology in retail: toward omnichannel retailing ”, International Journal of Electronic Commerce , Vol. 18 No. 4 , pp. 5 - 16 .

Punakivi , M. and Saranen , J. ( 2001 ), “ Identifying the success factors in e-grocery home delivery ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 156 - 163 .

Punakivi , M. and Tanskanen , K. ( 2002 ), “ Increasing the cost efficiency of e-fulfilment using shared reception boxes ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 30 No. 10 , pp. 498 - 507 .

Punakivi , M. , Yrjölä , H. and Holmström , J. ( 2001 ), “ Solving the last mile issue – reception box or delivery box ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 31 No. 6 , pp. 427 - 439 .

Rabinovich , E. and Bailey , J.P. ( 2004 ), “ Physical distribution service quality in internet retailing: service pricing, transaction attributes, and firm attributes ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 21 No. 6 , pp. 651 - 672 .

Rabinovich , E. , Rungtusanatham , M. and Laseter , T. ( 2008 ), “ Physical distribution service performance and Internet retailer margins: the drop-shipping context ”, Journal of Operations Management , Vol. 26 No. 6 , pp. 767 - 780 .

Randall , T. , Netessine , S. and Rudi , N. ( 2006 ), “ An empirical examination of the decision to invest in fulfillment capabilities: a study of Internet retailers ”, Management Science , Vol. 52 No. 4 , pp. 567 - 580 .

Richard , W. and Beverly , W. ( 2014 ), “ Special issue: building theory in supply chain management through ‘systematic reviews’ of the literature ”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal , Vol. 19 Nos 5/6 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-08-2014-0275

Romme , A.G.L. ( 2003 ), “ Making a difference: organization as design ”, Organization Science , Vol. 14 No. 5 , pp. 558 - 573 .

Rousseau , D.M. , Manning , J. and Denyer , D. ( 2008 ), “ Evidence in management and organizational science: assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses ”, Academy of Management Annals , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 475 - 515 .

Saenz , M.J. and Koufteros , X. ( 2015 ), “ Special issue on literature reviews in supply chain management and logistics ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 45 Nos 1/2 , available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-12-2014-0305

Savelsbergh , M. and Van Woensel , T. ( 2016 ), “ 50th anniversary invited article – city logistics: challenges and opportunities ”, Transportation Science , Vol. 50 No. 2 , pp. 579 - 590 .

Småros , J. and Holmström , J. ( 2000 ), “ Viewpoint: reaching the consumer through e-grocery VMI ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 55 - 61 .

Sternbeck , M.G. and Kuhn , H. ( 2014 ), “ An integrative approach to determine store delivery patterns in grocery retailing ”, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review , Vol. 70 No. 2014 , pp. 205 - 224 .

Supply Chain Council ( 2010 ), “ Supply chain operations reference model: overview of SCOR version 10.0 ”, Supply Chain Council Inc., Pittsburgh, PA .

Tranfield , D. , Denyer , D. and Smart , P. ( 2003 ), “ Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of a systematic review ”, British Journal of Management , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 207 - 222 .

Vanelslander , T. , Deketele , L. and Van Hove , D. ( 2013 ), “ Commonly used e-commerce supply chains for fast moving consumer goods: comparison and suggestions for improvement ”, International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 243 - 256 .

Wang , X. , Zhan , L. , Ruan , J. and Zhang , J. ( 2014 ), “ How to choose ‘last mile’ delivery modes for e-fulfillment ”, Mathematical Problems in Engineering , Vol. 2014 No. 2014 , pp. 1 - 11 .

Wang , Y. , Zhang , D. , Liu , Q. , Shen , F. and Lee , L.H. ( 2016 ), “ Towards enhancing the last-mile delivery: an effective crowd-tasking model with scalable solutions ”, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review , Vol. 93 No. 2016 , pp. 279 - 293 .

Wanke , P.F. ( 2012 ), “ Product, operation, and demand relationships between manufacturers and retailers ”, Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review , Vol. 48 No. 1 , pp. 340 - 354 .

Weltevreden , J.W.J. ( 2008 ), “ B2c e-commerce logistics: the rise of collection-and-delivery points in the Netherlands ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 36 No. 8 , pp. 638 - 660 .

Wollenburg , J. , Hübner , A. , Kuhn , H. and Trautrims , A. ( 2017 ), “ From bricks-and-mortar to bricks-and-clicks – logistics networks in omni-channel grocery retailing ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , available at: http://link.springer.com.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/chapter/10.1007/978-90-481-2471-8_17/fulltext.html

Yang , X. and Strauss , A.K. ( 2017 ), “ An Approximate dynamic programming approach to attended home delivery management ”, European Journal of Operational Research , Vol. 263 No. 3 , pp. 935 - 945 .

Yrjölä , H. ( 2001 ), “ Physical distribution considerations for electronic grocery shopping ”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management , Vol. 31 No. 10 , pp. 746 - 761 .

Yuan , X. and David , B.G. ( 2006 ), “ Developing a framework for measuring physical distribution service quality of multi-channel and ‘pure player’ internet retailers ”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management , Vol. 34 Nos 4/5 , pp. 278 - 289 .

Zott , C. and Amit , R. ( 2007 ), “ Business model design and the performance of entrepreneurial firms ”, Organization Science , Vol. 18 No. 2 , pp. 181 - 199 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

E-Commerce Website: A Systematic Literature Review

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2024

E-commerce and foreign direct investment: pioneering a new era of trade strategies

- Yugang He ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5758-069X 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 566 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

337 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

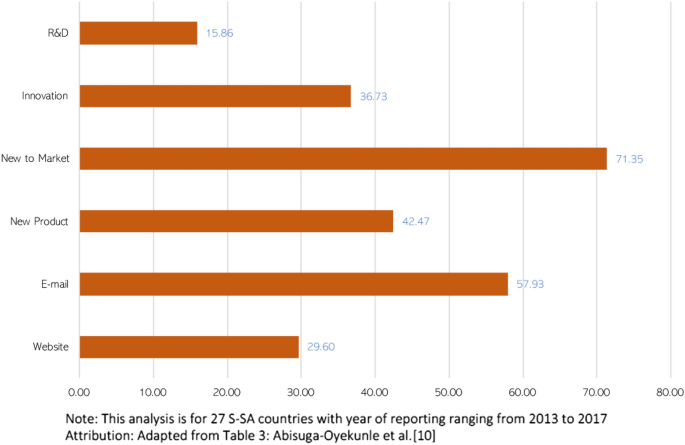

- Business and management

This study explores the dynamic interplay between foreign direct investment, e-commerce, and China’s export growth from 2005 to 2022 against the backdrop of the rapidly evolving global economy. Utilizing advanced analytical models that combine province- and year-fixed effects with fully modified ordinary least squares and dynamic ordinary least-squares methodologies, we delve into how foreign direct investment and e-commerce collectively boost China’s export capabilities. Our findings highlight a significant alignment between China’s export expansion and the global sustainable development agenda. We observe that China’s export growth transcends mere international investment and digital market engagement, incorporating sustainable practices such as effective utilization of local labor resources and an emphasis on technological advancements. This study also uncovers how knowledge capital and educational attainment positively impact export figures. A notable regional disparity is observed, with the eastern regions of China being more responsive to foreign direct investment and e-commerce influences on export trade compared to their western counterparts. This disparity underscores the need for region-specific policy approaches and sustainable strategies to evenly distribute the benefits of foreign direct investment and e-commerce. The study concludes that while foreign direct investment and e-commerce are crucial for China’s export growth, the underlying theme is sustainable development, with technological innovation and human capital being key to ongoing export success. The findings advocate for policies that balance economic drivers with sustainable development goals, ensuring both economic prosperity and environmental sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Foreign direct investment and the innovation performance of local enterprises

Export duration and firm markups: evidence from china.

The rise and fall of countries in the global value chains

Introduction.

In its ascent towards global economic preeminence, China has undergone transformative alterations in its provincial export trade architecture, metamorphosed by the intricate orchestration of economic vectors and technological advents within the globally interconnected milieu. Central to this paradigm shift is the synthesis of foreign direct investment, the burgeoning trajectory of e-commerce, the proper deployment of indigenous labor resources, and tactically channeled technological capital. An adept comprehension of these intricate dynamics becomes essential for informed forecasts pertaining to China’s export evolution and its symbiotic relationship with sustainable developmental objectives. The exponential proliferation of China’s export vertical can be attributed to its accurate incorporation of foreign direct investment, pivotal in catalyzing technological assimilations, fortifying workforce competencies, and forging novel market corridors. In tandem, the surge in e-commerce has revolutionized market penetration modalities, enabling Chinese offerings to seamlessly infiltrate global commerce arenas. Moreover, China’s abundant labor capital, juxtaposed with deliberate technological ventures, has accentuated its competitive foothold in global trade arenas. Yet, the velocity of this expansive trajectory beckons a meticulous assessment through a prism of sustainability, addressing facets of resource optimization, laboral integrity, and ecological prudence.