- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Personal Finance

How COVID-19 Changed Our Saving and Spending Habits

The pandemic led to a tale of two economies

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/tymkiwmeyer2-13ea6eb62829478b8a679564504a746f.jpg)

As the U.S. economy begins to recover and reopen, many consumers are still scrambling to regain their financial footing. While the conventional wisdom is to sock away six to 12 months worth of savings, that became an impossibility for many during the COVID-19 pandemic, as millions of people lost their jobs, small businesses were forced to shutter, and day-to-day living expenses piled up . The stimulus checks helped, but not necessarily enough.

There is some good news on the horizon. As more Americans get vaccinated and infection rates ease, the U.S. economy is slowly reemerging. Businesses are reopening, hiring is on the rise, and that eventually should ease some of the financial strain felt by many.

In March 2021, the personal savings rate —which reflects the ratio of total personal savings minus disposable income —surged to 26.6%. While saving is up, that figure also indicates a short-term slowdown in consumer spending , as people hold onto more of their money. The last time the savings rate was this high was April 2020, when it hit 33%. While it has slowly eased during the past 12 months, it has remained above 12%, compared with pre-pandemic levels that were below 10%.

Nonetheless, an increase in savings doesn’t mean that everyone is sitting on piles of cash. “What someone should do with their personal savings is entirely circumstantial, however, as some industries have been hit harder than others,” says Ryan Detrick , vice president and market strategist with Cornerstone Wealth Management. “If you’ve been one of the lucky ones who hasn’t had a major disruption in life because of the pandemic, now can be a good idea to assess any outstanding debt and either refinance while interest rates are low or consider paying off some of this debt. For those who are barely making ends meet, it’s a complicated subject to provide advice to.”

Key Takeaways

- The COVID-19 pandemic created a tale of two economies: those who were able to save, and those who struggled to make ends meet.

- Financial advice remains the same, pre- and post-pandemic: It’s important to build up an emergency savings fund and create a financial plan.

- COVID-19 also highlighted the need to have a budget, however small it may be.

- Financial advisors are available to help. Ask for referrals, and take it one step at a time.

- Many racked up debt during the pandemic, while others were able to save.

- Savers are ready to spend, but advisors caution about reining in the urge to splurge.

- Sixty-four percent of Americans called themselves savers in 2020, and 80% said they planned to continue to save more than they spend in 2021.

The COVID-19 Financial Hit

While the longer-term outlook is looking a bit brighter, the near term remains unsettled. Consider this: Half of Americans in a recent survey by Investopedia sister site The Balance said they have less than $250 left over each month after expenses, and some 12% said they have nothing left over. Debt is also weighing people down, with 29% saying their credit card debt had increased during the pandemic. According to a Charles Schwab survey, 53% of Americans have been financially impacted by the pandemic.

A separate survey by T. Rowe Price painted an even bleaker picture, with nearly 70% of respondents saying their financial well-being had been negatively impacted by COVID-19, citing layoffs, reduced work hours/salary cuts, and overall less income as the top three reasons. Prior to the pandemic, 71% said they had a sufficient emergency fund . Now, 42% say they need to replenish their emergency fund, with 44% saying they need to increase the size of it.

“The pandemic has reminded us of the importance of having a budget,” says James Boyd, education coach at TD Ameritrade. “When you know where your money is going, it can make it easier to isolate needs and wants and shift more toward necessities.”

For some, that may be much easier said than done. “The pandemic impacted people very differently,” says Brian O’Leary , wealth advisor and senior analyst at Aline Wealth. “The key lesson is circumstances can change very rapidly.”

Only 33% surveyed by T. Rowe Price (and 30% surveyed by The Balance ) said their finances had improved during the pandemic, mostly due to less spending—a luxury that not everyone had.

While there was a lot more saving going on over the past year, “I have a concern that people will feel a sense of relief coming out of the pandemic and overspend to make up for lost time,” says Michael Resnick , senior wealth management advisor at GCG Financial. Nearly a quarter of Americans said they are ready to splurge for that exact reason, according to the Schwab survey, while 47% just want to get back to living and spending like they were pre-pandemic.

“We encourage it, as long as it’s done responsibly,” says O’Leary, adding that giving in to that urge should be done as part of a solid financial plan “that includes a buffer.” A recent survey from McKinsey & Company shows that more than 50% of U.S. consumers plan on splurging this year, with half of those respondents citing pandemic fatigue, while the other half said they’re willing to wait until the pandemic is over before breaking out their wallets.

Spending Makes a Comeback

As more people get vaccinated, the urge to get out and spend will likely continue to increase. “While COVID-19 upended nearly every corner of American life, many are starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel and are ready for a reset,” Jonathan Craig, Charles Schwab senior executive vice president and head of Investor Services, said in a statement. The Schwab survey showed that 64% of Americans called themselves savers in 2020, and 80% said they planned to continue to save more than they spend in 2021. More good news: According to the McKinsey survey, 86% of those who are vaccinated either expect their finances to return to normal by the end of the year (52%) or their finances are already back to normal (34%).

All the same, the National Retail Federation (NRF) expects a pickup in spending. The NRF is predicting that retail spending will top $4.3 trillion in 2021 as more people get vaccinated. That’s up from $4 trillion in 2020 and $3.9 trillion in 2019.

While all of those figures are good news for the economy, that doesn’t mean consumers should spend with abandon. “The basic tenet of financial planning, of thinking long term and spending less than you earn while keeping an emergency fund, has proven to be the saving grace for many of my clients throughout this past year,” says Resnick.

Detrick agrees: “The age-old rule of thumb to aim to have six to 12 months of expenses saved in the event that you lose your job still applies, but perhaps the pandemic caused many to reevaluate the importance of this buffer and the likelihood that they may need to use it at some point.” It seems some are heeding that advice. Nearly one-third of those surveyed by The Balance said they were saving more now than before the pandemic, and one-fifth even managed to invest more.

Steps for Those Barely Getting By

Those in a more financially precarious position will need to proceed with more caution. “We expect the economy will rebound sharply—and it has so far—but it may not feel that way for everyone,” says Detrick. “While many types of debt received forbearance during the pandemic, it’s likely that these protections will eventually be lifted, so being prepared for any debt obligations will be critical as we begin to see the light at the end of the tunnel of the pandemic.”

Some of it comes down to planning, yet only about one-third of Americans actually have a financial plan in writing. Of those without a plan, 42% say it’s because they don’t have enough money to make it worthwhile. “From a fiscal standpoint, it’s going to require a massive intervention on their part,” says O’Leary.

Among the things to consider are:

- What are the prospects of your income returning? If the answer is “not good,” then you may be forced into thinking about a career change, which comes with its own set of challenges and stressors.

- If you can’t do anything to improve your income, then look at your expenses. Is there any wiggle room to negotiate payment plans or cut anything out?

- If you’ve received COVID-19 mortgage forbearance , rent relief , or student loan relief , then look carefully at the rules about when it ends and what happens next.

“There is a whole spectrum of actions you can take, and you have to be creative,” says O’Leary, adding that while some people may face some very hard choices, “it’s better than being forced into not having any choices later.”

The pandemic has been a scary wake-up call about how lives can be overturned with very little warning. “For many, this will be an experience they don’t want to relive,” says O’Leary.

As the economy regains its footing, having to dig out of debt makes it even more crucial to start thinking about the future and set manageable short- and long-term goals. “What we really need to do is be honest about your debt and desire to address those issues,” O’Leary says. He acknowledges that it may seem like a lofty goal for those who are barely making ends meet, but there is help out there.

Among the things you can do are:

- Talk to your friends and find out what works (or doesn’t work) for them.

- Ask friends to recommend a financial advisor . Many will give a free initial consultation, while some, such as the Foundation for Financial Planning, offer pro bono services.

- Most important: Take it one step at a time.

The ultimate goal is to work toward building an emergency fund. That advice has been true pre- and post-pandemic. How that is achieved will vary depending on your circumstances.

“A lot of people learned some tough lessons,” says O’Leary, but what’s important is to “start somewhere.”

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, FRED. “ Personal Saving Rate .”

Congressional Research Service. “ Introduction to U.S. Economy: Personal Saving ,” Page 1.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “ National Data: GDP and Personal Income .”

Charles Schwab. “ Charles Schwab Modern Wealth Survey 2021 ,” Page 7.

Charles Schwab. “ Charles Schwab Modern Wealth Survey 2021 ,” Page 10.

T. Rowe Price. “ 13th Annual Parents, Kids and Money Survey ,” Pages 6–8.

T. Rowe Price. “ 13th Annual Parents, Kids and Money Survey ,” Page 5.

Charles Schwab. “ Charles Schwab Modern Wealth Survey 2021 ,” Page 5.

McKinsey & Company. “ Survey: U.S. Consumer Sentiment During the Coronavirus Crisis .”

McKinsey & Company. “ McKinsey Survey: U.S. Consumer Sentiment During the Coronavirus Crisis ,” Page 16.

Charles Schwab. “ Ready to Reset the ’20s: Economic Optimism, Celebratory Splurges and Healthy Money Habits on the Horizon as Americans Emerge From the Pandemic .”

McKinsey & Company. “ McKinsey Survey: U.S. Consumer Sentiment During the Coronavirus Crisis ,” Page 13.

National Retail Federation. “ NRF Forecasts Retail Sales to Exceed $4.33T in 2021 as Vaccine Rollout Expands .”

Charles Schwab. “ Charles Schwab Modern Wealth Survey 2021 ,” Pages 15,18.

Foundation for Financial Planning. “ FFP Corporate Advisory Council: Joint Statement on Pro Bono .”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1300980786-63d6240c41174e3aa6bd489031dc2bc4.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

How We’re Saving Money During the Pandemic

From fuel to clothing, lifestyle changes in COVID-19 present opportunities to cut spending

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

When Lori Levy looks back at the past year, she’s painfully aware of what she’s missed out on because of the pandemic. Her son didn’t have an in-person high school graduation, and she’s gone nearly two years without seeing her daughter, who lives in California.

“It’s just nice to know that you have that money when you need it,” said Levy, a nurse educator in the Clinical Education and Professional Development Department.

Throughout the pandemic, most Duke employees have seen their spending habits altered, resulting in opportunities to save money.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis , Americans’ personal saving rate – the percentage of disposable income that’s saved – went from 8.3 percent in February of 2020 to 33.7 percent in April of 2020. In January of 2021, it remained high at 20.5 percent.

“On one hand, we have murky waters ahead, but on the other hand, people are finding themselves with extra cash,” said Benjamen Parker, a retirement planner with Fidelity, the primary record keeper for Duke’s Faculty and Staff Retirement Plan . “So now, they want to know what they should do with this extra money?”

As you ponder how the pandemic has shaped your financial situation, consider how some colleagues have found ways to save money.

Be Smart with Extra Savings

When he speaks to Duke employees seeking financial advice, Parker often starts with recommending people build a household budget .

If you haven’t done so already, a budget is the easiest way to see where your money goes and make sure that it covers important expenses and priorities, such as retirement and emergency savings.

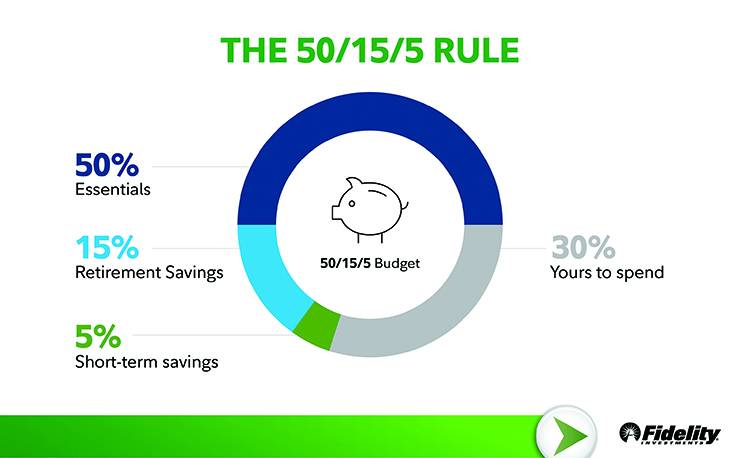

Fidelity recommends using the 50/15/5 approach , where 50 percent of your income goes to essentials, 15 to retirement savings and five for emergency savings. The ideal amount of emergency savings would be enough to cover three-to-six months of expenses.

After a year-long suspension of contributions to the faculty and staff retirement plan due to the financial pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic, contributions will return as scheduled on July 1, 2021.

Casual Savings on Clothing

With a whiteboard, multiple computer monitors and constellations of sticky notes on her wall, Emily Jackson has built a home workspace that has plenty of the touches of her on-campus office in Erwin Square.

Prior to the pandemic, Jackson spent around $30 to $50 per week on dry cleaning.

“That’s definitely a savings for me,” said Jackson, a senior regulatory coordinator for the Duke School of Medicine’s Pediatrics Department.

According to consumer spending data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis , Americans spent $23.9 billion less on clothing and footwear in the fourth quarter of 2020 than they did in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Jackson also said she’s appreciated not having to buy as many clothes, and if she ends up working on-site again, she hopes to keep her savings momentum going.

“When I look at my clothes, I just think, why did I need so much stuff?” Jackson said. “I think I’ll be more frugal once we go back.”

Fewer Trips to Gas Stations

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, John Owens’ position as a senior IT analyst with Duke’s Office of Information Technology, went remote, meaning he no longer had to make the roughly 70-minute round trip commute from his home in Mebane to his office in the American Tobacco Campus.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that in the fourth quarter of 2020, Americans spent $88.2 billion less on gasoline and other energy goods than they did in the fourth quarter of 2019.

The savings are just one of the positive developments Owens has experienced due to working remotely during the pandemic. Owens also appreciates having more time to get outdoors and walk and having the opportunity to eat healthier homemade meals instead of restaurant lunches at work, and

“Obviously, all of us were scared at first because we didn’t know how this was going to go and how it would affect us individually,” Owens said. “But finding positives anywhere has definitely been good.”

Family Finances

Since the start of the pandemic, Kate Davies has worked from home in Wake County alongside her two children, who are doing school work online.

So in addition to saving about $150 per month on gas and another $20 per month for her campus parking permit, Davies doesn’t have to pay $100 per month for the before-school care. She’s been able to use those savings to take care of some debt and increase her contributions to her retirement account.

But for Davies, an administrative assistant with Duke Counseling & Psychological Services (CAPS), the money is not nearly a valuable as the gift of time with her kids.

“It’s lovely, actually,” Davies said. “I really enjoy it. I feel like I get to be a parent for the first time because I’m not shipping them off to somebody else to look after them. It’s been nice to see them learn, share meals together and take them to soccer practice, which was something I wasn’t able to do before.”

Fewer Lunches Out

Prior to the pandemic, Emily James, a regional development director for Duke University Development, would spend around half of her workdays on the road, strengthening Duke’s connections to alumni, parents and friends in places such as Chicago, Pittsburgh, Indiana, Iowa and South Carolina. The rest of the time, she’d be at her downtown Durham workspace.

“Our office was in One City Center, which was great because it gave us access to a million restaurants,” she said.

Now that she’s working from home, James estimates that she’s saving around $30 to $50 per week by not eating out during the day. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that in the fourth quarter of 2020, Americans spent $194.9 billion less on food service and accommodations than they did in the fourth quarter of 2019.

James has been putting that savings to good use as it helped cover the cost of a tutor who would visit her house a few times a week to help her children who – until they returned to in-person learning in February – were completing their kindergarten and second grade schooling online.

“I was grateful to have her,” James said of the tutor. “She was a huge help.”

Got something you would like for us to cover? Send ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write [email protected] .

Follow Working@Duke on Twitter and Facebook .

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- A Year Into the Pandemic, Long-Term Financial Impact Weighs Heavily on Many Americans

Roughly half of non-retired adults say the economic consequences of the coronavirus outbreak will make it harder for them to achieve their financial goals

Table of contents.

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand Americans’ financial outlooks and how their personal financial situations have changed amid the coronavirus outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 10,334 U.S. adults in January 2021. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

References to those who have experienced job or wage loss include those who say they or someone in their household has been laid off (including temporarily) or furloughed or taken a pay cut since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020.

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party. Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and those who say they lean toward the Republican Party. Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and those who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree.

“Middle income” is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for panelists on the American Trends Panel. “Lower income” falls below that range; “upper income” falls above it. See the methodology for more details.

References to disabled adults include those who say a disability or handicap keeps them from fully participating in work, school, housework or other activities.

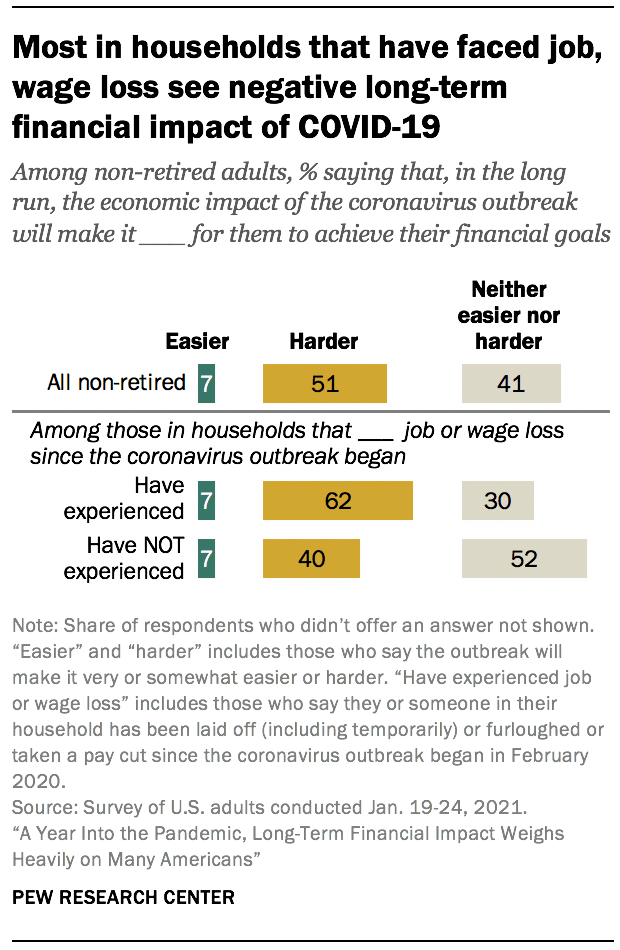

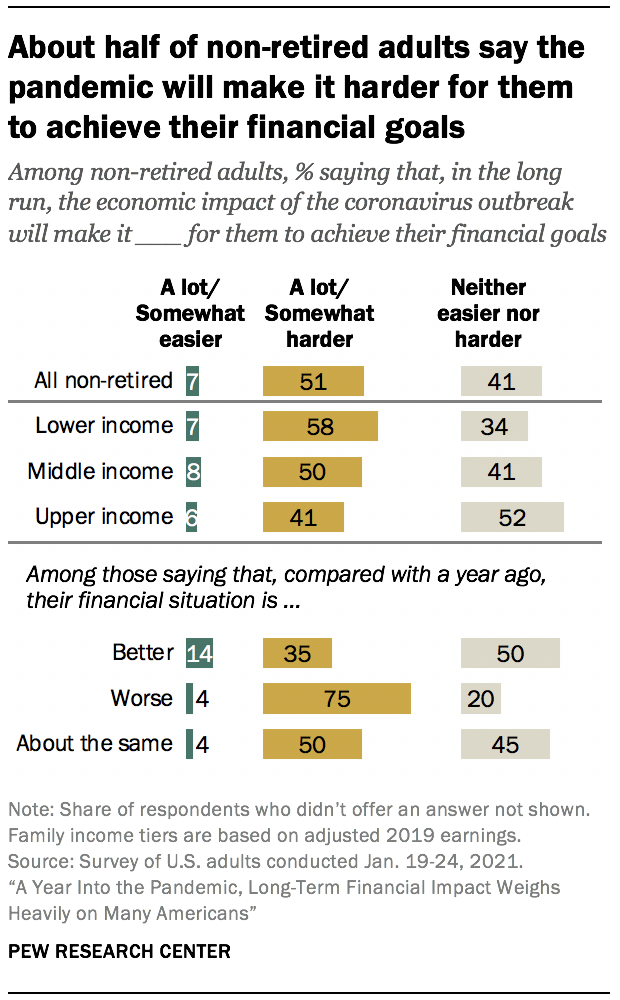

About a year since the coronavirus recession began, there are some signs of improvement in the U.S. labor market, and Americans are feeling somewhat better about their personal finances than they were early in the pandemic. Still, about half of non-retired adults say the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak will make it harder for them to achieve their long-term financial goals, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Among those who say their financial situation has gotten worse during the pandemic, 44% think it will take them three years or more to get back to where they were a year ago – including about one-in-ten who don’t think their finances will ever recover.

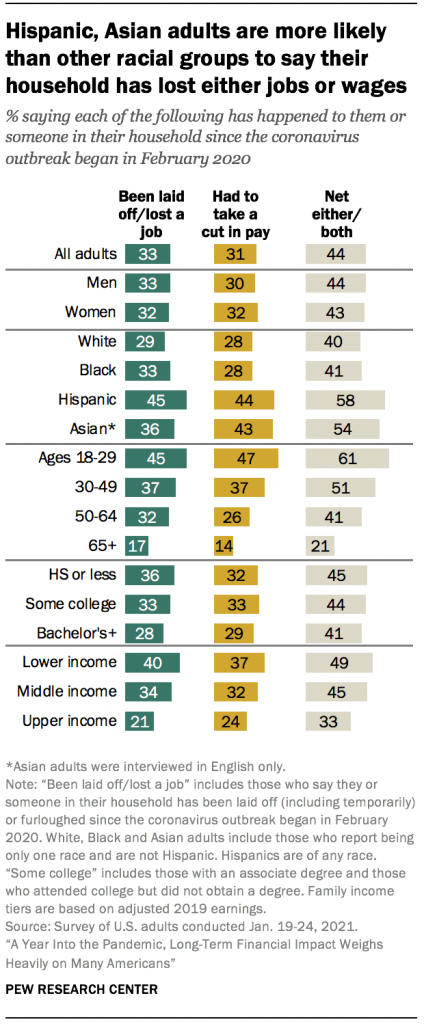

The economic fallout from COVID-19 continues to hit some segments of the population harder than others. Lower-income adults, as well as Hispanic and Asian Americans and adults younger than 30, are among the most likely to say they or someone in their household has lost a job or taken a pay cut since the outbreak began in February 2020. 1 Among those who’ve had these experiences, lower-income and Black adults are particularly likely to say they have taken on debt or put off paying their bills in order to cover lost wages or salary.

Related: Unemployed Americans are feeling the emotional strain of job loss; most have considered changing occupations

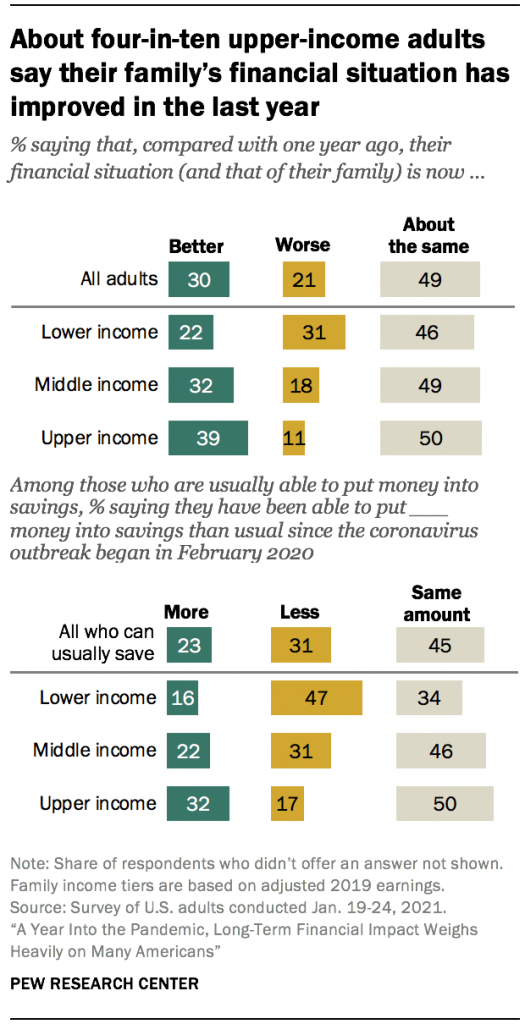

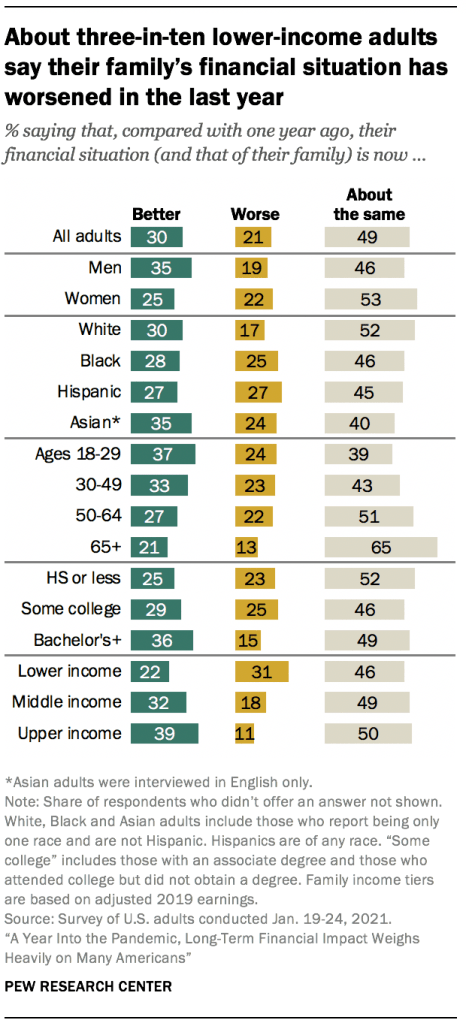

Adults with upper incomes have fared better. About four-in-ten (39%) say their family’s financial situation has improved compared with a year ago; 32% of those with middle incomes and just 22% of lower-income adults say the same. Upper-income adults are also more likely than those with middle or lower incomes to say they have been spending less and saving more money since the coronavirus outbreak began. (Family incomes are based on 2019 earnings.)

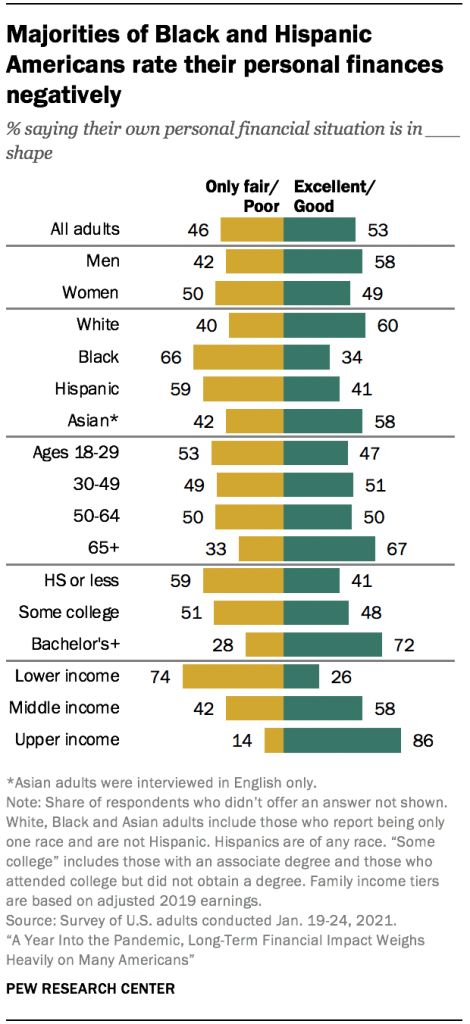

Overall, 53% of U.S. adults now rate their personal financial situation as excellent or good, up from 47% in April 2020 , when the U.S. economy was in a virtual freefall. More than eight-in-ten upper-income adults (86%) and 58% of those with middle incomes say their finances are in excellent or good shape, as do about six-in-ten or more adults with at least a four-year college degree, White and Asian adults, men, and adults ages 65 and older. In contrast, about three-quarters of lower-income adults (74%) and majorities of Black and Hispanic adults and those with a high school diploma or less education say their personal finances are in only fair or poor shape.

Upper-income and middle-income adults, who saw declines in their personal financial ratings from August 2019 to April 2020 , are now about as likely as they were before the coronavirus outbreak to say their personal finances are in excellent or good shape. Personal financial ratings have been more stable among lower-income adults.

Looking ahead, about half of non-retired adults (51%) say the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak will make achieving their long-term financial goals harder. Just 7% say the economic impact of the pandemic will make it easier and 41% say it’ll be neither easier nor harder for them to achieve their financial goals in the long run. Among those in households that experienced job or wage loss since the outbreak began, 62% say the economic impact of the pandemic will make it harder for them to achieve their financial goals, compared with four-in-ten of those who haven’t had these experiences.

The nationally representative survey of 10,334 U.S. adults was conducted Jan. 19-24, 2021, using the Center’s American Trends Panel . 2 Among the other key findings:

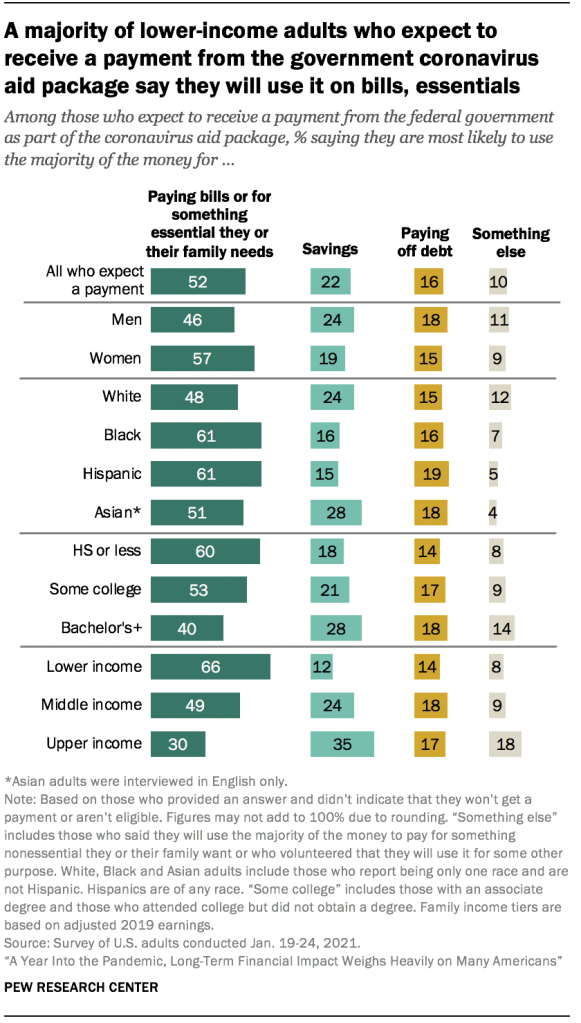

The way Americans are planning to use payments from the coronavirus aid package varies considerably by income. Among those who have received or expect to receive a payment from the federal government as part of the aid package, 66% of lower-income adults say they are most likely to use the majority of the money to pay bills or for something essential they or their family need; smaller shares of those with middle (49%) and upper (30%) incomes plan to use the money this way. About a third of those with upper incomes (35%) say they will likely put the money into savings.

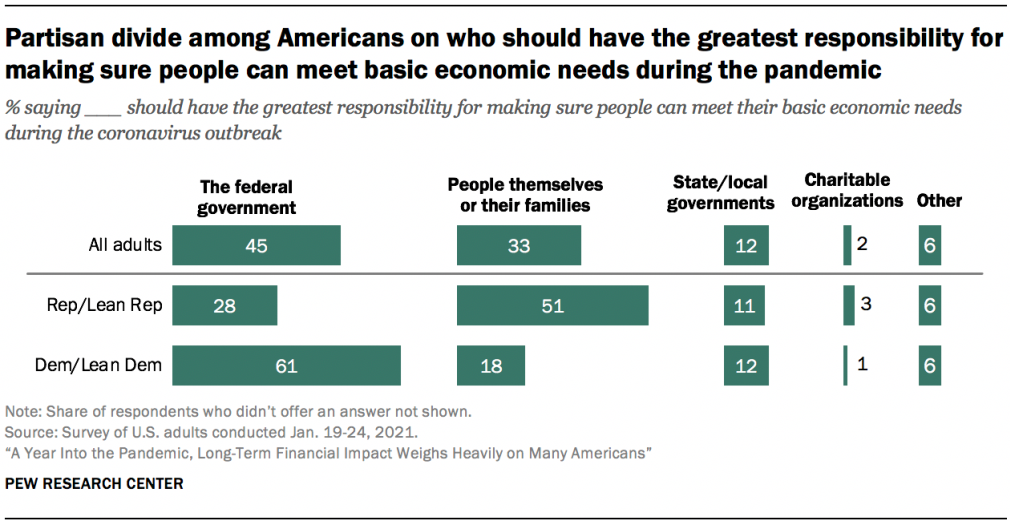

There’s no clear consensus among Americans on who should be responsible for making sure people can meet their basic economic needs during the pandemic. Some 45% say the federal government should have the greatest responsibility, while a third point to people themselves or their families. Smaller shares say state or local governments (12%), charitable organizations (2%) or another source (6%) should have the greatest responsibility to do this. These views vary widely across party lines. About six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners (61%) say the federal government should be mostly responsible for making sure people can meet their basic economic needs during the coronavirus outbreak, compared with 28% of Republicans and those who lean to the GOP. In turn, 51% of Republicans (vs. 18% of Democrats) say people themselves or their families should have this responsibility.

Financial concerns are less pressing than earlier in the pandemic, but many Americans remain worried about meeting some basic needs. About three-in-ten U.S. adults say they worry every day or almost every day about the amount of debt they have (30%) and their ability to save for retirement (29%). Roughly a quarter say they frequently worry about paying their bills (27%) and the cost of health care for them and their family (27%), and about one-in-five say they worry at least almost every day about paying their rent or mortgage (19%) or being able to buy enough food (18%). These concerns are felt more acutely by lower-income adults, as well as by those in households that have experienced job loss or pay cuts during the pandemic. Black and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say they worry about each of these every day or almost every day.

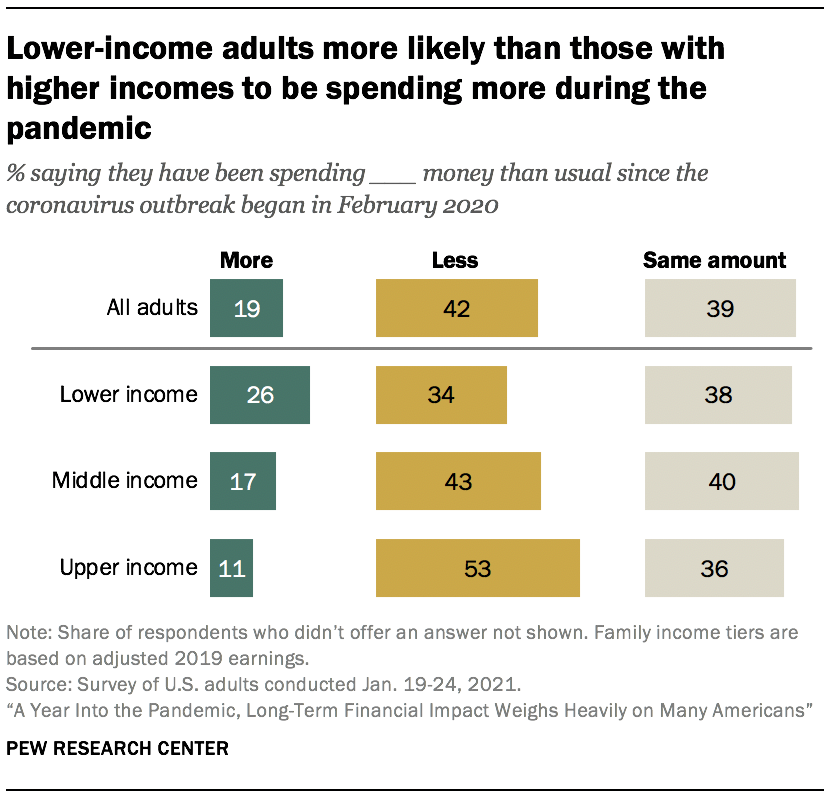

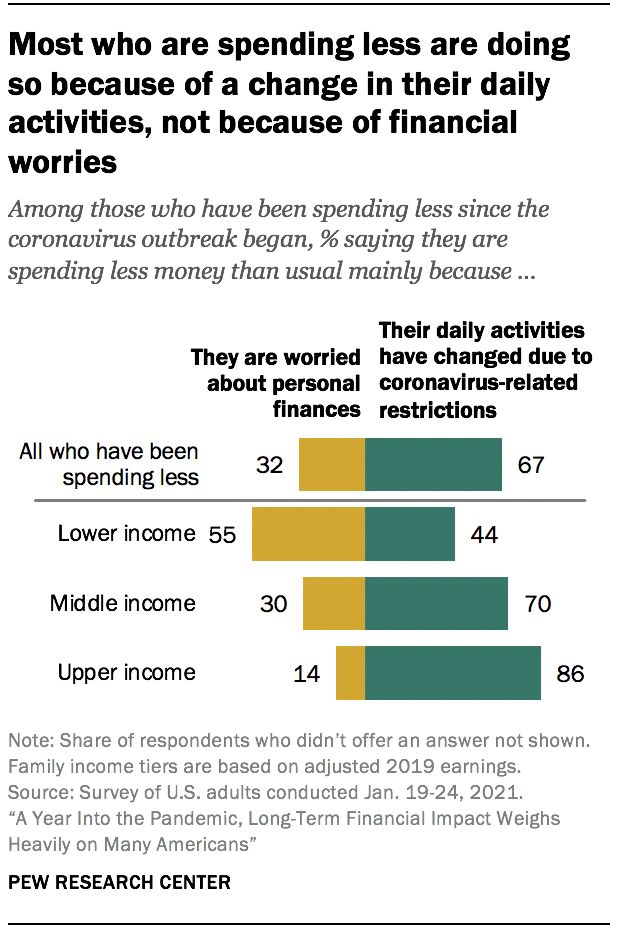

About four-in-ten Americans (42%) say they have been spending less money than usual since the pandemic began, and that is especially the case among upper-income adults. Some 53% of Americans with upper incomes say they’ve been spending less money, compared with 43% of those with middle incomes and 34% of those with lower incomes. Among those who say they have been spending less money, majorities with upper and middle incomes say this is mainly because their daily activities have changed due to coronavirus-related restrictions (86% and 70%, respectively). Among those with lower incomes, more say they’re spending less because they are worried about personal finances (55%) than because their daily activities have changed (44%).

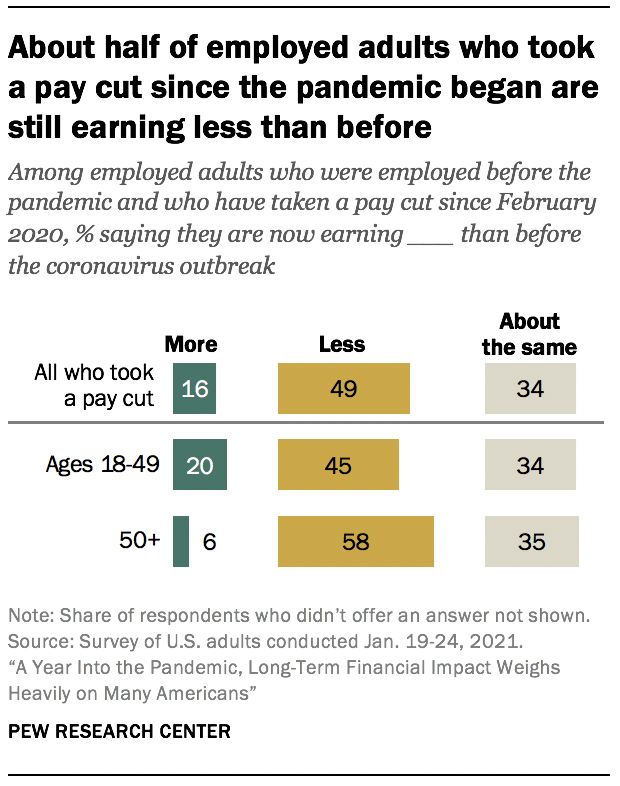

About half of workers who personally lost wages during the pandemic (49%) are still earning less money than before the coronavirus outbreak started. This is particularly the case among older workers: 58% of employed adults ages 50 and older who experienced a pay cut since the outbreak began say they’re earning less money than before, compared with 45% of those younger than 50. One-in-five in the younger group (vs. 6% of those 50 and older) say they are now earning more than they did before the pandemic began, while about a third in each group say they are earning about the same as before.

Personal financial ratings vary widely across racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups

A narrow majority of U.S. adults (53%) now describe their personal financial situation as excellent or good, up from 47% in April 2020 . The share saying their finances are in only fair or poor shape now stands at 46%, compared with 52% earlier in the pandemic.

About six-in-ten White (60%) and Asian adults (58%) currently say their personal financial situation is in excellent or good shape. In contrast, a majority of Black (66%) and Hispanic (59%) Americans say their finances are in only fair or poor shape.

Personal financial ratings also vary considerably by gender, educational attainment and income levels, as was the case early in the pandemic. A majority of men (58%) rate their personal financial situation as excellent or good; 49% of women do so. About seven-in-ten adults with at least a bachelor’s degree (72%) say their personal finances are in excellent or good shape, compared with 48% of those with some college and 41% of adults with a high school diploma or less education.

Income differences are particularly pronounced, with a gap of 60 percentage points between the shares of upper-income (86%) and lower-income (26%) adults who rate their financial situation as excellent or good. About six-in-ten adults with middle incomes (58%) say their finances are in excellent or good shape. Family incomes are based on 2019 earnings.

People who report having a disability (63%) are more likely than those who do not have a disability (42%) to describe their personal financial situation as only fair or poor. This difference remains after taking into account that disabled adults are more likely to have lower incomes than those who are not disabled (82% of lower-income adults with a disability vs. 69% of those who don’t have a disability offer negative assessments of their personal finances).

More Americans say their personal financial situation has improved in the last year than say it has gotten worse

Despite the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus outbreak, about half of U.S. adults (49%) say their family’s financial situation is about the same as it was a year ago; three-in-ten say it has improved, and 21% say it is now worse than it was a year ago.

Upper-income adults are more likely than other income groups to have seen an improvement in their finances: 39% say their family’s financial situation is now better, compared with 32% of those with middle incomes and an even smaller share of lower-income adults (22%). About three-in-ten adults with lower incomes (31%) say their family’s situation has worsened (vs. 18% of adults with middle incomes and 11% of those with upper incomes).

These assessments vary by educational attainment and other demographic characteristics. Some 36% of adults with a bachelor’s degree or more education say their family’s financial situation is now better than it was a year ago; 29% of those with some college and a quarter of those with a high school diploma or less education say the same.

About a third of men (35%) say their family’s financial situation has improved, while a smaller share of women (25%) say the same. In turn, women are more likely than men to say their family’s financial situation is about the same as it was last year (53% vs. 46%).

About a quarter of Black (25%), Hispanic (27%) and Asian (24%) adults say their family’s situation is worse now than it was a year ago; a smaller share of White adults (17%) say this. White adults are more likely than those from other groups to say their financial situation is largely unchanged. (Differences in the shares across racial and ethnic groups saying their financial situation is now better are not statistically significant.)

More than half of Americans who say their family’s financial situation is worse than it was a year ago (55%) expect their finances to recover within two years, with 12% saying they expect it will take less than a year for their financial situation to get back to where it was a year ago. About a quarter (26%) think it will take three to five years and 6% say it will be between six and ten years before their family’s financial situation is back to where it was a year ago. About one-in-ten adults who say their family’s financial situation has worsened (12%) say it will never get back to where it was. These answers vary little, if at all, across demographic groups.

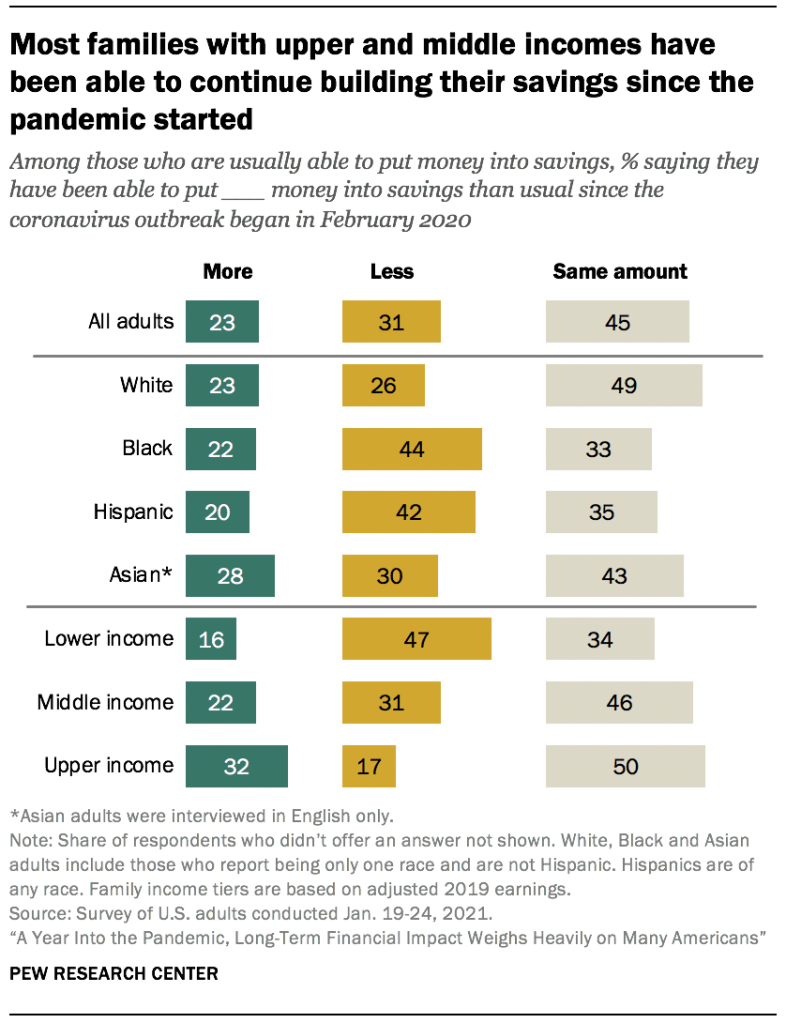

A plurality of lower-income adults are saving less during the pandemic

Many Americans were already struggling to save money before the coronavirus outbreak hit. Some 29% of adults overall say they are not usually able to put any money in savings. This is far more common among lower-income adults, 47% of whom say they are usually not able to save (vs. 25% of middle-income adults and just 8% of upper-income adults). About four-in-ten Black adults (38%) say they are usually not able to save, compared with 31% of Hispanic, 27% of White and 19% of Asian adults.

Among those who are typically able to put some money into savings, 45% say they are still saving about the same amount as they were before the pandemic, while 31% say they are saving less than usual and 23% say they are saving more.

Lower-income adults who usually put money into savings are far more likely than those in other income tiers to say they are now saving less than usual: 47% of lower-income adults say this, compared with 31% of those with middle incomes and 17% of those with upper incomes. By comparison, most middle-income and upper-income adults say they are saving about the same or even more than they were before the pandemic. Among those with middle incomes, 46% say they are saving the same and 22% are saving more than before. Even higher shares of those with upper incomes say this: half are saving about the same and 32% are saving more than before the pandemic.

Among those who are usually able to put money into savings, 44% of Black adults and 42% of Hispanics say they are saving less than they were before the pandemic, compared with 30% of Asian Americans and 26% of White adults. About half of White adults (49%) have continued putting the same amount into savings – higher than the share of Black (33%) and Hispanic (35%) adults who say the same.

Spending is down compared with before the pandemic for many Americans, but mostly because of a change in daily activities rather than concern about finances

About four-in-ten Americans (42%) say they have been spending less money than usual since the coronavirus outbreak began, and a similar share (39%) say they have been spending about the same; 19% say their spending has increased.

Upper-income adults (53%) are more likely than those with middle (43%) or lower incomes (34%) to say they have been spending less money since the pandemic began. About a quarter of those with lower incomes (26%) say they have been spending more, compared with 17% of middle-income adults and 11% of upper-income adults.

Two-thirds of those who are spending less say this is due to their daily activities changing because of coronavirus-related restrictions rather than worries about their personal finances (32%).

This is overwhelmingly the case among upper-income adults who are spending less, 86% of whom say it’s because of their activities changing. Seven-in-ten middle-income adults in this situation say the same. But among lower-income adults who have reduced their spending, more say it’s because they are worried about their personal finances (55%) rather than their daily activities changing (44%).

A majority of lower-income adults who are not retired say the pandemic will make it harder for them to achieve their long-term financial goals

Aside from how long they think it will take them to get back to where they were a year ago, many Americans say the economic impact of the coronavirus will have long-term repercussions for their financial future. About half of U.S. adults who are not retired (51%) say that, in the long run, the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak will make it at least somewhat harder for them to achieve their financial goals, with 16% saying it will make it a lot harder; 7% say the economic impact of the pandemic will make it a lot or somewhat easier for them to achieve their financial goals and 41% say it will be neither easier nor harder.

Lower-income adults are particularly likely to see the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak as a potential impediment to reaching their long-term financial goals. About six-in-ten non-retired adults in this group (58%) say that, in the long run, the pandemic will make it harder for them to achieve these goals, including a quarter who say it will make it a lot harder. Half of those with middle incomes and 41% with upper incomes say the pandemic will make it harder for them to reach their financial goals in the long run.

Long-term assessments are especially grim among those who say their finances have taken a hit in the last year. Fully three-quarters of non-retired adults who say their financial situation is now worse than it was a year ago believe the economic impact of the coronavirus outbreak will make it harder for them to achieve their financial goals in the long run. That’s in contrast to 35% of those who say their financial situation is better compared with a year ago and 50% of those who say it is about the same.

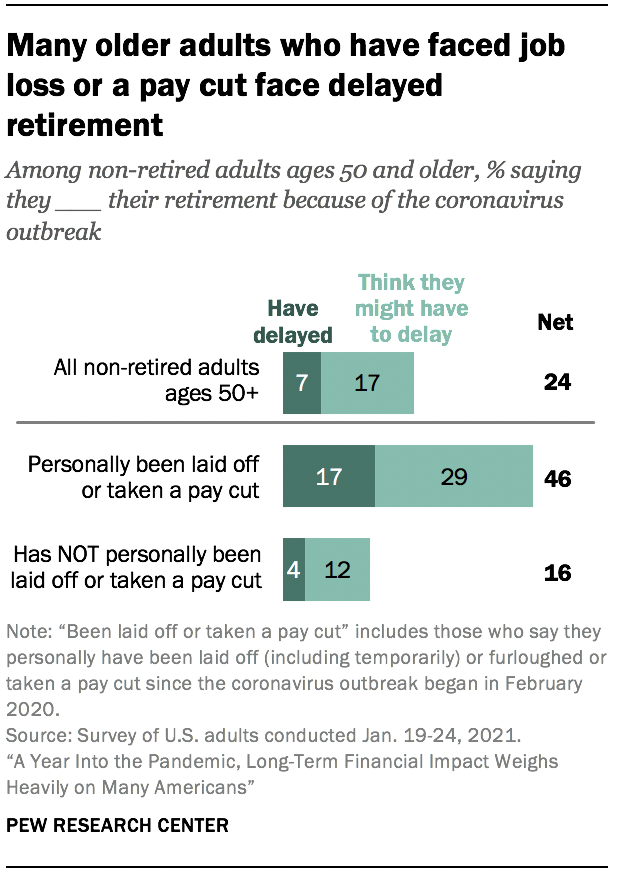

Many older Americans whose employment was affected during the coronavirus outbreak say they have or may have to delay their retirement

About a quarter of U.S. adults ages 50 and older who have not yet retired (24%) expect the coronavirus outbreak to affect their ability to retire. This includes 7% who say they have already delayed their retirement and an additional 17% think they might have to delay it.

Those who have personally been laid off or taken a pay cut since the pandemic began in February 2020 (27% of all adults 50 and older who are not retired) are much more likely to say they expect their retirement to be affected. More than four-in-ten (46%) say they either have already delayed or think they may have to delay their retirement because of the coronavirus outbreak, compared with just 16% who have not experienced a job loss or pay cut.

The shares of non-retired adults ages 50 and older who have delayed or expect to delay their retirement because of the coronavirus outbreak do not vary considerably across income levels or other demographic groups, including gender and educational attainment.

More than four-in-ten U.S. adults say they or someone in their household has lost a job or wages since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak

A third of U.S. adults say they or someone in their household has been laid off or lost a job (including being furloughed and temporarily laid off) since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, and 31% say they or someone in their household has taken a cut in pay due to reduced hours or demand for their work during this period. Overall, 44% say their household has experienced at least one of these since the pandemic began.

Experiences with job and wage loss during the pandemic have not been felt equally across demographic groups. Hispanic (58%) and Asian (54%) adults are more likely than White (40%) or Black (41%) adults to say they or someone in their household has either lost a job or taken a pay cut or both since the outbreak began in February 2020. And while a majority of adults younger than 30 (61%) say they or someone in their household has had these experiences, about half of adults ages 30 to 49 (51%) and smaller shares of those ages 50 to 64 (41%) and 65 and older (21%) say the same.

About half of lower-income adults (49%) say their household has experienced job or wage loss since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, as do 45% of middle-income adults. A far smaller – though substantial – share of upper-income adults (33%) say their household has had one or both of these experiences.

Many workers who lost wages during the pandemic are still earning less than they were before the coronavirus outbreak started. Among those who were working before the pandemic started and who personally experienced a pay cut since February 2020, about half (49%) say they are now earning less money than they did before the pandemic; 16% are now earning more money and 34% say they are earning about the same as before. This is consistent across most demographic groups, but employed adults ages 50 and older who experienced a pay cut since the outbreak began are more likely than those younger than 50 to say they’re earning less money than they did before (58% vs. 45%), while those in the younger group are more likely to say they’re earning more than they did before the pandemic (20% vs. 6%).

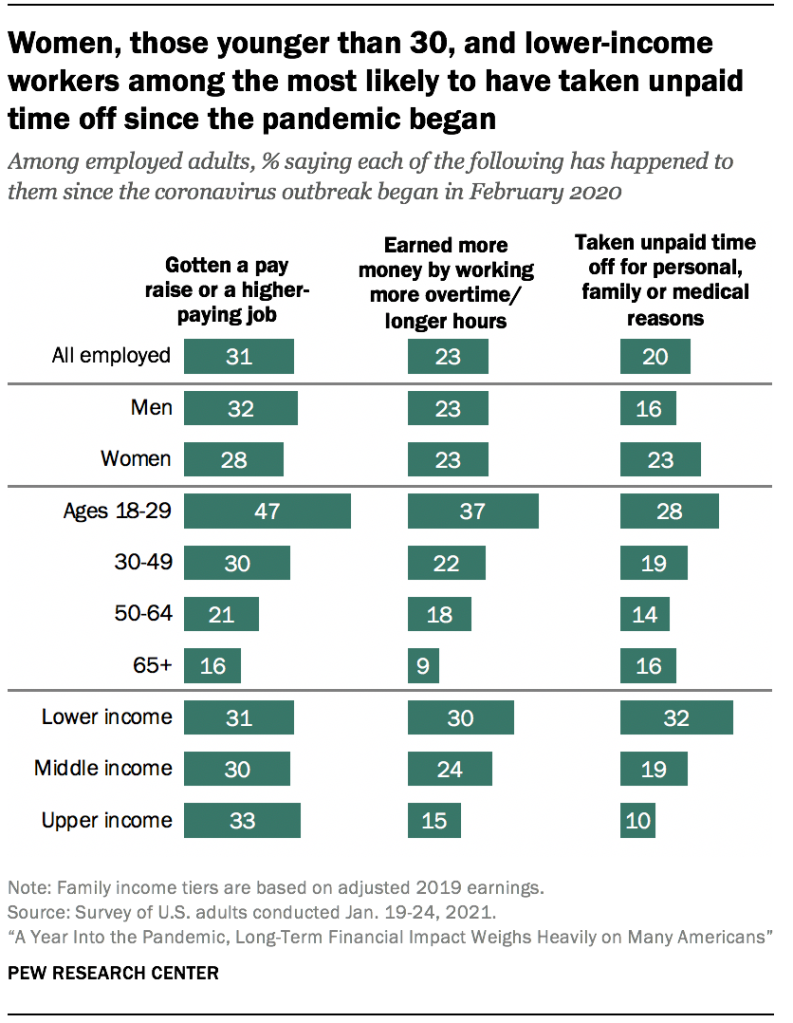

Lower-income workers are more likely than those with middle or upper incomes to have taken unpaid time off

In addition to being more likely than those with higher incomes to have experienced job or wage loss since February 2020, lower-income adults are also more likely to have taken unpaid time off from work for personal, family or medical reasons during this time. About a third of lower-income workers (32%) say they’ve had to do this during this period, compared with 19% of middle-income workers and 10% of those with upper incomes. According to previous research, workers on the lower ends of the wage distribution are less likely than those at the upper ends to have access to paid sick leave .

Three-in-ten lower-income workers say they have earned more money by working more overtime or longer hours since the coronavirus outbreak began; 24% of middle-income workers and 15% of those with upper incomes say this has happened. And about three-in-ten workers across income tiers say they have gotten a pay raise or a higher-paying job during this time.

Workers younger than 30 are far more likely than older workers to say they have gotten a pay raise or a higher-paying job since the coronavirus outbreak began (47% vs. 30% of workers ages 30 to 49, 21% of those ages 50 to 64 and 16% of those ages 65 and older). Younger workers are also more likely than older adults to say they have earned more money by working more overtime or longer hours and to say they have taken unpaid time off work for personal, family or medical reasons.

The survey also finds that, among employed adults, men are somewhat more likely than women to say they have gotten a pay raise or a higher-paying job since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak (32% vs. 28%). In turn, a larger share of employed women than men say they have taken unpaid time off work for personal, family or medical reasons since the beginning of the pandemic (23% vs. 16%).

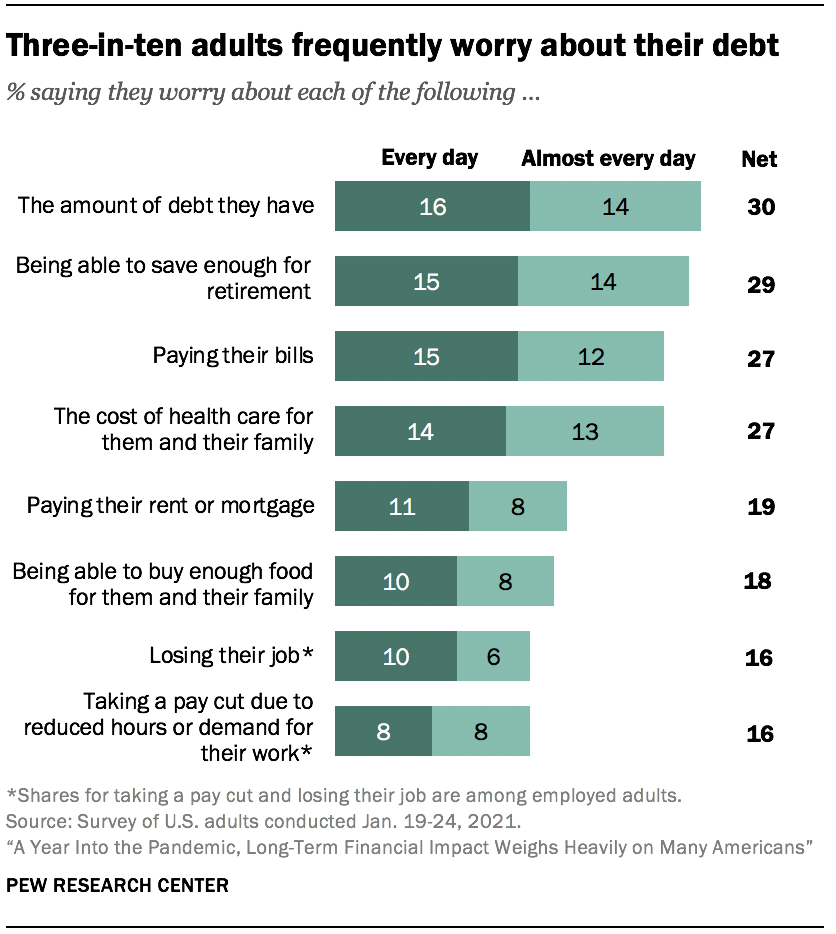

About three-in-ten Americans often worry about their debt and saving for retirement, but these concerns were higher in April

Roughly three-in-ten adults say they worry every day or almost every day about the amount of debt they have (30%) and being able to save enough for their retirement (29%). About a quarter worry about paying their bills and the cost of health care for them and their family (27% each). About one-in-five often worry about paying their rent or mortgage (19%) or being able to buy enough food for them and their family (18%). Some 16% of workers say they frequently worry that they will lose their job or take a pay cut due to reduced hours or demand for their work. About four-in-ten or more adults say they worry about each of these at least sometimes.

These concerns were more pressing earlier in the coronavirus outbreak than they are now. Higher shares in April 2020 said that they frequently worried about saving enough for retirement (38%), paying their bills (38%) or debt (36%), the cost of health care for them and their family (35%), taking a pay cut (29% of employed adults) and losing their job (23% of employed adults). (The items on paying rent or a mortgage and being able to buy enough food were not asked in April.) The decrease in concern since April was evident across income levels.

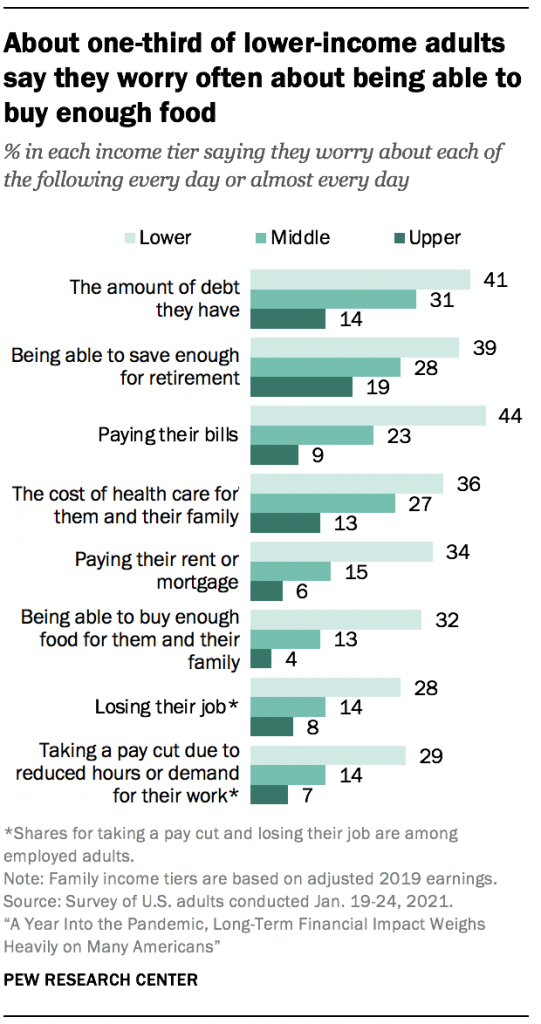

Lower-income adults are far more likely to worry often about each of these than middle- and upper-income adults. For example, 44% of those with lower incomes say they worry about paying their bills daily or almost daily, compared with 23% of middle-income adults and only 9% of those with upper incomes. And while about a third of lower-income adults say they worry about paying their rent or mortgage (34%) or being able to buy enough food (32%) daily or almost daily, 15% or less among middle-income and upper-income adults express similar concerns.

Adults living in households that have experienced job loss or a pay cut during the pandemic are more likely than those in households that have not to say they often worry about each of these concerns. For example, those who had their household’s job or pay affected are about twice as likely to say they worry daily or almost daily about being able to buy enough food for them and their families as those who were not affected (25% vs. 12%).

Black and Hispanic Americans (who have lower incomes on average than White Americans) are more likely than White adults to frequently have these worries. Meanwhile, Asian Americans are about equally as likely as White adults to say they often worry about their debt, saving for their retirement, the cost of health care, paying their bills and losing their job. However, they are more likely than White adults to say they worry about paying their rent or mortgage, being able to buy enough food and taking a cut in pay.

Adults 65 and older tend to be less worried about each of these concerns than their younger counterparts. In fact, the burden of some of these worries falls most heavily on those in the 30- to 49-year-old age group. For example, 25% of this group says they worry frequently about paying their rent or mortgage, compared with 20% of those ages 18 to 29, 19% of those 50 to 64 and 8% of those 65 and older.

Americans with disabilities – that is, those who say a disability or handicap keeps them from fully participating in work, school, housework or other activities – are also more likely than those without disabilities to say they often worry about each concern. For example, 36% of disabled Americans (who tend to have lower incomes than those without disabilities) say they often worry about the cost of health care for them and their family, while 25% of those without disabilities say the same.

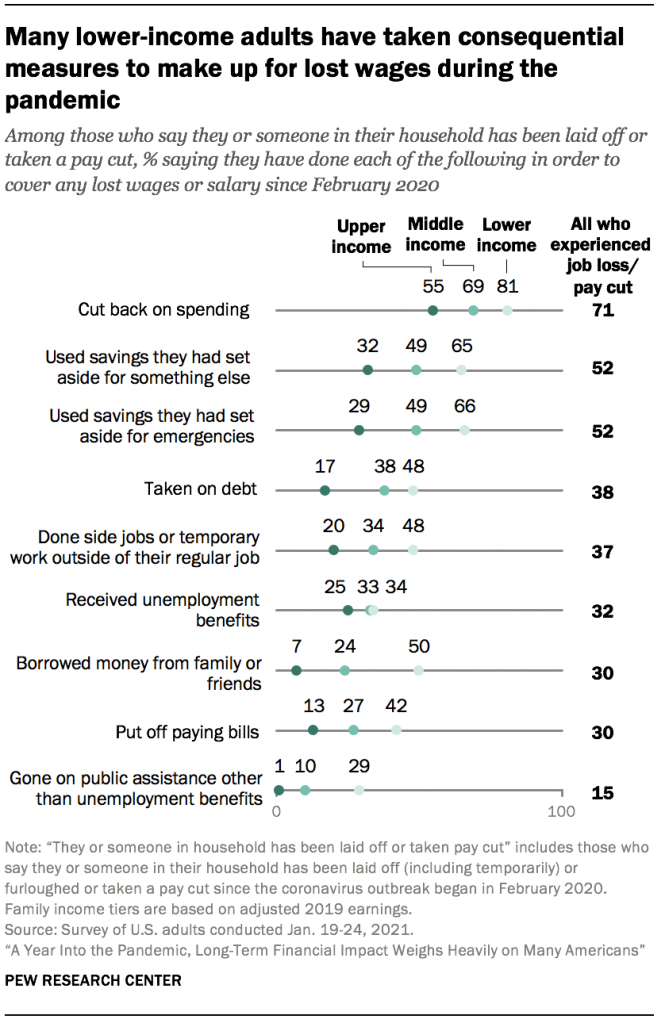

About half of lower-income adults in households that have lost income during the pandemic have taken on debt to help make ends meet

The survey also asked those who are in a household in which someone has been laid off or taken a pay cut since the pandemic began how they covered those lost wages or salaries. Cutting back on spending topped the list, with 71% saying they did this to help make up for their lost wages. Using savings was another common strategy, with about half of those who experienced a loss of wages saying they did this (52% say they used savings they had set aside for something else, and the same share say they used emergency savings). Smaller shares said they took on debt (38%), did side jobs or temporary work outside of their regular job (37%), received unemployment benefits (32%), borrowed money from family or friends (30%), put off paying bills (30%) or went on public assistance other than unemployment benefits (15%).

Lower-income adults whose households have experienced job or wage loss since the pandemic began are more likely than upper-income adults to say they have taken each of these steps. In fact, many in this group have taken consequential measures, such as borrowing money from family or friends (50%), taking on debt (48%) and putting off paying bills (42%).

Among upper-income adults whose household experienced a loss of income, 55% say they cut back on spending as a way to compensate. Much smaller shares (about a third or less) say they have taken each of the other measures asked about in the survey. Few said they have had to take the types of consequential measures that many lower-income adults rely on, such as taking on debt (17% of upper-income adults), putting off paying bills (13%) or borrowing from friends or family (7%).

Among households experiencing loss of income, reports of using unemployment benefits are more common among those who say they or someone in their household lost a job (permanently or temporarily). 3 Overall, 39% of those who lost a job or had someone in their household who did say they received unemployment benefits, compared with 11% of those in households that experienced a pay cut but no job loss (even while many people who had their hours cut during the pandemic are eligible ). Lower-, middle- and upper-income adults who experienced job loss are about equally likely to say they received this type of benefit.

About two-in-ten of those from households that experienced a job loss (19%) say they went on public assistance other than unemployment benefits, compared with 5% of those who experienced a pay cut but no job loss. Among the households who experienced job loss, 33% of lower-income adults say they went on this kind of public assistance, compared with 13% of middle-income adults and just 2% of upper-income adults.

Most lower-income adults who expect a stimulus payment say they will use it to pay for bills or essentials

As the economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic continued in late 2020, Congress passed a second stimulus bill to help ease the financial hardships many Americans have faced. About half of U.S. adults who have received or expect to receive a payment from the federal government as part of the stimulus package (52%) say they will use a majority of these funds to pay bills or for something essential they or their family needs. Another 22% say they will save it; 16% say they will use it to pay off debt; and 10% say they will use it for something else, including for something non-essential they or their family wants, charitable donations, helping friends and family, supporting local businesses, or some combination.

The way Americans are planning to use payments from the second coronavirus aid package parallel what those who received or expected to receive a payment early in the pandemic said about how they planned to use those funds .

Lower-income adults are the most likely to say they will use a majority of the money to pay for bills or for something essential among those expecting a payment in each income group; 66% say this, compared with 49% of middle-income adults and 30% of those with upper incomes. About a third of adults with upper incomes (35%) say they expect to save most of it; 24% of those with middle incomes and 12% of lower-income adults say the same.

Plans for the stimulus payments vary across racial and ethnic groups and educational attainment. About six-in-ten Black and Hispanic adults (61% each) say they will use a majority of the money to pay for bills or essentials, compared with 48% of White adults and 51% of Asian adults. White and Asian adults are more likely than Black and Hispanic adults to say they will save it (24% and 28% vs. 16% and 15% respectively). Six-in-ten adults with a high school diploma or less education say they will use a majority of the money to pay for bills or essentials; 53% of those with some college, and 40% with a bachelor’s degree or more education say the same.

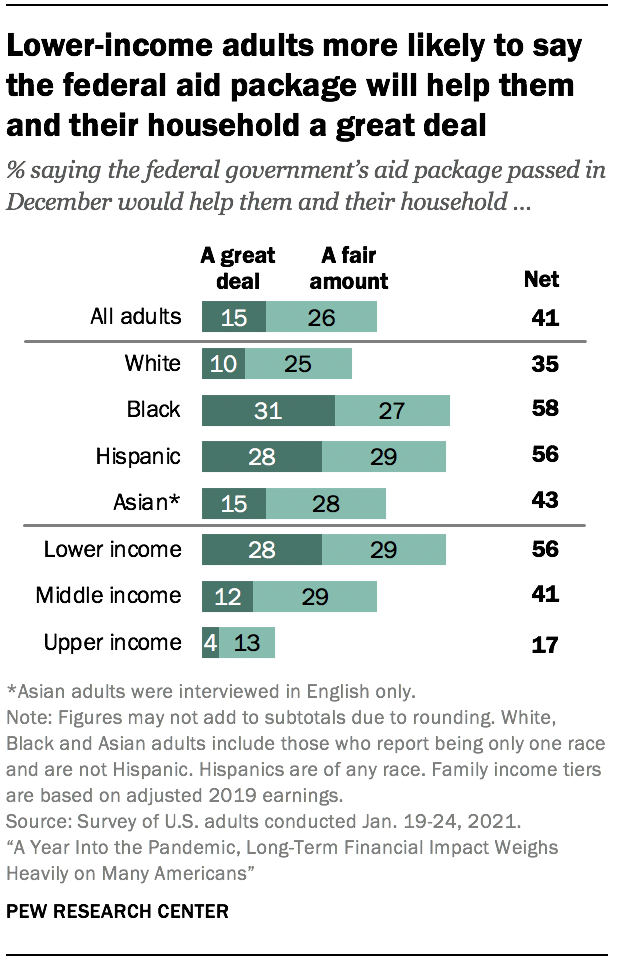

About four-in-ten Americans say the federal government’s aid package will help them and their household at least a fair amount

Overall, about four-in-ten adults (41%) say the aid package passed by the federal government in December 2020 would help them and their household a great deal or a fair amount. Majorities say the aid package will help small businesses (54%), large businesses (57%), and unemployed people (61%) at least a fair amount. This is a notable shift in confidence from early in the pandemic when about seven-in-ten or more Americans said the aid package passed in March would help large and small businesses and unemployed people; 46% said the earlier aid package would help them and their household.

A majority of adults with lower incomes (56%) say the aid package will help them and their household at least a fair amount, with 28% saying it would help them a great deal . This compares to 41% of middle-income adults and 17% of those with upper incomes who say it will help them at least a fair amount.

Among other key demographic groups, adults under age 30, Black and Hispanic adults, and those without a college degree are among the most likely to say the aid package will help them and their household at least a fair amount. Over half of Black and Hispanic adults say the aid package will help them and their households (58% and 56% respectively) at least a fair amount, with significant shares saying it will help them a great deal (31% and 28% respectively). Smaller shares of White (35%) and Asian adults (43%) say it will help them a great deal or a fair amount.

Half of adults under age 30 say the federal aid package will help them and their households at least a fair amount; 43% of those ages 30 to 49, 39% of those ages 50 to 64, and 33% of adults ages 65 and older say the same. Adults with a high school diploma or less education are more likely to say the federal aid package will help them and their households at least a fair amount (50%) than those with some college experience (42%) and those with a bachelor’s degree or more education (31%).

No clear consensus on who should have the greatest responsibility for making sure people can meet their basic economic needs during the coronavirus outbreak

When asked who should have the greatest responsibility for making sure people can meet their basic economic needs during the coronavirus outbreak, 45% point to the federal government, while a third say people themselves or their families should have the greatest responsibility. Smaller shares say state or local governments (12%), charitable organizations (2%), or another source (6%), most often a combination of all of these, should be most responsible.

There is a sharp partisan divide on this issue. About six-in-ten Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic party (61%) say the federal government should have the greatest responsibility, and just 18% say it should be people themselves or their families. Among Republicans and Republican leaners, 28% point to the federal government, while a larger share (51%) say people themselves or their families should have the greatest responsibility for making sure they can meet their basic economic needs during the pandemic.

Liberal Democrats are the most likely to point to the federal government as having the greatest responsibility to ensure people can meet their basic economic needs during the coronavirus outbreak. About seven-in-ten liberal Democrats (72%) say this, compared with 52% of conservative or moderate Democrats, 36% of moderate or liberal Republicans, and an even smaller share of conservative Republicans (23%). In turn, conservative Republicans are the most likely to say it is people themselves or their families who have this responsibility; 57% say this compared with 41% of moderate or liberal Republicans, 25% of moderate or conservative Democrats and just 11% of liberal Democrats.

- Family incomes are based on 2019 earnings and adjusted for differences in purchasing power by geographic region and for household sizes. Middle income is defined here as two-thirds to double the median annual family income for all panelists on the American Trends Panel . Lower income falls below that range; upper income falls above it. Throughout this report, references to adults who have lost a job or been laid off include those who say they were furloughed or temporarily laid off. ↩

- For more details, see the Methodology section of the report. ↩

- This includes households that experienced both a job loss and a pay cut, as well as those that experienced only a job loss. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- COVID-19 & the Economy

- Recessions & Recoveries

- Unemployment

How Americans View the Coronavirus, COVID-19 Vaccines Amid Declining Levels of Concern

Online religious services appeal to many americans, but going in person remains more popular, about a third of u.s. workers who can work from home now do so all the time, how the pandemic has affected attendance at u.s. religious services, mental health and the pandemic: what u.s. surveys have found, most popular, report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 81

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Consumer Behavior

Health vs. wealth: how the pandemic changed our priorities, shopping, sharing, and savoring: balancing health and wealth..

Posted June 6, 2022 | Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

- The COVID-19 pandemic has uniquely impacted the value we place on both money and materialism.

- The pandemic produced materialistic values, such as consuming media, anxiety, stress, loneliness, and depressed mood.

- Contrary to expectations, focus on money actually decreased during the course of the pandemic.

During the early months of 2020, many people were reminded through both personal experience and global news reports of the critical importance of maintaining good health. As the pandemic progressed, we began to ask: but at what cost? We recognized that all the money in the world cannot buy good health, although good insurance helps. Flash forward several years, and we have clarified our priorities through our evolving practices of saving, sharing, and spending. As many people suspected, the COVID-19 pandemic has uniquely impacted the value we place on both money and materialism .

Shopping, Sharing, and Savoring

Olaya Moldes et al. (2022) examined how people changed their priorities over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. 1 Focusing largely on money and materialism, they made some interesting observations that demonstrate how privately evolving priorities can impact public spending behavior.

Balancing Health and Wealth

Moldes et al. note that the pandemic produced an increase in the types of factors that usually accompany an endorsement of materialistic values, such as consuming more media, anxiety , stress , loneliness , and depressed mood. Although they found that increases in media consumption, anxiety, and stress predicted levels of materialism to an extent, they found such effects to be limited. Contrary to expectations, they found that our focus on money actually decreased during the course of the pandemic.

Moldes et al. recognized a research-based definition of materialism as “individual differences in people's long-term endorsement of values, goals , and associated beliefs that center on the importance of acquiring money and possessions that convey status” (Dittmar et al., 2014). They note that wealth and consumption are thought to be tied to personal achievement and happiness —even though materialism has been linked to lower well-being and higher degrees of compulsive buying. They also note that research shows that advocating materialistic values is influenced by a higher amount of media consumption as well as social and personal insecurities and negative emotions.

But, overall, Moldes et al. explained that their observed decrease in the importance people placed on money might be due to the COVID-19–triggered alterations in the values people held—which were in the opposite direction than were predicted. They also found that, contrary to expectations, people decreased the level of importance they placed on economic resources during the outbreak, despite experiencing more factors that facilitate and promote materialism. They note that these results may be due to prioritizing personal health and well-being, or emerging “collective social identities that promote social solidarity and cooperation ,” that have previously been observed in times of emergencies and environmental disasters—thus decreasing our focus on material and economic resources.

Resignation and Revival

Moldes et al. note that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the ways in which people think about money. Commenting on what has been dubbed “The Great Resignation” observed in the United States and the United Kingdom, they note that exiting the workforce has been likely fueled by reflecting on life priorities during the pandemic.

One interesting point, however, was that, apparently, during the pandemic, people found money to be less important, despite an increase in factors that endorse materialism. Moldes et al. observed an overall decrease in reported pandemic shopping behaviors, but a higher instance of purchasing as a coping mechanism to deal with negative emotions and in pursuit of well-being.

As we move forward seeking to prioritize both health and wealth, we have gained a greater appreciation of the ageless adage that the most precious things in life are free.

1. Moldes, Olaya, Denitsa Dineva, and Lisbeth Ku. 2022. “Has the Covid‐19 Pandemic Made Us More Materialistic? The Effect of Covid‐19 and Lockdown Restrictions on the Endorsement of Materialism.” Psychology & Marketing, January. doi:10.1002/mar.21627.

Wendy L. Patrick, J.D., Ph.D., is a career trial attorney, behavioral analyst, author of Red Flags , and co-author of Reading People .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Financial life during the COVID-19 pandemic—an update

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken root in nearly every country on the globe, upending personal and economic lives. Six months into the crisis, some countries have managed to control new cases, while in others the spread remains rampant. While many countries have reopened their economies, allowing a cautious return to work, play, and economic life, the pandemic seems likely to remain a fact of life for the foreseeable future.

Since the end of March 2020, McKinsey has undertaken Financial Insights Pulse Surveys of household financial decision makers across the globe to understand the impact of COVID-19 on financial well-being, and on stated changes in financial services preferences. Surveys are conducted on-line in local languages and are repeated bi-weekly or monthly, depending on the region. Results are sampled on a country basis for a representative balance of financial decision makers, based on variables including age and socioeconomic status. Survey size is between 500 and 1,000 for each country in each month.

This article is an update on the surveys McKinsey conducted in April and May 2020 to assess the immediate effects of COVID-19 on financial sentiment, behaviors, needs, and expectations among household financial decision makers around the globe. The survey covers 30 countries, together accounting for 70 percent of the global population, and 83 percent of all COVID-19 cases reported as of June 30 (see sidebar).

As of mid-June, across the globe, decision makers’ assessments of the health of their national economies were negative, but for most countries they had improved from mid-May. More notably, reported future expectations for the next three months improved meaningfully from May to June across almost all countries.

More concrete markers of financial health remain tenuous. Household financial decision makers across the globe continue to report decreases in income and savings ranging from 30 percent to 80 percent. And in most countries, between 20 percent and 60 percent of decision makers say they fear for their jobs.

In other areas, customer views of banks’ service quality and how they will engage with banks changed little since the May survey. In this stressed environment, what customers continue to want most from their banks is tangible support on credit terms—waiving late fees, reducing minimum payments, or permission to skip a loan payment. At the same time, use of cash is decreasing and digital forms of payment are increasing, perhaps as people quarantine or avoid those interactions more likely to transmit disease. Against this backdrop, in most countries consumers indicate that banks are meeting their expectations—but generally not exceeding them, at least on a net basis.

Following are 10 survey observations focused on a subset of 16 countries, selected for their global and regional economic significance, and the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic on their populations.

Would you like to learn more about our Financial Services Practice ?

1. financial decision makers feel their country economies and personal finances are weak, but sentiment has risen since may.

Measures of economic sentiment improved somewhat in the June survey, but household financial decision makers around the world continue to report that their countries’ current economies are weak (Exhibit 1). Net sentiment improved by 7 percentage points or more in Brazil, the U.S., Italy, Spain, and Turkey.

Household financial decision makers also tended to rate their personal financial situations as weak, with very little change from May. However, in China, the US, and the UK, respondents see their personal finances, on a net basis, as slightly positive.

Notably, in all countries, respondents assessed the current state of their economies more negatively than they viewed their own financial situations. This difference was most extreme in the UK, followed by Brazil, Italy, and the US. Ratings of personal financial situations were most in line with views of the economy in China, India, and Indonesia.

2. Each month, more consumers expect the impact of COVID-19 on the economy will last a year or longer

We also asked decision makers to look ahead and call the duration of the downturn (Exhibit 2). In April, more than 60 percent of respondents in most of the 16 countries expected the impact of COVID-19 to last at least a year or so (India and Indonesia were the exceptions). By May, the proportion had risen to over 80 percent for many economies, including Western Europe and the UK. And in June, over 90 percent of respondents within many European countries expected the downturn to last at least a year. Outlooks deteriorated most in South Africa, Mexico, and Indonesia. Countries in Asia-Pacific, including China, India, and Indonesia, are generally more optimistic.

3. Respondents in most countries expect the economy to improve in three months, with more mixed personal financial outlooks

When asked to project the state of the economy and of their personal financial situations three months into the future, in April respondents in most countries thought both would grow worse (Exhibit 3). Decision makers in India, the US, South Africa, and China were more optimistic, and thought that at least their own personal financial situations would improve.

In May, decision makers in many countries had grown more optimistic. Respondents in just four countries—France, Germany, Russia and the UK—continued to think that both the economy and their own financial situations would get worse.

Expectations continued to improve through June, when only financial decision makers in France expected deterioration in both the economy and personal financial situations over the next three months. Decision makers in all examined countries outside of Western Europe and Chile expected that both the economy and their own personal financial situations would improve.

4. Job security concerns remain high—and over half of people concerned about their jobs also have less than four months of savings

To examine the direct impact of the pandemic on consumers, our surveys explore concerns over employment, reported financial behaviors, and use of financial services products.

Job security concerns remained roughly constant from May to June, although they varied widely by country (Exhibit 4). In Germany, 9 percent of household financial decision makers expressed concerns over job security, while in India, Chile, and South Africa that fraction was over 50 percent. Furthermore, in most countries more than half of people with job security concerns held savings to cover less than four months’ worth of expenses.

5. Respondents continue to report reduced income, savings, and spending

We also surveyed decision makers on their household income, savings, and spending over the preceding month (Exhibit 5). In June, respondents across all countries reported decreased income and savings on a net basis. The most drastic reductions were found in South Africa and Indonesia, where over 70 percent of respondents reported declines in both income and savings.

Household spending presents a more mixed picture. In wealthier countries such as the US, Canada, and the UK, more decision makers reported reducing spending than increasing spending. For example, in Canada, 51 percent of respondents have reduced household spending while only 19 percent have said they increased spending. On the other hand, in countries in Asia-Pacific and South America such as Indonesia and Brazil, more consumers claimed to have increased spending than decreased. In fact, 46 percent of respondents in Indonesia actually increased spending while only 25 percent claimed to have decreased spending.

6. Cash use has decreased while remote payments have increased

We also asked about changes in decision makers’ banking patterns during the COVID-19 crisis, and found that reliance on cash payments has decreased substantially in most countries examined (Exhibit 6). From May to June, indicated forms of payment changed little from the April survey. However, in some countries where economies began to reopen in May—most notably Italy, Spain and the US—the use of cash increased. In contrast, in Mexico, consumers reported a decrease of 8 percent in the use of cash.

7. Missed loan payments and plans to change asset allocation vary widely by country, with some patterns in high-income economies

We also probed a broad range of additional financial behaviors, including, for example, missed past loan payments, and plans for asset allocation (Exhibit 7). Rates of missed mortgage payments over the past month vary by country and region, but across high-income countries, the proportion of survey participants that noted having missed a mortgage payment grows roughly proportionally with the share of people reporting weak personal financial situations.

Intent to change asset allocation over the coming three months also varies widely across countries. Decision makers in emerging markets were more likely to make changes than those in Europe, the US, and Canada. Across high-income countries, the fraction of people reporting plans to change asset allocation is roughly proportional to the fraction who deemed the economy to be weak.

8. In most countries, respondents indicated banks were at least meeting expectations—with several exceptions

The survey also explored decision makers’ current relationships with their banks (Exhibit 8). In June, in most countries most respondents indicated that their banks were at least meeting expectations during the COVID-19 crisis. Performance above expectations was highest in Turkey and India, and lowest in Chile and Russia. Sentiment in most countries was largely unchanged from May. However, the US and Turkey both saw a significant gains in satisfaction with bank performance, with respective net increases of 9 percent and 8 percent.

Financial decision-maker sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective

9. in this stressed environment, what customers continue to want most from their banks is tangible support on credit terms.

When asked how their banks could provide support during this period of uncertainty, consumers indicated a wide range of needs—creating service and support opportunities (Exhibit 9). Again, opinions varied little between May and June. Customers were nearly unanimous in desiring waivers on late fees, and in a number of countries expressed a desire for reduced minimum payments, as well as forbearance on loans and mortgages. Higher limits on contactless payments were also in demand in Western European countries. In June, we also found an increase in the number of countries in which decision makers rank “improved website that enable seamless transactions across all banking services” in the top three considerations.

In China, where mobile and digital banking are highly evolved, consumers instead requested education on their banks’ mobile and online tools, and 50 percent called for improvements to banks’ web sites.

10. Consumers indicate they will use digital banking more once the crisis is over, but with significant variation by country

Looking ahead to a potential next normal, consumers expect to increase their reliance on remote banking, but with significant variation across countries (Exhibit 10). The preference was especially pronounced in South Africa, Brazil, and India as a net gain of over 30 percent of consumers indicated they will increase their use of online and mobile banking once “normal life” resumes. Even in countries with mature digital banking such as China, roughly 40 percent of respondents said they would make greater use of online and mobile services. In the US and Europe, the expected shift to online and mobile banking services is more muted.

In addition to the dozen countries summarized above, we have developed detailed surveys on an additional 14 countries, which will also be regularly updated. In coming months, we will conduct further surveys on the evolution of economic and financial expectations, perceptions, and behaviors of financial decision makers in all these countries.

Or click directly to see one of these countries in our survey: Australia , Brazil , Canada , Chile , China , Egypt , France , Germany , Greece , India , Indonesia , Italy , Japan , Kenya , Malaysia , Mexico , Morocco , Nigeria , Pakistan , Romania , Russia , Saudi Arabia , Singapore , South Africa , Spain , Sweden , Turkey , United Arab Emirates , the United Kingdom , or the United States .

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Reshaping retail banking for the next normal

Search form

Research essay: should we save lives — or save the economy.

The COVID-19 crisis puts all policymakers in a difficult position. In addition to the great uncertainty about the parameters of the pandemic and about the short-term and long-term consequences of the economic slump, there is an ethical dilemma: how to balance the value of saving human lives against the value of preserving people’s livelihoods. In the United States, the debate has been raging between those who say “the cure cannot be worse than the disease,” and those who say “we are not going to put a dollar figure on human life.”

Whether they like it or not, policymakers must address this difficult trade-off. In theory, separating every person from everyone else for two or three weeks would immediately stop the infection spread at little economic cost. This is totally impractical, but less extreme lockdown measures observed in many countries do reduce the reproduction rate of the pandemic to such low numbers that this, actually, would fully extinguish the pandemic within two or three months. It is also possible, under a more lenient approach, to keep the pandemic under control by a stop-and-go policy of repeated lockdown episodes of a few weeks each until a vaccine is found. The problem is: Are all these measures worse than the health crisis itself?

When Princeton students were sent back home, just before the spring break, I was intrigued by this exceptional situation and built a model on a simple Excel spreadsheet, first for my own curiosity, but also as a possible teaching tool for my Woodrow Wilson School class on the microeconomic evaluation of public policy. Several friends and colleagues have helped me improve it, including my daughter, a physicist.