Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

You can think of the first sentence of your essay as you would a fishing hook. It grabs your reader and allows you reel the person into your essay and your train of thought. The hook for your essay can be an interesting sentence that captures a person's attention, it can be thought-provoking, or even, entertaining.

The hook for your essay often appears in the first sentence . The opening paragraph includes a thesis sentence . Some popular hook choices can include using an interesting quote, a little-known fact, famous last words, or a statistic .

A quote hook is best used when you are composing an essay based on an author, story, or book. It helps establish your authority on the topic and by using someone else's quote, you can strengthen your thesis if the quote supports it.

The following is an example of a quote hook: "A man's errors are his portals of discovery." In the next sentence or two, give a reason for this quote or current example. As for the last sentence (the thesis) : Students grow more confident and self-sufficient when parents allow them to make mistakes and experience failure.

General statement

By setting the tone in the opening sentence with a uniquely written general statement of your thesis, the beauty is that you get right to the point. Most readers appreciate that approach.

For example, you can start with the following statement: Many studies show that the biological sleep pattern for teens shifts a few hours, which means teens naturally stay up later and feel alert later in the morning. The next sentence, set up the body of your essay, perhaps by introducing the concept that school days should be adjusted so that they are more in sync with the teenager's natural sleep or wake cycle. As for the last sentence (the thesis) : If every school day started at ten o'clock, many students would find it easier to stay focused.

By listing a proven fact or entertaining an interesting statistic that might even sound implausible to the reader, you can excite a reader to want to know more.

Like this hook: According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics , teens and young adults experience the highest rates of violent crime. Your next sentence can set up the argument that it's dangerous for teenagers to be on the streets at late hours. A fitting thesis statement might read: Parents are justified in implementing a strict curfew, regardless of a student's academic performance.

The Right Hook for Your Essay

The good news about finding a hook? You can find a quote, fact, or another type of hook after you determine your thesis. You can accomplish this with a simple online search about your topic after you've developed your essay .

You can nearly have the essay finished before you revisit the opening paragraph. Many writers polish up the first paragraph after the essay is completed.

Outlining the Steps for Writing Your Essay

Here's an example of the steps you can follow that help you outline your essay.

- First paragraph: Establish the thesis

- Body paragraphs: Supporting evidence

- Last paragraph: Conclusion with a restatement of the thesis

- Revisit the first paragraph: Find the best hook

Obviously, the first step is to determine your thesis. You need to research your topic and know what you plan to write about. Develop a starting statement. Leave this as your first paragraph for now.

The next paragraphs become the supporting evidence for your thesis. This is where you include the statistics, opinions of experts, and anecdotal information.

Compose a closing paragraph that is basically a reiteration of your thesis statement with new assertions or conclusive findings you find during with your research.

Lastly, go back to your introductory hook paragraph. Can you use a quote, shocking fact, or paint a picture of the thesis statement using an anecdote? This is how you sink your hooks into a reader.

The best part is if you are not loving what you come up with at first, then you can play around with the introduction. Find several facts or quotes that might work for you. Try out a few different starting sentences and determine which of your choices makes the most interesting beginning to your essay.

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- How To Write an Essay

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- How to Structure an Essay

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- What Is Expository Writing?

- How to Start a Book Report

- Writing a Lead or Lede to an Article

- How to Write a Response Paper

- Clerc Center | PK-12 & Outreach

- KDES | PK-8th Grade School (D.C. Metro Area)

- MSSD | 9th-12th Grade School (Nationwide)

- Gallaudet University Regional Centers

- Parent Advocacy App

- K-12 ASL Content Standards

- National Resources

- Youth Programs

- Academic Bowl

- Battle Of The Books

- National Literary Competition

- Youth Debate Bowl

- Youth Esports Series

- Bison Sports Camp

- Discover College and Careers (DC²)

- Financial Wizards

- Immerse Into ASL

- Alumni Relations

- Alumni Association

- Homecoming Weekend

- Class Giving

- Get Tickets / BisonPass

- Sport Calendars

- Cross Country

- Swimming & Diving

- Track & Field

- Indoor Track & Field

- Cheerleading

- Winter Cheerleading

- Human Resources

- Plan a Visit

- Request Info

- Areas of Study

- Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- American Sign Language

- Art and Media Design

- Communication Studies

- Data Science

- Deaf Studies

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Programs

- Educational Neuroscience

- Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Information Technology

- International Development

- Interpretation and Translation

- Linguistics

- Mathematics

- Philosophy and Religion

- Physical Education & Recreation

- Public Affairs

- Public Health

- Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Theatre and Dance

- World Languages and Cultures

- B.A. in American Sign Language

- B.A. in Art and Media Design

- B.A. in Biology

- B.A. in Communication Studies

- B.A. in Communication Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Deaf Studies

- B.A. in Deaf Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Early Childhood Education

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Elementary Education

- B.A. in English

- B.A. in Government

- B.A. in Government with a Specialization in Law

- B.A. in History

- B.A. in Interdisciplinary Spanish

- B.A. in International Studies

- B.A. in Interpretation

- B.A. in Mathematics

- B.A. in Philosophy

- B.A. in Psychology

- B.A. in Psychology for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Social Work (BSW)

- B.A. in Sociology

- B.A. in Sociology with a concentration in Criminology

- B.A. in Theatre Arts: Production/Performance

- B.A. or B.S. in Education with a Specialization in Secondary Education: Science, English, Mathematics or Social Studies

- B.S in Risk Management and Insurance

- B.S. in Accounting

- B.S. in Accounting for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Biology

- B.S. in Business Administration

- B.S. in Business Administration for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Information Technology

- B.S. in Mathematics

- B.S. in Physical Education and Recreation

- B.S. In Public Health

- General Education

- Honors Program

- Peace Corps Prep program

- Self-Directed Major

- M.A. in Counseling: Clinical Mental Health Counseling

- M.A. in Counseling: School Counseling

- M.A. in Deaf Education

- M.A. in Deaf Education Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Cultural Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Language and Human Rights

- M.A. in Early Childhood Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Early Intervention Studies

- M.A. in Elementary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in International Development

- M.A. in Interpretation: Combined Interpreting Practice and Research

- M.A. in Interpretation: Interpreting Research

- M.A. in Linguistics

- M.A. in Secondary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Sign Language Education

- M.S. in Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- M.S. in Speech-Language Pathology

- Master of Social Work (MSW)

- Au.D. in Audiology

- Ed.D. in Transformational Leadership and Administration in Deaf Education

- Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology

- Ph.D. in Critical Studies in the Education of Deaf Learners

- Ph.D. in Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Ph.D. in Linguistics

- Ph.D. in Translation and Interpreting Studies

- Ph.D. Program in Educational Neuroscience (PEN)

- Individual Courses and Training

- Summer On-Campus Courses

- Summer Online Courses

- Certificates

- Certificate in Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Educating Deaf Students with Disabilities (online, post-bachelor’s)

- American Sign Language and English Bilingual Early Childhood Deaf Education: Birth to 5 (online, post-bachelor’s)

- Peer Mentor Training (low-residency/hybrid, post-bachelor’s)

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Certificate

- Online Degree Programs

- ODCP Minor in Communication Studies

- ODCP Minor in Deaf Studies

- ODCP Minor in Psychology

- ODCP Minor in Writing

- Online Degree Program General Education Curriculum

- University Capstone Honors for Online Degree Completion Program

Quick Links

- PK-12 & Outreach

- NSO Schedule

Guide to Writing Introductions and Conclusions

202.448-7036

First and last impressions are important in any part of life, especially in writing. This is why the introduction and conclusion of any paper – whether it be a simple essay or a long research paper – are essential. Introductions and conclusions are just as important as the body of your paper. The introduction is what makes the reader want to continue reading your paper. The conclusion is what makes your paper stick in the reader’s mind.

Introductions

Your introductory paragraph should include:

1) Hook: Description, illustration, narration or dialogue that pulls the reader into your paper topic. This should be interesting and specific.

2) Transition: Sentence that connects the hook with the thesis.

3) Thesis: Sentence (or two) that summarizes the overall main point of the paper. The thesis should answer the prompt question.

The examples below show are several ways to write a good introduction or opening to your paper. One example shows you how to paraphrase in your introduction. This will help you understand the idea of writing sequences using a hook, transition, and thesis statement.

» Thesis Statement Opening

This is the traditional style of opening a paper. This is a “mini-summary” of your paper.

For example:

» Opening with a Story (Anecdote)

A good way of catching your reader’s attention is by sharing a story that sets up your paper. Sharing a story gives a paper a more personal feel and helps make your reader comfortable.

This example was borrowed from Jack Gannon’s The Week the World Heard Gallaudet (1989):

Astrid Goodstein, a Gallaudet faculty member, entered the beauty salon for her regular appointment, proudly wearing her DPN button. (“I was married to that button that week!” she later confided.) When Sandy, her regular hairdresser, saw the button, he spoke and gestured, “Never! Never! Never!” Offended, Astrid turned around and headed for the door but stopped short of leaving. She decided to keep her appointment, confessing later that at that moment, her sense of principles had lost out to her vanity. Later she realized that her hairdresser had thought she was pushing for a deaf U.S. President. Hook: a specific example or story that interests the reader and introduces the topic.

Transition: connects the hook to the thesis statement

Thesis: summarizes the overall claim of the paper

» Specific Detail Opening

Giving specific details about your subject appeals to your reader’s curiosity and helps establish a visual picture of what your paper is about.

» Open with a Quotation

Another method of writing an introduction is to open with a quotation. This method makes your introduction more interactive and more appealing to your reader.

» Open with an Interesting Statistic

Statistics that grab the reader help to make an effective introduction.

» Question Openings

Possibly the easiest opening is one that presents one or more questions to be answered in the paper. This is effective because questions are usually what the reader has in mind when he or she sees your topic.

Source : *Writing an Introduction for a More Formal Essay. (2012). Retrieved April 25, 2012, from http://flightline.highline.edu/wswyt/Writing91/handouts/hook_trans_thesis.htm

Conclusions

The conclusion to any paper is the final impression that can be made. It is the last opportunity to get your point across to the reader and leave the reader feeling as if they learned something. Leaving a paper “dangling” without a proper conclusion can seriously devalue what was said in the body itself. Here are a few effective ways to conclude or close your paper. » Summary Closing Many times conclusions are simple re-statements of the thesis. Many times these conclusions are much like their introductions (see Thesis Statement Opening).

» Close with a Logical Conclusion

This is a good closing for argumentative or opinion papers that present two or more sides of an issue. The conclusion drawn as a result of the research is presented here in the final paragraphs.

» Real or Rhetorical Question Closings

This method of concluding a paper is one step short of giving a logical conclusion. Rather than handing the conclusion over, you can leave the reader with a question that causes him or her to draw his own conclusions.

» Close with a Speculation or Opinion This is a good style for instances when the writer was unable to come up with an answer or a clear decision about whatever it was he or she was researching. For example:

» Close with a Recommendation

A good conclusion is when the writer suggests that the reader do something in the way of support for a cause or a plea for them to take action.

202-448-7036

At a Glance

- Quick Facts

- University Leadership

- History & Traditions

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Our 10-Year Vision: The Gallaudet Promise

- Annual Report of Achievements (ARA)

- The Signing Ecosystem

- Not Your Average University

Our Community

- Library & Archives

- Technology Support

- Interpreting Requests

- Ombuds Support

- Health and Wellness Programs

- Profile & Web Edits

Visit Gallaudet

- Explore Our Campus

- Virtual Tour

- Maps & Directions

- Shuttle Bus Schedule

- Kellogg Conference Hotel

- Welcome Center

- National Deaf Life Museum

- Apple Guide Maps

Engage Today

- Work at Gallaudet / Clerc Center

- Social Media Channels

- University Wide Events

- Sponsorship Requests

- Data Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Gallaudet Today Magazine

- Giving at Gallaudet

- Financial Aid

- Registrar’s Office

- Residence Life & Housing

- Safety & Security

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- University Communications

- Clerc Center

Gallaudet University, chartered in 1864, is a private university for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Copyright © 2024 Gallaudet University. All rights reserved.

- Accessibility

- Cookie Consent Notice

- Privacy Policy

- File a Report

800 Florida Avenue NE, Washington, D.C. 20002

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write the Ultimate Essay Hook

4-minute read

- 6th May 2023

Never underestimate the power of an essay hook . This opening statement is meant to grab the reader’s attention and convince them to keep reading. But how do you write one that’ll pack a punch? In this article, we’ll break this down.

What Is an Essay Hook?

An essay hook is the first thing your audience will read. If it doesn’t hook them right off the bat, they might decide not to keep reading. It’s important that your opening statement is impactful while not being too wordy or presumptuous.

It’s also crucial that it clearly relates to your topic. You don’t want to mislead your readers into thinking your essay is about something it’s not. So, what kind of essay hook should you write? Here are seven ideas to choose from:

1. Story

Everyone likes a good story. If an interesting story or anecdote relates to your essay topic, the hook is a great place to include it. For example:

The key to a good story hook is keeping it short and sweet. You’re not writing a novel in addition to an essay!

2. Fact

Another great essay hook idea is to lay out a compelling fact or statistic. For example:

There are a few things to keep in mind when doing this. Make sure it’s relevant to your topic, accurate, and something your audience will care about. And, of course, be sure to cite your sources properly.

3. Metaphor or Simile

If you want to get a little more creative with your essay hook, try using a metaphor or simile . A metaphor states that something is something else in a figurative sense, while a simile states that something is like something else.

Metaphors and similes are effective because they provide a visual for your readers, making them think about a concept in a different way. However, be careful not to make them too far-fetched or overly exaggerated.

4. Question

Asking your audience a question is a great way to hook them. Not only does it make them think, but they’ll also want to keep reading because you will have sparked their curiosity. For example:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Try to avoid using questions that start with something along the lines of “Have you ever wondered…?” Instead, try to think of a question they may never have wondered about. And be sure not to answer it right away, at least not fully. Use your essay to do that!

5. Declaration

Making a bold statement or declaring a strong opinion can immediately catch people’s attention. For example:

Regardless of whether your reader agrees with you, they’ll probably want to keep reading to find out how you will back up your claim. Just make sure your declaration isn’t too controversial, or you might scare readers away!

6. Common Misconception

Laying out a common misconception is another useful way to hook your reader. For example:

If your readers don’t know that a common belief is actually a misconception, they’ll likely be interested in learning more. And if they are already aware, it’s probably a topic they’re interested in, so they’ll want to read more.

7. Description

You can put your descriptive powers into action with your essay hook. Creating interesting or compelling imagery places your reader into a scene, making the words come alive.

A description can be something beautiful and appealing or emotionally charged and provoking. Either way, descriptive writing is a powerful way to immerse your audience and keep them reading.

When writing an essay, don’t skimp on the essay hook! The opening statement has the potential to convince your audience to hear what you have to say or to let them walk away. We hope our ideas have given you some inspiration.

And once you finish writing your essay, make sure to send it to our editors. We’ll check it for grammar, spelling, word choice, references, and more. Try it out for free today with a 500-word sample !

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Writing the Introductory Paragraph

The introductory and concluding paragraphs are like the top and bottom buns of a hamburger. They contain basically the same information and are critical for holding the entire piece together.

Learning Objectives

After completing the exercises in this chapter, you will be able to

- identify the three main components of an introductory paragraph

- understand how to “hook” your reader

- identify what background information needs to be included to lead to your thesis

Essay Structure

You learned in the previous chapter that a body paragraph is structured like a hamburger. You can think of your essay as one big burger!

The top bun is the introduction.

The meat and vegetables in the middle are the supporting body paragraphs (several mini-burgers).

The bottom bun is the conclusion.

“ Burger ” by wildgica under license CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 .

The top and bottom bun are both made of bread; they contain the same ingredients (or information) but look a little bit different. The “meat” of your argument is in the supporting body paragraphs.

Structure of the Introductory Paragraph

Your introductory paragraph has three main parts:

- background information

Start your introductory paragraph with an interesting comment or question that will get your reader interested in your topic.

- a famous or interesting quotation

- an anecdote

- a startling fact or shocking statistic

- a statement of contrast

- a prediction

- a rhetorical question

- the definition of a critical concept

The hook is the very first thing your audience encounters. A good hook should be just one or two sentences. The goal of your hook is to introduce your reader to your broad topic in an interesting way and make your reader excited to read more.

Even though your hook is at the very beginning of your essay, you should actually write your hook LAST! It will be much easier for you to write an engaging introduction to your topic after you’ve done all of your research and after you’ve written your body paragraphs and conclusion.

Watch this video for tips on how to write a captivating and relevant hook [1] :

In part two of this video series, Mister Messinger gives some additional tips about writing hooks, explains some common mistakes that beginning writers make, and warns against using rhetorical questions: rhetorical questions, while fairly easy to write, are often poorly done and not engaging.

Your introductory paragraph should also include some background information. Don’t preview the ideas that you’ll introduce in your thesis – this is not the place to introduce your supporting points. Instead of giving your argument, explain the critical facts about your topic that an average reader needs to know in order to be prepared for your argument.

Examples of background information related to the broad topic that readers might need to know:

- brief historical timeline of critical events

- laws or regulations

- definitions

- current status

The information that you need to provide depends heavily on your topic:

- If you are arguing in favour of changing drinking and driving laws, your background information might explain what the current laws are.

- If you are arguing that stem cell research should be more heavily supported by the government, you should explain what the current status of stem cell research is.

- If you are arguing that culture is learned and not inherited, you might start by defining what “culture” is.

Remember that you are writing for a general audience. Don’t assume that your reader has specialized knowledge of your topic.

Remember that you are writing for a general audience, so you shouldn’t assume that your readers have any specific knowledge of your topic or that they know any specialized terminology. The background information that you provide should give your readers the information they need to understand the argument in your thesis. Be sure, though, that you don’t *preview* the thesis. Do not include your argument or any information related to your body paragraphs as background information.

Watch this video for more information about how to include relevant background information [2] :

As you know, the thesis is the most important sentence in your essay. It is placed last in the introductory paragraph. The hook and the background information should lead gracefully to the thesis. The thesis concisely states the answer to your research question by stating the specific topic, implying your stance on the topic, and listing the topics of the supporting body paragraphs.

Learning Check

Consider this short introductory paragraph and answer the questions that follow:

Sample Introductory Paragraph

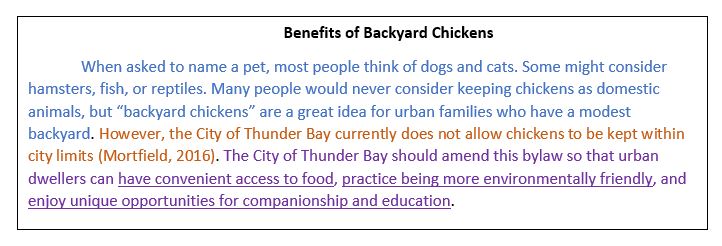

Let’s look at this introductory paragraph that was created by a student for her essay on why the City of Thunder Bay should change its existing laws to allow residents to raise chickens.

The writer’s hook is in blue text. The writer is trying to engage the reader on the topic by providing a surprising contrast. What other hooks could the writer have used instead?

The background information is in orange text. The writer realized that her readers wouldn’t be able to understand her point of view if they didn’t know that the law currently forbids city residents from raising chickens on their property. Is this enough background information for you to understand the thesis? What additional information could the writer have provided?

The thesis is in purple text. The thesis statement is well-written and clearly states all necessary information:

- The specific topic (the ‘chicken bylaw’ in Thunder Bay)

- The writer’s stance (the bylaw should be changed to allow raising chickens within city limits)

- The reasons for the writer’s stance (the underlined clauses in the thesis)

When the writer drafts her body paragraphs, she needs to make sure that each underlined idea is the topic of a paragraph and that those paragraphs are organized in the same order as the ideas are presented in the thesis.

- Mister Messinger. (2020, July 7). Part 1: Discover how to start essay with an A+ hook: STRONG attention grabbing examples [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yvrnVHd-oyM ↵

- Mister Messinger. (2020, August 6). How to start an essay: Add background information to write a strong introduction [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bd1t2u-HbE&t=223s ↵

According to Wikipedia: A paraphrase is a restatement of the meaning of a text or passage using other words.

According to Wikipedia: Mosaic Plagiarism – Or "patch writing," is when parts of other works are copied without using quotation marks. It can also be when a student keeps the same structure and meaning of an original passage and only uses synonyms

Writing the Introductory Paragraph Copyright © by Confederation College Communications Department and Paterson Library Commons. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

How to Write a Hook: Start Off Your Essay Strong with This Guide

What is a Hook for an Essay: Importance and Purpose

Which section of your essay can make your readers dip their toes into your writing? Is it the body paragraphs where all the analysis is laid out? Or maybe the introduction, where you present your thesis statement and voice your perspective on the subject? Well, if you think it is the latter, then we must agree with your decision. However, let's get more specific; if we take the introductory paragraph to pieces, which piece gets the most recognition? You must have guessed from the article's title that we're talking about a hook. But first, let's define what is a hook for an essay before we walk you through the reasons why it deserves our pat on the back.

The hook is the initial sentence in a written work. Whether you're asking how to write a hook for a song, blog post, or term paper, know that the purpose of any effective hook is to seize the reader's attention. It can be one sentence long, often for shorter pieces, or composed of several lines - usually for larger pieces. Making the reader want to keep reading is what an essay hook accomplishes for your paper, just as an intriguing introduction does for any piece.

Our main emphasis in this guide is on creating a good hook for an essay. Nonetheless, these fundamental guidelines apply to nearly every format for communicating with your audience. Whether writing a personal statement, a speech, or a presentation, making a solid first impression is crucial to spur your readers into action.

How to Write a Hook for Different Kinds of Writing

Although it is a tough skill to master, understanding how to write a hook is crucial for academic writing success. By reviewing the most prevalent kinds of essay hooks, you can discover how to effectively captivate readers from the start and generate a hook that is ideal for your article. To do so, let's head over to the following sections prepared by our dissertation writers .

%20(1).webp)

How to Write a Hook for a College Essay?

By mastering how to write a hook for a college essay, you have the opportunity to stand out from the hundreds of applicants with identical academic portfolios to yours in your college essay. It should shed light on who you are, represent your true nature, and show your individuality. But first, you need an attention-grabbing start if you want the admissions committee to read more of yours than theirs. For this, you'll require a strong hook.

Set the Scene

When wondering how to write a good hook for an essay, consider setting the scene. Open in the middle of a key moment, plunge in with vivid details and conversation to keep your essay flowing and attract the reader. Make the reader feel like they are seeing a moment from your life and have just tuned in.

Open with an Example

Starting with a specific example is also a great idea if you're explaining how you acquired a particular skill or unique accomplishment. Then, similar to how you established the scenario above, you may return to this point later and discuss its significance throughout the remaining sections.

Open with an Anecdote

Using an anecdotal hook doesn't necessarily mean that your essay should also be humorous. The joke should be short and well-aimed to achieve the best results. To assist the reader in visualizing the situation and understanding what you are up against when tackling a task or overcoming a challenge, you might also use a funny irony. And if this sounds too overwhelming to compose, buy an essay on our platform and let our expert writers convey your unmatched story!

How to Write a Hook for an Argumentative Essay?

If you write a strong hook, your instructor will be compelled to read your argument in the following paragraphs. So, put your creative thinking cap on while crafting the hook, and write in a way that entices readers to continue reading the essay.

Use Statistics

Statistics serve as a useful hook because they encourage research. When used in argumentative writing, statistics can introduce readers to previously undiscovered details and data. That can greatly increase their desire to read your article from start to finish. You can also consider this advice when unsure how to write a good hook for a research paper. Especially if you're conducting a quantitative study, a statistic hook can be a solid start.

Use a Common Misconception

Another answer to your 'how to write a hook for an argumentative essay' question is to use a common misconception. What could be a better way to construct an interesting hook, which should grab readers' attention, than to incorporate a widely held misconception? A widespread false belief is one that many people hold to be true. When you create a hook with a misinterpretation, you startle your readers and immediately capture their interest.

How to Write a Hook for a Persuasive Essay?

The finest hooks for a persuasive essay capture the reader's interest while leading them to almost unconsciously support your position even before they are aware of it. You can accomplish this by employing the following hook ideas for an essay:

Ask a Rhetorical Question

By posing a query at the outset of your essay, you may engage the reader's critical thinking and whet their appetite for the solution you won't provide until later. Try to formulate a question wide enough for them to not immediately know the answer and detailed enough to avoid becoming a generic hook.

Use an Emotional Appeal

This is a fantastic approach to arouse sympathy and draw the reader into your cause. By appealing to the reader's emotions, you may establish a bond that encourages them to read more and get invested in the subject you cover.

Using these strategies, you won't have to wonder how to write a hook for a persuasive essay anymore!

How to Write a Hook for a Literary Analysis Essay?

Finding strong essay openers might be particularly challenging when writing a literary analysis. Coming up with something very remarkable on your own while writing about someone else's work is no easy feat. But we have some expert solutions below:

Use Literary Quotes

Using a literary quote sounds like the best option when unsure how to write a hook for a literary analysis essay. Nonetheless, its use is not restricted to that and is mostly determined by the style and meaning of the quotes. Still, when employing literary quotes, it's crucial to show two things at once: first, how well you understand the textual information. And second, you know how to capture the reader's interest right away.

Employ Quotes from Famous People

This is another style of hook that is frequently employed in literary analysis. But if you wonder how to write a good essay hook without sounding boring, choose a historical person with notable accomplishments and keep your readers intrigued and inspired to read more.

How to Write a Hook for an Informative Essay?

In an informative essay, your ultimate goal is to not only educate your audience but also engage and keep them interested from the very beginning. For this, consider the following:

Start with a Fact or Definition

You might begin your essay with an interesting fact or by giving a definition related to your subject. The same standard applies here for most types mentioned above: it must be intriguing, surprising, and/or alarming.

Ask Questions that Relate to Your Topic

Another solution to 'How to write a hook for an informative essay?' is to introduce your essay with a relevant question. This hook lets you pique a reader's interest in your essay and urge them to keep reading as they ponder the answer.

Need a Perfect Article?

Hire a professional to write a top-notch essay or paper for you! Click the button below to get custom essay help.

Expert-Approved Tips for Writing an Essay Hook

Are you still struggling with the ideal opening sentence for your essay? Check out some advice from our essay helper on how to write a hook sentence and make your opening stand out.

.webp)

- Keep your essay type in mind . Remember to keep your hook relevant. An effective hook for an argumentative or descriptive essay format will differ greatly. Therefore, the relevancy of the hook might be even more important than the content it conveys.

- Decide on the purpose of your hook . When unsure how to write a hook for an essay, try asking the following questions: What result are you hoping to get from it? Would you like your readers to be curious? Or, even better, surprised? Perhaps even somewhat caught off guard? Determine the effect you wish to accomplish before selecting a hook.

- Choose a hook at the end of the writing process. Even though it should be the first sentence of your paper, it doesn't mean you should write your hook first. Writing an essay is a long and creative process. So, if you can't think of an effective hook at the beginning, just keep writing according to your plan, and it will eventually come into your head. If you were lucky enough to concoct your hook immediately, double-check your writing to see if it still fits into the whole text and its style once you've finished writing.

- Make it short . The shorter, the better – this rule works for essay hooks. Keeping your hook to a minimum size will ensure that readers will read it at the same moment they start looking at your essay. Even before thinking if they want or don't want to read it, their attention will be captured, and their curiosity will get the best of them. So, they will continue reading the entire text to discover as much as possible.

Now you know how to write a good hook and understand that a solid hook is the difference between someone delving further into your work or abandoning it immediately. With our hook examples for an essay, you can do more than just write a great paper. We do not doubt that you can even write a winning term paper example right away!

Try to become an even better writer with the help of our paper writing service . Give them the freedom to write superior hooks and full essays for you so you may learn from them!

Do You Lack Creative Writing Skills?

This shouldn't stop you from producing a great essay! Order your essay today and watch your writing come alive.

What Is A Good Hook For An Essay?

How to write a hook for an essay, what is a good hook for an argumentative essay.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

- Testimonials

In an essay, which comes first: the hook or the thesis?

An eighth grader asked me for help writing a school-assigned essay. Her teacher had given the class a fill-in-the-blanks organizer. It was incredibly detailed. In the introduction area was a blank with the word “hook,” and below it another blank with the word “thesis.” For each of the two body paragraph areas were the words “citation, “explanation,” “citation,” and “explanation.” At the end was the word “conclusion.”

“I don’t buy it,” I said.

I asked her what she had written first, the hook quotation or the thesis. “The hook,” she said.

Of course. This student was making three mistakes that I see over and over in student essays.

First, she did not write the thesis first. In an essay, the most important sentence is the thesis. That is the first sentence to write. Every other sentence needs to support the ideas in that thesis sentence. If you don’t know what ideas are in the thesis, how can you write about them?

Second, she wrote the hook first, thinking (as her teachers may have told her) that the hook is where the essay begins. The hook is where the reader begins reading an essay. But it is not where the writer begins writing an essay. A good essay is thought though and written out of order. The proper sequence in which to write an essay (after you have organized it) is

- Thesis, first;

- body paragraph topic sentences, second;

- detail sentences in the body paragraphs, third. These sentences back up the body paragraph topic sentences which in turn back up the thesis;

- introduction, fourth, including the hook if there is one; and

- conclusion, last.

The third mistake my student made was perhaps the most serious of all: she didn’t recognize that her chosen hook did not introduce the ideas of her thesis. She thought that her hook was so clever (and it was) that it didn’t matter if it was related to the ideas of her thesis. It does matter.

Over and over, I work with students who focus on the structure of an essay rather than the substance of the essay. Their essays are like Academy Award winning actresses in gorgeous gowns, sparkling jewelry, and splendid coifs whose speeches are either hollow or off-topic.

I asked my student to rewrite her hook. She did because she wants a good grade, and I’m a teacher, so I probably know what I am advising her. But I wonder if she understands that her original hook was irrelevant to the main idea of her essay.

Looking for a writing teacher for your child? Contact me through this website. I currently teach students in four states and one other country.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

What's your thinking on this topic? Cancel reply

One-on-one online writing improvement for students of all ages.

As a professional writer and former certified middle and high school educator, I now teach writing skills online. I coach students of all ages on the practices of writing. Click on my photo for more details.

You may think revising means finding grammar and spelling mistakes when it really means rewriting—moving ideas around, adding more details, using specific verbs, varying your sentence structures and adding figurative language. Learn how to improve your writing with these rewriting ideas and more. Click on the photo For more details.

Comical stories, repetitive phrasing, and expressive illustrations engage early readers and build reading confidence. Each story includes easy to pronounce two-, three-, and four-letter words which follow the rules of phonics. The result is a fun reading experience leading to comprehension, recall, and stimulating discussion. Each story is true children’s literature with a beginning, a middle and an end. Each book also contains a "fun and games" activity section to further develop the beginning reader's learning experience.

Mrs. K’s Store of home schooling/teaching resources

Furia--Quick Study Guide is a nine-page text with detailed information on the setting; 17 characters; 10 themes; 8 places, teams, and motifs; and 15 direct quotes from the text. Teachers who have read the novel can months later come up to speed in five minutes by reading the study guide.

Post Categories

Follow blog via email.

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Peachtree Corners, GA

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Get in Touch with CCC’s Learning Commons

Writing an introduction and thesis.

Starting the first paragraph can be one of the most daunting tasks of essay writing, but it does not need to be. Investing some time in planning can save much anxiety and frustration later.

An effective introductory paragraph will engage the reader with some reason to learn about your topic and will warm him or her up to your topic with important background information and ideas before stating your essay’s controlling idea (thesis.) It should include the following:

- Hook (also called a Lead-in, Opener, or Attention Grabber) that will arouse the interest of as many people possible in your target audience group.

- Identification and general discussion of the topic , including why the topic is important and worthy of analysis.

- Background info (e.g. history of the controversy, or summary of the literature/ articles.) This is any information necessary to lead down to your controlling idea on the subject, including the who , what , when , where , why , and how.

- Explanation that narrows your focus down to your thesis.

- Thesis (your controlling idea for the whole essay), possibly including , preceded by or followed by a brief indication of your subtopics. (This latter part is sometimes called a blueprint, roadmap of reasons, forecast of points, etc.).

It is essential that the first sentence “hooks” your intended reader with something that is both interesting at first glance and relevant to the focus of your essay. Try one or a combination of the following hooks:

- Example: The number of emergency room visits associated with energy drinks has more than doubled in this country in the last five years, from about 10,000 to over 20,000.

- Example: There I was, stranded with no cell phone beside a remote Colorado road in mid-January. I had long since lost feeling in my feet, and, peeling back my socks, I saw to my horror that my toes were completely black with frostbite.

- Example: For a first-time parent, a child is a megaphone, proclaiming that he or she is not the center of the universe anymore.

- Example: An important purpose of fiction is to reveal truth.

- Example: Has anyone you know ever been the victim of identity theft?

- Example: Victor Hugo, the author of Les Miserables , once declared, “ He who opens a school door closes a prison.”

Options for that Middle Material

You might have a great idea for your hook and even a tentative thesis, but what about the sentences that are supposed to go between them? How are you going to meaningfully and smoothly bridge this gap? It might depend on what kind of essay you are writing. Here are some suggestions, though don’t feel locked into that one option just because it is labeled for your type of essay. Also , be aware that some of these options might naturally contain their own hooks.

- For a Position/Argument/Persuasive Essay : Be sure to establish that a real controversy exists before giving your position in the thesis. What is the issue? Why do people disagree about it? Are there more than just two sides? How long has this controversy existed? What are the ‘roots’ or brief history of the conflict? Lead down to your position (thesis), and then your body paragraphs will be the reasons for your position.

- For a Solution Essay : Highlight the problem or need. Get the reader to understand that one exists. What is it? Why is it a problem or need? How long has it been around? Who and/or what is affected? Then work down to the thesis, which in this case is your proposed solution. The body paragraphs will then be breaking down your solution into its reasons and/or steps.

- For a Compare/Contrast Essay : If the main point of your essay is to show how two things are significantly similar, consider first explaining that people often perceive them as completely different and unrelatable—why is that? If the main point of your essay is to show how two things are significantly different, consider first explaining that people often perceive them as essentially the same—explain why and then lead down to your thesis.

- For a Current Events or History Essay : Consider beginning at a different point in time than the one focused on in the body of your paper. For example, if your paper is to focus on a specific current event/situation between Israelis and Palestinians, you might lead in with a brief overview of the groups’ long-term history. Alternately, if the focus of the paper is on a historical event or period, you might begin with discussion about the present-day region or nation, or you could begin at a point even further in the past that led up to the period of focus.

- For an Illustrative/Descriptive Essay : If your task is to describe a person, place, thing, process, or concept, then you must begin by motivating the reader as to his/her/its appeal or importance (as with any introduction.) For more personal, informal essays, you can relate your own earliest experiences with that person, place, or thing, possibly explaining your first impressions. For more formal essays, highlight his/her/its significance to a larger group of people or to a larger purpose/function.

- For a Research/Expository Essay : Explain who is/has been affected, and how much or often. Also be sure to define any major terms that you will be using throughout the paper if they are not necessarily understood by your intended audience.

- For a Cause/Effect Essay : If your essay will be focusing on the causes of a particular event, condition, or situation, explain who or what is affected by it. How prevalent is it? If the focus of the essay is on the effects of something, you might provide background by discussing what leads/has led up to it (its causes).

- For an Analytical Essay (e.g. literature, philosophy, article response): Before diving into interpretation and analysis, use your introduction to announce the original work and author/theorist, giving background about either or both. Consider a brief summary of the story, concept, or major ideas of the piece, then narrow down to the specific ideas you will be working with in the essay.

A Quick Thesis Formula

Tips for your thesis.

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible, yet still able to be developed in different ways through your body paragraphs. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions: “Communism collapsed due to societal discontent.” Communism where? What does “societal discontent” mean? Society can be discontent about anything! Here is an improvement: “Co mmunism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite’s inability to address the economic needs of the people .”

The Topic is relatively specific: communism in Eastern Europe. Also, the Main Point (italicized segment) is clear. Now in this example, the Details (how the body paragraphs will be broken down) are only hinted at, but that might be enough for some courses as long as you have strong, guiding topic sentences that connect back to these key words from the thesis.

In some courses though, especially ENGL 1010, you might need to absolutely spell out the breakdown of subtopics in your thesis (a forecasting thesis). So here is an example of one, and to make it even more ENGL 1010-friendly, it is an argumentative thesis. The Topic , Main Point , and Details are indicated: “The public sale of fireworks in Pennsylvania should be prohibited because of fireworks’ danger to people , noise disturbance , and potential damage to property .”

Thesis Pitfalls

Check to make sure your thesis is not…

- Too broad or general: “Drugs have a negative effect on society.”

- Too big to be adequately covered within the assigned length of a paper: “Warfare in Europe has greatly evolved through the centuries with many different forms.”

- Too narrow a focus to sustain an essay of the required length: “All students should have an alarm clock to wake them up in the morning.”

- A question: “What will the United States do to curb gun violence?”

- An obvious idea: “Spending more money than you earn results in debt.”

- Combative, insulting, assuming, or confrontational: “Gun nuts need to understand that they don’t need to have so many guns because violence is evil.”

- A basic definition of a word: “Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on sex or gender .”

- Lacking any strong stand: “Legislation surrounding same-sex marriage is a hotly debated issue today.”

- Stating a fact, offering little room for expansion: “Sixty-seven percent o f pregnant women have claimed to have a higher level of smell sensitivity.”

- Containing more than one main idea: “Asbestos abatement is a complicated process, and it is also important to check one’s home for radon.” (A thesis can have more than one idea, but the hierarchy should be clear. That is, one should be easily identifiable as the main idea, while the others are clearly supporting it).”

Other Introduction Paragraph PItfalls

- Writing a very attention-grabbing hook, but failing to connect its meaning with the rest of the paragraph.

- Going too deep into your reasons or subtopics within your introduction, and so setting yourself up to be repetitive later in the essay.

- Opening with a cliché statement or a very obvious idea.

- Referring to your essay or referring to yourself as the writer of the essay (“In this essay I will tell you about…”)

- Relying immediately on a reference source to define your subject for you. (“According to Webster’s Dictionary…” or “Wikipedia states…”)

A Final Word

Remember, your introductory paragraph sets the tone for your essay and is your first impression, so it is worth taking your time on. But don’t worry if it does not come off sounding exactly right the first time. We are all learners as writers! It is natural and necessary to return to your introduction for revision after you have drafted the rest of your essay, just to make sure it is still consistent with what the paper has evolved into.

We at the Learning Commons are here to help at any stage of the writing process. Please come in anytime to go over what you have so far , even if you haven’t written anything down yet . We can help you find your direction. Also check out our handout s “Building Body Paragraphs” and “ Writing a Conclusion , ” among many others . We hope you take joy in your writing as you investigate a subject that interests you and that you also have the chance to express yourself well.

- Adaptations for format / ADA compliance. Authored by : Dann Coble. Provided by : Corning Community College. License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Authored by : Keith Ward. Provided by : Corning Community College. License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Privacy Policy

The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

How to Write a Hook

How can you hook your reader from the very first line? Today we learn how to write a hook, talk about different types of hooks, and examples!

How do you write a hook? If you can’t answer this deceptively simple question, you might as well stop writing forever. Without a decent hook, the chance of anyone reading your work is statistically zero. With that said, let’s define hooks, discuss how to write a compelling hook, and look at some examples.

What is a hook in writing?

A hook is a technique used in fiction and non-fiction writing. The term hook refers to the opening sentence or sentences of a work designed to stir interest in a reader and encourage them to continue reading to the end of the article or story. In other words, the hook catches a reader’s attention much like a hook on the end of a fishing line catches a fish with bait.

Let’s continue this analogy of the fishing hook. You need to bait your hook with a tasty worm or a flashy lure to catch a fish. Writers bait their hooks using techniques as tempting to a reader’s interest as a fat worm is to bass or catfish. These hook techniques include posing an intriguing question or stating a frightening statistic. We’ll talk about all of these techniques later in the article.

Definition of a Hook:

A hook in writing is a sentence or group of sentences that capture the reader’s attention and interest. It is generally the opening component of an essay, article, or story. It is meant to entice readers so that they will want to keep reading.

The 10 types of hooks

Rhetorical Questions

A rhetorical question is a question that is asked to make a point rather than to get an answer. Rhetorical questions are often used in speeches and essays, where they are used to engage the audience or emphasize a point. For this reason, rhetorical questions can make an excellent hook. With a rhetorical question hook, a writer can:

- elicit a particular response from the reader or listener

- create an emotional reaction

- emphasize a point

- make an argument more persuasive

- engage the reader or listener’s attention

- generate interest in a topic

For example, a speaker might ask, “How many of you have ever felt like you didn’t belong?” This is a rhetorical question. The speaker already knows the answer and is not looking for a response from the audience.

Instead, the question is meant to make the audience stop and think about their own experience. In addition to being used for emphasis, rhetorical questions can create suspense or build tension. For instance, a writer might use a rhetorical question at the end of a chapter to leave readers wondering what will happen next. Whether they create emphasis or suspense, rhetorical questions can be a powerful tool for writers and speakers.

Startling Statistics

By sharing shocking or unexpected data, you can grab your audience’s attention and make them more likely to listen to what you have to say. Whether you’re talking about the scope of a problem or the success of a solution, statistics can help you generate interest and hold your audience’s attention. Here are a few examples of starling statistics from the website bestlifeonline.com:

- The average drunk driver drives under the influence more than 80 times before being arrested the first time. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention .

- More than 36 million U.S. adults cannot read above a third-grade level. Source: ProLiteracy.

- And more than half a million people in America experience homelessness a night. Source: U.S Department Of Housing and Urban Development .

Just be sure that the statistics you use are reliable and from a reputable source. Otherwise, you risk losing credibility with your audience. Using false or unreliable statistics can cause your readers to become skeptical or even hostile.

For example, a recent Gallup poll found that only 36% of Americans trust the media . Using statistics from the media in a speech can alienate much of the audience. It’s essential to be careful when using statistics in writing, as they can easily make or break an argument.

Used effectively, however, statistics can be a powerful tool for making your case and getting people to pay attention.

Famous or Inspiring Quotes

The most challenging task for any writer is capturing a concept or idea with the perfect combination of words. Luckily, better writers have come before us; we can borrow their words when we find our own lacking. These quotes can provide both inspiration and comfort, and they can also help us to understand our own thoughts and feelings better. Using quotations in your hook can be an excellent way to connect with your audience and add depth to your work.

Here are a few resources where you can find the perfect quote for your next essay or speech:

- BrainyQuote: separates quotes into several functional categories.

- QuotesonDesign: generates random inspirational quotes with the click of your mouse.

- Thinkexist: a searchable database of quotes based on topic, author, or keyword.

- Goodreads: Goodreads is one of the best resources for quotes from famous authors.

- QuoteLand: another searchable database with the added benefit of live discussion boards.

- Wikiquote: a free online compendium of sourced quotes that links to Wikipedia for further information.

- Quotery: search for specific quotes or explore random quotes by topic.

Paint a Picture

Engage your readers’ imagination with this hook by painting a picture in their minds. This technique works well when you’re writing a personal narrative or other non-fiction narratives. Take the highest moment of tension in your story, the climax, and describe it by appealing to all five senses.

However, what you don’t want to do is explicitly tell your reader what’s happening or the outcome of the event. Instead, you use foreshadowing and a bit of non-linear storytelling to give your reader an enticing hint at what is coming in your text.

To use this hook technique, take the highest point of tension in your text and describe it using as much sensory detail as possible.

What does the climax of your story:

- Smell like?

- Taste like?

- Sound like?

You may not want to use all five senses; in fact, it is better not to give your reader enough detail and let their imagination do the rest.

Tell a Story

A good story can hook readers in and keep them engaged from start to finish. A story can provide insight into the human experience, whether it be humorous, heartwarming, or even tragic. When used as a hook in writing, a story can help set the tone and give readers a glimpse into what is to come.

Done poorly, however, a story can be dry and dull, quickly losing the interest of even the most dedicated reader. As such, it is crucial to strike the right balance when writing a story as a hook. Whether personal or fictional, choose a story that is interesting and engaging and will give readers a reason to stick around until the end.

Extreme Statements

Extreme statements are one type of hook that can be used effectively to engage readers. By making a bold claim or assertion, writers can pique readers’ curiosity and prompt them to want to know more. For example, imagine reading the following opening sentence:

“By 2050, the world’s population will reach 9 billion, and we will not have enough food to feed half of this number.”

This statement is shocking and provocative. It immediately raises questions in readers’ minds, like “How did the author come up with this number?” and “What consequences will this have for the planet?” By starting with an extreme statement, writers can set the stage for an informative and engaging piece.

Tell a Joke

Although the folly of many a Best Man, a good joke can be a great way to start a piece of writing. Not only does it grab the reader’s attention, but it also sets the tone for the rest of the article. When used effectively, a joke can help to establish a rapport with the reader and create a sense of intimacy. A joke, done poorly, can come across as forced or tacky.

The key is to choose a joke that is relevant to the topic at hand, and that will resonate with the audience. When in doubt, it is always best to err on the side of caution and avoid alienating your reader with an off-color joke. With a little effort, you can use humor to your advantage and hook your reader from the very first sentence.

Evoke a Feeling/Emotion

One way to hook a reader is to evoke an emotion in your readers. Whether you are writing about a personal experience or trying to raise awareness about an important issue, if you can connect with your readers emotionally, you will be more likely to engage them in your writing.

To do this, you must be clear about what emotion you want to evoke and how you plan to do it. Once you have a plan, try to be concise and transparent in your writing. Remember, the goal is not to overwhelm your readers with emotions but to give them a taste of what you are talking about so that they will want to continue reading.

Personal Stories

A personal story can be a powerful way to hook readers and keep them engaged. By sharing something from your own life, you can provide a relatable and authentic perspective that helps to connect with your audience.

Whether you’re writing about your struggles or triumphs, sharing a personal story can help to create a strong emotional response in your readers. In addition, personal stories can also be used to illustrate more significant points or themes.

By sharing a specific example, you can make abstract concepts more concrete and accessible for your readers. Whether you’re writing an essay, memoir, or blog post, incorporating a personal story can effectively engage your audience and communicate your message.

Use a Metaphor or Analogy

When writing, a metaphor can help explain an idea or concept. Using an analogy, you can give your reader a frame of reference that they can understand. For example, if you were trying to explain what it feels like to be in love, you could say it is like this:

“A rose’s beauty draws you in, but be careful its thorns can prick.”

Using this metaphor, you can give your reader a way to understand the experience of being in love: beautiful and painful.

Analogies can also be used to make complex ideas more understandable. For instance, if you were trying to explain quantum mechanics, you could say it is:

“Like trying to see in the dark: we know something is there, but we can’t see it.”

By providing this analogy, you can give your reader a way to visualize what quantum mechanics is and how it works. In both cases, using a metaphor or analogy can help make your writing more engaging and understandable.

How to write a hook sentence in six steps

Step 1: Choose the correct technique for your hook.

First, you need to decide what kind of hook you will write. This choice has everything to do with the tone and genre of your writing. For instance, you probably want to avoid using a joke hook in a scholarly paper. On the flip side, a startling statistic wouldn’t make sense to open a wedding speech.

Step 2: Make sure it’s in the right place.

A hook is meant to grab your readers’ attention and compel them to read the rest of your text. So, the hook should be at the beginning of your writing, with nothing else preceding it.

Ok, the title will come before your hook. However, with the rise of clickbait, titles have become hooks in their own right. Start with your hook, no exceptions!

Step 3: Write a hook that is the correct length.

Hooks are proportional to the length of text you’re writing. So, a twenty-paragraph article for a magazine or newspaper may have a hook one or two paragraphs long. However, if you’re writing a four or five-paragraph essay for your high school theme paper, your hook will only last a sentence, maybe two.

What you don’t want is a two-paragraph long hook in five paragraph essay. The best hook is a short one that is to the point.

Step 4: Set the tone .

A good hook can also help set the tone for your writing. If you’re writing something lighthearted and funny, your hook should reflect that. On the other hand, if you’re writing something more serious, ensure your hook is also appropriately toned.

Step 5: Know your audience .

It’s important to know who you’re writing for when crafting your hook. What will resonate with your audience? What will grab their attention? Keep your audience in mind as you write so you can tailor your hook accordingly.

Step 6: Transition into the purpose of your writing.

What comes after you hook? Your thesis! Once you’ve hooked your reader, it’s essential to tell them, in a short thesis statement, what the purpose of your text is. Refrain from making sure readers guess what the main idea of your essay is. Tell them what you’re going to tell them. A good thesis statement will focus your writing and keep your readers engaged.

Hook examples:

Dr. Martin Luther King- I Have a Dream

Five score years ago, a great American , in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation . This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

In the opening lines of his famed speech, King alludes to another famous speech- Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. By referencing a speech made in the aftermath of the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War, King reminds his audience of the sacrifices made in the long struggle for equality and civil rights.

Sojourner Truth- Ain’t I A Woman?

Well children … Well there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that betwixt the Negroes of the South and the women at the North all talking about rights these white men going to be in a fix pretty soon.

Sojourner Truth famously improvised her speech, Ain’t I A Woman. She opens with a bit of humor and sets the tone for her straightforward yet powerful words.

Carl Sagen- Pale Blue Dot

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.

Sagen reminds his readers of the startlingly insignificant reality of our world when contrasted to the vast universe.

Amanda Gorman- The Hill We Climb

When day comes we ask ourselves, where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

With the opening lines of her poem, Gorman creates a beautiful metaphor comparing a transition during political and social upheaval to the dawn of a new day.

Jamie Oliver- Teach Every Child About Food

Sadly, in the next 18 minutes… four Americans that are alive will be dead from the food that they eat.

This fact is shocking and focuses the audience’s attention on Oliver’s subject- the obesity epidemic in America.

The bottom line on hooks- make it short, memorable, and if you can’t think of anything… use a quote. That’s all on hooks for now, but if you liked this article, and found it helpful, do us a favor and share it!

Published by John

View all posts by John

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copy and paste this code to display the image on your site

Discover more from The Art of Narrative

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

Supported by

The Ezra Klein Show

Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews James Pethokoukis

Every Tuesday and Friday, Ezra Klein invites you into a conversation about something that matters, like today’s episode with James Pethokoukis. Listen wherever you get your podcasts .

Transcripts of our episodes are made available as soon as possible. They are not fully edited for grammar or spelling.

A Conservative Futurist and a Supply-Side Liberal Walk Into a Podcast …

Could the u. s. economy be twice as large today if it hadn’t made policy mistakes in the 1970s.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

From New York Times Opinion, this is “The Ezra Klein Show.”

I don’t know if y’all were fans growing up of the show “The Jetsons,” but if you were and if you were super fan enough to take the internal math of the show seriously, George Jetson was supposed to have been born in 2022. He would be a toddler right now. And the world we live in, the world my toddlers are growing up in, it does not feel like it is a world on path to the future the Jetsons imagined, a future that a lot of people in the 1960s thought was totally plausible by the 2020s, 2030s, 2040s, 2050s.

So what happened that got us off of that track? Not just the real track, but the imaginary track? Another way of asking this question, a question that’s come up a lot in the book I’m writing about how liberalism changed and why it’s become so difficult to build is, what happened in the 1970s?

The ‘70s are this breakpoint between one era in our economy and our government and our society and our vision for the future and the next. The ‘70s are when economic inequality really begins rising, when the environmental movement takes off, when a huge amount of legislation is passed in response to the harms of all the building and growth that had happened since the New Deal.

But there’s this tendency to look at the places that legislation goes too far and to say, well, if we hadn’t made all these dumb mistakes, everything would be great. We’d be richer. We’d have our moon colonies and our flying cars and our nuclear energy. We would have made it to Jetsons land.

But then why did no other country take that path? To just wipe away the politics and the passions that led to the backlash against certain forms of growth and technology in a lot of different countries is to miss something important, something that anybody who cares about growth is going to need to understand, if we’re not just going to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Jim Pethokoukis is a senior fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. He’s the author of the technology-focused Substack, Faster, Please! and of the recent book, “The Conservative Futurist.” And one thing I’ve noticed is there are ways in which I feel like he and I are asking a lot of the same questions, but from very different ideological positions. So I wanted to see where our stories converge and where they differ and what happened to the world of the Jetsons. As always, my email, [email protected].

Jim Pethokoukis, welcome to the show.

Thanks so much for having me on.

So I wanna begin this conversation in the early ‘70s. Things change in the U.S. economy on any number of charts. You begin to see something happen to the line. What are some of those changes?

The most obvious change, at least especially from an economics point of view, is that the sort of rapid productivity growth that we saw in the previous couple of decades that economists and other experts in the ‘60s thought was going to be a permanent state of affairs slowed down. And other than, really, the late ‘90s or early 2000s, it’s been in that sort of weaker state. And it’s one of the great, still, conundrums for economists.

I mean, economists still, less so now, would have debates about what caused the Great Depression. And to me, this downshift, what I call in my book, “the great downshift in productivity growth,” is as significant as that because of we’re not where we could be if it hadn’t.

So if it had kept growing since the ‘70s, as it did in the couple decades before, what would the US economy look like? What would the median household income look like?

Bigger, more, multiples more, and that was the expectation. So instead of having a $25 trillion economy, depending on how you want to slice the numbers, it could be twice as big, it could be three times as big. So I don’t know. I mean, I think conservatively, instead of the median family making $80,000 adjusted for inflation, maybe they make $150,000. I mean, it’s pretty significant.

What that economy would look like? Well, listen, to grow that fast, it would be driven by technological progress. And that’s what people expected in those immediate postwar decades. So all the sort of the kind of classic, retro, Jetsons kind of sci-fi things that people imagined back then, it wasn’t just sort of cartoons and films. Experts, technologists, CEOs, economists all expected that kind of stuff to actually happen.

So nuclear power and everything, nuclear reactors from coast to coast. We would probably have, colonies on the moon and Mars. Cures to diseases, which seem like chronic diseases, which we still battle, would be cured.

All of that together would be part of this grand future, driven by rapid, technological progress, which drives faster productivity growth, which drives faster economic growth. If there’s one lesson of the pandemic, is, people don’t like suffering and shortages, so we better figure out a different way. I see the only path forward is through growth and technology and making that work.

What is your theory, though, of what happened in the ‘70s? What do you see as the contributors to this slowdown?

I think, certainly, it was probably multi-causal. One reason I wrote the book, to be honest, is a paper, a paper by an economist named Ray Fair from Yale University who noticed something weird happened around the ‘70s. He wasn’t focused on productivity growth, but he looked at infrastructure spending as a share of total economic spending. And he looked at what was going on with the budget, where we started to begin to run smaller surpluses and run budget deficits around 1970.

And he asked the exact same question that you’re asking. So, like, what happened? Because from those two statistics, he began to wonder like, that, to me, seems like a society that’s less future oriented than it used to be. You tended to see it more in the United States than in other places.

So what are your theories?