U.S. Government Accountability Office

Back to School for K-12 students: Issues Ahead

As students and teachers head back to the classroom this fall, they are likely to face a number of challenges that could impact the 2022-23 school year and learning outcomes.

We’ve reported on these mounting challenges during the last couple years. Today’s WatchBlog post looks at our work on the issues students, educators, and schools are facing including pandemic learning loss, absenteeism, achievement at virtual charter schools, school redistricting, and bullying.

Learning loss and absent students

Some students may be returning to school behind on their education.

For a series of 2022 reports, we surveyed teachers about students’ potential learning loss during the pandemic. They told us that many students struggled to learn during the pandemic because of its disruption.

We found that, in the 2020-21 school year, across all grades and regardless of in-person, remote, or hybrid learning models, nearly two-thirds of teachers (64%) had more students who made less academic progress than in a typical school year. And 45% of teachers reported that at least half of their students ended the year a grade level behind.

While this learning loss was widespread, some students were disproportionately impacted, including students from high poverty households, students learning English, and our youngest K-12 students. As a result, long term, the pandemic may have contributed to growing disparities between student populations.

In addition, some students may not return to school this year at all. We recently found that, during the 2020-21 school year, more than a million teachers reported having students who never showed up for class despite being registered for school.

Students who did not show up came mostly from majority non-White and urban schools and faced obstacles to learning, such as no adult assistance at home. We also found that older students may have missed school because they were caring for family members or working themselves.

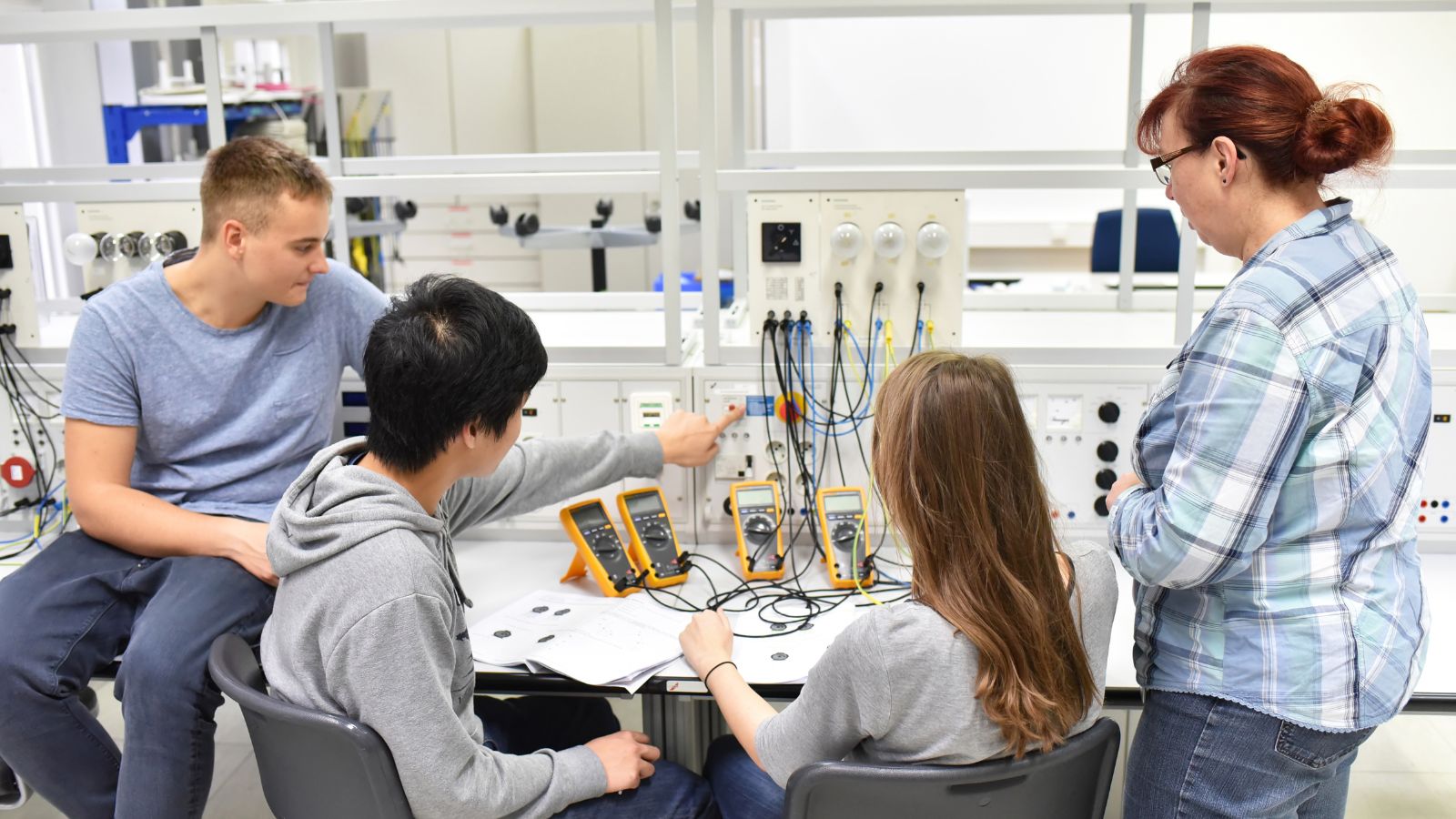

Lower student achievement in virtual charter schools

While many families were first introduced to virtual schooling during the pandemic, virtual and hybrid programs are not new. We recently explored challenges for students in virtual charter schools—the largest sector of virtual schools and the fastest growing type of public school in the U.S. For example, students attending virtual charter schools generally showed significantly lower rates of academic proficiency compared to the rest of their public school peers.

Virtual charter schools also reported lower student participation on federally-required state testing—a key measure of academic achievement. Our podcast with K-12 education expert Jackie Nowicki explores our work on virtual charter schools.

Racial/ethnic composition of schools and bullying contribute to equity issues

In a July report , we found that while the U.S. student population has become significantly more diverse, many schools remain divided along racial, ethnic, and economic lines.

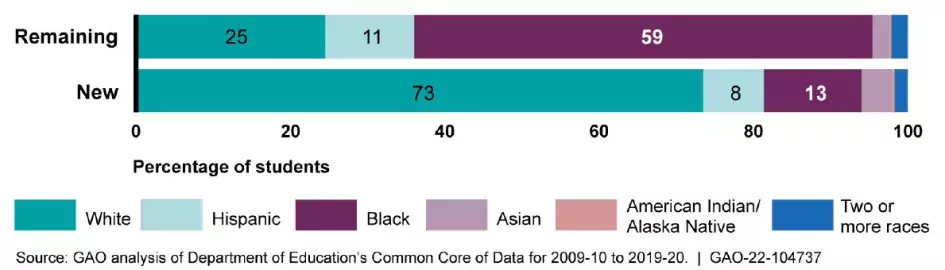

Our recent analysis of 10 years of the Department of Education’s data on student race and ethnicity also shows that when schools broke away from their school districts, it generally resulted in Whiter and wealthier districts.

Specifically, new districts had half the share of students receiving free or reduced price lunches compared to the remaining districts. They also had far larger shares of White students, and far smaller shares of Hispanic and Black students than the remaining districts.

Racial/Ethnic Composition of New and Remaining Districts One Year after District Secession

Wealth and racial composition of schools matter.

It is widely known that a history of discriminatory practices has contributed to inequities in education, which are intertwined with disparities in wealth, income, and housing. We have previously reported that students who are poor, Black, or Hispanic generally attend schools with fewer resources and lower academic outcomes (about 80% of students attending low-income schools are Black or Hispanic).

Racial and ethnic minority students may face other obstacles in school beyond resources and quality of education. Each year, millions of K-12 students experience hostile behaviors like bullying, hate speech, hate crimes, or assault.

In a report published last November, we found that, during the 2018-19 school year, about 1.3 million students (ages 12 to 18) were bullied for their race, religion, national origin, disability, gender, or sexual orientation.

The Department of Education has resolved complaints about these hostile behaviors more quickly than in the past, largely because it dismissed more complaints than in previous years, and because the number of complaints filed declined overall. Some civil rights experts said they had become reluctant to file complaints because they lost confidence in the department’s ability to address these violations in schools.

To learn more about our findings on bullying, hate crimes, and violence in K-12 schools, check out our podcast:

While students will face significant obstacles this fall, their teachers are confronting burnout and concerns about teacher shortages abound. Our recent discussions with current and former teachers, as well as hiring officials and others involved in all levels of teacher recruitment and retention, will help shed light on the situation and ways to address it.

Keep an eye out for these findings and a report on discipline related to school dress code violations this fall.

- Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact [email protected] .

GAO Contacts

Related Posts

Back to School—Obstacles to Educating K-12 Students Persist

As Cyberattacks Increase on K-12 Schools, Here Is What’s Being Done

The Three Rs of Pandemic Learning: Roadblocks, Resilience, and Resources

Related products, k-12 education: students' experiences with bullying, hate speech, hate crimes, and victimization in schools, product number, k-12 education: student population has significantly diversified, but many schools remain divided along racial, ethnic, and economic lines, k-12 education: an estimated 1.1 million teachers nationwide had at least one student who never showed up for class in the 2020-21 school year [reissued with revisions on apr. 19, 2022].

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to [email protected] .

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

How covid taught america about inequity in education.

Harvard Correspondent

Remote learning turned spotlight on gaps in resources, funding, and tech — but also offered hints on reform

“Unequal” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. This part looks at how the pandemic called attention to issues surrounding the racial achievement gap in America.

The pandemic has disrupted education nationwide, turning a spotlight on existing racial and economic disparities, and creating the potential for a lost generation. Even before the outbreak, students in vulnerable communities — particularly predominately Black, Indigenous, and other majority-minority areas — were already facing inequality in everything from resources (ranging from books to counselors) to student-teacher ratios and extracurriculars.

The additional stressors of systemic racism and the trauma induced by poverty and violence, both cited as aggravating health and wellness as at a Weatherhead Institute panel , pose serious obstacles to learning as well. “Before the pandemic, children and families who are marginalized were living under such challenging conditions that it made it difficult for them to get a high-quality education,” said Paul Reville, founder and director of the Education Redesign Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE).

Educators hope that the may triggers a broader conversation about reform and renewed efforts to narrow the longstanding racial achievement gap. They say that research shows virtually all of the nation’s schoolchildren have fallen behind, with students of color having lost the most ground, particularly in math. They also note that the full-time reopening of schools presents opportunities to introduce changes and that some of the lessons from remote learning, particularly in the area of technology, can be put to use to help students catch up from the pandemic as well as to begin to level the playing field.

The disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 outbreak became apparent from the first shutdowns. “The good news, of course, is that many schools were very fast in finding all kinds of ways to try to reach kids,” said Fernando M. Reimers , Ford Foundation Professor of the Practice in International Education and director of GSE’s Global Education Innovation Initiative and International Education Policy Program. He cautioned, however, that “those arrangements don’t begin to compare with what we’re able to do when kids could come to school, and they are particularly deficient at reaching the most vulnerable kids.” In addition, it turned out that many students simply lacked access.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right. You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it,” says Fernando Reimers of the Graduate School of Education.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

The rate of limited digital access for households was at 42 percent during last spring’s shutdowns, before drifting down to about 31 percent this fall, suggesting that school districts improved their adaptation to remote learning, according to an analysis by the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge of U.S. Census data. (Indeed, Education Week and other sources reported that school districts around the nation rushed to hand out millions of laptops, tablets, and Chromebooks in the months after going remote.)

The report also makes clear the degree of racial and economic digital inequality. Black and Hispanic households with school-aged children were 1.3 to 1.4 times as likely as white ones to face limited access to computers and the internet, and more than two in five low-income households had only limited access. It’s a problem that could have far-reaching consequences given that young students of color are much more likely to live in remote-only districts.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right,” said Reimers. “You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it.” Too many students, he said, “have no connectivity. They have no devices, or they have no home circumstances that provide them support.”

The issues extend beyond the technology. “There is something wonderful in being in contact with other humans, having a human who tells you, ‘It’s great to see you. How are things going at home?’” Reimers said. “I’ve done 35 case studies of innovative practices around the world. They all prioritize social, emotional well-being. Checking in with the kids. Making sure there is a touchpoint every day between a teacher and a student.”

The difference, said Reville, is apparent when comparing students from different economic circumstances. Students whose parents “could afford to hire a tutor … can compensate,” he said. “Those kids are going to do pretty well at keeping up. Whereas, if you’re in a single-parent family and mom is working two or three jobs to put food on the table, she can’t be home. It’s impossible for her to keep up and keep her kids connected.

“If you lose the connection, you lose the kid.”

“COVID just revealed how serious those inequities are,” said GSE Dean Bridget Long , the Saris Professor of Education and Economics. “It has disproportionately hurt low-income students, students with special needs, and school systems that are under-resourced.”

This disruption carries throughout the education process, from elementary school students (some of whom have simply stopped logging on to their online classes) through declining participation in higher education. Community colleges, for example, have “traditionally been a gateway for low-income students” into the professional classes, said Long, whose research focuses on issues of affordability and access. “COVID has just made all of those issues 10 times worse,” she said. “That’s where enrollment has fallen the most.”

In addition to highlighting such disparities, these losses underline a structural issue in public education. Many schools are under-resourced, and the major reason involves sources of school funding. A 2019 study found that predominantly white districts got $23 billion more than their non-white counterparts serving about the same number of students. The discrepancy is because property taxes are the primary source of funding for schools, and white districts tend to be wealthier than those of color.

The problem of resources extends beyond teachers, aides, equipment, and supplies, as schools have been tasked with an increasing number of responsibilities, from the basics of education to feeding and caring for the mental health of both students and their families.

“You think about schools and academics, but what COVID really made clear was that schools do so much more than that,” said Long. A child’s school, she stressed “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care.”

“You think about schools and academics” … but a child’s school “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care,” stressed GSE Dean Bridget Long.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

This safety net has been shredded just as more students need it. “We have 400,000 deaths and those are disproportionately affecting communities of color,” said Long. “So you can imagine the kids that are in those households. Are they able to come to school and learn when they’re dealing with this trauma?”

The damage is felt by the whole families. In an upcoming paper, focusing on parents of children ages 5 to 7, Cindy H. Liu, director of Harvard Medical School’s Developmental Risk and Cultural Disparities Laboratory , looks at the effects of COVID-related stress on parent’ mental health. This stress — from both health risks and grief — “likely has ramifications for those groups who are disadvantaged, particularly in getting support, as it exacerbates existing disparities in obtaining resources,” she said via email. “The unfortunate reality is that the pandemic is limiting the tangible supports [like childcare] that parents might actually need.”

Educators are overwhelmed as well. “Teachers are doing a phenomenal job connecting with students,” Long said about their performance online. “But they’ve lost the whole system — access to counselors, access to additional staff members and support. They’ve lost access to information. One clue is that the reporting of child abuse going down. It’s not that we think that child abuse is actually going down, but because you don’t have a set of adults watching and being with kids, it’s not being reported.”

The repercussions are chilling. “As we resume in-person education on a normal basis, we’re dealing with enormous gaps,” said Reville. “Some kids will come back with such educational deficits that unless their schools have a very well thought-out and effective program to help them catch up, they will never catch up. They may actually drop out of school. The immediate consequences of learning loss and disengagement are going to be a generation of people who will be less educated.”

There is hope, however. Just as the lockdown forced teachers to improvise, accelerating forms of online learning, so too may the recovery offer options for educational reform.

The solutions, say Reville, “are going to come from our community. This is a civic problem.” He applauded one example, the Somerville, Mass., public library program of outdoor Wi-Fi “pop ups,” which allow 24/7 access either through their own or library Chromebooks. “That’s the kind of imagination we need,” he said.

On a national level, he points to the creation of so-called “Children’s Cabinets.” Already in place in 30 states, these nonpartisan groups bring together leaders at the city, town, and state levels to address children’s needs through schools, libraries, and health centers. A July 2019 “ Children’s Cabinet Toolkit ” on the Education Redesign Lab site offers guidance for communities looking to form their own, with sample mission statements from Denver, Minneapolis, and Fairfax, Va.

Already the Education Redesign Lab is working on even more wide-reaching approaches. In Tennessee, for example, the Metro Nashville Public Schools has launched an innovative program, designed to provide each student with a personalized education plan. By pairing these students with school “navigators” — including teachers, librarians, and instructional coaches — the program aims to address each student’s particular needs.

“This is a chance to change the system,” said Reville. “By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now.”

“Students have different needs,” agreed Long. “We just have to get a better understanding of what we need to prioritize and where students are” in all aspects of their home and school lives.

“By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now,” says Paul Reville of the GSE.

Already, educators are discussing possible responses. Long and GSE helped create The Principals’ Network as one forum for sharing ideas, for example. With about 1,000 members, and multiple subgroups to address shared community issues, some viable answers have begun to emerge.

“We are going to need to expand learning time,” said Long. Some school systems, notably Texas’, already have begun discussing extending the school year, she said. In addition, Long, an internationally recognized economist who is a member of the National Academy of Education and the MDRC board, noted that educators are exploring innovative ways to utilize new tools like Zoom, even when classrooms reopen.

“This is an area where technology can help supplement what students are learning, giving them extra time — learning time, even tutoring time,” Long said.

Reimers, who serves on the UNESCO Commission on the Future of Education, has been brainstorming solutions that can be applied both here and abroad. These include urging wealthier countries to forgive loans, so that poorer countries do not have to cut back on basics such as education, and urging all countries to keep education a priority. The commission and its members are also helping to identify good practices and share them — globally.

Innovative uses of existing technology can also reach beyond traditional schooling. Reimers cites the work of a few former students who, working with Harvard Global Education Innovation Initiative, HundrED , the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills , and the World Bank Group Education Global Practice, focused on podcasts to reach poor students in Colombia.

They began airing their math and Spanish lessons via the WhatsApp app, which was widely accessible. “They were so humorous that within a week, everyone was listening,” said Reimers. Soon, radio stations and other platforms began airing the 10-minute lessons, reaching not only children who were not in school, but also their adult relatives.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Six receive honorary degrees

Harvard recognizes educator, conductor, theoretical physicist, advocate for elderly, writer, and Nobel laureate

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Bridging social distance, embracing uncertainty, fighting for equity

Student Commencement speeches to tap into themes faced by Class of 2024

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Public education is facing a crisis of epic proportions

How politics and the pandemic put schools in the line of fire

A previous version of this story incorrectly said that 39 percent of American children were on track in math. That is the percentage performing below grade level.

Test scores are down, and violence is up . Parents are screaming at school boards , and children are crying on the couches of social workers. Anger is rising. Patience is falling.

For public schools, the numbers are all going in the wrong direction. Enrollment is down. Absenteeism is up. There aren’t enough teachers, substitutes or bus drivers. Each phase of the pandemic brings new logistics to manage, and Republicans are planning political campaigns this year aimed squarely at failings of public schools.

Public education is facing a crisis unlike anything in decades, and it reaches into almost everything that educators do: from teaching math, to counseling anxious children, to managing the building.

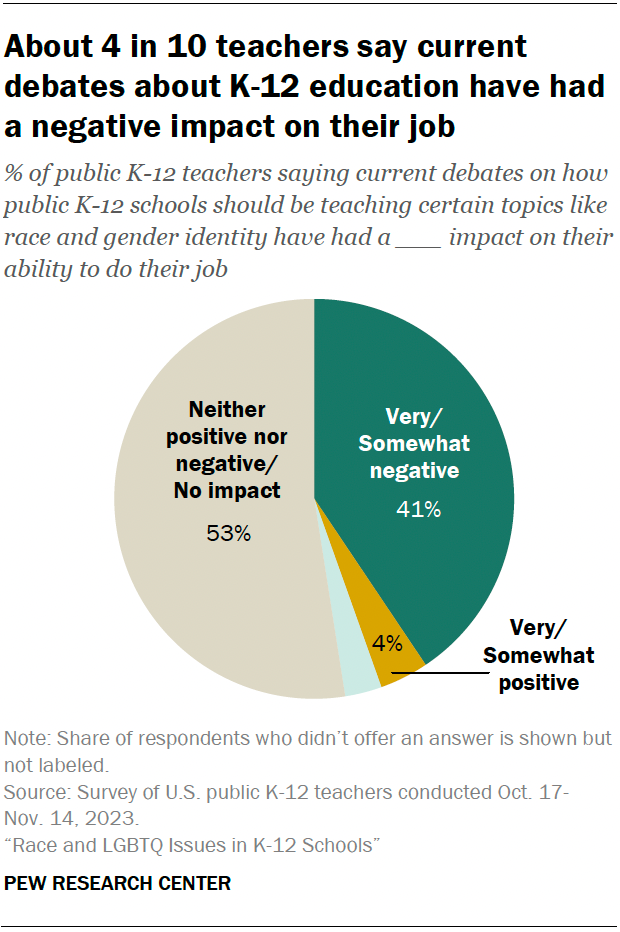

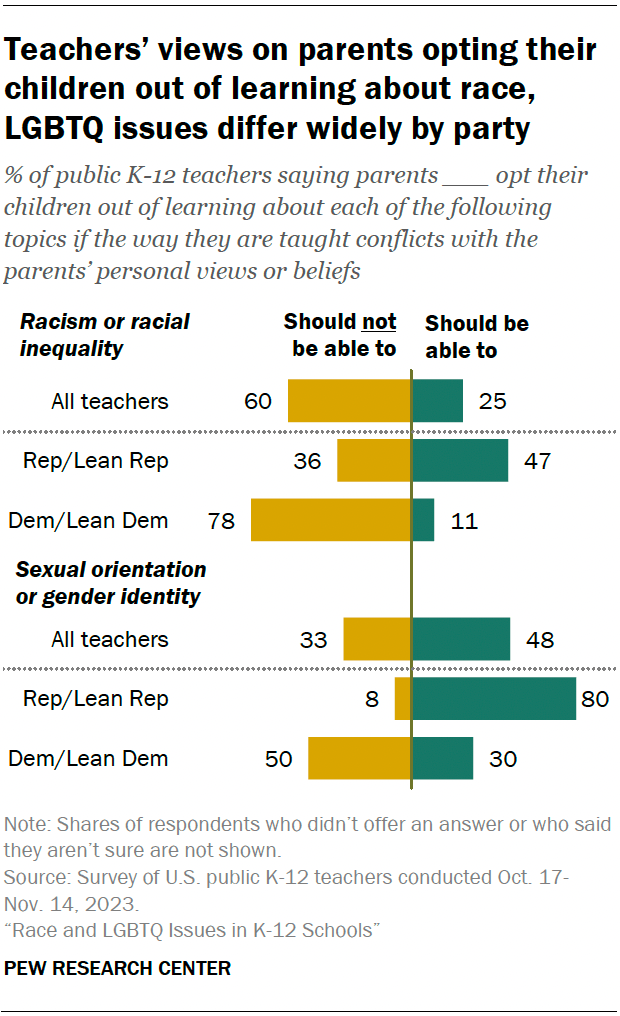

Political battles are now a central feature of education, leaving school boards, educators and students in the crosshairs of culture warriors. Schools are on the defensive about their pandemic decision-making, their curriculums, their policies regarding race and racial equity and even the contents of their libraries. Republicans — who see education as a winning political issue — are pressing their case for more “parental control,” or the right to second-guess educators’ choices. Meanwhile, an energized school choice movement has capitalized on the pandemic to promote alternatives to traditional public schools.

“The temperature is way up to a boiling point,” said Nat Malkus, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative-leaning think tank. “If it isn’t a crisis now, you never get to crisis.”

Experts reach for comparisons. The best they can find is the earthquake following Brown v. Board of Education , when the Supreme Court ordered districts to desegregate and White parents fled from their cities’ schools. That was decades ago.

Today, the cascading problems are felt acutely by the administrators, teachers and students who walk the hallways of public schools across the country. Many say they feel unprecedented levels of stress in their daily lives.

Remote learning, the toll of illness and death, and disruptions to a dependable routine have left students academically behind — particularly students of color and those from poor families. Behavior problems ranging from inability to focus in class all the way to deadly gun violence have gripped campuses. Many students and teachers say they are emotionally drained, and experts predict schools will be struggling with the fallout for years to come.

Teresa Rennie, an eighth-grade math and science teacher in Philadelphia, said in 11 years of teaching, she has never referred this many children to counseling.

“So many students are needy. They have deficits academically. They have deficits socially,” she said. Rennie said that she’s drained, too. “I get 45 minutes of a prep most days, and a lot of times during that time I’m helping a student with an assignment, or a child is crying and I need to comfort them and get them the help they need. Or there’s a problem between two students that I need to work with. There’s just not enough time.”

Many wonder: How deep is the damage?

Learning lost

At the start of the pandemic, experts predicted that students forced into remote school would pay an academic price. They were right.

“The learning losses have been significant thus far and frankly I’m worried that we haven’t stopped sinking,” said Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the American Institutes for Research.

Some of the best data come from the nationally administered assessment called i-Ready, which tests students three times a year in reading and math, allowing researchers to compare performance of millions of students against what would be expected absent the pandemic. It found significant declines, especially among the youngest students and particularly in math.

The low point was fall 2020, when all students were coming off a spring of chaotic, universal remote classes. By fall 2021 there were some improvements, but even then, academic performance remained below historic norms.

Take third grade, a pivotal year for learning and one that predicts success going forward. In fall 2021, 38 percent of third-graders were below grade level in reading, compared with 31 percent historically. In math, 39 percent of students were below grade level, vs. 29 percent historically.

Damage was most severe for students from the lowest-income families, who were already performing at lower levels.

A McKinsey & Co. study found schools with majority-Black populations were five months behind pre-pandemic levels, compared with majority-White schools, which were two months behind. Emma Dorn, a researcher at McKinsey, describes a “K-shaped” recovery, where kids from wealthier families are rebounding and those in low-income homes continue to decline.

“Some students are recovering and doing just fine. Other people are not,” she said. “I’m particularly worried there may be a whole cohort of students who are disengaged altogether from the education system.”

A hunt for teachers, and bus drivers

Schools, short-staffed on a good day, had little margin for error as the omicron variant of the coronavirus swept over the country this winter and sidelined many teachers. With a severe shortage of substitutes, teachers had to cover other classes during their planning periods, pushing prep work to the evenings. San Francisco schools were so strapped that the superintendent returned to the classroom on four days this school year to cover middle school math and science classes. Classes were sometimes left unmonitored or combined with others into large groups of unglorified study halls.

“The pandemic made an already dire reality even more devastating,” said Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, referring to the shortages.

In 2016, there were 1.06 people hired for every job listing. That figure has steadily dropped, reaching 0.59 hires for each opening last year, Bureau of Labor Statistics data show. In 2013, there were 557,320 substitute teachers, the BLS reported. In 2020, the number had fallen to 415,510. Virtually every district cites a need for more subs.

It’s led to burnout as teachers try to fill in the gaps.

“The overall feelings of teachers right now are ones of just being exhausted, beaten down and defeated, and just out of gas. Expectations have been piled on educators, even before the pandemic, but nothing is ever removed,” said Jennifer Schlicht, a high school teacher in Olathe, Kan., outside Kansas City.

Research shows the gaps in the number of available educators are most acute in areas including special education and educators who teach English language learners, as well as substitutes. And all school year, districts have been short on bus drivers , who have been doubling up routes, and forcing late school starts and sometimes cancellations for lack of transportation.

Many educators predict that fed-up teachers will probably quit, exacerbating the problem. And they say political attacks add to the burnout. Teachers are under scrutiny over lesson plans, and critics have gone after teachers unions, which for much of the pandemic demanded remote learning.

“It’s just created an environment that people don’t want to be part of anymore,” said Daniel A. Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “People want to take care of kids, not to be accused and punished and criticized.”

Falling enrollment

Traditional public schools educate the vast majority of American children, but enrollment has fallen, a worrisome trend that could have lasting repercussions. Enrollment in traditional public schools fell to less than 49.4 million students in fall 2020 , a 2.7 percent drop from a year earlier .

National data for the current school year is not yet available. But if the trend continues, that will mean less money for public schools as federal and state funding are both contingent on the number of students enrolled. For now, schools have an infusion of federal rescue money that must be spent by 2024.

Some students have shifted to private or charter schools. A rising number , especially Black families , opted for home schooling. And many young children who should have been enrolling in kindergarten delayed school altogether. The question has been: will these students come back?

Some may not. Preliminary data for 19 states compiled by Nat Malkus, of the American Enterprise Institute, found seven states where enrollment dropped in fall 2020 and then dropped even further in 2021. His data show 12 states that saw declines in 2020 but some rebounding in 2021 — though not one of them was back to 2019 enrollment levels.

Joshua Goodman, associate professor of education and economics at Boston University, studied enrollment in Michigan schools and found high-income, White families moved to private schools to get in-person school. Far more common, though, were lower-income Black families shifting to home schooling or other remote options because they were uncomfortable with the health risks of in person.

“Schools were damned if they did, and damned if they didn’t,” Goodman said.

At the same time, charter schools, which are privately run but publicly funded, saw enrollment increase by 7 percent, or nearly 240,000 students, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. There’s also been a surge in home schooling. Private schools saw enrollment drop slightly in 2020-21 but then rebound this academic year, for a net growth of 1.7 percent over two years, according to the National Association of Independent Schools, which represents 1,600 U.S. schools.

Absenteeism on the rise

Even if students are enrolled, they won’t get much schooling if they don’t show up.

Last school year, the number of students who were chronically absent — meaning they have missed more than 10 percent of school days — nearly doubled from before the pandemic, according to data from a variety of states and districts studied by EveryDay Labs, a company that works with districts to improve attendance.

This school year, the numbers got even worse.

In Connecticut, for instance, the number of chronically absent students soared from 12 percent in 2019-20 to 20 percent the next year to 24 percent this year, said Emily Bailard, chief executive of the company. In Oakland, Calif., they went from 17.3 percent pre-pandemic to 19.8 percent last school year to 43 percent this year. In Pittsburgh, chronic absences stayed where they were last school year at about 25 percent, then shot up to 45 percent this year.

“We all expected that this year would look much better,” Bailard said. One explanation for the rise may be that schools did not keep careful track of remote attendance last year and the numbers understated the absences then, she said.

The numbers were the worst for the most vulnerable students. This school year in Connecticut, for instance, 24 percent of all students were chronically absent, but the figure topped 30 percent for English-learners, students with disabilities and those poor enough to qualify for free lunch. Among students experiencing homelessness, 56 percent were chronically absent.

Fights and guns

Schools are open for in-person learning almost everywhere, but students returned emotionally unsettled and unable to conform to normally accepted behavior. At its most benign, teachers are seeing kids who cannot focus in class, can’t stop looking at their phones, and can’t figure out how to interact with other students in all the normal ways. Many teachers say they seem younger than normal.

Amy Johnson, a veteran teacher in rural Randolph, Vt., said her fifth-graders had so much trouble being together that the school brought in a behavioral specialist to work with them three hours each week.

“My students are not acclimated to being in the same room together,” she said. “They don’t listen to each other. They cannot interact with each other in productive ways. When I’m teaching I might have three or five kids yelling at me all at the same time.”

That loss of interpersonal skills has also led to more fighting in hallways and after school. Teachers and principals say many incidents escalate from small disputes because students lack the habit of remaining calm. Many say the social isolation wrought during remote school left them with lower capacity to manage human conflict.

Just last week, a high-schooler in Los Angeles was accused of stabbing another student in a school hallway, police on the big island of Hawaii arrested seven students after an argument escalated into a fight, and a Baltimore County, Md., school resource officer was injured after intervening in a fight during the transition between classes.

There’s also been a steep rise in gun violence. In 2021, there were at least 42 acts of gun violence on K-12 campuses during regular hours, the most during any year since at least 1999, according to a Washington Post database . The most striking of 2021 incidents was the shooting in Oxford, Mich., that killed four. There have been already at least three shootings in 2022.

Back to school has brought guns, fighting and acting out

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security, which maintains its own database of K-12 school shootings using a different methodology, totaled nine active shooter incidents in schools in 2021, in addition to 240 other incidents of gunfire on school grounds. So far in 2022, it has recorded 12 incidents. The previous high, in 2019, was 119 total incidents.

David Riedman, lead researcher on the K-12 School Shooting Database, points to four shootings on Jan. 19 alone, including at Anacostia High School in D.C., where gunshots struck the front door of the school as a teen sprinted onto the campus, fleeing a gunman.

Seeing opportunity

Fueling the pressure on public schools is an ascendant school-choice movement that promotes taxpayer subsidies for students to attend private and religious schools, as well as publicly funded charter schools, which are privately run. Advocates of these programs have seen the public system’s woes as an excellent opportunity to push their priorities.

EdChoice, a group that promotes these programs, tallies seven states that created new school choice programs last year. Some are voucher-type programs where students take some of their tax dollars with them to private schools. Others offer tax credits for donating to nonprofit organizations, which give scholarships for school expenses. Another 15 states expanded existing programs, EdChoice says.

The troubles traditional schools have had managing the pandemic has been key to the lobbying, said Michael McShane, director of national research for EdChoice. “That is absolutely an argument that school choice advocates make, for sure.”

If those new programs wind up moving more students from public to private systems, that could further weaken traditional schools, even as they continue to educate the vast majority of students.

Kevin G. Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado, who opposes school choice programs, sees the surge of interest as the culmination of years of work to undermine public education. He is both impressed by the organization and horrified by the results.

“I wish that organizations supporting public education had the level of funding and coordination that I’ve seen in these groups dedicated to its privatization,” he said.

A final complication: Politics

Rarely has education been such a polarizing political topic.

Republicans, fresh off Glenn Youngkin’s victory in the Virginia governor’s race, have concluded that key to victory is a push for parental control and “parents rights.” That’s a nod to two separate topics.

First, they are capitalizing on parent frustrations over pandemic policies, including school closures and mandatory mask policies. The mask debate, which raged at the start of the school year, got new life this month after Youngkin ordered Virginia schools to allow students to attend without face coverings.

The notion of parental control also extends to race, and objections over how American history is taught. Many Republicans also object to school districts’ work aimed at racial equity in their systems, a basket of policies they have dubbed critical race theory. Critics have balked at changes in admissions to elite school in the name of racial diversity, as was done in Fairfax, Va. , and San Francisco ; discussion of White privilege in class ; and use of the New York Times’s “1619 Project,” which suggests slavery and racism are at the core of American history.

“Everything has been politicized,” said Domenech, of AASA. “You’re beside yourself saying, ‘How did we ever get to this point?’”

Part of the challenge going forward is that the pandemic is not over. Each time it seems to be easing, it returns with a variant vengeance, forcing schools to make politically and educationally sensitive decisions about the balance between safety and normalcy all over again.

At the same time, many of the problems facing public schools feed on one another. Students who are absent will probably fall behind in learning, and those who fall behind are likely to act out.

A similar backlash exists regarding race. For years, schools have been under pressure to address racism in their systems and to teach it in their curriculums, pressure that intensified after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Many districts responded, and that opened them up to countervailing pressures from those who find schools overly focused on race.

Some high-profile boosters of public education are optimistic that schools can move past this moment. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona last week promised, “It will get better.” Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said, “If we can rebuild community-education relations, if we can rebuild trust, public education will not only survive but has a real chance to thrive.”

But the path back is steep, and if history is a guide, the wealthiest schools will come through reasonably well, while those serving low-income communities will struggle. Steve Matthews, superintendent of the 6,900-student Novi Community School District in Michigan, just northwest of Detroit, said his district will probably face a tougher road back than wealthier nearby districts that are, for instance, able to pay teachers more.

“Resource issues. Trust issues. De-professionalization of teaching is making it harder to recruit teachers,” he said. “A big part of me believes schools are in a long-term crisis.”

Valerie Strauss contributed to this report.

The pandemic’s impact on education

The latest: Updated coronavirus booster shots are now available for children as young as 5 . To date, more than 10.5 million children have lost one or both parents or caregivers during the coronavirus pandemic.

In the classroom: Amid a teacher shortage, states desperate to fill teaching jobs have relaxed job requirements as staffing crises rise in many schools . American students’ test scores have even plummeted to levels unseen for decades. One D.C. school is using COVID relief funds to target students on the verge of failure .

Higher education: College and university enrollment is nowhere near pandemic level, experts worry. ACT and SAT testing have rebounded modestly since the massive disruptions early in the coronavirus pandemic, and many colleges are also easing mask rules .

DMV news: Most of Prince George’s students are scoring below grade level on district tests. D.C. Public School’s new reading curriculum is designed to help improve literacy among the city’s youngest readers.

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

FACT SHEET: Biden- Harris Administration Highlights Efforts to Support K-12 Education as Students go Back-to-School

The President and First Lady will mark the start of the school year by visiting students at Eliot-Hine Middle School in Washington, D.C. When President Biden took office, less than half of K-12 students were going to school in person. Today, thanks to the President’s swift actions and historic investments, every school in America is open safely for in-person instruction. Since Day One, President Biden has worked to help every school open safely for in-person instruction, accelerate academic achievement, and build communities where all students feel they belong. The actions the President has taken to support schools and the students they serve, include: Securing the Largest Investment in Public Education in History to Help Students Get Back to School and Recover Academically: COVID-19 created unprecedented challenges for kids, from school closures to lost instructional time and social isolation from their peers. To support the immediate response and the long-term recovery work our students need, the President secured $130 billion through the American Rescue Plan (ARP) to help schools safely reopen, stay open, and address the academic and mental health needs of students. American Rescue Plan funding has put more teachers in our classrooms and more counselors, social workers, and other staff in our schools; is providing high-quality tutoring; supporting record expansion of summer and after-school programming; supporting HVAC improvements within school buildings to address air quality and environmental and safety needs in aging school buildings; and providing a wide range of student supports. Compared with the pre-pandemic period, as of the end of last year school year, the number of public school social workers is up 39% and the number of public school nurses is up 30%. Nearly half of school districts using these funds to expand summer learning programs have shown clear gains in math. While we have further to go, we are seeing increased evidence of improvement, including several states returning to pre-pandemic levels of achievement on their state math and literacy assessments. Expanding Access to Mental Health Support in Schools Across the Country: Students around the nation continue to grapple with mental health challenges. Rates of depression, anxiety, and feelings of hopelessness were already on the rise, but unprecedented disruptions in their school and social lives in the past years, have exacerbated these concerns. That’s why the President named tackling the mental health crisis, particularly among America’s young people, a top priority. Last year, the President signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) into law last year as the first major federal gun safety bill passed in nearly 30 years. BSCA included historic levels of funding to address youth mental health, including $2 billion for ED to create safe, inclusive learning environments for students and hire and train more mental health professionals for schools – where students are most likely to receive these crucial services. ED has awarded $286 million to date across 264 grantees in 48 states and DC to support mental health services in schools – investments that are estimated to support more than 14,000 new mental health professionals in schools in the coming years. ED is also working closely with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to further extend the reach of Federal mental health programs and investments into schools, and to leverage Medicaid funding to provide crucial health and mental health services at schools. Earlier this year, the Administration released comprehensive guidance to make it easier for schools to bill Medicaid, including proposing a rule that would streamline Medicaid billing permissions to deliver mental health services to students. The Administration also launched a technical assistance center to help schools take advantage of this crucial funding stream – which supported an additional investment of more than $6 billion in schools in 2022. Expanding Community Schools that Improve Academic Success: Meeting the needs of the whole child is essential to help America’s students grow academically and improve their well-being. That’s why the President is committed to increasing and supporting the adoption of community school models across the country. Full-Service Community Schools leverage local non-profit, private sector, and public partnerships to bring wraparound services into school buildings, such as health services, and assistance with shelter and nutrition. Research has shown that these schools contribute to increased student attendance, on-time grade progression, and high school graduation. Because of the President’s commitment to this model, federal funding for this model has increased five-fold over the course of this Administration. While the program supported 170 schools before 2021 it is now reaching more than 1,700 schools serving almost 800,000 students. Additionally, agencies across the federal government have also identified the ways that additional resources can support the expansion of this model and further integrate wraparound supports into our schools. Expanding Teacher and Staff Capacity by Bringing in Tutors and Mentors: To provide students with the support they need to recover from the impacts of the pandemic, the President issued a call to action to bring 250,000 more tutors, mentors and other critical supports into schools over three years. Last summer, the Department of Education (ED), AmeriCorps, and the Johns Hopkins University’s Everyone Graduates Center launched the National Partnership for Student Success (NPSS), a public-private partnership to accomplish this goal. To support this effort, ED recently launched a call to action to colleges, encouraging them to devote a greater share of their Federal Work-Study funds to bring college students into K-12 schools as tutors and in other high-impact roles. Early adopters include more than two dozen colleges ranging from large public university systems, like the State University of New York, to Howard University and Hispanic-serving institutions. In the coming weeks, the NPSS will highlight progress towards the President’s goal during the 2022-2023 school year. Growing an Effective Teacher and School Leadership Workforce: From February to May 2020, communities lost 730,000 local public education jobs during the pandemic—a 9 percent decline in local public education employment—including teachers, specialized instructional support personnel, and other critical staff. As of June 2023, local public education employment has increased by 635,000 jobs since its low point in May 2020. This significant rebound now means that there are now only 1.2 percent fewer individuals working in local public education than before the pandemic; this progress has been significantly fueled by investments in educators through the American Rescue Plan and other Administration investments. The President has prioritized building an effective, diverse teacher pipeline, including by expanding high-quality and affordable programs that prepare and support teachers, including teacher Registered Apprenticeships. Registered Apprenticeship can be an effective, high-quality “earn and learn” model that allows prospective teachers to earn their credential while earning a salary by combining coursework with structured, paid on-the-job learning experiences with a mentor teacher. The Administration has worked closely with States to grow the number of registered apprenticeship programs for teachers from 2 to 23, with bipartisan Governors across the country scaling this effective model. The Department has also advanced teacher diversity by including priorities focused on educator diversity in 14 grant programs, totaling over $470 million and funding; for the first time, funding a teacher preparation program for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges or Universities (TCUs), and Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) to help accelerate the pace of preparing teachers of color for America’s schools. The Department’s Raise the Bar Policy Brief highlights progress by states across the country, with the support of the Administration, in advancing key strategies to eliminate educator shortages in the long term. Directing Resources to Historically Underserved Schools and Students: The President’s leadership has garnered substantial increases for Federal student support programs to meet the needs of historically underserved students. The President has secured a nearly $2 billion (or 11%) increase in Title I funds, which delivers critical resources to 90 percent of school districts across the Nation and helps them provide students in low-income communities with necessary academic opportunities and supports. Additionally, the President has secured a historic $1.3 billion (or 10%) increase in Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) funds, which helps States support special education instruction and services for 7.4 million students with disabilities, and increased funding by $92 million for programs that support English learners. The Administration has also increased funding to support subpopulations of students, including Alaska Native Education and Native Hawaiian Education programs which have increased by over 20%.

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

These teens were missing too much school. Here's what it took to get them back

Leigh Paterson

Elizabeth Miller

Sophomore Neomi sits quietly in an office at her high school in a Colorado mountain town west of Denver. It's a cold December morning and she's wearing gold and black Nikes and a gray hoodie, pulled up.

She's surrounded by school staff and her mom.

"I just wanna be really clear about the intention of this meeting. It's not to make you feel bad," says Dave, a school administrator.

"What's going on?" he asks Neomi. "Why aren't we coming to school? Because you were coming to school quite a bit, and then all of a sudden..."

As Neomi listens, tears roll down her cheeks.

"Do you not feel safe? Are you stressed?" Dave asks softly.

Finally, in a quiet voice, the teen says, "I don't have friends. I don't have any people."

Listen: How one school is trying to improve attendance of chronically absent students

How one school is trying to improve attendance of chronically absent students.

Neomi has been chronically absent, which means, at the time of this meeting, she had already missed 10% or more of the school year. The teen is part of an alarming trend among the country's K-12 students.

Chronic absenteeism skyrocketed nationwide during the pandemic. In the 2022-'23 academic year, 26% of U.S. students were chronically absent, according to research from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). Before the pandemic, only 15% of students were regularly missing school.

In some places, like Colorado and Oregon, the rates of chronic absenteeism are even higher.

Research has shown there's a link between irregular attendance and not graduating – and attendance can be a better predictor of a student's drop-out risk than test scores.

"The flip side of it [is] kids with high attendance are much more likely to stay on track and graduate with their peers," says Johann Liljengren, director of dropout prevention for the Colorado Department of Education.

Going beyond academics to help solve absenteeism

Getting chronically absent students back to class is a priority for schools. It requires support from families and teachers, as well as difficult, personal conversations – like the kind Dave and Neomi are having in Colorado.

NPR is only using the teen's middle name so this conversation about her attendance doesn't hurt future job or academic prospects. To further protect her identity, we aren't naming her school or her mom, and we're only using the administrator's first name.

K-12 students learned a lot last year, but they're still missing too much school

Neomi and her family came to Colorado from El Salvador. At the December meeting, a school staffer interprets for Neomi's mom, who has been listening quietly.

When Dave points out that the teen hasn't been in school much since Thanksgiving, Neomi's mom speaks up to explain what her daughter has been going through.

"She doesn't want to come here because she was dating this kid and they broke up," she says through the interpreter. "Everybody is bullying or laughing or talking: 'Well, after being the perfect couple, look at you.' "

Neomi's mom tried to get help for her daughter.

"I was trying to find resources to try to find a therapist," she says through the interpreter.

Dave tells her he can help with that. He knows, through student interviews, that health, including mental health, was among the top reasons around half of all students in this rural district were chronically absent during the 2022-'23 school year.

Other reasons include family responsibilities, transportation issues and jobs.

"So everything from working at, you know, Walmart to helping parents with their cleaning businesses," Dave explains. "They're working till really late at night. And then, you know, getting up in the morning is tough."

For Neomi, the hardest part of coming to school is running into students in the hallways and at lunchtime. With this key information, staffers get to work on some solutions that could help bring the teenager back.

They offer to give her a pass to leave class early so she can avoid the students who have been teasing her.

Dave suggests finding a classroom where she can eat lunch, and school staff offer to stay in touch over a messaging app.

They try to get Neomi to stay for the rest of the school day, but she says she isn't ready. Though she promises to come back on Monday, after the weekend.

What it looks like to come back from absenteeism

Anais and her mom agree Anais' sophomore year was a low point in her high school career: She missed more than a month of classes, which set her back academically and put her at risk of not graduating on time, a common consequence of chronic absenteeism in Oregon .

Anais is currently a junior at David Douglas High School in southeast Portland, Ore.

Battling student absenteeism with grandmas, vans and a lot of love

On a Friday after school back in February, the bubbly 17-year-old and her mom, Josette, are outside, in front of their apartment complex, joking around.

She and her mom go back and forth on how they'd grade Anais' attendance last year.

Josette gives her daughter a D.

"From January to June, you were not there a lot," she says.

Anais is harder on herself: "I would say a D-minus."

Last school year, Anais was sick a lot, but, like Neomi, she was also going through a breakup. Both kept her from school for days at a time.

NPR is not using Anais' full name so she can talk openly about her attendance without hurting future academic or job prospects. To further protect her identity, we also aren't fully naming her mom, Josette.

Chronic absenteeism at Anais' high school was at 44% in 2023, well above AEI's national average.

For Anais, missing so much school hurt her grades and changed her friendships. She says her teachers tried to help – "The teachers really did try their best with me with not showing up" — but there wasn't much they could do.

But this year has been different. Her attendance is back up, and Anais has been working on her grades.

What changed? She hasn't been sick as much this year – and she also got back together with her boyfriend.

Josette doesn't love that the boyfriend continues to play a role in her daughter's attendance. She's quick to remind Anais that school is a priority.

"I do talk to her about not letting things get in the way of her education," Josette says.

After so many absences, getting back on track to graduate goes beyond just showing up. Anais has been taking a credit recovery class after school to make up for what she missed during her sophomore year. She plans to attend summer school too, if that's what it takes to finish on time.

Josette has faith her daughter will pull it off. If she does, Anais would be the first of her five siblings to graduate from a traditional high school.

At that point, Anais jokes, "You're pretty much a grown adult."

Back on track

One thing both Anais and her mom can agree on is how they'd grade Anais' attendance this school year: Both give it an A.

As the school year winds down in Colorado, Neomi's attendance has also turned around. Dave says she missed school the Monday after the meeting, but she did make it on Tuesday. Since then, she's been coming to school a lot more. Recently the teenager had a two-week stretch of perfect attendance. Dave says school staff did a celebration dance in the hallway.

Leigh Paterson covers youth mental health for KUNC in Northern Colorado, and Elizabeth Miller covers education for OPB in Portland, Ore.

Digital and audio stories edited by: Nicole Cohen Audio stories produced by: Lauren Migaki Visual design and development by: LA Johnson

Four of the biggest problems facing education—and four trends that could make a difference

Eduardo velez bustillo, harry a. patrinos.

In 2022, we published, Lessons for the education sector from the COVID-19 pandemic , which was a follow up to, Four Education Trends that Countries Everywhere Should Know About , which summarized views of education experts around the world on how to handle the most pressing issues facing the education sector then. We focused on neuroscience, the role of the private sector, education technology, inequality, and pedagogy.

Unfortunately, we think the four biggest problems facing education today in developing countries are the same ones we have identified in the last decades .

1. The learning crisis was made worse by COVID-19 school closures

Low quality instruction is a major constraint and prior to COVID-19, the learning poverty rate in low- and middle-income countries was 57% (6 out of 10 children could not read and understand basic texts by age 10). More dramatic is the case of Sub-Saharan Africa with a rate even higher at 86%. Several analyses show that the impact of the pandemic on student learning was significant, leaving students in low- and middle-income countries way behind in mathematics, reading and other subjects. Some argue that learning poverty may be close to 70% after the pandemic , with a substantial long-term negative effect in future earnings. This generation could lose around $21 trillion in future salaries, with the vulnerable students affected the most.

2. Countries are not paying enough attention to early childhood care and education (ECCE)

At the pre-school level about two-thirds of countries do not have a proper legal framework to provide free and compulsory pre-primary education. According to UNESCO, only a minority of countries, mostly high-income, were making timely progress towards SDG4 benchmarks on early childhood indicators prior to the onset of COVID-19. And remember that ECCE is not only preparation for primary school. It can be the foundation for emotional wellbeing and learning throughout life; one of the best investments a country can make.

3. There is an inadequate supply of high-quality teachers

Low quality teaching is a huge problem and getting worse in many low- and middle-income countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 . In addition, in many countries teachers are formally trained and as such qualified, but do not have the minimum pedagogical training. Globally, teachers for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects are the biggest shortfalls.

4. Decision-makers are not implementing evidence-based or pro-equity policies that guarantee solid foundations

It is difficult to understand the continued focus on non-evidence-based policies when there is so much that we know now about what works. Two factors contribute to this problem. One is the short tenure that top officials have when leading education systems. Examples of countries where ministers last less than one year on average are plentiful. The second and more worrisome deals with the fact that there is little attention given to empirical evidence when designing education policies.

To help improve on these four fronts, we see four supporting trends:

1. Neuroscience should be integrated into education policies

Policies considering neuroscience can help ensure that students get proper attention early to support brain development in the first 2-3 years of life. It can also help ensure that children learn to read at the proper age so that they will be able to acquire foundational skills to learn during the primary education cycle and from there on. Inputs like micronutrients, early child stimulation for gross and fine motor skills, speech and language and playing with other children before the age of three are cost-effective ways to get proper development. Early grade reading, using the pedagogical suggestion by the Early Grade Reading Assessment model, has improved learning outcomes in many low- and middle-income countries. We now have the tools to incorporate these advances into the teaching and learning system with AI , ChatGPT , MOOCs and online tutoring.

2. Reversing learning losses at home and at school

There is a real need to address the remaining and lingering losses due to school closures because of COVID-19. Most students living in households with incomes under the poverty line in the developing world, roughly the bottom 80% in low-income countries and the bottom 50% in middle-income countries, do not have the minimum conditions to learn at home . These students do not have access to the internet, and, often, their parents or guardians do not have the necessary schooling level or the time to help them in their learning process. Connectivity for poor households is a priority. But learning continuity also requires the presence of an adult as a facilitator—a parent, guardian, instructor, or community worker assisting the student during the learning process while schools are closed or e-learning is used.

To recover from the negative impact of the pandemic, the school system will need to develop at the student level: (i) active and reflective learning; (ii) analytical and applied skills; (iii) strong self-esteem; (iv) attitudes supportive of cooperation and solidarity; and (v) a good knowledge of the curriculum areas. At the teacher (instructor, facilitator, parent) level, the system should aim to develop a new disposition toward the role of teacher as a guide and facilitator. And finally, the system also needs to increase parental involvement in the education of their children and be active part in the solution of the children’s problems. The Escuela Nueva Learning Circles or the Pratham Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) are models that can be used.

3. Use of evidence to improve teaching and learning

We now know more about what works at scale to address the learning crisis. To help countries improve teaching and learning and make teaching an attractive profession, based on available empirical world-wide evidence , we need to improve its status, compensation policies and career progression structures; ensure pre-service education includes a strong practicum component so teachers are well equipped to transition and perform effectively in the classroom; and provide high-quality in-service professional development to ensure they keep teaching in an effective way. We also have the tools to address learning issues cost-effectively. The returns to schooling are high and increasing post-pandemic. But we also have the cost-benefit tools to make good decisions, and these suggest that structured pedagogy, teaching according to learning levels (with and without technology use) are proven effective and cost-effective .

4. The role of the private sector

When properly regulated the private sector can be an effective education provider, and it can help address the specific needs of countries. Most of the pedagogical models that have received international recognition come from the private sector. For example, the recipients of the Yidan Prize on education development are from the non-state sector experiences (Escuela Nueva, BRAC, edX, Pratham, CAMFED and New Education Initiative). In the context of the Artificial Intelligence movement, most of the tools that will revolutionize teaching and learning come from the private sector (i.e., big data, machine learning, electronic pedagogies like OER-Open Educational Resources, MOOCs, etc.). Around the world education technology start-ups are developing AI tools that may have a good potential to help improve quality of education .

After decades asking the same questions on how to improve the education systems of countries, we, finally, are finding answers that are very promising. Governments need to be aware of this fact.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Consultant, Education Sector, World Bank

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Big Ideas 2021: 10 Broad Trends in K-12 Education in 10 Charts

Each year, for the past four years, Education Week has produced a special report on big ideas in K-12 education. The reports focus on important and timely issues that schools have grappled with in the past 12 months. Not surprisingly, the coronavirus pandemic was a major emphasis in the 2021 edition, Big Ideas for Education’s Urgent Challenges . Initially published in September 2021, this report examined such pandemic-related topics as remote learning, educator stress, and student home environments.

Drawing upon the results of a nationally representative survey of nearly 900 teachers, principals, and district leaders that was incorporated into Education Week’s fourth annual report on big ideas in K-12 education, this Spotlight sums up 10 broad trends in 10 accompanying charts. These ideas include the transformation of educational technology, educators’ knowledge of students’ lives outside of school, and educator stress. Given the time period covered by the survey, all of these broad trends were deeply impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, a theme that resonates throughout this report.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Most families gave up on virtual school. What about students still thriving online?

RIO RANCHO, N.M. – When Ashley Daniels saw her second grade son earn a high score on a test, she knew he had just guessed the answers and gotten lucky. Daniels called his teacher and said he might need some extra support, despite his performance on the test.

It wasn’t just a mother’s intuition. Daniels watched her son take the test from their dining room table.

The second grader attends SpaRRk Academy, a virtual learning program for elementary students created in 2021 by the Rio Rancho School District in New Mexico. Even as doors reopened to brick-and-mortar schools, administrators here saw the continued need for a virtual option in response to lingering concerns about COVID-19 and feedback from some parents that their children had thrived in online learning.

After a tough year, schools are axing virtual learning. Some families want to stay online.

The district assigned 10 full-time teachers to provide live, online classes via Zoom. They also organized an in-person component: Once a week, students would gather in reserved classrooms in a local elementary school for activities such as science experiments, project-based learning and reading groups. More than 250 students signed up for SpaRRk.

But two years in, enrollment had dropped to 87 kids, a 65% decrease. Costs had soared to $11,327 per pupil, a 121% jump from the year before and nearly $3,000 more than the average in this district of roughly 17,000 students. SpaRRk Academy’s future sat on shaky ground; the school board announced in late 2022 that it would vote this spring on whether to shutter the academy altogether.

Virtual schools, once scarce, proliferated because of COVID

Before the pandemic, virtual schools were relatively scarce: 691 fully virtual programs enrolled nearly 294,000 students, accounting for less than 1% of national public school enrollment, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But after most schools shifted their classes online in early 2020, remote learning caught on with some families, including those who preferred to give their children the flexibility of learning from home, or whose children struggled with social anxiety in school buildings or hadn’t found success in traditional learning environments.