Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Considering Audience and Purpose in Academic Writing

Jenn Kepka and Melissa Elston

Learning Objectives:

- Understand the objective of an argumentative or persuasive piece of writing

- Demonstrate persuasive ideas that will appeal to a particular kind of reader or audience

Questions and Purpose

One of the major differences between high school and pre-college learning and the type of learning we emphasize in college is that you’re often given assignments that aren’t clear. This is done in part because instructors want to see what you can draw from an assignment; they want to see some interpretation of the topic, and there is often no one right answer to a writing assignment.

However, this can lead to confusion when you’re faced with what feels like a vague assignment that also seems to have strict grading guidelines. This assignment will help you get started in decoding college writing assignments by providing a list of questions and a checklist you can use to analyze a writing assignment before you get started.

1. Form a Question

Assignments come in a variety of ways. Sometimes, an instructor will present you with a handout that details the assignment, its expectations, and its due dates and other requirements. Sometimes, an instructor might just mention verbally in class that a term paper will be due at an assignment time. Often, you’ll be given an assignment with a set of instructions similar to this:

HISTORY 105: Write a thorough, thoughtful essay in which you discuss the major aims of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency. Use your textbook and in-class discussion notes as sources and guides. Include a conclusion that speculates on Lincoln’s success or failure in terms of these goals.

This assignment, which is drawn from a typical first-year history course, asks students to not only know about Abraham Lincoln but also to know about how to compose a complete, college-level essay. This can seem paralyzing. There’s so much to talk about! But we can break even this short piece of instruction down into bite-sized pieces that make tackling the assignment much easier.

First, from any assignment, we need to Form a Question. Usually, our goal will be to form a single question from the assignment. Looking at the assignment above, you can see there’s no single question already written out. Forming a question from a prompt gives you, the writer, a direction to go automatically. You can answer the question — once you have it.

So let’s compose a question.

You need to first break down the writing assignment. You can do this by highlighting the critical words. These are the words that give specific directions or show expectations.

HISTORY 105: Write a thorough, thoughtful essay in which you discuss the major aims of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency . Use your textbook and in-class discussion notes as sources and guides. Include a conclusion that speculates on Lincoln’s success or failure in terms of these goals.

These are the critical pieces that tell me what I’m going to write about. So, if I were to re-write this as a question, I might say:

What were the major aims of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency? Did he fail or succeed?

Note that you’ve wound up with two questions instead of one. That’s OK; that serves as a reminder that this assignment is asking you to do two separate things:

- Name the goals of Lincoln’s presidency.

- Discuss whether he met those goals.

Some college writing assignments will have questions already stated. Others, like the one above, do not. When there’s already a question, rewrite it in your own words. This will make it easier to get started.

For instance:

Assignment: Does Lincoln deserve the title “Great Emancipator?” What arguments could you put forward support this sobriquet?

Reworded: If Lincoln really deserves to be known as the “Great Emancipator,” what’s the best evidence to back that up?

Rewording this assignment makes it easier to understand. It’s a small thing, but if you’ve ever struggled with getting started on an assignment, you know that the smallest details — like unfamiliar terms (“sobriquet”) — can feel like major road blocks.

We also need to be on the look out for “why” questions. You’ll find a “why” in almost every college assignment you’re given, whether it’s written out or not. Think of the difference between these two questions:

What was the most important day in Harry Potter’s life?

What was the most important day in Harry Potter’s life, and why was it so important?

You can answer the first question with a single sentence, probably. An example of a plausible answer would be: The most important day in Harry Potter’s life was the day he became a wizard.

If someone asks you why you think that, though, you’ll have to get into an explanation — and that could take pages. Every college paper you write will be asking you to explain, prove, or show why you think something is the answer to the question being asked. Therefore, we’ll often find “and why?” added on to the end of our questions.

2. Check Your Assignment Comprehension

Often, when assignments fail, it’s not because the student completing the assignment can’t do the work that’s been assigned; it’s because somewhere along the way, something was misunderstood. In other words, it’s more likely that missing the point of an assignment will earn an F than missing a comma, and yet we tend to spend much more time worrying about grammar and spelling than we do thinking about the original understanding we have of an assignment.

To complete college work, you’ve got to start with understanding it. This is a hurdle for some of us; when a handout seems clear, or an assignment seems intuitive, we usually dive right in. However, if you’ve ever received an assignment back with a grade that confused or frustrated you, you’ll know that it’s worth it to stop and think before you get started.

Therefore, read all assignment information at least twice. Take notes on it just as you would a textbook. If there’s no handout for the assignment, create one for yourself — a typed or handwritten page that explains the guidelines and expectations as you understand them.

Using Your Question

Creating a question from an assignment opens up a possibility for conversation with classmates and your instructor about what the assignment means. You may find that instructors are resistant to answering too many specific questions about assignments because they want to encourage student writers to think for themselves. However, nearly everyone is receptive to clarifying questions.

So, in our last assignment, we came up with the question:

A student can now take this question with them to class and ask their fellow students if they came up with a similar idea from the assignment. They could also check in with their instructor by saying, “What I understood from the assignment was that you’d like us to answer the question, ‘What were the major aims of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency? Did he fail or succeed?’”

This is also a place where a college or university writing center can come in handy. Getting an outside perspective this early can help catch minor twists or turns of language that we can sometimes miss if we’re in a hurry.

And, in case you hadn’t guessed already, this is also a big incentive for getting started on writing assignments well in advance. Most instructors will happily answer questions about an assignment a week before it’s due, but few will be so cheerful if you send a message four hours before the deadline.

3. Consider Your Audience

In any piece of writing audience must be a consideration. Most of us already do this automatically.

Consider the following scenario: You attended a Flaming Fish concert over the weekend. How would you tell the following audiences about your experience at the show?

- A best friend

- Other Flaming Fish fans in an internet forum

Let’s take this scenario further. Imagine you attended the concert not as a fan, but as a newspaper entertainment reporter. How would you tell your general readership about your experience at the show? What language would you use? How would it differ from the language you used with your parent, friend, or fellow fans?

When you think about the person or people who will be hearing/reading your story, you are considering your audience. Audience considerations apply when approaching any speaking or writing task — including college-level writing assignments.

Considering Audience: Primary and Secondary Audiences

This consideration of audience is vital in all writing. Consider the different language you use when writing a paper for a class versus when you send a text message to your friend, or the different way you might talk in the parking lot with a few classmates versus how you speak in front of your teachers.

Thinking about the audience can also make it easier to get started on an assignment. In any writing assignment that will be graded, your primary audience will be the instructor who reads the final product of the paper. “Primary,” here, means “most important.” However, most papers have secondary audiences, too, that will also need to be considered.

For instance, in a writing class, you may be asked to submit your papers to at least one round of peer review or peer workshop before turning them in for a final grade. That means your classmates will be a secondary audience.

How does that change your assignment? Well, for some of us, there are topics that we wouldn’t choose to discuss with our classmates (particularly at the beginning of a term when we don’t know each other well). In addition, you can also assume that your classmates will have certain knowledge in common with you (for instance, they’ll know about the campus and some general student information), but you can usually also assume they won’t know much about other topics (your personal life, for example). That means you’ll need to consider this as you write your paper.

Knows/Doesn’t Know

In our history class, you could assume that everyone in class has the same knowledge about Abraham Lincoln because you’ve all completed the same readings and heard the same lectures. You can also safely assume your instructor has completed those readings. This means you won’t need to start your paper with a one-page summary of who Abraham Lincoln was (unless you’re asked).

However, you probably don’t all have the same opinions about Lincoln, which means you’ll need to spend more time in your writing explaining why you think the way you do.

When thinking about your audience, you can make a “Knows/Doesn’t Know” chart to figure out what you’ll need to include and what you can skip. Create a row for each audience, and then create a column for what they know and don’t know. Write your question at the top of the paper as a reminder. Then list ideas, facts, and issues that you think your audience might know or might not know or agree with.

The Doesn’t Know column will be the place to work on for most of your writing.

Online Writing and Audiences

One final consideration for audience comes with the new territory of online classes and class interaction. Anymore, much of our writing starts or ends up online. It is important to remember that any writing done online has a third, potential audience: Anyone. Think how easy it is to accidentally forward an e-mail to someone else (or to reply-all when you mean to only write back to one person). It’s also very easy to copy and paste someone else’s text and send it elsewhere. Even “friends-only” communications on sites like Facebook can easily be copied and shared without the writer’s permission.

The same is true for text you write in college classes. When you participate in a forum, share work online, or send electronic correspondence, it’s possible (though not likely) that your work can be shared to a broader audience than you intended.

So, should we all walk around in a paranoid bubble? Should we go back to writing only on typewriters and hand-delivering our work to other people? Clearly not! But do remember that the things you write today may be accessible in 5 months or 5 years. Put in the effort to communicate clearly your true thoughts, and don’t put into writing anything you wouldn’t be comfortable having shared with others.

On this note, your class may ask you to write beyond your comfort zone in some topics from time to time. Please be gentle and respectful with classmates’ work, and do not share their stories beyond the safe space of your course. Expect them to do the same for you. Speak with your instructor if you have questions about the confidentiality of your work.

4. Consider Your Purpose

As we head into any piece of writing, we always have a purpose in mind. Most of us would say that our purpose in completing any assignment is along the lines of “getting this done,” “getting a good grade,” or maybe, in the best case, “learning more about the topic.” When we’re analyzing an assignment, we look at the purpose that the assignment’s creator had in mind. For instance, when you’re assigned to write a book report over a novel that the entire class has read, why are you assigned to write it? Is it because the teacher hasn’t read the book and wants to learn what happens? (Let’s hope not!) Or is there something that instructor wants you to learn from writing the report?

If we can figure out that purpose underneath our assignments, then we can better answer the questions being asked and meet the requirements. So, when faced with a writing assignment, ask yourself: What does the teacher want to learn from or about me in this assignment? What does she want to see that I can do?

In the Abraham Lincoln assignment we’ve been working with, what does the instructor most likely want to know about her students?

Common Purposes

There are several common purposes that exist for college (and all) types of writing. Some common purposes are:

- To Summarize

- To Persuade

- To Illustrate

- To Entertain

- To Compare or Contrast

- To Show Causes or Effects

- To Classify or Divide

- To Tell a Story

Writing composition talk classes talk about the ways that certain styles of writing can automatically fit with these purposes. That means that, once you’ve figured out the purpose of a piece, you may be able to quickly fit the writing to a pre-set outline or type of writing.

For instance, in our Abraham Lincoln example, I know I’ll be asked to explain and persuade. There are two essay formats that fit neatly to that purpose, so I could begin my outline almost immediately. Likewise, when I’m asked to tell a story, I’m almost always going to be using time order — so I can immediately begin organizing the way that I’ll work.

Adapted from Better Writing from the Beginning by Jenn Kepka, CC BY 4.0

From College to Career: A Handbook for Student Writers Copyright © by Jenn Kepka and Melissa Elston is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

TAILORING SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATIONS FOR AUDIENCE AND RESEARCH NARRATIVE

For success in research careers, scientists must be able to communicate their research questions, findings, and significance to both expert and nonexpert audiences. Scientists commonly disseminate their research using specialized communication products such as research articles, grant proposals, poster presentations, and scientific talks. The style and content of these communication products differ from language usage of the general public and can be difficult for nonexperts to follow and access. For this reason, it is important to tailor scientific communications to the intended audience to ensure that the communication product achieves its goals, especially when communicating with nonexpert audiences. This article presents a framework to increase access to research and science literacy. The protocol addresses aspects of communication that scientists should consider when producing a scientific communication product: audience, purpose, format, and significance (research narrative). The factors are essential for understanding the communication scenario and goals, which provide guidance when tailoring research communications to different audiences.

I. INTRODUCTION:

The impact of scientific research relies on the communication of discoveries among members of the research community. Sharing research—allowing other researchers to critique and build upon it—is a fundamental part of the scientific research process. Over time, however, scientific communications have become so specialized that they are primarily accessible only to experts in a given field. Scientists working in other fields and nonexperts alike can find typical scientific communication products (research articles, grant applications, poster presentations, and research talks) difficult to understand. To reach nonexpert audiences, scientists must be able to communicate in a variety of settings, media, and for a variety of different audiences.

This article provides an overview of the different audiences that scientists are likely to encounter in their careers and considerations for communicating with each of them. A general strategy or protocol is presented to tailor scientific communications according to three key factors of any communication scenario: the audience, the purpose, and the format. In addition to these factors, the sequence and selection of information is equally important for communicating the significance of the research. Concepts from narrative storytelling are also presented to help scientists identify and communicate the significance of research to the intended audience.

Evolution of Contemporary Scientific Discourse

Scientific vocabulary is rich in technical terms and jargon that is not commonly used by the general population. As recently as the nineteenth century, scientists used language and communication formats that would have been recognizable to educated nonexperts from a wide variety of fields and professions. Since that time, however, communication practices within scientific research fields have become different from the common language usage of the general public in both content and style. Scientific documents, such as research articles, grant proposals, and poster presentations, follow a logic that, while familiar to other scientists, can be difficult for nonexpert audiences to follow, properly access, and utilize. As a result, a communication gap has formed between the scientific community and the general public. In some cases, such as climate research and vaccine safety, this communication gap contributes to increased skepticism about scientific research findings and even mistrust of scientists and the scientific process.

The communication gap exists not only between scientists and the public, but also among scientists from different research fields. Investments in scientific research expanded greatly after World War II, resulting in increased numbers of individual scientists, subdisciplines, and specialized discourses used within each field. Today, scientific communications (specifically peer-reviewed research articles) have become specialized to the point that a “form that was as readable as the average newspaper has, in some fields, become a jungle of jargon that even those familiar with the territory struggle to understand” ( Knight, 2003 , p. 376). Because research articles and talks are the primary way that scientists disseminate their research, and because scientific research is increasingly interdisciplinary, this can create a barrier between researchers working in different scientific fields.

Communication Skills for Success in Science

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommend that Ph.D.-level scientists should be able to “communicate, both orally and in written form, the significance and impact of a study or body of work to all STEM professionals, other sectors that may utilize the results, and the public at large” ( Leshner & Scherer, 2018 , p. 107). To accomplish this, scientists must be able to move fluently between different audiences (STEM professionals, other sectors, and the public) and communication forms (written and oral), while highlighting the significance and impact of their research. For example, Dr. Neville Sanjana demonstrates how a discussion of CRISPR can be modified to tailor both technical language and level of detail to five different audiences: a 7 year-old, a 14 year-old, a college student, a grad student, and a CRISPR expert ( WIRED, 2017 ). The protocol presented in this article is a step-by-step guide for tailoring research significance to these audiences and can be used to create any scientific communication product.

II. Three Key Factors in Science Communication: Audience, Purpose, and Format

There are three key factors to consider when approaching a scientific communication scenario: the audience, the purpose, and the format of the communication product ( Alley, 1996 ,p. 3–7). The interaction between these three factors guides the communication strategy by focusing on who will receive it, why you are communicating, and how you will communicate (see Figure 1 ). Whether you are working in a primarily oral, written, or visual format, it is helpful to analyze the communication scenario as the first step in creating the communication product. Ask yourself three questions:

Analyzing the interaction of audience, purpose, and format of a scientific communication is the first step in tailoring scientific presentations and communications to different audiences.

- Who will receive the communication and in what setting? — This question will help you to create a profile of your audience.

- What is the purpose of the communication and what do you want it to accomplish? — This question helps to establish the goal of your communication product.

- Will the communication product be oral, written, visual (or some combination) and what constraints does this format impose? — This question helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of your format.

Carefully analyze these factors prior to composing and deliving your scientific communication product. Taking time to understand the communication scenario at the outset allows you to create a framework to guide each decision that must be made along the way. Use this protocol throughout the composition and revision process to ensure that you are tailoring your scientific communication correctly. Each factor is examined in more detail below and a checklist is provided at the end of the article.

Consider Audience

The audience is the most important factor to consider when tailoring scientific communications. The audience’s response to your communication is the metric determining whether the communication meets its goal. For example, if you aim to instruct a motivated group of high school students but they cannot follow the presentation you have prepared, then your communication product will not have achieved its goal. For this reason, it is important to keep the audience in mind while composing your communication and to view the communication product through their eyes and ears to the extent possible. This helps you focus on the reception of the communication and align it with your intentions.

Creating a profile of your audience will help to guide the choices you will make while creating the communication product. To do this, imagine the people you want to communicate with and answer the questions below.

- Who will receive this communication?

- How and where will they receive the communication?

- What do they know about the subject?

- Why are they motivated to receive the communication?

If you are unsure how to answer any of these questions, then you will need to do more research on your audience. This can include talking to individuals who represent your intended audience, reading or watching the media this audience frequently encounters, or talking to colleagues who are familiar with the audience. Speaking directly to members of the audience is the preferred method, because it allows you to get feedback on draft communications and tailor them to your target audience in real time.

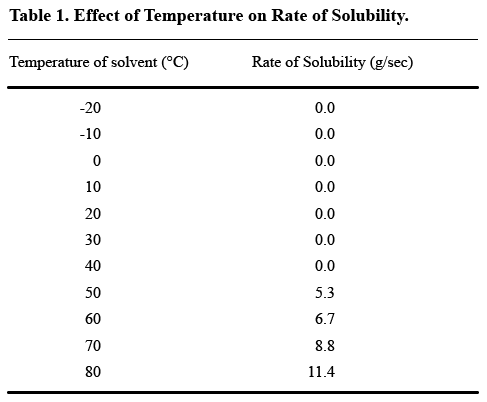

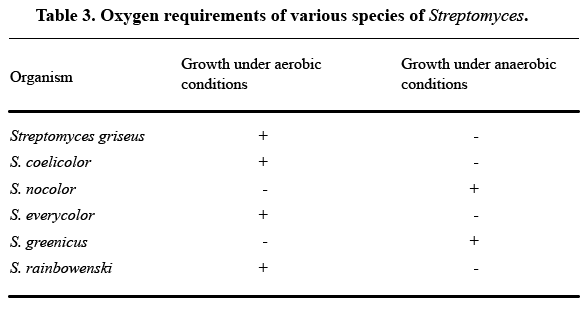

Each audience has distinct interests and motivations for receiving scientific communications. These can be influenced by audience characteristics such as primary language, demographics, interest in science, etc. Understanding the level of scientific expertise of the audience is one of the most important characteristics to consider. Are they experts in your scientific field, experts in another scientific field, or nonexperts? Audiences may also be a combination of experts and nonexperts. Table 1 categorizes some common audiences of scientific communications according to levels of expertise: researchers, publishers, funders, conference organizers, students, policy-makers, journalists, and business people. Understanding their level of expertise in the field is a first step toward tailoring the communication for the intended audience or audiences.

Example Audiences Categorized by Level of Scientific Expertise

Tailoring scientific communications to expert or nonexpert audiences requires a variety of adjustments to content and style. Choosing the correct level of detail and method for presenting data are both important considerations. Expert audiences will expect the greatest level of detail and most comprehensive presentation of data in order to critique the research and understand its implications for the field. Nonexpert audiences may respond better to a simplified version of the research that focuses clearly on significance and impact but sacrifices some detail. At the level of vocabulary, it is important to choose words that are familiar to the audience. An audience of expert scientists will benefit from the use of technical terms and jargon, which function as short-hand within the field; these same words will alienate the general public and may be unfamiliar to scientist from other disciplines. Tailoring the content and language to the needs and interests of your audience ensures that you do not talk over the heads of lay people or talk down to experts; both will interfere with audience engagement and your communication aim.

Consider Purpose

The second factor to consider when tailoring your scientific communication is your purpose or goal for communicating with the audience. Scientists use communication products to achieve a variety of aims. They instruct individuals and groups that want to learn about their research. They inform peers, policy-makers, and journalists of their discoveries. They critique the research of peers and indicate new research that is needed to advance the field. They persuade grant reviewers and editors to fund and publish their work, respectively. They persuade patent agents and business people that their discoveries have commercial potential. They may persuade and recruit members of the general population to engage with their research or even enter scientific training and careers. To identify the purpose of your scientific communication product, answer the questions below.

- Why are you creating this scientific communication?

- What challenge or problem does this communication respond to?

- What do you want the scientific communication product to accomplish?

By responding to these questions, you articulate your own motivations for the scientific communication and the outcome you hope to achieve. In other words, you identify the need for the communication and your metrics for success.

Consider Format

The third factor to consider when tailoring scientific communications to different audiences is the format, medium, or genre of the communication product. Select a format that fits your communication needs while allowing the audience to engage optimally with the scientific content you want to present. Table 2 summarizes common scientific communication genres and formats. When selecting a format, consider the types of communications and media that your audience is likely to encounter in a normal day. Think about what your audience reads (academic journals and posters, newspapers, magazines, and social media), watches (television, videos, and films), and listens to (radio, music, and podcasts). Whether you are writing, speaking, creating a video, or engaging in another form of communication, the format imposes constraints on the communication scenario and informs the style and content.

Common Science Communication Genres and Formats

If you have flexibility in your format, answer these questions to help identify the best medium or genre for your communication product:

- What is the best format, medium, or genre to reach the intended audience?

- Which communication format am I best prepared to work in?

Written, oral, and visual formats each have inherent strengths and weaknesses. For example, a live talk can maximize interactions with the audience, allowing the speaker to establish rapport, check for comprehension, and respond to questions. The audience also has the opportunity to incorporate visual information such as the speaker’s body language and slides or other visual aids. A pre-recorded video presentation provides the benefits of the visual and oral formats, like the live talk, but would not facilitate audience interactions. The live talk relies on consistent attention from audience members to follow the flow of information; those who become distracted are likely to miss information and may have difficulty re-engaging with the presentation. Choose the best format for your audience and purpose, then keep strengths and weaknesses in mind while creating the communication product.

Once the format has been selected, answer these questions to identify how the format will affect the content and style:

- What constraints does the format impose?

- Is the format primarily written, oral, visual, or a combination of these?

Audiences expect communication products to adhere to common characteristics of the genre or format. Newspaper readers will look for headlines to orient themselves and select articles to engage with. Podcast listeners will identify the beginnings and endings of episodes in response to familiar theme music or other regular audio features. Scientists expect journal articles to present information in a particular sequence (abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, and references). While the common features of the genre and readers’ expectations place constraints on the scientific communication product, they also help audiences quickly orient themselves to the format and more deeply engage with the scientific content. Understand the constraints of the format and work within them to create a communication product that responds to the needs of your audience while achieving your communication goals.

III. Significance: Telling the Story of Your Research

Significance refers to the difference that your research makes in the world. To have significance or impact, research must change the current state of the field by answering a question, solving a problem, or filling a gap in existing knowledge. When you communicate the significance of your research, you tell the story of the impact it can have on the world. A story, in its most basic and fundamental form, describes a scenario that changes in some important way over a period of time: “The story always involves temporal sequences … [and] at least one modification of a state of affairs” ( Prince, 2003 , p. 59). These defining aspects of time and transformation are what distinguish stories from other modes of communication and align well with the goals and process of scientific inquiry. Scientific research seeks to observe changes within experimental contexts in the interest of discovering new knowledge and solving problems. The change observed, as well as its implications and applications, point to the significance and impact of the research. Therefore, to identify the significance of your research, find the story.

Storytelling for Scientists

It is worth stating explicitly that scientific stories are not fiction. Rather, the story emerges from the interpretation of novel data produced through rigorous experimental design. Environmental scientist Dr. Joshua Schimel explains that “[t]o tell a good story in science, you must assess your data and evaluate the possible explanations—which are most consistent with existing knowledge and theory? The story grows organically from the data and is objective, dispassionate, and fully professional” ( Schimel, 2012 , p. 9). Science stories are driven by the question or research problem addressed. The story emerges from the relationship between the research question and the novel data.

The temporal characteristic is equally important. When it comes to communicating the story of your research, there are two different sequences at work. The sequence of experiments that you perform and observations that you make contribute to the lab notebook information sequence (see Figure 2 ). This sequence catalogs the details of the scientific discovery, however, this linear documentation of time, effort, and resources does not communicate the significance and story of the research in a compelling way. To highlight the research story, it is necessary to construct another sequence, the research story information sequence (see Figure 3 ), which highlights significance by connecting novel experimental data to the question or problem that motivates the research. A compelling research narrative necessarily skips over some details, like failed experiments, in order to concretely illustrate the connection between question and novel data.

A detailed lab notebook is essential for future research reproducibility; however, this sequence of information does not tell a very interesting story for either experts or nonexperts.

A research story selects and sequences information to highlight the significance of the research: how new knowledge emerges from the relationship between the question asked and novel data.

Significance and Audience

We have seen how tailoring science communications to a variety of audiences can affect the content and style of the communication product. Different audiences require appropriate language and level of detail. Likewise, scientific communication products should highlight the significance and impact of the research as seen through the lens of the intended audience. Like the content and style of any scientific communication, the message of research significance should be tailored to the interests and perspective of the audience. For example, the discovery of a new molecular structure or pathway may be significant within a narrow research field, but it will likely need to be placed within broader context and implications for human health or medicine to seem important to the general public.

IV. Checklist for Tailoring Scientific Communications to a Variety of Audiences

Use this checklist to tailor your scientific communications to different audiences. Steps 1–4 provide guidelines to prepare and organize your communication product. Step 5 is intended to aid with getting feedback on your communication product for revision.

- Why am I creating this scientific communication?

- What do I want the scientific communication product to accomplish?

- What is the significance of the research for this audience?

- What is the research story information sequence?

- Is the language and level of detail right for the audience?

- Does the format meet the communication goals?

- Does the communication product highlight the significance of the research?

V. CONCLUSION:

Effective scientific communication requires careful analysis of the communication scenario and ability to highlight the research significance in narrative form. The protocol presented here is a starting point to develop a scientific communication practice for both expert and nonexpert audiences. These strategies may help increase access to scientific research among a wide range of populations—expert and nonexpert alike. By analyzing the audience, purpose, and format of your communications, you prepare to tailor scientific communications to the target audience and scenario. By highlighting the research narrative, you emphasize the potential impact that the research can make in the world. This framework provides a structure for self-analysis and revision for any scientific communication scenario, and accounts for variations in style, content, and narrative that are necessary to tailor scientific communications to any audience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

I would like to thank all of my science communication students at Washington University in St. Louis; your questions and feedback motivated me to connect narrative theory concepts to science communication instruction. Portions of this work were supported by NIH grant #3T32GM008151-34S1.

LITERATURE CITED:

- Alley M. (1996). The craft of scientific writing (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Knight J. (2003). Scientific Literacy: Clear as Mud . Nature 423 , 376–378. 10.1038/423376a. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leshner A, & Scherer L. (Eds.). (2018). Graduate STEM Education for the 21 st Century . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25038. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prince G. (2003). Dictionary of Narratology . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schimel J. (2012). Writing Science: How to write papers that get cited and proposals that get funded . New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- WIRED. (2017). Biologist explains one concept in 5 levels of difficulty-CRISPR . WIRED . Retrieved from https://youtu.be/sweN8d4_MUg

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Identifying Audiences

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The concept of audience can be very confusing for novice researchers. Should the student's audience be her instructor only, or should her paper attempt to reach a larger academic crowd? These are two extremes on the pendulum-course that is audience; the former is too narrow of an audience, while the latter is too broad. Therefore, it is important for the student to articulate an audience that falls somewhere in between.

It is perhaps helpful to approach the audience of a research paper in the same way one would when preparing for an oral presentation. Often, one changes her style, tone, diction, etc., when presenting to different audiences. It is the same when writing a research paper. In fact, you may need to transform your written work into an oral work if you find yourself presenting at a conference someday.

The instructor should be considered only one member of the paper's audience; he is part of the academic audience that desires students to investigate, research, and evaluate a topic. Try to imagine an audience that would be interested in and benefit from your research.

For example: if the student is writing a twelve-page research paper about ethanol and its importance as an energy source of the future, would she write with an audience of elementary students in mind? This would be unlikely. Instead, she would tailor her writing to be accessible to an audience of fellow engineers and perhaps to the scientific community in general. What is more, she would assume the audience to be at a certain educational level; therefore, she would not spend time in such a short research paper defining terms and concepts already familiar to those in the field. However, she should also avoid the type of esoteric discussion that condescends to her audience. Again, the student must articulate a middle-ground.

The following are questions that may help the student discern further her audience:

- Who is the general audience I want to reach?

- Who is most likely to be interested in the research I am doing?

- What is it about my topic that interests the general audience I have discerned?

- If the audience I am writing for is not particularly interested in my topic, what should I do to pique its interest?

- Will each member of the broadly conceived audience agree with what I have to say?

- If not (which will likely be the case!) what counter-arguments should I be prepared to answer?

Remember, one of the purposes of a research paper is to add something new to the academic community, and the first-time researcher should understand her role as an initiate into a particular community of scholars. As the student increases her involvement in the field, her understanding of her audience will grow as well. Once again, practice lies at the heart of the thing.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content

Learning objectives.

- Identify the four common academic purposes.

- Identify audience, tone, and content.

- Apply purpose, audience, tone, and content to a specific assignment.

Imagine reading one long block of text, with each idea blurring into the next. Even if you are reading a thrilling novel or an interesting news article, you will likely lose interest in what the author has to say very quickly. During the writing process, it is helpful to position yourself as a reader. Ask yourself whether you can focus easily on each point you make. One technique that effective writers use is to begin a fresh paragraph for each new idea they introduce.

Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks. One paragraph focuses on only one main idea and presents coherent sentences to support that one point. Because all the sentences in one paragraph support the same point, a paragraph may stand on its own. To create longer assignments and to discuss more than one point, writers group together paragraphs.

Three elements shape the content of each paragraph:

- Purpose . The reason the writer composes the paragraph.

- Tone . The attitude the writer conveys about the paragraph’s subject.

- Audience . The individual or group whom the writer intends to address.

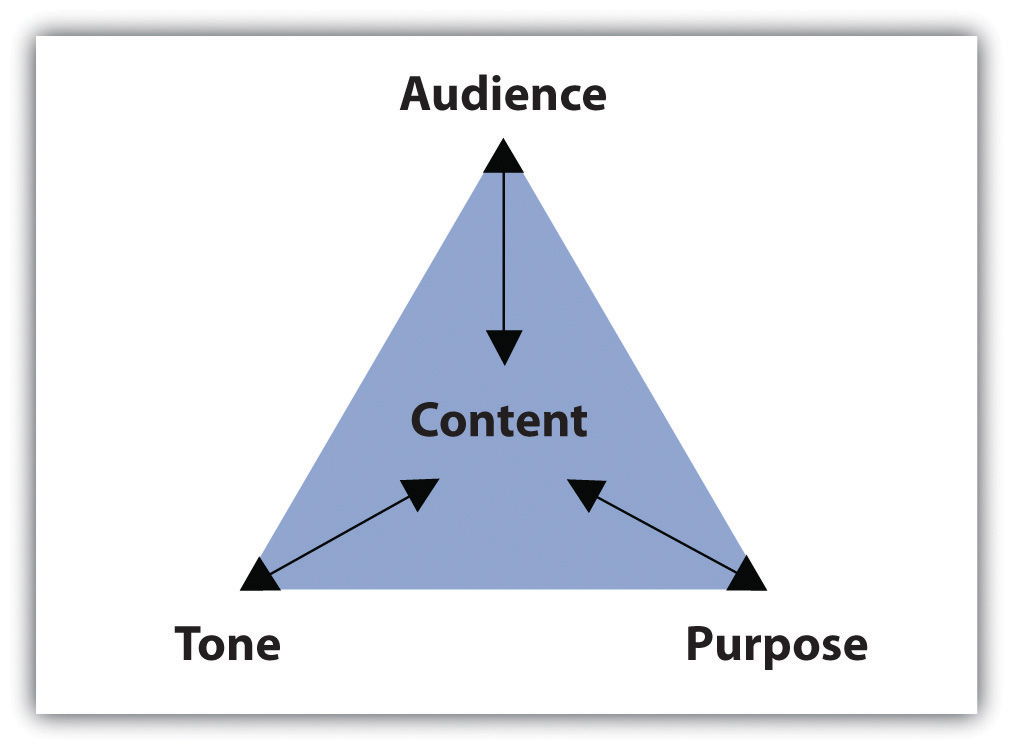

Figure 6.1 Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content Triangle

The assignment’s purpose, audience, and tone dictate what the paragraph covers and how it will support one main point. This section covers how purpose, audience, and tone affect reading and writing paragraphs.

Identifying Common Academic Purposes

The purpose for a piece of writing identifies the reason you write a particular document. Basically, the purpose of a piece of writing answers the question “Why?” For example, why write a play? To entertain a packed theater. Why write instructions to the babysitter? To inform him or her of your schedule and rules. Why write a letter to your congressman? To persuade him to address your community’s needs.

In academic settings, the reasons for writing fulfill four main purposes: to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate. You will encounter these four purposes not only as you read for your classes but also as you read for work or pleasure. Because reading and writing work together, your writing skills will improve as you read. To learn more about reading in the writing process, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Eventually, your instructors will ask you to complete assignments specifically designed to meet one of the four purposes. As you will see, the purpose for writing will guide you through each part of the paper, helping you make decisions about content and style. For now, identifying these purposes by reading paragraphs will prepare you to write individual paragraphs and to build longer assignments.

Summary Paragraphs

A summary shrinks a large amount of information into only the essentials. You probably summarize events, books, and movies daily. Think about the last blockbuster movie you saw or the last novel you read. Chances are, at some point in a casual conversation with a friend, coworker, or classmate, you compressed all the action in a two-hour film or in a two-hundred-page book into a brief description of the major plot movements. While in conversation, you probably described the major highlights, or the main points in just a few sentences, using your own vocabulary and manner of speaking.

Similarly, a summary paragraph condenses a long piece of writing into a smaller paragraph by extracting only the vital information. A summary uses only the writer’s own words. Like the summary’s purpose in daily conversation, the purpose of an academic summary paragraph is to maintain all the essential information from a longer document. Although shorter than the original piece of writing, a summary should still communicate all the key points and key support. In other words, summary paragraphs should be succinct and to the point.

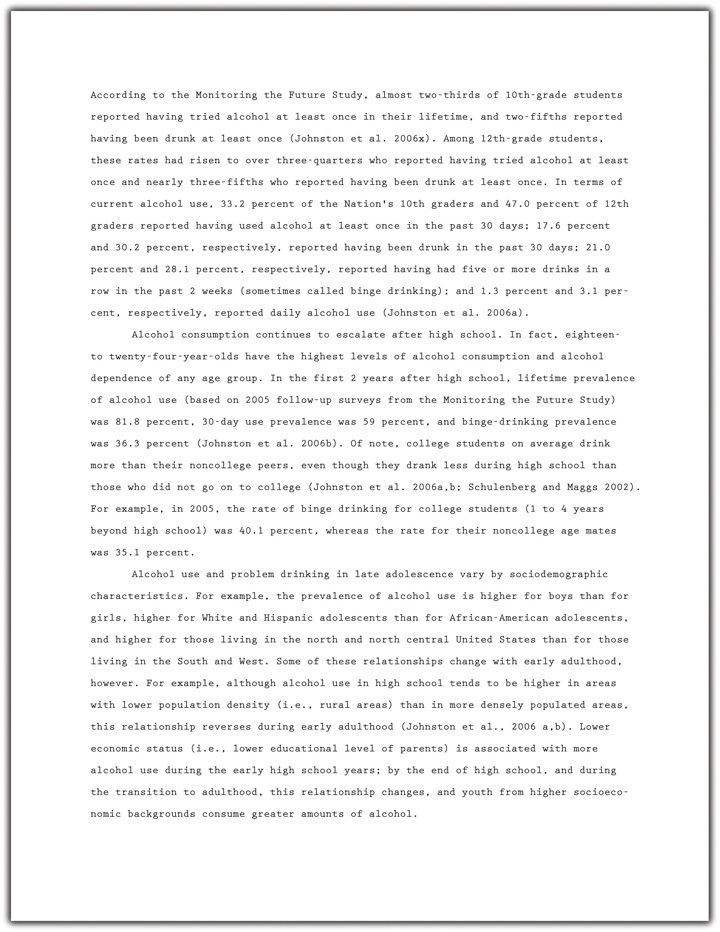

A summary of the report should present all the main points and supporting details in brief. Read the following summary of the report written by a student:

Notice how the summary retains the key points made by the writers of the original report but omits most of the statistical data. Summaries need not contain all the specific facts and figures in the original document; they provide only an overview of the essential information.

Analysis Paragraphs

An analysis separates complex materials in their different parts and studies how the parts relate to one another. The analysis of simple table salt, for example, would require a deconstruction of its parts—the elements sodium (Na) and chloride (Cl). Then, scientists would study how the two elements interact to create the compound NaCl, or sodium chloride, which is also called simple table salt.

Analysis is not limited to the sciences, of course. An analysis paragraph in academic writing fulfills the same purpose. Instead of deconstructing compounds, academic analysis paragraphs typically deconstruct documents. An analysis takes apart a primary source (an essay, a book, an article, etc.) point by point. It communicates the main points of the document by examining individual points and identifying how the points relate to one another.

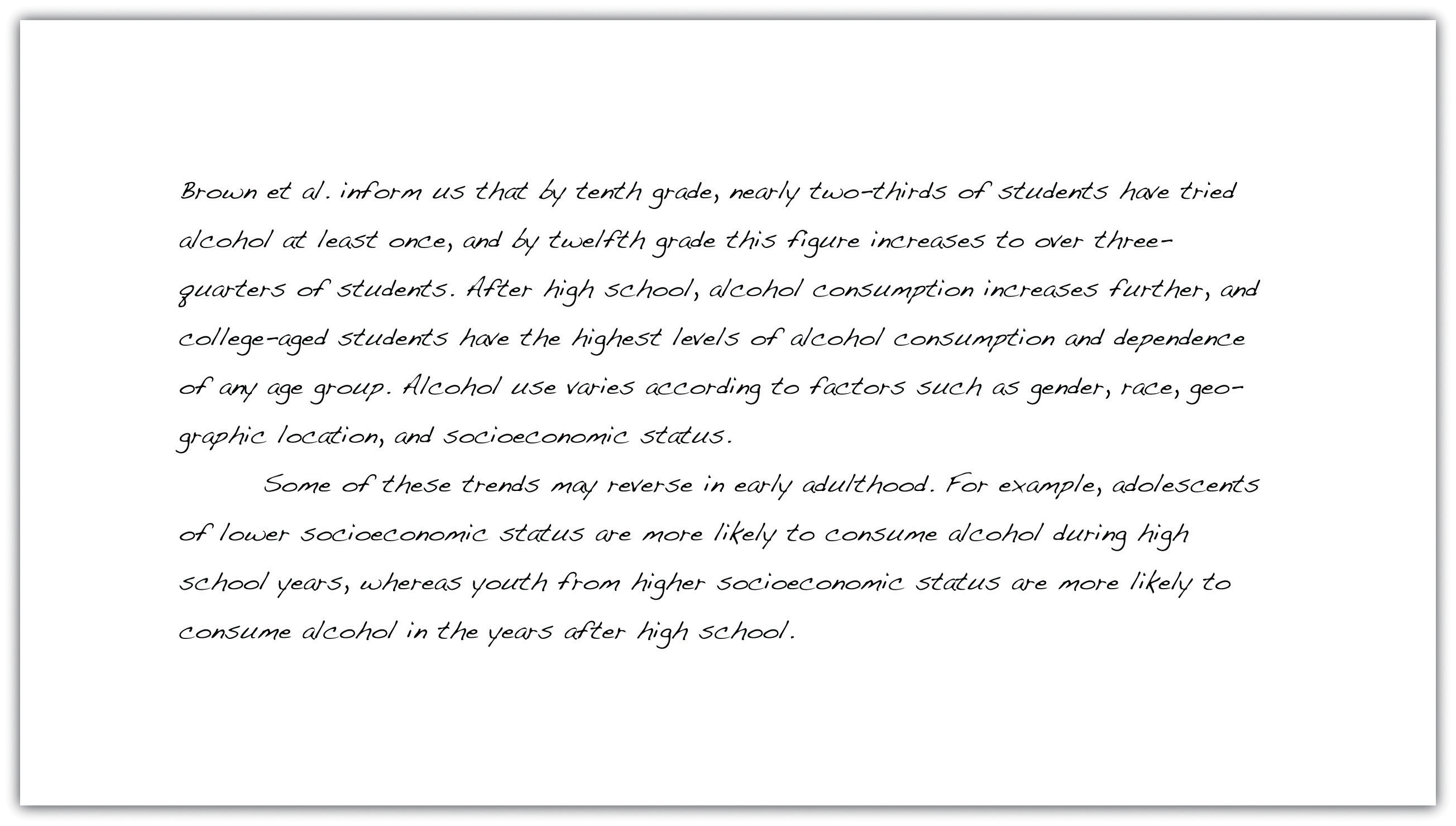

Take a look at a student’s analysis of the journal report.

Notice how the analysis does not simply repeat information from the original report, but considers how the points within the report relate to one another. By doing this, the student uncovers a discrepancy between the points that are backed up by statistics and those that require additional information. Analyzing a document involves a close examination of each of the individual parts and how they work together.

Synthesis Paragraphs

A synthesis combines two or more items to create an entirely new item. Consider the electronic musical instrument aptly named the synthesizer. It looks like a simple keyboard but displays a dashboard of switches, buttons, and levers. With the flip of a few switches, a musician may combine the distinct sounds of a piano, a flute, or a guitar—or any other combination of instruments—to create a new sound. The purpose of the synthesizer is to blend together the notes from individual instruments to form new, unique notes.

The purpose of an academic synthesis is to blend individual documents into a new document. An academic synthesis paragraph considers the main points from one or more pieces of writing and links the main points together to create a new point, one not replicated in either document.

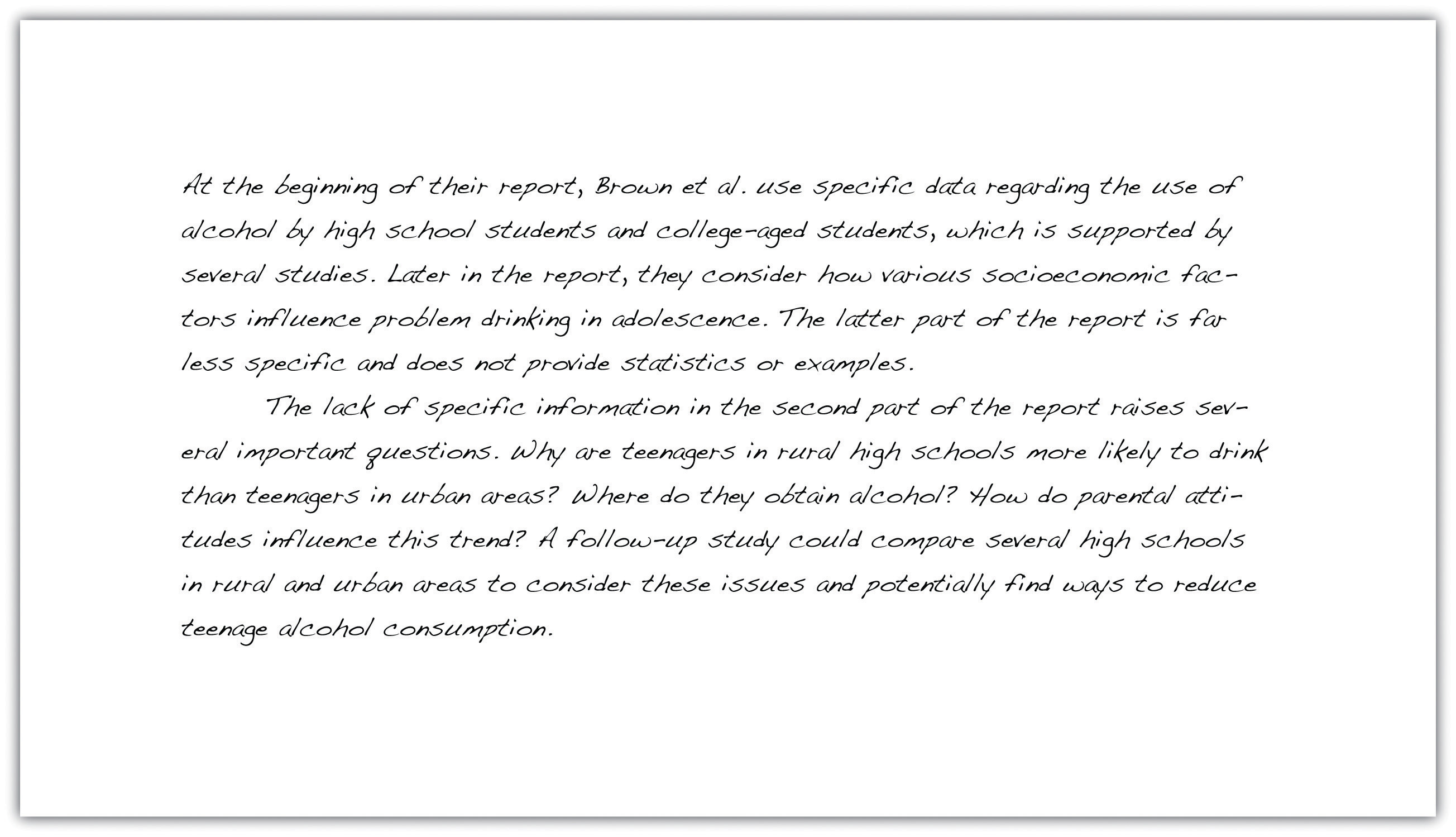

Take a look at a student’s synthesis of several sources about underage drinking.

Notice how the synthesis paragraphs consider each source and use information from each to create a new thesis. A good synthesis does not repeat information; the writer uses a variety of sources to create a new idea.

Evaluation Paragraphs

An evaluation judges the value of something and determines its worth. Evaluations in everyday experiences are often not only dictated by set standards but also influenced by opinion and prior knowledge. For example, at work, a supervisor may complete an employee evaluation by judging his subordinate’s performance based on the company’s goals. If the company focuses on improving communication, the supervisor will rate the employee’s customer service according to a standard scale. However, the evaluation still depends on the supervisor’s opinion and prior experience with the employee. The purpose of the evaluation is to determine how well the employee performs at his or her job.

An academic evaluation communicates your opinion, and its justifications, about a document or a topic of discussion. Evaluations are influenced by your reading of the document, your prior knowledge, and your prior experience with the topic or issue. Because an evaluation incorporates your point of view and reasons for your point of view, it typically requires more critical thinking and a combination of summary, analysis, and synthesis skills. Thus evaluation paragraphs often follow summary, analysis, and synthesis paragraphs. Read a student’s evaluation paragraph.

Notice how the paragraph incorporates the student’s personal judgment within the evaluation. Evaluating a document requires prior knowledge that is often based on additional research.

When reviewing directions for assignments, look for the verbs summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate . Instructors often use these words to clearly indicate the assignment’s purpose. These words will cue you on how to complete the assignment because you will know its exact purpose.

Read the following paragraphs about four films and then identify the purpose of each paragraph.

- This film could easily have been cut down to less than two hours. By the final scene, I noticed that most of my fellow moviegoers were snoozing in their seats and were barely paying attention to what was happening on screen. Although the director sticks diligently to the book, he tries too hard to cram in all the action, which is just too ambitious for such a detail-oriented story. If you want my advice, read the book and give the movie a miss.

- During the opening scene, we learn that the character Laura is adopted and that she has spent the past three years desperately trying to track down her real parents. Having exhausted all the usual options—adoption agencies, online searches, family trees, and so on—she is on the verge of giving up when she meets a stranger on a bus. The chance encounter leads to a complicated chain of events that ultimately result in Laura getting her lifelong wish. But is it really what she wants? Throughout the rest of the film, Laura discovers that sometimes the past is best left where it belongs.

- To create the feeling of being gripped in a vice, the director, May Lee, uses a variety of elements to gradually increase the tension. The creepy, haunting melody that subtly enhances the earlier scenes becomes ever more insistent, rising to a disturbing crescendo toward the end of the movie. The desperation of the actors, combined with the claustrophobic atmosphere and tight camera angles create a realistic firestorm, from which there is little hope of escape. Walking out of the theater at the end feels like staggering out of a Roman dungeon.

- The scene in which Campbell and his fellow prisoners assist the guards in shutting down the riot immediately strikes the viewer as unrealistic. Based on the recent reports on prison riots in both Detroit and California, it seems highly unlikely that a posse of hardened criminals will intentionally help their captors at the risk of inciting future revenge from other inmates. Instead, both news reports and psychological studies indicate that prisoners who do not actively participate in a riot will go back to their cells and avoid conflict altogether. Examples of this lack of attention to detail occur throughout the film, making it almost unbearable to watch.

Collaboration

Share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Writing at Work

Thinking about the purpose of writing a report in the workplace can help focus and structure the document. A summary should provide colleagues with a factual overview of your findings without going into too much specific detail. In contrast, an evaluation should include your personal opinion, along with supporting evidence, research, or examples to back it up. Listen for words such as summarize , analyze , synthesize , or evaluate when your boss asks you to complete a report to help determine a purpose for writing.

Consider the essay most recently assigned to you. Identify the most effective academic purpose for the assignment.

My assignment: ____________________________________________

My purpose: ____________________________________________

Identifying the Audience

Imagine you must give a presentation to a group of executives in an office. Weeks before the big day, you spend time creating and rehearsing the presentation. You must make important, careful decisions not only about the content but also about your delivery. Will the presentation require technology to project figures and charts? Should the presentation define important words, or will the executives already know the terms? Should you wear your suit and dress shirt? The answers to these questions will help you develop an appropriate relationship with your audience, making them more receptive to your message.

Now imagine you must explain the same business concepts from your presentation to a group of high school students. Those important questions you previously answered may now require different answers. The figures and charts may be too sophisticated, and the terms will certainly require definitions. You may even reconsider your outfit and sport a more casual look. Because the audience has shifted, your presentation and delivery will shift as well to create a new relationship with the new audience.

In these two situations, the audience—the individuals who will watch and listen to the presentation—plays a role in the development of presentation. As you prepare the presentation, you visualize the audience to anticipate their expectations and reactions. What you imagine affects the information you choose to present and how you will present it. Then, during the presentation, you meet the audience in person and discover immediately how well you perform.

Although the audience for writing assignments—your readers—may not appear in person, they play an equally vital role. Even in everyday writing activities, you identify your readers’ characteristics, interests, and expectations before making decisions about what you write. In fact, thinking about audience has become so common that you may not even detect the audience-driven decisions.

For example, you update your status on a social networking site with the awareness of who will digitally follow the post. If you want to brag about a good grade, you may write the post to please family members. If you want to describe a funny moment, you may write with your friends’ senses of humor in mind. Even at work, you send e-mails with an awareness of an unintended receiver who could intercept the message.

In other words, being aware of “invisible” readers is a skill you most likely already possess and one you rely on every day. Consider the following paragraphs. Which one would the author send to her parents? Which one would she send to her best friend?

Last Saturday, I volunteered at a local hospital. The visit was fun and rewarding. I even learned how to do cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. Unfortunately, I think caught a cold from one of the patients. This week, I will rest in bed and drink plenty of clear fluids. I hope I am well by next Saturday to volunteer again.

OMG! You won’t believe this! My advisor forced me to do my community service hours at this hospital all weekend! We learned CPR but we did it on dummies, not even real peeps. And some kid sneezed on me and got me sick! I was so bored and sniffling all weekend; I hope I don’t have to go back next week. I def do NOT want to miss the basketball tournament!

Most likely, you matched each paragraph to its intended audience with little hesitation. Because each paragraph reveals the author’s relationship with her intended readers, you can identify the audience fairly quickly. When writing your own paragraphs, you must engage with your audience to build an appropriate relationship given your subject. Imagining your readers during each stage of the writing process will help you make decisions about your writing. Ultimately, the people you visualize will affect what and how you write.

While giving a speech, you may articulate an inspiring or critical message, but if you left your hair a mess and laced up mismatched shoes, your audience would not take you seriously. They may be too distracted by your appearance to listen to your words.

Similarly, grammar and sentence structure serve as the appearance of a piece of writing. Polishing your work using correct grammar will impress your readers and allow them to focus on what you have to say.

Because focusing on audience will enhance your writing, your process, and your finished product, you must consider the specific traits of your audience members. Use your imagination to anticipate the readers’ demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations.

- Demographics. These measure important data about a group of people, such as their age range, their ethnicity, their religious beliefs, or their gender. Certain topics and assignments will require these kinds of considerations about your audience. For other topics and assignments, these measurements may not influence your writing in the end. Regardless, it is important to consider demographics when you begin to think about your purpose for writing.

- Education. Education considers the audience’s level of schooling. If audience members have earned a doctorate degree, for example, you may need to elevate your style and use more formal language. Or, if audience members are still in college, you could write in a more relaxed style. An audience member’s major or emphasis may also dictate your writing.

- Prior knowledge. This refers to what the audience already knows about your topic. If your readers have studied certain topics, they may already know some terms and concepts related to the topic. You may decide whether to define terms and explain concepts based on your audience’s prior knowledge. Although you cannot peer inside the brains of your readers to discover their knowledge, you can make reasonable assumptions. For instance, a nursing major would presumably know more about health-related topics than a business major would.

- Expectations. These indicate what readers will look for while reading your assignment. Readers may expect consistencies in the assignment’s appearance, such as correct grammar and traditional formatting like double-spaced lines and legible font. Readers may also have content-based expectations given the assignment’s purpose and organization. In an essay titled “The Economics of Enlightenment: The Effects of Rising Tuition,” for example, audience members may expect to read about the economic repercussions of college tuition costs.

On your own sheet of paper, generate a list of characteristics under each category for each audience. This list will help you later when you read about tone and content.

1. Your classmates

- Demographics ____________________________________________

- Education ____________________________________________

- Prior knowledge ____________________________________________

- Expectations ____________________________________________

2. Your instructor

3. The head of your academic department

4. Now think about your next writing assignment. Identify the purpose (you may use the same purpose listed in Note 6.12 “Exercise 2” ), and then identify the audience. Create a list of characteristics under each category.

My audience: ____________________________________________

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

Keep in mind that as your topic shifts in the writing process, your audience may also shift. For more information about the writing process, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Also, remember that decisions about style depend on audience, purpose, and content. Identifying your audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how you write, but purpose and content play an equally important role. The next subsection covers how to select an appropriate tone to match the audience and purpose.

Selecting an Appropriate Tone

Tone identifies a speaker’s attitude toward a subject or another person. You may pick up a person’s tone of voice fairly easily in conversation. A friend who tells you about her weekend may speak excitedly about a fun skiing trip. An instructor who means business may speak in a low, slow voice to emphasize her serious mood. Or, a coworker who needs to let off some steam after a long meeting may crack a sarcastic joke.

Just as speakers transmit emotion through voice, writers can transmit through writing a range of attitudes, from excited and humorous to somber and critical. These emotions create connections among the audience, the author, and the subject, ultimately building a relationship between the audience and the text. To stimulate these connections, writers intimate their attitudes and feelings with useful devices, such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language. Keep in mind that the writer’s attitude should always appropriately match the audience and the purpose.

Read the following paragraph and consider the writer’s tone. How would you describe the writer’s attitude toward wildlife conservation?

Many species of plants and animals are disappearing right before our eyes. If we don’t act fast, it might be too late to save them. Human activities, including pollution, deforestation, hunting, and overpopulation, are devastating the natural environment. Without our help, many species will not survive long enough for our children to see them in the wild. Take the tiger, for example. Today, tigers occupy just 7 percent of their historical range, and many local populations are already extinct. Hunted for their beautiful pelt and other body parts, the tiger population has plummeted from one hundred thousand in 1920 to just a few thousand. Contact your local wildlife conservation society today to find out how you can stop this terrible destruction.

Think about the assignment and purpose you selected in Note 6.12 “Exercise 2” , and the audience you selected in Note 6.16 “Exercise 3” . Now, identify the tone you would use in the assignment.

My tone: ____________________________________________

Choosing Appropriate, Interesting Content

Content refers to all the written substance in a document. After selecting an audience and a purpose, you must choose what information will make it to the page. Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations, but no matter the type, the information must be appropriate and interesting for the audience and purpose. An essay written for third graders that summarizes the legislative process, for example, would have to contain succinct and simple content.

Content is also shaped by tone. When the tone matches the content, the audience will be more engaged, and you will build a stronger relationship with your readers. Consider that audience of third graders. You would choose simple content that the audience will easily understand, and you would express that content through an enthusiastic tone. The same considerations apply to all audiences and purposes.

Match the content in the box to the appropriate audience and purpose. On your own sheet of paper, write the correct letter next to the number.

- Whereas economist Holmes contends that the financial crisis is far from over, the presidential advisor Jones points out that it is vital to catch the first wave of opportunity to increase market share. We can use elements of both experts’ visions. Let me explain how.

- In 2000, foreign money flowed into the United States, contributing to easy credit conditions. People bought larger houses than they could afford, eventually defaulting on their loans as interest rates rose.

- The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, known by most of us as the humungous government bailout, caused mixed reactions. Although supported by many political leaders, the statute provoked outrage among grassroots groups. In their opinion, the government was actually rewarding banks for their appalling behavior.

Audience: An instructor

Purpose: To analyze the reasons behind the 2007 financial crisis

Content: ____________________________________________

Audience: Classmates

Purpose: To summarize the effects of the $700 billion government bailout

Audience: An employer

Purpose: To synthesize two articles on preparing businesses for economic recovery

Using the assignment, purpose, audience, and tone from Note 6.18 “Exercise 4” , generate a list of content ideas. Remember that content consists of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations.

My content ideas: ____________________________________________

Key Takeaways

- Paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks of information.

- The content of each paragraph and document is shaped by purpose, audience, and tone.

- The four common academic purposes are to summarize, to analyze, to synthesize, and to evaluate.

- Identifying the audience’s demographics, education, prior knowledge, and expectations will affect how and what you write.

- Devices such as sentence structure, word choice, punctuation, and formal or informal language communicate tone and create a relationship between the writer and his or her audience.

- Content may consist of examples, statistics, facts, anecdotes, testimonies, and observations. All content must be appropriate and interesting for the audience, purpose and tone.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Utility Menu

de5f0c5840276572324fc6e2ece1a882

- How to Use This Site

- Core Competencies

- Consider Your Audience

The importance of forming a mutual exchange between you and your audience.

Why is considering your audience important?

- Your audience informs how you convey your message.

- Your talk can cater to a variety of audiences.

- Your talk is framed by intentional decisions you make to form a mutual exchange.

How can you consider your audience?

Assess | reflection.

There is no way to truly 'know' your audience. However, it is possible to reflect on how you can tailor your talk to consider them.

Check assumptions and reframe them as considerations. How might your assumptions manifest in your talk? What questions are your assumptions getting at?

What does this look like in practice?

- "I assume that my audience consists of only clinicians, so all of my examples are clinican focused."

Instead, try:

- "I recognize that my audience may consist of clinicians, but that does not mean that it is the only dicipline in my audience. How can I use examples that capture this variety?"

Establishing trust early and often is critical. How can you begin to build trust? You can build trust by being:

- For example, discuss what questions persist and acknowledge that you don't know everything.

- For example, consider areas of concern or skepticism and address them where you can. Incorporating interactive elements during the talk to engage audience members.

- For example, make decisions in your talk that show you recognize your audience is not a monolith.

In the video below, Dr. Junaid Nabi asks Jessica Malaty Rivera, MS how people can establish trust when communicating science. Jessica talks about trust as a social determinant of health. Trust or lack of trust has real-world impacts on how people make informed decisions about their health and well-being.

Another way to consider your audience when preparing for a talk is by setting goals that center them. Centering your audience can help you prioritize being understood. Rather than simply sharing as much information as you can fit into a talk, focus on the mutual exchange between you and your audience.

- Information-Centered Goal: I want to get as much information into this talk within my given timeframe.

- Outcome: You may have reached your goal of sharing tons of information, but at what cost?

- Audience-Centered Goal: I want to have a conversation with my audience: stay attuned to cues and questions that arise.

- Outcome: Now you are recognizing that giving you talk is an exchange, and you can begin to consider how to put this realization into practice.

Your turn: What is an audience-centered goal you can make to prepare for your talk?

How does considering your audience inform your talk?

Prepare | be intentional.

Considering your audience promotes intentionality. When you consider your audience, there is a "why" behind the decisions that you make when preparing your talk.

- What are they?

- Are they audience or information centered?

- What examples are you using? Do they capture a variety of disciplines, backgrounds, and preferences?

- How can you engage with your audience accross formats? (Ex. conducting polls, asking your audience questions, etc.)

- What questions can you ask to tailor your topic based on considerations for your audience? Explore Know Your Topic for topic identifying related resources.

- In practice, this may look like including examples in your talk that capture a variety of disciplines, backgrounds, and preferences.

- Research areas of skepticism around your topic and see if you can address some concerns in your talk.

- Before: Reflect on your assumptions about who may be in the audience.

- During: How are you feeling (ex. rushed)? What adjustments can you make mid-talk to recenter (ex. take a pause) or continue maintaining a level of comfort? How is audience engagement?

- After: Take some time to reflect on how your talk went. You can gather feedback from your audience or those who invited you. For example, you can do this through post-session evaluations or by speaking with the audience members.

Anything else I need to consider?

Deliver | checkpoint, 'consider your audience' checklist.

Your Turn: What are some additional considerations you can add to this checklist?

- Introduction to Oral Communication

- Be Prepared

- Follow a Structure

- Tell a Story

- Know Your Topic

- Elevator Pitches

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Audience Analysis in Reports

Reports are a flexible genre. A report can be anything from a one-page accident report when someone gets a minor injury on the job to a 500+ page report created by a government commission, such as The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report . Your report could be internal or external, and it could be a printed document, a PDF or even an email.

The type of report is often identified by its primary purpose, as in an accident report, a laboratory report, or a sales report. Reports are often analytical or involve the rational analysis of information. Sometimes they report the facts with no analysis at all. Other reports summarize past events, present current data, and forecast future trends. This section will introduce you to the basics of report writing.

Audience Analysis in Formal Reports

Many business professionals need to write a formal report at some point during their career, and some professionals write them on a regular basis. Key decision makers in business, education, and government use formal reports to make important decisions. Although writing a formal report can seem like a daunting task, the final product enables you to contribute directly to your company’s success.

There are several different organizational patterns that may be used for formal reports, but all formal reports contain front matter material, a body, and back matter (supplementary) items. The body of a formal report discusses the findings that lead to the recommendations. The prefatory material is therefore critical to providing the audience with an overview and roadmap of the report. The following section will explain how to write a formal report with an audience in mind.

Analyzing your Audience

As with any type of writing, when writing reports, it is necessary to know your audience. Will you be expected to write a one-page email or a formal report complete with a Table of Contents and an Executive Summary? Audience analysis will tell you.

For example, if your audience is familiar with the background information related to your project, you don’t want to bombard them with details. Instead, you will want to inform your audience about the aspects of your topic that they’re unfamiliar with or have limited knowledge of. In contrast, if your audience does not already know anything about your project, you will want to give them all of the necessary information for them to understand. Age and educational level are also important to consider when you write. You don’t want to use technical jargon when writing to an audience of non-specialists.

One of the trickier parts of report writing is understanding what your audience expects. Why is your audience reading the report? Do different parts of the report serve different purposes? Will you be expected to follow a specific template? Make sure that you have specifically responded to the expectations of your boss, manager, or client. If your audience expects you to have conducted research, make sure you know what type of research they expect. Do they want research from scholarly journal articles? Do they want you to conduct your own research? No matter what type of research you do, make sure that it is properly documented using whatever format the audience prefers (MLA, APA, and Chicago Manual of Style are some of the most commonly-used formats). As we’ve discussed in the chapter on persuasion, research will contribute to your ethos and your confidence.

For further information about what types of research you may want to include, see this article about research methods and methodologies .

Here are some questions to consider about your audience as you write:

- What does your audience expect to learn from your report?

- Do you have only one audience or multiple audiences? Do they have different levels of knowledge about the topic?

- How much research does your audience expect you to have done?

- How current does your research need to be?

- What types of sources does your audience expect you to have?

- What is the educational level of your audience?

- How much background information does your audience need?

- What technical terms will your audience need defined? What terms will they already be familiar with?

- Is there a template or style guide that you should use for your report?

- What is the cultural background of your audience?

Business Writing For Everyone Copyright © 2021 by Arley Cruthers is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.3: Audience Analysis in Reports

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 83669

- Arley Cruthers

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)