An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Mens Health

- v.15(6); Nov-Dec 2021

Perceptions and Interpretation of Contemporary Masculinities in Western Culture: A Systematic Review

Sandra connor.

1 Department of Rural Nursing & Midwifery, La Trobe Rural Health School, Mildura, Victoria, Australia

Kristina Edvardsson

2 Judith Lumley Centre, School of Nursing and Midwifery, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia

Christopher Fisher

3 Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society, School of Psychology & Public Health, LaTrobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Evelien Spelten

4 Department of Community Health, La Trobe Rural Health School, Mildura, Victoria, Australia

The social construct of masculinity evolves in response to changes in society and culture. Orthodox masculinity is mostly considered to be hegemonic and is evidenced by the dominance of men over women and other, less powerful men. Contemporary shifts in masculinity have seen an emergence of new masculinities that challenge traditional male stereotypes. This systematic review aims to review and synthesize the existing empirical research on contemporary masculinities and to conceptualize how they are understood and interpreted by men themselves. A literature search was undertaken on 10 databases using terms regularly used to identify various contemporary masculinities. Analysis of the 33 included studies identified four key elements that are evident in men’s descriptions of contemporary masculinity. These four elements, (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c) Physicality, and (d) Resistance, are consistent with the literature describing contemporary masculinities, including Hybrid Masculinities and Inclusive Masculinity Theory. The synthesized findings indicate that young, middle-class, heterosexual men in Western cultures, while still demonstrating some traditional masculinity norms, appear to be adopting some aspects of contemporary masculinities. The theories of hybrid and inclusive masculinity suggest these types of masculinities have several benefits for both men and society in general.

Introduction

The concept of masculinity in broad terms can be defined as a social construct that encompasses “the behaviors, languages, and practices, existing in specific cultural and organizational locations, which are commonly associated with men and thus culturally defined as not feminine” ( Whitehead & Barrett, 2001 , pp. 15–16). Orthodox masculinity is mostly considered to be hegemonic and is evidenced by the dominance of men over women and other, less powerful men ( Connell, 1987 , 1995 ; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005 ). Traditional masculinity norms, socialize men to project strength and dominance particularly over others, and the inherent restrictive stereotypes require men to be stoic, independent, tough, and powerful ( Courtenay, 2000 ).

These stereotypes influence men’s individual health outcomes and have societal impacts. Men, in general, have poorer health outcomes and young men are at greater risk from injury, either accidentally through risk-taking activities or self-inflicted. Young men are also less likely to seek health care. This correlates with traditional masculinity norms that reinforce beliefs around the male body being strong ( Courtenay, 2000 ; Mahalik et al., 2007 )

In addition, there are socio-negative perspectives consistently found in orthodox masculinity. These include the sexual degradation and objectification of women and the culture of homophobia ( Bevens & Loughnan, 2019 ; Hughson, 2000 ; Messner, 1992 ). Both perspectives serve to establish the sexual prowess and heterosexuality of the individual thereby fortifying their masculinity.

However, the social construct of masculinity is not fixed and has always evolved over time in response to changes in society and culture ( Britten, 2001 ; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005 ; Waling, 2020 ; Whitehead & Barrett, 2001 Contemporary shifts in masculinity have seen an emergence of new masculinities that challenge these restrictive traditional stereotypes. Orthodox masculinities and traditional masculinity norms are being challenged and, contemporary culture is embracing the “new male” ( Smith & Inhorn, 2016 ).

The body of global literature dedicated to the Critical Studies on Men and Masculinities clearly demonstrates that the conceptualization of masculinity has evolved and will continue to do so ( Bridges & Pascoe, 2018 ; Britten, 2001 ; Elliott, 2019 ). The intersection of class, race, gender, and sexuality all contribute to how masculinity is perceived in specific settings and under specific conditions. It is the combination of these elements that leads to a divergence in traditional masculinity thinking and the emergence of new masculinities ( Messerschmidt & Messner, 2018 ). Contemporary masculinities are now emerging in response to changes in society’s expectations of how men should behave ( Britten, 2001 ; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005 ; Whitehead & Barrett, 2001 ).

These contemporary masculinities include Hybrid masculinities ( Demetriou, 2001 ) and Inclusive Masculinity Theory ( Anderson, 2009 ). The concept of Hybrid Masculinities emerged at the turn of this century with Demetriou’s (2001) recognition that straight white men who occupied positions of power in the masculine hierarchy were beginning to adopt cultural elements of subordinate and marginalized masculinities. The selective integration of these elements into traditional masculinity creates a hybrid wherein the adopters of these elements, remain tough and strong, while being able to show sensitivity ( Arxer, 2011 ; Barber, 2016 ; Bridges & Pascoe, 2018 ; Messerschmidt & Messner, 2018 ; Pfaffendorf, 2017 ).

Inclusive Masculinity Theory developed from the research findings of Eric Anderson (2009) and is supported by the work of Mark McCormack (2014) . Inclusive Masculinity Theory is underpinned by their findings, indicating that homophobia is increasingly being rejected by straight men ( Anderson, 2009 ; Anderson & McCormack, 2018 ). Moreover, straight men, are including gay peers in social networks and are engaging both emotionally and physically with other men.

Much has been written on these contemporary masculinity theories, including extensive critiques of the disparities between the two. While the behaviors belonging to each of the masculinity theories have been described by researchers, to date there has been no research that synthesizes how men themselves understand and interpret these new masculinities. There is limited evidence of men’s experiences, understanding, and perceptions of contemporary masculinities.

This paper, therefore, aims to systematically review and synthesize the existing peer-reviewed published empirical research on contemporary masculinities to determine how contemporary masculinity is viewed by men themselves, rather than from the point of view of the researcher. This review aims to capture men’s voices regarding contemporary masculine enculturation.

A search was undertaken on the following databases, MEDLINE, CINAHL, JStor, SocioIndex, Web of Science, Informit Complete, Psychinfo Ovid, ProQuest Social science, ProQuest Central, and Sociological Abstracts. Keywords were identified during extensive reading in the field of Critical Studies on Men & Masculinities. This reading was undertaken in all forms of literature, including empirical research, books, and opinion pieces. Many of the words identified are not “typically” found in the formal literature, however, to be as inclusive as possible and to ensure a rigorous and thorough search, all keywords identified were used.

The medical subject heading (MeSH) “masculin*” was used with the following keywords hybrid, inclusive, emerg*, divergent, oppositional, resistant, dialogical, caring, new, flexible, chameleon, soft-boiled, person*, cool, contemporary, alternate, modern, metrosexual, hipster and bromance.

Articles published from January 1, 1990, to October 2019 were reviewed and assessed for eligibility using the PRISMA 2009 checklist for systematic reviews and meta-analysis ( Moher et al., 2009 ) ( Figure 1 ).

PRISMA Flow Chart.

Inclusion criteria are as follows: (a) Empirical peer-reviewed studies, published in journals, identifying how men perceive and interpret, contemporary masculinities; (b) English language; and (c) Research conducted in Western high-income countries. High-income countries are those defined by the World Bank as being such during 2019; and (d) Research conducted since 1990.

Exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) Not empirical research, for example, book, review, opinion piece, conference paper, editorial, letter, dissertation, or non-peer-reviewed publication; (b) The focus was on clinical, medical, chronic disease or health outcomes; (c) Literature that used masculinity as an explanation for male behaviors including “toxic” masculinity, sexual violence, aggression, and gender inequality; and (d) Article was not in English, not conducted in a Western high-income country or conducted before 1990.

The extensive search produced 2,083 records. Records were imported into Covidence software and 873 duplicates were identified and removed. The abstracts of the remaining 1210 records were then screened independently by two authors against the previously identified inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 1,010 records were excluded leaving 200 records to be assessed at full-text stage. At full-text review, all records were read in detail by two authors, and the inclusion, exclusion criteria were applied. Conflicts were resolved by the two authors reaching a consensus following discussion. A further 166 records were excluded following full-text review. Reasons for exclusion were 69 were not empirical research, 2 were pre-1990, 6 were from non-Western countries, 3 were not in English, and 2 were focused on health outcomes. The remaining 84 studies did not identify how males perceive and interpret contemporary masculinities. The excluded studies used masculinity to describe men’s behaviors, including but not limited to, sexual orientation, violence, and “toxic masculinity.” This left 34 studies in total, 32 qualitative studies, and 2 mixed methods studies to be assessed for methodological quality.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklists for prevalence studies (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017a) and qualitative research ( Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017b ) were chosen to assess the methodological quality of the articles, as they are designed to appraise both qualitative and mixed-methods studies specifically ( The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017a , & 2017b ). Scores for each article are included under the Quality Rating column in the summary of Studies ( Table 2 ). The appraisal process was undertaken independently by two authors. Any disagreement was resolved by a third author. One study did not meet the quality appraisal criteria and was excluded from the review, leaving 33 studies in the review.

Summary of Studies.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by the first author using a template that included the following domains (a) Author/s and year of publication, (b) country of study and setting, (c) aim of the study, (d) study design, (e) study methods, (f) theoretical background, (g) sample size, (h) population, and (i) and results.

Data Syntheses

Synthesis of the data was undertaken using thematic analysis. The first author undertook the thematic analysis, and this was reviewed by co-authors.

Thematic analysis is a systematic multistage process requiring the author to continually revisit the data. In the first phase of thematic analysis the author is required to read the articles identifying recurring elements in each. These elements were then reviewed for commonalities between them and clustered into larger groups called concepts. The concepts represent the underlying abstract ideology of the data. Finally, the concepts were further grouped into Global Themes. Global Themes encompass both the recurring themes and concepts and represent a single idea that has been identified in, and is supported by, the data ( Attride-Stirling, 2001 ; Parahoo, 2006 ). Four global themes were identified within the data: (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c3) Physicality, and (d) Resistance ( Table 1 ).

Recurring Elements, Concepts, and Global Themes.

While the search criteria included studies from 1990, all 33 articles in this systematic review, that met the inclusion criteria, are post 2000, with only four being published before 2010 ( Anderson, 2005 , 2008 ; Finn & Henwood, 2009 ; Henwood & Procter, 2003 ).

From the 33 articles, the profile of the participants included men from middle-class backgrounds, aged between 16 and 25 years ( n = 19; 57.6%), men from middle-class backgrounds aged between 18 and 76 years ( n = 3; 9.1%), men from working-class background aged between 16 and 19 years ( n = 1; 3%), and men where details of class and age were not provided ( n = 10; 30.3%).

Fourteen (42.4%) of the participant cohorts self-identified as heterosexual, the remainder of the studies (57.6%) did not specify participant sexual preference.

The majority of the 33 studies were undertaken in either sporting ( n = 10; 30.3%) or educational settings such as high schools or universities ( n = 8; 24.2%) with the remainder being undertaken with fathers ( n = 6; 18.2%), through online blogs and podcasts ( n = 5; 15.2%) or in non-specific settings ( n = 4; 12.1%). Table 2 provides details of all studies included. Global themes identified will be discussed within the context of each setting.

Inclusivity

The Global Theme of Inclusivity relates to the participants’ acceptance of homosexuality, decreasing levels of homophobia, as well as decreasing levels of misogyny, and a general desire for gender equality. Twenty-four of the 33 studies reported that the participants displayed decreased levels of homophobia ( Adams, 2011 ; Anderson, 2008 , 2011 , 2012 ; Anderson et al., 2019 ; Anderson & McCormack, 2015 ; Anderson & McGuire, 2010 ; Blanchard et al., 2017 ; Caruso & Roberts, 2018 ; Drummond et al., 2014 ; Fine, 2019 ; Hall et al., 2012 ; Jarvis, 2013 ; Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason, 2018 ; Magrath & Scoats, 2019 ; McCormack, 2011 , 2014 ; Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017 ; Morris & Anderson, 2015 ; Pfaffendorf, 2017 ; Roberts et al., 2017 ; Robinson et al., 2018 ; Scoats, 2017 ; White & Hobson, 2017 ). This ranged from what was described as shifting attitudes toward homosexuality ( Jarvis, 2013 ), to the complete absence of homophobia ( Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017 ).

Jarvis (2013) , identified that while their heterosexual participants were open to participating in sport alongside gay men, some still adhered to traditional masculinity norms and found subtle ways to assert their heterosexuality. Jarvis (2013) acknowledges that while the participants in his study happily joined gay sporting clubs, most ensured that the members were aware of their heterosexuality, one even bringing his girlfriend to a match as evidence.

Morales and Caffyn-Parsons (2017) , in their study of 16 and 17-year-old cross-country runners in the United States identified a complete lack of homophobia among the participants.

Seventeen of the 24 studies examining homophobia also indicated that the participants not only rejected homophobia, they also rejected misogyny and advocated for gender equality ( Anderson, 2005 , 2008 ; Anderson & McGuire, 2010 ; Brandth & Kvande, 2018 ; Caruso & Roberts, 2018 ; Fine, 2019 ; Finn & Henwood, 2009 ; Gottzén & Kremer-Sadlick, 2012 ; Greenebaum & Dexter, 2018; Hall et al., 2012 ; Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason, 2018 ; Johansson, 2011 ; Lee & Lee, 2018 ; Magrath & Scoats, 2019 ; McCormack, 2011 ; Morris & Anderson, 2015 ; Roberts, 2018 ).

The fathers in the study by Brandth and Kvande (2018) demonstrated inclusivity by undertaking what is traditionally considered to be women’s work, such as laundry, cooking, and child care. Most participants asserted that this is not even to be questioned, and such tasks are now “taken for granted competence” in men. Johansson (2011) and Lee and Lee (2018) both demonstrated their participants’ desire to father in gender-equal relationships with their partners. Three studies set in the online space, Caruso and Roberts (2018) , Fine (2019) , and Morris and Anderson (2015) , identified that their participants regularly discussed topics such as gender inequity and actively rejected misogyny and homophobia.

Emotional Intimacy

The global theme of Emotional Intimacy relates to the participants sharing their intimate feelings and displaying their emotions with their male friends. This level of emotional vulnerability is in direct contrast to traditional masculinity norms that require men to be stoic and resist sharing feelings and emotions, particularly with another man ( Courtenay, 2000 ).

Emotional intimacy was identified in 23 of the studies ( Adams, 2011 ; Anderson, 2008 , 2011 , 2012 ; Anderson & McGuire, 2010 ; Blanchard et al., 2017 ; Brandth & Kvande, 2018 ; Caruso & Roberts, 2018 ; Fine, 2019 ; Finn & Henwood, 2009 ; Gottzén & Kremer-Sadlick, 2012 ; Henwood & Procter, 2003 ; Jóhannsdóttir & Gíslason, 2018 ; Johansson, 2011 ; Lee & Lee, 2018 ; Magrath & Scoats, 2019 ; McCormack, 2011 ; McCormack, 2014 ; Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017 ; Morris & Anderson, 2015 ; Roberts et al., 2017 ; Robinson et al., 2018 ; White & Hobson, 2017 ).

Anderson (2011) described participants hugging and comforting each other openly when sad or upset. Anderson & McGuire (2010) describe their rugby players as reporting that they support each other when the coaches give them a hard time, again reporting that they are “there for each other.” Likewise, the 16 to 18-year-old men in McCormack’s (2011 , 2014 ) studies expressed their feelings freely and openly with their man friends.

In the studies focused on fatherhood, the element of emotional intimacy was in relation to their children rather than with a man friend. Johansson (2011) reports that the first-time fathers in this Swedish study prioritized intimate relations, family life, and emotional experiences. In addition, they wanted to find a balance between work and family life.

The study of a men’s online body blog by Caruso and Roberts (2018) identified that the men users shared vulnerability with each other on topics such as, but not limited to, body image and sexuality. The McElroy brothers in Fine’s (2019) study demonstrate emotional intimacy to their audience through authentic dialogue. Similarly, Morris and Anderson (2015) demonstrated that Charlie, the vlogger in their study, achieved emotional intimacy with his audience through authentic sharing of himself.

The global theme of emotional intimacy was also reported by both Jóhannsdóttir and Gíslason (2018) and Magrath and Scoats (2019) . The young Icelandic men in the study by Jóhannsdóttir and Gíslason (2018) reported that they were able to talk to their man friends not just about what they did but also about how they felt. They describe these friendships as caring and their man friends as emotional support.

Physicality

The global theme of physicality refers to the participants demonstrating increased levels of intentional touching. Fourteen studies (42.4%) reported this theme; however, it was more evident in sporting settings ( Adams, 2011 ; Anderson, 2011 ; Anderson & McCormack, 2015 ; Morales & Caffyn-Parsons, 2017 ; Roberts et al., 2017 ) and educational settings ( Anderson et al., 2019 ; Blanchard et al., 2017 ; Drummond et al., 2014 ; McCormack, 2014 ; Robinson et al., 2018 ; White & Hobson, 2017 ). However, there was evidence of increased levels of intentional touching in other settings ( Brandth & Kvande, 2018 ; Magrath & Scoats, 2019 ; Scoats, 2017 ).

Morales and Caffyn-Parson’s (2017) results indicated that the participants regularly hugged and touched each other affectionately. They described their hugs as “a full embrace” or “full frontal,” rather than a “brief hug and two strong pats on the back.” It was observed that participation in these behaviors was open and without fear of rejection. The participants in this American study declared that kissing was not a way that they would normally show affection to their man friends but that did not mean that they would not do it. Adams (2011) , Anderson (2011) , and Roberts et al. (2017) , all report high levels of physical closeness within their participant groups. Hugging for an extended period is the most common behavior, but sharing beds, leaning up against each other, and touching face, and hair occurs regularly. Importantly these behaviors were performed openly with the authenticity of feeling.

The studies of Drummond et al. (2014) and Anderson et al. (2019) aimed to explore the frequency, context, and meanings of same-sex kissing among university men aged 18 to 25 years in Australia and the United States.

Both studies reported that same-sex kissing occurred among the participants, but it is contextualized within close friendship groups, during sport, or when alcohol is consumed. Most participants indicated that kissing another male was fine for heterosexuals in certain circumstances, such as, if it followed scoring a goal, or during a night out in a public place. Participants who did not engage in same-sex kissing revealed this act was associated with being gay, indicating that there is still social pressure in some young men to assert their heterosexual identity, in line with traditional masculinity norms.

The global theme of resistance refers to the participants’ rejection of orthodox masculinity and traditional masculinity norms. Of the 33 studies included in the systematic review, only three did not demonstrate this ( Anderson, 2011 ; Anderson & McCormack, 2015 ; Roberts et al., 2017 ).

The male cheerleaders in Anderson (2005) were not concerned about being considered “gay” by other men. They also had no concerns undertaking traditional women’s roles within their sport, questioning the need for gender roles at all. These findings were also supported by Morales and Caffyn-Parsons (2017) and Anderson and McGuire (2010) .

Anderson’s (2011) study on American soccer players provided evidence that these participants were “eschewing violence” (p. 736). Indeed, of the 22 participants, most reported that they had never been in a fight and did not see the sense in it. An earlier study by Anderson (2012) , among high school students, similarly demonstrated these participants rejected violence. The school disciplinary record indicated that there were no physical altercations between any students during the school year.

McCormack (2011 , 2014 ), and Pfaffendorf (2017) reported evidence of rejection of aggression and violence in their studies on boys in education settings.

In the context of the fatherhood-focused studies, resistance was related to rejection of orthodox masculinity stereotypes and finding non-traditional ways of fathering, which included valuing positive emotions and taking pride in their caregiving role ( Johansson, 2011 ; Lee & Lee, 2018 ).

The men in Magrath and Scoats (2019) reaffirm their rejection of orthodox masculinity norms by continuing to support each other in a caring and vulnerable way. Jóhannsdóttir and Gíslason (2018) report that the young men in their study are moving away from the stereotypical and traditional notions of masculinity. The vegan men in Greenbaum and Dexter (2018) embrace typically feminine traits such as compassion and empathy which is the antithesis of orthodox masculinity.

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the existing empirical research on contemporary masculinities and conceptualize how men perceive and interpret these new masculinities. From the literature, four key concepts that seem integral to the understanding and performance of contemporary masculinities were identified: (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c) Physicality, and (d) Resistance. These concepts can be used to better understand men’s perceptions of contemporary masculinities and to construct new measurement tools to assess the performance of contemporary masculinities which in turn can inform program and policy development.

Much of the research reviewed, 24 of the 33 articles, were undertaken by scholars using Inclusive Masculinity as the Theoretical background for their studies. It is therefore not surprising that this review identified males’ understanding of contemporary masculinities to include decreased levels of homohysteria, and increased physical intimacy as this is consistent with IMT ( Anderson, 2009 ). While not negating the findings of this review, this does suggest that there is limited empirical research being undertaken on contemporary masculinities.

The majority of participants in the studies reviewed were middle-class men between the ages of 16 and 25. The question needs to be asked, are the elements of inclusivity, emotional intimacy, physicality, and resistance, identified in this review, a result of intentional masculinity behavior changes. or are they a generational reaction to the current discourse around changing masculinity ( Elliott, 2019 ; Ralph & Roberts, 2020 )? The participants’ profile suggests that these young men are privileged and already have the balance of power required to be able to choose how to perform their masculinity ( Bridges & Pascoe, 2018 ; Connell, 1995 ).

While there is clear evidence in these studies of behavior change in young men, there is also conflicting evidence to indicate that these same young men are still adhering to some of the traditional masculinity norms such as portraying a heterosexual identity with its inherent power over “others” ( Bridges & Pascoe, 2018 ; Connell, 1987 , 1995 ; Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005 ). The participants appear to be accepting of differences in sexuality but many still assert their hetero status.

The synthesized findings indicate that young, middle-class, heterosexual men in Western cultures, while still demonstrating some traditional masculinity norms, appear to be adopting some aspects of contemporary masculinities. The scholars of contemporary masculinity theories suggest that this has several benefits. Acceptance of others, including those of differing genders and sexualities, contributes to decreasing levels of violence ( Anderson et al., 2019 ). Increased acceptance of women as equals assists in breaking down the unequal power relations between men and women and contributes to a more gender-equal society ( McCormack, 2011 ). For men themselves, having the freedom to be open with feelings and emotions and to be able to show vulnerability, has a direct positive effect on their mental health and well-being ( Anderson, 2011 ; Anderson & McGuire, 2005; Peretz et al., 2018 ). In addition, increased emotional and physical contact with others including other men contributes to more positive relationships, which benefits society ( Brandth & Kvande, 2018 ; Henwood & Procter, 2003 ; Peretz et al., 2018 ). Future research into contemporary masculinities would benefit by including more diverse socio-economic groups and being undertaken in more diverse spaces.

Limitations

A significant limitation to this study is the exclusion of non-peer-reviewed published empirical research studies. This criteria appear to have privileged the work of Anderson and scholars of IMT. A significant number of articles by scholars other than Anderson were excluded from the review as they were books, discussion papers, theoretical papers, or book chapters. Contemporary masculinity research may benefit from scholars aiming to publish more peer-reviewed empirical research to solidify the field in wider academic circles.

A further limitation was the exclusion of studies that were not done in Western high-income countries or were not in English. As the construct of masculinity is defined by specific cultural behaviors and practices, limiting this review to Western countries was designed to ensure a consistent understanding of the concept of masculinity. It is acknowledged that there is a vast amount of research from non-English speaking and non-Western countries and there is a need for research to summarize how contemporary masculinities are understood and described in these contexts.

This systematic review aimed to synthesize the existing research on contemporary masculinities and to conceptualize how they are understood and interpreted by men in the literature. The review identified four concepts that are evident in the performance of contemporary masculinities. The concepts, (a) Inclusivity, (b) Emotional Intimacy, (c) Physicality, and (d) Resistance, provide an increased recognition and understanding of how contemporary masculinities are being performed and how young men can challenge orthodox masculinities and traditional manly stereotypes.

These elements are not intended to be a concrete measure of contemporary masculinities, nor is this new knowledge. It is, however, a synthesis of the existing knowledge, particularly, Inclusive Masculinity Theory and Hybrid Masculinity. The elements do provide a framework that demonstrates the differences between the behaviors of new and contemporary masculinities and the behaviors of orthodox masculinities.

Author Contributions: First author undertook the literature search supported by second and third authors. All three authors participated in screening of records in Covidence, with all records screened by first author and second and third authors screening half the records each in the role of second reviewer. First author conducted the analyses in collaboration with second and third authors. First author drafted the manuscript and, all authors contributed to ongoing revisions of the manuscript and approved of definitive version. All authors accept responsibility for submitted manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review.

Consent for Publication: “Not applicable.”

Availability of Data and Material: The data sets used to support the conclusions of this article are included as tables in the Results section.

- Adams A. (2011). “Josh wears pink cleats”: Inclusive masculinity on the soccer field . Journal of Homosexuality , 58 ( 5 ), 579–596. 10.1080/00918369.2011.563654 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E. (2005). Orthodox and inclusive masculinity, competing masculinities among heterosexual men in a feminized terrain . Sociological Perspectives , 48 ( 3 ), 337–355. https://doi.org/org/10.1525/sop.2005.48.3.337 [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E. (2008). Inclusive masculinity in a fraternal setting . Men and Masculinities , 10 ( 5 ), 604–620. 10.1177/1097184X06291907 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E. (2009). Inclusive masculinity: The changing nature of masculinities . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E. (2011). Inclusive masculinities of university soccer players in the American Midwest . Gender and Education , 23 ( 6 ), 729–744. 10.1080/09540253.2010.528377 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E. (2012). Inclusive Masculinity in a physical education setting . Journal of Boyhood Studies , 6 ( 2 ), 151–165. 10.3149/thy.0602.151 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E., McCormack M. (2015). Cuddling and spooning . Men and Masculinities , 18 ( 2 ), 214–230. 10.1177/1097184x14523433 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E., McCormack M. (2018). Inclusive masculinity theory: Overview, reflection and refinement . Journal of Gender Studies , 27 ( 5 ), 547–561. 10.1080/09589236.2016.1245605 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E., McGuire R. (2010). Inclusive masculinity theory and the gendered politics of men’s rugby . Journal of Gender Studies , 19 ( 3 ), 249–261. 10.1080/09589236.2010.494341 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson E., Ripley M., McCormack M. (2019). A mixed-method study of same-sex kissing among college-attending heterosexual men in the US . Sexuality and Culture , 23 ( 1 ), 26–44. 10.1007/s12119-018-9560-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arxer S. L. (2011). Hybrid masculine power: Reconceptualizing the relationship between homosociality and hegemonic masculinity . Humanity & Society , 35 ( 4 ), 390–422. 10.1177/016059761103500404 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Attride-Stirling J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytical tool for qualitative research . Qualitative Research , 1 ( 3 ), 385–405. 10.1177/146879410100100307 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barber K. (2016). Styling masculinity: Gender, class and inequality in the men’s grooming industry . Rutgers University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bevens C. L., Loughnan S. (2019). Insights into men’s sexual aggression toward women: Dehumanization and objectification . Sex Roles , 81 ( 11–12 ), 713–730. 10.1007/s11199-019-01024-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blanchard C., McCormack M., Peterson G. (2017). Inclusive Masculinities in a working-class sixth form in Northeast England . Journal of Contemporary Ethnography , 46 ( 3 ), 310–333. 10.1177/0891241615610381 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brandth B., Kvande E. (2018). Masculinity and fathering alone during parental leave . Men and Masculinities , 21 ( 1 ), 72–90. 10.1177/1097184x16652659 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bridges T., Pascoe C. J. (2018). On the elasticity of gender hegemony: Why hybrid masculinities fail to undermine gender and sexual inequality . In Messerschmidt J. W., Martin P. Y., Messner M. A., Connell R. (Eds.), Gender reckonings (pp. 254–274). New York University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Britten A. (2001). Masculinities and masculinism . In Whitehead S. M., Barrett F. J. (Eds.), The masculinities reader (pp. 51–71). Polity Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Caruso A., Roberts S. (2018). Exploring constructions of masculinity on a men’s body-positivity blog . Journal of Sociology , 54 ( 4 ), 627–646. 10.1177/1440783317740981 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Connell R. W. (1987). Gender and power . Allen & Unwin. [ Google Scholar ]

- Connell R. W. (1995). Masculinities . Polity Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Connell R. W., Messerschmidt J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept . Gender and Society , 19 ( 6 ), 829–859. 10.1177/0891243205278639 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health . Social Science Medicine , 50 , 1385–1401. 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Demetriou D. (2001). Connell’s concept of hegemonic masculinity: A critique . Theory and Society , 30 , 337–336. [ Google Scholar ]

- Drummond M. J. N., Filiault S. M., Anderson E., Jeffries D. (2014). Homosocial intimacy among Australian undergraduate men . Journal of Sociology , 51 ( 3 ), 643–656. 10.1177/1440783313518251 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott K. (2019). Negotiations between progressive and “traditional” expressions of masculinity among young Australian men . Journal of Sociology , 55 ( 1 ), 108–123. 10.1077/1440783318802996 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fine L. E. (2019). The McElroy brothers, new media, and the queering of white nerd masculinity . Journal of Men’s Studies , 27 ( 2 ), 131–148. 10.1177/1060826518795701 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Finn M., Henwood K. (2009). Exploring masculinities within men’s identificatory imaginings of first-time fatherhood . British Journal of Psychology , 48 ( Pt 3 ), 547–562. 10.1348/014466608X386099 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottzén L., Kremer-Sadlik T. (2012). Fatherhood and youth sports . Gender & Society , 26 ( 4 ), 639–664. 10.1177/0891243212446370 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenbaum J., Dexter B. (2018). Vegan men and hybrid masculinity . Journal of Gender Studies , 27 ( 6 ), 637–648. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1287064 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall M., Gough B., Seymour-Smith S., Hansen S. (2012). On-line constructions of metrosexuality and masculinities: A membership categorization analysis . Gender and Language , 6 ( 2 ), 379–403. 10.1558/genl.v6i2.379 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Henwood K., Procter J. (2003). The ‘good father’: Reading men’s accounts of paternal involvement during the transition to first-time fatherhood . British Journal of Social Psychology , 42 ( 3 ), 337–355. 10.1348/01446660332243819 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hughson J. (2000). The boys are back in town: Soccer support and the social reproduction of masculinity . Journal of Sport and Social Issues , 24 ( 1 ), 8–23. 10.1177/0193723500241002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jarvis N. (2013). The inclusive masculinities of heterosexual men within UK gay sport clubs . International Review for the Sociology of Sport , 50 ( 3 ), 283–300. 10.1177/1012690213482481 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017. a). Critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies . https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017. b). Critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research . https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Jóhannsdóttir Á., Gíslason I. V. (2018). Young Icelandic men’s perception of masculinities . Journal of Men’s Studies , 26 ( 1 ), 3–19. 10.1177/1060826517711161 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johansson T. (2011). Fatherhood in transition: Paternity leave and changing masculinities . Journal of Family Communication , 11 ( 3 ), 165–180. 10.1080/15267431.2011.561137 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee J. Y., Lee S. J. (2018). Caring is masculine: Stay-at-home fathers and masculine identity . Psychology of Men & Masculinity , 19 ( 1 ), 47–58. 10.1037/men0000079 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Magrath R., Scoats R. (2019). Young men’s friendships: Inclusive masculinities in a post-university setting . Journal of Gender Studies , 28 ( 1 ), 45–56. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1388220 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahalik J. R., Walker G., Levi-Minzi M. (2007). Masculinity and health behaviors in Australian men . Psychology of Men & Masculinity , 8 ( 4 ), 240–249. 10.1037/1524-9220.8.4.240 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCormack M. (2011). Hierarchy without Hegemony: Locating boys in an inclusive school setting . Sociological Perspectives , 54 ( 1 ), 83–101. 10.1525/sop.2011.54.1.83 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCormack M. (2014). The intersection of youth masculinities, decreasing homophobia and class: An ethnography . British Journal of Sociology , 65 ( 1 ), 130–149. 10.1111/1468-4446.12055 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Messerschmidt J. W., Messner M. A. (2018). Hegemonic, nonhegemonic, and “new” masculinities . In Messerschmidt J. W., Martin P. Y., Messner M. A., Connell R. (Eds.), Gender reckonings (pp. 35–56). New York University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwtb3r.7 [ Google Scholar ]

- Messner M. (1992). Power at play: Sports and the problem of masculinity . Beacon. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement . PLOS Medicine , 6 ( 7 ), Article e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morales L. E., Caffyn-Parsons E. (2017). “I love you, guys”: A study of inclusive masculinities among high school cross-country runners . Boyhood Studies-An Interdisciplinary Journal , 10 ( 1 ), 66–87. 10.3167/bhs.2017.100105 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morris M., Anderson E. (2015). ‘Charlie is so cool like’: Authenticity, popularity and inclusive masculinity on YouTube . Sociology , 49 ( 6 ), 1200–1217. 10.1177/0038038514562852 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parahoo K. (2006). Nursing research principles, process and issues (2nd ed). Palgrave Macmillan. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peretz T., Lehrer J., Dworkin S. L. (2018). Impacts of men’s gender-transformative personal narratives: A qualitative evaluation of the Men’s story project . Men and Masculinities , 23 ( 1 ), 104–126. 10.1177/1097184X18780945 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfaffendorf J. (2017). Sensitive cowboys: Privileged young men and the mobilization of Hybrid Masculinities in a therapeutic boarding school . Gender & Society , 31 ( 2 ), 197–222. 10.1177/0891243217694823 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ralph B., Roberts S. (2020). One small step for man: Change and continuity in perceptions and enactments of homosocial intimacy among young Australian men . Men and Masculinities , 21 ( 1 ), 83–103. 10.1177/1097184X18777776 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts S. (2018). Domestic labour, masculinity and social change: Insights from working-class young men’s transitions to adulthood . Journal of Gender Studies , 27 ( 3 ), 274–287. 10.1080/09589236.2017.1391688 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts S., Anderson E., Magrath R. (2017). Continuity change and complexity in the performance of masculinity among elite young footballers in England . British Journal of Sociology , 68 ( 2 ), 336–357. 10.1111/1468-4446.12237 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson S., Anderson E., White A. (2018). The Bromance: Undergraduate male friendships and the expansion of contemporary homosocial boundaries . Sex Roles , 78 ( 1–2 ), 94–106. https://doi.org/0.1007/s11199-017-0768-5 [ Google Scholar ]

- Scoats R. (2017). Inclusive masculinity and Facebook photographs among early emerging adults at a British university . Journal of Adolescent Research , 32 ( 3 ), 323–345. 10.1177/0743558415607059 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith S., Inhorn M. C. (2016). Emergent masculinities, men’s health and the Movember movement . In Gideon J. (Ed.), Handbook on gender & health (pp. 436–456). Edward Elgar. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waling A. (2020). White masculinity in contemporary Australia: The good Ol’ Aussie Bloke . Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- White A., Hobson M. (2017). Teachers’ stories: Physical education teachers’ constructions and experiences of masculinity within secondary school physical education . Sport, Education and Society , 22 ( 8 ), 905–918. 10.1080/13573322.2015.1112779 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitehead S. M., Barrett F. J. (2001). The sociology of masculinity . In Whitehead S. M., Barrett F. J. (Eds.), The masculinities reader (pp. 1–26). Polity Press. [ Google Scholar ]

The Concepts of Man and Human Purpose in Contemporary Indian Thought

Cite this chapter.

- D. P. Chattopadhyaya

Part of the book series: Studies in Philosophy and Religion ((STPAR,volume 6))

110 Accesses

Whatever man does bears the imprint of his being. In the case of man what he is and what he is able to do cannot be neatly demarcated. Thought and action do not only interpenetrate but also interact in human situation: one influences and is influenced by the other. Philosophy is essentially a reflective activity partly expressing and partly concealing its author. The demand of the ‘scientistic’ philosopher that knowledge worth the name must be completely impersonal betrays his lack of understanding of the reflective character and anthropological root of knowledge. Complete impersonalization of knowledge (and action) is humanly impossible. For man can never get rid of himself either in knowing or in doing. The impossibility of knowledge without knower and doing without doer does not imply merely a linguistic relativity but a deeper conceptual interdependence of such pains of concepts as knowledge-knower, doing-doer, and action-agent. This is a very old but important view. The anthropological orientation of the Indian thinkers in general and the contemporary ones in particular are very clear indeed. The dualism between nature and man or that between pure reason and practical reason has never been a dominant feature of Indian philosophy, and in this respect its difference from European philosophy is noteworthy. Knowledge, whether it be of nature or of man, is regarded by most of the Indian philosophers as a necessary condition of human perfection.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979). Übers.: Der Spiegel der Natur: Eine Kritik der Philosophie (1981)

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , London, 1954, p. 69.

Google Scholar

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , London, 1954, p. 14.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man , London, 1958, p. 139.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 53.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 56.

This point has been persuasively argued, among others, by P. F. Strawson. See his imaginative and careful book, Individuals , ch. 3.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man , p. 223.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man , p. 225.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 61.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man , p. 131.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man , p. 119; see also Atmaparichay , Collected Works (Centenary Govt, ed.), Vol. 10, p. 173. Rabindranath’s position inevitably reminds us of Kant’s. But Rabindranath is neither a dualist nor a formalist like Kant.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 38.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Sense and Non-Sense , North Western University Press, 1964, p. 94.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 95.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 98; see also Kant, Critique of Pure Reason , A 107–9. Husserl observes, ‘Objects exist for me, and are for me what they are, only as objects of actual and possible consciousness’. Cartesian Meditation , (tr. Dorion Cairns), 1960, p. 65.

Rabindranath Tagore, Collected Works , Vol. 12, (Centenary Govt, ed.), pp. 135–7.

Rabindranath Tagore, The Religion of Man , p. 188; see also his Collected Works , Vol. 13, (Centenary Govt, ed.) p. 307.

That harmony is the key concept of Tagore’s philosophy has been argued most persuasively by S. N. Ganguly, P. K. Roy and N. N. Banerjee in their book, Rabindradarsan (in Bengali), Visva-Bharati, 1969. So far as I am aware this is the best introduction to Tagore’s philosophy. The insightful ideas of this rather small book, I hope, would be further developed.

Rabindranath Tagore, Personality , p. 31.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , New York 1949, pp. 295–98. See especially 9. 317, where he argues that duality is apparent.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , New York 1949, pp. 295–98. See especially 9. 317, where he argues that duality is apparent, Book Two, ch. XXIII. Sri Aurobindo writes, ‘mind is only a middle term of consciousness ... a transitional being ... opening to what exceeds it ... super-mind and supermanhood’, p. 754.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , New York 1949, pp. 489–90. Sri Aurobindo is for dialectical intellect only so far as it helps us to clarify and order our knowledge and not prepared to allow the rigid frame of its logic to govern our intuitive and germinal conceptions.

Max Scheler, Philosophische Weltanschauung , München, 1954, p. 62.

Quoted from Dr. J. N. Mohanty’s ‘Integralism and Modern Philosophical Anthropology’ in The Integral Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo , Haridas Chaudhuri and Frederic Spiegelberg (eds.), London, 1960, p. 156.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , p. 643; see also pp. 799–800.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , p. 372; see also Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Collection [AICEC], Vol. IX (which contains three books — The Human Cycle [ HC ], The Ideal of Human Unity [ IHU ], and War and Self-Determination [ WSD ], Pondicherry, 1962, p. 157.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , p. 640.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , p. 718.

Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Collection , Vol. IX, [ HC ], p. 315.

Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Collection , Vol. IX, [ HC ], p. 314; see also The Life Divine , pp. 612–3.

Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Collection , Vol. IX, [ HC ], p. 297; see also p. 62. Sri Aurobindo’s argument at this stage (pp. 338–47) seems to be addressed to such philosophers as F. H. Bradley.

Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Collection , Vol. IX, [ HC ], p. 473. For different types of knowledge see pp. 469–71.

Sri Aurobindo, Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education Collection , Vol. IX, [ HC ], p. 324; see also pp. 331–33.

Sri Aurobindo, [ AICEC ] Vol. IX, The Human Cycle , p. 2.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , pp. 742–3.

Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine , p. 771.

Sri Aurobindo, [ AICEC ] Vol. IX. The Human Cycle , p. 21.

Sri Aurobindo, The Foundations of Indian Culture , New York, 1953, pp. 438–39; see also p. 440.

Speeches and Writings of Mahatma Gandhi , Madras Quoted from Selections From Gandhi by Nirmal Kumar Bose, Ahmedabad, 1968, pp. 157–58. All subsequent quotations, unless otherwise mentioned, are taken from this well-known book by Bose.

Young India , 4–11–1926, pp. 154–55.

From Yerveda Mandir , pp. 13–4.

Young India , 31–12–1931, p. 6; see also Collected Works , Vol. 21, pp. 472–78.

Harijan , 23–3–1940, p. 6; see also Young India , 4–12–1924, p. 25; see also, Collected Works , Vol. 29, p. 410–12.

Harijan , 10–2–1940, p. 256; see also, Collected Works , Vol. 22, pp. 194, 271.

Young India , 21–1–1926, Quoted from M. K. Gandhi, Hindu Dharma , Ahmedabad, 1958, p. 55; see also sections 2 and 9.

Swami Vivekananda, What Religion Is , John Yale (ed.), London, 1962 p. 10.

Radhakrishnan, The Hindu View of Life , London, 1962, p. 43; see also p. 58.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma, USA

William Horosz ( Professor of Philosophy ) ( Professor of Philosophy )

State University of New York, Brockport, New York, USA

Tad S. Clements ( Professor of Philosophy ) ( Professor of Philosophy )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1986 Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht

About this chapter

Chattopadhyaya, D.P. (1986). The Concepts of Man and Human Purpose in Contemporary Indian Thought. In: Horosz, W., Clements, T.S. (eds) Religion and Human Purpose. Studies in Philosophy and Religion, vol 6. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-3483-2_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-3483-2_11

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-010-8059-0

Online ISBN : 978-94-009-3483-2

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The concept of man; a study in comparative philosophy

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

74 Previews

4 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station13.cebu on March 19, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia and research. Understanding the nuances and significance of a concept paper is essential for any researcher aiming to lay a strong foundation for their investigation.

Table of Contents

What Is Concept Paper

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document which outlines the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal. It outlines the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project. It is usually two to three-page long overview of the proposal. However, they differ from both research proposal and original research paper in lacking a detailed plan and methodology for a specific study as in research proposal provides and exclusion of the findings and analysis of a completed research project as in an original research paper. A concept paper primarily focuses on introducing the basic idea, intended research question, and the framework that will guide the research.

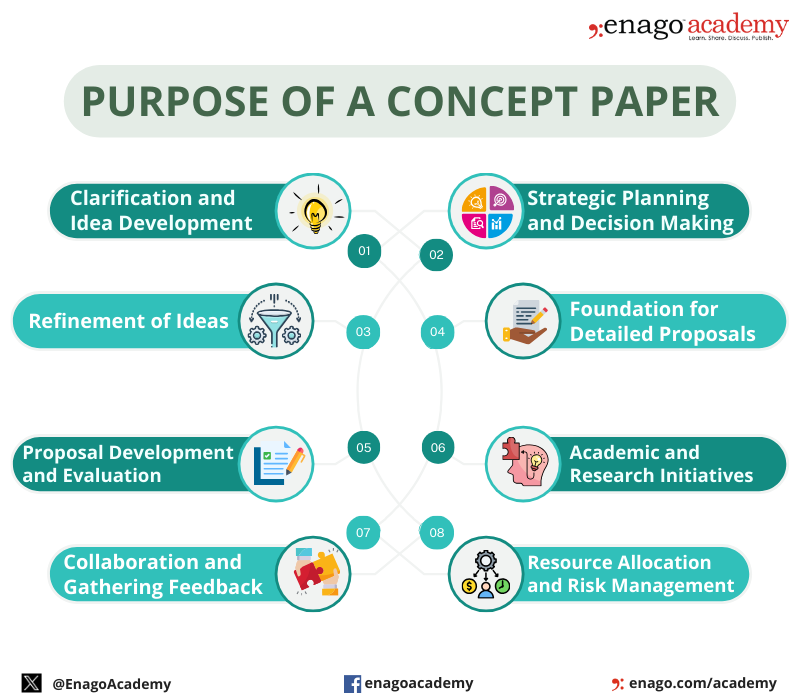

Purpose of a Concept Paper

A concept paper serves as an initial document, commonly required by private organizations before a formal proposal submission. It offers a preliminary overview of a project or research’s purpose, method, and implementation. It acts as a roadmap, providing clarity and coherence in research direction. Additionally, it also acts as a tool for receiving informal input. The paper is used for internal decision-making, seeking approval from the board, and securing commitment from partners. It promotes cohesive communication and serves as a professional and respectful tool in collaboration.

These papers aid in focusing on the core objectives, theoretical underpinnings, and potential methodology of the research, enabling researchers to gain initial feedback and refine their ideas before delving into detailed research.

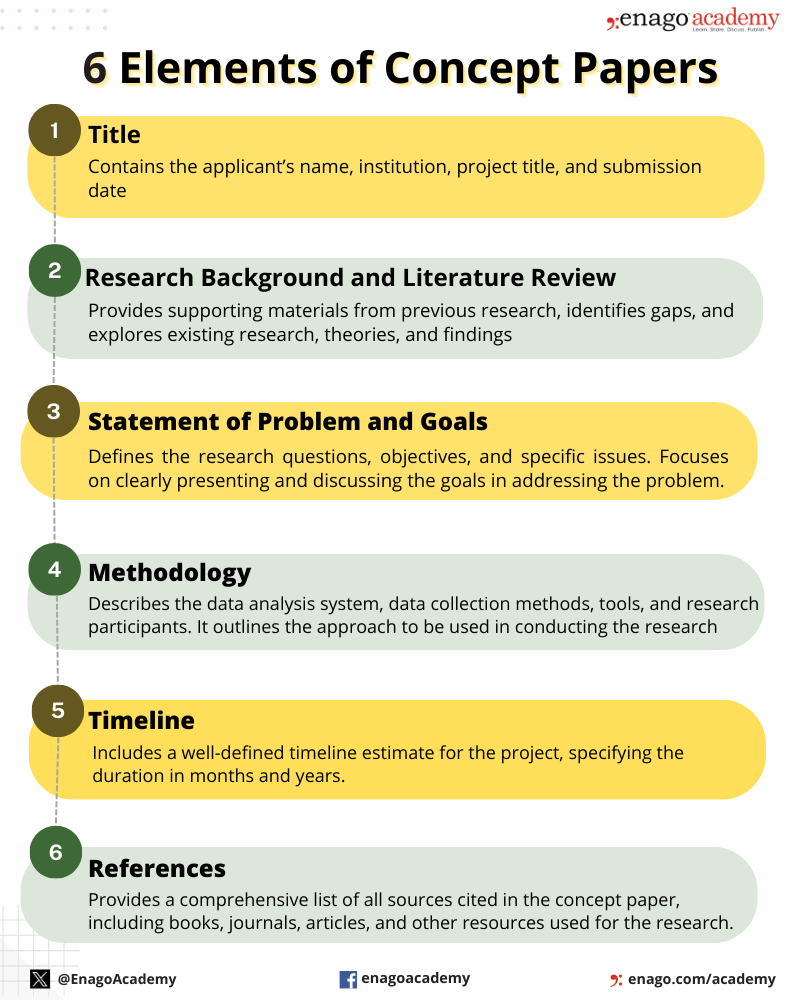

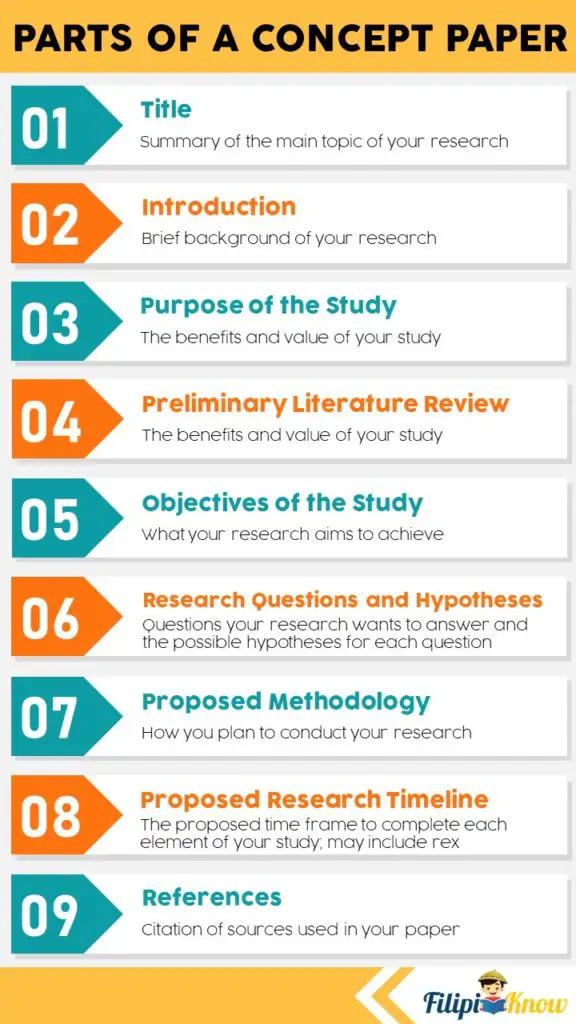

Key Elements of a Concept Paper

Key elements of a concept paper include the title page , background , literature review , problem statement , methodology, timeline, and references. It’s crucial for researchers seeking grants as it helps evaluators assess the relevance and feasibility of the proposed research.

Writing an effective concept paper in academic research involves understanding and incorporating essential elements:

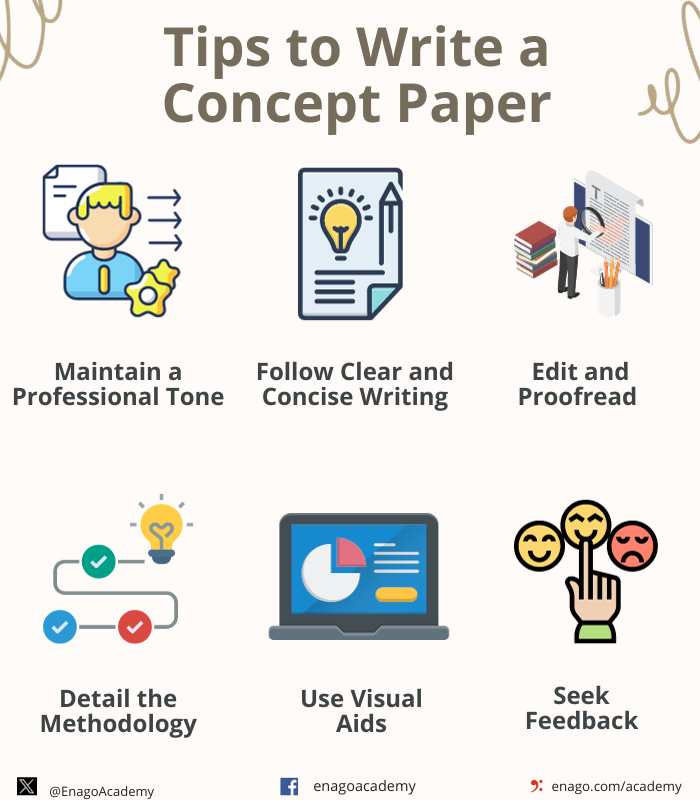

How to Write a Concept Paper?

To ensure an effective concept paper, it’s recommended to select a compelling research topic, pose numerous research questions and incorporate data and numbers to support the project’s rationale. The document must be concise (around five pages) after tailoring the content and following the formatting requirements. Additionally, infographics and scientific illustrations can enhance the document’s impact and engagement with the audience. The steps to write a concept paper are as follows:

1. Write a Crisp Title:

Choose a clear, descriptive title that encapsulates the main idea. The title should express the paper’s content. It should serve as a preview for the reader.

2. Provide a Background Information:

Give a background information about the issue or topic. Define the key terminologies or concepts. Review existing literature to identify the gaps your concept paper aims to fill.

3. Outline Contents in the Introduction:

Introduce the concept paper with a brief overview of the problem or idea you’re addressing. Explain its significance. Identify the specific knowledge gaps your research aims to address and mention any contradictory theories related to your research question.

4. Define a Mission Statement:

The mission statement follows a clear problem statement that defines the problem or concept that need to be addressed. Write a concise mission statement that engages your research purpose and explains why gaining the reader’s approval will benefit your field.

5. Explain the Research Aim and Objectives:

Explain why your research is important and the specific questions you aim to answer through your research. State the specific goals and objectives your concept intends to achieve. Provide a detailed explanation of your concept. What is it, how does it work, and what makes it unique?

6. Detail the Methodology:

Discuss the research methods you plan to use, such as surveys, experiments, case studies, interviews, and observations. Mention any ethical concerns related to your research.

7. Outline Proposed Methods and Potential Impact:

Provide detailed information on how you will conduct your research, including any specialized equipment or collaborations. Discuss the expected results or impacts of implementing the concept. Highlight the potential benefits, whether social, economic, or otherwise.

8. Mention the Feasibility

Discuss the resources necessary for the concept’s execution. Mention the expected duration of the research and specific milestones. Outline a proposed timeline for implementing the concept.

9. Include a Support Section:

Include a section that breaks down the project’s budget, explaining the overall cost and individual expenses to demonstrate how the allocated funds will be used.

10. Provide a Conclusion:

Summarize the key points and restate the importance of the concept. If necessary, include a call to action or next steps.

Although the structure and elements of a concept paper may vary depending on the specific requirements, you can tailor your document based on the guidelines or instructions you’ve been given.

Here are some tips to write a concept paper:

Example of a Concept Paper

Here is an example of a concept paper. Please note, this is a generalized example. Your concept paper should align with the specific requirements, guidelines, and objectives you aim to achieve in your proposal. Tailor it accordingly to the needs and context of the initiative you are proposing.

Download Now!

Importance of a Concept Paper

Concept papers serve various fields, influencing the direction and potential of research in science, social sciences, technology, and more. They contribute to the formulation of groundbreaking studies and novel ideas that can impact societal, economic, and academic spheres.

A concept paper serves several crucial purposes in various fields:

In summary, a well-crafted concept paper is essential in outlining a clear, concise, and structured framework for new ideas or proposals. It helps in assessing the feasibility, viability, and potential impact of the concept before investing significant resources into its implementation.

How well do you understand concept papers? Test your understanding now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Role of AI in Writing Concept Papers

The increasing use of AI, particularly generative models, has facilitated the writing process for concept papers. Responsible use involves leveraging AI to assist in ideation, organization, and language refinement while ensuring that the originality and ethical standards of research are maintained.

AI plays a significant role in aiding the creation and development of concept papers in several ways:

1. Idea Generation and Organization

AI tools can assist in brainstorming initial ideas for concept papers based on key concepts. They can help in organizing information, creating outlines, and structuring the content effectively.

2. Summarizing Research and Data Analysis

AI-powered tools can assist in conducting comprehensive literature reviews, helping writers to gather and synthesize relevant information. AI algorithms can process and analyze vast amounts of data, providing insights and statistics to support the concept presented in the paper.

3. Language and Style Enhancement

AI grammar checker tools can help writers by offering grammar, style, and tone suggestions, ensuring professionalism. It can also facilitate translation, in case a global collaboration.

4. Collaboration and Feedback

AI platforms offer collaborative features that enable multiple authors to work simultaneously on a concept paper, allowing for real-time contributions and edits.

5. Customization and Personalization

AI algorithms can provide personalized recommendations based on the specific requirements or context of the concept paper. They can assist in tailoring the concept paper according to the target audience or specific guidelines.

6. Automation and Efficiency

AI can automate certain tasks, such as citation formatting, bibliography creation, or reference checking, saving time for the writer.

7. Analytics and Prediction

AI models can predict potential outcomes or impacts based on the information provided, helping writers anticipate the possible consequences of the proposed concept.

8. Real-Time Assistance

AI-driven chat-bots can provide real-time support and answers to specific questions related to the concept paper writing process.

AI’s role in writing concept papers significantly streamlines the writing process, enhances the quality of the content, and provides valuable assistance in various stages of development, contributing to the overall effectiveness of the final document.

Concept papers serve as the stepping stone in the research journey, aiding in the crystallization of ideas and the formulation of robust research proposals. It the cornerstone for translating ideas into impactful realities. Their significance spans diverse domains, from academia to business, enabling stakeholders to evaluate, invest, and realize the potential of groundbreaking concepts.

Frequently Asked Questions

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document outlining the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal such as the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project.

A good concept paper should offer a clear and comprehensive overview of the proposed research. It should demonstrate a strong understanding of the subject matter and outline a structured plan for its execution.

Concept paper is important to develop and clarify ideas, develop and evaluate proposal, inviting collaboration and collecting feedback, presenting proposals for academic and research initiatives and allocating resources.

I got wonderful idea

It helps a lot for my concept paper.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

![concept of man research paper What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Need for Diversifying Academic Curricula: Embracing missing voices and marginalized perspectives

In classrooms worldwide, a single narrative often dominates, leaving many students feeling lost. These stories,…

- Career Corner

- Trending Now

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

How To Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research: An Ultimate Guide

A concept paper is one of the first steps in helping you fully realize your research project. Because of this, some schools opt to teach students how to write concept papers as early as high school. In college, professors sometimes require their students to submit concept papers before suggesting their research projects to serve as the foundations for their theses.

If you’re reading this right now, you’ve probably been assigned by your teacher or professor to write a concept paper. To help you get started, we’ve prepared a comprehensive guide on how to write a proper concept paper.

Related: How to Write Significance of the Study (with Examples)

Table of Contents

What is the concept paper, 1. academic research concept papers, 2. advertising concept papers, 3. research grant concept papers, concept paper vs. research proposal, tips for finding your research topic, 2. think of research questions that you want to answer in your project, 3. formulate your research hypothesis, 4. plan out how you will achieve, analyze, and present your data, 2. introduction, 3. purpose of the study, 4. preliminary literature review, 5. objectives of the study, 6. research questions and hypotheses, 7. proposed methodology, 8. proposed research timeline, 9. references, sample concept paper for research proposal (pdf), tips for writing your concept paper.

Generally, a concept paper is a summary of everything related to your proposed project or topic. A concept paper indicates what the project is all about, why it’s important, and how and when you plan to conduct your project.

Different Types of the Concept Paper and Their Uses

This type of concept paper is the most common type and the one most people are familiar with. Concept papers for academic research are used by students to provide an outline for their prospective research topics.

These concept papers are used to help students flesh out all the information and ideas related to their topic so that they may arrive at a more specific research hypothesis.

Since this is the most common type of concept paper, it will be the main focus of this article.

Advertising concept papers are usually written by the creative and concept teams in advertising and marketing agencies.

Through a concept paper, the foundation or theme for an advertising campaign or strategy is formed. The concept paper can also serve as a bulletin board for ideas that the creative and concept teams can add to or develop.

This type of concept paper usually discusses who the target audience of the campaign is, what approach of the campaign will be, how the campaign will be implemented, and the projected benefits and impact of the campaign to the company’s sales, consumer base, and other aspects of the company.

This type of concept paper is most common in the academe and business world. Alongside proving why your research project should be conducted, a research grant concept paper must also appeal to the company or funding agency on why they should be granted funds.

The paper should indicate a proposed timeline and budget for the entire project. It should also be able to persuade the company or funding agency on the benefits of your research project– whether it be an increase in sales or productivity or for the benefit of the general public.

It’s important to discuss the differences between the two because a lot of people often use these terms interchangeably.

A concept paper is one of the first steps in conducting a research project. It is during this process that ideas and relevant information to the research topic are gathered to produce the research hypothesis. Thus, a concept paper should always precede the research proposal.

A research proposal is a more in-depth outline of a more fleshed-out research project. This is the final step before a researcher can conduct their research project. Although both have similar elements and structures, a research proposal is more specific when it comes to how the entire research project will be conducted.

Getting Started on Your Concept Paper

1. find a research topic you are interested in.

When choosing a research topic, make sure that it is something you are passionate about or want to learn more about. If you are writing one for school, make sure it is still relevant to the subject of your class. Choosing a topic you aren’t invested in may cause you to lose interest in your project later on, which may lower the quality of the research you’ll produce.

A research project may last for months and even years, so it’s important that you will never lose interest in your topic.

- Look for inspiration everywhere. Take a walk outside, read books, or go on your computer. Look around you and try to brainstorm ideas about everything you see. Try to remember any questions you might have asked yourself before like why something is the way it is or why can’t this be done instead of that .

- Think big. If you’re having trouble thinking up a specific topic to base your research project on, choosing a broad topic and then working your way down should help.

- Is it achievable? A lot of students make the mistake of choosing a topic that is hard to achieve in terms of materials, data, and/or funding available. Before you decide on a research topic, make sure you consider these aspects. Doing so will save you time, money, and effort later on.

- Be as specific as can be. Another common mistake that students make is that they sometimes choose a research topic that is too broad. This results in extra effort and wasted time while conducting their research project. For example: Instead of “The Effects of Bananas on Hungry Monkeys” , you could specify it to “The Effects of Cavendish Bananas on Potassium-deficiency in Hungry Philippine Long-tailed Macaques in Palawan, Philippines”.

Now that you have a general idea of the topic of your research project, you now need to formulate research questions based on your project. These questions will serve as the basis for what your project aims to answer. Like your research topic, make sure these are specific and answerable.

Following the earlier example, possible research questions could be:

- Do Cavendish bananas produce more visible effects on K-deficiency than other bananas?

- How susceptible are Philippine long-tailed macaques to K-deficiency?

- What are the effects of K-deficiency in Philippine long-tailed macaques?

After formulating the research questions, you should also provide your hypothesis for each question. A research hypothesis is a tentative answer to the research problem. You must provide educated answers to the questions based on your existing knowledge of the topic before you conduct your research project.

After conducting research and collecting all of the data into the final research paper, you will then have to approve or disprove these hypotheses based on the outcome of the project.

Prepare a plan on how to acquire the data you will need for your research project. Take note of the different types of analysis you will need to perform on your data to get the desired results. Determine the nature of the relationship between different variables in your research.

Also, make sure that you are able to present your data in a clear and readable manner for those who will read your concept paper. You can achieve this by using tables, charts, graphs, and other visual aids.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Generalized Structure of a Concept Paper

Since concept papers are just summaries of your research project, they are usually short and no longer than 5 pages. However, for big research projects, concept papers can reach up to more than 20 pages.

Your teacher or professor may give you a certain format for your concept papers. Generally, most concept papers are double-spaced and are less than 500 words in length.

Even though there are different types of concept papers, we’ve provided you with a generalized structure that contains elements that can be found in any type of concept paper.

The title for your paper must be able to effectively summarize what your research is all about. Use simple words so that people who read the title of your research will know what it’s all about even without reading the entire paper.

The introduction should give the reader a brief background of the research topic and state the main objective that your project aims to achieve. This section should also include a short overview of the benefits of the research project to persuade the reader to acknowledge the need for the project.

The Purpose of the Study should be written in a way that convinces the reader of the need to address the existing problem or gap in knowledge that the research project aims to resolve. In this section, you have to go into more detail about the benefits and value of your project for the target audience/s.

This section features related studies and papers that will support your research topic. Use this section to analyze the results and methodologies of previous studies and address any gaps in knowledge or questions that your research project aims to answer. You may also use the data to assert the importance of conducting your research.

When choosing which papers and studies you should include in the Preliminary Literature Review, make sure to choose relevant and reliable sources. Reliable sources include academic journals, credible news outlets, government websites, and others. Also, take note of the authors for the papers as you will need to cite them in the References section.

Simply state the main objectives that your research is trying to achieve. The objectives should be able to indicate the direction of the study for both the reader and the researcher. As with other elements in the paper, the objectives should be specific and clearly defined.

Gather the research questions and equivalent research hypotheses you formulated in the earlier step and list them down in this section.

In this section, you should be able to guide the reader through the process of how you will conduct the research project. Make sure to state the purpose for each step of the process, as well as the type of data to be collected and the target population.

Depending on the nature of your research project, the length of the entire process can vary significantly. What’s important is that you are able to provide a reasonable and achievable timeline for your project.

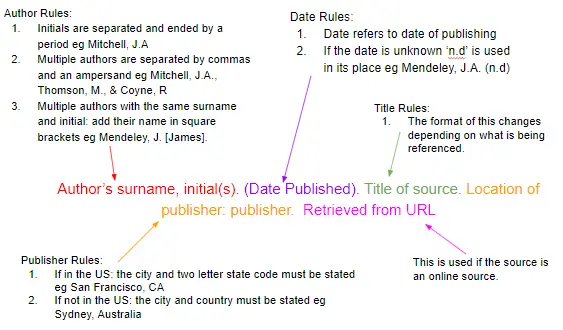

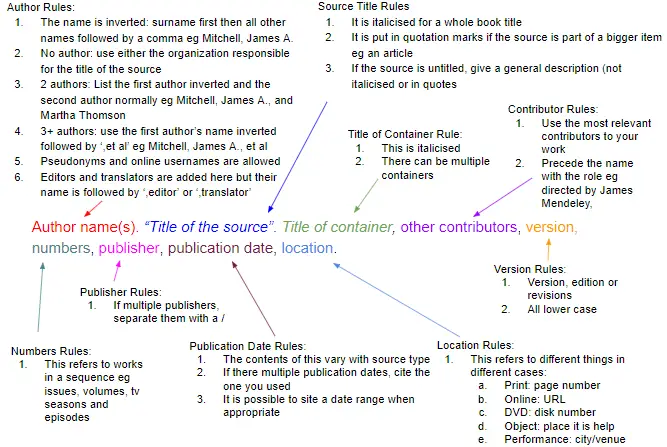

Make sure the time you will allot for each component of your research won’t be too excessive or too insufficient so that the quality of your research won’t suffer.