Differences between defamation, slander, and libel

Being wronged or misrepresented is never pleasant, but not all insults are created equally.

Find out more about more US law

by Brette Sember, J.D.

Brette is a former attorney and has been a writer and editor for more than 25 years. She is the author of more than 4...

Read more...

Updated on: February 3, 2023 · 4 min read

What is defamation?

Legal difference between opinion and defamation, what is the difference between slander and libel, damages for defamation, defending a defamation case.

Defamation, slander, and libel are terms that frequently confused with each other. They all fall into the same category of law and have to do with communications that falsely debase someone’s character.

Defamation is a false statement presented as a fact that causes injury or damage to the character of the person it is about. An example is “Tom Smith stole money from his employer.” If this is untrue and if making the statement damages Tom’s reputation or ability to work, it is defamation. The person whose reputation has been damaged by the false statement can bring a defamation lawsuit .

Defamation of character happens when something untrue and damaging is presented as a fact to someone else. Making the statement only to the person the statement is about (“Tom, you’re a thief”) is not defamation because it does not damage that person’s character in anyone else’s eyes.

There is an important difference in defamation law between stating an opinion and defaming someone. Saying, “I think Cindy is annoying” is an opinion and is something that can’t ever really be empirically proven true or false. Saying “I think Cindy stole a car” is still an opinion but implies she committed a crime. If the accusation is untrue, then it will defame her. This is why the news media is so careful to use the word “allegedly” when talking about people accused of a crime. This way they merely report someone else’s accusation without stating their own opinion.

A crucial part of a defamation case is that the person makes the false statement with a certain kind of intent.

The statement must have been made with knowledge that it was untrue or with reckless disregard for the truth (meaning the person who said it questioned the truthfulness but said it anyhow). If the person being defamed is a private citizen and not a celebrity or public figure, defamation can also be proven when the statement was made with negligence as to determining its truth (the person speaking should have known it was false or should have questioned it). This means it is easier to prove defamation when you are a private citizen. There is a higher standard required if you are a public figure.

Some states have laws that automatically make certain statements defamation. Any false statement that a person has committed a serious crime, has a serious infectious disease, or is incompetent in his profession are automatically defamatory under these laws.

Libel and slander are both types of defamation. Libel is an untrue defamatory statement that is made in writing. Slander is an untrue defamatory statement that is spoken orally. The difference between defamation and slander is that a defamatory statement can be made in any medium . It could be in a blog comment or spoken in a speech or said on television. Libelous acts only occur when a statement is made in writing (digital statements count as writing) and slanderous statements are only made orally.

You may have heard of seditious libel . The Sedition Act of 1798 made it a crime to print anything false about the government, president, or Congress. The Supreme Court later modified this when it enacted the rule that a statement against a public figure is libel only if it known to be false or the speaker had a reckless disregard for the truth when making it.

Suing for slander, libel, or defamation brings a civil suit in a state court and alleges that under the slander laws or libel laws of that state the person who brought about the lawsuit was damaged by the conduct of the person who made the false statement. A libel or slander lawsuit seeks monetary damages for harm caused by the statement, such as pain and suffering, damage to the plaintiff’s reputation, lost wages or a loss of ability to earn a living, and personal emotional reactions such as shame, humiliation, and anxiety.

If you are accused of defamation, slander, or libel, truth is an absolute defense to the allegation. If what you said is true, there is no case. If the case is brought by a public figure and you can prove you were only negligent in weighing whether the statement was false, that can be a defense as well.

Defamation is an area of law that protects people’s reputations by allowing them recourse if false statements are made about them. This type of civil case is an effective way to protect your reputation.

You may also like

Why do I need to conduct a trademark search?

By knowing what other trademarks are out there, you will understand if there is room for the mark that you want to protect. It is better to find out early, so you can find a mark that will be easier to protect.

October 4, 2023 · 4min read

How to write a will: A comprehensive guide to will writing

Writing a will is one of the most important things you can do for yourself and for your loved ones, and it can be done in just minutes. Are you ready to get started?

May 17, 2024 · 11min read

What is a power of attorney (POA)? A comprehensive guide

Setting up a power of attorney to make your decisions when you can't is a smart thing to do because you never know when you'll need help from someone you trust.

May 7, 2024 · 15min read

Definitions of Defamation of Character, Libel, and Slander

- U.S. Legal System

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

“Defamation of character” is a legal term referring to any false statement—called a “defamatory” statement—that harms another person’s reputation or causes them other demonstrable damages such as financial loss or emotional distress. Rather than a criminal offense, defamation is a civil wrong or “tort.” Victims of defamation can sue the person who made the defamatory statement for damages in civil court.

Statements of personal opinion are usually not considered to be defamatory unless they are phrased as being factual. For example, the statement, “I think Senator Smith takes bribes,” would probably be considered opinion, rather than defamation. However, the statement, “Senator Smith has taken many bribes,” if proven untrue, could be considered legally defamatory.

Libel vs. Slander

Civil law recognizes two types of defamation: “libel” and “slander.” Libel is defined as a defamatory statement that appears in written form. Slander is defined as a spoken or oral defamatory statement.

Many libelous statements appear as articles or comments on websites and blogs, or as comments in publicly-accessible chat rooms and forums. Libelous statements appear less often in letters to the editor sections of printed newspapers and magazines because their editors typically screen out such comments.

As spoken statements, slander can happen anywhere. However, to amount to slander, the statement must be made to a third party—someone other than the person being defamed. For example, if Joe tells Bill something false about Mary, Mary could sue Joe for defamation if she could prove that she had suffered actual damages as a result of Joe’s slanderous statement.

Because written defamatory statements remain publicly visible longer than spoken statements, most courts, juries, and attorneys consider libel to be more potentially harmful to the victim than slander. As a result, monetary awards and settlements in libel cases tend to be larger than those in slander cases.

While the line between opinion and defamation is fine and potentially dangerous, the courts are generally hesitant to punish every off-hand insult or slur made in the heat of an argument. Many such statements, while derogatory, are not necessarily defamatory. Under the law, the elements of defamation must be proven.

How Is Defamation Proven?

While the laws of defamation vary from state to state, there are commonly applied rules. To be found legally defamatory in court, a statement must be proven to have been all of the following:

- Published (made public): The statement must have been seen or heard by at least one other person than the person who wrote or said it.

- False: Unless a statement is false, it cannot be considered harmful. Thus, most statements of personal opinion do not constitute defamation unless they can objectively be proven false. For example, “This is the worst car I have ever driven,” cannot be proven to be false.

- Unprivileged: The courts have held that in some circumstances, false statements—even if injurious—are protected or “privileged,” meaning they cannot be considered legally defamatory. For example, witnesses who lie in court, while they can be prosecuted for the criminal offense of perjury, cannot be sued in civil court for defamation.

- Damaging or Injurious: The statement must have resulted in some demonstrable harm to the plaintiff. For example, the statement caused them to be fired, denied a loan, shunned by family or friends, or harassed by the media.

Lawyers generally consider showing actual harm to be the hardest part of proving defamation. Merely having the “potential” to cause harm is not enough. It must be proven that the false statement has ruined the victim’s reputation. Business owners, for example, must prove that the statement has caused them a substantial loss of revenue. Not only can actual damages be hard to prove, victims must wait until the statement has caused them problems before they can seek legal recourse. Merely feeling embarrassed by a false statement is rarely held to prove defamation.

However, the courts will sometimes automatically presume some types of especially devastating false statements to be defamatory. In general, any statement falsely accusing another person of committing a serious crime, if it was made maliciously or recklessly, may be presumed to constitute defamation.

Defamation and Freedom of the Press

In discussing defamation of character, it is important to remember that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects both freedom of speech and freedom of the press . Since in America the governed are assured the right to criticize the people who govern them, public officials are given the least protection from defamation.

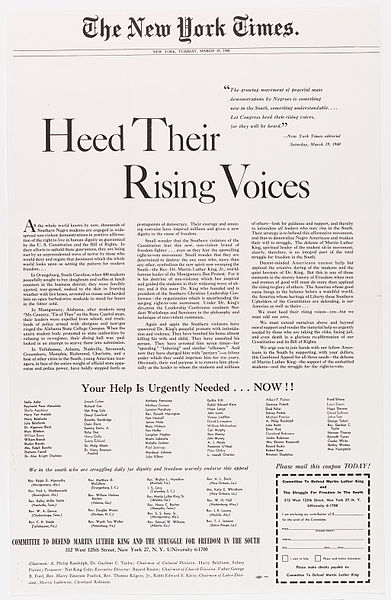

In the 1964 case of New York Times v. Sullivan , the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 9-0 that certain statements, while defamatory, are specifically protected by the First Amendment. The case concerned a full-page, paid advertisement published in The New York Times claiming that the arrest of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. by Montgomery City, Alabama, police on charges of perjury had been part of a campaign by city leaders to destroy Rev. King's efforts to integrate public facilities and increase the Black vote. Montgomery city commissioner L. B. Sullivan sued The Times for libel, claiming that the allegations in the ad against the Montgomery police had defamed him personally. Under Alabama state law, Sullivan was not required to prove he had been harmed, and since it was proven that the ad contained factual errors, Sullivan won a $500,000 judgment in state court. The Times appealed to the Supreme Court, claiming that it had been unaware of the errors in the ad and that the judgment had infringed on its First Amendment freedoms of speech and the press.

In its landmark decision better defining the scope of “freedom of the press,” the Supreme Court ruled that the publication of certain defamatory statements about the actions of public officials were protected by the First Amendment. The unanimous Court stressed the importance of “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” The Court further acknowledged that in public discussion about public figures like politicians, mistakes—if “honestly made”—should be protected from defamation claims.

Under the Court’s ruling, public officials can sue for defamation only if the false statements about them were made with “actual intent.” Actual intent means that the person who spoke or published the damaging statement either knew it was false or did not care whether it was true or not. For example, when a newspaper editor doubts the truth of a statement but publishes it without checking the facts.

American writers and publishers are also protected from libel judgments issued against them in foreign courts by the SPEECH Act signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010. Officially titled the Securing the Protection of our Enduring and Established Constitutional Heritage Act, the SPEECH act makes foreign libel judgments unenforceable in U.S. courts unless the laws of the foreign government provide at least as much protection of the freedom of speech as the U.S. First Amendment. In other words, unless the defendant would have been found guilty of libel even if the case had been tried in the United States, under U.S. law, the foreign court’s judgment would not be enforced in U.S. courts.

Finally, the “Fair Comment and Criticism” doctrine protects reporters and publishers from charges of defamation arising from articles such as movie and book reviews, and opinion-editorial columns.

Key Takeaways: Defamation of Character

- Defamation refers to any false statement that harms another person’s reputation or causes them other damages such as financial loss or emotional distress.

- Defamation is a civil wrong, rather than a criminal offense. Victims of defamation can sue for damages in civil court.

- There are two forms of defamation: “libel,” a damaging written false statement, and “slander,” a damaging spoken or oral false statement.

- “ Defamation FAQs .” Media Law Resource Center.

- “ Opinion and Fair Comment Privileges .” Digital Media Law Project.

- “ SPEECH Act .” U.S. Government Printing Office

- Franklin, Mark A. (1963). “ The Origins and Constitutionality of Limitations on Truth as a Defense in Tort Law .” Stanford Law Review

- “ Defamation .” Digital Media Law Project

- What Is Sedition? Definition and Examples

- Timeline of the Freedom of the Press in the United States

- The Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798

- Definition and Examples of Fraud

- Near v. Minnesota: Supreme Court Case, Arguments, Impact

- The Seventh Amendment: Text, Origins, and Meaning

- What Is Prior Restraint? Definition and Examples

- What Is Double Jeopardy? Legal Definition and Examples

- What Is Sovereign Immunity? Definition and Examples

- What Are Individual Rights? Definition and Examples

- Criminal Justice and Your Constitutional Rights

- What Is Civil Law? Definition and Examples

- Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940)

- 6 Major U.S. Supreme Court Hate Speech Cases

- Gitlow v. New York: Can States Prohibit Politically Threatening Speech?

- The 7 Most Liberal Supreme Court Justices in American History

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

US government and civics

Course: us government and civics > unit 3, freedom of speech: lesson overview.

- Freedom of speech

Cases to know

Key takeaways, review questions, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

The Difference Between 'Slander' and 'Libel'

The English language is heavy with synonyms, and we have a seemingly superfluous number of words for many specific things or qualities. Some of these excesses, such as the duplicates goatish and hircine , are the result of two separate parent languages; others, such as the hundreds of words we have for drunk , are best explained with a headshake and a shrug.

Though many people use 'slander' and 'libel' interchangeably, the words have distinct meanings—libel is written, while slander is spoken.

In many cases it makes no great difference whether one chooses a word or its synonym, except that some choices may be more elegant or appropriate for the linguistic register one is using (you might write "sorry I was so inebriated ," rather than "sorry I was so sozzled ," when writing a letter to your grandmother, for instance). In other cases, however, the wrong choice between two near-synonymous words may be important. Which brings us to libel and slander .

It should be noted that many people, especially when they are not writing a legal brief, or arguing in a court of law, do not distinguish between these two words, placing them both in the general semantic category of "saying or writing something untrue about someone, in order to make them look bad." However, there is a very clear difference between them.

Both libel and slander are forms of defamation , but libel is found in print, and slander is found in speech. Libel refers to a written or oral defamatory statement or representation that conveys an unjustly unfavorable impression, whereas slander refers to a false spoken statement that is made to cause people to have a bad opinion of someone. This explanation is refreshingly simple, but perhaps because it is so simple many people fail to observe the nuance. So we can make it a touch more complicated, and perhaps that will make it easier to remember.

It may help one to remember that libel is a written form of defamation if one understands that the word comes from the Latin libellus , which is the diminutive of liber , meaning "book." The earliest use of libel , in the 14th century, had the meaning of "a written declaration, bill, certificate, request, or supplication."

Slander , regrettably, does not have so informative an origin; it comes from the Latin scandalum ("stumbling block, offense"). If this etymological guide isn't complicated enough to help you remember the difference between these two words, we can always fall back on that old standby of making things even more unnecessarily complicated, and give additional guidance in the form of doggerel :

Although both of these words may betoken That adherence to truth has been broken, Remember this dictum, Should you find yourself victim, Libel is written, while slander is spoken.

Word of the Day

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

Commonly Confused

'canceled' or 'cancelled', 'virus' vs. 'bacteria', your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, is it 'jail' or 'prison', 'deduction' vs. 'induction' vs. 'abduction', grammar & usage, more words you always have to look up, 'fewer' and 'less', 7 pairs of commonly confused words, more commonly misspelled words, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, great big list of beautiful and useless words, vol. 4, 9 other words for beautiful, why jaywalking is called jaywalking, the words of the week - may 17, birds say the darndest things.

Skip to Main Content - Keyboard Accessible

Defamation and false statements: overview.

- U.S. Constitution Annotated

One of the most seminal shifts in constitutional jurisprudence occurred in 1964 with the Court’s decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan . 1 Footnote 376 U.S. 254 (1964) . The Times had published a paid advertisement by a civil rights organization criticizing the response of a Southern community to demonstrations led by Dr. Martin Luther King, and containing several factual errors. The plaintiff, a city commissioner in charge of the police department, claimed that the advertisement had libeled him even though he was not referred to by name or title and even though several of the incidents described had occurred prior to his assumption of office. Unanimously, the Court reversed the lower court’s judgment for the plaintiff. To the contention that the First Amendment did not protect libelous publications, the Court replied that constitutional scrutiny could not be foreclosed by the “label” attached to something. “Like . . . the various other formulae for the repression of expression that have been challenged in this Court, libel can claim no talismanic immunity from constitutional limitations. It must be measured by standards that satisfy the First Amendment .” 2 Footnote 376 U.S. at 269 . Justices Black, Douglas, and Goldberg, concurring, would have held libel laws per se unconstitutional. Id. at 293, 297 . “The general proposition,” the Court continued, “that freedom of expression upon public questions is secured by the First Amendment has long been settled by our decisions . . . . [W]e consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.” 3 Footnote 376 U.S. at 269, 270 . Because the advertisement was “an expression of grievance and protest on one of the major public issues of our time, [it] would seem clearly to qualify for the constitutional protection . . . [unless] it forfeits that protection by the falsity of some of its factual statements and by its alleged defamation of respondent.” 4 Footnote 376 U.S. at 271 .

Erroneous statement is protected, the Court asserted, there being no exception “for any test of truth.” Error is inevitable in any free debate and to place liability upon that score, and especially to place on the speaker the burden of proving truth, would introduce self-censorship and stifle the free expression which the First Amendment protects. 5 Footnote 376 U.S. at 271–72, 278–79 . Of course, the substantial truth of an utterance is ordinarily a defense to defamation. See Masson v. New Yorker Magazine, 501 U.S. 496, 516 (1991) . Nor would injury to official reputation afford a warrant for repressing otherwise free speech. Public officials are subject to public scrutiny and “[c]riticism of their official conduct does not lose its constitutional protection merely because it is effective criticism and hence diminishes their official reputation.” 6 Footnote 376 U.S. at 272–73 . That neither factual error nor defamatory content could penetrate the protective circle of the First Amendment was the “lesson” to be drawn from the great debate over the Sedition Act of 1798, which the Court reviewed in some detail to discern the “central meaning of the First Amendment .” 7 Footnote 376 U.S. at 273 . Thus, it appears, the libel law under consideration failed the test of constitutionality because of its kinship with seditious libel, which violated the “central meaning of the First Amendment .” “The constitutional guarantees require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” 8 Footnote 376 U.S. at 279–80 . The same standard applies for defamation contained in petitions to the government, the Court having rejected the argument that the petition clause requires absolute immunity. McDonald v. Smith, 472 U.S. 479 (1985) .

In the wake of the Times ruling, the Court decided two cases involving the type of criminal libel statute upon which Justice Frankfurter had relied in analogy to uphold the group libel law in Beauharnais . 9 Footnote Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250, 254–58 (1952) . In neither case did the Court apply the concept of Times to void them altogether. Garrison v. Louisiana 10 Footnote 379 U.S. 64 (1964) . held that a statute that did not incorporate the Times rule of “actual malice” was invalid, while in Ashton v. Kentucky 11 Footnote 384 U.S. 195 (1966) . a common-law definition of criminal libel as “any writing calculated to create disturbances of the peace, corrupt the public morals or lead to any act, which, when done, is indictable” was too vague to be constitutional.

The teaching of Times and the cases following it is that expression on matters of public interest is protected by the First Amendment . Within that area of protection is commentary about the public actions of individuals. The fact that expression contains falsehoods does not deprive it of protection, because otherwise such expression in the public interest would be deterred by monetary judgments and self-censorship imposed for fear of judgments. But, over the years, the Court has developed an increasingly complex set of standards governing who is protected to what degree with respect to which matters of public and private interest.

Individuals to whom the Times rule applies presented one of the first issues for determination. At times, the Court has keyed it to the importance of the position held. “There is, first, a strong interest in debate on public issues, and, second, a strong interest in debate about those persons who are in a position significantly to influence the resolution of those issues. Criticism of government is at the very center of the constitutionally protected area of free discussion. Criticism of those responsible for government operations must be free, lest criticism of government itself be penalized. It is clear, therefore, that the ‘public official’ designation applies at the very least to those among the hierarchy of government employees who have, or appear to the public to have, substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of governmental affairs.” 12 Footnote Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75, 85 (1966) . But this focus seems to have become diffused and the concept of “public official” has appeared to take on overtones of anyone holding public elective or appointive office. 13 Footnote See Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75 (1966) (supervisor of a county recreation area employed by and responsible to the county commissioners may be public official within Times rule); Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 (1964) (elected municipal judges); Henry v. Collins, 380 U.S. 356 (1965) (county attorney and chief of police); St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727 (1968) (deputy sheriff); Greenbelt Cooperative Pub. Ass’n v. Bresler, 398 U.S. 6 (1970) (state legislator who was major real estate developer in area); Time, Inc. v. Pape, 401 U.S. 279 (1971) (police captain). The categorization does not, however, include all government employees. Hutchinson v. Proxmire, 443 U.S. 111, 119 n.8 (1979) . Moreover, candidates for public office were subject to the Times rule and comment on their character or past conduct, public or private, insofar as it touches upon their fitness for office, is protected. 14 Footnote Monitor Patriot Co. v. Roy, 401 U.S. 265 (1971) ; Ocala Star-Banner Co. v. Damron, 401 U.S. 295 (1971) .

Thus, a wide range of reporting about both public officials and candidates is protected. Certainly, the conduct of official duties by public officials is subject to the widest scrutiny and criticism. 15 Footnote Rosenblatt v. Baer, 383 U.S. 75, 85 (1966) . But the Court has held as well that criticism that reflects generally upon an official’s integrity and honesty is protected. 16 Footnote Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 (1964) , involved charges that judges were inefficient, took excessive vacations, opposed official investigations of vice, and were possibly subject to “racketeer influences.” The Court rejected an attempted distinction that these criticisms were not of the manner in which the judges conducted their courts but were personal attacks upon their integrity and honesty. “Of course, any criticism of the manner in which a public official performs his duties will tend to affect his private, as well as his public, reputation. . . . The public-official rule protects the paramount public interest in a free flow of information to the people concerning public officials, their servants. To this end, anything which might touch on an official’s fitness for office is relevant. Few personal attributes are more germane to fitness for office than dishonesty, malfeasance, or improper motivation, even though these characteristics may also affect the official’s private character.” Id. at 76–77 . Candidates for public office, the Court has said, place their whole lives before the public, and it is difficult to see what criticisms could not be related to their fitness. 17 Footnote In Monitor Patriot Co. v. Roy, 401 U.S. 265, 274–75 (1971) , the Court said: “The principal activity of a candidate in our political system, his ‘office,’ so to speak, consists in putting before the voters every conceivable aspect of his public and private life that he thinks may lead the electorate to gain a good impression of him. A candidate who, for example, seeks to further his cause through the prominent display of his wife and children can hardly argue that his qualities as a husband or father remain of ‘purely private’ concern. And the candidate who vaunts his spotless record and sterling integrity cannot convincingly cry ‘Foul’ when an opponent or an industrious reporter attempts to demonstrate the contrary. . . . Given the realities of our political life, it is by no means easy to see what statements about a candidate might be altogether without relevance to his fitness for the office he seeks. The clash of reputations is the staple of election campaigns and damage to reputation is, of course, the essence of libel. But whether there remains some exiguous area of defamation against which a candidate may have full recourse is a question we need not decide in this case.”

For a time, the Court’s decisional process threatened to expand the Times privilege so as to obliterate the distinction between private and public figures. First, the Court created a subcategory of “public figure,” which included those otherwise private individuals who have attained some prominence, either through their own efforts or because it was thrust upon them, with respect to a matter of public interest, or, in Chief Justice Warren’s words, those persons who are “intimately involved in the resolution of important public questions or, by reason of their fame, shape events in areas of concern to society at large.” 18 Footnote Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130, 164 (1967) (Chief Justice Warren concurring in the result). Curtis involved a college football coach, and Associated Press v. Walker , decided in the same opinion, involved a retired general active in certain political causes. The suits arose from reporting that alleged, respectively, the fixing of a football game and the leading of a violent crowd in opposition to enforcement of a desegregation decree. The Court was extremely divided, but the rule that emerged was largely the one developed in the Chief Justice’s opinion. Essentially, four Justices opposed application of the Times standard to “public figures,” although they would have imposed a lesser but constitutionally based burden on public figure plaintiffs. Id. at 133 (plurality opinion of Justices Harlan, Clark, Stewart, and Fortas). Three Justices applied Times , id. at 162 (Chief Justice Warren), and id. at 172 (Justices Brennan and White). Two Justices would have applied absolute immunity. Id. at 170 (Justices Black and Douglas). See also Greenbelt Cooperative Pub. Ass’n v. Bresler, 398 U.S. 6 (1970) . Later, the Court curtailed the definition of “public figure” by playing down the matter of public interest and emphasizing the voluntariness of the assumption of a role in public affairs that will make of one a “public figure.” 19 Footnote Public figures “[f]or the most part [are] those who . . . have assumed roles of especial prominence in the affairs of society. Some occupy positions of such persuasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes. More commonly, those classed as public figures have thrust themselves to the forefront of particular public controversies in order to influence the resolution of the issues involved.” Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 345 (1974) .

Second, in a fragmented ruling, the Court applied the Times standard to private citizens who had simply been involved in events of public interest, usually, though not invariably, not through their own choosing. 20 Footnote Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, 403 U.S. 29 (1971) . Rosenbloom had been prefigured by Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374 (1967) , a “false light” privacy case considered infra But, in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. 21 Footnote 418 U.S. 323 (1974) . the Court set off on a new path of limiting recovery for defamation by private persons. Henceforth, persons who are neither public officials nor public figures may recover for the publication of defamatory falsehoods so long as state defamation law establishes a standard higher than strict liability, such as negligence; damages may not be presumed, however, but must be proved, and punitive damages will be recoverable only upon the Times showing of “actual malice.”

The Court’s opinion by Justice Powell established competing constitutional considerations. On the one hand, imposition upon the press of liability for every misstatement would deter not only false speech but much truth as well; the possibility that the press might have to prove everything it prints would lead to self-censorship and the consequent deprivation of the public of access to information. On the other hand, there is a legitimate state interest in compensating individuals for the harm inflicted on them by defamatory falsehoods. An individual’s right to the protection of his own good name is, at bottom, but a reflection of our society’s concept of the worth of the individual. Therefore, an accommodation must be reached. The Times rule had been a proper accommodation when public officials or public figures were concerned, inasmuch as by their own efforts they had brought themselves into the public eye, had created a need in the public for information about them, and had at the same time attained an ability to counter defamatory falsehoods published about them. Private individuals are not in the same position and need greater protection. “We hold that, so long as they do not impose liability without fault, the States may define for themselves the appropriate standard of liability for a publisher or broadcaster of defamatory falsehood injurious to a private individual.” 22 Footnote 418 U.S. at 347 . Thus, some degree of fault must be shown.

Generally, juries may award substantial damages in tort for presumed injury to reputation merely upon a showing of publication. But this discretion of juries had the potential to inhibit the exercise of freedom of the press, and moreover permitted juries to penalize unpopular opinion through the awarding of damages. Therefore, defamation plaintiffs who do not prove actual malice—that is, knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth—will be limited to compensation for actual provable injuries, such as out-of-pocket loss, impairment of reputation and standing, personal humiliation, and mental anguish and suffering. A plaintiff who proves actual malice will be entitled as well to collect punitive damages. 23 Footnote 418 U.S. at 348–50 . Justice Brennan would have adhered to Rosenbloom , id. at 361 , while Justice White thought the Court went too far in constitutionalizing the law of defamation. Id. at 369 .

Subsequent cases have revealed a trend toward narrowing the scope of the “public figure” concept. A socially prominent litigant in a particularly messy divorce controversy was held not to be such a person, 24 Footnote Time, Inc. v. Firestone, 424 U.S. 448 (1976) . and a person convicted years before of contempt after failing to appear before a grand jury was similarly not a public figure even as to commentary with respect to his conviction. 25 Footnote Wolston v. Reader’s Digest Ass’n, 443 U.S. 157 (1979) . Also not a public figure for purposes of allegedly defamatory comment about the value of his research was a scientist who sought and received federal grants for research, the results of which were published in scientific journals. 26 Footnote Hutchinson v. Proxmire, 443 U.S. 111 (1979) . Public figures, the Court reiterated, are those who (1) occupy positions of such persuasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes or (2) have thrust themselves to the forefront of particular public controversies in order to influence the resolution of the issues involved, and are public figures with respect to comment on those issues. 27 Footnote 443 U.S. at 134 (quoting Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 345 (1974) ).

Commentary about matters of “public interest” when it defames someone is apparently, after Firestone 28 Footnote Time, Inc. v. Firestone, 424 U.S. 448, 454 (1976) . See also Wolston v. Reader’s Digest Ass’n, 443 U.S. 157 (1979) . and Gertz , to be protected to the degree that the person defamed is a public official or candidate for public office, public figure, or private figure. That there is a controversy, that there are matters that may be of “public interest,” is insufficient to make a private person a “public figure” for purposes of the standard of protection in defamation actions.

The Court has elaborated on the principles governing defamation actions brought by private figures. First, when a private plaintiff sues a media defendant for publication of information that is a matter of public concern—the Gertz situation, in other words—the burden is on the plaintiff to establish the falsity of the information. Thus, the Court held in Philadelphia Newspapers v. Hepps , 29 Footnote 475 U.S. 767 (1986) . the common law rule that defamatory statements are presumptively false must give way to the First Amendment interest that true speech on matters of public concern not be inhibited. This means, as the dissenters pointed out, that a Gertz plaintiff must establish falsity in addition to establishing some degree of fault ( e.g. , negligence). 30 Footnote 475 U.S. at 780 (Stevens, J., dissenting). On the other hand, the Court held in Dun & Bradstreet v. Greenmoss Builders that the Gertz standard limiting award of presumed and punitive damages applies only in cases involving matters of public concern, and that the sale of credit reporting information to subscribers is not such a matter of public concern. 31 Footnote 472 U.S. 749 (1985) . Justice Powell wrote a plurality opinion joined by Justices Rehnquist and O’Connor, and Chief Justice Burger and Justice White, both of whom had dissented in Gertz , added brief concurring opinions agreeing that the Gertz standard should not apply to credit reporting. Justice Brennan, joined by Justices Marshall, Blackmun, and Stevens, dissented, arguing that Gertz had not been limited to matters of public concern, and should not be extended to do so. What significance, if any, is to be attributed to the fact that a media defendant rather than a private defendant has been sued is left unclear. The plurality in Dun & Bradstreet declined to follow the lower court’s rationale that Gertz protections are unavailable to nonmedia defendants, and a majority of Justices agreed on that point. 32 Footnote 472 U.S. at 753 (plurality); id. at 773 (Justice White); id. at 781–84 (dissent). In Philadelphia Newspapers , however, the Court expressly reserved the issue of “what standards would apply if the plaintiff sues a nonmedia defendant.” 33 Footnote 475 U.S. at 779 n.4 . Justice Brennan added a brief concurring opinion expressing his view that such a distinction is untenable. Id. at 780 .

Other issues besides who is covered by the Times privilege are of considerable importance. The use of the expression “actual malice” has been confusing in many respects, because it is in fact a concept distinct from the common law meaning of malice or the meanings common understanding might give to it. 34 Footnote See, e.g. , Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153, 199 (1979) (Justice Stewart dissenting). Constitutional “actual malice” means that the defamation was published with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false. 35 Footnote New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 280 (1964) ; Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 78 (1964) ; Cantrell v. Forest City Publishing Co., 419 U.S. 245, 251–52 (1974) . Reckless disregard is not simply negligent behavior, but publication with serious doubts as to the truth of what is uttered. 36 Footnote St. Amant v. Thompson, 390 U.S. 727, 730–33 (1968) ; Beckley Newspapers Corp. v. Hanks, 389 U.S. 81 (1967) . A finding of “highly unreasonable conduct constituting an extreme departure from the standards of investigation and reporting ordinarily adhered to by responsible publishers” is alone insufficient to establish actual malice. Harte-Hanks Communications v. Connaughton, 491 U.S. 657 (1989) (nonetheless upholding the lower court’s finding of actual malice based on the “entire record” ). A defamation plaintiff under the Times or Gertz standard has the burden of proving by “clear and convincing” evidence, not merely by the preponderance of evidence standard ordinarily borne in civil cases, that the defendant acted with knowledge of falsity or with reckless disregard. 37 Footnote Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 331–32 (1974) ; Beckley Newspapers Corp. v. Hanks, 389 U.S. 81, 83 (1967) . See New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 285–86 (1964) ( “convincing clarity” ). A corollary is that the issue on motion for summary judgment in a New York Times case is whether the evidence is such that a reasonable jury might find that actual malice has been shown with convincing clarity. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, 477 U.S. 242 (1986) . Moreover, the Court has held, a Gertz plaintiff has the burden of proving the actual falsity of the defamatory publication. 38 Footnote Philadelphia Newspapers v. Hepps, 475 U.S. 767 (1986) (leaving open the issue of what “quantity” or standard of proof must be met). A plaintiff suing the press 39 Footnote Because the defendants in these cases have typically been media defendants ( but see Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 (1964) ; Henry v. Collins, 380 U.S. 356 (1965) ), and because of the language in the Court’s opinions, some have argued that only media defendants are protected under the press clause and individuals and others are not protected by the speech clause in defamation actions. See discussion, supra , under “Freedom of Expression: Is There a Difference Between Speech and Press?” for defamation under the Times or Gertz standards is not limited to attempting to prove his case without resort to discovery of the defendant’s editorial processes in the establishment of “actual malice.” 40 Footnote Herbert v. Lando, 441 U.S. 153 (1979) . The state of mind of the defendant may be inquired into and the thoughts, opinions, and conclusions with respect to the material gathered and its review and handling are proper subjects of discovery. As with other areas of protection or qualified protection under the First Amendment (as well as some other constitutional provisions), appellate courts, and ultimately the Supreme Court, must independently review the findings below to ascertain that constitutional standards were met. 41 Footnote New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 284–86 (1964) . See, e.g. , NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886, 933–34 (1982) . Harte-Hanks Communications v. Connaughton, 491 U.S. 657, 688 (1989) ( “the reviewing court must consider the factual record in full” ); Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union of United States, 466 U.S. 485 (1984) (the “clearly erroneous” standard of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a) must be subordinated to this constitutional principle).

There had been some indications that statements of opinion, unlike assertions of fact, are absolutely protected, 42 Footnote See, e.g. , Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323, 339 (1974) ( “under the First Amendment there is no such thing as a false idea” ); Greenbelt Cooperative Publishing Ass’n v. Bresler, 398 U.S. 6 (1970) (holding protected the accurate reporting of a public meeting in which a particular position was characterized as “blackmail” ); Letter Carriers v. Austin, 418 U.S. 264 (1974) (holding protected a union newspaper’s use of epithet “scab” ). but the Court held in Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. 43 Footnote 497 U.S. 1 (1990) . that there is no constitutional distinction between fact and opinion, hence no “wholesale defamation exemption” for any statement that can be labeled “opinion.” 44 Footnote 497 U.S. at 18 . The issue instead is whether, regardless of the context in which a statement is uttered, it is sufficiently factual to be susceptible of being proved true or false. Thus, if statements of opinion may “reasonably be interpreted as stating actual facts about an individual,” 45 Footnote 497 U.S. at 20 . In Milkovich the Court held to be actionable assertions and implications in a newspaper sports column that a high school wrestling coach had committed perjury in testifying about a fight involving his team. then the truthfulness of the factual assertions may be tested in a defamation action. There are sufficient protections for free public discourse already available in defamation law, the Court concluded, without creating “an artificial dichotomy between ‘opinion’ and fact.” 46 Footnote 497 U.S. at 19 .

Substantial meaning is also the key to determining whether inexact quotations are defamatory. Journalistic conventions allow some alterations to correct grammar and syntax, but the Court in Masson v. New Yorker Magazine 47 Footnote 501 U.S. 496 (1991) . refused to draw a distinction on that narrow basis. Instead, “a deliberate alteration of words [in a quotation] does not equate with knowledge of falsity for purposes of [ New York Times ] unless the alteration results in a material change in the meaning conveyed by the statement.” 48 Footnote 501 U.S. at 517 .

False Statements

As defamatory false statements can lead to legal liability, so can false statements in other contexts run afoul of legal prohibitions. For instance, more than 100 federal criminal statutes punish false statements in areas of concern to federal courts or agencies, 49 Footnote United States v. Wells, 519 U.S. 482, 505–507, nn. 8–10 (1997) (Stevens, J., dissenting) (listing statute citations). and the Court has often noted the limited First Amendment value of such speech. 50 Footnote See, e.g. , Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell , 485 U.S. at 52 (1988) ( “False statements of fact are particularly valueless [because] they interfere with the truth-seeking function of the marketplace of ideas.” ); Virginia State Bd. of Pharmacy Virginia Citizens Consumer Council , 425 U.S. at 771 ( “Untruthful speech, commercial or otherwise, has never been protected for its own sake.” ). The Court, however, has declined to find that all false statements fall outside of First Amendment protection. In United States v. Alvarez , 51 Footnote 567 U.S. ___, No. 11-210, slip op. (2012) . the Court overturned the Stolen Valor Act of 2005, 52 Footnote 18 U.S.C. § 704 . which imposed criminal penalties for falsely representing oneself to have been awarded a military decoration or medal. In an opinion by Justice Kennedy, four Justices distinguished false statement statutes that threaten the integrity of governmental processes or that further criminal activity, and evaluated the Act under a strict scrutiny standard. 53 Footnote Alvarez , slip op. at 8-12 (Kenndy, J.). Justice Kennedy was joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor.

Noting that the Stolen Valor Act applied to false statements made “at any time, in any place, to any person,” 54 Footnote Alvarez , slip op. at 10 (Kennedy, J). Justice Kennedy was joined in his opinion by Chief Justice Roberts, and Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor. Justice Kennedy suggested that upholding this law would leave the government with the power to punish any false discourse without a clear limiting principle. Justice Breyer, in a separate opinion joined by Justice Kagan, concurred in judgment, but did so only after evaluating the prohibition under an intermediate scrutiny standard. While Justice Breyer was also concerned about the breadth of the act, his opinion went on to suggest that a similar statute, more finely tailored to situations where a specific harm is likely to occur, could withstand legal challenge. 55 Footnote Alvarez , slip op. at 8–9 (Breyer, J).

The following state regulations pages link to this page.

- US Constitution

- Supreme Court Cases

- Chief Supreme Court Justices

- Current Supreme Court Justices

- Past US Supreme Court Justices

- Vice-Presidents

- Current Cases

- Historical Cases

- Impeachment

May 7, 2024 | Supreme Court Clarifies “Safety Valve” in Federal Criminal Sentencing Laws

United States Constitution

- Commerce Clause

- Dormant Commerce Clause

- Taxing and Spending Clause

- Necessary and Proper Clause

- Additional Enumerated Powers

- Judicial Review

- Impeachment of Federal Judges

- Justiciability

- Exceptions Clause

- Full Faith and Credit Clause

- Privileges and Immunities Clause

- Extradition Clause

- Fugitive Slave Clause

- New States and Other Property

- Guarantee Clause

- Establishment

- Free Exercise

- Freedom of Speech

- Freedom of the Press

- Assembly and Petition

- Freedom of Religion

- Amendment II

- Amendment III

- Amendment IV

- Rights of Criminal Defendants

- Eminent Domain

- Amendment VI

- Amendment VII

- Amendment VIII

- Amendment IX

- Amendment X

- Amendment XI

- Amendment XII

- Amendment XIII

- The Question of Government Action

- Birthright Citizenship

- Privileges or Immunities Clause

- Procedural Due Process

- Substantive Due Process

- Incorporation of the Bill of Rights

- Equal Protection Clause

- Amendment XV

- Amendment XVI

- Amendment XVII

- Amendment XVIII

- Amendment XIX

- Amendment XX

- Amendment XXI

- Amendment XXII

- Amendment XXIII

- Amendment XXIV

- Amendment XXV

- Amendment XXVI

- Amendment XXVII

First Amendment: Freedom of Speech & Freedom of the Press Defamation

- Actual Malice Standard

- Government Officials

- Public Figures

- SCOTUSJUSTICES

More Recent Posts

- Supreme Court Clarifies “Safety Valve” in Federal Criminal Sentencing Laws

- SCOTUS Issues Term’s First Decision – Finds ADA Case Moot

- Supreme Court Hears Oral Arguments in Three Cases

- Second Amendment Back at Supreme Court

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REPORTER RSS FEED

Managing Partner

Scarinci Hollenbeck

(201) 806-3364

© 2018 Scarinci Hollenbeck, LLC. All rights reserved.

Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Attorney Advertising

Digital Media Law Project

Legal resources for digital media, search form, what is a defamatory statement.

A defamatory statement is a false statement of fact that exposes a person to hatred, ridicule, or contempt, causes him to be shunned, or injures him in his business or trade. Statements that are merely offensive are not defamatory (e.g., a statement that Bill smells badly would not be sufficient (and would likely be an opinion anyway)). Courts generally examine the full context of a statement's publication when making this determination.

In rare cases, a plaintiff can be “libel-proof”, meaning he or she has a reputation so tarnished that it couldn’t be brought any lower, even by the publication of false statements of fact. In most jurisdictions, as a matter of law, a dead person has no legally-protected reputation and cannot be defamed.

Defamatory statements that disparage a company's goods or services are called trade libel. Trade libel protects property rights, not reputations. While you can't damage a company’s "reputation," you can damage the company by disparaging its goods or services.

Because a statement must be false to be defamatory, a statement of opinion cannot form the basis of a defamation claim because it cannot be proven true or false. For example, the statement that Bill is a short-tempered jerk, is clearly a statement of opinion because it cannot be proven to be true or false. Again, courts will look at the context of the statement as well as its substance to determine whether it is opinion or a factual assertion. Adding the words "in my opinion" generally will not be sufficient to transform a factual statement to a protected opinion. For example, there is no legal difference between the following two statements, both of which could be defamatory if false:

- "John stole $100 from the corner store last week."

- "In my opinion, John stole $100 from the corner store last week."

For more information on the difference between statements of fact and opinion, see the section on Opinion and Fair Comment Privileges .

Defamation Per Se

Some statements of fact are so egregious that they will always be considered defamatory. Such statements are typically referred to as defamation "per se." These types of statements are assumed to harm the plaintiff's reputation, without further need to prove that harm. Statements are defamatory per se where they falsely impute to the plaintiff one or more of the following things:

- a criminal offense;

- a loathsome disease;

- matter incompatible with his business, trade, profession, or office; or

- serious sexual misconduct.

See Restatement (2d) of Torts, §§ 570-574. Keep in mind that each state decides what is required to establish defamation and what defenses are available, so you should review your state's specific law in the State Law: Defamation section of this guide for more information.

It is important to remember that truth is an absolute defense to defamation, including per se defamation. If the statement is true, it cannot be defamatory. For more information see the section on Substantial Truth .

Subject Area:

- Request new password

Recent Blog Posts

- Seven Years of Serving and Studying the Legal Needs of Digital Journalism 9 years 2 months ago

- DMLP Announcement: A New Report on Media Credentialing in the United States 9 years 3 months ago

- Will E.U. Court's Privacy Ruling Break the Internet? 9 years 4 months ago

- Baidu's Political Censorship is Protected by First Amendment, but Raises Broader Issues 9 years 4 months ago

- Hear Ye, Hear Ye! Some Federal Courts Post Audio Recordings Online 9 years 4 months ago

- Service and Research at the Frontier of Media Law 9 years 5 months ago

- DMLP Announcement: Live Chat Session on Tax-Exempt Journalism (UPDATED) 9 years 5 months ago

- A New Approach to Helping Journalism Non-Profits at the IRS 9 years 5 months ago

We are looking for contributing authors with expertise in media law, intellectual property, First Amendment, and other related fields to join us as guest bloggers. If you are interested, please contact us for more details.

Most Viewed Guide Pages

- Recording Phone Calls and Conversations

- California Recording Law

- Using the Name or Likeness of Another

- State Law: Recording

- Linking to Copyrighted Materials

- New York Recording Law

- Texas Recording Law

Legal Aid at Work

Workplace Defamation

What is defamation.

Defamation occurs when one person publishes a false statement that tends to harm the reputation of another person. Written defamation is called libel . Spoken defamation is called slander .

How do I know if I’ve been defamed?

A person may be defamed by conduct and/or words. The conduct needs only to convey a defamatory message. For example, if a co-worker is removed from work premises by security personnel, this may create a false impression that the co-worker committed a crime.

What do I need to prove if I want to bring a claim of defamation?

A person must prove all of the following elements:

- defamatory content;

- publication;

- reference to plaintiff;

- intent; and

- harm or damages.

Is an opinion considered defamatory content?

No. A defamatory statement must be an assertion of fact, not an opinion. For example, if your boss says that you are not a very nice person, then that statement is likely to be an opinion. On the other hand, if your boss says you have been stealing from the company, that is a statement of fact, not opinion. The statement must also reasonably be understood as negative by the person who hears, sees or reads it.

What does it mean to say that the communication must be published?

Publication simply means that a statement is communicated to any person other than the person who is defamed. For example, publication may occur when a supervisor makes a false statement about an employee to another supervisor.

What type of harm must I establish for defamation?

You have to prove that you have been injured because of the communication. Because defamation involves injury to your reputation, you must show actual damage (e.g., that your reputation and esteem in the community has been injured as a result of the communication).

However, there are some statements that so obviously harmful that you do not have to prove actual damages. They are known as libel or slander per se . Among the categories of statements that constitute defamation (libel or slander) per se that are raised by employees are: statements that a person is unable or lacks integrity to carry out his/her office or employment; or statements that hurt the person in connection with his/her trade or profession.

Does my employer have any defenses?

Yes. There are four commonly recognized defenses to defamation. These include (1) privilege; (2) consent; (3) truth; and (4) opinion:

- Privilege: There are two types of privileges an employer may raise as a defense to defamation. An absolute privilege permits your employer to be completely absolved of liability even if the published statement is made with ill will toward you. Statements that are absolutely privileged include those raised during official proceedings (like a lawsuit), arbitration proceedings, or statements made during a legally required background check of a potential employee, or in any other governmental proceedings. A qualified privilege only protects your employer if the statement is made without “malice,” or ill will, toward you. Statements that are qualifiedly privileged include: evaluations or appraisals, investigative reports, references, counseling or warnings, grievance adjustment discussions, and discipline or discharge letters.

- Consent: If the employee gives the employer “consent” to make a statement, then the employer has an absolute privilege to make the statement.

- Truth: A truthful statement is a complete defense to defamation.

- Opinion: As noted above, an opinion , no matter how unfavorable, is not defamation. Courts use a variety of questions to determine whether a statement is an assertion of fact or opinion. Questions include whether the speaker included the words “I felt” or “I think” in his/her statement, to whom the statement was addressed, and the context or purpose of the communication.

If I think I have a defamation claim against my employer or a co-worker, what can I do?

First determine whether the employer is making a defamatory statement or expressing an opinion. Then determine whom the statement is made to. If the statement is made to a future potential employer, then it is more likely to constitute defamation.

Sometimes sending a letter to the former employer asking him to stop pursuant to California law is enough to resolve your problem. However, you may also file a complaint with the California Labor Commissioner or go directly to court. Individuals found guilty of defamation may be liable for “triple damages” under a California Labor Code section (1050) that was enacted to prevent employers from “blacklisting” former employees who are looking for new jobs.

Drake-Kendrick Lamar feud: What does the law say about defamatory lyrics?

PhD Candidate, Law, Western University

Disclosure statement

Lisa Macklem does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Western University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

Western University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

View all partners

The feud between rappers Drake and Kendrick Lamar reached a fever pitch recently, with both dissing each other in songs featuring harsh accusations . This kind of beef between rap artists isn’t new, but the severity of the insults traded in this feud has galvanized fans and the attention of the broader public.

In his lyrics, Lamar claimed Drake has an 11-year-old daughter that he abandoned and calls him a “ certified pedophile .” For his part, Drake called Lamar a “ pipsqueak ” and accused him of abusing his fianceé.

The salvos of diss tracks raise interesting questions about defamation in music lyrics. If either Drake or Lamar decided to sue the other for defamation, what would the law say?

Defamation includes both slander (verbal attacks) and libel (written attacks). Musical lyrics and audio recordings can qualify as libel . The standards for libel differ whether you are in Canada or the United States , so should one or the other decide to sue for libel, it would make a difference where they filed the lawsuit.

Freedom of speech

Libel requires that a derogatory statement is made that clearly refers to a person and that the statement is made to a third party. In this feud, there is no doubt about who is being accused of what, and the derogatory accusations are being communicated to millions, so technically, these lyrics look like libel.

Nonetheless, there are a number of defences available. A first response would be to claim a defence based on freedom of expression in Canada or First Amendment rights to free speech in the U.S .

Free speech rights in the U.S. have a longer reach than freedom of expression laws in Canada. Several cases in the U.S. have specifically cited artistic expression as protected speech.

California passed the Decriminalizing Artistic Expression Act in 2022. Nationally, the Restoring Artistic Protection Act (the RAP Act) is currently before the U.S. Congress. It aims to protect artists from having their words used against them in court.

The Canadian Supreme Court, in R v Simard , also rejected using lyrics as evidence . That case involved a criminal matter, and libel is a civil matter, but Drake and Lamar have accused each other of criminal activity.

Truth defence

Truth is the first defence available in a libel case. If Lamar or Drake have evidence that what they’ve said is substantially true, it is not defamation. In The Heart Part 6 , Drake says that Lamar should check his facts and claims that he’s actually fed Lamar false information about having a love child.

In 2005, one court in the U.S. ruled that rap lyrics were simply “rhetorical hyperbole” if they didn’t contain any verifiable true statements. Even if statements are false, if the defamed person can’t prove they suffered harm, there may be no damages.

Fair comment

The next possible defence would be fair comment, which leans into the importance of free speech. This applies to information with a strong public interest, and helps to defend news outlets when they publish something they believe to be true.

There is certainly an argument to be made that protecting young girls and all women from abuse is important to the public interests. The burden of proof lies with the defendant. The plaintiff only needs to prove the elements of libel.

A major difference between libel in the United States and Canada is that in the U.S. a public figure has to prove that the person acted with actual malice ; that is, that they intended to harm the other person.

That could potentially make a libel case easier for a plaintiff to win in Canada. However, Canadian courts, like U.S. ones, will focus on whether the statements were false and whether they caused harm.

Consent defence

The most applicable defence in this case would likely be consent, which leans into the long history of rap and diss tracks . Rap battles have been compared to boxing . When you step into a boxing ring, you consent to being punched. Similarly, when you step into a rap battle, you expect, and accept, that you will be dissed.

Eminem called Muhammad Ali an inspiration . Ali was known for delivering pre-fight rhyming disses of his opponents, and it’s easy to see a link between Ali’s single Round 5: Will the Real Sonny Liston Please Fall Down and Eminem’s lyric “ Will the real Slim Shady please stand up .”

Diss tracks are a great way for artists to garner attention . Drake and Lamar fans have been vocal in their opinions, and their songs have gone viral online. Both Lamar’s Euphoria and Drake’s Push Ups made the top 20 on Billboard’s Hot 100 . Overall, streams of Lamar’s back catalogue are up 49 per cent .

It’s been suggested that in meet the grahams , Lamar was intending for their exchanges to simply be an informal competition game . There is no shortage of artists in all genres taking aims at rivals or exes — just look at Taylor Swift’s latest offering .

It’s easy to see Drake and Lamar as consenting to this exchange in the tradition of diss tracks. In a high-profile jury trial, such as the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard case , it might come down to whoever the jury finds most sympathetic.

Regardless of how extreme this war of words has become, demonstrating actual harm due to the various allegations might prove difficult. However, the likelihood of this beef ever reaching the courts is low. Should Drake or Lamar decide to sue for defamation, it might be seen as admitting defeat in this artistic war of words. And so, it will likely remain up to the fans to decide who the winner of this rap beef is.

- Music industry

- Defamation law

- Kendrick Lamar

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Consider This from NPR

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

As antisemitism grows, it is easier to condemn than define

Kobie Talmoud, 16, left, a student at John F. Kennedy High School in Silver Spring, Md., speaks with Karla Silvestre, President of the Montgomery Count (Md.) Board of Education, after a congressional hearing on antisemitism in K-12 public schools. Jacquelyn Martin/AP hide caption

Kobie Talmoud, 16, left, a student at John F. Kennedy High School in Silver Spring, Md., speaks with Karla Silvestre, President of the Montgomery Count (Md.) Board of Education, after a congressional hearing on antisemitism in K-12 public schools.

To some, the marked rise of antisemitism in the U.S. over the last few years has been shocking.

But for journalist Julia Ioffe, it's been unsurprising, and a reminder of the long history of persecution of Jews around the world.

"We were second class citizens," Ioffe says, recalling her childhood in the Soviet Union.

"We were excluded from universities, from jobs, from overseas travel, where we were called names by our teachers and just random passersby on the street."

She says the relative safety of Jews in the U.S. over the last few generations has been an exception to the larger scope of history.

Franklin Foer of The Atlantic shares that sentiment. His latest piece is titled, " The Golden Age of American Jews is Ending ."

"Like many American Jews, I once considered antisemitism a threat largely emanating from the right," he wrote.

One of the most vivid examples was in 2017, when white supremacists marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, chanting, "Jews will not replace us." That year, Jewish cemeteries were vandalized. There were bomb threats against Jewish Community Centers.

Then, in 2018, a man walked into the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh during Shabbat services and killed 11 people.

"'In every generation, somebody rises up to kill us.' That's what we say in the Seder," Ioffe says.

That context helps explain why there is now so much debate over demonstrations in support of Palestinians – a debate over how to define antisemitism, and what to do about it.

You're reading the Consider This newsletter, which unpacks one major news story each day. Subscribe here to get it delivered to your inbox, and listen to more from the Consider This podcast .

Politics and antisemitism

Democrats and Republicans both say they want to fight antisemitism, but that might be where the agreement ends.

House Republicans have held hearings into antisemitism in schools, and the House voted on a bill that would adopt a legal definition of antisemitism to enforce civil rights laws at schools. President Biden also gave a major speech on the topic.

To Foer, the fact that politicians are even talking about antisemitism is important. "But on the other hand," he says, "it inevitably becomes a hugely polarized thing, and you have Republicans in Congress trying to score political points."

Large majorities of Americans say antisemitism is a serious problem

Ioffe similarly sees many of those efforts as disingenuous. She describes the political back and forth over antisemitism as "cynical opportunism."

"To me, one of the things that's...most dangerous for Jews is when we become a political football where both our needs, our safety, our humanness is completely erased," she says.

Anti-Zionism vs. antisemitism

Amid demonstrations in support of Palestinians, many are now grappling with the question of when, or if, anti-Zionism is antisemitic.

"You can absolutely be anti-Zionist without being antisemitic," Ioffe says. "One of the main ways that you do that is by being Jewish."

She says people who are rightly "incensed and horrified" by the humanitarian crisis in Gaza can have noble intentions, but blunder into antisemitic territory when talking about anti-Zionism.

"Then you get into questions of double standards," she says. "If the Palestinians have a right to national self-determination, do the Jews not have that? And if so, why not?"

Campus protests over the Gaza war

House passes bill aimed to combat antisemitism amid college unrest.

Foer agrees that it's complicated.

"There's a whole range of people who I know who are anti-Zionist," Foer says.

"[anti-Zionism is] not something I agree with...but I don't think that they are, per se, antisemites."

But there is a line. To Foer, when people use the word Zionist, it's often a synonym for Jew. "It becomes a way of expressing thoughts about Jewish villainy, about Jewish control, about a Jewish cabal that would be socially unacceptable," he says.

Listen to the full episode of Consider This, where host Ari Shapiro takes a close look at antisemitism with Julia Ioffe and Franklin Foer.

This episode was produced by Connor Donevan. It was edited by Courtney Dorning. Our executive producer is Sami Yenigun.

- antisemitism

Texas Senate panel holds hearing on DEI, antisemitism. What UT chancellor said of protests

University of Texas System Chancellor J.B. Milliken said elements of the pro-Palestinian protests over the past few weeks at UT were antisemitic in response to a question from the Texas Senate Higher Education Subcommittee, citing testimony from a Jewish UT student who spoke to the panel of his experience.

The subcommittee on Tuesday held hearings with university system chancellors over their institutions' compliance with Senate Bill 17, a state law that went into effect in January and bans public universities from having diversity, equity and inclusion offices or related functions, and the hearing also focused on antisemitism on campuses and free speech policies born from Senate Bill 18, a 2019 law that made public universities' outdoor spaces traditional public forums.

Outside of the chancellors and counsels, the committee had three invited panelists — a UT student, a UT professor specializing in the First Amendment and the policy director of the Anti-Defamation League — with the student and league speakers discussing increasing antisemitism and fear affecting Jewish students due to recent pro-Palestinian protests on college campuses. No pro-Palestinian representatives were included in the subcommittee's agenda.

Sen. Brandon Creighton, R-Conroe, the author of SB 17 and the subcommittee's chairman, asked Milliken and Texas A&M System Chancellor John Sharp, "If you both recognize, especially what happened on the UT campus and across the country, that these were anti-Jewish protests in their very nature?" referring to the pro-Palestinian demonstrations on campuses.

Milliken affirmed that elements of the protests were antisemitic, and said he'd agree that they were anti-Jewish.

“Not everybody involved is an antisemite and as you heard from the law professor, we value free speech, political speech, all of that," Milliken said. "It's when it crosses a line with threats, intimidation — creating an environment where students cannot pursue their education.”

Sharp said the protests at Texas A&M campuses have been less intense, but that he has no tolerance for antisemitism.

The protests at UT called on the university and the UT System to divest from Israeli weapons manufacturers. More than 130 people were arrested over two protests at UT — the first on April 24 and another on April 29 when demonstrators set up a surprise encampment that was quickly dismantled by police.

Antisemitism and campus free speech

UT sophomore Levi Fox testified to the panel about his experience with antisemitism on campus, including an encounter with a UT professor he said had approached him and verbally harassed him with an antisemitic threat.

"People ask how the Holocaust happened," Fox said. "Auschwitz wasn't built overnight. It was built as Jew hatred gradually became accepted and when society was desensitized to hate."

Fox said he knows people who have hidden their Judaism or are afraid of being seen going into Jewish spaces for fear of being targeted.

Courtney Toretto from the Anti-Defamation League said this year has had the greatest number of antisemitic incident reports since the group started collecting data decades ago. Toretto also spoke about the impact of chants like "From the river to the sea" and the "intifada," which she said call for the destruction of Jewish people in Israel.

"Many Jewish students report feeling isolated and targeted by these protests. While ADL vehemently supports the right to free speech and peaceful protest, we draw the line when conduct on campus crosses the line into harassment that threatens public safety and (students') well-being," Toretto said.

Fox told the American-Statesman after his testimony to the subcommittee that he is a staunch believer in free speech, and he hopes the Legislature guards free speech and protects Jewish students by encouraging more Holocaust education in schools. Asked when protests crossed the line, he said when there is violence and intimidation.

"There is no category of speech in United States law known as hate speech," Steven Collis, director of the Bech-Loughlin First Amendment Center and a professor at UT's Law School, told the subcommittee. But speech that incites violence or raises a "reasonable fear of imminent bodily harm" can be limited, he said.

Public universities are allowed to set reasonable restrictions and rules for protesting as long as they are implemented in a content-neutral way, he said.

"They try to conflate antisemitism with a student's right to protest and to free speech, which is wrong in and of itself," Rep. Ron Reynolds, D-Missouri City, told the Statesman after the Texas Legislative Black Caucus, which he chairs, held a news conference Tuesday over SB 17 and the right to protest.

Islamophobia was not mentioned as part of the subcommittee's agenda or at the panel. During the public testimony portion of the meeting Tuesday some speakers asked for there to be "equal protection of free speech."

SB 17 compliance, difficulties and successes

Milliken and Sharp asserted their commitments to following SB 17 exactly as written. But UT System's general counsel, Daniel Sharphorn, told the subcommittee that the system has struggled with the law's effects on grants.

"We've struggled mightily with how to handle the grants," Sharphorn said. "Part of it is talking to the granting agency to know what laws we're dealing with. ... Right now, I don't know that we've learned enough to know what the impact is going to be."

Brooks Moore, Texas A&M System's general counsel, said he thinks the accreditor's language is broad enough that he is not worried.