- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

Why Socialists Should Believe in Human Nature

- Back Issues

“Religion,” our new issue, is out now. Subscribe to our print edition today.

It's tempting to argue that "human nature" doesn't exist, but that's wrong. All people want freedom from abuse and exploitation and the ability to lead decent lives.

Gustave Deghilage / Flickr

Last year, Jacobin published The ABCs of Socialism , designed to answer the most common and most important questions about the history and practice of socialist ideas.

To coincide with our second printing of the book, Jacobin recently hosted a series of talks with ABCs contributors. You can buy a copy of the book for $5 here .

Here is an edited transcript of Adaner Usmani’ s remarks on whether human nature really exists and whether it is compatible with a socialist society. You can also listen to a podcast of his talk here .

Let’s set a scene. You’re with your extended family, and discussion meanders to an observation about you. Someone notes that, “Hey, on Facebook, it looks like you been going to protests — looks like you’ve been casting aspersions on capitalism, American imperialism, Ezra Klein. You’ve been using words like neoliberalism and reading Trotsky. It seems like you’re a socialist — maybe even be a commie?”

Someone at this gathering immediately responds to this revelation with disdain — maybe a cousin who overdosed on econ classes at college. This cousin turns to address you: “Socialism is all well and good on paper. Caring, sharing, all sounds great. But you’re preaching to the wrong species. Humans aren’t hippies. They’re selfish and care only about themselves — hence war, plunder, exploitation, violence. With the raw materials that are human beings, you’ll never build anything other than what we have today.”

When confronted with this objection, I’m guessing that most of us respond in roughly the same way — something like, “Look, cuz: the humans you know, they are monsters. Not only because you only hang out with douchebags, but also because you only know ‘capitalist man.’ Capitalist man sucks. But socialist man, on the other hand — he would be caring and compassionate.”

Finishing with a flourish, we’d probably say something like, “The bottom line is, there is no such thing as human nature .” Humans are made, they aren’t born.

In short, in response to the argument that humans are inherently competitive and selfish, you argued that in fact, there are no attributes or drives that adhere in humans. There is no such thing as a human nature. Let’s call this the “Blank Slate Thesis.”

The Blank Slate Thesis is wrong. It’s the wrong way to confront your cousin’s objection to socialism, and it’s the wrong way to defend the possibility of another type of society.

The Moral Problem

The Blank Slate Thesis leads socialists into three kinds of insoluble problems; three difficulties that reveal that most of us don’t even believe that there is no such thing as a human nature, even if we’ve made the opposite argument to stubborn cousins. There’s a moral difficulty, there’s an analytical difficulty, and there’s a political difficulty.

First, the moral difficulty. The thesis that humans have no inherent human nature makes our moral project incoherent.

By this, I mean one very simple thing. When you or I look at the world around us and find that something is amiss, that something immoral is afoot, we fixate on certain elemental forms of deprivation.

People are deprived of the basic things that they need in order to reproduce themselves comfortably. Many people in this world go to sleep hungry. They’re worried they may not survive their next pregnancy, their next illness, their next marriage. They’re worried that the oceans may rise to flood their home. They work meaningless jobs for petty tyrants. They can’t send their children to decent schools.

We agree that these things are terrible, they ought to be eliminated from our world. But you think these things are outrageous because you correctly believe that the people living in these conditions must themselves be outraged.

You believe that the average human being should not be forced to live impoverished, stunted lives because you impute to the average human being certain unshakeable interests — being fed when hungry, quenched when thirsty, free when dominated.

Consider the glorious socialist invocation, “Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains.” That’s a universal injunction. And why is that compelling? Because we all know that nobody likes being in chains.

The slogan is not, “Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains. Unless, in some cultures, people like being in chains, in which case, we demand that those people be allowed to keep their chains.”

This belief that these universal interests exist is rooted in a belief that humans universally are everywhere basically the same. You believe that people are meaningfully animated by their human nature whatever the influence of culture or history on them.

The Analytical Problem

So that’s the first point. Our moral projects are normative projects that require a commitment to some model of what human beings demand everywhere by virtue of their very nature.

Second, an analytical point. If humans were blank slates, it would be very difficult to make much sense of the laws of motion of human societies. It would lead to an analytical impasse.

As Vivek Chibber recently argued , socialists fixate on class because class analysis holds diagnostic and prognostic insight. Both of these claims are versions of a more general claim that socialists make about human history, which is referred to as “historical materialism.”

The claim is that given certain information about how the total pie in any given society is produced — about who does the producing, who does the appropriating, who owns, who rents, who works — we can make certain inferences about who has power and who is powerless, about who will do well for themselves and who will do poorly.

We can say something intelligent, in other words, about the rhythms of economic life in that society, about the character of political conflict that might emerge, and even about the nature of ideas or ideologies that agents in that society will find compelling.

What’s relevant for our purposes is that it is impossible to make this argument without being committed to some stable expectations about what humans are like across time and across space. At its essence, historical materialism is a set of claims about how an abstract human is likely to behave when she finds herself with or without certain resources and arrayed against other humans who are similarly or differently positioned.

If you take out the anchoring model of what humans are like in the abstract, if you reject any and all claims about human nature, the whole edifice comes crashing down. You lose the ability then to make sense of these core questions.

Anyone who wants to change society has to ask: why are some people poor? Why are other people rich? Why are some people powerful? Are other people powerless? How do we counter the power of the powerful? If you take out the anchoring model, human societies become nothing more than a blooming, buzzing, confusion of an infinite number of hierarchies, roles, ideas, beliefs, and rituals, etc.

People on the Left are very fond (and rightly so) of quoting thesis eleven from Marx’s “ Theses on Feuerbach ”: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it.” Thesis ten-and-three-quarters is definitely, “If you want to change the world, you have to make sense of it first.” The Blank Slate Thesis makes that impossible.

The Political Problem

So we’ve had a moral problem, and we’ve had an analytical problem. The third problem is a political problem: the Blank Slate Thesis leads to ruinous political analysis. It makes it very difficult for socialists to apprehend the tasks ahead of us in a non-socialist world. It leads to bad diagnoses and bad strategy.

What do I mean by this? Why would our position on human nature bear on our ability to win people to our politics? Let’s start with some sobering reminders first. We live in a society in which our politics are not mainstream.

It’s not a surprise. The enormous growth of socialist groups after Bernie Sanders, the widespread support for something like socialism among a younger generation at the polls — I don’t want to deny any of that.

But at the same time, we cannot forget that we’re still small, we’re still weak, and we’re still operating on the margins of this society.

When a small, weak, and marginal group looks out from its minoritarian vantage point onto society, there are two ways in which it tends to make sense of its own marginality. The first one is to believe that people aren’t signing up because they fail to see what we see. They don’t get it.

On the Left, enormous energy goes into these kinds of explanations. People aren’t with us because they aren’t woke. And why aren’t they woke? Because they’re bigoted, they’re stupid, they’re ignorant, they’re sexist, they’re racist, they’re nationalist, they’re xenophobes, and on and on.

That’s one way to make sense of why people don’t get it. And if I convince you of nothing else, please let me convince you that this is the wrong way.

The correct way, the better way, to make sense of our marginality is to invert this view — to flip it on its head entirely. We are few and they are not with us, not because they’ve failed to understand what we see, but because we’ve failed to understand what they have seen. We have failed to put ourselves in their shoes and take a walk through the world as they’ve experienced it.

What do I mean by this? Let’s take the enormous orange-haired elephant in the room . How are we to understand a white worker in West Virginia voting for a billionaire windbag? Or how 53 percent of white women could vote for the same man? Good answers to these sorts of political questions are distinguished from bad answers by one simple fact: they take seriously what it means to have lived the life of the person whose actions or beliefs you’re trying to explain.

In other words, a good political answer is one which puts you in the shoes of the person you’re trying to account for.

What does it mean to put yourself in their shoes? This is the critical point. It means remembering that a Trump voter is a human being animated by the same kinds of interests that animate you. She cares about her livelihood, her dignity, her autonomy, her family in much the same way that you do.

Your explanation and practice, in other words, should pass a simple litmus test: could it explain why I would have voted Trump, had I been born her?

If we fail to do this, we will find the tasks ahead of us impossible. Organizing is not really the task of preaching to the woke, but in large part, the task of awakening the not-yet-woke.

But if you can’t put yourself in their shoes, you will invariably find yourself talking down to them. Rather than meeting them where they are at, you will find yourself livid that they are not yet where you are. And that will lead to a lot of vigorous, condescending, and elitist finger-wagging.

So this is the third problem, the political problem: the Blank Slate Thesis encourages you to forget that people are always meaningfully animated by certain unshakeable concerns. If we’re going to win people to our side, we have to take these concerns seriously. We have to take their human nature seriously.

Human Nature in Capitalism

If you commit to the Blank Slate Thesis, as a socialist you face three kinds of problems. A moral problem, an analytical problem, and a political problem. So don’t do it. Don’t let your friends do it and don’t do it yourself.

But so far I haven’t made an argument on how to respond to our annoying cousin — just how not to respond. In fact, I’ve conceded that our cousin, our family free-marketeer, is right on two points. He’s right to argue that there’s a universal human nature, and he’s right to note that this means that people everywhere care about themselves and the interests of their loved ones.

Given these concessions to his argument, what distinguishes us as socialists from him? How should socialists respond? How do we defend the idea of a new society different from this one — a society in which people aren’t just out to maximize returns to themselves, a society which takes care of the weak, the vulnerable, the unfortunate?

To defend this vision against his, we have to make two clarifying arguments — one about this thing that we’re calling “human nature,” and one about how it expresses itself in social life.

The major mistake made by our family free-marketeer is that he paints a flat, simplistic portrait of what human nature entails. So of course he’s partly correct. Humans everywhere care about themselves. They care about having enough to eat, they want to be cared for when sick, they care about having a roof over our heads. We also care deeply about certain intangibles. Our autonomy, our dignity, and maybe even some unsavory things about ourselves — what people think of us, our standing in the eyes of our peers.

But our antagonist’s view of human nature is one in which we care only about these things, in which we only care about maximizing returns from the world to ourselves.

This is the bourgeois view. The abstract human is basically like a two-year-old on an airplane. Nobody else matters. And if this were true, our project would be doomed. Out of toddlers on an airplane, I think you’d probably be able to build a world of an Ayn Rand novel, but you wouldn’t be able to build socialism.

But the bourgeois view is only partly correct. Humans are capable of many things other than simple selfishness. We’re capable of caring for others, we’re capable of empathy and compassion, we have the capacity to distinguish fairness from unfairness, and the capacity to hold ourselves to those standards.

The bourgeois view inflates our selfish drives and ignores these other qualities. Socialists do not have to do the same. Human nature is not infinitely plastic. Its contain a variety of drives and capacities — some inner demons and some better angels, to quote Steven Pinker.

Here’s the second point. Notice what our antagonist’s argument entailed: that whatever the character of the society in which humans find themselves, their underlying selfishness, their underlying competitiveness, is going to eat away at social structures until those social structures have been rendered irrelevant or totally transformed. Biology overpowers society.

In response, it is tempting to argue that human nature does not matter at all. But this is wrong, for the three reasons already outlined. So what should we say, in response? We should argue that human nature is always relevant, but never decisive.

Think about the way in which society is organized. What do people have to do to reproduce themselves? What do they have to do to other people in order to reproduce themselves? These facts exercise selectional pressures on the set of drives that constitute our human nature. The socialist wager, in a sentence, is that a better society would encourage our better tendencies.

This is not to argue that the other aspects of our nature can ever be ignored. A better society will no doubt have to respect certain limits. It will have to satisfy our needs. It will have to grant us our desires for freedom, for autonomy, our need to be respected. Socialism will most definitely fail if it requires us to be altruistic or saints, because the vast majority of people are not built to be either of those things.

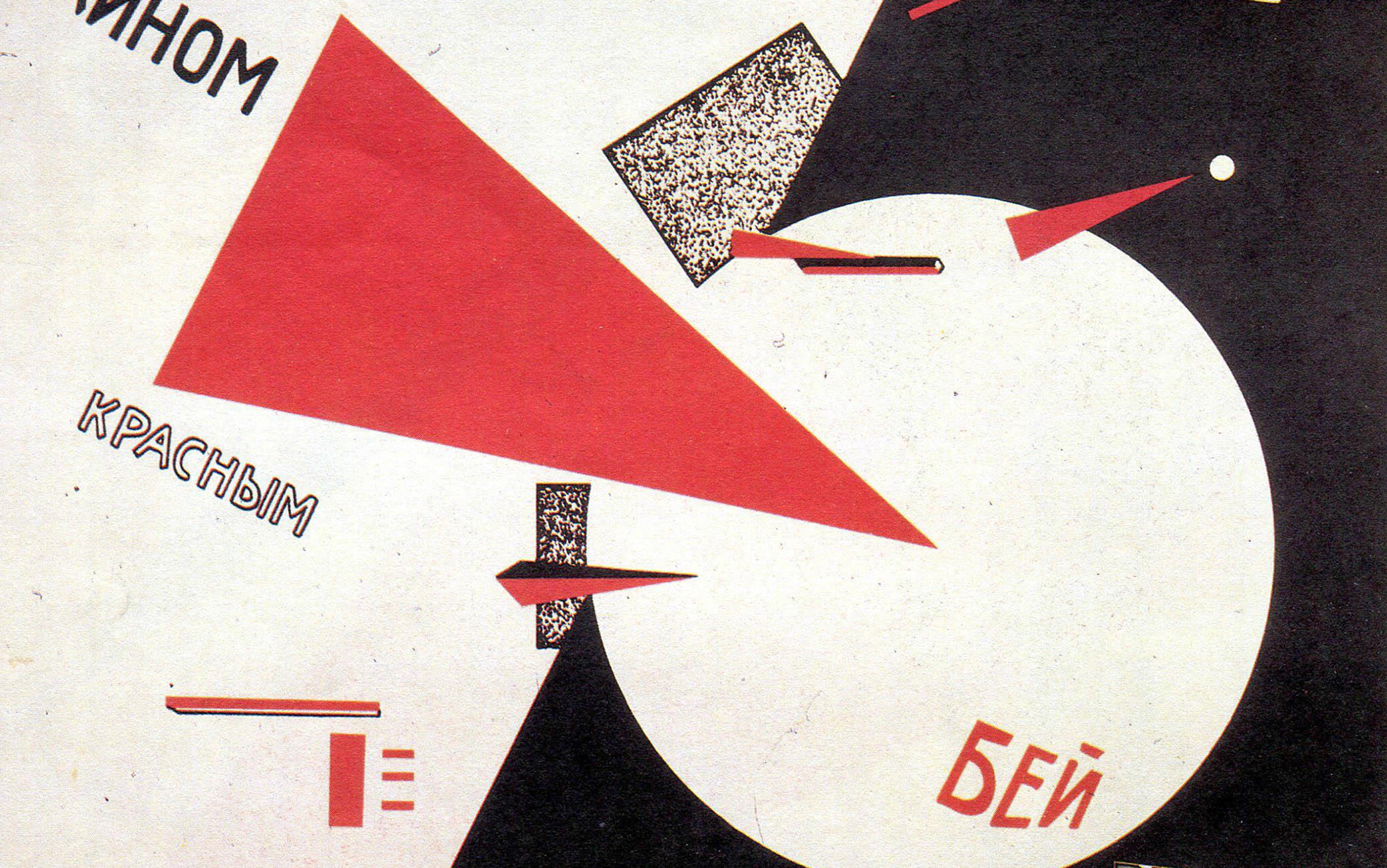

Whatever else socialism might mean, it cannot mean a society in which people are called upon to systemically sacrifice themselves for some ideal, be it the fatherland, the working class, the world revolution, the supreme leader. That road leads straight to Pyongyang.

However, a society which caters to everyone’s universal needs, which helps everyone flourish — this is a society that would encourage and nurture the good that lies inside all of us.

It is true in some important sense that our free-marketeer cousin knows only capitalist men and women. Socialist men and women would be different. They would still care about themselves and their needs, but a better society would also encourage them to take seriously the interests and needs of others.

Human Nature in Socialism

How would it do this? We can only speculate, of course. But I can think of two ways. First, a society which meets everyone’s needs is a society in which there would be less to quarrel about. Less reason for aggression, less reason for violence, less reason for predation. Compare the person you are when you’re sharing a box of cookies with your brother or sister, to the person you are when you’re sharing one cookie.

The second point is that socialism would also be a much more egalitarian society. People would be each other’s equals — not subordinates or superiors.

I’m sure many of you have heard of the Stanford prison experiment , which illustrated that hierarchies can make monsters out of ordinary humans. Well, the absence of these hierarchies should make it easier to bid farewell to the monsters inside us.

In a more developed, and more egalitarian society, better humans will flourish. Socialists one, libertarian cousin zero.

You have perhaps been tempted in the past to make the argument that there is no such thing as a human nature. That temptation is understandable — I’ve been there. But it’s wrong for three reasons: a moral reason, for an analytical reason, and for a political reason.

Socialists do believe — we must believe — that there is something called human nature. In fact, I believe that you believe it, whether or not you believe that you believe it. But we make two arguments that distinguish us from our bourgeois antagonists.

First, human nature comprises not just an interest in ourselves, but also compassion, empathy, capacity for reflection, capacity to be moral. And second, the way in which society is organized can amplify these drives and downplay others.

All this means that another world is definitely possible. Don’t let the fools get you down and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Politics news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Politics Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

- Study Notes

Common Humanity (Socialism)

Last updated 29 Jun 2020

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Socialism is built around the assumption that man is a social animal. As such, we seek to realise our goals on a collective basis and thereby co-operate with others to serve the common good .

The socialist stance on human nature differs sharply to all other ideologies. As previously mentioned, human nature can be improved by the overhaul or reform of capitalism. Our behaviour is moulded by societal forces (particularly the economic system) and capitalism cannot facilitate the best of human nature. It is therefore imperative that we replace an unethical, amoral and ‘dog eat dog’ system with a more socially equitable alternative. In doing so, socialism rejects the conservative argument that human nature is immutable and cannot be altered.

Socialism is built around the assumption that man is a social animal. As such, we seek to realise our goals on a collective basis and thereby co-operate with others to serve the common good . All socialists agree that industries should be owned or regulated by the state in order to serve the broader public interest. As such, the socialist position on the role of the state inevitably follows from their perspective on human nature and the importance of community.

Socialists also believe that each of us is of equal worth and opportunities should be spread as widely as possible. This may be achieved via an evolutionary style of politics or a full-blown revolution led by the disaffected. The dependent factor is the strand of socialism in question – an area considered in appropriate detail later. In addition, there is also no natural order or hierarchy. Inequality within a capitalist society is used to justify the way things are, but these are merely as transient as any other social construct. Socialists dare to dream of a better world based upon egalitarianism, fraternity and equality. This has long been part of its appeal and a source of criticism.

- Common humanity

You might also like

Our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800 Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

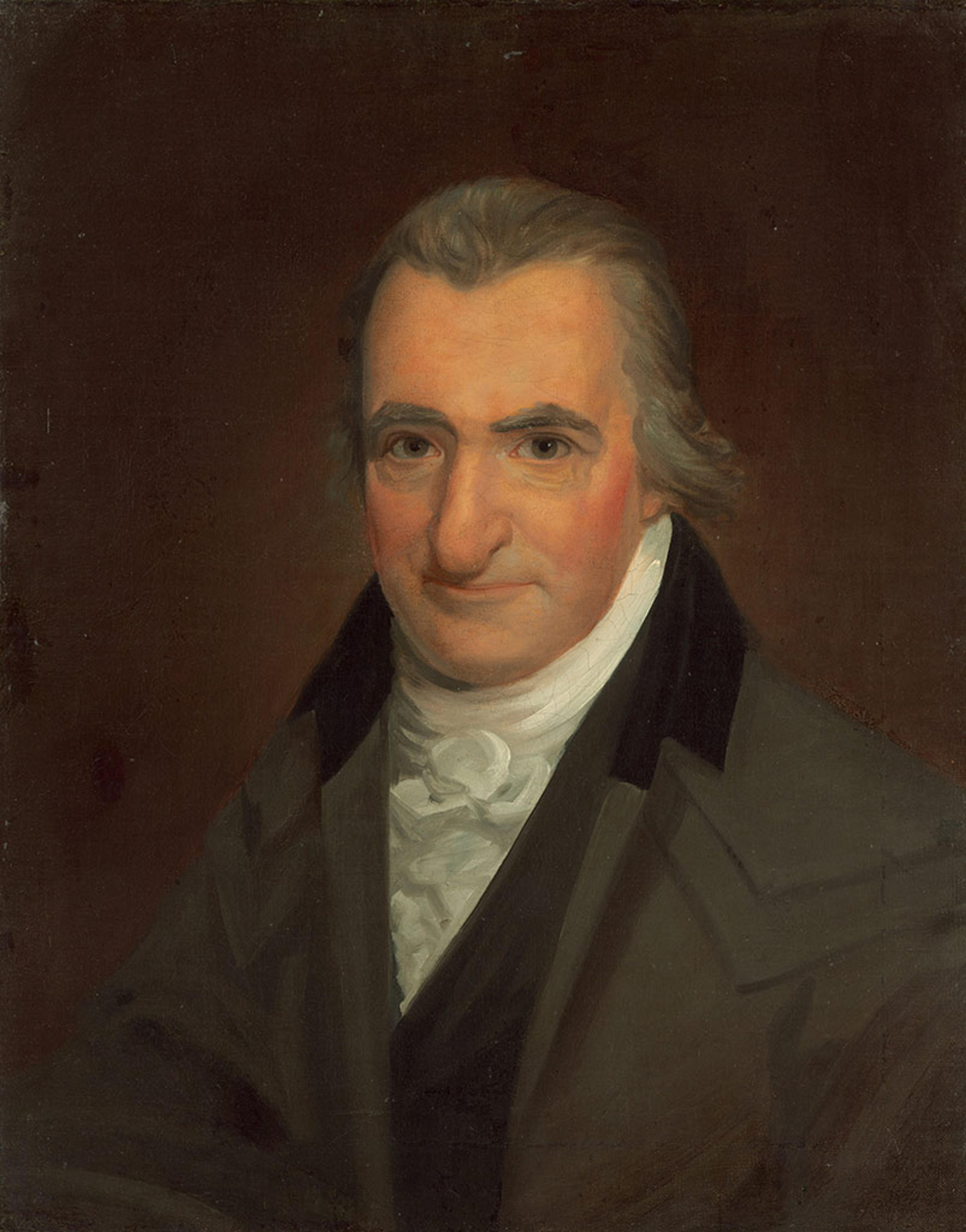

In this paper, two projects from different epochs will be analyzed to comprehend if there are some changes in the socialistic understanding of human nature. The work by Robert Owen, “Lectures on the Rational System of Society”, is written in the middle of the 19 th century. “Socialism and Human Nature” is created by Arnold Peterson in the middle of the 20 th century. Both authors succeed in presenting their own arguments about how they see socialism and what its impact on human nature is. The creation of a practical system in society helps to provide every human being with happiness through all succeeding generations (Owen 1841).

Owen (1841) underlines the necessity of change and the establishment of a new era and argues that human nature is a “compound of animal propensities, intellectual faculties, and moral qualities, or the germs of them” (p. 48). He tries to explain that one day a person can see how mistakenly the idea to respect human nature can be. At the same time, he offers to clarify what can make a person blind at the moment and introduces religion as one of those evils that confuse people and increase their miseries.

If Owen saw socialism as a kind of salvation for human nature and the possibility to promote a change that could make people happy, Peterson argues that socialism is incompatible with human nature (2005), it is against human nature, and people should realize that this beautiful dream cannot be taken for granted. Human despair is the reason why socialism has already gained so much power over people. People want to believe that they may control socialism as the ideology they have already established. Collective and governmental production can be used to meet the needs of people. However, people cannot be sure if they use the sources properly without hurting human nature.

Both authors create their works to demonstrate their attitudes to socialism and the importance of changes. Though the authors introduce different opinions, both of them help to realize that people cannot stop living in a mess they create day by day. Owen says that socialism is the answer to the question of how people can improve their lives, and Peterson wants to believe that socialism is the kind of hope people should be provided with. These two projects help to realize that socialist understanding of human nature has been changed considerably between the 19 th century and the present times because people start doubting the quality of socialism and its possible positive impact on human nature.

Devoted socialists believed that classless society could be happy and successful. The social vision of the chosen texts is the governmental control of all activities and decisions made. The government should help to eliminate the competitions that could take place between people and provide all people with the same opportunities. However, the works of Owen and Peterson show that different epochs have different understandings of human nature and its importance.

At the end of the 20 th century and even today, people continue living in an industrial society that requires the required forms of government and administration. At the same time, Peterson (2005) follows the idea that people should try to maintain freedom and order. People should never lose their hope to become better and satisfied with the conditions they have to live and work under “while a spark of the light of reason and of the flames of liberty still remain – while hearts still pulsate, and hands remain capable of grasping and holding aloft the torch of truth and freedom (Peterson 2005). Nowadays, many socialists view human nature as an economically dependent body that is in need of changes and improvements.

Still, Peterson, as well as many current representatives of socialism, believes that it is possible to provide every person with a national living wage, free higher education, and strong environmental and racial-justice policies (Purdy 2015). Peterson considers the opinions of different socialists and their opinions on how it is possible to keep human nature safe. He does not want to support either some radical changes or even gentle reforms.

His position seems like it is ok to continue keeping the status quo and discussing how the past and the present can be interrelated and influence the future. This project seems to be a logical interpretation of the ideas with the help of which the reader can understand that human nature serves as the best explanation of the majority of actions. If people make mistakes, they say that it is human nature to make mistakes. If a woman cannot achieve the required goal and protect her rights, she can say that it is her human nature.

Though Owen’s ideas do not actually contradict the opinion that is introduced by Peterson, it is possible to say the Owen is more confident in his words and suggestions. His intentions may be explained by the fact that he was a kind of socialist pioneer in Britain, and his experiments had to be confident and certain to attract the attention of other people (Simeon 2012). His idea that human nature is the combination of animal propensities seems to be a powerful contribution that makes people believe that it is not enough to keep the status quo or promotes some gentle reforms. Radical changes and the creation of a new society is the solution offered by Owen because humans nature is not fixed yet but malleable (Roberts & Sutch 2012).

People should not despair and continue changing something in their lives. As well as Peterson, Owen stays logic in his interpretations and underlines the power of thought and explanation in all ideas and suggestions.

Nowadays, many opinions about the role of socialist and the understandings of human nature are developed by the representatives of socialism. Sometimes, the association of socialism with social justice confuses people and makes them come to not always appropriate conclusions (Kabbany 2016). Peterson seems to be a more successful analyzer of socialism and its understandings of human nature. He considers the historical examples like slavery can prove that socialism is usually against human nature.

As for Owen, the Industrial Revolution can be used as the historical evidence of his ideas because it caused the development of divisions between people and the inabilities to comprehend what changes were really important. Owen tries to provide employees with equal rights and opportunities. His focus on human nature as something that can be changed in particular is powerful indeed. It is easy to find the successful implications of this argument, even in the work of Peterson.

Peterson is more convincing than Owen because he relies on his personal experience and finds support in the theories of Marx and Owen. He spreads a kind of new light on the socialist understanding of human nature, offers to combine hope and rationale to introduce human nature as the cooperation people can develop in order to survive, and proves that socialist understanding of human nature in the 20 th century differs considerably from the one given in the 19 th century because of the power of society on a person.

Reference List

Kabbany, J 2016, ‘ Socialism-loving professors and their ignorance ’, National Review . Web.

Owen, R 1841, Lectures on the rational system of society, derived solely from nature and experience , The Home Colonization Society, London.

Peterson, A 2005, Socialism and human nature . Web.

Purdy, J 2015, ‘ Bernie Sanders’s new deal socialism ’, The New Yorker . Web.

Roberts, P & Sutch, P 2012, An introduction to political thought: a conceptual toolkit , Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

Simeon, O 2012, ‘ Robert Owen: the father of British socialism? ’, Books and Ideas . Web.

- Research of Utopian Socialist Ideas

- Chicago Peterson Ave Stores: Company Information

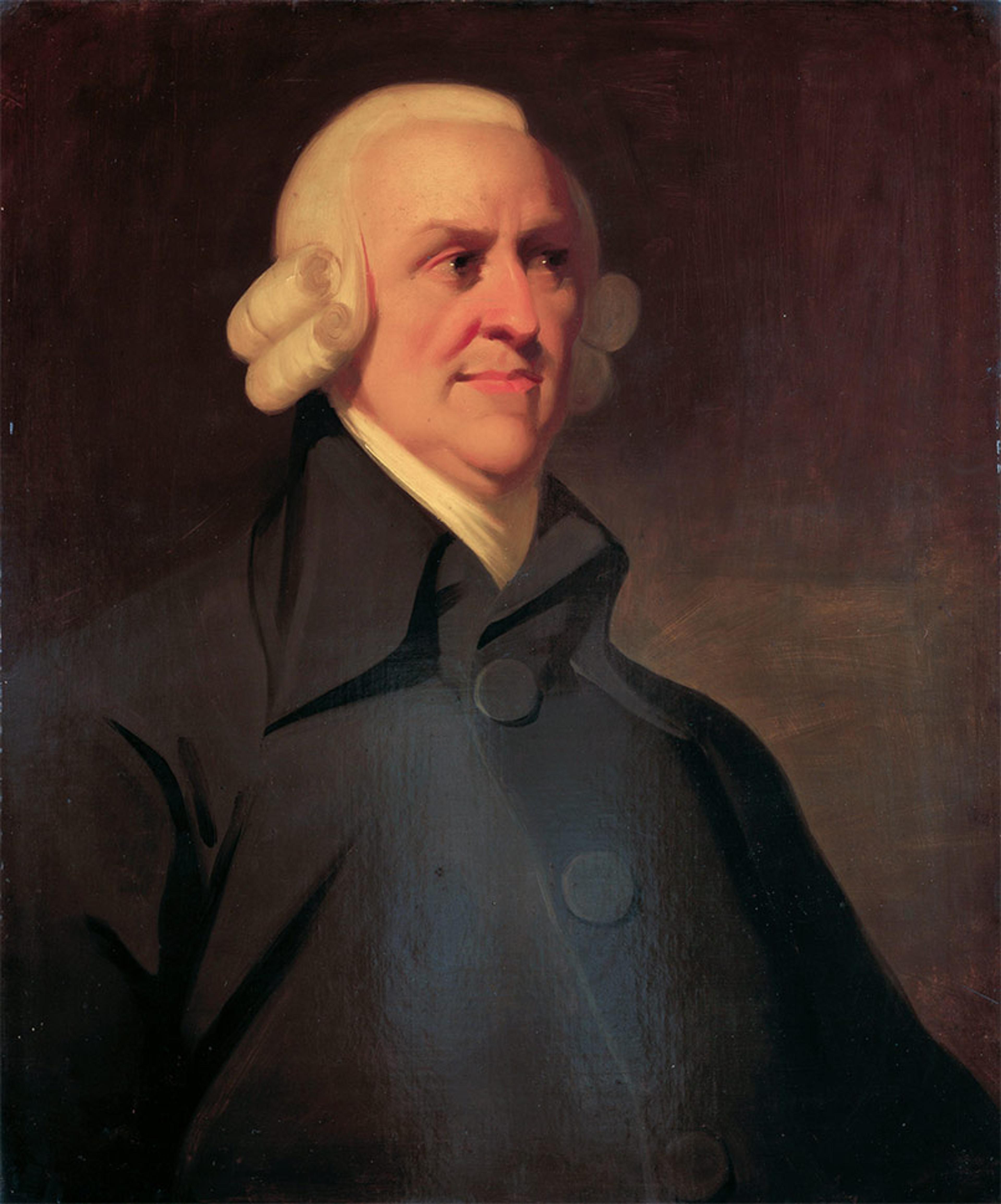

- Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and Robert Owen: Time Travel

- The Concept of Plato's Ideal State Essay

- "The Open Society and Its Enemies" by Karl Popper

- Politics and Power in "My Own Personal Idaho" Film

- Government's Role in "The Prince" by Machiavelli

- Platonic, Aristotelian, and Marxist Societies

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, September 8). Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800. https://ivypanda.com/essays/human-nature-in-socialist-view-since-1800/

"Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800." IvyPanda , 8 Sept. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/human-nature-in-socialist-view-since-1800/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800'. 8 September.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800." September 8, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/human-nature-in-socialist-view-since-1800/.

1. IvyPanda . "Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800." September 8, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/human-nature-in-socialist-view-since-1800/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Human Nature in Socialist View Since 1800." September 8, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/human-nature-in-socialist-view-since-1800/.

worldsocialism.org/spgb

Part of the World Socialist Movement

Human nature and Socialism

It seems that everyone is an expert on human nature, right? Especially politicians, who often make remarks about the general nature of humans. Why, everyone knows that humans are an inherently greedy, selfish, violent, nasty species. I mean, what could be more obvious?

This conventional wisdom is both wrong and unscientific. There has been a lot of debate over the years, for instance the Nature vs Nurture debate, but it seems that the public at large remain ill informed. The public’s judgement is of course affected by the unchallenged remarks of people in positions of power. We not only do ourselves a great injustice by condemning our fellow humans in this bigoted way. we also place ourselves and our collective future in great danger. That such views should be widespread amongst all sections of the population is a striking commentary on the education most people receive.

It is worth noting that when people make the scathing remarks concerning our nature they often conveniently exclude themselves and their friends. Actually, when most people talk about human nature, they are referring to human behaviour—two different concepts.

Human nature implies a built-in, inherent attribute, and we do have these. For instance, the urge to satisfy human needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. Human behaviour, on the other hand, includes learnt or acquired behaviour. The fact is that we are a social animal and that our behaviour is virtually all learned behaviour.

One to two million years ago, human beings emerged as a species from an ape like creature, and for at least the last 100,000 years we have had basically the same bodily form. The thing that ensured our survival was and is co-operation and this has been a constant indispensable feature of human society. Unlike other animals we long ago dispensed with adapting ourselves biologically to the environment, but instead we adapt the environment to ourselves. For hundreds of thousands of years we lived in primitive hunter-gatherer societies of tribal communities. One of the outstanding features of these communities was the ability of their members to co-operate and live in harmony for their own mutual benefit. If they had the behavioural attributes that we now so glibly condemn in ourselves, human beings would have perished forever millions of years ago.

The main things that people are born to do are to eat, drink, keep warm, imitate, copulate and learn. The relations they enter into with each other at a given time to accomplish these ends set the pattern for the social outlook and the social code. In the course of history humanity has moved from relative simplicity in the social arrangements in isolated communities into a world of large interconnected industrial ‘complexes. What people think and how they act is not due to some fundamental instinct, but is the result of customs, regulations and inhibitions that spring from the social environment in which people of past history have had to solve the problem of living. In other words, that people are able to think and act is a fact of biological and social development, but how they think and act is a result of social conditions. Since private property came into existence some 10,000 years ago. the pursuit of property has bred murder, cruelty, fraud, enmity and other anti-social behaviour.

There has been little discernible change in the fundamental make-up of humans, yet there have been considerable changes in social conditions. For example, stealing today is looked on as a criminal act whereas hunter-gatherer societies did not have any concept of stealing because there was no private property.

As to the assumption of selfishness, there are thousands of people who give selfless devotion in all manner of voluntary effort. There is co-operation going on all around us if you care to look, despite the competitive, one-upmanship, law-of-the-jungle philosophy which is rammed down our throats. It comes as a surprise that, despite the enormous inhuman stresses that are placed upon people by the society we live in, there are not more murders, rapes and crimes in general. The selfish, cruel, anti-social conduct that is laid at the door of human nature is really only the outcome of systems based on private property, which compel people to engage in predatory conduct in order to survive.

We cannot afford to let an erroneous view of ourselves as human beings prevail. There is absolutely no reason why we cannot live in peace and harmony. That this will mean that we must make a fundamental change in our system of society is something we will come to when we know about ourselves as humans.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Karl Marx (1818–1883) is often treated as a revolutionary, an activist rather than a philosopher, whose works inspired the foundation of many communist regimes in the twentieth century. It is certainly hard to find many thinkers who can be said to have had comparable influence in the creation of the modern world. However, Marx was trained as a philosopher, and although often portrayed as moving away from philosophy in his mid-twenties—perhaps towards history and the social sciences—there are many points of contact with modern philosophical debates throughout his writings.

The themes picked out here include Marx’s philosophical anthropology, his theory of history, his economic analysis, his critical engagement with contemporary capitalist society (raising issues about morality, ideology, and politics), and his prediction of a communist future.

Marx’s early writings are dominated by an understanding of alienation, a distinct type of social ill whose diagnosis looks to rest on a controversial account of human nature and its flourishing. He subsequently developed an influential theory of history—often called historical materialism—centred around the idea that forms of society rise and fall as they further and then impede the development of human productive power. Marx increasingly became preoccupied with an attempt to understand the contemporary capitalist mode of production, as driven by a remorseless pursuit of profit, whose origins are found in the extraction of surplus value from the exploited proletariat. The precise role of morality and moral criticism in Marx’s critique of contemporary capitalist society is much discussed, and there is no settled scholarly consensus on these issues. His understanding of morality may be related to his account of ideology, and his reflection on the extent to which certain widely-shared misunderstandings might help explain the stability of class-divided societies. In the context of his radical journalism, Marx also developed his controversial account of the character and role of the modern state, and more generally of the relation between political and economic life. Marx sees the historical process as proceeding through a series of modes of production, characterised by (more or less explicit) class struggle, and driving humankind towards communism. However, Marx is famously reluctant to say much about the detailed arrangements of the communist alternative that he sought to bring into being, arguing that it would arise through historical processes, and was not the realisation of a pre-determined plan or blueprint.

1.1 Early Years

1.3 brussels, 2.1 the basic idea, 2.2 religion and work, 2.3 alienation and capitalism, 2.4 political emancipation, 2.5 remaining questions, 3.1 sources, 3.2 early formulations, 3.3 1859 preface, 3.4 functional explanation, 3.5 rationality, 3.6 alternative interpretations, 4.1 reading capital, 4.2 labour theory of value, 4.3 exploitation, 5.1 unpacking issues, 5.2 the “injustice” of capitalism, 5.3 communism and “justice”, 6.1 a critical account, 6.2 ideology and stability, 6.3 characteristics, 7.1 the state in capitalist society, 7.2. the fate of the state in communist society, 8.1 utopian socialism, 8.2 marx’s utopophobia, 9. marx’s legacy, primary literature, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries, 1. life and writings.

Karl Marx was born in 1818, one of nine children. The family lived in the Rhineland region of Prussia, previously under French rule. Both of his parents came from Jewish families with distinguished rabbinical lineages. Marx’s father was a lawyer who converted to Christianity when it became necessary for him to do so if he was to continue his legal career.

Following an unexceptional school career, Marx studied law and philosophy at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. His doctoral thesis was in ancient philosophy, comparing the philosophies of nature of Democritus (c.460–370 BCE) and Epicurus (341–270 BCE). From early 1842, he embarked on a career as a radical journalist, contributing to, and then editing, the Rheinische Zeitung , until the paper was closed by the Prussian authorities in April 1843.

Marx married Jenny von Westphalen (1814–1881), his childhood sweetheart, in June 1843. They would spend their lives together and have seven children, of whom just three daughters—Jenny (1844–1883), Laura (1845–1911), and Eleanor (1855–1898)—survived to adulthood. Marx is also widely thought to have fathered a child—Frederick Demuth (1851–1929)—with Helene Demuth (1820–1890), housekeeper and friend of the Marx family.

Marx’s adult life combined independent scholarship, political activity, and financial insecurity, in fluctuating proportions. Political conditions were such, that, in order to associate and write as he wished, he had to live outside of Germany for most of this time. Marx spent three successive periods of exile in the capital cities of France, Belgium, and England.

Between late 1843 and early 1845, Marx lived in Paris, a cosmopolitan city full of émigrés and radical artisans. He was subsequently expelled by the French government following Prussian pressure. In his last months in Germany and during this Paris exile, Marx produced a series of “early writings”, many not intended for publication, which significantly altered interpretations of his thought when they were published collectively in the twentieth century. Papers that actually saw publication during this period include: “On the Jewish Question” (1843) in which Marx defends Jewish Emancipation against Bruno Bauer (1809–1882), but also emphasises the limitations of “political” as against “human” emancipation; and the “Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction” (1844) which contains a critical account of religion, together with some prescient remarks about the emancipatory potential of the proletariat. The most significant works that Marx wrote for self-clarification rather than publication in his Paris years are the so-called “1844 Manuscripts” (1844) which provide a suggestive account of alienation, especially of alienation in work; and the “Theses on Feuerbach” (1845), a set of epigrammatic but rich remarks including reflections on the nature of philosophy.

Between early 1845 and early 1848, Marx lived in Brussels, the capital of a rapidly industrialising Belgium. A condition of his residency was to refrain from publishing on contemporary politics, and he was eventually expelled after political demonstrations involving foreign nationals took place. In Brussels Marx published The Holy Family (1845), which includes contributions from his new friend and close collaborator Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), continuing the attack on Bruno Bauer and his followers. Marx also worked, with Engels, on a series of manuscripts now usually known as The German Ideology (1845–46), a substantial section of which criticises the work of Max Stirner (1806–1856). Marx also wrote and published The Poverty of Philosophy (1847) which disparages the social theory of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865). All these publications characteristically show Marx developing and promoting his own views through fierce critical attacks on contemporaries, often better-known and more established than himself.

Marx was politically active throughout his adult life, although the events of 1848—during which time he returned to Paris and Cologne—inspired the first of two periods of especially intense activity. Two important texts here are The Communist Manifesto (1848) which Marx and Engels published just before the February Revolution, and, following his move to London, The Class Struggles in France (1850) in which Marx examined the subsequent failure of 1848 in France. Between these two dates, Marx commented on, and intervened in, the revolution in Germany through the Neue Rheinische Zeitung (1848–49), the paper he helped to establish and edit in Cologne.

For well over half of his adult life—from late 1849 until his death in 1883—Marx lived in London, a city providing a secure haven for political exiles and a superb vantage point from which to study the world’s most advanced capitalist economy. This third and longest exile was dominated by an intellectual and personal struggle to complete his critique of political economy, but his theoretical output extended far beyond that project.

Marx’s initial attempt to make sense of Napoleon III’s rise to power in contemporary France is contained in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852). Between 1852 and 1862 Marx also wrote well over three hundred articles for the New York Daily Tribune ; sometimes unfairly disparaged as merely income-generating journalism, they frequently contain illuminating attempts to explain contemporary European society and politics (including European interventions in India and China) to an American audience (helpfully) presumed to know little about them.

The second of Marx’s two especially intense periods of political activity—after the revolutions of 1848—centred on his involvement in the International Working Men’s Association between 1864 and 1874, and the events of the Paris Commune (1871), in particular. The character and lessons of the Commune—the short-lived, and violently suppressed, municipal rebellion that controlled Paris for several months in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war—are discussed in The Civil War in France (1871). Also politically important was Marx’s “Critique of the Gotha Programme” (1875), in which he criticises the theoretical influence of Ferdinand Lassalle (1825–1864) on the German labour movement, and portrays the higher stage of a future communist society as endorsing distribution according to “the needs principle”.

Marx’s critique of political economy remains controversial. He never succeeded in fixing and realising the wider project that he envisaged. Volume One of Capital , published in 1867, was the only significant part of the project published in his own lifetime, and even here he was unable to resist heavily reworking subsequent editions (especially the French version of 1872–75). What we now know as Volume Two and Volume Three of Capital were put together from Marx’s raw materials by Engels and published in 1885 and 1894, respectively, and Marx’s own drafts were written before the publication of Volume One and barely touched by him in the remaining fifteen years of his life. An additional three supplementary volumes planned by Engels, and subsequently called Theories of Surplus Value (or, more colloquially, the “fourth volume of Capital ”) were assembled from remaining notes by Karl Kautsky (1854–1938), and published between 1905 and 1910. (The section of the “new MEGA”—see below—concerned with Capital -related texts contains fifteen thick volumes, and provides some sense of the extent and character of these later editorial interventions.) In addition, the publication in 1953—a previous two-volume edition (1939 and 1941) had only a highly restricted circulation—of the so-called Grundrisse (written in 1857–58) was also important. Whether this text is treated as a freestanding work or as a preparatory step towards Capital, it raises many questions about Marx’s method, his relation to G.W.F. Hegel (1770–1831), and the evolution of Marx’s thought. In contrast, the work of political economy that Marx did publish in this period— A Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy (1859)—was largely ignored by both contemporaries and later commentators, except for the, much reprinted and discussed, summary sketch of his theory of history that Marx offered in the so-called “1859 Preface” to that volume.

Marx’s later years (after the Paris Commune) are the subject of much interpretative disagreement. His inability to deliver the later volumes of Capital is often seen as emblematic of a wider and more systematic intellectual failure (Stedman Jones 2016). However, others have stressed Marx’s continued intellectual creativity in this period, as he variously rethought his views about: the core and periphery of the international economic system; the scope of his theory of history; social anthropology; and the economic and political evolution of Russia (Shanin 1983; K. Anderson 2010).

After the death of his wife, in 1881, Marx’s life was dominated by illness, and travel aimed at improving his health (convalescent destinations including the Isle of Wight, Karlsbad, Jersey, and Algiers). Marx died in March 1883, two months after the death of his eldest daughter. His estate was valued at £250.

Engels’s wider role in the evolution of, and, more especially the reception and interpretation of, Marx’s work is much disputed. The truth here is complex, and Engels is not always well-treated in the literature. Marx and Engels are sometimes portrayed as if they were a single entity, of one mind on all matters, whose individual views on any topic can be found simply by consulting the other. Others present Engels as the distorter and manipulator of Marx’s thought, responsible for any element of Marxian theory with which the relevant commentator might disagree. Despite their familiarity, neither caricature seems plausible or fair. The best-known jointly authored texts are The Holy Family , the “German Ideology” manuscripts, and The Communist Manifesto , but there are nearly two hundred shorter items that they both contributed to (Draper 1985: 2–19).

Many of Marx’s best-known writings remained unpublished before his death. The attempt to establish a reliable collected edition has proved lengthy and fraught. The authoritative Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe , the so-called “new MEGA” (1975–), is still a work in progress, begun under Soviet auspices but since 1990 under the guidance of the “International Marx-Engels Stiftung” (IMES). In its current form—much scaled-down from its original ambitions—the edition will contain some 114 volumes (well over a half of which are published at the time of writing). In addition to his various published and unpublished works, it includes Marx’s journalism, correspondence, drafts, and (some) notebooks. Texts are published in their original language (variously German, English, and French). For those needing to utilise English-language resources, the fifty volume Marx Engels Collected Works (1975–2004) can be recommended. (References to Marx and Engels quotations here are to these MECW volumes.) There are also several useful single volume selections of Marx and Engels writings in English (including Marx 2000).

2. Alienation and Human Flourishing

Alienation is a concept especially, but not uniquely, associated with Marx’s work, and the intellectual tradition that he helped found. It identifies a distinct kind of social ill, involving a separation between a subject and an object that properly belong together. The subject here is typically an individual or a group, while the object is usually an “entity” which variously is not itself a subject, is another subject(s), or is the original subject (that is, the relation here can be reflexive). And the relation between the relevant subject and object is one of problematic separation. Both elements of that characterisation are important. Not all social ills, of course, involve separations; for instance, being overly integrated into some object might be dysfunctional, but it is not characteristic of alienation. Moreover, not all separations are problematic, and accounts of alienation typically appeal to some baseline unity or harmony that is frustrated or violated by the separation in question.

Theories of alienation vary considerably, but frequently: first, identify a subset of these problematic separations as being of particular importance; second, include an account (sometimes implicit) of what makes the relevant separations problematic; and, third, propound some explanatory claims about the extent of, and prognosis for, alienation, so understood.

Marx’s ideas concerning alienation were greatly influenced by the critical writings on religion of Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872), and especially his The Essence of Christianity (1841). One key text in this respect is Marx’s “Contribution of Hegel’s Critique of Right: Introduction” (1843). This work is home to Marx’s notorious remark that religion is the “opium of the people,” a harmful, illusion-generating painkiller ( MECW 3: 175). It is here that Marx sets out his account of religion in most detail.

While traditional Christian theology asserts that God created man in God’s own image, Marx fully accepted Feuerbach’s inversion of this picture, proposing that human beings had invented God in their own image; indeed a view that long pre-dated Feuerbach. Feuerbach’s distinctive contribution was to argue that worshipping God diverted human beings from enjoying their own human powers. In their imagination humans raise their own powers to an infinite level and project them on to an abstract object. Hence religion is a form of alienation, for it separates human beings from their “species essence.” Marx accepted much of Feuerbach’s account but argues that Feuerbach failed to understand why people fall into religious alienation, and so is unable to explain how it can be transcended. Feuerbach’s view appears to be that belief in religion is purely an intellectual error and can be corrected by persuasion. Marx’s explanation is that religion is a response to alienation in material life, and therefore cannot be removed until human material life is emancipated, at which point religion will wither away.

Precisely what it is about material life that creates religion is not set out with complete clarity. However, it seems that at least two aspects of alienation are responsible. One is alienated labour, which will be explored shortly. A second is the need for human beings to assert their communal essence. Whether or not we explicitly recognise it, human beings exist as a community, and what makes human life possible is our mutual dependence on the vast network of social and economic relations which engulf us all, even though this is rarely acknowledged in our day-to-day life. Marx’s view appears to be that we must, somehow or other, acknowledge our communal existence in our institutions. At first it is “deviously acknowledged” by religion, which creates a false idea of a community in which we are all equal in the eyes of God. After the post-Reformation fragmentation of religion, where religion is no longer able to play the role even of a fake community of equals, the modern state fills this need by offering us the illusion of a community of citizens, all equal in the eyes of the law. Interestingly, the political or liberal state, which is needed to manage the politics of religious diversity, takes on the role offered by religion in earlier times of providing a form of illusory community. But the political state and religion will both be transcended when a genuine community of social and economic equals is created.

Although Marx was greatly inspired by thinking about religious alienation, much more of his attention was devoted to exploring alienation in work. In a much-discussed passage from the 1844 Manuscripts , Marx identifies four dimensions of alienated labour in contemporary capitalist society ( MECW 3: 270–282). First, immediate producers are separated from the product of their labour; they create a product that they neither own nor control, indeed, which comes to dominate them. (Note that this idea of “fetishism”—where human creations escape our control, achieve the appearance of independence, and come to oppress us—is not to be equated with alienation as such, but is rather one form that it can take.) Second, immediate producers are separated from their productive activity; in particular, they are forced to work in ways which are mentally and/or physically debilitating. Third, immediate producers are separated from other individuals; contemporary economic relations socialise individuals to view others as merely means to their own particular ends. Fourth, and finally, immediate producers are separated from their own human nature; for instance, the human capacities for community and for free, conscious, and creative, work, are both frustrated by contemporary capitalist relations.

Note that these claims about alienation are distinct from other, perhaps more familiar, complaints about work in capitalist society. For instance, alienated labour, as understood here, could be—even if it is often not—highly remunerated, limited in duration, and relatively secure.

Marx holds that work has the potential to be something creative and fulfilling. He consequently rejects the view of work as a necessary evil, denying that the negative character of work is part of our fate, a universal fact about the human condition that no amount of social change could remedy. Indeed, productive activity, on Marx’s account, is a central element in what it is to be a human being, and self-realisation through work is a vital component of human flourishing. That he thinks that work—in a different form of society—could be creative and fulfilling, perhaps explains the intensity and scale of Marx’s condemnation of contemporary economic arrangements and their transformation of workers into deformed and “dehumanised” beings ( MECW 3: 284).

It was suggested above that alienation consists of dysfunctional separations—separations between entities that properly belong together—and that theories of alienation typically presuppose some baseline condition whose frustration or violation by the relevant separation identifies the latter as dysfunctional. For Marx, that baseline seems to be provided by an account of human flourishing, which he conceptualises in terms of self-realisation (understood here as the development and deployment of our essential human capacities). Labour in capitalism, we can say, is alienated because it embodies separations preventing the self-realisation of producers; because it is organised in a way that frustrates the human need for free, conscious, and creative work.

So understood, and returning to the four separations said to characterise alienated labour, we can see that it is the implicit claim about human nature (the fourth separation) which identifies the other three separations as dysfunctional. If one subscribed to the same formal model of alienation and self-realisation, but held a different account of the substance of human nature, very different claims about work in capitalist society might result. Imagine a theorist who held that human beings were solitary, egoistic creatures, by nature. That theorist could accept that work in capitalist society encouraged isolation and selfishness, but deny that such results were alienating, because those results would not frustrate their baseline account of what it is to be a human being (indeed, they would rather facilitate those characteristics).

Marx seems to hold various views about the historical location and comparative extent of alienation. These include: that some systematic forms of alienation—presumably including religious alienation—existed in pre-capitalist societies; that systematic forms of alienation—including alienation in work—are only a feature of class divided societies; that systematic forms of alienation are greater in contemporary capitalist societies than in pre-capitalist societies; and that not all human societies are scarred by class division, in particular, that a future classless society (communism) will not contain systematic forms of alienation.

Marx maintains that alienation flows from capitalist social relations, and not from the kind of technological advances that capitalist society contains. His disapproval of capitalism is reserved for its social arrangements and not its material accomplishments. He had little time for what is sometimes called the “romantic critique of capitalism”, which sees industry and technology as the real villains, responsible for devastating the purportedly communitarian idyll of pre-capitalist relations. In contrast, Marx celebrates the bourgeoisie’s destruction of feudal relations, and sees technological growth and human liberation as (at least, in time) progressing hand-in-hand. Industry and technology are understood as part of the solution to, and not the source of, social problems.

There are many opportunities for scepticism here. In the present context, many struggle to see how the kind of large-scale industrial production that would presumably characterise communist society—communism purportedly being more productive than capitalism—would avoid alienation in work. Interesting responses to such concerns have been put forward, but they have typically come from commentators rather than from Marx himself (Kandiyali 2018). This is a point at which Marx’s self-denying ordinance concerning the detailed description of communist society prevents him from engaging directly with significant concerns about the direction of social change.

In the text “On The Jewish Question” (1843) Marx begins to make clear the distance between himself and his radical liberal colleagues among the Young Hegelians; in particular Bruno Bauer. Bauer had recently written against Jewish emancipation, from an atheist perspective, arguing that the religion of both Jews and Christians was a barrier to emancipation. In responding to Bauer, Marx makes one of the most enduring arguments from his early writings, by means of introducing a distinction between political emancipation—essentially the grant of liberal rights and liberties—and human emancipation. Marx’s reply to Bauer is that political emancipation is perfectly compatible with the continued existence of religion, as the contemporary example of the United States demonstrates. However, pushing matters deeper, in an argument reinvented by innumerable critics of liberalism, Marx argues that not only is political emancipation insufficient to bring about human emancipation, it is in some sense also a barrier. Liberal rights and ideas of justice are premised on the idea that each of us needs protection from other human beings who are a threat to our liberty and security. Therefore, liberal rights are rights of separation, designed to protect us from such perceived threats. Freedom on such a view, is freedom from interference. What this view overlooks is the possibility—for Marx, the fact—that real freedom is to be found positively in our relations with other people. It is to be found in human community, not in isolation. Accordingly, insisting on a regime of liberal rights encourages us to view each other in ways that undermine the possibility of the real freedom we may find in human emancipation. Now we should be clear that Marx does not oppose political emancipation, for he sees that liberalism is a great improvement on the systems of feudalism and religious prejudice and discrimination which existed in the Germany of his day. Nevertheless, such politically emancipated liberalism must be transcended on the route to genuine human emancipation. Unfortunately, Marx never tells us what human emancipation is, although it is clear that it is closely related to the ideas of non-alienated labour and meaningful community.

Even with these elaborations, many additional questions remain about Marx’s account. Three concerns are briefly addressed here.

First, one might worry about the place of alienation in the evolution of Marx’s thought. The once-popular suggestion that Marx only wrote about alienation in his early writings—his published and unpublished works from the early 1840s—is not sustained by the textual evidence. However, the theoretical role that the concept of alienation plays in his writings might still be said to evolve. For example, it has been suggested that alienation in the early writings is intended to play an “explanatory role”, whereas in his later work it comes to have a more “descriptive or diagnostic” function (Wood 1981 [2004: 7]).

A second concern is the role of human nature in the interpretation of alienation offered here. In one exegetical variant of this worry, the suggestion is that this account of alienation rests on a model of universal human nature which Marx’s (later) understanding of historical specificity and change prevents him from endorsing. However, there is much evidence against this purported later rejection of human nature (see Geras 1983). Indeed, the “mature” Marx explicitly affirms that human nature has both constant and mutable elements; that human beings are characterised by universal qualities, constant across history and culture, and variable qualities, reflecting historical and cultural diversity (McMurtry 1978: 19–53). One systematic, rather than exegetical, variant of the present worry suggests that we should not endorse accounts of alienation which depend on “thick” and inevitably controversial accounts of human nature (Jaeggi 2016). Whatever view we take of that claim about our endorsement, there seems little doubt about the “thickness” of Marx’s own account of human flourishing. To provide for the latter, a society must satisfy not only basic needs (for sustenance, warmth and shelter, certain climatic conditions, physical exercise, basic hygiene, procreation and sexual activity), but also less basic needs, both those that are not always appreciated to be part of his account (for recreation, culture, intellectual stimulation, artistic expression, emotional satisfaction, and aesthetic pleasure), and those that Marx is more often associated with (for fulfilling work and meaningful community) (Leopold 2007: 227–245).

Third, we may ask about Marx’s attitude towards the distinction sometimes made between subjective and objective alienation. These two forms of alienation can be exemplified separately or conjointly in the lives of particular individuals or societies (Hardimon 1994: 119–122). Alienation is “subjective” when it is characterised in terms of the presence (or absence) of certain beliefs or feelings; for example, when individuals are said to be alienated because they feel estranged from the world. Alienation is “objective” when it is characterised in terms which make no reference to the beliefs or feelings of individuals; for example, when individuals are said to be alienated because they fail to develop and deploy their essential human characteristics, whether or not they experience that lack of self-realisation as a loss. Marx seems to allow that these two forms of alienation are conceptually distinct, but assumes that in capitalist societies they are typically found together. Indeed, he often appears to think of subjective alienation as tracking the objective variant. That said, Marx does allow that they can come apart sociologically. At least, that is one way of reading a passage in The Holy Family where he recognises that capitalists do not get to engage in self-realising activities of the right kind (and hence are objectively alienated), but that—unlike the proletariat—they are content in their estrangement (and hence are lacking subjective alienation), feeling “at ease” in, and even “strengthened” by, it ( MECW 4: 36).

3. Theory of History

Marx did not set out his theory of history in great detail. Accordingly, it has to be constructed from a variety of texts, both those where he attempts to apply a theoretical analysis to past and future historical events, and those of a more purely theoretical nature. Of the latter, the “1859 Preface” to A Critique of Political Economy has achieved canonical status. However, the manuscripts collected together as The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845-46, are also a much used early source. We shall briefly outline both texts, and then look at the reconstruction of Marx’s theory of history in the hands of his philosophically most influential recent exponent, G.A. Cohen (Cohen 1978 [2001], 1988), who builds on the interpretation of the early Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov (1856–1918) (Plekhanov 1895 [1947]).

We should, however, be aware that Cohen’s interpretation is far from universally accepted. Cohen provided his reconstruction of Marx partly because he was frustrated with existing Hegelian-inspired “dialectical” interpretations of Marx, and what he considered to be the vagueness of the influential works of Louis Althusser (1918–1990), neither of which, he felt, provided a rigorous account of Marx’s views. However, some scholars believe that the interpretation that we shall focus on is faulty precisely for its insistence on a mechanical model and its lack of attention to the dialectic. One aspect of this criticism is that Cohen’s understanding has a surprisingly small role for the concept of class struggle, which is often felt to be central to Marx’s theory of history. Cohen’s explanation for this is that the “1859 Preface”, on which his interpretation is based, does not give a prominent role to class struggle, and indeed it is not explicitly mentioned. Yet this reasoning is problematic for it is possible that Marx did not want to write in a manner that would engage the concerns of the police censor, and, indeed, a reader aware of the context may be able to detect an implicit reference to class struggle through the inclusion of such phrases as “then begins an era of social revolution,” and “the ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out”. Hence it does not follow that Marx himself thought that the concept of class struggle was relatively unimportant. Furthermore, when A Critique of Political Economy was replaced by Capital , Marx made no attempt to keep the 1859 Preface in print, and its content is reproduced just as a very much abridged footnote in Capital . Nevertheless, we shall concentrate here on Cohen’s interpretation as no other account has been set out with comparable rigour, precision and detail.

In his “ Theses on Feuerbach ” (1845) Marx provides a background to what would become his theory of history by stating his objections to “all hitherto existing” materialism and idealism, understood as types of philosophical theories. Materialism is complimented for understanding the physical reality of the world, but is criticised for ignoring the active role of the human subject in creating the world we perceive. Idealism, at least as developed by Hegel, understands the active nature of the human subject, but confines it to thought or contemplation: the world is created through the categories we impose upon it. Marx combines the insights of both traditions to propose a view in which human beings do indeed create —or at least transform—the world they find themselves in, but this transformation happens not in thought but through actual material activity; not through the imposition of sublime concepts but through the sweat of their brow, with picks and shovels. This historical version of materialism, which, according to Marx, transcends and thus rejects all existing philosophical thought, is the foundation of Marx’s later theory of history. As Marx puts it in the “1844 Manuscripts”, “Industry is the actual historical relationship of nature … to man” ( MECW 3: 303). This thought, derived from reflection on the history of philosophy, together with his experience of social and economic realities, as a journalist, sets the agenda for all Marx’s future work.

In The German Ideology manuscripts, Marx and Engels contrast their new materialist method with the idealism that had characterised previous German thought. Accordingly, they take pains to set out the “premises of the materialist method”. They start, they say, from “real human beings”, emphasising that human beings are essentially productive, in that they must produce their means of subsistence in order to satisfy their material needs. The satisfaction of needs engenders new needs of both a material and social kind, and forms of society arise corresponding to the state of development of human productive forces. Material life determines, or at least “conditions” social life, and so the primary direction of social explanation is from material production to social forms, and thence to forms of consciousness. As the material means of production develop, “modes of co-operation” or economic structures rise and fall, and eventually communism will become a real possibility once the plight of the workers and their awareness of an alternative motivates them sufficiently to become revolutionaries.

In the sketch of The German Ideology , many of the key elements of historical materialism are present, even if the terminology is not yet that of Marx’s more mature writings. Marx’s statement in the “1859 Preface” renders something of the same view in sharper form. Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx’s view in the Preface begins from what Cohen calls the Development Thesis, which is pre-supposed, rather than explicitly stated in the Preface (Cohen 1978 [2001]: 134–174). This is the thesis that the productive forces tend to develop, in the sense of becoming more powerful, over time. The productive forces are the means of production, together with productively applicable knowledge: technology, in other words. The development thesis states not that the productive forces always do develop, but that there is a tendency for them to do so. The next thesis is the primacy thesis, which has two aspects. The first states that the nature of a society’s economic structure is explained by the level of development of its productive forces, and the second that the nature of the superstructure—the political and legal institutions of society—is explained by the nature of the economic structure. The nature of a society’s ideology, which is to say certain religious, artistic, moral and philosophical beliefs contained within society, is also explained in terms of its economic structure, although this receives less emphasis in Cohen’s interpretation. Indeed, many activities may well combine aspects of both the superstructure and ideology: a religion is constituted by both institutions and a set of beliefs.

Revolution and epoch change is understood as the consequence of an economic structure no longer being able to continue to develop the forces of production. At this point the development of the productive forces is said to be fettered, and, according to the theory, once an economic structure fetters development it will be revolutionised—“burst asunder” ( MECW 6: 489)—and eventually replaced with an economic structure better suited to preside over the continued development of the forces of production.

In outline, then, the theory has a pleasing simplicity and power. It seems plausible that human productive power develops over time, and plausible too that economic structures exist for as long as they develop the productive forces, but will be replaced when they are no longer capable of doing this. Yet severe problems emerge when we attempt to put more flesh on these bones.

Prior to Cohen’s work, historical materialism had not been regarded as a coherent view within English-language political philosophy. The antipathy is well summed up with the closing words of H.B. Acton’s The Illusion of the Epoch : “Marxism is a philosophical farrago” (1955: 271). One difficulty taken particularly seriously by Cohen is an alleged inconsistency between the explanatory primacy of the forces of production, and certain claims made elsewhere by Marx which appear to give the economic structure primacy in explaining the development of the productive forces. For example, in The Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels state that: “The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production” ( MECW 6: 487). This appears to give causal and explanatory primacy to the economic structure—capitalism—which brings about the development of the forces of production. Cohen accepts that, on the surface at least, this generates a contradiction. Both the economic structure and the development of the productive forces seem to have explanatory priority over each other. Unsatisfied by such vague resolutions as “determination in the last instance”, or the idea of “dialectical” connections, Cohen self-consciously attempts to apply the standards of clarity and rigour of analytic philosophy to provide a reconstructed version of historical materialism.

The key theoretical innovation is to appeal to the notion of functional explanation, also sometimes called “consequence explanation” (Cohen 1978 [2001]: 249–296). The essential move is cheerfully to admit that the economic structure, such as capitalism, does indeed develop the productive forces, but to add that this, according to the theory, is precisely why we have capitalism (when we do). That is, if capitalism failed to develop the productive forces it would disappear. And, indeed, this fits beautifully with historical materialism. For Marx asserts that when an economic structure fails to develop the productive forces—when it “fetters” the productive forces—it will be revolutionised and the epoch will change. So the idea of “fettering” becomes the counterpart to the theory of functional explanation. Essentially fettering is what happens when the economic structure becomes dysfunctional.

Now it is apparent that this renders historical materialism consistent. Yet there is a question as to whether it is at too high a price. For we must ask whether functional explanation is a coherent methodological device. The problem is that we can ask what it is that makes it the case that an economic structure will only persist for as long as it develops the productive forces. Jon Elster has pressed this criticism against Cohen very hard (Elster 1985: 27–35). If we were to argue that there is an agent guiding history who has the purpose that the productive forces should be developed as much as possible then it would make sense that such an agent would intervene in history to carry out this purpose by selecting the economic structures which do the best job. However, it is clear that Marx makes no such metaphysical assumptions. Elster is very critical—sometimes of Marx, sometimes of Cohen—of the idea of appealing to “purposes” in history without those being the purposes of anyone.

Indeed Elster’s criticism was anticipated in fascinating terms by Simone Weil (1909–1943), who links Marx’s appeal to history’s purposes to the influence of Hegel on his thought: