Romeo and Juliet

Introduction.

Welcome to the enchanting and tragic world of “Romeo and Juliet,” a timeless masterpiece crafted by the legendary William Shakespeare 🎭. Penned in the early 1590s, this play transports us to the heart of Verona, Italy, during the Renaissance, a period brimming with artistic and cultural blossoming.

William Shakespeare, the author, is often hailed as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s pre-eminent dramatist. His ability to weave complex characters, intricate plots, and universal themes into his plays has left an indelible mark on literature and theater.

“Romeo and Juliet” is categorized as a tragedy and stands as one of Shakespeare’s most celebrated works. It tells the story of two young star-crossed lovers whose deaths ultimately reconcile their feuding families. The play explores themes of love, fate, conflict , and the cruel hand of destiny, all encapsulated in Shakespeare’s beautiful and eloquent language.

Join us as we delve into the depths of this tragic love story, exploring its rich tapestry of characters, themes, and the literary brilliance of Shakespeare that continues to captivate audiences and readers centuries after its first performance 🌟.

Plot Summary

“Romeo and Juliet” unfolds in the beautiful, yet strife-ridden city of Verona, Italy. Here’s a detailed walkthrough of the main events:

Exposition — The play opens with a feud between the Montague and Capulet families, setting the stage for a story of love in the midst of conflict . Romeo Montague is introduced, heartbroken over his unrequited love for Rosaline.

Rising Action — At a Capulet party, Romeo meets and falls instantly in love with Juliet Capulet, unaware of her family ties. They both quickly realize the danger of their love due to their families’ rivalry. Despite this, they confess their love and decide to marry in secret with the help of Friar Laurence, hoping their union will end the feud.

Climax — Shortly after their secret marriage, a street brawl leads to the banishment of Romeo from Verona after he avenges the death of his friend Mercutio by killing Tybalt, Juliet’s cousin.

Falling Action — Juliet, devastated by Romeo’s banishment and her parents’ insistence that she marry Paris, a suitor, seeks Friar Laurence’s help. He devises a plan: Juliet is to drink a potion that simulates death. Romeo, informed of the plan by a message, is expected to rescue her from her family’s tomb.

Resolution — The message fails to reach Romeo, who, believing Juliet is dead, returns to Verona and kills himself beside her seemingly lifeless body. Juliet awakens, finds Romeo dead, and takes her own life. The discovery of their tragic end finally reconciles the Montagues and Capulets.

Through these events, “Romeo and Juliet” navigates through the exhilaration of young love, the despair of loss, and the hope for peace, only to conclude in the heart-wrenching tragedy of the young lovers’ deaths. Their story serves as a powerful reminder of the consequences of hatred and the redemptive, yet tragic, potential of love.

Character Analysis

“Romeo and Juliet” features a cast of characters that are as memorable as the story itself. Each character’s personality, motivations, and development throughout the play contribute significantly to the tragedy and its themes.

- Romeo Montague — Romeo is passionate, impulsive, and deeply in love with Juliet. Initially in love with Rosaline, his affections quickly shift to Juliet, illustrating his impetuous nature. His intense emotions often dictate his actions, leading to his eventual suicide over the presumed death of Juliet.

- Juliet Capulet — Juliet, though only thirteen, demonstrates a depth of maturity and passion beyond her years. Her love for Romeo propels her into a conflict with her family and societal expectations. Her determination to be with Romeo, even in death, underscores her profound love and the tragic impulsivity that mirrors Romeo’s.

- Friar Laurence — A Franciscan friar and Romeo’s confidant. He marries Romeo and Juliet, hoping to reconcile their feuding families. His well-intentioned plans, however, ultimately contribute to the tragic outcome. He represents the play’s moral compass, caught between good intentions and the harsh realities of the world.

- Mercutio — Romeo’s close friend, known for his quick wit and imaginative speeches. His death at the hands of Tybalt escalates the feud between the Montagues and Capulets, pushing Romeo towards vengeance. Mercutio’s skepticism of love and fate contrasts sharply with Romeo’s idealism.

- Tybalt Capulet — Juliet’s cousin, characterized by his fiery temper and pride in the Capulet name. His aggressive nature and hatred for the Montagues lead to his killing Mercutio, which sets off a chain of tragic events.

- The Nurse — Juliet’s nurse and confidante plays a crucial role in Romeo and Juliet’s secret marriage. She is a maternal figure to Juliet and provides comic relief in the play. However, her encouragement of Juliet’s relationship with Romeo also contributes to the unfolding tragedy .

- Capulet & Lady Capulet — Juliet’s parents, who are determined to see her married to Paris, a wealthy suitor. Their insistence and lack of understanding of Juliet’s love for Romeo place additional pressure on Juliet, contributing to her desperate actions.

- Montague & Lady Montague — Romeo’s parents, who are deeply concerned about their son’s melancholy at the play’s beginning. Their feud with the Capulets forms the backdrop of the tragedy .

This ensemble of characters, with their distinct personalities and intertwined fates, crafts a narrative that is both deeply personal and universally resonant, encapsulating the themes of love, fate, and the consequences of familial conflict .

Themes and Symbols

“Romeo and Juliet” is rich with themes and symbols that contribute to its enduring impact and relevance. Let’s delve into some of the major ones:

- Love versus Hate — The intense love between Romeo and Juliet stands in stark contrast to the deep-seated hatred between the Montagues and Capulets. This theme explores the duality of human emotion and the tragic consequences when hate overpowers love.

- Fate versus Free Will — The protagonists are often seen as “star-crossed lovers,” suggesting that their destinies are controlled by fate. Yet, their choices propel the narrative forward, questioning the extent to which their actions are predestined versus self-determined.

- The Inevitability of Death — Death looms large over the play, from the lovers’ initial flirtation with it through their tragic suicides. It serves as a reminder of the fleeting nature of life and the destructiveness of feud and misunderstanding.

- Youth versus Age — The impulsive, passionate perspectives of Romeo and Juliet clash with the more calculated and traditional views of the older generation. This theme highlights the rift between youthful idealism and the constraints imposed by societal norms.

- Individual versus Society — Romeo and Juliet’s struggle to be together despite their families’ enmity reflects the broader conflict between personal desires and social expectations. Their tragic end underscores the devastating effects of societal pressures.

- The Poison and the Dagger — Symbols of the death that Romeo and Juliet choose over life without each other, representing both the destructive force of their love and the societal pressures that make their love untenable.

- Light and Darkness — Often used to describe Juliet, light symbolizes the brightness of love in the darkness of hate and feud. Yet, darkness also becomes a sanctuary where Romeo and Juliet can express their love away from the prying eyes of the world.

- The Nightingale and the Lark — In their last night together, Juliet claims a nightingale ( symbol of night ) sings, not a lark ( symbol of morning), wishing to extend their time together. This symbolizes the lovers’ desire to remain in their private world, away from the realities of the day.

These themes and symbols weave through the narrative , enriching the text and offering layers of meaning that have fascinated readers and audiences for centuries. They speak to the complexities of human emotion, the tragic beauty of love, and the harsh realities of life, making “Romeo and Juliet” a timeless exploration of the human condition.

Style and Tone

William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” is celebrated not only for its compelling story but also for its distinctive writing style and tone , which play pivotal roles in creating the mood and atmosphere of the play. Here’s a closer look:

- Iambic Pentameter — Much of the play is written in iambic pentameter, a rhythmic scheme that mimics the natural flow of the English language. This meter adds a musical quality to the dialogue , enhancing its poetic nature.

- Blank Verse and Rhymed Couplets — Shakespeare employs blank verse extensively, which is unrhymed iambic pentameter. However, he also uses rhymed couplets to emphasize certain moments, adding a lyrical touch that highlights the beauty of the characters’ expressions of love or the finality of death.

- Vivid Imagery — The play is rich with imagery that evokes the senses, particularly in the descriptions of love and violence. This imagery serves to draw readers more deeply into the emotional landscape of the play.

- Metaphor and Simile — Shakespeare uses metaphor and simile to compare characters and situations to nature, the celestial, and the divine, thus elevating the story’s themes and relationships to a universal level.

- Oxymorons and Paradoxes — The frequent use of oxymorons and paradoxes, especially in the early stages of Romeo and Juliet’s love, reflects the complex and often contradictory nature of love itself.

- Foreshadowing — The tone of the play is heavily laced with foreshadowing, hinting at the tragic end. This creates a sense of inevitability and fate that looms over the narrative , affecting its mood and the audience’s engagement.

- Symbolic Language — Shakespeare uses language to imbue objects, moments, and decisions with symbolic meaning, enriching the thematic content and inviting deeper analysis.

- Varied Tone — The tone shifts dramatically throughout the play, from the light-hearted banter of Mercutio to the passionate exchanges between the lovers, and the tragic solemnity of the play’s conclusion. These shifts serve to underscore the play’s emotional depth and the volatility of the world it depicts.

Through these stylistic choices, Shakespeare crafts a work that is not only a story of love and tragedy but also a profound commentary on the human experience. The writing style and tone of “Romeo and Juliet” contribute significantly to its ability to resonate across ages, inviting readers and audiences into a world where love and fate collide with devastating consequences.

Literary Devices used in Romeo and Juliet

William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” is a treasure trove of literary devices that enrich the text and deepen its meaning. Here are the top 10 devices used throughout the play:

- Metaphor — Shakespeare frequently uses metaphors to draw comparisons between two unrelated things, enhancing the imagery and emotional impact of the dialogue . For example, Romeo’s description of Juliet as the sun elevates her beauty and the intensity of his love.

- Simile — Similar to metaphors, similes compare two different things using “like” or “as,” making the descriptions more vivid. Juliet’s beauty, for instance, is often compared to that of a rich jewel in an Ethiope’s ear.

- Personification — This device attributes human qualities to non-human entities or concepts. Shakespeare personifies death and night , making them active characters in the tragic story. Juliet, for example, beckons night to come so she can be with Romeo.

- Allusion — Allusions are references to well-known stories, figures, or events. Shakespeare alludes to classical mythology and historical figures to enrich the story’s context and deepen the characters’ experiences.

- Oxymoron — Combining contradictory terms, oxymorons capture the complex nature of the characters’ feelings and the paradoxical themes of the play, such as “brawling love” and “loving hate.”

- Foreshadowing — The use of hints or clues to suggest what will happen later in the play. Shakespeare foreshadows the tragic end of Romeo and Juliet’s love story from the very beginning, creating a sense of inevitable fate.

- Irony — Dramatic irony occurs when the audience knows something that the characters do not. This device heightens the tension and tragedy , especially as the lovers make fatal decisions based on misunderstandings.

- Pun — Shakespeare’s wordplay often involves puns , where words with multiple meanings create humor or emphasize a dual interpretation of events, adding layers to the dialogue .

- Symbolism — Objects, characters, or actions that represent larger concepts. The poison and dagger symbolize the destructive nature of Romeo and Juliet’s love, while light and dark represent their sanctuary from the world.

- Imagery — Descriptive language that appeals to the senses, painting vivid pictures in the audience’s mind. Shakespeare uses imagery extensively to describe the intensity of Romeo and Juliet’s love and the violence of the feud.

These literary devices not only enhance the beauty and richness of the text but also deepen our understanding of the characters, themes, and emotions that drive this timeless tragedy .

Literary Device Examples

For each of the top 10 literary devices used in “Romeo and Juliet,” here are three examples and explanations in table format:

Personification

Foreshadowing.

leads directly to her death. |

Each of these devices plays a crucial role in enhancing the narrative , deepening the emotional resonance, and enriching the thematic complexity of “Romeo and Juliet.”

Romeo and Juliet – FAQs

What is the main conflict in “Romeo and Juliet”? The main conflict stems from the ancient feud between two noble families of Verona, the Montagues and the Capulets. This enmity forms the backdrop against which the forbidden love story of Romeo and Juliet unfolds, leading to tragic consequences.

Who is responsible for the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet? Multiple characters contribute to the tragedy , including Romeo and Juliet themselves, for their impulsive decisions; Friar Laurence, for his ill-advised plan; and the Capulet and Montague families, for their enduring feud. The tragedy is a culmination of individual actions and societal pressures.

What themes are explored in “Romeo and Juliet”? Key themes include the forcefulness of love, the power of fate, the duality of light and darkness, and the conflict between individual desires and social institutions.

How does Shakespeare use irony in “Romeo and Juliet”? Shakespeare employs dramatic irony, allowing the audience to know crucial information that the characters do not, such as the true nature of Juliet’s “death.” This technique heightens the tragic tension and the emotional impact on the audience.

What role does fate play in “Romeo and Juliet”? Fate plays a central role, with the lovers described as “star-crossed” to suggest that their destiny is doomed from the outset. The characters frequently reflect on fate’s control over their lives, reinforcing the theme that their tragic end was predetermined.

Is “Romeo and Juliet” a cautionary tale? Yes, it can be interpreted as a cautionary tale about the dangers of hasty decisions, the intensity of young love, and the destructive nature of family feuds and societal expectations.

What literary devices are used in “Romeo and Juliet”? Shakespeare employs a variety of literary devices, including metaphor, simile, personification, allusion, oxymoron, foreshadowing, irony, puns , symbolism, and imagery, to enhance the narrative’s emotional depth and thematic complexity.

How does “Romeo and Juliet” comment on youth and age? The play contrasts the passionate, impulsive actions of the young lovers with the more measured, often cynical views of the older characters. This juxtaposition explores the clash between youthful idealism and the realities imposed by society and age.

What is the significance of the play’s setting in Verona? Verona serves as the iconic backdrop for the tragic love story, symbolizing a place where love, beauty, and tragedy intertwine. The historical feud between the city’s noble families underscores the theme of conflict that permeates the play.

How do Romeo and Juliet challenge societal norms? Romeo and Juliet defy their families’ expectations and the societal norms of their time by pursuing their love for each other, despite the deadly feud between their families. Their rebellion against these constraints highlights the play’s themes of love versus hate, individual versus society, and the struggle for personal happiness within rigid social structures.

This quiz is designed to test comprehension of “Romeo and Juliet” and covers a range of topics from plot details and character relationships to themes and literary devices.

Identify the literary devices used in the following excerpt from “Romeo and Juliet”:

“O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright! It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night Like a rich jewel in an Ethiope’s ear; Beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear! So shows a snowy dove trooping with crows, As yonder lady o’er her fellows shows. The measure done, I’ll watch her place of stand, And, touching hers, make blessed my rude hand. Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight! For I ne’er saw true beauty till this night .”

- Simile – “It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night / Like a rich jewel in an Ethiope’s ear;” and “So shows a snowy dove trooping with crows, / As yonder lady o’er her fellows shows.” These comparisons enhance Juliet’s beauty by contrasting it with the darkness of the night and the ordinary appearance of others.

- Metaphor – “O, she doth teach the torches to burn bright!” This implies Juliet’s beauty is so radiant that it outshines the torches, teaching them how to emit light.

- Hyperbole – “Beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear!” Romeo exaggerates Juliet’s beauty as being too good for this world, emphasizing his immediate and overwhelming attraction to her.

- Personification – “Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight!” Romeo gives his sight the human ability to swear, illustrating his shock at this newfound love which makes him question all previous experiences of love.

This exercise helps students identify and understand the use of similes, metaphors, hyperbole, and personification in enhancing the thematic and emotional depth of “Romeo and Juliet.”

A Summary and Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Although it was first performed in the 1590s, the first documented performance of Romeo and Juliet is from 1662. The diarist Samuel Pepys was in the audience, and recorded that he ‘saw “Romeo and Juliet,” the first time it was ever acted; but it is a play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life, and the worst acted that ever I saw these people do.’

Despite Pepys’ dislike, the play is one of Shakespeare’s best-loved and most famous, and the story of Romeo and Juliet is well known. However, the play has become so embedded in the popular psyche that Shakespeare’s considerably more complex play has been reduced to a few key aspects: ‘star-cross’d lovers’, a teenage love story, and the suicide of the two protagonists.

In the summary and analysis that follow, we realise that Romeo and Juliet is much more than a tragic love story.

Romeo and Juliet : brief summary

After the Prologue has set the scene – we have two feuding households, Montagues and Capulets, in the city-state of Verona; and young Romeo is a Montague while Juliet, with whom Romeo is destined to fall in love, is from the Capulet family, sworn enemies of the Montagues – the play proper begins with servants of the two feuding households taunting each other in the street.

When Benvolio, a member of house Montague, arrives and clashes with Tybalt of house Capulet, a scuffle breaks out, and it is only when Capulet himself and his wife, Lady Capulet, appear that the fighting stops. Old Montague and his wife then show up, and the Prince of Verona, Escalus, arrives and chastises the people for fighting. Everyone leaves except Old Montague, his wife, and Benvolio, Montague’s nephew. Benvolio tells them that Romeo has locked himself away, but he doesn’t know why.

Romeo appears and Benvolio asks his cousin what is wrong, and Romeo starts speaking in paradoxes, a sure sign that he’s in love. He claims he loves Rosaline, but will not return any man’s love. A servant appears with a note, and Romeo and Benvolio learn that the Capulets are holding a masked ball.

Benvolio tells Romeo he should attend, even though he is a Montague, as he will find more beautiful women than Rosaline to fall in love with. Meanwhile, Lady Capulet asks her daughter Juliet whether she has given any thought to marriage, and tells Juliet that a man named Paris would make an excellent husband for her.

Romeo attends the Capulets’ masked ball, with his friend Mercutio. Mercutio tells Romeo about a fairy named Queen Mab who enters young men’s minds as they dream, and makes them dream of love and romance. At the masked ball, Romeo spies Juliet and instantly falls in love with her; she also falls for him.

They kiss, but then Tybalt, Juliet’s kinsman, spots Romeo and recognising him as a Montague, plans to confront him. Old Capulet tells him not to do so, and Tybalt reluctantly agrees. When Juliet enquires after who Romeo is, she is distraught to learn that he is a Montague and thus a member of the family that is her family’s sworn enemies.

Romeo breaks into the gardens of Juliet’s parents’ house and speaks to her at her bedroom window. The two of them pledge their love for each other, and arrange to be secretly married the following night. Romeo goes to see a churchman, Friar Laurence, who agrees to marry Romeo and Juliet.

After the wedding, the feud between the two families becomes violent again: Tybalt kills Mercutio in a fight, and Romeo kills Tybalt in retaliation. The Prince banishes Romeo from Verona for his crime.

Juliet is told by her father that she will marry Paris, so Juliet goes to seek Friar Laurence’s help in getting out of it. He tells her to take a sleeping potion which will make her appear to be dead for two nights; she will be laid to rest in the family vault, and Romeo (who will be informed of the plan) can secretly come to her there.

However, although that part of the plan goes fine, the message to Romeo doesn’t arrive; instead, he hears that Juliet has actually died. He secretly visits her at the family vault, but his grieving is interrupted by the arrival of Paris, who is there to lay flowers. The two of them fight, and Romeo kills him.

Convinced that Juliet is really dead, Romeo drinks poison in order to join Juliet in death. Juliet wakes from her slumber induced by the sleeping draught to find Romeo dead at her side. She stabs herself.

The play ends with Friar Laurence telling the story to the two feuding families. The Prince tells them to put their rivalry behind them and live in peace.

Romeo and Juliet : analysis

How should we analyse Romeo and Juliet , one of Shakespeare’s most famous and frequently studied, performed, and adapted plays? Is Romeo and Juliet the great love story that it’s often interpreted as, and what does it say about the play – if it is a celebration of young love – that it ends with the deaths of both romantic leads?

It’s worth bearing in mind that Romeo and Juliet do not kill themselves specifically because they are forbidden to be together, but rather because a chain of events (of which their families’ ongoing feud with each other is but one) and a message that never arrives lead to a misunderstanding which results in their suicides.

Romeo and Juliet is often read as both a tragedy and a great celebration of romantic love, but it clearly throws out some difficult questions about the nature of love, questions which are rendered even more pressing when we consider the headlong nature of the play’s action and the fact that Romeo and Juliet meet, marry, and die all within the space of a few days.

Below, we offer some notes towards an analysis of this classic Shakespeare play and explore some of the play’s most salient themes.

It’s worth starting with a consideration of just what Shakespeare did with his source material. Interestingly, two families known as the Montagues and Capulets appear to have actually existed in medieval Italy: the first reference to ‘Montagues and Capulets’ is, curiously, in the poetry of Dante (1265-1321), not Shakespeare.

In Dante’s early fourteenth-century epic poem, the Divine Comedy , he makes reference to two warring Italian families: ‘Come and see, you who are negligent, / Montagues and Capulets, Monaldi and Filippeschi / One lot already grieving, the other in fear’ ( Purgatorio , canto VI). Precisely why the families are in a feud with one another is never revealed in Shakespeare’s play, so we are encouraged to take this at face value.

The play’s most famous line references the feud between the two families, which means Romeo and Juliet cannot be together. And the line, when we stop and consider it, is more than a little baffling. The line is spoken by Juliet: ‘Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?’ Of course, ‘wherefore’ doesn’t mean ‘where’ – it means ‘why’.

But that doesn’t exactly clear up the whys and the wherefores. The question still doesn’t appear to make any sense: Romeo’s problem isn’t his first name, but his family name, Montague. Surely, since she fancies him, Juliet is quite pleased with ‘Romeo’ as he is – it’s his family that are the problem. Solutions have been proposed to this conundrum , but none is completely satisfying.

There are a number of notable things Shakespeare did with his source material. The Italian story ‘Mariotto and Gianozza’, printed in 1476, contained many of the plot elements of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet . Shakespeare’s source for the play’s story was Arthur Brooke’s The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet (1562), an English verse translation of this Italian tale.

The moral of Brooke’s tale is that young love ends in disaster for their elders, and is best reined in; Shakespeare changed that. In Romeo and Juliet , the headlong passion and excitement of young love is celebrated, even though confusion leads to the deaths of the young lovers. But through their deaths, and the example their love set for their parents, the two families vow to be reconciled to each other.

Shakespeare also makes Juliet a thirteen-year-old girl in his play, which is odd for a number of reasons. We know that Romeo and Juliet is about young love – the ‘pair of star-cross’d lovers’, who belong to rival families in Verona – but what is odd about Shakespeare’s play is how young he makes Juliet.

In Brooke’s verse rendition of the story, Juliet is sixteen. But when Shakespeare dramatised the story, he made Juliet several years younger, with Romeo’s age unspecified. As Lady Capulet reveals, Juliet is ‘not [yet] fourteen’, and this point is made to us several times, as if Shakespeare wishes to draw attention to it and make sure we don’t forget it.

This makes sense in so far as Juliet represents young love, but what makes it unsettling – particularly for modern audiences – is the fact that this makes Juliet a girl of thirteen when she enjoys her night of wedded bliss with Romeo. As John Sutherland puts it in his (and Cedric Watts’) engaging Oxford World’s Classics: Henry V, War Criminal?: and Other Shakespeare Puzzles , ‘In a contemporary court of law [Romeo] would receive a longer sentence for what he does to Juliet than for what he does to Tybalt.’

There appears to be no satisfactory answer to this question, but one possible explanation lies in one of the play’s recurring themes: bawdiness and sexual familiarity. Perhaps surprisingly given the youthfulness of its tragic heroine, Romeo and Juliet is shot through with bawdy jokes, double entendres, and allusions to sex, made by a number of the characters.

These references to physical love serve to make Juliet’s innocence, and subsequent passionate romance with Romeo, even more noticeable: the journey both Romeo and Juliet undertake is one from innocence (Romeo pointlessly and naively pursuing Rosaline; Juliet unversed in the ways of love) to experience.

In the last analysis, Romeo and Juliet is a classic depiction of forbidden love, but it is also far more sexually aware, more ‘adult’, than many people realise.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

4 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet”

Modern reading of the play’s opening dialogue among the brawlers fails to parse the ribaldry. Sex scares the bejeepers out of us. Why? Confer “R&J.”

It’s all that damn padre’s fault!

- Pingback: A Summary and Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

- Pingback: A Short Analysis of the ‘Two Households’ Prologue to Romeo and Juliet – Interesting Literature

Comments are closed.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Introduction

Shakespeare is largely considered to be the greatest writer in the English language. Though we may find his writing an eloquent maze of prose today, we must remember that he was writing to every class and creed. 400 years in the future, a literary scholar may marvel over the complexity of rhyme and rhythm of a Jay Z song as we marvel over Shakespeare’s Sonnets. In his lifetime, William Shakespeare wrote thirty-nine plays, most of which are still read and performed today. Romeo and Juliet is one of the best known, and yet Shakespeare did not invent the story. The tragic tale of two star-crossed lovers existed for a few hundred years before Shakespeare took a stab at it, and audiences in the early modern era were familiar with the story before setting foot in the theater. It might seem surprising to modern audiences that this story wasn’t treading any new ground at the time of its “conception,” and some might wonder why the brilliant and mighty Shakespeare might have retold a story whose twisted ending came as no surprise to its audience. Shakespeare apparently felt driven to write the narrative all over again, and something about his version impacted audiences so intensely that it is today considered one of the greatest stories ever told. Why is it that Shakespeare’s version affected his audience deeply enough that it is still firmly lodged in the literary cannon? What about this story is so enduring? And most importantly: why is it so popular?

The time period in which Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet debuted was one of particular distress and turmoil. At the time, England was ravaged by the Bubonic Plague, which had a fatality rate of 50%. Theaters were closed during mass outbreaks, which likely impacted Shakespeare financially, since he lived off the revenue from theater admissions to his plays. England was also in the grips of the Catholic-Protestant divide, which often erupted into violence. Romeo and Juliet was written, directed, and enjoyed during a time characterized by fear, tension, and disease, effectively making it a play for people of any era, who grapple with their own catastrophes and terrors. The role of theatre and literature (in society at large. and in…ahem…classrooms) is hotly debated, and we cannot claim to have a definitive answer to this age-old question. We can, however, assert that the endurance of plays such as this one speaks to their ability to move people, to speak to them in ways that inspire their preservation through the ages. And so, we became inspired to make this age-old classic more readily accessible to you, both in the digital format that has made its way onto your screens, or paper copies that you hold in your hands, and in way that the content has been carefully collected and presented.

Our Process

In an effort funded through Open Oregon State and with support from Oregon State’s School of Writing, Literature, and Film, a group of 20 students, led by Dr. Rebecca Olson, crafted this edition of Romeo and Juliet with the vision that it be easily read and accessed by high school students everywhere. As a group, we decided upon a set of guiding principles, which included an effort to modernize spellings that are no longer in use, encourage your interaction with the text, and support the Shakespeare-related Common Core educational goals. Above all, we hope that this edition will allow you, the reader, to move through the text with little need to stop and look up an unfamiliar word, or to try and figure out what in the world a “Lanthorne” is (it’s an old-fashioned word for “lantern.” Could you imagine using that word for a lantern? Neither could we, so we changed it).

To put all this together, we created a set of guidelines to get us started. We decided which text versions of the play to use as primary sources and we settled on using one Quarto and the First Folio1. We decided that we wanted to include some very important things like footnotes—necessary to clarify some words and concepts, but often intimidating and numerous—but we determined that we’d keep them brief and use them only when necessary. We also decided on some more mundane things, like the font we wanted, which is clean and easily readable instead of that nasty Times New Roman. What ever happened to Times Old Roman anyway? We made countless other decisions at the outset of this project, and after establishing these ground rules we separated into editing groups, each focusing on a particular act within the play.

When the groups had completed their edited acts, we met again as a large group to review all the work together. It was at this time that we discovered how differently each editing group had approached our individual edited acts and scenes, while still following the same set of established guidelines. Should we use bold for the character names? How much white space should we include? Should there be one space after a line of dialogue, or two? How far should we indent the stage directions? What is the impact of these seemingly trivial questions on the experience of the reader? The team set out to analyze these and many other questions. Our deliberations were lengthy, and at times unexpectedly heated. We learned much about ourselves (and about our apparent passion for uniform margins and un-bolded character names).

After arranging our edition into a single, consistent document, we set out to consider the other requirements that go along with creating a new edition of an old work. We again separated into groups to address the facets of this project. There was a group to draft out scene and location summaries; a group to establish the technical formatting of the finished work; a group to reach out to high school teachers and students to better understand their needs and concerns when engaging with a canonical work such as Romeo and Juliet ; and a group to ensure that there was consistency in formatting throughout the edition. We also created a group to draft this introduction. We also identified individuals to work on creating the cover of this edition (which, we are sure you will agree, is top notch). With the groupings settled, and the work underway, the edition that you hold in your very hands (or upon your very screen) began to take shape.

In 2020, another class, led by Dr. Olson, has endeavored to recraft this edition. We have added sensitivity footnotes to represent changing opinions and social standards. We have also put a lot of energy into creating supplemental material for students and teachers alike as they become more familiar and comfortable with reading Shakespeare.

We recognize that there are numerous other editions out there, and fervently hope that this one will be effectively suited to your educational needs. But this may beg the question: why are there so many editions? Why not just use the original? Great question! The answer is that there not just one original edition. The idea of a singular “original” Shakespeare text is a common misunderstanding. Shakespeare was a 17th Century playwright, so he didn’t necessarily intend his works to be published for broad literary audiences–most published versions were printed after his death. This being the case, there is much debate regarding the authority of different published versions. In the particular instance of Romeo and Juliet , there are multiple versions, all of which can be seen as authentic or “original,” but are dissimilar from each other in sometimes slight and sometimes significant ways. Some scholars believe that people who attended the play numerous times and recorded the dialogue in writing produced the earliest versions of the texts. Others believe that these texts were generated by a few of the play actors. Theories abound regarding the original production. Maybe several of them are correct, maybe none, but whatever the case, this allows modern editors to have a selection of authentic Shakespearean texts to draw from, which leads to some distinct differences from one edition to the next. (Spoiler alert!) Did Juliet awaken before Romeo was fully dead? The text seems to indicate that she didn’t, but others have interpreted it differently. This play has passed through the hands of many, many editors through the centuries, all of whom have left their own distinct marks; our hope is that our varied perspectives and orientation toward our readers’ needs will result in an edition that is relatable in the events and motivations of characters that you will encounter.

Shakespeare’s Language

Shakespeare is famous for his plays. He is famous for the emotions and the responses that these plays inspire in those who interact with them. He is credited with creating over 1700 original words alone in the English language (you’re welcome, Jessica). And so, when we’re considering Shakespeare, we’re not looking just at the play, or the performance, or its history—we’re looking at the language.

Language has acted as Shakespeare’s central tool in creating some of the world’s greatest literary compositions. Both a powerful playwright and literary icon, the fundamental aspects of what makes Shakespeare’s work Shakespeare’s work in the first place—and what continues to perpetuate his worldwide fame—can be understood in some of his most recognizable moments. The average North American high school student can identify Romeo and Juliet as the source of “Wherefore art thou, Romeo?” as easily as they can fail a math test.

When we started out to create the world’s most accessible version of Romeo and Juliet , the biggest question that we were tasked to answer was: how do we treat the language? What needs to be changed? Should the text be completely modernized—removing early modern English altogether? What about iambic pentameter—the rhythmic meter that makes poetry of Shakespeare’s words? Is it necessary to preserve a rhythm that doesn’t seem so universal without the archaic pronunciation of the words within? Where does the line between historical preservation and accessibility meet, and how do we land at that crossroad?

The language in this edition is thus a compilation of the First Folio and Quarto, as well as the collective minds of dozens of students working diligently to achieve clarity and ensure comprehension. The language has been only slightly altered, so as to maintain Shakespeare’s original intent, and in order to also appeal to a more modern audience; punctuation has been updated where appropriate; spellings have been modernized. But the story is the same. The famous, dramatic, moving story of a forbidden love and its original contexts remains. If we have changed anything, it is so that such a story can be loved and adored (though, perhaps with a bit more reserve than either Romeo or Juliet display toward one another) and can be read by many, many more people.

Romeo and Juliet On Stage

“But soft, what light through yonder window breaks” is probably one of the most quoted and easily recognizable lines of Shakespeare. Good ol’ Romeo and Juliet have been around for centuries, brought to life again and again through the text that houses them. This text is read in high schools, watched on the stage, adapted for film, and even re-written in terms of a text conversation. But where did it all begin?

Originally, Romeo and Juliet was designed to be played on a thrust stage, which extends into the audience, allowing viewers to watch from three sides. Scenery was sparse to allow for quick action and a focus on the carefully crafted language. There was a rear balcony staged as Juliet’s window and a trapdoor for her tomb. The play ran briefly in London following the Restoration of Charles II when William Davenant, acclaimed “son of Shakespeare” (whether literary or biological, we’re still not sure), presented it at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Several adaptations made their way around, including a version set in ancient Rome and a version in which a father and daughter played the titular characters in 1744, which was not widely accepted (for obvious reasons, we think). In 1748, David Garrick, a man renowned in the world of theatre, staged a production of Romeo and Juliet at Drury Lane and removed all sexual references and jokes present in the text. Why someone would take the best bits out we do not know. However, this version became the standard for the next century.

When Shakespeare was staging performances of Romeo and Juliet , most all actors were men, which means that Juliet was traditionally played by men dressed up as women. This tradition persisted until the late 17th century. By the 19th century, playing the role of Juliet became an actress’s marker of success in the theatrical world, and by the mid-19th century women were even allowed to take on the role of Romeo as well.

Throughout the 1900s, several noted playwrights and producers adapted and toured the play. William Poel of the Elizabethan Stage Society created a version chock-full of fast-paced action and complicated stage directions, or blocking. Before directing the 1968 film version of the play, Franco Zeffirelli created an adaptation of the original script for the stage, and then his film premiered in 1968 at the Old Vic Theatre in London. The Old Vic was traditionally a venue for live theater, and had never before hosted a film screening. The Italian renaissance setting at the Old Vic was so realistic and natural that audience members were awed by the never-before-seen representational style of stepping into a virtual snapshot of Verona.

The film was adapted again for Baz Luhrman’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet , a lush cinematic experience that exemplified Lurhman’s decadent style. This version, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, brought the tale of tragic romance to a whole new generation of teenagers. To this day, the play is read, performed, and referenced at a massive scale, but echoes of the original production linger.

Reading Romeo and Juliet Today

The challenge presented to us in our editing of the second edition was simple: How to edit the text in a way that creates total accessibility. We were then presented with articles and journal entries speaking on the implied biases rooted deep within historical texts, including the one we present to you now. The task proved to be much more difficult than anticipated. The questions had much more nuanced solutions that required extensive discussion on how to effectively combat this biased writing. Questions like: Do we change the vocabulary? Can we remove iambic pentameter? What do we do with insensitive language? Through much deliberation, we decided to keep the core language used while adapting footnotes expressing the problematic usage of specific words and phrases. These “sensitivity footnotes” are meant to explain exactly why and how the noted section exercises human biases. We don’t want to ignore the problems of the past but recognize them and learn from them.

While everyone in the class acknowledged discomfort at passages that use human beings as a comparison base for worth, there was also a discomfort in changing the language. The language was problematic, but why hesitate? Through this awkward period, we decided to keep the language as a learning opportunity. It is important to look back on the problems of the past and see the harm caused by the bias infused writing. In order to counter those biases, the sensitivity footnotes have been added in their respective passages. These footnotes are meant to inform you where and how biases are slipped into the pages that have been read for centuries.

While we’re on the subject of important social ramifications of the play, we feel it’s important to talk about the crux of the play’s tragedy: the choice Romeo and Juliet make to die by suicide. To some it can seem strange, absurd, or even silly. Why would anyone kill themselves over someone they met only earlier that same week?

The suicides of Romeo and Juliet suggest that their love and subsequent marriage were more than the result of the exaggerated emotions of a first love. What other, less obvious factors were at play? What would drive someone to make the worst and most permanent of all mistakes? Rather than attempt to answer this question that has followed this text around like a phantom, we’ll leave you with some questions that help us contemplate the complicated tangle of intention and action in this play: How did Juliet view her future after being forced to marry someone she barely knew? Maybe Romeo felt locked into the family feud and was looking for an escape? By seriously considering the motivations that led these characters to a tragic end, can we learn how to better respond to those situations that inspire feelings of powerlessness?

We also wanted to recognize the medium of this work. A play is more than words on a page; a play is a story full of feelings and experiences that the actors and the audience bring to the table. A play like Romeo and Juliet is an experience that captivates and challenges the imaginations of people across generations, across centuries. Romeo and Juliet is not a static story about a boy and a girl. It is an open story about love between two people—a story that adapts and changes in the minds and bodies that contemplate and reenact it. We believe this play offers a chance to explore what love can actually mean, from a wide variety of genders, sexual orientations, and experiences. It is a story about the tragedies and triumphs of love, and its special power lies in its ability to inspire contemplation of these ideas in all who encounter it.

Slowly but surely, our world is warming up to the idea that love is universal regardless of the identity of the bodies involved with it. More and more, people are exploring characters with more flexible categories of analysis, opening up new (or centuries-old) avenues of sexuality that challenge a heterosexual-dominant narrative. Actors of all ages are subverting historically gendered roles to inspire audiences to question their implicit assumptions. Players and playgoers are not disregarding what these stories were, but are imagining new possibilities for what these stories could be. In other words, it can be tempting to think that the script is rigidly set, but in actuality there is a real freedom in the performance. We encourage students and teachers alike to embrace that freedom, to widen their perspectives and see Romeo and Juliet (and plays in general) as tools to help explore what it means to be human.

In any case, we’ll leave the answering of those questions to you. Just as we have enjoyed Romeo and Juliet in its many forms, and from the many angles through which we have viewed it, we hope that you will enjoy this newly revised edition!

The Editors

Corvallis, Oregon

December 2020

Romeo and Juliet Copyright © 2021 by Rebecca Olson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Website navigation

An Introduction to This Text: Romeo and Juliet

By Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine Editors of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions

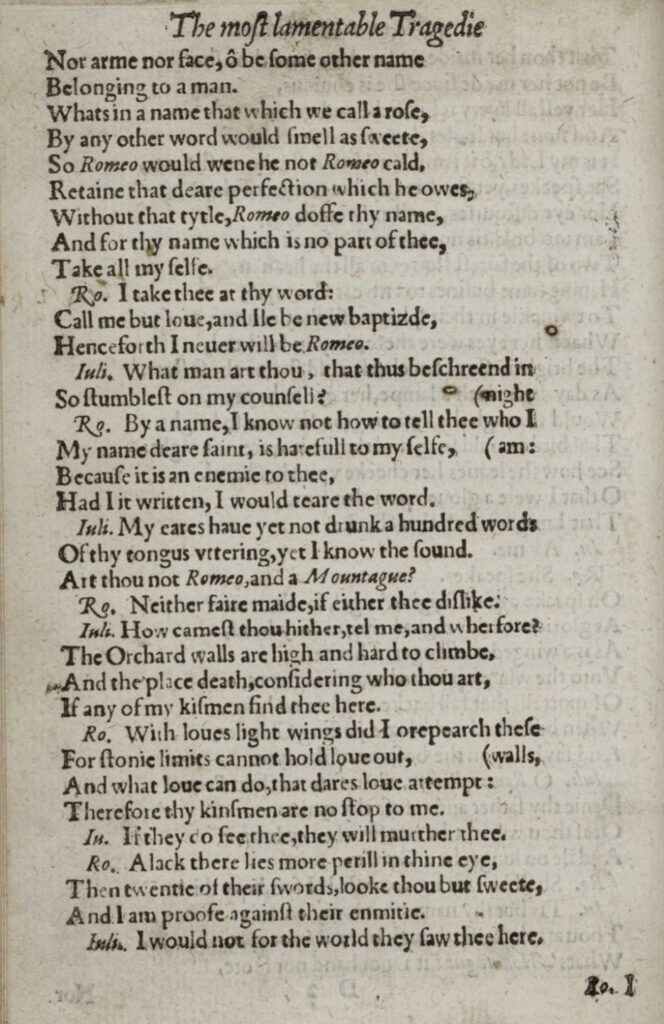

Romeo and Juliet was printed in a variety of forms between its earliest appearance in 1597 and its inclusion in the first collection of Shakespeare’s plays, the First Folio of 1623.

In 1597 appeared An Excellent conceited Tragedie of Romeo and Iuliet , a quarto or pocket-size book that offers a version of the play markedly different from subsequent printings and from the play that most readers know. This version is only about two-thirds the length of later versions. It anticipates the language of these later versions quite closely (except for some apparent cuts) until near the end of Act 2 . Then it offers a wedding scene that is radically different from the one in later texts. For the last three acts, the language of the First Quarto varies widely from that of later texts. While the plot is essentially the same, there sometimes is no sign at all of speeches found in later versions; and sometimes speeches appear in much abbreviated forms, which seem to most readers quite awkward in comparison to the fuller versions printed in 1599 and thereafter. This First Quarto has therefore been dubbed a “bad quarto.”

Explore the “bad quarto” of Romeo and Juliet (1597) in the Folger’s Digital Collections .

In 1599 the Second Quarto, often called the “good quarto,” was published. It was entitled The Most Excellent and lamentable Tragedie, of Romeo and Iuliet. Newly corrected, augmented, and amended. For the most part, this Second Quarto seems to have been printed from a manuscript containing the fuller version of the play that most readers know. Yet there are also undeniable signs that the printer of the Second Quarto consulted the First Quarto.

Explore the “good quarto” of Romeo and Juliet (1599) in the Folger’s Digital Collections .

For a short stretch ( 1.2.55 – 1.3.37 ), the Second Quarto seems to be no more than a reprint of the First Quarto. In 1609 a Third Quarto was reprinted from the Second.

Explore the Third Quarto of Romeo and Juliet (1609) in the Folger’s Digital Collections .

A Fourth Quarto, undated, was reprinted from the Third. This Fourth Quarto has been dated by Carter Hailey as having been printed in 1623. Its printer appears to have consulted the First Quarto for some corrections and word choices.

The First Folio version appeared in 1623. It reprinted the Third Quarto, but its printer’s copy must have been annotated by someone, because the Folio departs from the Third Quarto in ways that seem beyond the capacities of mere typesetters.

Recent editors have been virtually unanimous in their selection of the Second Quarto as the basis for their editions. In the latter half of the twentieth century it was widely assumed that (except for occasional consultation of the First Quarto) the Second Quarto was printed from Shakespeare’s own manuscript. In contrast, the First Quarto has been said to reproduce an abridged version put together from memory by actors who had roles in the play as it was performed outside London. Some editors have become so convinced of the truth of such stories about the First Quarto as to depend on it as a record of what was acted. Nevertheless, as today’s scholars reexamine the narratives about the origins of the printed texts, we discover that these narratives are based either on questionable evidence or sometimes on none at all, and we become more skeptical about ever identifying how the play assumed the forms in which it came to be printed.

The present edition is based on a fresh examination of the early printed texts rather than upon any modern edition. 1 It offers readers the text as it was printed in the Second Quarto (except for the passage reprinted in the Second Quarto from the First; there this edition follows the First Quarto). But the present edition offers an edition of the Second Quarto because it prints such editorial changes and such readings from other early printed versions as are, in the editors’ judgment, needed to repair errors and deficiencies in the Second Quarto. Except for occasional readings and except for the single reprinted passage, this edition ignores the First Quarto because the First Quarto is, for the most part, so widely different from the Second.

For the convenience of the reader, we have modernized the punctuation and the spelling of the Second Quarto. Sometimes we go so far as to modernize certain old forms of words; for example, when a means “he,” we change it to he ; we change mo to more , and ye to you . It is not our practice in editing any of the plays to modernize words that sound distinctly different from modern forms. For example, when the early printed texts read sith or apricocks or porpentine , we have not modernized to since, apricots, porcupine. When the forms an, and , or and if appear instead of the modern form if , we have reduced and to an but have not changed any of these forms to their modern equivalent, if. We also modernize and, where necessary, correct passages in foreign languages, unless an error in the early printed text can be reasonably explained as a joke.

Whenever we change the wording of the Second Quarto or add anything to its stage directions, we mark the change by enclosing it in superior half-brackets ( ⌜ ⌝ ). We want our readers to be immediately aware when we have intervened. (Only when we correct an obvious typographical error in the Second Quarto does the change not get marked.) Whenever we change the Second Quarto’s wording or its punctuation so that meaning changes, we list the change in the textual notes , even if all we have done is fix an obvious error.

We correct or regularize a number of the proper names, as is the usual practice in editions of the play. “Mountague” becomes “Montague,” for example, and the Prince’s name, “Eskales,” is printed as “Escalus.” Although neither Lady Montague nor Lady Capulet receives the honorific title “Lady” in the early printed versions of the play, the title is traditional in editions and is consistent with the social relations of the families as these are depicted both in the play and in its source. Therefore we refer to these characters as “Lady Montague” and “Lady Capulet.”

This edition differs from many earlier ones in its efforts to aid the reader in imagining the play as a performance. Thus stage directions are written with reference to the stage. For example, we do not describe Romeo and Juliet at their parting in Act 3 as being “at the window” (the First Quarto’s stage direction) because there is unlikely to have been an actual window above Shakespeare’s stage. Instead, we follow the Second Quarto and describe them simply as “aloft,” i.e., in the gallery above the stage.

Whenever it is reasonably certain, in our view, that a speech is accompanied by a particular action, we provide a stage direction describing the action. (Occasional exceptions to this rule occur when the action is so obvious that to add a stage direction would insult the reader.) Stage directions for the entrance of characters in mid-scene are, with rare exceptions, placed so that they immediately precede the characters’ participation in the scene, even though these entrances may appear somewhat earlier in the early printed texts. Whenever we move a stage direction, we record this change in the textual notes. Latin stage directions (e.g., Exeunt ) are translated into English (e.g., They exit ).

We expand the often severely abbreviated forms of names used as speech headings in early printed texts into the full names of the characters. We also regularize the speakers’ names in speech headings, using only a single designation for each character, even though the early printed texts sometimes use a variety of designations. Variations in the speech headings of the early printed texts are recorded in the textual notes.

In the present edition, as well, we mark with a dash any change of address within a speech, unless a stage direction intervenes. When the – ed ending of a word is to be pronounced, we mark it with an accent. Like editors for the last two hundred years and more, we display metrically linked lines in the following way:

( 1.1.163 –64)

However, when there are a number of short verse-lines that can be linked in more than one way, we do not, with rare exceptions, indent any of them.

- We have also consulted the computerized text of the Second Quarto provided by the Text Archive of the Oxford University Computing Centre, to which we are grateful.

Stay connected

Find out what’s on, read our latest stories, and learn how you can get involved.

Romeo and Juliet

William shakespeare, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Romeo and Juliet — Family Feud In Romeo And Juliet

Family Feud in Romeo and Juliet

- Categories: Artwork Creativity Romeo and Juliet

About this sample

Words: 725 |

Published: Mar 5, 2024

Words: 725 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Body Paragraphs

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 572 words

1.5 pages / 865 words

3 pages / 1504 words

3.5 pages / 1692 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Romeo and Juliet

Regret is an emotion that plagues us all at some point in our lives. It is a feeling of remorse or sadness about something that we wish we had done differently. As a college student, I have experienced my fair share of regrets, [...]

In William Shakespeare's famous tragedy "Romeo and Juliet," the theme of punishment plays a crucial role in shaping the actions and outcomes of the characters. Punishment, in its various forms, serves as a driving force behind [...]

Throughout William Shakespeare’s play, Romeo and Juliet, Friar Lawrence plays a pivotal role in the tragic outcome of the young lovers’ story. This essay will explore the question of whether Friar Lawrence is to blame for the [...]

Romeo and Juliet, one of William Shakespeare's most famous plays, is a tragic love story that is filled with foreshadowing. In this essay, we will analyze the use of foreshadowing in the play and how it contributes to the [...]

In William Shakespeare’s iconic play Romeo and Juliet, Tybalt plays a crucial role in propelling the tragic events that unfold. Despite his relatively brief appearances on stage, Tybalt’s fiery temperament and vengeful nature [...]

What a day it has been, maybe my family was right to suggest that I should start writing a diary. So far my life hasn’t been at all that interesting, although this morning perhaps changed my mind. So for now, I will go along [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Full Title: Romeo and Juliet. When Written: Likely 1591-1595. Where Written: London, England. When Published: "Bad quarto" (incomplete manuscript) printed in 1597; Second, more complete quarto printed in 1599; First folio, with clarifications and corrections, printed in 1623. Literary Period: Renaissance.

How to Write a Romeo and Juliet Essay. Your OCR GCSE English Literature exam will include questions on the Shakespeare play that you've been studying. You will have 50 minutes to complete one Romeo and Juliet question from a choice of two options: Either a question based on an extract (of about 40 lines) from Romeo and Juliet

Here are the top 10 devices used throughout the play: Metaphor — Shakespeare frequently uses metaphors to draw comparisons between two unrelated things, enhancing the imagery and emotional impact of the dialogue. For example, Romeo's description of Juliet as the sun elevates her beauty and the intensity of his love.

Romeo goes to see a churchman, Friar Laurence, who agrees to marry Romeo and Juliet. After the wedding, the feud between the two families becomes violent again: Tybalt kills Mercutio in a fight, and Romeo kills Tybalt in retaliation. The Prince banishes Romeo from Verona for his crime. Juliet is told by her father that she will marry Paris, so ...

A. Decision to give consent for Juliet to marry Paris. B. Reaction when Juliet refuses to marry Paris. C. Decision to move the date up one day. V. Impetuosity of Friar Laurence. A. Willingness to ...

In act 1, scene 5, Juliet accuses Romeo of kissing "by the book"; he certainly speaks by the book, like Astrophel studying "inventions fine, her wits to entertain" (Sidney's sonnet 1).

Romeo notes this distinction when he continues: Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon, Who is already sick and pale with grief. That thou, her maid, art fair more fair than she (ll.4-6 ...

Romeo and Juliet exchange vows of love, and Romeo promises to call upon Juliet tomorrow so they can hastily be married. The next day, Romeo visits a kindly but philosophical friar, Friar Laurence, in his chambers. He begs Friar Laurence to marry him to his new love, Juliet. Friar Laurence urges Romeo to slow down and take his time when it comes ...

Introduction Shakespeare is largely considered to be the greatest writer in the English language. Though we may find his writing an eloquent maze of prose today, we must remember that he was writing to every class and creed. 400 years in the future, a literary scholar may marvel over the complexity of rhyme and rhythm of a Jay Z song as we marvel over Shakespeare's Sonnets.

Romeo and Juliet, play by William Shakespeare, written about 1594-96 and first published in an unauthorized quarto in 1597.An authorized quarto appeared in 1599, substantially longer and more reliable. A third quarto, based on the second, was used by the editors of the First Folio of 1623. The characters of Romeo and Juliet have been depicted in literature, music, dance, and theatre.

Topic: The Role of Fate vs. Free Will in Romeo and Juliet; Introduction Example: "Romeo and Juliet" is often interpreted as a narrative dominated by fate, yet a closer examination reveals a complex interplay between destiny and the choices of its characters. This essay argues that while fate sets the stage, the personal decisions of Romeo ...

Romeo and Juliet was printed in a variety of forms between its earliest appearance in 1597 and its inclusion in the first collection of Shakespeare's plays, the First Folio of 1623.. In 1597 appeared An Excellent conceited Tragedie of Romeo and Iuliet, a quarto or pocket-size book that offers a version of the play markedly different from subsequent printings and from the play that most ...

Essay Planning 6 Exemplar Essays and Practice Papers . 2 ... AQA iGCSE Literature - Romeo and Juliet Tick if you have it Exam Practice 11 I have planned a response to a practice question 12 I have quotes in my answer 13 I have tackled the question and task clearly in my answer 14

Essay, Pages 10 (2332 words) Views. 6607. William Shakespeare in his work "Romeo and Juliet" tells about a beautiful, pure and sincere love, which unfortunately ends tragically. This is a narrative, recounting about tender feelings of young people have faced a cruel and inhuman world. Enmity, strife and blood feuds are trying to resist ...

See key examples and analysis of the literary devices William Shakespeare uses in Romeo and Juliet, along with the quotes, themes, symbols, and characters related to each device. Sort by: Devices A-Z. Scene. Filter: All Literary Devices. Allegory 1 key example. Allusions 2 key examples.

Family feud is a timeless theme that resonates with audiences across cultures and generations. In Shakespeare's famous tragedy, "Romeo and Juliet," the feud between the Montague and Capulet families serves as the central conflict that drives the narrative towards its tragic conclusion. This essay will delve into the intricate dynamics of the ...

Revise the characters of Romeo and Juliet for your GCSE English Literature exams with Bitesize interactive practice quizzes covering feedback and common errors.