- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Small Business

- Small Business Taxes

Profit Motive: Definition, Economic Theory, Characteristics

Julia Kagan is a financial/consumer journalist and former senior editor, personal finance, of Investopedia.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Julia_Kagan_BW_web_ready-4-4e918378cc90496d84ee23642957234b.jpg)

What Is the Profit Motive?

The profit motive is the intent to achieve a monetary gain in a project, transaction, or material endeavor. Profit motive can also be construed as the underlying reason why a taxpayer or company participates in business activities of any kind.

Simply put, the profit motive suggests that people tend to take actions that will result in them making money (profiting). In economic thought, Adam Smith identified the profit motive in his book, The Wealth of Nations, as the human propensity to truck, barter, and trade.

Key Takeaways

- The profit motive refers to an individual's drive to undertake activities that will yield net economic gain.

- Because of the profit motive, people are induced to invent, innovate, and take risks that they may not otherwise pursue.

- Profit motive is also a technical term used by taxing authorities to establish a basis for levying taxes.

Understanding the Profit Motive

Profit motive is thought to be one of the main drivers behind economic activity. Economists have often tried to figure out why people do the things that they do. Some answers point to simple survival. In most situations, people need some form of income to pay for the necessities of life. But what drives some people to take the risk of starting a business or innovating?

The answer can be framed in terms of an individual's profit motive—the drive to undertake some activity with the hope and expectation of being wealthier for doing so. In this view, the reason we live in a world of smartphones, fast fashion, and matcha lattes is because someone thought they could make money selling them.

The idea of a profit motive was behind Adam Smith's invisible hand , which suggests that self-interested, profit-seeking individuals are broadly beneficial to society. Smith noted that people seeking profit through the buying and selling of goods, for example, help to effectively distribute capital and goods far better than a political body could.

How the Profit Motive Works

In theory, the profit motive helps everyone from individuals to corporations decide what to do at a particular time. Looking at profit, or the potential for profit, simplifies many decisions. If a company makes five different products and earns most of its profit from just two, then the profit motive view would suggest that the company dump the unprofitable lines and invest more in the profitable production lines .

Similarly, a person would want to focus on the activities or employment opportunities that offer the most return for their efforts. For some people, this will mean the highest paying job. For others, it may mean creating their own enterprise with hopes of a higher income in the future.

The profitability of a particular activity is, in theory, communicated by market signals that ultimately are a function of supply and demand . The higher the demand (or potential demand), the higher the profitability (or potential profitability). When the profitability is high, more people and businesses will seek out that activity.

While the idea of profit being part of the motivation behind all manners of economic activity is not controversial in itself, there has been more scrutiny and analysis around applying it as the only factor in decision making.

Critiques of the Profit Motive

In practice, the profit motive is one of many factors that influences how people and businesses act. People, in particular, make their decisions based on a number of social and personal motivations beyond profit.

People may pick a less profitable activity because it benefits them in other ways that are not measured in terms of money. Businesses, too, are being encouraged not to focus solely on profits, particularly with the push for environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria .

The pushback against the profit motive as the main driver behind decisions is often connected back to the fallout of the 2008 financial crisis and the recession that followed. Corporations solely motivated by short-term profits and incentivized to seek them by investment capital wreaked havoc on a highly interconnected global economy .

Although many of the critiques and criticisms were targeted at companies looking for excess profits while ignoring inherent risks , the idea of the profit motive being a benevolent force acting on society was also a frequent target. While the idea of the profit motive is still seen as broadly correct and able to explain economic activity in general terms, it is not meant to be a playbook for companies to use in all their decisions.

Profit Motive and Taxation

The profit motive is used in a more modest way as a defining factor in tax decisions. According to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), taxpayers may deduct ordinary and necessary expenses for conducting a trade or business. An ordinary expense is an expense that is common and accepted in the taxpayer’s trade or business. A necessary expense is one that is appropriate for the business. Generally, an activity qualifies as a business if it is carried on with the reasonable expectation of earning a profit, that is, an activity undertaken with a profit motive.

Profit motive is also what separates a hobby from a business in the eyes of the IRS— losses from a hobby are non-deductible because there is no intent to make real economic profit. Since hobbies are activities participated in for self-gratification, losses incurred from engaging in them cannot be used to offset other income. Hobby income, even if occasional, must be reported as “ordinary income” on Form 1040 .

Taxpayers used to be able to deduct hobby losses as a miscellaneous itemized deduction on Schedule A, but the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 eliminated that deduction.

Another way a business owner can establish profit motive is by showing that they operated for profit under the IRS's nine criteria profit motive test. The nine critical factors used by the IRS to determine whether a business is run for profit or as a hobby are:

- Whether the activity is conducted in a business-like manner

- The expertise of the taxpayer or their advisers

- Time and effort spent in operating the business

- The likelihood that the business assets will appreciate in value

- Past success of the taxpayer in engaging in a similar (or dissimilar) venture

- History of income or loss of the activity

- Amount of any occasional profits earned

- Taxpayer’s financial status

- Any elements of personal pleasure or recreation

Internal Revenue Service. " Deducting Business Expenses ." Accessed Aug. 26, 2020.

Internal Revenue Service. " Publication 525: Taxable and Nontaxable Income ." Accessed Aug. 26, 2020.

Internal Revenue Service. " IRC Sec. 183: Activities Not Engaged in For Profit (ATG) ," page 4. Accessed Aug. 26, 2020.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/stk128219rke-5bfc2b8a46e0fb005144db8f.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

This site uses cookies to store information on your computer. Some are essential to make our site work; others help us improve the user experience. By using the site, you consent to the placement of these cookies. Read our privacy policy to learn more.

- TAX INSIDER

How to determine profit motive

In two cases, the tax court looked at factors besides a history of losses in determining whether the hobby loss rules would prevent the taxpayers from deducting their expenses..

- Individual Income Taxation

As professionals, we've been beaten over the head with the Sec. 183 hobby loss rules, which prohibit deductions for activities not engaged in with the intent of making a profit. Some practitioners think, and with good reason, that to avoid the hobby loss rules, a company has to show a profit after three years, but that's more a rule of thumb. For example, let's say a client is aggressively attempting to realize income from the activity and after year 3, he or she is still not turning a profit. Does this mean that the client must ignore a loss in year 4 of the activity? To answer this question, let's examine two U.S. Tax Court cases addressing profit motive that have recently been decided, in which the court looked more at other factors than how many years of losses occurred before ruling against the taxpayers.

The first case is Hylton , T.C. Memo. 2016-234. Cecilia Hylton is the president of the Hylton Group, a successful real estate group founded by her father. Hylton Group's business is primarily developing real property, building and selling residences and apartment buildings, and managing commercial and residential properties in Virginia.

In 1998, Hylton started Hylton Quarter Horses (HQH), the main business of which is breeding, training, showing, and selling quarter horses. The predominant use for quarter horses is recreational riding, but they are also used in rodeos and horse shows and as working ranch horses.

In operating HQH, Hylton sought to raise the best quarter horses possible by adopting the following practices: getting the best mares; acquiring stallions to breed; breeding the mares; producing foals; and culling some of the foals and training the remainder. Hylton did not prepare a formal business plan when she started HQH, but the record includes an undated five-page written "business plan" that included a single-page income and expense projection and was prepared by her CPA in response to an IRS audit.

Sometime after 2005, Hylton moved some of HQH's breeding horses from Virginia to Texas, because it is "the premier show place" of quarter horses and the location of many breeding experts. She kept mares, colts, and her three stallions in Texas and contracted with three entities there. She usually traveled to Texas once a year for approximately one week.

During the years in issue, Hylton maintained a separate mailing address for HQH and a separate checking account, which was used to pay most of HQH's horse-related expenses—feed, trainers, veterinarians, and blacksmiths. She maintained a separate brokerage account for HQH, which was used to pay show fees, camping fees, and other horse-show-related expenses.

Hylton and her horse activity team would typically meet "once a month, sometimes more" to review HQH's invoices and receipts. No minutes or records were kept of these meetings. HQH's invoices and receipts were kept in files at Interstate Investment and would be provided to Hylton's tax return preparer to prepare returns.

For each of the years 2004 through 2011 HQH's expenses far exceeded its income, with almost $2 million in losses being incurred in two of those years.

The IRS determined that Hylton's ownership and operation of HQH was an activity "not engaged in for profit" under Sec. 183 and disallowed loss deductions claimed on her Schedules F, Profit or Loss From Farming , for those years. A taxpayer may not fully deduct expenses from an activity under Sec. 162 or 212 if the activity is not engaged in for profit (Sec. 183(a)). If an activity is not engaged in for profit, no deduction is allowed except to the extent provided by Sec. 183(b), which allows deductions only to the extent of gross income from the activity. Sec. 183(c) defines an activity not engaged in for profit as " any activity other than one with respect to which deductions are allowable for the taxable year under section 162 or under paragraph (1) or (2) of section 212."

Deductions are allowed under Sec. 162 for the ordinary and necessary expenses of carrying on an activity that constitutes the taxpayer's trade or business. Deductions are allowed under Sec. 212 for expenses paid or incurred in connection with an activity engaged in for the production or collection of income or for the management, conservation, or maintenance of property held for the production of income. Both Code sections require a profit motive, which is interpreted similarly as requiring profit to be a primary purpose (see Groetzinger , 480 U.S. 23 (1987), in which the Court held that a gambler had a primary purpose of making a profit and could therefore deduct his losses).

Under Sec. 183(d), an activity that consists in major part of the breeding, training, showing, or racing of horses is presumed to be engaged in for profit if the activity produces gross income in excess of the deductions for any two of seven consecutive years. Because HQH did not produce income in excess of its deductions at any time, the presumption does not apply.

Regs. Sec. 1.183-2(b) provides a nonexhaustive list of the nine factors to determine whether an activity is engaged in for profit:

- Whether the taxpayer carries on the activity in a businesslike manner;

- The expertise of the taxpayer or his or her advisers;

- The time and effort expended by the taxpayer in carrying on the activity;

- The expectation that the assets used in the activity may appreciate in value;

- The success of the taxpayer in carrying on similar or dissimilar activities;

- The taxpayer's history of income or losses for the activity;

- The amount of occasional profits, if any, which are earned;

- The taxpayer's financial status; and

- Elements of personal pleasure or recreation.

All facts and circumstances are to be taken into account, and no single factor is determinative. The court examined each of these factors in turn and determined that Hylton did not participate in the quarter horse activity with a profit motive as her primary or dominant objective.

In Moyer , T.C. Memo. 2016-236, the facts are a little different, but the same principle applies. Calvin Moyer was educated as a chemist. In 1968, he joined DuPont's human relations department, where he trained DuPont employees in a variety of human relations topics.

Moyer took early retirement from DuPont in January of 1992 at age 50. Sometime after he retired, but before 2004, both Moyer and his wife began receiving DuPont pensions and Social Security benefits.

In 1992, DuPont outsourced much of its human relations training. Moyer and four other retired DuPont employees started a business to provide DuPont with human relations training services as outside contractors similar to those they had provided at DuPont. In 1994, after disagreeing on business strategy, the group agreed to cease doing business.

In 1994, Moyer and another person formed Strategic Learning Systems Inc. (SLS), an S corporation, which provided human relations training, including in-class human relations training on a variety of topics, and created several marketing brochures. These trainings were one-day workshops with DuPont—SLS's only client. DuPont constituted at least 80% to 90% of SLS's total business. In 1996, Moyer's partner left SLS, and Moyer ran it himself.

In 2005, SLS lost DuPont as a client and after 2006 it did not have any other clients. SLS had no gross receipts for 2010 through 2015.

SLS never kept books or records or maintained a budget. Moyer did not use books or records to evaluate the business's financial performance, nor did he file a timely tax return for SLS for the 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, or 2008 tax years. In 2014, SLS filed delinquent Forms 1120S, U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation , for those years in connection with previous Tax Court cases after the IRS had issued notices of deficiency to him (as SLS's shareholder) or to his wife (because she signed their joint return). Moyer acknowledged in his testimony that the preparation of the Forms 1120S in 2014 was the first time he ever determined SLS's annual expenses for tax or any other purpose.

Neither Moyer, his wife, nor SLS timely filed a federal income tax return for the 2009 tax year.

In 2012, the IRS mailed Mrs. Moyer a substitute for return and a notice of deficiency for 2009 using the married-filing-separately filing status and determining a deficiency of $9,006 along with penalties under Secs. 6651(a)(1), 6651(a)(2), and 6654(a).

On Oct. 20, 2014, the taxpayers submitted a joint federal income tax return for 2009, which itemized deductions on Schedule A, Itemized Deductions . Mr. Moyer also submitted a Form 1120S for SLS for 2009, which Mr. Moyer was the sole owner of during 2009. He admitted that SLS had not earned a profit since at least 2004.

SLS reported losses on Forms 1120S for 2004 through 2009

In determining whether Calvin Moyer had an actual and honest objective of making a profit, the court first considered whether he conducted SLS's activity in a businesslike manner, as described in Regs. Sec. 1.183-2(b)(1).

Moyer testified that he did not attempt to determine SLS's expenses until the IRS issued its notices of deficiency. He also testified that he is "not good at keeping records." SLS neither kept contemporaneous records nor maintained a budget.

Moyer had no books or records from which he could evaluate SLS's profitability. SLS also did not file income tax returns for 2004 through 2009 but filed returns only in connection with Tax Court cases, several years after they were due. Asked whether failing to timely file income tax returns is a good business practice, Moyer responded: "It certainly isn't." All of these facts indicate a failure to conduct the activity in a businesslike manner, which in turn indicates the lack of a profit motive.

Although Moyer may have originally had a profit objective when he incorporated SLS in 1994, this was no longer true during the years in issue, the court held. By 2009, SLS was merely a convenient device by which the Moyers could try to deduct otherwise nondeductible personal expenses.

Profit motive

In both cases, the Tax Court found that the taxpayer had failed to demonstrate a clear profit motive, but the court looked at more than the fact that the business had losses for a string of years. As the cases show, it isn't simply the number of years in which a company took a loss that determines whether a taxpayer carried on a business with a profit motive; a court will also look at the motivation behind the business and the manner in which the taxpayer ran the business in determining whether the taxpayer had a profit motive.

Craig W. Smalley , MST, is an enrolled agent who is the founder and CEO of CWSEAPA, PLLC, which provides accounting and financial services.

Sale of clean-energy credits: Traps for the unwary

Tax consequences of employer gifts to employees, top 8 estate planning factors for real estate, success-based fees safe harbor: a ruling raises concerns, pond muddies the waters of the mailbox rule.

This article discusses the history of the deduction of business meal expenses and the new rules under the TCJA and the regulations and provides a framework for documenting and substantiating the deduction.

PRACTICE MANAGEMENT

CPAs assess how their return preparation products performed.

Understanding Profit Motive to Make the Most Out of Your Small Business

November 18, 2020 ben shabat.

Regardless of the industry you’re in, how long you’ve been in business, or how big your company is, your business should be profit-oriented.

The simple fact is, if your business isn’t making money, it’s losing money.

That’s why it’s essential to know what the profit motive is and how it works, so you can build a more profitable business!

Profit motive definition

Profit motive is the incentive to earn net financial gains by undertaking any sort of business activity. That applies to companies as well as individuals, whether they’re buying, selling, or taking part in any other sort of economic endeavor.

For small businesses specifically, profit motive can often be the primary driving force behind activities such as operational cost reduction , developing innovative ideas, coming up with new pricing strategies , taking tactical risks, or even completely overhauling the business plan.

In short: Profit motive is the goal of increasing profit for your business – something every business owner should be aiming for!

To some, the profit motive definition may sound like a selfish enterprise for a business to be focused solely on. But the fact is that many (if not most) of the great inventions over the past few centuries were made in an effort to earn a profit. That includes the invention of advanced medical technology, computers and smartphones, credit cards, nearly every home appliance, the automobile, and even the lightbulb!

Without the profit motive, our world would be a very different place from what we know it to be today.

If your business isn’t profit-oriented yet, now is the time to consider making the profit motive a key component of your business plan.

Using the profit motive to increase revenue

The profit motive is a natural driver for increasing your business’s revenues. When it comes to making changes to your business, the profit motive helps to simplify the decision-making process for you by essentially eliminating those ideas that don’t have a high likelihood of generating a profit.

For example, investing in renovating your physical storefront may be something you want to do and something that could potentially impact your sales, but if most of your business is conducted online then an expensive renovation might not be a profitable project for your business to undertake. On the other hand, if you took that money and invested it in improving your e-commerce advertising strategy , that project could stand a better chance of earning a net gain for your business.

In all likelihood, you’re likely already doing everything you can to spend the least amount of money and make the most earnings for your business. That’s the profit motive in action!

What some owners aren’t aware of is that the effort to increase your business’s profits actually makes an impact that goes beyond your own enterprise. On a broader scale, the profit motive works to influence the market’s prices, sometimes driving prices up sometimes driving them down – which, in turn, affects the decisions you make for your business. This is the classic economic model of supply and demand.

Let’s say, for example, you run a business that sells furniture and it costs $10 to purchase raw materials and another $10 to manufacture a dresser. That means the cost of production for each dresser is $20. The profit motive would dictate that you need to sell each dresser for more than $20 in order to optimize the return on your investment.

An important detail is that, even if your business is profit-oriented, you won’t be able to earn a net gain unless there are customers who are willing to pay more than $20 for a dresser. In other words, there must be a demand for your products/services in order for your business to successfully use the profit motive.

If there’s already a large supply of dressers of similar quality offered for $15 by your competitors, the profit motive would incentivize you to find ways to bring your costs down in order to make more sales, make a larger profit, and stay ahead of your competition.

On the flip side, if you don’t have many competitors and dressers are in short supply , that would mean a higher demand for dressers. In that case, customers would possibly be willing to pay $30 or even more for a dresser, allowing you to remain profit-oriented, make better earnings, and still be providing a valuable product to people at a price they’ll find reasonable.

In short: The profit motive acts as a shaper of the market and is also shaped by the market. Pay close attention to levels of supply and demand so that your business can stay profit-oriented.

Profit motive for e-commerce businesses

While there’s just one profit motive definition that applies to both ‘offline’ businesses and online businesses, there are a few ways that the profit motive can play out differently for e-commerce businesses specifically.

How the profit motive can influence e-commerce business decisions:

- Reduce overhead costs and switch to a dropshipping model so you can stop paying for inventory storage

- Start minimizing returns and refunds by developing top-notch customer support (Roughly 70% of customers say they’d stop paying for a product or service if they had even one bad experience with customer support )

- Invest in optimizing your supply chain so you can streamline processes, plan for demand, and negotiate for better supplier rates

- Measure profit and expenses to understand/increase your profit margins and see how to keep your excess expenses at a bare minimum

- Expand into multi-channel selling to engage with omnichannel customers who spend 30% more when they make purchases on average

Side note: If you run a Shopify store, you can measure your profits and expenses accurately with the BeProfit – Profit Tracker Shopify app (developed by Become ). After using the BeProfit dashboard to clearly understand your store’s finances, you can decide whether an e-commerce business loan is the right way to take your store to new heights.

Make the most of your business

Being profit-oriented is crucial to running a successful business. After all, if you’re not in business to make money, what are you in business for?

Okay, to be fair, the profit motive shouldn’t be the only incentive that keeps you in business. You’ll have to prioritize other qualities such as customer satisfaction, environmental awareness, and other social causes – otherwise, you may find yourself having a hard time building a strong business.

There’s a balance to be struck and it’s okay if it takes some time before you get it right. Just be sure not to forget how powerful the profit motive is and the role it plays in making the most out of your business!

Related Posts

What came first the job or the experience? This well-known chicken and egg scenario is…

Starting April 20, small businesses in need of short-term financial relief can turn to the…

With so many options out there, it can be difficult to choose the right small…

Small businesses in the USA can now gain free access to their Experian business credit…

[xyz-ips snippet=”Right-Banner”]

To get access to the full article answer 2 quick questions:

Get the full article right now.

Finding relevant lenders...

Searching Loan Offers For " "

We appreciate your interest in Become, to make the process easier and even faster Check if you qualify

What is Profit Motive (& How to Leverage it in Your Business)

If you want to make money, then you already know what the profit motive is.

But if that’s all there is to it, then why did we write this article? Because there’s so much more to know about the profit motive!

No matter if you’re just coming up with a business idea , or running a major enterprise, knowing the ins-and-outs of this critical concept will give you more power to control the direction of your business.

It’s not enough just to know the basic definition we gave above; get all the details below and learn how to make the most of the profit motive for your eCommerce business. Let’s go!

What is Profit Motive?

Profit motive is the goal that drives organizations and individuals alike to earn a net financial gain through their business activities. Without the profit motive, it’s questionable whether or not businesses would ever pay such close attention to things like:

- Carefully selecting a pricing strategy

- Finding new technologies to streamline operations

- Calculating return on ad spend (ROAS)

- Cutting overhead costs

- Measuring and tracking customer lifetime value

The common underlying reason for all of those very different objectives? The desire to make more money. That’s the profit motive definition.

You may have a question or two about profit motive, for example, “can’t ‘profit motive’ turn into ‘greed’?” Or “is it possible for the profit motive to blind us to other important goals in business?” In short, the answer is yes – but there’s much more to the profit motive that makes it worth pursuing.

And, just as is the case with most other tools, the profit motive can be good or bad depending on how you use it. Take a look below to discover the potential benefits and drawbacks of the profit motive, and a whole lot more that follows!

The Good Side of Profit Motive

- Maintains a healthy market by creating competition among sellers to keep costs and prices down, thereby saving money and also attracting customers

- Forces businesses to plan for the long-term, and to even tolerate low profits or losses for the better chances of having higher profits in the future

- Puts pressure on businesses to find more efficient ways of conducting business, which can help reshape industry standards for the better

- Creates an incentive for businesses to create new/better products

The Bad Side of Profit Motive

- Taken to the extreme, it can lead entire industries to engage in risky financial practices that can ultimately result in larger economic crises (think about the ‘housing bubble’ that burst and led to the Great Recession of 2008 )

- When held as the only important factor, the profit motive can convince businesses to cut product quality in order to save money, potentially endangering employees, consumers, or the environment in the process (find examples of corporations that put profit before safety in this Howard Law article titled They Knew and Failed To )

- Though it doesn’t typically apply to eCommerce businesses, there are situations where if profit is the only goal and all ethics go out the window, people who desperately need access to a product can be unjustly forced to pay exorbitant amounts for something that is produced for a small fraction of the price (for example, the infamous case of the pharmaceutical executive Martin Shkreli who monopolized a life-saving drug and then raised the price by more than 4,000%)

The downsides to profit motive can be a bit nerve racking to read about, but those are fairly extreme cases and aren’t the norm, particularly not in the eCommerce industry. Still, it’s good to know where the pitfalls are so that you can steer clear of them if need be.

With those warning signs in place, let’s discuss the real reasons why you would want to maximize profit for your e-commerce business.

Why Would You Want to Maximize Profit?

Simply put, the reason you would want to maximize profit for your online store is because more money gives you more options and opportunities to strengthen your business.

The next question you might want to ask is “what options and opportunities open up when I have more profit” – and we’re glad you asked!

When you’ve found ways to increase profit for your business , the results can include having an easier time:

- Expanding your business into new market areas

- Attracting greater numbers of high-quality leads

- Incorporating technologies to streamline operations

- Offering new types of products or services

- Diversifying your e-commerce advertising strategy

To reiterate, the most apparent reason you have for wanting to maximize your ecommerce profits is to make your business bigger and better. The more you optimize your store, the larger your profits can grow, and the more you can optimize.

As you can see, when used the right way, profit motive can be the force that turns the wheels of success for your online business. But, how do you calculate profit margins for your business anyway? After all, if you don’t measure profitability, how can you know how it changes over time?

Profit Motive 101: How to Measure Profit

Measuring profit for your ecommerce business isn’t tough, but does require attention to detail. Plus, if you really want to improve your profits, you’ll need to track how your profit margins shift and change over time. That means measuring your profitability on a regular basis, ideally at least once a month.

There are several ways you can measure your profit:

- Gross profit margin is used as a gauge for how well your business is handling the direct costs associated with generating sales

- Operating profit margin is a measurement of how well a business’s secondary investments (e.g. (research, marketing, administrative expenses) are paying off

- Net profit margin is what people typically think of when they hear the words ‘profit margin’; it calculates the relationship between net profits and net sales

However you do it, measuring profit is a key step toward growing your profits! Keep your eye on the prize by calculating your profit margins on a regular basis, analyzing the data you gather, finding trends, and adjusting for better margins as you go.

Profit Motive Examples in eCommerce

Profit motive examples in eCommerce are plentiful! You only need to take a glimpse into the world of online retail operations to understand how the drive to earn a profit has helped that industry bloom over recent years.

As a matter of fact, global retail e-commerce sales have not only been on an upward trajectory, but they are projected to exceed $5.4 trillion by 2022 – whoa!

Here are our top three picks for best profit motive examples in eCommerce:

Founded in 2013, MVMT is (well, was ) one of the biggest names in e-commerce. They rose quickly to be valued at $90 million in less than 5 years, ultimately getting acquired by Movado for $300 million.

How did they rise to those heights in such a competitive niche? Facebook Ads!

They went all-in and ramped up what they saw was already working for them. While it sounds like a roll of the dice, it was anything but that. More likely than not, they ran a SWOT analysis , realized that there were a number of specific campaigns that had been performing particularly well, and took it up a few notches.

The results? Well, we already told you that – big profits for the founders! Their story would not have happened if it had not been for the profit motive.

Launched in 2011, BarkBox exceeded $25 million in revenue in just two years of operating. In December 2020 they merged with Northern Star Acquisition Corp. and grew their value to roughly $1.6 billion.

How did this subscription-based business turn dog toys and snacks into such a success? Personalization!

Not only does each month’s box come with a variety of new doggy goodies, but the products are customized according to the size & breed, personal needs like allergies, and even behaviors. They’re able to provide such a great service by personally calling and emailing a select number of their customers each month.

The insights they gain from going the extra mile are what allow BarkBox to be such a strong brand within the pet supply arena. Their motivation? You guessed it: profits!

3. Dollar Shave Club

Also started in 2011, Dollar Shave Club was founded as a cost-effective alternative to purchasing expensive razor blades from the local pharmacy. A few short years later, they expanded their product line to include a broader range of men’s grooming supplies. By 2016, they were acquired by the industry giant Unilever for a whopping $1 billion in cash .

What does Dollar Shave Club do differently? A few things.

First, they make buying razors easier online than in-store. Second, they made their subscription plans flexible, and even offer their services to people who don’t shave! Go figure! Third, and perhaps most importantly, Dollar Shave Club invests real effort into retention.

They pay such close attention to keeping customers coming back that they’re able to retain a remarkable 1/4 of their subscribers for 4 years . For those of you not so literate in ecommerce metrics, that’s an outstanding retention rate. And it’s all thanks to their bottom line goal of – yes – seeking profit.

Profit Motive: 6 Best Ways to Increase Margins

Ok with a solid understand of profit motive under our belts, let’s look at six ways you can maximize your profits and scale your business:

1. Track profits & expenses

Getting a clear understanding of your store’s data can be difficult, particularly when you spend so much of your time taking care of day-to-day tasks. For those of you who run a Shopify store, the BeProfit profit tracker app is simply one of the best ways to improve your online business’s profits.

With BeProfit you can finally make sense of your data with an easy-to-digest dashboard that tracks and analyzes your business’s profits, expenses, and more. With the advantage of BeProfit, you can jumpstart your journey to become more profitable.

2. Reduce your overhead costs

Maximizing revenue and profits starts starts with knowing your overhead costs. These are expenses like domain hosting, utilities, insurance, shipping, transaction fees, equipment (and maintenance of it), and more. The costs included will vary depending on the type of e commerce revenue model you’re running, how long you’ve been operating, and so on.

Regardless of the specifics of your business, you should run an audit of your overhead costs and reduce them wherever possible (without making big sacrifices on your product or service quality).

3. Remove ‘unnecessary’ products or processes

You’ll always have some products that end up selling better than others. In fact, you may actually aim for that in order to nudge your customers to purchase more profitable items.

Just make sure that you’re not losing money by keeping stock of items that don’t sell! Review your inventory list and trim down on some of those ‘extra’ products that haven’t sold in a while. You can also replace them with other items that are cheaper to keep in stock.

4. Revise your pricing strategy

Whether you’ve been in business for a few months or a few years, it’s never a bad time to take another look back over your pricing strategy . When you first started you may have adopted a pricing strategy that sacrificed profits for better sales volume. As your business grew, you may have switched your pricing to be geared towards increasing average order value. And as your business got more mature, you may have reverted back to pricing strategies that are more competitive.

Wherever you are in your business journey, reviewing your store’s pricing is a good way to increase your profitability.

5. Smooth out operational wrinkles

Streamlining your business operations is closely related to cutting overhead costs. However, it applies more broadly across different aspects of your eCommerce store. The primary goal of streamlining is to reduce friction points that slow the gears of your business. Those friction points could include weak landing pages, poor customer support, long shipping times, problematic return processes, and so on.

Addressing those problem areas will have the secondary effect of reducing key performance metrics like:

- customer acquisition cost

- cost of goods sold

- customer churn rate, and so on – thereby increasing profit margins.

6. Increase customer retention

If you want to grow a profitable online business, it’s crucial that you know what your business’s repeat purchase rate is. More sales means more revenue, which ideally leads to more profit. Aside from that, increasing your number of repeat customers may also allow you to reduce your e-commerce marketing budget without having a negative impact.

Simply put, greater customer retention means more profit for your business.

What is Your Profit Motive?

The profit motive exists in each and every eCommerce business owner, whether they know it or not! Get familiar with knowing where the profit motive comes into play, how to employ it wisely, and which ways to increase profit. With those bases covered, you’ll set your business up for a grand slam.

Author Bio:

This is a guest post from Benjamin Shabat. Benjamin is a content specialist at BeProfit , where he works to deliver useful and relevant information to small online business owners. BeProfit is dedicated to helping e-commerce stores grow by giving them true control over their business’s data.

Relevant Blogs

eCommerce AI: 7 Ways Artificial Intelligence is Transforming eCommerce

.png)

The Impact of Post-Purchase Upselling in 2023 (Report)

The Best Products to Sell on Shopify: 13 Sure-Fire Ideas to Make Money in 2024

Start your free trial.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- US & World Economies

- Economic Terms

Profit, the Motive for Capitalism

2 Foolproof Ways to Increase Profit

Types of Profit

Profit formula, profit motive, two foolproof ways to increase profit, how profit drives the stock market, frequently asked questions (faqs).

Profit is the revenue remaining after all costs are paid. These costs include labor, materials, interest on debt, and taxes. Profit is usually used when describing the activity of a business. But everyone with an income has profit. It's what's left over after paying the bills.

Profit is the reward to business owners for investing. In small companies, it's paid directly as income. In corporations, it's often paid in the form of dividends to shareholders.

When expenses are higher than revenue, that's called a "loss." If a company suffers losses for too long, it goes bankrupt.

Key Takeaways

- Profit is the income remaining after settling all expenses.

- Three forms of profit are gross profit, operating profit, and net profit.

- The profit margin shows how well a company uses revenue.

- Profit drives capitalism and free-market economies.

- Increasing revenue and cutting costs increase profits.

Businesses use three types of profit to examine different areas of their companies. They are gross profit, operating profit, and net profit.

Gross Profit

Gross profit subtracts the cost of goods sold (COGS) from total sales. Variable costs are only those needed to produce each product, like assembly workers, materials, and fuel. It doesn't include fixed costs, like plants, equipment, and the human resources department. Companies compare product lines to see which is most profitable.

Operating Profit

Operating profit includes both variable and fixed costs. Since it doesn't include certain financial costs, it's also commonly called "EBITDA."

EBITDA (which excludes depreciation) is much more commonly used than EBITA, which includes depreciation.

That stands for Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortization . It's the most commonly used, especially for service companies that don't have products.

Net profit includes all costs. It's the most accurate representation of how much money the business is making. On the other hand, it may be misleading. For example, if the company generates a lot of cash, and it's invested in a rising stock market, it may look like it's doing well. But it might just have a good finance department and not be making money on its core products.

Companies analyze all three types of profit by using the profit margin . That's the profit, whether gross, operating, or net, divided by the revenue.

The profit margin reveals how well the company uses its revenue.

A high ratio means it generates a lot of profit for each revenue dollar. A low ratio means the company's costs are eating into its profits. Ratios differ according to each industry.

Profit margins allow investors to compare the success of large companies versus small ones. A large company will have a lot of profit due to its size. But a small company might have a higher margin, and be a better investment because it is more efficient.

Margins also allow investors to compare a company over time. As the company grows, its profit will grow. But if it's not becoming more efficient, its margin could fall.

Profit is calculated by the following formula:

π = R - C

- Where π (the symbol for pi) = profit

- Revenue = Price (x)

- C = Fixed cost, such as cost for a building +Variable cost, such as the cost to produce each product (x)

- x = number of units.

For example, the profit for a kid selling lemonade might be:

π = $20.00 - $15.00 = $5.00

- R = $0.10 (Price for each cup) (200 cups) = $20.00

- C = $5.00 (for wood to build lemonade stand) + $.05 (for the cost of sugar and lemons per cup)(200 cups sold) = $5.00 + $10.00 = $15.00

The purpose of most businesses is to increase profit and avoid losses. That is the driving force behind capitalism and the free market economy . The profit motive drives businesses to come up with creative new products and services. They then sell them to the most people. Most important, they must do it all in the most efficient manner possible. Most economists agree that the profit motive is the most efficient way to allocate economic resources. According to them, greed is good.

There are only two ways to increase profit.

Increase Revenue

Revenue can be increased by raising prices, increasing the number of customers, or expanding the number of products sold to each customer.

Raising prices will increase revenue if there is enough demand. Customers must want the product enough to pay higher prices. Increasing the number of customers can be expensive. It requires more marketing and sales. Expanding the number of products sold to each customer is less expensive. The trick is to understand your customer well enough to know which related products they might want.

Lowering costs is a good method up to a point. It makes a company more efficient and thus more competitive. Once costs are down, the business can reduce prices to steal business from its competitors. It can also use this efficiency to improve service and react more quickly.

The biggest budget line item is usually labor.

Companies that want to quickly increase profits will lay off workers. This is dangerous. Over time, the company will lose valuable skills and knowledge. If enough companies do this, it can lead to an economic downturn. There wouldn't be enough workers earning good wages to drive demand. The same thing happens when businesses outsource jobs to low-cost countries.

Profits are also known as "earnings." Public corporations that are listed on the stock market announce them every three months in quarterly reports. That occurs during earnings season . They also forecast future earnings.

Earnings season significantly affects how the stock market does. If earnings are higher than forecast, the company's stock price generally rises. If earnings are lower than expected, prices will generally drop.

Earnings seasons are especially important to watch in the transition phases of the business cycle . If earnings improve better than expected after a trough, then the economy could be coming out of the recession. It's headed into the expansion phase of the business cycle. Poor earnings reports could signal a recession .

What is the difference between revenue and profit?

Revenue is the total income that a company earns in a specific period. Profit is income minus expenses, operating costs, and debt payments.

Is profit the most important thing in business?

Various businesses will articulate profit's place in their overall mission differently. Regardless of where it fits into the mission statement, profit is fundamentally important for a business's success.

What is a profit and loss statement?

A profit and loss statement , typically known as a "P&L" or "income statement," is a summary of all of a business's income and expenses in a specific period. It's one of the most important financial documents a business generates, as it's regularly used by investors and managers to evaluate a business's financial health.

IG. " Earnings Season ."

Internal Revenue Service. " Business Activities ."

Planning for Profit: How to Build Profitability Models

If you want to understand the profitability of your business—now and for the future—you need forecasting methods that consider more than just revenue.

Profitability models matter for businesses of all sizes. They illustrate not only how you plan to drive revenue for your business, but how you will make it profitable.

You may be familiar with business models and revenue models, but less so with profitability models. So let’s dive into what a profitability model is, why it’s important, and how to create one.

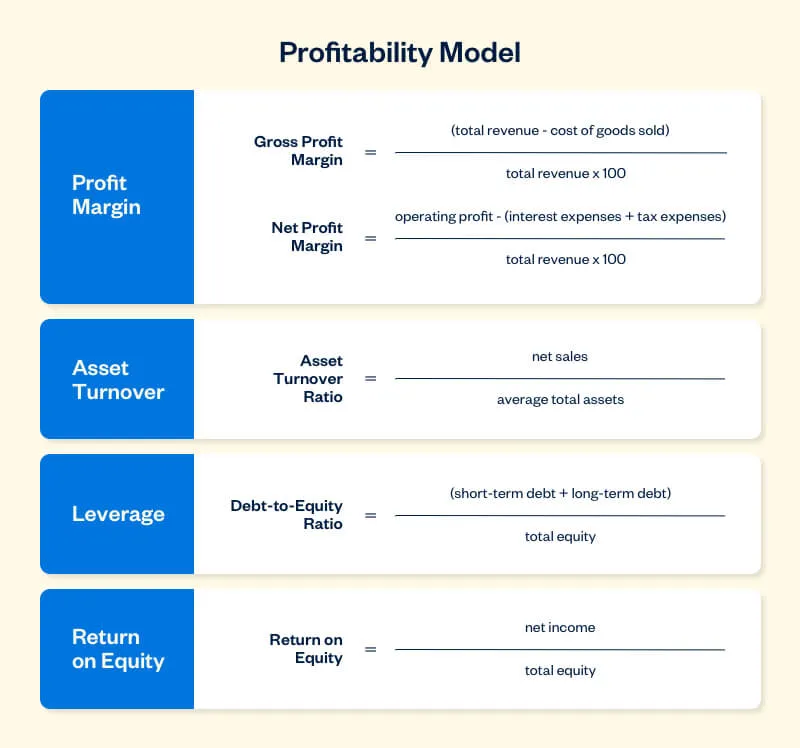

What Are Profitability Models?

A profitability model, or profit model, is a plan or prediction (based on financial data) for how your business will make a profit. It incorporates sales, cost of goods sold (CoGs), overhead (fixed and variable costs), other expenses, and debt.

A good profitability model can help you make financial forecasts and adapt to changing operating conditions. For instance, if you want to hire team members or you have to increase production costs, with a solid profitability model in place you can account for these variables and forecast your profit.

Related Articles

Profitability Model vs. Revenue Model

Revenue refers to your company’s total earnings, whereas profit is what’s left after you subtract costs from your sales total.

So, simply put, a revenue model explains your strategy for generating sales, without taking into account costs and liabilities.

Some businesses might choose to focus on a revenue model rather than a profit model if they’re setting aside their goal of earning a profit in order to grow their business. At those times, income streams and expansion opportunities may be more important.

Profitability Model vs. Business Model

Both revenue models and profit models are components of your broader business model.

A business model is a wide-ranging document that takes into account total earnings and profitability, but also other things like value proposition, competitive strategy, target markets, and potential problems and solutions. It can focus on growth only and not weigh heavily on profitability.

You’ll most often need a business model to get a loan or investors to put their money into your company.

How Do You Create a Profitability Model?

A profitability model is created in much the same way as a business model. But the components differ. The #1 thing to consider when drafting your profitability model is that you’re making multiple predictions based on potential changes in your revenue and costs.

This means you’ll be looking at what your revenue sources are, how you’ve structured your pricing, whether market saturation or capacity constraints impact your profit, and which fixed and variable costs your business has.

The best approach is to look at financial results on a quarter-by-quarter basis. This will give you an accurate look at how your profit has evolved.

What to Include in Your Profitability Model

The following are common core components of a profit model, and how to calculate them.

1. Profit Margin

Aiming for higher profit margins will result in a higher return on equity. There are several ways to calculate your profit margin.

2. Asset Turnover

Your asset turnover ratio gives you a clear picture of how efficiently you’re using your assets to generate sales revenue. For every dollar in assets, it shows you exactly how many dollars in revenue you’re generating.

asset turnover ratio = net sales ÷ average total assets

3. Leverage

To know how profitable you are, you’ll need to know how much debt you use to run your business in relation to your equity (assets minus liabilities).

debt-to-equity ratio = (short term debt + long term debt) ÷ total equity

4. Return on Equity

This financial ratio is a measure of your returns for creditors and investors. It indicates the success (or failure) of the business owner or owner’s investment in the business.

return on equity = net income ÷ total equity

To determine your current and past profitability , you can use our 5-step checklist . To keep track of your profitability on an ongoing basis, consider profitability reporting tools in FreshBooks. This will show you whether your billable projects are compensating for your investments.

What Are 3 Common Types of Profit Models?

Most businesses will want to look into one of the following 3 methods for predicting profitability.

1. Historical Model

The historical model implies looking at your past yearly growth rate to predict your company’s future profitability. For accurate results, you’ll want to consider possible future expenses that didn’t contribute to past data.

2. Analytic Model

3. Trends-Based Model

Market trends like new demands or changing customer views can impact your future profitability. Considering trends can make for a more accurate profit forecast. For example, if trends indicate more competitors could be taking some of your market share you’ll want to make some adjustments to your forecasts.

No one model works for every business at every stage. To find out which profitability model suits your business, consider hiring an accountant who offers these types of advisory and forecasting services.

Move From Profit Modeling to Profitability

Remember it can take a business as many as 2 to 3 years to become profitable. You may also need to change the model based on learnings from past profitability.

By taking into consideration costs and liabilities, and looking at different types of profitability models, you’ll have a much better picture of the steps you need to take to achieve your business goals.

Written by Alexandra Cote , SaaS Digital Marketer and Content Consultant

Posted on October 27, 2021

This article was verified by Janet Berry-Johnson , CPA and Freelance Contributor

Freshly picked for you

Thanks for subscribing to the FreshBooks Blog Newsletter.

Expect the first one to arrive in your inbox in the next two weeks. Happy reading!

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 9 min read

The Business Motivation Model

Preparing a resilient business plan.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Have you ever had to develop a business plan for your organization or for a new business?

If you have, then you know how difficult it can be to get it right. There are many different elements to consider, and it can be easy to overlook factors that may have a positive or negative effect on your success.

This is where it can be helpful to use the Business Motivation Model. This tool offers a practical way of sense-checking and optimizing your plan. By using it, you can develop a resilient business plan – one where you've explored the impact of internal and external influencers, and have adjusted the plan appropriately.

In this article, we'll look at what the Business Motivation Model is, and we'll explore how you can use it to improve business planning.

About the Model

The Business Motivation Model was originally developed by the Business Rules Group, a non-commercial consulting firm, in the late 1990s. Its goal was to help people prepare business plans in an ordered, efficient, properly-organized way.

Put simply, the Business Motivation Model helps you think about why you're creating a business plan, identify the essential elements that you need to include, and understand how all of these factors interact with one another. This helps you ensure that your business plan is robust and internally consistent, that it fairly explores the impact of the plan, and that it takes your business in a direction that is useful and valuable.

The model is not only useful for writing traditional business plans – you can also use it to plan projects and new processes.

The name of this model, "The Business Motivation Model," is not particularly helpful. Don't worry too much about this.

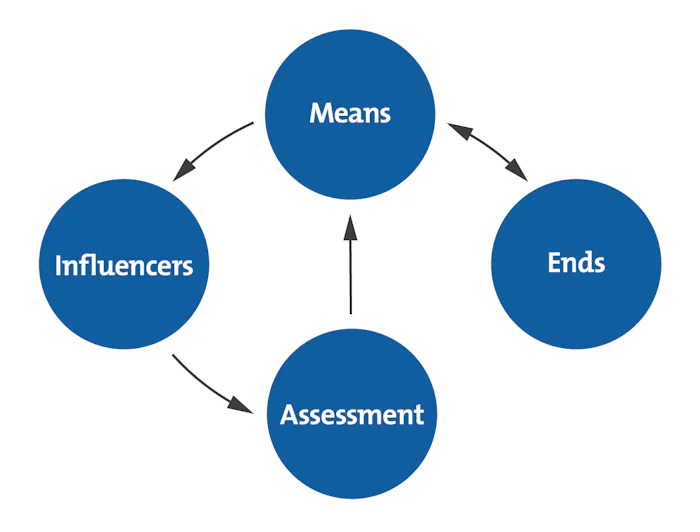

There are four main elements to the model:

- Ends: This is what you want to accomplish with your plan. "Ends" consist of a Vision, Goals, and Objectives. (These are defined in a slightly differently way from the vision, goals, and objectives that we describe elsewhere within Mind Tools – more on this later!)

- Means: These describe how you're going to achieve the Ends. They include your mission, your overall strategy, and the organizational policies and rules that will affect the achievement of your Ends.

- Influencers: This is where you assess the people or things, inside or outside your organization, that can affect your Ends or Means.

- Assessment: This is where you assess your Influencers, and then review and adjust your Ends and Means as necessary.

As you can see in figure 1, below, the model isn't linear – once you've analyzed and assessed Influencers, you review your Ends and Means, and update them until all elements are consistent and well-aligned.

Figure 1 – The Business Motivation Model

We'll now look into each element in more detail.

This is where you identify your final, desired result. You can start at this stage, but you'll probably find it more effective to work on your Ends and Means at the same time.

Begin by writing a vision statement . This is a human- or idea-centered statement that expresses what the organization wants to do or become in the long-term. Our article on Mission Statements and Vision Statements explores how to create powerful vision statements.

In this model, creating a mission statement comes under the Means, but it's often more effective to create mission and vision statements at the same time.

Goals and Objectives

You then need to set the Goals and Objectives that will help you achieve your vision.

In the Business Motivation Model, a Goal is long-term, qualitative (rather than quantitative), general (rather than specific), and ongoing. For example, "Answer telephone calls more quickly," or "Offer a friendly service to customers."

You must continually satisfy your goals in order to reach your Vision.

Objectives, on the other hand, need to be attainable , measurable , and time-based . For example, "By June 2014, we will answer 90 percent of telephone calls within 30 seconds," or "Within two years, we will achieve an average score of at least 85 percent on customer satisfaction surveys."

When achieved, these objectives will then help you reach your Goals.

The Means is the "how" of the model – how are you going to achieve the Ends you've identified?

Your Mission

To begin identifying your Means, write a mission statement . The purpose of this is to identify what you'll be doing on a day-to-day basis to achieve your Ends.

The model says that your mission statement should contain at least these three elements:

- An action part. For instance, "supply."

- A product or service part. For instance, "help-desk support."

- A market or customer part. For instance, "customers across North America."

For example, your mission could be "To provide IT help-desk support by telephone to customers in Canada and The United States."

You then need to develop and identify a Strategy for achieving your Ends. Don't skimp on strategy development – this is an extremely important process, and is key to the long-term success of your plan. (Our article on Developing Your Strategy looks in-depth at identifying, and then selecting, strategic options.)

At this stage, you'll also need to identify Directives. These are rules or organizational policies that will directly affect what you want to achieve.

For example, your organization may have a set budget for marketing that will affect how you build awareness for your brand, or your organization may only supply products to retailers within a 50-mile radius of its showroom. These would both affect your ability to compete in certain areas.

Remember that Directives can have a positive, as well as negative, effect on your overall plan.

3. Influencers

Here, you need to identify and assess your Influencers. These are people and factors that can affect your Means and End. They can be both internal and external to your organization.

Internal influencers can include:

- Infrastructure.

- Organizational values.

- Shareholders.

- Organizational culture.

External influencers can include:

- Technology.

- Business environment.

- Competitors.

- Media, and the wider community.

- Industry regulations.

- Government policies.

- Commonly-held assumptions.

To identify Influencers effectively, use PEST Analysis (to identify external factors) and Stakeholder Analysis (to identify the people who can affect your organization's success).

4. Assessment

Once you've created your list of Influencers, you then need to assess each one. Here, you look at each of your Influencers, and identify how they're going to impact your Ends and Means.

One way of doing this is to use SWOT Analysis – list each Influencer, then ask yourself whether they present a strength, weakness, opportunity, or threat to your Ends or Means. Then, identify the potential impact of Influencers that present a weakness or threat. (This can initially sound like a strange use of SWOT Analysis, but it's surprisingly effective.)

Tools such as Impact Analysis and Risk Analysis are great for helping you understand threats in more detail.

Once you've assessed each of your Influencers, review your Ends and Means, and update if appropriate.

Bear in mind that you may need to go through each element of the model several times, because any changes to one element will likely affect others. For instance, if you update your Ends, this will have a knock-on effect on your Means, and, possibly, your Influencers.

The Business Motivation Model helps you sense-check why you're creating a business plan, which elements you need to include, and how all of the factors within the plan relate to one another.

By using it, and by iteratively adjusting the plan to take account of the influences upon it, you can develop a more robust, resilient plan for your business – one that delivers the benefits that you want with a minimum of "unexpected" consequences.

There are four main elements to the Business Motivation Model:

- Influencers.

- Assessment.

Begin by identifying the Ends (your desired, end result) and your Means (how you're going to achieve this result).

Then, identify Influencers; these are any people or any things that could have an effect on your Means and Ends.

Last, you conduct an Assessment; this is where you judge your Influencers to determine what kind of impact they'll have on your Means and Ends. From there, you can review your Ends and Means, and update as required. Remember that you may need to work through each element several times.

The Business Rules Group (2010), 'The Business Motivation Model: Business Governance in a Volatile World,' Release 1.4.

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Entrepreneurial skills.

The Skills You Need to Start a Great Business

Understanding Business Acumen

How to Develop Your Business Instincts

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and save on an annual membership!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Better Public Speaking

How to Build Confidence in Others

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to create psychological safety at work.

Speaking up without fear

How to Guides

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 1

How do you get better at presenting?

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

The outsiders.

Will Thorndike

Expert Interviews

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Brought to you by:

Strategy Execution Module 5: Building a Profit Plan

By: Robert Simons

This module reading describes how to build a profit plan to reflect the strategy of a business in economic terms. After introducing the profit wheel, cash wheel, and ROE wheel, the module illustrates…

- Length: 34 page(s)

- Publication Date: Oct 6, 2016

- Discipline: Strategy

- Product #: 117105-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

This module reading describes how to build a profit plan to reflect the strategy of a business in economic terms. After introducing the profit wheel, cash wheel, and ROE wheel, the module illustrates how to use a profit plan to assess the viability of different strategies and evaluate whether sufficient resources will be available to implement the chosen strategy. The module examines in detail how to develop accurate estimates for sales, profit, cash flow, asset turnover, investment in new assets, and return on equity. The discussion then turns to how to gather and analyze data and the effects of sensitivity analysis on predictions. The module concludes by illustrating the critical role of a profit plan in setting goals, communicating expectations to the investment community, and evaluating the performance of individual managers and businesses. While this module is designed to be used alone, it is part of the Strategy Execution series. Taken together, the series forms a complete course that teaches the latest techniques for using performance measurement and control systems to implement strategy. Modules 1 - 4 set out the foundations for strategy implementation. Modules 5 - 10 teach quantitative tools for performance measurement and control. Modules 11 - 15 illustrate the use of these techniques by managers to achieve profit goals and strategies. View the full Strategy Execution series at: hbsp.harvard.edu/strategy-execution .

Learning Objectives

Demonstrate how to build a profit plan-the primary tool that managers use to describe their business strategy in economic terms. Explore the three wheels of profit planning: the cash wheel, the profit wheel, and the ROE (return on investment) wheel. Show how managers develop the wheels and how they are used to set goals, track performance, and make decisions. Explain how the profit wheels can be used to test the company's strategy.

Oct 6, 2016 (Revised: Feb 22, 2019)

Discipline:

Harvard Business School

117105-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Owning a business is an exciting journey filled with highs and lows. Establishing a clear, profit-driven strategy is one key factor that can tilt the scales toward success. The recent tax court case, Gregory v. Commissioner, highlighted how blurring the lines between hobbies and genuine business ventures can have significant financial implications. Not only did this case underscore the importance of clear delineation, but it also highlighted the potential tax pitfalls of not doing so. In this article, we’ll cover how to ensure your venture is seen as a legitimate business and not just a pricey pastime.

Understanding the Hobby Loss Conundrum

The “hobby loss” rules have made waves in the tax world, affecting many business activities, from horse breeding to charter boat operations and even Airbnb rentals. Only activities classified as what the IRS refers to as “engaged in for profit” are able to deduct expenses associated with the work. In other words, to be considered “engaged in for profit” means you set out with the intention of your business and activity to generate a profit. If the IRS determines the activity was not “engaged in for profit,” your ability to deduct associated expenses will be impacted. If your venture is potentially labeled a hobby, you could find yourself in a situation where you’re reporting full income without the benefit of crucial deductions.

In the case of Gregory discussed above, the business owner reported gross income equaling the business expenses, yet he couldn’t use the deductions due to the hobby classification. As a result, the ruling reduced his profit and increased the business’s taxes due, which is not the ideal scenario for any business owner.

Establishing a Profit Motive

The U.S. Tax Court and the Internal Revenue Service use a range of factors to determine whether a business truly has a profit motive. Remember, while starting a business around your passion is fantastic, the profit motive is what separates it as a sustainable business rather than an expensive hobby.

Four steps can make it a clear and recurrent theme in your business strategy.

- Clear Records: Maintain precise and consistent bookkeeping. Separate business from personal expenses and keep a dedicated business bank account. This is more than just good practice; it’s a way to show that you operate in a business-like manner.

- Consult the Experts: Engage with industry consultants and tax professionals. Their insights can help steer your ship clear of any hobby loss icebergs, and even a history of losses can be justified if you have expert testimonies or guidance.

- Adapt and Thrive: Continually evolve your business strategy to ensure profitability. Being adaptable is key in the ever-changing world of business. This means adapting your operations and ensuring legal formalities and structures are in place.

- Written Plans are Gold: Experience suggests a documented plan to achieve profitability may be a game-changer. This isn’t just paperwork—it’s a roadmap to success and could be your best defense against being recharacterized as a hobby.

Why This Matters to Business Owners

When your business displays a consistent profit-driven strategy, you’re protecting yourself from potential tax pitfalls and setting your venture up for long-term success. Adhering to these guidelines reflects solid business judgment that can benefit your company in the long run. Remember the consequences: a misclassified hobby can lead to reporting full income without deducing the expenses.

Take the Next Step

Are you currently engaged in a business activity that could toe the line between hobby and legitimate venture? Chat with your tax advisor. Discuss your profit-driven strategies and plans, taking lessons from the Gregory case. Continual reflection and adaptation, even in the face of enjoyable or recreational activities, are the keys to solidifying your business’s market placement.

The line between passion and profit is a fine one. Yet, with a clear, profit-driven strategy and awareness of nuances like the “hobby loss” rules, you can ensure your business thrives in today’s competitive marketplace. Stay informed, stay adaptable, and always keep that profit motive at the forefront of your business operations.

Treasury Circular 230 Disclosure

Unless expressly stated otherwise, any federal tax advice contained in this communication is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used or relied upon, for the purpose of avoiding penalties under the Internal Revenue Code, or for promoting, marketing, or recommending any transaction or matter addressed herein.

- CEO and Chairperson

- Focal Points

- Secretariat Staff

Stakeholder Engagement

- GEF Agencies

- Conventions

- Civil Society Organizations

- Private Sector

- Feature Stories

- Press Releases

- Publications

The purpose of business? It’s not just about money

By André Hoffmann, vice-chairman, Roche Holding Ltd

Business has shaped the world in pursuit of profit and growth with an apparent disregard for consequences, other than financial ones. The process of value creation has been extraordinarily successful in creating wealth through satisfying consumers’ needs and wants. The world’s fortune is at a historical peak: its economy has never been so highly valued. So, by some measures, the model can be considered a success. But at what cost?

It is increasingly evident that the focus on profitability has led to the neglect of two other dimensions: the environment and the fabric of society. We are rapidly losing species and natural areas. Income inequality is rising, with the latest figures showing a historic high. The world is getting richer, but its wealth is not properly redistributed.

The UN millennium goals were successful at lifting more than a billion people out of extreme poverty, and have been succeeded by the sustainable development goals, which provide us with a framework for building a better world. But, while such goal setting remains a successful mechanism, there is more to do.

A sole focus on short term gains will not drive the change we need. We must think in the longer term. This is particularly important in a one planet system. Where will growth come from when planetary boundaries have been reached?

Nobody likes business any more. The profit motive, once a desirable incentive to wealth creation, is now seen as something evil, and a source of injustice and inequality. There is a need to change the model, an imperative to reassess the purpose of business, not just to satisfy shareholders and accountants but also to work in tune with all relevant stakeholders.

The successful company is no longer one that just makes money. A financial return is a necessary condition, but it is not sufficient. Dividends will keep shareholders happy but what about other stakeholders?

We have to remember that a company is not just a balance sheet. It is also customers, local and global communities and society – and the natural environment, the world in which we live. These long neglected factors must be carefully considered.

So, there is a need for change. True sustainability will only be assured if there is a proper investment return in the three dimensions of business: financial, social and environmental.

This intuitive finding has long been around, but few companies have been able to implement it. Financial markets focus exclusively on financial reporting. If all that matters is immediate profitability how can one justify investing in long term projects? In a family-owned enterprise, trans-generational value creation may come naturally. But this is difficult to replicate in a publicly quoted company where the voice of owners is only answered in term of dividends.

Companies and their performance should be evaluated in terms of their net contribution to society, giving back at least as much as they take. There are many ways in which they can do this. Training employees, promoting ethical values, integrating ethnic minorities and ensuring fair pay for all are only a few of the obvious activities which need to be recognised and valued. In environmental terms, reducing ecological footprints and better managing consumption and the natural resources cycle could work as useful metrics, among many others.

None of this is rocket science, but it is usually met with stock answers such as “we cannot afford it” or “shareholders would not approve, as it has an impact on the margin”. I would argue that we cannot afford not to make the change if we care about people and planet as well as profit.

These transformational changes will not take place without the emergence of a new generation of leaders able to change the current management paradigm. Under such enlightened stewardship, companies will again be able to thrive in the dual and common interest of humanity and the planet and evolve a more appropriate response to the current world challenges.

The new technology tsunami, currently underway, could provide an opportunity for a successful reboot. Its disruption to the existing business model must be harnessed for good. If instead it is just seen as a new opportunity for business as usual the situation will become even worse. Company management should be rewarded along the lines of people, planet and profit.