- Open access

- Published: 18 August 2021

An evaluation of the process of informed consent: views from research participants and staff

- Lydia O’ Sullivan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7131-5048 1 , 2 ,

- Laura Feeney 1 ,

- Rachel K. Crowley 1 , 3 ,

- Prasanth Sukumar 1 ,

- Eilish McAuliffe 4 &

- Peter Doran 1 , 2

Trials volume 22 , Article number: 544 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

11 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

The process of informed consent for enrolment to a clinical research study can be complex for both participants and research staff. Challenges include respecting the potential participant’s autonomy and information needs while simultaneously providing adequate information to enable an informed decision. Qualitative research with small sample sizes has added to our understanding of these challenges. However, there is value in garnering the perspectives of research participants and staff across larger samples to explore the impact of contextual factors (time spent, the timing of the discussion and the setting), on the informed consent process.

Research staff and research participants from Ireland and the UK were invited to complete an anonymous survey by post or online (research participants) and online (research staff). The surveys aimed to quantify the perceptions of research participants and staff regarding some contextual factors about the process of informed consent. The survey, which contained 14 and 16 multiple choice questions for research participants and staff respectively, was analysed using descriptive statistics. Both surveys included one optional, open-ended question, which were analysed thematically.

Research participants (169) and research staff (115) completed the survey. Research participants were predominantly positive about the informed consent process but highlighted the importance of having sufficient time and the value of providing follow-up once the study concludes, e.g. providing results to participants. Most staff (74.4%) staff reported that they felt very confident or confident facilitating informed consent discussions, but 63% felt information leaflets were too long and/or complicated, 56% were concerned about whether participants had understood complex information and 40% felt that time constraints were a barrier. A dominant theme from the open-ended responses to the staff survey was the importance of adequate time and resources.

Conclusions

Research participants in this study were overwhelmingly positive about their experience of the informed consent process. However, research staff expressed concern about how much participants have understood and studies of patient comprehension of research study information would seem to confirm these fears. This study highlights the importance of allocating adequate time to informed consent discussions, and research staff could consider using Teach Back techniques.

Trial Registration

Not applicable

Peer Review reports

Informed consent depends on disclosure of pertinent information, capacity to give consent and a voluntary decision [ 1 , 2 ]. In the clinical research context, the research participant must freely give their informed consent prior to enrolment onto a clinical trial or research study [ 3 ]. While the Participant Information Leaflet (PIL) provides a record of the information disclosed and the informed consent form (ICF) records the participants’ written decision to take part, it is nevertheless recognised that informed consent is a process [ 4 , 5 ], rather than a single event enabled solely by paper or electronic documents. This process involves the researcher approaching the prospective participant, providing some initial information about the research study, and as this information is processed, responding to questions and adjusting the level of information to fit the needs of the individual. The process of informed consent often involves building rapport and trust with the prospective participant and should respect cultural and societal norms, such as involving family members or friends. Finally, once it is evident that the individual has adequately understood the study or trial, they make an informed choice about whether they wish to participate. If they have decided to participate, the participants typically sign a consent form and are given a copy of the signed form and the study/trial information to take away with them. However, while researchers agree that maintaining participant autonomy and supporting their decision-making is important, much debate remains on how the informed consent process can be measured and optimised [ 6 ].

A number of studies report that most research participants are satisfied with the information provided to them [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. However, there is also ample evidence of participants misunderstanding critical information for good quality consent, such as the risks and the methodological design of the study [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. It is also recognised that the process of informed consent is complex; for example, the language used during the informed consent process and in the PIL/ICF documents can be too difficult for participants to understand [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, while it is the researcher’s responsibility to provide the relevant information to the participant, the available evidence suggests that participants’ information needs can vary considerably [ 16 , 17 ], though the reasons are not fully understood. Research participants are often unwell when enrolling in a study and therefore their capacity to absorb information may be diminished, putting them at greater risk of misunderstanding some element of the research study [ 10 , 18 ].

The process of informed consent can be challenging for researchers also. Studies aimed at understanding the consent process from the investigators’ perspective report that the lack of time and difficulty communicating complex concepts are barriers when facilitating informed consent discussions [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Several studies also suggest that investigators felt that there was a conflict between their dual role as both a researcher and a clinician [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]—investigators recognised the need to generate data to improve treatments but were also concerned about minimizing risks of experimental treatments to individual participants. Analyses of informed consent discussions and interviews with investigators indicate that investigators seldom confirm a patient’s level of understanding at any point during the conversation [ 25 , 26 ]. Despite this, it seems that investigators remain concerned or in some cases uncertain about how well their patients have understood the study [ 7 , 23 ]. Several studies have also indicated that many research staff do not receive training on how to facilitate an optimal informed consent discussion [ 5 , 27 , 28 ]—this may affect the experience for both staff and participant.

In aggregate, the above studies indicate that the process of informed consent is not straightforward and many factors influence both the participant’s and the investigator’s experience. However, few or no studies have sought to quantify how clinical research participants and staff experience the process of consent and the importance of contextual factors such as the time spent, the setting of the informed consent discussion and the timing at which the participant is approached. Given this gap in our understanding, the aim of this study is to describe how participants and research staff experience the informed consent process and the contextual factors that contribute to their satisfaction with the process.

Survey design and piloting

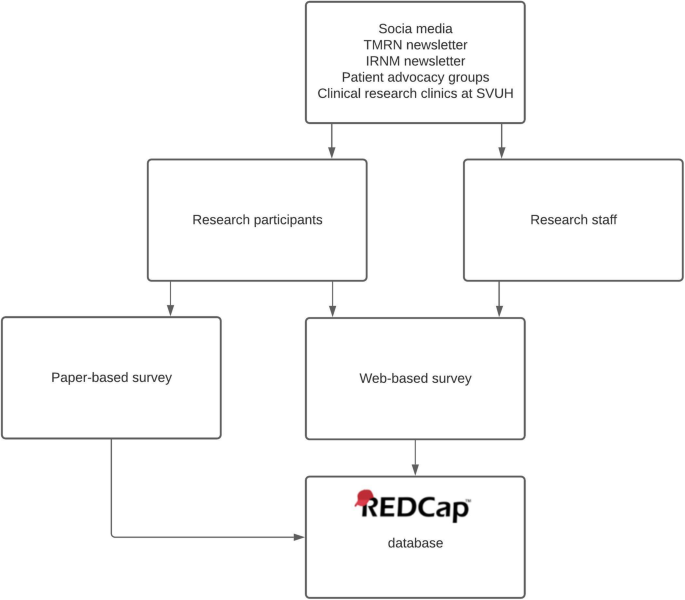

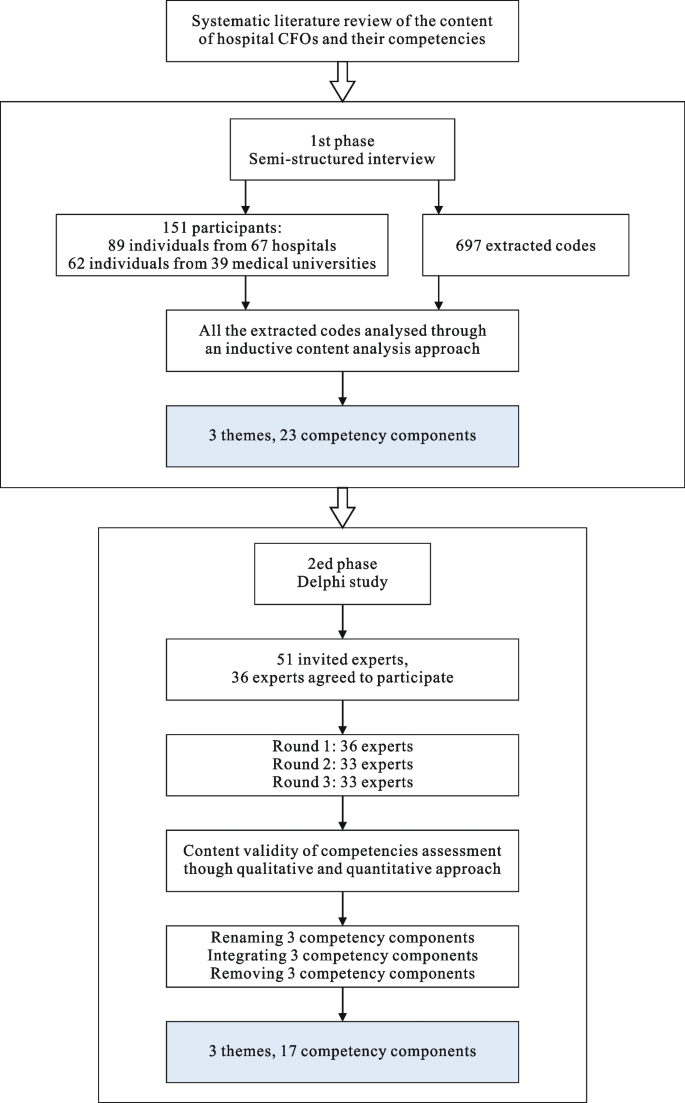

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [ 29 ]. Two anonymous surveys were designed to meet the objectives of the study—one for participants (see Additional file 1 ) and one for research staff (see Additional file 2 ). The survey for research participants contained 14 multiple choice questions; the survey for research staff contained 16 multiple-choice questions. Both surveys included an optional, open-ended question for respondents to add any additional opinions related to the topic. Figure 1 illustrates how the survey data were collected and stored. For research participants, a matched paper and electronic version of the survey were available. This maximised accessibility for respondents who may not have access to an electronic device or prefer to complete surveys on paper. To allow for participants who had taken part in more than one study or trial, participants were asked to answer the survey based on the most recent study or trial they were consented to. For research staff, an online survey was exclusively used. In order to record their most usual consent practices, research staff were not asked to answer the survey based on their most recent consent discussion, except for one question about the duration of their last consent discussion. Attempts were made to mitigate acquiescence bias (the tendency of responders to provide positive responses) by including Likert scales, neutral questions and options such as ‘I can’t remember’. Both surveys were piloted among six members of the target groups and the wording of the surveys was adjusted following their feedback, to ensure that the questions were clear. Piloting indicated that the surveys took an average of 5 min to complete. Full ethics approval was granted by the Saint Vincent’s Healthcare Group Ethics and Medical Research Committee, Dublin 4, Ireland; Ref: RS20-026. A low-risk ethics exemption was also granted by the University College Dublin Research Ethics Committee; Ref: LS-E-20-117-OSullivan-Doran.

Flowchart describing the dissemination of the surveys. TMRN Trials Methodology Research Network, IRNM Irish Research Nurses and Midwives Network, SVUH Saint Vincent’s University Hospital

Convenience sampling was used. Research participants were eligible to complete the survey if they were > 18 years old and had taken part in a research study in Ireland or the United Kingdom (UK). Research staff were eligible to complete the survey if they facilitate informed consent discussions with an adult, lay research participants in Ireland or the UK. Due to restrictions in place because of the COVID-19 pandemic, some hospital clinics were being conducted by phone, which restricted the distribution of paper surveys. After discussion with the lead research nurse, it was decided that 200 paper surveys could be distributed during the data collection period. Therefore, 200 existing research participants in a single hospital, affiliated with the host university, were offered a paper-based survey by their clinical or research team (research nurse, investigator or clinician) at their routine, in-person, research or clinical visits, with an information leaflet and a stamped addressed envelope to return the survey. This method was used to facilitate participants who prefer a paper-based survey, in order to encourage responses. The surveys were distributed in dermatology, respiratory, oncology, rheumatology, infectious diseases and endocrinology clinics. Requests for research staff were also made via social media (Twitter, Linked In), via the Health Research Board-Trials Methodology Research Network and Clinical Research Coordination Ireland newsletters, and the Irish Research Nurses and Midwives Network. A digital marketing strategy was used to promote the survey to research participants on social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and through Irish and UK patient advocacy groups. Respondents were also asked to forward the survey to relevant contacts (chain referral sampling). Chain referral sampling provides a swift and cost-effective method of data collection, while ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of prospective respondents [ 30 ]. Due to this method of sampling, it is not possible to accurately estimate the response rate for the online version of the survey. However, the response rate was recorded for the paper-based surveys. Responder bias was minimised by using very short [ 31 , 32 ] and anonymous [ 33 ] surveys. Social desirability bias was minimised by ensuring that research participants returned the survey by post and not to their healthcare or research teams, or by completing the survey online. Respondents were advised in the information provided (either in paper version or on the online survey cover page) that by completing and submitting/returning the survey they were indicating their consent to take part (see Additional Files 3 and 4 ). Data collection took place between September 2020 and February 2021.

Study data were managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (REDCap 7.4.10, 2019) tool hosted at University College Dublin [ 34 , 35 ]. For the online surveys, responses were inputted directly into REDCap by the respondents. For the paper surveys, the participants’ responses were manually inputted into REDCap by a single researcher (LOS). The same researcher reviewed the data entry for a random 20% of surveys, selected using Microsoft Excel, after an interval of 3 months to ensure accuracy in data entry.

Close-ended questions

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the following characteristics:

The research participants’ level of satisfaction with the time, timing, location, level of information and explanation provided

The research staff’s level of experience, the training provided to them (if any), approach taken when facilitating informed consent discussions, time spent, confidence level, perceived barriers.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Open-ended questions

Responses to the single, optional, open-ended question were extracted—every effort was made to include the verbatim text, but where necessary, some details were omitted to ensure confidentiality. The responses were analysed independently using a thematic approach [ 36 ] by two researchers (LOS and PS). An experienced qualitative researcher (EMcA) reviewed the extracted codes against the quotations to ensure consistency. The consensus was then reached between the two researchers on the extracted themes.

This study is reported in accordance with the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) [ 37 ]—the completed checklist is contained in Additional File 5 .

Research participants

One hundred sixty-nine research participants completed the survey. The response rate for the paper-based survey for research participants was 24% (47 out of 200 offered the survey). The remaining responses were to the online survey. Missing fields were denoted in the results by ‘Didn’t Answer’. Table 1 shows the length of time since the participant signed the consent form and whether they felt the location was comfortable and private. Most participants reported having signed the consent form over a year ago (91 or 45%) or in the last year (30 or 18%). Most participants (160 or 95%) felt the location where they signed the consent form was both comfortable and private. In terms of how participants were informed about the study/trial, the majority of participants (137 or 81%) reported that they were given a verbal explanation by the research team, while only 9 (5%) had watched a video or looked at a website about the research study or trial. Overall, 99 (59%) were Very Satisfied and 59 (35%) were Satisfied with their experience of informed consent. The mean time taken for the research participant’s last informed consent discussion was 51 min (range: 1–300 min; median: 30 min)—see Fig. 2 .

Time taken for informed consent discussion, reported by research participants

Table 2 below indicates that most research participants (149 or 88%) indicated that the time given by the research team to explain the study or trial was about right. The majority of participants also indicated that timing (the day on which they were approached with the study/trial) was a good (74 or 44%) or alright time (41 or 24%). Nearly a third of participants (45 or 27%) responded that the timing would not have made any difference to them. Most respondents (155 or 92%) also felt they had enough time to decide if they wanted to take part.

Table 3 reports how respondents felt about the information, explanation and written information provided to them. The majority of respondents (93%) reported that the amount of information given to them about the study/trial was about right. Similarly, participants said the study/trial was explained to them very well (100 or 60%) or fairly well (58 or 34%). Participants felt that the Participant Information Leaflet was Very Easy (48 or 29%) and Easy (71 or 42%) to understand.

One hundred and forty (83%) participants were encouraged to ask questions during the consent process and 126 (74%) felt that their questions were answered well. Most participants were positive about how well they had understood the study/trial: Very Well 76 (45%), Well 46 (28%) and Fairly Well 34 (20%).

Optional open-ended question

Seventy research participants responded to the optional, open-ended invitation to add any other feedback. The full list of quotations is included in Additional File 6 . The following three themes emerged from these responses:

Reports of positive experiences with the research team.

The value of allowing sufficient time for the participant to consider the study/trial, including time for questions. This may include providing information to the participant in advance of the clinic visit.

The importance of having follow-up after the study/trial has ended, e.g. to be given the results of the trial.

Two sample quotations for each theme are included below:

Research participant 022: ‘ [X Nurse], [X Hospital] is excellent, very helpful and so pleasant to deal with. She explains everything clearly and makes sure all your questions are answered. I know she's always on the end of the phone if needed, which gives me great peace of mind. 10/10’

Research participant 026: ‘ The research staff were very encouraging and open. I felt very involved in the process’.

Research Participant 009: ‘They emailed the document to me before went for study visit. This was really helpful to consider info in my own time in my own surroundings. This meant time could be spent asking for clarification on areas of concern during the meeting without feeling rushed in any way’.

Research participant 068: ‘The research study was introduced during a hospital/clinic appointment. I think that a prior notification that this would happen would have been useful. Normally at a hospital appointment, I would already have questions to ask and information to clarify. So the additional information about research can be difficult to process on day. Prior notification would allow the patient time to mentally prepare, and on a practical note allow them to allocate extra time for hospital visit’.

Research participant 032: ‘Would like to know how the initial results of the trial going’.

Research participant 051: ‘ I would have liked some feedback from the researchers’.

In summary, research participants were positive overall about their experiences of the informed consent process, the time allocated to the process, the amount of information given to them, the environment in which their consent was sought and how well they felt they had understood the study or trial. However, two interesting themes which emerged in response to the open-ended question were the need to allocate sufficient time to the informed consent process and the importance of follow-up or feedback once the trial has finished.

Research staff

One hundred fifteen research staff completed the survey; Fig. 3 and Table 4 describe this cohort. Respondents identified themselves primarily as (respondents could select more than one response):

Research Nurses or Research Midwives (53 or 46%)

Study Coordinators (31 or 27%)

Principal Investigators (22 or 19%).

Research staff—roles of respondents (respondents could select more than one response)

The majority of respondents carried out informed consent discussions in hospitals (99 or 86%). Respondents worked on Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal Products (CTIMPs) (83 or 72%), Observational studies (75 or 65%), Translational/Biomarker/Biobanking studies (63 or 55%), Registry trials (40 or 35%), non-CTIMP intervention (surgery, psychology, physiotherapy, radiotherapy, etc.) (45 or 39%) and Medical device studies (17 or 15%). The majority of respondents were experienced: 69 (60%) having greater than 5 years and 13 (11%) having 3–5 years of experience facilitating informed consent discussions. Most research staff (74 or 64%) of research staff had received training on how to facilitate informed consent discussions while 38 (33%) had not. Of those who had received training, 45 (58%) had formal/structured training, 41 (55%) observed a senior colleague and 39 (53%) had informal ‘on-the-job’ training (respondents could select more than one answer). Just over one third of research staff (36 or 31%) had received two forms of training while 23 (20%) of respondents had received all three forms of training. The mean time taken during research staff’s last informed consent discussion was 28 min (range: 3–120 min; median: 20 min)—see Fig. 4 .

Time taken for informed consent discussion, reported by research staff

Table 5 reports the difficulties with the informed consent process as reported by research staff. Respondents felt that the PIL/ICF was too long and/or too complex (72 or 63%), the difficulty for participants to understand complex information (64 or 56%), time pressures (46 or 40%), difficulties explaining complex information (44 or 38%), participants being anxious or upset (32 or 28%) and other difficulties (11 or 11%) or no difficulties (4 or 3.5%). In terms of how difficult PILs/ICFs are for participants, 9 (8%) rated them as ‘Very hard’, 44 (39%) as ‘Fairly Hard’, 43 (37%) as ‘Fairly Easy’, 13 (11%) as ‘Easy’, 0 (0%) as ‘Very Easy’ and 6 (5%) did not reply. Research staff reported the following as factors which would deter them from approaching a potential participant:

Patient is too anxious or upset (55 or 48%)

Patient does not have enough time (52 or 45%)

Patient has already received too much information at this visit (44 or 38%)

Do not think participant will understand the study/trial (32 or 28%)

Do not have enough time in clinic (31 or 27%)

Other (21%), did not reply (8 or 7%)

Not applicable—all eligible patients approached (3 or 2.6%)

Table 6 details the approach taken by research staff during the informed consent process: 105 (91%) explain the study verbally, 97 (84%) give participants a PIL and ask them to read it, 55 (48%) read the PIL to participants, 7 (6%) show a participant a video or website and 12 (10%) do ‘Other’, including providing initial information and then following up, working with a translator and summarising important information. Research staff followed a structured approach (i.e., following a checklist or the structure of the PIL): all the time (40 or 35%), often (36 or 31%), occasionally (16 or 14%), never (17 or 15%) and did not reply (6 or 5%). Most research staff (108 or 88%) reported that they check participants’ level of understanding prior to consent, 5 (6%) reported that they did not and 5 (6%) did not answer the question. For those who do check participants’ level of understanding, 88% ask participant if they have understood, 89 (35%) ask the participant to ‘teach back’ or ‘talk back’, 93 (81%) encourage participants to ask questions, 6 (6%) reported using other means, while 2 (2%) did not reply.

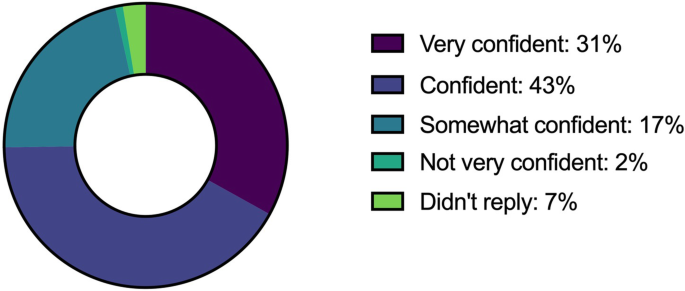

Figure 5 provides an overview of the confidence level of research staff to facilitate a good informed consent process. Respondents were ‘Very confident’: 36 (31%), ‘Confident’: 49 (43%), ‘Somewhat confident’: 20 (17%), ‘Not very confident’: 2 (2%), ‘Not at all confident’: 0 (0%) and Did not reply 8 (7%).

Research staff—confidence level in facilitating informed consent discussions

Table 7 shows the factors which research staff felt would improve the informed consent process for participants: shorter/simpler PIL: (86 or 75%), a PIL with simple diagrams or pictures (68 or 59%), resources like an app or video (56 or 49%), more time with the participant (54 or 47%) and more time with another member of the research team (29 or 25%). Other responses included a quiet, dedicated, uninterrupted space (6 or 5%), PIL with less GDPR information (2 or 2%), PILs in other languages (1 or 0.8%) and miscellaneous (3 or 3%).

Thirty research staff responded to the optional, open-ended request to add any other feedback. The full list of quotations is included in Additional File 7 . A very dominant theme emerged: research staff feel that the time and resources, particularly space, are important to facilitate a good informed consent process and these factors are often limited in supply. The following sample quotations illustrate this theme:

Research staff 003: ‘As a researcher, it feels like the definition of informed consent is constantly changing, the bar is always going up. This is of course, a good thing. But the consequence is the need to have ongoing dialogue. This requires significant resources that the system is not currently providing.’

Research staff 008: ‘Research staff often struggle for dedicated space to conduct informed consent and this can add unnecessary stress and burden to the process. Clinical trials personnel should have dedicated areas for completing this important process with appropriate resources and time availability.’

Research staff 012: ‘Resources badly needed. Dedicated trial clinics. Protected time.’

Research staff 015: ‘Discussing consent in a busy clinical environment is very difficult.’

Three additional themes emerged:

Consent process can be challenging; training on how to facilitate is needed

Technology could be used to improve the informed consent process

An accessible PIL/ICF is important; GDPR/data protection information is often too long, too complicated

Research staff 029: ‘I have had many challenging discussions with collaborators around rates of recruitment which may be lower than others but at least I know I am running my studies with the highest ethical standards….it can be very hard though!’

Research staff 008: ‘Research staff should have more formalised training in the trial and consent process.’

Research staff 005: ‘We need greater facilitation of remote consent (telephone etc.) especially with lack of visiting due to COVID.’

Research staff 028: ‘The issue of informed consent, and electronic consent, is increasingly relevant with the COVID-19 pandemic.’

Research staff 007: ‘PILs much too complex particularly with data protection which patients find cumbersome and excessive.’

Research staff 018: ‘Info leaflets are getting more complicated with GDPR/data protection information. It is almost impossible to make it shorter without risking rejection by ethics committee.’

In summary, research staff in this study reported good levels of experience and confidence in facilitating informed consent discussions. Research staff indicated that a shorter, simpler PIL/ICF or a PIL/ICF with diagrams, the use of technologies and additional time with participants would improve the overall informed consent process.

Summary of key findings

This study quantified a number of factors which are vital to the informed consent process, from the perspectives of both research participants and research staff. Research participants were generally positive about each aspect of the informed consent process explored in the survey. However, they did highlight the importance of having sufficient time and the importance of providing follow-up once the study/trial concludes, e.g. providing the results to research participants. Research staff reported that they felt quite confident with the process of informed consent overall, possibly reflecting that the respondents in this case were generally experienced in facilitating informed consent discussions. Barriers to the informed consent process noted by research staff included lengthy, complex PILs/ICFs, difficulties communicating complex information and time constraints.

Participants report positive experience but have they understood?

Research participants in this study overwhelmingly reported a positive experience of the informed consent process and high levels of understanding of the trial or study. This correlates well with previous studies reporting high levels of satisfaction among research participants [ 9 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]. It is encouraging to report that the majority of research participants are happy with their experience of the informed consent process, which is testament to the dedication and commitment of research staff. However, other studies consistently demonstrate that when research participants are assessed, they often have a poor understanding of key parts of the study or trial [ 42 , 43 ]. Hietnen’s survey of 261 participants in an oncology trial indicated that while 91% of participants were satisfied with the difficulty level of the information given, 51% had misunderstood randomisation [ 44 ]. It is also concerning to note that Pope et al.’s study found that participants who reported to have received the ‘right amount of information’ were unfortunately not found to have a higher level of understanding of blinding [ 9 ]. Studies have shown the participants’ information needs vary considerably [ 16 , 17 ], and it is possible that research participants feel that they have gained sufficient knowledge to make a decision without understanding key aspects of the trial. However, this jars with the doctrine of informed consent, which states that participants must be informed about the pertinent information prior to providing consent [ 45 ].

The importance of adequate time and resources

Research staff consistently reported in this study that they felt that time and resources such as space were limiting factors in their ability to facilitate an optimal informed consent process—40% reported that time pressures were a difficult component of the informed consent process and 47% felt that more time would improve the informed consent process for participants. This finding also emerged in the responses to the open-ended question from both research staff and research participants. Spaar et al. similarly reported lack of time as the biggest barrier to the process of recruitment to randomised trials [ 20 ]. This is of concern, since two systematic reviews identified additional time as one of the few factors which has been shown to significantly improve participants’ understanding [ 46 , 47 ]. Studies by Aaronson [ 48 ] and Tindall [ 49 ] both found that an additional conversation with a member of the research team improved participants’ understanding. Research participants in this survey study also noted in the open-ended question that it may be helpful to receive the information about a trial in advance of the consent discussion with the research staff, in order to have additional time to consider the information.

The Participant Information Leaflet/Informed Consent Form

Sixty-three percent of research staff in this study felt that the PIL/ICF is too long and complex and 75% reported that a shorter and simpler document would improve the informed consent process. However, it is interesting that research participants did not share the same view, with the majority stating they felt the PIL/ICF was Very Easy, Easy or Fairly Easy to understand. Lynoe’s and Montgomery’s studies with participants of a chronic dialysis and anaesthesia trial similarly found that most participants found the PIL to be helpful and easy to read [ 50 , 51 ]. There is evidence that PILs/ICFs are becoming longer and more complex [ 52 , 53 ], and it is challenging for research teams and sponsors to balance giving the pertinent information without overwhelming potential participants. The General Data Protection legislation introduced in the European Union brought about extra challenges as additional information must now be provided to participants [ 54 , 55 ]. While participant satisfaction with the information provided is undoubtedly important, helping participants understand the key elements needed to provide informed consent is also critical. Regarding multimedia resources, such as an application, website or video: only 5% of research participants were offered them and only 6% of research staff use them—while further empirical research is needed to assess the effect of multimedia on the quality of informed consent, these kinds of supports may be useful, particularly for some groups of participants [ 46 , 56 , 57 ].

Teach Back/Talk Back method

In this study, 88% of research staff reported that they confirm a participant’s level of understanding. This self-reported rate was higher than in Jenkins’ analysis of 82 recordings of actual informed consent discussions which indicated that in nearly 83% of cases participant understanding was not confirmed [ 26 ]. The majority of research staff in this study reported that they confirm participant’s understanding by asking if they have any questions. However, Nusbaum and colleagues were critical of simply asking the participant if they have understood or if they have any questions—how can a participant judge themselves if they have understood? It may also be difficult for participants to ask questions if they have not understood key pieces of information [ 28 ]. In this study, 19% of research participants reported that they did not have any questions to ask. Interestingly, Keller’s semi-structured interviews with 18 research staff indicated that Principal Investigators tend to approach participants who do not ask too many questions and those without a strong personality [ 42 ]. Cox noted that 40% of clinical research participants interviewed regarding their experiences did not feel able to ask questions [ 58 ]. Thirty-five percent of research staff in this study reported that they used Teach Back/Talk Back strategies to ensure that participants have understood. The Teach Back/Talk Back method involves the patient or service user verbally relaying the information that they have been given back to the provider and has been found to have a positive effect on health communication in the clinical (non-research) setting [ 59 ]. Flory and Emanuel’s systematic review of interventions to improve informed consent reported five trials which indicates that test/feedback showed significant improvement in understanding [ 47 ]. Perhaps, therefore, Teach Back/Talk Back strategies should be encouraged when researchers are undergoing training on how to facilitate informed consent. However, it should be noted that the Teach Back/Talk Back method may require additional time, which may already be in short supply.

Limitations

The method of sampling, in particular the use of chain referral sampling is a limitation of this study, as it is non-random in nature [ 30 ]. There may have been enthusiasm bias as both research staff and research participants who are interested in optimizing the informed consent process may have been more likely to respond to the survey. Similarly, there may have been selection bias associated with the distribution of the paper surveys to research participants—due to the COVID-19 restrictions, the surveys had to be given out by the research or clinical staff and not systematically by an independent researcher. The survey was developed specifically to fulfil the aims of this research study and was piloted with representatives from both target groups but was not formally validated. It was not possible to estimate the response rate of the online surveys and approximately a quarter of the research participants were recruited from a single hospital—this makes it difficult to assess the generalisability of the results. Structured, anonymised surveys were used to gather quantitative data regarding specific factors which relate to the process of informed consent. While additional open-ended questions may have explored these factors in more depth, previous qualitative studies have investigated the perceptions of research staff and participants [ 22 , 42 , 60 , 61 , 62 ]. It is also important to note that the research staff in this study had a range of experiences, perhaps in different settings, to report on from when answering the survey, while some of the research participants had only a single consent discussion experience to draw from. Finally, the lack of demographic detail for the research participants, e.g. education level, limits the generalisability of the findings of this study.

Research participants in this study were overwhelmingly positive about their experience of the informed consent process. However, research staff expressed concern about how much participants have understood and studies of patient comprehension of research study information would seem to confirm these fears. Adequate time should be allocated to informed consent discussions and research staff could consider using Teach Back/Talk Back techniques to confirm and enhance understanding.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

General Data Protection Regulation

General Practitioner

Health Research Board – Trials Methodology Research Network

Informed Consent Form

Irish Research Nurses and Midwives Network

Patient Information Leaflet

Research Electronic Data Capture

Statistical Package for the Social Science

United Kingdom

Cahana A, Hurst SA. Voluntary informed consent in research and clinical care: an update. Pain Pract. 2008;8(6):446–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-2500.2008.00241.x .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gupta UC. Informed consent in clinical research: revisiting few concepts and areas. Perspectives in clinical research. 2013;4(1):26–32. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.106373 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Declaration of Helsinki. Helsinki, Finland: World Medical Association; 2013. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ . Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

Corrigan O. Empty ethics: the problem with informed consent. Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25(7):768–92. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9566.2003.00369.x .

Grady C. Enduring and emerging challenges of informed consent. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(9):855–62. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1411250 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sugarman J, McCrory DC, Powell D, Krasny A, Adams B, Ball E, et al. Special supplement: empirical research on informed consent: an annotated bibliography. Hastings Center Report. 1999;29(1):S1–S42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3528546 .

Verheggen FW, Jonkers R, Kok G. Patients’ perceptions on informed consent and the quality of information disclosure in clinical trials. Patient Educ Counseling. 1996;29(2):137–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-3991(96)00859-2 .

Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Results of an intervention study to improve communication about randomised clinical trials of cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(3):322–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00415-9 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pope JE, Tingey DP, Arnold JM, Hong P, Ouimet JM, Krizova A. Are subjects satisfied with the informed consent process? A survey of research participants. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(4):815–24.

PubMed Google Scholar

Tam NT, Huy NT, Thoale TB, Long NP, Trang NT, Hirayama K, et al. Participants’ understanding of informed consent in clinical trials over three decades: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(3):186–98h.

Article Google Scholar

Burgess LJ, Gerber B, Coetzee K, Terblanche M, Agar G, Kotze TJ. An evaluation of informed consent comprehension by adult trial participants in South Africa at the time of providing consent for clinical trial participation and a review of the literature. Open Access J Clin Trials. 2019;11:19–35. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJCT.S145068 .

Knifed E, Lipsman N, Mason W, Bernstein M. Patients’ perception of the informed consent process for neurooncology clinical trials. Neuro-oncology. 2008;10(3):348–54. https://doi.org/10.1215/15228517-2008-007 .

Hamnes B, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Primdahl J. Readability of patient information and consent documents in rheumatological studies. BMC Medical Ethics. 2016;17(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0126-0 .

O'Sullivan L, Sukumar P, Crowley R, McAuliffe E, Doran P. The readability and understandability of clinical research patient information leaflets and consent forms in Ireland and the UK: a retrospective quantitative analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9).

Gillies K, Huang W, Skea Z, Brehaut J, Cotton S. Patient information leaflets (PILs) for UK randomised controlled trials: a feasibility study exploring whether they contain information to support decision making about trial participation. Trials. 2014;15(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-62 .

Kirkby HM, Calvert M, Draper H, Keeley T, Wilson S. What potential research participants want to know about research: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3).

Smyth RMD, Jacoby A, Elbourne D. Deciding to join a perinatal randomised controlled trial: Experiences and views of pregnant women enroled in the Magpie Trial. Midwifery. 2012;28(4):E478–E85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2011.08.006 .

Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, Grisso T. Therapeutic misconception in clinical research: frequency and risk factors. IRB: Ethics & Human Research. 2004;26(2):1–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/3564231 .

Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Souhami R. Clinicians’ attitudes to clinical trials of cancer therapy. European Journal of Cancer. 1997;33(13):2221–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00253-0 .

Spaar A, Frey M, Turk A, Karrer W, Puhan MA. Recruitment barriers in a randomized controlled trial from the physicians’ perspective – a postal survey. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009;9(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-14 .

Bernhardt BA, Roche MI, Perry DL, Scollon SR, Tomlinson AN, Skinner D. Experiences with obtaining informed consent for genomic sequencing. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2015;167(11):2635–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37256 .

Donovan JL, de Salis I, Toerien M, Paramasivan S, Hamdy FC, Blazeby JM. The intellectual challenges and emotional consequences of equipoise contributed to the fragility of recruitment in six randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(8):912–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.010 .

Taylor KM, Kelner M. Interpreting physician participation in randomized clinical trials: the physician orientation profile. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28(4):389–400. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136792 .

Taylor KM, Margolese RG, Soskolne CL. Physicians’ reasons for not entering eligible patients in a randomized clinical trial of surgery for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(21):1363–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198405243102106 .

Schröder Håkansson A, Pergert P, Abrahamsson J, Stenmarker M. Balancing values and obligations when obtaining informed consent: healthcare professionals’ experiences in Swedish paediatric oncology. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992). 2019.

Jenkins VA, Fallowfield LJ, Souhami A, Sawtell M. How do doctors explain randomised clinical trials to their patients? European Journal of Cancer. 1999;35(8):1187–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00116-1 .

Boden-Albala B, Carman H, Southwick L, Parikh Nina S, Roberts E, Waddy S, et al. Examining barriers and practices to recruitment and retention in stroke clinical trials. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2232–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008564 .

Nusbaum L, Douglas B, Damus K, Paasche-Orlow M, Estrella-Luna N. Communicating risks and benefits in informed consent for research: a qualitative study. Global Qualitative Nursing Research. 2017;4:2333393617732017.

Declaration of Helsinki. Helsinki, Finland: World Medical Organisation; 2013.

Johnson TP. Snowball sampling: introduction. Statistics Reference Online: Wiley StatsRef; 2014.

Google Scholar

Sahlqvist S, Song Y, Bull F, Adams E, Preston J, Ogilvie D, et al. Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-62 .

Jones TL, Baxter MAJ, Khanduja V. A quick guide to survey research. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2013;95(1):5–7. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588413X13511609956372 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sudman S, Bradburn NM. Asking questions: a practical guide to questionnaire design. San Francisco;Oxford: Jossey-Bass; 1982.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 .

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa .

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 .

Franck LS, Winter I, Oulton K. The quality of parental consent for research with children: a prospective repeated measure self-report survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007;44(4):525–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.014 .

Kupst MJ, Patenaude AF, Walco GA, Sterling C. Clinical trials in pediatric cancer: parental perspectives on informed consent. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2003;25(10).

Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, Morrow G, Schmale AH, Derogatis LR, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1984;2(7):849–55. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1984.2.7.849 .

Goodman NW, Cooper GM, Malins AF, Prys-Roberts C. The validity of informed consent in a clinical study. Anaesthesia. 1984;39(9):911–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1984.tb06582.x .

Keller P-H, Grondin O, Tison F, Gonon F. How health professionals conceptualize and represent placebo treatment in clinical trials and how their patients understand it: impact on validity of informed consent. PloS one. 2016;11(5):e0155940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155940 .

Moynihan C, Lewis R, Hall E, Jones E, Birtle A, Huddart R, et al. The Patient Deficit Model Overturned: a qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of invitation to participate in a randomized controlled trial comparing selective bladder preservation against surgery in muscle invasive bladder cancer (SPARE, CRUK/07/011). Trials. 2012;13(1):228.

Hietanen P, Aro AR, Holli K, Absetz P. Information and communication in the context of a clinical trial. European Journal of Cancer. 2000;36(16):2096–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00191-X .

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York;Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013.

Nishimura A, Carey J, Erwin PJ, Tilburt JC, Murad MH, McCormick JB. Improving understanding in the research informed consent process: a systematic review of 54 interventions tested in randomized control trials. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-14-28 .

Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants’ understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2004;292(13):1593–601. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.13.1593 .

Aaronson NK, Visser-Pol E, Leenhouts GH, Muller MJ, van der Schot AC, van Dam FS, et al. Telephone-based nursing intervention improves the effectiveness of the informed consent process in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(3):984–96. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.984 .

Tindall B, Forde S, Ross MW, Goldstein D, Barker S, Cooper DA. Effects of two formats of informed consent on knowledge amongst persons with advanced HIV disease in a clinical trial of didanosine. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;24(3):261–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-3991(94)90069-8 .

Lynöe N, Näsström B, Sandlund M. Study of the quality of information given to patients participating in a clinical trial regarding chronic hemodialysis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38(6):517–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365590410033362 .

Montgomery J, Sneyd J. Consent to clinical trials in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1998;53(3):227–30. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00309.x .

Beardsley E, Jefford M, Mileshkin L. Longer consent forms for clinical trials compromise patient understanding: so why are they lengthening? J Clin Oncol. 25. United States 2007. p. e13-4.

Hammerschmidt D, Md F, Keane M. Institutional review board (IRB) review lacks impact on the readability of consent forms for research. Am J Med Sci. 1992;304(6):348–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-199212000-00003 .

Clarke N, Vale G, Reeves EP, Kirwan M, Smith D, Farrell M, et al. GDPR: an impediment to research? Irish J Med Sci. 2019;188(4):1129–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-019-01980-2 .

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council). European Union. 2016.

Synnot A, Ryan R, Prictor M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Parker B. Audio-visual presentation of information for informed consent for participation in clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):Cd003717.

Palmer BW, Lanouette NM, Jeste DV. Effectiveness of multimedia aids to enhance comprehension of research consent information: a systematic review. IRB. 2012;34(6):1–15.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cox K. Informed consent and decision-making: patients’ experiences of the process of recruitment to phases I and II anti-cancer drug trials. Patient Education and Counseling. 2002;46(1):31–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00147-1 .

Yen PH, Leasure AR. Use and effectiveness of the teach-back method in patient education and health outcomes. Fed Pract. 2019;36(6):284–9.

Durant RW, Wenzel JA, Scarinci IC, Paterniti DA, Fouad MN, Hurd TC, et al. Perspectives on barriers and facilitators to minority recruitment for clinical trials among cancer center leaders, investigators, research staff, and referring clinicians: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT). Cancer. 2014;120(S7):1097–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28574 .

Kost RG, Lee LN, Yessis JL, Wesley R, Alfano S, Alexander SR, et al. Research participant-centered outcomes at NIH-supported clinical research centers. Clinical and translational science. 2014;7(6):430–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12167 .

Gordon EJ, Knopf E, Phillips C, Mussell A, Lee J, Veatch RM, et al. Transplant candidates’ perceptions of informed consent for accepting deceased donor organs subjected to intervention research and for participating in posttransplant research. Am J Transplantation. 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The research team is grateful to the Health Research Board - Trials Methodology Research Network, Clinical Research Coordination Ireland, the UCD Clinical Research Centre, the Irish Research Nurse’s Network, the Irish Platform for Patient Organisations Science and Industry, Patient Voices in Cancer Research, Patient Voice’s in Arthritis Research and Patient Voices in Diabetes Research for their contributions to this study.

This work was supported by the Health Research Board Trials Methodology Research Network (HRB-TMRM) as part of the HRB-TMRN-2017-1 grant. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Medicine, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Lydia O’ Sullivan, Laura Feeney, Rachel K. Crowley, Prasanth Sukumar & Peter Doran

Health Research Board-Trials Methodology Research Network, Galway, Ireland

Lydia O’ Sullivan & Peter Doran

Department of Endocrinology, Saint Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin 4, Ireland

Rachel K. Crowley

University College Dublin Centre for Interdisciplinary Research, Education and Innovation in Health Systems, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Eilish McAuliffe

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LOS contributed to the study design, carried out data collection and analysis and wrote the manuscript. LF contributed to the study design and data collection and reviewed the manuscript. PS built the REDCap database, contributed to the analysis and reviewed the manuscript. RC and EMcA participated in the study design and review of the manuscript. PD leads the research team, acquired funding for the study, contributed to the design of the research and reviewed the manuscript. The authors approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lydia O’ Sullivan .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Full ethics approval was granted by the Saint Vincent’s Healthcare Group Ethics and Medical Research Committee, Dublin 4, Ireland; Ref: RS20-026. A low-risk ethics exemption was also granted by the University College Dublin Research Ethics Committee; Ref: LS-E-20-117-OSullivan-Doran. Participants self-selected to complete the surveys after they were provided with an information leaflet explaining the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable—no individual details, images or videos used.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Research Participant’s Survey.

Additional file 2.

Research Staff Survey.

Additional file 3.

Participant Information Leaflet (Research Participants).

Additional file 4.

Participant Information Leaflet (Research Staff).

Additional file 5.

Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)

Additional file 6.

Complete list of responses from research participants to open-ended question

Additional file 7.

Complete list of responses from research staff to open-ended question

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

O’ Sullivan, L., Feeney, L., Crowley, R.K. et al. An evaluation of the process of informed consent: views from research participants and staff. Trials 22 , 544 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05493-1

Download citation

Received : 24 May 2021

Accepted : 27 July 2021

Published : 18 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05493-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Informed consent

- Clinical research

- Clinical trials

- Methodology

- Surveys and Questionnaires

ISSN: 1745-6215

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Privacy Policy

Home » Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates and Examples

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates and Examples

Table of Contents

Informed Consent in Research

Informed consent is a process of communication between a researcher and a potential participant in which the researcher provides adequate information about the study, its risks and benefits, and the participant voluntarily agrees to participate. It is a cornerstone of ethical research involving human subjects and is intended to protect the rights and welfare of participants.

Types of Informed Consent in Research

There are different types of informed consent in research , which may vary depending on the nature of the study, the type of participants, and the context. Some of the common types of informed consent in research include:

Written Consent

This is the most common type of informed consent, where participants are provided with a written document that explains the study and its requirements. The document typically includes information about the purpose of the study, procedures involved, risks and benefits, confidentiality, and participant rights. Participants are asked to sign the document as an indication of their willingness to participate.

Oral Consent

In some cases, oral consent may be used when a written document is not practical or feasible. Oral consent involves explaining the study and its requirements to participants verbally and obtaining their consent. This method may be used for studies with illiterate or visually impaired participants or when conducting research remotely.

Implied Consent

Implied consent is used in studies where participants’ actions are taken as an indication of their willingness to participate. For example, a participant may be considered to have given implied consent if they show up for a scheduled appointment for the study.

Opt-out Consent

This method is used when participants are given the opportunity to decline participation in a study. Participants are provided with information about the study and are given the option to opt-out if they do not wish to participate. This method is commonly used in population-based studies or surveys.

Assent is used in studies involving minors or participants who are unable to provide informed consent due to cognitive impairment or disability. Assent involves obtaining the agreement of the participant to participate in the study, along with the consent of a legally authorized representative.

Informed Consent Format in Research

Here’s a basic format for informed consent that can be customized for specific research studies:

- Introduction : Begin by introducing yourself and the purpose of the study. Clearly state that participation is voluntary and that participants can withdraw at any time without penalty.

- Study Overview : Provide a brief overview of the study, including its purpose, methods, and expected outcomes.

- Procedures : Describe the procedures involved in the study in clear, concise language. Include information about the types of data that will be collected, how they will be collected, and how long the study will take.

- Risks and Benefits : Outline the potential risks and benefits of participating in the study. Be honest and upfront about any discomfort, inconvenience, or potential harm that may be involved, as well as any potential benefits.

- Confidentiality and Privacy : Explain how participant data will be collected, stored, and used, and what measures will be taken to ensure confidentiality and privacy.

- Voluntary Participation: Emphasize that participation is voluntary and that participants can withdraw at any time without penalty. Explain how to withdraw from the study and who to contact if participants have questions or concerns.

- Compensation and Incentives: If applicable, explain any compensation or incentives that will be offered to participants for their participation.

- Contact Information: Provide contact information for the researcher or a representative from the research team who can answer questions and address concerns.

- Signature : Ask participants to sign and date the consent form to indicate their voluntary agreement to participate in the study.

Informed Consent Templates in Research

Here is an example of an informed consent template that can be used in research studies:

Introduction

You are being invited to participate in a research study. Before you decide whether or not to participate, it is important for you to understand why the research is being done, what your participation will involve, and what risks and benefits may be associated with your participation.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is [insert purpose of study].

If you agree to participate, you will be asked to [insert procedures involved in the study].

Risks and Benefits

There are several potential risks and benefits associated with participation in this study. Some of the risks include [insert potential risks of participation]. Some of the benefits include [insert potential benefits of participation].

Confidentiality

Your participation in this study will be kept confidential to the extent allowed by law. All data collected during the study will be stored in a secure location and only accessed by authorized personnel. Your name and other identifying information will not be included in any reports or publications resulting from this study.

Voluntary Participation

Your participation in this study is completely voluntary. You have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. If you choose not to participate or if you withdraw from the study, there will be no negative consequences.

Contact Information

If you have any questions or concerns about the study, you can contact the investigator(s) at [insert contact information]. If you have questions about your rights as a research participant, you may contact [insert name of institutional review board and contact information].

Statement of Consent

By signing below, you acknowledge that you have read and understood the information provided in this consent form and that you freely and voluntarily consent to participate in this study.

Participant Signature: _____________________________________ Date: _____________

Investigator Signature: ____________________________________ Date: _____________

Examples of Informed Consent in Research

Here’s an example of informed consent in research:

Title : The Effects of Yoga on Stress and anxiety levels in college students

Introduction :

We are conducting a research study to investigate the effects of yoga on stress and anxiety levels in college students. We are inviting you to participate in this study.

If you agree to participate, you will be asked to attend four yoga classes per week for six weeks. Before and after the six-week period, you will be asked to complete surveys about your stress and anxiety levels. Additionally, we will measure your heart rate variability at the beginning and end of the six-week period.

Risks and Benefits:

There are no known risks associated with participating in this study. However, the benefits of practicing yoga may include decreased stress and anxiety levels, increased flexibility and strength, and improved overall well-being.

Confidentiality:

All information collected during this study will be kept strictly confidential. Your name will not be used in any reports or publications resulting from this study.

Voluntary Participation:

Participation in this study is completely voluntary. You are free to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Contact Information:

If you have any questions or concerns about this study, you may contact the principal investigator at (phone number/email address).

By signing this form, I acknowledge that I have read and understood the above information and agree to participate in this study.

Participant Signature: ___________________________

Date: ___________________________

Researcher Signature: ___________________________

Importance of Informed Consent in Research

Here are some reasons why informed consent is important in research:

- Protection of participants’ rights : Informed consent ensures that participants understand the nature and purpose of the research, the risks and benefits of participating, and their rights as participants. It empowers them to make an informed decision about whether to participate or not.

- Ethical responsibility : Researchers have an ethical responsibility to respect the autonomy of participants and to protect them from harm. Informed consent is a crucial way to uphold these principles.

- Legality : Informed consent is a legal requirement in most countries. It is necessary to protect researchers from legal liability and to ensure that research is conducted in accordance with ethical standards.

- Trust : Informed consent helps build trust between researchers and participants. When participants understand the research process and their role in it, they are more likely to trust the researchers and the study.

- Quality of research : Informed consent ensures that participants are fully informed about the research and its purpose, which can lead to more accurate and reliable data. This, in turn, can improve the quality of research outcomes.

Purpose of Informed Consent in Research

Informed consent is a critical component of research ethics, and it serves several important purposes, including:

- Respect for autonomy: Informed consent respects an individual’s right to make decisions about their own health and well-being. It recognizes that individuals have the right to choose whether or not to participate in research, based on their own values, beliefs, and preferences.

- Protection of participants : Informed consent helps protect research participants from potential harm or risks that may arise from their involvement in a study. By providing participants with information about the study, its risks and benefits, and their rights, they are able to make an informed decision about whether to participate.

- Transparency: Informed consent promotes transparency in the research process. It ensures that participants are fully informed about the research, including its purpose, methods, and potential outcomes, which helps to build trust between researchers and participants.

- Legal and ethical requirements: Informed consent is a legal and ethical requirement in most research studies. It ensures that researchers obtain voluntary and informed agreement from participants to participate in the study, which helps to protect the rights and welfare of research participants.

Advantages of Informed Consent in Research

The advantages of informed consent in research are numerous, and some of the most significant benefits include:

- Protecting participants’ autonomy: Informed consent allows participants to exercise their right to self-determination and make decisions about whether to participate in a study or not. It also ensures that participants are fully informed about the risks, benefits, and implications of participating in the study.

- Promoting transparency and trust: Informed consent helps build trust between researchers and participants by providing clear and accurate information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential outcomes. This transparency promotes open communication and a positive research experience for all parties involved.

- Reducing the risk of harm: Informed consent ensures that participants are fully aware of any potential risks or side effects associated with the study. This knowledge enables them to make informed decisions about their participation and reduces the likelihood of harm or negative consequences.

- Ensuring ethical standards are met : Informed consent is a fundamental ethical requirement for conducting research involving human participants. By obtaining informed consent, researchers demonstrate their commitment to upholding ethical principles and standards in their research practices.

- Facilitating future research : Informed consent enables researchers to collect high-quality data that can be used for future research purposes. It also allows participants to make an informed decision about whether they are willing to participate in future studies.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Thesis Statement – Examples, Writing Guide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Process consent: a model for enhancing informed consent in mental health nursing

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing Sciences, James Cook University of North Queensland, Townsville, Australia.

- PMID: 9578197

- DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00589.x

Informed consent, essentially a legal doctrine, is designed to protect the rights of patients. However, in an area of practice such as psychiatry, informed consent imposes many problems if one considers it to be a static process. In this paper we propose that process consent, the type of consent considered essential in qualitative research projects, is not only appropriate but necessary for mental health nursing practice. This type of consent is an ongoing consensual process that involves the nurse and patient in mutual decision making and ensures that the patient is kept informed at all stages of the treatment process. We have used neuroleptic medications as an example throughout the paper and have suggested that seeking informed consent should be added to the role of the nurse in the mental health setting.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Informed consent in the elderly: assessing decisional capacity. Artnak KE. Artnak KE. Semin Perioper Nurs. 1997 Jan;6(1):59-64. Semin Perioper Nurs. 1997. PMID: 9087123 Review.

- The nurse's role as patient advocate for mentally ill people. Duxbury J. Duxbury J. Nurs Stand. 1996 Feb 7;10(20):36-9. doi: 10.7748/ns.10.20.36.s48. Nurs Stand. 1996. PMID: 8695429

- The right to refuse: informed consent and the psychosocial nurse. Weiss FS. Weiss FS. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1990 Aug;28(8):25-30. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19900801-09. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1990. PMID: 2398483 No abstract available.

- Intrusion into patient privacy: a moral concern in the home care of persons with chronic mental illness. Magnusson A, Lützén K. Magnusson A, et al. Nurs Ethics. 1999 Sep;6(5):399-410. doi: 10.1177/096973309900600506. Nurs Ethics. 1999. PMID: 10696187

- Approaches (and possible contraindications) to enhancing patients' autonomy. Howe EG. Howe EG. J Clin Ethics. 1994 Fall;5(3):179-88. J Clin Ethics. 1994. PMID: 7841467 Review. No abstract available.

- A qualitative study of organisational resilience in care homes in Scotland. Ross A, Anderson JE, Selveindran S, MacBride T, Bowie P, Sherriff A, Young L, Fioratou E, Roddy E, Edwards H, Dewar B, Macpherson LM. Ross A, et al. PLoS One. 2022 Dec 20;17(12):e0279376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279376. eCollection 2022. PLoS One. 2022. PMID: 36538564 Free PMC article.

- Respect for Autonomy and Dementia Care in Nursing Homes: Revising Beauchamp and Childress's Account of Autonomous Decision-Making. Soofi H. Soofi H. J Bioeth Inq. 2022 Sep;19(3):467-479. doi: 10.1007/s11673-022-10195-7. Epub 2022 Jun 24. J Bioeth Inq. 2022. PMID: 35749025 Free PMC article.

- Diagnostic accuracy and clinical applicability of the Swedish version of the 4AT assessment test for delirium detection, in a mixed patient population and setting. Johansson YA, Tsevis T, Nasic S, Gillsjö C, Johansson L, Bogdanovic N, Kenne Sarenmalm E. Johansson YA, et al. BMC Geriatr. 2021 Oct 18;21(1):568. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02493-3. BMC Geriatr. 2021. PMID: 34663229 Free PMC article.

- Factors impacting the implementation of a psychoeducation intervention within the mental health system: a multisite study using the consolidation framework for implementation research. Higgins A, Murphy R, Downes C, Barry J, Monahan M, Hevey D, Kroll T, Doyle L, Gibbons P. Higgins A, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Nov 9;20(1):1023. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05852-9. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020. PMID: 33168003 Free PMC article.

- A Proposed Process for Risk Mitigation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cox DJ, Plavnick JB, Brodhead MT. Cox DJ, et al. Behav Anal Pract. 2020 Apr 23;13(2):299-305. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00430-1. eCollection 2020 Jun. Behav Anal Pract. 2020. PMID: 32328220 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Informed consent

Information and guidance for researchers, what is informed consent.

Informed consent is one of the founding principles of research ethics. Its intent is that human participants can enter research freely (voluntarily) with full information about what it means for them to take part, and that they give consent before they enter the research.

Consent should be obtained before the participant enters the research (prospectively), and there must be no undue influence on participants to consent. The minimum requirements for consent to be informed are that the participant understands what the research is and what they are consenting to.

There are two distinct stages to a standard consent process for competent adults:

- Stage 1 (giving information) : the person reflects on the information given; they are under no pressure to respond to the researcher immediately.

- Stage 2 (obtaining consent): the researcher reiterates the terms of the research, often as separate bullet points or clauses; the person agrees to each term (giving explicit consent) before agreeing to take part in the project as a whole. Consent has been obtained.

Researchers should ensure that they comply with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) during and after the consent process, especially if they will be collecting 'special category' (ie sensitive) data or personal data in the course of their research (also refer to the advice on consent in research involving children ). See also the guidance on data protection and research and the data protection checklist for use when preparing an application for ethical review.

Where your research includes filming or photography, you should refer to specific guidance in the Photography and GDPR toolkit .

Written or oral consent – which process suits your project?

Which process to use depends on the research project (its context, design and participants), though an oral process is usually only appropriate where a written process is not feasible. Any consent process must be understandable to the participants concerned. Please see the sections below to find out about different processes which may be used depending on the context, as well as informed consent templates for each process.

Written informed consent process

A written process is used where:

- Reading and signing forms is not problematic.

- The research is complex or has multiple stages.

- First access to the research participants is by providing written information.

Though opinions differ about the legal force of signed consent forms, they provide extra proof that the terms of consent have been understood. This can be especially important when seeking consent for copyright over data, or for future uses of data. Also, future funders or regulators may want written proof of the terms of original consent.