VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 07, 2023

What is Plot Structure? Definition and Diagram

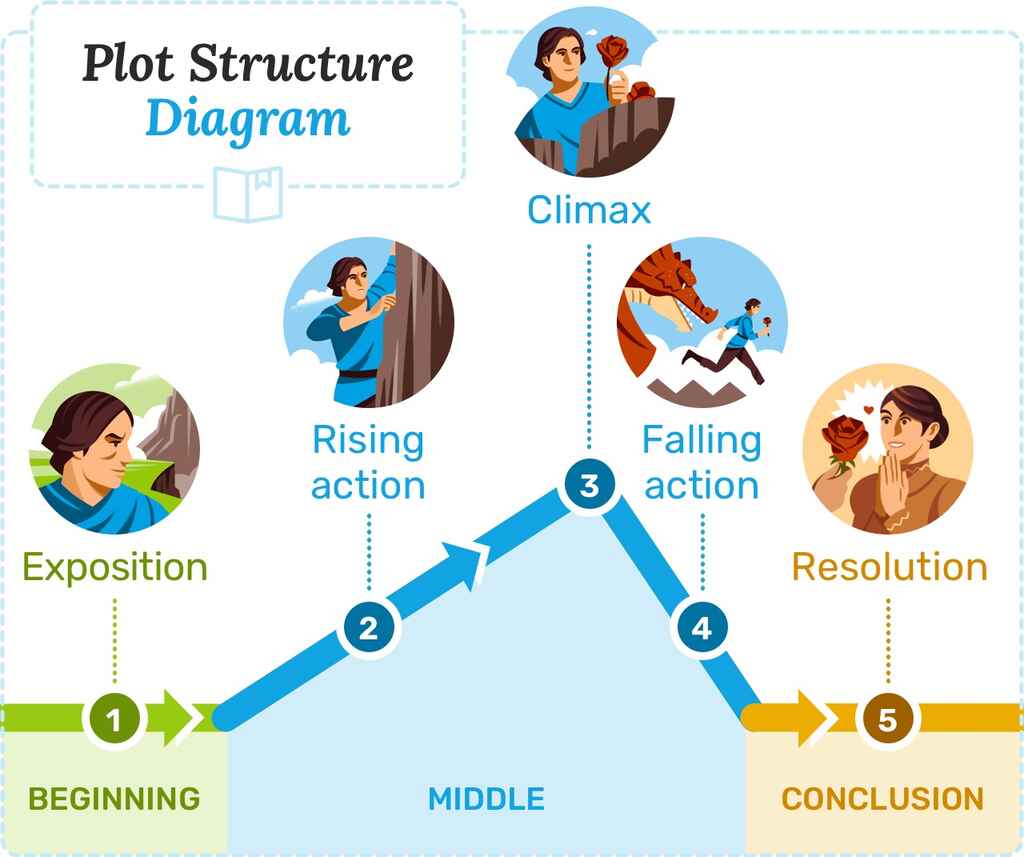

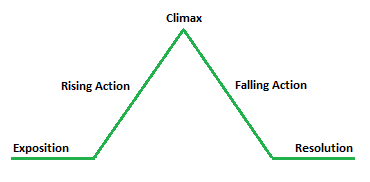

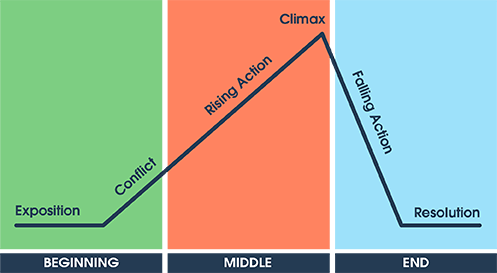

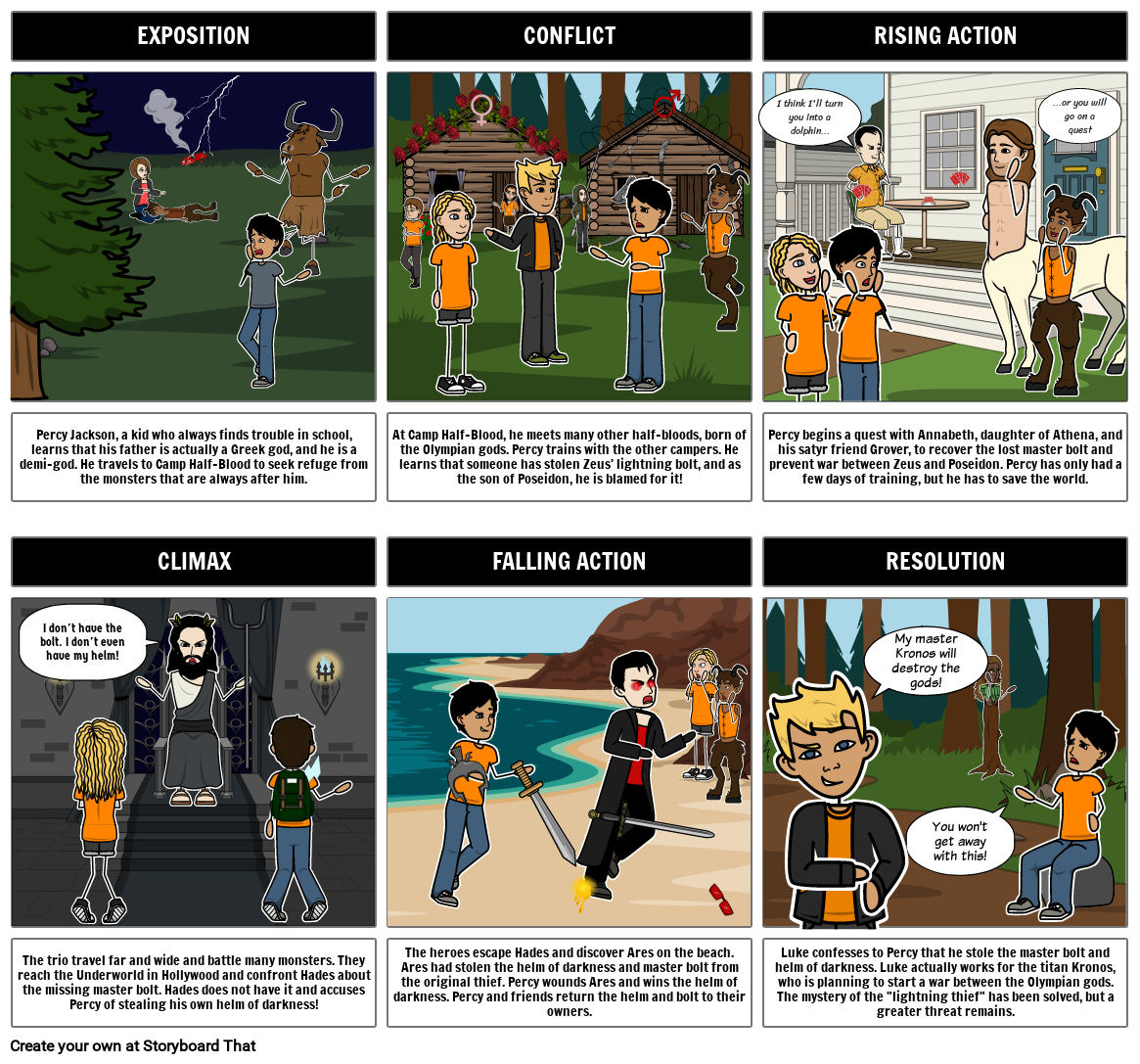

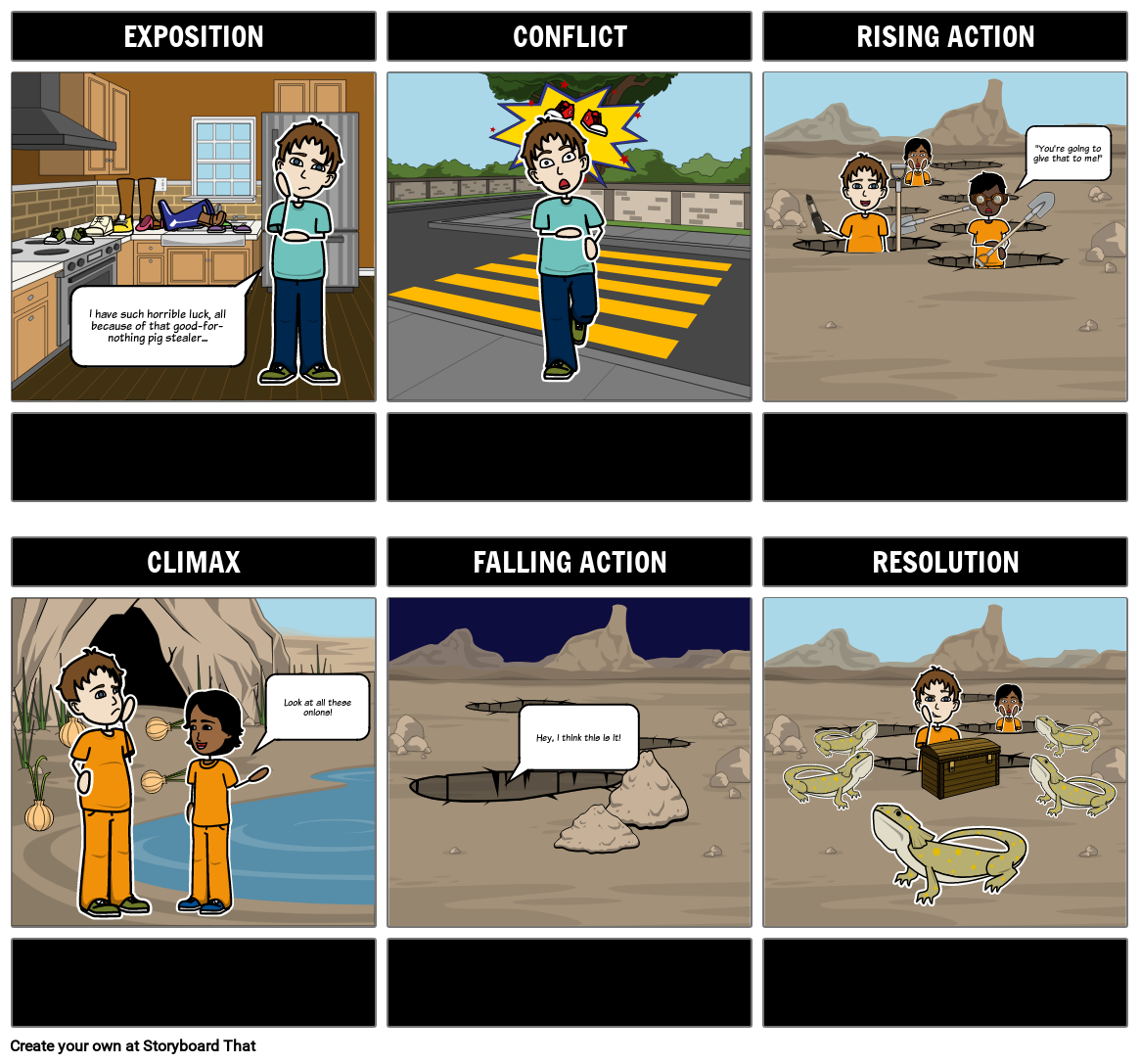

Plot structure is the order in which the events of a story unfold. In western storytelling traditions, it’s usually built out of five stages: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

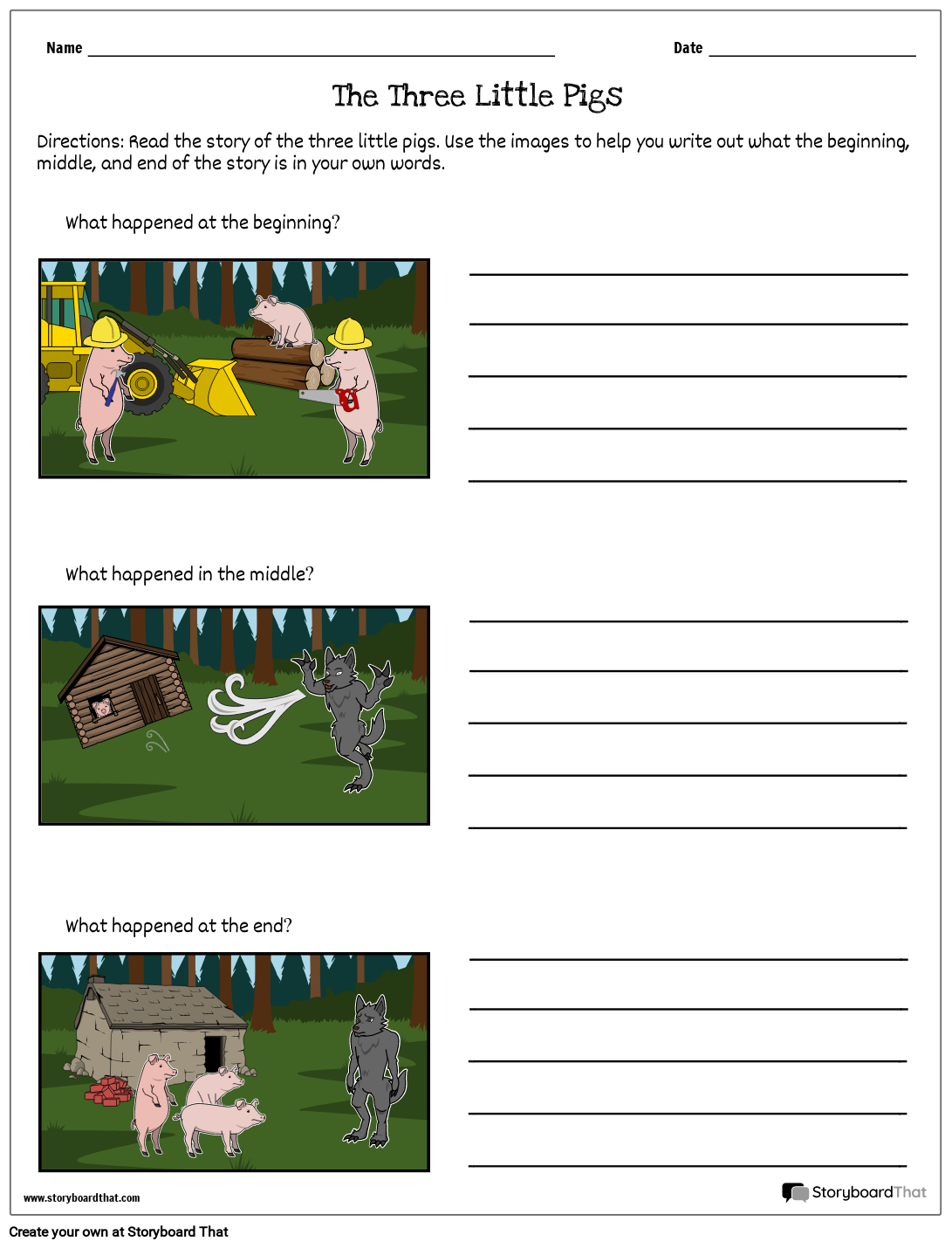

From Westworld and Jane Eyre to your grandma’s favorite childhood anecdote, most stories seem to follow this architecture. It dates back to Aristotle’s Three-Act structure , which divides a story into a beginning, middle, and end, and it was further elaborated on by German novelist Gustav Freytag, among others, who proposed a “technique for drama” — a five-stage plot structure that is now better known as Freytag’s pyramid .

In this post, we’ll look at the basic elements of plot structure in more detail. We’ll use Tolkien’s Fellowship of the Ring as an example with each stage. Though it may seem strange to demonstrate a five-step process with the first part of a trilogy, each book in The Lord of the Rings series has a complete plot with a distinct start and finish.

Plot Structure in Five Steps:

1. Exposition

2. rising action, 4. falling action, 5. resolution.

Which plot structure is right for your book?

Take our 1-minute quiz to find out.

To kick off your story , you'll need to introduce your main characters and the world they inhabit , thus laying the groundwork for the story ahead. This segment is known as the exposition , and it serves to present the 'ordinary world' or the status quo for your characters.

Example: “One ring to rule them all.”

In Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring , the 'ordinary world' is depicted through the lively and peaceful lives of hobbits in the Shire. It's only when an inciting incident jolts your character out of their comfort zone that the real action of the story gets underway. In this case, Frodo Baggins inherits a ring from his cousin Bilbo, but Gandalf reveals to him that it's the Ring of Power sought after by the dark lord Sauron 一 Frodo must embarks on a quest to destroy it.

☝️ We dive deeper into each of these five stages in this article on story structure . Also, if you’re keen to try to incorporate these “beats” into your own writing, get our free template below.

FREE RESOURCE

Three Act Structure Template

Craft a satisfying story arc with our free step-by-step template.

Once your protagonist is on a journey to accomplish something, the story truly comes alive and things start to happen. This sets the stage for a series of events in which the character faces ever more challenging internal and external conflicts , and makes both allies and enemies.

Example: “I will take the Ring to Mordor. Though I do not know the way.”

Frodo and his companions face many challenges, like the dreadful Black Riders, the freezing mountains, and the tension among some people in the group that the ring stirs up. The Fellowship, now made of nine valuable members, learns that Saruman has joined the enemy side.

This part is known as the rising action , it forms the bulk of the narrative, and it culminates in the narrative's emotional high point — the climax.

The climax in a story is the point where tension reaches its peak. It’s a pivotal moment or event that marks the point of no return for the character.

Example: “Fly, you fools.”

As the fellowship passes through the Mines of Moria, they confront a menacing creature, a Balrog. Gandalf fights off the beast, allowing the others to escape, but at the cost of his own life.

While the climax may not be the final obstacle for a protagonist, it is usually what induces them to truly take action to resolve their problem.

Following the climax, the story's tension begins to wane as unresolved issues and minor conflicts start to find closure. This beat serves as a sort of decompression chamber, allowing both characters and readers to step back from the intensity of the climax, and process “all that happened.”

Example: “You suffer, I see it day by day.”

Following the tragic loss of Gandalf, the Fellowship takes refuge in the mystical woods of Lothlórien, where they grapple with the gravity of their quest and reflect on their individual responsibilities. Boromir is seduced by the ring's power and tries to steal it from Frodo, though the hobbit manages to escape.

The resolution (also called denouement ) is the final phase in the story's plot structure, which wraps things up. While it often blends with the ‘falling action,’ the key difference is that the resolution offers closure to the story's main conflict. Essentially, it fulfills the promise of the premise set in motion by the inciting incident. That said, story endings can vary 一 some give a clear resolution, while others leave room for interpretation.

Example: “I’m going to Mordor alone.”

As for Frodo, he decides to separate from the group, fearing more of its members will be corrupted by the ring, and to continue the journey to Mordor alone (well, secretly followed by his best buddy Sam.) As The Fellowship of the Ring is only the first installment in a trilogy, the story's ultimate closure isn't reached until the final book. In spite of this, Frodo undergoes a significant character arc 一 from an unlikely and hesitant hero, dependent on other’s support, to a true leader determined to complete his mission.

And there you have them, the five key elements of plot structure. Whether you’re beginning to write a novel or working on a short story , dissecting its basic architecture can help you craft a cohesive and engaging narrative that keeps the reader turning the page.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Looking for a book coach?

Sign up to meet vetted book coaches who can help you turn your book idea into a reality.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Plot Definition

What is plot? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Plot is the sequence of interconnected events within the story of a play, novel, film, epic, or other narrative literary work. More than simply an account of what happened, plot reveals the cause-and-effect relationships between the events that occur.

Some additional key details about plot:

- The plot of a story explains not just what happens, but how and why the major events of the story take place.

- Plot is a key element of novels, plays, most works of nonfiction, and many (though not all) poems.

- Since ancient times, writers have worked to create theories that can help categorize different types of plot structures.

Plot Pronounciation

Here's how to pronounce plot: plaht

The Difference Between Plot and Story

Perhaps the best way to say what a plot is would be to compare it to a story. The two terms are closely related to one another, and as a result, many people often use the terms interchangeably—but they're actually different. A story is a series of events; it tells us what happened . A plot, on the other hand, tells us how the events are connected to one another and why the story unfolded in the way that it did. In Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster uses the following examples to distinguish between story and plot:

“The king died, and then the queen died” is a story. “The king died, and then the queen died of grief” is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: “The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.” This is a plot with a mystery in it.

Therefore, when examining a plot, it's helpful to look for events that change the direction of the story and consider how one event leads to another.

The Structure of a Plot

For nearly as long as there have been narratives with plots, there have been people who have tried to analyze and describe the structure of plots. Below we describe two of the most well-known attempts to articulate the general structure of plot.

Freytag's Pyramid

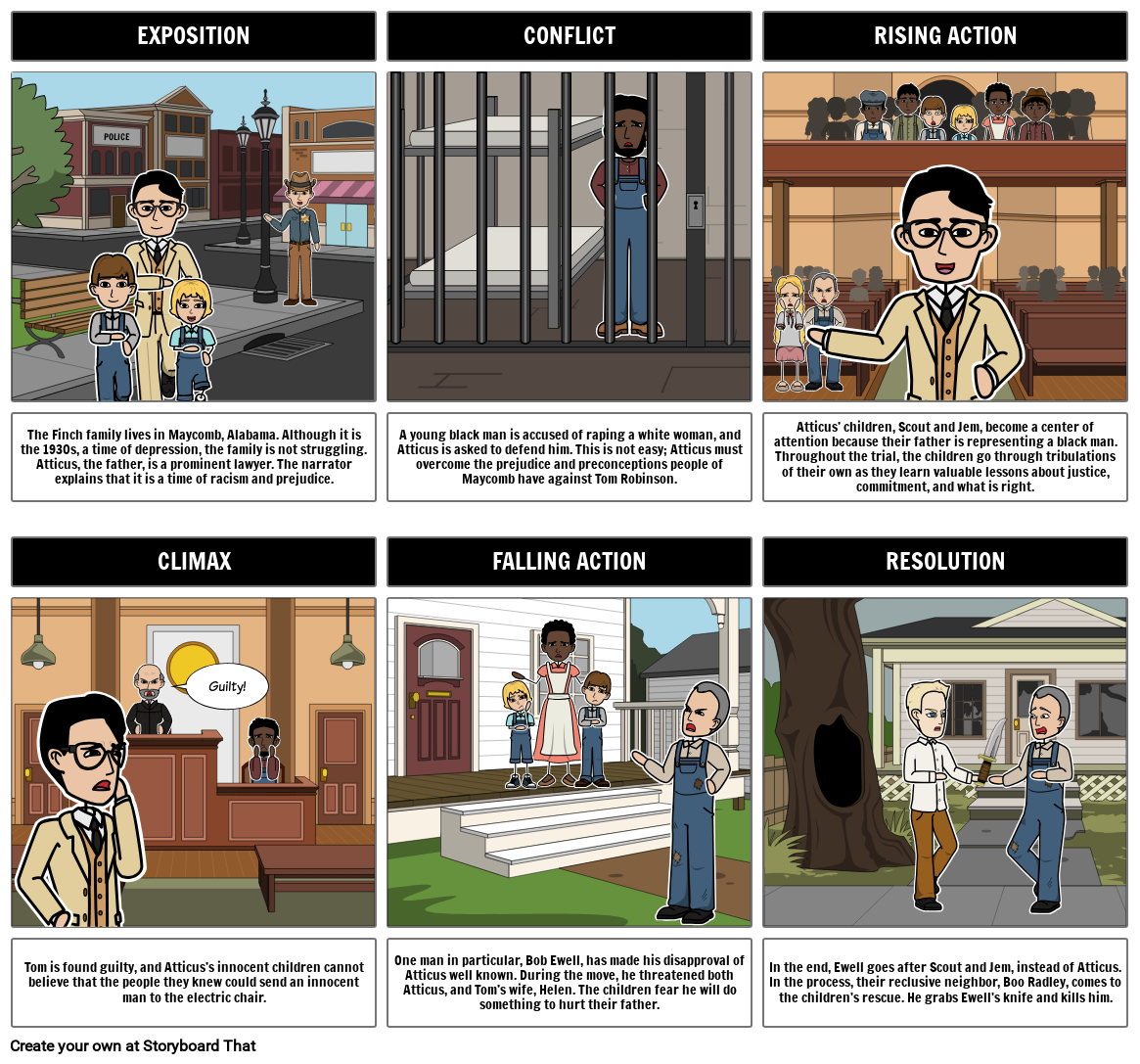

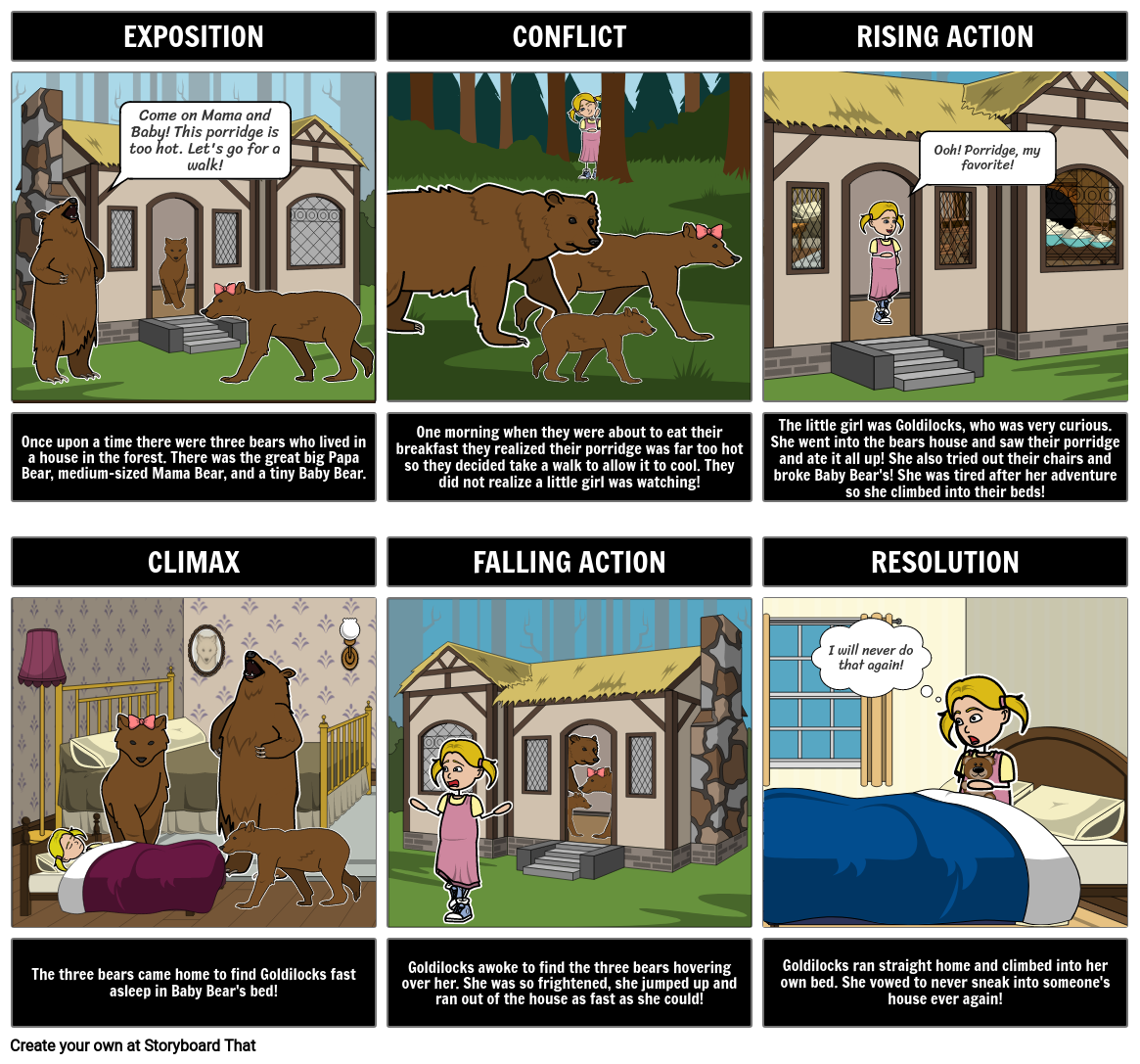

One of the first and most influential people to create a framework for analyzing plots was 19th-century German writer Gustav Freytag, who argued that all plots can be broken down into five stages: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement. Freytag originally developed this theory as a way of describing the plots of plays at a time when most plays were divided into five acts, but his five-layered "pyramid" can also be used to analyze the plots of other kinds of stories, including novels, short stories, films, and television shows.

- Exposition is the first section of the plot. During the exposition, the audience is introduced to key background information, including characters and their relationships to one another, the setting (or time and place) of events, and any other relevant ideas, details, or historical context. In a five-act play, the exposition typically occurs in the first act.

- The rising action begins with the "inciting incident" or "complication"—an event that creates a problem or conflict for the characters, setting in motion a series of increasingly significant events. Some critics describe the rising action as the most important part of the plot because the climax and outcome of the story would not take place if the events of the rising action did not occur. In a five-act play, the rising action usually takes place over the course of act two and perhaps part of act three.

- The climax of a plot is the story's central turning point, which the exposition and the rising action have all been leading up to. The climax is the moment with the greatest tension or conflict. Though the climax is also sometimes called the crisis , it is not necessarily a negative event. In a tragedy , the climax will result in an unhappy ending; but in a comedy , the climax usually makes it clear that the story will have a happy ending. In a five-act play, the climax usually takes place at the end of the third act.

- Whereas the rising action is the series of events leading up to the climax, the falling action is the series of events that follow the climax, ending with the resolution, an event that indicates that the story is reaching its end. In a five-act play, the falling action usually takes place over the course of the fourth act, ending with the resolution.

- Dénouement is a French word meaning "outcome." In literary theory, it refers to the part of the plot which ties up loose ends and reveals the final consequences of the events of the story. During the dénouement, the author resolves any final or outstanding questions about the characters’ fates, and may even reveal a little bit about the characters’ futures after the resolution of the story. In a five-act play, the dénouement takes place in the fifth act.

While Freytag's pyramid is very handy, not every work of literature fits neatly into its structure. In fact, many modernist and post-modern writers intentionally subvert the standard narrative and plot structure that Freytag's pyramid represents.

Booker's "Meta-Plot"

In his 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, Christopher Booker outlines an overarching "meta-plot" which he argues can be used to describe the plot structure of almost every story. Like Freytag's pyramid, Booker's meta-plot has five stages:

- The anticipation stage , in which the hero prepares to embark on adventure;

- The dream stage , in which the hero overcomes a series of minor challenges and gains a sense of confidence and invincibility;

- The frustration stage , in which the hero confronts the villain of the story;

- The nightmare stage , in which the hero fears they will be unable to overcome their enemy;

- The resolution , in which the hero finally triumphs.

Of course, like Freytag's Pyramid, Booker's meta-plot isn't actually a fool-proof way of describing the structure of every plot, but rather an attempt to describe structural elements that many (if not most) plots have in common.

Types of Plot

In addition to analyzing the general structure of plots, many scholars and critics have attempted to describe the different types of plot that serve as the basis of most narratives.

Booker's Seven Basic Plots

Within the overarching structure of Booker's "meta-plot" (as described above), Booker argues that plot types can be further subdivided into the following seven categories. Booker himself borrows most of these definitions of plot types from much earlier writers, such as Aristotle. Here's a closer look at each of the seven types:

- Comedy: In a comedy , characters face a series of increasingly absurd challenges, conflicts, and misunderstandings, culminating in a moment of revelation, when the confusion of the early part of the plot is resolved and the story ends happily. In romantic comedies, the early conflicts in the plot act as obstacles to a happy romantic relationship, but the conflicts are resolved and the plot ends with an orderly conclusion (and often a wedding). A Midsummer Night's Dream , When Harry Met Sally, and Pride and Prejudice are all examples of comedies.

- Tragedy: The plot of a tragedy follows a tragic hero —a likable, well-respected, morally upstanding character who has a tragic flaw or who makes some sort of fatal mistake (both flaw and/or mistake are known as hamartia ). When the tragic hero becomes aware of his mistake (this realization is called anagnorisis ), his happy life is destroyed. This reversal of fate (known as peripeteia ) leads to the plot's tragic ending and, frequently, the hero's death. Booker's tragic plot is based on Aristotle's theory of tragedy, which in turn was based on patterns in classical drama and epic poetry. Antigone , Hamlet , and The Great Gatsby are all examples of tragedies.

- Rebirth: In stories with a rebirth plot, one character is literally or metaphorically imprisoned by a dark force, enchantment, and/or character flaw. Through an act of love, another character helps the imprisoned character overcome the dark force, enchantment, or character flaw. Many stories of rebirth allude to Jesus Christ or other religious figures who sacrificed themselves for others and were resurrected. Beauty and the Beast , The Snow Queen , and A Christmas Carol are all examples of stories with rebirth plots.

- Overcoming the Monster: The hero sets out to fight an evil force and thereby protect their loved ones or their society. The "monster" could be literal or metaphorical: in ancient Greek mythology, Perseus battles the monster Medusa, but in the television show Good Girls Revolt , a group of women files a lawsuit in order to fight discriminatory policies in their workplace. Both examples follow the "Overcoming the Monster" plot, as does the epic poem Beowulf .

- Rags-to-Riches : In a rags-to-riches plot, a disadvantaged person comes very close to gaining success and wealth, but then appears to lose everything, before they finally achieve the happy life they have always deserved. Cinderella and Oliver Twist are classic rags-to-riches stories; movies with rags-to-riches plots include Slumdog Millionaire and Joy .

- The Quest: In a quest story, a hero sets out to accomplish a specific task, aided by a group of friends. Often, though not always, the hero is looking for an object endowed with supernatural powers. Along the way, the hero and their friends face challenges together, but the hero must complete the final stage of the quest alone. The Celtic myth of "The Fisher-King and the Holy Grail" is one of the oldest quest stories; Monty Python and the Holy Grail is a satire that follows the same plot structure; while Heart of Darkness plays with the model of a quest but has the quest end not with the discovery of a treasure or enlightenment but rather with emptiness and disillusionment.

- Voyage and Return: The hero goes on a literal journey to an unfamiliar place where they overcome a series of challenges, then return home with wisdom and experience that help them live a happier life. The Odyssey , Alice's Adventures in Wonderland , Chronicles of Narnia, and Eat, Pray, Love all follow the voyage and return plot.

As you can probably see, there's lots of room for these categories to overlap. This is one of the problems with trying to create any sort of categorization scheme for plots such as this—an issue we'll cover in greater detail below.

The Hero's Journey

The Hero's Journey is an attempt to describe a narrative archetype , or a common plot type that has specific details and structure (also known as a monomyth ). The Hero's Journey plot follows a protagonist's journey from the known to the unknown, and back to the known world again. The journey can be a literal one, as in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, or a purely metaphorical one. Regardless, the protagonist is a changed person by the end of the story. The Hero's Journey structure was first popularized by Joseph Campbell's 1949 book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Later, theorists David Adams Leeming, Phil Cousineau, and Christopher Vogler all developed their own versions of the Hero's Journey structure. Each of these theorists divides The Hero's Journey into slightly different stages (Campbell identifies 17 stages, whereas Vogler finds 12 stages and Leeming and Cousineau use just 8). Below, we'll take a closer look at the 12 stages that Vogler outlines in his analysis of this plot type:

- The Ordinary World: When the story begins, the hero is a seemingly ordinary person living an ordinary life. This section of the story often includes expository details about the story's setting and the hero's background and personality.

- The Call to Adventure: Soon, the hero's ordinary life is interrupted when someone or something gives them an opportunity to go on a quest. Often, the hero is asked to find something or someone, or to defeat a powerful enemy. The call to adventure sometimes, but not always, involves a supernatural event. (In Star Wars: A New Hope , the call to adventure occurs when Luke sees the message from Leia to Obi-Wan Kenobi.)

- The Refusal of the Call: Some heroes are initially reluctant to embark on their journey and instead attempt to continue living their ordinary life. When this refusal takes place, it is followed by another event that prompts the hero to accept the call to adventure (Luke's aunt and uncle getting killed in Star Wars ).

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero meets a mentor: a wiser, more experienced person who gives them advice and guidance. The mentor trains and protects the hero until the hero is ready to embark on the next phase of the journey. (Obi-Wan Kenobi is Luke's mentor in Star Wars .)

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero "crosses the threshold" when they have left the familiar, ordinary world behind. Some heroes are eager to enter a new and unfamiliar world, while others may be uncertain if they are making the right choice, but in either case, once the hero crosses the threshold, there is no way to turn back. (Luke about to enter Mos Eisley, or of Frodo leaving the Shire in Lord of the Rings .)

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: As the hero continues on their journey, they face a series of increasingly difficult "tests" or challenges. Along the way, they acquire friends who help them overcome these challenges, and enemies who attempt to thwart their quest. The hero may defeat some enemies during this phase or find ways to keep them temporarily at bay. These challenges help the reader develop a better a sense of the hero's strengths and weaknesses, and they help the hero become wiser and more experienced. This phase is part of the rising action .

- Approach to the Innermost Cave: At this stage, the hero prepares to face the greatest challenge of the journey, which lies within the "innermost cave." In some stories, the hero must literally enter an isolated and dangerous place and do battle with an evil force; in others, the hero must confront a fear or face an internal conflict; or, the hero may do both. You can think of the approach to the innermost cave as a second threshold—a moment when the hero faces their doubts and fears and decides to continue on the quest. (Think of Frodo entering Mordor, or Harry Potter entering the Forbidden Forest with the Deathly Hallows, ready to confront Lord Voldemort.)

- The Ordeal: The ordeal is the greatest challenge that the hero faces. It may take the form of a battle or physically dangerous task, or it may represent a moral or personal crisis that threatens to destroy the hero. Earlier (in the "Tests, Allies, and Enemies" phase), the hero might have overcome challenges with the help of friends, but the hero must face the ordeal alone. The outcome of the ordeal often determines the fate of the hero's loved ones, society, or the world itself. In many stories, the ordeal involves a literal or metaphorical resurrection, in which the hero dies or has a near-death experience, and is reborn with new knowledge or abilities. This constitutes the climax of the story.

- Reward: After surviving the ordeal, the hero receives a reward of some kind. Depending on the story, it may come in the form of new wisdom and personal strengths, the love of a romantic interest, a supernatural power, or a physical prize. The hero takes the reward or rewards with them as they return to the ordinary world.

- The Road Back: The hero begins to make their way home, either by retracing their steps or with the aid of supernatural powers. They may face a few minor challenges or setbacks along the way. This phase is part of the falling action .

- The Resurrection: The hero faces one final challenge in which they must use all of the powers and knowledge that they have gained throughout their journey. When the hero triumphs, their rebirth is completed and their new identity is affirmed. This phase is not present in all versions of the hero's journey.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero reenters the ordinary world, where they find that they have changed (and perhaps their home has changed too). Among the things they bring with them when they return is an "elixir," or something that will transform their ordinary life for the better. The elixir could be a literal potion or gift, or it may take the form of the hero's newfound perspective on life: the hero now possesses love, forgiveness, knowledge, or another quality that will help them build a better life.

Other Genre-Specific Plots

Apart from the plot types described above (the "Hero's Journey" and Booker's seven basic plots), there are a couple common plot types worth mentioning. When a story uses one of the following plots, it usually means that it belongs to a specific genre of literature—so these plot structures can be thought of as being specific to their respective genres.

- Mystery : A story that centers around the solving of a baffling crime—especially a murder. The plot structure of a mystery can often be described using Freytag's pyramid (i.e., it has exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement), but the plots of mysteries also tend to follow other, more genre-specific conventions, such as the gradual discovery of clues culminating in the revelation of the culprit's identity as well as their motive. In a typical story (i.e., a non-mystery) key characters and their motives are usually revealed before the central conflict arises, not after.

- Bindungsroman : A story that shows a young protagonist's journey from childhood to adulthood (or immaturity to maturity), with a focus on the trials and misfortunes that affect the character's growth. The term "coming-of-age novel" is sometimes used interchangeably with Bildungsroman. This is not necessarily incorrect—in most cases the terms can be used interchangeably—but Bildungsroman carries the connotation of a specific and well-defined literary tradition, which tends to follow certain genre-specific conventions (for example, the main character often gets sent away from home, falls in love, and squanders their fortune). The climax of the Bildungsroman typically coincides with the protagonist reaching maturity.

Other Attempts to Classify Types of Plots

In addition to Freytag, Booker, and Campbell, many other theorists and literary critics have created systems classifying different kinds of plot structures. Among the best known are:

- William Foster-Harris, who outlined three archetypal plot structures in The Basic Patterns of Plot

- Ronald R. Tobias, who wrote a book claiming there are 20 Master Plots

- Georges Polti, who argued there are in fact Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations

- Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch, who in the early twentieth century outlined seven types of plot

And then there are the more atypical approaches to classifying the different types of plots:

- In 1965, the University of Chicago rejected Kurt Vonnegut's college thesis, which claimed that folktales and fairy tales shared common structures, or "shapes," including "man in a hole," "boy gets girl" and "Cinderella." He went on to write Slaughterhouse-Five , a novel which subverts traditional narrative structures, and later developed a lecture based on his failed thesis .

- Two recent studies, led by University of Nebraska professor Matthew Jockers and researchers at the University of Adelaide and the University of Vermont respectively, have used machine learning to analyze the plot structures and emotional ups-and-downs of stories. Both projects concluded that there are six types of stories.

Criticism of Efforts to Categorize Plot Types

Some critics argue that though archetypal plot structures can be useful tools for both writers and readers, we shouldn't rely on them too heavily when analyzing a work of literature. One such skeptic is New York Times book critic Michiko Kakutani, who in a 2005 review described Christopher Booker's Seven Basic Plots as "sometimes absorbing and often blockheaded." Kakutani writes that while Booker finds interesting ways to categorize stories by plot type, he is too fixated on finding stories that fit these plot types perfectly. As a result, Booker tends to idealize overly simplistic stories (and Hollywood films in particular), instead of analyzing more complex stories that may not fit the conventions of his seven plot types. Kakutani argues that, as a result of this approach, Booker undervalues modern and contemporary writers who structure their plots in different and innovative ways.

Kakutani's argument is a reminder that while some great works of literature may follow archetypal plot structures, they may also have unconventional plot structures that defy categorization. Authors who use nonlinear structures or multiple narrators often intentionally create stories that do not perfectly fit any of the "plot types" discussed above. William Faulker's The Sound and the Fury and Jennifer Egan's A Visit From the Goon Squad are both examples of this kind of work. Even William Shakespeare, who wrote many of his plays following the traditional structures for tragedies and comedies, authored several "problem plays," which many scholars struggle to categorize as strictly tragedy or comedy: All's Well That Ends Well , Measure for Measure , Troilus and Cressida, The Winter's Tale , Timon of Athens, and The Merchant of Venice are all examples of "problem plays."

Plot Examples

The following examples are representative of some of the most common types of plot.

The "Hero's Journey" Plot in The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

The plot of The Hobbit closely follows the structure of a typical hero's journey.

- The Ordinary World: At the beginning of The Hobbit , the story's hero, Bilbo Baggins, is living a comfortable life alongside his fellow hobbits in the Shire. (Hobbits are short, human-like creatures predisposed to peaceful, domestic routines.)

- The Call to Adventure: The wizard Gandalf arrives in the Shire with a band of 13 dwarves and asks Bilbo to go with them to Lonely Mountain in order to reclaim the dwarves' treasure, which has been stolen by the dragon Smaug.

- The Refusal of the Call: At first, Bilbo refuses to join Gandalf and the dwarves, explaining that it isn't in a hobbit's nature to go on adventures.

- Meeting the Mentor: Gandalf, who serves as Bilbo's mentor throughout The Hobbit, persuades Bilbo to join the dwarves on their journey.

- Cross the Threshold: Gandalf takes Bilbo to meet the dwarves at the Green Dragon Inn in Bywater, and the group leaves the Shire together.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: Bilbo faces many challenges and trials on the way to the Lonely Mountain. Early in the trip, they are kidnapped by trolls and are rescued by Gandalf. Bilbo takes an elvish dagger from the trolls' supply of weapons that he uses throughout the rest of the journey. Soon Bilbo and the dwarves are captured by goblins, but they are rescued by Gandalf who also kills the Great Goblin. Later, Bilbo finds a magical ring (which becomes the focus of the Lord of the Rings books), and when the dwarves are captured later in the journey (once by giant spiders and once by elves), Bilbo uses the ring and the dagger to rescue them. Finally, Bilbo and the dwarves arrive at Lake Town, near the Lonely Mountain.

- Approach to the Innermost Cave: Bilbo and the dwarves makes his way from Lake Town to the Lonely Mountain, where the dragon Smaug is guarding the dwarves' treasure. Bilbo alone is brave enough to enter the Smaug's lair. Bilbo steals a cup from Smaug, and also learns that Smaug has a weak spot in his scaly armor. Enraged at Bilbo's theft, Smaug flies to Lake-Town and devastates it, but is killed by a human archer who learns of Smaug's weak spot from a bird that overheard Bilbo speaking of it.

- The Ordeal: After Smaug's death, elves and humans march to the Lonely Mountain to claim what they believe is their portion of the treasure (as Smaug plundered from them, too). The dwarves refuse to share the treasure and a battle seems evident, but Bilbo steals the most beautiful gem from the treasure and gives it to the humans and elves. The greedy dwarves banish Bilbo from their company. Meanwhile, an army of wargs (magical wolves) and goblins descend on the Lonely Mountain to take vengeance on the dwarves for the death of the Great Goblin. The dwarves, humans, and elves form an alliance to fight the wargs and goblins, and eventually triumph, though Bilbo is knocked unconscious for much of the battle. (It might seem odd that Bilbo doesn't participate in the battle, but that fact also seems to suggest that the true ordeal of the novel was not the battle but rather Bilbo's moral choice to steal the gem and give it to the men and elves to counter the dwarves growing greed.)

- Reward: The victorious dwarves, humans, and elves share the treasure among themselves, and Bilbo receives a share of the treasure, which he takes home, along with the dagger and the ring.

- The Road Back: It takes Bilbo and Gandalf nearly a year to travel back to the Shire. During that time they e-visit with some of the people they met on their journey out and have many adventures, though none are as difficult as those they undertook on the way to the Lonely Mountain.

- The Resurrection: Bilbo's return to the Shire as a changed person is underlined by the fact that he has been away so long, the other hobbits in the Shire believe that he has died and are preparing to sell his house and belongings.

- Return with the Elixir: Bilbo returns to the shire with the ring, the dagger, and his treasure—enough to make him rich. He also has his memories of the adventure, which he turns into a book.

Other examples of the Hero's Journey Plot Structure:

- Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

- The Epic of Gilgamesh

- The Martian by Andy Weir

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- The Iliad by Homer

The Comedic Plot in Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare's play, Twelfth Night , is generally described as a comedy and follows what Booker would call comedic plot structure. At the beginning of the play, the protagonist, Viola is shipwrecked far from home in the kingdom of Illyria. Her twin brother, Sebastian, appears to have died in the storm. Viola disguises herself as a boy, calls herself Cesario, and gets a job as the servant of Count Orsino, who is in love with the Lady Olivia. When Orsino sends Cesario to deliver romantic messages to Olivia on his behalf, Olivia falls in love with Cesario. Meanwhile, Viola falls in love with Orsino, but she cannot confess her love without revealing her disguise.

In another subplot, Olivia's uncle Toby and his friend Sir Andrew Aguecheek persuade the servant Maria to play a prank convincing another servant, Malvolio, that Olivia loves him. The plot thickens when Sebastian (Viola's lost twin) arrives in town and marries Olivia, who believes she is marrying Cesario. At the end of the play, Viola is reunited with her brother, reveals her identity, and confesses her love to Orsino, who marries her. In spite of the chaos, misunderstandings, and challenges the characters face in the early part of the plot—a source of much of the play's humor— Twelfth Night reaches an orderly conclusion and ends with two marriages.

Other examples of comedic plot structure:

- Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare

- A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare

- Love's Labor's Lost by William Shakespeare

- Emma by Jane Austen

- Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Lysistrata by Aristophanes

- The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde

The Tragic Plot in Macbeth by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare's play Macbeth follows the tragic plot structure. The tragic hero , Macbeth, is a Scottish nobleman, who receives a prophecy from three witches saying that he will become the Thane of Cawdor and eventually the King. After King Duncan makes Macbeth Thane of Cawdor, Lady Macbeth persuades her husband to fulfill the prophecy by secretly murdering Duncan. He does, and is named King. Later, to ensure that Macbeth will remain king, they also order the assassination of the nobleman Banquo, his son, and the wife and children of the nobleman Macduff. However, as Macbeth protects his throne in ever more bloody ways, Lady Macbeth begins to go mad with guilt. Macbeth consults the witches again, and they reassure him that "no man from woman born can harm Macbeth" and that he will not be defeated until the "wood begins to move" to Dunsinane castle. Therefore, Macbeth is reassured that he is invincible. Lady Macbeth never recovers from her guilt and commits suicide, and Macbeth feels numb and empty, even as he is certain he can never be killed. Meanwhile an army led by Duncan's son Malcolm, their number camouflaged by the branches they carry, so that they look like a moving forest, approaches Dunsinane. In the fighting Macduff reveals he was born by cesarian section, and kills Macbeth.

Macbeth's mistake ( hamartia ) is his unrelenting ambition to be king, and his trust in the witches' prophecies. He realizes his mistake in a moment of anagnorisis when the forest full of camouflaged soldiers seems to be moving, and he experiences a reversal of fate ( peripeteia ) when he is defeated by Macduff.

Other examples of tragic plot structure:

- Antigone by Sophocles

- Oedipus at Colonus by Sophocles

- Agamemnon by Aeschylus

- The Libation Bearers by Aeschylus

- The Eumenides by Aeschylus

- Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

- Hamlet by William Shakespeare

- Othello by William Shakespeare

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

- The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The "Rebirth" Plot in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens' novel A Christmas Carol is an example of the "rebirth" plot. The novel's protagonist is the miserable, selfish businessman Ebenezer Scrooge, who mistreats his clerk, Bob Cratchit, who is a loving father struggling to support his family. Scrooge scoffs at the notion that Christmas is a time for joy, love, and generosity. But on Christmas Eve, he is visited by the ghost of his deceased business partner, who warns Scrooge that if he does not change his ways, his spirit will be condemned to wander the earth as a ghost. Later that night, he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present, and Christmas Yet to Come. With these ghosts, Scrooge revisits lonely and joyful times of his youth, sees Cratchit celebrating Christmas with his loved ones, and finally foresees his own lonely death. Scrooge awakes on Christmas morning and resolves to change his ways. He not only celebrates Christmas with the Cratchits, but embraces the Christmas spirit of love and generosity all year long. By the end of the novel, Scrooge has been "reborn" through acts of generosity and love.

Other examples of "rebirth" plot structure:

- The Winter's Tale by William Shakespeare

- The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

- The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood

- Beloved by Toni Morrison

- Snow White by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

- The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Anderson

- Beauty and the Beast by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve

The "Overcoming the Monster" Plot in Beowulf

The Old English epic poem, Beowulf , follows the structure of an "overcoming the monster" plot. In fact, the poem's hero, Beowulf, defeats not just one monster, but three. As a young warrior, Beowulf slays Grendel, a swamp-dwelling demon who has been raiding the Danish king's mead hall. Later, when Grendel's mother attempts to avenge her son's death, Beowulf kills her, too. Beowulf eventually becomes king of the Geats, and many years later, he battles a dragon who threatens his people. Beowulf manages to kill the dragon, but dies from his wounds, and is given a hero's funeral. Three times, Beowulf succeeds in protecting his people by defeating a monster.

Other examples of the overcoming the monster plot structure:

- Dracula by Bram Stoker

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling

The "Rags-to-Riches" Plot in Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë's novel Jane Eyre is an example of a "rags-to-riches" plot. The protagonist, Jane, is a mistreated orphan who is eventually sent away to a boarding school where students are severely mistreated. Jane survives the school and goes on to become a governess at Thornfield Manor, where Jane falls in love with Mr. Rochester. The two become engaged, but on their wedding day, Jane discovers that Rochester's first wife, Bertha, has gone insane and is imprisoned in Thornfield's attic. She leaves Rochester and ends up finding long-lost cousins. After a time, her very religious cousin, St. John, proposes to her. Jane almost accepts, but then rejects the proposal. She returns to Thornfield to discover that Bertha started a house fire and leapt off the roof of the burning building to her death, and that Rochester had been blinded by the fire in an attempt to save Bertha. Jane and Rochester marry, and live a quiet and happy life together. Jane begins the story with nothing, seems poised to achieve true happiness before losing everything, but ultimately has a happy ending.

Other examples of the rags-to-riches plot structure:

- Cinderella by Charles Perrault

- David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

- Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

- The Once and Future King by T.H. White

- Villette by Charlotte Brontë

- Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw

- Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackery

The Quest Plot in Siddhartha by Herman Hesse

Siddhartha , by Herman Hesse, follows the structure of the "quest" plot. The novel's protagonist, Siddartha, leaves his hometown in search of spiritual enlightenment, accompanied by his friend, Govinda. On their journey, they join a band of holy men who seek enlightenment through self-denial, and later, they study with a group of Bhuddists. Disillusioned with religion, Siddartha leaves Govinda and the Bhuddists behind and takes up a hedonistic lifestyle with the beautiful Kamala. Still unsatisfied with his life, he considers suicide in a river, but instead decides to apprentice himself to the man who runs the ferry boat. By studying the river, Siddhartha eventually obtains enlightenment.

Other examples of the quest plot structure:

- Candide by Voltaire

- Don Quixote by Migel de Cervantes

- A Passage to India by E.M. Forster

- The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

- Perceval by Chrétien

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling

The "Voyage and Return" Plot in Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston's novel Their Eyes Were Watching God follows what Booker would describe as a voyage and return plot structure. The plot follows the hero, Janie, as she seeks love and happiness. The novel begins and ends in Eatonville, Florida, where Janie was brought up by her grandmother. Janie has three romantic relationships, each better than the last. She marries a man named Logan Killicks on her grandmother's advice, but she finds the marriage stifling and she soon leaves him. Janie's second, more stable marriage to the prosperous Joe Starks lasts 20 years, but Janie does not feel truly loved by him. After Joe dies, she marries Tea Cake, a farm worker who loves, respects, and cherishes her. They move to the Everglades and live there happily for just over a year, when Tea Cake dies of rabies after getting bitten by a dog during a hurricane. Janie mourns Tea Cake's death, but returns to Eatonville with a sense of peace: she has known true love, and she will always carry her memories of Tea Cake with her. Her journey and her return home have made her stronger and wiser.

Other examples of the voyage and return plot structure:

- The Odyssey by Homer

- Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

- Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

- By the Waters of Babylon by Stephen Vincent Benét

Other Helpful Plot Resources

- What Makes a Hero? Check out this awesome video on the hero's journey from Ted-Ed.

- The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations : Visit Wikipedia for an overview of George Polti's theory of dramatic plot structure.

- Why Tragedies Are Alluring : Learn more about Aristotle's tragic structure, ancient Greek and Shakespearean tragedy, and contemporary tragic plots.

- The Wikipedia Page on Plot: A basic but helpful overview of plots.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Bildungsroman

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

- Falling Action

- Rising Action

- Tragic Hero

- Personification

- Climax (Plot)

- Rhyme Scheme

- Blank Verse

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, what is the plot of a story the 5 parts of the narrative.

General Education

When we talk about stories, we tend to use the word "plot." But what is plot exactly? How does it differ from a story, and what are the primary features that make up a well-written plot? We answer these questions here and show you real plot examples from literature . But first, let’s take a look at the basic plot definition.

What Is Plot? Definition and Overview

What is the plot of a story? The answer is pretty simple, actually.

Plot is the way an author creates and organizes a chain of events in a narrative. In short, plot is the foundation of a story. Some describe it as the "what" of a text (whereas the characters are the "who" and the theme is the "why").

This is the basic plot definition. But what does plot do ?

The plot must follow a logical, enticing format that draws the reader in. Plot differs from "story" in that it highlights a specific and purposeful cause-and-effect relationship between a sequence of major events in the narrative.

In Aspects of the Novel , famed British novelist E. M. Forster argues that instead of merely revealing random events that occur within a text (as "story" does), plot emphasizes causality between these events:

"We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. 'The king died and then the queen died,' is a story. 'The king died, and then the queen died of grief' is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it."

Authors typically develop their plots in ways that are most likely to pique the reader’s interest and keep them invested in the story. This is why many plots follow the same basic structure. So what is this structure exactly?

What Is Plot Structure?

All plots follow a logical organization with a beginning, middle, and end—but there’s a lot more to the basic plot structure than just this. Generally speaking, every plot has these five elements in this order :

- Exposition/introduction

- Rising action

- Climax/turning point

- Falling action

- Resolution/denouement

#1: Exposition/Introduction

The first part of the plot establishes the main characters/protagonists and setting. We get to know who’s who, as well as when and where the story takes place. At this point, the reader is just getting to know the world of the story and what it’s going to be all about.

Here, we’re shown what normal looks like for the characters .

The primary conflict or tension around which the plot revolves is also usually introduced here in order to set up the course of events for the rest of the narrative. This tension could be the first meeting between two main characters (think Pride and Prejudice ) or the start of a murder mystery, for example.

#2: Rising Action

In this part of the plot, the primary conflict is introduced (if it hasn’t been already) and is built upon to create tension both within the story and the reader , who should ideally be feeling more and more drawn to the text. The conflict may affect one character or multiple characters.

The author should have clearly communicated to the reader the stakes of this central conflict. In other words, what are the possible consequences? The benefits?

This is the part of the plot that sets the rest of the plot in motion. Excitement grows as tensions get higher and higher, ultimately leading to the climax of the story (see below).

For example, in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone , the rising action would be when we learn who Voldemort is and lots of bad things start happening, which the characters eventually realize are all connected to Voldemort.

#3: Climax/Turning Point

Arguably the most important part of a story, the climax is the biggest plot point , which puts our characters in a situation wherein a choice must be made that will affect the rest of the story.

This is the critical moment that all the rising action has been building up to, and the point at which the overarching conflict is finally addressed. What will the character(s) do, and what will happen as a result? Tensions are highest here, instilling in the reader a sense of excitement, dread, and urgency.

In classic tales of heroes, the climax would be when the hero finally faces the big monster, and the reader is left to wonder who will win and what this outcome could mean for the other characters and the world as a whole within the story.

#4: Falling Action

This is when the tension has been released and the story begins to wind down. We start to see the results of the climax and the main characters’ actions and get a sense of what this means for them and the world they inhabit. How did their choices affect themselves and those around them?

At this point, the author also ties up loose ends in the main plot and any subplots .

In To Kill a Mockingbird , we see the consequences of the trial and Atticus Finch’s involvement in it: Tom goes to jail and is shot and killed, and Scout and Jem are attacked by accuser Bob Ewell who blames their father for making a fool out of him during the trial.

#5: Resolution/Denouement

This final plot point is when everything has been wrapped up and the new world—and the new sense of normalcy for the characters—has been established . The conflict from the climax has been resolved, and all loose ends have been neatly tied up (unless the author is purposely setting up the story for a sequel!).

There is a sense of finality and closure here , making the reader feel that there is nothing more they can learn or gain from the narrative.

The resolution can be pretty short—sometimes just a paragraph or so—and might even take the form of an epilogue , which generally takes place a while after the main action and plot of the story.

Be careful not to conflate "resolution" with "happy ending"—resolutions can be tragic and entirely unexpected, too!

In Romeo and Juliet , the resolution is the point at which the family feud between the Capulets and Montagues is at last put to an end following the deaths of the titular lovers.

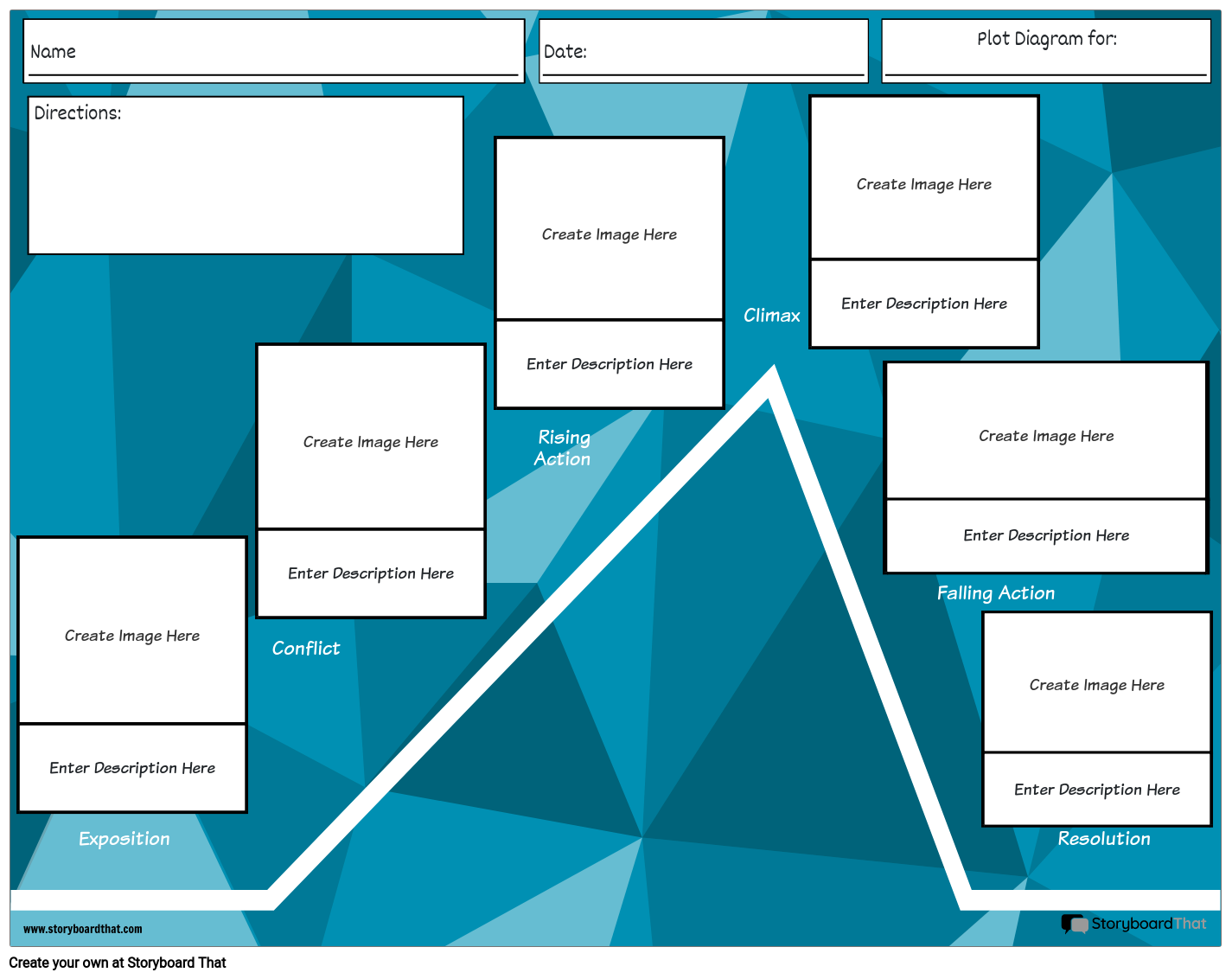

What Is a Plot Diagram?

Many people use a plot diagram to help them visualize the plot definition and structure . Here’s what a basic plot diagram looks like:

The triangular part of the diagram indicates changing tensions in the plot. The diagram begins with a flat, horizontal line for the exposition , showing a lack of tension as well as what is normal for the characters in the story.

This elevation changes, however, with the rising action , or immediately after the conflict has been introduced. The rising action is an increasing line (indicating the building of tension), all the way up until it reaches the climax —the peak or turning point of the story, and when everything changes.

The falling action is a decreasing line, indicating a decline in tension and the wrapping up of the plot and any subplots. After, the line flatlines once more into a resolution —a new sense of normal for the characters in the story.

You can use the plot diagram as a reference when writing a story and to ensure you have all major plot points.

4 Plot Examples From Literature

While most plots follow the same basic structure, the details of stories can vary quite a bit! Here are four plot examples from literature to give you an idea of how you can use the fundamental plot structure while still making your story entirely your own.

#1: Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Exposition: The ghost of Hamlet’s father—the former king—appears one night instructing his son to avenge his death by killing Claudius, Hamlet’s uncle and the current king.

Rising Action: Hamlet struggles to commit to avenging his father’s death. He pretends to go crazy (and possibly becomes truly mad) to confuse Claudius. Later, he passes up the opportunity to kill his uncle while he prays.

Climax: Hamlet stabs and kills Polonius, believing it to be his uncle. This is an important turning point at which Hamlet has committed himself to both violence and revenge. (Another climax can be said to be when Hamlet duels Laertes.)

Falling Action: Hamlet is sent to England but manages to avoid execution and instead returns to Denmark. Ophelia goes mad and dies. Hamlet duels Laertes, ultimately resulting in the deaths of the entire royal family.

Resolution: As he lay dying, Hamlet tells Horatio to make Fortinbras the king of Denmark and to share his story. Fortinbras arrives and speaks hopefully about the future of Denmark.

#2: Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Exposition: Lockwood arrives at Wuthering Heights to meet with Heathcliff, a wealthy landlord, about renting Thrushcross Grange, another manor just a few miles away. While staying overnight, he sees the ghost of a woman named Catherine. After settling in at the Grange, Lockwood asks the housekeeper, Nelly Dean, to relay to him the story of Heathcliff and the Heights.

Rising Action: Most of the rising action takes place in the past when Catherine and Heathcliff were young. We learn that the two children were very close. One day, a dog bite forces Catherine to stay for several weeks at the Grange where the Lintons live, leading her to become infatuated with the young Edgar Linton. Feeling hurt and betrayed, Heathcliff runs away for three years, and Catherine and Edgar get married. Heathcliff then inherits the Heights and marries Edgar’s sister, Isabella, in the hopes of inheriting the Grange as well.

Climax: Catherine becomes sick, gives birth to a daughter named Cathy, and dies. Heathcliff begs Catherine to never leave him, to haunt him—even if it drives him mad.

Falling Action: Many years pass in Nelly's story. A chain of events allows Heathcliff to gain control of both the Heights and the Grange. He then forces the young Cathy to live with him at the Heights and act as a servant. Lockwood leaves the Grange to return to London.

Resolution: Six months later, Lockwood goes back to see Nelly and learns that Heathcliff, still heartbroken and now tired of seeking revenge, has died. Cathy and Hareton fall in love and plan to get married; they inherit the Grange and the Heights. Lockwood visits the graves of Catherine and Heathcliff, noting that both are finally at peace.

#3: Carrie by Stephen King

Exposition: Teenager Carrie is an outcast and lives with her controlling, fiercely religious mother. One day, she starts her period in the showers at school after P.E. Not knowing what menstruation is, Carrie becomes frantic; this causes other students to make fun of her and pelt her with sanitary products. Around this time, Carrie discovers that she has telekinetic powers.

Rising Action: Carrie practices her telekinesis, which grows stronger. The students who previously tormented Carrie in the locker room are punished by their teacher. One girl, Sue, feels remorseful and asks her boyfriend, Tommy, to take Carrie to the prom. But another girl, Chris, wants revenge against Carrie and plans to rig the prom queen election so that Carrie wins. Carrie attends the prom with Tommy and things go well—at first.

Climax: After being named prom queen, Carrie gets onstage in front of the entire school only to be immediately drenched with a bucket of pig’s blood, a plot carried out by Chris and her boyfriend, Billy. Everybody laughs at Carrie, who goes mad and begins using her telekinesis to start fires and kill everyone in sight.

Falling Action: Carrie returns home and is attacked by her mother. She kills her mother and then goes outside again, this time killing Chris and Billy. As Carrie lay dying, Sue comes over to her and Carrie realizes that Sue never intended to hurt her. She dies.

Resolution: The survivors in the town must come to terms with the havoc Carrie wrought. Some feel guilty for not having helped Carrie sooner; Sue goes to a psychiatric hospital. It’s announced that there are no others like Carrie, but we are then shown a letter from a mother discussing her young daughter’s telekinetic abilities.

#4: Twilight by Stephenie Meyer

Exposition: Bella Swan is a high school junior who moves to live with her father in a remote town in Washington State. She meets a strange boy named Edward, and after an initially awkward meeting, the two start to become friends. One day, Edward successfully uses his bare hands to stop a car from crushing Bella, making her realize that something is very different about this boy.

Rising Action: Bella discovers that Edward is a vampire after doing some research and asking him questions. The two develop strong romantic feelings and quickly fall in love. Bella meets Edward’s family of vampires, who happily accept her. When playing baseball together, however, they end up attracting a gang of non-vegetarian vampires. One of these vampires, James, notices that Bella is a human and decides to kill her. Edward and his family work hard to protect Bella, but James lures her to him by making her believe he has kidnapped her mother.

Climax: Tricked by James, Bella is attacked and fed on. At this moment, Edward and his family arrive and kill James. Bella nearly dies from the vampire venom in her blood, but Edward sucks it out, saving her life.

Falling Action: Bella wakes up in the hospital, heavily injured but alive. She still wants to be in a relationship with Edward, despite the risks involved, and the two agree to stay together.

Resolution: Months later, Edward takes Bella to the prom. The two have a good time. Bella tells Edward that she wants him to turn her into a vampire right then and there, but he refuses and pretends to bite her neck instead.

Conclusion: So What Is the Plot of a Story?

What is plot? Basically, it’s the chain of events in a story. These events must be purposeful and organized in a logical manner that entices the reader, builds tension, and provides a resolution.

All plots have a beginning, middle, and end, and usually contain the following five points in this order:

#1: Exposition/introduction #2: Rising action #3: Climax/turning point #4: Falling action #5: Resolution/denouement

Sketching out a plot diagram can help you visualize your story and get a clearer sense for where the climax is, what tensions you'll need to have in order to build up to this turning point, and how you can offer a tight conclusion to your story.

What’s Next?

What is plot? A key literary element as it turns out. Learn about other important elements of literature in our guide. We've also got a list of top literary devices you should know.

Working on a novel? Then you will definitely want to know what kinds of tone words you can use , how imagery works , what the big difference between a simile and a metaphor is , and how to write an epilogue .

Interested in writing poetry? Then check out our picks for the 20 most critical poetic devices .

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Definition of Plot

Plot is a literary device that writers use to structure what happens in a story . However, there is more to this device than combining a sequence of events. Plots must present an event, action, or turning point that creates conflict or raises a dramatic question, leading to subsequent events that are connected to each other as a means of “answering” the dramatic question and conflict. The arc of a story’s plot features a causal relationship between a beginning, middle, and end in which the conflict is built to a climax and resolved in conclusion .

For example, A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens features one of the most well-known and satisfying plots of English literature.

I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.

Dickens introduces the protagonist , Ebenezer Scrooge, who is problematic in his lack of generosity and participation in humanity–especially during the Christmas season. This conflict results in three visitations by spirits that help Scrooge’s character and the reader understand the causes for the conflict. The climax occurs as Scrooge’s dismal future is foretold. The above passage reflects the second chance given to Scrooge as a means of changing his future as well as his present life. As the plot of Dickens’s story ends, the reader finds resolution in Scrooge’s changed attitude and behavior. However, if any of the causal events were removed from this plot, the story would be far less valuable and effective.

Common Examples of Plot Types

In general, the plot of a literary work is determined by the kind of story the writer intends to tell. Some elements that influence the plot are genre , setting , characters, dramatic situation, theme , etc. However, there are seven basic, common examples of plot types:

- Tragedy : In a tragic story, the protagonist typically experiences suffering and a downfall, The plot of the tragedy almost always includes a reversal of fortune, from good to bad or happy to sad.

- Comedy : In a comedic story, the ending is generally not tragic. Though characters in comic plots may be flawed, their outcomes are not usually painful or destructive.

- Journey of the Hero : In general, the plot of a hero’s journey features two elements: recognition and a situation reversal. Typically, something happens from the outside to inspire the hero, bringing about recognition and realization. Then, the hero undertakes a quest to solve or reverse the situation.

- Rebirth : This plot type generally features a character’s transformation from bad to good. Typically, the protagonist carries their tragic past with them which results in negative views of life and poor behavior. The transformation occurs when events in the story help them see a better worldview.

- Rags-to-Riches : In this common plot type, the protagonist begins in an impoverished, downtrodden, or struggling state. Then, story events take place (magical or realistic) that lead to the protagonist’s success and usually a happy ending.

- Good versus Evil : This plot type features a generally “good” protagonist that fights a typically “evil” antagonist . However, both the protagonist and antagonist can be groups of characters rather than simply individuals, all with the same goal or mission.

- Voyage/Return : In this plot type, the main character goes from point A to point B and back to point A. In general, the protagonist sets off on a journey and returns to the start of their voyage, having gained wisdom and/or experience.

Aristotle’s Plot Structure Formula

Though this principle may seem obvious to modern readers, in his work Poetics , Aristotle first developed the formula for plot structure as three parts: beginning, middle, and end. Each of these parts is purposeful, integral, and challenging for writers. It

can be difficult for writers to create an effective plot device in terms of making decisions about how a story begins, what happens in the middle, and how it ends. Here is a further explanation of Aristotle’s plot structure formula:

- Beginning : The beginning of a story holds great value. It has to capture the reader’s attention, introduce the characters, setting, and the central conflict.

- Middle : The middle of a plot requires movement toward the conclusion of the story, as well as plot points, obstacles, or various subplots along the way to maintain the reader’s interest and infuse value and meaning into the story.

- End : The end of a story brings about the conclusion and resolution of the conflict, generally leaving the reader with a sense of satisfaction, value, and deeper understanding.

Freytag’s Pyramid

In 1863, Gustav Freytag (a German novelist) published a book that expanded Aristotle’s concept of plot. Freytag added two components: rising action and falling action . This dramatic arc of plot structure, termed Freytag’s Pyramid, is the most prevalent depiction of plot as a literary device. Here are the elements of Freytag’s Pyramid:

- Exposition : the beginning of the story, in which the writer establishes or introduces pertinent information such as setting, characters, dramatic situation, etc.

- Rising Action : increased tension as a result of the central conflict.

- Climax (middle) : pinnacle and/or turning point of the plot.

- Falling Action : also referred to as denouement , begins with consequences resulting from the climax and moves towards the conclusion.

- Resolution : end of the story.

Differences Between Narrative and Plot

Plot and narrative are both literary devices that are often used interchangeably. However, there is a distinction between them when it comes to storytelling. Plot involves causality and a connected series of events that make up a story. Plot refers to what actions and/or events take place in a story and the causal relationship between them.

Narrative encompasses aspects of a story that include choices by the writer as to how the story is told, such as point of view , verb tense, tone , and voice . Therefore, the plot is a more objective literary device in terms of a story’s definitive events. Narrative is more subjective as a literary device in that there are many choices a writer can make as to how the same plot is told and revealed to the reader.

Three Basic Patterns of Plot – William Foster-Harris

In his book, The Basic Patterns of Plot, Foster-Harris presented three types of plot.

- Happy Ending Plot: These plots end on a happy note when the central character makes a sacrifice or resolves the conflict. Also, there is a positive and light-hearted ending to the story.

- Unhappy Ending: In this type of plot, the central character acts logically that seems right and fails to completely resolve the conflict. The story also might end with conflict resolution but one or more characters lose something or sacrifice something.

- Tragedy : This type of plot poses questions by the end about the sadness and its reason as the central character does not make a choice for a sacrifice, or otherwise.

Master Plots – Ronald R. Tobias

The term master plots occur in the book of Ronald R. Tobias, 20 Master Plots . Some of the important ones are Quest, Adventure , Pursuit, and Rescue. These are followed by Escape, Revenge, The riddle , Rivalry, and Underdog, while Temptation, Metamorphosis, and Transformation follow them. Some others are Maturing, Love, and Forbidden Love. Sacrifice and Discovery are two other master plots with Wretched Excess, Ascension, and Descension following them. The important feature of these plots is that they all follow the style their title suggests.

Seven Types of Plots – Jessamyn West

Besides thematic plots, Jessamyn West, a volunteer librarian has listed seven basic and major plots for a story. His argument seems based on the type of characters.

- A woman against nature

- A woman against another woman, or a man against another man

- A woman against the environment or vice versa

- A woman against technology

- A woman against self

- A woman against supernatural elements

- A woman against religion or gods

Why it is Good to Break Traditional Plot Structures

Although most critics are very strict about a story having a plot, it is quite unusual to break the conventional structures and create a new one. This creativity is the hallmarks of a literary piece as breaking the traditional plot structure makes the literary piece in the process a unique addition to the long list of such other pieces. This also makes the writer flout new ideas about plot structures, making him a pioneer in such plots. It often happens in postmodern fiction to break away from traditions in creating plots such as Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut presents a non-linear storyline.

Linear and Non-Linear Plots

These two very simple terms, linear and non-linear in the literary world with reference to plots, define how a plot has been structured. A linear plot is constructed on the idea of chronological order having a clear beginning, a defined middle, and a definite ending. However, when an author, such as the referred novel in the above example shows, breaks away from the normal plot structures, it becomes a non-linear plot. It does not have any beginning or for that matter any ending or middle. It just presents fractured and broken thoughts or incidents in a way that the readers have to construct their own story.

Examples of Plot in Literature

When readers remember a work of literature, whether it’s a novel, short story , play , or narrative poem , their lasting impression often is due to the plot. The cause and effect of events in a plot are the foundation of storytelling, as is the natural arc of a story’s beginning, middle, and end. Literary plots resonate with readers as entertainment, education, and elemental to the act of reading itself. Here are some examples of plot in literature:

Example 1: Romeo and Juliet (Prologue) – William Shakespeare

Two households, both alike in dignity (In fair Verona, where we lay our scene), From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. From forth the fatal loins of these two foes A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life; Whose misadventured piteous overthrows Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife. The fearful passage of their death-marked love And the continuance of their parents’ rage, Which, but their children’s end, naught could remove, Is now the two hours’ traffic of our stage; The which, if you with patient ears attend, What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

In the prologue of Shakespeare’s famous tragedy, the arc of the plot is told–including the outcome of the story. However, though the overall plot is revealed before the story begins, this does not detract from the portrayal of the events in the story and the relationship between their cause and effect. Each character’s action drives forward connected events that build to a climax and then a tragic resolution, so that even if the reader/viewer knows what will happen, the play remains an engaging and memorable literary work.

Example 2: Six-word-long story, often attributed to Ernest Hemingway

For sale, baby shoes, never worn.

This famous six-word short story is attributed to Ernest Hemingway , although there has been no indisputable substantiation that it is his creation. Aside from its authorship, this story demonstrates the power of plot as a literary device and in particular the effectiveness of Aristotle’s formula. Through just six words, the plot of this story has a beginning, middle, and end that readers can identify. In addition, the plot allows readers to interpret the causality of the story’s events depending on the manner in which they view and interpret the narrative.

Example 3: Don Quixote – Miguel de Cervantes

“Destiny guides our fortunes more favorably than we could have expected. Look there, Sancho Panza, my friend , and see those thirty or so wild giants, with whom I intend to do battle and kill each and all of them, so with their stolen booty we can begin to enrich ourselves. This is noble, righteous warfare, for it is wonderfully useful to God to have such an evil race wiped from the face of the earth.” “What giants?” Asked Sancho Panza. “The ones you can see over there,” answered his master, “with the huge arms, some of which are very nearly two leagues long.” “Now look, your grace,” said Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants, but windmills, and what seems to be arms are just their sails, that go around in the wind and turn the millstone.” “Obviously,” replied Don Quijote, “you don’t know much about adventures.”

Don Quixote is considered the first modern novel, and the complexity of its plot is one of the reasons for this distinction. Each event that takes place in this overall hero’s journey is connected to and causes other actions in the story, bringing about a resolution at the end. This novel by de Cervantes features subplots as well, yet the story arc of the character reflects all elements of both Aristotle’s plot formula and Freytag’s Pyramid.

Synonyms of Plot

There are several synonyms that come close to the plot in meanings such as narrative, theme, events, tales, mythos, and subject , yet they are all literary devices in their own right. They do not replace the plot.

Related posts:

Post navigation.

The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

What is Plot? A Writer’s Guide to Creating Amazing Plots

What’s plot? Discover the definition of plot, different types of plots, the various elements of a great plot including Vonnegut’s story shapes!

People are always stopping me on the street and asking, “What is plot? You look like a part-time writer, you should know!” I’m kidding. That never happens. But, if you came here for the basic definition for the plot, we’ve got that for you plus a lot more!

The Definition of Plot

In fiction, a plot is the cause and effect sequence of significant events that make up the story’s narrative. These events can include things like an inciting incident, mid-plot point, climax, and resolution.

But there is so much more to plot than this boring definition. So, today we are going to talk about what plot is all about. Let’s take a deep drive on plot and figure out how to use it for our own stories! We’ll start with types of plot.

Different types of plot

If you google “different types of plot” one of the first hits you’ll get is something like, “the 1,500 basic types of plot!” Needles to say, the subject of plot types can be confusing, and the truth is your plot is what you make it. You don’t have to conform to anyone’s pattern. But, if you help getting started there are plenty of plots diagrams you can use. For this post, we’ll cover the most beneficial ones.

Kurt Vonnegut’s Shape of Stories

A terrific source for outlining different plot types is the Shapes of Stories by famed writer Kurt Vonnegut. In case you’re not familiar, Vonnegut is the author of titles like Slaughterhouse-Five, and Breakfast of Champions. He also wrote a thesis, Shapes of Stories, arguing there were eight basic plot shapes that you could draw on a graph. He describes these story shapes as eight common character arcs.

Below is a short lecture Vonnegut gave on the concept:

The Eight Shapes of Stories

Man in a Hole:

With this plot your main character will get into some serious trouble. This trouble will upend your protagonist’s life and send them spiraling towards rock bottom. Through the plot of your story, the character will make their way out of trouble. By the conclusion the protagonist will be left off better than where they started, having crawled out of the hole.

The hole is usually metaphorical, but by all means, stick your character in a real hole if you want.

Boy Meets Girl :

Or girl meets boy. Like the hole from the example above, the person your character meets can be symbolic. Your character doesn’t have to meet a person; they can find something wonderful or life-changing. The character will experience the awesome benefits of this thing or person they found. Then, as it often does, tragedy strikes.

At some point in the story, your character will lose the wonderful thing they found, and they will become deeply depressed. We’re back in the hole. However, by the story’s conclusion the character will regain the thing they lost. What’s more, they will get it back permanently, and, like with Man in a Hole, they will end better than they started.

From Bad to Worse :

Are you a sadist? Well, do I have the plot for you! From Bad to Worse character arcs are exactly what they sound like. You start your character off in a terrible situation. Then things get gradually worse for them as the story progresses. By the end, your protagonist has lost all hope of things ever getting better. Because they won’t.

This kind of arc makes great horror stories. They also put your readers through the wringer.

Which Way is Up?

Life imitates art in the Which Way is Up story arc. Things are confusing; events are ambiguous. It’s difficult to tell whether a turn of fate will benefit or harm your protagonist. These stories hit close to home, as with a reader’s life, we’re not guaranteed a happy ending.

Great for thrillers and mysteries, this kind of story will keep readers on the edge of their seat.

Creation Story :