An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Understanding, Educating, and Supporting Children with Specific Learning Disabilities: 50 Years of Science and Practice

Elena l. grigorenko.

1 University of Houston, Houston, USA

2 Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, USA

Donald Compton

3 Florida State University, Tallahassee, USA

4 Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA

Richard Wagner

Erik willcutt.

5 University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, USA

Jack M. Fletcher

Specific learning disabilities (SLD) are highly relevant to the science and practice of psychology, both historically and currently, exemplifying the integration of interdisciplinary approaches to human conditions. They can be manifested as primary conditions—as difficulties in acquiring specific academic skills—or as secondary conditions, comorbid to other developmental disorders such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In this synthesis of historical and contemporary trends in research and practice, we mark the 50th anniversary of the recognition of SLD as a disability in the US. Specifically, we address the manifestations, occurrence, identification, comorbidity, etiology, and treatment of SLD, emphasizing the integration of information from the interdisciplinary fields of psychology, education, psychiatry, genetics, and cognitive neuroscience. SLD, exemplified here by Specific Word Reading, Reading Comprehension, Mathematics, and Written Expression Disabilities, represent spectrum disorders each occurring in approximately 5–15% of the school-aged population. In addition to risk for academic deficiencies and related functional social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties, those with SLD often have poorer long-term social and vocational outcomes. Given the high rate of occurrence of SLD and their lifelong negative impact on functioning if not treated, it is important to establish and maintain effective prevention, surveillance, and treatment systems involving professionals from various disciplines trained to minimize the risk and maximize the protective factors for SLD.

Fifty years ago, the US federal government, following an advisory committee recommendation ( United States Office of Education, 1968 ), first recognized specific learning disabilities (SLD) as a potentially disabling condition that interferes with adaptation at school and in society. Over these 50 years, a significant research base has emerged on the identification and treatment of SLD, with greater understanding of the cognitive, neurobiological, and environmental causes of these disorders. The original 1968 definition of SLD remains statutory through different reauthorizations of the 1975 special education legislation that provided free and appropriate public education for all children with disabilities, now referred to as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004). SLD are recognized worldwide as a heterogeneous set of academic skill disorders represented in all major diagnostic nomenclatures, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11, World Health Organization, 2018).

In the US, the SLD category is the largest for individuals who receive federally legislated support through special education. Children are identified as SLD through IDEA when a child does not meet state-approved age- or grade-level standards in one or more of the following areas: oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skills, reading fluency, reading comprehension, mathematics calculation, and mathematics problem solving. Although children with SLD historically represented about 50% of the children aged 3–21 served under IDEA, percentages have fluctuated across reauthorizations of the special education law, with some decline over the past 10 years ( Figure 1 ).

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), enacted in 1975 as Public Law 94–142, mandates that children and youth ages 3–21 with disabilities be provided a free and appropriate public school education in the least restricted environment. The percentage of children served by federally mandated special education programs, out of total public school enrollment, increased from 8.3 percent to 13.8 percent between 1976–77 and 2004–05. Much of this overall increase can be attributed to a rise in the percentage of students identified as having SLD from 1976–77 (1.8 percent) to 2004–05 (5.7 percent). The overall percentage of students being served in programs for those with disabilities decreased between 2004–05 (13.8 percent) and 2013–14 (12.9 percent). However, there were different patterns of change in the percentages served with some specific conditions between 2004–05 and 2013–14. The percentage of children identified with SLD declined from 5.7 percent to 4.5 percent of the total public school enrollment during this period. This number is highly variable by state: for example, in 2011 it ranged from 2.3% in Kentucky to 13.8% in Puerto Rico, as there is much variability in the procedures used to identify SLD, and disproportional demographic representation. Figure by Janet Croog.

This review is a consensus statement developed by researchers currently leading the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) supported Consortia of Learning Disabilities Research Centers and Innovation Hubs. This consensus is based on the primary studies we cite, as well as the meta-analytic reviews (*), systematic reviews (**), and first-authored books (***) that provide an overview of the science underlying research and practice in SLD (see references). The hope is that this succinct overview of the current state of knowledge on SLD will help guide an agenda of future research by identifying knowledge gaps, especially as the NICHD embarks on a new strategic plan. The research programs on SLD from which this review is derived represent the integration of diverse, interdisciplinary approaches to behavioral science and human conditions. We start with a brief description of the historical roots of the current view of SLD, then provide definitions as well as prevalence and incidence rates, discuss comorbidity between SLD themselves and SLD and other developmental disorders, comment on methods for SLD identification, present current knowledge on the etiology of SLD, and conclude with evidence-based principles for SLD intervention.

Three Historical Strands of Inquiry that Shaped the Current Field of SLD

Three strands of phenomenological inquiry culminated in the 1968 definition and have continued to shape current terminology and conventions in the field of SLD ( Figure 2 ). The first, a medical strand, originated in 1676, when Johannes Schmidt described an adult who had lost his ability to read (but with preserved ability to write and spell) because of a stroke. Interest in this strand reemerged in the 1870s with the publication of a string of adult cases who had lived through a stroke or traumatic brain injury. Subsequent cases involved children who were unable to learn to read despite success in mathematics and an absence of brain injury, which was termed “word blindness” ( W. P. Morgan, 1896 ). These case studies laid the foundation for targeted investigations into the presentation of specific unexpected difficulties related to reading printed words despite typical intelligence, motivation, and opportunity to learn.

A schematic timeline of the three stands of science and practice in the field of SLD. The colors represent the strands (blue—first, yellow—second, and green—third). Blue: provided phenomenological descriptions and generated hypotheses about the gene-brain bases of SLD (specifically, dyslexia or SRD); it also provided the first evidence that the most effective treatment approaches are skill-based and reflect cognitive models of the conditions. Yellow: differentiated SLD from other comorbid conditions. Green: stressed the importance of focusing on SLD in academic settings and developing both preventive and remediational evidence-based approaches to managing these conditions. Due to space constraints, the names of many highly influential scientists (e.g., Marilyn Adams, Joseph Torgesen, Isabelle Liberman, Keith Stanovich, among others) who shaped the field of SLD have been omitted. Figure by Janet Croog.

The second strand is directly related to the formalization of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). Rooted in the work of biologically oriented physicians, the 1952 first edition (DSM-I) referenced a category of chronic brain syndromes of unknown cause that focused largely on behavioral presentations we now recognize as hyperkinesis and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The 1968 DSM-II defined “mild brain damage” in children as a chronic brain syndrome manifested by hyperactive and impulsive behavior with reference to a new category, “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood” if the origin is not considered “organic.” As these categories evolved, they expanded to encompass the academic difficulties experienced by many of these children.

After almost 30 years of research into this general category of “minimal brain dysfunction,” representing “... children of near average, average, or above average general intelligence with certain learning or behavioral disabilities ... associated with deviations of function of the central nervous system.” ( Clements, 1966 , pp. 9–10), the field acknowledged the heterogeneity of these children and the failure of general “one size fits all” interventions. As a result, the 1980 DSM-III formally separated academic skill disorders from ADHD. The 1994 DSM-IV differentiated reading, mathematics, and written expression SLD. The DSM-5 reversed that, merging these categories into one overarching category of SLD (nosologically distinct from although comorbid with ADHD), keeping the notion of specificity by stating that SLD can manifest in three major academic domains (reading, mathematics, and writing).

The third strand originated from the development of effective interventions based on cognitive and linguistic models of observed academic difficulties. This strand, endorsed in the 1960s by Samuel Kirk and associates, viewed SLD as an overarching category of spoken and written language difficulties that manifested as disabilities in reading (dyslexia), mathematics (dyscalculia), and writing (dysgraphia). Advances have been made in understanding the psychological and cognitive texture of SLD, developing interventions aimed at overcoming or managing them, and differentiating these disorders from each other, from other developmental disorders, and from other forms of disadvantage. This work became the foundation of the 1968 advisory committee definition of SLD, which linked this definition with that of minimal brain dysfunction via the same “unexpected” exclusionary criteria (i.e., not attributable primarily to intellectual difficulties, sensory disorders, emotional disturbance, or economic/cultural diversity).

Although its exclusionary criteria were well specified, the definition of SLD did not provide clear inclusionary criteria. Thus, the US Department of Education’s 1977 regulatory definition of SLD included a cognitive discrepancy between higher IQ and lower achievement as an inclusionary criterion. This discrepancy was viewed as a marker for unexpected underachievement and penetrated the policy and practice of SLD in the US and abroad. In many settings, the measurement of such a discrepancy is still considered key to identification. Yet, IDEA 2004 and the DSM-5 moved away from this requirement due to a lack of evidence that SLD varies with IQ and numerous philosophical and technical challenges to the notion of discrepancy (Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2019). IDEA 2004 also permitted an alternative inclusion criterion based on Response-to-Intervention (RTI), in which SLD reflects inadequate response to effective instruction, while the DSM-5 focuses on evidence of persistence of learning difficulties despite treatment efforts.

These three stands of inquiry into SLD use a variety of concepts (e.g., word blindness, strephosymbolia, dyslexia and alexia, dyscalculia and acalculia, dysgraphia and agraphia), which are sometimes differentiated and sometimes used synonymously, generating confusion in the literature. Given the heterogeneity of their manifestation and these diverse historical influences, it has been difficult to agree on the best way to identify SLD, although there is consensus that their core is unexpected underachievement. A source of active research and controversy is whether “unexpectedness” is best identified by applying solely exclusionary criteria (i.e., simple low achievement), inclusionary criteria based on uneven cognitive development (e.g., academic skills lower than IQ or another aptitude measure, such as listening comprehension), or evidence of persisting difficulties (DSM-5) despite effective instruction (IDEA 2004).

Manifestation, Definition, and Etiology

That the academic deficits in SLD relate to other cognitive skills has always been recognized, but the diagnostic and treatment relevance of this connection has remained unclear. A rich literature on cognitive models of SLD ( Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014 ; Fletcher et al., 2019) provides the basis for five central ideas. First, SLD are componential ( Melby-Lervåg, Lyster, & Hulme, 2012 ; Peng & Fuchs, 2016 ): Their academic manifestations arise on a landscape of peaks, valleys, and canyons in various cognitive processes, such that individuals with SLD have weaknesses in specific processes, rather than global intellectual disability ( Morris et al., 1998 ). Second, the cognitive components associated with SLD, just like academic skills and instructional response, are dimensional and normally distributed in the general population ( Ellis, 1984 ), such that understanding typical acquisition should provide insight into SLD and vice versa ( Rayner, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, & Seidenberg, 2001 ). Third, each academic and cognitive component may have a distinct signature in the brain ( Figure 3 ) and genome ( Figure 4 ). These signatures and etiologies likely overlap because they are correlated, but are not interchangeable, as their unique features substantiate the distinctness of various SLD ( Vandermosten, Hoeft, & Norton, 2016 ). Fourth, the overlap at least partially explains their rates of comorbidity ( Berninger & Abbott, 2010 ; Szucs, 2016 ; Willcutt et al., 2013 ). Fifth, deficiencies in these cognitive and academic processes appear to last throughout the lifespan, especially in the absence of intervention ( Klassen, Tze, & Hannok, 2013 ).

Results of meta-analyses of functional neuroimaging studies that exemplify the distribution of activation patterns in different reading- ( A ) and mathematics- ( B ) related networks, corresponding to componential models of the skills. A (Left panel, light blue): A lexical network in the basal occipito-temporal regions and in the left inferior parietal cortex. A (Middle panel, dark blue): A sublexical network, primarily involving regions of the left temporo-parietal lobe extending from the left anterior fusiform region. A (Right panel): Activation likelihood estimation map of foci from the word>pseudowords (light blue) and pseudowords>words (dark blue) contrasts. The semantic processing cluster is shown in green. B (Left panel): A number-processing network, primarily involving a region of the parietal lobe. B (Middle panel): An arithmetic-processing network, primarily involving regions of the frontal and parietal lobes. B (Right panel): Children (red) and adult (pink) meta-analyses of brain areas associated with numbers and calculations. Figure by Janet Croog.

A schematic representation of the genetic regions and gene-candidates linked to or associated with SRD and reading-related processes (shown in blue), and SMD and mathematics-related processes (shown in red). Dark blue signifies more studied loci and genes. Blue highlighted in red indicate the genes implicated in both SRD and SMD. Figure by Janet Croog.

The DSM-5 and IDEA 2004 reflect agreement that SLD can occur in word reading and spelling (Specific Word Reading Disability; SWRD) and in specific reading comprehension disability (SRCD). SWRD represents difficulties with beginning reading skills due at least in part to phonological processing deficits, while other language indicators (e.g., vocabulary) may be preserved ( Pennington, 2009 ). In contrast, SRCD ( Cutting et al., 2013 ), which is more apparent later in development, is associated with non-phonological language weaknesses ( Scarborough, 2005 ). The magnitude of SRCD is greater than that of vocabulary or language comprehension difficulties, suggesting that other problems, such as weaknesses in executive function or background knowledge, also contribute to SRCD ( Spencer, Wagner, & Petscher, 2018 ).

Math SLDs are differentiated as calculations (SMD) versus problem solving (word problems) SLD, which are associated with distinct cognitive deficits ( L. S. Fuchs et al., 2010 ) and require different forms of intervention ( L. S. Fuchs et al., 2014 ). Calculation is more linked to attention and phonological processing, while problem solving is more linked to language comprehension and reasoning; working memory has been associated with both. Specific written expression disability, SWED ( Berninger, 2004 ; Graham, Collins, & Rigby-Wills, 2017 ) occurs in the mechanical act of writing (i.e., handwriting, keyboarding, spelling), associated with fine motor-perceptual skills, or in composing text (i.e., planning and revising, understanding genre), associated with oral language skills, executive functions, and the automaticity of transcription skills. Although each domain varies in its cognitive correlates, treatment, and neurobiology, there is overlap. By carefully specifying the domain of academic impairment, considerable progress has been made in the treatment and understanding of the factors that lead to SLD.

Identification methods have searched for other markers of unexpected underachievement beyond low achievement, but always include exclusionary factors. Diagnosis solely by exclusion has been criticized due to the heterogeneity of the resultant groups ( Rutter, 1982 ); thus, the introduction of a discrepancy paradigm. One approach relies on the aptitude-achievement discrepancy, commonly operationalized as a discrepancy between measures of IQ and achievement in a specific academic domain. IQ-discrepancy was the central feature of federal regulations for identification from 1977 until 2004, although the approaches used to qualify and quantify the discrepancy varied in the 50 states. Lack of validity evidence ( Stuebing et al., 2015 ; Stuebing et al., 2002 ) resulted in its de-emphasis in IDEA 2004 and elimination from DSM-5.

A second approach focuses on identifying uneven patterns of strengths and weaknesses (PSW) profiles of cognitive functioning to explain observed unevenness in achievement across academic domains ( Flanagan, Alfonso, & Mascolo, 2011 ; Hale et al., 2008 ; Naglieri & Das, 1997 ). According to these methods, a student with SLD demonstrates a weakness in achievement (e.g., word reading), which correlates with an uneven profile of cognitive weaknesses and strengths (e.g., phonological processing deficits with advanced visual-spatial skills). Proponents suggest that understanding these patterns is informative for individualizing interventions that capitalize on student strengths (i.e., maintain and enhance academic motivation) and compensate for weaknesses (i.e., enhance the phonological processing needed for the acquisition and automatization of reading), but little supporting empirical evidence is available ( Miciak, Fletcher, Stuebing, Vaughn, & Tolar, 2014 ; Taylor, Miciak, Fletcher, & Francis, 2017 ). Meta-analytic research suggests an absence of cognitive aptitude by treatment interactions ( Burns et al., 2016 ), and limited improvement in academic skills based on training cognitive deficits such as working memory ( Melby-Lervåg, Redick, & Hulme, 2016 ).

Newer methods of SLD identification are linked to the development of the third historical strand, based on RTI. With RTI, schools screen for early indicators of academic and behavior problems and then progress monitor potentially at-risk children using brief, frequent probes of academic performance. When data indicate inadequate progress in response to adequate classroom instruction (Tier 1), the school delivers supplemental intervention (Tier 2), usually in the form of small-group instruction.

A child who continues to struggle requires more intensive, individualized intervention (Tier 3), which may include special education. An advantage of RTI is that intervention is provided prior to the determination of eligibility for special education placement. RTI juxtaposes the core concept of underachievement with the concept of inadequate response to instruction, that is, intractability to intervention. It prioritizes the presence of functional difficulty and only then considers SLD as a possible source of this difficulty ( Grigorenko, 2009 ). Still, concerns about the RTI approach to identification remain. One concern is that RTI approaches may not identify “high-potential” children who struggle to develop appropriate academic skills ( Reynolds & Shaywitz, 2009 ). Other concerns involve low agreement across different methods for defining inadequate RTI ( D. Fuchs, Compton, Fuchs, Bryant, & Davis, 2008 ; L. S. Fuchs, 2003 ) and challenges schools face in adequately implementing RTI frameworks ( Balu et al., 2015 ; D. Fuchs & Fuchs, 2017 ; Schatschneider, Wagner, Hart, & Tighe, 2016 ).

Prevalence and Incidence

Because the attributes of SLD are dimensional and depend on the thresholds used to subdivide normal distributions ( Hulme & Snowling, 2013 ), estimates of prevalence and incidence vary. SWRD’s prevalence estimates range from 5 to 17% ( Katusic, Colligan, Barbaresi, Schaid, & Jacobsen, 2001 ; Moll, Kunze, Neuhoff, Bruder, & Schulte-Körne, 2014 ). SRCD is less frequent ( Etmanskie, Partanen, & Siegel, 2016 ), but still represents about 42% of all children ever identified with SLD in reading at any grade ( Catts, Compton, Tomblin, & Bridges, 2012 ). Estimates of incidence and prevalence of SMD vary as well: from 4 to 8% ( Moll et al., 2014 ). Cumulative incidence rates by the age of 19 years range from 5.9% to 13.8%. Similar to SWRD, SMD can be differentiated in terms of lower- and higher-order skills and by time of onset. Computation-based SMD manifests earlier; problem-solving SMD later, sometimes in the absence of computation-based SMD ( L. S. Fuchs, D. Fuchs, C. L. Hamlett, et al., 2008 ). SWED is the least studied SLD. Its prevalence estimates range from 6% to 22% ( P. L. Morgan, Farkas, Hillemeier, & Maczuga, 2016 ) and cumulative incidence ranges from 6.9% to 14.7% ( Katusic, Colligan, Weaver, & Barbaresi, 2009 ).

Comorbidity and Co-Occurrence

One reason SLD can be difficult to define and identify is that different SLDs often co-occur in the same child. Comorbidity involving SWRD ranges from 30% ( National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2014 ) to 60% ( Willcutt et al., 2007 ). The most frequently observed co-occurrences are between (1) SWRD and SMD ( Moll et al., 2014 ; Willcutt et al., 2013 ), with 30–50% of children who experience a deficit in one academic domain demonstrating a deficit in the other ( Moll et al., 2014 ); (2) SWRD and early language impairments ( Dickinson, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, 2010 ; Hulme & Snowling, 2013 ; Pennington, 2009 ) with 55% of individuals with SWRD exhibiting significant speech and language impairment ( McArthur, Hogben, Edwards, Heath, & Mengler, 2000 ); and (3) SWRD and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, with 25–50% of children with SWRD meeting criteria for ADHD ( Pennington, 2009 ) and for generalized anxiety disorder and specific test anxiety, depression, and conduct problems ( Cederlof, Maughan, Larsson, D’Onofrio, & Plomin, 2017 ), although comorbid conduct problems are largely restricted to the subset of individuals with both SWRD and ADHD ( Willcutt et al., 2007 ).

The co-occurrence of SMD is less studied, but there are some consistently replicated observations: (1) individuals with SMD exhibit higher rates of ADHD, and math difficulties are observed in individuals with ADHD more frequently than in the general population ( Willcutt et al., 2013 ); (2) math difficulties are associated with elevated anxiety and depression even after reading difficulties are controlled ( Willcutt et al., 2013 ); and (3) SMD are associated with other developmental conditions such as epilepsy ( Fastenau, Shen, Dunn, & Austin, 2008 ) and schizophrenia ( Crow, Done, & Sacker, 1995 ).

SLD is clearly associated with difficulties in adaptation, in school and in larger spheres of life associated with work and overall adjustment. Longitudinal research reports poorer vocational outcomes, lower graduation rates, higher rates of psychiatric difficulties, and more involvement with the justice system for individuals with SWRD ( Willcutt et al., 2007 ). Importantly, there is evidence of increased comorbidity across forms of SLD with age, with accumulated cognitive burden ( Costa, Edwards, & Hooper, 2016 ). Individuals with comorbid SLDs have poorer emotional adjustment and school functioning than those identified with a single impairment ( Martinez & Semrud-Clikeman, 2004 ).

Identification (Diagnosis)

Comorbidity indicates that approaches to assessment should be broad and comprehensive. For SLD, the choice of a classification model directly influences the selection of assessments for diagnostic purposes. Although all three models are used, the literature (Fletcher et al., 2019) demonstrates that a single indicator model, based either on cut-off scores, other formulae, or assessment of instructional response, does not lead to reliable identification regardless of the method employed. SLD can be identified reliably only in the context of multiple indicators. A step in this direction is a hybrid method that includes three sets of criteria, two inclusionary and one exclusionary, recommended by a consensus group of researchers (Bradley, Danielson, & Hallahan, 2002). The two inclusionary criteria are evidence of low achievement (captured by standardized tests of academic achievement) and evidence of inadequate RTI (captured by curriculum-based progress-monitoring measures or other education records). The exclusionary criterion should demonstrate that the documented low achievement is not primarily attributable to “other” (than SLD) putative causes such as (a) other disorders (e.g., intellectual disability, sensory or motor disorders) or (b) contextual factors (e.g., disadvantaged social, religious, economic, linguistic, or family environment). In the future, it is likely that multi-indicator methods will be extended, with improved identification accuracy, by the addition of other indicators, neurobiological, genetic, or behavioral. It is also possible that assessment of specific cognitive processes beyond academic achievement will improve identification, but presently there is little evidence that such testing adds value to identification ( Elliott & Grigorenko, 2014 ; Fletcher et al., 2019). All identification methods for SLD assume that children referred for assessment are in good health or are being treated and that their physical health, including hearing and vision, is monitored. Currently, there are no laboratory tests (i.e., DNA or brain structure/activity) for SLD. There are also no tests that can be administered by an optometrist, audiologist, or physical therapist to diagnose or treat SLD.

Etiological Factors

Neural structure and function.

Since the earliest reports of reading difficulties, it has been assumed that the loss of function (i.e., acquired reading disability) or challenges in the acquisition of function (i.e., congenital reading disability) are associated with the brain. Functional patterns of activation in response to cognitive stimuli show reliable differences in degrees of activation between typically developing children and those identified with SWRD, and reveal different spatial distributions in relation to children identified with SMD and ADHD ( Dehaene, 2009 ; Seidenberg, 2017 ). In SWRD, there are reduced gray matter volumes, reduced integrity of white matter pathways, and atypical sulcal patterns/curvatures in the left-hemispheric frontal, occipito-temporal, and temporo-parietal regions that overlap with areas of reduced brain activation during reading.

These findings together indicate the presence of atypicalities in the structures (i.e., grey matter) that form the neural system for reading and their connecting pathways (i.e., white matter). These structural atypicalities challenge the emergence of the cognitive—phonological, orthographic, and semantic—representations required for the assembly and automatization of the reading system. Although some have interpreted the atypicalities as a product of reading instruction ( Krafnick, Flowers, Luetje, Napoliello, & Eden, 2014 ), there is also evidence that atypicalities can be observed in pre-reading children at risk for SWRD due to family history or speech and language difficulties ( Raschle et al., 2015 ), sometimes as early as a few days after birth with electrophysiological measures ( Molfese, 2000 ). What emerges in a beginning reader, if not properly instructed at developmentally important periods, is a suboptimal brain system that is inefficient in acquiring and practicing reading. This system is complex, representing multiple networks aligned with different reading-related processes ( Figure 3 ). The system engages cooperative and competitive brain mechanisms at the sublexical (phonological) and lexical levels, in which the phonological, orthographic, and semantic representations are utilized to rapidly form representations of a written stimulus. Proficient readers process words on sight with immediate access to meaning ( Dehaene, 2009 ). In addition to malleability in development, there is strong evidence of malleability through instruction in SWRD, such that the neural processes largely normalize if the intervention is successful ( Barquero, Davis, & Cutting, 2014 ).

The functional neural networks for SMD also vary depending on the mathematical operation being performed, just as the neural correlates of SWRD and SRCD do ( Cutting et al., 2013 ). Neuroimaging studies on the a(typical) acquisition of numeracy posit SMD ( Arsalidou, Pawliw-Levac, Sadeghi, & Pascual-Leone, 2017 ) as a brain disorder engaging multiple functional systems that together substantiate numeracy and its componential processes ( Figure 3 ). First, the intraparietal sulcus, the posterior parietal cortex, and regions in the prefrontal cortex are important for representing and processing quantitative information. Second, mnemonic regions anchored in the medial temporal lobe and hippocampus are involved in the retrieval of math facts. Third, additional relevant regions include visual areas implicated in visual form judgement and symbolic processing. Fourth, prefrontal areas are involved in higher-level processes such as error monitoring, and maintaining and manipulating information. As mathematical processes become more automatic, reliance on the parietal network decreases and reliance on the frontal network increases. All these networks, assembled in a complex functional brain system, appear necessary for the acquisition and maintenance of numeracy, and various aberrations in the functional interactions between networks have been described. Thus, SMD can arise as a result of disturbances in one or multiple relevant networks, or interactions among them ( Arsalidou et al., 2017 ; Ashkenazi, Black, Abrams, Hoeft, & Menon, 2013 ). There is also evidence of malleability and the normalization of neural networks with successful intervention in SMD ( Iuculano et al., 2015 ).

Genetic and environmental factors

Early case studies of reading difficulties identified their familial nature, which has been confirmed in numerous studies utilizing genetically-sensitive designs with various combinations of relatives—identical and fraternal twins, non-twin siblings, parent-offspring pairs and trios, and nuclear and extended families. The relative risk of having SWRD if at least one family member has SWRD is higher for relatives of individuals with the condition, compared to the risk to unrelated individuals; higher for children in families where at least one relative has SWRD; even higher for families where a first-degree relative (i.e., a parent or a sibling) has SWRD; and higher still for children in families where both parents have SWRD ( Snowling & Melby-Lervåg, 2016 ). Quantitative-genetic studies estimate that 30–80% of the variance in reading, math or spelling outcomes is explained by heritable factors ( Willcutt et al., 2010 ).

Since the 1980s, there have been systematic efforts to identify the sources of structural variation in the genome, i.e., genetic susceptibility loci that can account for the strong heritability and familiality of SWRD ( Figure 4 ). These efforts have yielded the identification of nine regions of the genome thought to harbor genes, or other genetic material, whose variation is associated with the presence of SWRD and individual differences in reading-related processes. Within these regions, a number of candidate genes have been tapped, but no single candidate has been unequivocally replicated as a causal gene for SWRD, and observed effects are small. In addition, multiple other genes located outside of the nine linked regions have been observed to be relevant to the manifestation of SWRD and related difficulties. Currently there are ongoing efforts to interrogate candidate genes for SWRD and connect their structural variation to individual differences in the brain system underlying the acquisition and practice of reading.

There are only a few molecular-genetic studies of SMD and its related processes ( Figure 4 ). Unlike SWRD, no “regions of interest” have been identified. Only one study investigated the associations between known single-nuclear polymorphisms (SNP) and a composite measure of mathematics performance derived from various assessments of SMD-related componential processes and teacher ratings. The study generated a set of SNPs that, when combined, accounted for 2.9% of the phenotypic variance ( Figure 4 shows the genes in which the three most statistically significant SNPs from this set are located). Importantly, when this SNP set was used to study whether the association between the 10-SNP set and mathematical ability differs as a function of characteristics of the home and school, the association was stronger for indicators of mathematical performance in chaotic homes and in the context of negative parenting.

Finally, studies have investigated the pleiotropic (i.e., impacting multiple phenotypes) effects of SWRD candidate genes on SMD, ADHD, and related processes. These effects are seemingly in line with the “generalist genes” hypothesis, asserting the pleiotropic influences of some genes to multiple SLD ( Plomin & Kovas, 2005 ).

Environmental factors are strong predictors of SLD. These factors penetrate all levels of a child’s ecosystem: culture, demonstrated in different literacy and numeracy rates around the world; social strata, captured by social-economic indicators across different cultures; characteristics of schooling, reflected by pedagogies and instructional practices; family literacy environments through the availability of printed materials and the importance ascribed to reading at home; and neighborhood and peer influences. Interactive effects suggest that reading difficulties are magnified when certain genetic and environmental factors co-occur, but there is evidence of neural malleability even in SWDE ( Overvelde & Hulstijn, 2011 ). Neural and genetic factors are best understood as risk factors that variably manifest depending on the home and school environment and child attributes like motivation.

Intervention

Although the content of instruction varies depending on whether reading, math, and/or writing are impaired, general principles of effective intervention apply across SLD i . First, intervention for SLD is explicit ( Seidenberg, 2017 ): Teachers formally present new knowledge and concepts with clear explanations, model skills and strategies, and teach to mastery with cumulative practice with ongoing guidance and feedback. Second, intervention is individualized: Instruction is formatively adjusted in response to systematic progress-monitoring data ( Stecker, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 2005 ). Third, intervention is comprehensive and differentiated, addressing the multiple components underlying proficient skill as well as comorbidity. Comprehensive approaches address the multifaceted nature of SLD and provide more complex interventions that are generally more effective than isolated skills training in reading ( Mathes et al., 2005 ) and math ( L. S. Fuchs et al., 2014 ). For example, children with SLD and ADHD may need educational and pharmacological interventions ( Tamm et al., 2017 ). Anxiety can develop early in children who struggle in school, and internalizing problems must be treated ( Grills, Fletcher, Vaughn, Denton, & Taylor, 2013 ). Differentiation through individualization in the context of a comprehensive intervention also permits adjustments of the focus of an intervention on specific weaknesses.

Fourth, intervention adjusts intensity as needed to ensure success, by increasing instructional time, decreasing group size, and increasing individualization ( L. S. Fuchs, Fuchs, & Malone, 2017 ). Such specialized intervention is typically necessary for students with SLD ( L. S. Fuchs et al., 2015 ). Yet, effective instruction for SLD begins with differentiated general education classroom instruction ( Connor & Morrison, 2016 ), in which intervention is coordinated with rather than supplanting core instruction ( L. S. Fuchs, D. Fuchs, C. Craddock, et al., 2008 ).

In addition, intervention is more effective when provided early in development. For example, intervention for SWRD was twice as effective if delivered in grades 1 or 2 than if started in grade 3 ( Lovett et al., 2017 ). This is underscored by neuroimaging research ( Barquero et al., 2014 ) showing that experience with words and numbers is needed to develop the neural systems that mediate reading and math proficiency. A child with or at risk for SWRD who cannot access print because of a phonological processing problem will not get the reading experience needed to develop the lexical system for whole word processing and immediate access to word meanings. This may be why remedial programs are less effective after second grade; with early intervention, the child at risk for SLD develops automaticity because they have gained the experience with print or numbers essential for fluency. Even with high quality intensive intervention, some children with SLD do not respond adequately, and students with persistent SLD may profit from assistive technology (e.g., computer programs that convert text-to-speech; Wood, Moxley, Tighe, & Wagner, 2018 ).

Finally, interventions for SLD must occur in the context of the academic skill itself. Cognitive interventions that do not involve print or numbers, such as isolated phonological awareness training or working memory training without application to mathematical operations do not improve reading or math skill ( Melby-Lervåg et al., 2016 ). Physical exercises (e.g., cerebellar training), optometric training, special lenses or overlays, and other proposed interventions that do not involve teaching reading or math are ineffective ( Pennington, 2009 ). Pharmacological interventions are effective largely due to their impact on comorbid symptoms, with little evidence of a direct effect on the academic skill ( Tamm et al., 2017 ).

No evaluations of recovery rate from SLD have been performed. Intervention success has been evaluated as closing the age-grade discrepancy, placing children with SLD at an age-appropriate grade level, and maintaining their progress at a rate commensurate with typical development. Meta-analytic studies estimate effect sizes of academic interventions at 0.49 for reading ( Scammacca, Roberts, Vaughn, & Stuebing, 2015 ), 0.53 for math ( Dennis et al., 2016 ), and 0.74 for writing ( Gillespie & Graham, 2014 ).

Implications for Practice and Research

Practitioners should recognize that the psychological and educational scientific evidence base supports specific approaches to the identification and treatment of SLD. In designing SLD evaluations, assessments must be timely to avoid delays in intervention; they must consider comorbidities as well as contextual factors, and data collected in the context of previous efforts to instruct the child. Practitioners should use the resulting assessment data to ensure that intervention programs are evidence-based and reflect explicitness, comprehensiveness, individualization, and intensity. There is little evidence that children with SLD benefit from discovery, exposure, or constructivist instructional approaches.

With respect to research, the most pressing issue is understanding individual differences in development and intervention from neurological, genetic, cognitive, and environmental perspectives. This research will ultimately lead to earlier and more precise identification of children with SLD, and to better interventions and long-term accommodations for the 2–6% of the general population who receive but do not respond to early prevention efforts. More generally, other human conditions may benefit from the examples of progress exemplified by the integrated, interdisciplinary approaches that underlie the progress of the past 50 years in the scientific understanding of SLD.

Acknowledgments

The authors are the Principal Investigators of the currently funded Learning Disabilities Research Centers ( https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/ldrc ) and Innovation Hubs ( https://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/ldhubs ), the two key NICHD programs supporting research on Specific Learning Disabilities. The preparation of this articles was supported by P20 HD090103 (PI: Compton), P50 HD052117 (PI: Fletcher), P20 HD075443 (PI: Fuchs), P20 HD091005 (PI: Grigorenko), P50 HD052120 (PI: Wagner), and P50 HD27802 (PI: Willcutt). Grantees undertaking such projects are encouraged to express their professional judgment. Therefore, this article does not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the abovementioned agencies, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

i For examples of effective evidence-based interventions see www.evidenceforessa.org , intensiveintervention.org , What Works Clearinghouse, www.meadowscenter.org , www.FCRR.org/literacyroadmap , www.understood.org/en/about/our.../national-center-for-learning-disabilities , https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/infographics/pdf/REL_SE_Implementing_evidencebased_literacy_practices_roadmap.pdf , among others.

- *Arsalidou M, Pawliw-Levac M, Sadeghi M, & Pascual-Leone J (2017). Brain areas associated with numbers and calculations in children: Meta-analyses of fMRI studies . Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience . doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.08.002 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ashkenazi S, Black JM, Abrams DA, Hoeft F, & Menon V (2013). Neurobiological underpinnings of math and reading learning disabilities . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 46 , 549–569. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balu R, Zhu P, Doolittle F, Schiller E, Jenkins J, & Gersten R (2015). Evaluation of response to intervention practices for elementary school reading . Washington, DC: National Center for Educational Evaluation and Regional Assistance. [ Google Scholar ]

- *Barquero LA, Davis N, & Cutting LE (2014). Neuroimaging of reading intervention: a systematic review and activation likelihood estimate meta-analysis . PLoS ONE , 9 , e83668. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berninger VW (2004). Understanding the graphia in developmental dysgraphia: A developmental neuropsychological perspective for disorders in producing written language In Dewey D & Tupper D (Eds.), Developmental motor disorders: A neuropsychological perspective (pp. 189–233). Guilford Press: New York, NY. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berninger VW, & Abbott RD (2010). Listening comprehension, oral expression, reading comprehension, and written expression: Related yet unique language systems in grades 1, 3, 5, and 7 . Journal of Educational Psychology , 102 , 635–651. doi: 10.1037/a0019319 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Burns MK, Petersen-Brown S, Haegele K, Rodriguez M, Schmitt B, Cooper M, . . . VanDerHeyden AM (2016). Meta-analysis of academic interventions derived from neuropsychological data . School Psychology Quarterly , 31 , 28–42. doi: 10.1037/spq0000117 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Catts HW, Compton D, Tomblin B, & Bridges MS (2012). Prevalence and nature of late-emerging poor readers . Journal of Educational Psychology , 10 , 166–181. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cederlof M, Maughan B, Larsson H, D’Onofrio BM, & Plomin R (2017). Reading problems and major mental disorders - co-occurrences and familial overlaps in a Swedish nationwide cohort . Journal of Psychiatric Research , 91 , 124–129. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clements SD (1966). Minimal brain dysfunction in children . Washington, DC: U.S: Department of Health, Education and Welfare. [ Google Scholar ]

- Connor CM, & Morrison FJ (2016). Individualizing student instruction in reading: Implications for policy and practice . Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences , 3 , 54–61. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Costa L-JC, Edwards CN, & Hooper SR (2016). Writing disabilities and reading disabilities in elementary school students: rates of co-occurrence and cognitive burden . Learning Disability Quarterly , 39 , 17–30. doi: 10.1177/0731948714565461 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crow TJ, Done DJ, & Sacker A (1995). Childhood precursors of psychosis as clues to its evolutionary origins . European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience , 245 , 61–69. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cutting LE, Clements-Stephens A, Pugh KR, Burns S, Cao A, Pekar JJ, . . . Rimrodt SL (2013). Not all reading disabilities are dyslexia: Distinct neurobiology of specific comprehension deficits . Brain Connectivity , 3 , 199–211. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0116 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ***Dehaene S (2009). Reading in the brain . New York, NY: Viking. [ Google Scholar ]

- *Dennis MS, Sharp E, Chovanes J, Thomas A, Burns RM, Custer B, & Park J (2016). A meta-analysis of empirical research on teaching students with mathematics learning difficulties . Learning Disabilities Research & Practice , 31 , 156–168. [ Google Scholar ]

- **Dickinson DK, Golinkoff RM, & Hirsh-Pasek K (2010). Speaking out for language: Why language is central to reading development . Educational Researcher , 39 , 305–310. [ Google Scholar ]

- ***Elliott JG, & Grigorenko EL (2014). The dyslexia debate . New York, NY: Cambridge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis AW (1984). The cognitive neuropsychology of developmental (and acquired) dyslexia: A critical survey . Cognitive Neuropsychology , 2 , 169–205. [ Google Scholar ]

- Etmanskie JM, Partanen M, & Siegel LS (2016). A longitudinal examination of the persistence of late emerging reading disabilities . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 49 , 21–35. doi: 10.1177/0022219414522706 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fastenau PS, Shen J, Dunn DW, & Austin JK (2008). Academic underachievement among children with epilepsy: proportion exceeding psychometric criteria for learning disability and associated risk factors . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 41 , 195–207. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flanagan DP, Alfonso VC, & Mascolo JT (2011). A CHC-based operational definition of SLD: Integrating multiple data sources and multiple data-gathering methods In Flanagan DP & Alfonso VC (Eds.), Essentials of specific learning disability identification (pp. 233–298). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- ***Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, & Barnes MA (2018). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs D, Compton DL, Fuchs LS, Bryant J, & Davis GN (2008). Making “secondary intervention” work in a three-tier responsiveness-to-intervention model: findings from the first-grade longitudinal reading study of the National Research Center on Learning Disabilities . Reading and Writing , 21 , 413–436. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs D, & Fuchs LS (2017). Critique of the National Evaluation of Responsiveness-To-Intervention: A case for simpler frameworks . Exceptional Children , 83 , 255–268. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS (2003). Assessing treatment responsiveness: Conceptual and technical issues . Learning Disabilities Research and Practice , 18 , 172–186. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Compton DL, Wehby J, Schumacher RF, Gersten R, & Jordan NC (2015). Inclusion versus specialized intervention for very low-performing students: What does access mean in an era of academic challenge? Exceptional Children , 81 , 134–157. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Craddock C, Hollenbeck KN, Hamlett CL, & Schatschneider C (2008). Effects of small-group tutoring with and without validated classroom instruction on at-risk students’ math problem-solving: Are two tiers of prevention better than one? Journal of Educational Psychology , 100 , 491–509. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Hamlett CL, Lambert W, Stuebing K, & Fletcher JM (2008). Problem-solving and computational skill: Are they shared or distinct aspects of mathematical cognition? Journal of Educational Psychology , 100 , 30–47. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, & Malone A (2017). The taxonomy of intervention intensity . Teaching Exceptional Children , 50 , 35–43. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS, Geary DC, Compton DL, Fuchs D, Hamlett CL, Seethaler PM, . . . Schatschneider C (2010). Do different types of school mathematics development depend on different constellations of numerical and general cognitive abilities? Developmental Psychology , 46 , 1731–1746. doi: 10.1037/a0020662 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fuchs LS, Powell SR, Cirino PT, Schumacher RF, Marrin S, Hamlett CL, . . . Changas PC (2014). Does calculation or word-problem instruction provide a stronger route to pre-algebraic knowledge? Journal of Educational Psychology , 106 , 990–1006. doi: 10.1037/a0036793 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Gillespie A, & Graham S (2014). A meta-analysis of writing interventions for students with learning disabilities . Exceptional Children , 80 , 454–473. doi: 10.1177/0014402914527238 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Graham S, Collins AA, & Rigby-Wills H (2017). Writing characteristics of students with learning disabilities and typically achieving peers: A meta-analysis . Exceptional Children , 83 , 199–218. [ Google Scholar ]

- **Grigorenko EL (2009). Dynamic assessment and response to intervention: Two sides of one coin . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 42 , 111–132. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grills AE, Fletcher JM, Vaughn SR, Denton CA, & Taylor P (2013). Anxiety and inattention as predictors of achievement in early elementary school children . Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal , 26 , 391–410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hale JB, Fiorello CA, Miller JA, Wenrich K, Teodori AM, & Henzel J (2008). WISC-IV assessment and intervention strategies for children with specific learning difficulties In Prifitera A, Saklofske DH, & Weiss LG (Eds.), WISC-IV clinical assessment and intervention (pp. 109–171). New York, NY: Elsevier. [ Google Scholar ]

- ***Hulme C, & Snowling MJ (2013). Developmental disorders of language learning and cognition . Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Google Scholar ]

- Iuculano T, Rosenberg-Lee M, Richardson JG, Tenison C, Fuchs LS, Supekar K, & Menon V (2015). Cognitive tutoring induces widespread neuroplasticity and remediates brain function in children with mathematical learning disabilities . Nature Communications , 6 , 8453. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9453 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Barbaresi WJ, Schaid DJ, & Jacobsen SJ (2001). Incidence of reading disability in a population-based birth cohort, 1976–1982, Rochester, Minnesota . Mayo Clinic Proceedings , 76 , 1081–1092. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, & Barbaresi WJ (2009). The forgotten learning disability: Epidemiology of written-language disorder in a population-based birth cohort (1976–1982), Rochester, Minnesota . Pediatrics , 123 , 1306–1313. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2098 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Klassen RM, Tze VMC, & Hannok W (2013). Internalizing problems of adults with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 46 , 317–327. doi: 10.1177/0022219411422260 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krafnick AJ, Flowers DL, Luetje MM, Napoliello EM, & Eden GF (2014). An investigation into the origin of anatomical differences in dyslexia . The Journal of Neuroscience , 34 , 901–908. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2092-13.2013 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lovett MW, Frijters JC, Wolf MA, Steinbach KA, Sevcik RA, & Morris RD (2017). Early intervention for children at risk for reading disabilities: The impact of grade at intervention and individual differences on intervention outcomes . Journal of Educational Psychology , 109 , 889–914. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Martinez RS, & Semrud-Clikeman M (2004). Emotional adjustment and school functioning of young adolescents with multiple versus single learning disabilities . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 37 , 411–420. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mathes PG, Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ, & Schatschneider C (2005). An evaluation of two reading interventions derived from diverse models . Reading Research Quarterly , 40 , 148–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- McArthur GM, Hogben JH, Edwards VT, Heath SM, & Mengler ED (2000). On the “specifics” of specific reading disability and specific language impairment . Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 41 , 869–874. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Melby-Lervåg M, Lyster S, & Hulme C (2012). Phonological skills and their role in learning to read: A meta-analytic review . Psychological Bulletin , 138 , 322–352. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Melby-Lervåg M, Redick TS, & Hulme C (2016). Working memory training does not improve performance on measures of intelligence or other measures of “far transfer” evidence from a meta-analytic review . Perspectives on Psychological Science , 11 , 512–534. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miciak J, Fletcher JM, Stuebing KK, Vaughn S, & Tolar TD (2014). Patterns of cognitive strengths and weaknesses: Identification rates, agreement, and validity for learning disabilities identification . School Psychology Quarterly , 29 , 21–37. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Molfese DL (2000). Predicting dyslexia at 8 years of age using neonatal brain responses . Brain and Language , 72 , 238–245. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moll K, Kunze S, Neuhoff N, Bruder J, & Schulte-Körne G (2014). Specific learning disorder: Prevalence and gender differences . PLoS ONE , 9 , e103537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103537 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan PL, Farkas G, Hillemeier MM, & Maczuga S (2016). Who is at risk for persistent mathematics difficulties in the U.S? Journal of Learning Disabilities , 49 , 305–319. doi: 10.1177/0022219414553849 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan WP (1896). A case of congenital word-blindness (inability to learn to read) . British Medical Journal , 2 , 1543–1544. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morris RD, Stuebing K, Fletcher J, Shaywitz S, Lyon R, Shankweiler D, . . . Shaywitz B (1998). Subtypes of reading disability: A phonological core . Journal of Educational Psychology , 90 , 347–373. [ Google Scholar ]

- Naglieri JA, & Das JP (1997). Intelligence revised In Dillon RF (Ed.), Handbook on testing (pp. 136–163). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Center for Learning Disabilities. (2014). The state of learning disabilties: facts, trends and emerging issues . Retrieved from New York, NY: [ Google Scholar ]

- Overvelde A, & Hulstijn W (2011). Handwriting development in grade 2 and grade 3 primary school children with normal, at risk, or dysgraphic characteristics . Research in Developmental Disabilities , 32 , 540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.027 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Peng P, & Fuchs D (2016). A meta-analysis of working memory deficits in children with learning difficulties: Is there a difference between verbal domain and numerical domain? Journal of Learning Disabilities , 49 , 3–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ***Pennington BF (2009). Diagnosing learning disorders: A neuropsychological framework (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- **Plomin R, & Kovas Y (2005). Generalist genes and learning disabilities . Psychological Bulletin , 131 , 592–617. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Raschle NM, Becker BLC, Smith S, Fehlbaum LV, Wang Y, & Gaab N (2015). Investigating the influences of language delay and/or familial risk for dyslexia on brain structure in 5-year-olds . Cerebral Cortex , 27 , 764–776. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rayner K, Foorman BR, Perfetti CA, Pesetsky D, & Seidenberg MS (2001). How psychological science inform the teaching of reading . Psychological Science in the Public Interest , 2 , 31–74. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reynolds CR, & Shaywitz SE (2009). Response to intervention: Ready or not? Or, from wait-to-fail to watch-them-fail . School Psychology Quarterly , 24 , 130–145. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rutter M (1982). Syndromes attributed to “minimal brain dysfunction” in childhood . The American journal of psychiatry , 139 , 21–33. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Scammacca NK, Roberts G, Vaughn S, & Stuebing KK (2015). A meta-analysis of interventions for struggling readers in grades 4–12: 1980–2011 . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 48 , 369–390. doi: 10.1177/0022219413504995 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scarborough HS (2005). Developmental relationships between language and reading: Reconciling a beautiful hypothesis with some ugly facts In Catts HW & Kamhi AG (Eds.), The connections between language and reading disabilities (pp. 3–24). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schatschneider C, Wagner RK, Hart SA, & Tighe EL (2016). Using simulations to investigate the longitudinal stability of alternative schemes for classifying and identifying children with reading disabilities . Scientific Studies of Reading , 20 , 34–48. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ***Seidenberg M (2017). Language at the speed of sight: How we read, why so many cannot, and what can be done about it . New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- *Snowling MJ, & Melby-Lervag M (2016). Oral language deficits in familial dyslexia: A meta-analysis and review . Psychological Bulletin , 142 , 498–545. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spencer M, Wagner RK, & Petscher Y (2018). The reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge of children with poor reading comprehension despite adequate decoding: Evidence from a regression-based matching approach . Journal of Educational Psychology . doi: 10.1037/edu0000274 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- **Stecker PM, Fuchs LS, & Fuchs D (2005). Using curriculum-based measurement to improve student achievement: Review of research . Psychology in the Schools , 42 , 795–820. [ Google Scholar ]

- *Stuebing KK, Barth AE, Trahan L, Reddy R, Miciak J, & Fletcher JM (2015). Are child characteristics strong predictors of response to intervention? A meta-analysis . Review of Educational Research , 85 , 395–429. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- *Stuebing KK, Fletcher JM, LeDoux JM, Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, & Shaywitz BA (2002). Validity of IQ-discrepancy classifications of reading disabilities: A meta-analysis . American Educational Research Journal , 39 , 469–518. [ Google Scholar ]

- Szucs D (2016). Subtypes and comorbidity in mathematical learning disabilities: Multidimensional study of verbal and visual memory processes is key to understanding In Cappelletti M & Fias W (Eds.), Prog Brain Res (Vol. 227 , pp. 277–304): Elsevier. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tamm L, Denton CA, Epstein JN, Schatschneider C, Taylor H, Arnold LE, . . . Vaughn A (2017). Comparing treatments for children with ADHD and word reading difficulties: A randomized clinical trial . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 85 , 434–446. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000170 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor WP, Miciak J, Fletcher JM, & Francis DJ (2017). Cognitive discrepancy models for specific learning disabilities identification: Simulations of psychometric limitations . Psychological Assessment , 29 , 446–457. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- United States Office of Education (1968). Special education for handicapped children, first annual report of the National Advisory Committee on Handicapped Children . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health, Education, & Welfare, U.S. Office of Education [ Google Scholar ]

- *Vandermosten M, Hoeft F, & Norton ES (2016). Integrating MRI brain imaging studies of pre-reading children with current theories of developmental dyslexia: A review and quantitative meta-analysis . Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences , 10 , 155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.06.007 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Willcutt EG, Betjemann RS, Pennington BF, Olson RK, DeFries JC, & Wadsworth SJ (2007). Longitudinal study of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: implications for education . Mind, Brain, and Education , 1 , 181–192. [ Google Scholar ]

- **Willcutt EG, Pennington BF, Duncan L, Smith SD, Keenan JM, Wadsworth SJ, . . . Olson RK (2010). Understanding the complex etiologies of developmental disorders: behavioral and molecular genetic approaches . Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics , 31 , 533–544. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Willcutt EG, Petrill SA, Wu S, Boada R, DeFries JC, Olson RK, & Pennington BF (2013). Comorbidity between reading disability and math disability: Concurrent psychopathology, functional impairment, and neuropsychological functioning . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 46 , 500–516. doi: 10.1177/0022219413477476 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- **Wood SG, Moxley JH, Tighe EL, & Wagner RK (2018). Does use of text-to-speech and related read-aloud tools improve reading comprehension for students with reading disabilities? A meta-analysis . Journal of Learning Disabilities , 51 , 73–84. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

People with learning disabilities, creativity and inclusion in research

By Ruth Northway, Professor of Learning Disability Nursing, University of South Wales @NorthwayRuth

This year’s Learning Disability Awareness Week theme 1 was ‘creativity’ and I want to reflect on the need for creativity to promote the inclusion of people with learning disabilities in research. Historically the relationship between people with learning disabilities and research has not always been an easy one and at times they have been vulnerable to exploitation and harm in the name of research. One such example is the (in)famous case of the Willowbrook State School in America where children with learning disabilities were deliberately infected with hepatitis as part of ‘research’ to develop a vaccine 2 . As well as the harm caused by such an intervention, concerns were raised as to whether parents who gave ‘consent’ for their children to participate in this experiment actually gave valid consent.

Of course, everyone, including people with learning disabilities, needs to be protected from harm arising from research but additional safeguards may be required due to potential challenges regarding capacity and consent 3 . However, this can mean that all people with learning disabilities risk being labelled as ‘vulnerable’ research participants and hence excluded from participation. This also raises ethical concerns and gives rise to harm.

Not being actively included in research that focuses on your life means your voice and experience are not reflected in that research. It means that the findings and how/ if they are translated into practice may have little or no impact thus bringing into question the value of such research. Not being included in wider research such as (for example) that which focuses on the management of long-term health conditions amongst the wider population, may mean that the challenges you face in managing day-to-day life with that condition are not reflected and the findings may not therefore be generalisable. Unfortunately, both scenarios have all too often been the research experience of people with learning disabilities.

So, as researchers we need to develop ways that we can work in partnership with people with learning disabilities to support their inclusion in both learning disability specific research and in wider research regarding health and well-being whilst also safeguarding against exploitation and other harm 4,5 . This is where the need for creativity comes in.

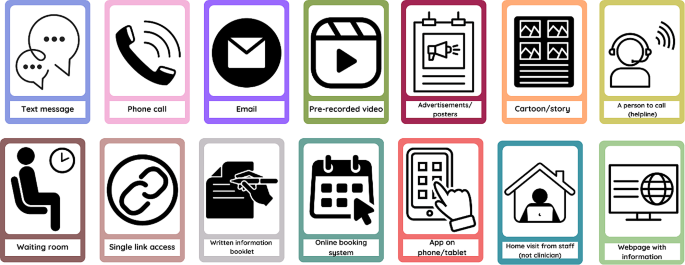

The concept of reasonable adjustments set out in the Equality Act (2010) 6 requires adjustments to be made to the way in which services are delivered to ensure equality of access for disabled people. This concept is, however, transferable across to the research context and should challenge us to adjust the ways in which we conduct research to promote inclusion. This may, for example, mean considering changing approaches to data collection. In a recent project undertaken with colleagues, we used an on-line survey to gain data from health professionals, families and carers 7 . However, we recognised this approach would not facilitate the involvement of people with learning disabilities and therefore adapted our approach. We conducted focus groups with people with learning disabilities and instead of asking participants to rank items on a scale in terms of importance (as we did in the survey), we used a card sorting exercise and discussion to identify those items of most importance to them.

Capacity to consent (a concern for many researchers considering research with people with learning disabilities) can be influenced by how the information is presented to potential participants. A very detailed participant information sheet using complex language and healthcare ‘jargon’ is unlikely to be understood by those with limited literacy skills. However, presenting the information in an easy read format, supported by relevant pictorial images, and taking time to read through the information sheet with participants may support people with learning disabilities to provide valid consent. (For guidance see ‘How to make information accessible’ 8 ).

A further point to consider is that the term ‘learning disabilities’ applies to people with a wide range of strengths, abilities and needs. Those with what are termed ‘mild learning disabilities’ are often not known to specialist learning disability services and therefore all researchers are likely to encounter such participants when recruiting without realising this. In the context of the Equality Act (2010) the duty, to make reasonable adjustments is an anticipatory duty. In other words, services are proactively required to ensure they are in place rather than just reacting to individual requests. Perhaps we should, therefore, be taking a similar approach in the context of research and develop easy read materials as a matter of course – this would also assist many other groups of people who may have challenges in terms of literacy and comprehension.

Many people with learning disabilities want to participate in research and with the right support and adjustments can do so. Working in creative ways in partnership with people with learning disabilities at all stages of the research process can make this happen. I have learnt (and continue to learn) so much from working in partnership with people with learning disabilities about how I can develop as a better researcher. My challenge to you is to do likewise if you are not already doing so.

- Mencap (2021) Learning Disability Week 2021 #LDWeek2021 | Mencap

- Asylum Projects – Willowbrook State School https://www.asylumprojects.org/index.php/Willowbrook_State_School

- https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/mental-capacity-act/

- Frankena, T., Naaldenberg, J., Cardol, M., Garcia-Iriarte, E., Buchner, T., Brooker, K., Embregts, P., Joosa, E., Crowther, F., Fudge Schormans, S., Schippers, A., Walmsley, J., O’Brien, P., Linehan, C., Northway, R., van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Walk, H., Leusink, G. (2019) A consensus statement on how to conduct inclusive health research, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63 (1) 1 – 11

- Northway, R., Howarth, J., Evans, L. (2014) Participatory research, people with intellectual disabilities and ethical approval: making reasonable adjustments to enable participation, Journal of Clinical Nursing , 24, 573 – 581

- Equality Act (2010) Equality Act 2010 | Equality and Human Rights Commission (equalityhumanrights.com)

- Improvement CYMRU – Health Profile https://padlet.com/ImprovementCymru/healthprofile

- Change (2016) How to make information accessible – a guide to producing easy read documents https://www.changepeople.org/getmedia/923a6399-c13f-418c-bb29-051413f7e3a3/How-to-make-info-accessible-guide-2016-Final )

Comment and Opinion | Open Debate

The views and opinions expressed on this site are solely those of the original authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of BMJ and should not be used to replace medical advice. Please see our full website terms and conditions .

All BMJ blog posts are posted under a CC-BY-NC licence

BMJ Journals

Skip to main content

- Faculties and schools

- Services for business

- How to find us

- Undergraduate study

- Postgraduate study

- International students

Home > Faculty of Health, Science, Social Care and Education

Learning Disabilities Research Group

About the group.

The Learning Disability Research Group* conducts research related to the health and social care needs of people with learning disabilities (or intellectual disabilities, as it is known outside the UK).

The group, also known as the Yellow Tulip Group, is chaired jointly by faculty members Irene Tuffrey-Wijne (Professor of Intellectual Disability and Palliative Care) and Richard Keagan-Bull (Researcher) who has learning disabilities.

* Outside the UK, learning disabilities is known as intellectual disabilities.

Irene Tuffrey-Wijne [email protected]

Twitter: @TuffreyWijne

Research that matters

We are interested in doing research that matters to people with learning disabilities, related to health and social care needs. We think that research should include people with learning disabilities.

The Learning Disability Research Group shares experiences and ideas about:

- Research we have done

- Research we want to do

- How we can do research together with people with learning disabilities.

The purpose of this group is to share ideas, learn from each other, and support each other in doing inclusive research with people with learning disabilities. We do this during regular lunchtime meetings (usually the fourth Tuesday of the month at 1pm), where we help and encourage everyone to share academic work and ideas in an accessible format, so group members with learning disabilities can join in with the discussions.

Our research interests are wide-ranging, but we have particular expertise in research around dying, death and bereavement; life transitions; and communication.

We believe that research concerned with the lives of people with learning disabilities must be relevant to them and to their families and carers. The group includes highly experienced senior researchers as well as junior researchers and students. Crucially, it also includes researchers and research advisers who have learning disabilities themselves.

Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) is fundamental to the work of this group, and we hold considerable expertise in this area. Along with the Mental Health Research Group, our group is closely aligned with the Centre for Public Engagement, which supports and champions meaningful involvement in research of people with disabilities, mental health problems, patients and carers.

We have collaborative links with local, national and international organisations including service providers, other academic institutions, and professional networks. One example is the close collaboration with the Palliative Care for People With Learning Disabilities (PCPLD) Network, whose popular webinar and podcast series are hosted by our Faculty.

We want to nurture the future generation of researchers, and welcome inquiries and applications from prospective PhD students.

What we offer

The Learning Disability Research Group offers:

- High quality research projects of national and international relevance

- Access to expertise in conducting learning disability research, both at the Faculty and through collaboration with other universities

- Access to expertise in conducting inclusive research with people with learning disabilities

- Sharing of research ideas, questions and experience

- Monthly meetings

- Occasional research webinars

- PhD supervision

- Support for the Learning Disability Nursing course at Kingston University

- Research training for people with learning disabilities

- Professor Irene Tuffrey-Wijne (CHAIR)

- Richard Keagan-Bull (CO-CHAIR)

- Dr Becky Anderson , Research Associate, Centre for Health and Social Care Research

- Richard Keagan, Bull, Research Assistant, HSSCE

- Jonathon Ding, Research Assistant, HSSCE

- Amanda Cresswell, Research Assistant, HSSCE

- Leon Jordan, Research Assistant, HSSCE

- Sarah Gibson, Research Associate, HSSCE

- Andrea Bruun, Research Associate, HSSCE

- Jo Giles, Research Assistant, HSSCE

- Tasha Marsland, Research Assistant, HSSC

- Sarah Helton , PhD student

Mencap London Research Team

- Bernie Conway

- Carla Barrett

Explore the Palliative Care for People with Learning Disabilities webinars , produced in collaboration with the PCPLD Network.

Research students

Sarah helton.

- Project title: How to ‘talk' about death, bereavement and grief with children/young people with intellectual disabilities - with particular reference to those who are non and pre-verbal

- Supervisors: Professors Irene Tuffrey-Wijne and Jayne Price

Anyone with an interest in learning disabilities research is invited to join our meetings.

Please email Irene at [email protected] for more information.

The following are especially welcome and encouraged to join:

- Researchers and research advisors with learning disabilities (and their support workers)

- Kingston University students – including all learning disability nursing students

- Tuesdays, 12.00 – 13.00

Meetings are an informal mixture of presentations, questions and answers (led by the chairs), and discussion.

Meetings will be held on Zoom. Everyone is encouraged to keep their camera on and contribute.

The Victoria and Stuart Project: Co-designing a toolkit of approaches and resources for end-of-life care planning (EOLCP) with people with learning disabilities within social care settings

- Chief investigators: Professor Irene Tuffrey-Wijne and Dr Becky Anderson (Kingston University)

- Lead organisations: Kingston University

- Collaborators: MacIntyre, Dimensions, Open University, Voluntary Organisations Disability Group (VODG), The Mary Stevens Hospice

- Topic: End of life care planning with people with learning disabilities

- Dates: 2022-2024

- Funder: NIHR-RfSC (NIHR202963

- Website: victoriaandstuart.com

- Value of award: £401,993

The Victoria and Stuart Project is about finding the best ways to help people with learning disabilities plan for the end of their life. We want to make sure that people with learning disabilities get the right care and support when they are ill and going to die. We are working with a wide range of people and organisations to try and get this right.