IM 6–12 Math: Grading and Homework Policies and Practices

By Jennifer Willson, Director, 6–12 Professional Learning Design

In my role at IM, working with teachers and administrators, I am asked to help with the challenges of implementing an IM curriculum. One of the most common challenges is: how can we best align these materials to our homework and grading practices? This question is a bit different from “How should we assess student learning?” or “How should we use assessment to inform instruction?”

When we created the curriculum, we chose not to prescribe homework assignments or decide which student work should count as a graded event. This was deliberate—homework policies and grading practices are highly variable, localized, and values-driven shared understandings that evolve over time. For example, the curriculum needed to work for schools where nightly, graded assignments are expected; schools where no work done outside of class is graded; and schools who take a feedback-only approach for any formative work.

IM 6–8 Math was released in 2017, and IM Algebra 1, Geometry, and Algebra 2 in 2019. In that time, I’ve been able to observe some patterns in the ways schools and teachers align the materials to their local practices. So, while we’re still not going to tell you what to do, we’re now in a position to describe some trends and common ways in which schools and districts make use of the materials to meet their local constraints. Over the past four years, I have heard ideas from teachers, administrators, and IM certified facilitators. In December, I invited our IM community to respond to a survey to share grading and homework policies and practices. In this post I am sharing a compilation of results from the 31 teachers who responded to the survey, as well as ideas from conversations with teachers and IMCFs. We hope that you find some ideas here to inform and inspire your classroom.

How do teachers collect student responses?

Most teachers who responded to the survey collect student work for assessments in a digital platform such as LearnZillion, McGraw-Hill, ASSISTments, Edulastic, Desmos, etc. Others have students upload their work (photo, PDF, etc.) to a learning management system such as Canvas or Google classroom. Even fewer ask students to respond digitally to questions in their learning management system.

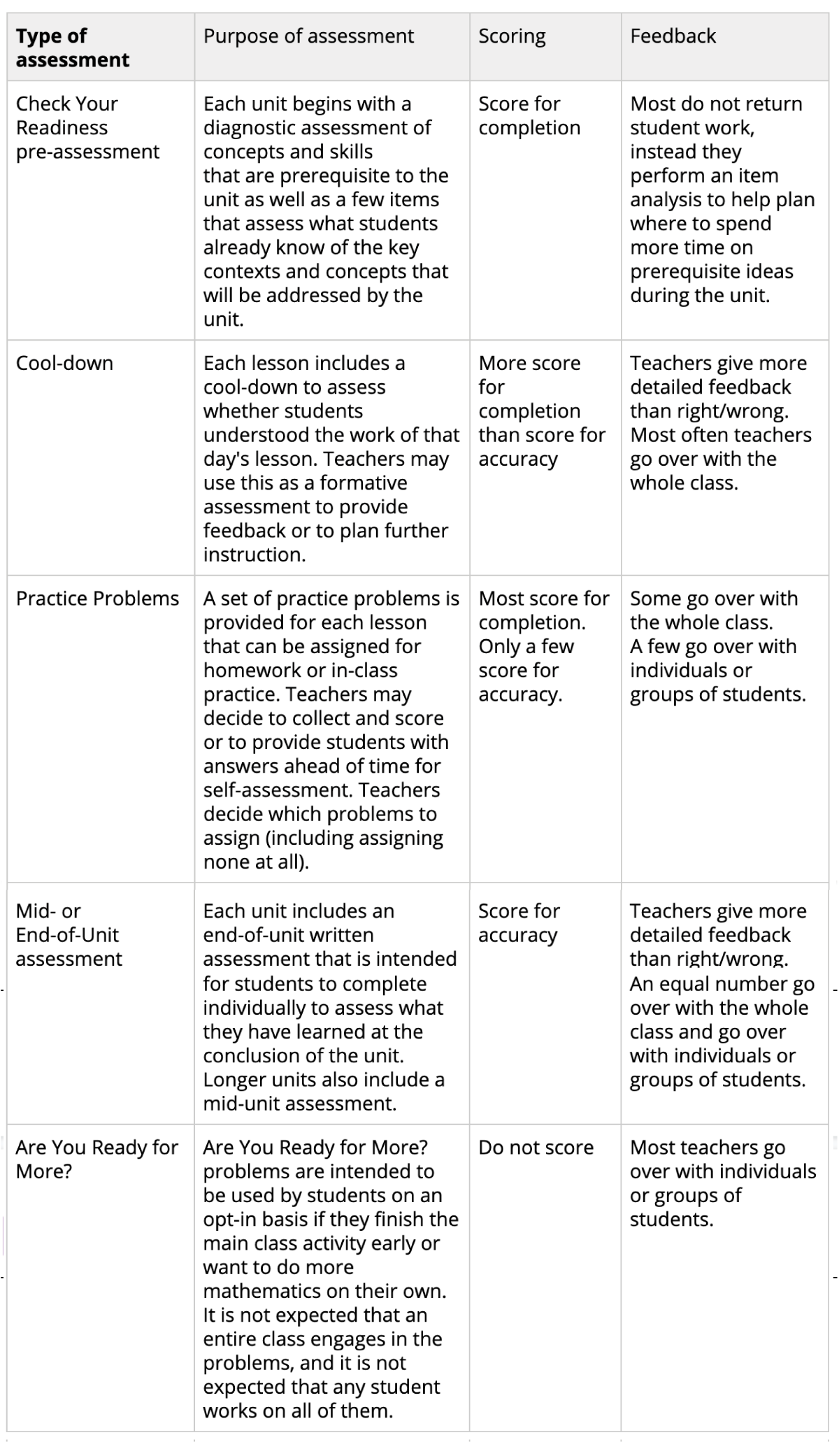

How do teachers tend to score each type of assessment, and how is feedback given?

The table shows a summary of how teachers who responded to the survey most often provide feedback for the types of assessments included in the curriculum.

How are practice problems used?

Every lesson in the curriculum (with a very small number of exceptions) includes a short set of cumulative practice problems. Each set could be used as an assignment done in class after the lesson or worked on outside of class, but teachers make use of these items in a variety of ways to meet their students’ learning needs.

While some teachers use the practice problems that are attached to each lesson as homework, others do not assign work outside of class. Here are some other purposes for which teachers use the practice problems:

- extra practice

- student reflection

- as examples to discuss in class or use for a mini-lesson

- as a warm-up question to begin class

- as group work during class

How do teachers structure time and communication to “go over” practice problems?

It’s common practice to assemble practice problems into assignments that are worked on outside of class meeting time. Figuring out what works best for students to get feedback on practice problems while continuing to move students forward in their learning and work through the next lesson can be challenging.

Here are some ways teachers describe how they approach this need:

- We don’t have time to go over homework every day, but I do build in one class period per section to pause and look at some common errors in cool-downs and invite students to do some revisions where necessary, then I also invite students to look at select practice problems. I collect some practice problems along with cool-downs and use that data to inform what, if anything, I address with the whole class or with a small group.

- Students vote for one practice problem that they thought was challenging, and we spend less than five minutes to get them started. We don’t necessarily work through the whole problem.

- I post solutions to practice problems, sometimes with a video of my solution strategy, so that students can check their work.

- I assign practice problems, post answers, invite students to ask questions (they email me or let me know during the warm-up), and then give section quizzes that are closely aligned to the practice problems, which is teaching my students that asking questions is important.

- I invite students to vote on the most challenging problem and then rather than go over the practice problem I weave it into the current day’s lesson so that students recognize “that’s just like that practice problem!” What I find important is moving students to take responsibility to evaluate their own understanding of the practice problems and not depend on me (the teacher) or someone else to check them. Because my district requires evidence of a quiz and grade each week and I preferred to use my cool-downs formatively, I placed the four most highly requested class practice problems from the previous week on the quiz which I substituted for that day’s cool-down. That saved me quiz design time, there were no surprises for the students, and after about four weeks of consistency with this norm, the students quickly learned that they should not pass up their opportunity to study for the quiz by not only completing the 4–5 practice problems nightly during the week, but again, by reflecting on their own depth of understanding and being ready to give me focused feedback about their greatest struggle on a daily basis.

- I see the practice problems as an opportunity to allow students to go at different paces. It’s more work, but I include extension problems and answers to each practice problem with different strategies and misconceptions underneath. When students are in-person for class, they work independently or in pairs moving to the printed answer keys posted around the room for each problem. They initial under different prompts on the answer key (tried more than one strategy, used a DNL, used a table, made a mistake, used accurate units, used a strategy that’s not on here…) It gives the students and I more feedback when I collect the responses later and allows me to be more present with smaller groups while students take responsibility for checking their work. It also gets students up and moving around the room and normalizes multiple approaches as well as making mistakes as part of the problem solving process.

Quizzes—How often, and how are they made?

Most of the teachers give quizzes—a short graded assessment completed individually under more controlled conditions than other assignments. How often is as varied as the number of teachers who responded: one per unit, twice per unit, once a week, two times per week, 2–3 times per quarter.

If teachers don’t write quiz items themselves or with their team, the quiz items come from practice problems, activities, and adapted cool-downs.

When and how do students revise their work?

Policies for revising work are also as varied as the number of teachers who responded.

Here are some examples:

- Students are given feedback as they complete activities and revise based on their feedback.

- Students revise cool-downs and practice problems.

- Students can revise end-of-unit assessments and cool-downs.

- Students can meet with me at any time to increase a score on previous work.

- Students revise cool-downs if incorrect, and they are encouraged to ask for help if they can’t figure out their own error.

- Students can revise graded assignments during office hours to ensure successful completion of learning goals.

- Students are given a chance to redo assignments after I work with them individually.

- Students can review and revise their Desmos activities until they are graded.

- We make our own retake versions of the assessments.

- Students can do error logs and retakes on summative assessments.

- We complete the student facing tasks together as a whole class on Zoom in ASSISTments. If a student needs to revise the answers they notify me during the session.

Other advice and words of wisdom

I also asked survey participants for any other strategies that both have and haven’t worked in their classrooms. Here are some responses.

What have you tried that has not worked?

- Going over practice problems with the whole class every day. The ones who need it most often don’t benefit from the whole-class instruction, and the ones who don’t need it distract those who do.

- Grading work on the tasks within the lessons for accuracy

- Leaving assignments open for the length of the semester so that students can always see unfinished work

- Going through problems on the board with the whole class does not correct student errors

- Most students don’t check feedback comments unless you look at them together

- Grading images of student work on the classroom activity tasks uploaded by students in our learning management systems

- Providing individual feedback on google classroom assignments was time consuming and inefficient

- Allowing students to submit late and missing work with no penalty

- Trying to grade everything

- Below grade 9, homework really does not work.

- Going over every practice problem communicates that students do not really think about the practice problems on their own.

What else have you tried that has worked well?

- My students do best when I consistently assign practice problems. I have tried giving them an assignment once a week but most students lose track. It is better to give 2–3 problems or reflective prompts after every class, which also helps me get ahead of misconceptions.

- I don’t grade homework since I am unsure who completes it with or for the students.

- A minimum score of 50% on assignments, which allows students the opportunity to recover, in terms of their grade in the class

- Time constraints imposed during remote learning impact the amount and type of homework I give as well as what I grade

- Give fewer problems than normal on second chance assignments

- I have used platforms such as Kahoot to engage students in IM material. I also build Google Forms to administer the Check Your Readiness pre-assessment and End-of-Unit assessments, but I may start using ASSISTments for this in the future.

- The value of homework in high school is okay, but personally I skip good for great.

- Students are able to go back and revise their independent practice work upon recognizing their mistakes and learning further about how to solve the problems.

- Sometimes I select only one or two slides to grade instead of the whole set when I use Desmos activities.

- Allow for flexibility in timing. Give students opportunities for revision.

- Frequent short assessments are better than longer tests, and they allow students to focus on specific skills and get feedback more frequently.

- Especially during the pandemic, many of my students are overwhelmed and underachieving. I am focusing on the core content.

- Homework assignments consist of completing Desmos activities students began in class. Additional slides contain IM practice problems.

- I am only grading the summative assessment for accuracy and all else for completion. I want the students to know that they have the room to learn, try new strategies and be wrong while working on formative assessments.

What grading and homework policies have worked for you and your students that aren’t listed? Share your ideas in the comments so that we can all learn from your experience.

What would you like to learn more about? Let us know in the comments, and it will help us design future efforts like this one so that we can all learn more in a future blog post.

We are grateful to the teachers and facilitators who took the time to share their learning with us.

to the IM Blog and Newsletter

RECENT POSTS

- Leveraging PLCs to Maintain the Magic in Math Communities Throughout the Entire Year April 4, 2024

- Elements of Problem-Based Teaching and Learning February 28, 2024

- Inviting Students to the Math Party: Creating an Inclusive and Engaging Math Community February 6, 2024

- Visualizing IM K-5 Math in Specialized Academic Settings: Part 2 January 18, 2024

- IM Kickoff Message for 2024 January 4, 2024

- Back to School (3)

- Grades 3–5 (105)

- Grades 6–8 (116)

- Grades 9–12 (92)

- Grades K–2 (86)

- Grades K–5 (53)

- Partners (4)

- Professional Learning (74)

- Recent Blog Posts (7)

- Uncategorized (2)

Popular Tags

- About this Blog

- About the Editors

- Contact the Editor

- How to Follow This Blog

A Beginner’s Guide to Standards Based Grading

By Kate Owens , Instructor, Department of Mathematics, College of Charleston

In the past, I was frustrated with grades. Usually they told me very little about what a student did or didn’t know. Also, my students didn’t always know what topics they understood and on what topics they needed more work. Aside from wanting to do well on a cumulative final exam, students had very little incentive to look back on older topics. Through many conversations on Twitter, I learned about Standards Based Grading (SBG) and I implemented an SBG system in several consecutive semesters of Calculus II.

The goal of SBG is to shift the focus of grades from a weighted average of scores earned on various assignments to a measure of mastery of individual learning targets related to the content of the course. Instead of informing a student of their grade on a particular assignment, a standards-based grade aims to reflect that student’s level of understanding of key concepts or standards. Additionally, students are invited to improve their course standing by demonstrating growth in their skills or understanding as they see fit. In this article I will explain the way I implemented SBG and describe some benefits and some drawbacks of this method of assessment.

I chose Calculus II to try an SBG approach because it was my first time teaching the course, so I could build my materials from the ground up. Also, unlike several other courses I teach, the student count remains low — approximately 25 per section. Before the start of the semester, I created a list of thirty course “standards” or learning goals. Roughly, each goal corresponded to one section of the textbook. I organized the thirty standards around six Big Questions that I felt were the heart of the course material. One Big Question was, “What does it mean to add together infinitely many numbers?” The list of standards served as answers to these Big Questions. The list of standards and a description of the grading system were distributed to the students on the first day of class. During the semester, students were given in-class assessments in the form of weekly quizzes, monthly examinations, and a cumulative final examination. The assignments themselves were similar to those found in courses using a traditional grading scheme, but they were assessed differently. Rather than track a student’s total percentage on each particular assignment, for every problem I examined each student’s response and then assigned a score to one or more associated course standards. I provided suggested homework problems both from the textbook and using an online homework platform, but homework did not factor directly into a student’s grade. Instead, if I noticed a student needed more practice at a particular sort of problem, I would direct her to the associated homework problems for additional practice.

During in-class assessments, a single quiz or exam question asking a student to determine if an infinite series converged might also require the student to demonstrate knowledge of (a) “The Integral Test , ” a strategy for determining if a series converges or diverges; (b) “Improper Integrals , ” the process used to evaluate integrals over an infinite interval; (c) some method of integration, such as “Integration by Parts,” and (d) some prior knowledge about how to evaluate limits learned earlier in Calculus I. For each of these concepts, I assign a different score (on a 0-4 scale), roughly correlated with a GPA or letter-grade system. During the semester, I tracked how well each student did on each of the thirty standards.

Since some standards appeared in a multitude of questions throughout the semester, a student’s current score on a standard was computed as the average of the student’s most recent two attempts. Outside of class, each student could re-attempt up to one course standard per week. Usually these re-attempts occurred during office hours and were in the form of a one- or two-question quiz. My rationale for continually updating student scores is that I want grades to reflect a current level of understanding since I want students to aim for a continued mastery of course topics. Over the course of the semester, their scores on standards can move up or down several times. Students are motivated to continue reviewing old material since they know that they might be assessed on those ideas again and their previous grades could go in either direction.

At the end of the term, each student had scores on approximately thirty course standards. To determine a student’s letter grade, I used the following system:

- To guarantee a grade of “A”, a student must earn 4s on 90% of standards, and have no scores below a 3.

- To guarantee a grade of “B” or higher, a student must earn 3s or higher on 80% of course standards, and have no scores below a 2.

- To guarantee a grade of “C” or higher, a student must earn 2s or higher on at least 80% of course standards.

I adapted this system from one Joshua Bowman used. I like it because it captures my feeling that an “A-level” student is a student who shows mastery of nearly all concepts and shows good progress toward mastery on the others; meanwhile, a “B-level” student is one who consistently does B-level work. Also, this system requires students earn at least a passing grade on each course topic. In a traditional system, a student might do very well in some parts of the course, very poorly in others, and earn an “above average” grade. In the system I used, for a student to earn an “above average” grade, they must display at least a passing level of understanding of all course concepts. While students aren’t initially thrilled with this requirement, most are happy once I explain they can re-attempt concepts often (within some specific boundaries) and so the only limit on improving performance is their motivation to do so.

There are three major advantages of tracking scores on standards. First, I can quickly assess student performance:

Second, I can give meaningful advice to students:

Third, I can determine what topics are in need of review or additional instruction:

Students have noted that SBG has several benefits for them as well. They aren’t limited by past performance and can always improve their standing in the course. Many students who describe themselves as “not math people” or those who say they suffer from test anxiety appreciate that their grades can continue to improve, thereby lowering the stakes on any particular assessment. In my office, conversations are almost always about mathematical topics instead of partial credit, why they lost points here or there, or what grade they need on the next test to bring their course average above some threshold. The change in types of conversations during my office hours has been amazing, and for this reason alone I will stick with SBG in the future. Students review old material without prompting, they feel less stress over any individual assignment, we don’t have conversations about partial credit or lost points, and they are able to diagnose their own weaknesses.

With that said, the SBG system also has some disadvantages. First, it takes a thorough and careful explanation to students about the way the system works, why it was chosen, and why I believe it is to their benefit. Student buy-in is critical and it isn’t always easy to attain. I have found that spending a few minutes of class time discussing SBG every day for the first one or two weeks is more helpful than giving a lot of explanation on any particular day. Students need some time to think about what questions and concerns they have, and I encourage them to voice these in class whenever they like. Initially, students think that this system will be too much work for them, or that their course grades will suffer since past strong performance could be wiped out in the future. (In contrast, by the end of the semester, almost all students say they really appreciated this method and felt they learned more calculus than they would have in a traditionally graded course.) Second, several students complained that their grades were not available through our online learning management system; I still haven’t found a way to convince our online gradebook to work in an SBG framework. Instead, students must come to my office to review their scores with me outside of class time. Third, choosing both the correct number of course standards as well as a thorough description of each standard has been challenging. It’s difficult to balance wanting each standard to be as specific as possible while keeping the total number of standards workable from both my viewpoint and that of the students.

After several semesters of using an SBG framework, I believe the benefits to the students outweigh the disadvantages. At this point, I don’t have any firm data about student learning outcomes, but I do have some anecdotal evidence. The feedback from my students about this method of grading and, in particular, the details of my implementation has been very positive. I have received several e-mails from former students who, even semesters later, realize how much SBG changed their perspective on the learning process, or who wished their new instructors would switch to an SBG system. Comments on my student evaluations have mentioned that they feel their grade accurately reflects how much calculus they know, rather than how well they performed on a particular assignment, or how much they were punished from making arithmetic mistakes. As one student noted, “this class was not about how well you could take a test or quiz or do homework online that sucked. It was about the amount of calculus you understood and your effort to be better at it.” As a calculus instructor, this describes my exact goal for my course.

If you are interested in trying an SBG approach in your own courses, here are four questions to jump-start your journey:

- What are the core ideas of your course? What concepts or ideas do you want students to master?

- How many standards do you think you can track? You need them to be specific enough that students can understand exactly what each one means, but you also need to have few enough that your grading workload is manageable. I have 30 for a 16-week semester.

- Will you allow re-attempts? What kinds of limits will you set, if any? I found that limiting students to re-attempting only one standard per week was essential in cutting down my grading workload. This limit also gave students the opportunity to focus on one topic at a time, rather than re-attempting several at once just to see what would stick.

- How will a final assessment, project, or exam count? In my course, a student’s course score on each standard is a weighted average: 80% comes from their pre-final exam score and the remaining 20% comes from the score earned on the final itself. In this way, the final exam contributes about 20% to the student’s letter grade in the class, a figure in line with what is commonly used in my department.

- How will you convert all the scores on standards into a letter grade?

Online SBG Resources

- Twitter hastags: #sbg, #sbgchat, #sblchat

- http://tinyurl.com/SBGLiterature , Scholarly articles related to SBG (list maintained by Matt Townsley)

- http://thalestriangles.blogspot.com/search/label/sbg , SBG blog posts by Joshua Bowman (@Thalesdisciple)

- http://shawncornally.com/wordpress/?p=673 , Standards-Based Grading FAQ by Shawn Cornally

- http://blogs.cofc.edu/owensks/tag/sbg/ , my own blog posts about SBG

- https://plus.google.com/communities/117099673102877564377 , a newly formed Google Plus community for anyone interested in conversations about standards-based or specifications-based grading

19 Responses to A Beginner’s Guide to Standards Based Grading

Hello – I am a senior studying math education at the University of Illinois. I will be student teaching Algebra 1 and Geometry next semester, both of which use Standards Based Grading methods. To be honest, prior to reading your blog post I did not have a very positive opinion of SBG. To me, it seemed like too discrete a way of assigning students an assessment score. However, the comment you stated that I really liked and will stick with me is, “I want grades to reflect a current level of understanding since I want students to aim for a continued mastery of course topics.” This really got me thinking, since I remember all the times both in high school and college when I thought, “If only I had another chance…I really knew that material, but I wasn’t in the right mindset in that moment.” You’re right…SBG allows this to happen, and from a student’s perspective, I can see why this would probably be preferred. It seems like it’s worked really well at the college level with your Calculus students. My one worry is that since I will be using this with freshmen/sophomore students in high school, they will avoid doing well on exams from the start since they know they can just retake it if they don’t do well. While it is clear your students’ motivation increased with your SBG implementation at the college level, I’m not so sure about how to make it work so effectively next semester with my high school students. Do you have any advice on strategies I can use to make it seem like the optimal strategy and have students get the most out of it?

Hi Cam! Thanks for your comment. I hope to throw together some of my thoughts in reply, but please ask me again if I miss a key concern or question.

As it turns out, many of the educators pioneering non-traditional grading approaches are in the K12 community. For example, Frank Noechese (@fnoschese on Twitter; website https://fnoschese.wordpress.com/about/) is a Physics teacher at a secondary school whose standards-based grading philosophy inspired me to make the leap. I have joined a Gooogle+ community of standards-based learning educators and we would love to have your insight as you navigate your own path — join us at https://plus.google.com/communities/117099673102877564377 . Indeed, as the community formed, a few people in the K12 community were happy to sign up. Their experiences will possibly be more aligned with what you’ll see next year than my own. I consider myself a relative newcomer to the SBG/non-traditional grading movement.

As far as your specific concern: “[T]hey will avoid doing well on exams from the start since they know they can just retake it if they don’t do well.” I was worried about this, too. What I found is that limiting the number of standards that could be attempted weekly helped quite a bit. I have 30 standards per 16 weeks, and at a one standard per week cap, students realize they must get close to mastery on at least some topics. Additionally, after the first exam, I try to encourage students as much as possible to come to my office, even if they believe they aren’t ready to re-attempt yet. Sometimes I find that what they are lacking isn’t mathematics, but instead confidence; after a brief chat, I can tell they know the material, and what they seek is encouragement instead of insight.

I think at the heart of your concern is something every educator must face — occasionally we all have students who, for whatever reason, don’t put 100% of their effort into their studies. I wish SBG was a magic wand for this issue, but it isn’t. In my experience, a student who earns a C-minus in a traditional course is very likely to earn a C-minus in my standards-based course for exactly the same reasons. As an instructor, my target is those B or C level students who have a lot of motivation & work ethic (but perhaps who lack confidence) to improve their standing. If a student is determined to fail a course, there isn’t much I can do — but if a student really wants to learn and demonstrate mastery of the material, I see it as my job to cheer them on as they work toward this goal.

I hope that this helps and that you’ll come join our Google+ community and conversation; or find me on Twitter: @katemath.

I am also a senior studying Math Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I will be student teaching next semester in a high school in Champaign that also uses SBG.

I think it’s really interesting that you were able to implement this at the college level. I’ve only heard of this being used in K-12 like you’ve mentioned in your reply to another commenter. Do you feel that this method of grading can be applied more widescale at the college level? I feel like for students who were recently introduced to SBG from a traditional style and then going back to traditional in college is unhelpful to students in the long run. What are your thoughts on this?

Hi Peter, I am hoping to develop an SBG approach in many of my college courses. Next semester, I’ll be implementing an SBG system in a very different course — “College Algebra”, which is the lowest level mathematics course offered at the College of Charleston. My process of switching to an SBG philosophy has been strongly supported by the advice, knowledge, and experience of several online colleagues. I have found that asking lots of questions has led to many fruitful conversations about these issues, so I encourage you to keep asking whatever pops to mind.

As far as students switching from SBG to traditional (or the other direction), this is something I have also wondered about. My own conclusion is that my students face a similar transition between any two instructors. For example, one instructor might focus a lot on grading homework, whereas another doesn’t grade homework but has daily graded quizzes. These challenges are common in every college experience, regardless of grading approach or philosophy. My own experience makes me believe that I should do what I feel is in the best interest of my students, even if this is a different approach than the one taken by my colleagues. I believe that having an open and honest dialogue with both groups — both my colleagues and my students — is important.

Lastly, I’ve received a lot of feedback from prior students that my SBG implementation has changed the way they approach their education for the better. They value our conversations on what it means to learn, on why I think the SBG approach is in both their interest and my own, and also on how their education is essentially their responsibility. It is my job to give them a clear picture as to what they know, where they can improve, and support that improvement whenever possible; it is their job to “do the work,” face the challenge head on, and strive to do the best that they can. I hope to be more of a cheerleader or coach for them, rather than a judge & jury. Students seem to agree that an SBG philosophy allows me to do this and they appreciate the extra work it takes, on their side and my own.

Come join our Google+ community if you’re interested in perspectives apart from my own! We are looking forward to continuing this conversation.

I have been slightly exposed to standards based grading in my last two years of college, and I like it for a few reasons. Namely, I like that it allows for better understanding of individual progress in actual learning than traditional grading, and that it redefines success by allowing students to retest and continue to demonstrate learning and improvement. You also mention several disadvantages, but many of them are results of SBG not being “mainstream”. Clearly, this post shows that standards based grading is a success for Calculus II, and probably for most other math courses, so why is it so difficult to facilitate a switch to SBG several orders of magnitude larger than a single classroom? I understand that education reform is slow to begin with, and gets slower the more you try to reform, but don’t many educators share your perspective on SBG? I know that as a student, I would appreciate standards based grading far more, as it just feels more like learning than traditional grading does. As a future teacher, I want to afford my students this opportunity, but I fear the community and department backlash for being a “new teacher” with new tools. Is there a strategy better than just buckling down and grading in this manner regardless of what anyone else says?

Hi Kyle, I am in the process of planning for next semester. I’ll be teaching several sections of our “College Algebra” course for the first time, and I’m developing an SBG-approach for this class. The class will be quite different than Calculus II. First, there will be many more first-year students. Second, many of them won’t be in science or mathematical majors. I am excited to see how they respond. Third, I’ll have many more students than I did in Calculus II. I’m hoping that it goes well; I plan to blog about what I learn at my own blog (http://blogs.cofc.edu/owensks) and also share my experiences with our Google+ community (https://plus.google.com/communities/117099673102877564377).

You mention: “I fear the community and department backlash for being a “new teacher” with new tools.” I’d be lying if I said this hadn’t crossed my mind as well, especially considering that this semester (Fall 2015) I faced my Third Year Review as part of our Tenure & Promotion process. With that said, I believe it’s my job to use my best professional judgement to figure out what I think is best for my students — meanwhile focusing on being completely transparent about the hows & whys of my choices, whether to my department, my administration, or my students. For me, I can’t imagine going back to a traditional grading philosophy because of the experiences I’ve had in my SBG courses. In outlining the “hows and whys” in my T&P documents, I found that my colleagues were very supportive of my non-traditional approach. After ten years in the university classroom, I have found all the departments I’ve worked with to be places that welcome innovation, so long as that innovation is well-supported by strong professional judgment and honest, ongoing conversations.

Come join our Google+ community and see if everyone else will echo my experience. (I’d be curious to know what they have thought throughout their careers!) Check out https://plus.google.com/communities/117099673102877564377 .

The SBG system is a great step forward in the way teachers and professors approach learning. Speaking from personal experience, this system of grading allows for students to learn at their own pace, to be in charge of their own mastery of the material, and ultimately reinforces the subject matter. With this system, it also prevents one “bad day” from tanking the students grade. Of course their are limits to where and how the SBG system can be applied, but for Calc II, it worked beautifully. Dr. Owens was able to teach one of the best — and yet one of the hardest — classes I’ve ever taken, while allowing me to learn at a rate that suited me and promoted my learning. At least for every math class I have ever taken, SBG would’ve improved the experience by promoting learning as opposed to memorizing.

I have been exposes to SBG along with the concept of visual learning and I have fallen in love with the idea of both of these, but I am getting nervous implementing them in my classroom. I appreciated that you highlighted the pros and the cons that you discovered. The thing that encourages me the most about your review is that you said in your office, discussion went from partial credit to math topics. Isn’t that what the discussions should be? Student learning seems like it would increase so much if students were concerned about learning, not their grade. I think the fact that you said student buy-in is crucial and your four questions are exactly on point. One thing I am really nervous about is the amount of time it seemed as though you put in – and you mentioned that it was for smaller class sizes. Do you have any advice for SBG in a high school with 35 kids to a classroom and 6 difference classes? I think it would be a great benefit to my students and school to move toward SBG but I am afraid to take that first step.

Hi Ali, I was nervous too, before my first SBG class. I think this is just part of the process we all go through when making big changes to our courses. As far as particular advice about your high student count (35*6), I would suggest designing a system that is easy (perhaps Pass/No Pass?) and somewhat automated — for example, if you have access to test generation software, using that to create multiple versions of a single re-assessment rather than having to write each one individually. You’re welcome to join our Google+ community (the link is above) and there you might find people whose SBG experience is more akin to your situation & who can offer even more insight than I can. Good luck 🙂

This is amazing! I do have one question for you: How do you go about recording your grades? What gradebook program do you use?

Same question. Also, on the retakes … were there problems about access? I mean, that some students could make the office hours and others could not?

Hi Kevin. I didn’t have any access problems. I tried to schedule my office hours around times I knew the students would be free. Occasionally, I’d set up an appointment to meet with someone if they really had a conflict. In cases of a busy week, our admin assistants help us proctor, so rarely (once or twice) I left a re-assessment quiz with them for a student to take during normal business hours. I didn’t like this option since I always wanted to sit down and chat with the student before they tried another problem, just to help clear up any underlying misunderstandings of the material.

Since writing this post, I’ve started using our online LMS gradebook. It isn’t a great fix. For example, since students take quizzes a different number of times, this data can’t really be stored in the gradebook. We have a D2L product. I did figure out how to do a “Selectbox” grade, so I have my EMRN system there. I have one column per standard and I update the dropdown menu each time a student makes an attempt at a standard. I also save some data in Excel on my office computer where I feel like I have more control over how calculations are handled.

Hope this helps!

Hi, I am a high school math teacher that teaches a variety of classes from Algebra 1 to co-teaching Dual Credit College Algebra. I really am interested in SBG because it sounds like it focuses more students on math topics instead of their grade all the time. I come across the topic of grades almost every day and I really feel like students are so wrapped up in the grade that they aren’t really learning as much; instead they are trying to memorize. I already implement a rework process within my regular grading system because I really like to see my students find their errors and learn from them. However, I don’t know how well SBG would work in the high school setting. Is SBG something that should be implemented school-wide to help the students understand the process or will in not matter if I am the only one in the high school to implement this? How many of your colleagues use this same system?

Hi Kristie,

So far, none of my colleagues in my department are using an SBG approach. However, there are a few folks around the university who are trying either specifications grading or SBG outside of the math department. I think your students would benefit from this approach even if you’re the only one using it.

Thank you for sharing!! I have just started my 3rd year at a High School and am teaching a new prealgebra course with students who have failed math classes in the past. I felt the SBG would be a good way to get these students back into a growth mindset. So far they have fought against it quite a bit, but mainly because they don’t like change. They also seem opposed to not having extra credit opportunities. I am curious, do you have any thing in SBG that is similar to extra credit?

I felt like EC wouldn’t really fit a SBG approach where learning must be shown. Sinced once you show you have mastered a standard, your grade will reflect that growth and the EC would not be needed.

Kate, This post is one of the most concise and comprehensive sources on Mastery-Based Grading I’ve read. And I’ve read a lot, because I am currently creating my Mastery model. Right now I am struggling with balancing my general and specific outcomes. This is why I am especially interested in your 6 Big Questions and how your specific standards answer these questions. Here is my question: Have you used these Big Questions in your grading in any way? How were they present in your system? In other words, did they play any other role other than helping to create a meaningful structure of the course (which is already a lot!)? Thank you!!!

One of the big struggles with moving to an SBG system is you really have to figure out what it is you want your students to learn. For me, using Big Questions has been really helpful in my course prep because it focuses my attention on what the point of the course is. Also, in past semesters, I’ve often asked students on the final exam “What were the Big Questions in this course?” and I’ve been really impressed with their responses.

I realize that my students will probably, at some point, forget how to do things I’ve taught them (think: quotient rule! integration by parts!). And I think I’m OK with this. What I would like them to remember from my course, even if they forget the details about the methods we’ve implemented, is what kinds of questions we were asking. So in my instruction and documentation, I try to make clear “This is the Big Question we’re struggling with right now”.

So, specifically: 1. I don’t think the Big Questions really are part of their grade (although sometimes I ask my students if they remember them or not). 2. They are present in my system as an organization tool, both when I’m writing my standards at the start of the course, and also as a structure within the semester to bring the conversation back to “What are we even trying to do today?”

I hope this helps!

Thank you Kate, it definitely does! And I can see how important it is for a Calculus course. My general outcomes/big questions for a high school Algebra 2 course may not be so profound, although just like in Calculus, I’d like my student to internalize big ideas about relationships between real world processes, functions, equations, graphs etc. rather than necessary particular types of equations and graphs. So I can totally accept your philosophy and practice! Thanks again, Yelena

This sounds great for math or science classes. I teach high school history, and we focus on citizenship along with reading and writing using evidence to support claims. I find that many of my students come to ninth grade without any knowledge about their country due to more emphasis on reading and math. Elementary grades have stopped teaching history to make sure kids are reading better (and they are not) or working on new math techniques. In using standards based grading for history, how will I be able to assess students’ knowledge based on the state standards accurately. Much of history is based on knowledge. One cannot write about history without learning the basics. When a student reaches the high school level, they should be able to read and write in an acceptable manner, but we all know students are passed on, and I believe part of the problem is this re-do until they get it. I do not think all students will always get it. Life does not always offer second chances, but that is what we are teaching them. That is why we have students who fail, especially when they try college. I know this will not be read or responded to, but I am very skeptical of passing everyone.

Comments are closed.

Opinions expressed on these pages were the views of the writers and did not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the American Mathematical Society.

- Search for:

- Active Learning in Mathematics Series 2015

- Assessment Practices

- Classroom Practices

- Communication

- Early Childhood

- Education Policy

- Faculty Experiences

- Graduate Education

- History of mathematics education

- Influence of race and gender

- K-12 Education

- Mathematics Education Research

- Mathematics teacher preparation

- Multidisciplinary Education

- Online Education

- Student Experiences

- Summer Programs

- Task design

- Year in Review

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

Retired Blogs

- A Mathematical Word

- inclusion/exclusion

- Living Proof

- On Teaching and Learning Mathematics

- PhD + epsilon

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

CLICK HERE TO LEARN ABOUT MTM ALL ACCESS MEMBERSHIP FOR GRADES 6-ALGEBRA 1

Maneuvering the Middle

Student-Centered Math Lessons

Grading Math Homework Made Easy

Some of the links in this post are affiliate links that support the content on this site. Read our disclosure statement for more information.

Grading math homework doesn’t have to be a hassle! It is hard to believe when you have a 150+ students, but I am sharing an organization system that will make grading math homework much more efficient. This is a follow up to my Minimalist Approach to Homework post. The title was inspired by the Marie Kondo book, The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up . Though I utilized the homework agenda for many years prior to the book, it fits right in to the idea of only keeping things that bring you joy.

One thing is for sure, papers do not bring a teacher joy.

For further reading, check out these posts about homework:

- The Homework Agenda Part 2 (Grading Math Homework)

- Should Teachers Assign Math Homework?

I am also aware that homework brings on another conversation:

- what to do if it is not complete AKA missing assignments

Any teacher will tell you that a missing assignment is a giant pain. No one enjoys seeing the blank space in the grade book, especially a middle school teacher with 125+ students. (Side note, my first year I had 157. Pretty much insane.)

Grading Homework, Yes or No?

Goodness, this is a decision you have to make for you and the best interest of your students. In my experience, I would say I graded 85% of assignments for some type of accuracy. I am not a fan of completion grades. The purpose of homework is to practice, but we don’t want to practice incorrectly. Completion grades didn’t work for me, because I didn’t want students to produce low quality work.

Students had a “tutorial” class period (much like homeroom) in which they were allowed 20 minutes a day to work on assignments. I always encouraged students to work on math or come to my room for homework help. Yes, this often led to 40+ students in my room. But, that means 40 students were doing math practice. I love that.

I also believe that many students worked on it during that time because they knew it was for a grade. This helps to build intrinsic motivation.

Grading math homework: USING THE HOMEWORK AGENDA

During the warm up, I circulated and checked for homework completion. Students would receive a stamp or my initials on their Homework Agenda. Essentially, the Homework Agenda (freebie offered later in this post) is a one-pager that kept students homework organized. As a class, we quickly graded the homework assignment. Then, I briefly would answer or discuss a difficult question or two. To avoid cheating, any student who did not have their homework that day were required to clear their desk while we graded.

I would then present a grading scale. This is where I might make math teachers crazy, but I would be generous. Eight questions, ten points each. Missing two problems would result in an 80. I tried to make it advantageous to those who showed work and attempted, yet not just a “gimme” grade.

Students would record their grade on their Homework Agenda. They would repeat this for every homework assignment that week. A completed Homework Agenda would have 4 assignments’ names, with 4 teacher completion signatures, and 4 grades for each day of the week that I assigned homework.

Later in the class or the following day as I circulated, I was able to see on the front of the Homework Agenda how students were doing and discuss personally with them whether or not they needed to see me in tutorials. I was able to give specific praise to students who were giving 110% effort or making improvements.

This is why I love the Homework Agenda.

“There is no possible way, I could collect the assignments individually and return them in a timely fashion. I tried that my first year and there was no hope. Since using it, I am quickly able to provide individual and specific feedback in a timely manner. It opens up conversations and helps be to encourage and be a champion for my students. ”

On Friday, I would collect the Homework Agenda. If during the week you were absent, had an incomplete assignment, or didn’t complete one, Friday was D day. It was going in the grade book on Friday.

Here is my weekly process:

- Collect homework agendas

- Have frank conversation with students who did not have it

- Record grades on paper (mostly to make putting it in the computer faster because they were ordered)

- Record grades in computer

- Send the same email to parents of students that did not turn in the agenda – write one email, then BCC names.

- List names of missing assignments on post-it note next to desk (official, I know)

- Pull students from tutorial time (homeroom) who owed me the homework

- Follow up with any students who were absent Friday and still needed to turn in their homework to me

What About the Missi ng Assignments?

Yes, there will be missing assignments. Yes, students will come to Thursday and have lost their precious agenda. However, it won’t happen often to the same kiddo. My least organized student, who carried everything in their pocket, could fold that agenda up and hang onto it for a week. It was too valuable. Too many grades, too many assignments to redo.

We all know that it is much more work when students don’t complete their assignments. It would be a dream world if everyone turned in their work everyday. Unfortunately, we all live in reality.

We can vent our frustrations over students not doing work, which is legitimate. We can also work towards solutions.

The reality is that not every student has a support system at home. I would love for us to be that voice of inspiration and encouragement. Sometimes that voice sounds like tough love and a hounding for assignments and just being consistent that you value their education and you are not willing to let them give up on it.

They will appreciate it one day and you will be happy you did the extra work.

Want to try the Homework Agenda? Download the template here, just type and go!

This post is part 2 in a two part series. To read part 1, click here.

Digital Math Activities

Check out these related products from my shop.

Reader Interactions

42 comments.

February 29, 2016 at 2:39 pm

How do you prevent kids from cheating and writing a better grade than deserved? And you said 8 questions 10 points each, so do you then give them 20 points for attempting for making it an even 100?

March 1, 2016 at 2:46 am

Hi Lisa, thanks for the question. You make a great point about students wanting to write a better grade than they earned. The first few weeks, I really talk about what it means to be honest and check over their shoulders. As I walk around to check I will make sure everyone is marking their assignment correctly. I even will flip through what has been turned in on Fridays and double check or “spot” check. After several years of doing this, I can only count a handful of times when I had to deal with a situation. You would be surprised! Yes, I tried to make everything easy to grade as well as giving points for effort, especially if the assignment was difficult. Hope that helps!

May 20, 2016 at 10:03 pm

So do you have students turn in all the papers on friday as well or just the agenda? How do you spot check if you only collect the agenda?

May 20, 2016 at 10:38 pm

Hi Heather! Yes, I have students turn in their work with the agenda. If it was a handout/worksheet I provided, I just set the copier to staple it to the back. If it was something out of a text book, they would staple it to the agenda. Hope that helps!

June 4, 2016 at 9:42 pm

The ‘initials’ box on the homework agenda is for you to sign when checking who has it done? Or is the person correcting the paper initializing it?

Do you take off points for students not having an assignment done by the time Friday rolls around? Also, what does the small 1’s and 2’s in the corner of your gradebook mean?

June 5, 2016 at 6:56 am

Hi Alysia! I use the initials box to sign or stamp that it was complete before we graded it. I think you could have the student grading do that, but then you wouldn’t have a good grasp on how kids were doing throughout the week. I really liked going around at the beginning of class and touching base with students/seeing who needed extra help. Yes, I took off points for turing it in late. We had a standard policy on our campus that I followed. Also, by not having initials, it was by default late because it didn’t get checked when I came around. This section of my gradebook was during review for state testing, so the 1’s and 2’s were a little incentive I was running in my classroom. Review can be so boring and tedious, so I tried to spice it up with a sticker/point system for effort and making improvement. Hope this helps!

August 15, 2016 at 6:27 pm

I’m a bit confused how you assigned a grade to the homework assignment. First, you mentioned each problem was assigned 10 points. How did you determine how many points students would receive for each problem? If I read your blog correctly it sounds like you had the students score the assignment, how did you instruct them to score each problem? With 10 points for each problem it seems like there is a potential to have a wide range of scores for each problem based on who is grading it. Also, did the grader score it or did the student give their own work a grade? Sorry for all the questions…thank you!

August 16, 2016 at 6:43 am

Hi Tanya! In my example, there were eight problems but I only counted each as being worth ten points. That would be twenty points left over for trying/showing work/etc. As for marking it, each problem incorrect would be ten points off. Hope that helps. You could have either the student self grade or do a trade and grade method, whichever you felt more comfortable with.

November 28, 2016 at 1:28 am

Can you explain your grading system in the photo on this page where it reads, “Grading without the stacks of paper”? What do the small 1, 2 and 3’s mean? I assume your method on this posting is to avoid the complicated grading, but you’ve got me curious now about what method you were using in your photo. Thanks for clarifying this for me.

January 2, 2017 at 9:48 pm

The small numbers in the corner were used for an incentive. This photo is from a state assessment prep and I used various points for incentives to keep working!

December 26, 2016 at 7:31 pm

I like the idea of trade and grade. Right not I just check hw for completion and they get 5 points for doing the assignment. I treat this like extra credit for them. Most of them will at least attempt the problems and show their work. We also talk about just writing random numbers and how that will get no points.

December 26, 2016 at 7:34 pm

Ugh! The name is Celeste

March 11, 2017 at 7:25 pm

We aren’t allowed to do trade and grade due to privacy issues and legal issues. Otherwise, I do like this idea.

April 1, 2017 at 2:33 pm

I have heard that from other teachers. You could have them check their own, too.

May 30, 2017 at 3:19 pm

Do you allow them to redo and make corrections to their work for credit back? Or does the grade stand no matter what? This is why I go back and forth between correctness and completion. While they need to practice correctly, I don’t like being punitive for getting the answers wrong when they are learning the material for the first time. I want them to practice, and practice correctly. But I also want them to be motivated to persevere and relearn until they master the material.

June 4, 2017 at 6:10 am

Yes, it depended on the school policy but I would typically drop the lowest homework grade at the end of the grading period. If a student is willing to come in and work on their assignment (redo, a new one, etc), then I was always thrilled and would replace the grade! We want kids to learn from their mistakes. 🙂

June 4, 2017 at 1:48 pm

Regarding grading homework, my students have three homework assignments each week, with between 8 and 13 practice problems per assignment. I go through each problem and award 0-3 points per problem. 0 points if they did nothing. And then 1 point for attempting the problem, 1 point for showing necessary/appropriate work, and 1 point for a correct answer. This way, even if students get the problem wrong, they can still get 2 out of 3 points. If a student got each problem wrong, but were clearly trying, I would give them an overall grade of 70%.

June 20, 2017 at 8:13 pm

Great ideas! Love that!

August 31, 2019 at 8:27 am

Are you grading that, or the students?!?!

March 15, 2024 at 10:44 am

It depends! Usually I had my students grade!

June 15, 2017 at 4:54 pm

Do you staple the agenda to a homework packet to hand out on Monday?

June 20, 2017 at 8:07 pm

Yes! Well actually, I would copy it all together or if it was out of a text book, they would staple their work.

June 19, 2017 at 12:16 am

Our district insists that we MUST allow students an opportunity to complete assignments, and we have to accept them late. They do not specify how late though. I was bogged down with tons of late work this last year, and hated it. Can you please share with me your secret of how you handle late work, how late can it be, how much credit does it receive, and how do you grade it? That would help me tremendously. Thank You!

June 20, 2017 at 8:00 pm

We always had school policies for the amount of credit a student could earn, so I would follow that for credit. As far as actually collecting and grading, I did the following: 1. If it was late, I didn’t sign their assignment sheet. Instead I wrote late. 2. They had until Friday, when I collected the assignment sheet and homework to complete it. 3. On Friday, I would collect everything complete or not, and put grades in the grade book. Then, I would send an email to parents letting them know. Usually, kids would then be motivated to come to tutoring to complete any missing grades. I tried to not take any papers other than the Assignment Sheet and its corresponding work.

August 11, 2019 at 2:47 pm

If the students came in the next week and finished the missing assignment, would you give them full points or would they still lose some points for turning the assignment in late?

March 15, 2024 at 10:47 am

Hi, Jackie! I would go with your school’s grading policy.

August 12, 2018 at 1:55 pm

I really hate taking late work but when im forced to I tell my students that the highest grade they could receive is 5 points lower than the lowest grade fromthe student that turned it in on time.

July 17, 2017 at 3:30 pm

What percentage of their overall grade is homework? We are only allowed to give 10% which is why I only grade for completion and showing work. Maybe I’m not understanding correctly, but you have 80 points per assignment roughly?

August 11, 2017 at 5:26 am

Yes, I really tried to be generous and would give points for showing work/effort, to make the grading scale easy. Thanks!

July 30, 2017 at 9:07 pm

Love all the ideas. One question though – do you have any problems with kids not having their homework done, but making note of the correct answers while the class is grading and then just copying those answers later?

August 11, 2017 at 5:18 am

I would suggest to monitor and ask them to have a cleaned off desk if they did not have their assignment. Thanks!

August 22, 2017 at 11:37 am

What does your class look like on Fridays? If you only assign homework M-Th, when do your students get practice on the material that you teach on Friday?

September 2, 2017 at 9:01 pm

Hi Briana! I didn’t assign homework on Fridays, and really tried to plan for a cooperative learning activity if possible. This way we could practice what we did all week.

August 5, 2019 at 9:21 am

I love the idea of the homework agenda. I tried passing out papers and filing them but it was to time consuming. If students are allowed to take the packet back and forth every day what keeps them from sharing their answers to other students from another class period throughout the day? I love that you can put notes/reminders at the bottom of the agenda page.

June 11, 2018 at 11:07 am

Hello! Do you have a editable copy if your homework agenda anywhere? It seems like an interesting concept. I would love to see the overall layout.

March 15, 2024 at 10:13 am

Yes! You can get it here: https://www.maneuveringthemiddle.com/math-homework/

June 13, 2018 at 7:39 pm

What are your procedures for the agenda for those students who were absent the day you graded?

Hi, Brittany! What a great question. I would just collect any absent students’ packets when they return and grade them on my own.

December 2, 2018 at 11:21 am

I often give homework on Quizizz or EdPuzzle which scores for me. The kids who cannot do the assignment at home due to computer or internet issues can do it in tutoring. (I offer before school, after school, and lunch opportunities for tutoring.)

December 9, 2018 at 9:16 pm

How do you set up your homework agenda? In the date box do you put the due date? Or the date they receive the assignment? Do you have an example homework agenda?

December 22, 2018 at 11:34 am

Hi Alyssa! Yes, check out this blog post for more ideas and a sample: https://www.maneuveringthemiddle.com/math-homework/

August 20, 2019 at 11:41 pm

How and when in this process do you grade the homework for accuracy? At your quick glance at the start of class? On Friday after you collect the agenda and associated work? What mechanism do you use to provide constructive, timely feedback to the students?

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Don't Miss the Grand Prize: A $2,500 Office Depot/OfficeMax Card!

Keep Your Calm with These 15 Time-Saving Tips for Grading

Help! I’m up late grading EVERY night, and I’m exhausted.

When you have a mountain of assignments to grade, sometimes even the best Netflix marathon can’t keep you from feeling overwhelmed. If you’re exhausted from staying up late correcting papers every night of the week, put down the red pen and read these teacher-tested tips for making it faster and easier to grade tests, quizzes, essays, and more.

1. Stamp student assignments.

Ellen L.G. Lucy , who’s been teaching for 35 years, says the best teacher tool she ever bought, at the recommendation of a colleague, was a rubber stamp from Vistaprint that says “Seen by Mrs. Lucy.” She stamps papers that she has perused—not corrected completely—so students and parents are aware. If you don’t want to buy a stamp, take Melissa Redden’s advice: Just put a large check mark on the paper in a noticeable color. “I tell parents at the beginning of the year the only grade book grades will be a number grade with a circle around it,” says Redden.

2. Color-code essays.

Students in Jamie Hales ’ class color-code their essays before turning them in. She has them underline their main idea in one color, evidence in another color, and key vocabulary in a third color. “It forces them to make sure they have everything required before turning it in,” says Hales. “I can scan the essays to make sure the colors are all there.”

3. Use a scanner.

For grading multiple choice and true/false questions, you can save yourself hours of tedious work with a scanner. At only three pounds, Apperson’s DataLink 1200 is portable, so you still can do your grading at home if you run out of time at school. The best part is that it comes with DataLink Connect , free software that instantly spits out reports on student performance. So, instead of sorting through every quiz or test, you can quickly look over the report to find common errors and areas you may need to review in class the next day (and quickly get back to watching your favorite shows!).

4. Pass out colored pens.

Have students grade their own multiple choice quizzes and worksheets with a brightly colored pen, like red or green. Ronni Jones says she has her students place their pencils on the floor and asks her most trusted students to act as monitors. She likes the system because it provides kids with instant feedback. “You still have to check to be sure they’re being honest,” says Heather Galiszewski, who also uses this strategy. “I tell my students that if I see anything other than a red pen in their hands, they get an automatic zero.”

5. Grade one section at a time.

When Rebecca Bolton is grading assignments or tests, she first grades all multiple-choice questions for every student. Then she moves on to the second section and so on. She says it typically takes only about two minutes per student to grade her physics exams.

6. Stop using an answer key.

If you’re grading assignments, not formal assessments, correct one paper against another. Ellen L.G. Lucy learned this technique from a teacher friend. For example, put any two students’ papers side by side; find where the answers differ; and then check to see which one is correct. Lucy says this technique catches most errors.

7. Provide an answer blank.

“When I first started teaching, I thought I needed to look at every process on every problem for every student,” says math teacher Cindy Bullard. She started adding answer blanks so she could quickly focus on the areas where students need support. “If they have right answers, a quick scan tells me if their process and notation are correct,” says Bullard. Wendy Badeau uses a similar strategy to save time, which she learned from a fellow teacher: She asks her students to write any multiple-choice or true/false answers in the margins of their papers. “I can line up four or five papers and grade them all at the same time.”

8. Trade and grade.

Sarah Mattie has students write their ID numbers, instead of their names, on assignments. That way, when she asks students to trade papers and correct them, it not only saves her time, but it also keeps grades confidential.

9. Don’t grade everything.

Take a hint from Caitlin Valesco and give a completion grade on bellwork or work that is guided and/or done with a partner. Rather than collecting this work to correct, Valesco simply walks up and down the aisles with a clipboard and checks that the assignments have been completed. Kimberly Darron grades homework for completion by using a bingo dauber color-coding system: green dot for 100 percent complete; blue dot for 50 percent complete; and red dot for 0 percent complete. Darron says she also uses this system to grade journal entries when she’s just scanning for content completion.

10. Spot check during lessons.

Ellen L.G. Lucy often provides students with whiteboards and markers (or has them use the whiteboard app on their iPads) to have them work through math problems and hold up their answers. “The nice thing about this is you can quickly see who is understanding the concept by not only accurate answers but by who holds up their whiteboard the quickest,” says Lucy. Sarah Mattie also uses whiteboards for vocabulary assessment. She asks students to write down the words and hold them up.

11. Alphabetize assignments.

One of the student jobs in Anita Schmuecker’s classroom is to put all turned-in papers in alphabetical order. She says it helps her quickly enter the scores after she grades them.

12. Cut down on grading long assignments.

On longer assignments, Michelle Turner chooses a random 10–15 questions and grades those rather than the entire assignment. She says she chooses a different set of questions for each student.

13. Give verbal feedback.

“I’ve started providing more verbal feedback to students,” says Christa Barberis. “Assessment needs to be something students can work with, and it needs to be authentic,” says Barberis. She typically provides feedback on one aspect of the assignment in which a student did well and one aspect that needs improvement.

14. Use voice typing to dictate your comments.

When Sancha De Burcha needs to write extended feedback on assignments, she uses Google Docs’ voice-typing feature. She downloaded the app for her phone, which allows her to simply dictate her comments rather than write or type them. Bonus of using this method: You end up with a digital record of the feedback. De Burcha cautions, however, that you need to check for typos.

15. Mark all papers before entering grades.

Many teachers mark a single assignment and enter it into the grade book immediately. Mary Elizabeth Allcorn says she saves a lot of time by marking all papers first. She then sets up her grade book and inputs all of the grades at once.

You Might Also Like

10 Awesome and Surprising Ways You Can Use Google Docs in the Classroom

Learn how to use google docs in your classroom to make learning interesting for your students and teacher life a lot easier for you! Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

- Our Mission

Getting Started With Standards-Based Grading

An approach to grading that deepens learning by highlighting strengths and identifying areas for improvement.

A student scans their report card: A in science, Bs in math and history, C in language arts. Receiving an A in science communicates to the student that they are doing well and have reached a level of mastery; the other grades indicate areas to work on. But which parts within language arts, specifically, need work? Traditional grading can leave students and families confused and frustrated, as they give few pointers about which concepts need attention and rarely offer a clear pathway for improvement.

One way to provide transparency in grading and improve student learning is to utilize standards-based grading (SBG). SBG provides transparency to families on their student’s strengths in a subject area and gives guidance on which standards need improvement.

According to research, standards-based grading creates a more equitable learning environment , as students are given clear learning targets and rubrics that they can use to reach mastery of classroom content. SBG empowers learners not just to learn concepts but to master them, perpetuating deeper learning of content.

Research studies also show that using standards-based grading helps ensure that grading and reporting is more meaningful, accurate, and fair . Additionally, SBG ensures that homework, behavior, attendance, notebooks, and group work are not factored into a student’s grade. Standards-based grading allows students to be graded solely on mastery of course content, which can improve student motivation and help with equity .

Implementing SBG at the Classroom Level

The greatest front work in the classroom for effectively launching SBG is defining standards and creating rubrics for them. Once the standards are defined, the rubrics act as a communication tool for a student’s level of performance and provide feedback and a path to reach mastery.

Mastery is usually measured on a 1–4 or 1–5 scale, with each level of mastery clearly defined on the rubric. During the grading term, student learning on the target is recorded. Teachers track student progress, give appropriate feedback, and adapt instruction to meet student needs.

The key difference between traditional and standards-based grading is that SBG is responsive to learning. When students begin a new target, teachers present an introductory lesson and base materials for the target. As students progress, they are offered more complex material, working their way up the rubric to mastery.

SBG is similar to a staircase, with students climbing up one step at a time until they reach the top. After receiving instruction, some students progress immediately up the stairs, but others need more time. Teachers regularly provide feedback, reteach, and offer additional opportunities to reassess, so that every learner has the opportunity to reach the top.

It’s also essential to build in time for redos and reassessment of standards. By building in redo time during warm-ups, using classroom centers, or as a built-in grade-improvement day, students have the time and space to get feedback, practice concepts, and reach mastery. This built-in time also sets the foundational message that it values the time that individuals need to learn concepts, reducing anxiety and sending a clear message that the teacher values deeper learning over basic understanding.

SBG is powerful because it provides a framework to measure student progress regularly. When teachers continuously understand students’ mastery, they can better adapt instruction to meet students’ needs. SBG causes education to be more effective and engaging. The grade book provides clear communication of students’ level of understanding on standards and clarifies what concepts the student needs help to master.

Piloting Standards-Based Grading

Start with those interested in rethinking grading practices. Creating teams of teachers and leaders with this common goal provides a platform for collaboration. This collaborative effort will help with decision-making for building consistency and fidelity across classrooms, schools, and the division. It also serves as a natural way to build capacity. When making widespread changes such as moving to SBG, starting small and providing structures and platforms for collaboration is critical.

Two critical structures include SBG coaches and a universal platform for reporting student growth. A coaching structure to consider is utilizing a division lead coach, a lead school-based coach, and a grade-level coach who facilitates communication and provides implementation support. A universal platform for reporting student growth builds fluidity in communication and trust among stakeholders.

Barriers to SBG and Solutions

Before starting SBG, it’s crucial to know some of the barriers and how to avoid having to stop before you begin. Create provocative strategies to ensure stakeholder buy-in while developing a pilot program and increasing capacity among staff.

1. Collaboration. Create a shared space for resources, ideas, and opportunities for collaboration and discussion for teachers and leaders.

2. Standards. Create common standards in reader-friendly language based on state requirements using teachers’ and instructional leaders’ teams. Substandards are helpful for clarity. Be prepared for multiple iterations and revisions over time.

3. Grade reporting. When the goal is to empower students to take ownership of their learning, it’s critical to provide transparency to guardians, increase honesty in skill-mastery reporting, and reduce teacher time.

Before getting started, create a conversion rubric for letter grades with a team that represents multiple grade levels to avoid having report cards with changes that may confuse or concern stakeholders. This provides a method to report both scores and letter grades.