Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

The People Power Revolution, Philippines 1986

- Mark John Sanchez

For a moment, everything seemed possible. From February 22 to 25, 1986, hundreds of thousands of Filipinos gathered on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue to protest President Ferdinand Marcos and his claim that he had won re-election over Corazon Aquino.

Soon, Marcos and his family were forced to abdicate power and leave the Philippines . Many were optimistic that the Philippines, finally rid of the dictator, would adopt policies to address the economic and social inequalities that had only increased under Marcos’s twenty-year rule. This People Power Revolution surprised and inspired anti-authoritarian activists around the world.

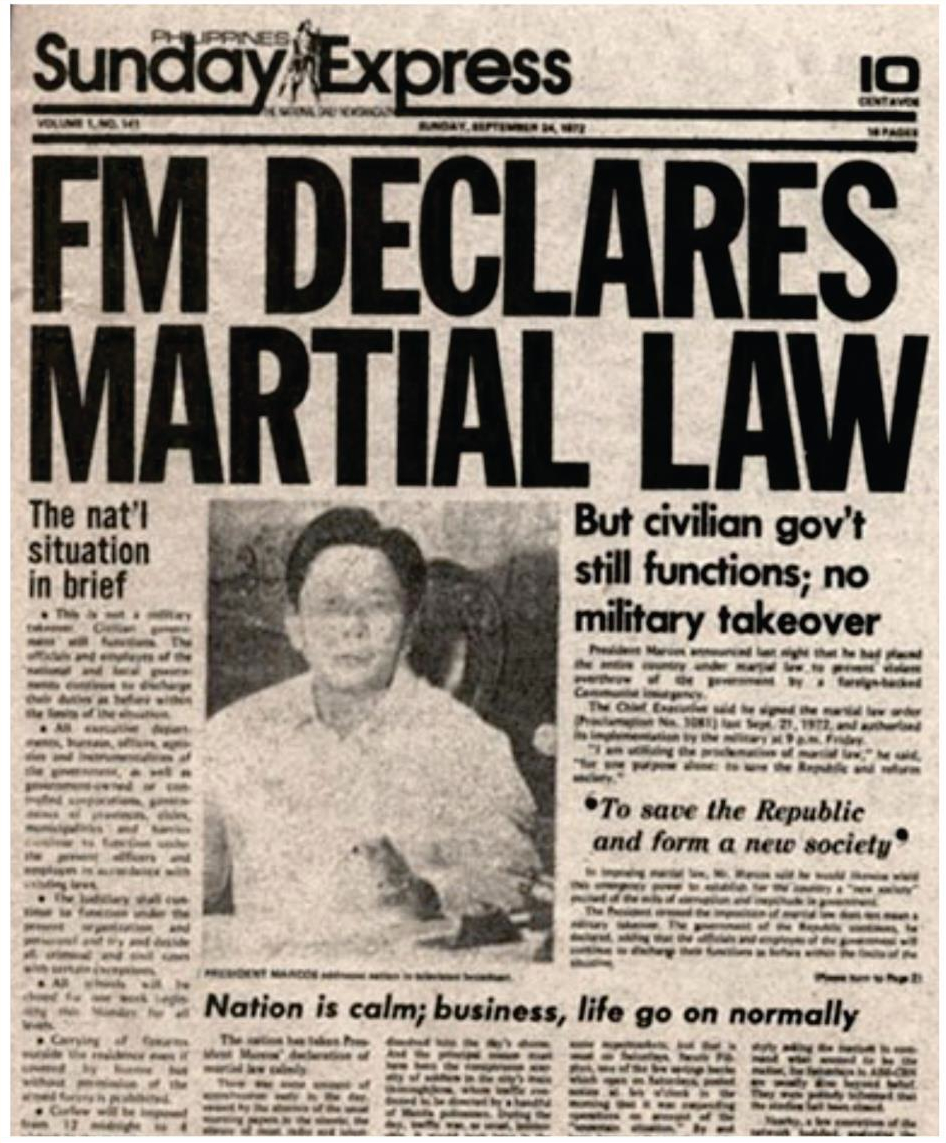

Ferdinand Marcos had been president of the Philippines since 1965. After declaring martial law in 1972, he suspended and eventually rewrote the Philippine constitution, curtailed civil liberties, and concentrated power in the executive branch and among his closest allies. Marcos had tens of thousands of opponents arrested and thousands tortured, killed, or disappeared.

The Sunday Express headline from September 24, 1972 shortly after Marcos declared martial law.

For two decades, Filipinos lived under authoritarian rule while Marcos and his allies enriched themselves through ownership of Philippine press and industry outlets and through the siphoning of funds from U.S., World Bank , and International Monetary Fund loans.

The People Power movement had been building since well before Marcos’s declaration of martial law. Committed activists who organized underground in the Philippines, in exile, and in the diaspora worked tirelessly to broadcast news of the Marcoses’ human rights violations and ill-gotten wealth globally.

For many years, however, much of the world—the U.S. government in particular—was perfectly willing to overlook the corruption of the Marcoses in exchange for an anti-Communist bulwark in Southeast Asia.

By the mid-1980s, however, foreign policy calculations had shifted against Marcos in crucial ways.

Senator Benigno Aquino in an interview with Pat Robertson before his assassination in 1983.

The August 1983 assassination of Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. was seen by many around the world as a particularly brazen act of political retribution. Furthermore, rumors about Marcos’s health (he was suffering from lupus and regularly undergoing dialysis at the time) led many of his allies in the Philippines and beyond to begin speculating about the dictator’s successors.

When Ferdinand Marcos boldly called for a “snap election” in a 1985 interview with David Brinkley, Marcos’s opponents weighed whether this was an opportunity or a trap. Many times before, Marcos had tipped the electoral balances in his favor, through a rewriting of laws, outright violence, and other forms of manipulation and intimidation.

Much of the Philippine Left decided to boycott the election, fearful that participation would only serve to further legitimize the regime. The remainder of the opposition movement eventually coalesced around the widow of Senator Aquino, Corazon “Cory” Aquino.

Just as many feared, Marcos claimed victory in the election. This time, though, Filipinos refused to accept this lie. On February 22, citizens took to the streets on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). Cardinal Jaime Sin, the Archbishop of Manila, called upon Filipinos to support the peaceful protests.

Cardinal Jaime Sin pictured in 1988.

Marcos ordered the military to repress the mass action. However, a faction of military officers refused to clamp down on the protestors and chose instead to defect. This group included soldiers who had grown frustrated with corruption in the military and the Marcos regime and had earlier formed the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM).

When Marcos ordered the military to arrest detractors, Cardinal Sin called upon the people to shield them. The Catholic radio organ, Radio Veritas , became a major control center for protest communications during the People Power movement.

Close Marcos ally President Ronald Reagan eventually sent word through Senator Paul Laxalt that it was time to “cut, and cut cleanly,” signaling that Marcos no longer had the backing of his most powerful ally. On the evening of February 25, the U.S. government facilitated Marcos’s escape to Hawaii, where he would remain until his death in 1989.

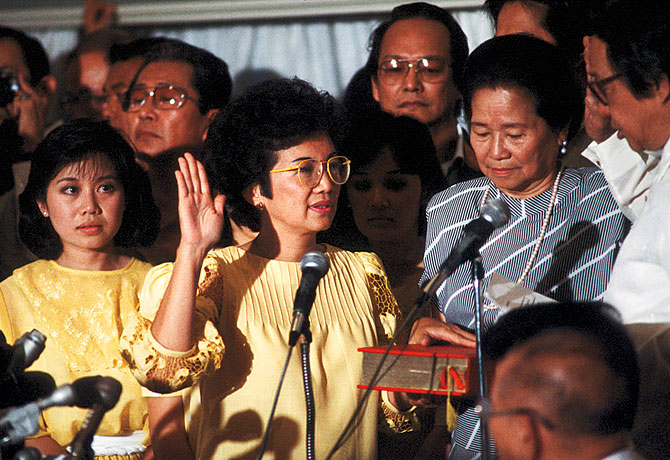

Later that same night, protestors stormed Malacañang Palace, exposing the opulent wealth that the Marcos family had amassed during their time in power. As Corazon Aquino was sworn in as President, Filipinos were hailed around the world as an example of peaceful revolution and the restoration of democracy.

Corazon Aquino was inaugurated as the 11th president of the Philippines on February 25, 1986 at Sampaguita Hall.

The road ahead would not be so simple, however. In the years since 1986, the legacy of the People Power Revolution has remained uncertain. Aquino faced several coup attempts during her time in power, many of them led by the very same RAM that had helped facilitate her rise to power.

The agricultural and economic reform that many Filipinos hoped for in a post-Marcos world did not come. Peace talks with the Communist Party of the Philippines dissolved and leftists continued to be maligned, attacked, and hunted.

Many Filipinos expressed nostalgia for the very dictator that had been overthrown. And there have been ongoing projects of historical revisionism in the Philippines that sanitized the Marcos years.

The Marcos family have returned to the Philippines and to positions of political prominence: Ferdinand Marcos’s widow Imelda became a congresswoman and his daughter Imee a governor. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the dictator’s son and evident successor to his father’s legacy, ran for vice president in 2016 and finished a close second. Bongbong refused to concede and, to this day, continues his legal challenges to the election.

President Rodrigo Duterte talks to Imee Marcos at a wedding ceremony in Manila, September, 2016.

The most concerning outcome of the 2016 Philippine elections, however, was the election of Rodrigo Duterte as president. A close ally of the Marcoses, Duterte has drawn upon Marcos’s script for authoritarian power. He has arrested prominent opponents, curtailed civil liberties, and claimed that discipline is what is most needed for the Philippine nation.

Most infamously, Duterte launched a campaign that has resulted in tens of thousands of extrajudicial murders committed by police and military forces.

The People Power Movement offers several lessons. We can see the courageous solidarities and coalitions that might mobilize against authoritarian restrictions on civil liberties. But we must also look at the importance of finding ways to build anew and address the grievances and injustices that have made such authoritarians so popular in the first place.

The EDSA protests in 1986 were a remarkable moment in Philippine history, a moment filled with the sense of unlimited hope and possibility. And for those with democratic dreams, it provides both a lesson and a warning for the battles ahead.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Reflecting on Edsa

In the history of every modern-day democracy, the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution stands out as the most astonishing, not only because it removed without bloodshed a cruel dictator in Ferdinand Marcos, but also because, all intents and purposes taken together, it has at least healed the malignancy of the Filipino nation’s broken soul.

But the wound of disunity threatens us again. Three decades later, Filipinos are still wanting in terms of the things they deserve from their own government. Edsa should have taught us how to elect the right persons for public office. But across the many regions of the country, we can only agonize in disbelief as we witness overlords in absolute control of our beloved land.

It is wrong, however, to put the blame on the ordinary Filipino. The majority did not benefit from Edsa. In fact, whole families still roam our busy streets, scavenging for soiled food. While towering edifices rise in the metropolis, thousands of children have remained hungry and without a home. As a society left behind by the modernity of the Western way of life, we can only indict our leaders, past and present, who exploited Edsa and abused its spirit and memory. Indeed, we have many cunning politicians who shamelessly invoke the concept of human welfare, or even the pursuit of happiness, in order to justify and brandish their particular style of tyranny.

History tells us that an autocrat who rules by means of some populist agenda is not impaired as to his knowledge of the timeless relevance of the principles of justice. But he distorts and uses the same in order to advance his vested interests. In the desire to destroy his enemies, a dictator only has one marching order to his docile and willing accomplices: to follow him without question. This type of loyalty is perhaps the most dangerous there is. It is the same kind of blind obedience that has caused honorable men to kill in the name of their god!

When President Corazon Aquino came to power in 1986, we believed then that it is not really intellectual brilliance but human virtue that legitimizes political leadership. And yet, in reality, it is the dictator who actually foregoes the advice of academics, as he will do things as he sees fit. He is so afraid of the wisdom of old. He fears engaging the titans of history. Edmund Burke elaborates: “What is the use of discussing a man’s abstract right to food or to medicine? … In this deliberation I shall always advise to call in the aid of the farmer and the physician, rather than the professor.”

Edsa gave the world a new way of looking at things. We stand firm that, as a people, we cannot allow those who hold positions of power to take advantage of us. Any form of violent counterrevolution can only mean that oppression has been maintained, although the oppressors may have changed the color of their skin. Burke says it well: “Kings, in one sense, are undoubtedly the servants of the people, because their power has no other rational end than that of the general welfare; but it is not true that they are, in the ordinary sense anything like servants.”

The raison d’être of Edsa is not Aquino or Marcos. Edsa is the story of the Filipino as a freedom-loving people. Burke appears precise: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.”

It is every generation’s principal right to overthrow any ruthless despot. Freedom, ultimately, is an instrument for societal transformation. Unless we prevent ourselves from degenerating into a country that treats justice and the rights of people as some sort of a commodity that only the affluent can enjoy, the potent force of the radical change that was Edsa will continue to elude us.

Christopher Ryan Maboloc is assistant professor of philosophy at Ateneo de Davao University. He has a master’s degree in applied ethics from Linkoping University in Sweden. He was trained in democracy and governance at the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in Bonn and Berlin, Germany.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Subscribe to our opinion columns

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Reflection on the Memoirs of THE EDSA REVOLUTION: TODAY'S POLITICAL SYSTEM

Related Papers

Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz

Michael Charleston B Chua

This essay attempts to illustrate the role of U.S. foreign policy in Philippine politics during the reign of Ferdinand Marcos, along with the assassination of popular opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., leading to the comparatively peaceful transition that followed the fraudulent 1986 election. This point marked the end of Marcos’ slowly perishing regime and paved the way for a new democratic government under Corazon Aquino. Both the tragic event that left Aquino dead only minutes after his arrival from exile at Manila airport on August 23, 1983, as well as the subsequent change in U.S. perception of the ageing Marcos and his ability to manage domestic problem were crucially important in helping the country overcome and eventually end 21 years of suppressive presidential rule. Furthermore, it tries to cast light on the complex developments during the final years of Marcos’ autocratic rule and Washington’s constant inability and reluctance to critically discuss political reality in the Philippines. It also talks about Marcos’ ability to hold off political opponents, among which Aquino was the most influential and with whom he shared a special relationship of mutual respect and even admiration.

Caroline Hau

This glossary, by no means exhaustive, presents potted histories of keywords and phenomena that are evocative of the Marcos era (1965-1986) in the Philippines. Terms in bold font have their own entries. Forthcoming in Iyra Buenrostro-Cabbab, Mary Grace Concepcion, JPaul S. Manzanilla, and Ruel V. Pagunsan, eds., "Remembering Martial Law"

Pacific Journalism Review : Te Koakoa

Sheila Coronel

I was a martial law baby. My generation grew up watching the unending spectacle of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. Remember this was the 20th Century, long before YouTube and Netflix. I would have preferred to watch Zombie Apocalypse but that wasn’t an option. There were only five TV channels and three newspapers, all owned by Marcos cronies. We didn’t call it 'fake news' then but it was vintage 1970s propaganda—obvious and crude. I was in first grade when Marcos was first elected president. I studied across the street from Malacañang, in a school for girls run by the Sisters of the Holy Ghost. I remember that in the 1960s, the streets around the presidential mansion were busy, filled with traffic and commerce. On Thursdays, hundreds flocked to the church nearby to pray to St. Jude, patron of hopeless causes. I was barely in my teens when martial law was declared. Suddenly the streets were silenced. The palace gates were shuttered. Barbed wire barricades kept people away. T...

LSE Southeast Asia Working Paper Series

Julio Teehankee

On 25 May 2022, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., son, and namesake of the late dictator, was proclaimed by Congress as the 17th president of the Republic of the Philippines. His landslide victory in the presidential election was astounding, coming 36 years after his family was ousted from the presidential palace in a military-backed people power uprising. He has also emerged as the first majority president in the post-Marcos period garnering a historic 31,629,783 (59%) votes, with a margin of almost 31% ahead of his closest rivals. His successful presidential campaign was built around the myth, propagated on social media, and actively embraced by a large segment of the public (both young and old) that the Marcos dictatorship was a “golden age” of peace and prosperity, as opposed to the long-held and well-documented accounts of a violent and corrupt rule that left the country poor. While it is possible to say that the rise of Rodrigo Duterte’s strongman populism in 2016 cleared the stage for the Marcos restoration in 2022, authoritarian nostalgia has been simmering in the public’s political preference since the mid-2000s. The inability to adequately address the legacies of authoritarianism has impacted the overall consolidation of democratic gains. This paper would like to address the following questions: First, what factors contributed to the erosion of the post-Marcos liberal reformist political order? Second, how did the Marcos dynasty succeed in staging a political comeback? Third, what are the prospects for Philippine democracy under a restored Marcos presidency?

Journal of Democracy

Richard Javad Heydarian

The essay analyzes the historical relevance, confluence of contributing factors, and broader systemic implications of the emphatic electoral victory of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in the 2022 Philippine presidential election. Accordingly, it provides an overview of the structural vulnerabilities of Philippine democracy, the contingent factors that facilitated Marcos Jr.'s electoral success, the personal background and predisposition of the new president, and the likely key features and policy thrusts of his presidency. Overall, the essay frames Marcos Jr.'s victory as the latest victory of authoritarian populism. In historical terms, it represents the latest "counterrevolution" in modern history, namely, the successful return to power of the ancien régime through systematic exploitation of the vulnerabilities of postrevolutionary regimes.

ian paraguya

Maria Teresa Galera

This paper talks about what made the Martial Law and, consequently, the People Power possible but looks at the bigger picture beyond just the personalities involved in the struggle, seeing it as a struggle of the Filipino people.

Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Southeast Asia

To fact-check and counter the historical denialism of the Marcos family, there is need for a counterfactual history analysis of the failings of the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution.

RELATED PAPERS

Nicola Lalli

Silvia Mazzoni

Sagar Barhate

Russian Meteorology and Hydrology

Damyan Barantiev

BCGBD CBGCV

Annals of Botany

Claudio Pugliesi

2011 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics (WASPAA)

Kenichi Kumatani

Journal of Materials Science

Venkat Venkataramani

HEGEL - HEpato-GastroEntérologie Libérale

jean SCHOLTES

Passage Tidsskrift For Litteratur Og Kritik

Karen-Margrethe Lindskov Simonsen

DRS2018: Catalyst

Ingrid Pettersson

Curtin毕业证成绩单 Curtin毕业证成绩单

Journal of early childhood and infant psychology

Daniel Scott Schechter

MATEC Web of Conferences

Noorsidi Aizuddin Mat Noor

Turkiye Klinikleri Archives of Lung

Mehmet Karadag

African Geographical Review

Garth Myers

Journal of Social Ontology

International Journal of Business and Management

Muhammad Yusuf

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

Kishan or biki shah

Nurvita Trianasari

Revista de Enfermagem Referência

Adeloye Michael

Giampaolo Queiroz Pellegrino

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Home / Essay Samples / Sociology / Culture and Communication / EDSA Revolution: Significance and Impact on Philippine Democracy

EDSA Revolution: Significance and Impact on Philippine Democracy

- Category: Sociology , Social Issues

- Topic: Culture and Communication , Effects of Social Media , Media Influence

Pages: 2 (859 words)

Views: 1219

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

2Nd Amendment Essays

Freedom of Speech Essays

Civil Rights Essays

Censorship Essays

Discrimination Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->