- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Is Economic Inequality Really a Problem?

Yes, but the answer is less obvious than you might think.

By Samuel Scheffler

Dr. Scheffler is a professor of philosophy.

It is impossible to ignore the stark disparities of income and wealth that prevail in this country, and a great many of us are troubled by this state of affairs.

But is economic inequality really what bothers us? An influential essay published in 1987 by the philosopher Harry Frankfurt suggests that we have misidentified the problem. Professor Frankfurt argued that it does not matter whether some people have less than others. What matters is that some people do not have enough. They lack adequate income, have little or no wealth and do not enjoy decent housing, health care or education. If even the worst-off people had enough resources to lead good and fulfilling lives, then the fact that others had still greater resources would not be troubling.

When some people don’t have enough and others have vastly more than they need, it is easy to conclude that the problem is one of inequality. But this, according to Professor Frankfurt, is a mistake. The problem isn’t inequality as such. It’s the poverty and deprivation suffered by those who have least.

Professor Frankfurt’s essay didn’t persuade all his fellow philosophers, many of whom remained egalitarians. But his challenge continued to resonate and, in 2015, even as concerns about economic inequality were growing in many corners of society, he published a short book in which he reaffirmed his position.

And Professor Frankfurt, it seems, has a point. Those in the top 10 percent of America’s economic distribution are in a very comfortable position. Those in the top 1 percent are in an even more comfortable position than those in the other 9 percent. But few people find this kind of inequality troubling. Inequality bothers us most, it seems, only when some are very rich and others are very poor.

Even when the worst-off people are very poor, moreover, it wouldn’t be an improvement to reduce everyone else to their level. Equality would then prevail, but equal misery is hardly an ideal worth striving for.

So perhaps we shouldn’t object to economic inequality as such. Instead, we should just try to improve the position of those who have least. We should work to eliminate poverty, hunger, bad schools, substandard housing and inadequate medical care. But we shouldn’t make the elimination of inequality our aim.

Is this the correct conclusion? I think not. Economic inequality matters a great deal whether or not it matters “as such.”

Start by considering two points that Professor Frankfurt himself would accept. First, to succeed in eliminating poverty and securing decent conditions of life for all Americans would require raising taxes on the rich significantly. Although the ultimate purpose would not be to reduce inequality, the indirect effect would be to do just that. So even if inequality as such is not the problem, reducing inequality is almost certainly part of the solution.

Second, even if economic inequality is not a problem in and of itself, it can still have bad effects. Great disparities of income and wealth, of the kind we see in the United States today, can have damaging effects even when nobody is badly off in absolute terms. For example, the wealthiest may be able to exert a disproportionate share of political influence and to shape society in conformity with their interests. They may be able to make the law work for them rather than for everyone, and so undermine the rule of law. Enough economic inequality can transform a democracy into a plutocracy, a society ruled by the rich.

Large inequalities of inherited wealth can be particularly damaging, creating, in effect, an economic caste system that inhibits social mobility and undercuts equality of opportunity.

Extreme inequality can also have subtler and more insidious effects, which are especially pronounced when those who have the least are also poor and lack adequate resources, but which may persist even if everyone has enough. The rich may persuade themselves that they fully deserve their enormous wealth and develop attitudes of entitlement and privilege. Those who have less may develop feelings of inferiority and deference, on the one hand, and hostility and resentment on the other. In this way, extreme inequality can distort people’s view of themselves and compromise their relations with one another.

This brings us to a more fundamental point. The great political philosopher John Rawls thought that a liberal society should conceive of itself as a fair system of cooperation among free and equal people. Often, it seems, we do like to think of ourselves that way. We know that our society has always been blighted by grave injustices, beginning with the great moral catastrophe of slavery, but we aspire to create a society of equals, and we are proud of the steps we have taken toward that ideal.

But extreme inequality makes a mockery of our aspiration. In a society marked by the spectacular inequalities of income and wealth that have emerged in the United States in the past few decades, there is no meaningful sense in which all citizens, rich and poor alike, can nevertheless relate to one another on an equal footing. Even if poverty were eliminated and everyone had enough resources to lead a decent life, that would not by itself transform American citizenship into a relationship among equals. There is a limit to the degree of economic inequality that is compatible with the ideal of a society of equals and, although there is room for disagreement about where exactly the limit lies, it is clear that we have long since exceeded it.

If extreme economic inequality undermines the ideal of a society of equals, then is that merely one of its bad effects, like its corrupting influence on the political process? Or, instead, is that simply what it is for economic inequality to matter as such?

For practical purposes, it doesn’t make much difference which answer we give. In either case, the imperative that Professor Frankfurt identified — the imperative to ensure that all citizens have enough resources to lead decent lives — is of the utmost importance. It is appalling that so many people in a society as wealthy as ours continue to lack adequate housing, nutrition, medical care and education, and do not enjoy the full benefits of the rule of law. But addressing Professor Frankfurt’s imperative is not enough. Extreme economic inequality, whether it matters as such or “merely” for its effects, is pernicious. It threatens to transform us from a democracy into a plutocracy, and it makes a mockery of the ideal of equal citizenship.

If, as they say, every crisis is an opportunity, then America today is truly the land of opportunity. Of the many opportunities with which our current crises have presented us, one of the most basic is the opportunity to rethink our conception of ourselves as a society. Going forward, we must decide whether we wish to constitute ourselves as a genuine society of equals or, alternatively, whether we are content to have our relations with one another structured by an increasingly stark and unforgiving economic and social hierarchy.

Samuel Scheffler is a professor of philosophy and law at New York University and the author, most recently, of “Why Worry About Future Generations?”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

To Fight Inequality, America Needs to Rethink Its Economic Model

F or decades, economic policy in most liberal democracies has been premised on two core beliefs: that free markets would maximize economic growth, and that we could address inequality through redistribution.

The recent revival of industrial policy, championed by President Biden, is a clear repudiation of the first of these beliefs. It reflects a growing recognition among economists that state intervention to shape markets and steer investment is crucial for fostering innovation, protecting strategically important sectors like semi-conductors, and tackling the climate emergency.

But we must also reassess the second belief—that taxes and transfers alone can address the vast inequalities that have brought American democracy to such a perilous juncture. Doing so will lead us towards a more fundamental rethink of our economic institutions, and the values that guide them.

This is partly a pragmatic response to economic reality. The massive increase in inequality since the 1980s in America was mostly driven not by a reduction in redistribution, but by the growing gap in earnings between low skill workers, whose wages have suffered an unprecedented period of stagnation, and college-educated professionals whose salaries have continued to soar. And while inequality has increased in most advanced economies, that it is so much higher in the U.S. compared to Europe is mostly the result of bigger gaps in earnings than lower levels of redistribution. In other words, even if America were to increase the generosity of the welfare state to European levels it would still be much more unequal.

But the need to look beyond redistribution is about more than economics, it is about resisting the narrow focus on money that dominates most debates about inequality, and the tendency to reduce our interests as citizens to those of consumers. While government transfers are essential for making sure that everyone can meet their basic needs, simply topping up people’s incomes fails to recognize the importance of work as a source of independence, identity, and community, and does nothing to address the insecurity faced by gig-economy workers, or the constant surveillance of employees in Amazon warehouses.

This is not purely a moral issue. According to a recent paper by economists at Columbia and Princeton, the Democratic Party’s shift towards a “compensate the losers ” strategy in the 1970s and 1980s—taxing high earners to fund welfare payments to the poor—played a key role in driving away less educated voters, who disproportionately support “pre-redistributive” policies like higher minimum wages and stronger unions.

Things are moving in the right direction. President Biden has put “good jobs” at the centre of his economic agenda, claiming that “a job is about [a] lot more than a pay cheque. It’s about your dignity. It’s about respect.” Leading economists such as Dani Rodrik at Harvard and Daron Acemoglu at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s have started to challenge the prevailing orthodoxy that such jobs are an inevitable by-product of a well-functioning market economy. This shift of focus towards the production or supply side of the economy has been variously termed “ productivism ”, “ modern supply-side economics ” and “ supply-side progressivism .”

Read More: Why Joe Biden is Running on the Economy

And yet, to grasp the full potential of these ideas we must look beyond economics to philosophy. Contemporary thinkers such as Michael Sandel and Elizabeth Anderson have done much to put questions about work back on the agenda. But for a systematic vision of a just society that recognizes the fundamental importance of work we should revisit the ideas of arguably the 20th-century’s greatest political philosopher, John Rawls—an early advocate for what we would now call “pre-distribution,” who argued that every citizen should have access to good jobs, a fair share of society’s wealth, and a say over how work is organized.

The publication of Rawls’s magnum opus A Theory of Justice in 1971 marks a watershed moment in the history of political thought, drawing favourable comparisons to the likes of John Stuart Mill, Immanuel Kant, even Plato. Rawls’s most famous idea is a thought experiment called the “original position.” If we want to know what a fair society would look like, he argued, we should imagine how we would choose to organize it if we didn’t know what our individual position would be—rich or poor, Black or white, Christian of Muslim— as if behind a “veil of ignorance.”

Our first priority would be to secure a set of “basic liberties,” such as free speech and the right to vote, that are the basis for individual freedom and civic equality.

When it comes to the economy, we would want “fair equality of opportunity,” and we would tolerate a degree of inequality so that people have incentives to work hard and innovate, making society richer overall. But rather than assuming that the benefits would trickle down to those at the bottom, Rawls argued that we would want to organize our economy so that the least well-off would be better off than under any alternative system—a concept he called the “difference principle.”

This principle has often been interpreted as justifying a fairly conventional strategy of taxing the rich and redistributing to the poor. But Rawls explicitly rejected “welfare state capitalism” in favour of what he called a “property-owning democracy.” Rather than simply topping up the incomes of the least well off, society should “put in the hands of citizens generally, and not only of a few, sufficient productive means for them to be fully cooperating members of society.”

Doing so is essential for individual dignity and self-respect, he argued, warning that “Lacking a sense of long-term security and the opportunity for meaningful work and occupation is not only destructive of citizens’ self-respect but of their sense that they are members of society and not simply caught in it. This leads to self-hatred, bitterness, and resentment” – feelings that could threaten the stability of liberal democracy itself. A focus on work is also necessary for maintaining a sense of reciprocity since every able citizen would be expected to contribute to society in return for a fair reward.

Rawls’s philosophy offers the kind of big picture vision that has been missing on the center-left for a generation—a unifying alternative to ‘identity politics’ grounded in the best of America’s political traditions. It also points towards a genuinely transformative economic programme that would address the concerns of long-neglected lower-income voters, not simply for higher incomes but for a chance to contribute to society and to be treated with respect.

At the heart of this vision is the idea that productive resources—both human capital (skills) and ownership of physical capital (like stocks and shares)—should be widely shared. People’s incomes would still depend on their individual effort and good fortune, but wages and profits would be more equal, and there would be less need for redistribution.

How might we bring this about?

First, we would need to ensure equal access to education, irrespective of family background. Sadly, the reality in America today is that children from the richest fifth of households are fivetimes more likely to get a college degree than those from the poorest fifth. Achieving true equality of opportunity is a generational challenge, but the direction should be towards universal early years education, school funding based on need rather than local wealth, and a higher education system where tuition subsidies and publicly-funded income-contingent loans guarantee access to all.

We also need to shift focus towards the more than half of the population who don’t get a four-year college degree. Our obsession with academic higher education—justified in part on the basis that this will generate growth, which in turn will benefit non-graduates—is simply the educational equivalent of trickle-down economics. At the very least, public subsidies should be made available on equal terms for those who want to follow a vocational route, as the U.K. is doing through the introduction of a Lifelong Learning Entitlement from 2025, providing every individual with financial support for four years of post-18 education, covering both long and short courses, and vocational and academic subjects.

Second, we must address the vastly unequal distribution of wealth . Thewealthiest 10 % of Americans have around 70 % of all personal wealth compared to roughly 2% the entire bottom half. Sensible policies like guaranteed minimum interest rates for small savers and tax breaks to encourage employee share ownership would encourage middle-class savings. But to shift the dial on wealth inequality we should be open to something more radical, like a universal minimum inheritance paid to each citizen at the age of eighteen, funded through progressive taxes on inheritance and wealth. If developments in AI push more income towards the owners of capital, something like this will become necessary.

Finally, we need to give workers real power to shape how companies are run. The idea that owners, or shareholders, should make these decisions is often treated as an immutable fact of economic life. But this “shareholder primacy” is neither natural nor inevitable about, and in most European countries employees have the right to elect representatives to company boards and to ‘works councils’ with a say over working conditions. This system of ‘co-management’ allows owners and worker to strike a balance between pursuing profit and all the other things we want from work – security, dignity, a sense of achievement, community – in a way that makes sense for a particular firm. The benefits of co-management appear to come at little or no cost in terms of profits or competitiveness, are popular with managers, and may even increase business investment and productivity.

Critics will no doubt denounce these ideas as “socialism.” But as we have seen, they have impeccable liberal credentials, and are perfectly compatible with the dynamic market economy that is so vital both for individual freedom and economic prosperity. Neither are they somehow “un-American.” As Elizabeth Anderson has reminded us , America was the great hope of free market egalitarians from Adam Smith through to Abraham Lincoln, whose dreams of a society of small-scale independent producers were dashed by the industrial revolution, and would have been horrified by the hierarchy and subservience of contemporary capitalism. Rawls’s ideal of property-owning democracy can help us revive this vision for the 21 st century.

Still, even sympathetic readers might wonder whether there is any point talking about a new economic paradigm when the U.S. has failed even to raise the Federal minimum wage since 2009. But this would be to ignore the lessons of history. As the neoliberal era comes to an end, we should learn from its leading architects Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, who were nothing if not bold, and saw their ideas go from heresy to orthodoxy in a single generation. As Friedman put it “Only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around."

It often takes a generation or two before the ideas of truly great thinkers start to shape real politics. Now, for the first time since the publication of A Theory of Justice just over half a century ago, there is an urgent need and appetite for systematic political thinking on a scale that only a philosopher like Rawls can provide. In the face of widespread cynicism, even despair about the American project, his ideas offer a hopeful vision of the future whose time has come.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- The New Face of Doctor Who

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Happens if Trump Is Convicted ? Your Questions, Answered

- The Deadly Digital Frontiers at the Border

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 31 Most Anticipated Movies of Summer 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

6 facts about economic inequality in the U.S.

Rising economic inequality in the United States has become a central issue in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, and discussions about policy interventions that might help address it are likely to remain at the forefront in the 2020 general election .

As these debates continue, here are some basic facts about how economic inequality has changed over time and how the U.S. compares globally.

How we did this

For this analysis, we gathered data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Bank . We also used previously published data points from Pew Research Center surveys and analyses of outside data.

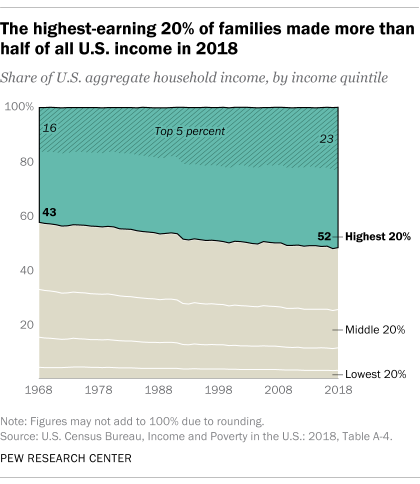

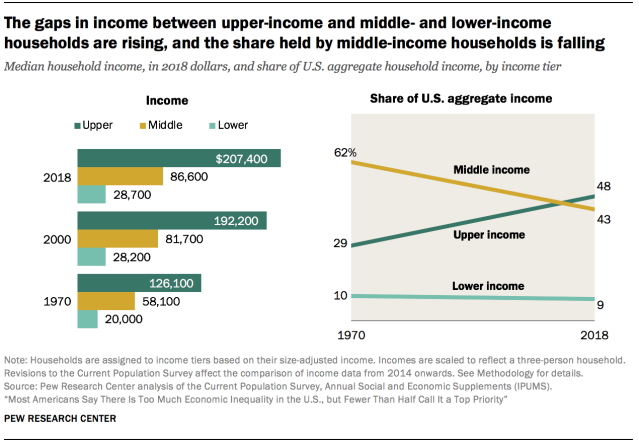

Over the past 50 years, the highest-earning 20% of U.S. households have steadily brought in a larger share of the country’s total income. In 2018, households in the top fifth of earners (with incomes of $130,001 or more that year) brought in 52% of all U.S. income, more than the lower four-fifths combined, according to Census Bureau data.

In 1968, by comparison, the top-earning 20% of households brought in 43% of the nation’s income, while those in the lower four income quintiles accounted for 56%.

Among the top 5% of households – those with incomes of at least $248,729 in 2018 – their share of all U.S. income rose from 16% in 1968 to 23% in 2018.

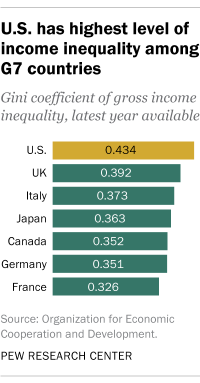

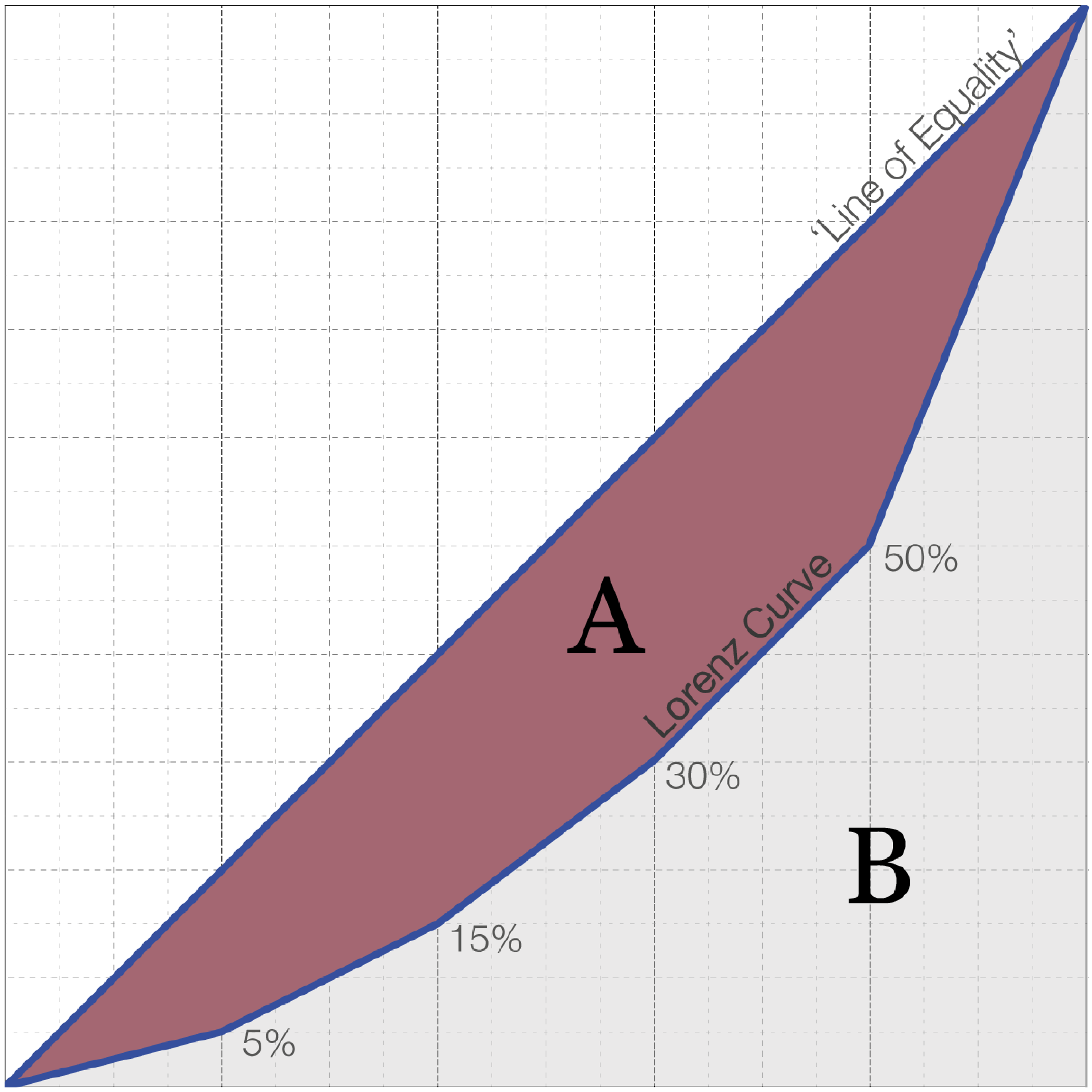

Income inequality in the U.S. is the highest of all the G7 nations , according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . To compare income inequality across countries, the OECD uses the Gini coefficient , a commonly used measure ranging from 0, or perfect equality, to 1, or complete inequality. In 2017, the U.S. had a Gini coefficient of 0.434. In the other G7 nations, the Gini ranged from 0.326 in France to 0.392 in the UK.

Globally, the Gini ranges from lows of about 0.25 in some Eastern European countries to highs of 0.5 to 0.6 in countries in southern Africa, according to World Bank estimates .

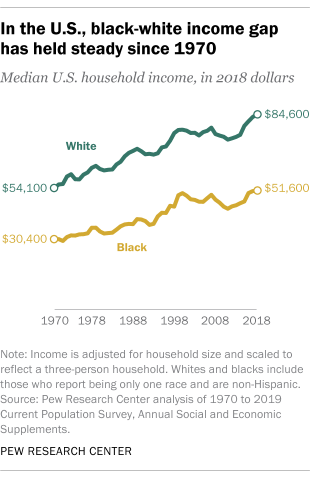

The black-white income gap in the U.S. has persisted over time. The difference in median household incomes between white and black Americans has grown from about $23,800 in 1970 to roughly $33,000 in 2018 (as measured in 2018 dollars). Median black household income was 61% of median white household income in 2018, up modestly from 56% in 1970 – but down slightly from 63% in 2007, before the Great Recession , according to Current Population Survey data.

Overall, 61% of Americans say there is too much economic inequality in the country today, but views differ by political party and household income level. Among Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP, 41% say there is too much inequality in the U.S., compared with 78% of Democrats and Democratic leaners, a Pew Research Center survey conducted in September 2019 found.

Across income groups, U.S. adults are about equally likely to say there is too much economic inequality. But upper- (27%) and middle-income Americans (26%) are more likely than those with lower incomes (17%) to say that there is about the right amount of economic inequality.

These views also vary by income within the two party coalitions. Lower-income Republicans are more likely than upper-income ones to say there’s too much inequality in the country today (48% vs. 34%). Among Democrats, the reverse is true: 93% at upper-income levels say there is too much inequality, compared with 65% of lower-income Democrats.

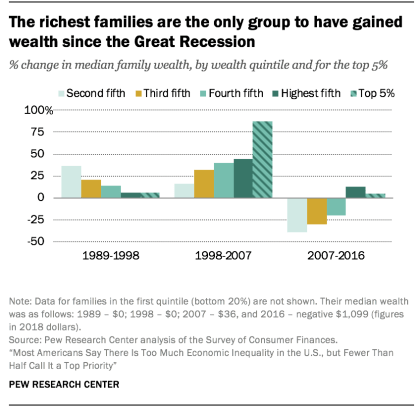

The wealth gap between America’s richest and poorer families more than doubled from 1989 to 2016, according to a recent analysis by the Center. Another way of measuring inequality is to look at household wealth, also known as net worth, or the value of assets owned by a family, such as a home or a savings account, minus outstanding debt, such as a mortgage or student loan.

In 1989, the richest 5% of families had 114 times as much wealth as families in the second quintile (one tier above the lowest), at the median $2.3 million compared with $20,300. By 2016, the top 5% held 248 times as much wealth at the median. (The median wealth of the poorest 20% is either zero or negative in most years we examined.)

The richest families are also the only ones whose wealth increased in the years after the start of the Great Recession. From 2007 to 2016, the median net worth of the top 20% increased 13%, to $1.2 million. For the top 5%, it increased by 4%, to $4.8 million. In contrast, the median net worth of families in lower tiers of wealth decreased by at least 20%. Families in the second-lowest fifth experienced a 39% loss (from $32,100 in 2007 to $19,500 in 2016).

Middle-class incomes have grown at a slower rate than upper-tier incomes over the past five decades, the same analysis found . From 1970 to 2018, the median middle-class income increased from $58,100 to $86,600, a gain of 49%. By comparison, the median income for upper-tier households grew 64% over that time, from $126,100 to $207,400.

The share of American adults who live in middle-income households has decreased from 61% in 1971 to 51% in 2019. During this time, the share of adults in the upper-income tier increased from 14% to 20%, and the share in the lower-income tier increased from 25% to 29%.

- Economic Inequality

- Economy & Work

- Income & Wages

- Income, Wealth & Poverty

- Personal Finances

Katherine Schaeffer is a research analyst at Pew Research Center .

1 in 10: Redefining the Asian American Dream (Short Film)

The hardships and dreams of asian americans living in poverty, a booming u.s. stock market doesn’t benefit all racial and ethnic groups equally, black americans’ views on success in the u.s., wealth surged in the pandemic, but debt endures for poorer black and hispanic families, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

5 Essays to Learn More About Equality

“Equality” is one of those words that seems simple, but is more complicated upon closer inspection. At its core, equality can be defined as “the state of being equal.” When societies value equality, their goals include racial, economic, and gender equality . Do we really know what equality looks like in practice? Does it mean equal opportunities, equal outcomes, or both? To learn more about this concept, here are five essays focusing on equality:

“The Equality Effect” (2017) – Danny Dorling

In this essay, professor Danny Dorling lays out why equality is so beneficial to the world. What is equality? It’s living in a society where everyone gets the same freedoms, dignity, and rights. When equality is realized, a flood of benefits follows. Dorling describes the effect of equality as “magical.” Benefits include happier and healthier citizens, less crime, more productivity, and so on. Dorling believes the benefits of “economically equitable” living are so clear, change around the world is inevitable. Despite the obvious conclusion that equality creates a better world, progress has been slow. We’ve become numb to inequality. Raising awareness of equality’s benefits is essential.

Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford. He has co-authored and authored a handful of books, including Slowdown: The End of the Great Acceleration—and Why It’s Good for the Planet, the Economy, and Our Lives . “The Equality Effect” is excerpted from this book. Dorling’s work focuses on issues like health, education, wealth, poverty, and employment.

“The Equality Conundrum” (2020) – Joshua Rothman

Originally published as “Same Difference” in the New Yorker’s print edition, this essay opens with a story. A couple plans on dividing their money equally among their children. However, they realize that to ensure equal success for their children, they might need to start with unequal amounts. This essay digs into the complexity of “equality.” While inequality is a major concern for people, most struggle to truly define it. Citing lectures, studies, philosophy, religion, and more, Rothman sheds light on the fact that equality is not a simple – or easy – concept.

Joshua Rothman has worked as a writer and editor of The New Yorker since 2012. He is the ideas editor of newyorker.com.

“Why Understanding Equity vs Equality in Schools Can Help You Create an Inclusive Classroom” (2019) – Waterford.org

Equality in education is critical to society. Students that receive excellent education are more likely to succeed than students who don’t. This essay focuses on the importance of equity, which means giving support to students dealing with issues like poverty, discrimination and economic injustice. What is the difference between equality and equity? What are some strategies that can address barriers? This essay is a great introduction to the equity issues teachers face and why equity is so important.

Waterford.org is a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving equity and education in the United States. It believes that the educational experiences children receive are crucial for their future. Waterford.org was founded by Dr. Dustin Heuston.

“What does equality mean to me?” (2020) – Gabriela Vivacqua and Saddal Diab

While it seems simple, the concept of equality is complex. In this piece posted by WFP_Africa on the WFP’s Insight page, the authors ask women from South Sudan what equality means to them. Half of South Sudan’s population consists of women and girls. Unequal access to essentials like healthcare, education, and work opportunities hold them back. Complete with photographs, this short text gives readers a glimpse into interpretations of equality and what organizations like the World Food Programme are doing to tackle gender inequality.

As part of the UN, the World Food Programme is the world’s largest humanitarian organization focusing on hunger and food security . It provides food assistance to over 80 countries each year.

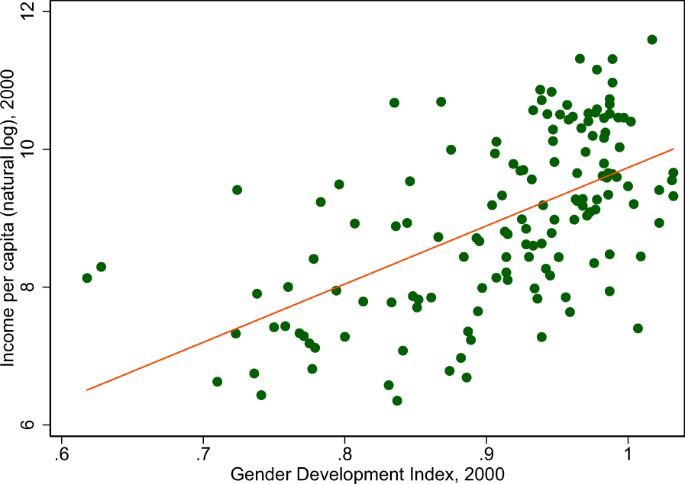

“Here’s How Gender Equality is Measured” (2020) – Catherine Caruso

Gender inequality is one of the most discussed areas of inequality. Sobering stats reveal that while progress has been made, the world is still far from realizing true gender equality. How is gender equality measured? This essay refers to the Global Gender Gap report ’s factors. This report is released each year by the World Economic Forum. The four factors are political empowerment, health and survival, economic participation and opportunity, and education. The author provides a brief explanation of each factor.

Catherine Caruso is the Editorial Intern at Global Citizen, a movement committed to ending extreme poverty by 2030. Previously, Caruso worked as a writer for Inquisitr. Her English degree is from Syracuse University. She writes stories on health, the environment, and citizenship.

You may also like

16 Inspiring Civil Rights Leaders You Should Know

15 Trusted Charities Fighting for Housing Rights

15 Examples of Gender Inequality in Everyday Life

11 Approaches to Alleviate World Hunger

15 Facts About Malala Yousafzai

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

The economic gains from equity

- Final Paper by Buckman et al

- Comment by Fortin

- Comment by Hurst

- General Discussion

- Data & Programs

Subscribe to the Economic Studies Bulletin

Shelby r. buckman , shelby r. buckman graduate student - stanford university laura y. choi , laura y. choi vice president, community development - federal reserve bank of san francisco mary c. daly , and mary c. daly president and chief executive officer - federal reserve bank of san francisco lily m. seitelman lily m. seitelman graduate student - boston university discussants: nicole fortin and nicole fortin professor - university of british columbia erik hurst erik hurst frank p. and marianne r. diassi distinguished service professor of economics - booth school of business, university of chicago, deputy director - becker friedman institute @erikhurst.

September 8, 2021

The paper summarized here is part of the Fall 2021 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) , the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. The conference draft of the paper was presented on September 9, 2021 at the Fall 2021 BPEA conference . The final version was published in the Fall 2021 edition by Brookings Institution Press on June 7, 2022. Read all papers published in this edition here» Submit a proposal to present at a future BPEA conference here»

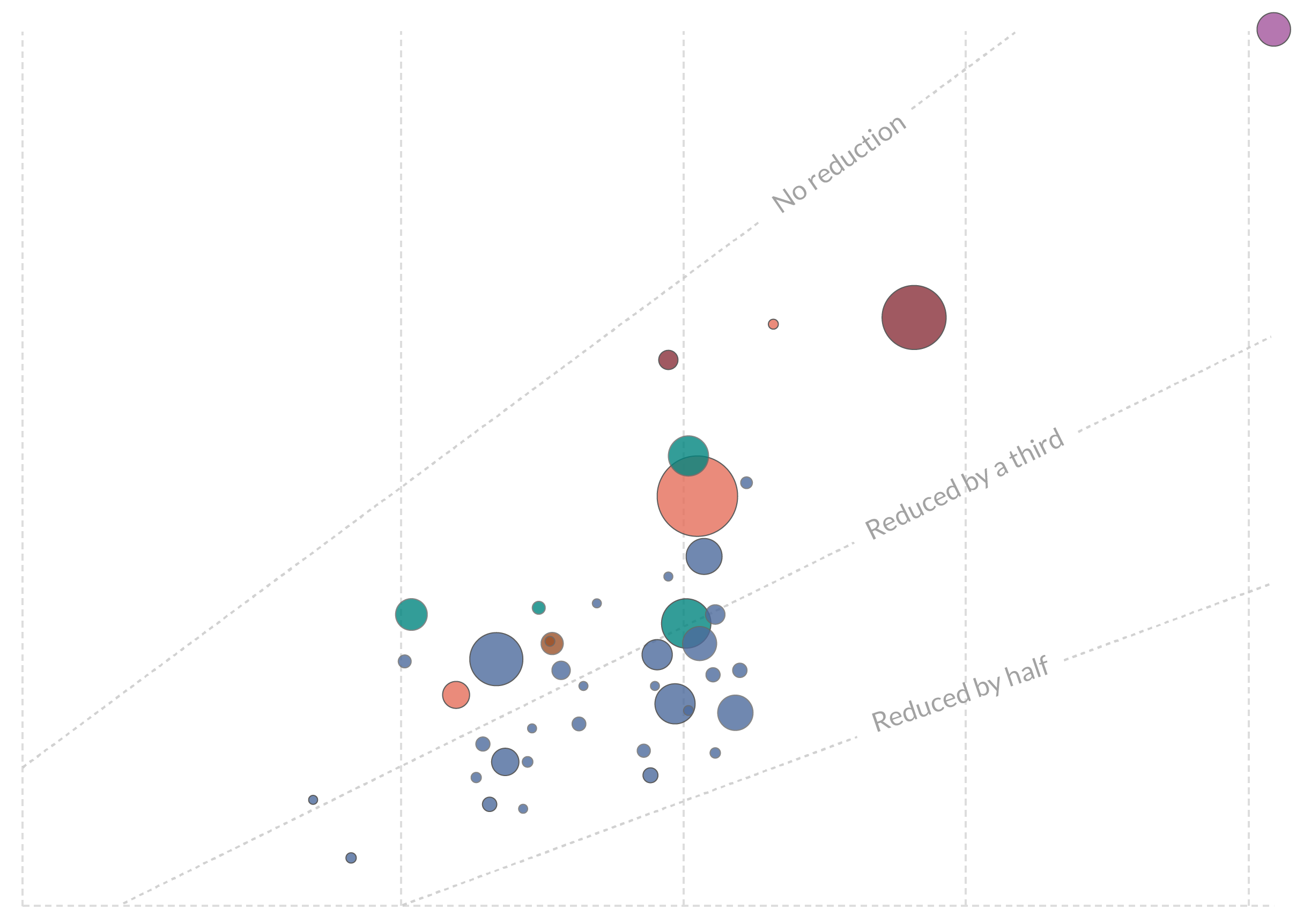

Longstanding racial and ethnic disparities in the United States have hurt not only the people who experience the disparities but have hurt all Americans by depressing U.S. economic output by trillions of dollars over the past 30 years, suggests a paper discussed at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) conference on September 9.

The authors— Shelby R. Buckman, Laura Y. Choi, Mary C. Daly¸ and Lily M. Seitelman, all of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco—considered differences from 1990 to 2019 among white, Black, and Hispanic men and women, ages 25-64. They looked at disparities using five metrics: employment (the percentage of people with jobs); hours worked; educational attainment (the level of education completed); educational utilization (the extent to which people are in jobs that fully use their education); and earnings gaps not explained by those factors.

Then, in The economic gains from equity , they conducted a thought experiment, asking: “How much larger would the U.S. economic pie be if opportunities and outcomes were more equally distributed by race and ethnicity?” Their answer is $22.9 trillion over the 30-year period.

“The persistence of systemic disparities is costly, and eliminating them has the potential to produce large economic gains,” the authors write. Standard economic models often assume markets work efficiently and thus suggest explanations—such as unmeasured differences in productivity or cultural differences—that would support the existence and persistence of racial and ethnic gaps. The authors instead assume talent and job and educational preferences are distributed evenly across race and ethnicity. They then show the economic effects of disparities that hold people back from fully realizing their potential.

The persistence of systemic disparities is costly, and eliminating them has the potential to produce large economic gains

“The opportunity to participate in the economy and to succeed based on ability and effort is at the foundation of our nation and our economy,” they write. “Unfortunately, structural barriers have persistently disrupted this narrative for many Americans, leaving the talents of millions of people underutilized or on the sidelines. The result is lower prosperity, not just for those affected, but for everyone.”

“With considerable pressures weighing on U.S. economic potential in coming decades, the time seems right to take a new perspective and imagine what’s possible if equity is achieved,” the authors conclude.

The authors note in the paper that they built on the work of others and cite in particular the work, dating to 1985, of four African-American economists: William A. Darity, Patrick L. Mason, William E. Spriggs, and the late Rhonda M. Williams.

Acknowledgments

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper.

Buckman, Shelby R., Laura Y. Choi, Mary C. Daly¸ and Lily M. Seitelman. 2021. “The Economic Gains from Equity.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Fall. 71-111.

Fortin, Nicole. 2021. “Comment on ‘The Economic Gains from Equity’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Fall. 112-130.

Hurst, Erik. 2021. “Comment on ‘The Economic Gains from Equity’.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Fall. 130-135.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Shelby R. Buckman is a graduate student in economics at Stanford University and a past employee at FRBSF during which time she did the majority of her contribution to this paper; Laura Y. Choi is vice president of community development at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco; Mary C. Daly is president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, CRIW member, and IZA research fellow; Lily M. Seitelman is a graduate student in economics at Boston University and a past employee at FRBSF during which time she did the majority of her contribution to this paper. Beyond these affiliations, the authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this paper or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are currently not officers, directors, or board members of any organization with an interest in this paper. No outside party had the right to review this paper before circulation. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1840990 and Grant No. DGE-1840990.

hIstory of bpea

Discussants

Economic Studies

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Robin Brooks

May 23, 2024

Janice C. Eberly, Donald Kohn, Jón Steinsson, Pierre Yared

David Wessel

May 22, 2024

Economic Inequality

By Joe Hasell, Pablo Arriagada, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

How are incomes and wealth distributed between people? Both within countries and across the world as a whole?

On this page, you can find all our data, visualizations, and writing relating to economic inequality.

This evidence shows us that inequality in many countries is very high and, in many cases, has been on the rise. Global economic inequality is vast and compounded by overlapping inequalities in health, education, and many other dimensions.

But economic inequality is not rising everywhere. Within many countries, it has fallen or remained stable. And global inequality – after two centuries of increase – is now falling too.

The large differences we see across countries and over time are crucial. They show us that high and rising inequality is not inevitable, and that the extent of inequality today is something that we can change.

Explore Data on Economic Inequality

About this data.

This data explorer provides a range of inequality indicators measured according to two different definitions of income obtained from different sources.

- Data from the World Inequality Database relates to inequality before taxes and benefits.

- Data from the World Bank relates to either income after taxes and benefits or consumption, depending on the country and year.

Further information about the definitions and methods behind this data can be found in the article below, where you can also explore and compare a much broader range of indicators from different sources:

OWID Data Collection: Inequality and Poverty

Explore a wide range of indicators on inequality and poverty and compare sources.

Research & Writing

How has income inequality within countries evolved over the past century?

While the steep rise of inequality in the United States is well-known, long-run data on the incomes of the richest shows countries have followed a variety of trajectories.

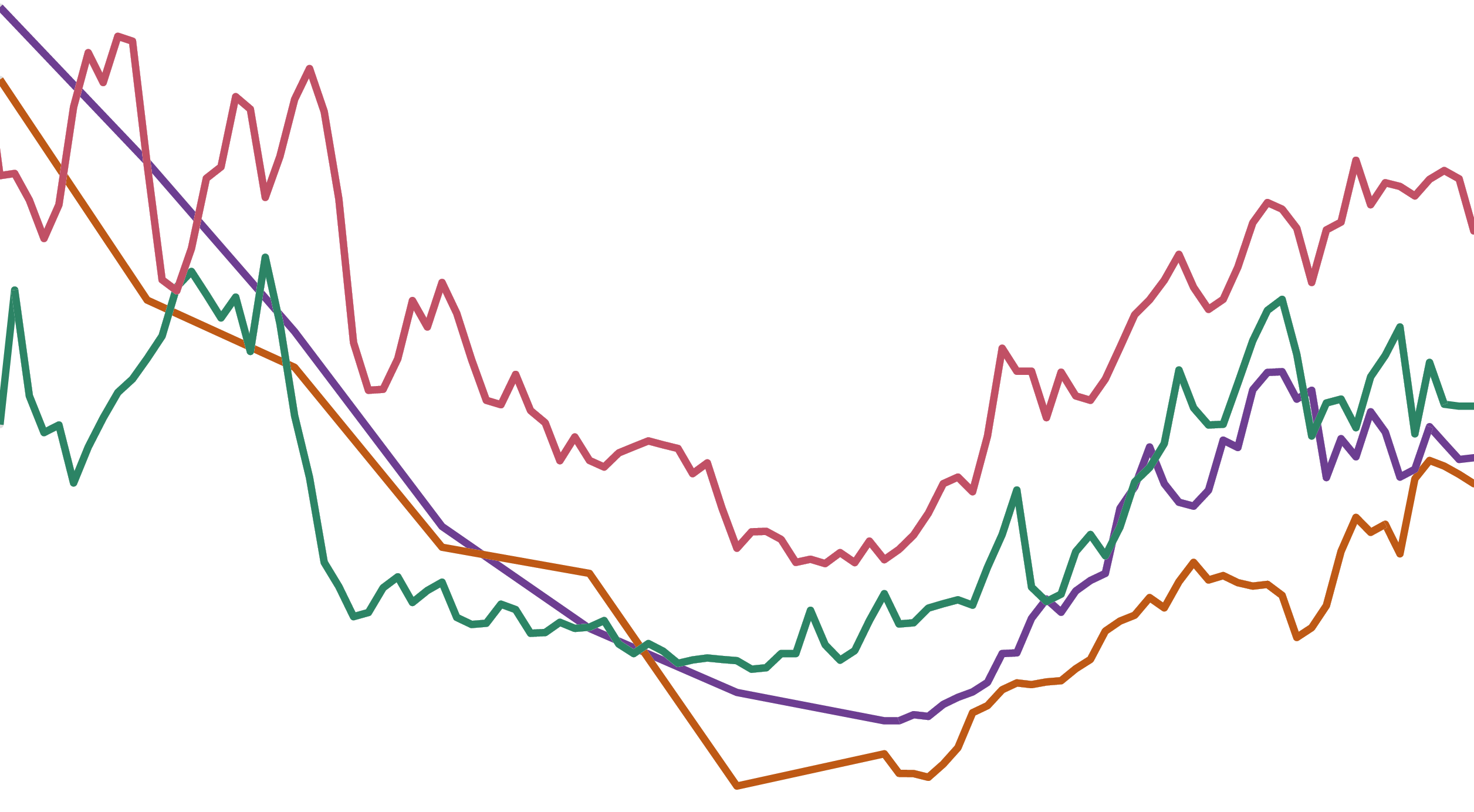

Income inequality before and after taxes: How much do countries redistribute income?

The redistribution of income achieved by governments through taxes and benefits varies hugely.

Income Inequality Over the Long-run

How has inequality in the United Kingdom changed over the long run?

How unequal were pre-industrial societies?

Global inequality.

The history of global economic inequality

Global Inequality of Opportunity

Global economic inequality: what matters most for your living conditions is not who you are, but where you are

How is inequality defined and measured.

Joe Hasell and Pablo Arriagada

Measuring inequality: what is the Gini coefficient?

Interactive charts on economic inequality, cite this work.

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

This article is concerned with social and political equality. In its prescriptive usage, ‘equality’ is a highly contested concept. Its normally positive connotation gives it a rhetorical power suitable for use in political slogans (Westen 1990). At least since the French Revolution, equality has served as one of the leading ideals of the body politic; in this respect, it is at present probably the most controversial of the great social ideals. There is controversy concerning the precise notion of equality, the relation of justice and equality (the principles of equality), the material requirements and measure of the ideal of equality (equality of what?), the extension of equality (equality among whom?), and its status within a comprehensive (liberal) theory of justice (the value of equality). This article will discuss each of these issues in turn.

1. Defining the Concept

2.1 formal equality, 2.2 proportional equality, 2.3 moral equality, 2.4 presumption of equality, 3.1 simple equality and objections to equality in general, 3.2 libertarianism, 3.3 utilitarianism, 3.4 equality of welfare, 3.5 equality of resources, 3.6 responsibility and luck-egalitarianism, 3.7 equality of opportunity for welfare or advantage, 3.8 capabilities approaches, 4. relational equality, 5. equality among whom, 6.1. kinds of egalitarianism, 6.2 equality vs. priority or sufficiency, other internet resources, related entries.

‘Equality’ is a contested concept: “People who praise it or disparage it disagree about what they are praising or disparaging” (Dworkin 2000, p. 2). Our first task is therefore to provide a clear definition of equality in the face of widespread misconceptions about its meaning as a political idea. The terms ‘equality’ (Greek: isotes ; Latin: aequitas , aequalitas ; French: égalité ; German Gleichheit ), ‘equal’, and ‘equally’ signify a qualitative relationship. ‘Equality’ (or ‘equal’) signifies correspondence between a group of different objects, persons, processes or circumstances that have the same qualities in at least one respect, but not all respects, i.e., regarding one specific feature, with differences in other features. ‘Equality’ must then be distinguished from ‘identity’, which refers to one and the same object corresponding to itself in all its features. For the same reason, it needs to be distinguished from ‘similarity’ – the concept of merely approximate correspondence (Dann 1975, p. 997; Menne 1962, p. 44 ff.; Westen 1990, pp. 39, 120). Thus, to say that men are equal, for example, is not to say that they are identical. Equality implies similarity rather than ‘sameness’.

Judgements of equality presume a difference between the things compared. According to this definition, the notion of ‘complete’ or ‘absolute’ equality may be seen as problematic because it would violate the presumption of a difference. Two non-identical objects are never completely equal; they are different at least in their spatiotemporal location. If things do not differ they should not be called ‘equal’, but rather, more precisely, ‘identical’, such as the morning and the evening star. Here usage might vary. Some authors do consider absolute qualitative equality admissible as a borderline concept (Tugendhat & Wolf 1983, p. 170).

‘Equality’ can be used in the very same sense both to describe and prescribe, as with ‘thin’: “you are thin” and “you are too thin”. The approach taken to defining the standard of comparison for both descriptive and prescriptive assertions of equality is very important (Oppenheim 1970). In the descriptive case, the common standard is itself descriptive, for example when two people are said to have the same weight. In the prescriptive use, the standard prescribes a norm or rule, for example when it is said people ought to be equal before the law. The standards grounding prescriptive assertions of equality contain at least two components. On the one hand, there is a descriptive component, since the assertions need to contain descriptive criteria, in order to identify those people to which the rule or norm applies. The question of this identification – who belongs to which category? – may itself be normative, as when we ask to whom the U.S. laws apply. On the other hand, the comparative standards contain something normative – a moral or legal rule, such as the U.S. laws – specifying how those falling under the norm are to be treated. Such a rule constitutes the prescriptive component (Westen 1990, chap. 3). Sociological and economic analyses of (in-)equality mainly pose the questions of how inequalities can be determined and measured and what their causes and effects are. In contrast, social and political philosophy is in general concerned mainly with the following questions: what kind of equality, if any, should obtain, and with respect to whom and when ? Such is the case in this article as well.

‘Equality’ and ‘equal’ are incomplete predicates that necessarily generate one question: equal in what respect? (Rae 1980,p. 132 f.) Equality essentially consists of a tripartite relation between two (or several) objects or persons and one (or several) qualities. Two objects A and B are equal in a certain respect if, in that respect, they fall under the same general term. ‘Equality’ denotes the relation between the objects compared. Every comparison presumes a tertium comparationis , a concrete attribute defining the respect in which the equality applies – equality thus referring to a common sharing of this comparison-determining attribute. This relevant comparative standard represents a ‘variable’ (or ‘index’) of the concept of equality that needs to be specified in each particular case (Westen 1990, p. 10); differing conceptions of equality here emerge from one or another descriptive or normative moral standard. There is another source of diversity as well: As Temkin (1986, 1993, 2009) argues, various different standards might be used to measure inequality, with the respect in which people are compared remaining constant. The difference between a general concept and different specific conceptions (Rawls 1971, p. 21 f.) of equality may explain why some people claim ‘equality’ has no unified meaning – or is even devoid of meaning. (Rae 1981, p. 127 f., 132 f.)

For this reason, it helps to think of the idea of equality or inequality, in the context of social justice, not as a single principle, but as a complex group of principles forming the basic core of today’s egalitarianism. Different principles yield different answers. Both equality and inequality are complex and multifaceted concepts (Temkin 1993, chap. 2). In any real historical context, it is clear that no single notion of equality can sweep the field (Rae 1981, p. 132). Many egalitarians concede that much of our discussion of the concept is vague, but they believe there is also a common underlying strain of important moral concerns implicit in it (Williams 1973). Above all, it serves to remind us of our common humanity, despite various differences (cf. 2.3. below). In this sense, egalitarianism is often thought of as a single, coherent normative doctrine that embraces a variety of principles. Following the introduction of different principles and theories of equality, the discussion will return in the last section to the question how best to define egalitarianism and its core value.

2. Principles of Equality and Justice

Equality in its prescriptive usage is closely linked to morality and justice, and distributive justice in particular. Since antiquity equality has been considered a constitutive feature of justice. (On the history of the concept, cf. Albernethy 1959, Benn 1967, Brown 1988, Dann 1975, Thomson 1949.) People and movements throughout history have used the language of justice to contest inequalities. But what kind of role does equality play in a theory of justice? Philosophers have sought to clarify this by defending a variety of principles and conceptions of equality. This section introduces four such principles, ranging from the highly general and uncontroversial to the more specific and controversial. The next section reviews various conceptions of the ‘currency’ of equality. Different interpretations of the role of equality in a theory of justice emerge according to which of the four principles and metrics have been adopted. The first three principles of equality hold generally and primarily for all actions upon others and affecting others, and for their resulting circumstances. From the fourth principle onward, i.e., starting with the presumption of equality, the focus will be mainly on distributive justice and the evaluation of distribution.

When two persons have equal status in at least one normatively relevant respect, they must be treated equally with regard in this respect. This is the generally accepted formal equality principle that Aristotle articulated in reference to Plato: “treat like cases as like” (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , V.3. 1131a10–b15; Politics , III.9.1280 a8–15, III. 12. 1282b18–23). The crucial question is which respects are normatively relevant and which are not. Some authors see this formal principle of equality as a specific application of a rule of rationality: it is irrational, because inconsistent, to treat equal cases unequally without sufficient reasons (Berlin 1955–56). But others claim that what is at stake here is a moral principle of justice, one reflecting the impartial and universalizable nature of moral judgments. On this view, the postulate of formal equality demands more than consistency with one’s subjective preferences: the equal or unequal treatment in question must be justifiable to the relevantly affected parties, and this on the sole basis of a situation’s objective features.

According to Aristotle, there are two kinds of equality, numerical and proportional (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , 1130b–1132b; cf. Plato, Laws , VI.757b–c). A way of treating others, or a distribution arising from it, is equal numerically when it treats all persons as indistinguishable, thus treating them identically or granting them the same quantity of a good per capita. That is not always just. In contrast, a way of treating others or a distribution is proportional or relatively equal when it treats all relevant persons in relation to their due. Just numerical equality is a special case of proportional equality. Numerical equality is only just under special circumstances, namely when persons are equal in the relevant respects so that the relevant proportions are equal. Proportional equality further specifies formal equality; it is the more precise and comprehensive formulation of formal equality. It indicates what produces an adequate equality.

Proportional equality in the treatment and distribution of goods to persons involves at least the following concepts or variables: Two or more persons \((P_1, P_2)\) and two or more allocations of goods to persons \((G)\) and \(X\) and \(Y\) as the quantity in which individuals have the relevant normative quality \(E\). This can be represented as an equation with fractions or as a ratio. If \(P1\) has \(E\) in the amount of \(X\) and if \(P_2\) has \(E\) in the amount \(Y\), then \(P_1\) is due \(G\) in the amount of \(X'\) and \(P_2\) is due \(G\) in the amount of \(Y'\), so that the ratio \(X/Y = X'/Y'\) is valid. (For the formula to be usable, the potentially large variety of factors involved have to be both quantifiable in principle and commensurable, i.e., capable of synthesis into an aggregate value.)

When factors speak for unequal treatment or distribution, because the persons are unequal in relevant respects, the treatment or distribution proportional to these factors is just. Unequal claims to treatment or distribution must be considered proportionally: that is the prerequisite for persons being considered equally.

This principle can also be incorporated into hierarchical, inegalitarian theories. It indicates that equal output is demanded with equal input. Aristocrats, perfectionists, and meritocrats all believe that persons should be assessed according to their differing deserts, understood in the broad sense of fulfillment of some relevant criterion. Reward and punishment, benefits and burdens, should be proportional to such deserts. Since this definition leaves open who is due what, there can be great inequality when it comes to presumed fundamental (natural) rights, deserts, and worth -– this is apparent in both Plato and Aristotle.

Aristotle’s idea of justice as proportional equality contains a fundamental insight. The idea offers a framework for a rational argument between egalitarian and non-egalitarian ideas of justice, its focal point being the question of the basis for an adequate equality (Hinsch 2003). Both sides accept justice as proportional equality. Aristotle’s analysis makes clear that the argument involves those features that decide whether two persons are to be considered equal or unequal in a distributive context.

On the formal level of pure conceptual explication, justice and equality are linked through these formal and proportional principles. Justice cannot be explained without these equality principles, which themselves only receive their normative significance in their role as principles of justice.

Formal and proportional equality is simply a conceptual schema. It needs to be made precise – i.e., its open variables need to be filled out. The formal postulate remains empty as long as it is unclear when, or through what features, two or more persons or cases should be considered equal. All debates over the proper conception of justice – over who is due what – can be understood as controversies over the question of which cases are equal and which unequal (Aristotle, Politics , 1282b 22). For this reason, equality theorists are correct in stressing that the claim that persons are owed equality becomes informative only when one is told what kind of equality they are owed (Nagel 1979; Rae 1981; Sen 1992, p. 13). Every normative theory implies a certain notion of equality. In order to outline their position, egalitarians must thus take account of a specific (egalitarian) conception of equality. To do so, they need to identify substantive principles of equality, which are discussed below.

Until the eighteenth century, it was assumed that human beings are unequal by nature. This postulate collapsed with the advent of the idea of natural right, which assumed a natural order in which all human beings were equal. Against Plato and Aristotle, the classical formula for justice according to which an action is just when it offers each individual his or her due took on a substantively egalitarian meaning in the course of time: everyone deserved the same dignity and respect. This is now the widely held conception of substantive, universal, moral equality. It developed among the Stoics, who emphasized the natural equality of all rational beings, and in early New Testament Christianity, which envisioned that all humans were equal before God, although this principle was not always adhered to in the later history of the church. This important idea was also taken up both in the Talmud and in Islam, where it was grounded in both Greek and Hebraic elements. In the modern period, starting in the seventeenth century, the dominant idea was of natural equality in the tradition of natural law and social contract theory. Hobbes (1651) postulated that in their natural condition, individuals possess equal rights, because over time they have the same capacity to do each other harm. Locke (1690) argued that all human beings have the same natural right to both (self-)ownership and freedom. Rousseau (1755) declared social inequality to be the result of a decline from the natural equality that characterized our harmonious state of nature, a decline catalyzed by the human urge for perfection, property and possessions (Dahrendorf 1962). For Rousseau (1755, 1762), the resulting inequality and rule of violence can only be overcome by binding individual subjectivity to a common civil existence and popular sovereignty. In Kant’s moral philosophy (1785), the categorical imperative formulates the equality postulate of universal human worth. His transcendental and philosophical reflections on autonomy and self-legislation lead to a recognition of the same freedom for all rational beings as the sole principle of human rights (Kant 1797, p. 230). Such Enlightenment ideas stimulated the great modern social movements and revolutions, and were taken up in modern constitutions and declarations of human rights. During the French Revolution, equality, along with freedom and fraternity, became a basis of the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen of 1789.

The principle that holds that human beings, despite their differences, are to be regarded as one another’s equals, is often also called ‘human equality’ or ‘basic equality’ or ‘equal worth’ or ‘human dignity’ (William 1962, Vlastos 1962, Kateb 2014, Waldron 2017, Rosen 2018). Whether these terms are synonyms is a matter of interpretation, but “they cluster together to form a powerful body of principle” (Waldron 2017, p. 3).

This fundamental idea of equal respect for all persons and of the equal worth or equal dignity of all human beings (Vlastos 1962) is widely accepted (Carter 2011, but see also Steinhoff 2015). In a period in which there is not agreement across the members of a complex society to any one metaphysical, religious, or traditional view (Habermas 1983, p. 53, 1992, pp. 39–44), it appears impossible to peacefully reach a general agreement on common political aims without accepting that persons must be treated as equals. As a result, moral equality constitutes the ‘egalitarian plateau’ for all contemporary political theories (Kymlicka 1990, p. 5).

Fundamental equality means that persons are alike in important relevant and specified respects alone, and not that they are all generally the same or can be treated in the same way (Nagel 1991). In a now commonly posed distinction, stemming from Dworkin (1977, p. 227), moral equality can be understood as prescribing treatment of persons as equals, i.e., with equal concern and respect, and not the often implausible principle of providing all persons with equal treatment. Recognizing that human beings are all equally individual does not mean treating them uniformly in any respects other than those in which they clearly have a moral claim to be treated alike.

Disputes arise, of course, concerning what these claims amount to and how they should be resolved. Philosophical debates are concerned with the kind of equal treatment normatively required when we mutually consider ourselves persons with equal dignity. The principle of moral equality is too abstract and needs to be made concrete if we are to arrive at a clear moral standard. Nevertheless, no conception of just equality can be deduced from the notion of moral equality. Rather, we find competing philosophical conceptions of equal treatment serving as interpretations of moral equality. These need to be assessed according to their degree of fidelity to the deeper ideal of moral equality (Kymlicka 1990, p. 44).

Many conceptions of equality operate along procedural lines involving a presumption of equality . More materially concrete, ethical approaches, as described in the next section below, are concerned with distributive criteria – the presumption of equality, in contrast, is a formal, procedural principle of construction located on a higher formal and argumentative level. What is at stake here is the question of the principle with which a material conception of justice should be constructed, particularly once the approaches described above prove inadequate. The presumption of equality is a prima facie principle of equal distribution for all goods politically suited for the process of public distribution. In the domain of political justice, all members of a given community, taken together as a collective body, have to decide centrally on the fair distribution of social goods, as well as on the distribution’s fair realization. Any claim to a particular distribution, including any existing distributive scheme, has to be impartially justified, i.e., no ownership should be recognized without justification. Applied to this political domain, the presumption of equality requires that everyone should get an equal share in the distribution unless certain types of differences are relevant and justify, through universally acceptable reasons, unequal shares. (With different terms and arguments, this principle is conceived as a presumption by Benn & Peters (1959, 111) and by Bedau (1967, 19); as a relevant reasons approach by Williams (1973); as a conception of symmetry by Tugendhat (1993, 374; 1997, chap. 3); as default option by Hinsch (2002, chap. 5); for criticism of the presumption of equality, cf. Westen (1990, chap. 10).) This presumption results in a principle of prima facie equal distribution for all distributable goods. A strict principle of equal distribution is not required, but it is morally necessary to justify impartially any unequal distribution. The burden of proof lies on the side of those who favor any form of unequal distribution. (For a justification of the presumption in favor of equality s. Gosepath 2004, II.8.; Gosepath 2015.)

The presumption of equality provides an elegant procedure for constructing a theory of distributive justice (Gosepath 2004). One has only to analyze what can justify unequal treatment or unequal distribution in different spheres. To put it briefly, the following postulates of equality are at present generally considered morally required.

Strict equality is called for in the legal sphere of civil freedoms, since – putting aside limitation on freedom as punishment – there is no justification for any exceptions. As follows from the principle of formal equality, all citizens must have equal general rights and duties, which are grounded in general laws that apply to all. This is the postulate of legal equality. In addition, the postulate of equal freedom is equally valid: every person should have the same freedom to structure his or her life, and this in the most far-reaching manner possible in a peaceful and appropriate social order.

In the political sphere, the possibilities for political participation should be equally distributed. All citizens have the same claim to participation in forming public opinion, and in the distribution, control, and exercise of political power. This is the postulate – requiring equal opportunity – of equal political power sharing. To ensure equal opportunity, social institutions have to be designed in such a way that persons who are disadvantaged, e.g. have a stutter or a low income, have an equal chance to make their views known and to participate fully in the democratic process.

In the social sphere, equally gifted and motivated citizens must have approximately the same chances to obtain offices and positions, independent of their economic or social class and native endowments. This is the postulate of fair equality of social opportunity. Any unequal outcome must nevertheless result from equality of opportunity, i.e., qualifications alone should be the determining factor, not social background or influences of milieu.

The equality required in the economic sphere is complex, taking account of several positions that – each according to the presumption of equality – justify a turn away from equality. A salient problem here is what constitutes justified exceptions to equal distribution of goods, the main subfield in the debate over adequate conceptions of distributive equality and its currency. The following factors are usually considered eligible for justified unequal treatment: (a) need or differing natural disadvantages (e.g. disabilities); (b) existing rights or claims (e.g. private property); (c) differences in the performance of special services (e.g. desert, efforts, or sacrifices); (d) efficiency; and (e) compensation for direct and indirect or structural discrimination (e.g. affirmative action).

These factors play an essential, albeit varied, role in the following alternative egalitarian theories of distributive justice. These offer different accounts of what should be equalized in the economic sphere. Most can be understood as applications of the presumption of equality (whether they explicitly acknowledge it or not); only a few (like strict equality, libertarianism, and sufficiency) are alternatives to the presumption.

3. Conceptions of Distributive Equality: Equality of What?

Every effort to interpret the concept of equality and to apply the principles of equality mentioned above demands a precise measure of the parameters of equality. We need to know the dimensions within which the striving for equality is morally relevant. What follows is a brief review of the seven most prominent conceptions of distributive equality, each offering a different answer to one question: in the field of distributive justice, what should be equalized, or what should be the parameter or “currency” of equality?

Simple equality, meaning everyone being furnished with the same material level of goods and services, represents a strict position as far as distributive justice is concerned. It is generally rejected as untenable.

Hence, with the possible exception of Babeuf (1796) and Shaw (1928), no prominent author or movement has demanded strict equality. Since egalitarianism has come to be widely associated with the demand for economic equality, and this in turn with communistic or socialistic ideas, it is important to stress that neither communism nor socialism – despite their protest against poverty and exploitation and their demand for social security for all citizens – calls for absolute economic equality. The orthodox Marxist view of economic equality was expounded in the Critique of the Gotha Program (1875). Marx here rejects the idea of legal equality, on three grounds. First, he indicates, equality draws on a limited number of morally relevant perspectives and neglects others, thus having unequal effects. In Marx’s view, the economic structure is the most fundamental basis for the historical development of society, and is thus the point of reference for explaining its features. Second, theories of justice have concentrated excessively on distribution instead of the basic questions of production. Third, a future communist society needs no law and no justice, since social conflicts will have vanished.

As an idea, simple equality fails because of problems that are raised in regards to equality in general. It is useful to review these problems, as they require resolution in any plausible approach to equality.

(i) We need adequate indices for the measurement of the equality of the goods to be distributed. Through what concepts should equality and inequality be understood? It is thus clear that equality of material goods can lead to unequal satisfaction. Money constitutes a typical, though inadequate, index; at the very least, equal opportunity has to be conceived in other terms.

(ii) The time span needs to be indicated for realizing the desired model of equal distribution (McKerlie 1989, Sikora 1989). Should we seek to equalize the goods in question over complete individual lifetimes, or should we seek to ensure that various life segments are as equally provisioned as possible?

(iii) Equality distorts incentives promoting achievement in the economic field, and the administrative costs of redistribution produce wasteful inefficiencies (Okun 1975). Equality and efficiency need to be balanced. Often, Pareto-optimality is demanded in this respect, usually by economists. A social condition is Pareto-optimal or Pareto-efficient when it is not possible to shift to another condition judged better by at least one person and worse by none (Sen 1970, chap. 2, 2*). A widely discussed alternative to the Pareto principle is the Kaldor-Hicks welfare criterion. This stipulates that a rise in social welfare is always present when the benefits accruing through the distribution of value in a society exceed the corresponding costs. A change thus becomes desirable when the winners in such a change could compensate the losers for their losses, and still retain a substantial profit. In contrast to the Pareto-criterion, the Kaldor-Hicks criterion contains a compensation rule (Kaldor 1939). For purposes of economic analysis, such theoretical models of optimal efficiency make a great deal of sense. However, the analysis is always made relative to a starting situation that can itself be unjust and unequal. A society can thus be (close to) Pareto-optimality – i.e., no one can increase his or her material goods or freedoms without diminishing those of someone else – while also displaying enormous inequalities in the distribution of the same goods and freedoms. For this reason, egalitarians claim that it may be necessary to reduce Pareto-optimality for the sake of justice, if there is no more egalitarian distribution that is also Pareto-optimal. In the eyes of their critics, equality of whatever kind should not lead to some people having to make do with less, when this equalizing down does not benefit any of those who are in a worse position.

(iv) Moral objections : A strict and mechanical equal distribution between all individuals does not sufficiently take into account the differences among individuals and their situations. In essence, since individuals desire different things, why should everyone receive the same goods? Intuitively, for example, we can recognize that a sick person has other claims than a healthy person, and furnishing each with the same goods would be mistaken. With simple equality, personal freedoms are unacceptably limited and distinctive individual qualities insufficiently acknowledged; in this way they are in fact unequally regarded. Furthermore, persons not only have a moral right to their own needs being considered, but a right and a duty to take responsibility for their own decisions and the resulting consequences.

Working against the identification of distributive justice with simple equality, a basic postulate of many present-day egalitarians is as follows: human beings are themselves responsible for certain inequalities resulting from their free decisions; aside from minimum aid in emergencies, they deserve no recompense for such inequalities (but cf. relational egalatarians, discussed in Section 4 ). On the other hand, they are due compensation for inequalities that are not the result of self-chosen options. For egalitarians, the world is morally better when equality of life conditions prevail. This is an amorphous ideal demanding further clarification. Why is such equality an ideal, and what precise currency of equality does it involve?

By the same token, most egalitarians do not advocate an equality of outcome, but different kinds of equality of opportunity, due to their emphasis on a pair of morally central points: that individuals are responsible for their decisions, and that the only things to be considered objects of equality are those which serve the real interests of individuals. The opportunities to be equalized between people can be opportunities for well-being (i.e. objective welfare), or for preference satisfaction (i.e., subjective welfare), or for resources. It is not equality of objective or subjective well-being or resources themselves that should be equalized, but an equal opportunity to gain the well-being or resources one aspires to. Such equality depends on their being a realm of options for each individual equal to the options enjoyed by all other persons, in the sense of the same prospects for fulfillment of preferences or the possession of resources. The opportunity must consist of possibilities one can really take advantage of. Equal opportunity prevails when human beings effectively enjoy equal realms of possibility.

(v) Simple equality is very often associated with equality of results (although these are two distinct concepts). However, to strive only for equality of results is problematic. To illustrate the point, let us briefly limit the discussion to a single action and the event or state of affairs resulting from it. Arguably, actions should not be judged solely by the moral quality of their results, as important as this may be. One must also consider the way in which the events or circumstances to be evaluated have come about. Generally speaking, a moral judgement requires not only the assessment of the results of the action in question (the consequentialist aspect) but, first and foremost, the assessment of the intention of the actor (the deontological aspect). The source and its moral quality influence the moral judgement of the results (Pogge 1999, sect. V). For example, if you strike me, your blow will hurt me; the pain I feel may be considered bad in itself, but the moral status of your blow will also depend on whether you were (morally) allowed such a gesture (perhaps through parental status, although that is controversial) or even obliged to execute it (e.g. as a police officer preventing me from doing harm to others), or whether it was in fact prohibited but not prevented. What is true of individual actions (or their omission) has to be true mutatis mutandis of social institutions and circumstances like distributions resulting from collective social actions (or their omission). Social institutions should therefore be assessed not only on the basis of information about how they affect individual quality of life. A society in which people starve on the streets is certainly marked by inequality; nevertheless, its moral quality, i.e., whether the society is just or unjust with regard to this problem, also depends on the suffering’s causes. Does the society allow starvation as an unintended but tolerable side effect of what its members see as a just distributive scheme? Indeed, does it even defend the suffering as a necessary means, as with forms of Social Darwinism? Or has the society taken measures against starvation which have turned out to be insufficient? In the latter case, whether the society has taken such steps for reasons of political morality or efficiency again makes a moral difference. Hence even for egalitarians, equality of results is too narrow and one-sided a focus.