- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

51 The Case Study: What it is and What it Does

John Gerring is Professor of Political Science, Boston University.

- Published: 05 September 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article presents a reconstructed definition of the case study approach to research. This definition emphasizes comparative politics, which has been closely linked to this method since its creation. The article uses this definition as a basis to explore a series of contrasts between cross-case study and case study research. This article attempts to provide better understanding of this persisting methodological debate as a matter of tradeoffs, which may also contribute to destroying the boundaries that have separated these rival genres within the subfield of comparative politics.

Two centuries after Le Play’s pioneering work, the various disciplines of the social sciences continue to produce a vast number of case studies, many of which have entered the pantheon of classic works. Judging by the large volume of recent scholarly output the case study research design plays a central role in anthropology, archeology, business, education, history, medicine, political science, psychology, social work, and sociology (Gerring 2007 a , ch. 1 ). Even in economics and political economy, fields not usually noted for their receptiveness to case-based work, there has been something of a renaissance. Recent studies of economic growth have turned to case studies of unusual countries such as Botswana, Korea, and Mauritius. 1 Debates on the relationship between trade and growth and the IMF and growth have likewise combined cross-national regression evidence with in-depth (quantitativ and qualitative) case analysis ( Srinivasan and Bhagwati 1999 ; Vreeland 2003 ). Work on ethnic politics and ethnic conflict has exploited within-country variation or small-N cross-country comparisons ( Abadie and Gardeazabal 2003 ; Chandra 2004 ; Posner 2004 ). By the standard of praxis, therefore, it would appear that the method of the case study is solidly ensconced, perhaps even thriving. Arguably, we are witnessing a movement away from a variable-centered approach to causality in the social sciences and towards a case-based approach.

Indeed, the statistical analysis of cross-case observational data has been subjected to increasing scrutiny in recent years. It no longer seems self-evident, even to nomothetically inclined scholars, that non-experimental data drawn from nation-states, cities, social movements, civil conflicts, or other complex phenomena should be treated in standard regression formats. The complaints are myriad, and oftreviewed. 2 They include: (a) the problem of arriving at an adequate specification of the causal model, given a plethora of plausible models, and the associated problem of modeling interactions among these covariates; (b) identification problems, which cannot always be corrected by instrumental variable techniques; (c) the problem of “extreme” counterfactuals, i.e. extrapolating or interpolating results from a general model where the extrapolations extend beyond the observable data points; (d) problems posed by influential cases; (e) the arbitrariness of standard significance tests; (f) the misleading precision of point estimates in the context of “curve-fitting” models; (g) the problem of finding an appropriate estimator and modeling temporal autocorrelation in pooled time series; (h) the difficulty of identifying causal mechanisms; and last, but certainly not least, (i) the ubiquitous problem of faulty data drawn from a variety of questionable sources. Most of these difficulties may be understood as the by-product of causal variables that offer limited variation through time and cases that are extremely heterogeneous.

A principal factor driving the general discontent with cross-case observational research is a new-found interest in experimental models of social scientific research. Following the pioneering work of Donald Campbell (1988 ; Cook and Campbell 1979 ) and Donald Rubin (1974) , methodologists have taken a hard look at the regression model and discovered something rather obvious but at the same time crucially important: this research bears only a faint relationship to the true experiment, for all the reasons noted above. The current excitement generated by matching estimators, natural experiments, and field experiments may be understood as a move toward a quasi-experimental, and frequently case-based analysis of causal relations. Arguably, this is because the experimental ideal is often better approximated by a small number of cases that are closely related to one another, or by a single case observed over time, than by a large sample of heterogeneous units.

A third factor militating towards case-based analysis is the development of a series of alternatives to the standard linear/additive model of cross-case analysis, thus establishing a more variegated set of tools to capture the complexity of social behavior (see Brady and Collier 2004 ). Charles Ragin and associates have shown us how to deal with situations where multiple causal paths lead to the same set of outcomes, a series of techniques known as Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) (“Symposium: Qualitative Comparative Analysis” 2004). Andrew Abbott has worked out a method that maps causal sequences across cases, known as optimal sequence matching ( Abbott 2001 ; Abbott and Forrest 1986 ; Abbott and Tsay 2000 ). Bear Braumoeller, Gary Goertz, Jack Levy, and Harvey Starr have defended the importance of necessary-condition arguments in the social sciences, and have shown how these arguments might be analyzed ( Braumoeller and Goertz 2000 ; Goertz 2003 ; Goertz and Levy forthcoming; Goertz and Starr 2003 ). James Fearon, Ned Lebow, Philip Tetlock, and others have explored the role of counterfactual thought experiments in the analysis of individual case histories ( Fearon 1991 ; Lebow 2000 ; Tetlock and Belkin 1996 ). Colin Elman has developed a typological method of analyzing cases ( Elman 2005 ). David Collier, Jack Goldstone, Peter Hall, James Mahoney, and Dietrich Rueschemeyer have worked to revitalize the comparative and comparative-historical methods ( Collier 1993 ; Goldstone 1997 ; Hall 2003 ; Mahoney and Rueschemeyer 2003 ). And scores of researchers have attacked the problem of how to convert the relevant details of a temporally constructed narrative into standardized formats so that cases can be meaningfully compared (Abell 1987 , 2004 ; Abbott 1992 ; Buthe 2002 ; Griffin 1993 ). While not all of these techniques are, strictly speaking, case study techniques—since they sometimes involve a large number of cases—they do move us closer to a case-based understanding of causation insofar as they preserve the texture and detail of individual cases, features that are often lost in large-N cross-case analysis.

A fourth factor concerns the recent marriage of rational choice tools with case study analysis, sometimes referred to as an “analytic narrative” ( Bates et al. 1998 ). Whether the technique is qualitative or quantitative, scholars equipped with economic models are turning, increasingly, to case studies in order to test the theoretical predictions of a general model, investigate causal mechanisms, and/or explain the features of a key case.

Finally, epistemological shifts in recent decades have enhanced the attractiveness of the case study format. The “positivist” model of explanation, which informed work in the social sciences through most of the twentieth century, tended to downplay the importance of causal mechanisms in the analysis of causal relations. Famously, Milton Friedman (1953) argued that the only criterion of a model was to be found in its accurate prediction of outcomes. The verisimilitude of the model, its accurate depiction of reality, was beside the point. In recent years, this explanatory trope has come under challenge from “realists,” who claim (among other things) that causal analysis should pay close attention to causal mechanisms (e.g. Bunge 1997 ; Little 1998 ). Within political science and sociology, the identification of a specific mechanism—a causal pathway—has come to be seen as integral to causal analysis, regardless of whether the model in question is formal or informal or whether the evidence is qualitative or quantitative ( Achen 2002 ; Elster 1998 ; George and Bennett 2005 ; Hedstrom and Swedberg 1998 ). Given this new-found (or at least newly self-conscious) interest in mechanisms, it is not surprising that social scientists would turn to case studies as a mode of causal investigation.

For all the reasons stated above, one might intuit that social science is moving towards a case-based understanding of causal relations. Yet, this movement, insofar as it exists, has scarcely been acknowledged, and would certainly be challenged by many close observers—including some of those cited in the foregoing passages.

The fact is that the case study research design is still viewed by most methodologists with extreme circumspection. A work that focuses its attention on a single example of a broader phenomenon is apt to be described as a “mere” case study, and is often identified with loosely framed and non-generalizable theories, biased case selection, informal and undisciplined research designs, weak empirical leverage (too many variables and too few cases), subjective conclusions, non-replicability, and causal determinism. To some, the term case study is an ambiguous designation covering a multitude of “inferential felonies.” 3

The quasi-mystical qualities associated with the case study persist to this day. In the field of psychology, a gulf separates “scientists” engaged in cross-case research and “practitioners” engaged in clinical research, usually focused on several cases ( Hersen and Barlow 1976 , 21). In the fields of political science and sociology, case study researchers are acknowledged to be on the “soft” side of hard disciplines. And across fields, the persisting case study orientations of anthropology, education, law, social work, and various other fields and subfields relegate them to the non-rigorous, non-systematic, non-scientific, non-positivist end of the academic spectrum.

The methodological status of the case study is still, officially, suspect. Even among its defenders there is confusion over the virtues and vices of this ambiguous research design. Practitioners continue to ply their trade but have difficulty articulating what it is they are doing, methodologically speaking. The case study survives in a curious methodological limbo.

This leads to a paradox: although much of what we know about the empirical world has been generated by case studies and case studies continue to constitute a large proportion of work generated by the social science disciplines, the case study method is poorly understood.

How can we make sense of the profound disjuncture between the acknowledged contributions of this genre to the various disciplines of social science and its maligned status within these disciplines? If case studies are methodologically flawed, why do they persist? Should they be rehabilitated, or suppressed? How fruitful is this style of research?

In this chapter, I provide a reconstructed definition of the case study approach to research with special emphasis on comparative politics, a field that has been closely identified with this method since its birth. Based on this definition, I then explore a series of contrasts between case study and cross-case study research. These contrasts are intended to illuminate the characteristic strengths and weaknesses (“affinities”) of these two research designs, not to vindicate one or the other. The effort of this chapter is to understand this persisting methodological debate as a matter of tradeoffs. Case studies and cross-case studies explore the world in different ways. Yet, properly constituted, there is no reason that case study results cannot be synthesized with results gained from cross-case analysis, and vice versa. My hope, therefore, is that this chapter will contribute to breaking down the boundaries that have separated these rival genres within the subfield of comparative politics.

1 Definitions

The key term of this chapter is, admittedly, a definitional morass. To refer to a work as a “case study” might mean: that its method is qualitative, small-N; that the research is holistic, thick (a more or less comprehensive examination of a phenomenon); that it utilizes a particular type of evidence (e.g. ethnographic, clinical, non-experimental, non-survey based, participant observation, process tracing, historical, textual, or field research); that its method of evidence gathering is naturalistic (a “real-life context”); that the research investigates the properties of a single observation; or that the research investigates the properties of a single phenomenon, instance, or example. Evidently, researchers have many things in mind when they talk about case study research. Confusion is compounded by the existence of a large number of near-synonyms—single unit, single subject, single case, N = 1, case based, case control, case history, case method, case record, case work, clinical research, and so forth. As a result of this profusion of terms and meanings, proponents and opponents of the case study marshal a wide range of arguments but do not seem any closer to agreement than when this debate was first broached several decades ago.

Can we reconstruct this concept in a clearer, more productive fashion? In order to do so we must understand how the key terms—case and case study—are situated within a neighborhood of related terms. In this crowded semantic field, each term is defined in relation to others. And in the context of a specific work or research terrain, they all take their meaning from a specific inference. (The reader should bear in mind that any change in the inference, and the meaning of all the key terms will probably change.) My attempt here will be to provide a single, determinate, definition of these key terms. Of course, researchers may choose to define these terms in many different ways. However, for purposes of methodological discussion it is helpful to enforce a uniform vocabulary.

Let us stipulate that a case connotes a spatially delimited phenomenon (a unit) observed at a single point in time or over some period of time. It comprises the sort of phenomena that an inference attempts to explain. Thus, in a study that attempts to explain certain features of nation-states, cases are comprised of nation-states (across some temporal frame). In a study that attempts to explain the behavior of individuals, individuals comprise the cases. And so forth. Each case may provide a single observation or multiple (within-case) observations.

For students of comparative politics, the archetypal case is the dominant political unit of our time, the nation-state. However, the study of smaller social and political units (regions, cities, villages, communities, social groups, families) or specific institutions (political parties, interest groups, businesses) is equally common in other subfields, and perhaps increasingly so in comparative politics. Whatever the chosen unit, the methodological issues attached to the case study have nothing to do with the size of the individual cases. A case may be created out of any phenomenon so long as it has identifiable boundaries and comprises the primary object of an inference.

Note that the spatial boundaries of a case are often more apparent than its temporal boundaries. We know, more or less, where a country begins and ends, even though we may have difficulty explaining when a country begins and ends. Yet, some temporal boundaries must be assumed. This is particularly important when cases consist of discrete events—crises, revolutions, legislative acts, and so forth—within a single unit. Occasionally, the temporal boundaries of a case are more obvious than its spatial boundaries. This is true when the phenomena under study are eventful but the unit undergoing the event is amorphous. For example, if one is studying terrorist attacks it may not be clear how the spatial unit of analysis should be understood, but the events themselves may be well bounded.

A case study may be understood as the intensive study of a single case for the purpose of understanding a larger class of cases (a population). Case study research may incorporate several cases. However, at a certain point it will no longer be possible to investigate those cases intensively. At the point where the emphasis of a study shifts from the individual case to a sample of cases we shall say that a study is cross-case . Evidently, the distinction between a case study and cross-case study is a continuum. The fewer cases there are, and the more intensively they are studied, the more a work merits the appellation case study. Even so, this proves to be a useful distinction, for much follows from it.

A few additional terms will now be formally defined.

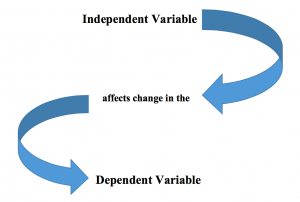

An observation is the most basic element of any empirical endeavor. Conventionally, the number of observations in an analysis is referred to with the letter N . (Confusingly, N may also be used to designate the number of cases in a study, a usage that I shall try to avoid.) A single observation may be understood as containing several dimensions, each of which may be measured (across disparate observations) as a variable. Where the proposition is causal, these may be subdivided into dependent (Y) and independent (X) variables. The dependent variable refers to the outcome of an investigation. The independent variable refers to the explanatory (causal) factor, that which the outcome is supposedly dependent on.

Note that a case may consist of a single observation (N = 1). This would be true, for example, in a cross-sectional analysis of multiple cases. In a case study, however, the case under study always provides more than one observation. These may be constructed diachronically (by observing the case or some subset of within-case units through time) or synchronically (by observing within-case variation at a single point in time).

This is a clue to the fact that case studies and cross-case usually operate at different levels of analysis. The case study is typically focused on within-case variation (if there a cross-case component it is probably secondary). The cross-case study, as the name suggests, is typically focused on cross-case variation (if there is also within-case variation, it is secondary in importance). They have the same object in view—the explanation of a population of cases—but they go about this task differently.

A sample consists of whatever cases are subjected to formal analysis; they are the immediate subject of a study or case study. (Confusingly, the sample may also refer to the observations under study, and will be so used at various points in this narrative. But at present, we treat the sample as consisting of cases.) Technically, one might say that in a case study the sample consists of the case or cases that are subjected to intensive study. However, usually when one uses the term sample one is implying that the number of cases is rather large. Thus, “sample-based work” will be understood as referring to large-N cross-case methods—the opposite of case study work. Again, the only feature distinguishing the case study format from a sample-based (or “cross-case”) research design is the number of cases falling within the sample—one or a few versus many. Case studies, like large-N samples, seek to represent, in all ways relevant to the proposition at hand, a population of cases. A series of case studies might therefore be referred to as a sample if they are relatively brief and relatively numerous; it is a matter of emphasis and of degree. The more case studies one has, the less intensively each one is studied, and the more confident one is in their representativeness (of some broader population), the more likely one is to describe them as a sample rather than a series of case studies. For practical reasons—unless, that is, a study is extraordinarily long—the case study research format is usually limited to a dozen cases or less. A single case is not at all unusual.

The sample rests within a population of cases to which a given proposition refers. The population of an inference is thus equivalent to the breadth or scope of a proposition. (I use the terms proposition , hypothesis , inference , and argument interchangeably.) Note that most samples are not exhaustive; hence the use of the term sample, referring to sampling from a population. Occasionally, however, the sample equals the population of an inference; all potential cases are studied.

For those familiar with the rectangular form of a dataset it may be helpful to conceptualize observations as rows, variables as columns, and cases as either groups of observations or individual observations.

2 What is a Case Study Good For? Case Study versus Cross-case Analysis

I have argued that the case study approach to research is most usefully defined as the intensive study of a single unit or a small number of units (the cases), for the purpose of understanding a larger class of similar units (a population of cases). This is put forth as a minimal definition of the topic. 4 I now proceed to discuss the non -definitional attributes of the case study—attributes that are often, but not invariably, associated with the case study method. These will be understood as methodological affinities flowing from a minimal definition of the concept. 5

The case study research design exhibits characteristic strengths and weaknesses relative to its large-N cross-case cousin. These tradeoffs derive, first of all, from basic research goals such as (1) whether the study is oriented toward hypothesis generating or hypothesis testing, (2) whether internal or external validity is prioritized, (3) whether insight into causal mechanisms or causal effects is more valuable, and (4) whether the scope of the causal inference is deep or broad. These tradeoffs also hinge on the shape of the empirical universe, i.e. (5) whether the population of cases under study is heterogeneous or homogeneous, (6) whether the causal relationship of interest is strong or weak, (7) whether useful variation on key parameters within that population is rare or common, and (8) whether available data are concentrated or dispersed.

Along each of these dimensions, case study research has an affinity for the first factor and cross-case research has an affinity for the second, as summarized in Table 51.1 . To clarify, these tradeoffs represent methodological affinities , not invariant laws. Exceptions can be found to each one. Even so, these general tendencies are often noted in case study research and have been reproduced in multiple disciplines and subdisciplines over the course of many decades.

It should be stressed that each of these tradeoffs carries a ceteris paribus caveat. Case studies are more useful for generating new hypotheses, all other things being equal . The reader must bear in mind that many additional factors also rightly influence a writer’s choice of research design, and they may lean in the other direction. Ceteris are not always paribus. One should not jump to conclusions about the research design appropriate to a given setting without considering the entire range of issues involved—some of which may be more important than others.

3 Hypothesis: Generating versus Testing

Social science research involves a quest for new theories as well as a testing of existing theories; it is comprised of both “conjectures” and “refutations.” 6 Regrettably, social science methodology has focused almost exclusively on the latter. The conjectural element of social science is usually dismissed as a matter of guesswork, inspiration, or luck—a leap of faith, and hence a poor subject for methodological reflection. 7 Yet, it will readily be granted that many works of social science, including most of the acknowledged classics, are seminal rather than definitive. Their classic status derives from the introduction of a new idea or a new perspective that is subsequently subjected to more rigorous (and refutable) analysis. Indeed, it is difficult to devise a program of falsification the first time a new theory is proposed. Path-breaking research, almost by definition, is protean. Subsequent research on that topic tends to be more definitive insofar as its primary task is limited: to verify or falsify a pre-existing hypothesis. Thus, the world of social science may be usefully divided according to the predominant goal undertaken in a given study, either hypothesis generating or hypothesis testing . There are two moments of empirical research, a lightbulb moment and a skeptical moment, each of which is essential to the progress of a discipline. 8

Case studies enjoy a natural advantage in research of an exploratory nature. Several millennia ago, Hippocrates reported what were, arguably, the first case studies ever conducted. They were fourteen in number. 9 Darwin’s insights into the process of human evolution came after his travels to a few select locations, notably Easter Island. Freud’s revolutionary work on human psychology was constructed from a close observation of fewer than a dozen clinical cases. Piaget formulated his theory of human cognitive development while watching his own two children as they passed from childhood to adulthood. Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist theory of human cultures built on the analysis of several North and South American tribes. Douglass North’s neo-institutionalist theory of economic development was constructed largely through a close analysis of a handful of early developing states (primarily England, the Netherlands, and the United States). 10 Many other examples might be cited of seminal ideas that derived from the intensive study of a few key cases.

Evidently, the sheer number of examples of a given phenomenon does not, by itself, produce insight. It may only confuse. How many times did Newton observe apples fall before he recognized the nature of gravity? This is an apocryphal example, but it illustrates a central point: case studies may be more useful than cross-case studies when a subject is being encountered for the first time or is being considered in a fundamentally new way. After reviewing the case study approach to medical research, one researcher finds that although case reports are commonly regarded as the lowest or weakest form of evidence, they are nonetheless understood to comprise “the first line of evidence.” The hallmark of case reporting, according to Jan Vandenbroucke, “is to recognize the unexpected.” This is where discovery begins. 11

The advantages that case studies offer in work of an exploratory nature may also serve as impediments in work of a confirmatory/disconfirmatory nature. Let us briefly explore why this might be so. 12

Traditionally, scientific methodology has been defined by a segregation of conjecture and refutation. One should not be allowed to contaminate the other. 13 Yet, in the real world of social science, inspiration is often associated with perspiration. “Lightbulb” moments arise from a close engagement with the particular facts of a particular case. Inspiration is more likely to occur in the laboratory than in the shower.

The circular quality of conjecture and refutation is particularly apparent in case study research. Charles Ragin notes that case study research is all about “casing”—defining the topic, including the hypothesis(es) of primary interest, the outcome, and the set of cases that offer relevant information vis-à-vis the hypothesis. 14 A study of the French Revolution may be conceptualized as a study of revolution, of social revolution, of revolt, of political violence, and so forth. Each of these topics entails a different population and a different set of causal factors. A good deal of authorial intervention is necessary in the course of defining a case study topic, for there is a great deal of evidentiary leeway. Yet, the “subjectivity” of case study research allows for the generation of a great number of hypotheses, insights that might not be apparent to the cross-case researcher who works with a thinner set of empirical data across a large number of cases and with a more determinate (fixed) definition of cases, variables, and outcomes. It is the very fuzziness of case studies that grants them an advantage in research at the exploratory stage, for the single-case study allows one to test a multitude of hypotheses in a rough-and-ready way. Nor is this an entirely “conjectural” process. The relationships discovered among different elements of a single case have a prima facie causal connection: they are all at the scene of the crime. This is revelatory when one is at an early stage of analysis, for at that point there is no identifiable suspect and the crime itself may be difficult to discern. The fact that A , B , and C are present at the expected times and places (relative to some outcome of interest) is sufficient to establish them as independent variables. Proximal evidence is all that is required. Hence, the common identification of case studies as “plausibility probes,” “pilot studies,” “heuristic studies,” “exploratory” and “theory-building” exercises. 15

A large-N cross-study, by contrast, generally allows for the testing of only a few hypotheses but does so with a somewhat greater degree of confidence, as is appropriate to work whose primary purpose is to test an extant theory. There is less room for authorial intervention because evidence gathered from a cross-case research design can be interpreted in a limited number of ways. It is therefore more reliable. Another way of stating the point is to say that while case studies lean toward Type 1 errors (falsely rejecting the null hypothesis), cross-case studies lean toward Type 2 errors (failing to reject the false null hypothesis). This explains why case studies are more likely to be paradigm generating, while cross-case studies toil in the prosaic but highly structured field of normal science.

I do not mean to suggest that case studies never serve to confirm or disconfirm hypotheses. Evidence drawn from a single case may falsify a necessary or sufficient hypothesis, as discussed below. Additionally, case studies are often useful for the purpose of elucidating causal mechanisms, and this obviously affects the plausibility of an X/Y relationship. However, general theories rarely offer the kind of detailed and determinate predictions on within-case variation that would allow one to reject a hypothesis through pattern matching (without additional cross-case evidence). Theory testing is not the case study’s strong suit. The selection of “crucial” cases is at pains to overcome the fact that the cross-case N is minimal. Thus, one is unlikely to reject a hypothesis, or to consider it definitively proved, on the basis of the study of a single case.

Harry Eckstein himself acknowledges that his argument for case studies as a form of theory confirmation is largely hypothetical. At the time of writing, several decades ago, he could not point to any social science study where a crucial case study had performed the heroic role assigned to it. 16 I suspect that this is still more or less true. Indeed, it is true even of experimental case studies in the natural sciences. “We must recognize,” note Donald Campbell and Julian Stanley,

that continuous, multiple experimentation is more typical of science than once-and-for-all definitive experiments. The experiments we do today, if successful, will need replication and cross-validation at other times under other conditions before they can become an established part of science … [E]ven though we recognize experimentation as the basic language of proof … we should not expect that “crucial experiments” which pit opposing theories will be likely to have clear-cut outcomes. When one finds, for example, that competent observers advocate strongly divergent points of view, it seems likely on a priori grounds that both have observed something valid about the natural situation, and that both represent a part of the truth. The stronger the controversy, the more likely this is. Thus we might expect in such cases an experimental outcome with mixed results, or with the balance of truth varying subtly from experiment to experiment. The more mature focus…avoids crucial experiments and instead studies dimensional relationships and interactions along many degrees of the experimental variables. 17

A single case study is still a single shot—a single example of a larger phenomenon.

The tradeoff between hypothesis generating and hypothesis testing helps us to reconcile the enthusiasm of case study researchers and the skepticism of case study critics. They are both right, for the looseness of case study research is a boon to new conceptualizations just as it is a bane to falsification.

4 Validity: Internal versus External

Questions of validity are often distinguished according to those that are internal to the sample under study and those that are external (i.e. applying to a broader—unstudied—population). Cross-case research is always more representative of the population of interest than case study research, so long as some sensible procedure of case selection is followed (presumably some version of random sampling). Case study research suffers problems of representativeness because it includes, by definition, only a small number of cases of some more general phenomenon. Are the men chosen by Robert Lane typical of white, immigrant, working-class, American males? 18 Is Middletown representative of other cities in America? 19 These sorts of questions forever haunt case study research. This means that case study research is generally weaker with respect to external validity than its cross-case cousin.

The corresponding virtue of case study research is its internal validity. Often, though not invariably, it is easier to establish the veracity of a causal relationship pertaining to a single case (or a small number of cases) than for a larger set of cases. Case study researchers share the bias of experimentalists in this regard: they tend to be more disturbed by threats to within-sample validity than by threats to out-of-sample validity. Thus, it seems appropriate to regard the tradeoff between external and internal validity, like other tradeoffs, as intrinsic to the cross-case/single-case choice of research design.

5 Causal Insight: Causal Mechanisms versus Causal Effects

A third tradeoff concerns the sort of insight into causation that a researcher intends to achieve. Two goals may be usefully distinguished. The first concerns an estimate of the causal effect ; the second concerns the investigation of a causal mechanism (i.e. pathway from X to Y).

By causal effect I refer to two things: (a) the magnitude of a causal relationship (the expected effect on Y of a given change in X across a population of cases) and (b) the relative precision or uncertainty associated with that point estimate. Evidently, it is difficult to arrive at a reliable estimate of causal effects across a population of cases by looking at only a single case or a small number of cases. (The one exception would be an experiment in which a given case can be tested repeatedly, returning to a virgin condition after each test. But here one faces inevitable questions about the representativeness of that much-studied case.) 20 Thus, the estimate of a causal effect is almost always grounded in cross-case evidence.

It is now well established that causal arguments depend not only on measuring causal effects, but also on the identification of a causal mechanism. 21 X must be connected with Y in a plausible fashion; otherwise, it is unclear whether a pattern of covariation is truly causal in nature, or what the causal interaction might be. Moreover, without a clear understanding of the causal pathway(s) at work in a causal relationship it is impossible to accurately specify the model, to identify possible instruments for the regressor of interest (if there are problems of endogeneity), or to interpret the results. 22 Thus, causal mechanisms are presumed in every estimate of a mean (average) causal effect.

In the task of investigating causal mechanisms, cross-case studies are often not so illuminating. It has become a common criticism of large-N cross-national research—e.g. into the causes of growth, democracy, civil war, and other national-level outcomes—that such studies demonstrate correlations between inputs and outputs without clarifying the reasons for those correlations (i.e. clear causal pathways). We learn, for example, that infant mortality is strongly correlated with state failure; 23 but it is quite another matter to interpret this finding, which is consistent with a number of different causal mechanisms. Sudden increases in infant mortality might be the product of famine, of social unrest, of new disease vectors, of government repression, and of countless other factors, some of which might be expected to impact the stability of states, and others of which are more likely to be a result of state instability.

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Introducing Comparative Politics Concepts and Cases in Context

- Stephen Orvis - Hamilton College, USA

- Carol Ann Drogus - Colgate University, USA

- Description

- Assignable Video with Assessment Assignable video (available in Sage Vantage ) is tied to learning objectives and curated exclusively for this text to bring concepts to life.

- LMS Cartridge : Import this title’s instructor resources into your school’s learning management system (LMS) and save time. Don't use an LMS? You can still access all of the same online resources for this title via the password-protected Instructor Resource Site. Learn more .

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

- Editable chapter-specific PowerPoint® slides

- Sample course syllabi

- Lecture notes

- All tables and figures from the textbook

"A solid textbook on the major topics in comparative politics that integrates case studies, most of which are recurring, in each chapter."

"A theoretically-motivated but approachable introduction to comparative politics."

"The graphics in the book are extremely reader-friendly. The language is clear and easy for students to follow. Instructor resources are quite helpful (and a key part of my decision-making). Overall, this is the best comparative politics text for undergrads that I have found. It covers all the important topics in the field and presents them in a way that is accessible to students."

"An excellent resource for the political scientist who is teaching comparative politics for the first time."

"Orvis and Drogus have authored a comprehensive and up-to-date introduction to comparative politics which will engage today's undergraduates."

"In depth case studies and analysis of particular topics in comparative politics"

"This is a great introductory comparative politics text for both majors and non-majors. The material is accessible for non-discipline students, and easily lends itself to connections with other academic disciplines. The structure of the content is flexible enough to allow for the integration of current events."

What a fantastic book! It has great case studies that are very contemporary and lots of relevant discussions on things my students are really interested in, like political protest and identity politics. All the resources, like slides and lecture notes, are great, and I'm able to use those quite effectively in my classes. This book has nailed what comparative politics is all about.

- The new edition is available in Sage Vantage , an intuitive learning platform that integrates quality Sage textbook content with assignable multimedia activities and auto-graded assessments to drive student engagement and ensure accountability. Unparalleled in its ease of use and built for dynamic teaching and learning, Vantage offers customizable LMS integration and best-in-class support. Learn more .

- Chapter 6 includes an expanded section on the global rise of populism.

- A new case study in chapter 7 looks at Black Lives Matter as a social movement.

- Chapter 10 has been substantially reorganized to clarify the debate over globalization and varieties of capitalism .

- Effects of the global coronavirus pandemic are incorporated throughout the book.

- Throughout the book, case studies have been updated to include the most recent political developments .

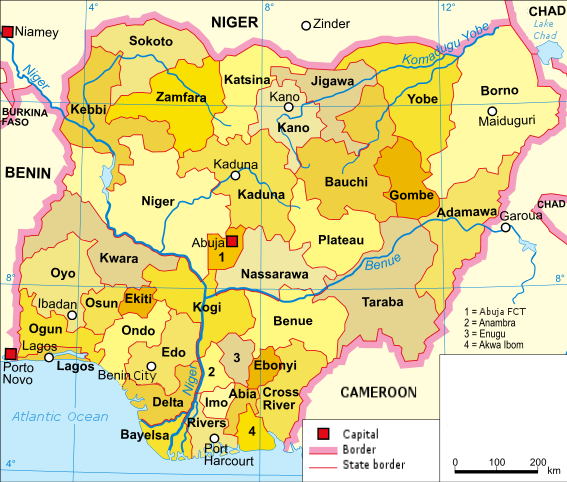

- Core country case studies are introduced in Chapter 1 and then revisited throughout the book, allowing instructors to tie multiple case studies to one theory or concept. The case studies include coverage of Brazil, China, Germany, Japan, India, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Each case includes a Case Synopsis at the beginning to improve student comprehension of the material.

- In Context fact boxes put case studies and data into regional context.

- Critical Inquiry features in every chapter highlight methodological issues in comparative politics, providing a gateway for empirical study and analysis.

- A Country and Concept table in each chapter displays key indicators for core countries to offer at-a-glance context and comparison.

- More than a hundred full color tables, figures, and maps help students visualize comparative data and better understand concepts.

- Chapter-opening key questions, a marginal glossary, as well as end-of-chapter lists of key concepts , works cited, suggested reading, and web resources help students review, research, and study.

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Chapter 1. Introduction

Chapter 2. The Modern State

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

An Open Education Resource Textbook

Welcome to the official home of Introduction to Comparative Government and Politics, a new Open Education Resources (OER) textbook, written by Dr. Dino Bozonelos, Dr. Julia Wendt, Dr. Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Dr. Masahiro Omae, Dr. Josh Franco, Dr. Byran Martin, and Stefan Veldhuis.

Introduction to Comparative Government and Politics is the first open educational resource (OER) on the topic of comparative politics, and the second OER textbook in political science funded by ASCCC OERI, in what we hope will become a complete library for the discipline. This textbook aligns with the C-ID Course Descriptor for Introduction to Comparative Government and Politics in content and objectives.

With chapter contributions from Dr. Julia Wendt at Victor Valley College, Dr. Charlotte Lee at Berkeley City College, Jessica Scarffe at Allan Hancock College, Dr. Masahiro Omae at San Diego City College, Dr. Josue Franco at Cuyamaca College, Stefan Veldhuis at Long Beach City College, Dr. Byran Martin at Houston Community College, and myself, the purpose of this open education resource is to provide students interested in or majoring in political science a useful textbook in comparative politics, one of the major subfields in the discipline.

It is organized thematically, with each chapter accompanied by a case study or a comparative study, one of the main methodological tools used in comparative politics. By contextualizing the concepts, we hope to help students learn the comparative method, which to this day remains one of the most important methodological tools for all researchers.

I chose to pursue this project as I felt that an OER textbook in comparative politics would otherwise never have been written. After many years of teaching at a community college, my colleagues and I realized a need existed for a zero-cost textbook. With the rising costs of education and textbooks, community college students may be deterred from exploring political science courses. I believe that this is where the next elected leader, policymaker or military strategist needs to come from. This is a grassroots textbook, written with these and future community college students in mind.

This open education resource is free to students and faculty and available under the Creative Commons – Attribution – Noncommercial (CC BY-NC) license. We hope that it will encourage them further their studies in comparative politics and in political science.

Dino Bozonelos, Ph.D. May 2022

- Faculty of Arts and Sciences

- FAS Scholarly Articles

- Communities & Collections

- By Issue Date

- FAS Department

- Quick submit

- Waiver Generator

- DASH Stories

- Accessibility

- COVID-related Research

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- By Collections

- By Departments

Show simple item record

Evidence Based Public Policy Making: A Comparative Case Study Analysis

Files in this item.

This item appears in the following Collection(s)

- FAS Scholarly Articles [18295]

POLSC221: Introduction to Comparative Politics

POLSC221 Study Guide

Unit 7: comparative case studies, 7a. describe and explain the political economy and development in selected regions and countries.

- How did the countries in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia develop politically and economically?

- How have the economic challenges each country faced influenced the political and economic development of each respective country and region?

- How did their respective political structures impact their economic development? For example, why do you think states in Asia and the Middle East have been more successful in managing economic development, than those in Africa and Latin America?

- What are some of the broad regional patterns that have promoted economic development?

- How do these patterns differ among the countries in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia?

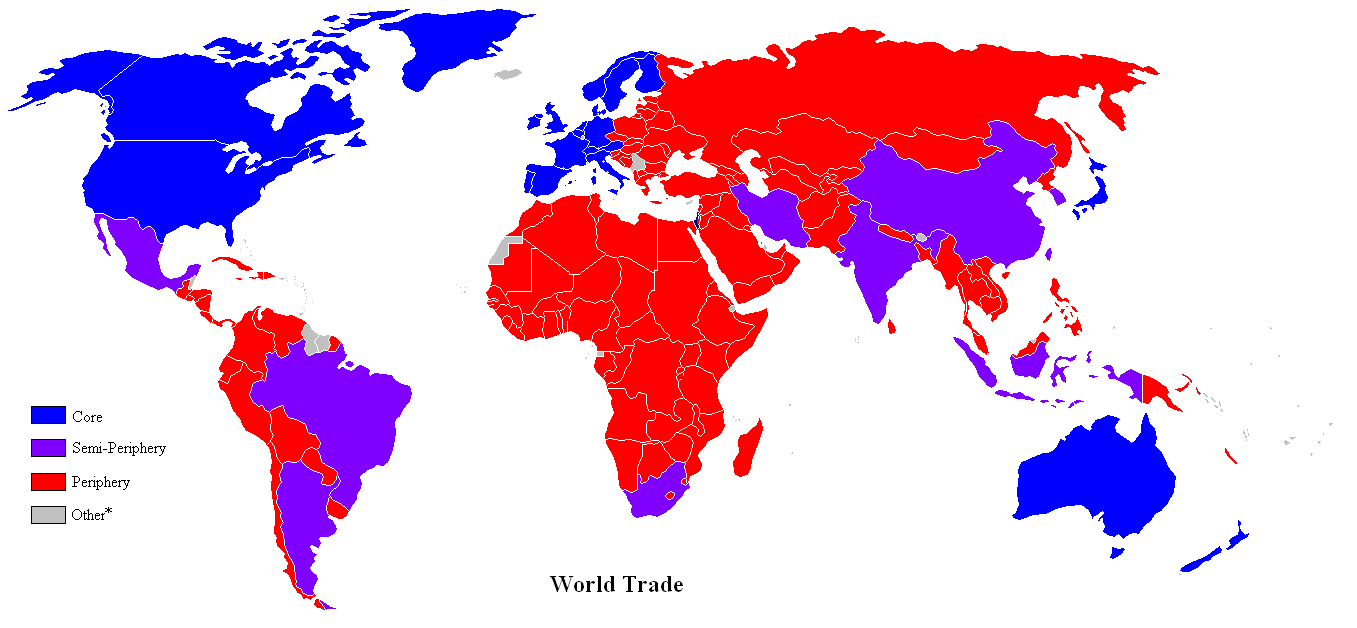

Comparing and contrasting one country's political economy and development with another involves examining the evolution of each nation's respective political system, economic development, international trade, and the internal distribution of its national income and wealth.

To review, see Comparative Case Studies .

7b. Identify and explain political challenges and changing agendas in selected regions and countries

- How have their past colonial experiences impacted political and economic development in the states that make up Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia?

- How has an abundance of economically valuable natural resources brought benefits and disadvantages to the states in these regions?

- How has the persistent robust trade in illegal drugs impacted the politics of the states in these regions?

- How have economic programs, such as cash transfers and microfinancing , benefited the people who live in the states in these regions?

- How have international treaties, such as NAFTA, impacted political and economic development in Mexico, the United States, and Canada, and the other states in these regions?

Politicians in many developing states face the challenge of managing past economic and political legacies as they navigate a world that is experiencing rapid change and growth, such as new technological infrastructure, population growth, and economic opportunities. Some countries, such as those in East Asia and the Middle East have experienced rapid economic growth, while others, such as those in Africa and Latin America, continue to struggle with political conflict, violence, and economic inequalities.

Unit 7 Vocabulary

- Cash transfers

- Colonialism

- Foreign direct investment

- Import substitution industrialization

- Microfinance

- North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.4: Comparative Case Study - Barometers Around the World

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 135877

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Remember the definition of a barometer

- Analyze at least two different barometers

- Evaluate the similarities and differences between two or more barometers

Introduction

Recall from the beginning of the chapter that comparative public opinion is the research and analysis of public opinion across two or more countries.The case study for this chapter is a comparison of global or regional public opinion surveys, also called barometers. Also remember from Chapter Two, that cases in comparative politics are mostly countries. Here is a comparative case study where the cases are not countries, but instead barometers.

What is a barometer?

A barometer is typically defined as “an instrument for determining the pressure of the atmosphere and hence for assisting in forecasting weather and for determining altitude.” However, when political scientists use the term barometer, we are referring to a survey of questions that are asked of individuals in a particular country or region of the world, to gauge their opinions on political ideas, institutions, and actors.

Barometers Around the World

Eight well known barometers include: Afrobarometer, Arab Barometer, Asian Barometer, Eurasia Barometer, Latino Barometer, Comparative National Elections Project, AmericasBarometer, and World Values Survey. Below is a table that summarizes the year, geographic coverage, and website for each of these barometers.

According to its website, the Afrobarometer “is a non-partisan, pan-African research institution conducting public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, the economy and society in 30+ countries repeated on a regular cycle. They are the world’s leading source of high-quality data on what Africans are thinking. Additionally, they are the world’s leading research project on issues that affect ordinary African men and women. Afrobarometer collects and publishes high-quality, reliable statistical data on Africa which is freely available to the public.”

The Afrobarometer conducts rounds of questionnaires in specific countries across the African continent. Since 2000, there have been 8 rounds with a total of 171 questionnaires. In the latest round, 34 surveys were asked in 34 different countries. Each country’s question was in one of four languages: Arabic, English, French, or Portuguese.

One example was the questionnaire for the country of Botswana , located in the southern part of the African continent. The survey was conducted in 2019, written in English, and included over 100 questions ranging from personal demographics, views of the economy, politics and recent elections, the media, taxes, corruption, and how the government was handling different matters. To explore the results of the survey, please visit Summary of results: Afrobarometer Round 8 survey in Botswana in 2019 .

Arab Barometer

Arab Barometer, according to its website, “is a nonpartisan research network that provides insight into the social, political, and economic attitudes and values of ordinary citizens across the Arab world. They have been conducting high quality and reliable public opinion surveys in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) since 2006. Arab Barometer is the longest-standing and the largest repository of publicly available data on the views of men and women in the MENA region. Their findings give a voice to the needs and concerns of Arab publics.”

From July 2020 to April 2021, the Arab Barometer conducted its sixth wave of surveying across the Middle East North African region, and specifically the countries of Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Iraq. This wave consisted of 3 parts from July-October 2020, October 2020, and March-April 2021. The Part 1 questionnaire featured 8 sections of questions: Core Demographics; Lebanon: Beirut Port Explosion; COVID-19; State of the Economy; Trust and Government Performance; Media, Religion, and Culture; International Relations; and Demographics. There are approximately 58 questions across these 8 sections. To explore the results of this wave for the country of Lebanon, read the Lebanon Country Report .

Asian Barometer