Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Hypertension

Target audience and health literacy.

Improvements in the quality of life and access to healthcare worldwide are associated with greater longevity – for instance, in some countries, life expectancy may amount up to 80 years and more. While a longer life is a positive tendency, it gives rise to an increase in age-related health disorders which contributes to the global and national burden of disease. One of the most prevalent health conditions associated with age is hypertension. According to a report by World Health Organization, almost half of the people over the age of 25 suffered from hypertension at least once in their lives (Kishore, Gupta, Kohli, & Kumar, 2016). This essay will provide an informative summary of symptoms, causes, and treatment of hypertension.

Hypertension is a health condition that is characterized by high blood pressure (HBP). For blood pressure to be considered abnormally high, the readings should consistently display 140 over 90 or higher. It is essential to understand that a single occasion of HBP due to some factors be it stress or environmental conditions does not mean that a patient suffers from hypertension. For a proper diagnosis, a patient showing typical symptoms and making complaints should make regular appointments at his or her GP’s and measure blood pressure at home as well.

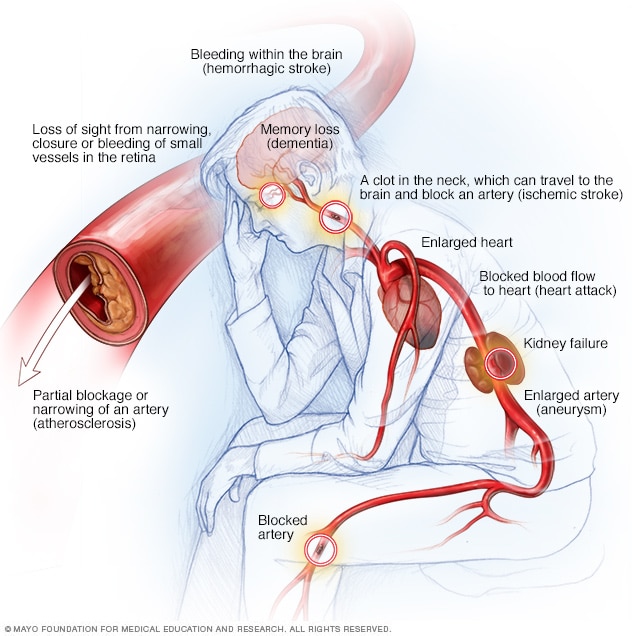

The symptoms of hypertension can be very mild, and the condition may go unnoticed for years on end. The signs may vary from patient to patient, but typically, if symptoms are present, they include severe headaches, chest ache, difficulty breathing, the feeling of weakness, and fatigue. The main reason why it is imperative to pay attention to symptoms and make an early diagnosis is the extensive list of possible complications. When neglected and untreated, HBP can lead to heart attack or a stroke, aneurysm, heart failure, and even dementia; in some cases, HBP can be lethal.

The primary risk factor for HBP is old age since blood vessels lose their elasticity over time (Buford, 2016). Among other factors is the presence of the condition in a patient’s close relatives. Other underlying causes are associated with a patient’s lifestyle: drinking alcohol in excess, smoking tobacco, and not being physically active (Leung et al., 2017). If diagnosed with HBP, a patient is usually prescribed beta-blockers, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (Weber et al., 2014). However, taking medication alone does not solve the problem, and a patient should revise his or her daily habits and make improvements.

A study by McNaughton et al. (2014) showed that the lack of medical knowledge was associated with elevated blood pressure especially in those patients who had not been officially diagnosed with HBP. Hence, it is critical that a patient takes charge of his or her health and takes measures to prevent or control the condition and improve their overall health literacy. The target audience of the health brochure on hypertension would consist of patients over 45 years – a typical age of onset.

It is also reasonable to spread the brochure among patients belonging to risk groups – for instance, among those suffering from obesity or diabetes. Even though hypertension is associated with mature or old age, as per the report by the World Health Organization, young people might also be susceptible to developing HBP. Thus, a health practitioner could promote better dietary habits and a fitness routine to help to eliminate risks.

Over the last few decades, heightened blood pressure has become a significant public health challenge as it was found to be one of the risks of cardiovascular mortality. Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is alarmingly prevalent among individuals over the age of 45. While health practitioners are trained to address the issue, the patients should gain control of their lifestyle as well. An informative health brochure with links to credible sources can help patients make well-informed health decisions.

Buford, T. W. (2016). Hypertension and aging . Ageing Research Reviews , 26 , 96-111. Web.

Kishore, J., Gupta, N., Kohli, C., & Kumar, N. (2016). Prevalence of hypertension and determination of its risk factors in rural Delhi. International Journal of Hypertension , 2016, 7962595.

Leung, A. A., Daskalopoulou, S. S., Dasgupta, K., McBrien, K., Butalia, S., Zarnke, K. B.,… & Gelfer, M. (2017). Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults . Canadian Journal of Cardiology , 33 (5), 557-576. Web.

McNaughton, C. D., Kripalani, S., Cawthon, C., Mion, L. C., Wallston, K. A., & Roumie, C. L. (2014). Association of health literacy with elevated blood pressure: A cohort study of hospitalized patients . Medical Care , 52 (4), 346-353. Web.

Weber, M. A., Schiffrin, E. L., White, W. B., Mann, S., Lindholm, L. H., Kenerson, J. G.,… & Cohen, D. L. (2014). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: A statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension . The Journal of Clinical Hypertension , 16 (1), 14-26. Web.

- What is Hypertension?

- The Hypertension Condition Analysis

- Creating Awareness Through Education: Hypertension

- Lifestyle Habits and Cardiac Changes

- Disorders of the Veins and Arteries

- Heart Attack: Health Information Patient Handout

- Cardiovascular Disorders: Pharmacotherapy

- Core Measures of Acute Myocardial Infarction

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 8). Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension. https://ivypanda.com/essays/summary-of-symptoms-causes-and-treatment-of-hypertension/

"Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension." IvyPanda , 8 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/summary-of-symptoms-causes-and-treatment-of-hypertension/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension'. 8 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension." July 8, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/summary-of-symptoms-causes-and-treatment-of-hypertension/.

1. IvyPanda . "Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension." July 8, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/summary-of-symptoms-causes-and-treatment-of-hypertension/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Summary of Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment of Hypertension." July 8, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/summary-of-symptoms-causes-and-treatment-of-hypertension/.

Hypertension: Introduction, Types, Causes, and Complications

Cite this chapter.

- Yoshihiro Kokubo MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO 4 ,

- Yoshio Iwashima MD, PhD, FAHA 5 &

- Kei Kamide MD, PhD, FAHA 6

8739 Accesses

4 Citations

Hypertension remains one of the most significant causes of mortality worldwide. It is preventable by medication and lifestyle modification. Office blood pressure (BP), out-of-office BP measurement with ambulatory BP monitoring, and self-BP measurement at home are reliable and important data for assessing hypertension. Primary hypertension can be defined as an elevated BP of unknown cause due to cardiovascular risk factors resulting from changes in environmental and lifestyle factors. Another type, secondary hypertension, is caused by various toxicities, iatrogenic disease, and congenital diseases. Complications of hypertension are the clinical outcomes of persistently high BP that result in cardiovascular disease (CVD), atherosclerosis, kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, preeclampsia, erectile dysfunction, and eye disease. Treatment strategies for hypertension consist of lifestyle modifications (which include a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat food or fish with a reduced content of saturated and total fat, salt restriction, appropriate body weight, regular exercise, moderate alcohol consumption, and smoking cessation) and drug therapies, although these vary somewhat according to different published hypertension treatment guidelines.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Sega R, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Cesana G, Corrao G, Grassi G, et al. Prognostic value of ambulatory and home blood pressures compared with office blood pressure in the general population: follow-up results from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate e Loro Associazioni (PAMELA) study. Circulation. 2005;111:1777–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Hypertension: The Clinical Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults: Update of Clinical Guidelines 18 and 34 [Internet]. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2011 Aug. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK83274 . PubMed PMID: 22855971.

Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–357.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:3–15.

Go AS, Bauman MA, Coleman King SM, Fonarow GC, Lawrence W, Williams KA, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension. 2014;63:878–85.

Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, Hasebe N, Higaki J, Horiuchi M, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37:253–387.

Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Kannel WB, Levy D. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham heart study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358:1682–6.

Kokubo Y, Nakamura S, Watanabe M, Kamide K, Kawano Y, Kawanishi K, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with incident hypertension according to blood pressure categories in non-hypertensive population in the Suita study: an Urban cohort study. Hypertension. 2011;58:E132.

Google Scholar

Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10.

Kokubo Y. Traditional risk factor management for stroke: a never-ending challenge for health behaviors of diet and physical activity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:11–7.

Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, Braun LT, Bravata DM, Chaturvedi S, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3754–832.

European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee, ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457–507.

Article Google Scholar

Guild SJ, McBryde FD, Malpas SC, Barrett CJ. High dietary salt and angiotensin II chronically increase renal sympathetic nerve activity: a direct telemetric study. Hypertension. 2012;59:614–20.

Mu S, Shimosawa T, Ogura S, Wang H, Uetake Y, Kawakami-Mori F, et al. Epigenetic modulation of the renal beta-adrenergic-WNK4 pathway in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nat Med. 2011;17:573–80.

WHO. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva, World Health Organization (WHO), 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK133309/pdf/TOC.pdf .

Kokubo Y. Prevention of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases: a comparison of lifestyle factors in westerners and east Asians. Hypertension. 2014;63:655–60.

Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Willett WC, et al. A prospective study of nutritional factors and hypertension among US men. Circulation. 1992;86:1475–84.

Ascherio A, Hennekens C, Willett WC, Sacks F, Rosner B, Manson J, et al. Prospective study of nutritional factors, blood pressure, and hypertension among US women. Hypertension. 1996;27:1065–72.

Stamler J, Liu K, Ruth KJ, Pryer J, Greenland P. Eight-year blood pressure change in middle-aged men: relationship to multiple nutrients. Hypertension. 2002;39:1000–6.

Miura K, Greenland P, Stamler J, Liu K, Daviglus ML, Nakagawa H. Relation of vegetable, fruit, and meat intake to 7-year blood pressure change in middle-aged men: the Chicago Western Electric study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:572–80.

Tsubota-Utsugi M, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Kurimoto A, Suzuki K, et al. High fruit intake is associated with a lower risk of future hypertension determined by home blood pressure measurement: the OHASAMA study. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:164–71.

Ueshima H, Stamler J, Elliott P, Chan Q, Brown IJ, Carnethon MR, et al. Food omega-3 fatty acid intake of individuals (total, linolenic acid, long-chain) and their blood pressure: INTERMAP study. Hypertension. 2007;50:313–9.

Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ, Grobbee DE, Donders AR, Kok FJ. Blood pressure response to fish oil supplementation: metaregression analysis of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1493–9.

Kromhout D, Bosschieter EB, de Lezenne CC. The inverse relation between fish consumption and 20-year mortality from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1205–9.

Yamori Y. Food factors for atherosclerosis prevention: Asian perspective derived from analyses of worldwide dietary biomarkers. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2006;11:94–8.

PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM. Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2003;42:878–84.

Hamer M, Chida Y. Active commuting and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2008;46:9–13.

Hayashi T, Tsumura K, Suematsu C, Okada K, Fujii S, Endo G. Walking to work and the risk for hypertension in men: the Osaka Health Survey. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:21–6.

Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, Gienger AL, Lin N, Lewis R, et al. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:2296–304.

Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, Campbell F, Beyer FR, Cook JV, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2006;24:215–33.

Groppelli A, Giorgi DM, Omboni S, Parati G, Mancia G. Persistent blood pressure increase induced by heavy smoking. J Hypertens. 1992;10:495–9.

Makris TK, Thomopoulos C, Papadopoulos DP, Bratsas A, Papazachou O, Massias S, et al. Association of passive smoking with masked hypertension in clinically normotensive nonsmokers. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:853–9.

Zanchetti A. Intermediate endpoints for atherosclerosis in hypertension. Blood Press Suppl. 1997;2:97–102.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Iwashima Y, Kokubo Y, Ono T, Yoshimuta Y, Kida M, Kosaka T, et al. Additive interaction of oral health disorders on risk of hypertension in a Japanese urban population: the Suita study. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:710–9.

Zelkha SA, Freilich RW, Amar S. Periodontal innate immune mechanisms relevant to atherosclerosis and obesity. Periodontol 2000. 2010;54:207–21.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Tsioufis C, Kasiakogias A, Thomopoulos C, Stefanadis C. Periodontitis and blood pressure: the concept of dental hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:1–9.

Kubo M, Hata J, Doi Y, Tanizaki Y, Iida M, Kiyohara Y. Secular trends in the incidence of and risk factors for ischemic stroke and its subtypes in Japanese population. Circulation. 2008;118:2672–8.

Sjol A, Thomsen KK, Schroll M. Secular trends in blood pressure levels in Denmark 1964–1991. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:614–22.

Kokubo Y, Kamide K, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Kawanishi K, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita study. Hypertension. 2008;52:652–9.

Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke. 2004;35:776–85.

Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Tousoulis D, Stefanadis C. Effects of antihypertensive treatment in patients over 65 years of age: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. Heart. 2014;100:317–23.

Asayama K, Thijs L, Brguljan-Hitij J, Niiranen TJ, Hozawa A, Boggia J, et al. Risk stratification by self-measured home blood pressure across categories of conventional blood pressure: a participant-level meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001591.

Bussemaker E, Hillebrand U, Hausberg M, Pavenstadt H, Oberleithner H. Pathogenesis of hypertension: interactions among sodium, potassium, and aldosterone. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1111–20.

Kokubo Y, Nakamura S, Okamura T, Yoshimasa Y, Makino H, Watanabe M, et al. Relationship between blood pressure category and incidence of stroke and myocardial infarction in an urban Japanese population with and without chronic kidney disease: the Suita study. Stroke. 2009;40:2674–9.

Kokubo Y. The mutual exacerbation of decreased kidney function and hypertension. J Hypertens. 2012;30:468–9.

Kokubo Y, Okamura T, Watanabe M, Higashiyama A, Ono Y, Miyamoto Y, et al. The combined impact of blood pressure category and glucose abnormality on the incidence of cardiovascular diseases in a Japanese urban cohort: the Suita study. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:1238–43.

Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–32.

Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LC. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301.

Aranda P, Ruilope LM, Calvo C, Luque M, Coca A, Gil de Miguel A. Erectile dysfunction in essential arterial hypertension and effects of sildenafil: results of a Spanish national study. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:139–45.

Sharp SI, Aarsland D, Day S, Sonnesyn H, Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group, Ballard C. Hypertension is a potential risk factor for vascular dementia: systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:661–9.

Ninomiya T, Ohara T, Hirakawa Y, Yoshida D, Doi Y, Hata J, et al. Midlife and late-life blood pressure and dementia in Japanese elderly: the Hisayama study. Hypertension. 2011;58:22–8.

Thukkani AK, Bhatt DL. Renal denervation therapy for hypertension. Circulation. 2013;128:2251–4.

Myat A, Redwood SR, Qureshi AC, Thackray S, Cleland JG, Bhatt DL, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation therapy for resistant hypertension: a contemporary synopsis and future implications. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:184–97.

Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, D’Agostino R, Flack JM, Katzen BT, et al. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393–401.

Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–62.

Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1998;317:703–13.

Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, et al. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:877–84.

Bangalore S, Kumar S, Lobach I, Messerli FH. Blood pressure targets in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus/impaired fasting glucose: observations from traditional and Bayesian random-effects meta-analyses of randomized trials. Circulation. 2011;123:2799–810, 2799 p following 2810.

Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, D’Agostino Sr R, Ohman EM, Rother J, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2007;297:1197–206.

Perry Jr HM, Davis BR, Price TR, Applegate WB, Fields WS, Guralnik JM, et al. Effect of treating isolated systolic hypertension on the risk of developing various types and subtypes of stroke: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 2000;284:465–71.

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhager WH, et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350:757–64.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887–98.

American DA. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37 Suppl 1:S14–80.

Hollenberg NK, Price DA, Fisher ND, Lansang MC, Perkins B, Gordon MS, et al. Glomerular hemodynamics and the renin-angiotensin system in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int. 2003;63:172–8.

Mezzano S, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Ardiles LG, Flores CA, Aros CA, et al. Renin-angiotensin system activation and interstitial inflammation in human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003:(86);S64–70.

Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005;366:1545–53.

Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Shi V, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–28.

Bakris GL, Toto RD, McCullough PA, Rocha R, Purkayastha D, Davis P, et al. Effects of different ACE inhibitor combinations on albuminuria: results of the GUARD study. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1303–9.

ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, Dyal L, Copland I, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–59.

Download references

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan (Nos. 25293147 and 26670320), the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H26-Junkankitou [Seisaku]-Ippan-001), the Rice Health Database Maintenance industry, Tojuro Iijima Memorial Food Science, the Intramural Research Fund of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (22-4-5).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Preventive Cardiology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, 5-7-1, Fujishiro-dai, Suita, Osaka, 565-8565, Japan

Yoshihiro Kokubo MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO

Divisions of Hypertension and Nephrology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, 5-7-1, Fujishiro-dai, Suita, Osaka, 565-8565, Japan

Yoshio Iwashima MD, PhD, FAHA

Division of Health Science, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, Osaka, Japan

Kei Kamide MD, PhD, FAHA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yoshihiro Kokubo MD, PhD, FAHA, FACC, FESC, FESO .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Pharmacology Unit, AIMST University, Bedong, Malaysia

Pitchai Balakumar

Khin Maung-U

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Kokubo, Y., Iwashima, Y., Kamide, K. (2015). Hypertension: Introduction, Types, Causes, and Complications. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Maung-U, K. (eds) Pathophysiology and Pharmacotherapy of Cardiovascular Disease. Adis, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15961-4_30

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15961-4_30

Publisher Name : Adis, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-15960-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-15961-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Taking a summer road trip? Enter for a chance to win $4,000 cash with AARP Rewards.

AARP daily Crossword Puzzle

Hotels with AARP discounts

Life Insurance

AARP Dental Insurance Plans

AARP MEMBERSHIP

AARP Membership — $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products, hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

- right_container

Work & Jobs

Social Security

AARP en Español

- Membership & Benefits

AARP Rewards

- AARP Rewards %{points}%

Conditions & Treatments

Drugs & Supplements

Health Care & Coverage

Health Benefits

Staying Fit

Your Personalized Guide to Fitness

Get Happier

Creating Social Connections

Brain Health Resources

Tools and Explainers on Brain Health

Your Health

8 Major Health Risks for People 50+

Scams & Fraud

Personal Finance

Money Benefits

View and Report Scams in Your Area

AARP Foundation Tax-Aide

Free Tax Preparation Assistance

AARP Money Map

Get Your Finances Back on Track

How to Protect What You Collect

Small Business

Age Discrimination

Flexible Work

Freelance Jobs You Can Do From Home

AARP Skills Builder

Online Courses to Boost Your Career

31 Great Ways to Boost Your Career

ON-DEMAND WEBINARS

Tips to Enhance Your Job Search

Get More out of Your Benefits

When to Start Taking Social Security

10 Top Social Security FAQs

Social Security Benefits Calculator

Medicare Made Easy

Original vs. Medicare Advantage

Enrollment Guide

Step-by-Step Tool for First-Timers

Prescription Drugs

9 Biggest Changes Under New Rx Law

Medicare FAQs

Quick Answers to Your Top Questions

Care at Home

Financial & Legal

Life Balance

LONG-TERM CARE

Understanding Basics of LTC Insurance

State Guides

Assistance and Services in Your Area

Prepare to Care Guides

How to Develop a Caregiving Plan

End of Life

How to Cope With Grief, Loss

Recently Played

Word & Trivia

Atari® & Retro

Members Only

Staying Sharp

Mobile Apps

More About Games

Right Again! Trivia

Right Again! Trivia – Sports

Atari® Video Games

Throwback Thursday Crossword

Travel Tips

Vacation Ideas

Destinations

Travel Benefits

Outdoor Vacation Ideas

Camping Vacations

Plan Ahead for Summer Travel

AARP National Park Guide

Discover Canyonlands National Park

History & Culture

8 Amazing American Pilgrimages

Entertainment & Style

Family & Relationships

Personal Tech

Home & Living

Celebrities

Beauty & Style

Movies for Grownups

Summer Movie Preview

Jon Bon Jovi’s Long Journey Back

Looking Back

50 World Changers Turning 50

Sex & Dating

Spice Up Your Love Life

Friends & Family

How to Host a Fabulous Dessert Party

Home Technology

Caregiver’s Guide to Smart Home Tech

Virtual Community Center

Join Free Tech Help Events

Create a Hygge Haven

Soups to Comfort Your Soul

AARP Solves 25 of Your Problems

Driver Safety

Maintenance & Safety

Trends & Technology

AARP Smart Guide

How to Clean Your Car

We Need To Talk

Assess Your Loved One's Driving Skills

AARP Smart Driver Course

Building Resilience in Difficult Times

Tips for Finding Your Calm

Weight Loss After 50 Challenge

Cautionary Tales of Today's Biggest Scams

7 Top Podcasts for Armchair Travelers

Jean Chatzky: ‘Closing the Savings Gap’

Quick Digest of Today's Top News

AARP Top Tips for Navigating Life

Get Moving With Our Workout Series

You are now leaving AARP.org and going to a website that is not operated by AARP. A different privacy policy and terms of service will apply.

Go to Series Main Page

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension): A Guide to Symptoms, Causes and Tests

Explore risk factors for high blood pressure, testing options and why it is known as the silent killer.

Kimberly Hayes,

Merle Myerson, M.D.

High Blood Pressure Guide

- Symptoms, causes and tests

- High blood pressure myths

- Alcohol and blood pressure

- Hypertension headache myths

Smoking and high blood pressure

- Anxiety, stress and hypertension

- Is hypertension genetic?

- Medications that raise blood pressure

- Home blood pressure monitoring

- Surprising causes of hypertension

A staggering three-quarters of Americans over age 60 have high blood pressure, otherwise known as hypertension, putting them at increased risk for stroke, heart attack and heart failure. Men tend to have higher blood pressure rates in their younger years, but women catch up around the time of menopause.

Hypertension increases with age: Only 22.4 percent of people ages 18–39 have the condition. But those numbers rise to 54.5 percent for people age 40–59 and 74.5 percent for people 60 and over. These alarming rates are even higher for people of color, especially for African Americans. Hypertension prevalence across all ages is higher among non-Hispanic Black adults (57.1 percent) than non-Hispanic white (43.6 percent) or Hispanic (43.7 percent) adults.

What causes high blood pressure?

“The main cause of high blood pressure is aging blood vessels,” said Jordana Cohen, MD, MSCE, Associate Professor of Medicine, Renal-Electrolyte and Hypertension at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. She is also chair of the Hypertension Science Committee for the American Heart Association.

Blood vessels tend to stiffen with age and becomes less flexible, which can drive up the pressure inside them. However, studies have found that there are populations of older people who don’t have high blood pressure, for example the remote South American Yanomami tribe, whose members live in near-total isolation in the rainforests in southern Venezuela and northern Brazil. They eat very little salt and fat and have a diet high in plantains, fruit and meat, and their blood pressures stay the same as when they were younger.

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

Research suggests that this could be related to their lower consumption of salt , and the fact that they eat a lot of potassium, Cohen said. They also have less exposure to modern-day risk factors such as pollution, stress and other diseases that are prevalent in our society, such as diabetes, heart disease and kidney disease, which all contribute to high blood pressure, Cohen added.

Understanding a blood pressure reading

Blood pressure is measured in stages, with a normal range being less than 120/80. The top number — the systolic— measures the pressure in your arteries when your heart beats. The bottom number — the diastolic — measures the pressure in your arteries when the blood is flowing back to the heart through the veins. Your blood pressure numbers are measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). Stages at or above 120/80 include: elevated, stage 1 hypertension and stage 2 hypertension. A severely elevated blood pressure of 180/120 or greater can be a hypertensive crisis and could require guidance from your doctor, or in some cases, emergency care.

“The top number is what’s mostly considered our biggest indicator of risk,” Cohen said. It also tends to be the most responsive to treatment. The bottom number tends to be higher in younger people and then gets lower with age. Older patients can see a very wide split between their top and the bottom number, which can be concerning, Cohen said, especially if the bottom number gets too low as it can increase the risk of falls and kidney problems. “This is something that I see in my much older patients in their 80s, 90s and 100s.”

What are symptoms of high blood pressure?

Most people with hypertension shouldn’t expect to experience symptoms from high blood pressure.

“If your expectation is that you’re going to feel it, then you’re going to be somebody who’s missing it 90 percent of the time,” Cohen said.

Generally, people will not feel any symptoms of high blood pressure unless they are having the severely elevated blood pressure, which occurs when a patient’s underlying high blood pressure has accelerated to 180/120 or above and is damaging their vital organs, including the brain, heart, kidneys or eyes. In this scenario the person could face additional symptoms including sudden headache, blurred vision or vomiting, and should seek emergency medical assistance. It’s important to note that people with poorly controlled blood pressure could have readings in this higher range, but as long as they are not having other symptoms it may not be an emergency. However, they still should follow up with their doctor within a couple of days.

Measuring your blood pressure

While patients may assume a blood pressure measurement at a doctor’s office is the most accurate, that’s not always the case. To get a good blood pressure reading, it’s recommended the person sit in a quiet environment with their feet flat on the floor and their arms on a table or desk in front of them, which may not always be how you are positioned at the doctor’s office. Couple that with the stress of a doctor’s visit, and it’s easy to see how readings may not be 100 percent accurate.

White coat hypertension and masked hypertension

According to the Cleveland Clinic, between 15 to 30 percent of people have so-called white coat hypertension, which means their blood pressure is higher at a health care provider’s office, but normal at home. Estimates vary, however, with some research saying up to 50 percent or more people have white coat hypertension.

AARP NEWSLETTERS

%{ newsLetterPromoText }%

%{ description }%

Privacy Policy

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

But it’s important not to discount these higher doctor’s office readings totally. “I think white coat can be used to deny high blood pressure,” said Beverly Green, M.D., senior investigator for Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. “There’s literature showing that people with white coat hypertension are higher risk of eventually getting high blood pressure.”

At the opposite end of white coat hypertension is masked hypertension. Approximately 10 to 40 percent of people have this condition, which occurs when blood pressure is normal in the doctor’s office but high in everyday life. This can happen among people who typically smoke but avoid doing so right before a doctor’s visit. People who have sleep apnea could also be at risk, Cohen said.

The importance of home blood pressure monitoring

With home monitoring, patients can hopefully control their environment and take their readings at ideal times. (Look for guidelines on checking your blood pressure at home at the end of this article.)

It’s important to make sure you are using an accurate device, and more than two-thirds of devices on the market right now are not, Cohen said. The website validatebp.org from the American Medical Association provides a list of devices that have been validated for accuracy and includes price ranges.

It is of course important to still get your blood pressure checked at your doctor’s office and to discuss the readings you take at home with them. Some providers use an automated office blood pressure machine, which provides multiple readings over a series of intervals. This can be used in a quiet room without a medical professional present, hopefully reducing white coat hypertension.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

Some patients are referred for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, where your blood pressure is measured on a continuous basis for 24 hours as you live your daily life, even as you sleep. Your doctor will calculate the average blood pressure and also look at the range, how often readings are high or low, and if there is a “dip,” meaning a lowering of blood pressure during nighttime hours, which is normal. Ambulatory monitoring can be used for patients who have had high blood pressure readings but haven’t yet started treatment, need changes to their medications, or whose blood pressure is not responding to medications, or who have felt dizziness or have had fainting episodes.

AARP® Vision Plans from VSP™

Exclusive vision insurance plans designed for members and their families

Green has used ambulatory monitoring herself and, to her surprise, found that she had high blood pressure during the workday. “I wouldn’t have known that I had high blood pressure while at work, and there are a lot of people walking around just like that whose hypertension wouldn’t have been caught otherwise,” Green added.

It’s been shown both home monitors and the ambulatory monitors do a better job predicting heart attacks , strokes and death because they catch the variability in the average blood pressure much better than you can get from occasional blood pressure readings in the doctor’s office, Green said.

Unfortunately, ambulatory monitoring can be difficult for some patients to access as it’s a subspecialty in medicine and not available in every doctor’s office, Cohen says. But studies have shown that home blood pressure monitoring with a store-bought monitor is a good surrogate for ambulatory. “It’s not expensive and everyone can do it.”

Read more about home blood pressure monitoring .

This high blood pressure guide shows you the science behind high blood pressure and the various factors that can play a role in high blood pressure causes and symptoms:

High blood pressure myths

Blood pressure myths about types of salt, wine intake and medications persist in popular culture. Here’s a look at six blood pressure myths, plus tips you can use to maintain a healthy blood pressure.

Read more about high blood pressure myths .

LEARN MORE ABOUT AARP MEMBERSHIP.

Alcohol and high blood pressure

Research has traditionally shown that heavy drinking raises your risk for high blood pressure, but now experts believe even light to moderate drinking can carry risks.

Read more about alcohol and high blood pressure .

While smoking is not a primary risk factor for high blood pressure, the habit can damage blood vessels, contributing to plaque buildup and hardening arteries. Nicotine, the addictive chemical compound in cigarettes, can also increase blood pressure.

Read more about smoking and high blood pressure .

Anxiety, stress and high blood pressure

Stress can trigger blood pressure to rise in the short-term, and if that happens frequently enough, it could damage the blood vessels, heart and kidneys, similar to what happens in people with long-term hypertension. But that’s different from saying stress or anxiety themselves produce high blood pressure.

Read more about the links between anxiety, stress and high blood pressure .

Is high blood pressure genetic?

A May 2024 study in Nature Genetic s analyzed the genes of more than 1 million people of European heritage and uncovered some 113 gene variants associated with high blood pressure. While you can’t change your genes, there are lifestyle changes you can make that will likely have a much bigger impact on your risk for high blood pressure.

Read more about high blood pressure and genetics .

Medications that cause high blood pressure

Pain and migraine medicines, decongestants, corticosteroids and some herbal supplements are all examples of pills that could raise your blood pressure. Yet a 2021 study revealed that 18.5 percent of adults with hypertension were taking one or more of these medications.

Read more about medications that can raise blood pressure .

Surprising causes of high blood pressure

While salt is one of the most associated risk factors for high blood pressure, there are a handful of unsuspected foods, habits and health issues that can play a role, too.

Read more surprising things that can raise your blood pressure .

Hypertension headache

A common myth persists among some patients that they can sense their blood pressure is creeping up because they’ve started getting headaches. Yet research shows the link between high blood pressure and headaches is shaky, particularly for mild and moderate high blood pressure.

Read more about high blood pressure headaches .

How to properly measure your blood pressure at home

- Make sure your blood pressure monitor has been validated at validatebp.org. Confirm that the cuff fits by measuring around your upper arm and choosing a monitor with the correct cuff size. Wrist and finger monitors are not recommended due to less reliable readings.

- Be in a quiet room , avoid conversation and relax for three to five minutes before taking your blood pressure.

- Make sure that you’re positioned correctly : Sit at a kitchen table or a desk where your feet are flat on the floor, your back is supported and your arms are resting on the table at the level of your heart.

- Put the cuff on your bare arm. If you must push your sleeve up, make sure it is loose fitting. A tight sleeve could create a tourniquet effect and raise your blood pressure.

- Empty your bladder prior to a reading. Having a full bladder can raise your blood pressure, according to the AMA.

- Take your blood pressure twice . People often get a surge of adrenaline when they first take the reading.

- Record your blood pressure measurements , along with the time of day you took them, and discuss these results with your doctor. The AHA offers a printable blood pressure log .

- Smoke, eat or drink coffee or other caffeinated beverages at least 30 minutes before taking your blood pressure.

“We usually recommend checking two back-to-back readings about 30 seconds to a minute apart in the morning, before taking medications … and two back-to-back readings in the evening before going to bed, at least an hour after dinner, for a minimum of three days per month,” said Jordana Cohen, MD, MSCE, Associate Professor of Medicine, Renal-Electrolyte and Hypertension at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. “That’s the minimum needed to get a really accurate reading.”

Doing this series of checks once a month is recommended for people currently being treated with blood pressure medication. If your blood pressure is borderline, three days of monitoring every two to three months is recommended, Cohen said.

While these are general guidelines, you should discuss how frequently to take your blood pressure with your doctor, based on your individual medical needs.

The website Targetbp.org offers additional tools and guides for measuring your blood pressure accurately at home as does the AHA .

Kimberly Hayes is an editor-writer for AARP and has written on health and social justice issues for numerous organizations, including the National Organization for Women, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights. She previously served as editor of Native American Report . Dr. Merle Myerson is a board-certified cardiologist with specialties in sports medicine, lipids, women’s health and prevention of cardiovascular disease.

A Guide to High Blood Pressure

Discover the risk factors, diagnostic process and potential symptoms of hypertension

Discover AARP Members Only Access

Already a Member? Login

More From AARP

6 Ways to Lower Your Blood Pressure Without Medication

Try these tactics to help fight hypertension and bring your numbers down

9 Best (and 8 Worst) Foods for High Blood Pressure

8 Major Health Risks for People 50 and Older

A look at the top killers — and how to dodge them

Recommended for You

AARP Value & Member Benefits

Learn, earn and redeem points for rewards with our free loyalty program

AARP® Dental Insurance Plan administered by Delta Dental Insurance Company

Dental insurance plans for members and their families

The National Hearing Test

Members can take a free hearing test by phone

AARP® Staying Sharp®

Activities, recipes, challenges and more with full access to AARP Staying Sharp®

SAVE MONEY WITH THESE LIMITED-TIME OFFERS

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

High blood pressure dangers: hypertension's effects on your body.

High blood pressure is a risk factor for more than heart disease. Learn what other health conditions high blood pressure can cause.

High blood pressure complications

High blood pressure can cause many complications.

High blood pressure, also called hypertension, can quietly damage the body for years before symptoms appear. Without treatment, high blood pressure can lead to disability, a poor quality of life, or even a deadly heart attack or stroke.

Blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). In general, hypertension is a blood pressure reading of 130/80 mm Hg or higher.

Treatment and lifestyle changes can help control high blood pressure to lower the risk of life-threatening health conditions.

Damage to the arteries

Healthy arteries are flexible, strong and elastic. Their inner lining is smooth so that blood flows freely, supplying vital organs and tissues with nutrients and oxygen.

Over time, high blood pressure increases the pressure of blood flowing through the arteries. This may cause:

- Damaged and narrowed arteries. High blood pressure can damage the cells of the arteries' inner lining. When fats from food enter the bloodstream, they can collect in the damaged arteries. In time, the artery walls become less elastic. This limits blood flow throughout the body.

- Aneurysm. Over time, the constant pressure of blood moving through a weakened artery can cause part of the artery wall to bulge. This is called an aneurysm. An aneurysm can burst open and cause life-threatening bleeding inside the body. Aneurysms can form in any artery. But they're most common in the body's largest artery, called the aorta.

Damage to the heart

High blood pressure can cause many heart conditions, including:

- Coronary artery disease. High blood pressure can narrow and damage the arteries that supply blood to the heart. This damage is known as coronary artery disease. Too little blood flow to the heart can lead to chest pain, called angina. It can lead to irregular heart rhythms, called arrhythmias. Or it can lead to a heart attack.

- Heart failure. High blood pressure strains the heart. Over time, this can cause the heart muscle to weaken or become stiff and not work as well as it should. The overwhelmed heart slowly starts to fail.

- Enlarged left heart. High blood pressure forces the heart to work harder to pump blood to the rest of the body. This causes the lower left heart chamber, called the left ventricle, to thicken and to enlarge. A thickened and enlarged left ventricle raises the risk of heart attack and heart failure. It also increases the risk of death when the heart suddenly stops beating, called sudden cardiac death.

- Metabolic syndrome. High blood pressure raises the risk of metabolic syndrome. This syndrome is a cluster of health conditions that can lead to can lead to heart disease, stroke and diabetes. The health conditions that make up metabolic syndrome are high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high levels of blood fats called triglycerides, low levels of HDL cholesterol, which is the "good" cholesterol, and too much body fat around the waist.

Damage to the brain

The brain depends on a nourishing blood supply to work right. High blood pressure may affect the brain in the following ways:

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Sometimes this is called a ministroke. A TIA happens when the blood supply to part of the brain is blocked for a short time. Hardened arteries or blood clots caused by high blood pressure can cause TIAs. A TIA is often a warning sign of a full-blown stroke.

- Stroke. A stroke happens when part of the brain doesn't get enough oxygen and nutrients. Or it can happen when there is bleeding inside or around the brain. These problems cause brain cells to die. Blood vessels damaged by high blood pressure can narrow, break or leak. High blood pressure also can cause blood clots to form in the arteries leading to the brain. The clots can block blood flow, raising the risk of a stroke.

- Dementia. Narrowed or blocked arteries can limit blood flow to the brain. This could lead to a certain type of dementia, called vascular dementia. A single stroke or multiple tiny strokes that interrupt blood flow to the brain also can cause vascular dementia.

- Mild cognitive impairment. This condition involves having slightly more troubles with memory, language or thinking than other adults your age have. But the changes aren't major enough to impact your daily life, as with dementia. High blood pressure may lead to mild cognitive impairment.

Damage to the kidneys

Kidneys filter extra fluid and waste from the blood — a process that requires healthy blood vessels. High blood pressure can damage the blood vessels in and leading to the kidneys. Having diabetes along with high blood pressure can worsen the damage.

Damaged blood vessels prevent the kidneys from being effective at filtering waste from the blood. This allows dangerous levels of fluid and waste to collect. When the kidneys don't work well enough on their own, it's a serious condition called kidney failure. Treatment may include dialysis or a kidney transplant. High blood pressure is one of the most common causes of kidney failure.

Damage to the eyes

High blood pressure can damage the tiny, delicate blood vessels that supply blood to the eyes, causing:

- Damage to the blood vessels in the retina, also called retinopathy. The retina is a layer of light-sensing cells at the back of the eye. Damage to the blood vessels in the retina can lead to bleeding in the eye, blurred vision and complete loss of vision. Having diabetes along with high blood pressure raises the risk of retinopathy.

- Fluid buildup under the retina, also called choroidopathy. This condition can result in distorted vision or sometimes scarring that makes vision worse.

- Nerve damage, also called optic neuropathy. Blocked blood flow can damage the nerve that sends light signals to the brain, called the optic nerve. The damage can lead to bleeding within the eye or vision loss.

Sexual conditions

Trouble getting and keeping an erection is called erectile dysfunction. It becomes more and more common after age 50. But people with high blood pressure are even more likely to have erectile dysfunction. That's because limited blood flow caused by high blood pressure can block blood from flowing to the penis.

High blood pressure can reduce blood flow to the vagina. Reduced blood flow to the vagina can lead to less sexual desire or arousal, vaginal dryness, or trouble having orgasms.

High blood pressure emergencies

High blood pressure usually is an ongoing condition that slowly causes damage over years. But sometimes blood pressure rises so quickly and seriously that it becomes a medical emergency. When this happens, treatment is needed right away, often with hospital care.

In these situations, high blood pressure can cause:

- Chest pain.

- Complications in pregnancy, such as the blood pressure-related conditions preeclampsia or eclampsia.

- Heart attack.

- Memory loss, personality changes, trouble concentrating, irritable mood or gradual loss of consciousness.

- Serious damage to the body's main artery, also called aortic dissection.

- Sudden impaired pumping of the heart, leading to fluid backup in the lungs that results in shortness of breath, also called pulmonary edema.

- Sudden loss of kidney function.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Basile J, et al. Overview of hypertension in adults. https://www.uptodate.contents/search. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- Health threats from high blood pressure. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/health-threats-from-high-blood-pressure. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- High blood pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/high-blood-pressure. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- Hypertensive crisis: When you should call 9-1-1 for high blood pressure. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/understanding-blood-pressure-readings/hypertensive-crisis-when-you-should-call-911-for-high-blood-pressure. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- How high blood pressure can lead to vision loss. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/health-threats-from-high-blood-pressure/how-high-blood-pressure-can-lead-to-vision-loss. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA). American Stroke Association. https://www.stroke.org/en/about-stroke/types-of-stroke/tia-transient-ischemic-attack. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- Petersen R. Mild cognitive impairment: Epidemiology, pathology, and clinical assessment. https://www.uptodate.contents/search. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- Whelton PK, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018; doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

- Arnett DK, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019; doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678.

- Unger T, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Journal of Hypertension. 2020; doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000002453.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hypertension in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021; doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4987.

- Coles S, et al. Blood pressure targets in adults with hypertension: A clinical practice guideline from the AAFP. American Family Physician. 2022; https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2022/1200/practice-guidelines-hypertension.html. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- The anatomy of blood pressure. American Heart Association. https://watchlearnlive.heart.org/index.php?moduleSelect=bpanat. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- What is aortic aneurysm? National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/aortic-aneurysm. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- What is metabolic syndrome? American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/metabolic-syndrome/about-metabolic-syndrome. Accessed Aug. 11, 2023.

- How high blood pressure can lead to kidney damage or failure. American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/health-threats-from-high-blood-pressure/how-high-blood-pressure-can-lead-to-kidney-damage-or-failure. Accessed Sept. 19, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on High Blood Pressure

- Blood Pressure Monitors at Mayo Clinic Store

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

- Medication-free hypertension control

- Alcohol: Does it affect blood pressure?

- Alpha blockers

- Amputation and diabetes

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- Anxiety: A cause of high blood pressure?

- Arteriosclerosis / atherosclerosis

- Artificial sweeteners: Any effect on blood sugar?

- AskMayoMom Pediatric Urology

- Beta blockers

- Beta blockers: Do they cause weight gain?

- Beta blockers: How do they affect exercise?

- Birth control pill FAQ

- Blood glucose meters

- Blood glucose monitors

- Blood pressure: Can it be higher in one arm?

- Blood pressure chart

- Blood pressure cuff: Does size matter?

- Blood pressure: Does it have a daily pattern?

- Blood pressure: Is it affected by cold weather?

- Blood pressure medication: Still necessary if I lose weight?

- Blood pressure medications: Can they raise my triglycerides?

- Blood pressure readings: Why higher at home?

- Blood pressure test

- Blood pressure tip: Get more potassium

- Blood sugar levels can fluctuate for many reasons

- Blood sugar testing: Why, when and how

- Bone and joint problems associated with diabetes

- How kidneys work

- Bump on the head: When is it a serious head injury?

- Caffeine and hypertension

- Calcium channel blockers

- Calcium supplements: Do they interfere with blood pressure drugs?

- Can whole-grain foods lower blood pressure?

- Central-acting agents

- Choosing blood pressure medicines

- Chronic daily headaches

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic kidney disease: Is a clinical trial right for me?

- Coarctation of the aorta

- COVID-19: Who's at higher risk of serious symptoms?

- Cushing syndrome

- DASH diet: Recommended servings

- Sample DASH menus

- Diabetes and depression: Coping with the two conditions

- Diabetes and exercise: When to monitor your blood sugar

- Diabetes and heat

- 10 ways to avoid diabetes complications

- Diabetes diet: Should I avoid sweet fruits?

- Diabetes diet: Create your healthy-eating plan

- Diabetes foods: Can I substitute honey for sugar?

- Diabetes and liver

- Diabetes management: How lifestyle, daily routine affect blood sugar

- Diabetes symptoms

- Diabetes treatment: Can cinnamon lower blood sugar?

- Using insulin

- Diuretics: A cause of low potassium?

- Diuretics: Cause of gout?

- Do infrared saunas have any health benefits?

- Drug addiction (substance use disorder)

- Eating right for chronic kidney disease

- High blood pressure and exercise

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Free blood pressure machines: Are they accurate?

- Home blood pressure monitoring

- Glomerulonephritis

- Glycemic index: A helpful tool for diabetes?

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Headaches and hormones

- Headaches: Treatment depends on your diagnosis and symptoms

- Heart and Blood Health

- Herbal supplements and heart drugs

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High blood pressure and cold remedies: Which are safe?

- High blood pressure and sex

- How does IgA nephropathy (Berger's disease) cause kidney damage?

- How opioid use disorder occurs

- How to tell if a loved one is abusing opioids

- What is hypertension? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- Hypertension FAQs

- Hypertensive crisis: What are the symptoms?

- Hypothermia

- I have IgA nephrology. Will I need a kidney transplant?

- IgA nephropathy (Berger disease)

- Insulin and weight gain

- Intracranial hematoma

- Isolated systolic hypertension: A health concern?

- What is kidney disease? An expert explains

- Kidney disease FAQs

- Kratom: Unsafe and ineffective

- Kratom for opioid withdrawal

- L-arginine: Does it lower blood pressure?

- Late-night eating: OK if you have diabetes?

- Lead poisoning

- Living with IgA nephropathy (Berger's disease) and C3G

- Low-phosphorus diet: Helpful for kidney disease?

- Medications and supplements that can raise your blood pressure

- Menopause and high blood pressure: What's the connection?

- Molar pregnancy

- MRI: Is gadolinium safe for people with kidney problems?

- New Test for Preeclampsia

- Nighttime headaches: Relief

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- Opioid stewardship: What is it?

- Pain Management

- Pheochromocytoma

- Picnic Problems: High Sodium

- Pituitary tumors

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Polypill: Does it treat heart disease?

- Poppy seed tea: Beneficial or dangerous?

- Postpartum preeclampsia

- Preeclampsia

- Prescription drug abuse

- Primary aldosteronism

- Pulse pressure: An indicator of heart health?

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Rattlesnakes, scorpions and other desert dangers

- Reactive hypoglycemia: What can I do?

- Renal diet for vegetarians

- Resperate: Can it help reduce blood pressure?

- Scorpion sting

- Secondary hypertension

- Serotonin syndrome

- Sleep deprivation: A cause of high blood pressure?

- Spider bites

- Stress and high blood pressure

- Symptom Checker

- Takayasu's arteritis

- Tapering off opioids: When and how

- Tetanus shots: Is it risky to receive 'extra' boosters?

- The dawn phenomenon: What can you do?

- Understanding complement 3 glomerulopathy (C3G)

- Understanding IgA nephropathy (Berger's disease)

- Vasodilators

- Vegetarian diet: Can it help me control my diabetes?

- Vesicoureteral reflux

- Video: Heart and circulatory system

- How to measure blood pressure using a manual monitor

- How to measure blood pressure using an automatic monitor

- Obstructive sleep apnea: What happens?

- What is blood pressure?

- Can a lack of vitamin D cause high blood pressure?

- What are opioids and why are they dangerous?

- White coat hypertension

- Wrist blood pressure monitors: Are they accurate?

- Effectively managing chronic kidney disease

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Do not share pain medication

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Avoid opioids for chronic pain

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Be careful not to pop pain pills

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Out of shape kids and diabetes

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- High blood pressure dangers - Hypertensions effects on your body

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 June 2024

Consider hypertension risk factors once again

- Masaki Mogi 1 ,

- Satoshi Hoshide 2 &

- Kazuomi Kario 2

Hypertension Research volume 47 , pages 1443–1444 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

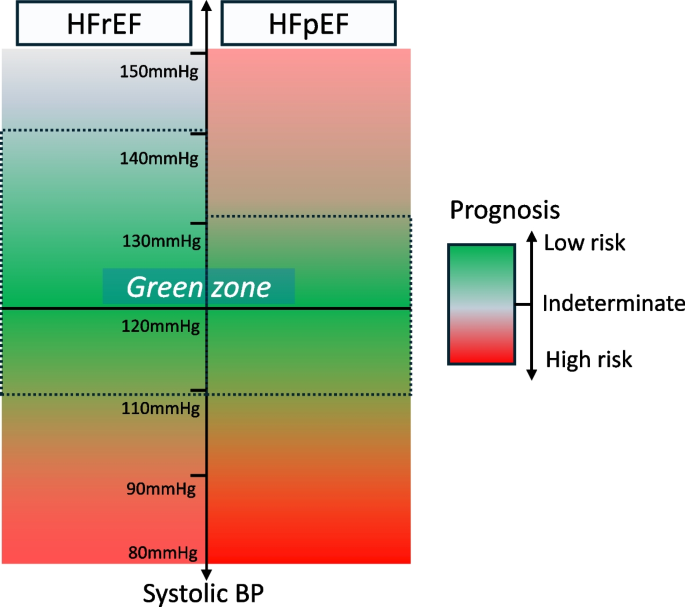

Takase et al. examined risk factors for hypertension using data from the Tohoku Medical Megabank cohort study, and found that body mass index, salt intake, urinary Na/K ratio, γ-GTP level, and alcohol intake were associated with risk factors for elevated systolic blood pressure [ 1 ]. Aida et al. examined the relationship between income and blood pressure using data from the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan, and found that the lowest income group had 15.3% more hypertension than the highest income group in men and 18.7% in women, and the effects of lifestyle habits such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity were considered [ 2 ]. In a similar report, Gupta et al. looked at the incidence of hypertension in India by region and attributed the increase in hypertension among the younger generation in the less developed rural areas to a lack of knowledge and adequate treatment for hypertension via inequalities [ 3 ]. Using data on 920,000 individuals from the Japan Health Insurance Association, Mori et al. examined the association between excessive antihypertensive treatment and cardiovascular events in patients at low risk for cardiovascular disease and reported that the incidence of events increases when diastolic blood pressure falls below 60 mmHg, sounding the alarm against excessive diastolic blood pressure reduction [ 4 ]. Sleep apnea in obese individuals is a known risk factor for hypertension. However, Inoue et al. found that the 3% oxygen desaturation index (3% ODI) obtained by polysomnography correlated with the presence of hypertension even in non-obese individuals, and the possibility of sleep disorders should be considered in hypertensive patients, even in non-obese individuals [ 5 ]. In addition, because women who experience gestational hypertension are at higher risk for future cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome, postpartum care is needed. Ushida et al. include a review article on the importance and methods of such care [ 6 ]. Detailed risk management in women who experience hypertension during pregnancy is desirable. Moreover, Yan et al. reported that a follow-up study of 330 very elderly hypertensive patients aged 80 years or older with a mean follow-up of 3.8 years showed a U-shaped relationship between baseline systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure values and the development of future frailty, with nadir values of systolic blood pressure 140 mmHg, pulse pressure was 77 mmHg [ 7 ]. Furthermore, as biomarkers of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, An et al. reported high uric acid levels as a risk factor for elevated arterial stiffness [ 8 ], and Ding et al. reported the importance of serum total homocysteine levels in relation to renal function [ 9 ].

In addition, two studies on atrial fibrillation are reported in this month’s issue. The first examined the presence of atrial fibrillation in 4161 hypertensive patients aged 65 years or older in Shanghai and found that the incidence was 2.21 times higher in newly hypertensive patients than in those who were already hypertensive, suggesting the need to be aware of the development of atrial fibrillation in newly hypertensive patients [ 10 ]. The second, from Chichareon et al. in Thailand, showed that in 3172 patients with atrial fibrillation, the higher the blood pressure variability, the higher the risk of stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, and death [ 11 ].

In short, this month’s Special Issue - Asian Studies is a reminder of the dangers of hypertension and the need for meticulous hypertension care.

Takase M, Nakaya N, Tanno K, Kogure M, Hatanaka R, Nakaya K, et al. Relationship between traditional risk factors for hypertension and systolic blood pressure in the Tohoku Medical Megabank Community-based Cohort. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01582-1 .

Aida J, Inoue Y, Tabuchi T, Kondo N. Modifiable risk factors of inequalities in hypertension: Analysis of 100 million health checkups recipients. Hypertens Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01615-9 .

Rajeev Gupta R, Gaur K, Ahuja S, Anjana RM. Recent Studies on Hypertension Prevalence and Control in India 2023. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01585-y .

Mori Y, Mizuno A, Fukuma S. Low on-treatment blood pressure and cardiovascular events in patients without elevated risk: A nationwide cohort study. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01593-y .

Inoue M, Sakata S, Arima H, Yamato I, Oishi E, Ibaraki A, et al. Sleep-related breathing disorder in a Japanese occupational population and its association with hypertension - Stratified analysis by obesity status. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01612-y .

Ushida T, Tano S, Imai K, Matsuo S, Kajiyama H, Kotani T. Postpartum and interpregnancy care of women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01641-7 .

Yan J, Wu B, Lu B, Zhu Z, Di N, Yang C, et al. Association between baseline office blood pressure level and the incidence and development of long-term frailty in the community-dwelling very elderly with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01613-x .

An L, Wang Y, Liu L, Miao C, Zu L, Wang G, et al. High serum uric acid is a risk factor for arterial stiffness in a Chinese hypertensive population: A cohort study. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01591-0 .

Ding C, Li J, Wei Y, Fan W, Cao T, Chen Z, et al. Associations of total homocysteine and kidney function with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in hypertensive patients: a mediation and joint analysis. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01614-w .

Zhang W, Chen Y, Hu LX, Xia JH, Ye XF, Cheng YB, et al. New-onset hypertension as a contributing factor to the incidence of atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01617-7 .

Chichareon P, Methavigul K, Lip GYH, Krittayaphong R. Systolic blood pressure visit-to-visit variability and outcomes in Asians patients with atrial fibrillation. Hypertens Res. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01592-z .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pharmacology, Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine, Toon, Japan

Masaki Mogi

Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Jichi Medical University School of Medicine, Shimotsuke, Japan

Satoshi Hoshide & Kazuomi Kario

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Masaki Mogi .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mogi, M., Hoshide, S. & Kario, K. Consider hypertension risk factors once again. Hypertens Res 47 , 1443–1444 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01680-0

Download citation

Received : 21 March 2024

Accepted : 26 March 2024

Published : 05 June 2024

Issue Date : June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-024-01680-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Risk factors

- Atrial fibrillation

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Essay on Hypertension

Students are often asked to write an essay on Hypertension in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Hypertension

What is hypertension.

Hypertension is when blood pushes too hard against the walls of your blood vessels. Imagine a garden hose with too much water pressure; it’s similar for your blood vessels. It’s often called high blood pressure and is a common health issue.

Causes of High Blood Pressure

High blood pressure can come from eating too much salt, not exercising, stress, or family history. Sometimes, it happens for no clear reason. It’s important to eat healthy and stay active to prevent it.

Why It’s Serious

If not treated, hypertension can hurt important organs like the heart and kidneys. It can lead to heart attacks, strokes, and other health problems. That’s why checking your blood pressure regularly is crucial.

Treatment and Control

Doctors usually suggest changes in diet and exercise to manage high blood pressure. In some cases, medicine is also needed. Eating less salt, more fruits and vegetables, and regular physical activity can help control it.

250 Words Essay on Hypertension

Hypertension is another name for high blood pressure. It’s a health problem where the force of your blood against your artery walls is too high. Imagine a garden hose with too much water pressure; it’s similar with blood in your body’s pipes.

Causes of Hypertension

Many things can make your blood pressure go up. Eating too much salt, not exercising, being overweight, and stress are common causes. Sometimes, it runs in families, so your parents might have it too.

Why Hypertension is Bad

High blood pressure is sneaky because you can’t feel it, but it can hurt your body. It can make your heart work too hard and weaken your blood vessels. Over time, this can lead to heart problems and strokes, which are very serious.

How to Know If You Have It

Doctors can check your blood pressure with a cuff that squeezes your arm. It’s quick and doesn’t hurt. Numbers tell if your pressure is normal, a bit high, or too high. Regular checks are important.

Keeping Blood Pressure Normal

To keep your blood pressure in check, eat healthy foods like fruits and veggies, stay active, and keep a healthy weight. If your doctor says so, you might need medicine too. Remember, taking care of your blood pressure is taking care of your heart.

500 Words Essay on Hypertension

What is hypertension.

Hypertension is the medical term for high blood pressure. Imagine the water pipes in your house. When the water pressure is too high, pipes can get damaged. Similarly, when blood moves through your body with too much force, it can harm your blood vessels and organs.