COMM 101: Fundamentals of Public Speaking - Valparaiso

- Delivery Skills

- Stage Fright

- Body Language / Non-Verbal Communication

- Listening Skills

- Quotation Resources

- Speech Outline Examples

- Speech Examples

- More Speech Examples

- Presentation Options

- Citation Resources This link opens in a new window

A basic speech outline should include three main sections:

- The Introduction -- This is where you tell them what you're going to tell them.

- The Body -- This is where you tell them.

- The Conclusion -- This is where you tell them what you've told them.

- Speech Outline Formatting Guide The outline for a public speech, according to COMM 101 online textbook The Public Speaking Project , p.p. 8-9.

Use these samples to help prepare your speech outlines and bibliographies:

- Sample Speech Preparation Outline This type of outline is very detailed with all the main points and subpoints written in complete sentences. Your bibliography should be included with this outline.

- Sample Speech Speaking Outline This type of outline is very brief and uses phrases or key words for the main points and subpoints. This outline is used by the speaker during the speech.

- << Previous: Quotation Resources

- Next: Informative Speeches >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 10:02 AM

- URL: https://library.ivytech.edu/Valpo_COMM101

- Ask-a-Librarian

- [email protected]

- (219) 464-8514 x 3021

- Library staff | Find people

- Library Guides

- Student Life & Activities

- Testing Services

- B&N Bookstore

How to Write an Effective Speech Outline: A Step-by-Step Guide

- The Speaker Lab

- March 8, 2024

Table of Contents

Mastering the art of speaking starts with crafting a stellar speech outline. A well-structured outline not only clarifies your message but also keeps your audience locked in.

In this article, you’ll learn how to mold outlines for various speech types, weaving in research that resonates and transitions that keep listeners on track. We’ll also show you ways to spotlight crucial points and manage the clock so every second counts. When it’s time for final prep, we’ve got smart tips for fine-tuning your work before stepping into the spotlight.

Understanding the Structure of a Speech Outline

An effective speech outline is like a map for your journey as a speaker, guiding you from start to finish. Think of it as the blueprint that gives shape to your message and ensures you hit all the right notes along the way.

Tailoring Your Outline for Different Speech Types

Different speeches have different goals: some aim to persuade, others inform or celebrate. Each type demands its own structure in an outline. For instance, a persuasive speech might highlight compelling evidence while an informative one focuses on clear explanations. Crafting your outline with precision means adapting it to fit these distinct objectives.

Incorporating Research and Supporting Data

Your credibility hinges on solid research and data that back up your claims. When writing your outline, mark the places where you’ll incorporate certain pieces of research or data. Every stat you choose should serve a purpose in supporting your narrative arc. And remember to balance others’ research with your own unique insights. After all, you want your work to stand out, not sound like someone else’s.

The Role of Transitions in Speech Flow

Slick transitions are what turn choppy ideas into smooth storytelling—think about how bridges connect disparate land masses seamlessly. They’re not just filler; they carry listeners from one thought to another while maintaining momentum.

Incorporate transitions that feel natural yet keep people hooked. To keep things smooth, outline these transitions ahead of time so nothing feels left up to chance during delivery.

Techniques for Emphasizing Key Points in Your Outline

To make certain points pop off the page—and stage—you’ll need strategies beyond bolding text or speaking louder. Use repetition wisely or pause strategically after delivering something significant. Rather than go impromptu, plan out what points you want to emphasize before you hit the stage.

Timing Your Speech Through Your Outline

A watchful eye on timing ensures you don’t overstay—or undercut—your moment under the spotlight. The rhythm set by pacing can be pre-determined through practice runs timed against sections marked clearly in outlines. Practice will help ensure that your grand finale isn’t cut short by surprise.

Free Download: 6 Proven Steps to Book More Paid Speaking Gigs in 2024

Download our 18-page guide and start booking more paid speaking gigs today!

Depending on the type of speech you’re giving, your speech outline will vary. The key ingredients—introduction, body, and conclusion—are always there, but nuances like tone or message will change with each speaking occasion.

Persuasive Speeches: Convincing With Clarity

When outlining a persuasive speech, arrange your arguments from strong to strongest. The primacy effect works wonders here, so make sure to start off with a strong point. And just when they think they’ve heard it all, hit them with an emotional story that clinches the deal.

You might start by sharing startling statistics about plastic pollution before pivoting to how individuals can make a difference. Back this up with data on successful recycling programs which demonstrate tangible impact, a technique that turns facts into fuel for action.

Informative Speeches: Educating Without Overwhelming

An informative speech shouldn’t feel like drinking from a fire hose of facts and figures. Instead, lay out clear subtopics in your outline and tie them together with succinct explanations—not unlike stepping stones across a stream of knowledge.

If you’re talking about breakthroughs in renewable energy technology, use bullet points to highlight different innovations then expand upon their potential implications one at a time so the audience can follow along without getting lost in technical jargon or complexity.

Ceremonial Speeches: Creating Moments That Matter

In a ceremonial speech you want to capture emotion. Accordingly, your outline should feature personal anecdotes and quotes that resonate on an emotional level. However, make sure to maintain brevity because sometimes less really is more when celebrating milestones or honoring achievements.

Instead of just going through a hero’s whole life story, share the powerful tales of how they stepped up in tough times. This approach hits home for listeners, letting them feel the impact these heroes have had on their communities and sparking an emotional bond.

Incorporating Research in Your Speech Outline

When you’re crafting a speech, the backbone of your credibility lies in solid research and data. But remember, it’s not just about piling on the facts. It’s how you weave them into your narrative that makes listeners sit up and take notice.

Selecting Credible Sources

Finding trustworthy sources is like going on a treasure hunt where not all that glitters is gold. To strike real gold, aim for academic journals or publications known for their rigorous standards. Google Scholar or industry-specific databases are great places to start your search. Be picky. Your audience can tell when you’ve done your homework versus when you’ve settled for less-than-stellar intel.

You want to arm yourself with evidence so compelling that even skeptics start nodding along. A well-chosen statistic from a reputable study does more than decorate your point—it gives it an ironclad suit of armor.

Organizing Information Effectively

Your outline isn’t just a roadmap; think of it as scaffolding that holds up your argument piece by piece. Start strong with an eye-opening factoid to hook your audience right off the bat because first impressions matter—even in speeches.

To keep things digestible, group related ideas together under clear subheadings within your outline. Stick to presenting data that backs up each key idea without wandering down tangential paths. That way, everyone stays on track.

Making Data Relatable

Sure, numbers don’t lie but they can be hard to connect to. If you plan on using stats in your speech, make them meaningful by connecting them to relatable scenarios or outcomes people care about deeply. For instance, if you’re talking health statistics, relate them back to someone’s loved ones or local hospitals. By making the personal connection for your audience, you’ll get their attention.

The trick is using these nuggets strategically throughout your talk, not dumping them all at once but rather placing each one carefully where its impact will be greatest.

Imagine your speech as a road trip. Without smooth roads and clear signs, the journey gets bumpy, and passengers might miss the scenery along the way. That’s where transitions come in. They’re like your speech’s traffic signals guiding listeners from one point to another.

Crafting Seamless Bridges Between Ideas

Transitions are more than just linguistic filler. They’re strategic connectors that carry an audience smoothly through your narrative. Start by using phrases like “on top of this” or “let’s consider,” which help you pivot naturally between points without losing momentum.

To weave these seamlessly into your outline, map out each major turn beforehand to ensure no idea is left stranded on a tangent.

Making Use of Transitional Phrases Wisely

Be cautious: overusing transitional phrases can clutter up your speech faster than rush hour traffic. Striking a balance is key—think about how often you’d want to see signposts on a highway. Enough to keep you confident but not so many that it feels overwhelming.

Pick pivotal moments for transitions when shifting gears from one major topic to another or introducing contrasting information. A little direction at critical junctures keeps everyone onboard and attentive.

Leveraging Pauses as Transition Tools

Sometimes silence speaks louder than words, and pauses are powerful tools for transitioning thoughts. A well-timed pause lets ideas resonate and gives audiences time to digest complex information before moving forward again.

This approach also allows speakers some breathing room themselves—the chance to regroup mentally before diving into their next point with renewed vigor.

Connecting Emotional Threads Throughout Your Speech

Last but not least, don’t forget emotional continuity, that intangible thread pulling heartstrings from start-to-finish. Even if topics shift drastically, maintaining an underlying emotional connection ensures everything flows together cohesively within the larger tapestry of your message.

Techniques for Emphasizing Key Points in Your Speech Outline

When you’re crafting your speech outline, shine a spotlight on what matters most so that your audience doesn’t miss your key points.

Bold and Italicize for Impact

You wouldn’t whisper your punchline in a crowded room. Similarly, why let your main ideas get lost in a sea of text? Use bold or italics to give those lines extra weight. This visual cue signals importance, so when you glance at your notes during delivery, you’ll know to emphasize those main ideas.

Analogies That Stick

A good analogy is like super glue—it makes anything stick. Weave them into your outline and watch as complex concepts become crystal clear. But remember: choose analogies that resonate with your target audience’s experiences or interests. The closer home it hits, the longer it lingers.

The Power of Repetition

If something’s important say it again. And maybe even once more after that—with flair. Repetition can feel redundant on paper, but audiences often need to hear critical messages several times before they take root.

Keep these strategies in mind when you’re ready to dive into your outline. You’ll transform those core ideas into memorable insights before you know it.

Picture this: you’re delivering a speech, and just as you’re about to reach the end, your time’s up. Ouch! Let’s make sure that never happens. Crafting an outline is not only about what to say but also how long to say it.

Finding Balance in Section Lengths

An outline isn’t just bullet points; it’s a roadmap for pacing. When outlining your speech, make sure to decide how much time you’d like to give each of your main points. You might even consider setting specific timers during rehearsals to get a real feel for each part’s duration. Generally speaking, you should allot a fairly equal amount of time for each to keep things balanced.

The Magic of Mini Milestones

To stay on track, a savvy speaker will mark time stamps or “mini milestones” on their outline. These time stamps give the speaker an idea of where should be in their speech by the time, say, 15 minutes has passed. If by checkpoint three you should be 15 minutes deep and instead you’re hitting 20 minutes, it’s time to pick up the pace or trim some fat from earlier sections. This approach helps you stay on track without having to glance at the clock after every sentence.

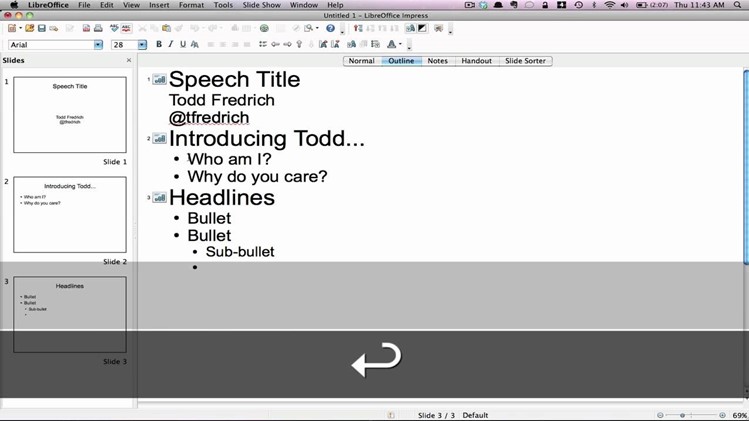

Utilizing Visual Aids and Multimedia in Your Outline

Pictures speak louder than words, especially when you’re on stage. Think about it: How many times have you sat through a presentation that felt like an eternity of endless bullet points? Now imagine if instead, there was a vibrant image or a short video clip to break up the monotony—it’s game-changing. That’s why integrating visual aids and multimedia into your speech outline isn’t just smart. It’s crucial for keeping your audience locked in.

Choosing Effective Visuals

Selecting the right visuals is not about flooding your slides with random images but finding those that truly amplify your message. Say you’re talking about climate change. In this case, a graph showing rising global temperatures can hit hard and illustrate your chosen statistic clearly. Remember, simplicity reigns supreme; one powerful image will always trump a cluttered collage.

Multimedia Magic

Videos are another ace up your sleeve. They can deliver testimonials more powerfully than quotes or transport viewers to places mere descriptions cannot reach. But be warned—timing is everything. Keep clips short and sweet because no one came to watch a movie—they came to hear you . You might highlight innovations using short video snippets, ensuring these moments serve as compelling punctuations rather than pauses in your narrative.

The Power of Sound

We often forget audio when we think multimedia, yet sound can evoke emotions and set tones subtly yet effectively. Think striking chords for dramatic effect or nature sounds for storytelling depth during environmental talks.

Audiences crave experiences they’ll remember long after they leave their seats. With well-chosen visuals and gripping multimedia elements woven thoughtfully into every section of your speech outline, you’ll give them exactly that.

Rehearsing with Your Speech Outline

When you’re gearing up to take the stage, your speech outline is a great tool to practice with. With a little preparation, you’ll give a performance that feels both natural and engaging.

Familiarizing Yourself with Content

To start off strong, get cozy with your outline’s content. Read through your outline aloud multiple times until the flow of words feels smooth. This will help make sure that when showtime comes around, you can deliver those lines without tripping over tough transitions or complex concepts.

Beyond mere memorization, understanding the heart behind each point allows you to speak from a place of confidence. You know this stuff—you wrote it. Now let’s bring that knowledge front and center in an authentic way.

Mimicking Presentation Conditions

Rehearsing under conditions similar to those expected during the actual presentation pays off big time. Are you going to stand or roam about? Will there be a podium? Think about these details and simulate them during rehearsal because comfort breeds confidence—and we’re all about boosting confidence.

If technology plays its part in your talk, don’t leave them out of rehearsals either. The last thing anyone needs is tech trouble during their talk.

Perfecting Pace Through Practice

Pacing matters big time when speaking. Use timed rehearsals to nail down timing. Adjust speed as needed but remember: clarity trumps velocity every single time.

You want people hanging onto every word, which is hard to do if you’re talking so fast they can barely make out what you’re saying. During rehearsals, find balance between pacing and comprehension; they should go hand-in-hand.

Finalizing Your Speech Outline for Presentation

You’ve poured hours into crafting your speech, shaping each word and idea with precision. Now, it’s time to tighten the nuts and bolts. Finalizing your outline isn’t just about dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s. It’s about making sure your message sticks like a perfectly thrown dart.

Reviewing Your Content for Clarity

Your first task is to strip away any fluff that might cloud your core message. Read through every point in your outline with a critical eye. Think of yourself as an editor on a mission to cut out anything that doesn’t serve a purpose. Ask yourself if you can explain each concept clearly without needing extra words or complex jargon. If not, simplify.

Strengthening Your Argument

The meat of any good presentation lies in its argument, the why behind what you’re saying. Strengthen yours by ensuring every claim has iron-clad backing—a stat here, an expert quote there. Let this be more than just facts tossed at an audience; weave them into stories they’ll remember long after they leave their seats.

Crafting Memorable Takeaways

Audiences may forget details but never how you made them feel—or think. Embed memorable takeaways throughout your outline so when folks step out into fresh air post-talk, they carry bits of wisdom with them.

This could mean distilling complex ideas down to pithy phrases or ending sections with punchy lines that resonate. It’s these golden nuggets people will mine for later reflection.

FAQs on Speech Outlines

How do you write a speech outline.

To craft an outline, jot down your main ideas, arrange them logically, and add supporting points beneath each.

What are the 3 main parts of a speech outline?

An effective speech has three core parts: an engaging introduction, a content-rich body, and a memorable conclusion.

What are the three features of a good speech outline?

A strong outline is clear, concise, and structured in logical sequence to maximize impact on listeners.

What is a working outline for a speech?

A working outline serves as your blueprint while preparing. It’s detailed but flexible enough to adjust as needed.

Crafting a speech outline is like drawing your map before the journey. It starts with structure and flows into customization for different types of talks. Remember, research and evidence are your compass—they guide you to credibility. Transitions act as bridges, connecting one idea to another smoothly. Key points? They’re landmarks so make them shine.

When delivering your speech, keep an eye on the clock and pace yourself so that every word counts.

Multimedia turns a good talk into a great show. Rehearsing polishes that gem of a presentation until it sparkles.

Last up: fine-tuning your speech outline means you step out confident, ready to deliver something memorable because this isn’t just any roadmap—it’s yours.

- Last Updated: March 5, 2024

Explore Related Resources

Learn How You Could Get Your First (Or Next) Paid Speaking Gig In 90 Days or Less

We receive thousands of applications every day, but we only work with the top 5% of speakers .

Book a call with our team to get started — you’ll learn why the vast majority of our students get a paid speaking gig within 90 days of finishing our program .

If you’re ready to control your schedule, grow your income, and make an impact in the world – it’s time to take the first step. Book a FREE consulting call and let’s get you Booked and Paid to Speak ® .

About The Speaker Lab

We teach speakers how to consistently get booked and paid to speak. Since 2015, we’ve helped thousands of speakers find clarity, confidence, and a clear path to make an impact.

Get Started

Let's connect.

Copyright ©2023 The Speaker Lab. All rights reserved.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.4: Outlining your Speech

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 135724

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Explain the principles of outlining.

- Create a formal outline.

- Explain the importance of writing for speaking.

- Create a speaking outline.

Think of your outline as the map of your speech. It is a living document that grows and takes form throughout your speech-making process. When you first draft your general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement, this is the start of your outline. Once you’ve chosen your organizational pattern, you will write out the main points of your speech and incorporate supporting material for those points from your research. You can include direct quotes from experts or paraphrase your sources, and be prepared to provide bibliographic information needed for your verbal citations in your outline document. By this point, you have a good working outline, and you can easily cut and paste information to move it around and see how it fits into the main points, subpoints, and sub-subpoints. As your outline continues to take shape, you will want to follow established principles of outlining to ensure a quality speech.

The Formal Outline

The formal outline is written in full-sentences to help you prepare for your speech because you will be speaking in full sentences. It includes the introduction and conclusion, the main content of the body, key supporting materials, citation information written into the sentences in the outline, and a references page for your speech. The formal outline also includes a title, the general purpose, specific purpose, and thesis statement. It’s important to note that an outline is not a script. While a script contains everything that will be said, an outline includes the main content. Therefore you shouldn’t include every word you’re going to say on your outline. This allows you more freedom as a speaker to adapt to your audience during your speech. Students sometimes complain about having to outline speeches or papers, but it is a skill that will help you in other contexts. Being able to break a topic down into logical divisions and then connect the information together is a valuable organizational skill which demonstrates that you can prepare for complicated tasks or that you’re prepared for meetings or interviews.

Principles of Outlining

There are principles of outlining you can follow to make your outlining process more efficient and effective. Four principles of outlining are consistency, unity, coherence, and emphasis (DuBois, 1929). In terms of consistency, you should follow standard outlining format. In standard outlining format, main points are indicated by capital roman numerals, subpoints are indicated by capital letters, and sub-subpoints are indicated by Arabic numerals. Further divisions are indicated by either lowercase letters or lowercase roman numerals.

The principle of unity means that each letter or number represents one idea. One concrete way to help reduce the amount of ideas you include per item is to limit each letter or number to one complete sentence. If you find that one subpoint has more than one idea, you can divide it into two subpoints. Limiting each component of your outline to one idea makes it easier to then plug in supporting material and helps ensure that your speech is coherent. In the following example from a speech arguing that downloading music from peer-to-peer sites should be legal, two ideas are presented as part of a main point.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs helps market new music and doesn’t hurt record sales.

The main point could be broken up into two distinct ideas that can be more fully supported.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs helps market new music.

- Downloading music using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs doesn’t hurt record sales.

Following the principle of unity should help your outline adhere to the principle of coherence, which states that there should be a logical and natural flow of ideas, with main points, subpoints, and sub-subpoints connecting to each other (Winans, 1917). Shorter phrases and keywords can make up the speaking outline, but you should write complete sentences throughout your formal outline to ensure coherence. The principle of coherence can also be met by making sure that when dividing a main point or subpoint, you include at least two subdivisions. After all, it defies logic that you could divide anything into just one part. Therefore if you have an A , you must have a B , and if you have a 1 , you must have a 2 . If you can easily think of one subpoint but are having difficulty identifying another one, that subpoint may not be robust enough to stand on its own. Determining which ideas are coordinate with each other and which are subordinate to each other will help divide supporting information into the outline (Winans, 1917). Coordinate points are on the same level of importance in relation to the thesis of the speech or the central idea of a main point. In the following example, the two main points (I, II) are coordinate with each other. The two subpoints (A, B) are also coordinate with each other. Subordinate points provide evidence or support for a main idea or thesis. In the following example, subpoint A and subpoint B are subordinate to main point II. You can look for specific words to help you determine any errors in distinguishing coordinate and subordinate points. Your points/subpoints are likely coordinate when you would connect the two statements using any of the following: and , but , yet , or , or also . In the example, the word also appears in B, which connects it, as a coordinate point, to A. The points/subpoints are likely subordinate if you would connect them using the following: since , because , in order that , to explain , or to illustrate . In the example, 1 and 2 are subordinate to A because they support that sentence.

- They conclude that the rapid increase in music downloading over the past few years does not significantly contribute to declining record sales.

- Their research even suggests that the practice of downloading music may even have a “slight positive effect on the sales of the top albums.”

- A 2010 Government Accountability Office Report also states that sampling “pirated” goods could lead consumers to buy the “legitimate” goods.

The principle of emphasis states that the material included in your outline should be engaging and balanced. As you place supporting material into your outline, choose the information that will have the most impact on your audience. Choose information that is proxemic and relevant, meaning that it can be easily related to the audience’s lives because it matches their interests or ties into current events or the local area. Remember primacy and recency discussed earlier and place the most engaging information first or last in a main point depending on what kind of effect you want to have. Also make sure your information is balanced. The outline serves as a useful visual representation of the proportions of your speech. You can tell by the amount of space a main point, subpoint, or sub-subpoint takes up in relation to other points of the same level whether or not your speech is balanced. If one subpoint is a half a page, but a main point is only a quarter of a page, then you may want to consider making the subpoint a main point. Each part of your speech doesn’t have to be equal. The first or last point may be more substantial than a middle point if you are following primacy or recency, but overall the speech should be relatively balanced.

Sample Informative Outline

Title: The Beautiful Game

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will understand the history and worldwide influence of soccer.

Thesis statement: Soccer is a game with a long history that is beloved by millions of fans all over the world.

Introduction

Attention getter: GOOOOOOOOOOOOAL! GOAL! GOAL! GOOOOOOAL!

Introduction of topic: If you’ve ever heard this excited yell coming from your television, then you probably already know that my speech today is about soccer.

Credibility and relevance: Like many of you, I played soccer on and off as a kid, but I was never really exposed to the culture of the sport. It wasn’t until recently, when I started to watch some of the World Cup games with international classmates, that I realized what I’d been missing out on. Soccer is the most popular sport in the world, but I bet that, like most Americans, it only comes on your radar every few years during the World Cup or the Olympics. If, however, you lived anywhere else in the world, soccer (or football, as it is more often called) would likely be a much larger part of your life.

Preview: I am going to talk about the history of soccer, a few famous players and teams and the worldwide influence of the sport.

Main point 1: History

Subpoint: Over 2000 years again in 206 BC, Chinese soldiers of the Han Dynasty were play Tsu-chu, kicking the ball to supplement their training regimen.

Subpoint: In 1863, the official rules of the game were created in England, called the Football Association. In 1872, the first FA cup was played and by 1888 there were 128 teams in the Association. In 1902 the International Federation of Football Associations (FIFA), and the first FIFA World Cup was played in 1930.

Subpoints: The rules of football are fairly symbol, you have 11 players on each team, and only the goalkeeper is allowed to touch the ball with hands. Each position has a name, but I won’t go into that here. The object of the game is to score a goal while keeping the opposing team from scoring a goal.

Main point 2: Famous Football Clubs

Subpoint: Manchester United based in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England founded in 1878 is one of the oldest football clubs. Nickname: Man United or Man U.

Subpoint: Barcelona FC founded in 1899. Nickname: Barca.

Subpoint: Real Madrid CF of Spain founded in 1902

Main point 3: Famous players

Subpoint: Pele is a Brazilian legend of the game, whose career spanned the 1950s, 60s and 70s, and is considered “the greatest” by FIFA.

Subpoint: Neymar is another player from Brazil who is considered one of the best footballers in the world and currently plays for Paris Saint-Germain. He is known for this football skills and colorful and flamboyant hairstyles.

Subpoint: Cristiano Ronaldo has played for three of the top FC that I just mentioned, and he one of the highest paid athletes in the world. Now, in his late thirties, he nearing the end of his career, but he is still an exciting player to watch. And he happens to have the most Instagram followers.

Main point 4: Worldwide Influence

Subpoint: Almost every country has a national football team, and every four years countries are united to compete in the World Cup, similar to the Olympics which takes place every four years.

Subpoint: Football is almost nonstop action for two 45 minute halves. Some people might say how can you watch a game where no one might score. It’s because football is more than just kicking a ball. Players play with their whole body. It’s not unusual for a player to score a goal by punching the ball in with his head.

Subpoint: People all over the world unite behind their team. In many countries, there is the culture of football, which often includes whole families watching or going to games together to cheer for their team. You can play of fun game of learning country flags during the World Cup.

Transition to conclusion and summary of importance: In conclusion, soccer (or football) is an exciting sport that has a long history and global influence.

Review of main points: It’s a sport that is played all over the world. And there are several famous football clubs and star football players to follow.

Closing statement: Cristiano Ronaldo, said “football is unpredictable” (World Cup 2022, FOX) and that is what makes it exciting to watch. Players have to have the stamina and endurance to play for 45 minutes or longer without even a water break. You only need two feet and a ball. We need to stand up and appreciate the beautiful game.”

Sample Persuasive Outline (same topic as Informative Outline above)

The following outline shows the standards for formatting and content and can serve as an example as you construct your own outline. Check with your instructor to see if he or she has specific requirements for speech outlines that may differ from what is shown here.

Title: The USA’s Neglected Sport: Soccer

General purpose: To persuade

Specific purpose: By the end of my speech, the audience will believe that soccer should be more popular in the United States.

Thesis statement: Soccer isn’t as popular in the United States as it is in the rest of the world because people do not know enough about the game; however, there are actions we can take to increase its popularity.

Credibility and relevance: Like many of you, I played soccer on and off as a kid, but I was never really exposed to the culture of the sport. It wasn’t until recently, when I started to watch some of the World Cup games with international students in my dorm, that I realized what I’d been missing out on. Soccer is the most popular sport in the world, but I bet that, like most US Americans, it only comes on your radar every few years during the World Cup or the Olympics. If, however, you lived anywhere else in the world, soccer (or football, as it is more often called) would likely be a much larger part of your life.

Preview: In order to persuade you that soccer should be more popular in the United States, I’ll explain why soccer isn’t as popular in the United States and describe some of the actions we should take to change our beliefs and attitudes about the game.

Transition: Let us begin with the problem of soccer’s unpopularity in America.

A. Although soccer has a long history as a sport, it hasn’t taken hold in the United States to the extent that it has in other countries.

- Soccer has been around in one form or another for thousands of years. The president of FIFA, which is the international governing body for soccer, was quoted in David Goldblatt’s 2008 book, The Ball is Round , as saying, “Football is as old as the world…People have always played some form of football, from its very basic form of kicking a ball around to the game it is today.”

- Basil Kane, author of the book Soccer for American Spectators , reiterates this fact when he states, “Nearly every society at one time or another claimed its own form of kicking game.”

Transition: Although soccer has many problems that it would need to overcome to be more popular in the United States, I think there are actions we can take now to change our beliefs and attitudes about soccer in order to give it a better chance.

B. Sports fans in the United States already have lots of options when it comes to playing and watching sports.

- Our own “national sports” such as football, basketball, and baseball take up much of our time and attention, which may prevent people from engaging in an additional sport.

- Statistics unmistakably show that soccer viewership is low as indicated by the much-respected Pew Research group, which reported in 2006 that only 4 percent of adult US Americans they surveyed said that soccer was their favorite sport to watch.

a. Comparatively, 34 percent of those surveyed said that football was their favorite sport to watch.

b. In fact, soccer just barely beat out ice skating, with 3 percent of the adults surveyed indicating that as their favorite sport to watch.

C. The attitudes and expectations of sports fans in the United States also prevent soccer’s expansion into the national sports consciousness.

- One reason Americans don’t enjoy soccer as much as other sports is due to our shortened attention span, which has been created by the increasingly fast pace of our more revered sports like football and basketball.

a. According to the 2009 article from BleacherReport.com, “An American Tragedy: Two Reasons Why We Don’t Like Soccer,” the average length of a play in the NFL is six seconds, and there is a scoring chance in the NBA every twenty-four seconds.

b. This stands in stark comparison to soccer matches, which are played in two forty-five-minute periods with only periodic breaks in play.

D. Our lack of attention span isn’t the only obstacle that limits our appreciation for soccer; we are also set in our expectations.

- The BleacherReport article also points out that unlike with football, basketball, and baseball—all sports in which the United States has most if not all the best teams in the world—we know that the best soccer teams in the world aren’t based in the United States.

- We also expect that sports will offer the same chances to compare player stats and obsess over data that we get from other sports, but as Chad Nielsen of ESPN.com states, “There is no quantitative method to compare players from different leagues and continents.”

- Last, as legendary sports writer Frank Deford wrote in a 2012 article on Sports Illustrated ’s website, Americans don’t like ties in sports, and 30 percent of all soccer games end tied, as a draw, deadlocked, or nil-nil.

Transition: As US Americans, we can start to enjoy soccer more if we better understand why the rest of the world loves it so much.

E. Soccer is the most popular sport in the world, and there have to be some good reasons that account for this status.

- As was mentioned earlier, Chad Nielsen of ESPN.com notes that American sports fans can’t have the same stats obsession with soccer that they do with baseball or football, but fans all over the world obsess about their favorite teams and players.

a. Fans argue every day, in bars and cafés from Baghdad to Bogotá, about statistics for goals and assists, but as Nielsen points out, with the game of soccer, such stats still fail to account for varieties of style and competition.

b. So even though the statistics may be different, bonding over or arguing about a favorite team or player creates communities of fans that are just as involved and invested as even the most loyal team fans in the United States.

2. Additionally, Americans can start to realize that some of the things we might initially find off putting about the sport of soccer are actually some of its strengths.

a. The fact that soccer statistics aren’t poured over and used to make predictions makes the game more interesting.

b. The fact that the segments of play in soccer are longer and the scoring lower allows for the game to have a longer arc, meaning that anticipation can build and that a game might be won or lost by only one goal after a long and even-matched game.

E. We can also begin to enjoy soccer more if we view it as an additional form of entertainment.

- As Americans who like to be entertained, we can seek out soccer games in many different places.

a. There is most likely a minor or even a major league soccer stadium team within driving distance of where you live.

b. You can also go to soccer games at your local high school, college, or university.

2. We can also join the rest of the world in following some of the major soccer celebrities—David Beckham is just the tip of the iceberg.

3. Getting involved in soccer can also help make our society more fit and healthy.

F. Soccer can easily be the most athletic sport available to Americans.

- In just one game, the popular soccer player Gennaro Gattuso was calculated to have run about 6.2 miles, says Carl Bialik, a numbers expert who writes for The Wall Street Journal .

- With the growing trend of obesity in America, getting involved in soccer promotes more running and athletic ability than baseball, for instance, could ever provide.

a. A press release on FIFA’s official website notes that one hour of soccer three times a week has been shown in research to provide significant physical benefits.

b. If that’s not convincing enough, the website ScienceDaily.com reports that the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports published a whole special issue titled Football for Health that contained fourteen articles supporting the health benefits of soccer.

G. Last, soccer has been praised for its ability to transcend language, culture, class, and country.

- The nongovernmental organization Soccer for Peace seeks to use the worldwide popularity of soccer as a peacemaking strategy to bridge the divides of race, religion, and socioeconomic class.

- According to their official website, the organization just celebrated its ten-year anniversary in 2012.

a. Over those ten years the organization has focused on using soccer to bring together people of different religious faiths, particularly people who are Jewish and Muslim.

b. In 2012, three first-year college students, one Christian, one Jew, and one Muslim, dribbled soccer balls for 450 miles across the state of North Carolina to help raise money for Soccer for Peace.

3. A press release on the World Association of Nongovernmental Organizations’s official website states that from the dusty refugee camps of Lebanon to the upscale new neighborhoods in Buenos Aires, “soccer turns heads, stops conversations, causes breath to catch, and stirs hearts like virtually no other activity.”

Transition to conclusion and summary of importance: In conclusion, soccer is a sport that has a long history, can help you get healthy, and can bring people together.

Review of main points: Now that you know some of the obstacles that prevent soccer from becoming more popular in the United States and several actions we can take to change our beliefs and attitudes about soccer, I hope you agree with me that it’s time for the United States to join the rest of the world in welcoming soccer into our society.

Closing statement: The article from BleacherReport.com that I cited earlier closes with the following words that I would like you to take as you leave here today: “We need to learn that just because there is no scoring chance that doesn’t mean it is boring. We need to see that soccer is not for a select few, but for all. We only need two feet and a ball. We need to stand up and appreciate the beautiful game.”

Araos, C. (2009, December 10). An American tragedy: Two reasons why we don’t like soccer. Bleacher Report: World Football . Retrieved from http://bleacherreport.com/articles/306338-an-american-tragedy-the-two-reasons-why-we-dont-like-soccer

Bialik, C. (2007, May 23). Tracking how far soccer players run. WSJ Blogs: The Numbers Guy . Retrieved from http://blogs.wsj.com/numbersguy/tracking-how-far-soccer-players-run-112

Deford, F. (2012, May 16). Americans don’t like ties in sports. SI.com : Viewpoint. Retrieved from sportsillustrated.cnn.com/201.ies/index.html

FIFA.com (2007, September 6). Study: Playing football provides health benefits for all. Retrieved from http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/footballdevelopment/medical/news/newsid=589317/index.html

Goldblatt, D. (2008). The ball is round: A global history of soccer . New York, NY: Penguin.

Kane, B. (1970). Soccer for American spectators: A fundamental guide to modern soccer . South Brunswick, NJ: A. S. Barnes.

Nielsen, C. (2009, May 27). “What I do is play soccer.” ESPN . Retrieved from http://sports.espn.go.com/espn/news/story?id=4205057

Pew Research Center. (2006, June 14). Americans to rest of world: Soccer not really our thing. Pew Research Center . Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/pubs/315/americans-to-rest-of-world-soccer-not-really-our-thing

ScienceDaily.com. (2010, April 7). Soccer improves health, fitness, and social abilities. ScienceDaily.com: Science news . Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/04/100406093524.htm

Selle, R. R. (n.d.). Soccer for peace. Wango.org: News . Retrieved from http://www.wango.org/news/news/psmp.htm

Soccer For Peace. (2012). Kicking across Carolina. SFP news . Retrieved from http://www.soccerforpeace.com/2012-10-03-17-18-08/sfp-news/44-kicking-across-carolina.html

Examples of APA Formatting for References

The citation style of the American Psychological Association (APA) is most often used in communication studies when formatting research papers and references. The following examples are formatted according to the sixth edition of the APA Style Manual. Links are included to the OWL Purdue website, which is one of the most credible online sources for APA format. Of course, to get the most accurate information, it is always best to consult the style manual directly, which can be found in your college or university’s library.

For more information on citing books in APA style on your references page, visit http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/08 .

Single Author

Two Authors

Warren, J. T., & Fassett, D. L. (2011). Communication: A critical/cultural introduction . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Chapter from Edited Book

Mumby, D. K. (2011). Power and ethics. In G. Cheney, S. May, & D. Munshi (Eds.), The handbook of communication ethics (pp. 84–98). New York, NY: Routledge.

Periodicals

For more information on citing articles from periodicals in APA style on your references page, visit http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/07 .

Huang, L. (2011, August 1). The death of English (LOL). Newsweek, 152 (6), 8.

Kornblum, J. (2007, October 23). Privacy? That’s old-school: Internet generation views openness in a different way. USA Today , 1D–2D.

Journal Article

Bodie, G. D. (2012). A racing heart, rattling knees, and ruminative thoughts: Defining, explaining, and treating public speaking anxiety. Communication Education, 59 (1), 70–105.

Online Sources

For more information on citing articles from online sources in APA style on your references page, visit http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/10 .

Online Newspaper Article

Perman, C. (2011, September 8). Bad economy? A good time for a steamy affair. USA Today . Retrieved from www.usatoday.com/money/economy/story/2011-09-10/economy-affairs-divorce-marriage/50340948/1

Online News Website

Fraser, C. (2011, September 22). The women defying France’s full-face veil ban. BBC News . Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-15023308

Online Magazine

Cullen, L. T. (2007, April 26). Employee diversity training doesn’t work. Time . Retrieved from www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1615183,00.html

Government Document or Report Retrieved Online

Pew Research Center. (2010, November 18). The decline of marriage and rise of new families. Retrieved from pewsocialtrends.org/files/201.0-families.pdf

Kwintessential. (n.d.). Cross cultural business blunders. Retrieved from www.kwintessential.co.uk/cult.-blunders.html

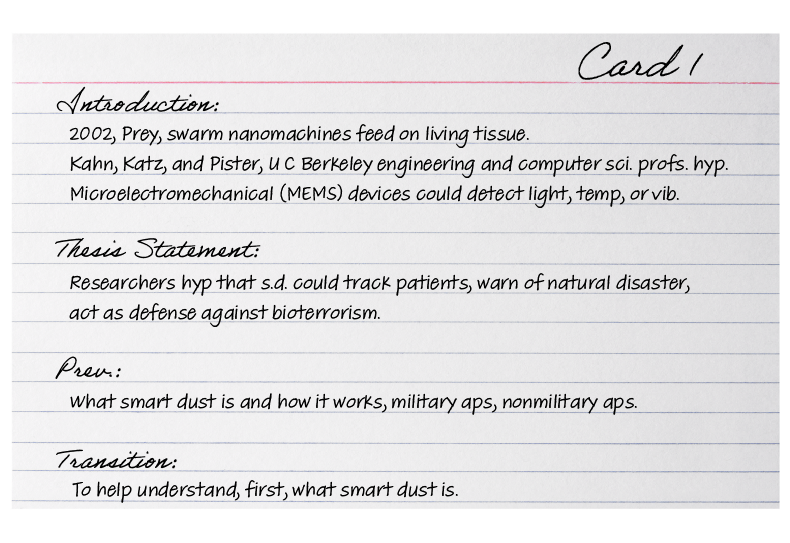

The Speaking Outline

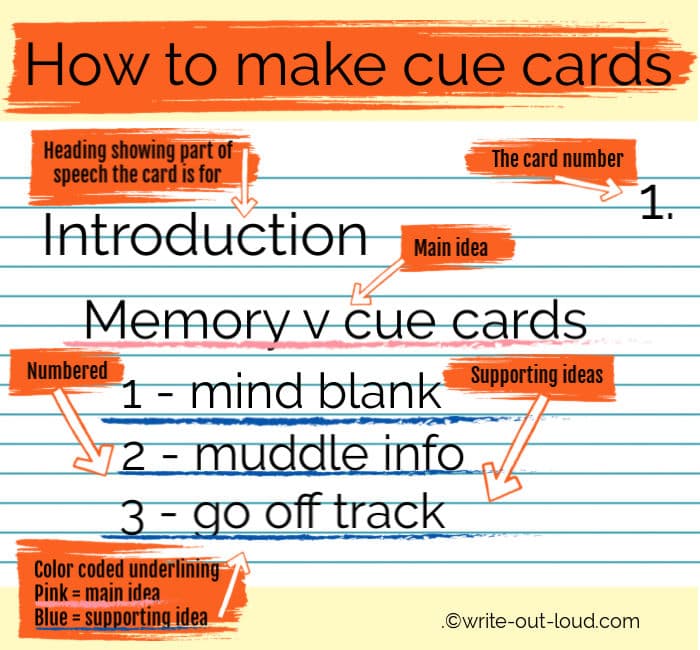

The formal outline is a full-sentence outline that helps as you prepare for your speech, and the speaking outline is a keyword and phrase outline that helps you deliver your speech. While the formal outline is important to ensure that your content is coherent and your ideas are balanced and expressed clearly, the speaking outline helps you get that information out to the audience. Make sure you budget time in your speech preparation to work on the speaking outline. Skimping on the speaking outline will show in your delivery.

You may convert your formal outline into a speaking outline using a computer program. I often resave a file and then reformat the text so it’s more conducive to referencing while actually speaking to an audience. You may also choose, or be asked to, create a speaking outline on note cards. Note cards are a good option when you want to have more freedom to gesture or know you won’t have a lectern on which to place notes printed on full sheets of paper. In either case, this entails converting the full-sentence outline to a keyword or key-phrase outline. Speakers will need to find a balance between having too much or too little content on their speaking outlines. You want to have enough information to prevent fluency hiccups as you stop to mentally retrieve information, but you don’t want to have so much information that you read your speech, which lessens your eye contact and engagement with the audience. Budgeting sufficient time to work on your speaking outline will allow you to practice your speech with different amounts of notes to find what works best for you. Since the introduction and conclusion are so important, it may be useful to include notes to ensure that you remember to accomplish all the objectives of each.

Aside from including important content on your speaking outline, you may want to include speaking cues. Speaking cues are reminders designed to help your delivery. You may write “(PAUSE)” before and after your preview statement to help you remember that important nonverbal signpost. You might also write “(MAKE EYE CONTACT)” as a reminder not to read unnecessarily from your cards. Overall, my advice is to make your speaking outline work for you. It’s your last line of defense when you’re in front of an audience, so you want it to help you, not hurt you.

Writing for Speaking

As you compose your outlines, write in a way that is natural for you to speak but also appropriate for the expectations of the occasion. Since we naturally speak with contractions, write them into your formal and speaking outlines. You should begin to read your speech aloud as you are writing the formal outline. As you read each section aloud, take note of places where you had difficulty saying a word or phrase or had a fluency hiccup, then go back to those places and edit them to make them easier for you to say. This will make you more comfortable with the words in front of you while you are speaking, which will improve your verbal and nonverbal delivery.

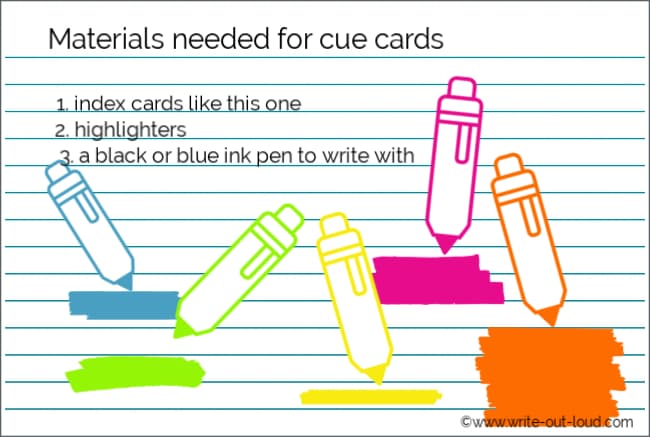

Tips for Note Cards

- The 4 × 6 inch index cards provide more space and are easier to hold and move than 3.5 × 5 inch cards.

- Find a balance between having so much information on your cards that you are tempted to read from them and so little information that you have fluency hiccups and verbal fillers while trying to remember what to say.

- Use bullet points on the left-hand side rather than writing in paragraph form, so your eye can easily catch where you need to pick back up after you’ve made eye contact with the audience. Skipping a line between bullet points may also help.

- Include all parts of the introduction/conclusion and signposts for backup.

- Include key supporting material and wording for verbal citations.

- Only write on the front of your cards.

- Do not have a sentence that carries over from one card to the next (can lead to fluency hiccups).

- If you have difficult-to-read handwriting, you may type your speech and tape or glue it to your cards. Use a font that’s large enough for you to see and be neat with the glue or tape so your cards don’t get stuck together.

- Include cues that will help with your delivery. Highlight transitions, verbal citations, or other important information. Include reminders to pause, slow down, breathe, or make eye contact.

- Your cards should be an extension of your body, not something to play with. Don’t wiggle, wring, flip through, or slap your note cards.

Key Takeaways

- The formal outline is a full-sentence outline that helps you prepare for your speech and includes the introduction and conclusion, the main content of the body, citation information written into the sentences of the outline, and a references page.

- The principles of outlining include consistency, unity, coherence, and emphasis.

- Coordinate points in an outline are on the same level of importance in relation to the thesis of the speech or the central idea of a main point. Subordinate points provide evidence for a main idea or thesis.

- The speaking outline is a keyword and phrase outline that helps you deliver your speech and can include speaking cues like “pause,” “make eye contact,” and so on.

- Write your speech in a manner conducive to speaking. Use contractions, familiar words, and phrases that are easy for you to articulate. Reading your speech aloud as you write it can help you identify places that may need revision to help you more effectively deliver your speech.

- What are some practical uses for outlining outside of this class? Which of the principles of outlining do you think would be most important in the workplace and why?

- Identify which pieces of information you may use in your speech are coordinate with each other and subordinate.

- Read aloud what you’ve written of your speech and identify places that can be reworded to make it easier for you to deliver.

DuBois, W. C., Essentials of Public Speaking (New York: Prentice Hall, 1929), 104.

Winans, J. A., Public Speaking (New York: Century, 1917), 407.

Module 4: Organizing and Outlining

Outlining your speech.

Most speakers and audience members would agree that an organized speech is both easier to present as well as more persuasive. Public speaking teachers especially believe in the power of organizing your speech, which is why they encourage (and often require) that you create an outline for your speech. Outlines , or textual arrangements of all the various elements of a speech, are a very common way of organizing a speech before it is delivered. Most extemporaneous speakers keep their outlines with them during the speech as a way to ensure that they do not leave out any important elements and to keep them on track. Writing an outline is also important to the speechwriting process since doing so forces the speakers to think about the main points and sub-points, the examples they wish to include, and the ways in which these elements correspond to one another. In short, the outline functions both as an organization tool and as a reference for delivering a speech.

Outline Types

“Alpena Mayor Carol Shafto Speaks at 2011 Michigan Municipal League Convention” by Michigan Municipal League. CC-BY-ND .

There are two types of outlines. The first outline you will write is called the preparation outline . Also called a working, practice, or rough outline, the preparation outline is used to work through the various components of your speech in an inventive format. Stephen E. Lucas [1] put it simply: “The preparation outline is just what its name implies—an outline that helps you prepare the speech” (p. 248). When writing the preparation outline, you should focus on finalizing the purpose and thesis statements, logically ordering your main points, deciding where supporting material should be included, and refining the overall organizational pattern of your speech. As you write the preparation outline, you may find it necessary to rearrange your points or to add or subtract supporting material. You may also realize that some of your main points are sufficiently supported while others are lacking. The final draft of your preparation outline should include full sentences, making up a complete script of your entire speech. In most cases, however, the preparation outline is reserved for planning purposes only and is translated into a speaking outline before you deliver the speech.

A speaking outline is the outline you will prepare for use when delivering the speech. The speaking outline is much more succinct than the preparation outline and includes brief phrases or words that remind the speakers of the points they need to make, plus supporting material and signposts. [2] The words or phrases used on the speaking outline should briefly encapsulate all of the information needed to prompt the speaker to accurately deliver the speech. Although some cases call for reading a speech verbatim from the full-sentence outline, in most cases speakers will simply refer to their speaking outline for quick reminders and to ensure that they do not omit any important information. Because it uses just words or short phrases, and not full sentences, the speaking outline can easily be transferred to index cards that can be referenced during a speech.

Outline Structure

Because an outline is used to arrange all of the elements of your speech, it makes sense that the outline itself has an organizational hierarchy and a common format. Although there are a variety of outline styles, generally they follow the same pattern. Main ideas are preceded by Roman numerals (I, II, III, etc.). Sub-points are preceded by capital letters (A, B, C, etc.), then Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.), and finally lowercase letters (a, b, c, etc.). Each level of subordination is also differentiated from its predecessor by indenting a few spaces. Indenting makes it easy to find your main points, sub-points, and the supporting points and examples below them. Since there are three sections to your speech— introduction, body, and conclusion— your outline needs to include all of them. Each of these sections is titled and the main points start with Roman numeral I.

Outline Formatting Guide

Title: Organizing Your Public Speech

Topic: Organizing public speeches

Specific Purpose Statement: To inform listeners about the various ways in which they can organize their public speeches.

Thesis Statement: A variety of organizational styles can used to organize public speeches.

Introduction Paragraph that gets the attention of the audience, establishes goodwill with the audience, states the purpose of the speech, and previews the speech and its structure.

(Transition)

I. Main point

A. Sub-point B. Sub-point C. Sub-point

1. Supporting point 2. Supporting point

Conclusion Paragraph that prepares the audience for the end of the speech, presents any final appeals, and summarizes and wraps up the speech.

Bibliography

In addition to these formatting suggestions, there are some additional elements that should be included at the beginning of your outline: the title, topic, specific purpose statement, and thesis statement. These elements are helpful to you, the speechwriter, since they remind you what, specifically, you are trying to accomplish in your speech. They are also helpful to anyone reading and assessing your outline since knowing what you want to accomplish will determine how they perceive the elements included in your outline. Additionally, you should write out the transitional statements that you will use to alert audiences that you are moving from one point to another. These are included in parentheses between main points. At the end of the outlines, you should include bibliographic information for any outside resources you mention during the speech. These should be cited using whatever citations style your professor requires. The textbox entitled “Outline Formatting Guide” provides an example of the appropriate outline format.

If you do not change direction, you may end up where you are heading. – Lao Tzu

Preparation Outline

This chapter contains the preparation and speaking outlines for a short speech the author of this chapter gave about how small organizations can work on issues related to climate change (see appendices). In this example, the title, specific purpose, thesis, and list of visual aids precedes the speech. Depending on your instructor’s requirements, you may need to include these details plus additional information. It is also a good idea to keep these details at the top of your document as you write the speech since they will help keep you on track to developing an organized speech that is in line with your specific purpose and helps prove your thesis. At the end of the chapter, in Appendix A, you can find a full length example of a Preparation (Full Sentence) Outline.

Speaking Outline

In Appendix B, the Preparation Outline is condensed into just a few short key words or phrases that will remind speakers to include all of their main points and supporting information. The introduction and conclusion are not included since they will simply be inserted from the Preparation Outline. It is easy to forget your catchy attention-getter or final thoughts you have prepared for your audience, so it is best to include the full sentence versions even in your speaking outline.

Using the Speaking Outline

“TAG speaks of others first” by Texas Military Forces. CC-BY-ND .

Once you have prepared the outline and are almost ready to give your speech, you should decide how you want to format your outline for presentation. Many speakers like to carry a stack of papers with them when they speak, but others are more comfortable with a smaller stack of index cards with the outline copied onto them. Moreover, speaking instructors often have requirements for how you should format the speaking outline. Whether you decide to use index cards or the printed outline, here are a few tips. First, write large enough so that you do not have to bring the cards or pages close to your eyes to read them. Second, make sure you have the cards/pages in the correct order and bound together in some way so that they do not get out of order. Third, just in case the cards/pages do get out of order (this happens too often!), be sure that you number each in the top right corner so you can quickly and easily get things organized. Fourth, try not to fiddle with the cards/pages when you are speaking. It is best to lay them down if you have a podium or table in front of you. If not, practice reading from them in front of a mirror. You should be able to look down quickly, read the text, and then return to your gaze to the audience.

Any intelligent fool can make things bigger and more complex… It takes a touch of genius – and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction. – Albert Einstein

- Lucas, Stephen E. (2004). The art of public speaking (8th edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ↵

- Beebe, S. A. & Beebe, S. J. (2003). The public speaking handbook (5th edition). Boston: Pearson. ↵

- Chapter 8 Outlining Your Speech. Authored by : Joshua Trey Barnett. Provided by : University of Indiana, Bloomington, IN. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html . Project : The Public Speaking Project. License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Alpena Mayor Carol Shafto Speaks at 2011 Michigan Municipal League Convention. Authored by : Michigan Municipal League. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/aunJMR . License : CC BY-ND: Attribution-NoDerivatives

- TAG speaks of others first. Authored by : Texas Military Forces. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/texasmilitaryforces/5560449970/ . License : CC BY-ND: Attribution-NoDerivatives

Privacy Policy

My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

How to Write an Outline for a Persuasive Speech, with Examples

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

Persuasive speeches are one of the three most used speeches in our daily lives. Persuasive speech is used when presenters decide to convince their presentation or ideas to their listeners. A compelling speech aims to persuade the listener to believe in a particular point of view. One of the most iconic examples is Martin Luther King’s ‘I had a dream’ speech on the 28th of August 1963.

In this article:

What is Persuasive Speech?

Here are some steps to follow:, persuasive speech outline, final thoughts.

Persuasive speech is a written and delivered essay to convince people of the speaker’s viewpoint or ideas. Persuasive speaking is the type of speaking people engage in the most. This type of speech has a broad spectrum, from arguing about politics to talking about what to have for dinner. Persuasive speaking is highly connected to the audience, as in a sense, the speaker has to meet the audience halfway.

Persuasive Speech Preparation

Persuasive speech preparation doesn’t have to be difficult, as long as you select your topic wisely and prepare thoroughly.

1. Select a Topic and Angle

Come up with a controversial topic that will spark a heated debate, regardless of your position. This could be about anything. Choose a topic that you are passionate about. Select a particular angle to focus on to ensure that your topic isn’t too broad. Research the topic thoroughly, focussing on key facts, arguments for and against your angle, and background.

2. Define Your Persuasive Goal

Once you have chosen your topic, it’s time to decide what your goal is to persuade the audience. Are you trying to persuade them in favor of a certain position or issue? Are you hoping that they change their behavior or an opinion due to your speech? Do you want them to decide to purchase something or donate money to a cause? Knowing your goal will help you make wise decisions about approaching writing and presenting your speech.

3. Analyze the Audience

Understanding your audience’s perspective is critical anytime that you are writing a speech. This is even more important when it comes to a persuasive speech because not only are you wanting to get the audience to listen to you, but you are also hoping for them to take a particular action in response to your speech. First, consider who is in the audience. Consider how the audience members are likely to perceive the topic you are speaking on to better relate to them on the subject. Grasp the obstacles audience members face or have regarding the topic so you can build appropriate persuasive arguments to overcome these obstacles.

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

4. Build an Effective Persuasive Argument

Once you have a clear goal, you are knowledgeable about the topic and, have insights regarding your audience, you will be ready to build an effective persuasive argument to deliver in the form of a persuasive speech.

Start by deciding what persuasive techniques are likely to help you persuade your audience. Would an emotional and psychological appeal to your audience help persuade them? Is there a good way to sway the audience with logic and reason? Is it possible that a bandwagon appeal might be effective?

5. Outline Your Speech

Once you know which persuasive strategies are most likely to be effective, your next step is to create a keyword outline to organize your main points and structure your persuasive speech for maximum impact on the audience.

Start strong, letting your audience know what your topic is, why it matters and, what you hope to achieve at the end of your speech. List your main points, thoroughly covering each point, being sure to build the argument for your position and overcome opposing perspectives. Conclude your speech by appealing to your audience to act in a way that will prove that you persuaded them successfully. Motivation is a big part of persuasion.

6. Deliver a Winning Speech

Select appropriate visual aids to share with your audiences, such as graphs, photos, or illustrations. Practice until you can deliver your speech confidently. Maintain eye contact, project your voice and, avoid using filler words or any form of vocal interference. Let your passion for the subject shine through. Your enthusiasm may be what sways the audience.

Topic: What topic are you trying to persuade your audience on?

Specific Purpose:

Central idea:

- Attention grabber – This is potentially the most crucial line. If the audience doesn’t like the opening line, they might be less inclined to listen to the rest of your speech.

- Thesis – This statement is used to inform the audience of the speaker’s mindset and try to get the audience to see the issue their way.

- Qualifications – Tell the audience why you are qualified to speak about the topic to persuade them.

After the introductory portion of the speech is over, the speaker starts presenting reasons to the audience to provide support for the statement. After each reason, the speaker will list examples to provide a factual argument to sway listeners’ opinions.

- Example 1 – Support for the reason given above.

- Example 2 – Support for the reason given above.

The most important part of a persuasive speech is the conclusion, second to the introduction and thesis statement. This is where the speaker must sum up and tie all of their arguments into an organized and solid point.

- Summary: Briefly remind the listeners why they should agree with your position.

- Memorable ending/ Audience challenge: End your speech with a powerful closing thought or recommend a course of action.

- Thank the audience for listening.

Persuasive Speech Outline Examples

Topic: Walking frequently can improve both your mental and physical health.

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to start walking to improve their health.

Central idea: Regular walking can improve your mental and physical health.

Life has become all about convenience and ease lately. We have dishwashers, so we don’t have to wash dishes by hand with electric scooters, so we don’t have to paddle while riding. I mean, isn’t it ridiculous?

Today’s luxuries have been welcomed by the masses. They have also been accused of turning us into passive, lethargic sloths. As a reformed sloth, I know how easy it can be to slip into the convenience of things and not want to move off the couch. I want to persuade you to start walking.

Americans lead a passive lifestyle at the expense of their own health.

- This means that we spend approximately 40% of our leisure time in front of the TV.

- Ironically, it is also reported that Americans don’t like many of the shows that they watch.

- Today’s studies indicate that people were experiencing higher bouts of depression than in the 18th and 19th centuries, when work and life were considered problematic.

- The article reports that 12.6% of Americans suffer from anxiety, and 9.5% suffer from severe depression.

- Present the opposition’s claim and refute an argument.

- Nutritionist Phyllis Hall stated that we tend to eat foods high in fat, which produces high levels of cholesterol in our blood, which leads to plaque build-up in our arteries.

- While modifying our diet can help us decrease our risk for heart disease, studies have indicated that people who don’t exercise are at an even greater risk.

In closing, I urge you to start walking more. Walking is a simple, easy activity. Park further away from stores and walk. Walk instead of driving to your nearest convenience store. Take 20 minutes and enjoy a walk around your neighborhood. Hide the TV remote, move off the couch and, walk. Do it for your heart.

Thank you for listening!

Topic: Less screen time can improve your sleep.

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to stop using their screens two hours before bed.

Central idea: Ceasing electronics before bed will help you achieve better sleep.

Who doesn’t love to sleep? I don’t think I have ever met anyone who doesn’t like getting a good night’s sleep. Sleep is essential for our bodies to rest and repair themselves.

I love sleeping and, there is no way that I would be able to miss out on a good night’s sleep.

As someone who has had trouble sleeping due to taking my phone into bed with me and laying in bed while entertaining myself on my phone till I fall asleep, I can say that it’s not the healthiest habit, and we should do whatever we can to change it.

- Our natural blue light source is the sun.

- Bluelight is designed to keep us awake.

- Bluelight makes our brain waves more active.

- We find it harder to sleep when our brain waves are more active.

- Having a good night’s rest will improve your mood.

- Being fully rested will increase your productivity.

Using electronics before bed will stimulate your brainwaves and make it more difficult for you to sleep. Bluelight tricks our brains into a false sense of daytime and, in turn, makes it more difficult for us to sleep. So, put down those screens if you love your sleep!

Thank the audience for listening

A persuasive speech is used to convince the audience of the speaker standing on a certain subject. To have a successful persuasive speech, doing the proper planning and executing your speech with confidence will help persuade the audience of your standing on the topic you chose. Persuasive speeches are used every day in the world around us, from planning what’s for dinner to arguing about politics. It is one of the most widely used forms of speech and, with proper planning and execution, you can sway any audience.

How to Write the Most Informative Essay

How to Craft a Masterful Outline of Speech

Leave a Comment

I accept the Privacy Policy

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities

Vivamus integer non suscipit taciti mus etiam at primis tempor sagittis euismod libero facilisi.

© 2024 My Speech Class

7.4 Outlining Your Speech

Most speakers and audience members would agree that an organized speech is both easier to present as well as more persuasive. Public speaking teachers especially believe in the power of organizing your speech, which is why they encourage (and often require) that you create an outline for your speech. Outlines, or textual arrangements of all the various elements of a speech, are a very common way of organizing a speech before it is delivered. Most extemporaneous speakers keep their outlines with them during the speech as a way to ensure that they do not leave out any important elements and to keep them on track. Writing an outline is also important to the speechwriting process since doing so forces the speakers to think about the main ideas, known as main points, and subpoints, the examples they wish to include, and the ways in which these elements correspond to one another. In short, the outline functions both as an organization tool and as a reference for delivering a speech.

Outline Types

There are two types of outlines, the preparation outline and the speaking outline.

Preparation Outline

The first outline you will write is called the preparation outline . Also called a skeletal, working, practice, or rough outline, the preparation outline is used to work through the various components of your speech in an organized format. Stephen E. Lucas (2004) put it simply: “The preparation outline is just what its name implies—an outline that helps you prepare the speech.” When writing the preparation outline, you should focus on finalizing the specific purpose and thesis statement, logically ordering your main points, deciding where supporting material should be included, and refining the overall organizational pattern of your speech. As you write the preparation outline, you may find it necessary to rearrange your points or to add or subtract supporting material. You may also realize that some of your main points are sufficiently supported while others are lacking. The final draft of your preparation outline should include full sentences. In most cases, however, the preparation outline is reserved for planning purposes only and is translated into a speaking outline before you deliver the speech. Keep in mind though, even a full sentence outline is not an essay.

Speaking Outline