Goal-Setting Is Linked to Higher Achievement

Five research-based ways to help children and teens attain their goals..

Posted March 14, 2018 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Motivation?

- Find a therapist near me

If you are an employed adult, you know that most organizations have written goals and objectives. That’s because goal-setting is a common practice in the workplace—and for good reason. Written goals provide a road map by which employees can measure their efforts and see how they contribute to the success of work teams and ultimately, to their companies.

In the same way, goal-setting helps motivate athletes, entrepreneurs, and individuals to achieve at higher levels of difficulty.

But goal-setting isn’t just for adults. In fact, being goal-oriented is a critical part of how children learn to become resourceful, which is defined as one’s ability to find and use available resources to solve problems and shape the future.

“Goal setters see future possibilities and the big picture,” says Rick McDaniel in a Huffington Post article . He discusses the important difference between being a goal setter and problem solver, the latter often getting bogged down in roadblocks. “Goal setters,” he says, “are comfortable with risk, prefer innovation , and are energized by change.”

Research has uncovered many key aspects of goal setting theory and its link to success (Kleingeld, et al, 2011). Setting goals is linked with self-confidence , motivation, and autonomy (Locke & Lathan, 2006). A 2015 study by psychologist Gail Matthews showed when people wrote down their goals, they were 33 percent more successful in achieving them than those who formulated outcomes in their heads.

Children learn to be resourceful through the practice of being goal-directed. In an article at Edutopia , teachers learn that fostering resourcefulness involves encouraging students to plan, strategize, prioritize, set goals, seek resources, and monitor their progress.

In similar ways, parents teach resourcefulness when they walk beside children through the everyday practice of being goal-directed rather than attempting to set objectives and problem-solving for kids.

The common approach that applies to both parents and educators is to involve children in their own goal-setting and decision-making . This promotes independence and collaboration with adults simultaneously.

The following strategies apply the research on goal-setting at home, in the classroom, or on the sports field.

Five Ways to Help Children Set and Achieve Goals

Children and teens become effective goal-setters when they understand and develop five action-oriented behaviors and incorporate these actions with each goal set.

- Put goals in writing. Goals that are written are concrete and motivational. Making progress toward written goals increases feelings of success and well-being. Using a goal-setting template can help children track their successes. A goal-setting smartphone app may motivate tech-savvy children even more. Some apps have gaming features that make goal-setting a fun way to achieve results and build new habits.

- Self-commit. For a goal to be motivating to a child, it must give meaning to a mental or physical action to which a child feels committed. This self-commitment becomes a key element in self-regulation , a child’s ability to monitor, control, and alter his own behaviors. This doesn’t mean that parents or teachers should not be involved in goal-setting. In fact, adults can serve as goal facilitators—helping kids see options, asking core questions, and providing supportive feedback.

- Be specific. Goals must be much more specific than raising a grade or improving performance on the soccer field. Here’s a simple formula. 1) I will [raise my grade in algebra from a C to a B]; 2) By doing what? [regular homework, and spending time with an online algebra program or game]; 3) When? How? With Whom? [increase daily algebra homework by 15 minutes to include a fun online interactive algebra practice; spend 15 fewer minutes on social media ; get support from teacher/tutor for things that are not understood]; 4) Measured by [increased time spent; improved weekly test scores].

- Stretch for difficulty. Goals should always be challenging enough to be attainable, but not so challenging that they become sources of major setbacks. When working with a child on goal-setting, listen to what they think they can achieve rather than what you want them to achieve.

- Seek feedback and support. Part of the fun and motivation of setting goals is working on them in a supportive group environment. Even though goals are often individual in nature, children should be able to recognize how their goal is tied to their family values, the aspirations of a sports team, or the aim of a specific curriculum. When they understand this connection, they feel more open to seeking feedback and receiving support from adults. When goals are achieved, it’s time to celebrate with others!

Kleingeld, A., van Mierlo, H., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1289-1304.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 15(5), 265-268.

Matthews, G. (2015). Goal Research Summary. Paper presented at the 9th Annual International Conference of the Psychology Research Unit of Athens Institute for Education and Research (ATINER), Athens, Greece.

Marilyn Price-Mitchell, Ph.D., is an Institute for Social Innovation Fellow at Fielding Graduate University and author of Tomorrow’s Change Makers.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

5 Ways to Set More Achievable Goals

- Rakshitha Arni Ravishankar

- Kelsey Alpaio

#1 Connect every goal to a “why.”

Setting goals is a meaningful exercise. Still, so many of us struggle to achieve the goals we set out for ourselves. Here are five ways to set more attainable goals:

- Connect your every goal to a “why.” When you spend time understanding the “why” that’s driving your actions, it’s easier to avoid distractions and focus on pursuing your goal.

- Break your goals down. Instead of setting one big goal, break them down into smaller goals that you can accomplish every day.

- Schedule “buffer time” for your goals and increase your estimated deadline by 25%.

- Focus on continuation, not improvement. Embrace all the things you’ve already started and would like to continue or build upon with time.

- Don’t dwell on past failures. Know that it’s normal and everyone goes through a cycle of ups and down.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Setting goals is a deeply meaningful exercise. Research shows that it motivates us , gives us a sense of purpose, and helps us feel accomplished.

- RR Rakshitha Arni Ravishankar is an associate editor at Ascend.

- KA Kelsey Alpaio is an Associate Editor at Harvard Business Review. kelseyalpaio

Partner Center

Scott H Young

Learn faster, achieve more

- Get Better at Anything

Now available!

The science of achievement: 7 research-backed tips to set better goals.

Setting goals can transform your life. Goals can help you get in shape, improve your finances, learn a new language, or finally launch that business.

But goal-setting can also leave you miserable. Burnout, stress and disillusionment are high on the list of potential side effects.

The crucial difference between success and burnout often comes down to how your goals are designed. Done wisely, setting goals can be a positive experience—not just successful, but life-affirming. Here are seven research-based suggestions to help you design better ones.

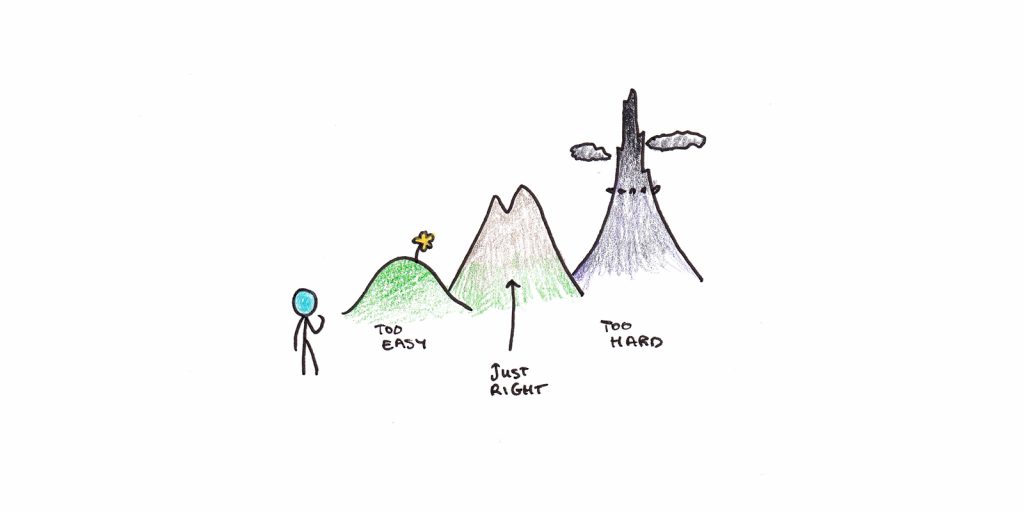

1. Aim for Hard, but Believable

For over four decades, psychologist Edwin Locke has been central in research on goal-setting. His research has three consistent findings :

- Setting goals improves performance.

- Hard goals improve performance more than easy ones.

- Specific targets work better than simply trying to “do your best.”

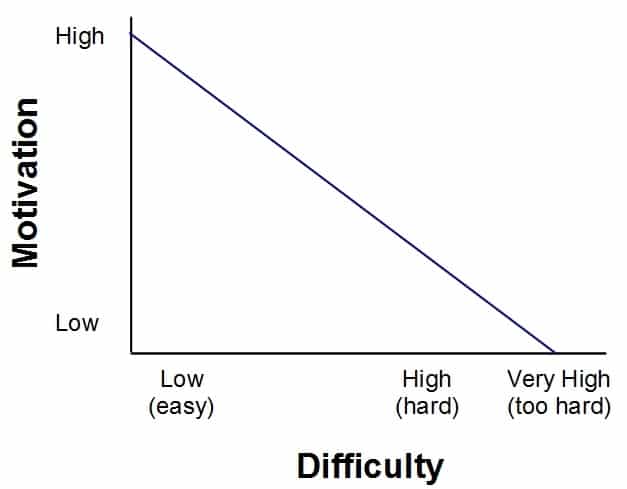

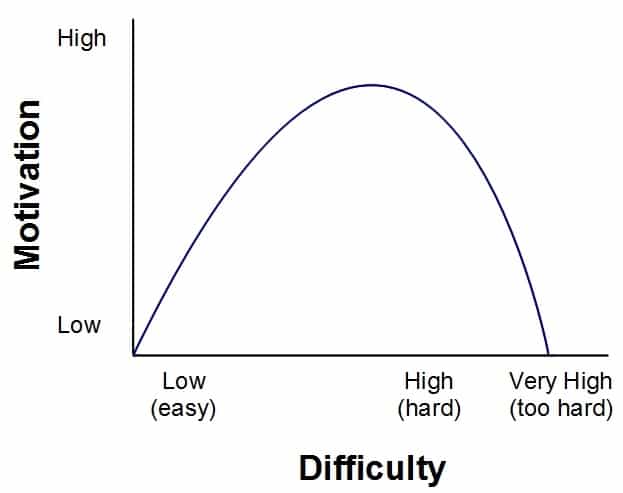

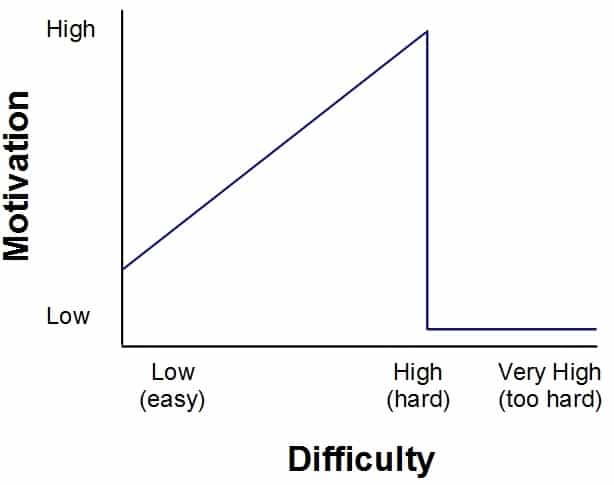

Early research on goal-setting found that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between difficulty and performance. 1 This means that easy goals lead to weak efforts, but so do goals that are too hard. The key factor here seems to be that goals need to be challenging, but also believable to be effective. If you don’t think you can actually reach a goal, you won’t.

Thus the best goals to set are those that demand effort from you, but you’re confident you can achieve if you put in the effort.

2. Use the 80% Rule

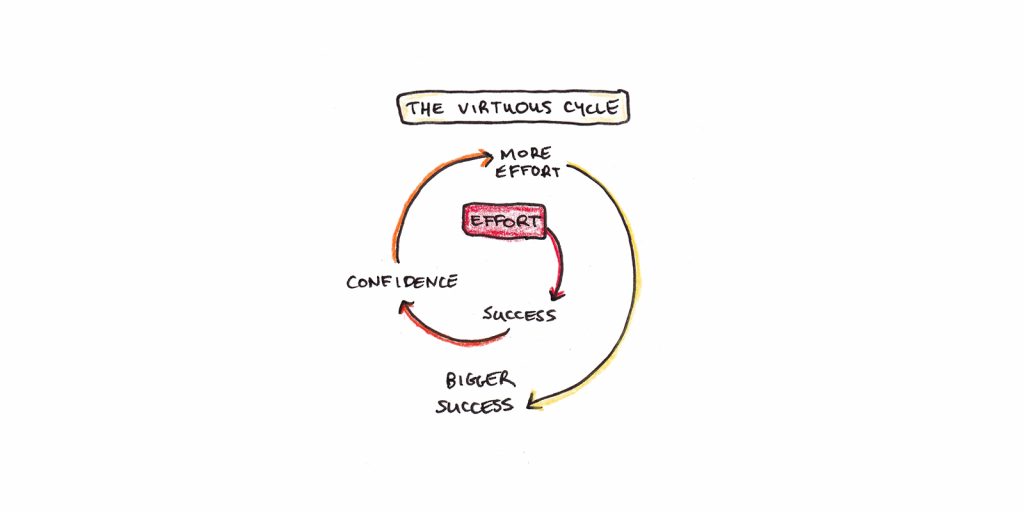

How do we build motivation to pursue our goals? Psychologist Albert Bandura developed the concept of self-efficacy to explain why some people eagerly face challenges while others shrink. If you don’t feel you’ll be successful, why bother?

The danger is that self-efficacy can create either a vicious or a virtuous cycle. If you don’t feel you’ll be successful, you don’t put effort into your goals. This leads to failure and seemingly confirms your inability. The reverse is also true: you can pick successful goals, achieve them and steadily boost your confidence.

One way to build confidence is the 80% rule. Psychologist Barak Rosenshine, in his review of successful teaching , found that this was approximately the success rate students should experience while in school. Too much success, and you’re likely not picking hard enough goals. Too little, and you can fall into the confidence trap.

One way to calibrate this is to set smaller goals (think 30 days) and track your success rate. If you’re under 80%, try setting a more achievable target. If you’re over 80%, try something a little more ambitious.

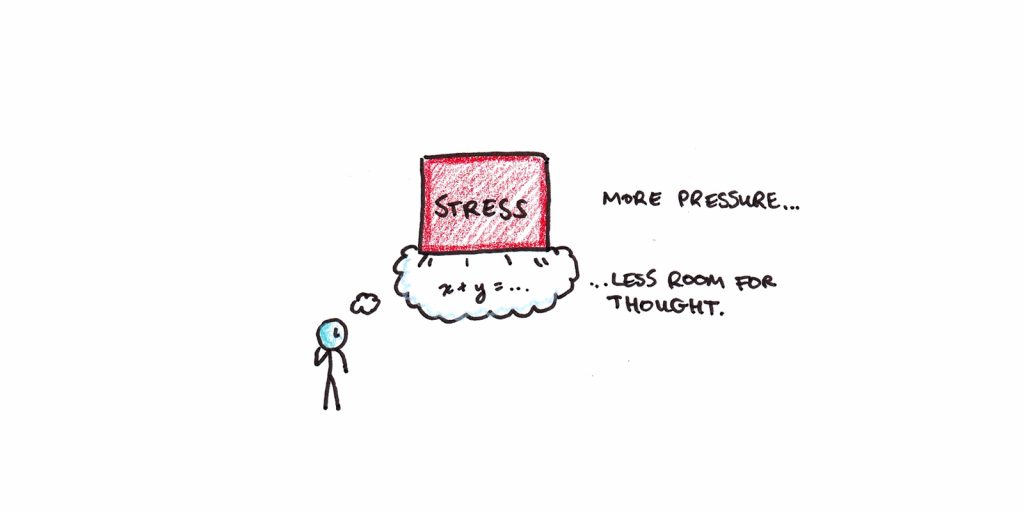

3. Deadlines Are Poison for Creative Problem-Solving

A significant exception to the power of specific, challenging goals involves creative problem-solving. In tasks that require complex thinking, such as learning, problem-solving or creative work, goal-setting can backfire .

Why is this? It’s because these activities require the full use of your working memory. Working memory is a psychological concept that corresponds roughly to mental bandwidth. It’s been known for several decades that the amount of things we can keep in mind at one time is limited—and often less than we think.

A stressful deadline to come up with a creative solution can hurt. The goal itself occupies so much space in your working memory that you have little left to try out new possible solutions. In these cases, you’re better off in a relaxed state with minimal distractions.

Of course, here we have a conflict. Goal-setting works by marshaling motivation and energy to reach a goal. Without goals, we often fail to put in the effort needed to achieve. However, if we are thinking about the goal while we’re working, we lose that mental bandwidth to develop creative solutions. How do we fix this?

One way is to set goals to work on a creative problem for a chunk of time without interruption or expectation of results. This allows you to focus on the task and gives your mind more space to think of solutions.

4. Visualize Failure

A common suggestion for goal-setting is to visualize success. But visualizing failure might work even better.

Psychologist Peter Gollwitzer suggests a key ingredient to the success of your goals is what he calls implementation intentions . These are when you visualize difficulties that might come up in pursuing your goal and decide in advance how you will handle them.

Many goals get derailed by events that are unexpected but not unimaginable. You get sick two weeks into an exercise program. Your exam gets rescheduled. You were ready to start your business, but the permits are delayed.

Imagining obstacles in advance and deciding your response can make those responses more effective when the time comes. Since your motivation is usually highest when setting the goal, this planning can keep you from abandoning your goal when things get difficult.

5. Keep it to Yourself (At Least to Start)

Should you tell other people about your goals? Surprisingly the answer is sometimes no.

In addition to implementation intentions, Peter Gollwitzer also studied the effects of telling people about the goals you want to achieve. Interestingly, his research found that telling people about your goals can substitute for actually taking action . Why is this?

Gollwitzer explains the results in terms of his theory of symbolic self-completion . According to this theory, we all want to maintain our image in the eyes of others. To do that, we display signals of our self-identity. Announcing our goals can make us feel like we have sent that signal, and our motivation to achieve the actual goal can go down.

This suggests we should focus first on taking action, not talking about it.

6. Break it Down and Make Yourself Accountable

Why do we procrastinate? The common perception is that procrastination is caused by perfectionism. People who need to do everything perfectly waste time getting started.

Except research doesn’t bear this out. In a comprehensive review, psychologist Piers Steel found perfectionism didn’t predict procrastination . What did? Unpleasant tasks and impulsive personalities.

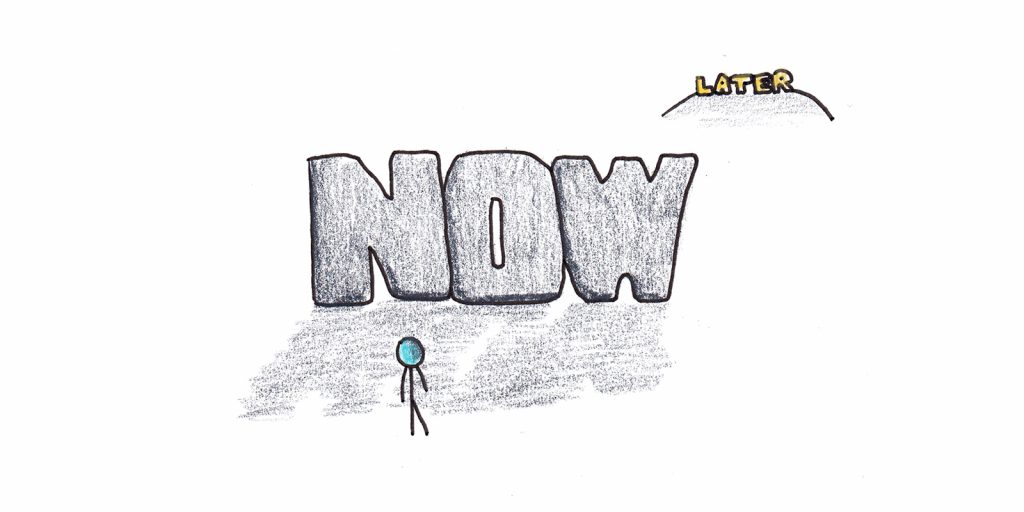

One difficulty with setting goals is that our motivational hardwiring doesn’t cope well with the future. When a deadline is far off, and the immediate work isn’t always fun, we’re likely to slack. This persists until shortly before the deadline when the fear of failure spurs us to action. Unfortunately, as we discussed in point 3, these last-minute efforts aren’t ideal for complex work.

The key is to break down your goals into smaller, daily actions. If you know what needs to be done today, you’re in a much better position to act on it.

It is even better is if you can create a compelling incentive to stick to the daily plan. A powerful tool for overcoming procrastination is precommitment. Telling a friend or spouse that you’ll give them money for each day you miss your plan is a surefire strategy to stay committed.

Less extreme solutions can also include following a “don’t break the chain” strategy. Once you’ve set your daily plan, keep a tally of how many days in a row you’ve followed it. The goal is not to miss a day. If you do, reset your tally and start over.

For goals that don’t break down into simple, daily habits, you can still focus on daily actions. Break the goal into smaller milestones that have short-term deadlines. The closer you can move your goals to the present, the more successfully they will guide your behavior.

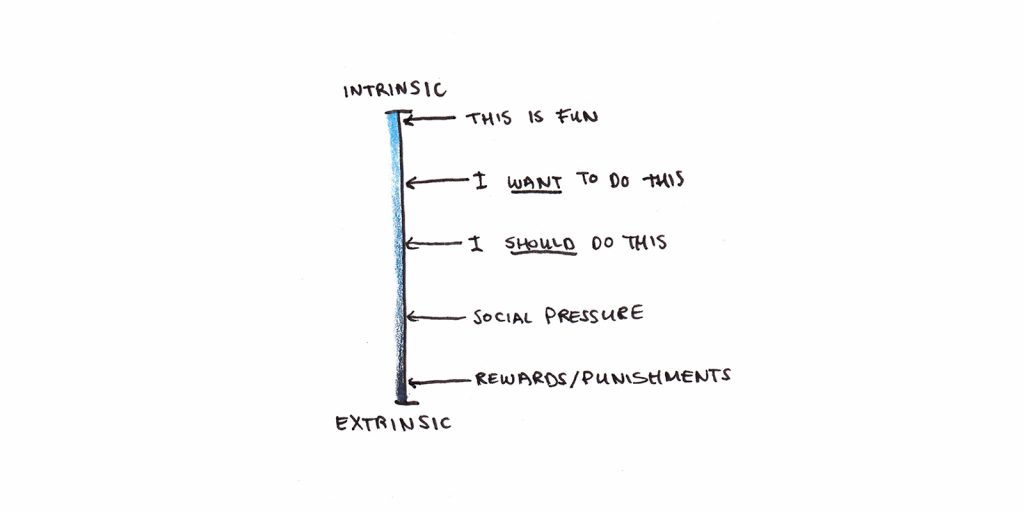

7. Set Goals You Want to Achieve (Not Just Those You Feel You Should)

Much of the stress and disillusionment people experience with goals comes from setting ones that aren’t truly their own. When we work on the goals of other people, goals we feel pressure to achieve but don’t actually want, the result is often misery.

Self-determination theory was developed by psychologists Edward Ryan and Richard Deci. They found that external incentives, such as paying someone to complete an otherwise interesting puzzle, could crowd out internal motivation. People would play the puzzle while being paid to, but they would play less when the rewards stopped.

They argue that many of the goals we pursue are only partially our own. We chase them because we feel we should, but they are somewhat “alien” to our deeper selves. Since these goals mainly just fulfill social expectations, they are harder to motivate ourselves toward consistently.

I suspect that the prevalence of these goals is why many have soured on goal-setting altogether. They have too many goals that aren’t truly their own. As a result, they are poorly motivated to achieve them, often fail to put in adequate effort, and experience stress and burnout.

For goal-setting to be life-affirming, the goals pursued have to feel deeply meaningful to you. Getting in touch with what you really want out of life, and separating out the things you merely think you “should” want, is perhaps the most essential part of goal-setting. A good life isn’t measured by the sum of your achievements, but by the meaning you attach to them. Choose wisely.

- Atkinson, John W. “Towards experimental analysis of human motivation in terms of motives, expectancies, and incentives.” Motives in fantasy, action and society (1958): 288-305.

Best Articles

- Best Learning

- Best Habits

- Best Goal Setting

- Best Life Philosophy

- Best Career

- Best Feeling Better

- Best Thinking Better

- Best Productivity

Related Articles

- Managing Stress with Daily Goals I recently wrote a guest post over at lifehack.org about managing stress by setting daily goals instead of traditional to-do lists. Daily goal-setting means chunking to-do items into a group...

- The Power of Goals One of my big focuses is on the power of goal setting. It is the subject of a software project I am working on designed to teach the subject. I...

- Achieving Impossible Goals Have you ever had an ambition or desire that you simply couldn’t see yourself achieving? A goal that, given your past behavior doesn’t seem likely to be obtained? Becoming fit...

- Goals an Interactive Guide I am pleased to announce that my interactive program designed to help teach goal setting is now available from the programs section of this website. It was a very interesting...

- Do You Even Want Success? (The Perils of Achievement Bias) Biases distort our perception of reality. Consider survivorship bias. This is the fact that when viewing a group, you often only have the ability to look at the success stories,...

About Scott

- Ultralearning

- Free Newsletter

MSU Extension

Achieving your goals: an evidence-based approach.

John Traugott, Michigan State University Extension - August 26, 2014

To achieve goals, write them down, make a plan and solicit support from a friend.

Setting and attaining goals is an important step in achieving success academically, in the working world and in life in general. Often people identify well defined goals and start out gung-ho and motivated toward achieving them, only to look back weeks later wondering where they got off track. New research suggests strategies to overcome this problem, providing empirical evidence that writing down your goals, committing to action steps and developing a support network dramatically increases success in attaining them. Michigan 4-H Youth Development offers strategies to help you achieve the goals you set.

A widely accepted goal setting practice is to decide what you want to obtain or achieve and then write down a “SMART” goal. SMART goals are S pecific in that they define the who, what, when and where of your goal. SMART goals should also be M easureable, so you can track your progress and they should be something that is personally within your ability to A ttain. Finally, they should be something that is R ealistic for you to achieve and set within a specific T imeframe.

The next phase, where many goal setters fall short, is to plan the steps you need to take and then put your plan into action. Questions to consider include:

- What activities do I need to complete to achieve my goal and in what timeframe?

- What resources do I need?

- Who can help me achieve my goal?

Additionally, you need to anticipate potential problems and brainstorm possible solutions. Find a supportive friend or network to help you stay on track with your goal and touch-base weekly with those friends to resolve issues and to assist in staying focused on success.

A recent study by Psychology Professor Dr. Gail Matthews confirms the importance of the steps above to achieve goals, providing empirical evidence that supports the practice of writing down goals and committing to action steps. Her research also highlights the effectiveness of goal setters soliciting a supportive friend to hold them accountable for completing their action steps through weekly progress updates. Matthews’s study broke participants into five groups, each with different instructions. The first group had unwritten goals, the second wrote their goals down, the third wrote down both goals and action commitments, the forth wrote goals and actions and gave them to a friend, and the fifth group gave their written goals and actions to a friend and also provided weekly updates.

The results of the study showed that 76 percent of participants who wrote down their goals, actions and provided weekly progress to a friend successfully achieved their goals. This result is 33 percent higher than those participants with unwritten goals, with a success rate of only 43 percent of goals achieved. This study shows the value of taking the time to write down your goals, create an action plan and develop a system of support to hold yourself accountable for achieving your goals.

Michigan State University Extension offers a variety of educational articles, programs and resources to learn more about setting career related, academic and personal goals.

This article was published by Michigan State University Extension . For more information, visit https://extension.msu.edu . To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit https://extension.msu.edu/newsletters . To contact an expert in your area, visit https://extension.msu.edu/experts , or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).

Did you find this article useful?

Ready to grow with 4-H? Sign up today!

new - method size: 3 - Random key: 1, method: tagSpecific - key: 1

You Might Also Be Interested In

AC3 Podcast episode 3

Published on June 30, 2021

What does this cover crop do for my farm?

Published on May 6, 2020

Innovative Online Tools for Conservation

Published on February 14, 2020

MSU Dairy Virtual Coffee Break: LEAN farming for dairies

Published on April 6, 2021

Should I Still be Applying the Full Rate of Fertilizer?

Published on October 12, 2021

Food Organization to Make Healthy Choices with Nola Auernhamer

Published on September 14, 2020

- 4-h careers & entrepreneurship

- careers & entrepreneurship

- life skills

- msu extension

- 4-h careers & entrepreneurship,

- careers & entrepreneurship,

- life skills,

The Importance, Benefits, and Value of Goal Setting

We all know that setting goals is important, but we often don’t realize how important they are as we continue to move through life.

Goal setting does not have to be boring. There are many benefits and advantages to having a set of goals to work towards.

Setting goals helps trigger new behaviors, helps guides your focus and helps you sustain that momentum in life.

Goals also help align your focus and promote a sense of self-mastery. In the end, you can’t manage what you don’t measure and you can’t improve upon something that you don’t properly manage. Setting goals can help you do all of that and more.

In this article, we will review the importance and value of goal setting as well as the many benefits.

We will also look at how goal setting can lead to greater success and performance. Setting goals not only motivates us, but can also improve our mental health and our level of personal and professional success.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

The importance and value of goal setting, why set goals in life, what are the benefits of goal setting, 5 proven ways goal setting is effective, how can goal setting improve performance, how goal setting motivates individuals, why is goal setting important for students, a look at the importance of goal setting in mental health, the importance of goal setting in business and organizations, 10 quotes on the value and importance of setting goals, a take-home message.

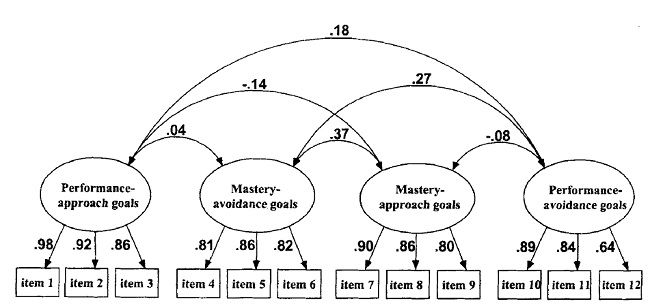

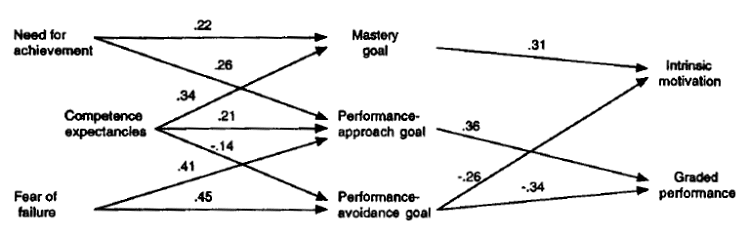

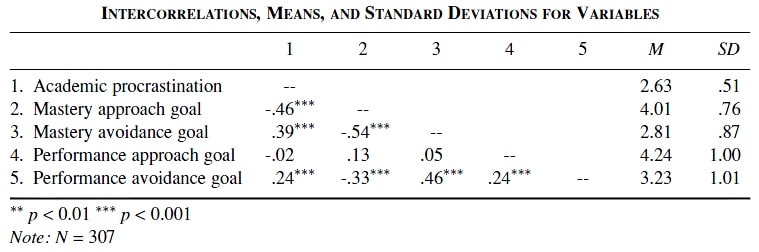

Up until 2001, goals were divided into three types or groups (Elliot & McGregor, 2001):

- Mastery goals

- Performance-approach goals

- Performance-avoidance goals

A mastery goal is a goal someone sets to accomplish or master something such as “ I will score higher in this event next time .”

A performance-approach goal is a goal where someone tries to do better than his or her peers. This type of goal could be a goal to look better by losing 5 pounds or getting a better performance review.

A performance-avoidance goal is a goal where someone tries to avoid doing worse than their peers such as a goal to avoid negative feedback.

Research done by Elliot and McGregor in 2001 changed these assumptions. Until this study was published, it was assumed that mastery goals were the best and performance-approach goals were at times good, and other times bad. Performance-avoidance goals were deemed the worst, and, in fact, bad.

The implied assumption, as a result of this, was that there were no bad mastery goals or mastery-avoidance goals.

Elliot and McGregor’s study challenged those assumptions by proving that master-avoidance goals do exist and proving that each type of goal can, in fact, be useful depending on the circumstances.

Elliot and McGregor’s research utilized a 2 x 2 achievement goal framework comprised of:

- Mastery-approach

- Mastery-avoidance

- Performance-approach

- Performance-avoidance

These variables were tested in 3 studies. In experiments one and two, explanatory factor analysis was used to break down 12 goal-setting questions into 4 factors, as seen in the diagram below.

Confirmatory factor analysis was used at a later date to show that mastery-avoidance and mastery-approach fit the data better than mastery alone.

The questions for these studies were created from a series of pilot studies and prior questionnaires. Once all of the questions were combined, a factor-analysis was utilized to confirm that each set of questions expressed different goal-setting components.

Results of these studies showed that those with a high motive to achieve were much more likely to use approach goals. Those with a high motive to avoid failure, on the other hand, were much more likely to use avoidance goals.

The third experiment examined the same four achievement goal variables and revealed that those more likely to use performance-approach goals were more likely to have higher exam scores, while those who used performance-avoidance goals were more likely to have lower exam scores.

According to the research, motivation in achievement settings is complex, and achievement goals are but one of several types of operative variables to be considered.

Achievement goal regulation, or the actual pursuit of the goal, implicates both the achievement goal itself as well as some other typically higher order factors such as motivationally relevant variables, according to the research done by Elliot and McGregor.

As we can clearly see, the research on goal setting is quite robust.

Mark Murphy the founder and CEO of LeadershipIQ.com and author of the book “ Hard Goals : The Secret to Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be ,” has gone through years of research in science and how the brain works and how we are wired as a human being as it pertains to goal setting.

Murphy’s book “ Hard Goals: The Secret to Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be” combines the latest research in psychology and brain science on goal-setting as well as the law of attraction to help fine-tune the process.

A HARD goal is an achieved goal, according to Murphy (2010). Murphy tells us to put our present cost into the future and our future benefit into the present.

What this really means is don’t put off until tomorrow what you could do today. We tend to value things in the present moment much more than we value things in the future.

Setting goals is a process that changes over time. The goals you set in your twenties will most likely be very different from the goals you set in your forties.

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Edward Locke and Gary Latham (1990) are leaders in goal-setting theory. According to their research, goals not only affect behavior as well as job performance, but they also help mobilize energy which leads to a higher effort overall. Higher effort leads to an increase in persistent effort.

Goals help motivate us to develop strategies that will enable us to perform at the required goal level.

Accomplishing the goal can either lead to satisfaction and further motivation or frustration and lower motivation if the goal is not accomplished.

Goal setting can be a very powerful technique, under the right conditions according to the research (Locke & Latham, 1991).

According to Lunenburg (2011), the motivational impact of goals may, in fact, be affected by moderators such as self-efficacy and ability as well.

In the 1968 article “ Toward a Theory of Task Motivation ” Locke showed us that clear goals and appropriate feedback served as a good motivator for employees (Locke, 1968).

Locke’s research also revealed that working toward a goal is a major source of motivation, which, in turn, improves performance.

Locke reviewed over a decade of research of laboratory and field studies on the effects of goal setting and performance. Locke found that over 90% of the time, goals that were specific and challenging, but not overly challenging, led to higher performance when compared to easy goals or goals that were too generic such as a goal to do your best.

Dr. Gary Latham also studied the effects of goal setting in the workplace. Latham’s results supported Locke’s findings and showed there is indeed a link that is inseparable between goal setting and workplace performance.

Locke and Latham published work together in 1990 with their work “ A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance ” stressing the importance of setting goals that were both specific and difficult.

Locke and Latham also stated that there are five goal-setting principles that can help improve your chances of success.

- Task Complexity

Clarity is important when it comes to goals. Setting goals that are clear and specific eliminate the confusion that occurs when a goal is set in a more generic manner.

Challenging goals stretch your mind and cause you to think bigger. This helps you accomplish more. Each success you achieve helps you build a winning mindset.

Commitment is also important. If you don’t commit to your goal with everything you have it is less likely you will achieve it.

Feedback helps you know what you are doing right and how you are doing. This allows you to adjust your expectations and your plan of action going forward.

Task Complexity is the final factor. It’s important to set goals that are aligned with the goal’s complexity.

Why the secret to success is setting the right goals – John Doerr

Goal setting and task performance were studied by Locke and Latham (1991). Goal setting theory is based upon the simplest of introspective observations, specifically, that conscious human behavior is purposeful.

This behavior is regulated by one’s goals. The directedness of those goals characterizes the actions of all living organisms including things like plants.

Goal-setting theory, according to the research, states that the simplest and most direct motivational explanation on why some people perform better than others is because they have different performance goals.

Two attributes have been studied in relation to performance:

In regard to content, the two aspects that have been focused on include specificity and difficulty. Goal content can range from vague to very specific as well as difficult or not as difficult.

Difficulty depends upon the relationship someone has to the task. The same task or goal can be easy for one person, and more challenging for the next, so it’s all relative.

On average though the higher the absolute level is of a goal, the more difficult it is to achieve. According to research, there have been more than 400 studies that have examined the relationship of goal attributes to task performance.

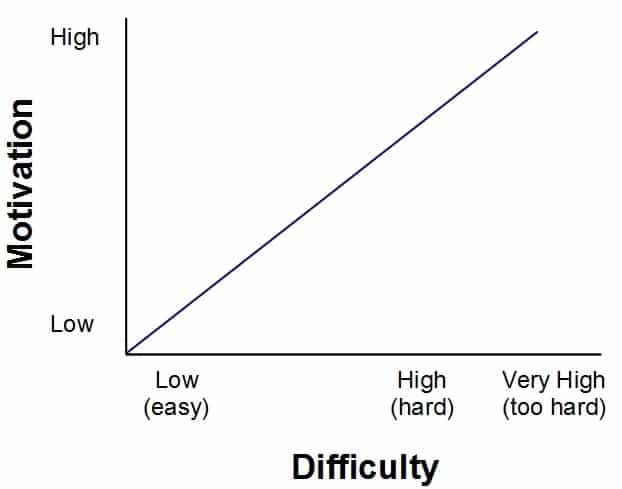

According to Locke and Latham (1991), it has been consistently found that performance is a linear function of a goal’s difficulty.

Given an adequate level of ability and commitment, the harder a goal, the higher the performance.

What the researchers discovered was that people normally adjust their level of effort to the difficulty of the goal. As a result, they try harder for difficult goals when compared to easier goals.

The principle of goal-directed action is not restricted to conscious action, according to the research.

Goal-directed action is defined by three attributes, according to Lock & Latham.

- Self-generation

- Value-significance

- Goal-causation

Self-generation refers to the source of energy integral to the organism. Value-significance refers to the idea that the actions not only make it possible but necessary to the organism’s survival. Goal-causation means the resulting action is caused by a goal.

While we can see that all living organisms experience some kind of goal-related action, humans are the only organisms that possess a higher form of consciousness, at least according to what we know at this point in time.

When humans take purposeful action, they set goals in order to achieve them.

Locke and Latham have also shown us that there is an important relationship between goals and performance.

Locke and Latham’s research supports the idea that the most effective performance seems to be the result of goals being both specific and challenging. When goals are used to evaluate performance and linked to feedback on results, they create a sense of commitment and acceptance.

The researchers also found that the motivational impact of goals may be affected by ability and self-efficacy, or one’s belief that they can achieve something.

It was also found that deadlines helped improve the effectiveness of a goal and a learning goal orientation leads to higher performance when compared to a performance goal orientation.

Research done by Moeller, Theiler, and Wu (2012) examined the relationship between goal setting and student achievement at the classroom level.

This research examined a 5-year quasi-experimental study, which looked at goal setting and student achievement in the high school Spanish language classroom.

A tool known as LinguaFolio was used, and introduced into 23 high schools with a total of 1,273 students.

The study portfolio focused on student goal setting , self-assessment and a collection of evidence of language achievement.

Researchers used a hierarchical linear model, and then analyzed the relationship between goal setting and student achievement. This research was done at both the individual student and teacher levels.

A correlational analysis of the goal-setting process as well as language proficiency scores revealed a statistically significant relationship between the process of setting goals and language achievement (p < .01).

The research also looked at the importance of autonomy or one’s ability to take responsibility for their learning. Autonomy is a long-term aim of education, according to the study as well as a key factor in learning a language successfully.

There has been a paradigm shift in language education from teacher to student-centered learning, which makes the idea of autonomy even more important.

Goal setting in language learning is commonly regarded as one of the strategies that encourage a student’s sense of autonomy (Moeller, Theiler & Wu, 2012)

The results of the study revealed that there was a consistent increase over time in the main goal, plan of action and reflection scores of high school Spanish learners.

This trend held true for all levels except for the progression from third to fourth year Spanish for action plan writing and goal setting. The greatest improvement in goal setting occurred between the second and third levels of Spanish.

In one study , that looked at goal setting and wellbeing, people participated in three short one-hour sessions where they set goals.

The researchers compared those who set goals to a control group, that didn’t complete the goal-setting exercise . The results showed a causal relationship between goal setting and subjective wellbeing.

Weinberger, Mateo, and Sirey (2009) also looked at perceived barriers to mental health care and goal setting amongst depressed, community-dwelling older adults.

Forty-seven participants completed the study, which examined various barriers to mental health and goal setting. These barriers include:

- Psychological barriers such as social attitudes, beliefs about depression and stigmas.

- Logistical barriers such as transportation and availability of services.

- Illness-related barriers that are either modifiable or not such as depression severity, comorbid anxiety, cognitive status, etc.

For individuals who perceive a large number of barriers to be overcome, a mental health referral can seem burdensome as opposed to helpful.

Defining a personal goal for treatment may be something that is helpful and even something that can increase the relevance of seeking help and improving access to care according to the study.

Goal setting has been shown to help improve the outcome in treatment, amongst studies done in adults with depression. (Weinberger, Mateo, & Sirey, 2009)

The process of goal setting has even become a major focus in several of the current psychotherapies used to treat depression. Some of the therapies that have used goal setting include:

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT)

- Cognitive and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CT, CBT)

- Problem-Solving Therapy (PST)

Participants who set goals, according to the study, were more likely to accept a mental health referral. Goal setting seems to be a necessary and good first step when it comes to helping a depressed older adult take control of their wellbeing.

Most of us have been taught from a young age that setting goals can help us accomplish more and get better organized.

Goals help motivate us and help us organize our thoughts. Throughout evolutionary psychology, however, a conscious activity like goal setting has often been downplayed.

Psychoanalysis put the focus on the unconscious part of the mind, while cognitive behaviorists argue that external factors are of greater importance.

In 1968, Edward A. Locke formally developed something he called goal-setting theory, as an alternative to all of this.

Goal-setting theory helps us understand that setting goals are a conscious process and a very effective and efficient means when it comes to increasing productivity and motivation, especially in the workplace.

According to Gary P. Latham, the former President of the Canadian Psychological Association, the underlying premise of goal-setting theory is that our conscious goals affect what we achieve. Our goals are the object or the aim of our action.

This viewpoint is not aligned with the traditional cognitive behaviorism, which looks at human behavior as something that is conducted by external stimuli.

This view tells us that just like a mechanic works on a car, other people often work on our brains, without us even realizing it, and this, in turn, determines how we behave.

Goal setting theory goes beyond this assumption, telling us that our internal cognitive functions are equally important, if not more, when determining our behavior.

In order for our conscious cognition to be effective, we must direct and orient our behavior toward the world. That is the real purpose of a goal.

According to Locke and Latham, there is an important relationship between goals and performance.

Research supports the prediction that the most effective performance often results when goals are both specific and challenging in nature.

A learning goal orientation often leads to higher performance when compared to a performance goal orientation, according to the research.

Deadlines also improve the effectiveness of a goal. Goals have a pervasive influence on both employee behaviors and performance in organizations and management practice according to Locke and Latham (2002).

According to the research, nearly every modern organization has some type of psychological goal setting program in its operation.

Programs like management by objectives, (MBO), high-performance work practices (HPWP) and management information systems (MIS) all use benchmarking to stretch targets and plan strategically, all of which involve goal setting to some extent.

Fred C. Lunenburg, a professor at Sam Houston State University, summarized these points in the International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration journal article “Goal-Setting Theory of Motivation” (Lunenburg, 2011).

Specific: Specificity tells us that in order for a goal to be successful, it must also be specific. Goals such as I will do better next time are much too vague and general to motivate us.

Something more specific would be to state: I will spend at least 2 hours a day this week in order to finish the report by the deadline . This goal motivates us into action and holds us accountable.

Difficult but still attainable : Goals must, of course, be attainable, but they shouldn’t be too easy. Goals that are too simple may even cause us to give up. Goals should be challenging enough to motivate us without causing us undue stress.

Process of Acceptance : If we are continually given goals by other people, and we don’t truly accept them, we will most likely continue to fail. Accepting a goal and owning a goal is the key to success.

One way to do this on an organizational level is to bring team members together to discuss and set goals.

Feedback and evaluation : When a goal is accomplished, it makes us feel good. It gives us a sense of satisfaction. If we don’t get any feedback, this sense of pleasure will quickly go away and the accomplishment may even be meaningless.

In the workplace, continuous feedback helps give us a sense that our work and contributions matter. This goes beyond measuring a single goal.

When goals are used for performance evaluation, they are often much more effective.

Learning beyond our performance : While goals can be used as a means by which to give us feedback and evaluate our performance, the real beauty of goal setting is the fact that it helps us learn something new.

When we learn something new, we develop new skills and this helps us move up in the workplace.

Learning-oriented goals can also be very helpful when it comes to helping us discover life-meaning which can help increase productivity.

Performance-oriented goals, on the other hand, force an employee to prove what he or she can or cannot do, which is often counterproductive.

These types of goals are also less likely to produce a sense of meaning and pleasure. If we lack that sense of satisfaction, when it comes to setting and achieving a goal, we are less likely to learn and grow and explore.

Group goals : Setting group goals is also vitally important for companies. Just as individuals have goals, so too must groups and teams, and even committees. Group goals help bring people together and allow them to develop and work on the same goals.

This helps create a sense of community, as well as a deeper sense of meaning, and a greater feeling of belonging and satisfaction.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

A goal properly set is halfway reached.

Everybody has their own Mount Everest they were put on this earth to climb.

You cannot change your destination overnight, but you can change your direction overnight.

It’s better to be at the bottom of the ladder you want to climb than at the top of the one you don’t.

Stephen Kellogg

If you don’t design your own life plan, chances are you’ll fall into someone else’s plan. And guess what they have planned for you? Not much.

All who have accomplished great things have had a great aim, have fixed their gaze on a goal which was high, one which sometimes seemed impossible.

Orison Swett Marden

The greater danger for most of us isn’t that our aim is too high and miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.

Michelangelo

Give me a stock clerk with a goal and I’ll give you a man who will make history. Give me a man with no goals and I’ll give you a stock clerk.

J.C. Penney

Intention without action is an insult to those who expect the best from you.

Andy Andrews

This one step – choosing a goal and sticking to it – changes everything.

Setting goals can help us move forward in life. Goals give us a roadmap to follow. Goals are a great way to hold ourselves accountable, even if we fail. Setting goals and working to achieving them helps us define what we truly want in life.

Setting goals also helps us prioritize things. If we choose to simply wander through life, without a goal or a plan, that’s certainly our choice. However, setting goals can help us live the life we truly want to live.

Having said that, we don’t have to live every single moment of our lives planned out because we all need those days when we have nothing to accomplish.

However, those who have clearly defined goals might just enjoy their downtime even more than those who don’t set goals.

For more insightful reading, check out our selection of goal-setting books .

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 x 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80 (3), 501-519.

- Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance , 3 (2), 157-189.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1991). A theory of goal setting & task performance. The Academy of Management Review, 16 (2), 212-247.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57 (9), 705-717.

- Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Goal-setting theory of motivation. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 15 (1), 1-6.

- Moeller, A. J., Theiler, J. M., & Wu, C. (2012). Goal setting and student achievement: A longitudinal study. The Modern Language Journal, 96 (2), 153-169.

- Murphy, M. (2010). HARD goals: The secret to getting from where you are to where you want to be. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Weinberger, M. I., Mateo, C., & Sirey, J. A. (2009). Perceived barriers to mental health care and goal setting among depressed, community-dwelling older adults. Patient Preference and Adherence, 3 , 145-149.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

I really love how the lesson teaches us how to set goals more often

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation

Motivation is vital to beginning and maintaining healthy behavior in the workplace, education, and beyond, and it drives us toward our desired outcomes (Zajda, 2023). [...]

SMART Goals, HARD Goals, PACT, or OKRs: What Works?

Goal setting is vital in business, education, and performance environments such as sports, yet it is also a key component of many coaching and counseling [...]

How to Assess and Improve Readiness for Change

Clients seeking professional help from a counselor or therapist are often aware they need to change yet may not be ready to begin their journey. [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (29)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (37)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (63)

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Goal Achievement Exercises Pack

Goal-Setting Theory

Locke, et al (1981) defined the “goal” in Goal-Setting Theory (GST) as “what an individual is trying to accomplish; it is the object or aim of an action” (p. 126). According to Moeller et al. (2012), goal setting is the process of establishing specific and effective targets for task performance. Locke, et al. (1981) also provided evidence that goal setting has a positive influence on task performance. Latham and Locke (2007) explained that “a specific high goal leads to even higher performance than urging people to do their best” (p. 291).

Before the 1960s, some researchers began to study the effectiveness of setting goals in business. The results showed that goal setting has a positive influence on workers’ performance. However, there was a lack of theoretical framework to explain why and how goal-setting influences work performance (Latham & Locke, 2007). GST served to explain human behavior in specific work situations (Locke, 1968). After a lot of experimental research done by Locke and Latham, GST was formalized in 1990 (Locke & Latham, 1990; Locke & Latham, 2002). The theory is now seen as “one of the most influential frameworks in motivational psychology” (Nebel et al., 2017, p. 102).

Previous Studies

Studies that employ GST can be divided generally into three domains. First, in academics, setting goals was shown to have a significant influence on students’ learning performance (see, e.g., Gardner et al, 2016; Locke & Latham, 1990 ; Locke & Latham, 2002 ). For example, Gardner et al. (2016) invited 127 medical students to participate in surgical skill training. They found that goal setting was effective in helping new students acquire surgical skills, especially when students develop specific strategy and goal orientations. In other words, the study found that students have better learning performance when they have clearer and more specific goals. In addition, Neble et al. (2017) had 87 students play the video game Minecraft (Mojang, 2011), and the results showed that for those students who set specific goals, their cognitive load was lowered. Further, Moeller and colleagues (2012) conducted a five-year quasi-experimental study on the relationship between goal setting and the performance of Spanish language learners in high school. The results indicated that having high-quality goals contributed to students’ better language acquisition.

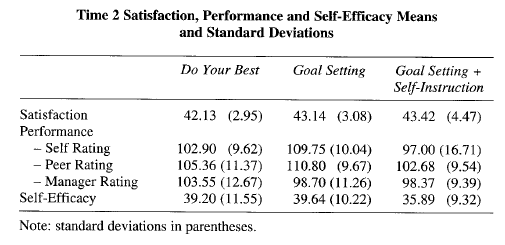

Second, Latham and Locke (2007) pointed out in their study that, in the field of organization and human resource management, goal setting can have an impact on employees’ behavior and performance in the workplace. Based on this idea, 108 middle level banking managers in Indonesia were invited by Aunurrafiq et al. (2015) to investigate whether setting goals could have a positive impact on their managerial performance. They provided evidence that goal specificity, goal participation, and goal commitment are significant factors in enhancing managers’ managerial performance. In addition, Brown and Latham (2000) invited 36 unionized employees in a Canadian telecommunications company to test the effectiveness of three ways to increase employees’ performance. Their results indicated that the employees with specific and challenging goals reached higher performance levels than those who set goals along with self-instructions to do their best.

Third, goal setting has also been popularized in the field of sports. According to Weinburg and Butt (2014), “Setting goals can help athletes prioritize what is the most important to them in their sport and subsequently guide daily practices by knowing what to work on” (p. 343). Locke and Latham (1985) concur. In Locke and Latham’s (1985) study, they found that setting goals can be more effective in sports because the performance of sports is easier to measure. In another study, Burton et al. (2010) investigated the impact of incorporating goal setting and goal strategies between highly effective and less effective athletes among 570 college athletes who participated in 18 sports at a university. The results indicated that goal setting had a positive impact on their performance, and the athletes who set goals and implemented goal strategies more frequently tended to be both more effective than others and have better sports performance. Finally, a study conducted by Bueno et al. (2008) on the effectiveness of goal setting on endurance athletes’ performance indicated that goal setting is effective in increasing efficacy, which leads to better performance in endurance sports.

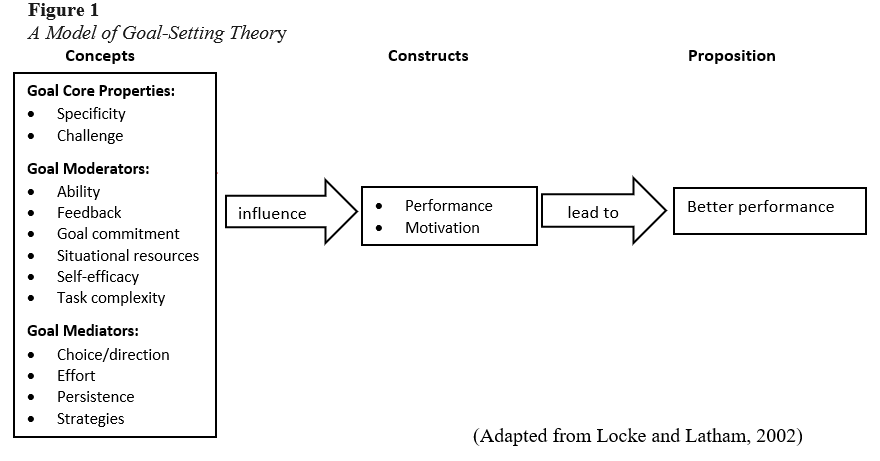

Model of Goal-Setting Theory

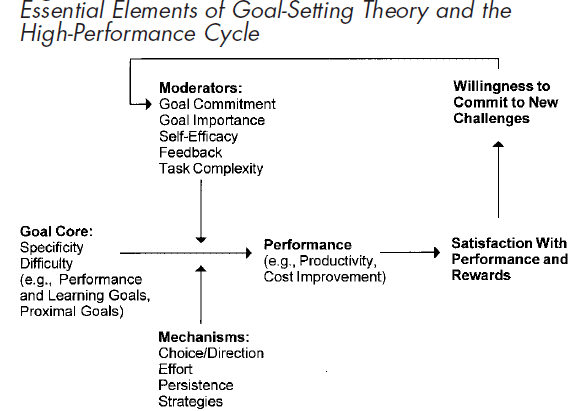

This model in Figure 1 is adapted from Locke and Latham (2002) and consists of three parts: concepts, constructs, and a proposition. The concepts include key factors that affect peoples’ performance, with moderators and mediators that might affect the goals that are set. The constructs indicate that these concepts impact people’s performance and motivation. The proposition shows that a specific and challenging goal, combined with regular feedback, can increase motivation and productivity so that people can perform better. These model aspects are described below.

Locke (1990) pointed out that there are some significant factors that can impact an individual’s performance: core goal properties (e.g., specificity, challenge), moderators (e.g. ability, feedback, goal commitment), and mediators (e.g., choice, effort). Latham (2003) pointed out in one study that individuals who have specific, challenging, but attainable goals have better performance than those who set vague goals or do not set goals. Meanwhile, individuals should possess ability and have commitment to the goal to have better performance.

For the part of moderators, Locke (1990) explains ability as whether people possess skill or knowledge to finish the task. Feedback is also needed for people to decide whether they should put forth more effort or change their strategy. Moreover, goal commitment refers to whether individuals have the determination to realize the goal. In addition to ability, feedback, and commitment, task complexity is also considered important; it indicates that people tend to have better performance when the tasks are more straightforward. In addition, situational resources, the related resources or materials provided for individuals to achieve their goal, are also essential. Finally, self-efficacy refers to whether people are confident in doing something and that it will affect their goals and performance (Locke & Latham, 1990).

For the part of mediators, choice means that people will make an effort towards the goal-relevant activities when they choose to set specific and difficult goals. Furthermore, persistence refers to how long people will stick to the goal and if individuals are willing to spend time on achieving it. If so, they may have better performance (Locke & Latham, 1990). Finally, a specific, high goal needs a strategy to attain it.

According to the discussion above, with these important factors (e.g. specificity, challenge, ability, feedback, effort) in the concepts, people tend to have better performance and are more willing to face new challenges. Performance consists of a variety of behaviors, from test-taking to running a competitive race.

Proposition

To conclude, the proposition of GST is that when the concepts are optimal for an individual, better performance can result. What is optimal for each individual is a subject for research.

Using the Model

Goal-setting theory could be used in different domains such as teaching or research. In teaching, for example, this theory could be used as an instructional procedure to improve students’ writing performance for those who have difficulty in learning writing. By setting specific goals of what will be written in each paragraph, students may perform better in their writing class (Page & Graham, 1999). In addition, Nebel, et al. (2017) mentions that GST can also be used while using educational video games such as Minecraft ; goal setting can reduce students’ cognitive load when they set specific goals. Moreover, players who use educational video games and follow a specific learning goal can be impacted affectively by goal setting. In other words, students tend to become more engaged and show greater passion in finishing the task when they have clear goals. Moreover, Idowu, et al. (2014) invited 80 senior secondary school students to investigate whether goal setting skills are effective for students’ academic performance in English, and the results indicated that the incorporation of a goal setting strategy can enhance students’ academic performance in English. In other words, teachers can encourage students to create goals that can support their academic performance.

In the research area, studies investigate the influence of GST on language learners’ motivation and self-efficacy, which can better help language learners and language experts understand how to set up different goals affecting students’ self-efficacy and motivation in language learning (Azar et al., 2013). For future study, researchers could integrate goal-setting and self-efficacy theories to explore outcomes and the reasons for them, or studies could use GST with young children to see whether the theory applies across ages.

To conclude, goal setting can play a significant role in enhancing people’s motivation and performance. People who set specific, challenging goals and commit to these goals are more likely to try their best and persist in achieving the goals, which can lead to better performance and success.

Aunurrafiq., Sari, R. N., & Basri, Y. M. (2015). The moderating effect of goal setting on performance measurement system-managerial performance relationship. Procedia Economics and Finance, 31 , 876-884.

Azar, H. F., Reza, P., & Fatemeh, V. (2014). The role of goal-setting theory on Iranian EFL learners’ motivation and self-efficacy. International Journal of Research Studies Language Learning, 3 (2), 69-84.

Brown, T., & Latham, G. P. (2000). The effects of goal setting and self-instruction training on the performance of unionized employees . Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 55 (1), 80-95.

Bueno, J., Weinberg, R.S., Fernandez, C., & Capdevila, L. (2008). Emotional and motivational mechanisms mediating the influence of goal setting on endurance athletes’ performance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9 (6), 786-799.

Burton, D., Yukelson, D., Weinberg, R., & Weigand, D. (1998). The goal effectiveness paradox in sport: Examining the goal practices of collegiate athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 12 (4), 404-418.

Chen, X., & Latham, G. P. (2014). The effect of priming learning vs. performance goals on a complex task. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 125 (2), 88-97.

Gardner, K.A., Diesen, D.L., Hogg, D., & Huerta, S. (2016). The impact of goal setting and goal orientation on performance during a clerkship surgical skills training program. The American Journal of Surgery, 211 (2), 321-325.

Idowu, A., Chibuzoh, I., & Louisa, M. (2014). Effects of goal-setting skills on students’ academic performance in English language in Enugu Nigeria. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research (NAER Journal), 3 (2), 93-99.

Latham, G. P. (2003). Goal setting: A five-step approach to behavior change. Organizational Dynamics, 32 (3), 309-318.

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2007). New developments in and directions for goal-setting research. European Psychologist, 12 (4), 290-300.

Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance,3 (2), 157-189.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1979). Goal setting: A motivational technique that works. Organizational Dynamics, 8 (2), 68-80.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1985). The application of goal setting to sports . Journal of Sport Psychology, 7 (1985), 205-222.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57 (9), 705-717.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory . Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15 (5), 265-268.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5 (2), 93-105.

Locke, E. A., Shaw, K. N., Saari, L. M., & Latham, G. P. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90 (1), 125-152.

MINECRAFT. (2011). [Developed by Mojang]. Mojang.

Moeller, A. J., Theiler, J. M., & Wu, C. (2012). Goal setting and student achievement: A longitudinal study. The Modern Language Journal, 96 (2), 153-169.

Nebel, S., Schneider, S., Schledjewski, J., & Rey, G. D. (2017). Goal- setting in educational video games: Comparing goal-setting theory and the goal-free effect. Simulation & Gaming, 48 (1), 98–130.

O’Neil H. F., & Drillings, M. (Eds.). (1994). Motivation: Theory and research . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ordóñez, L. D., Schweitzer, M. E., Galinsky, A. D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2009). Goals gone wild: The systematic side effects of overprescribing goal setting. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23 (1), 6-16.

Page, V., & Graham, S. (1999). Effects of goal setting and strategy use on the writing performance and self-efficacy of students with writing and learning problems. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91 (2), 230-240.

Weinberg, R., & Butt, J. (2014). Goal-setting and sport performance. In Athanasios G., Papaioannou, & Hackfort, D. (Eds.), Sport and Exercise Psychology (pp.343-355). Routledge.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Goal Setting Research

There might be affiliate links on this page, which means we get a small commission of anything you buy. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Please do your own research before making any online purchase.

There is impressive science behind the theory of goal setting. This post is a sampling of the research on goal setting, in chronological order.

This goal setting research list contains most of the high points on our understanding of the importance of goal setting found by scientists, psychologists and other researchers over the past 40+ years. Enjoy.

To learn more about achieving great things and the importance of goals check out goal setting theory .

Table of Contents

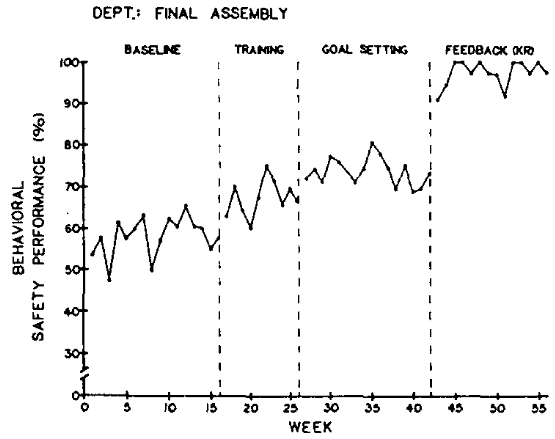

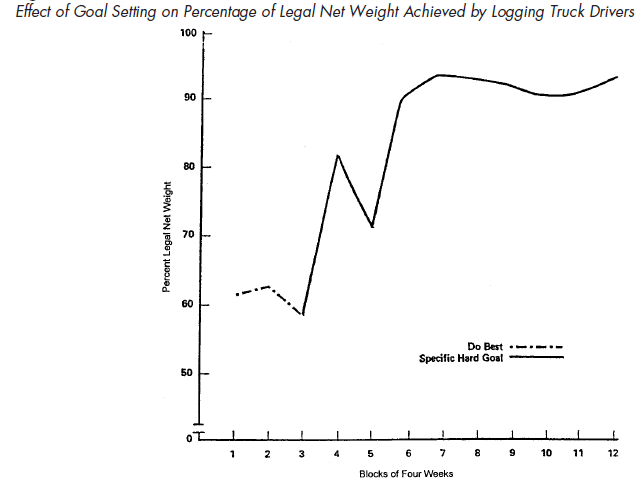

Improving Job Performance Through Training in Goal Setting

20 tree logging operators were randomly assigned to either a 1-day training program in goal setting or a control group. The additional wood cut over the following 3 months by those in the goal-setting group was estimated to be worth a quarter of a million dollars. Absenteeism fell and production increased.

A Review of Research on The Application of Goal Setting in Organizations

“Twenty-seven studies on goal setting were reviewed to evaluate the practical feasibility of goal setting in organizations and to evaluate Locke's theories of goal setting . The organizational research reviewed provides strong support for Locke's proposition that specific goals increase performance and those difficult goals, if accepted, result in better performance than do easy goals.”

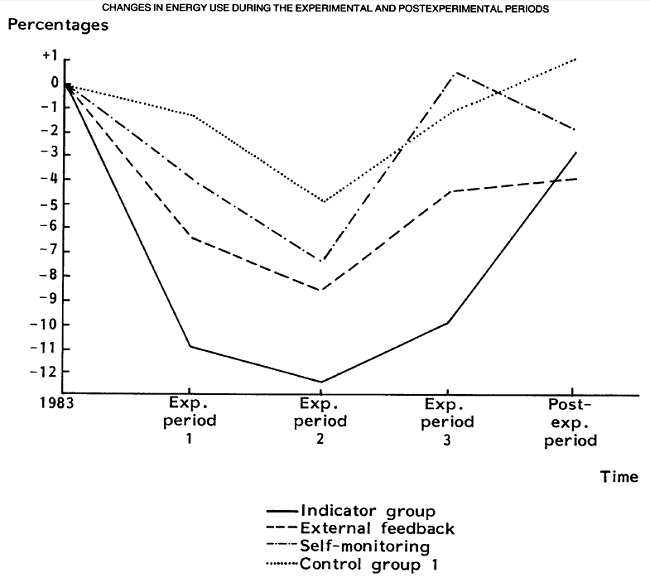

Joint Effect of Feedback and Goal Setting on Performance: A Field Study of Residential Energy Conservation

In this study, the effect of goal difficulty and frequent feedback for encouraging energy conservation was assessed.

80 families were placed into one of four groups:

Those in the difficult goal group were asked to cut their energy consumption by 20%, while those in the easy group were asked to cut their consumption by 2%. Those in the frequent feedback group were told three times a week how much their consumption had declined.

The only group whose consumption fell a significant amount was the frequent feedback + difficult goal group. For the duration of the study, their consumption fell an average of 14%.

Abstract here .

Interrelationships Among Employee Participation, Individual Differences, Goal Difficulty, Goal Acceptance, Goal Instrumentality, and Performance

Over a ten-week period, weekly productivity goals were either assigned by the manager or set jointly with the employee.

As all 41 subjects were typists, the performance was easy to measure (e.g. it's easy to measure the number of pages typed, the frequency of errors, and so on). The primary purpose of the study was to show that goals that are jointly set will generate more motivation than those which are ‘forced'. This hypothesis was proven wrong. Later studies would show that goal acceptance requires understanding the reasons why a goal was set, not being a part of the goal-setting process .

Other findings from this study:

- Those who had difficult goals performed higher.

- Those with a high need for achievement and an internal locus of control set more difficult goals.

- Goal setting was more effective for those employees with high self-esteem, and for those who felt working harder would be rewarded.

Goal Setting and Task Performance

“Results from a review of laboratory and field studies on the effects of goal setting on the performance show that in 90% of the studies, specific and challenging goals led to higher performance than easy goals, “do your best” goals or no goals. Goals affect performance by directing attention, mobilizing effort, increasing persistence, and motivating strategy development. Goal setting is most likely to improve task performance when the goals are specific and sufficiently challenging, Ss have sufficient ability (and ability differences are controlled), feedback is provided to show progress in relation to the goal, rewards such as money are given for goal attainment, the experimenter or manager is supportive, and assigned goals are accepted by the individual. No reliable individual differences have emerged in goal-setting studies, probably because the goals were typically assigned rather than self-set. Need for achievement and self-esteem may be the most promising individual difference variables.”

Goal Difficulty vs. Performance

“A previous review of the goal-setting literature found strong evidence for a linear relationship between goal difficulty and task performance (assuming sufficient ability), and more recent studies have supported the earlier findings. Four results in three experimental field studies found harder goals led to better performance than easy goals:”

- Increasing Productivity With Decreasing Time Limits: A Field Replication of Parkinson's Law , 1975 (tree logging).

- Interrelationships Among Employee Participation, Individual Differences, Goal Difficulty, Goal Acceptance, Goal Instrumentality, and Performance, 1978 (typists).

- A Study of The Effects of Task Goal and Schedule Choice on Work Performance, 1979.

“Twenty-five experimental laboratory studies have obtained similar results with a wide variety of tasks:”

- Knowledge of Score and Goal Level as Determinants of Work Rate, 1969 (addition).

- Studies of The Relationship Between Satisfaction, Goal Setting, and Performance, 1970 (reaction time and addition).

- The Effects of Participation in Goal Setting on Goal Acceptance and Performance, 1975 (coding task).

- A Two-Factor Model of The Effect of Goal-Descriptive Directions on Learning From Text, 1975 (prose learning).

- Additive Effects of Task Difficulty and Goal Setting on Subsequent Task Performance 1976 (chess).

- Role of Performance Goals in Prose Learning, 1976 (prose learning).

- The Motivational Strategies Used by Supervisors: Relationships to Effectiveness Indicators, 1976 (card sorting).

- Effects Achievement Standards, Tangible Rewards, and Self-Dispensed Achievement Evaluations on Children's Task Mastery, 1977 (color discrimination).

- Systems Analysis of Dyadic Interaction: Prediction From Individual Parameters, 1978 (figure selection task).

- The Interaction of Ability and Motivation in Performance: An Exploration of The Meaning of Moderators, 1978 (perceptual speed).

- Effects of Goal Level on Performance: A Trade-off of Quantity and Quality, 1978 (brainstorming, figure selection and sum estimation tasks).

- Importance of Supportive Relationships in Goal Setting, 1979 (brainstorming).

- The Effects of Holding Goal Difficulty Constant on Assigned and Participatively Set Goals, 1979.

- The Effect of Beliefs on Maximum Weight-Lifting Performance, 1979.

- Another Look at The Relationship of Expectancy and Goal Difficulty to Task Performance, 1980 (perceptual speed).

Goal Specificity vs. Performance

“Previous research found that specific, challenging (difficult) goals led to higher output than vague goals such as “do your best”. Subsequent research has strongly supported these results… Twenty four field experiments all found that individuals are given specific, challenging goals either outperformed those trying to “do their best”, or surpassed their own previous performance when they were not trying for specific goals:”

- Improving Job Performance Through Training in Goal Setting, 1974 (tree logging).

- Changes in Performance in a Management by Objectives Program, 1974 (marketing and production workers).

- Assigned Versus Participative Goal Setting With Educated and Uneducated Woods Workers, 1975 (tree logging).

- The “Practical Significance” of Locke's Theory of Goal Setting, 1975 (truck loading).

- Effects of Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976 (sales personnel).

- Effects of Assigned and Participative Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976 (typists).

- Effect of Performance Feedback and Goal Setting on Productivity and Satisfaction in an Organizational Setting, 1976 (customer service).

- The Role of Proximal Intentions in Self-Regulation of Refractory Behavior, 1977 (dieting).

- Performance Standards and Implicit Goal Setting: Field Testing Locke's Assumption, 1977 (keypunching).

- Blue Collar to Top Executive, 1977 (ship loading).

- Different Goal Setting Treatments and Their Effects on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1977 (maintenance technicians).

- Importance of Participative Goal Setting and Anticipated Rewards on Goal Difficulty and Job Performance, 1978 (engineering and scientific work).

- The Effects of Assigned Versus Participatively Set Goals, and Individual Differences When Goal Difficulty is Held Constant, 1979 (clerical test).

- and performance appraisal activities, coding, managerial training, card sorting, die casting, customer service, and pastry work (see the study for citations).

“Twenty laboratory studies supported the above results either partially or totally (see the study for list).”

Feedback vs. No Feedback

“Integrating the two sets of studies points to one unequivocal conclusion: neither [feedback] alone nor goals alone is sufficient to affect performance. Both are necessary. Together they appear sufficient to improve task performance.”

Why Does Goal Setting Often Lead to Improved Performance?

“1. Direction. Most fundamentally goals direct attention and action. 2. Effort. Since different goals may require different amounts of effort, an effort is mobilized in proportion to the perceived requirements of the goal or task. Thus, more effort is mobilized to work on hard tasks (which are accepted) than easy tasks. Sales (1970) found that higher workloads produce the higher subjective effort, faster heart rates, and higher output per unit time than lower workloads. 3. Persistence . Persistence is nothing more than directed effort extended over time; thus it is a combination of the previous two mechanisms. 4. Strategy Development. While the above three mechanisms are relatively direct in their effects, this last mechanism is indirect. It involves developing strategies or action plans for attaining one's goals.”

Participatory vs. Forced

“Participation has long been recommended by social scientists as a means of getting subordinates or workers committed to organizational goals and/or of reducing resistance to change. However, an extensive review of the participation in decision-making literature by Locke and Schweiger (1979), found no consistent difference in the effectiveness of top-down (“autocratic”) decision making and decisions made with subordinate participation:”

- Goal Characteristics and Personality Factors In a Management By-Objectives Program, 1970.

- Effects of Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976.

- Different Goal Setting Treatments and Their Effects on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1977.

- Assigned Versus Participative Goal Setting With Educated and Uneducated Woods Workers, 1975.

- Effects of Assigned and Participative Goal Setting on Performance and Job Satisfaction, 1976.

- Importance of Participative Goal Setting and Anticipated Rewards on Goal Difficulty and Job Performance, 1978.

- The Effects of Assigned Versus Participatively Set Goals, KR, and Individual Differences When Goal Difficulty is Held Constant, 1979.

- The Effects of Participation in Goal Setting on Goal Acceptance and Performance, 1975.

- Importance of Supportive Relationships in Goal Setting, 1979

“There appear to be two possible mechanisms by which participation could affect task motivation. First, participation can lead to the setting of higher goals that would be the case without participation. Second, participation could, in some cases, lead to greater goal acceptance than assigned goals.”

“Likert has pointed out that when assigned goal setting is effective as in the above studies, it may be because the supervisors who assign the goals behave in a supportive manner. It may be that being supportive is more crucial than participation in achieving goal acceptance. Participation itself, of course, may entail being supportive.”

“Further, it is possible that the motivational effects of participation are not as important in gaining performance improvement as are its cognitive effects . Locke found that the single most successful field experiment on participation to date stressed the cognitive benefits; participation was used to get good ideas from workers as to how to improve performance efficiency.” -Participative Decision-Making: An Experimental Study in a Hospital, 1973.

Full study here .

The Importance of Union Acceptance for Productivity Improvement Through Goal Setting

“Interviews were conducted with union business agents on conditions necessary for their support of a goal-setting program. Subsequent to the interviews, goals were assigned to 39 truck drivers. The results were analyzed using a design that included a comparison group (N= 35). The results showed a significant increase in productivity for the drivers who received specific goals. When the conditions necessary for the union's support of the goal-setting program were no longer met, there was a wildcat strike.” – Abstract