- Open access

- Published: 02 November 2015

A guide to performing a peer review of randomised controlled trials

- Chris Del Mar 1 &

- Tammy C. Hoffmann 1

BMC Medicine volume 13 , Article number: 248 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

15 Citations

35 Altmetric

Metrics details

Peer review of journal articles is an important step in the research process. Editors rely on the expertise of peer reviewers to properly assess submissions. Yet, peer review quality varies widely and few receive training or guidance in how to approach the task.

This paper describes some of the main steps that peer reviewers in general and, in particular, those performing reviewes of randomised controlled trials (RCT), can use when carrying out a review. It can be helpful to begin with a brief read to acquaint yourself with the study, followed by a detailed read and a careful check for flaws. These can be divided into ‘major’ (problems that must be resolved before publication can be considered) and ‘minor’ (suggested improvements that are discretionary) flaws. Being aware of the appropriate reporting checklist for the study being reviewed (such as CONSORT and its extensions for RCTs) can also be valuable.

Competing interests or prejudices might corrode the review, so ensuring transparency about them is important. Finally, ensuring that the paper’s strengths are acknowledged along with a dissection of the weaknesses provides balance and perspective to both authors and editors. Helpful reviews are constructive and improve the quality of the paper. The proper conduct of a peer review is the responsibility of all who accept the role.

Peer Review reports

Peer review of journal articles is an important process in research. It is part of the underlying engine that aims to sort out which papers will be published and what modifications are needed before this occurs.

It is easy to assume that reviewers’ duties and editors’ objectives are identical: we all want to see that good papers are accepted and flawed ones rejected, and that all are papers improved by the review process. In a study of over 200 reviewers of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in high impact medical journals, reviewers ranked activities such as ‘evaluating the risk of bias’, and ‘checking that the conclusions were consistent with the results’, top [ 1 ]. However, the 171 participating editors ranked these much lower, instead wanting to simply know whether the reviewers ‘did or did not recommend publication’ and ‘whether this was an important topic’ [ 1 ].

Editors rely on the expertise of their peer reviewers to provide the necessary background (typically content and/or methodological) to properly assess submissions. While there are imperfections in the peer review system and some doubts about the impact of peer review [ 2 , 3 ], it is a system that is used universally. However, the quality of peer review varies enormously and few reviewers receive training in how to do it and may not be aware of some of the elements to consider or when new to reviewing, how to approach the task. In this paper, we describe some of the main steps that peer reviewers of research papers in general, and RCTs in particular, can use to guide their review.

General steps – for all research articles

Acquaint yourself with the paper.

It is a good idea to read the paper soon after your commission to referee it. Leaving it to the last minute risks introducing a delay if you discover a problem which means that you cannot complete it (for example, a conflict of interest that only emerges after a detailed read or addressing an area in which you have no expertise). In any case, a rapid read allows you to get a fast grasp of the content to prepare you for the full task. Breaking the research study into its component parts can help you to understand the main elements of the study. For those familiar with doing this step in critical appraisal, the example component parts for most RCTs would be: Participants/Patient, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcomes (or PICO). For studies that are not RCTs, many of these components are still relevant – for example, Participants/Problem/Population, Issue/Index (if an observational study), and Outcomes. Identifying what the study’s question is can help to initially orient you to the paper and consider whether the most appropriate study design was used to answer the question posed by the researchers.

Many journals ask their reviewers to classify remaining flaws into ‘major’ (defined as requiring satisfactory resolution before publication can be considered) and ‘minor’ (discretionary, suggestions that might improve the paper, but could be ignored). This is a useful classification system to follow anyway, even if not a requirement of the journal.

Is the quality good enough? Check for major flaws

Among the things that editors have to decide, one of the most essential is whether a paper is fatally flawed. This means that, whatever else – even if a fascinating topic, and beautifully crafted in breathless prose – a critical problem may mean it cannot be published, even with complete overhaul. The word ‘fatal’ implies no hope of resuscitation. Sometimes what appears to be a fatal flaw may actually be inadequate reporting (for example, not reporting ethical approval or trial registration), in which case, stop the review until this is addressed with the authors of the paper (through the editorial office of course – never directly with the authors). The Editor/editorial office may ask the authors to provide more information to resolve the impasse. Some journals screen for certain types of fatal flaws before sending papers for review; others do not. If the issue is not inadequate reporting and there is truly a fatal flaw, stop. There is nothing else necessary to comment on. Focus your report on that fatal flaw; however, do mention that you did not review the remainder of the paper. Your responsibility as a peer reviewer ends when you describe how it is not possible to repair this paper. Bear in mind that what is a ‘fatal’ flaw can be quite subjective and will vary between journals, editors, and reviewers. What some believe is fatal, others may see as a major flaw that is reparable in some way.

Major flaws are serious flaws that must be addressed before publication can be considered appropriate. Some examples of major flaws, that are applicable to many study designs, are provided in Box 1.

Major flaws in RCTs

There are special requirements for the conduct and reporting of RCTs, and peer reviewers should carefully check that these requirements have been met. Unfortunately, peer reviewers are not usually good at detecting these [ 4 ]. In one study, a journal asked 607 peer reviewers to participate and gave them three (previously published) RCTs which were altered so that, after removing the original authors’ names and any other identifying features, nine major errors were deliberately added [ 5 ]; reviewers were able to identify a mean of only 2.6 errors. There have been calls for innovations in providing training to would-be reviewers of RCTs before they can enter a register of ‘RCT reviewers’ that journals could draw upon [ 6 ]. Interventions to improve the quality of peer review have had mixed results when evaluated in RCTs [ 5 , 7 , 8 ]. The most recent trial suggested, although not conclusively, that conducting an additional review based on reporting guidelines might result in small improvements in paper quality [ 8 ].

Critically appraising the RCT to determine its risk of bias, and where necessary, whether this has been appropriately acknowledged, is important. Reviewers who are less experienced with critical appraisal might find using the mnemonic RAMbo useful to assess key types of potential bias: R andomised (was there random allocation, concealed allocation, and baseline similarity of groups?); A ttrition (was there adequate follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, and, aside from the experimental intervention, were the groups treated equally?); and M easurement (was it done by b linded assessors, or were o bjective measures used?).

It is good practice to undertake an extra step in reviewing RCTs, to check either the published protocol, or its registry entry, to establish whether all measured outcomes were reported. The statistical analyses of RCTs sometimes require specialized expertise. If you are unsure whether the analyses have been performed or interpreted correctly, do not be afraid to alert the editor to this and report that a statistical review is also required. Journals often have statistical reviewers they can call on, and alerting the Editors to a specific need may be very helpful.

What else could be improved? Check for minor flaws

Examples of minor flaws include writing that is clumsy; lack of clarity in some of the argument (usually in the Background and/or Discussion); minor details missing or inadequately reported; tables or figures that duplicate the text or, conversely, are not appropriately referred to; unclear tables or figures; or referencing errors. Tables and figures should typically be self-contained. This means that it should be possible to understand them without reference to the text.

Sometimes you might want to debate a statement that you disagree with. Here, we enter a more subjective territory. Some of your comments may be very helpful – and authors may well thank the reviewer for the suggestion (this is common), or refute it with some well-constructed arguments (just as common!). Nevertheless, it is worth labelling your concerns as those suggested improvements which you think the authors need to take up before publication, and those which are best left to the discretion of the authors and editors. Figure 1 provides examples of ‘less helpful’ and ‘more helpful’ reviewer’s comments, on a number of major and minor flaws, for a hypothetical RCT.

Examples of ‘less helpful’ and ‘more helpful’ peer review comments on a hypothetical RCT paper

Using reporting guidelines

Where better to find guidelines about which items are essential for each study design than those intended for use by authors? Reporting guidelines can be used to help inform peer review [ 9 ]. There are reporting guidelines for many of the major study designs. For example, there are reporting statements for RCTs, systematic reviews, observational studies, diagnostic studies, case reports, economic evaluations, and even for protocols of studies. A complete list of reporting guidelines is maintained by the EQUATOR Network [ 10 ].

Reporting guideline checklists follow the flow of the paper, presenting items in approximately the order encountered, from the Introduction through to Discussion (Fig. 2 ). Many, but not all journals require that authors provide a completed checklist for a submitted paper, indicating where each checklist item has been addressed. Some journals assess the checklist in the editorial office, others expect reviewers to. It is good practice for reviewers to examine the checklist, if provided, to ensure that all items have been adequately addressed. As well as being familiar with the checklist items, reviewers who are not familiar with the relevant reporting guideline may find it helpful to read the full explanation and elaboration paper that accompanies the reporting guideline to understand the rationale for each item and see examples of ‘good’ reporting.

The CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) checklist, available at http://www.consort-statement.org/

Noting reporting guideline items that have not been reported, or not reported well, should be included in your review. You might detect a major flaw, such as inappropriate statistical analyses or something that has increased the study’s risk of bias but has not been appropriately explained or accounted for in the limitations and interpretations of the results. However, not adhering to a reporting item does not necessarily constitute a major flaw: missing information might simply reflect the author not reporting specific or enough information in the paper, something which might be easily resolved at the revision stage, and so might be more appropriate to classify as a minor flaw.

The journal that you are reviewing for might also have specific requirements. For example, the BMJ now requires a statement about patient involvement in setting the research question, and the design, implementation, and dissemination of the research [ 11 ]. These additional requirements will typically be communicated to you when the paper is sent to you for review.

Reporting guidelines for RCTs

The CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement has been available for many years now (Checklist in Fig. 1 ). Over the years, a number of CONSORT extension statements have been developed [ 12 ]. Whether to use the main CONSORT statement or an extension depends on the RCT that you are reviewing. Some extensions are specific to the design of the RCT – for example, there is an extension for cluster RCTs [ 13 ] and one for pragmatic RCTs [ 14 ]. Others are specific to the type of data that were collected, such as the extension for reporting harms outcomes [ 15 ]. Other extensions are generic and are intended to be used with most RCTs, regardless of the design or data – for example, the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guide, is an extension to item 5 of CONSORT and provides guidance for how to describe the intervention that was evaluated [ 16 ]. Familiarizing yourself with the CONSORT statement and its various extensions so that you know which to use during peer review is a good idea.

Final thoughts

Dealing with your own biases, prejudices, and conflicts of interest.

Sometimes you will be asked to comment on a paper that is antithetical to your point of view. It is important that your own position does not make you overly critical – and similarly, papers that exactly reinforce your approach should not receive a less critical review. For many journals, you will be asked to complete a declaration of Conflict of Interest (also called, perhaps more accurately, a ‘Competing Interests’) form. You can list your prejudices here among the usual questions about whether you have financial or non-financial interests that might be advantaged or disadvantaged by publication of the paper. This will enable the Editor to evaluate your comments appropriately.

While the rejection of a paper can be demoralizing, all authors experience it at some stage and constructive reviews improve papers. Because publication in quality journals can influence careers in a very competitive world, rejection can exact a heavy toll. Reviewers have a responsibility to deliver criticisms carefully and constructively. There is usually something good about every paper that you can find to comment on. Making some positive and constructive comments to go with the disagreeable ones about aspects of the paper that need to be improved can help to keep your review balanced. Of course, positive comments must not be overdone in poor quality papers – this can create problems for the Editors if the Authors subsequently appeal: “ How can you reject my paper when… ”, or even “ Why should I revise it? ……the reviewers thought it was fine! ”

Confidentiality and fully disclosed comments

Different journals have widely different policies. The usual system allows your comments, which are written anonymously, to be read by the submitting authors (who may also be anonymous), with an additional place to provide confidential comments that the paper authors do not see. This can be used to advise the editors about something very sensitive – for example, that you suspect plagiarism or research misconduct, or that you have some personal thoughts that you need to keep private for some reason. Otherwise, anything you have to say should be said transparently to the Authors just as much as the Editors.

Many journals now make the identity of the reviewer as well as the authors open (and not just to each other; some journals also post reviewers’ comments online alongside the final published article). But in any case, always imagine that your identity is known to the authors, and afford respect and courtesies accordingly. In other words, never hide behind anonymity (if that is the journal’s protocol) to write rude or ad hominem comments.

Don’t be late

Many authors wait anxiously for news of their paper from the journal. It seems to take forever, and the delay is often very costly for them – they cannot easily progress with a second paper, they need the publication for promotion or a grant application, and so on. The rate-limiting step can sometimes be finding appropriate people who agree to review the paper and then waiting for the reviewers’ reports to be submitted. If you commit to doing the review, make sure you include the ‘complete-by’ date in that commitment. Many journals have elaborate reminder systems. Additional delay is as discourteous as a rude comment.

Before hitting submit

We all have more to do than time to do it, and it can sometimes be tempted to rush the completion of a refereeing task. Check it for typographical and grammatical errors (it is particularly galling for an author to be criticized for typos from a review peppered with them), as well as general sense.

Conclusions

The role of a reviewer comes with responsibility. The contribution that peer review can make to ensuring that published research is valid and clearly reported is often influenced by the quality of the peer review itself. Performing peer review of papers is an important contribution that every researcher needs to make, and it can be rewarding for a variety of reasons – including that, by reviewing papers, you learn to identify errors which you may then be less likely to make yourself. Developing solid skills in peer reviewing research papers is as important a skill as being able to write one.

Box 1 Examples of major flaws that must be addressed before publication is possible

Major flaws - research papers in general

Required ethics approval, and participant consent, was not obtained. This may be considered a fatal flaw by most journals;

Methods that are not described sufficiently well to enable replication of the study;

Post hoc analyses – that is, analyses that are undertaken after the data are collected and examined, but were not planned beforehand ( a priori ). The danger of doing this is that interesting analyses might be presented, while uninteresting ones are not, thereby introducing a bias. If performed, post hoc analyses should be carefully labelled as such to avoid confusion, or, only be presented as hypothesis-generating, to be formally tested in a future study;

Important and relevant research not cited (especially studies with results that contradict the study being reviewed);

Study limitations not adequately acknowledged;

Conclusions that do not match the results and are not supported by data.

Major flaws - RCTs

The trial was not prospectively registered in an appropriate trial registry, prior to the recruitment of participants. This is fatal for many (but not all) journals [ 17 ], and one alternative (not as ideal as prospective registration, but better than non-publication) is to deposit results with an acceptable registry. Mandating the registration of trials is designed to reduce bias in the literature that occurs from the differential publishing of studies with positive (or ‘interesting’) results rather than negative ones, leaving the literature (as reflected in systematic reviews, for example) with a positive bias [ 18 ]. It also prevents bias from the post hoc analyses of subgroups discussed in Box 1.

Chauvin A, Ravaud P, Baron G, Barnes C, Boutron I. The most important tasks for peer reviewers evaluating a randomized controlled trial are not congruent with the tasks most often requested by journal editors. BMC Med. 2015;13:158.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kravitz RL, Franks P, Feldman MD, Gerrity M, Byrne C, Tierney WM. Editorial peer reviewers' recommendations at a general medical journal: are they reliable and do editors care? PLoS One. 2010;5:e10072.

Stahel PF, Moore EE. Peer review for biomedical publications: we can improve the system. BMC Med. 2014;12:179.

Hopewell S, Collins G, Boutron I, Yu L, Cook J. Impact of peer review on reports of randomized trials published in open peer review journals: retrospective before and after study. BMJ. 2014;349:g4145.

Schroter S, Black N, Evans S, Godlee F, Osorio L, Smith R. What errors do peer reviewers detect, and does training improve their ability to detect them? J R Soc Med. 2008;101:507–14.

Patel JB. Why training and specialization is needed for peer review: a case study of peer review for randomized controlled trials. BMC Med. 2014;12:128.

Jefferson T, Alderson P, Wager E, Davidoff F. Effects of editorial peer review: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:2784–6.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cobo E, Cortés J, Ribera JM, Cardellach F, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Kostov B, et al. Effect of using reporting guidelines during peer review on quality of final manuscripts submitted to a biomedical journal: masked randomised trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d6783.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hirst A, Altman DG. Are peer reviewers encouraged to use reporting guidelines? A survey of 116 health research journals. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35621.

Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. Essential resources for writing and publishing health research. www.equator-network.org . [accessed 10 Sept 2015].

BMJ Patient Partnership. 2015. http://www.bmj.com/campaign/patient-partnership [accessed 10 Sept 2015].

CONSORT. Transparent reporting of trials. http://www.consort-statement.org/ [accessed 10 Sept 2015]

Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661.

Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ. 2008;337:a2390.

Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gøtzsche PC, O’neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, et al. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:781–8.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). http://publicationethics.org/case/it-unethical-reject-unregistered-or-late-registered-trials . [accessed 10 Sept 2015].

DeAngelis CD, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration: A statement from the international committee of medical journal editors. JAMA. 2004;292:1363–4.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the reviewers of this article, Harriet MacMillan and Caroline Sabin who provided very constructive comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Research in Evidence-Based Practice, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Gold Coast, Queensland, 4229, Australia

Chris Del Mar & Tammy C. Hoffmann

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chris Del Mar .

Additional information

Competing interests.

CDM has no competing interests to declare. TCH is part of the author team that developed the TIDieR Statement.

Authors’ contributions

CDM was invited to contribute the article. Both CDM and TCH equally sketched out the plan, and equally contributed to the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Authors’ information

CDM is Professor of Public Health and an academic general practitioner at the Centre for Research in Evidence Based Practice at Bond University, Queensland, Australia. He is the coordinating editor of the Acute Respiratory Infection Group of the Cochrane Collaboration; has acted as a deputy editor for the Medical Journal of Australia; a member of the editorial board of BMC Medicine, and a member of the international advisory committee of the BMJ. TCH is Professor of Clinical Epidemiology at the Centre for Research in Evidence Based Practice at Bond University and a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Research Fellow. She is an editorial board member for three journals. Some of her research focusses on the usability and quality of research evidence and she led the development of the TIDieR statement (CONSORT extension statement for intervention reporting). TCH and CDM are co-authors of a book on evidence-based practice.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Del Mar, C., Hoffmann, T.C. A guide to performing a peer review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Med 13 , 248 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0471-8

Download citation

Received : 15 May 2015

Accepted : 01 September 2015

Published : 02 November 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0471-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- CONSORT statement

- Editorial responsibilities

- Medical journal publishing

- Peer review

- Randomised controlled trial

View archived comments (1)

BMC Medicine

ISSN: 1741-7015

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Library Services

UCL LIBRARY SERVICES

- Guides and databases

- Library skills

LibrarySkills@UCL for NHS staff

- Critical Appraisal of a quantitative study (RCT)

- Library skills for NHS staff

- Accessing resources

- Evidence-based resources

- Bibliographic databases

- Developing your search

- Reviewing and refining your search

- Health management information

- Critical appraisal of a qualitative study

- Critical appraisal of a systematic review

- Referencing basics

- Referencing software

- Referencing styles

- Publishing and sharing research outputs

- Publishing a protocol for your systematic or scoping review

- Communicating and disseminating research

- Help and training

Critical appraisal of a quantitative study (RCT)

The following video (5 mins, 36 secs.) helps to clarify the process of critical appraisal, how to systematically examine research, e.g. using checklists; the variety of tools /checklists available, and guidance on identifying the type of research you are faced with (so you can select the most appropriate appraisal tool).

Critical appraisal of an RCT: introduction to use of CASP checklists

The following video (4 min. 58 sec.) introduces the use of CASP checklists, specifically for critical appraisal of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) study paper; how the checklist is structured, and how to effectively use it.

Webinar recording of critical appraisal of an RCT

The following video is a recording of a webinar, with facilitator and participants using a CASP checklist, to critically appraise a randomised controlled trial paper, and determine whether it constitutes good practice.

'Focus on' videos

The following videos (all approx. 2-7 mins.) focus on a particular aspects of critical appraisal methodology for quantitative studies.

- << Previous: Evaluating information & critical appraisal

- Next: Critical appraisal of a qualitative study >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:57 AM

- URL: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/nhs

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Evaluation of reporting quality of randomized controlled trials in patients with COVID-19 using the CONSORT statement

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ These authors share first authorship on this work.

Affiliation School of Nursing, Gansu University of Chinese Medicine, Lanzhou, China

Roles Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Lanzhou Hand and Foot Surgery Hospital, Lanzhou, Gansu, China

Roles Data curation, Validation

Roles Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Educational Department, Gansu Provincial Hospital, Lanzhou, Gansu, China

- Yuhuan Yin,

- Fugui Shi,

- Yiyin Zhang,

- Xiaoli Zhang,

- Jianying Ye,

- Juxia Zhang

- Published: September 23, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

To evaluate the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) regarding patients with COVID-19 and analyse the influence factors.

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library databases were searched to collect RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19. The retrieval time was from the inception to December 1, 2020. The CONSORT 2010 statement was used to evaluate the overall reporting quality of these RCTs.

53 RCTs were included. The study showed that the average reporting rate for 37 items in CONSORT checklist was 53.85% with mean overall adherence score of 13.02±3.546 (ranged: 7 to 22). The multivariate linear regression analysis showed the overall adherence score to the CONSORT guideline was associated with journal impact factor (P = 0.006), and endorsement of CONSORT statement (P = 0.014).

Although many RCTs of COVID-19 have been published in different journals, the overall reporting quality of these articles was suboptimal, it can not provide valid evidence for clinical decision-making and systematic reviews. Therefore, more journals should endorse the CONSORT statement, authors should strictly follow the relevant provisions of the CONSORT guideline when reporting articles. Future RCTs should particularly focus on improvement of detailed reporting in allocation concealment, blinding and estimation of sample size.

Citation: Yin Y, Shi F, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Ye J, Zhang J (2021) Evaluation of reporting quality of randomized controlled trials in patients with COVID-19 using the CONSORT statement. PLoS ONE 16(9): e0257093. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093

Editor: Daoud Al-Badriyeh, Qatar University, QATAR

Received: April 24, 2021; Accepted: August 23, 2021; Published: September 23, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Yin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The study was funded by Horizontal project of School of Public Health of Lanzhou University “Research on the Thinking, difficulties and Countermeasures of High-quality Development of Lanzhou Hand and Foot Surgery Hospital” (071100278), Gansu Science and Technology Plan (Innovation Base and Talent Plan) project (21JR7RA607), and Health industry scientific research project of Gansu Province (GSWSKY-2019-50), received by Fugui Shi and Juxia Zhang.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

With the development of evidence-based medicine, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) became the gold standard to compare the effectiveness of different interventions [ 1 ]. It can avoid possible bias in clinical trial design, balance confounding factors and improve the effectiveness of statistical tests [ 2 ]. Therefore, a complete and accurate report will enable readers to fully assess the authenticity of results [ 2 ]. If the RCT report is unsatisfactory, the validity of trials will be reduced [ 3 ], which may adversely affect the results of meta-analyses and recommendations for clinical practice [ 4 ].

To improve the reporting quality of RCTs, the CONSORT (reporting standards of randomized controlled trials) statement was developed in 1996 [ 5 ], revised in 2001 [ 6 ] and 2010 [ 7 ]. The updated CONSORT statement includes 25 entries that provide specific guidance for RCT reports. Since many of the 25 items were subdivided into two subitems, the list actually consists of 37 items [ 7 ]. It is currently known to be endorsed by over 600 biomedical journals and endorsed by several prominent editorial organizations including the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and the World Association of Medical Editors (WAME) [ 8 ]. After update of CONSORT statement, the overall reporting quality of RCTs has improved, but there were still many RCT reports with various deficiencies [ 9 , 10 ]. A study by Yao et al. of 65 RCTs related to ophthalmic surgery showed the mean CONSORT score was 8.9 (range 3.0–14.7) and the reporting quality was quite low [ 11 ]. A study of 71 RCTs regarding herbal interventions showed that the compliance rates of CONSORT checklist in these RCTs ranged from 0% to 97.18% [ 12 ]. Poor reporting quality of RCTs is the major barrier to evidence-based practices, as it can distort the available evidences in the medical literature, and prevent clinical decision-makers from obtaining true results from trials [ 13 ]. Thus, it is critical for researchers to build well-reported standard of RCTs. On the one hand, it can ensure the validity of clinical trials and the authenticity and scientificity of research results [ 14 ]. On the other hand, it is conducive to conducting secondary studies, such as meta-analyses and systematic reviews [ 15 ].

With the outbreak of the COVID-19 in 2019, in order to quickly and effectively control the epidemic, a large number of RCTs regarding COVID-19 have been published. However, the reporting quality of these RCTs is unclear, to our knowledge, no study has specifically evaluated the reporting quality of RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19.

The primary objective of our study was to assess the reporting of RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19 and analyze possible related factors, so as to provide theoretical basis for subsequent studies and meta-analyses.

Ethical review

Ethical approval was not necessary for this study, as the study did not involve patients and included RCTs can be traced from databases.

Search strategy

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library databases were searched to collect RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19. The retrieval time was from the inception to December 1, 2020. The search was conducted by two investigators and the detailed strategy was shown in S1 File .

Study selection

Studies meeting the following criteria were enrolled in the study: (1) Randomized controlled trial. (2) The confirmed or suspected patients of COVID-19 according to the diagnostic criteria of "the latest Clinical guidelines for novel coronavirus" issued by the World Health Organization (WHO). (3) Interventions related to patients or suspected patients.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) Animal experiments, reviews, systematic reviews, case reports. (2) Repeated publications. (3) The abstract or full text is not available.

The titles of the retrieved article were imported into the Endnote X9 and screened by 2 reviewers independently. We first reviewed the title and abstract of each article and decided to regard its appropriateness for inclusion. In case of doubt, we downloaded full texts to judge whether an article was RCT. Any disagreement was solved by consensus.

Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted the general characteristics and reporting data of included studies into Excel, any discrepancy was resolved through discussion. The general characteristics include continent of first-author, number of authors, sample size, age and type of participants, the type of interventions, journal impact factor and journals’ endorsement of the CONSORT statement.

Assessment of reporting quality

The CONSORT statement was chosen as a tool to assess reporting quality of these RCTs [ 7 ]. We assessed the compliance of each RCT by 25 items of CONSORT statement, each checklist item and subitem was answered with “yes” or “no”. According to the above items, the coincidence rate of each item of 53 studies was counted one by one. A point for the item being granted if all sub-sections were answered as yes, if one of two subsections was reported, a score of 0.5 was awarded, then total score of each study was calculated [ 1 ]. Items 3b, 6b, and 14b are not necessarily applicable, if relevant, the article will be graded according to the above guidelines, if the article did not apply to this item, no points was deducted [ 3 ].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was performed to describe general characteristics of 53 studies and the reporting rate of each checklist item/subitem. We used the k coefficient to determine the degree of agreement between reviewers. T-test and ANOVA were used for univariate analysis, multiple linear regression analyses were used to determine the association between potential predictors and reporting quality. All significant predictors in the univariable analyses were entered individually into a multivariable analysis. No significant violation of normality was found in assessments of the residuals. Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze the relationship between journals impact factor and endorsement of CONSORT guideline, T-test was used to analyze the differences between different journal submission requirements and CONSORT score. For all analyses, the statistical significance level was set at P<0.05. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 21.

Search results

Initially, 8700 articles were obtained, excluding duplicates, 6,922 studies was remained. After screening the titles and abstracts, 198 potentially eligible articles were identified. Subsequently full text of each article was retrieved, and 53 RCTs were confirmed for further assessment. Fig 1 outlined the search detail via the PRISMA flow diagram.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.g001

Agreement of reviewers

In the pilot study, inter-observer concordance for article selection had a kappa score of 0.78, which was 0.89 after resolving all disputed items by a discussion with the third reviewer (ZJX), suggesting that inter-observer reliability was almost perfect.

Characteristics of included studies

Among the 53 RCTs, the first author of most RCTs were from Asia and accounted for 62.26%, half of the studies had a sample size greater than 100, 50 studies (94.34%) used drug interventions. 22 (42.51%) studies had an impact factor of more than 10. Nearly half of the studies were published in journals that did not explicitly require authors to follow the CONSORT statement. As showed in Table 1 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.t001

The evaluation result of the CONSORT checklist

The study showed that the average reporting rate for 37 items in CONSORT checklist was 53.85%, with 31.35% for the methodological section. Items with the reporting rate of more than 80% were abstract, background, eligibility criteria for participants, outcomes, statistical methods, participant flow chart, baseline data, limitations, generalisability and funding. Except for non-essential items, the remaining items with the reporting rate of less than 20% were trial design, sample size, allocation concealment, implementation, blinding, ancillary analyses and protocol. Only 7 studies (13.21%) reported the methods of masking concealment and 9 studies (16.98%) reported the details of the blinding. Table 2 outlined the reporting frequency of each checklist item.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.t002

The CONSORT average score for all study was 13.02±3.546, 95%CI (12.06–13.97).

Factors of effecting overall reporting score

Univariate results showed that CONSORT score was associated with sample size (P<0.001), types of intervention (P = 0.017), journal impact factor (P<0.001), and endorsement of CONSORT statement (P<0.001) ( Table 1 ).

Table 3 displayed the results of multiple linear regression analysis. The four predictors were entered into a multivariable model (constant = 7.779, R 2 = 0.533, adjusted R 2 = 0.494, P<0.001). Among these, journal impact factor (P = 0.006), and journal with endorsement of CONSORT statement (P = 0.014) still persisted as noticeable predictors of reporting quality.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.t003

Journal impact factors less than 10 and more than 10 had statistically significant differences in endorsement of the CONSORT statement (P<0.001) ( Table 4 ). There was a statistically significant difference in reporting quality between journals that required submission of CONSORT checklist and those that did not (P = 0.031) ( Table 5 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.t004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.t005

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the reporting quality of RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19 by the CONSORT statement [ 7 ], this will provide important information for clinical decision makers. Our study showed that the overall reporting quality of RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19 was suboptimal. It is clear that the reporting quality of these studies needs to be improved, particularly in terms of methodology section.

Although the CONSORT statement was established to ensure the completeness and accuracy of RCT reports, our study found that some authors still reported their data selectively in a biased way, with the average reporting rate of 53.85%, none of the RCTs provided complete information as required, similar results have been found in other studies [ 11 , 16 – 18 ]. This could be due to the large number of patients with COVID-19 emerging in a short period of time, in order to present positive results of various treatment regimens to readers as soon as possible, researchers may have paid more attention to the results of study than report specifications.

The key items with lower reporting rates were mainly concentrated in trial design, sample size, allocation concealment, and blinding. The complete description of trial design can provide readers with accurate research ideas and enable readers to better evaluate the trial results [ 19 ], but our study showed that only 5 (9.43%) studies reported the type of trial design. The neglect of two most important items in the methodology section (allocation concealment and details of blinding) was particularly worrisome, as these items are important information to ensure the authenticity of results [ 20 ]. Only 7 (13.21%) studies described the methods of allocation concealment, 9 (16.98%) studies reported the details of blinding. We found that some authors tend to write “single” or “double” blind rather than specifying exactly who were unaware of treatment identities. The low reporting rates of these items may reflect the lack of relevant knowledge of researchers to some extent, because the report of sequence generation and concealment of allocation need to have certain knowledge of clinical research methodology [ 21 ]. There was evidence that trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment overestimated the treatment effects up to 7% [ 22 ], and a meta-epidemiological study of blinding showed that unblinded RCTs overestimated the outcome effect by 0.56 standard deviations [ 23 ]. In spite of this, some studies still reported these items poorly [ 11 , 17 , 24 ]. A previous study showed that only 12% and 21% of RCTs reported the details of allocation concealment and blinding in four high-impact general medical journals [ 25 ]. What’s more, a study of acute herpes zoster showed that none of RCTs reported blinding and masking [ 16 ]. Therefore, it is urgent for researchers to pay attention to the design and implementation of allocation concealment and blinding, in order to minimize measurement bias and improve the reporting quality of RCTs. The estimation of sample size can avoid false negative results between the intervention and control groups [ 26 ]. Our study showed that only 5 studies (9.43%) reported the details of sample size, which was similar to the results in the field of vascular and endovascular surgery, herpes zoster and plastic surgery [ 9 , 16 , 27 ]. Lack of the reporting of sample size estimation can prevent readers to verify the validity of the trial results [ 27 ], researchers should attach great importance to the report of sample size estimation, so as to provide scientific evidence for future clinical studies.

Our study showed that reporting quality was associated with journal impact factor and endorsement of the CONSORT statement, similar results have been found in other areas [ 15 , 27 – 29 ]. Studies have shown that 80% of RCTs published in journals that do not endorse CONSORT guideline had defective reporting specifications [ 30 ]. We found that journals with impact factor of more than 10 have a higher endorsement of the CONSORT guideline. However, even though some journals have endorsed the CONSORT guideline, the reporting quality of published RCTs was still suboptimal, this may be due to a problem with the entry point for paper submission. We found that some journals only encourage researchers to follow the CONSORT guideline, but do not require authors to submit a CONSORT checklist, which was more common in journals with lower impact factor, this may be because journals with lower impact factor have less stringent policies for accepting and publishing papers. In contrast, journals with higher impact factor have stricter requirements for submission of articles, requiring authors to upload CONSORT checklist when submitting RCT, which forces researchers to write RCTs according to standard reporting specifications. Our study showed that articles that uploaded the CONSORT checklist had higher reporting quality than those that did not have strict submission requirements, therefore, strict submission requirements are the premise to improve the reporting quality of RCTs.

Academic journals are the main media for carrying and publishing papers, the relevant provisions in the manuscript contract will directly affect the quality of published papers [ 28 , 30 ]. Thus, we suggest that editors should carefully assess whether their journals’ submission requirements are normative, journals should not only endorse the CONSORT guideline, but more importantly require authors to upload the CONSORT checklist as key material for the initial screening when submitting their RCTs. Similarly, peer reviewers should check the completeness and accuracy of CONSORT checklist when reviewing RCTs, editorial boards should also increase their oversight of the entire process from submission to publication, articles of lower reporting quality will not be published. However, in addition to problems in the whole process of submission requirements, review and publication, another potential reason for the poor reporting quality of RCTs is that the CONSORT statement was not publicized enough, researchers lack the awareness of report guideline [ 31 ]. A survey of the authors of 101 studies found that only 3% acknowledged the importance of RCT reports and followed the CONSORT guideline when writing papers [ 31 ], this suggests that improving researchers’ awareness of the CONSORT guideline is critical to improve the reporting quality of RCTs. Therefore, on the one hand, journals should vigorously promote the CONSORT guideline and can add relevant knowledge of RCT reports to their subscription feeds. On the other hand, research institutions should also increase training in these problems to improve the reporting quality of RCTs.

Limitations of this study

There are some limitations in our study. Although the literature retrieval, screening and quality evaluation were carried out simultaneously by two researchers, there was still some subjectivity. In addition, we only included RCTs of patients with COVID-19 from 4 databases, it could not represent the overall reporting quality of RCTs of COVID-19.

Conclusions

The primary objective of our study was to provide readers a broad overview of the reporting characteristics of RCTs regarding patients with COVID-19. The overall reporting quality of these RCTs was suboptimal, thereby diminishing their potential usefulness, and it can not provide valid evidence for clinical decision-making and systematic reviews. Better reporting quality was associated with higher journal impact factor and endorsement of the CONSORT statement. More journals should endorse the CONSORT statement, authors should strictly follow the relevant provisions of the CONSORT guideline when writing the paper. Future RCTs should particularly focus on improvement of detailed reporting in allocation concealment, blinding and estimation of sample size.

Supporting information

S1 file. search strategy..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257093.s001

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bin Ma (Evidence-Based Medicine Center, Institute of Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu, China) for providing assistance with editing the final manuscript.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 8. CONSORT website. http://www.consort-statement/about-consort/endorses . [cited 18 March 2021].

Making sense of research: A guide for critiquing a paper

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Griffith University, Meadowbrook, Queensland.

- PMID: 16114192

- DOI: 10.5172/conu.14.1.38

Learning how to critique research articles is one of the fundamental skills of scholarship in any discipline. The range, quantity and quality of publications available today via print, electronic and Internet databases means it has become essential to equip students and practitioners with the prerequisites to judge the integrity and usefulness of published research. Finding, understanding and critiquing quality articles can be a difficult process. This article sets out some helpful indicators to assist the novice to make sense of research.

Publication types

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Research Design

- Review Literature as Topic

Quality Signaling and Demand for Renewable Energy Technology: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment

Solar technologies have been associated with private and social returns, but their technological potential often remains unachieved because of persistently low demand for high-quality products. In a randomized field experiment in Senegal, we assess the potential of three types of quality signaling to increase demand for high-quality solar lamps. We find no effect on demand when consumers are offered a money-back guarantee but increased demand with a third-party certification or warranty, consistent with the notion that consumers are uncertain about product durability rather than their utility. However, despite the higher willingness to pay, the prices they would pay are still well below market prices for the average household, suggesting that reducing information asymmetries alone is insufficient to encourage wider adoption. Surprisingly, we also find that the effective quality signals in our setting stimulate demand for low-quality products by creating product-class effects among those least familiar with the product.

The team is grateful to the joint Lighting Africa program of the World Bank and International Finance Cooperation and to the World Bank Energy & Extractives Global Practice for financial support and feedback during the impact-evaluation design and implementation. In particular, we thank Raihan Elahi and Olivier Gallou for their review of the initial design and guidance on Lighting Africa and Lighting Global materials and objectives. We also thank Ousmane Sarr (ASER), Michele Laleye (Total Senegal), and the World Bank Senegal Country Office team—including Chris Trimble, Manuel Berlengiero, Eric Dacosta, Micheline Moreira, and Aminata Ndiaye Bob—for support and recommendations throughout the project. The work was made possible by the excellent field and research assistance led by Marco Valenza and supported by Amadou Racine Dia. We also thank Kevin Winseck and seminar participants at Leibniz University Hannover, University of Passau, KDI School-World Bank DIME Conference (online), German Development Economics Conference (Stuttgart), NOVAFRICA Conference on Economic Development (Lisbon), and London School of Economics for valuable comments and suggestions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank and its affiliated organizations, nor those of the executive directors of the World Bank, nor the governments they represent, nor the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

Non-communicable diseases, digital education and considerations for the Indian context – a scoping review

- Anup Karan 1 ,

- Suhaib Hussain 1 ,

- Lasse X Jensen 2 ,

- Alexandra Buhl 2 ,

- Margaret Bearman 3 &

- Sanjay Zodpey 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1280 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

45 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction

The increasing ageing of the population with growth in NCD burden in India has put unprecedented pressure on India’s health care systems. Shortage of skilled human resources in health, particularly of specialists equipped to treat NCDs, is one of the major challenges faced in India. Keeping in view the shortage of healthcare professionals and the guidelines in NEP 2020, there is an urgent need for more health professionals who have received training in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of NCDs. This paper conducts a scoping review and aims to collate the existing evidence on the use of digital education of health professionals within NCD topics.

We searched four databases (Web of Science, PubMed, EBSCO Education Research Complete, and PsycINFO) using a three-element search string with terms related to digital education, health professions, and terms related to NCD. The inclusion criteria covered the studies to be empirical and NCD-related with the target population as health professionals rather than patients. Data was extracted from 28 included studies that reported on empirical research into digital education related to non-communicable diseases in health professionals in India. Data were analysed thematically.

The target groups were mostly in-service health professionals, but a considerable number of studies also included pre-service students of medicine ( n = 6) and nursing ( n = 6). The majority of the studies included imparted online learning as self-study, while some imparted blended learning and online learning with the instructor. While a majority of the studies included were experimental or observational, randomized control trials and evaluations were also part of our study.

Digital HPE related to NCDs has proven to be beneficial for learners, and simultaneously, offers an effective way to bypass geographical barriers. Despite these positive attributes, digital HPE faces many challenges for its successful implementation in the Indian context. Owing to the multi-lingual and diverse health professional ecosystem in India, there is a need for strong evidence and guidelines based on prior research in the Indian context.

Peer Review reports

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) kill 41 million people each year. Of these deaths, more than 15 million happen to people between the ages of 30 and 69 years, and the vast majority of these “premature” deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [ 1 ]. It is estimated that by 2030 the share of NCDs in global total mortality will be 69% – a dramatic rise from 59% in 2002 [ 2 ]. Although the burden of NCDs continues to increase across all regions of the world, it disproportionately affects poorer regions [ 3 ], with almost 80% of NCD-related deaths occurring in LMICs [ 4 ].

This shift is largely driven by demographical and epidemiological transitions, coupled with rapid urbanization and nutritional transitions in LMICs [ 5 ].

With approximately six million annual deaths from NCDs, India presents an important case study with respect to these challenges [ 6 ]. Similar to many other LMICs, India is experiencing a rapid health transition with a rising burden of NCDs now surpassing the burden of communicable diseases [ 7 ]. In India, NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes are estimated to account for around 63% of all deaths, thus making them the leading causes of death [ 6 ]. This NCD burden has severe implications for the healthcare system. In particular, the shortage of skilled health professionals, i.e. medical specialists, nurses, and other professionals equipped to treat NCDs, presents a serious challenge [ 8 ]. The inadequacy of educational institutions to impart quality medical and nursing education has been one of the main reasons for the health workforce shortage [ 8 ]. In a recent study, the number of Indian doctors and nurses/midwives was estimated at 0.80 million and 1.40 million, with a density of 6.1 and 10.6, respectively, per 10,000 population. The numbers further drop to 5.0 and 6.0 per 10,000 population, respectively, after accounting for the adequate qualifications [ 9 , 10 ]. All these estimates are well below the WHO threshold of 44.5 doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000 population [ 11 ]. The study also highlights the highly skewed distribution of the health workforce across states, rural–urban and public–private sectors. The skewed distribution of the health workforce across India means that this shortage is even more grave in rural and remote areas [ 9 , 10 ]. The revised guidelines of the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases (NP-NCD), are a welcome strategy in the prevention and control of NCDs [ 12 ]. The focus of the guidelines on health promotion, early diagnosis and screening, and capacity building of healthcare professionals will definitely push for increased attention to the management of NCDs and how this relates to the pre- and in-service training needs of health professionals. In addition, the recent establishment of Health and Wellness Centres (HWC) in managing NCDs and achieving UHC is an excellent response to the changing demographic and epidemiological profile in India. However, this initiative is not without challenges, with a major challenge being the need to build human resource capacity with a continued need for training [ 13 , 14 ]. Although some states have conducted specific training programs to improve the capacity and address the issue, the lack of training modules for NCD management remains an important challenge to be addressed [ 14 ]. The need to strengthen the HWCs through adequate financing, human resources, and logistics for medicines and technology, especially in hard geographical areas, is an area to be focussed upon [ 13 ].

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 by the government of India has highlighted the role of digital education in training and continuing education [ 15 ]. Digital education is defined as an act of teaching and learning by means of digital technologies involving a multitude of educational approaches, concepts, methods, and technologies [ 16 ]. The NEP 2020 focuses attention on implementing and strengthening multidisciplinary, inclusive and technology-based learning that is accessible to all. With a large geographical and cultural diversity in India, meeting this need has proven to be a challenge to India’s existing systems of health professions education (HPE). Hence, the use of technology in education is proposed as a way to access remote areas and bypass geographical barriers [ 15 ].

Although the NEP 2020 has some aspirational objectives, there is a lack of specific knowledge regarding the digital education of health professionals in India. A recent review of Indian research in digital health professions education found that the body of literature is very limited and that the studies that do exist tend to take the form of evaluations of local educational interventions rather than more systematic contributions to research-based knowledge [ 17 ].

Considering the scarcity of empirical evidence related to digital education and training of health professionals regarding NCDs, it is relevant to look outside of India and explore what research may have been done in other contexts.

Digitalization of education may help us address the urgent need for more health professionals who have received training in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of NCDs. However, it is still unclear what constitutes best practice in NCD-related digital education, and how experiences from across the world are relevant to the Indian context.

The objective of the present paper is to conduct a scoping review of the published research examining the digital education of health professionals within NCD topics. More specifically the paper aims to: (i) assess the strengths and weaknesses of the digital teaching-learning practices described in the literature; and (ii) discuss the findings in relation to the Indian context.

The scoping review methodology is appropriate for exploring the extent of research activity within a topic where the literature is limited and disorganized. With a more flexible approach than what is known from systematic reviews, the scoping methodology can provide an overview of what kinds of evidence exist and help inform future research [ 18 ].

To identify relevant publications, we searched four research databases (Web of Science, PubMed, EBSCO Education Research Complete, and PsycInfo). This was done with a search string consisting of three elements, namely terms related to digital education ( n = 174), terms related to health professions ( n = 30), and terms related to NCD ( n = 36). The search string with all terms is included in the online supplementary material .

The search produced 1032 hits combined from all the databases (Web of Science: 443; PubMed: 259; EBSCO Education Research Complete: 118; PsycInfo: 212). When searching, we did not limit the search to any specific time frame, but subsequently, we opted to exclude papers published before 2017. This was decided to ensure that the included papers reported on interventions that represent current digital technologies. After removing duplicates and papers published before 2017, we had 463 documents. These documents were imported into the online review tool Covidence, which was used to manage the screening and data extraction processes.

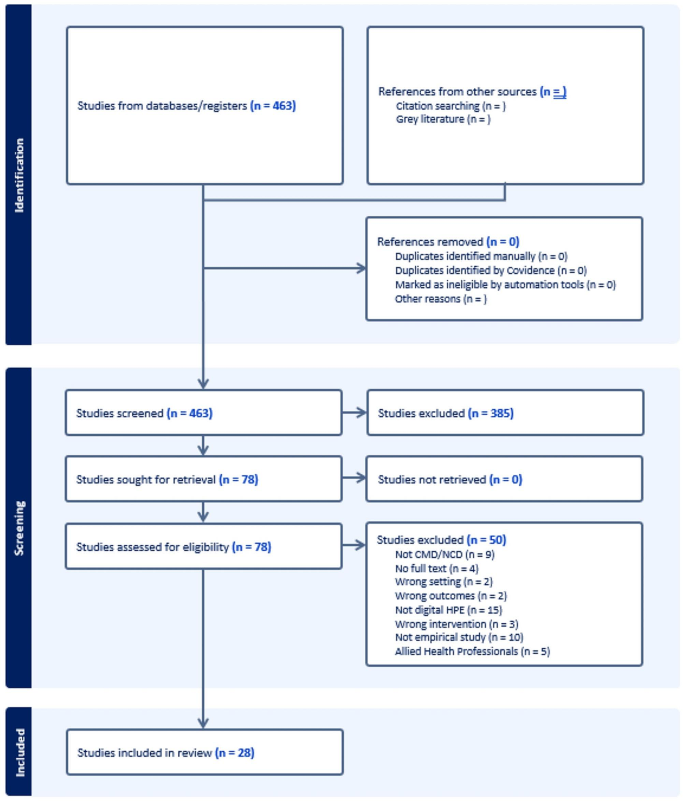

Figure 1 . PRISMA flow chart showing the screening process.

PRISMA flow chart showing the screening process

In Covidence, the first step was to screen the title and abstract of these 463 documents to determine whether they were suitable for inclusion in the review. This screening process excluded studies that were.

Not empirical (e.g., reviews and commentaries).

About training patients to manage their own chronic disease.

About digital health solutions (e-health, m-health, apps, etc.)

Not related to NCD prevention, treatment, or care.

This process led to the exclusion of 385 documents, leaving a pool of 78 for full-text screening. The full-text screening followed the same exclusion criteria. This led to the exclusion of a further 50 documents, leaving a pool of 28 documents for inclusion in the review. The PRISMA flow chart in Fig. 1 illustrates this process, and Table 1 presents an overview of the 28 included studies. We note quality assessments are not typically recommended or conducted with scoping reviews [ 19 ] Moreover, as we were primarily focused on understanding what kinds of evidence exist, we did not undertake a quality assessment of the included documents.

From each of these 28 papers, we extracted data about the study’s objectives, location, target population, research design and methodology, findings, health focus, and modality of the digital educational intervention. This extraction process was undertaken by one author (SH). A few unclear cases were discussed with a further two authors (AB, LXJ). In the results section below, we present a synthesis of the extracted data, with an emphasis on the benefits and challenges identified in the various digital educational interventions.

Description of studies

The final list of the 28 studies included in our review consisted of 22 studies from high-income countries with the majority of them from United States of America (USA). Only six studies were from LMICs, more specifically from Brazil, Pakistan, Türkiye, and Uganda, as well as two studies that spanned several LMICs.

The target groups were mostly in-service health professionals but a considerable number of studies also included pre-service students of medicine ( n = 6) and nursing ( n = 6). Among the targeted in-service health professionals, most were nurses ( n = 12), followed by doctors ( n = 8) and other health professionals ( n = 8) including emergency technicians, primary care providers, medical assistants, etc.

The majority of the studies in the overall pool used either experimental or observational study designs and gathered data using online questionnaires, interviews, and/or analysis of individual or online interactions between learners. The details about target groups and study designs are shown in Table 2 . We use the term experimental for studies that have no specific information on the randomization of the participants or where randomization has not been done. These studies typically included two groups of the study population, where one group served as an experimental one provided with the intervention and the other with no or some traditional type of intervention. Other than the observational and experimental studies, randomized control trials (RCTs) and evaluation studies were part of our review.

The studies in our review comprised mainly of educational interventions related to diabetes, stroke, hypertension and cardiac disorders.

Assessment of digital educational intervention

Based on the digital education modality that was described, we grouped the studies into three categories: blended learning, online learning with instructor, and online learning as self-study. In the sub-sections below we present the interventions, study findings, effectiveness and identified challenges of each modality.

Blended learning

Our review includes seven studies providing blended learning to health professionals and students. For this purpose, we identify blended learning as any intervention that combines online learning with some form of onsite training or teaching. All the studies report the advantages of blended learning over traditional learning and the increase in overall knowledge.

Blended learning was incorporated in various formats in the studies. Some of the studies include the online learning proponent prior to the onsite training [ 33 , 40 ]. In these, the online learning was provided in modules that could be taken at the participants’ own pace before the onsite programme which was characterised by hands-on workshops and lectures. Other studies began with on-site training followed by an online learning proponent [ 23 , 36 , 39 ]. In these studies, the online proponent consisted of further self-study of the content learned in the prior onsite training. The remaining two studies did not have a set order but rather had the online proponent as a learning resource that the participants could draw upon among other resources such as tele-education sessions, a local support coach [ 46 ] or interactive classroom lectures with group discussions and role play [ 43 ].

The studies consisted of both RCTs and observations. The RCT studies mostly highlighted the strengthening capacity of nursing professionals. For instance, in one RCT study in Thailand, the findings showed the effectiveness of blended learning in strengthening competency in diabetes care among nurses, wherein the levels of perceived self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, knowledge and skills in diabetes management care were statistically and significantly higher at Weeks 4 and 8 compared to the control group [ 39 ]. In another RCT conducted in Australia, the addition of access to online learning, as well as face-to-face education, significantly increased the uptake of diabetes education among hospital non-specialist nursing staff [ 40 ]. A study based in Pakistan gathered information about perceptions about social media as a tool for online training and reported that Facebook, with tutor support, enabled participants to study the material when their schedule permitted. The online teaching component and facilitation were ideal for their full-time working nurses, as reflected by their improved post-course test results [ 43 ]. The detailed findings for studies examining blended learning are provided in Table 3 .

Generally, among health professionals, the perception of blended learning was positive. Blended learning was perceived to be beneficial and impactful in increasing knowledge. This type of learning makes the learning interactive. However, certain challenges were identified that hampered online learning, e.g., limited internet connection and computer skills for the participants enrolled in the learning [ 43 ]. As many of the participants are health professionals active in the workforce, the long duration of the working hours makes it difficult to spare time for online learning [ 36 , 40 ].

Online learning with instructor

There were six studies in our review, wherein online learning with instructors was explored. Such online learning includes following a simultaneous schedule allowing for contact between learners and teachers/trainers during the course. Two of the six studies had no control group. All the studies assessed the effects of their online teaching through survey-based questionnaires. A majority of the studies reported that these types of courses are cost-effective and can help bypass the geographical barrier. The findings of these studies are given in Table 4 .

Regarding instructor involvement, five of the studies used learning platforms such as Moodle or Zuvia for the instructor to organise courses, materials and activities [ 22 , 27 , 38 , 42 , 45 ]. Four of these also had an online forum or messaging app for peer discussions about the content, two of these also included interactions with faculty and tutor support [ 27 , 38 , 42 , 45 ]. For instance, a study by Paul et al. [ 38 ] had an online request form for specialist advice regarding diabetes. The last study by Hicks and Murano [ 30 ] had an instructor-led webinar followed by self-study.

The studies showed a positive effect on practice. A Spanish study on cerebrovascular medical emergency management from reported that interprofessional online stroke training in the Catalonian Emergency Medical Service (EMS) was effective in increasing the study participants’ knowledge of cerebrovascular medical emergencies. The results encouraged the Catalonian EMS to maintain this training intervention in their continuous education program [ 27 ].

Online learning as self-study

Of the included papers, 15 were about online learning as self-study. In such an intervention, the learner undertakes an online course/training as flexible self-study. This means the course can be done at any time and does not require any set schedule or contact with teaching staff. Table 5 presents an overview of the study findings.

Largely the studies using online learning as self-study reported improvements in learning following the training. For instance, A study across Latin American countries studied the effects of online training on medical knowledge regarding acute kidney injury (AKI) on nephrologists and primary care physicians. The study reported gains in knowledge equivalent to 36%. It is important to note that the study concluded that the interactive, asynchronous, online courses were valuable and successful tools for continuing medical education in Latin America, reducing heterogeneity in access to training across countries. The application of distance education techniques has proved to be effective, not only in terms of primary learning objectives but also as a potential tool for the development of a sustainable structure for communication, exchange, and integration of physicians and allied professionals involved in the care of patients with AKI [ 34 ]. However, one study explored the use of online simulations [ 25 ]. This randomized control trial reported no significant change in the experimental group following an online educational course regarding oral anticoagulants in case of atrial fibrillation. Also, the reading material in certain modules being too dense and lengthy poses a challenge for the participants in one study to complete the learning [ 45 ]. Another study by Lombardi et al. [ 34 ]., also questioned whether the knowledge effect is retained on a long-term basis.

Some of the studies emphasise the possibilities that online learning provides. One study indicated that a 6-week internet-based course in diabetes and obesity treatment may serve as an important resource in postgraduate education for medical doctors as well as other health professionals. From a wider perspective, education based on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) may assist the professional community by providing the latest evidence-based guidelines in an easily accessible and globally available way [ 47 ]. An evaluation study in the United States reported that online learning modules can be developed and maintained with minimal costs and basic technological requirements and present a unique opportunity to provide essential information in a short timeframe. In addition, these modules can be specifically tailored to address identified knowledge gaps among various groups and can be easily disseminated and can be an effective method for educating nurses in a time- and cost-sensitive manner [ 41 ].

The major challenges faced by health professionals or students when participating in online learning by self-study include time constraints and out-of-date or inappropriate hardware and software [ 20 , 34 ]. Some barriers that online learning can help organisations overcome include logistical difficulties and expenses associated with maintaining an adequate pool of educators, coordinating training sessions, and standardizing training across sites [ 21 ].

This section discusses the strengths, weaknesses, and advantages of digital education related to NCDs in the reviewed literature in the context of India.

Value of online and blended NCD education

The limited literature available on the topic paints a positive picture regarding the increase in learning/knowledge of health professionals on NCDs due to online learning. A majority of the studies reported an increase in knowledge after the interventions. A study from Latin America provides an example of how online courses can be a valuable and successful tool for continuing medical education and reducing heterogeneity in access to training across countries. The diverse findings suggest that modality alone is not the sole issue; for example, a recent study comparing traditional vs. online learning [ 44 ] suggests interactivity may matter.

The studies reported a number of challenges related to the online format in general. One highlighted that training of healthcare providers can be more difficult in time constrained and low-resource settings due to limited accessible equipment, inadequate environment and competing interests [ 28 ]. Another found that augmented reality smartphone apps may not provide the extensive information needed for complex content [ 29 ]. The senior doctors were not as pleased as their less-experienced colleagues with the web-based format of the learning [ 35 ]. Online training options, while notionally attractive and accessible, are not likely to have high levels of uptake as they require more commitment, activity, and dedication [ 38 ]. Although there are challenges with online learning, the included studies also emphasized the opportunities it provides, e.g. making knowledge more accessible to a wider population and making it more flexible for health professionals with heavy workloads to learn at their own pace [ 36 , 39 , 47 ].