An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Glob Health

- v.6(6); 2021

Defining global health: findings from a systematic review and thematic analysis of the literature

Melissa salm.

1 Anthropology, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

2 University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

Mairead Minihane

Patricia conrad.

3 VM:PMI, University of California Davis, Davis, California, USA

Associated Data

No data are available. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. n/a.

Introduction

Debate around a common definition of global health has seen extensive scholarly interest within the last two decades; however, consensus around a precise definition remains elusive. The objective of this study was to systematically review definitions of global health in the literature and offer grounded theoretical insights into what might be seen as relevant for establishing a common definition of global health.

A systematic review was conducted with qualitative synthesis of findings using peer-reviewed literature from key databases. Publications were identified by the keywords of ‘global health’ and ‘define’ or ‘definition’ or ‘defining’. Coding methods were used for qualitative analysis to identify recurring themes in definitions of global health published between 2009 and 2019.

The search resulted in 1363 publications, of which 78 were included. Qualitative analysis of the data generated four theoretical categories and associated subthemes delineating key aspects of global health. These included: (1) global health is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and pursued at research institutions; (2) global health is an ethically oriented initiative that is guided by justice principles; (3) global health is a mode of governance that yields influence through problem identification, political decision-making, as well as the allocation and exchange of resources across borders and (4) global health is a vague yet versatile concept with multiple meanings, historical antecedents and an emergent future.

Extant definitions of global health can be categorised thematically to designate areas of importance for stakeholders and to organise future debates on its definition. Future contributions to this debate may consider shifting from questioning the abstract ‘what’ of global health towards more pragmatic and reflexive questions about ‘who’ defines global health and towards what ends.

Key questions

What is already known.

- Debate around a common definition of global health has seen extensive scholarly interest within the last two decades; despite the abundance of literature, ambiguity still persists around its precise definition.

- No systematic reviews with thematic analysis have been conducted to explore extant definitions of global health nor to contribute to a comprehensive definition of global health.

What are the new findings?

- We compile and thematically analyse extant definitions of global health and propose grounded theoretical insights into what might be seen as relevant for establishing a common definition of global health moving forward.

- The need for a clear and concise definition of global health has the highest stakes in the domain of global health policy governance.

What do the new findings imply?

- Stakeholders tend to define the ‘what’ of global health: its spaces, objects and practices. Our findings suggest that the debate around definition should shift to more pragmatic and reflexive questions regarding ‘who’ defines global health and towards what ends.

Debate around a common definition of global health (GH) has seen extensive scholarly interest within the last two decades. In 2009, a widely circulated paper by Koplan and colleagues aimed to establish ‘a common definition of global health’ as distinct from its derivations in public health (PH) and international health (IH). 1 They rooted the definition of PH in the mid-19th century social reform movements of Europe and the USA, the growth of biological and medical knowledge, and the discipline’s emphasis on population-level health management. Similarly, they traced the evolution of IH back to its colonial roots in hygiene and tropical medicine (TM) through to the mid-20th century with its geographic focus on developing countries. GH, they argued, would require a distinctive definition of its own to be ‘more than a rephrasing of a common definition of PH or a politically correct updating of international health’. Their intervention built on prior research noting confusion and overlap among the three terms and thus a need to carefully articulate the important differences between them. 2–5 Additional stakeholders have since elaborated varied definitions of GH, yet consensus around its precise definition remains elusive.

To determine how GH is presently defined and to identify whether a common conceptualisation has been established, we conducted a qualitative systematic literature review (SLR) of the GH literature between 2009 and 2019. SLRs are a methodology used ‘to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question’. 6 Unlike unsystematic narrative reviews, SLRs use formal, repeatable and transparent, procedures for identifying, evaluating and interpreting available research, thus ensuring robust coverage of the current literature while reducing the biased presentation of available evidence. 7–9 Medical researchers and policy-makers have long relied on SLRs because they integrate and critically evaluate current knowledge to support decisions about important issues. 10 However, very few SLRs exploring aspects of GH have yet been published, 11–13 and no SLRs focusing on extant definitions of GH have been conducted. This paper fills that gap by exploring the thematic components of extant definitions and thereby contributes towards a comprehensive definition of GH.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this review is: (a) to examine how GH has been defined in the literature between 2009 and 2019, (b) to systematically analyse the core thematic categories undergirding extant definitions of GH and (c) to offer grounded theoretical insights into what might be seen as relevant for establishing a common definition of GH.

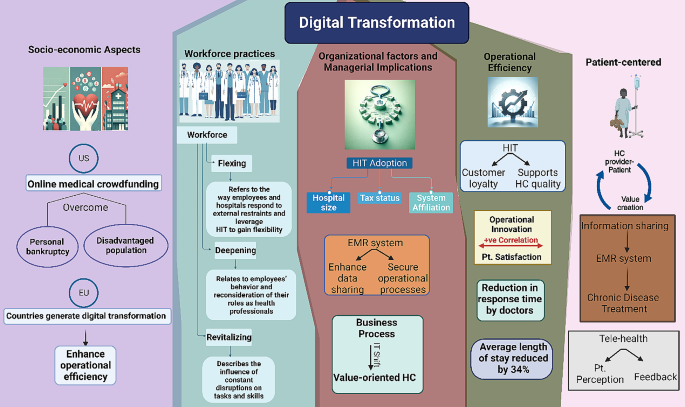

Aiming to capture definitions of GH in literature between 2009 and 2019, our team conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines ( figure 1 ). 14 The sequential steps of our review process included the following.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of citation analysis and systematic literature review. 14

Search strategy: identify papers and relevant databases

Search technique.

The terms ‘global health’ AND ‘define’ OR ‘definition’ OR ‘defining’ were queried when they appeared in the title, abstract or keyword of studies. Published studies were identified through comprehensive searches of electronic databases accessible through the authors’ university library system (Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, PubMed, EBSCO). Citation tracking through Google Scholar was also completed.

Study selection criteria

Articles published in international peer-reviewed journals, including conference papers, book chapters and editorial material, were reviewed. The studies included were written in English and published between 2009 and 2019. The year 2009 was chosen as a starting point because this is the year in which Koplan et al published ‘Towards a Common Definition of Global Health’. For this review, the team excluded news articles, theses, book reviews and published papers that were not written in English.

Assessment strategy: appraise which papers to include in review

The protocol-driven search strategy required that articles included in the review must: (a) contain the keywords ‘global health’ and ‘definition’ and/or ‘define’; (b) be in the English language and (c) be published between 2009 and 2019. The number of articles containing these keywords was recorded, and all the titles uncovered in the search were imported into Mendeley, a software for managing citations. Duplicates were identified and removed, after which abstracts were screened to assess eligibility against the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles were retrieved for those that met the inclusion criteria and three team members read a designated number of the articles selected for full review. To be included in the data extraction sheet, each article needed to: (a) focus on and explicitly name GH, (b) offer an original definition or description of GH and/or (c) cite an already-existing definition of GH. Articles that mentioned the query terms without any relation to these requirements (eg, did not provide a definition of GH or descriptive data to support interpretations of a GH definition) were excluded. Assessment for relevance and content was conducted by two investigators who reviewed all identified articles independently. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third investigator.

Synthesis strategy: extract the data

Based on the research goals, the team designed an initial coding template in Google Sheets as a method of documentation, with the following coding variables: author, title, typology, definition(s), conclusions and conceptual dimensions. To achieve a high level of reliability, the review team open-coded the same five articles, compared their coding experiences, and reconciled differences before adopting a final coding template and evenly dividing the remaining articles to be analysed. Extracted data included the type of study or research paradigm of each publication, the location and disciplinary affiliation of each study based on the contact information of the corresponding author, definitions and descriptions of GH and specialised dimensions of GH. Whenever articles contained more than one definition or description of GH, those items were organised line-by-line under the author on the data extraction sheet.

Analysis strategy: analyse the data

The team conducted thematic analysis of the data to understand how GH has been defined since 2009. Our approach to thematic analysis was based on the guidelines described by Thomas and Harden 15 and further informed by principles in grounded theory. 16 Our strategy consisted of three main stages: Initial Coding—remaining open to all possible emergent themes indicated by readings of the data; 16 17 Focused Coding—categorising the data inductively based on thematic similarity at the level of description 17 and finally, Theoretical Coding—integrating thematic categories into core theoretical constructs at a higher level of analysis. 18

In the first cycle, open descriptive codes were generated (eg, differences between PH and IH, GH education requirements, social justice values) directly from the definitions and descriptions of GH found in the articles. Individual sentences defining or describing GH were treated as unique line items on the data extraction sheet and coded accordingly in order to generate a range of ideas and information on which to build.

In the second cycle, a focused thematic analysis was carried out to identify general relationships and patterns among definitions in the literature and to confirm significant links between the openly coded data. Thematic phrases (eg, GH is multidisciplinary, GH promotes equity) were developed and reapplied to coded definitions on the data extraction sheet. Team members wrote and attached analytic memos to each coded datum—reflecting on emergent patterns and further ‘codeweaving’, 18 which is a term for charting possible relationships among the coded data. At this stage, additional coding techniques were utilised. Attribute coding was applied as a management technique for logging information about the characteristics of each publication. 19 Data segments coded in this manner were extracted from the main data extraction form and reassembled together in a separate Google Sheet for further analysis. The team also coded extracted definitions of GH by type: (a) original definition, (b) cited definition, (c) original description to track possible relationships between citational practices and developments in the conceptualisation and definition of GH.

In the third cycle, thematic phrases were ordered according to frequency then commonality and abstracted for overriding significance into theoretical categories. At this stage, the conceptual level of analysis was raised from description to a more abstract, theoretical level leading to a grounded theory. This resulted in the construction of four thematic categories, which are presented below with their supporting subthemes.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not directly involved in this review; we used publicly available data for the analysis.

The search strategy retrieved bibliographic records for 1363 papers. The assessment strategy resulted in the elimination of 1237 papers after the removal of duplicates. Consequently, 78 papers were subjected to our strategies of synthesis (data extraction) and analysis.

Characteristics of study

A variety of studies were included in this review. The majority (27) were commentaries, viewpoints or debates. 1 20–48 Twenty-four were grouped as review/overview articles. 45–68 There were 25 original research articles, of which 13 used qualitative methods, 69–81 11 used mixed-methods 82–92 and one 93 used quantitative data from a survey to proffer definitions of GH. Two studies included in the review were book chapters. 94 95

The typologic, geographic and disciplinary distribution of the studies in this review are shown in table 1 . Most studies were authored in North America (40), 1 20–31 39–41 43 46 47 50 54–58 61 63 66 68 70 73 74 76–80 83 84 86 87 89–91 94 followed by European countries (29), 22 26 28 32 34–38 42 44 45 48 51 52 59 62 64 65 67 71 75 82 85 88 92 93 95 96 countries in Asia (2), 33 72 Latin America and the Caribbean (2), 60 81 and New Zealand (1). 20 Disciplinary fields represented in our sample included health (56), 20 22–27 30–32 34–40 42 43 45–51 54–56 58–61 63–69 72 74 75 77–79 82–84 86 88–91 93 95 law, social and cultural professions (19), 1 20 28 29 33 41 44 52 53 57 62 70 71 73 76 80 81 87 92 94 and education (2). 20 31

Summary of characteristics of retrieved publications

Attributes of definitions

All 78 studies under review defined, described and/or cited extant definitions of GH. The 34 papers shown in table 2 included descriptive definitions of GH that were formulated distinctly by its authors, that is, they were presented as original and without direct reference to other definitions.

How global health has been defined by academics since 2009

Several scholars engaged directly with the Koplan et al definition of GH 1 to stipulate definitions of their own. For example, some authors proposed amendments to Koplan et al that would place greater emphasis on inequity reduction and the need for collaboration, 20 particularly with institutional partners from developing countries. 73 Others were more critical of the broad yet weak conceptual idealism 86 of Koplan et al and recommended detaching normative objectives from its definition, 26 such as the value-laden concept of equity, which could compromise the definition’s technical neutrality by rendering it ideological. 91 Other authors sought to analytically clarify the meaning of ‘the global’ 26 in the definition provided by Koplan et al , distinguish it more clearly from IH 78 or dispute their distinction between GH and PH. 27 Indeed, the impact of the definition of GH proposed by Koplan et al has been substantial. It was variously adopted by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health, 47 the Canadian government, 23 Global Health for Family Medicine, 89 the German Academy of Sciences 75 and the Chinese Consortium of Universities for Global Health. 77

In general, GH was defined as a term, 37 51 95 and in particular, an umbrella term 49 75 or a concept; 69 and more broadly as a zone 76 or field 32 48 91 94 or area of research and practice, 1 56 as an achievable goal, 50 an approach, 48 82 a set of principles, 45 83 an organising framework for thinking and action 96 or a collection of problems. 35 94 GH was frequently contrasted to IH 32 35 68 69 94 95 and PH, 20 21 31 32 35 or else seen as indistinguishably from PH and IH. 27 Additionally, several papers explicitly specified and subsequently defined certain dimensions of GH, such as ‘global health governance’ (GHG), 32 33 35 38 42 51 52 58 69 80 81 87 ‘global health diplomacy’ (GHD), 24 28 95 ‘global health education’, 36 39 46–49 59 70 74 75 77 78 82 89 93 ‘global health security’, 26 41 76 88 92 97 98 ‘global health network’, 41 81 ‘global health actor’, 52 ‘global health ethics’, 69 ‘global health academics’ 64 67 and ‘global health social justice’ 61 (see table 3 ).

Frequently defined facets of ‘Global Health’ with exemplary definitions

Grounded theory approach based on thematic analysis

Definitions and descriptions of GH were aggregated into nine thematic codes reflecting the contents and scope of GH definitions, the functionality of those definitions and/or perceptions about defining GH. Codes were: (1) GH is a domain of research, healthcare and education, (2) GH is multifaceted (disciplinary, sectoral, cultural, national), (3) GH is rooted in a commitment to equity, (4) GH is a political field comprising power relations, (5) GH is problem-oriented, (6) GH transcends national borders, (7) GH is determined by globalisation and international interdependence, (8) conceptually, GH is either similar or dissimilar to PH, IH and TM and (9) GH is perceived as definitionally vague.

These codes were grouped selectively into higher analytical categories or theoretical statements as grounded in the literature: (1) GH is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement and form of expertise taught and researched through academic institutions, (2) GH is an ethos (ethical orientation and appeal) that is guided by justice principles, (3) GH is a mode of governance that yields degrees of national, international, transnational and supranational influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders, (4) GH is a polysemous concept with many meanings and historical antecedents, and which has an emergent future ( table 4 ).

Defining global health with grounded theory analysis—table of themes, code categories and quotes from text

IH, international health; PH, public health; TM, tropical medicine.

Theme: global health is a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and pursued through research institutions

Subtheme: gh is a domain of research, healthcare, education.

GH was repeatedly defined as an active field of knowledge production that is composed of the following key elements: research, education, training and practice related to health improvement. 1 20 21 23 32 33 35 38 40 44–49 52 55–58 61 63–69 72 74 75 77 78 80 82 90–92 94 Few authors defined GH as a new, independent discipline within the broader domain of medical knowledge, 17 33 38 46 63 74 80 82 90 and some outlined discipline-specific competencies that were considered integral to the definition of GH, at least in curriculum development; for example: clinical literacy, 80 medical humanities, 82 cross-cultural sensitivity, 33 38 46 59 63 80 90 experiential learning 47 and critical thinking skills. 72 82 Several authors defined GH as a diffuse arena of scholarship that spans an array of academic disciplines, including anthropology, engineering, law, agriculture and healthcare administration. 44 56 59 63–65 78 91 94 Others defined GH explicitly as a ‘transdiscipline’ that seeks to transcend the restricted gaze of any single discipline and consequently integrate knowledge from a variety of sources. 67 94 Several authors explicitly defined GH as a necessarily collaborative field. 1 20 22 24 36 43 45 47 57 61 63 68 77 78 80 91

Subtheme: GH is multifaceted (disciplinary, sectoral, cultural, national)

The prefix ‘multi-’ was consistently applied in definitions of GH to describe a perspective that focuses on the multitude of interrelated factors, dimensions, values and features that underpin health as well as efforts to improve and study it. There was broad agreement that multidisciplinarity is a defining characteristic of GH. 1 23 25 32–34 36 38 40 45–47 49 52 55–57 59 60 64–69 72 75 77 78 80 82 91 However, there was some debate whether multiple disciplines are always needed and beneficial—and therefore essential—to the definition of GH. 23 One author argued that the multidisciplinary nature of GH is precisely what differentiates it from PH and IH. 68 Although some claimed that GH, with its focus on social and economic determinants, is inherently ‘predisposed to include aspects of the liberal arts and social sciences’, 75 others critically observed that most GH educational opportunities still cater predominantly to medical students, 32 35 48 72 which suggests that greater efforts will be required to achieve multidisciplinarity in the field moving forward.

There was a correspondence between GH definitions citing multidisciplinarity and cultural competency. 32 33 38 48 49 56 78 82 90 Curiously, multisectorality was less frequently mentioned than multidisciplinarity in definitions of GH, though it was referenced in some papers. 20 22 43 52 66 83 86 95

Theme: global health is an ethical initiative that is guided by justice principles

Subtheme: gh is rooted in values of equity and social justice.

Equity and social justice were the two most commonly and explicitly referenced values undergirding GH definitions and goals. Equity was repeatedly framed as a ‘main objective’ 60 and core component of GH research and practice. 23 25 43 46 48 53 66 67 77 78 84 However, it remains unclear whether the authors in our sample share the same meaning of equity. Velji and Bryant defined equity broadly as ‘ensuring equal opportunities and resources to enable all people to achieve their fullest health potential’. 66 Meanwhile, others rooted their conceptualisation of equity more specifically in the principles of social justice 30 61 69 88 89 or the human rights concept of equality, 54 62 67 83 86 which asserts that ‘all people are equal in regard to dignity and rights, regardless of their origin and all biological, social or other specific differences’. 59 This postwar sensibility echoes the 1978 Alma Ata Declaration of ‘health for all’, 20 24 as well as a traditional humanitarian ideal, even if now associated with principles grounded in national and global security. 24 54 88

Occasionally, the terms ‘equity’ and ‘equality’ were used interchangeably, suggesting they possess a commonly shared valence and reciprocal relationship despite slight differences in signification. Whereas equity refers to the provision of resources and opportunity based on specific needs, equality connotes providing the same level of resources and opportunities for all. 86 Nevertheless, other scholars questioned whether equity or equality should be included in official definitions of GH, at all, 27 48 75 insofar as what counts as ‘equitable’ for one country may be different for another. 26 32 48

Theme: global health is a form of governance that yields national, international, transnational and supranational influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders

Subtheme: gh is a political field comprising power relations at multiple scales.

Numerous papers defined GH as embedded within a political field comprising power relations at multiple scales. 20 22–24 26 28 29 31–33 35 41 42 45 48 51–54 56 58 60 63 66 70 72 76 79 87 95 ‘Political field’ refers here to a sphere of influence and jurisdiction wherein institutions determine governing modalities (eg, laws, policies, instruments) to assure a range of activities, such as determining priorities, coordinating stakeholders, regulating funding mechanisms, establishing accountability, allocating resources and providing access to health services for the general public. ‘Power relations’ refers to the capacity of institutions, individuals, instruments and ideas to affect the actions of others; and ‘at multiple scales’ refers to levels of analysis (ie, worldwide, regional, national, local, etc.).

Within the literature on GHG and GH security, authors argued the need for a universal definition of GH to shape policy frameworks that ensure compliance with IH law. 32 45 51 88 95 Here, it is important to note that the ability to shape GH policy is, itself, an exercise in power: some GH actors, defined as ‘individuals or organizations that operate transnationally with a primary intent to improve health’, 56 are more capacitated than others to impact the formulation of policies and amount of attention and resources that certain GH issues receive. 32 41 45 52 95 For example, several papers discussed how ‘GH actors’ like the World Bank and the WHO shaped discussions around the response to Ebola, leading to refined definitions of GHG 35 87 88 and GH security. 41 Similarly, definitions of GH in line with the 2015 United Nations Millennium Development Goals, were also commonly referenced, 25 35 45 51 reflecting the influence of certain GH actors on the conceptualisation of GH.

Subtheme: GH is determined by globalisation and international interdependence

Numerous authors linked interdependence and accelerating globalisation (the process of integrating governments and markets, and of connecting people worldwide) with the need for a cohesive definition of GH, particularly to address issues of governance. 24 32 35 45 68 88 GHG and GHD were outlined as two influential subdomains in which the interconnections between globalisation, foreign policy and international relations were viewed as indispensable to definitions of GH. Two articles quoted David P Fidler’s definition of GHG as ‘the use of formal and informal institutions, rules, and processes by states, intergovernmental organizations, and nonstate actors to deal with challenges to health that require cross-border collective action to address effectively’. 35 58 Elsewhere, GHD was described as ‘bringing together the disciplines of public health, international affairs, management, law and economics and focuses on negotiations that shape and manage the global policy environment for health’. 95

Subtheme: GH issues transcend national borders

Across several papers, we observed a common refrain that GH ‘crosses borders’ and ‘transcends national boundaries’. 1 20 23 42 45 52 60 67 68 74 Authors frequently described GH concerns as those exceeding the jurisdictional reaches of any individual nation-state alone. 34 42 45 51 52 54 77 95 One paper claimed that GH is ‘transnational by definition’, 74 and others characterised GH problems as those experienced transnationally. 20 32 48 50 68

Studies focusing on GH research and training frequently referenced specific diseases and health risks that ‘transcend national borders’ alongside parallel recommendations to include an international component in the development of GH curricula. 16 48 49 63 74 93 While crossing national borders to research and promote health for all is widely perceived as an historical condition for GH 24 that has led to GH’s emergence as an academic discipline, 63 several scholars argued that GH should also focus on domestic health disparities 1 27 38 46 and for local issues to be simultaneously understood as universal or worldwide 48 74 75 to the extent they may occur anywhere 22 and are almost always impacted by global phenomena. 56

Subtheme: GH is problem-oriented

Medical anthropologists, Arthur Kleinman and Paul Farmer, described GH as a collection of problems rather than a distinct discipline. 35 94 Several authors in our review delineated GH problems through identification of specific diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, TB, Zika and Ebola. 24 29 30 35 45 83 Lee and Brumme noted that it has become common for experts to define GH problems by identifying their objects, namely diseases, population groups and locations. 58 Indeed, some authors outlined GH problems as the set of challenges ‘among those most neglected in developing countries’, 86 among them: emerging infectious diseases and maternal and child health; 43 65 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other noncommunicable diseases in ‘local’ communities 25 63 and even neurological disorders among refugees arriving in Europe. 93 How these types of object-based definitions of GH problems come to shape GH agendum is important to note.

Clark made a compelling argument against the definition of GH problems in terms of specific diseases, writing that such ‘medicalisation’ may ‘prove detrimental for how the world responds and resources actions designed to alleviate poor health and poverty, redress inequities, and save lives’. 72 Brada also argued against defining GH problems geographically and instead urged experts to consider how the processes by which GH and its quintessential spaces, namely ‘resource-limited’ and ‘resource-poor settings’, are actively constituted, reinforced and contested. 70 Several authors similarly suggested that focusing on the social, political, economic and cultural forces contributing to health inequity and diseases of poverty better captured the scope of GH problems than naming any particular set of diseases or places in the world. 33 43 56 58 69 72 73 86 92

Lack of consensus regarding what counts as a ‘true’ GH problem was linked to the lack of a clear and concise definition of GH. Indeed, several scholars argued that the current inability to define GH made it difficult for stakeholders to define precisely what the ‘problem’ is. 44 45 48 86 Furthermore, the diagnosis of GH problems determined what types of GH ‘solutions’ were proposed in response. For example, when GH problems were defined as universally shared and transnational, then cross-border solutions were developed; when GH issues were framed epidemiologically in terms of distributed risk, then actions targeting specific determinants and burdens were proposed. 1 20 23 67 68 92 When GH problems were framed as threats to inter/national security, strategies were formulated to protect borders, economies, health systems and to improve surveillance mechanisms. 41 45 54 76 80 88 When the problem of inequality drove definitions of GH, recommendations to alleviate poverty, food insecurity, poor sanitation, etc. were proposed. 32 53 60 72

Although Kuhlmann suggested that GH tends to over-prioritise problem-identification to the detriment of critical solution-oriented work, 31 our analysis suggests that the type, scope and quality of solutions proposed are contingent on the elaboration of problems. Similarly, Campbell wrote, ‘Unlike a science or an art, the field of global health is very much about providing solutions to current problems. As such, it would be short-sighted not to consider the causes of global health problems in order to better formulate the solutions. The causes ought to be included in a comprehensive and complete definition of the field’. 23

Theme: global health is a polysemous concept with historical antecedents and an emergent future

Subtheme: gh is conceptually dis/similar to ph, ih and tm.

GH was consistently traced back to and compared with PH, IH and TM. 1 20 27 32–34 43 57 69 71 75 84 86 88 Disagreement or confusion regarding the degrees of similarity and difference between these domains seemed to stem from a shared understanding that GH, in fact, evolved to a varying degree from each of these fields and does not, therefore, denote a clear-cut break with nor full-blown departure from any of them. 84 94

Several authors argued that the scope and scale of GH is distinct from PH. 1 20 32 69 71 Some argued that ‘public health is equated primarily with population-wide interventions; global health is concerned with all strategies for health improvement,’ including clinical care; 20 and that ‘public health acknowledges the state as a dominant actor, (while) global health recognizes the rise of other actors like international institutions’. 35 GH was also seen as placing a greater emphasis on multidisciplinarity and promoting a more expansive conceptualisation of ‘health’, itself, compared with PH. 69 Beyond the prevention of and response to biomedicalised health risks at the population level, Rowson defined GH as oriented towards the ‘underlying determinants of those problems, which are social, political and economic in nature.’ 32 It is questionable, however, to assume similar notions of health have not also been pursued in PH. Meanwhile, opposing views found GH and PH conceptually indistinguishable, 27 43 86 either as terms that could be used interchangeably, 95 or else as coconstitutive of one another, such that PH could be understood as a descriptive component of GH. 33 86

Differences between GH and IH echoed those drawn between GH and PH. For example, GH was characterised as more attentive to multidisciplinarity, while IH was said to implement a more limited biomedical approach to healthcare and health research. 1 69 95 Undergirding a major point of distinction between GH and IH was the belief that IH focuses on health problems in developing countries 1 22 32 43 45 48 54 83 86 93 and relies on ‘the flow of resources and knowledge from the developed to the developing world’, 32 whereas GH either is, or should be, more bidirectional. 1 45 84 In other cases, GH was described as comparable to IH, for example, when countries link GH efforts with development aid. 86 This is because the emphasis on delivering aid to poor countries reinforces an image of the world’s poor as needy subjects and, therefore, marks a continuation of IH and its sentiments under the guise of GH. 35

Finally, the field of TM was referenced to describe the evolutionary track of GH, particularly that GH is a modern-day product of the former. 20 25 57 69 75 84 A few authors critically pointed out that although GH has generally replaced TM and IH as terms embedded in histories of colonial power relations, many of the contemporary structures for governing and/or facilitating GH between countries today have remained largely the same, 25 48 54 62 suggesting that distinguishability between these terms too often occurs at the level of semantics.

Subtheme: GH is still vaguely defined

While GH was often described as a popular and well-established term, another key attribute repeated across the literature was its enduring vagueness. 23 25 26 31 33 43 45 48 52 62 74–77 81 86 Indeed, most papers commented on the term’s defiance of easy definition, its ambiguity and the lack of clarity regarding how people and organisations engaged in GH are using (or not using) the term to describe their interests. For example, Beaglehole and Bonita pointed out that research centres in low-income and middle-income countries are often engaged in GH issues but under other labels. 20 Some authors viewed the present lack of a clear and common definition as an obstacle endangering the coherence and maturation of the field. 33 35 45 For others, this indistinctness was thought to be precisely what gives GH such wide applicability, a certain degree of currency and political expediency. 45 76 81 86

A major concern cited was the lack of guidance for defining the term ‘global’ in GH. 26 34 43 48 75 As Bozorgmehr has outlined, the term is often used interchangeably within the GH community to mean ‘worldwide’, ‘everywhere’, ‘holistic’ and/or ‘issues that transcend national boundaries’. 48 This trend was noticeable within our review, as well. Engebretsen emphasised that GH ‘does not only allude to supranational dependency within the health field, but refers to a norm or vision for health with global ambitions’. 26 This view suggests that because the planet is populated by a multiplicity of positionings, perspectives and diverse world views, there can never be a truly a universal definition of ‘the global’ nor a global consensus around the definition of GH.

Finally, among studies that conducted original research into the definition of GH, several reported that study participants could not reach consensus on a definition. 52 74 75 77 Many thought it would be difficult if not impossible to arrive at a single, unified theoretical definition of GH, yet considered it important to formulate an operational definition of GH for guiding emerging activities related to GH. 23 45 77

This is the first study to systematically synthesise the literature defining GH and analyse the definitions found therein. All of the articles included in this study were published in peer-reviewed journals since 2009 indicating recent and steadfast interest in the topic of GH’s definition. This review examined GH definitions in the literature, and our thematic analysis focused on identifying recurrent themes across different definitions of GH.

Of the 78 articles included in this study, approximately one-third utilised empirical research methodologies to posit definitions of GH or else directly contribute towards the establishment of a common definition. Another one-third of papers summarised and discussed previously published definitions of GH (eg, reviews/overviews), while the remaining one-third suggested definitions of GH that were less grounded in analysis of empirical data than in the perspectives of its authors (eg, editorials, viewpoints). This systematic analysis indicated that the question of GH’s precise definition marks a point of controversy across fields of expertise. The variety of GH definitions posited by diverse experts in search of a common definition indicate that GH is multifaceted and polysemous.

In its broadest sense, GH can be defined as an area of research and practice committed to the application of overtly multidisciplinary, multisectoral and culturally sensitive approaches for reducing health disparities that transcend national borders. Indeed, it was most commonly defined across the literature in such general terms.

More specific definitions of GH were, of course, proposed by and considered valuable for many stakeholders in our review. Our analysis indicates that the precise definitions proposed by different experts were devised to serve particular functions. For example, narrow and concise definitions of GH were most frequently sought in the domains of governance and education, primarily for steering the development of policy frameworks and curricula, respectively. The imperative for an exact definition of GH in these subfields may be linked to bureaucratic demands for demarcating a technical term under which to classify specific activities, standardise certain functions, administer funds and direct workflow accordingly. It is also in this domain that authors most vociferously decried the absence of a unified and concise definition of GH, arguing this lack has led to ineffective initiatives, elusive methods for establishing accountability and instances of resource allocation based on ad hoc criteria—attractiveness to donors, public opinion, development agendum, foreign, economic or security policy priorities and so on—rather than via transparent mechanisms for adjudicating health need. 28 54 58 65 83 In contexts where health needs and upstream challenges were articulated, the lack of an agreed-upon definition oft impeded the policy process because stakeholders could not discern which GH issues among the multitude of different problems labelled as important were, in fact, the most pressing. 24 45 52 Because political indecision ramifies disproportionately for publics in countries where reliance on GH aid is a matter of life and death, establishing a clear definition of GH seems most crucial for the domain of governance.

We also found that detailed descriptions of GH’s specific conceptual and functional dimensions tended to reflect the specialisations or discipline-specific priorities of their authors. For example, definitions of GH stipulating the primacy of ‘cultural competency’ and ‘multidisciplinarity’ were more commonly proposed by interdisciplinary professionals in the literature on GH education than in journals of health policy, where definitions of GH were oriented more toward ‘security’ and ‘governance’ concerns. This suggests a correspondence between the subjective, experiential positions of the definers and the vocabulary they used to define or frame the need to define GH.

Unsurprisingly, we found that health professionals proposed the majority of definitions of GH in the literature. Additionally, the majority of publications and their authors were from higher income countries. Several authors in our review critically observed that GH has become institutionalised at a faster rate in higher income countries compared with lower and middle-income countries. 20 48 63 72 77 82 Their observations combined with our findings suggest that extant definitions of GH published in the literature or otherwise circulating in academic and professionalised spaces may unevenly reflect the interests and priorities of stakeholders from higher income countries. This suggests a need for greater diversity and inclusion in the debate on GH’s definition, as well as further reflexivity regarding who is defining GH, their means and motivations for doing so, and what these definitions put into action.

Interestingly, several articles published since 2019 have extended the debate on this topic of GH’s definition by directly engaging questions of geography and positionality: a recent commentary by King and Kolski defining GH ‘as public health somewhere else’ was met with pushback by those who argue that spatial definitions of GH are limited and limiting. 99–102

Limitations

To determine how GH is defined by experts in the literature, we ensured that the selection criteria developed for this study were broad enough to include a wide range of perspectives. Therefore, we included articles with varying degrees of evidentiary support, such as viewpoints, commentaries and editorials. Consequently, the results may be influenced by some of the primary researchers’ assumptions, projections, and biases. Backward citation tracking was used to add relevant articles to the review that had not been initially identified through database searching. This ensured that the review was exhaustive, however it also means that some conclusions drawn in the thematic analysis may have been influenced by this manual search strategy. By applying qualitative methods, this review provided a robust analysis of the thematic categories undergirding extant definitions of GH. A major limitation of this form of analysis is the extensive time required to develop and establish a code book and standardise the three coders’ use of the code book. However, this was deemed necessary to ensure consistency of judgement and intercoder reliability at each stage in the analysis. Another limitation of this study is that only articles written in English were included. To enhance the generalisability of results, future reviews should include data from non-English articles, especially if an inclusive, common definition of GH is to be achieved. Finally, this review was finalised prior to the emergence of the novel coronavirus. As such, future research should take into account new definitions of GH that emerge in light of the pandemic and lessons learnt.

Between 2009 and 2019, GH was most commonly defined in the literature in broad and general terms: as an area of research and practice committed to the application of multidisciplinary, multisectoral and culturally sensitive approaches for reducing health disparities that transcend national borders. More precise definitions exist to serve particular functions and tend to reflect the priorities of its definers. The four key themes that emerged from the present analysis are that GH is: (1) a multiplex approach to worldwide health improvement taught and researched through academic institutions; (2) an ethos that is guided by justice principles; (3) a mode of governance that yields influence through political decision-making, problem identification, the allocation and exchange of resources across borders and (4) a polysemous concept with historical antecedents and an emergent future. Findings from this thematic analysis have the potential to organise future conversations about which definition of GH is most common and/or most useful. Future discussions on the topic might shift from questioning the abstract ‘what’ of GH to more pragmatic and reflexive questions about ‘who’ defines GH and towards what ends.

Acknowledgments

Helpful comments by anonymous reviewers are acknowledged with thanks.

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: MS initiated and designed the project. MS, MA and MM contributed to the implementation of the research, to the collection of data, analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. PC supervised the project and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Global Health Care, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 917

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Global health care is a challenging phenomenon that supports the development of new perspectives and approaches to solving global health concerns, including nutrition, infectious disease, cancer, and chronic illness. It is important to address global health as a driving force in international healthcare expenditures because it represents an opportunity for clinicians throughout the world to collaborate and to address global health concerns to achieve favorable outcomes. Global healthcare in the modern era includes the utilization of technology to support different population groups and to address different challenges as related to global health problems that impact millions of people in different ways. These challenges demonstrate the importance of large-scale efforts to eradicate disease, to prevent illness, and to manage disease effectively through comprehensive strategies that encourage communication and collaboration across boundaries.

Global health care incorporates a number of critical factors into play so that people throughout the world are given a chance to live and to lead a higher quality of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) is of particular relevance because this organization supports global health initiatives and large-scale impact projects throughout the world (Sundewall et.al, 2009). The WHO recognizes the importance of developing strategies to address global health concerns by pooling resources in order to ensure that many population groups are positively impacted by these initiatives (Sundewall et.al, 2009). The WHO also collaborates with government bodies throughout the world to address specific concerns that are relevant to different population groups, such as infectious diseases, many of which ravage populations in a significant manner (Fineberg and Hunter, 2013). In this context, it is observed that global health has a significant impact on populations and their ability to thrive, given the high mortality rates of some diseases in less developed nations (Fineberg and Hunter, 2013). Therefore, it is expected that there will be additional frameworks in place to accommodate the needs of populations and the resources that are required to achieve favorable outcomes (Fineberg and Hunter, 2013).

In addition to the WHO, there are many other international organizations that support global health and disease in different ways. For example, The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) supports large-scale global health efforts to support the world’s children (imva.org, 2013). UNICEF works in conjunction with many governments and other sources of funding in order to accomplish its objectives related to child health and wellbeing (imva.org, 2013). UNICEF spends significant funds on many focus areas, including the preservation of child health, nutrition, emergency support, and sanitation in conjunction with local water supplies (imva.org, 2013). In addition, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) provides support in many areas, including a primary focus on healthcare in developing nations (imva.org, 2013).

Leininger’s Culture Care Theory is essential in satisfying the objectives of global health because it supports an understanding of the issues related to cultural diversity and how they impact healthcare practices throughout the world (Current Nursing, 2012). This theory embodies many of the differences that exist in modern healthcare practices and supports a greater understanding of the issues that are most relevant on a global scale (Current Nursing, 2012). This theory is applicable because it represents a call to action to consider cultural differences when providing care and treatment to different population groups, but not at the expense of the quality of care that is provided (Current Nursing, 2012). In many countries, the provision of care is largely dependent on cultural diversity and customs, which is essential to a thriving healthcare system; however, diversity must also incorporate the concept of providing maximum care for an individual in need of treatment (Current Nursing, 2012).

Professional nursing is highly relevant to global health because nurses address some of the most critical challenges in providing care and expanding access to treatment for millions of people throughout the world. However, it is also important for nurses working with global health initiatives to recognize the importance of these directives and to consider ways to improve quality of care without compromising principles or other factors in the process. These efforts will ensure that nurses maximize their knowledge and understanding of global health and its scope in order to achieve positive outcomes for people in desperate need of healthcare services throughout the world. Nurses must collaborate with small and large-scale organizations regarding global health issues so that population needs are targeted and are specific. These efforts will ensure that patients are treated in areas where healthcare access is severely limited.

Global health represents a significant set of challenges for clinicians throughout the world. It is important to recognize these concerns and to take the steps that are necessary to provide patients with the best possible outcomes to achieve optimal health. The scope of global health concerns is significant; therefore, it is important to address these concerns and to take the steps that are necessary to collaborate and promote initiatives to fight global health problems. When these objectives are achieved using the knowledge and expertise of nurses, it is likely that there will be many opportunities to treat patients and to educate them regarding positive health. With the assistance of large global organizations, nurses play an important role in shaping outcomes for women throughout the world.

Current Nursing (2012). Transcultural nursing. Retrieved from http://currentnursing.com/nursing_theory/transcultural_nursing.html

Fineberg, H.V., and Hunter, D. J. (2013). A global view of health – an unfolding series. T he New England Journal of Medicine, 368(1), 78-79.

Imva.org (2013). Bilateral agencies. Retrieved from http://www.imva.org/Pages/orgfrm.htm

Sundewall, J., Chansa, C., Tomson, G., Forsberg, B.C., and Mudenda, D. (2009). Global health initiatives and country health systems. The Lancet, 374, 1237.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Helping People: Compassion, Essay Example

Why Is There a Need to Breastfeed, Research Paper Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Open access

- Published: 07 April 2020

What is global health? Key concepts and clarification of misperceptions

Report of the 2019 GHRP editorial meeting

- Xinguang Chen 1 , 2 ,

- Hao Li 1 , 3 ,

- Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III 4 ,

- Abu S. Abdullah 5 , 6 ,

- Jiayan Huang 7 ,

- Charlotte Laurence 8 ,

- Xiaohui Liang 1 , 3 ,

- Zhenyu Ma 9 ,

- Zongfu Mao 1 , 3 ,

- Ran Ren 10 ,

- Shaolong Wu 11 ,

- Nan Wang 1 , 3 ,

- Peigang Wang 1 , 3 ,

- Tingting Wang 1 , 3 ,

- Hong Yan 3 &

- Yuliang Zou 3

Global Health Research and Policy volume 5 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

55k Accesses

29 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

The call for “W orking Together to Build a Community of Shared Future for Mankind” requires us to improve people’s health across the globe, while global health development entails a satisfactory answer to a fundamental question: “What is global health?” To promote research, teaching, policymaking, and practice in global health, we summarize the main points on the definition of global health from the Editorial Board Meeting of Global Health Research and Policy, convened in July 2019 in Wuhan, China. The meeting functioned as a platform for free brainstorming, in-depth discussion, and post-meeting synthesizing. Through the meeting, we have reached a consensus that global health can be considered as a general guiding principle, an organizing framework for thinking and action, a new branch of sciences and specialized discipline in the large family of public health and medicine. The word “global” in global health can be subjective or objective, depending on the context and setting. In addition to dual-, multi-country and global, a project or a study conducted at a local area can be global if it (1) is framed with a global perspective, (2) intends to address an issue with global impact, and/or (3) seeks global solutions to an issue, such as frameworks, strategies, policies, laws, and regulations. In this regard, global health is eventually an extension of “international health” by borrowing related knowledge, theories, technologies and methodologies from public health and medicine. Although global health is a concept that will continue to evolve, our conceptualization through group effort provides, to date, a comprehensive understanding. This report helps to inform individuals in the global health community to advance global health science and practice, and recommend to take advantage of the Belt and Road Initiative proposed by China.

“Promoting Health For All” can be considered as the mission of global health for collective efforts to build “a Community of Shared Future for Mankind” first proposed by President Xi Jinping of China in 2013. The concept of global health continues to evolve along with the rapid development in global health research, education, policymaking, and practice. It has been promoted on various platforms for exchange, including conferences, workshops and academic journals. Within the Editorial Board of Global Health Research and Policy (GHRP), many members expressed their own points of view and often disagreed with each other with regard to the concept of global health. Substantial discrepancies in the definition of global health will not only affect the daily work of the Editorial Board of GHRP, but also impede the development of global health sciences.

To promote a better understanding of the term “ global health” , we convened a special session in the 2019 GHRP Editorial Board Meeting on the 7th of July at Wuhan University, China. The session started with a review of previous work on the concept of global health by researchers from different institutions across the globe, followed by free brainstorms, questions-answers and open discussion. Individual participants raised many questions and generously shared their thoughts and understanding of the term global health. The session was ended with a summary co-led by Dr. Xinguang Chen and Dr. Hao Li. Post-meeting efforts were thus organized to further synthesize the opinions and comments gathered during the meeting and post-meeting development through emails, telephone calls and in-person communications. With all these efforts together, concensus have been met on several key concepts and a number of confusions have been clarified regarding global health. In this editorial, we report the main results and conclusions.

A brief history

Our current understanding of the concept of global health is based on information in the literature in the past seven to eight decades. Global health as a scientific term first appeared in the literature in the 1940s [ 1 ]. It was subsequently used by the World Health Organization (WHO) as guidance and theoretical foundation [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Few scholars discussed the concept of global health until the 1990s, and the number of papers on this topic has risen rapidly in the subsequent decade [ 5 ] when global health was promoted under the Global Health Initiative - a global health plan signed by the U.S. President Barack Obama [ 6 ]. As a key part of the national strategy in economic globalization, security and international policies, global health in the United States has promoted collaborations across countries to deal with challenging medical and health issues through federal funding, development aids, capacity building, education, scientific research, policymaking and implementation.

Based on his experience working with Professor Zongfu Mao, the lead Editors-in-Chief, who established the Global Health Institute at Wuhan University in 2011 and launched the GHRP in 2016, Dr. Chen presented his own thoughts surrounding the definition of global health to the 2019 GHRP Editorial Board Meeting. Briefly, Dr. Chen defined global health with a three-dimensional perspective.

First, global health can be considered as a guiding principle, a branch of health sciences, and a specialized discipline within the broader arena of public health and medicine [ 5 ]. As many researchers posit, global health first serves as a guiding principle for people who would like to contribute to the health of all people across the globe [ 5 , 7 , 8 ].

Second, Dr. Chen’s conceptualization of global health is consistent with the opinions of many other scholars. Global health as a branch of sciences focuses primarily on the medical and health issues with global impact or can be effectively addressed through global solutions [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Therefore, the goal of global health science is to understand global medical and health issues and develop global solutions and implications [ 7 , 9 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 ].

Third, according to Dr. Chen, to develop global health as a branch of science in the fields of public health and medicine, a specialized discipline must be established, including educational institutions, research entities, and academic societies. Only with such infrastructure, can the professionals and students in the global health field receive academic training, conduct global health research, exchange and disseminate research findings, and promote global health practices [ 5 , 15 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Developmentally and historically, we have learned and will continue to learn global health from the WHO [ 1 , 4 , 24 , 25 ]. WHO’s projects are often ambitious, involving multiple countries, or even global in scope. Through research and action projects, the WHO has established a solid knowledge base, relevant theories, models, methodologies, valuable data, and lots of experiences that can be directly used in developing global health [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Typical examples include WHO’s efforts for global HIV/AIDS control [ 13 , 30 , 31 , 32 ], and the Primary Healthcare Programs to promote Health For All [ 33 , 34 ].

The definition of Global Health

From published studies in the international literature and our experiences in research, training, teaching and practice, our meeting reached a consensus-global health is a newly established branch of health sciences, growing out from medicine, public health and international health, with much input from the WHO. What makes global health different from them is that (1) global health deals with only medical and health issues with global impact [ 35 , 5 , 36 , 10 , 14 , 2 ] the main task of global health is to seek for global solutions to the issues with global health impact [ 7 , 18 , 37 ]; and (3) the ultimate goal is to use the power of academic research and science to promote health for all, and to improve health equity and reduce health disparities [ 7 , 14 , 15 , 18 , 38 ]. Therefore, global health targets populations in all countries and involves all sectors beyond medical and health systems, although global health research and practice can be conducted locally [ 39 ].

As a branch of medical and health sciences, global health has three fundamental tasks: (1) to master the spatio-temporal patterns of a medical and/or health issue across the globe to gain a better understanding of the issue and to assess its global impact [ 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]; (2) to investigate the determinants and influential factors associated with medical and health issues that are known to have global impact [ 15 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]; and (3) to establish evidence-based global solutions, including strategies, frameworks, governances, policies, regulations and laws [ 14 , 15 , 28 , 38 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ].

Like public health, medicine, and other branches of sciences, global health should have three basic functions : The first function is to generate new knowledge and theories about global health issues, influential factors, and develop global solutions. The second function is to distribute the knowledge through education, training, publication and other forms of knowledge sharing. The last function is to apply the global health knowledge, theories, and intervention strategies in practice to solve global health problems.

Understanding the word “global”

Confusion in understanding the term ‘global health’ has largely resulted from our understanding of the word “global”. There are few discrepancies when the word ‘global’ is used in other settings such as in geography. In there, the world global physically pertains to the Earth we live on, including all people and all countries in the world. However, discrepancies appear when the word “global” is combined with the word “health” to form the term “global health”. Following the word “global” literately, an institution, a research project, or an article can be considered as global only if it encompasses all people and all countries in the world. If we follow this understanding, few of the work we are doing now belong to global health; even the work by WHO are for member countries only, not for all people and all countries in the world. But most studies published in various global health journals, including those in our GHRP, are conducted at a local or international level. How could this global health happen?

The argument presented above leads to another conceptualization: Global health means health for a very large group of people in a very large geographic area such as the Western Pacific, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Along with this line of understanding, an institution, a research project or an article involving multi-countries and places can be considered as global, including those conducted in countries involved in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) [ 26 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. They are considered as global because they meet our definitions of global health which focus on medical and health issues with global impact or look for global solutions to a medical or health issue [ 5 , 7 , 22 ].

One step further, the word ‘global’ can be considered as a concept of goal-setting in global health. Typical examples of this understanding are the goals established for a global health institution, for faculty specialized in global health, and for students who major or minor in global health. Although few of the global health institutions, scholars and students have conducted or are going to conduct research studies with a global sample or delivered interventions to all people in all countries, all of them share a common goal: Preventing diseases and promoting health for all people in the world. For example, preventing HIV transmission within Wuhan would not necessarily be a global health project; but the same project can be considered as global if it is guided by a global perspective, analyzed with methods with global link such as phylogenetic analysis [ 52 , 53 ], and the goal is to contribute to global implications to end HIV/AIDS epidemic.

The concept of global impact

Global impact is a key concept for global health. Different from other public health and medical disciplines, global health can address any issue that has a global impact on the health of human kind, including health system problems that have already affected or will affect a large number of people or countries across the globe. Three illustrative examples are (1) the SARS epidemic that occurred in several areas in Hong Kong could spread globally in a short period [ 11 ] to cause many medical and public health challenges [ 54 , 55 ]; (2) the global epidemic of HIV/AIDS [ 13 ]; and the novel coronavirus epidemic first broke out in December 2019 in Wuhan and quickly spread to many countries in the world [ 56 ].

Along with rapid and unevenly paced globalization, economic growth, and technological development, more and more medical and health issues with global impact emerge. Typical examples include growing health disparities, migration-related medical and health issues, issues related to internet abuse, the spread of sedentary lifestyles and lack of physical activity, obesity, increasing rates of substance abuse, depression, suicide and many other emerging mental health issues, and so on [ 10 , 23 , 36 , 42 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ]. GHRP is expecting to receive and publish more studies targeting these issues guided by a global health perspective and supports more researchers to look for global solutions to these issues.

The concept of global solution

Another concept parallel to global impact is global solution . What do we mean by global solutions? Different from the conventional understanding in public health and medicine, global health selectively targets issues with global impact. Such issues often can only be effectively solved at the macro level through cross-cultural, international, and/or even global collaboration and cooperation among different entities and stakeholders. Furthermore, as long as the problem is solved, it will benefit a large number of population. We term this type of interventions as a global solution. For example, the 90–90-90 strategy promoted by the WHO is a global solution to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic [ 61 , 62 ]; the measures used to end the SARS epidemic is a global solution [ 11 ]; and the ongoing measures to control influenza [ 63 , 64 ] and malaria [ 45 , 65 ], and the measures taken by China, WHO and many countries in the world to control the new coronaviral epidemic started in China are also great examples of global solutions [ 66 ].

Global solutions are also needed for many emerging health problems, including cardiovascular diseases, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, internet abuse, drug abuse, tobacco smoking, suicide, and other problems [ 29 , 44 ]. As described earlier, global solutions are not often a medical intervention or a procedure for individual patients but frameworks, policies, strategies, laws and regulations. Using social media to deliver interventions represents a promising approach in establishment of global solutions, given its power to penetrate physical barriers and can reach a large body of audience quickly.

Types of Global Health researches

One challenge to GHRP editors (and authors alike) is how to judge whether a research study is global? Based on the new definition of global health we proposed as described above, two types of studies are considered as global and will receive further reviews for publication consideration. Type I includes projects or studies that involve multiple countries with diverse backgrounds or cover a large diverse populations residing in a broad geographical area. Type II includes projects or studies guided by a global perspective, although they may use data from a local population or a local territory. Relative to Type I, we anticipate more Type II project and studies in the field of global health. Type I study is easy to assess, but caution is needed to assess if a project or a study is Type II. Therefore, we propose the following three points for consideration: (1) if the targeted issues are of global health impact, (2) if the research is attempted to understand an issue with a global perspective, and (3) if the research purpose is to seek for a global solution.

An illustrative example of Type I studies is the epidemic and control of SARS in Hong Kong [ 11 , 67 ]. Although started locally, SARS presents a global threat; while controlling the epidemic requires international and global collaboration, including measures to confine the infected and measures to block the transmission paths and measures to protect vulnerable populations, not simply the provisions of vaccines and medicines. HIV/AIDS presents another example of Type I project. The impact of HIV/AIDS is global. Any HIV/AIDS studies regardless of their scope will be global as long as it contributes to the global efforts to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030 [ 61 , 62 ]. Lastly, an investigation of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in a country, in Nepal for example, can be considered as global if the study is framed from a global perspective [ 44 ].

The discussion presented above suggests that in addition to scope, the purpose of a project or study can determine if it is global. A pharmaceutical company can target all people in the world to develop a new drug. The research would be considered as global if the purpose is to improve the medical and health conditions of the global population. However, it would not be considered as global if the purpose is purely to pursue profit. A research study on a medical or health problem among rural-to-urban migrants in China [ 57 , 58 , 60 ] can be considered as global if the researchers frame the study with a global perspective and include an objective to inform other countries in the world to deal with the same or similar issues.

Think globally and act locally

The catchphrase “think globally and act locally” presents another guiding principle for global health and can be used to help determine whether a medical or public health research project or a study is global. First, thinking globally and acting locally means to learn from each other in understanding and solving local health problems with the broadest perspective possible. Taking traffic accidents as an example, traffic accidents increase rapidly in many countries undergoing rapid economic growth [ 68 , 69 ]. There are two approaches to the problem: (1) locally focused approach: conducting research studies locally to identify influential factors and to seek for solutions based on local research findings; or (2) a globally focused approach: conducting the same research with a global perspective by learning from other countries with successful solutions to issues related traffic accidents [ 70 ].

Second, thinking globally and acting locally means adopting solutions that haven been proven effective in other comparable settings. It may greatly increase the efficiency to solve many global health issues if we approach these issues with a globally focused perspective. For example, vector-borne diseases are very prevalent among people living in many countries in Africa and Latin America, such as malaria, dengue, and chikungunya [ 45 , 71 , 72 ]. We would be able to control these epidemics by directly adopting the successful strategy of massive use of bed nets that has been proven to be effective and cost-saving [ 73 ]. Unfortunately, this strategy is included only as “simple alternative measures” in the so-called global vector-borne disease control in these countries, while most resources are channeled towards more advanced technologies and vaccinations [ 16 , 19 , 74 ].

Third, thinking globally and acting locally means learning from each other at different levels. At the individual level, people in high income countries can learn from those in low- and mid-income countries (LMICs) to be physically more active, such as playing Taiji, Yoga, etc.; while people in LMICs can learn from those in high income countries to improve their hygiene, life styles, personal health management, etc. At the population level, communities, organizations, governments, and countries can learn from each other in understanding their own medical and health problems and healthcare systems, and to seek solutions for these problems. For example, China can learn from the United States to deal with health issues of rural to urban migrants [ 75 ]; and the United States can learn from China to build three-tier health care systems to deliver primary care and prevention measures to improve health equality.

Lastly, thinking globally and acting locally means opportunities to conduct global health research and to be able to exchange research findings and experiences across the globe; even without traveling to another country. For example, international immigrants and international students present a unique opportunity for global health research in a local city [ 5 , 76 ]. To be global, literature search and review remains the most important approach for us to learn from each other besides conducting collaborative work with the like-minded researchers across countries; rapid development in big data and machine learning provide another powerful approach for global health research. Institutions and programs for global health provides a formal venue for such learning and exchange opportunities.

Reframing a local research study as global