15 Organ Donation Pros and Cons

We never know when tragedy might strike. We never known when an illness may develop. Some people may even be born with a genetic disorder or disease and require help. That is why the current system of organ donations is such an integral part of our healthcare system.

Thanks to modernizing technologies, it is possible for more people to become living donors than ever before. It is also very easy to list yourself as an organ donor should something happen to you, allowing you to save multiple lives with one final act of caring and grace.

There are some organ donation pros and cons that should be thought about if you’re wondering if becoming an organ donor is the right decision for you.

Here Are the Pros of Organ Donation

1. It is possible for one organ donor to save up to 8 lives. More than 100,000 people just in the United States are waiting for an organ transplant right now. This includes critical organs, such as the heart, the liver, and the kidneys. When a person registers as an organ donor, it becomes possible to help save lives in ways that you may have never thought possible before.

2. It offers people a second chance at life. People who are waiting for an organ transplant are often dependent on costly treatments to survive. A person waiting for a kidney transplant, for example, may need to visit a dialysis clinic multiple times per week to have their blood cleaned. By being able to donate an organ, it becomes possible for that individual to return to a somewhat normal lifestyle that doesn’t have the same costly procedures that need to happen on a regular basis.

3. It can offer a sense of closure. For organ donations which occur out of tragedy, the process of organ donation can help families to find a sense of closure that wouldn’t happen otherwise. Knowing that the heart of a son, daughter, father, or mother continues to beat on in the chest of someone else can be a comforting experience. It won’t eliminate the grief that comes from losing a loved one, but it does communicate the idea that their loss is not in vain. Letting someone continue with their life is a gift that really does keep on giving.

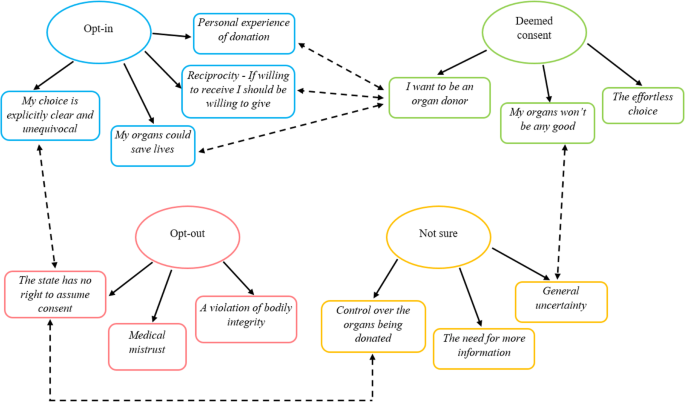

4. It is possible to help someone right now. If someone is a direct match for an individual on the organ transplant list, then it is possible to help a person in need right now. You can donate certain organs while you are still alive. Living donations right now include a kidney, portions of the liver, portions of the lung or pancreas, and some intestinal tissues as well. If you are not comfortable with this type of living donation, then consider donating blood.

5. There are no age restrictions on being an organ donor. Anyone can be an organ donor, including children. The only restrictions in place are related to the age of certain organs for some individuals and that children under the age of 18 must have the consent of a parent or guardian to provide a donation.

6. It allows for the potential of medical research advances. Organ donation may not always be possible to help someone else live a normal life, but that doesn’t completely exclude the ability to donate to help others. People can make donation to benefit science and medical research. This may include donating a specific organ, such as a heart or their brain. It can even include donating their entire body. For those who may have a rare disease or genetic condition, a donation such as this offers the potential of saving more lives through the knowledge gained.

7. Living donations are free. If you are approved as a match and make a living donation for someone in need, then the medical procedure and recovery needs you have are free of charge. The costs related to you are usually not passed on to the organ recipient either, as many physicians will provide their services free of charge. Even if there are recovery complications, your medical costs are covered.

8. More organ transplants are happening today than ever before. In 2016, there were more than 33,500 organ transplants that occurred in the United States. That set a new record for completed transplants. Thanks to improvements in medical procedures and technology innovations, there has been a 20% increase in successful transplants from 2012-2016. With more than 8,000 transplants completed in the first quarter of 2017, that is a trend which looks to be continuing.

Here Are the Cons of Organ Donation

1. It can prolong the grieving period of a family. For an organ donation to be successful, it may be necessary to keep a loved one on life support for an extended period. This helps to keep the tissues which will be donated in a healthy state. Organ donations do not occur unless a person is declared to be brain dead, but the process of life support can make it feel like a loved one is still alive. When there is the presence of life, there is often hope, and having that hope can make the grief even stronger.

2. There is not always a choice for the donation. Many families do not have a choice in who gets the organs that are being donated by a loved one through tragedy. They are simply given to the person who is on the organ donation list who is a match and in the direst of need. This means someone of a different faith, a different political position, or different culture may receive the organ and that can be difficult for some families to accept. Living donations are often matched to other family members, while direct matches for humanitarian purposes are also possible, so this key point doesn’t always apply.

3. Not everyone can become an organ donor. Although many people can become an organ donor through a simple authorization process, not everyone is eligible. There are age-related restrictions on certain organs. You cannot be over 80 years old to make a cornea donation and must be younger than 60 to donate heart valves or tendons. People with certain existing medical conditions, such as being HIV-positive, having metastasized cancer in the last 12 months, or being diagnosed with Creuzfeldt-Jacob Disease will also prevent a donation.

4. Organ donations can lead to other health problems. To become a living donor, a surgery or medical procedure is required. Any surgery offers a risk to the person that may include death. Other health problems can develop after a surgery that requires a lifestyle change. People who donate bone marrow, for example, may be restricted in the future activities for a lifetime. Those who donate a kidney may be prohibited from consuming alcohol. For those who receive an organ, there is a 10% risk of diabetes development.

5. Not every organ which is donated will be accepted. Organ rejection is a very real possibility for those who receive a transplant. Even when there is a direct match, there is always the chance that the transplant will be rejected. Those who receive a transplant will often be required to take immunosuppressant medications for the rest of their lives to reduce the chances of this issue from occurring.

6. Employers do not always have leave policies for living donations. Only 12 states in the US currently have organ or bone marrow donor leave policies that impact private sector employees. Federal government employees receive 30 days of paid leave for an organ donation and 7 days of paid leave for a bone marrow donation that is over and above the employee’s sick and annual leave. Most states have similar donor leave laws for state employees, but some offer the 30 days of leave unpaid.

7. Organ transplants are incredibly expensive. In the United States, the cost of a liver transplant is $71,000, plus an additional $25,000 for every 30 days of care pre-transplant. For those who need a heart-lung transplant, the cost is $130,000, with an additional $56,000 for every 30 days of care pre-transplant. For many organ recipients, their total care cost exceeds $1 million, with heart-lung transplant recipients facing a cost of $2.3 million. Part of this cost is due to the wait time to receive an organ transplant. For some organs, the average wait time can be 3-5 years in some regions of the United States.

The pros and cons of organ donation show that you can get involved in some way right now. You can register to become an organ donor. You can register your children. You can also be tested to see if you could become a living donor for someone who is in need right now. Someone is added to the national organ transplant waiting list every 10 minutes, on average, in the United States. Since one organ donor can save up to 8 lives, the time to act is now.

- Organ Donation

5 Pros and Cons of Being an Organ Donor Explained

Updated 06/13/2022

Published 11/13/2020

Sherrie Johnson, BA in Liberal Studies

Contributing writer

Cake values integrity and transparency. We follow a strict editorial process to provide you with the best content possible. We also may earn commission from purchases made through affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Learn more in our affiliate disclosure .

If you’re thinking about becoming an organ donor, it’s important to weigh all the pros and cons before making the choice. Becoming a living donor or a donor after you die is a decision that you shouldn’t take lightly. Not only does your being a donor potentially impact you, but it can also impact your immediate family and even your closest friends. Learn how to become a donor, what it involves, and familiarize yourself with the pros and cons of organ donation.

Jump ahead to these sections:

Pros of becoming an organ donor, cons of becoming an organ donor.

There are numerous benefits to becoming an organ donor, whether you decide to become a living donor or a donor after your death. Here are some of the things you can look forward to if you choose to sign up for the national organ donor registry.

1. Anyone can donate at any age

Many people assume that they can’t be an organ donor because they’re not the right age, in good enough health, or even have the right ethnic background to donate. However, that isn’t the case at all!

You can choose to become an organ donor at any age. If you’re under 18, you can sign up to become a living donor or a donor after death with the consent of a parent. For all other ages, you can choose to become a donor at any time.

People of all ages need organs, making your donation critical — no matter your age. Donors range from newborns all the way up to those in their 90s.

Worried about a health condition? There are very few reasons why your organs wouldn’t be accepted for donation.

Outside of active cancer or a systemic infection, your organs would likely be healthy enough to be used. Common health issues like high blood pressure and diabetes — reasons why some might think they’d become ineligible — are not reasons for rejection at all.

If religious beliefs cause you to question whether you should sign up, many religions do believe in the validity of being a donor. Religions that specifically support organ donation include most branches of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

Living or deceased

Not only can you decide to become a donor at the point of your death, but you can also decide to become a living donor. While the majority of organs needed by patients can only be taken after someone dies, several organs can be donated by those still living including:

- Part of a liver

- Part of a lung

- Part of a pancreas

- Part of an intestine

- Some tissues

Since we have two kidneys and only need one to function, the whole organ can be removed from a living donor. Pieces of the liver, lung, pancreas, or intestine can be taken and the body will compensate for the missing piece.

2. You can save one life — or more

When you choose to be an organ donor, you’re not just impacting one person’s life. As a donor, you have the opportunity to save up to eight lives with your:

- Pair of lungs

Once each of these organs is removed, they can go to eight different people in desperate need. And that’s just the major organs. If you choose to donate tissue, eyes, and other parts, your donation can go even further.

3. Your death can be more meaningful

For many families, the tragic and untimely death of a loved one lacks meaning and feels senseless. Some would even say their death is “wasteful” as such a young life was wasted when they had so much life left to live.

By donating your organs, even tragic and untimely deaths don’t have to be meaningless. Though death is still tragic and loss deeply painful, many families of organ donors say that they were given hope when their loved one’s organs were given to someone in need. A seemingly meaningless death becomes something meaningful and allows a loved one’s legacy to live on through the life of the organ recipient.

4. You can further medical research

If you don’t want to be buried and you’re looking for alternatives to cremation , consider donating your body to science . When you do, your body might be used to help medical students train and become doctors.

Your body could also be used to provide study and research on diseases. Who knows? Your donation could be the reason for a major medical breakthrough that transforms the medical world.

5. You can help someone right now

As a living donor, you don’t have to wait until your death to donate. You can help someone in need right now.

You could be a match for a kidney for a close friend or family member, or give part of your liver, pancreas, lungs, or intestines to a complete stranger. By becoming a living donor, you can do something to change the world right now.

You can find numerous benefits to becoming an organ donor but there are some cons to think through as well. Here are several to consider before deciding what to choose.

1. It can lengthen the grieving process

When an organ donor passes away, the hospital keeps the deceased person on life support until recipient matches can be found for their organs. This is done to keep blood flowing through the body and the organs alive even though the person is legally and clinically deceased.

This can be difficult for family members who must wait until the organs have been taken for the body to be transported and prepared for burial. It lengthens the waiting process and can prolong grieving while the family waits for closure.

In some cases, keeping the person on life support can also provide a false sense of hope that a loved one will somehow get better. Once the organs are removed and the person is taken off of life support, it can feel like the family has to deal with death a second time.

2. You may not get to choose the recipient

If you’re a living donor, you might choose who to give your kidney to. If a family member or friend, for example, needs a kidney and you’re a match, you can volunteer to have your kidney go to that person.

When you pass away, your organs will go to the most eligible recipient on the waiting list. You won’t get to choose who receives your heart or liver. Some potential donors and their family members might find this aspect difficult to deal with.

Family members also may not get to meet the recipient or their families. If organ donation is chosen to provide a legacy, the family may be disappointed. Not all donors and recipients are able to meet each other.

3. Living donors can encounter health complications

As a living donor, you will undergo surgery to remove the organ or pieces of organs you plan to donate. As with any surgery, health complications can occur, from excessive bleeding during surgery to infection and scarring.

Though there is little long-term information with regard to health complications for living donors, some studies have shown that kidney donors may deal with long-term issues including high blood pressure. A small percentage end up needing dialysis or a transplant themselves.

Living liver donors are at a slightly greater risk for long-term health complications, including abdominal bleeding, intestinal problems such as blockages or tears, organ impairment or failure, and the need for a transplant.

4. Organ rejection could happen for recipients

Organ donation and the medications that help a recipient’s body accept the organ have gotten better and better over the years. Unfortunately, the reality still exists that a recipient’s body may reject the organ, despite anti-rejection medications. If this is the case, it can be hard on the donor’s family.

In the case where a donor’s family gets to know the recipient, it can be especially painful if, after several months, the transplanted organ fails or is rejected. For the families of donors, it can feel like they’re losing their loved one all over again, this time because the recipient hasn’t been helped permanently by the donated organ.

5. Families may not agree with the decision

Not all families accept the practice of organ donation and you may find that your family disagrees with your choice. Disagreements arise due to religious and personal preferences. The decision can cause some family members to become upset.

Should you wish to sign up for the national registry of organ donors and your family does not agree with your choice, it’s essential that you express your wishes in writing. In addition to placing the donor sticker on your driver’s license, file an advanced directive.

Once notarized, the advanced directive is a legally binding document that communicates to doctors and caregivers what you want to happen medically should you become uncommunicative or die. Have a copy placed in your permanent medical files and give copies to your immediate family members as well.

To avoid confusion and arguments at the time of your death, be sure that your funeral wishes are known by all close relatives and even close friends.

Giving Hope and Life

Organ donation is a powerful tool used to offer thousands of people the gift of hope and new life each year. If you don’t have any objections to signing up, you can become an organ donor and give people across America a second chance at life.

- “Benefits and Risks of Becoming a Living Donor.” Living Donation, American Transplant Foundation, 2020. americantransplantfoundation.org/about-transplant/living-donation/about-living-donation/#:~:text=Risks%20to%20the%20Donor,other%20organs%2C%20and%20even%20death

- “Organ Donation Statistics.” Organ Donor, U.S. Government Information on Organ Donation and Transplantation, 2020. organdonor.gov/statistics-stories/statistics.html

- “Making Your Last Wishes Known.” A to Z Guides, WebMD, 7 July 2000. webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/making-your-last-wishes-known#1

Categories:

- How To Share Your Wishes

You may also like

What’s the Organ Donation Process After Death? 10 Steps

How to Become an Organ Donor in the US (2021 Update)

Donor Stewardship Plans: Definition+ FREE Template

How to Organize & Share Your Final Wishes for Free

Benefits and risks of becoming a living organ donor

Please check out our Living Donation Guide for more information and resources.

Living Donation Benefits

For the recipient:.

- Quality of life: Transplants can greatly improve a recipient’s health and quality of life, allowing them to return to normal activities. They can spend more time with family and friends, be more physically active, and pursue their interests more fully.

- Increased life span: A kidney transplant dramatically increases the life span of a patient by about 10 years and improves their quality of life. Dialysis, while clearly a life-saving treatment, it is a less-than-perfect replacement for an actual human kidney. In addition, people who undergo a transplant will no longer require weekly dialysis treatments or have the side effects of dialysis such as nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure, muscle cramping, and itchy skin.

- Shorter waiting time : Due to the lack of organs available for transplant, patients on the national transplant list often face long wait times (sometimes several years) before they are able to receive a transplant from a deceased donor. Patients who find a suitable living donor do not have to wait on the list.

- Better results : Transplant candidates generally have better results when they receive organs from living donors as compared to organs from deceased donors. Often, transplanted organs from living donors have greater longevity than those from deceased donors. Genetic matches between living donors and candidates may lessen the risk of rejection.

- Kidneys and Livers Function Almost Immediately : A kidney or liver from a living donor usually functions immediately in the recipient. In uncommon cases, some kidneys from deceased donors do not work immediately, and as a result, the patient may require dialysis until the kidney starts to function.

For the Living Donor:

- Positive emotional experiences: The gift of an organ can save the life of a transplant candidate. The experience of providing this special gift to a person in need can serve be a positive aspect of donation.

- More time with your loved one: Donating an organ can increase the time you have to spend with your loved one as well as the quality of that time.

For Both the Recipient and the Living Donor:

- Flexible time frame : Surgery can be scheduled at a time that is convenient for both the donor and recipient.

- Removes a candidate from the list: A living donor removes a candidate from the national transplant waiting list, which is currently above 114,000 people. This allows the people on the waiting list who cannot find a living donor a better chance of receiving the gift of life from a deceased donor.

- Immediate impact: The impact of a transplant is so striking that recipients often look noticeably healthier as soon as they emerge from surgery.

Living Donation Impacts/Risks

Living donation does not change life expectancy, and after recovery from the surgery, most donors go on to live happy, healthy, and active lives.

For kidney donors, the usual recovery time after the surgery is short, and donors can generally resume their normal home and working lives within two to six weeks. Liver donors typically need a minimum of two months to resume their normal home and working lives.

Although transplantation is highly successful, complications for the donor and recipient can arise. Make sure to check out common myths and concerns about living donation. Be sure to talk to your doctor about what to expect.

Effects on the Body

For living kidney donors, the remaining kidney will enlarge slightly to do the work that two healthy kidneys share. The liver has the ability to regenerate and regain full function. Lungs and pancreas do not regenerate, but donors usually do not experience problems with reduced function.

Risks to the Donor

As with any other surgery, there are both short and long term risks involved in living donation. Surgical complications can include pain, infection, blood loss, blood clots, allergic reactions to anesthesia, pneumonia, injury to surrounding tissue or other organs, and even death. As transplant surgeries are becoming more common and surgical techniques are advancing, risks involved with living donation continue to decrease.

There has been no national systematic long-term data collection on the risks associated with living organ donation. However, there are studies that are currently gathering such information. Based upon limited information that is currently available, overall risks are considered to be low. Risks can differ among donors and the type of organ.

For kidney donors, there is only a 1% lifetime increase in the donor’s own risk of kidney failure. To put this into perspective, the general population has a 3% risk for kidney failure. Overall, there is only a three in 10,000 risk of dying during surgery and in general donation neither reduces life expectancy nor prevents donors from living normal, healthy lives. Some possible long-term risks of donating a kidney may include high blood pressure (hypertension); large amount of protein in the urine; hernia; organ impairment or failure that leads to the need for dialysis or transplantation.

Liver transplantation carries greater risk for both the donor and the recipient than kidney transplantation. Some possible long-term risks associated with donating a lobe of the liver may include wound infections; hernia; abdominal bleeding; bile leakage; narrowing of the bile duct; intestinal problems including blockages and tears; organ impairment or failure that leads to the need for transplantation.

Limited Long-Term Data about Living Donors

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) has limited long-term data available on how living donors do over time. Based on OPTN data from 1998 through 2007, of the 3,086 individuals who were living liver donors, at least four* have been listed for a liver transplant due to complications related to the donation surgery. Of the 59,075 individuals who were living kidney donors from 1998 to 2007, at least 11* have been listed for a kidney transplant. However, the medical problems that caused these kidney donors to be listed for transplant may or may not be connected to the donation.

*This total only captures data on transplant candidates who are known to the OPTN/UNOS to be previous donors.

Real Life Living Donor Heroes!

Chelsey donated a kidney to her college roommate, Ellen. Chelsey is now a 1+1=LIFE Mentorship mentor and member of our Young Professionals Group (TLC).

Steve donated a kidney to his daughter, Kelsey. He is now a Team Transplant cyclist and 1+1=LIFE Mentorship mentor .

Keith (right) received the GIFT OF LIFE when he was given a kidney from his step-son Jonny (left). Keith is now a mentor in our 1+1=LIFE Mentorship Program .

Other Considerations

Studies have shown that donating a kidney or part of the liver does not affect a woman’s ability to have children. However, it is important that you tell your doctors of your plans to have children. Each case is different, and your doctor may have additional recommendations given your medical history. A recent study from Toronto says that women who have donated a kidney are at higher risk of developing gestational hypertension or pre-eclampsia during pregnancies that follow the donation. The study suggests the increase in risk is not enormous (about a 6% increase), and in fact most women who have donated a kidney can safely carry a pregnancy to term. More information about the study can be found here.

Police, Fire, and Military Service

Some police and fire departments or branches of the military will not accept individuals with only one kidney. Be sure to talk to your superior if you are considering becoming a living donor.

Please note: As detailed in our Privacy Policy , the information contained on this site does NOT substitute medical advice. Please discuss any medical questions, considerations, and decisions with your doctor

Living organ donations are categorized in the following ways:

- Non-Directed Living Organ Donation

- Directed Living Organ donation

Living organ donors are usually between the ages of 18 and 60 year old . However, acceptable ages may vary by transplant center and the health of the donor candidate.

The prospective donor must have several points of compatibility including a compatible blood type , tissue type, and other markers.

The donor candidate is carefully evaluated by lab tests, physical examination, and psychological evaluation to ensure that the candidate is healthy enough to donate and that he or she is making an informed decision. The decision about whether to accept the donor is then made by the health care team at the transplant center.

Please note: It is illegal to sell human organs for the purpose of transplantation. Federal law stipulates that no person may be paid and/or receive valuable consideration for donating an organ.

See Living Donor Laws – Federal and State by State

Need support? Connect with a Mentor .

See our Living Donor Guide for more information.

Other Living Donation Resources

The American Transplant Foundation (ATF) is the only 501 (c)(3) nonprofit in the country that provides three tiers of support for living donors, transplant recipients, and their families. We go beyond awareness by providing real help to patients who need it the most. Join us and be part of the community fighting for the lives of those on the transplant wait list.

Join our online community where you can share, reflect, connect.

Quick links.

Donate Today! Honor a Loved One Potential Living Donor Database Download our Media Kit Legislation 1+1=LIFE Mentorship Program Join Save a Life Giving Club Fundraise Online Shop

Sign up now to receive alerts, updates, and invitations to events

Email Address *

Why Don't More People Want to Donate Their Organs?

Around 21 Americans die each day waiting for transplants. What's behind the reluctance to posthumously save a life?

In 1998, Adam Vasser, a 13-year-old teenager who loved playing baseball, was vacationing in Montana with his family when he suddenly came down with what felt like the flu. When he had trouble breathing and his ankles became swollen, his parents took him to a nearby clinic where the doctor on duty checked his vitals and sent him directly to the hospital across the street. By the time the family arrived at the hospital a few minutes later, Adam was in complete heart failure.

For months, Adam waited in a hospital for a heart transplant, during which time his heart was only able to pump with the assistance of a left-ventricular assist device (LVAD). “It was the size of a washing machine and it had two tubes that went through my chest into my left ventricle to help it pump blood,” Adam, now a 30-year-old teacher in the San Francisco Bay Area, recalls. “My official diagnosis was idiopathic viral cardiomyopathy. Meaning, basically, a virus of unknown origin had attacked my heart.” Four and a half months after getting sick, Adam underwent a heart transplant that saved his life.

But thousands of people aren’t as lucky. In the United States alone, 21 people die everyday waiting for an organ transplant. Though about 45 percent of American adults are registered organ donors, it varies widely by state. More than 80 percent of adults in Alaska were registered donors in 2012, compared to only 12.7 percent in New York, for example . In New York alone, there are more than 10,000 people currently waiting for organ transplants. According to data compiled by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network , more than 500 people died in New York last year, waiting for an organ to become available.

Given this shortage of organs, why don’t more people donate?

It’s a touchy question, something non-donors aren’t necessarily keen to answer. But experts say there is a large disparity between the number of people who say that they support organ donation in theory and the number of people who actually register. In the U.K., for example, more than 90 percent of people say they support organ donation in opinion polls, but less than one-third are registered donors. What keeps well-intentioned people from ultimately donating is something that academics, doctors, and organ-donation activists are trying to figure out.

In a recent literature review , researchers at the University of Geneva examined several social and psychological reasons why people choose not to donate, either by not registering as an organ donor during their lives, or electing not to donate the organs of their next of kin.

The study cites mistrust in the medical field and lack of understanding about brain death as major barriers to donation. A 2002 study in Australia, for example, illustrates the controversy surrounding brain death . Some participants indicated that they wouldn’t donate the organs of their next of kin if his or her heart were still beating, even if they were proclaimed brain-dead.

Studies have also shown that the less people trust medical professionals, the less likely they are to donate. The mistrust can come from personal experience—one study in New York showed , for example, that next of kin who perceived a lower quality of care during a loved one’s final days were less likely to consent to donation—or from misconceptions about how the medical community treats registered organ donors.

“There are a lot of people who subscribe to the belief that if a doctor knows you are a registered donor, they won’t do everything they can to save your life,” says Brian Quick , an associate professor of communication at the University of Illinois.

More than half of people, one study shows, have gotten information regarding organ donation from TV, so it makes sense that researchers are concerned with how fictional medical dramas can influence our attitudes toward medical professionals (a topic The Atlantic covered in August ).

Recommended Reading

When are you really an adult.

A Kidnapping Gone Very Wrong

Dear Therapist: I Don’t Approve of My Daughter-in-Law’s Parenting

Quick and his colleagues have studied how watching Grey’s Anatomy can influence people’s attitudes toward the medical community. “We found that heavy viewers of the show saw Grey’s Anatomy as realistic, meaning that they felt the images and the stories were realistic. And the more realistic they saw these stories, the more likely they were to buy into medical mistrust.”

Religion is another factor that repeatedly comes up in research. While many religions consider organ donation an act of love, some research has shown that Catholics are less likely to donate than other religious groups, despite the Vatican’s official position in favor of it. It seems that this is due to a belief in the afterlife and the concern for maintaining body integrity .

It could be that people are simply uncomfortable or unwilling to talk about death at all. In a survey of more than 4,000 students and their families from six universities throughout the United States, some people indicated concern that making plans for death would bring it about prematurely (which might also account for the fact that only 25 percent of Americans have advance directives). Others can’t shake the “ick” factor. Defined by researchers as “a basic disgust response to the idea of organ procurement or transplantation,” a 2011 study in Scotland found that non-donors reported higher levels of the ick factor and concern with body integrity than donors.

In a study of British women who had not signed up to be donors, researchers found that they were uncomfortable talking about death, with one participant saying, “The underlying taboo is that you have to be dead, potentially, well, you have to be dead […] Nobody really wants to think about that.” The research suggests that the more matter-of-fact attitude people have when talking about death and normalizing the issue of organ donation, the more likely they are to sign up as donors.

And this is where a lot of people think the solution comes in. “What we’re trying to do in New York is move the cultural needle on the issue,” says Aisha Tator, executive director of the New York Alliance for Donation . “Organized tissue donation should be a cultural norm like we did with bike helmet and seatbelt interventions.” Her organization isn’t the only one. Throughout the United States there have been a smattering of recent educational campaigns and studies on their efficacy. Campaigns have targeted the young , the old , nurses , DMV employees , and ethnic minorities who tend to donate less than white Americans or white Brits.

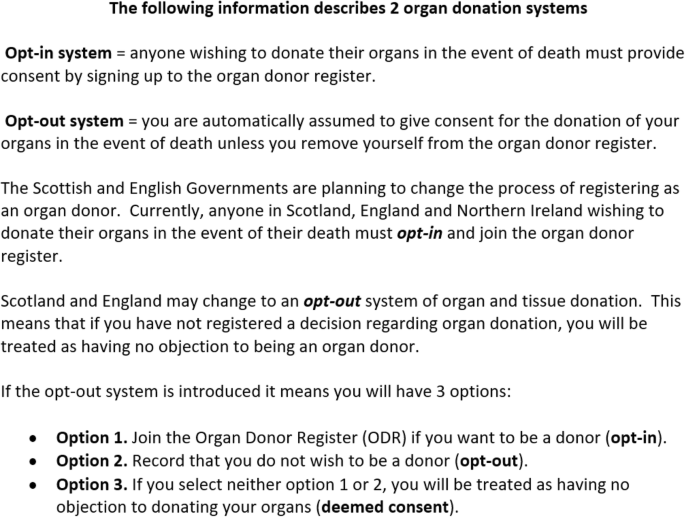

Another, more ambitious, strategy people point to is to change from the United States’ current opt-in system to an opt-out system, which would mean that everyone would be a donor by default, unless they actively opted out.

In a recent study conducted in the U.K., researchers studied the organ-donation systems of 48 countries over 13 years and concluded that Spain, with an opt-out style of consent, had the highest rate of organ donation of the countries studied and represents a successful model to emulate.

But beyond being a political and bureaucratic nightmare to actually make happen, changing the American system to an opt-out system might not fix the problem.

“The Spanish model is held up as the ideal, and in many ways it is,” says Eamonn Ferguson, a professor of health psychology at the University of Nottingham and one of the researchers on the study. “They have an opt-out system, but they also have a very coordinated, hierarchical, interlinked system of well-trained organ-transplant professionals.” Adding to the complexity of the issue is the fact that the rate of live organ donations is lower in countries with opt-out systems.

Some groups of people have tried to take the issue into their own hands. Lifesharers and other organ sharing networks, in which members promise to donate organs upon their death and give priority to fellow member donors, highlight that notions of reciprocity and fairness are incentives for at least some people.

The transplant system in Israel is a case study for how these ideas can be systematized. A change of law in 2010 that prioritizes patients with a history of donation—if a family member donated his or her organs or the patient himself made a living donation or if the patient has been on the donor list for at least three years—has incentivized a significant portion of the population to register as donors.

Preliminary results, published last year, show that the annual deceased organ-donation rate increased from 7.8 organs per million people in 2010 to 11.4 organs per million people in 2011. The number of new registrations per month more than doubled and the total number of candidates waiting for a transplant fell for the first time ever.

The new law, which was coupled with a multimedia campaign called ‘Sign and Be Prioritized’ and a streamlined registration process, has also changed who receives organs.

“More than 35 percent of those who actually got organs after the law was passed got them because of the prioritizing system,” says Dr. Jacob Levee, director of the Heart Transplantation Unit at Sheba Medical Center who spearheaded the change and authored the results. “It’s not just a dead-letter law. We’ve seen an actual change in how organs are being allocated.”

Though the Israeli case is compelling, for some, the decision to donate might not be rational at all. If the idea of someone cutting them open makes people feel sick, they are probably unlikely to sign up.

“Unfortunately unless you’re personally touched by the issue, unless you have a child that gets a virus and suddenly needs a new heart, you don’t really think about it,” Tator says. But it’s not only recipients like Vasser who can be touched by a transplant. The parents of at least one donor have become vocal advocates of organ donation after the loss of their son.

In 2003, Matthew Messina, a 25-year-old student at Chico State, was struck by a drunk driver while riding his bike home from a barbecue. Soon after his family arrived from New York, Matthew was in a coma. After running a series of tests, the neurosurgeon determined that he was brain-dead and recommended taking him off life support.

Matthew’s father Sam Messina says that when the organ-procurement team approached him and his wife, they knew it was something that Matthew, who was a reservist in the Marines and volunteered with handicapped children in his spare time, would have wanted to do.

“We stay in touch with two women in California who received organs from him. Both are married with families,” Sam Messina, who now gives talks about organ donation and is on the board of directors at the Center for Donation and Transplant , told me. “When I look into their eyes, I see a little bit of Matthew moving on.”

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Consumer health

Organ donation: Don't let these myths confuse you

Unsure about donating organs for transplant? Don't let wrong ideas keep you from saving lives.

Connect with others

News, connections and conversations for your health

- Transplant Page - Connect with others Transplant Page

- Transplant Group - Connect with others Transplant Group

Answers to common organ donation questions and concerns.

More than 100,000 people in the U.S. are waiting for an organ transplant.

Sadly, many may never get the call saying that a donor organ has been found. Many may not get that second chance at life. Every day in the U.S., about 17 people die because there aren't enough donor organs for all who wait for a transplant.

It can be hard to think about dying. It can be even harder to think about donating organs and tissue. But organ donors save lives.

Here are answers to some common organ donation myths and concerns.

Myth: If I agree to donate my organs, the hospital staff won't work as hard to save my life.

Fact: When you go to the hospital for treatment, the health care team tries to save your life, not someone else's. You get the best care you can get.

Myth: Maybe I won't really be dead when they sign my death certificate.

Fact: This is a popular topic in tabloids. But in reality, people don't start to wiggle their toes after a health care provider says they're dead. In fact, people who have agreed to organ donation are given more tests to make sure they're dead than are those who aren't donating organs. These tests are done at no charge to their families.

Myth: Organ donation is against my faith.

Fact: Most major faiths accept organ donation. These include Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism, most branches of Judaism and most Protestant faiths. Some religions believe organ donation to be an act of charity. If you don't know where your faith stands on organ donation, ask a member of your clergy.

Myth: I'm younger than 18. I'm too young to make this decision.

Fact: Many states let people younger than 18 register as organ donors. But if you die before your 18th birthday, your parents or legal guardian will make the decision. If you want to be an organ donor, make sure your family is OK with your wishes. Remember, children, too, need organ transplants. They often need organs smaller than adult size.

Myth: People who donate organs or tissues can't have an open-casket funeral.

Fact: Donors' bodies are treated with care and respect. And they're dressed for burial. No one can see that they donated organs or tissues.

Myth: I'm too old to donate. Nobody wants my organs.

Fact: There's no standard cutoff age for donating organs. The decision to use your organs is based on the health of your organs, not age. Let the health care team decide at the time of your death whether your organs and tissues can be transplanted.

Myth: I'm not in the best health. Nobody wants my organs or tissues.

Fact: Very few medical conditions keep you from donating organs. Maybe you can't donate some organs, but other organs and tissues are fine. Again, let the health care team decide at the time of your death whether your organs and tissues can be transplanted.

Myth: I'd like to donate one of my kidneys now. Can I do that if it's not going to a family member?

Fact: Yes. Most living donations are between family members and friends. But you can choose to donate a kidney to a stranger, so long as you're a match. You also can donate other organs and tissues, such as a lung or part of a lung or liver.

If you decide to become a living donor, the health care team at the transplant center asks a lot of questions. They want to make sure you know the risks.

You'll have tests to make sure you're healthy and that the organ you want to donate is in good shape. The health care team also will want to be as sure as possible that the donation won't damage your health.

Myth: Rich and famous people go to the top of the list when they need a donor organ.

Fact: The rich and famous are treated the same as everyone else when it comes to organ donation. True, famous people might get a lot of press after a transplant. But who they are and how much money they have don't help them get an organ. A computer system and strict standards ensure fairness.

Myth: My family will be charged if I donate my organs.

Fact: The organ donor's family never pays for donation. The donor family pays for all the medical care given to save your life before your organs are donated. Sometimes families think those costs are for the organ donation. But the person who gets the organs for transplant pays the costs for removing the organs.

Why you should think about donating organs

Now that you have the facts, you can see that being an organ donor can have a big impact. And your donation helps not just the person getting the organ. By donating your organs and tissue after you die, you can save up to eight lives and improve 75 more. Many families say that knowing their loved one helped others helped them cope with their loss.

Think about being an organ donor if you belong to an ethnic minority group. These include Black Americans, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and Hispanics. People in these groups are more likely than white people to have certain illnesses that affect the kidneys, heart, lung, pancreas and liver.

Some blood types are more common among minority groups. The blood type of the donor usually needs to match the blood type of the person getting an organ. So the need for minority donor organs is high.

How to donate

Becoming an organ donor is easy. Just do the following:

- Sign up with your state's donor registry. Most states have ways to sign up. Check the list at organdonor.gov.

- Mark your choice on your driver's license. Do this when you get or renew your license.

- Tell your family. Make sure your family knows you want to be an organ donor.

Being on your state's organ donation registry and marking your choice on your driver's license or state ID are the best ways to make sure you become a donor. But telling your family also is important because hospitals ask next of kin before taking organs.

However, hospitals don't need to ask for consent if you are 18 or older and are on your state's donor registry or have marked your driver's license or state ID card for organ donation.

If you have named someone to decide about your health care for you if you are not able to do so, make sure that person knows that you want to be an organ donor. You also can include your wishes in a living will if you have one. But the will might not be read right at the time of your death.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Organ donation statistics. Organdonor.gov. https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

- Franklin GF, et al. Evaluation of the potential deceased organ donor (adult). https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

- Theological perspective on organ and tissue donation. United Network for Organ Sharing. https://unos.org/transplant/facts/theological-perspective-on-organ-and-tissue-donation/. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

- Equity access to transplant. United Network for Organ Sharing. https://insights.unos.org/equity-in-access/. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

- Frequently asked questions about organ donation for older adults. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/frequently-asked-questions-about-organ-donation-older-adults. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

- Facts about organ donation. United Network for Organ Sharing. https://unos.org/transplant/facts/. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

- Donate organs while alive. Organdonor.gov. https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/process/living-donation. Accessed Dec. 29, 2022.

Products and Services

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Assortment of Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle

- A Book: Live Younger Longer

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

- Myths about cancer causes

- Emergency essentials: Putting together a survival kit

- Emergency health information

- Kidney donation: Are there long-term risks?

- Living wills

- Osteopathic medicine

- Personal health records

- Telehealth: Technology meets health care

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Organ donation Dont let these myths confuse you

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Disadvantages of Organ Donation: What to Know

Mary Beth holds a Bachelor's Degree in Communications and Journalism and has held several roles in the media industry.

Learn about our Editorial Policy .

Terri is a critical care nurse with over 35 years of experience. She is also a freelance writer and author.

Religious beliefs and fear of the unknown are only two of the several cons of organ donation. Some feel that ethics - both the patient's and the doctor's - also play a large role.

Organ Donation at a Glance

According to Donate Life America , there were a total of 138 million registered organ and tissue donors in the United States. While it is reported that 95% of adults in the U.S. support organ donation, only 54% are registered organ and tissue donors. However, the amount of people who actually need transplants is on the rise, topping out at more than 114,000 individuals on the national waiting list .

Why is it then that roughly 46% percent (nearly half) of the U.S. population who are eligible to be organ donors aren't even registered? Could it be that the benefits of organ donation do not outweigh the disadvantages?

Understanding the Cons of Organ Donation

While some may shun the thought of having their body buried without all of its organs, others don't have a problem with it. Besides not being a suitable donor, there are many reasons why individuals are against organ donation.

Religious and Ethnic Beliefs

Organ and tissue donation is a very personal decision, and most organized religions don't oppose it. Many encourage it and consider it an act of charity. However, some religious and ethnic groups do have stipulations:

- Amish : Approves in organ donation if a person's life will definitely be improved or saved, but is reluctant to participate if the outcome of the transplant is questionable.

- Gypsies (Romany) : Because this group of people share common folk beliefs, they oppose any and all organ and tissue donation. They also believe that a body should be buried with all of its organs intact because the soul maintains its physical self for one year after the individual dies.

- Jehovah's Witnesses : While organ donation is a personal decision, if one decides to go through with the procedure, all organs and tissues must be completely drained of blood first.

- Shinto : The religion concurs with folk belief that a dead body is "impure and dangerous" and injuring a person after he or she dies is a "serious crime." Therefore, they do not support organ or tissue donation.

Fear of Unethical Selling and Buying of Organs

It's true, there is a black market out there for some types of donated organs, especially kidneys and most often, not in the United States. Countries including Bosnia, China, Ukraine, Iran, and Pakistan, where populations are poor, are frequently in the news because residents there illegally - and in some cases legally - sell certain human organs for cash. In the United States, selling your organs is illegal, although some argue that if individuals were paid for the viable organs upon their demise, those on the transplant waiting list may be helped a little sooner. But is buying human organs ethical if it is a matter of life or death? In some countries, citizens don't have much of a choice. Organs from living donors are transplanted from those living in Third World countries into prominent individuals living elsewhere. All because the money is needed for the donors to live. However, in others, organs are stolen. For instance:

- Because of the Japanese cultural beliefs regarding the body after death, there are not many viable donors living there. For many years, affluent citizens went to countries such as Singapore and Taiwan to purchase organs from executed prisoners even though the inmates did not authorize the donation. This was outlawed in 1994 by the World Medical Association.

- However, in China, it is still legal to remove and sell organs from executed prisoners without their consent, sometimes even on the eve of the execution when the individual is still alive.

- In 2004, the director of Willed Body Program at the University of California, Los Angeles was arrested for illegally selling body parts and organs donated to the program by individuals who have died. The deceased individuals donated their bodies to science for research, but instead, the former head of the program received more than $1 million for the organs and body parts when sold on the black market.

Uneducated About the Process

Still, many Americans are unwilling to become donors simply because they don't understand everything that goes along with the procedure. To help with this, health care providers are working adamantly with organizations such as Donate Life America to ensure that both the patient and patient's family have a clear understanding as to what occurs when organs are donated and transplanted. Some myths , that help explain the cons of organ donating, include:

- Donor would be unable to have an open-casket funeral

- Under 18 is too young to donate

- Patient is too old to donate

- Family members will be billed if an organ donation occurs

Prolongs the Family's Grieving Process

Another issue with organ donation is can potentially arise with the donor's family. It may be necessary to keep a loved one on life support for an extended period in order to keep the tissues healthy that are to be donated. Unfortunately, this may give the family a sense of false hope since they are still seeing 'life' and this may intensify the grief as well.

Family May Have a Problem With the Recipient

The family may have a problem with the fact that they do not have a choice on who receives their loved one's organs. It simply goes to the next organ recipient on the list that is a match. This means someone of a different culture, ethnicity, political belief or religion could receive their loved one's organs and this may be difficult for some families to accept.

Cons of Living Organ Donors

The most common organs supplied by living donors are kidneys and liver. While being a living organ donor can be very rewarding, unforeseen circumstances can arise and there is no way to know in advance if there will be problems. Some cons of being a living donor include:

Medical Cons

There are short-term and long-term medical cons for being a living donor.

Possible short-term cons may include:

- Blood clots

- Allergic reaction to anesthesia

- Bulging of stitches

- Feeling sick, vomiting, diarrhea

Possible long-term cons include:

- Pain (chronic)

- Adhesions from scars

If you're a living kidney donor, you may experience high blood pressure, diabetes, loss of kidney function (25-35%), chronic kidney disease and bowel blockage. A small percentage of donors end up needing a kidney transplant themselves but you will get priority since you're a living donor.

Emotional Cons

Emotional short-term cons include worry or anxiety about the surgery itself and stress during the recovery process.

Long-term emotional cons could include anger if the patient's body rejects the organ. You may feel sadness or regret as well.

Financial Cons

Short-term financial cons include the cost of travel and lodging. Also, lost wages for time off work due to testing, surgery, and recovery.

Long-term financial cons include having difficulty getting health or life insurance or having to pay a higher premium after the surgery. There is also a chance you would have trouble being accepted into the military or having a career in law enforcement or with the fire department.

Cons of Mandatory Organ Donation

There is a definite need for more organ donors and mandatory organ donation has been considered as an option. The cons of mandatory organ donation include:

- Organ donation, in general, may contradict personal, family or religious beliefs.

- People would lose their rights and freedom to decide what happens to their body after death.

- This change may not correlate with the deceased's wishes which could be very distressing for the family

- This change could allow certain doctors to spend less time saving lives in order to secure an organ that is needed by a patient.

An opt-out system or a program to recruit more donors may be a better option than making organ donation mandatory.

Benefits of Organ Donation

Many people have considered the pros and cons of being an organ donor. They understand the benefits of organ donation and believe it is not only a privilege but a social responsibility. Organs donated from one individual can save eight lives and enhance the quality of about 50 lives. Other benefits of organ donation are:

- It helps grieving families make some sense out of their loved one's death.

- It allows some individuals to improve or have a better quality of life.

- It is more cost-effective in the long run over the cost of lifelong medical care.

Weigh All Organ Donation Pros and Cons

When it really comes down to it, becoming an organ or tissue donor is really a personal decision that should be discussed with your next of kin, personal physician and spiritual leader. Before you sign up to be a donor, make sure you are completely educated about the process.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res

- v.27(2); Mar-Apr 2022

Concerns and Challenges of Living Donors When Making Decisions on Organ Donation: A Qualitative Study

Raziyeh sadat bahador.

Nursing Research Center, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

Jamileh Farokhzadian

Parvin mangolian, esmat nouhi, background:.

Mental concerns of living donors can be a solid barrier to logical and informed decision-making for organ donation. The present study explores living donors' mental concerns and problems during the process of decision-making for organ donation.

Materials and Methods:

present study was performed using qualitative content analysis. Twenty-one participants were selected by purposive sampling. The data were collected and recorded through semistructured interviews and analyzed by MAX Qualitative Data Analysis software 12, based on Graneheim and Lundman's contractual content analysis method.

Data analysis extracted 425 codes, 13 subcategories, 3 main categories, and 1 core theme (conflict between doubt and certainty). The three main categories were individual barriers and concerns (faced by the donor), interpersonal concerns and barriers (experienced by the family), and socio-organizational concerns and barriers (at the community).

Conclusions:

Based on the results, donors have significant concerns and face major problems when deciding on organ donation. Therefore, health-care professionals should take into account organ donors' concerns, raise awareness of donor associations, and formulate policies to increase living donors' satisfaction.

Introduction

Studies have shown that deceased donors cannot meet the growing demand for organs such as the kidneys, liver, etc. Sometimes cultural, religious, and legal considerations may even be reluctant to donate organs after death.[ 1 ] Thus, because of the high demand for organ transplantation and the increased wait time for transplantation, receiving organs from living donors is a primary strategy to meet patients' needs and overcome their problems.[ 2 ] Popoola et al .[ 3 ] reported that the low number of living donors had been identified as a significant challenge worldwide. Furthermore, donors go through a tough decision-making process for organ donation. They may encounter problems, worries, and concerns. Recent studies have shown that the decision to donate an organ is influenced by issues related to personal life, family status, and the relationship with the recipient, leading to a wide range of problems during the decision-making process.[ 4 ] The decision-making process has been significantly influenced by various concerns such as medical uncertainty, post-donation recovery, family responsibilities, recipient health-related concerns, and donors' health in the future.[ 5 ] According to Kim et al .,[ 6 ] barriers to the proliferation of live donors are multifactorial and need to be addressed using extensive nationwide studies. They stated that common concerns of living kidney donors include the impact of donation on future health, increased risk of chronic medical conditions with future weight gain or return to unhealthy lifestyles, and the inability to return to previous activities. Other studies have shown that obesity[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] and social factors may also prevent many potential donors from becoming donor candidates.[ 6 , 10 ]

Other studies have shown that despite unique liver transplant needs, many transplant programs and transplant-related activities have been suspended or severely restricted due to the rapid growth of the COVID-19 pandemic.[ 11 ] Another study showed that the prevalence of COVID-19 was one of the concerns that led to a significant reduction in the number of living and deceased liver transplant donors and the inactivation of the waiting list.[ 12 ]

In addition to the issues mentioned above, the acceptance of organ donation depends on cultural, ethnic, and religious factors in the community. For instance, Farid and Mou[ 1 ] stated that although organ donation and transplantation can be hopeful for dying patients, attitudes toward organ donation and transplantation can be different depending on religious, cultural, and legal issues in the community. Thus, community-related issues are some challenges beyond the individual decision to transplant an organ. Living donors' concerns always hinder making logical decisions. Thus, some strategies need to be adopted to educate donors and empower them to make informed decisions about donation. It is believed that as national policies require centers to inform potential donors of the specific risks associated with organ donation, comprehensive donor training is needed to address living donors' other concerns and possible misconceptions.[ 13 ]

Many studies have addressed barriers, challenges, and concerns of organ donation in brain-dead patients. However, problems faced by living donors have been less qualitatively examined. The present study used a qualitative approach and provided an in-depth analysis of barriers and problems faced by living donors. It tried to explore their mental concerns about the decision to donate organs to direct policies governing the community toward accurate assessment of possible risks and problems encountered by potential donors when making informed decisions and managing these mental concerns. It is not reasonable to encourage living people to give their organs to others for any reason, for example, in exchange for money. Thus, given the high demand for organ donation and the low number of donors, more investigations are needed to identify factors affecting donors' decisions for organ donation. To this end, the study explores the mental living donors' concerns and problems faced by them during the process of decision-making for organ donation.

Materials and Methods

This study was part of a larger research project that aimed to provide solutions to advance the decision-making on organ donation and was conducted from August 2019 to December 2020. A qualitative approach following contractual content analysis was adopted to explain the impact of organ donation on living donors. The participants were selected using purposive sampling from living organ donors, their family members, organ recipients, and medical staff in the Organ Donation Center, Kidney, and Bone Marrow Donation Commission in Afzalipour Hospital, and Kidney Donation Association in southeastern Iran. The interviews with the participants were conducted in places preferred by participants (hospital, private home, park, nursing school, etc.) so that they felt relaxed and unstressed during the interview since this study was conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak and given its possible risks for the participants, the research procedures were conducted with strict adherence to health and social protocols.

The data were collected through the interviews with 21 participants, including 16 organ donors, 1 member from the family of the donor, 1 organ recipient, 1 surgeon from the organ donation commission, 1 person who had given up to donate an organ, and 1 psychologist. Nine of the donors participating in the study were kidney donors, five were nonrelated (for sale), and four were related (not for sale). Four of them had bone-marrow donations, one nonrelated (for sale) and three related (not for sale), and the remaining three donors, who were related (not for sale), donated a portion of the liver.

Data analysis was performed simultaneously with data collection. Sampling continued without any restrictions until the data were saturated. Proper links were established between the identified categories. The first author conducted interviews. However, all the researchers reviewed the interviews like outside observers. After each interview, the researchers studied the interviews, identified the interview's strengths and weaknesses, and reviewed the items to be considered in the subsequent interview. According to the written reminders, the proposed questions required researchers to conduct additional interviews with two participants during the analysis of the data. Two interviews were conducted with participants 2 and 1. The researchers conducted a total of 22 interviews with 20 participants. The interview questions focused on the implications of organ donation in living donors. First, each interview started with warm-up questions followed by open-ended questions like “Would you mind sharing your experience of the organ donation you did?”, and probing questions for further clarification of the interviewee's statements. Each interview took 45–90 min. At the end of the interview, the participants were given the interviewer's mobile phone number and asked to discuss any issues with the interviewer if they remembered any of the implications of organ donation and the possibility of further interviews. Finally, the participants were appreciated with a small gift.

Data collection and analysis were performed simultaneously. The MAX Qualitative Data Analysis 12 was used to facilitate the organization and comparison of the data. The transcript of each interview was reviewed several times. The qualitative data content analysis process was performed according to the method proposed by Graneheim and Lundman, including transcribing the interview, reading the transcripts several times to come up with a general understanding of their content and get immersed in the data, determining semantic units, and summarizing them, extracting the primary codes, classifying the similar primary codes under the same subcategories, classifying similar codes under more comprehensive categories, extracting latent and manifest concepts from the data, and formulating the final themes.[ 14 ] To this end, after preparing the transcripts, each text was reviewed several times. Later, the semantic units were identified based on the research questions, and appropriate codes were assigned to each semantic unit. As shown in Table 1 , the preliminary codes were placed into subcategories and labeled based on their conceptual similarity. The subcategories were compared and placed under the more abstract categories (main categories). The main categories were further categorized under a more abstract concept (theme). All extracted codes and categories were reviewed and approved by the second and fifth authors of this study. The initially extracted codes were reduced by continuous data analysis and comparisons. Finally, the categories and subcategories were abstracted. The criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba (credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability) were used to ensure the trustworthiness of the data.[ 15 ] To ensure the credibility of the results, the participants were asked to review and confirm the codes extracted from the interview and revise the contents on demand (member check). Collecting the data from interviews with family caregivers with great diversity in terms of the relationship with the patient, ethnicity, and religion established credibility. To enhance the confirmability of the findings, all texts of the interviews, codes, and categories were reviewed and confirmed by the second, third, and fifth authors of this study (peer check) as well as a faculty member that was not a member of the research team (faculty check). To ensure the dependability of the results, all stages of the study were recorded. The participants were selected by maximum variation in terms of ethnicity, education, religion, economic status, relation to the patient, and social class, which enhanced the transferability of the findings of the study.

The participants’ demographic characteristics

Ethical considerations

To observe ethical considerations, the researcher asked the participants to complete the informed consent form. Moreover, before starting the interview, the participants' permission was obtained for recording the interviews and taking notes. They were also assured their demographic information would remain confidential. After the final report, the audio files would be removed, and, if desired, they could receive the audio file of the interview and be informed of the overall results. The participants were reassured that they were free to leave the study at any stage of the study. The Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences approved this study with the code of IR.KMU.REC.1398.222.

The participants were 21 persons including 16 organ donors, 1 donor family member, 1 organ recipient, a surgeon member of the donation commission, 1 person who has given up to donate an organ, and a psychologist. The participants were in the 26–58 age range. Table 1 displays participants' characteristics including gender, marital status, education level, age, etc., Following the analysis of the participants' statements about organ donation implications, 425 codes, 13 subcategories, 3 main categories, and 1 theme were extracted [ Table 2 ].

Themes, categories, and subcategories extracted from the data

The theme emerging from all categories was the conflict between doubt and certainty, which covered three main categories: “individual concerns and barriers (perceived by the donor),” “interpersonal concerns and barriers (experienced by the family),” and “socio-organizational barriers and concerns (apparent in the community).”

Individual concerns and barriers

This main category accounts for the mental concerns of the donor that disrupt the process of decision-making for organ donation and is the most critical category. It consists of five subcategories: “Fear of negative implications in the future,” “Fear of having Covid-19,” “Doubtfulness due to lack of knowledge,” “Lack of independence,” and “Fear of surgery and anesthesia.”

Fear of negative implications in the future

Sometimes, thinking about possible problems causes anxiety. Each decision may have positive and negative consequences that the donor must consider logically before making a decision. The donors expressed concerns such as fear of disability and the possibility of regret in the future, the possibility of rejection by others, fear of the unknown, etc., when making decisions on organ donation. Accordingly, one of the participants said: ”One of the fears that preoccupied my mind is what should I do in case of my kidney dysfunctions? What happens if I cannot find a kidney on time? If so, I may blame myself, but as soon as I leave everything to God, I will calm down” (P3).

Fear of getting COVID-19

Fear and anxiety about having COVID-19 raised some concerns for organ donors. Fear and anxiety weaken the immune system and raised shared concerns in donors in the current state of society. The participants pointed out to the possibility of developing COVID-19 during hospitalization, the impact of COVID-19 on the recovery process, and the possibility of deterioration due to having one kidney as the leading causes of concerns. One of the participants said: ”My only concern was the risk of getting Covid-19 during hospitalization. I was terrified of it; otherwise, I had made this decision, and I would rest assured If they made me ascertained” (P4).

Lack of knowledge and awareness

Having sufficient and up-to-date information leads to making rational and prudent decisions. A critical issue to consider in decision-making is collecting reliable information. Sharing information increases trust. The participants believed that the lack of knowledge and awareness could be due to the donor's unwillingness to obtain information, the time limit to get information, unavailability of a reliable source of information, obsession with acquiring more information, etc. One of the participants said: ”Although I inquired a lot, I was worried that I had not got enough information or my information was wrong, as if I was obsessed. I also feared that I did not have access to reliable information (physicians)” (P15).

Lack of independence

Some people constantly ask others for advice when faced with challenging life situations instead of making decisions based on their inner and personal needs. Fearing from the consequences of their choices, these people either constantly delay decisions or completely submit to the opinions of others. Making decisions to donate an organ depends on individual will and independence. The decision-maker must have an intention to decide and accept the responsibility. However, some participants pointed to some issues such as dependence on others in decision-making, fear of individual decision-making, and inability to take responsibility for decision-making. A participant said: ”I left it to my family to decide so that if something went wrong, they wouldn't blame me for making the wrong decision alone. Because I was afraid the transplant would be rejected, then my family would blame me for the uselessness of my transplanted organ” (P12).

Fear of surgery and anesthesia

Anesthesia, where general or local, is an integral part of the surgery. Anesthesia-related death news has left many people fearful of anesthesia during surgery. Fear and anxiety resulting from anesthesia are normal, but unfortunately, they may appear in the form of phobia. An influx of negative thoughts, not waking up after anesthesia, following similar bad news, and inability to overcome fear were some of the issues extracted from the participants' statements. One participant said: ”I am terrified of being anesthetized and not awakening then. I also feel horrible imagining myself in the waiting and operating room as I am intensively stressful” (P11).

Interpersonal concerns and barriers

This main category accounted for the concerns of family members for the donor. It had the subcategories such as “diversity of opinions,” “family opposition,” “history of chronic family diseases,” and “family beliefs and misconceptions.”

Variety of opinions